RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

The Black Avons III: From Waterloo to the Mutiny

George Gill & Sons, London, 1925

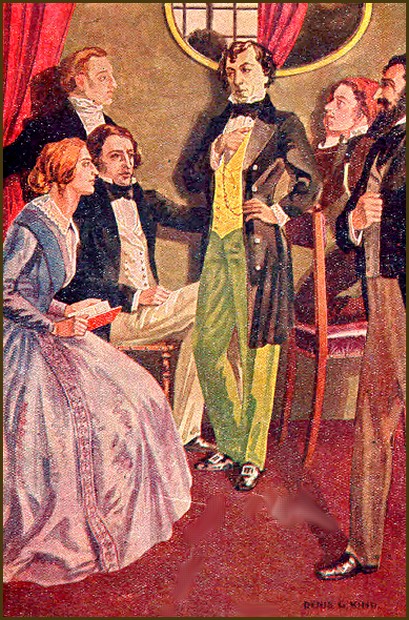

The Black Avons III — Fronstispiece

INTO what a troubled world was I born in the year of grace 1800! Ireland in revolt and defeated at Vinegar Hill, their French allies in the hands of Lord Cornwallis and an Act of Union forced upon her; the echoes of Napoleon's defeat in Palestine and the glorious thunders of Nelson's guns at Alexandria still reverberating; Italy crushed by Bonaparte at Marengo and overrun; Austria shattered by the same masterly hand, and Britain alone, but triumphant.

My father has often told me of the stirring events which had come before my birth, of the terrible revolution in France which had inflamed the world against the murderers of King Louis, and of how this Napoleon Bonaparte, a young officer of artillery, had first given the quietus to the dying revolt by "a whiff of grape shot" that finally destroyed the resistance to the central government. In a word, Bonaparte had shown the attributes of a great general and had produced from the wreckage and chaos of the revolution an authority which had the support of military strength and the approval of the majority of French people.

So that whilst all the nations of Europe had at first been stricken with horror at the excesses of the revolutionaries, and had drawn their swords to avenge the unhappy Louis and his beautiful consort, they were now compelled to sharpen those swords to defend themselves against the menace of order which, most surprisingly, came out of the confusion. Some there were that elected to fight, some to intrigue, some to fight first and parley afterwards, well content that their allies should be embarrassed thereby, and one alone that offered no arbitration but the dread adjustments of battle. And this country, to our honour and glory, was Great Britain (as it had been called since the days of Anne).

A troubled world indeed, and even as I lay newly born in my nurse's arms, the coach drew up before the Mitre Inn at Norwich and the guard threw out the broad-sheets which told of Nelson's glorious battle of Copenhagen, wherein assailed by the fire of a thousand guns and with only twelve ships of the line, three of which grounded before the battle, he silenced the Danish batteries and brought about the submission of the city. In this battle it is said that, ordered by his superior officer, Sir Hyde Parker, to retire, he put his telescope to his blind eye and said:

"I do not see the signal. Keep mine for 'closer battle' flying—nail it to the mast!"

Such was this time of stress and doubt.

About my own family affairs it may be proper here to speak. There were three families of Avons: my own, which was called the Old Avons, living in Norfolk at that very manor which has been described by my ancestor, Henry Avon, of Elizabeth's days; there were the Bedford Avons, the head of which was the grandson of that William who was the writer of the narrative of the Stuarts; and the third branch, which we call the Black branch, because it has produced so many swarthy members of our race; this had its home in Hampshire.

Between my father, Henry Anthony Avon, and the head of the Black House, who was Sir John Avon, Baronet, there was, in the year before I was born, a great coolness, which was to develop almost to a bitter quarrel. And it arose in this way: Sir John had served in Ireland and had seen the pitiable condition of the people, and had realized how horrid a thing was the law which had been made in the days of William and Mary, whereby no Irish Catholic was allowed either to sit in Parliament, to vote for a Member, to occupy any position under government, or even to own a horse worth more than £5. The situation of these unfortunate peasants was cruel in the extreme, and the tyranny exercised by the Protestants was such as no honest man could tolerate. So that the Irish people were virtually outlaws and beggars; and it was Sir John who, coming back from Ireland, had pleaded with Mr. Pitt, the chief minister of His Majesty King George III., that their lot should be ameliorated—not that Mr. Pitt needed any persuasion, for he had the genius of government and had long realized how terrible were the conditions under which the Catholics lived.

Then came the rising, and Sir John openly sided with the rebels, to the indignation of my father. Hot words passed between them at White's, the club of which they were both members. My father accused him of being a Papist, which Sir John took amiss, for he was as good a Protestant as ever went to communion. A tall, red-haired, red-faced man, with the strength of an ox and the courage of a lion, he feared neither popular opinion nor the vengeance of the fanatic. Mr. Pitt was so much of his opinion that after the inevitable defeat of these wretched Irish Catholics, and the Act of Union between Ireland and England which was secured by the liberal bribery of my lord Castlereagh, the Prime Minister brought before the King an Act of Catholic Emancipation which George, who had already lost America by his obstinacy and stupidity, refused to endorse. Good a king as he was in the days of his active mentality, he was without vision or foresight. The King would have none of the Catholic emancipation, and Mr. Pitt resigned his office to Addington, his friend.

It seems strange to me, looking back through all these years, that two good Protestants, as my father was and as undoubtedly was Sir John, should be at daggers drawn over the matter of the treatment of Catholics in Ireland. But so it was, and when I was born, there came no letter by post from Sir John, nor was there any letter from my father a week after, when Sir John's son, Harry, was born.

Addington made a peace with France in 1802, the treaty being signed at Amiens, and our country rejoiced after all these years of war. At last we were freed from the spectre of ruination which wars bring in their wake. Yet that was not the view of the wiser folk and amongst those who did not rejoice, as I learned after, was Sir John. Whilst bonfires were burning and lights were in all the windows, the manor house in Hampshire was dark.

"There will be little to please us," said Sir John grimly. "This man Bonaparte is not the kind who will grow great on treaties."

He was a close friend of Mr. William Pitt, who stayed with him in Hampshire during the time of his retirement, and he was my uncle's guest when the new cause of war arose. You must understand that in these days the newspapers had grown in number, and one of these was publishing certain violent articles against Bonaparte, at the instigation of the Royalists of France, who had fled during the Revolution and were at the time waiting in England until they could return.

Mr. Pitt told my father that Bonaparte was very angry with the newspaper articles, and also with the fact that England was harbouring Royalists; and within a year after the signing of the Treaty of Amiens, war was declared again by Napoleon who marched his armies to Boulogne, ready to invade our country, and to this end had innumerable flat-bottomed boats built to carry his soldiers to our shores. In consequence there was much building of towers (which were called, after the inventor, Martello) along the coasts, and I am told that even in Hampshire, people in the villages and towns were ready to leave at a minute's notice to fly from the French invader, and had wagons on the roads and horses already harnessed to move their goods.

At this moment Mr. Pitt was recalled to office, and began to stir up Europe to take sides against Bonaparte, who had proclaimed himself Emperor of the French. Russia and Austria joined, but in 1804 Bonaparte crushed the forces of both countries at Austerlitz, and Britain stood alone.

The shock of Austerlitz killed Pitt.

"In what straits do I leave my country!" were almost his last words.

And now the threat of invasion was very real. Napoleon, while he was marching on the Austrians, had ordered the allied French and Spanish fleets to move to the West Indies in order to deceive Admiral Nelson into following them. Napoleon's plan was for his fleet to double back and make for the English Channel to cover the crossing of the army of invasion. We were ready enough for this, for the threat of it had brought into existence the famous Volunteers. But Nelson saved us from the peril: he discovered in time that the French and Spanish fleets had turned, and came back after them. Admiral Calder with a small fleet intercepted the returning enemy, sank two ships and drove the rest into Cadiz Harbour; and here they might have remained, for Villeneuve, the French admiral, realized the peril of fighting Nelson's ships, which were now almost in sight. Napoleon, however, sent a furious message ordering his admiral to fight, and issuing from the harbour the French and Spanish ships came up with the English fleet in Trafalgar Bay. Ours were arranged in two lines, at the head of the first being Nelson's flagship the "Victory," and at the head of the other Lord Collingwood's "Royal Sovereign." When everything was ready for the attack Lord Nelson asked Captain Blackwood, his flag captain, if a signal should not be made to the whole fleet.

"My lord," said Captain Blackwood, "I think the Fleet knows well enough what it is about."

Nelson was not satisfied with this, and sent up the signal which, a month after, was in everybody's mouth: "England expects that every man will do his duty," a signal which was answered with ringing cheers.

At midday the battle began, and soon after the French "Redoubtable" was engaged with the "Victory." In the midst of the action Nelson was stricken down, being shot from the cross-trees of the "Redoubtable."

"They have done for me at last, Hardy," he said to his friend. And, that the news of his wound should not discourage his men, he took out his handkerchief and covered his face and the decorations he wore on his breast, and so was carried below. He lived long enough to know that the British were everywhere victorious, and his last words were: "Thank God I have done my duty!" Twenty of the French ships struck, and their admiral, Villeneuve, was taken prisoner.

Grenville's ministry had followed Mr. Pitt's, and in this was Mr. Fox, who did so much with Mr. Wilberforce to abolish slavery. He fell, for the same reason that Mr. Pitt had fallen, that he would not be a party to the intolerant attitude towards the Catholics. He was, my father told me, a great gambler and a fop, but was well liked by the majority of people. After him came Lord Portland and then Mr. Percival.

I remember dimly, as a child may remember, the death of Mr. Pitt and the grief my uncle, who was an admirer of this sublime statesman, felt at this tragedy which had come upon England. Possibly the friendship which Sir John had enjoyed with him had something to do with the gradual reconciliation which came about between the two branches of the family. I remember well, as a small boy, sitting open-mouthed whilst my father and my Uncle John discussed politics, referring very often to Berlin. I learned many years after, when I gave the matter serious thought (for a child does not think naturally of political or national affairs, but is more interested in his tops and his shuttlecocks) that the subject of discussion was the Berlin Decree. Napoleon had beaten the German Army and had quartered himself in Berlin, whence he sent out a decree, in which he declared that the British Isles were blockaded, and expressly forbade all countries in Europe that had been occupied or conquered by France to have any commercial dealings with our country. This was the famous continental system, which nearly ruined the French as well as the allies of France. In reply, England issued Orders in Council, forbidding British vessels to trade between ports in the possession of France, and all ports that were forbidden to our trade were declared to be in a state of blockade. We also forbade the French to sell their ships to neutral powers.

At this time, Denmark, which had been a neutral state, allowed the French to operate against the Prussians from their territory, and it was well bruited about that Napoleon had the idea of seizing the Danish Navy and using it against us. And so we sent a squadron of ships and an army of twenty thousand men to demand an alliance and the surrender of the fleet. When this was refused, we opened fire on the town and the fleet was surrendered.

My uncle's visits now became more frequent and, as he was distantly related, through my aunt, to Lord Liverpool, who had succeeded Mr. Percival, he heard much that was not generally known to the people. I was still a boy, and I remember that so continuous were the wars that I cherished the illusion for many years that war was a normal condition.

One good result of the reconciliation between my father and my Uncle John was the opportunity I had of meeting the boy who was born a very short time after me. He was taller than I, and slimmer, ours being a stocky breed. We liked each other from the very first, and this was fortunate, for we were packed off together to the Grammar School at King's Lynn, or, as some call it still, Lynn Regis. Here we had lodgings in the house where one of the ushers of the school had once lived, a very gentle man called Eugene Aram, about whose terrible crime and remorse I had often read, since it formed the subject of many ballads.

In this beautiful old town my cousin and I grew up together, went to our lessons, took our drubbings, stole time to fish in the "fleets," as they call the little streams, and between our play sought eagerly from the latest newsprints. Many a sevenpence have I spent upon a newspaper to find what was happening to Sir Arthur Wellesley in the Peninsula (where we were fighting Bonaparte, who had seized the Spanish throne); for Sir Arthur was the greatest general of our time. By these newsprints, which I still have by me, I can trace the wondrous doings of our gallant Army even to this day, and have no need for history books to guide me. I see Sir Arthur falling back to his prepared line at Torres Vedras before Junot, I see the gallant Sir John Moore retreating on Corunna, and the glorious victory of Vittoria, which opened the way for the British Army to cross the Pyrenees into France, and brought us triumphantly to the siege of Toulouse. My cousin and I were both fourteen years of age and advanced well in our studies, when the news of Napoleon's abdication reached King's Lynn. It came not by news-sheet, but by my Uncle John, who came post from London to my father and called at King's Lynn on his way, sending for us to his rooms in the old inn, and giving us a glass of wine to drink King George's health.

"They have packed Bonaparte off to Elba," he said, shaking his head gloomily, "but the Lord knows how long he'll stay there. Better for the Allies, I think, if they put him against the wall before a firing party!"

Those who live nowadays cannot realize the horror and abhorrence in which Bonaparte's name was held; and though, later, we came to forget his tyrannies and his wicked ambitions and thought only of his great prowess and abilities as a general, yet such sentiments were heard on every side. Sir Arthur Wellesley, who was now the Duke of Wellington, had gone off to Vienna to sit on the council which was to settle Europe.

"But he'll never do it," said my Uncle John, shaking his huge red head again. "Not our Duke or any other body's Duke, with all these greedy Italians and Dutchmen looking for what they can grab."

Still it seemed, from the newspapers, that the settlement was a good one, and was satisfactory to most, though the conference had not concluded when the white-flecked post-horses came galloping into King's Lynn with the news that Bonaparte had escaped from Elba and landed in France, and that the soldiers of the new French King, Louis, whom the Allies had put on the throne, were throwing away their white cockades and joining for the Emperor.

My father being now enfeebled in health, Uncle John spent much of his time in Norwich and came frequently to see us, and he took a view of the situation which was alarming.

"Bonaparte," said he, "has beaten every nation in Europe. He has beaten the Russians, though they learned a trick from Wellington and retreated before him to Moscow, causing him the loss of over three hundred thousand men. Yet this is the point, boys: he has beaten them once, and he may do it again. He had trounced the Germans and the Italians and the Spaniards, and though they cry out now against him, and will send their soldiers to oppose his march, in the end it will be old England that will be left to fight him alone, and we need every man—aye, and every boy—to crush this monster."

"But, Uncle," I made bold to say, "have we not the old soldiers who were in the Peninsular War under the great Wellesley?"

Uncle John shook his head, and told me something which amazed me.

"We are at war with America, as you know," he said. And of course I knew about the second American war, which had come about because the Americans resented our searching neutral shipping. I knew, too, that a victorious British Army had occupied Washington (a fact which very few people nowadays seem to remember).

"We have sent all our best soldiers to the American War," my uncle went on, "and now the Lieutenants of the Counties are hard put to it to find men to resist Napoleon; and within a month we shall be sending out raw plough-boys in red coats to meet the finest trained soldiers in the world!"

When my uncle had gone, Harry and I had a long and serious talk. Though we were but fifteen, we were as tall as most men, and I, for my part, could hold my own ground with any townsman.

"There is only one thing for us to do," said Harry, with great determination, "and that is to 'list."

"Enlist?" I said, aghast at the idea.

Harry nodded.

"What else can we do? If we ask our fathers to get us commissions, they will laugh at us because we're so young."

And that was true. Day and night we talked this matter in and out, and at last we had a plan. In Brussels was a cousin of ours, a Bedford Avon, who was on the staff of the British Ambassador; and as Sir John had told us before leaving that the great war would probably be fought out in the Low Countries, ours seemed as likely a scheme as any. Our plan was to run away from school, taking the day coach to Yarmouth, and there obtaining a passage to Ostend or to Flushing. From thence onward we could reach Brussels by coach, and, seeking out our kinsman, ask his help to secure us commissions.

All this discussion took some time. Before it was ended, the way the war would go was made apparent. Our soldiers were being sent across to Flanders by the thousand, and we had news that the brave Marshal Blucher, the German commander, was gathering an army on the Rhine, and that this would join with the Duke of Wellington's force, and that both armies would make a march upon Paris.

At last, in the month of May, 1815, our plans were completed; and, after writing letters to our fathers, we slipped out of the house, taking just as much hand baggage as was necessary, and picked up the Yarmouth coach early next morning, having waited on the Norwich road for some hours before it appeared. At Yarmouth we had no difficulty in obtaining a passage on a small sloop that was carrying, as we discovered, fish for the new army, these being dried and packed in bales; and though the smell of them did not comfort us when the little sloop began to roll in the heavy seas, yet we maintained our dignity till the sloop was brought alongside at Ostend, a small village on the coast of Flanders. Happily, the day we arrived, three great ships came into the roads, filled with soldiers, and we were not questioned when we went ashore, and set out straight away to find means for getting to Brussels.

We slept that night in Ostend, and the next morning, having hired a chaise, we set forth through Bruges and reached Ghent late that night. The following morning we were up at daybreak and, hiring relays of horses, came into Brussels after all the inns were closed, and had perforce to sleep in a stable where we baited our horses. We did, however, succeed in finding rooms in an hotel early the next morning, and for this we were grateful, for our stock of money was running low, the prices of hotels being extraordinary high.

In Sir Giles Avon, our illustrious kinsman, we found a very dear friend, and no sooner were we announced at the Embassy than he had us in to breakfast with him.

"Your fathers will never forgive me," he said, with a chuckle, after Harry had told him what we desired. "And as for getting commissions in the King's Army, why, that is impossible. But the Duke of Wellington is expected soon, and I will make it my business to see what can be done for you."

He gave us money to comfort ourselves, and after warning us of the dangers of a continental city, he sent us back to our hotel rejoicing. For the greater part of a month we kicked our heels in Belgium, our anxieties only relieved by the letters we received from our fathers, approving our spirit but chiding us for our manner of leaving.

At last the great day came: we were summoned to the Embassy and told we had received commissions in the commissariat department; and though this was a come-down from what we had expected (I had already decided upon the Guards) it gave us the opportunity we desired.

I saw the great Duke in Brussels—only a fleeting glimpse of him, for he was greatly occupied. Napoleon was moving north, and on the day that Ney's soldiers tried to force the cross road we held at Quatre Bras, Harry and I were attached to a supply column, and were glad to forego the invitation we had had to the Duchess of Richmond's ball, this great ball being held on the very eve of Waterloo. The Duke attended, as did other leading military officers, for they did not wish to alarm the people of Brussels by their refusal. But in the dark of the night the Duke slipped away, and I saw him on the muddy road leading out to Brussels at six o'clock in the morning, a bent man with a great hooked nose and a remorseless eye. His spare figure wrapped in a black cloak, he went galloping past me with his staff trailing after.

Already, the night before, Harry and I had heard the low mutter of the guns in the distance; and now, on this morning of June 18th, I was to see the greatest battle of the century.

Our supply column was parked to the right of the British line, which occupied a ridge across the Brussels road. General Picton was on the left: that I well remember, because we could see Picton's soldiers from our position, which was half way between the forest of Soignes and the battlefield.

You must remember that our soldiers were only concentrated a day or two before the actual battle, and had not Napoleon wasted time after out-manoeuvring our army on the morning of the 16th, a different story might have been told. As it was, he beat the Prussians to the east of Quatre Bras, and they went back to Wavre. But his attempt to crumple up our line at Quatre Bras was frustrated. The soldiers say that the Duke of Wellington was "everywhere" that day. He was at Quatre Bras, and with the Germans, who had taken a very dangerous position, as was proved.

I have heard from officers that Napoleon expected Blucher would retire eastward to Namur, which was his base, and had calculated upon that development. But Blucher went north, and Wellington also withdrew his forces to the line he occupied on the morning of the 18th.

I shall not readily forget that morning. Sitting on my horse, Harry by my side, I looked across the fields of waving corn, the green of the clover harmonizing so perfectly, as nature alone does harmonize, with the ruddy gold of the growing crops, and wondered if it was possible that we were on the eve of a terrible battle. It had been raining heavily; the ground was wet; great pools stood in the road; yet the sodden British soldiers were just as cheerful and as happy as though they were at a village feast.

Our soldiers were placed on the slope of the ridge farthest from the enemy, so that they were out of sight of the advancing French. On the right front was a farm called Hougoumont, where the Guards were, as I discovered, for one of my first duties was to convey supplies to this point.

Before eleven the first guns thundered the arrival of Napoleon. From where I stood I saw the French infantry sweeping across the ground towards Hougoumont, and watched, with a curious, detached interest, but with my heart in my mouth, men falling here and there, until the line of the attack wavered and the force was streaming back to cover. But if I had thought the guns were terrible, I did not realize what gunfire meant until the afternoon. Harry and I were snatching a hasty lunch when the first roar of cannonade was heard. We were eating bread and cheese at the time, and we leapt on to a wall which partly sheltered us from observation, and saw the massed French columns coming to the attack, and the wonderful spectacle of British cavalry charging the retreating enemy.

At four o'clock came another attack, to our left, where Picton was, and here we saw the British form square and watched the attacking French army melt like ice. And then Harry suddenly turned.

"What is that?" he shouted, and pointed.

Far away to the left he had seen the flicker of bayonets. It was Blucher's German troops coming to reinforce Wellington's line; and they came none too soon, for, had Napoleon received the reinforcements he needed, the British line must have been pierced.

At six o'clock that night Harry and I had brought our wagons right up to the British line. Bullets were humming and flying in all directions, and the sights I saw sickened me of war for all time. The dead and dying lay unattended in the mire, and there were sights to be seen that one shudders to think about. I arrived at a propitious moment, for hardly had the stores been unloaded when I found myself enclosed in a scarlet ring of soldiers. Again the British had formed square to meet what Napoleon thought would be the irresistible charge of the Old Guard. Alas! many of his bravest warriors, who had followed his fortunes from the first day, through Italy to the Peninsula, men who had even survived the horrors of that retreat from Moscow, fell that day to rise no more. The charge of the Old Guard was scattered under the withering volleys which the untrained British infantry poured into them, and the day was won.

Nelson's Last Fight

WE have always had in our family at least one Member of Parliament. In the days of Charles there were two, as has been reported by my ancestor. It was my good fortune that my father, desiring that the tradition of the family should be maintained, secured me a seat in Hampshire with very little trouble, for he was a rich man, having an important business in India (then under the East India Company) which made a very handsome return. In those days Members of Parliament were not always freely elected by the people, but could buy their seats if they were rich enough or if their families' interests were sufficiently strong. In some such cases half a dozen seats in the House of Commons belonged to some great lord, who looked upon the income he derived from selling these seats as part of his proper revenue.

Mr. Pitt, sensible of this disgraceful condition of affairs, had desired to change it, but the monied interests were too strong, and what were called the "rotten boroughs" continued to send their members to Parliament. There were some constituencies consisting only of two houses that returned a member. Yorkshire, with its million of people, had two representatives, whilst little Rutland had as many!

Though I went into Parliament in the Tory interest, my heart was bent upon reform. None the less, I was not so enthusiastic as my cousin Harry, who, having, after the Battle of Waterloo, obtained a commission in the Army, had resigned in disgust when he saw a private soldier receive seven hundred lashes for using insulting language to an officer. He was what we came to call a Radical, being more Whiggy than a Whig, and in this interest he contested two seats, being defeated each time, preferring such a defeat to, as he said, the disgrace of buying himself into Parliament.

But here I anticipate, and passing over much in my own domestic history and bridging the gap of years, too lightly perhaps, though it seems that hardly had the Battle of Waterloo been fought and Napoleon sent off to St. Helena, there to die, than I was a grown man with a family. How that came about is too humdrum a matter to weary you with.

Harry married a lady of Hampshire, after returning from one of his long voyages, in which he visited Australia, the great continent which had been discovered by Captain Cook, and which was very useful to us (so I thought and said) as a place of residence for criminals we never desired to see again. Harry grew quite angry at this view, when I gave it.

"It is a most wonderful country," he said. "I wish that I could take these starving people of England and put them there to farm in freedom and happiness. To my mind it is a great stain on the Government that they can find no other use for this wonderful land than to plant their horrible convict settlements upon it."

There was indeed much distress after the war, for while fighting was in progress money was plentiful, the profits of the farmers were high, and the people in England had a very comfortable time. But with the war over, our markets gone, the restriction of spending, and all that follows a war, whether it be successful or unsuccessful, distress was everywhere appalling. Farmers were ruined, respectable journeymen found no work for their hands, and the nation seemed in a fair way to being reduced to beggary. It is strange, reading back over the numerous records of our family, how largely the King bulked in all these narratives, yet we scarcely noticed the death of mad George III., save to observe that his dissolute son had taken his place.

Kings have been hated and kings have been loved, and there have been kings and queens of England who have been ignored. But never, until George IV. came to the throne, was there a king who carried so great a weight of contempt as he, I went into Parliament in the year 1822, and my cousin might have had as safe a seat, as I have said before, but he was so full of indignation at the lot of our poor people that he refused to sit for a rotten borough, though, on the death of my uncle John, which occurred in 1820, Harry became a very rich man. For one thing, he hated Lord Liverpool and his Government, though I always found his lordship a very clever and discerning man and most obliging; he was undoubtedly narrow-minded, and he and his Cabinet were always smelling Robespierres in any demagogue who rose to protest against the conditions of the times.

Remember that the labourers of England were beggars, and that even the industrialists in the iron centres were hit; so that it was no wonder that there were little riots here and there, which the Government suppressed with unnecessary severity; as, for instance, when in August, 1819, they sent dragoons to charge an orderly demonstration, six persons being trodden to death. To make matters worse, there arose a stupid man called Arthur Thistlewood, who, with a small following in London, organized what was called the Cato Street Conspiracy, which was to kill Lord Castlereagh and all the Ministry. Thistlewood was hanged, as well as a few of his companions, and none wished to save him—for he was a vain fool as well as a villain, and such a combination alienates sympathy.

The only riot I remember witnessing was that which followed the return to England of Queen Caroline, the wife of George IV. She was rather silly than dissolute, more indiscreet than guilty; but when she announced her intention of returning to be crowned Queen alongside of King George, she having been separated from him for many years, the King induced Lord Liverpool's ministers to bring in a bill of divorce, and this turned the people in favour of the stupid Queen. For the life of George himself was so dissolute that it ill became him to cast stones at his consort, and there were great factions favouring the Queen in consequence. The Whigs took up the Queen's cause, and in one riot I saw a few heads cracked, though nothing serious occurred to justify the elaborate precautions which the Ministry took.

Such was the feeling of the mob that the bill of divorce was dropped, but the Queen continued to rail against her husband, and railed on until she died in the following year. Canning and Sir Robert Peel were in the ministry when I was first introduced, Lord Castlereagh, the Foreign Minister, having recently committed suicide, Mr. Canning taking his place.

Soon after I came to Parliament there was much ado about the condition of the Greeks, who were under threat of the Turks, and I remember meeting Lord Byron at a dinner given by one of the ministers, and learned that this famous poet was going to Greece to fight on the side of the people, as indeed he did, though whether he fought or not I have no knowledge. At any rate, he went out and died there, to the great grief of many who liked his works, though for myself I have never been greatly addicted to the study of poetry.

In the shortest time we saw Lord Liverpool stricken down by paralysis, and George Canning at the head of affairs, only to die a few months later. And then there happened one of the most unfortunate—indeed, I count it the most disastrous—happenings in modern history. The Tories, who still ruled the roast, invited the Duke of Wellington to form a Cabinet. The day the great Duke kissed hands on his appointment, I dined with Harry, who had come to town. I know not what it is about the Black Avons, but there is something impish and sardonic in them, so that they make a jest of the most sacred things, though I would not account the Duke such.

"So your Duke is to be Prime Minister," said Harry Avon, with a grim smile. "Sic transit gloria...! So passes the bright shield of a great warrior, to be fouled and smirched by base politics!"

"But he is a great man," I protested.

"A mighty soldier," said Harry, "and there never was a soldier except Bonaparte" (I cannot understand Harry's admiration for the Corsican) "who had the brains to govern and the wit to battle. Remember this much, my parliamentary friend, that a soldier knows only one kind of strategy, which is, first to hoodwink his enemy and then to destroy him. There are no blessed compromises in a soldier's equipment, or he is a bad soldier. To the Duke of Wellington the House of Commons will be a battleground, wherein he will dispose his impregnable defences, not to be scaled by force or betrayed by gentle words. Remember also that discipline and its need will play a great part in all the decisions he takes."

I pooh-poohed the idea, believing that the Duke was a much gentler soul than he had been described. But Harry's words, how true they were! Wellington knew too much of Europe, for one thing. He hated Whigs, whether they were in England or France, and began his term of office by violating one of Canning's pledges to Greece. And then, not understanding compromise and having it forced upon him, he yielded where he should have given a little ground and taken a great advantage, and was firm as rock on points where common sense would have told the average man he must give way or perish.

Nor did he merit the entire confidence of his friends, for, having opposed that belated measure of justice, the Catholic Emancipation Act, with the greatest vigour and to the applause of his friends, he suddenly turned about, admitted its desirability, and had the Act passed, thereby forfeiting a large measure of confidence which the Tories had in him. But for his wonderful reputation as a soldier, his ministry would net have lasted a session; and when, on the death of the King, unregretted and unmourned, there followed a general election, fifty of the Tory seats were lost, Wellington's ministry fell, and there came in the last of the Whigs, Earl Grey.

Of what he would do, none of us was as sure as my cousin.

"Here go your rotten boroughs, my friend," he said, rubbing his hands gleefully—we were in his library, for I was spending a short holiday with him, with my wife and two young daughters. "There they go into the bonfire which has consumed so many foul things."

"Grey will never dare introduce a Reform Bill—the Tories are too strong in the House of Lords," I said, this being commonly canvassed at Westminster. "Besides," I said, "the Whigs have always been talking about reforming Parliament. So long as I have been in the House—so long as we have read newspapers, Harry, we have heard of these reforming Whigs!"

"You'll see it now," said Harry firmly, and then, with a loud laugh, as he clapped me on the shoulder: "And I'll be at Westminster, and we'll be sitting on opposite sides of the House—it's a thousand pities you're a Tory, William, if indeed you have any convictions at all, which I very much doubt!"

It was very true that Parliament needed reform. As I have said, one of the constituencies which returned a member had scarcely half a dozen houses, whilst Birmingham and Leeds had no representatives at all. The little town of Appleby could send its member to Westminster, but Liverpool could have none. It was in '31 that Lord John Russell introduced the bill, but the members from the rotten boroughs were too strong and it was defeated by a majority of one vote. On this, King William IV., that bluff old sailor and hearty man, dissolved Parliament; Grey came back with a majority of 136, one of whom was Harry Avon, who got himself elected, as I learned, by bribery of the most villainous kind—but on the right side.

"It is true I bribed," he said when I dined with him the night the House came back—and a night of great excitement it was, with crowds filling the approaches to Parliament. "I have become Jesuitical in my middle age, and believe that a man should do evil that good may come. And I am here "—he slapped my knee, and he had the heaviest hand of any man I know—"to make it illegal that any member shall bribe constituents!"

The great Reform Bill was introduced again and passed—as far as the Lords. They, thinking their very lives as a legislative body depended upon their act, threw out the Bill, and the months that followed were full of the most furious agitation. There came into power a new party, an extreme wing of the Whigs (calling themselves "Radicals"), which had hitherto only appeared as isolated individuals but were now a party, vehement in their demand that the House of Lords should be abolished, and that all hereditary titles should go into the limbo of discredited things.

The agitation was such that the Lords passed the second reading, then set themselves, by altering this clause and that to render the bill valueless; whereupon Lord Grey resigned, and the King had to send for the Duke of Wellington.

I think at that crisis the old Duke realized how much more difficult it was to win an election and the confidence of Parliament and people, than to win a battle. He took some days to think it over, and then declined the task—very wisely, as we all think; leaving Grey to return, which his lordship did, on the promise of the King that, if the Lords did not pass the bill, he should be allowed to create sufficient peers amongst the Whigs to give him a majority in the Upper House. The mere threat of this was sufficient; the Reform Bill passed, amidst the jubilations of the people, who believed the Millennium had dawned.

The Bill disenfranchised fifty-six boroughs which had less than two thousand inhabitants in each; it gave a hundred and forty-three seats amongst huge centres of population, including Marylebone, Greenwich, Lambeth, Finsbury, and Tower Hamlets. It took away one member from thirty towns which before had two; whilst it gave two members to Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham and Newcastle. There were some agitators who thought that the Bill was not liberal enough, and would have had a universal suffrage; whilst more moderate men thought that the artisans and the agricultural labourers should have a vote, which of course they did not have.

Amongst my friends in the House of Commons was Sir Francis Burnett, who was greater still a friend of Harry's. We looked upon Sir Francis in those days as a dangerous agitator, and indeed some of his demands were fantastical, though Harry saw nothing remarkable about them except their honesty and their justice! So dangerous a man was Sir Francis regarded, that six Acts were passed against brawling and industrial riots, also against the Chartist movement (as we afterwards called it) for which he was responsible, and for which Harry himself used to speak with much vigour and eloquence.

"What do we ask?" said Harry. "Nothing but the rights of man—and don't turn up your silly old eyes at that, or tell me that I am mouthing the platitudes of the French Revolution. We ask for an annual Parliament, for voting by ballot, for manhood suffrage, and the abolition of the property qualification for Members of Parliament, and we ask too that Members shall be paid, so that the poorest will be able to afford to sit in the House of Parliament."*

[*Every one of these reforms have since been granted. —E.W.]

"But what you ask is madness," said I indignantly. "Manhood suffrage—you will ask for womanhood suffrage next!"

"That will come," said Harry, and I could only stare at him, believing that he had taken leave of his senses.

It was not till six years later that this extraordinary idea took more definite shape, when there was prepared what was called a People's Charter, demanding these reforms which I have already enumerated. All over the country there were huge meetings, attended and approved by thousands who had been disappointed by the operation of the Reform Bill; and so great was the fear of the people that a new French Revolution was coming, that special constables to the number of one hundred and thirty thousand were sworn in all over the country, and the troops were called out under the Duke of Wellington to prevent the Chartists from approaching the House of Commons with their petition.

In these days I greatly feared for Harry, who had flung himself into this mad fight with all the enthusiasm of his kind, who addressed meetings and wrote articles in the "Northern Star," and even went down into Newport and took part in a rising, though I believe he tried to pacify the rioters, one of whom, John Frost, being subsequently found guilty of high treason and condemned to death.

I must say that the years have somewhat softened my views about the justice of this demand, but certainly it was put in the most unseemly fashion, and I severely reproached my cousin to his face that he had lent his indubitable talents to misleading these ignorant people. He laughed.

But before the Chartist Riots, whilst, so to speak, they were but simmering, there occurred an event which must be a landmark in our history: William IV. died, and there succeeded him the young daughter of the Duke of Kent, William's niece and the grandchild of George III., Queen Victoria, that most gracious lady.

Harry addressing a Chartist meeting outside a factory.

I WILL say this of Harry Avon, that for all his thirty-nine years, he had the spirit and heart of a boy, though his own son was fast approaching the age at which his father and I saw the shambles of Waterloo. Little angered him, except perhaps if anyone cast doubt upon his having been present on that historic field. Then indeed he grew red and wrathful.

I had not seen much of him for the greater part of three years, when I had a letter from him by the post, which made me think at first that he had gone mad.

"This is a great country, O august Member of Parliament—how great you do not guess! Come down to my house here and see how a beneficent state leads children upward by the hands, so that there is no need to work and every labourer's cottage is like unto an Arcadia!"

What the mad fellow meant I could not guess, but I had a holiday on my hands and I went down into Hampshire, going part of the journey by the new steam railroad which was just then beginning to appear on every countryside. As usual, I was hospitably entertained. When I made a reference to his letter he put a finger to his lips.

"Wait, and you shall see," he said, mysteriously, and the next morning the mystery was explained, for we went down into the village and stopped at a labourer's cottage, where a man stood idling at the gate. He looked well-fed and prosperous, as did his wife.

"Well, John, have you done any work this week?"

The man knuckled his forehead.

"Yes, Sir Harry," he said, "I've done two days' work for Farmer Wilkins." Then he turned aside, as though he knew what my relative was aiming at, and regretted it.

"That is the Poor Law in operation," said Harry wrathfully. "Do you realize what you are doing with your cursed doles to the poor?"

I had not studied the Poor Law, but I knew that, by the Gilbert Act, any person out of employment was allowed to take from the parish funds as much money as would be necessary to maintain him. It seems that a scale had been fixed, so that when the price of bread rose, the allowance rose, and for every member of a family an additional dole was given.

"The main result is," said Harry, "that the farmers hereabouts, employers in towns too, have cut down their wages to these men, knowing that they are receiving sufficient poor law allowance to enable them to work for a little less than they would otherwise receive. The more children they have, the more money they get—poor rates are seven millions a year, my good friend!"

I confess this was a shock to me. And when, later, Lord Grey introduced a Bill to give only the destitute and the old parish relief, and to force the able-bodied to go into a workhouse, I gave him my support. It was in this year that slavery in our colonies was abolished, the planters being compensated with a sum of over £20 for each man and woman freed.

I have spoken of the steam railway—a great novelty in these days. An engineer, Stephenson, was the inventor, but there was great difficulty in getting the necessary Bills through Parliament to make what was called "a railway system" possible. The first railway bill was thrown out of Parliament because the projected line threatened to pass too near to the coverts of a duke!

A man with whom we came into contact during the early period of our Parliamentary comradeship remains with me (and Harry confessed the same) as a most important memory. We had become acquainted in one of those literary salons which held sway at the time, with a young author whose name was on every lip, and whose eccentricity of attire excited the risibility of the curious.

How strangely wrong can be one's first impressions! An even more erratic genius, Mr. Theodore Hook, introduced him to us with these words: "You will hate this young man because you do not know him. If you know him you cannot hate him."

The person to whom he brought us an acquaintance was a very overdressed young man, obviously of the Jewish persuasion, Benjamin D'Israeli, who had written a book called "Vivian Grey." I shall never forget my first impression of that extravagant dandy. He wore green velvet trousers, a canary coloured waistcoat, low shoes with silver buckles, and had lace at his wrists. He was in the habit of wearing his rings over his gloves, and a more unpromising individual I have never met. He was a brilliant talker, and I believe it was then his intention to stand for Parliament.

His views were unusual, and I quite expected, when the party was over, to hear Harry break into a tirade against this dandified young man. But, to my surprise, whilst he was amused at the extravagance of D'Israeli's dress, he was deeply impressed by the young man's genius.

"I think he will go far," said Harry. "He has courage and a very wide knowledge of humanity."

"He is a hopeless fop," said I, nettled.

"I doubt whether his appearance makes very much difference," said Harry drily. "He certainly does affect odd clothing, but the man is a genius and I shall look forward to his appearance in Parliament."

We met D'Israeli after he had failed to carry a seat at Taunton, and we were both present in the Marylebone Police Court when D'Israeli appeared there on a charge of contemplating a breach of the peace. He had, it seemed, challenged O'Connell to a duel and had been arrested in his bed by police officers in consequence.

It was in 1837 that D'Israeli appeared in Parliament, and made a speech so full of wild and flurried phrases that the House laughed him down. D'Israeli was white with anger, and, shaking his fist at the House said:

"There will be a time when you will hear me!"

For a while his vehemence was directed towards a clever young Oxford man, William Ewart Gladstone, who had already been marked out for an important position in the Government.

"Gladstone." he said one day, when he was walking with me in the lobby of the House. "He is brilliant, I agree, but a sophist of the worst kind! Mark how in his maiden speech he rose and, with a gesture, took up the challenge which had been flung down by Lord Howitt!"

D'Israeli was not in the House at this time, but I remember the circumstances well. Howitt, who was afterwards Lord Grey, had opposed a resolution making for the abolition of slavery, on the grounds that it went too slowly towards its object, and he had instanced certain happenings on the plantation of Sir John Gladstone in Demerara. Gladstone's father was a slave-owner on a large scale, and William had felt it necessary to defend his father, and whilst he professed his belief that slavery should be abolished, he desired that the slave-owners should be properly and amply compensated.

"Property," he said, "is an abstract thing; it is the creature of society. By the legislature it is granted, and by the legislature it is destroyed."

Whether D'Israeli had any very strong views on the subject—or would I not better say 'very sincere views'?—it is difficult, indeed impossible, for me to state with any certainty; but I think he was sincere enough in his suspicion of Gladstone, whose maiden speech was undoubtedly designed to protect his family's interests and to afford an apologia for the practice of slavery.

We watched with interest the progress of these two men, consciously or unconsciously rivals for the highest position in the land, both destined to occupy the most important offices of state. Of the two, it seemed that William Gladstone was the more likely to succeed, for he was a member of an old English family and was closely associated by tastes and instinct with the class which has governed England for centuries. D'Israeli was not only suspected by those unthinking people who look with suspicion on a Jew, but also by politicians who mistrusted so volatile a genius. He was known to be in desperate financial straits, was in the hands of the moneylenders, and his extravagance, at one period of his career, brought him to the verge of ruin.

"I will tell you this about D'Israeli," said Harry when I spoke to him of the rumours I had heard. "He may be in the hands of moneylenders, but he has never borrowed from a friend, nor has he involved his friends in any of his financial transactions. Half his trouble comes from his good nature and generosity—D'Israeli has probably backed more bills than any other member of the House of Commons!"

Harry and I sat through many parliaments, happily on the same side of the house. We saw Peel succeed Melbourne, and Melbourne succeed Peel, who came back again to pass the Repeal of the Corn Laws. Under Lord Derby, Harry might have had a post, but his erratic political views made this impossible.

In this year his wife and his only son died of malignant fever, and with a courage which was worthy of his greatest ancestor, he met the crushing blow without faltering. Resigning his seat in Parliament, he went abroad, and the first I knew of his plans was when I had a letter telling me that at the age of fifty-one he had accepted a position on the staff of the Indian Army, and that he hoped that "you will one day visit the country from which you draw so many profits "—a sly reference to the source of my income, which was the Indian business founded by my father, and which had lately increased to such an extent that I had already considered the possibility of a visit.

IN the year 1853 the demands of my Indian business became so pressing that it was necessary that I should journey to this wondrous land, with the object of appointing new representatives and of opening new factories at Meerut and Delhi, both of which were prosperous centres of trade and had the advantage, from my point of view, of being garrison towns where I should meet men of my own nationality. Moreover (and I am sure that this was the greater inducement), there would be a chance of seeing Harry.

I confess that I was very concerned a few mornings before my departure, when my dear wife passed me a copy of "The Times" across the breakfast table and showed me a letter which was printed there. It was from General Jacob, a well-known and highly respected officer, and stated that the Bengal Army was practically in a state of mutiny.

"There is more danger to our Indian Empire in this condition of the Bengal Army and the feeling which there exists between the natives and the Europeans, and thence spread throughout the length and breadth of the land, than in all other causes combined. Let Government look to this; it is a serious and most important truth."

At this my wife was greatly perturbed.

"I can't allow you to go to India with the country in that state," she said, but I laughed at her fears, though I was by no means happy in my mind.

To make the story of a long voyage short, after many weeks of travel, during which we suffered storms about the Cape of Good Hope, we arrived at last in the wonderland of India. How can I describe my confused impressions of that strange, beautiful, and yet to me—oppressed by a sense of the power which lay behind the teeming millions of natives—terrible country? Even though it is a recent experience, my first impression of India is one of vivid confusion, if those terms, which at first seem contradictory, may be employed. The white buildings, the blue, cloudless sky, the long, straight roads that led through jungle and across the face of the cultivated land, the spicy scents of the Orient, the strange people of all castes and races...it is difficult for me to convey even a modicum of my amazement and delight.

I reached Meerut on a blazing hot day, and set out in search of Harry, whose headquarters this was, but who, I learned, had been away on a shooting trip and was not expected back for three or four days. I was made comfortable by the manager of my factory, and had quite enough to engage myself during the period of waiting. And then one morning a sturdy form came striding across the floor of my office, a white kepi on his head, with along cloth at the back to protect his neck from the rays of the sun, and in a second I was shaking hands with Harry, brown and thin of face, whiter of hair, but as cheerful as ever.

We had tiffin (as they call luncheon) together, and then it was that I discovered that, despite his boisterous good humour, he took a grave view of the situation. I did not learn this till I mentioned Colonel Jacob's letter, and then his face instantly grew serious.

"It is perfectly true," he said quietly. "I have been talking to some of the British officers commanding the native regiments here, and there isn't one of them who believes that his men are trustworthy. I have written in the same strain to old friends of mine in Parliament, but they laugh at what they call my fears!"

"But this is astounding, Harry," I said, in dismay. "What is the cause of the unrest?"

Harry shrugged his shoulders.

"There are a dozen causes," he said, "and at present, thank heaven! there is no one cause which affects them all. The Sowars" (he explained that a Sowar was a native cavalryman) "are ripe for anything because they are in debt."

I was mystified at the idea of a private soldier being in debt, and that that fact menaced the security of the East India Company. But then he told me that the soldiers were recruited on what they call the "Sillidar" system, by which they had to provide their own horses and provisions. In return they received a monthly wage, which very often was not enough to pay their debts. I then began, dimly, to understand.

"Yes, they're all in debt," said Harry, very calmly. "They have to go to the moneylender to get the wherewithal to buy their horses in the first place—there isn't a Sowar, whatever his feelings may be against the British, who would not howl with delight at the prospect of a revolution which would enable him to cut the throat of the moneylender and wipe out his obligation!"

I thought at first he was jesting, but I learned later that this was no more than true. Harry went on:

"The Hindus are disaffected because of the Persian War, for fear that they will have to cross the water and lose caste. And the Indian princes are sulky, because of Lord Dalhousie's scheme of annexation."

I had heard something of this before I had left England. Lord Dalhousie, the great Governor-General, had enacted a law by which, if a native prince had no direct heir his estate went to the Company. As it had been the practice from immemorial time for natives to adopt children and leave their property to their adopted sons, the new regime was regarded as an imposition, especially by those young "princes" who had been adopted into rajahs' families for the very purpose of possession.

"And now," said my cousin, in despair, "Dalhousie's scheme has annexed Oudh; and as most of the infantry in Bengal come from that State, you can imagine what they are feeling."

"But surely there are some loyal natives?" I asked.

Harry shook his head.

"There are—a few," he said significantly. "But we, in our curious British way, have managed to antagonize not only the Hindus but the Mohammedans. The Brahmans are up in arms over the prohibition of suttee—they like to feel that when they die their widows will burn themselves to death—oh, they've all got their pet grievances. I'll tell you this, cousin," he said soberly: "if Britain was in a European war just now, and she got badly worsted, or didn't succeed as well as she might, I think the loss of prestige would precipitate a general uprising."

I must say that Harry's views were not those held by other officers I met in the course of my stay both in Meerut and in Delhi. One or two old officers, men who had been colonels for years and were holding lucrative positions, pooh-poohed the idea. When I told Harry, he laughed sarcastically.

"Those old fossils simply dare not believe there is likely to be a rising. I assure you that there are more incompetent senior officers in India than there are in any other part of the world."

It was, I thought, one of Harry's typical and hasty generalizations, but alas! history was to prove that he was not far wrong.

I returned to England six months later, with a very uneasy feeling and a fervent hope that the trouble, if it was to come, would develop before I was due to return. From now on it was obvious that my presence in India was imperative at least every other year.

By the time I had reached England, however, there were other matters to occupy my attention. The mutterings of the war guns had been heard in the Near East; Russia and Turkey were already fighting; Great Britain and France had made the Turks' quarrel their own. The year I returned, Britain and France declared war on the Czar, and we might have had a first-class conflict in the Balkan Peninsula if Austria had not gathered a strong army and, without declaring itself hostile to the Czar, placed that army in Transylvania, right across the Russian line of communication. This ended the war, such as it was; and now Europe was scared of what was called the Russian menace. For the Czar had destroyed the Turkish fleet, and was fortifying the Crimean coast, with the object, as it was believed, and, indeed, openly stated, of seizing Constantinople and securing for himself an ice-free exit to the high seas. This had been Russia's ambition since the days of Peter the Great—a port that was free of ice all the year round. For this Peter and his successors had made war, but as the fear of Russia in the Mediterranean had invariably drawn the other European powers together, the plan was invariably defeated.

In point of fact I knew just what turn events were taking, for I had the satisfaction of meeting Lord Palmerston one evening at a dinner given in honour of the young Prince of Wales, Albert Edward. His lordship told me then with the greatest frankness, that Britain and France could not tolerate the creation of great forts on the Black Sea.

"The Russians have retired to their own country," he said, "but it is only to gather strength to launch themselves again at Turkey. We must close that fort at Sebastopol and the Russian Navy must be destroyed, or we shall have war in Europe continuously for the next twenty years."

At this time the third Napoleon was on the throne of France, having secured himself that position by very much the same method as his illustrious ancestor, Napoleon Bonaparte, had followed—namely, by a coup d'état. Napoleon was one with the Queen's Government, and he sent an important army to assist the Turks and the British, and before we realized what was happening, the troops were marching through England on their way to the ports and the ships that would carry them to the cruel, bleak desert of the Crimea.

News came by the electric telegraph of early successes, and we learned how the British had landed at Old Fort and had forced the River Alma, and of how, having outflanked the Russian field defences, they had reached the south of Sebastopol and were firmly established, covering the harbour of Balaclava. The British and French guns were thundering against the great fortress of the Malakoff, battering that defence to pieces by day, only to discover, with the coming of morning, that the Russians had repaired the breaches, making it as strong as ever.

Throughout these operations I was thanking heaven that Harry was safe in India, and you may imagine my surprise and fear when one morning the postman placed in my hand a stained letter bearing a field postmark which told me that it had come from the Crimea, and I recognized Harry's handwriting. As it happened, it was an historical document...

"Protecting our siege batteries which are hammering away at the Malakoff, we have a long line of defence—too long for safety—which is called the Vorontsov Bridge. Three days ago Liprandis carried our centre, but happily our heavy cavalry were on the site and charged, sending the Russians flying. About this time a very strong force of Russian cavalry rode down on the 93rd, expecting to annihilate them. But these gallant Highlanders stood in a single line, and by the steadiness of their fire brought the Russians into confusion. Here we call the 93rd the 'thin red line.' Thin indeed it was, but it was like a granite wall which could not be overcome...The day, however, was marred by one great tragedy. The Light Brigade, as we call the lighter regiments of cavalry grouped under Lord Lucan, were being held ready to be thrown in, as some say, though others who knew Lord Raglan's intention, deny this. At any rate, an aide-de-camp took a message to Lord Lucan with orders that he was to prevent the withdrawal of guns which the Russians had captured in their assault on the ridge. Without hesitation the Light Brigade went straight for the Russian guns over a mile and a half of shell-swept ground, and though they were cut down by hundreds, reached and spiked the guns, some of them going beyond into the enemy's cavalry—an amazing achievement, though, alas! fraught with the gravest loss to our forces, for only a third of their number came back..."

Though he did not tell me, I learned afterwards that Harry took a wonderful part in the battle of Inkerman which followed, on November 5th, eleven days after that disastrous charge of the Light Brigade. The battle of Inkerman was initiated by the Russians, who had been very heavily reinforced, and they now struck at the junction between the British and the French divisions. It was a melee pure and simple, every man fighting his own battle without orders, whole regiments and divisions inextricably mixed up, so that Highlanders were fighting side by side with dismounted cavalrymen, and generals, sword in hand, fought shoulder to shoulder with privates.

Throughout the terrible winter that followed, when the British soldiers were starving as the result of their supply ships being wrecked in a storm, when they went almost barefooted through the snow to their post, and endured the most terrible hardships that the mind of man can conceive, I heard nothing from Harry, and my anxiety increased, until one morning it was relieved by a letter written from Portsmouth, where he had arrived.

"...I cannot tell you the horror of that siege: the mud, the snow, the abject misery of our poor British soldiers, who, despite all their sufferings, stood up cheerfully to their duty. Cholera has decimated the French Army, and our own poor fellows are suffering terribly from sickness. Happily there arrived at Scutari a brave English lady named Miss Florence Nightingale, who has brought nurses with her and is doing wonderful work to succour the sick and wounded."

I journeyed down to Portsmouth to see Harry, and found him the wreck of the man I had known. But such was the buoyancy of his breed and the amazing recuperative power of his years, that within four months he was not only well but anxious to go back to that dreadful shambles, in which the British alone lost forty-five thousand men, and the Russians two hundred and fifty-six thousand. Happily, the fall of Malakoff and the signing of an armistice prevented any further anxiety on my part. Harry came up to London to dine with me and my wife, and he told us he was leaving by the next available ship to take over his old post at Meerut.

"You remember what I told you about; how in the event of a serious setback to British arms, there would be a danger of rising in India?" he asked.

"But surely, Harry," I said in surprise, "you do not call our glorious victory in the Crimea a setback?"

He shrugged his shoulders.

"I suppose it is a victory, but we have been too long getting it, and we have had the assistance of the French. A man I met who has just come back from India told me that the news of our many failures and the state of our army is common talk in the bazaars."

"Does bazaar-talk matter?" I smiled.

He shook his head.

"I don't know," he hesitated, "only—I'm glad I'm not serving with a native regiment."

I cavilled at this.

"You're trying to scare me from coming to India," said I.

"Indeed I'm not," he replied earnestly. "Though I'd be mighty glad if you came out soon—and went away sooner! And if you will follow my advice, you will make no heavy commitments in regard to your factories, and you will postpone the buildings you contemplate until—well, until things settle down."

This was not a very cheerful point of view, and I would have gladly gone to India right away, only I saw the cowardice of such a step and realized that, even if I went immediately, I must make another trip two years after, for I was by no means sure of my manager, an Eurasian.

"I understand the natives," said Harry. And then, with a laugh: "Perhaps it is because I myself am a Black Avon! I know what they will do on certain occasions and I pretty well guess how they feel in normal times. Once you meet the native in his abnormal mood, however, it is beyond the mind of man to appreciate either his thoughts or his intentions."

He gave me a curious illustration.

"Have you ever seen a charpati?" he asked, and, when I said no, he told me it was an unleavened cake, which was never eaten but passed from hand to hand. "That charpati is a message. What the message is, no native can reduce to words. But we know from sad experience that the arrival of a charpati in a village means trouble. At the sight of that unleavened cake, whole communities grow agitated and dangerous, but knowing this, we know no more, and it remains to this day as mysterious a message as it was in the days of Clive."

HARRY went back to India a few days after this little talk, the purport of which I concealed very carefully from my wife.

It was not until the winter of the following year that I set sail on my second visit to the East. My health was none of the best, and I was glad to escape the rigour of an English winter, as also was my wife, who accompanied me as far as Cape Town, in the Cape of Good Hope, a British settlement that had once been Dutch, and was a port of call for travellers to the East. At this period a M. de Lesseps was soliciting subscriptions to a scheme for cutting what was called the Suez Canal between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, to shorten the journey to India—a project which, Lord Palmerston told me, was a physical impossibility.

The ship stayed long enough at the Cape for me to see my dear wife settled in a delightful part of the Cape Peninsula called Wynberg. At the last minute she begged me to take her on to India, but I thanked heaven with all fervency that I did not accede to her request.

It was on a very pleasant January morning in the year 1857, with a blue sky overhead and a gentle breeze tempering the warmth of the day, that I arrived in Meerut. Glad I was, after my long and tiring journey, to get to the cool, big room that had been put aside for me in my manager's house. The green sunblinds were drawn; the punkah overhead moved rhythmically, controlled by an old man who squatted outside the door and pulled ceaselessly at a string which communicated with this great fan. Here I was, stretched in a deep chair, a cool drink on a table at my side when the same old Harry that I had known, looking none the worse for his terrible experience in the Crimea, came in to greet me, having missed me on my arrival.

"Well," I said, after the first greetings were over, "have you had your great mutiny?"

"N—no," he said slowly, "and I hope we shan't, till we get back some of the troops we sent to the Crimea."

I had not realized that India had been largely depleted of its soldiery to reinforce the shattered British battalions in the Crimea.

"We've less than forty thousand white soldiers, and there are a little more than a quarter of a million Indian soldiers," said Harry tersely, and, clapping his hands to summon my bearer, as we called the Indian personal servant who attended to me, he ordered a long, cool drink.

"What do you do with mutinous troops?" I asked curiously.

"We haven't had a mutiny since '42, which was long before my time," he said. "But if you have sufficient white troops, it is possible to put the rebellion down without much difficulty. Look at this," he said.

He put his hand in his pocket, took out an object as long as a man's finger, which was wrapped in tissue paper. This he carefully unfolded, revealing a cartridge.

"What is that?" I asked.

"That's a very ordinary cartridge such as the Sepoys use. Put your finger on it."

I did so and found it smooth and greasy.

"Cow's fat or pig's fat," said Harry laconically. "The incredible folly of it! Do you understand that the soldier has to put that in his mouth to bite off the end?"

"But are you sure it's cow fat?" I asked, instantly alive to the awful folly of the authorities.

"Whether it is or isn't, doesn't matter," said Harry, replacing the cartridge in his pocket. "The doctor of the regiment stationed here says there is no doubt that both pig's fat and cow's fat are used to grease these cartridges. Of course it is necessary that they should be greased, to fit into the new Minie rifles. The cow, as you know, my dear fellow, is the sacred animal of the Hindu; the pig is abhorrent to every Mahommedan; so the brainless gentlemen in charge of our ordnance department have succeeded in mortally offending both Mohammedans and Hindus and bringing them for once into line."

"But surely it can't be fat from—" I began.

"It is," said Harry emphatically. "We have unmistakable proof that the tallow used to grease the particular cartridges I have shown you is made from the pig! The cow is probably a figment of the Hindu's imagination, but we can swear to the porker. And, what is more, the Mahommedans know it."

He told me there had been a little rising at Barrackpur, near Calcutta, the year before, and that the regiment involved had been publicly disbanded.

"And punished?" I asked.

"No," said Harry thoughtfully. "Lord Canning, the present Governor-General, is a great man, but he doesn't believe in punishment. And in many ways he's right, for undoubtedly the trouble in Barrackpur arose over these cartridges. And there will be trouble here."

He spoke so emphatically that I felt a little chill run down my spine.

"But you've troops here?" I said.

"We've a lot of native troops," said Harry, "but our great weakness is our dear old General, who has as much initiative as a cabbage."

He told me that there were two regiments of native infantry, one of cavalry, and a strong mixed force of British.

I had plenty of opportunity of meeting his brother officers, and indeed I dined at every mess in Meerut. Curiously enough, I found all the officers of native regiments confident of the loyalty of their men. General Hewitt, who commanded, was one of those who scoffed at the danger, though he had warning enough; for, a month or two after I had arrived, and when I had booked my passage back to England, and was looking forward to rejoining my wife at Wynberg, there occurred an incident which must have been the very writing on the wall to any man of common sense.

One morning I learned that a large number of the native cavalry regiment had refused to accept their cartridges, and in the following week, after the court-martial—whereat they were sentenced to ten years' penal servitude—I saw them stripped of their uniform on the public square and marched off to gaol. This was on a Saturday, and I had arranged with Harry to join him at church on the Sunday evening and to mess with him after the service.

The troops were drawn up on parade without arms, when suddenly, from the native lines, came the rapid sound of rifle fire. It grew to a perfect torrent of shooting. Presently I saw a figure staggering across the square, blood streaming down his face, waving his hands and signalling wildly. By the time we reached him he was in a swoon, but we recognized at once that he was an officer of one of the native infantry regiments; and when, later, he recovered, he told his story.

The native regiments had shot down their officers to a man, and even now were plundering the European dwellings. Fugitives began flocking in to the lines; and in this crisis, when a man of resolution and courage might have stamped out for ever the great mutiny which was later to paralyse India, we found the General commanding paralysed with astonishment, incapable of doing anything except waiting for something to happen. The troops were soon armed and on the alert, but no effort was made to quell the mutiny, and the mutineers streamed, a disordered crowd, towards Delhi, where they were joined by the King of Delhi's own soldiers.

The little garrison at Delhi made an effort to defend itself, and the great magazine was blown up by Lieutenant Willoughby, with himself, and the ten soldiers who defended their post to the last.

In the meantime the electric telegraph enabled us to warn other posts, though this communication was soon interrupted; for the whole province was now in revolt.

I had already taken up my residence within the lines. There we were safe, for the mutineers had practically abandoned Meerut. Harry came to me on the second night of the tragedy, almost weeping in his helpless rage and grief.

"We are sitting here doing nothing," he stormed. "Hewitt will not move—the man is helpless and hopeless! If he were a coward we could shoot him, but he's not! He is just stupid, and there is no death penalty for stupidity!"

And indeed this was no more than the fact, for not until a month later did the Meerut troops march out to join Bernard, and then we learned for the first time the extent of the mutiny. Delhi was in the enemy's hands, and was besieged by a small British force, though it is truer to say that it was the British who were besieged and not Delhi; until first the Meerut troops, and then John Nicholson's forces, joined us—and the gallant little party which occupied the ridge before Delhi.

It was on September 14th that we made our attack, and strange indeed it was to me, a peaceful merchant, to find myself black of face and grimy of body, unshaved for a week, rushing forward, rifle in hand, to scramble through the Kashmir gate, which two brave engineers had blown up. But there were older volunteers than I, for I was fifty-eight at the time, and I remember seeing an aged Indian merchant, his long white beard floating to his waist, shoot down two of the King of Delhi's soldiers who had killed one of our officers. It was after six days' fighting that the town was taken, and the King of Delhi was made prisoner, his sons being shot by Hodson, of Hodson's Force, without trial, as I understand, though I only know the rumours that floated about.