RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

The Black Avons I: How They Fared in the Time of the

Tudors

George Gill & Sons, London, 1925

"HISTORIES," said Hare, "used often to be stories. The fashion now is to leave out the story."

I have not, I hope, in recording the doings of the Black Avons, sacrificed history for the sake of romance. A right reading of history frequently offers us a solution to our present-day problems. It is a truism that history repeats itself, and it is a curious fact that we can find parallels for almost every political and national situation of to-day, if we delve into the story of the past.

I have endeavoured in the course of these narratives, which comprise the history of a fictitious family, to be honest, not only in my conclusions, but honest also to myself. We live too near to the great events of the immediate past to understand properly the true significance of that terrible conflict which drew into the field of war the civilized nations of the earth. Many of us are blinded by prejudice and suspicion, and may have forgotten that the spectre of military Germany was the successor to one as hideous and as terrifying, the spectre of an armed France, bent to the will of Napoleon Bonaparte.

The day must come, sooner or later—and history supplies inexorable proofs—when there will be a change in the orientation, not only of British policy but in the policies of the great nations of Europe. War and peace are no longer the playthings of despots. The widespread of education to which a great band of men and women have devoted their lives, has largely paralysed political machinery and has substituted the intelligent reasoning of the masses. As the fate of great parties is in the hands of the educated mass, so is the question of peace and war.

This little book is an unpretentious effort to present in story form some of the factors which determined the growth of British dominion. It is necessarily incomplete since it was impossible that I could bring into a short story all the factors that went to the making of our history. My only hope is that the stories may interest the student and lead him into the field of research—a field which holds many treasures for the diligent seeker.

E. W.

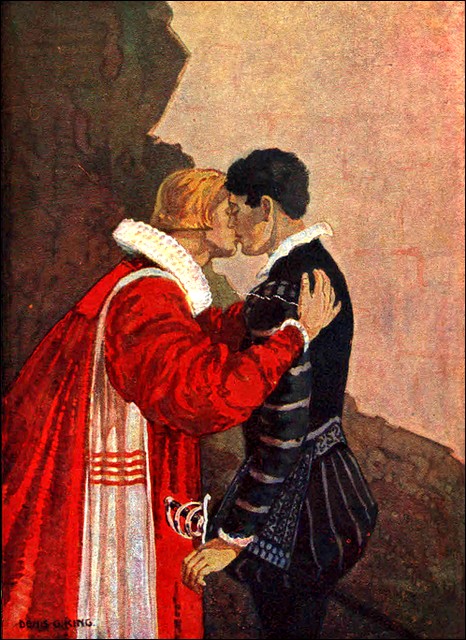

The Black Avons I. Frontispiece

I BEGIN by setting forth the meaning and reason of the writing—as all chroniclers of the Avon family must do—by virtue of an oath sworn in Winchester in the year of our Lord one thousand one hundred and thirty-nine, being some years after the first Henry's death (that so-called Lion of Justice). For five hundred years there hath appeared in every century an Avon whose locks were the colour of jet and whose skin was swarthy, and because such appearance hath marked troublous days in the history of England (as was well prophesied by Hugh de Boisy, a saintly man of Winchester), it was covenanted in these words, and so sworn before the altar in the presence of the Bishop, John de Blois, own brother to King Stephen, and a number of Christian gentlemen; to wit:

"He of the Avons who be most scholarly shall keep faithful chronicle of such events and curious or terrible happenings in the land of England which shall run with the life of a black Avon, we Avons here assembled in the great church at Winchester believing that, by the mysterious working of God, which, being ignorant and humble folk, we do not wot, it is ordained that the coming in of a black Avon is a portent or presage of Greater Glory for our land. Therefore shall be ever in our family one who shall be taught to write so that the black Avon when he doth appear shall be marked and his name immortalized to the Glory of God and the honour of the Avons who shall subsist hereafter."

Now when this oath was sworn there were but few clerkly men in the noble families, but nowadays, of the hundred and fifty-seven grown men and women of our race, there are as many as ten who can write fairly and near to eighty who can sign their names. Let us humbly thank God that He hath given enlightenment to His children.

I was born in the reign of the eighth Henry whom men called Bluff King Hal. The morn of my birth was the day when Anne Boleyn, who was mother of the great Elizabeth, was brought to the scaffold for her many wickednesses, and because of my father's admiration for the King (he approving of such terrible methods though he was a good husband and father), I was called Henry.

My father was a man of fortune, being Lord of the Manor of Beverleigh, near the town of Norwich, and he was a true Catholic who yet approved the six articles. I have heard it said by foolish young people that King Henry brought Protestantism and the ways of the German Luther into England. Such is the ignorance of these wights that they believe the king abolished the Roman Catholic religion. In truth Henry hated all Protestants, and I mind as a boy seeing three preachers of the reformed religion hanging upon one gibbet on the top of Norwich Castle.

For Henry did but deny to the Pope the headship of our Church and substitute himself therefor. And though he gave the Bible in the English tongue to every church, where it was chained to a pillar (as I have seen myself in many cathedrals and churches), yet as soon as he did find that the common people construed the Holy Scriptures to their own circumstances, then were the Bibles closed to them.

And many monasteries such as were rich, they say, he confiscated to the distress of the common people, who looked to the monks in their sickness and sorrow and had employment of them. Most of these monastery holdings was arable land which the peasants tilled, and when, as was the fashion in these times, the new holders of the land turned them to pasture for their sheep, there was misery and starvation in England, and honest labourers, having neither food nor work to procure the support of their families, joined with robbers and rebels, or else were branded or hanged as beggars.

The young boy Edward, sixth of that name to rule England, came to the throne in 1547 when I was eleven, and well I remember the bonfires we lit and tended, though there was sorrow enough for great Henry's death, and throughout the land (as my father has told me) an uneasiness of spirit, partly I think, because the people dreaded what might come about from the old King's will as to the succession, and partly because of the rising tide of discontent against the enclosuring of land which went on in our eastern counties to an extent beyond reason. The price of English wool was high, and the Flanders merchants could never get enough. So the great lords and the landowners began to take further pastures, enclosing common land which fed the peasant's flocks and on which he grew his food.

My father lived in style at Beverleigh Manor, the home of our family, and my heart grows wanting for the old place with the great avenues of oaks and its broad meadows.

Here came the gentry of the county, and I have seen two score when we sat at midday to dinner.

We kept a hearty table: mutton and young lamb, boars' heads and fat capons, with cunning pasties of venison and wild duck; large chines of beef and gallons of ale, cool and fragrant from the buttery.

Of those who came—and they were not the most welcome—I remember Robert Ket and William his brother. My father had some business with him, or he would not have come at all.

Particularly do I remember Robert, a noisy man of ruddy countenance, whom some of the gentry spoke of as "the tanner," though he lorded the Manor at Wymondham. He was a fresh-coloured, blusterous, talkative man, with great ideas about the wrongs of the people.

"This be the time when we would have a Black Avon among us," he said, in his broad, rustic way. "That from me, young master! For they do say hereabouts in Norfolk:

"'Red Avon a Lord,

Black Avon a Sword'

"and 'tis a sword we want and a right stout man to stand before these villains who enclose our lands that their sheep should browse and ours should starve! Ye'll see the day, young master, when the people of England will take sword and torch as they did in our forefathers' days."

"And be hanged, Master Ket," quoth I, "even as they."

He looked with gloom at this.

"You have the learning of a grown man, Master Henry Avon," he said. "But still I say: pray God sends us a Black Avon, for the Black Avons are on the people's side."

I liked him well enough, though his bull voice frightened me. Better I liked Anna Lyle (or de Lisle, as some say, she being of a French stock), his little ward, a quiet little maid with whom I oft-times played battledore and a kind of tennis. She was fair as I, though less learned in the matter of foreign tongues.

My memories of my home are vivid yet indistinct, as though I see it through a screen in which great rents are cut, so that some part of it is like as it were seen through a fog, and some most clear, even as to-day I may look out of my window and see the fields of Charing, where the church of St. Martin's-in-the-Field stands proudly amidst the cottages of the country folk.

My father was, as I say, well respected by the gentry, both for his learning, which was considerable, and his soldierly qualities, which were notable. He had served in war against France under His Grace the Duke of Suffolk, being squire at that time to Sir Edward Seymour, who afterwards was made Earl of Hertford, and about the time of which I write was styled Duke of Somerset. This association was to influence my life, for at the age of eleven, after the coming in of the young king, when the Duke of Somerset was appointed Protector, my father begged a place at Court for me, which was most graciously granted, I being promised Page of the Presence to His Grace.

"I doubt not you will find the Duke a kindly man, for this he has always been," said my father; "though as to his politics I have my own view. Yet it seems that he does not show the spirit and sureness which marked him in certain of his campaigns. King Henry went far enough with the Catholics, but Somerset goes farther. So that he will have a new religion here, to the hurt of the people, who see not the fine adjustings of such high matter, but know only one way to come to the presence of God, and, if that be denied them, will fight for it."

I told him thereupon all that Robert Ket had said to me, but this he dismissed angrily.

"Ket had better look to his fine manor at Wymondham," he said threateningly.

Two days before I set forth on my journey to London, my father told me, walking on the terrace of our house:

"Watch you well, my son, Dudley, Earl of Warwick, who is at Court no friend of the Duke's, if all the stories I hear be true. You will find him none too gentle of speech, but he is a good soldier. Speak to him and tell him you are of our stock, for we were together in the Scottish Wars, and he owes me a whole throat, for I cut down the Scottish gentleman who would have murdered him at Pinkie."

With my head buzzing with advice and admonitions, messages to old companions in arms, injunctions, warnings and the like, set I out from the city of Norwich one fair morning in May, my horse's head turned towards London, and two packhorses, my man Dick, and a gentleman of Norwich who was making the journey to London, being my companions. I wore my new suit, a doublet of fine red cloth, a greatcoat lined with fur, such as had come into fashion in Henry's day, leather riding boots to my calves, embroidered about the top in an ancient but very becoming fashion. I also wore my flat cap of velvet, which was then new-fangled, but later was worn by all the gentry.

My father at parting gave me seven shillings, the like of which sum I had never possessed in my life, and this I carried in a little bag attached to my belt. He was to allow me ten pounds a year for my keep and lodging, a large sum, and one rarely allowed to a younger son; so that, with the prospect of life at court and all the wonderful and stirring experiences which lay ahead of me, I set out with a light heart and came, at the end of nine days, to London.

The Court was at Greenwich, a palace which the young king greatly favoured. After a night spent amidst the bewilderment of a great city, I took barge next morning and was rowed past the great shipyards of Deptford to the beautiful palace where Edward was born.

I arrived too late to be seen by His Grace, but the next morning presented myself at his chambers and was kindly received by him, as my father had predicted. He was a man of over forty, and I can well believe the stories that I was told from the crowd of courtiers, pages and esquires with whom I mixed that morning, that he was sore distrait. All the time he spoke with me, which he did most courteously, his fingers were running through his locks, his eyes absent.

"Well indeed do I remember Sir John Avon," he said. And then, stroking his little beard, he seemed of a sudden to bring his mind to me and my visit. "There is no place for thee in my entourage," he said, and, seeing my face fall, he seemed at haste to rouse my drooping spirits. "But my lord Warwick spoke to me yesternight that he needed a clerkly page."

He then cross-examined me about my learning, and, sending for one of his gentlemen, bade him take me to the Earl of Warwick. As I was leaving his presence, he said:

"I'd like you best black, Master Avon! For I have need in these days of resolute swordsmen and balanced minds."

I knew he was talking about that famous Harry Avon of long ago, about whom my ancestor, Sir Thomas Avon of Chichester, had written.

I was puzzled that he should have sent me to the Earl of Warwick, for it was common gossip that between these gentlemen, who were the most important of the sixteen noblemen which formed the Council of the Regency, no great love was lost; though they had fought together in Scotland in the opening months of His Majesty's reign: the Scottish Wars, as you know, being caused by the refusal of the great Scottish lords to have our Edward made husband to Mary, the young Queen of Scots, who was now fled into France and married to the Dauphin.

Can it be (I have wondered) that the Lord Protector, as the Duke of Somerset was called, should desire that a member of my family, known to be loyal to His Grace, should be a spy upon his rival? Some such thought had the Earl of Warwick when I presented myself to him at his lodgings.

He was a dour, suspicious man, unfriendly of countenance, and had a way of half-closing his eyes when he looked at you as though he doubted every word you spoke.

"It is true, boy, that I need a page," he said, and then examined me as to my learning, and at the end gave me a letter which was written in the Greek and which I read for him in good English. It was signed "Jane," and little I knew, as I read that word, meaningless to me, that the tiny hand which had written so fairly was that which one day would push back her hair that the cruel headman's axe should have full play. For this Jane was the Lady Jane Grey, ward of the Earl of Warwick, daughter of the Marquis of Dorset, who later took the title of Duke of Suffolk; and when his lordship told me that this had been written by one who was a year younger than myself, I took doubt of my own learning.

"Why sent the Duke you to me?" he asked, when he had put away the letter. "Am I so poor in friends that my servants must be commended to me by His Grace?"

And then I think he remembered, for, with an impatient "Tut"—

"True, I spoke to the Duke. What is your name, young master?"

And when I told him, his crooked eyebrows rose.

"Thou art no black Avon, I see," he said with a laugh. "Therefore I must fear more your pen than your sword!"

With this he handed me to his secretary, directing him to find lodging for me; and I was sent forth to a tailor, that I might be fitted with the Warwick livery proper to my station.

In the months that followed I swear that he tested me well; for from time to time various fellows came to me pretending that they were favourable towards the Duke of Somerset, and saying that it would be well if His Grace were informed of what happened in the Earl of Warwick's cabinet, where they knew I was in constant attendance, for the secretary made use of me for the writing and reading of letters, and the making of fair copies of his correspondence with certain noble gentlemen of the kingdom. But to all these tempters and spies I returned a scornful answer, and presently his lordship came to regard me with friendliness, and on many occasions I carried letters for him to the highest in the land.

IT was not until after I had been six months in his service (my position being well pleasing to my father, who sent me a present of ten yards of velvet and a crown piece when he heard of my appointment) that I had the pleasure to see the King's Majesty. The Court was at Greenwich, and I went in attendance on my lord. It was a warm autumn day, I well remember, and the cool breezes of the river were very delectable after the heat and smother of town.

We went by barge from Westminster, passing Baynard's Castle and the great Tower of London, which stood up grimly by the water's edge, and after a long row I came for the second time to the village of Greenwich and the great palace that stands at the foot of a steep green hill, well covered with trees. We arrived in time to hear Archbishop Cranmer preach his daily sermon. The King, who loved this sermonizing, though he was but a boy, had had an open-air pulpit made, and here in the air we sat and listened, and I'll swear that none enjoyed this Cranmer so much as the King, who seemed to drink in every word, a look of eagerness on his peaked and sickly face. The sermon lasted for two hours and a quarter, until such of us as were standing were ready to drop.

Cranmer had a great influence over the King, and was at that time at the height of his power. The new English prayer-book had been printed, and also the forty-two Articles of Faith, which were afterwards reduced to thirty-nine.

It was strange to believe that this boy, who was ten—two years younger than myself—could bring himself to such an understanding of the holy mysteries which formed the subject of the Archbishop's discourse. The Archbishop spoke to me after the ceremony. He was a saintly man with a long beard, a gaunt expression and eyes of singular lustre. Throughout the sermon the Lord Protector Somerset had stood on one side of the King's chair, and my master on the other, and it seemed to me that they vied with one another as to who should offer the most acceptable interpretation of the preacher's words.

A few days after, my master sent for me, and I found him pacing up and down his great room, a heavy frown on his face, his hands clasped behind his back. He looked at me with his usual suspicion, and then took up a letter from the table.

"Place this in the pocket of your doublet, Henry Avon," he said, "and go you straight away to Chelsea, to the house of the Lord Admiral. To him this letter must be taken, and to him only. You understand?"

I had heard a great deal of the Lady Elizabeth, who was the King's sister, and by some accounted the most learned woman in the kingdom, though she was then at the most tender age of fourteen. I have heard my lord Warwick say that she was second only in brilliancy to Lady Jane Grey, but that she was more flighty and less godly.

He sent me a man-at-arms to attend me, because on the previous day a band of robbers had attacked a traveller on the lonely road across Blackheath, and I must ride on my errand as I had to call at the Tower to leave dispatches with the Lieutenant, for I had missed the tide.

I reached the City in safety and made my way through Temple Bar towards Chelsea. Near to the limits of the City, in that part of London which is called the Strand, I saw the builders, a very multitude of men, working at the great palace which is to be called Somerset House, and on which they tell me the Lord Protector had already spent one hundred thousand pounds. There was great murmuring about the Duke's ambition and his self-conceit, which took the shape of this grand building, which was to be greater than any royal palace. Some say that the money had come from the monasteries which he had suppressed, and there was a bitter feeling against him, especially in the western parts of England.

I came to the house of Lord Seymour of Sudeley, who was the Protector's younger brother and his most ambitious enemy; and because of the importance of my dispatch I was taken immediately by his page into the great library. I do not think that my lord expected that I should be shown in to him, but rather that I should wait in an antechamber, for when the door opened he was standing near a window looking upon the garden, and by his side was a slim, girlish figure, and his arm was about her shoulder, and there was so much tenderness in his gaze that I had thought that this might be his daughter, for his wife, who was Katharine Parr, and the last of the great Henry's wives, was newly dead.

He turned with a sharp exclamation; his hand fell to his side.

"How now, sir!" he said angrily, speaking to his page. "Did I not tell you—"

And then he checked himself with a laugh, and addressed me most kindly.

As he read the letter which I handed to him with a bow, I had time to examine this turbulent man, who was Lord High Admiral of England and was, by common repute, in league with the very pirates of the western coast it was his business to destroy. He was a man of singularly beautiful countenance, and well I can understand the fascination which he exercised. The lady I looked at more timidly. She was, I think, slightly older than I, but she was still a child, gracious of figure and very beautiful, with her fair, transparent skin, and her red hair, which had no covering. She was taller than I, and if she had any imperfection it was that she stooped a little. Who she was I did not guess, until my lord handed the letter to her.

"What say you to this, Elizabeth?" he asked.

The Princess Elizabeth, the King's sister! Looking back over all these years, I try to remember my emotions when I gazed for the first time upon that princess who was destined to be the greatest Queen that the world has ever known.

She read the letter quickly, and her red lips curled for a second in a smile, as she handed it back to the Admiral. I know not to this day what that dispatch contained, but I think it may have been that some rumour had reached my lord Warwick, and that he had written to warn the Admiral against his plans; for in those days the Protector's younger brother was renewing his suit with the Princess Elizabeth. You will remember that, when the great Henry died, by his will he left the Crown to his son by Jane Seymour, Edward, next to Mary his daughter, whose mother was Catharine of Aragon, and in the third line of succession, failing issue, to Elizabeth, the daughter of Anne Boleyn. Now the King was sick, and none believed that he would reach manhood's estate; while as to Mary, she was approaching middle age and had no husband.

I have another reason for believing that this letter had to do with Seymour's ambitious plot, for, as the Princess handed him back the letter, she said:

"His Grace will have your head for it, Thomas, it seems!"

Whereupon he laughed.

"There are things that I would less care to lose," he said significantly, and this brought a smile to the red lips.

"My lord," said Elizabeth drily, "if you did lose your head so often as you lose your heart, you would be a sorry servant of the King's Majesty!"

It was some three weeks after that I saw the sister of her highness. Sir Thomas Gresham, a great merchant of London and a Lord Mayor, had presented to the King a pair of the first silk stockings that were ever seen in these realms, and the King desired that these should be taken to the Princess Mary, with whom he had been at variance, because she so strongly opposed the new Reformation; and the Lord Warwick, who missed no opportunity of bringing himself favourably to the notice of the Princess, so contrived that the present should be taken by him.

I was one of the company that went with him into Essex, where the Princess Mary was for the time being in residence. There are many who speak ill of the Princess who became Queen, and speak of her in tones of horror and abhorrence. But to me, who saw her now for the first time, and who knew her as Queen, she was a sad and pitiable figure. Her youth had been blasted by the calumnies of her father. Save the Howards, she had few personal friends. She was insulted, almost starved for money, and could only reach King Henry's good graces by defaming her own mother. She had been persecuted for the convictions which she honestly held; she had seen the teachers of her religion ill-treated or murdered. Small wonder that, at the age of thirty, this woman, with her heavy face and her cold, repressive manner, should have been soured of the world which had treated her so ill.

My lord Warwick she did not trust: that was clear to me from the beginning. She saw through my master's flattery, his suave pleasantries, and was silent and attentive whilst he told her of the King's health.

"I trust that God will preserve for many years the life of my good brother, his highness," she said coldly, when he had finished. "Now tell me, my lord, what is the news of England? For here I am, without any guidance of public affairs; and except that I know the monasteries are being despoiled, and that my lord Somerset hath imposed a new prayer-book upon the people which they will not have, I know little."

She knew enough, it seemed, for she told him afterwards many horrid stories, of how certain evil men had destroyed the images in the churches and had paraded their villages in the sacred vestments.

"It seems that we are drifting towards Protestantism of a villainous kind," she said. "And were my lord Somerset an archangel, he could not take God from the ignorant peasantry and substitute another."

Returning to London, I rode by my lord Warwick's side, and he told me that he had never known the Princess so bold of speech, and this fact seemed to trouble him. For he guessed that the Princess Mary was better informed as to the King's health than he had wist.

"These be troublesome days, Henry," he said, as we rode through the rank and foul marshland which is called Moorfields, and came into the City by Old Gate, or, as the common people say, 'Aldgate.'

"There is no stability in the land, and it seems that my lord Protector has ears only for the flatterers who tell him one thing whilst all England is telling him another."

Trouble indeed there was! In the west the opposition to the new prayer-book roused the countryside, and the Protector had need to call in German mercenaries before the western rising was suppressed. At the same time there arose, to my alarm and fear, a rebellion in Norfolk, and long before confirmation of this news came, I knew that Robert Ket was behind it all. And so it proved; for Robert and his brother William had led a party from Wymondham, which had gathered size like a snowball, until he had fifteen thousand men encamped on Mousehold Heath, and levied tribute on the countryside. Many were the encounters and skirmishes which occurred between the gentry and the Kets, in one of which, to my incalculable sorrow, my dear father was slain by a yeoman named John Ward, who was afterwards hanged for it.

As the dispatches came through, my lord Warwick grew more and more impatient and fretful, for the Protector had gone north with an army to suppress the rebellion and had done no more than parley with Robert Ket, offering him a free pardon and the redress of his grievances (which were the enclosuring of the land) to which Robert replied that, since he had done no harm, he required no pardon. For he was the kind of man, as the saying is, who knew not where was enough.

There were meetings of the Council almost every day, and one morning I was awakened by the Groom of Chambers and told to prepare myself to accompany my lord Warwick into Norfolk. A large army of gentlemen and soldiers were assembled, and with these we marched with great rapidity into Norfolk, to find Robert Ket in possession of the fair city of Norwich and unwilling to parley. Though I doubt me that Warwick would have kept his promise, yet he did send a kind enough message to the rebels, repeating the Protector's promise of pardon, and when this was rejected my lord ordered the storming of the city, in which affair I had my first experience of warfare; though, if the truth be told, I was in no danger since I rode by my lord's side throughout the day, and entered the city with him when the walls were taken, and Robert Ket and his brother were prisoners, Robert being hanged on the castle and his brother William on the church door of Wymondham.

I had no more time than to ride across to my father's house, to find that he had already been buried in the family vault, and that my elder brother, Geoffrey, ruled in his place. I remember that morning especially because, apart from the sad nature of my pilgrimage to my father's grave, my brother Geoffrey, a sturdy, quiet fellow, with no stomach for soldiering, though he had served in the Scottish Wars, told me that he had received news from our uncle, Sir William Marston, who has an estate in Hampshire, that he had a son born to him who was "black of locks from his birth, with a skin darker than any I have seen...a lusty child, in all ways parfait."

In this queer, troubled setting did I learn of the coming of the Black Avon of my time; and though my heart was rent with sorrow, and my head buzzing with all the wonders of my late experience, yet I felt a strange thrill in me, such as some great astronomer might feel when he discovers in the firmament a new and a brilliant star.

The Old Gate

WHEN we came back to London there was news enough. Lord Sudeley, the High Admiral, had been arrested by his brother and committed to the Tower. Parliament was preparing a Bill of Attainder, that strange, terrible invention of the eighth Henry, whereby a man, without trial, may be condemned to death by a Parliamentary Bill. The Bill was passed and his head fell soon afterwards, the charge against him being treason, in that he had planned to marry the Princess Elizabeth and had plotted to overthrow his brother, the Protector; making cannon for himself, which was against the law, since all ordnance was by law the King's, and even coining his own money for his treacherous purpose.

When my lord Warwick heard this news, he became very grave, for he himself had corresponded with the Admiral, and in these days men's lives hung upon a thread, and one of any two who had influence with the King walked everlastingly in the shadow of the scaffold.

Yet Warwick had no cause for fear, for his star was in the ascendant, and every day it seemed that the influence of the Lord Protector was waning.

The Princess Elizabeth was removed to Hatfield and placed in the guardianship of Sir Robert Tyrwhitt, who strove most desperately to have her confess that she was party to the Admiral's plot. By confronting her with the statements of her servants, some of which were not creditable to her as a woman, though they had no bearing upon her ambition as a Princess, he sought to destroy that self-control, that brilliance of sense which was her surprising quality; but all this without success.

It was about this time that I made the acquaintance of the third great woman it was my especial privilege to meet in those stirring times. There came once to stay with my lord at his country house, when I was in attendance, the Duke of Suffolk, his wife and his daughter, who was the ward of my lord of Warwick. It was I who held the stirrup of this young lady when she dismounted from her palfrey at the door of the great hall, and these two hands supported for the space of a second that martyred form which to think of, even at this distant time, is to bring me near to tears. There was no more dainty lady, no sweeter face, no more lovely mind, than my lady Jane Grey, so gracious she was to all creatures, high and low, so well learned that Master Roger Ascham was abashed by her knowledge (and he the greatest tutor of the age). Her father I do regard as being the most contemptible figure in all history, though I speak with a bitter prejudice, as I well realize. Nor do I think more of her mother, who bullied her from cockcrow to dusk, with her "Come, Jane," and "Go, Jane," till the poor girl's life was scarce worth living.

They were ambitious, these people, beyond understanding. The lure of the Crown of England was always before their eyes, and to them their daughter was but an instrument for the gratification of their inordinate desires.

During the years that followed I saw the growth of my lord Warwick's idea, which was first to take Somerset's place as Protector of the realm, and then, at Edward's death, to set aside Henry's will and put Jane Grey upon the throne; though the claim was of the slightest.

The Duke of Suffolk had married Mary, the widow of Louis XII., and daughter of Henry VII. These latter had a daughter, Frances, who married Henry Grey, Duke of Suffolk, whose daughter was Lady Jane. Jane's grandmother was therefore the sister of Henry VIII., and on this shaky foundation was the great plot erected.

To get rid of Somerset was easy; and I, who was a witness of the turns and twists, and an eavesdropper of whisperings, saw the end come long before the great Protector was arrested and sent to the Tower. My lord Warwick had now the King's ear, and in a few days had got himself made Duke of Northumberland. The fall of Somerset was not acclaimed as my lord had expected, for the Protector had done much to check the enclosuring of land, and had brought into operation the Poor Law, whereby collections were to be made in each parish for the benefit of the needy. Against this was the issue of the second prayer-book in the year of his taking, and this went farther towards Protestantism than its predecessor; so that, whilst the labourers were appeased, the clergy and the nobility were still further enraged against the Protector.

The King liked him well enough, and was averse from bringing in a Bill of Attainder, and presently Somerset was released and again joined the Council. My lord feared him, and so did all who had consented to his arrest. We lived in those days of Somerset's return, walking, as my lord said, upon a razor's edge, and again was the young boy persuaded to send his uncle back to the Tower, this time never to emerge, for the Duke of Northumberland, my master, secured a warrant for his rival's death, and the head of the Protector fell, on a charge of conspiracy too paltry for me to set forth, because of the absurdity of it.

I was by this time on such good terms with the new Protector that often we discussed the most intimate matters of State, and he would pass to me the gossip that he had heard.

"The people take Somerset's death with little interest," he told me.

And, when I asked him what the King had said, he replied that the King had shown him his diary, in which he had written:

"This day the Duke of Somerset had his head cut off between eight and nine o'clock in the morning."

"And as for Princess Elizabeth," he went on, "it is reported to me that when Her Highness was told this afternoon that Somerset had been brought to the block, she merely shrugged her shoulders and said: 'This day has died a man of much wit but little sense.'"

Of my own fortune at this time it is only necessary to say that I had been advanced from the post of page to that of personal secretary to certain members of the Council, and I had reason to be grateful thereafter that I had not been accepted by His Grace as a member of his own household.

The King's health was failing. He remained at Greenwich all the year, 1552-1553, and I saw little of him. This I did not regret, for he was to me very colourless, and was, moreover, obsessed by theologies. But my master—for I still called him such, since he had placed me where I was and I had worn his livery—was with His Majesty all the time; and I know that some of the members of the Council were very feared of this, not knowing where Northumberland's ambition would lead him, for he was a man greatly mistrusted and even hated, and when the news came that the King was dying, and that Northumberland had been closeted with him hour after hour, and that a certain document had been signed by the King's Majesty, there was a feeling of excitement which seemed to communicate itself to the very people in the streets, so that the citizens of London gathered about my lord's house, as though they realized that from here would come the great news. For Edward was popular by reason of his piety and youth and because he had, under the Protector, set up schools where the poor might be taught.

Duty called me to Greenwich on the day of that fatal week when much would happen of such great importance to England. I learned at Greenwich for the first time that the paper which was signed by the King, and by all the great men and the judges, was to this effect: that Mary and Elizabeth were not born in true wedlock and that the throne was to be left to his cousin, Lady Jane Grey.

It was a broiling hot summer's day, as I sat in the antechamber of the Duke's apartments, overlooking the broad river, and envying the little boys I saw bathing from the green banks, when the door opened suddenly and the Duke came in.

He was very pale; his hands were trembling.

"Send me the sergeant-porter," he said. "And look you, Henry Avon, go in a manner so that no one will guess that anything is toward."

He called me back when I reached the door and said in a low voice:

"The King is dead, but none must know this. I will have the head of any man who bruits this abroad."

All the exits of the palace were guarded, and gathering a body of soldiers, the Duke set forth post haste to seize the person of Mary and confine her to the Tower.

Who carried the news that the King was dead, I know not. It was well enough understood that His Majesty was in extremis. And perhaps the gentlemen who had Princess Mary in charge were well enough informed as to the Duke's intentions. It is certain that when he arrived at the place where Mary should have been found, the cage was empty and the bird had flown to the Duke of Norfolk.

Northumberland came back in a great sweat and we repaired straight away to London, there to discover that the Lady Jane Grey had been brought thither, and well do I remember that interview. I shall never forget that white-faced girl, standing in the great council-room at Whitehall, as Northumberland strode in.

"My lord," she said, and her voice was very calm and resolute, "why have you brought me here?"

"To make thee Queen, Jane," he said, and straightway knelt and kissed her hand.

But she snatched it away.

"Queen I will never be," she said breathlessly. "Oh God! my lord, what madness is this?"

"Queen you are," said His Grace grimly.

And Queen she was proclaimed that night to the silent Londoners, who raised not so much as a cheer. One small apprentice boy indeed cried: "Long live Queen Mary!" for which his ears were nailed to the pillory and afterwards cut off, as I saw myself.

Thus came Lady Jane Grey to the throne of England, with sorrow in her heart and a fore-knowledge of her doom. Though she could not have been ignorant of Northumberland's purpose, for a few months before he had in great haste married her to his son, Lord Guildford Dudley, a boy of no other merit than that he loved Jane.

Mad indeed was Northumberland—mad and drunk with the lust for power; for he had none behind him, the Council being rebellious, the very judges who witnessed Edward's will already protesting that they did so under duress.

His first task was to secure the person of Mary, and to this end he gathered an army and marched against the Duke of Norfolk, getting no further than Newmarket before he found his men deserting. I saw him in Whitehall before he departed, and never again did I see his face. He had hardly left London when the Council met, repudiated the will by agreement, and proclaimed Queen Mary, and I heard no more until there came the Duke's steward to me, saying that his master had been put into the Tower and was in mortal peril of death for treason.

I did not love Northumberland, yet he had some qualities which were very pleasing, and to this day I am pained to think that he recanted his religious beliefs and grovelled to Mary for his life, though without any result. The headman was already sharpening his axe.

It was well for me that my fortune was not bound up with that of Northumberland, and that the gentlemen to whom I was secretary liked me well enough to forget that I ever held the Duke's confidence. I went forth with the Council to meet the new Queen when she came to London. She was then thirty-six, but looked older. I slipped away from the magnificent party which had gone out to meet her, and, standing near Aldgate, watched her coming in. First came the citizens' children, walking before her, magnificently dressed. Afterwards followed gentlemen habited in velvets of all sorts, some in black, some in white, some in yellow, violet and carnation. Others wore satins or taffetas, others damasks of all colours, having plenty of gold buttons. Afterwards followed the Mayor with the City Companies and the chiefs or masters of the several trades. After them the lords, brilliantly habited in the most splendid clothing. Next came the ladies, married and single, in the midst of whom was the Queen herself, mounted on a small, white, ambling nag, the furnishings of which were fringed with gold thread. About her were six lackeys, wearing dresses of gold. The Queen herself was dressed in violet velvet, whilst behind her rode the Princess Elizabeth with her retinue.

IT is strange indeed that such matters as treason and the punishment thereof, the comings and goings of Queens, of wondrous changes in the State Government, should have so little effect upon an humble secretary as I. For all went as before, save that the work was heavier.

Lady Jane Grey had already been conveyed to the Tower, but the new Queen had scarcely seated herself upon the throne than she ordered that the lot of the Lady Jane should be made as comfortable as possible. For she knew well enough what part Northumberland had played, with what reluctance this young girl had obeyed her father-in-law. Indeed, I found the Queen's Majesty very tender of heart, for all her sourness and the bitterness of her terrible experience; and even if she feared, as she had reason to fear, the discontented elements in her realm, yet she took not the most drastic steps against them unless such were absolutely necessary.

And so Lady Jane was removed to the King's house in the Tower, where she had her body-servants and her table, sitting at the head thereof. For her father, the Duke of Suffolk, imprisonment was not long. The Duchess, his wife, succeeded in obtaining his release. And I think that Lady Jane also might have come out if her selfish father had not joined Sir Thomas Wyatt in a rebellion against Mary, which was so successful that the rebels came up against London Bridge, across which they were not suffered to pass, but, making a wide detour through Kingston, reached London on the other side, where they were defeated.

The presence of Suffolk in this conspiracy sealed my poor lady's fate. An order was issued for execution, I carried it with my own hands to the Lieutenant at the Tower, and remained within that gloomy fortress for the night, more sleepless than she, more fearful than that great heart, who feared nothing but God.

That morning she had spent in prayer, and only once did she lose her self-control, and that before she was taken out by the Lieutenant; when somebody spoke of the Duke of Northumberland, her father-in-law, her face flushed and an angry little frown gathered on her smooth brow. (She was, you remember, a child of sixteen).

"Woe worth him!" she said bitterly. "His ambitions have brought my stock to this calamity!"

Dudley, her boy husband, was taken out first to Tower Hill, and from the windows of the King's house where we were assembled, she saw his mutilated body carried in on a rough bier.

She would not see her husband that morning, fearing the pain of parting. The block was set upon a little mound within the lower, at the spot where another queen (Anne Boleyn) had suffered, and she walked with unfaltering steps to the place of her death.

"I die in all innocency, a Christian woman."

I think those were her last words. I carried back to the Council the certification of her death, signed by the Lieutenant's own hand, and in my long ride I saw not London that day for tears.

What fate was hers seemed also to threaten Princess Elizabeth, who was committed to the Tower because of the Wyatt rebellion and the whisper that she had been privy to it. The Princess went by water, and the Traitor's Gates were opened to receive her: a circumstance which caused the Princess the greatest anger.

"I marvel what the nobles mean by suffering me, a princess, to be led into captivity the Lord knoweth wherefore: for myself I do not," she said, as the barge brought her down the river, and, when she landed: "Here lands as true a subject as ever landed at these stairs!"

Well indeed she might fear, though she did not show it, for on these stairs had landed her mother (half mad with fear), her suitor, the Lord High Admiral, and the Lady Jane Grey, now dead in the Tower.

The Traitor's Gate

THOSE years which followed the coming of Mary are to me as a bad dream. For myself, I was secure in Whitehall, having been appointed Clerk of certain Registers, which brought to me forty pounds a year, which with the twenty pounds I received from my brother, placed me in a very fair position of prosperity.

It was well known that when Mary came there would be a match with Philip of Spain, and that the Reformation would pass, perhaps never to return. For here was Elizabeth in the Tower, and God knew what morning would dawn with the news that her head had been smitten from her body, as certain bishops would have had it. They tried in all manner of ways to get her to confess she was in good harmony with Sir Thomas Wyatt.

The Queen, no sooner settled on her throne, sent to Rome and had over the Cardinal Pole, who was related to her, and from him received forgiveness for the heresy of England. Cranmer, Ridley and Latimer went to the Tower, and Bonner came out of that place. Master Cranmer recanted to save his life, though it was of no avail; and in the end shook off from him the burden of his weakness, became Protestant once more, and, bound to the stake at Oxford, stretched out the hand which had signed his recantation, that this offending member should first be burnt. Ridley and Latimer also died by this horrid means. And it is said (for I was not there to be sure that such a saying was made) that Latimer bade his brother bishop to be of good cheer, saying: "This day we will light a candle in England which, please God, shall never go out."

Yet it is a wicked folly to say of Mary that she burnt these martyrs out of her own hatred for the Reformation. She did no more than restore the heresy laws, as, indeed, she was bound to do by reason of her faith, and what came after was in logical sequence. She might restore monastery lands, as she did, but little she did for the peasant, nor could she restore the prosperity of the guilds which Somerset and Edward had despoiled, these guilds being the associations which helped the needy of their own craft.

Five bishops, twenty-one clergy, eight gentlemen, eighty-four artisans, a hundred labourers, fifty-five women and four children died at the stake during those years of Mary's reign. That the Princess Elizabeth would have gone to the block also, but for the intervention of the Queen's husband, Philip II. of Spain, is certain.

For all they say of her, the Queen's Majesty had a kindly heart. She spared Lady Jane for four months, until the Duke of Suffolk took up arms for his daughter; and had she confined her burnings to the bishops and left alone the common people, England would have thought little less of her. She charged all judges to deliver the law as between herself and the people, with no prejudice in her favour because she was Queen, or against them because they were poor. But for the burning of these common folk the people hated her. Even Catholics were amongst those who murmured at the cruelty of her commissioners, and there were whispers abroad, which came to my ears, that it would be better for England if Mary died and Elizabeth came to us as Queen.

The Princess Elizabeth I saw but once. She had been removed from the Tower and taken to Woodstock, and there I attended, in my capacity as clerk, to take certain accounts from her. She had grown into a beautiful girl, with a merry eye, and a sharp tongue that had no sting in it.

"I know you well, Master Avon," she said.

And when I had congratulated her, with such delicacy as I could muster, upon her change of lodgings, for she had recently come from the Tower, she answered:

"One prison is as like another as one wall is like another. I'd as lief be a milkmaid singing at my work as be Madame Elizabeth, Lady of Woodstock!"

She asked after the health of her sister, and for such news as I could give her of the Court. I told her there was great unhappiness in the land because of the burnings, and she grew grave at that. She said that she owed much to the offices of King Philip of Spain, and enquired of me whether it was true His Majesty had gone abroad (which he had, leaving the Queen for as much as eighteen months at a time). And I took the opportunity, though it were treason to do so, to speak of my kinsman, William Avon, who was then only eight.

"When, at the Queen Majesty's death, which God put off for many years, you become Queen of these realms, Madame Elizabeth, I would ask for a place for William."

And I told that he was a Black Avon, and the story of them, which she already knew.

She gave me messages to take to Mr. Cecil, who was her dear friend, and, as Lord Burleigh and Marquis of Salisbury, ruled her kingdom for her for many years. Also to Robert, Earl of Essex, who, she told me, had befriended her in her greatest need and had even pledged his estates to help her.

At this time we were at war with France, a war which the Queen's marriage with Philip II. had precipitated, and which ended with the loss of Calais. I saw little of King Philip, and I fear me that for him the marriage was no more than a piece of diplomacy, for he was more away from the Queen than with her.

Mary, who was never well, was troubled greatly by affairs of State. She was, moreover, a true daughter of her Church, and although, through Philip's influence, Protestantism had been stamped underground in England, there was in Scotland, across the border, a growing movement to carry the Reformation of Edward VI. to a farther extent than ever the Lord Protector had dared. Chief of these revolutionaries was one Master John Knox, whom I remember having seen at Court in the days of the late king: a hard-faced, bitter man, with a rasping, terrifying tongue. He had in his composition some of the granite of his native land.

The Queen of Scotland was also named Mary. She had married the Dauphin of France, her kingdom being administered by her mother (the third Mary), Mary of Guise. And at this growing revolt, Protestantism in England took heart of grace, and began to show above the ground. In the midst of her troubles Her Majesty was seized with a grievous illness, from which she did not recover; and an hour after her death I was riding with a company of gentlemen to Hatfield to announce to Madame Elizabeth that her sister was dead and that she reigned in her stead.

We rode not alone. The way to Hatfield was crowded with courtiers, who, as soon as they knew that Mary was dying, hastened to pay their shallow court to coming majesty.

A month after Queen Elizabeth came to the throne, it was my good fortune to be recommended, as I believe, by Her Majesty personally, to Sir William Cecil, so that I may say that in my short term of life—I was then twenty-two—I had been well recommended to two great statesmen. Mr. Secretary evidently knew my history, for when I came to his apartment to present myself he said, with a twinkle in his eye:

"God forfend, Mr. Avon, that your new master shall go the way of your old, for I like not the thought that your fortune was bound with His Grace of Somerset and His Grace of Northumberland."

I hastened to assure the Secretary that I had not served the Duke of Somerset, and that if I had had dealings with Northumberland, that was by the accident of my position as Secretary to certain gentlemen who served on the Council of the Regency.

"Right well I know that, Mr. Avon," he said, clapping me on the shoulder. "Now Her Majesty has told me of a certain blackamoor of your house, and has commanded me that he shall be brought to Court. Do you make the necessary arrangements."

That day, in great haste, I wrote to my uncle Sir Thomas, and told him of Mr. Secretary's words, and received from him by special post a letter saying that William was sick, it was feared, of the smallpox (though it was happily discovered after that it was but a fever of youth), and this I duly reported to Sir William, who asked me again to remind him, which I did just as soon as our troublous times were passed.

It was not until six years later, however, that the Black Avon came to Court. Not, it is true, to do any great deeds, for it was ordained that he was but to be a witness rather than a maker of history. Yet I thank God that a Black Avon has lived in my time, or else this advertisement of the Tudor reigns, slight as it is, would not have been written.

This, then, I tell you, that in these pages I do not seek the aggrandisement of my family at the expense of truth, and shall interpolate no romance so that it would appear that an Avon saved England, or that our family was well favoured by princes, so that I can only speak of one adventure of his, when he stood in the Cabinet of the Queen of Scots and saw my lord Ruthven work his murderous will upon her secretary. And so to my narrative.

Six years is little enough time in the history of a nation, yet in that six years the Queen had accomplished miracles, for she had reconciled Catholic with Protestant, and had re-established Protestantism in such a manner that the Catholics took little offence; and had so treated the Roman Catholics that Protestantism was not alarmed.

That she loved the Protestants I shall never believe; or that she unduly favoured Catholicism is equally unbelievable. She was a woman who feared God and had strong feeling about religion, yet she once said in my hearing:

"I mislike these men who plague our earthly state that they may achieve a heaven of their own designing."

Although of the reformed religion, she stood for many of the customs of the old Church. I remember once, when she was entertained by the wife of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Elizabeth, who hated the notion of married clergy, and opposed it at all times, had a sting in her speech for her at her farewell.

"And you, Madame, I may not call you; Mistress I am ashamed to call you; and so I know not what to call you. But howsoever, I thank you!"

She had a very great breadth of mind, and once, at a Council, I remember Sir Nicholas Throckmorton urging her to dismiss some Catholics from the Council because of their religion. Elizabeth turned in her seat at the head of the table in a fury.

"God's death, villain!" she exclaimed. "I will have thy head for that!"

Yet she did not hesitate, when men like the Bishop of Rochester and Bishop Bonner, having been deprived of their sees, petitioned her to join battle with them as to whether the Roman Church had first planted the Catholic faith within the realm.

"The records and chronicles of our realm testify the contrary," she said. "When Augustine came from Rome, this our realm had bishops and priests therein. It is well known to the wise and learned by woeful experience—they being martyrs for Christ, put to death because they denied Rome's usurped authority—how your Church entered therein by blood."

The Queen's one care in those days (as I well know) was to keep France out of Scotland, and mostly to stave off war and to keep at arm's length the French. Mary Queen of Scots was married to Francis II. of France who died shortly after he ascended to the throne, leaving Mary to return to Scotland and her uncouth realm. Her people trusted her not at all and hated her religion, interrupting and mocking her at her first mass.

Holyrood

BETWEEN Mary of Scots and Elizabeth there was no great friendship. Yet in our Queen's mind was a fear that Mary, by reason of her religion and her association with France, might lean towards a French alliance, to the danger of our realm. It was for this reason she proposed one of her favourites as a husband for Mary, who, rejecting the offer, chose Lord Darnley, son of the Earl of Lennox: a tall youth, with a dull, stupid face and a liking for pleasure. Strange stories came through from Scotland. They said the Queen hearkened more to her private secretary than to her councillors, and that the King was jealous of the influence of this David Rizzio, an Italian and very accomplished on the guitar as well as in the ways of crafty statesmanship.

The Queen's Majesty was perturbed by these stories, and often came to my lord Burleigh's cabinet, from which I was often dismissed whilst they talked together in private. This, I understand, was the mind of Elizabeth: that while she disliked Mary of Scots, both for her ways of living (for she was no angel), she deemed it not good policy that she should support the Queen's enemies, the common people of Edinburgh, and such of the lords as railed against her, and put up tickets* secretly and by night, defaming her.

[*Tickets = placards.]

We were in the beginning of this crisis when there came a new visitor to Court. I shall not readily forget that morning when the Black Avon appeared. It was in the month of February and London lay under a pall of snow, so that no gentleman went abroad except in a heavy coat lined with fur, and ladies who had to come from the country to be in attendance on the Queen found their coaches unable to move across the Hounslow Heath because of the great drifts which filled the holes in the road and brought about the ruin of their carriages.

I was in Lord Burleigh's cabinet when a page brought me news that a young gentleman desired to see me, and, as we expected that day a dispatch from my lord Bedford and Sir Thomas Randolph, who were at Berwick watching the events in Scotland, where it was rumoured that the Queen of Scots was at issue with her husband Darnley, I bade the boy bring the gentleman to me.

He returned, followed by one at the sight of whom my jaw dropped. A tall stripling, broad of shoulder, yet slim-waisted. Young, yet in the manner and countenance grave. His hair, cut short was as black as the raven's, his skin the olive tint of a Spaniard's. From head to foot he was dressed in black, and there was no jewel either hanging to his ear (such as gentlemen wore in these days) nor on his breast. Only the hard glitter of a sword-hilt showed at his side.

"I am William Avon," he said simply.

In another instant I took him in my arms.

"Welcome, Black Avon!" said I. "Behold in me thy faithful chronicler!"

It was at that moment that my lord came in and stood stock still at the sight of us. Flushing, I brought my kinsman to his notice.

"I give you welcome to Court, Mr. Avon," said the great Cecil, and took his hand. "Well do I remember as a boy reading of your illustrious forbears."

The Queen had many favourites, but none approached in point of affection Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, and it had been Lord Burleigh's policy never to attempt to supplant one favourite by another more to his own liking. I do not think that once he interfered with the Queen's private friendships, otherwise the coining of the Black Avon might have seemed an attempt on the part of my lord to oust Lord Leicester. For the Queen took an instant liking to my kinsman when he was presented at audience.

"By my faith you are black enough, Mr. Avon," she said, with a twinkle in her fine eyes. "As black indeed as some of the Jesuit priests that my lord Burleigh loves to hang at Tyburn! Now tell me, Mr. Avon, what colour is your mind?"

"Your Majesty," said my kinsman, "I am not long enough at Court to know the colour of your Majesty's livery."

I think the Queen liked that, for she was very quick to detect sincerity, and wise in the ways of flattering courtiers. The Black Avon had not been a week at Court before he proved that he had the qualities of his ancestors: for, one night, between Westminster and the City, he was attacked by three footpads out of Alsatia (the which is a haunt of outlaws and cut-throats near by the Black Friars) who rushed at him with drawn swords, and such was his cleverness of fence that he killed the three of them.

He had, I was pleased to see, all the qualities which had distinguished the men of his colouring: a courage of conviction, and a mind, as has been said of them, like "a balance of steel." One afternoon at Greenwich the Queen spoke bitterly against the Jesuit order, which was stirring up strife both in England and, with more success, in Ireland. William said nothing until the Queen challenged him.

"Madame your Majesty," he then said, "it seems a strange and terrible thing that He who came to bring peace to the world should have through the ages been served by princes of great uncharity. In the olden days of the Romans the Caesars burnt Christians for their sport, and many terrible stories have been told about the number that died for their faith. Yet His Grace the Duke of Alva, in the Netherlands, hath killed ten times more for Christ's sake than did Nero because of his beastly gods. The Christianity, be it Catholic or Protestant, which seeks to do hurt, is no longer a religion but a tyranny."

'Twas a bold thing to say before my lord Burleigh, who was hanging Jesuits whenever he could find them, but the Queen took no offence. How much he was in favour I did not know until one day in March he came to me and told me that he had been charged with a very secret mission and was leaving that night for Berwick. I think he was more frank with me than he would have been with any other man, because of our love for one another, for he told me that he was carrying secretly a letter to the Queen of Scots, warning her of certain devilish plots which were afoot against her peace and security. He was charged also by the Queen to convey a message to Mary, but of this he would not speak.

He left London that afternoon, and of his adventures in the realm of Scotland I must now tell, as he told me.

He travelled post, carrying with him an order, over the name of the lord Burleigh, that enabled him to secure relays of horses, and he arrived at Berwick without mishap. Here he lodged for the night with my lord Bedford and Sir Thomas Randolph, to whom he carried a letter, and in the morning set forth across the border and came without adventure to Edinburgh, where he lodged at a house in the Cowgate, in the house of Mr. Robert Melville, who, although a Scotsman, was in the pay of my lord Burleigh. This being necessary, for our Ambassador, Sir Thomas Randolph, had been ordered to leave the realm of Scotland because Mary regarded him as an enemy.

On the morning of March 8th the Black Avon rode alone through the foul streets of Edinburgh to Holyrood House, where the Queen was in residence.

"Her Majesty has not yet arisen," said the Steward of the Household, and, taking him into one of the grim and cold antechambers of the castle, left him.

William wondered why this course had been taken, and, suspecting treachery, loosened his sword. But presently the steward came back with a tall young man, whom my kinsman instantly recognized as the King, Henry Darnley. "King" I call him, though he was no king, for Mary had refused him the Crown Matrimonial and he was no more than the Queen's husband.

Darnley greeted him fairly and with every courtesy.

"Our steward tells us that you have come a long journey, Mr. Avon, and bear letters from Her Majesty the Queen our sister, to our dear wife."

Now William carried two letters, one for public display, and one to be conveyed privily to the Queen of Scots, telling her of the plot that was toward. And that letter which was public, he instantly drew from his doublet and handed with a bow to Darnley, who, without any pretence, opened it, though it was addressed to the Queen's Majesty. There was a look of trouble in his eyes as he broke the seal, but as he read his face grew relieved.

"This I will convey instantly to Her Majesty," he said, "but she has not yet arisen. For, as you know, good Mr. Avon, Scotland expects an heir and Her Majesty at this moment is not as well as we could wish."

Very civilly he asked William to come to dinner with his gentlemen, and this my cousin accepted, hoping that he should be able to see the Queen and deliver the private message he had for her.

He rode back to Mr. Melville, who was anxiously waiting to hear the result of his visit to Holyrood House, and when he had told that worthy gentleman how the King opened the letter, Master Melville was in some distress.

"There is a plot afoot," he said, "and it may involve the life of the Queen's Majesty. See you, Mr. Avon, that this letter is given to her before the night."

He then showed William a bond, which had been signed by Lord Darnley on the one part, and on the other part by the Earl of Argyll, the Earl of Murray, the Earl of Glencairn and others, whereby those gentlemen agreed to get for Darnley the Crown Matrimonial: that is to say, that he should be King as Mary was Queen, and that they should be enemies to his enemies.

"The blow may fall at any time now," said Mr. Melville. "Rizzio is doomed, and it would be no hard fate for him, for he is a foreigner and too much of a woman for our liking, with his carollings and lutings. But, likely as not, the Queen will die too, and Darnley and the lords will be set up over us."

William had little knowledge of Scottish politics, but he was one who had the power of grasping a situation and he spent the morning interviewing other Scottish gentlemen to whom he bore letters, and he found that there was in Scotland a party bitterly hostile to the Queen and to her religion, and that it was rare indeed to meet in that city a man who did not hate Mary and love John Knox, the preacher, who had openly denounced her.

That her life was free from suspicion, he could not believe. She was a woman with no great moral principles and of exceeding vanity.

He dined that day with my lord Darnley and certain nobles who had been mentioned in the bond, but there was no sign of the Queen or any of her gentlewomen, and he was leaving the castle in great perturbation of mind when a gentlewoman, passing him rapidly, murmured:

"Have you the letter for Her Majesty?"

For a moment he hesitated, thinking this might be a trap of Lord Darnley's, but that instinct which has always been the possession of his kind told him that she was a friend.

He quickened his step and kept pace with her. "No, madam," he said in a low voice, "it is in a safe place."

"Come hither at the sixth hour," she said hurriedly. "I will admit you by the small postern and take you to the Queen's presence."

And then she turned and walked quickly along a narrow passage that led from the main hall, and he did not see her again.

That her precaution was justified my kinsman discovered when he found himself being followed by two men obviously in Darnley's service. But happily at six o'clock it was dark and a thin mist lay over this wretched city; he was able to steal to the postern gate the Queen's woman had described, and was instantly admitted. He followed her up a winding staircase and, she opening a door, he found himself in a small room where supper was laid, and where most of the gentlemen and ladies of the Queen's private entourage had gathered. Here he met Mr. Arthur Erskine, the Earl of Bothwell, also Lord Robert Stewart, brother to the Earl of Murray who spoke to him fairly and made most kind enquiries about his journey from London.

Presently a little door opened and there came in a lady whom he instantly recognized, from the miniature which Queen Elizabeth wore attached to a gold chain about her waist, as the Queen of the Scots. Going forward, he knelt to her and kissed her little hand.

Behind her was Rizzio, the Italian, a man of slight build with a gentle face, and large, tender eyes, whom he saw at a glance, by the trim of his beard, was a foreigner.

The Queen received William graciously, and, taking the letter from his hand, made to open it, but, changing her mind, placed it in a pocket which was cunningly cut in the fold of her dress.

"It gives us great happiness to receive so fine a gentleman from the Queen's Majesty," she said, looking admiringly at William, as I guess, though this in his modesty he would never say.

And then she asked him what place he held at the Court, and when she learned how humble a one it was, asked him his religion.

"There will always be a place for you at my table, Master Avon," she said. And then, seeing that he still wore his sword, she smiled: "May one of my gentlemen relieve you of that weapon?" she asked. "For I like not well that gentlemen should wear dagg* or sword at meat."

[* dagg = small pistol.]

And much against his will, William agreed and allowed the sword to be carried to an outer room where the gentlemen had left their cloaks. And I think it was well for him that this happened; for though he was right quick with his sword, he might have had little chance with the bloody-minded men who were soon to appear in that little room.

The Queen seated him two places from her. She spoke little, seeming oppressed—indeed there was a great oppression on the meal. None spoke gaily, or, if they spoke at all, it was with forced humour. It seemed as though the very shadow of death lay upon them all.

And right truly their humour was tuned to the occasion, for they were but half way through when the door opened and, looking round, William saw Henry Darnley. He recognized my kinsman, and for a second started and turned pale. And then, as the Queen greeted him, he came without a word and sat at her side.

"My lord, you come late for supper." said Mary, uneasily it seemed.

Darnley made no answer, but his eyes for ever were glancing towards the way he had entered, and presently the reason of it appeared, for the door was pulled open with great violence and clamour, and there came into the room the lord Ruthven, with certain of his squires and men, and they were armed in warlike fashion.

"How now, my lord!" said Mary, rising in agitation. "What means this strange sight?"

For there had come in after Lord Ruthven yet more men who carried swords in their hands.

Ruthven did not answer her, but, fixing his eyes upon the pale secretary, beckoned.

"David, I need thee," he said harshly, and there could be no mistaking the menace in his voice.

Instantly William Avon was on his feet, smelling treason, but somebody at his side pulled him down and a woman's voice whispered in his ear:

"Have done, young sir. Can you fight swords with your hands?"

In the meantime Rizzio had risen and slipped behind the Queen. She fixed her angry eyes upon her husband, and he for his part could not meet them.

"What means this, my lord? Know you anything of this enterprise?"

He did not look at her, hanging his head.

"No," he muttered, "before God I know nothing of this."

The Queen glowered at Ruthven and pointed to the door.

"Go forth, my lord," she said, "under pain of treason. Void this room of your presence."

Ruthven for a second hesitated, and then, lurching towards the Queen, struck at the cringing secretary over her shoulder. She screamed and stepped back; somebody threw over a table, and one of the men at arms gripped the Italian and dragged him forth, whilst another, with a cocked pistol pointing at the Queen's heart, held her at bay, and thus they dragged the secretary through the narrow doorway, and William saw the rise and fall of their glittering daggers as they struck at the dying man before they flung him on the stone stairs to die.

The Queen stood against the wall, her face white, her dark eyes shining with a malignity beyond understanding, and presently Ruthven came back, hot and bloodstained.

"I tell you this, Mary," he said, "that if we have offended you, then, by God! you have offended us with your intolerable tyranny! For you have taken this David in council, and through him have maintained the ancient religion, putting upon the Council also my lord Bothwell, who is a traitor!"

By this time the lord he had named, also my lord Atholl and Sir James Balfour, who were in the cabinet at supper when Darnley had arrived, had made their escape. Though it would appear that it would have been the blessing of God if one at least of these had broken his neck as he slid by a cord down the castle wall.

All the time my kinsman, William Avon, had watched this scene powerless, had seen most horrid murder done, and had been insulted, and must needs stand quiet. (Afterwards, I asked whether his blood did not boil).

"For Rizzio, yes, for the Queen, no," quoth he, in his cold practical way. "For mark me, Henry, this Queen had death in her eyes when she spoke to Darnley, and well I know she was capable of taking care to herself."

The King and the Queen had angry speech. Words passed between them, accusations and counter-accusations, which it is not seemly to write about. But at the end, though Rizzio lay on the stairs, with fifty-six wounds gaping, she and her prince went away together, seemingly well reconciled.

Next morning William made preparations for his departure, and none said him nay, though Melville warned him that, once Darnley gave thought to the matter, he would not easily pass out of the realm. And so this proved, for three leagues south of Edinburgh town he was overtaken by two gentlemen, who spoke him civilly and told him that they were of the household of Lord Ruthven, who desired that he should return with them. It chanced that he recognized the speaker as one of those who had come into the Queen's cabinet and had struck at Rizzio.

"Monsieur," said this man in the French manner, his name being de Croc, the same as, but no relation to, the French Ambassador to Mary's Court, "Monsieur, because of stories that may run across the border, and all manner of hateful prejudices which may be excited, it is desirable that you should return to Edinburgh with us, so that you may have speech with the King. Which will be to your profit."

William Avon laughed, and I think when he laughed he was most dangerous.

"God save you, gentlemen, go your way," he said; "for I am in the service of the greatest prince in Christendom, her excellent Majesty, Queen Elizabeth, and I tell no tales except the truth. This I tell you, though I speak not willingly with murderers."

"Fellow," said the other hotly, "it was no murder we did but the execution of divine justice."

"So be it," said William Avon, as he half-turned his horse's head. "Then I will say that hangmen and headsmen are not to my taste."

As he spurred back his horse, they drew on him, but before their swords were pointed, his was out, and he was on foot. They thought they had him at a disadvantage. Three passes, and Ruthven's man toppled over with a groan; but his friend, having no heart for the business, turned and galloped away as fast as spurs could force him.

Taking the dead man's horse, my cousin rode on. He had intended to lie at a little village that night, and well for him that he changed his mind; for my lord Darnley sent a troop after him with orders to take him dead or alive, and as he crossed the English border the dust of the column showed against the sky not three miles behind him.

The Earl of Bedford had already received some news of the dreadful deed, and when William had told the full story, my lord sent him off to bed while he wrote his dispatches, and four hours later my kinsman was on his way to London.

The Queen was at Westminster when the "Black Avon" arrived, and he hastened to her with the dispatch. He told me afterwards that he found her alone with Lord Burleigh, and that before the dispatch was read she asked him to tell her briefly what had happened, for she knew by his quick return that something unusual had happened.

She spoke no word when he told of the murder, though my lord Burleigh was greatly troubled, and when he had finished she looked at the picture of Mary which she carried at her waist and nodded slowly.

"Had I been you, my good sister," quoth she, "I would have snatched Darnley's dagger and killed him where he stood!"

Of the dead Italian she said nothing, regarding him, I think, as a bad servant who had brought the Queen's name into disrepute. Indeed, her anger was for Darnley and not for the murderers, since, when some of them took refuge in England, and Mary sent her a letter asking that they be turned out, she did no more than order Sir John Foster, who was Lieutenant of the Marches, to have them sent away from the town in which they had taken refuge; and this she did in such a leisurely fashion that no harm came to them.

William came to lodge with me and told me more than was in the dispatch, such as what the Queen had said to Darnley, and Darnley to her.