RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

The Black Avons IV: Europe in the Melting Pot

George Gill & Sons, London, 1925

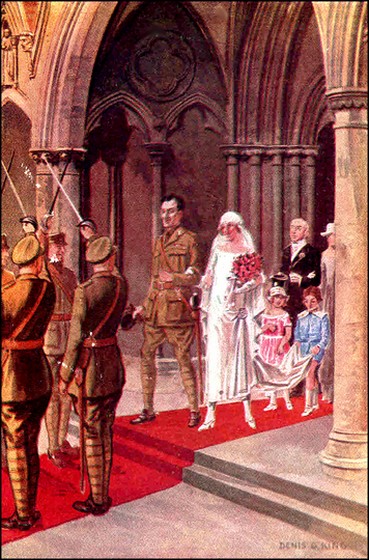

The Black Avons IV — Frontispiece

IT is almost inconceivable that there should be in our family a Black Avon who was, for any reason whatever, an unpopular figure. They have for scores of generations been built in an heroic mould; a shining light of their time, and their memories have been hallowed by all who bear our name.

My niece, Lorrain Avon, crystallized the peculiar change of attitude in one pungent, if somewhat vulgar, sentence.

"The boys simply cannot stand an Avon who works for his living," she said. "They think that a Black Avon who doesn't spend his life gadding over the earth, sticking his sword into some poor, wretched enemy, isn't the real thing!"

"Lorrain," I said severely, "your language is becoming deplorably lax."

My brother, Sir James Avon, is not what I would describe as a broad-minded man, and he shares the views of his two sons, Hubert and Stanley, that this Avon, who had suddenly dawned upon us, was indubitably a true Black Avon who would have satisfied the most exacting of critics, but was nevertheless a black sheep.

Of the new Harry. Avon's existence I don't think any of us were previously aware, except in a vague kind of way. He belonged to that branch of the family which had settled in India and had moved on to the Cape. Harry's father had been something of a recluse, maintained no correspondence with the other branches of the family, and had offended my brother to an unimaginable extent by sending his boy to England to be educated, without notifying any of us of his intentions. So that Harry Avon was living under our noses, so to speak—he was at Oundle School, one greatly favoured by our family—and none of us was the wiser. And then, when we had almost forgotten that there was a South African branch, Harry Avon comes from South Africa, buys Manby Hall, adjacent to my brother's estate, and, without so much as "by your leave," begins to interest himself in the welfare of the village.

"In fact, he trespassed on our preserves," said Lorrain, with the ghost of a smile, when she told me this. "Daddy likes to feel that he is the feudal lord of Manby, and he is simply furious that Cousin Harry should have bought the estate, which carries with it the lordship of the manor. As a matter of fact, father intended buying the Hall, and that wretched London agent promised to give him the first refusal. I met him to-day in the village."

"Whom—your father?"

"No, Harry. And really, he's quite a nice man: very tall, horribly black, with a cold sort of blue eye that makes you shiver. I was sufficiently lost to all self-respect, as I have been told repeatedly, to go up to him and tell him that I was his cousin."

"And was he cold and stern and haughty?" I asked, with a smile.

"No, he was simply charming. When I asked him why he hadn't called on us, he said that he had no idea there were any Avons left in England!"

She rocked with laughter at the cool audacity of the man.

"And, Uncle John, he is terribly rich, and full of the weirdest ideas about this country. He says there is going to be a great war."

"What does your father say to that?"

Lorrain made a little grimace.

"What would father say to any view which did not coincide with his own?" she demanded. "Harry has been for two years on the Continent—father didn't know that. He's been travelling through the Balkans, Austria, Germany, Russia and Russian China, and he is full of this idea of war. What do you think about it, Uncle John?" she asked, a little anxiously.

"Pooh!" I said contemptuously. "How can there be a war? The world is governed by humane and intelligent men. There may be threats and sabre-rattling, but that sort of thing is part of the diplomatic game. I have not served in the Foreign Office for twenty-five years without knowing that, Lorrain."

She was silent at this, and then:

"I told him about you, and he wondered if you would come to the Hall—he said he would like to meet a Foreign Office official for whom he had some reverence!"

I laughed.

"The young dog ought to call on me, unless his bump of respect is abnormally under-developed," I said. "But I am no stickler for the proprieties, and I will call on him at the first opportunity I find."

My work in Whitehall was not very strenuous, for, as head of a department of the Foreign Office, my hours were not long. And the opportunity was at hand, because my brother invited me to spend a week-end with him at his country place in Norfolk. I drove through the little village of Manby, saw the white lines of Manby Manor as I passed along the road, and wondered what sort of material this new Black Avon would provide for a poor scribe.

Many years ago it had been laughingly said by some of our family that I should write the story of the next Black Avon; but during all the fifty-five years of my life no Black Avon had arisen to succeed that brave man who fell in the Indian Mutiny. There were red Avons, one of whom fulfilled the prediction of the old prophet who said: "Red Avon a lord, Black Avon a sword." There were fair Avons, and, alas! there were now a few grey Avons! But the Black Avon of romance had not yet crossed the horizon, and I could not help thinking, a little ruefully, that this young man who had arrived so annoyingly from South Africa, and had obtruded himself upon our lives, was likely to be very unpromising material indeed.

When I reached Avon Place I found that the question of the new Black Avon occupied the minds of my brother and his family to an extraordinary extent.

"What do you imagine the young beggar has done?" demanded James furiously. "He has had a meeting in the village, and raised a sort of glorified Boy Scouts team amongst the elder boys! He says that war is coming and that they should be truly prepared! He takes them out on long walks and gives them lectures on military subjects. War, indeed! He is a publicity-hunting young scoundrel! And he hasn't even so much as been to this place to leave his card!"

"Perhaps he doesn't understand his responsibilities to the great family," I said good-humouredly. "And, anyway, James, isn't it our business to call on him? I've been tracing his history this morning, and undoubtedly he belongs to what I call the major branch of the Avons."

"Stuff and nonsense!" said my brother violently.

"It may be stuff and it may be nonsense," I replied, "but here is the fact, that the home of the Avons is in Hampshire."

"The real home of the Avons is in Norfolk," insisted Sir James.

"In Hampshire, old boy," I said gently, and I was prepared to trace back the family to the days of Stephen to prove my words, but he knew very well that what I said was true.

"I don't care whether he's an old branch or a young branch or a mere tine! He's been out of England so long that he's not entitled to be in the family at all," said John illogically.

"He's an awful bounder too, Uncle," Stanley put in. "He's gassing all the time about Germany and how efficient she is."

"Have you heard him?" I asked.

"No, but I've heard it from other people. He had a meeting in the village the other night and talked for two hours."

I asked if "the foreign Avon," as my brother insisted upon calling him, was popular in the village, and I was rather amused when James growled something about "publicity hunting," and gathered therefrom that the strange Avon had won his way into the affections of the countryside.

"Why he should be popular I don't know!" exploded James. "He's a fellow who doesn't hunt, hasn't a single friend amongst the county families, and has already succeeded in antagonizing half of them."

It appeared that Harry Avon had very much annoyed the sitting member, Sir Wilbraham Stote, who was what my brother, a most hard-shelled Conservative, described as "a respectable Liberal." It appeared that Harry had attended the meeting which Sir Wilbraham held every year in order to keep in touch with his constituents, and had asked a lot of ridiculous questions about the state of Europe.

"State of Europe indeed!" snorted James. "Europe is in the same state it has always been and always will be. This German Emperor fellow is no bad sort. I met him at Kiel three years ago, and he was quite charming to me."

I might have told James that, however much they bulked in the public eye, kings and emperors were not always as powerful as they appeared to be, and that usually there was somebody behind the throne of a semi-despotic monarchy, who directed affairs, pulled wires without the least compunction about who would suffer at the other end, and generally maintained in themselves and their associates the real government of the country.

It was rather a queer coincidence that I should be in Norfolk that night when Harry made one of the few attempts he had so far initiated to soothe the ruffled feelings of my brother. A footman brought a note asking us if the whole family would dine with him that Saturday night, or, alternatively, if we would go over after dinner.

"At three hours' notice!" spluttered James. "Good heavens! what does he think we are—?"

It was Lorrain who came to the rescue. There was a very level head on those young shoulders, and her brother never failed to insist that it was she who dominated the house.

"We'll go after dinner, darling," she said to her father. "I'm most anxious to meet him at close quarters. And really, it would be the civil thing to do. He is one of our family—"

"Fiddlesticks!" her father scoffed.

Nevertheless, he sent a somewhat ungraciously worded message back to the effect that he would be at the Hall at nine o'clock.

We drove over in my car, a fairly large party to descend upon a bachelor; but I verily believe that, if we had been five hundred strong instead of five, Harry Avon would have shown no surprise.

He came out into the big hall to greet us: a thin, brown-faced man, with calm eyes and perfectly carved lips. They were almost too good for a man, as Lorrain confided to me afterwards.

But I am one of those crusty bachelors who think that nothing is too good for my own sex. His voice was low, and, to my surprise, cultured (I don't know why on earth it shouldn't have been but somehow one visualized him as being a little uncouth); and my first impression was that he was a man who missed nothing. When Lorrain's cup was put down it was he who was instantly at her side to take it away; when James felt in his pocket for his gold matchbox to light one of his excellent cigars, it was Harry who was immediately at his elbow with a match.

I think James was mollified both by his deference and by his obvious knowledge of affairs. He was older than I had expected—nearer twenty-eight than twenty-five (as they had first told me)—and he had a queerly incisive—perhaps decisive would be a better word—way of discussion which in any other man would have irritated me.

OF course, James pooh-poohed all his theories, but I, who had an inside knowledge of Europe, though I couldn't openly confirm his views, knew that he was speaking nothing but the truth.

Inevitably we came to the question of war. James, on his way over to the Hall, had confided to me that he intended stopping that sort of absurd propaganda.

"Now come, come, Harry Avon," said James, who is, I confess, a little pompous and patriarchal in his manner, "you do not seriously mean that are going to have a world war?"

Harry nodded.

"With whom?"

"With Germany: that is certain."

James smiled.

"Do you seriously mean to suggest," he asked deliberately, "that Germany is secretly preparing to fall upon the nations of Europe and destroy them? Is that what you say?"

Harry had a musical little laugh, very soft and very amused.

"I said nothing of the sort, Sir James. They talk war and they think war, but the cause of that is mainly psychological. After all," he went on, as he flicked the ash of his cigarette into a shallow silver tray, "if you are governing a nation it is your job to watch out for all eventualities. And if you think war is inevitable, it is equally your job, not only to tell your people so, but to imbue them with the idea that they are the greatest military nation on earth, and that, if war comes, they have nothing to be afraid about."

"That's sheer boastfulness," said James.

"Not at all. We do the same sort of thing when we sing 'Britannia rules the waves!' The psychological effect is that we believe that Britannia rules the waves, and that, whatever happens, we can never be defeated at sea."

I broke in here.

"You think then," I asked, "That Germany is preparing for war?"

"For the possibilities of war," he corrected.

Probably I did not make myself quite plain, but I explained to him that what I meant to ask was: was Germany's intention to provoke war? This was a matter which had been the subject of many discussions at the Foreign Office.

He laughed again.

"I'm afraid you are using too limited a term. Where does provocation begin? If is very difficult to trace any war to an immediate cause. For example, who would trace the Crimean War to the threat of the Austrian Emperor against the Russian Army? And what was the provocation in the Franco-Prussian War? The immediate provocation any school history book will tell you. But I submit that the real provocation went back to the days of Merovingian kings! Alsace, for example, has been German in language and religion, off and on, since the twelfth century. No, what the German rulers have done is, as I say, to prepare for war; and war, of course, is inevitable, for no one reason, but for many."

He had a trick of walking up and down the room with his hands behind him, an old Avonian habit, if our ancestral scribes are to be believed.

"In Germany," he said at last, "they say that France is provoking war, and they point to the group of statuary on the Place de la Concorde, representing the lost provinces, which is everlastingly smothered with flowers, to the society which exists to keep alive the memory of French humiliation in 1871, and to the constant pinpricks which France, more wily in the way of diplomacy, has administered to the German diplomats. You people forget that the German, although he is a brilliant scientist, an amazingly clever philosopher up to a point, and probably the most industrious person in the world, is tremendously insular. For example, he can never understand the psychology of other nations, and he truly believes that there is a movement on foot to encircle him. He points first of all to the French and Russian offensive and defensive alliance, for that is what it amounts to. So long as that existed—"

"And a very good thing too!" snapped James, sitting bolt upright. "The French and Russian alliance is the salvation of Europe."

Harry Avon looked at him thoughtfully for a moment, and then:

"Or the destruction," he said quietly, and added in haste "I am not suggesting that either of these nations designs the destruction of the existing system. But in Germany they are certainly regarded as a provocation. What will happen now, when the third side of the triangle is closed?"

He sat down, took out a gold pencil and a piece of paper from his pocket, and drew what was roughly an isosceles triangle.

"Along this line is France, along that line is Russia, stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea on the one side, and from the Black Sea to Calais on the other. Here"—he made a semicircle about the base of the triangle—"is the sea. And now you have closed that to Germany, in the sense that Russia and France have concluded—not an alliance, it is true—but an understanding."

"Don't talk absolute rubbish!" said James, who was inclined to be more than a little choleric. "We intend no harm to Germany: we are looking after ourselves. We must keep the peace of Europe. And thank God, King Edward has succeeded in establishing the Entente Cordiale!"

The Black Avon said nothing to this. I have a shrewd idea that he had pretty well sized up James, and knew how valueless argument was with my poor, illogical brother.

"The point is, Sir James," he said at last, "that Germany looks at the matter from one angle and we look at it from another. We say of Germany that it is planning world domination; it says that sooner or later it must fight for its life, to destroy two enemies, one of whom is obsessed with a desire for revenge, and the other actuated by a sense of fear. Germany and Russia are afraid of one another: let that sink into your mind. You're at the Foreign Office, are you not, Sir John?"

I nodded.

"Would you endorse what I say?"

At this I laughed.

"You wouldn't expect me to endorse any statement affecting foreign policy," I said good-humouredly, and the Black Avon was amused.

"Are you suggesting," asked James in his most awful voice, "that there is a conspiracy between these three great nations, France, Russia and England, to crush Germany out of existence, and that war will be deliberately made?"

"I suggest nothing of the kind. Wars are seldom deliberately made, nor are they engineered at the will of one man or one nation. They arise out of stupid and uncontrollable circumstances. Look at the position in South Europe! Three nations, the Serbs, the Greeks and the Bulgarians, hating one another like poison, and all loathing the Turks! Bulgaria, with a German prince; Serbia, a veritable hotbed of political intrigue. I can tell you this, that I wasn't in Belgrade two days before I discovered that it was the centre of a Slav conspiracy to keep the Serbian population of Austria-Hungary in a state of constant ferment. From Belgrade these incitements to mutiny against the Austrian Emperor are going out all the time. There is a lot to be said for the Serbian attitude; there is just as much to be said for the Austrian. The awful thing about wars and their cause is that no side is, hopelessly wrong and no side is absolutely right! Austria is watching events all the time, conscious of the agitation which is being aroused against her, filled with resentment and a desire to punish these Serbian conspirators who are seeking to dismember their empire. And the queer thing about it all is that the agitation against Austria is justified!

"Do you suggest," I asked, "that the Serbian Government connives at these plottings against Austria?"

And to my surprise at such an action in so grave an individual, Harry winked!

"The Serbian Government know nothing officially. But one of these days something will happen that will drag the rulers of Serbia at the tail of these irresponsible conspirators; and when that happens, the fat will be in the fire! Russia regards herself as a sort of guardian angel of all the Slav nations. The moment Austria attacks Serbia, Russia will intervene. The moment Russia is mobilized, Germany must come to the assistance of her ally. It is very simple—action and reaction! A political chemist who knows the formula will tell you into exactly what position every country in Europe will driven."

As I drove home that evening I was a little puzzled by the Black Avon. At first glance he seemed to me what we subsequently called a "pro German"; and had those views been expressed during the terrible years that followed, he would have been denounced and probably imprisoned. But in war time, under the emotional stress which war brings, one's perception becomes a little warped, and perspectives shift, so that it is almost impossible to judge any view sanely. When a nation is at war there is only one side to any question, and that is the side one is on.

I liked the young man much more than I had expected. But James was very bitter about him.

"He comes here with these high-falutin', socialistic, nonsensical..."

I will not attempt to reproduce his adjectives.

"...to hear him talk you would think that everybody was wrong except Germany."

"That is not how it struck me," I said, in justice to Harry. "It rather seemed that he was taking a very clear-headed view of a situation which might develop terribly."

James looked round at me sharply, in some surprise.

"Do you seriously mean that?" he asked, troubled. "I thought the Algeciras Conference had settled all outstanding difficulties?"

"It has settled nothing," I replied.

He was referring to the conference which was called by the Powers and which was to define the various spheres of influence in Morocco. France and Spain had equal claims; Germany had sent a warship, rather provocatively, to remind the French that she also had nationals in Morocco and that she might conceivably demand a share in the settlement of that disturbed and ill-governed country. It was little more than a gesture, since for the moment there was no possibility of Europe allowing Germany to establish herself in Morocco and it served only to remind the French that Germany would not submit to any act of aggrandisement on their part, and indeed the outcome of the conference was the surrender by France of a slice of the French Congo in return for Germany's agreement to the claims of France.

Poor James has not what I would call international mind, and I explained to him patiently and rather laboriously, I am afraid, just all that Algeciras Conference had stood for. There was of course a chance of war at that period, but nobody desired the war less than France, who was unprepared, and was at the time replacing her artillery with that now famous gun, the 75.

Lorrain, who had listened entranced to the political outline which Harry had drawn, was silent all the way back to the house, and then, when her father had gone into the library, she took me aside in the hall.

"Don't you think he's splendid Uncle?" she asked.

"I think he's very interesting," I said carefully.

"Interesting! He's wonderful!" she breathed. "And I'm sure what he says is perfectly right, and Daddy's a dear old silly."

"What do Hubert and Stanley think?" For two boys had accompanied us. Hubert was officer in a cavalry regiment, and Stanley, who was at Sandhurst, was going into the Guards.

Lorrain laughed.

"Hubert loathes him," she said, with a twinkle her eye. "Apparently Cousin Harry said something about the uselessness of cavalry in modern war, and of course Bertie will never forgive him that! And naturally, if Hubert loathes him, Stanley will loathe him worse."

We attended service at the old village church on the following morning, and to my surprise I found Harry there. Lorrain told me that he had never gone before, to her knowledge, and wondered why he had taken this unusual step. When I suggested that she might possibly be the attraction, she seemed annoyed but I am perfectly sure was not.

I HAD thought a lot about him him that morning, and in the afternoon I took the car and drove over to Manby Hall. As a rule, a Foreign Office official does not take a great deal of notice of views expressed by youthful amateurs. We have our own sources of information, and they rarely fail us. But I was rather impressed, not only by his sincerity, but with the assurance of this young man (I was by way of being a cousin of his, but when we got to know each other better he never called me anything but uncle, and that title I very proudly accepted).

He was walking up and down the broad terrace when my car came into view, and descended the stone steps to meet me.

"Curiously enough, I wondered whether you would come," he said, with a twinkle in his eye.

"You didn't expect my brother, I presume?"

"Sir James? Hardly! We do not speak the same language. And it is only natural that we shouldn't." And then, without any warning he asked me bluntly: "What do you think of Grey?"

I stared at him.

"You don't mean Sir Edward Grey?" I asked incredulously, and he nodded.

One would hardly expect that a permanent official of the Foreign Office should give an immediate and perfectly frank answer about his political chief, but happily I was in a position to do so.

"He is a very strong man," I said, "and a very human man."

"Strong?" He frowned. "I wonder how strong? I have an impression of him as a being who is rather gentle, and inclined to compromise—the latter quality is all to the good. Have you any idea of his views about a Continental war? I realize I am asking you something that I should not ask, but I thought that, perhaps, being a relative of mine, you would trust me."

Without giving me chance to reply, he took my arm and we walked into the house.

"You see, Uncle John—I'm going to call you Uncle John, though I don't suppose you're any such relation—"

"To be exact, I'm your third cousin," I said humorously, "but I'll accept 'uncle' from you as a compliment."

"The fact is," he continued, "I am a very rich man: an enormously rich man. I have a diamond mine which is practically my own, and I am the proprietor of the newly discovered goldfield of Southern Angola. You hinted last night that you have sources of information which give you an advantage over me. Let me tell you that I can command even more reliable agents, for the simple reason that we have a big selling organisation in this country, the agents of which are paid much better than yours, and on the whole I think are a more competent service. And my information is that there will be war in three or four years."

This was not a statement to be turned with a jest. He was, I knew, immensely wealthy; indeed, the company of which he held the majority of shares had recently put up an office building in the City of London at the cost of half a million, and I knew, too, that these financial houses paid well for information and commanded a truly wonderful service.

"Germany can't wait any longer," he went on. "They are scared sick at the thought of common action between France, Russia, and Britain, or what they call the encirclement of Germany. And there is a lot to be said for their point of view. It is in vain that I have urged upon some of their best friends—Ballin, the great shipowner of the Hamburg-America Line, Stinnes and other great leaders of industry—that the present entente between Russia, France and England is the fine guarantee for the peace of Europe. The business men in Germany agree, but they say that there is a section of our Press which is determined to present Germany as the menace of Europe, and that the combination against them is an offensive one."

"What did you reply to that?"

Harry shrugged.

"One cannot argue with national prejudices," he said. "And how could I in honesty? We in this country believe that Germany is aiming to dominate the world; and when you take that view to an intelligent German, he is in just as helpless a position as I am! He simply cannot argue with what he believes to be a lie. And yet we may both be telling the truth. There may be a substratum of fact in his contention that France has her mind fixed steadfastly upon a policy of revenge, and has organized a circle of enemies to destroy the German nation. There is certainly more than a substratum of truth in the fact that we in Britain are alarmed and worried and concerned by these constant threats and bellicose utterances of the German Emperor. But, my dear uncle, that is part of his job! He is the glorified advertisement manager of German strength and German purpose. He rattles the sabre as the showman bangs his drum—he is very much in the position of a man who, seeing himself approached by three enemies, as he believes, threatens them individually in order to prevent co-operative action between them all."

He asked me a question about Mr. Asquith, and he agreed with me in my view of that statesman.

"It is one of the popular lunacies of this country, and indeed of most countries,—that patriotism is the monopoly of a party," he said, and told me that he had had breakfast with Mr. Lloyd George, and had met Mr. Winston Churchill at a reception. "Personally," he said, "I believe that the mischief is done, and that there is no Government of man's contriving which could avert the disaster. The suspicion of the Germans in England, the suspicion of the British in Germany, are factors beyond remedy."

I went back to London the next morning, rather impressed with the warning note that the new Avon had sounded. My talk with him on that Saturday afternoon revealed many side issues, if such they can be called, which were new to me. I never realized that the Serbian Government could possibly be implicated (even "unofficially") in the agitation which was going on in the Austro-Hungarian empire. I knew, of course, that there was a very large number of discontented Serbs in that country, and that there had been one or two outrages committed by foolish and fanatical men. And of course the complaint on the part of Austria that these outrages were mainly initiated in Serbia with the connivance of the Government, was fairly familiar.

The position in the Balkans was a peculiar one, and in 1912 was to become even more dangerous. In this year Serbia and Bulgaria, Greece and Montenegro combined against their old enemy, the Turk, and succeeded in driving him back to Constantinople. Here a useful purpose might have been served, and the Turk as a menace to European security have been eliminated, but unhappily the Balkan States quarrelled over the spoils of war, and in the end Bulgaria had to defend herself against her former allies and to receive from their hands a much smaller portion of the conquered territory than she would have got had she agreed immediately after the Turk was defeated. This left a very discontented Bulgaria, bitterly estranged against the Serb, who was Russia's chief protege, and insensibly inclining towards Austria and, through Austria, Germany.

Another result of the war was the loss of French prestige in Turkey. The Turkish Army had been reorganized and re-armed by the French, and on his failure the Turk naturally visited his resentment upon his French instructors. Here the Germans came in, and very shortly German officers were organizing the Turkish defences; a new entente had sprung up between Turkey and Germany, and favoured the great German project, then in course of fulfilment, of a railway across the Mesopotamian desert, linking up Bagdad with Berlin. Brought to its logical conclusion, this policy would eventually bring a railhead to the very frontiers of India, and the project had given us very considerable concern at the Foreign Office.

In those stormy months I had very little time for paying visits, but when I went down to see my brother in the summer of 1912 I learned that Harry had left immediately on the outbreak of war, and was in Constantinople. This news came, suspiciously enough, from Lorrain, and when I taxed her she brazenly admitted that she was in correspondence with the "forbidden cousin," as we called him.

"And why shouldn't I be?" she asked, a little defiantly. "Somebody in the family has got to be decent to him!"

Very wisely I did not pursue the subject, but left the matter where it was. Her father knew, she told me, and apparently his silent disapproval made little or no difference.

I was surprised and rather pleased, after the second war, and when I was deeply involved in dealing with that section of Europe, to have a visit from Harry on his way through London. He looked very brown and fit, and after the first greetings were over, in his jerky way he came to the point which was at that moment troubling me, and, I think, troubling every other man who took an intelligent interest in European politics.

"Queer thing about the Turks," he said. "Did I ever tell you, how in my opinion the war which Italy forced on Turkey with the object of taking Tunis and that strip of the North African coast would lead ultimately to big issues?"

I didn't remember. I have often had the impression that he had favoured Lorrain with a great deal more information and more news than she had confessed to me, and that in all probability he was confusing us, though that is hardly likely.

He ticked the position off on the tips of his fingers.

"First of all, we have some years ago Turkey fighting and defeating Greece. Then Italy steps in, takes the Turk's North African possessions and weakens the Turk to such an extent that the Balkan states can combine and finally smash him. They had him like that!" He put out his thumbs suggestively. "And yet they didn't sail in and finish him because they have the morality of brigands, and each was afraid that one of the others was going to get more out of the show than they did!"

"How did you leave Constantinople?" I asked.

"With a very sore head," said the Avon, taking the chair I pushed up to him. "Very sick of France, very friendly with Germany. I left the Russian Ambassador greatly alarmed at the project of this new German influence making itself felt."

"The Turk has no reason to complain," said I. "He got off much lighter than he would have done if the Balkin allies had agreed amongst themselves."

"They never will," he smiled quietly. "As for Bulgaria, she's seething with discontent, and naturally king Ferdinand is all for finding a solution to his country's troubles—in Germany. With the Young Turkish party now in control of Constantinople, tending in the same direction, there is a German streak running from Wilhelmshaven to the frontiers of Persia. I wonder how long it will be before—" he said thoughtfully.

"What?" I asked.

"War," was his startling reply. "All the conditions are favourable. Germany is building Dreadnoughts and super-Dreadnoughts to keep pace with our ship-building programme—Lord! what a mess it's going to be!" he groaned as he rose.

"Are you returning to Norfolk?" I asked.

"Yes, I'm going back to organize an agitation to increase the number of our machine-gun detachments. Germany has four to our one, and machine guns are going to count in the next war."

"But why should we be in it?" I asked. "We have no alliance with France."

He turned round and stared at me.

"You guarantee the neutrality of Belgium."

"The Germans will never invade Belgium," I protested.

Harry laughed, as though I had said something funny, and I was a little nettled.

"Of course they'll invade Belgium," he said scornfully. "How else can they deploy their divisions? Practically the whole of Eastern France is barred by the Vosges mountains and on the north-east by the Ardennes. There is only one manoeuvring ground in the whole of Western Europe, and that is the plains of Belgium! The German would be beaten in the first month of the struggle if he didn't deploy through Belgium."

"Break a treaty?" I asked. To me a treaty was a sacred thing.

"How many have been broken in the past, by almost, every nation? There isn't a school history book that won't tell you that. Necessity knows no law, and it is vitally necessary, for the success of the German forces, that they should wheel their right wing across the Meuse."

"I am afraid I cannot take such a light-hearted view," said I. "A treaty is a solemn obligation, and I do not doubt that Germany will respect her written word."

Young Avon smiled.

"Fail, and jeopardize the future of seventy million people for a line of writing? My dear uncle, you do not know anything about war," he said. "Of course she will come through Belgium, and equally of course we shall be dragged into he war."

I READ these notes that I have made in the early stages of the great and terrible conflict which overwhelmed the world, and Harry Avon's views seemed so false in ethics and in fact, that I had it in my mind to destroy them and to hide up, what I considered to be, his perverted view. But these chronicles are written that future generations may read, and I have left them substantially as I noted them down after each interview, and it will be for posterity to judge the accuracy of his conclusions. We cannot, in the midst of a great war, while the thunder of its cannon still reverberates in our ears, when we see the great plains of white gravestones that mark the resting-place of our dead, when around us we see the widows and the fatherless, the cripples and the men blinded and driven mad by war, we cannot, I say, judge fairly or accurately of first causes. It may be that Harry Avon was hopelessly wrong; but I must confess that at the time I was deeply impressed by his reasoning.

He had made at least one convert. I met him one day in town with Lorrain. They had been to a theatre to see a play by Major du Maurier, called "An Englishman's Home," which, in my judgment, did a great deal to imbue in the minds of unthinking people a realization of the potentialities of war.

Events followed so quickly that it seemed but a day between the conclusion of the Balkan trouble and the opening of the conflict. It was in the month of May, 1914, one Sunday night when I had been dining with James and his family at their house in Sloane Square, that the dreadful news came. Harry had been invited. I think that the advocacy of Lorrain had done something to temper my brother's violent and prejudiced view against our young relative. But so far, neither Hubert nor Stanley, who had got his commission in the Coldstream Guards, had been reconciled to what they called "his beastly socialistic views."

It was a curious coincidence that as we sat at the table after dinner, James should raise the subject of a book he had recently read—a translation from the German. It was written by General von Bernhardi, and it dealt with what he called the next war.

"A devilish clever book," said James approvingly. "I must admit that these German fellows are smart. Their espionage system is wonderful—"

"Their espionage system," interrupted Harry, "is deplorable! I should say they have the worst intelligence department in Europe."

That was the annoying thing about Harry: he invariably took the opposite view to the popular one, and generally was right.

"And as for Bernhardi's book, it's full of the grossest miscalculations. For example, he thinks that, in the event of war with Britain, neither our Territorial Army nor our overseas forces would have the slightest effect upon the issue."

"Nor would it," said Sir James gruffly. "The Territorials are very good chaps, and it's an amusing way of spending a Saturday afternoon dressing up like a soldier and doing sham fights and things of that sort, but they wouldn't be much use in war. As for the Colonials," (Harry always winced when James said 'colonial' but he groaned now) "I mean the soldiers from the overseas states—they're very fine fellows indeed, but what army could they put in the field?"

"Half a million," said Harry promptly, "and probably more."

James gaped at him.

"Then in the name of heaven, how many could we put in the field?"

"Between four and five millions; that is to say, ten per cent. of our total population."

Here Stanley was moved by the arrogance of youth and the consciousness of his military calling to protest.

"What good would they be?" he asked. "It takes five years to make a soldier."

Harry grinned.

"Five years to make him drill; twelve months to make him fight," he said. "Unless my knowledge of the British people is at fault, you will be able to make soldiers quicker than you can equip them."

It was at this moment that my brother's butler came in and told me I was wanted on the telephone. It is not very usual for me to be called up on Sundays but I went at once, and as I took up the receiver I recognized the voice of my chief clerk. He was evidently very agitated.

"Is that Sir John Avon?" he said. "A dreadful thing has happened. The Crown Prince of Austria and his wife have been assassinated at Serajevo!"

The news stunned me. Of course I was aware that the Archduke Ferdinand was paying a visit to the Serbian portion of his future empire with his heir apparent, and that he was accompanied by his wife. There had been threats to murder him, though one did not take those too seriously. And now the blow had fallen.

I learnt the details of the crime in a few minutes.

"Very well," I said: "I will be at the office in half-an-hour."

I went back to the dinner table, and I saw Harry's eyes on my face.

"What has happened?" he asked quickly.

"The Archduke Ferdinand and his wife have been assassinated," I said, and he sat back in his chair and whistled.

"This is the end," he said in a low, grim voice. "Nothing can stop war—it is the one excuse that Germany wanted. She will nudge Austria, and Austria will make the position of the Serbian Government impossible. Not all the talk in the world, not all the negotiations, can avert this conflagration."

He spoke with the solemn tone of an oracle, and I shivered as I listened. His prophecies seemed almost inspired. I saw Lorrain turn pale and her anxious eyes go to her two brothers.

"Not war?" she asked, in a voice little above a whisper.

Harry nodded.

"War and nothing but war: there is no alternative," he said, and got up from the table.

There was a pallor in his face which was impressive. He stood looking at us, and yet looking through us, as though his extraordinary mind were running hither and thither, thinking and correlating facts.

"I wonder if the French are ready," he said, as though he were speaking to himself. "That is the keynote. If the French do not make not a spectacular invasion of Alsacce, but stand on the defensive until we are ready, we might win."

He went down and got his car and drove straight away home, whilst I went on to the Foreign Office. The reports that came in the next morning were encouraging. The attitude of the Austrian Government seemed restrained and conciliatory. Belgrade had telegraphed its horror and regret, but not all the passage of telegrams could entirely wipe out the fact that the murder was undoubtedly organized by men who were well known in the city of Belgrade.

Day followed day, and the calmness of Vienna was reassuring. I had many interviews with Edward Grey and found him extraordinarily clear-headed and sane about the affair. He was by no means certain that the crisis would pass and leave Europe where it was, but his hope, I think, was centred on von Bethmann-Hollweg, the German Chancellor, who, some of us believed, was strong enough to keep in check the militarist element in Berlin.

On the Saturday following the murder, just before I left the office, I was told that a soldier wanted to see me.

"What sort of soldier?" I asked.

"A private soldier," was the reply, and, thinking it might be a message from the War Office, which was keeping closely in touch with events, I asked that the man should be sent in.

Judge of my surprise when there walked into my big room Harry Avon, in the uniform of a private of the West Kent Regiment! Apparently he knew some officers in that distinguished corps, and had been recruited on the Monday previous.

"But, my dear fellow, this is very precipitate on your part."

"I want to get time to shake down before things get to a state when we shall have the whole of British manhood flocking to the recruiting offices," he said. "I may, by a piece of favouritism, get my corporal's stripes in a month—fortunately I hold Certificate A: I took it at school, and with that I can get commission if an opportunity arises."

I looked at him admiringly.

"At least you have the courage of your convictions," I said, and asked: "Does Lorrain know?"

He nodded.

"I've just left her. We had lunch together at a fashionable West End restaurant." He smiled mischievously. "The manager took a lot of convincing before he admitted me to his gilded hall, and I prophesied that, by this time next year, these gentlemen will be falling on the neck of any I man they meet in khaki."

He had come, he said, to ask me to be a trustee of his will.

"I have already anticipated your agreement, and the document was signed this morning," he said.

He did not tell me how he had disposed of his money. I learned afterwards that he had left me a very considerable sum, and that—well, it would not be fair to Lorrain for me to say what provision he had made for her and her brothers.

The interview was a very brief one, because he had to be back in barracks at midnight. He said he had a lot of things to do, arranging for his house to be run in his absence, and, in certain eventualities, to be turned into a convalescent home for soldiers.

I had little time to think of Harry during the weeks that followed. The war clouds were gathering ominously over Europe, and the tone of the German Press left me in no doubt that she was behind the unknown ultimatum which would sooner or later be presented to Serbia. When that ultimatum was published, it sent a gasp of amazement throughout Europe. It was no less than a demand that Serbia should surrender those sovereign rights which are dear to every self-governing community, and submit her will to her hated enemy. That Serbia should submit to this was impossible, and those who prepared the ultimatum, which was telegraphed word by word and may have been shaped by the German Emperor and his advisers, knew very well that the conditions imposed would never be accepted.

From the moment that ultimatum appeared, war was inevitable, though Sir Edward Grey worked with the energy of despair to find some alternative to war. The German mobilization plans were ready to be put into force at once. Russia, who considered herself the natural guardian of all Slavs, began her preparations, but the mobilization did not take place for some days afterwards.

There is no sense in quibbling and quarrelling as to who mobilized first. It was inevitable that secret instructions anterior to mobilization should go forth as soon as a breach seemed unavoidable.

The Germans had built a nest of railway lines to the very frontiers of Belgium, and the existence of these great depots, which could not possibly be excused on any other than military grounds, was well known to us. When mobilization was ordered, German troop trains began to move towards Belgium.

War was actually declared against Serbia on July 28th, 1914. On August 1st, at 7.30 p.m., Germany declared war upon Russia; the German troops, waiting on the frontier, invaded the neutral state of Luxemburg, seized the railway and established a base against France.

In the meantime the gathering of German troops on the Belgian frontier caused the Belgian Government to demand whether Germany intended holding by her agreement to treat the country as a neutral state; and this question was submitted by Sir Edward Grey both to the French and to the German Governments. The French replied instantly in the affirmative, and indeed there was no reason why they should not, for a neutral Belgium would protect their left flank. Germany's reply was evasive. Sir Edward repeated his question, demanding a reply by eleven o'clock that night, German time.

This was on August 4th, and by this time Germany had already demanded of the Belgians that they should remain neutral and allow them to deploy their forces through the country. On the day that Sir Edward asked for a German assurance that the neutrality of Belgium should not be violated, two German army corps, under General von Emmet, were already hammering at Liege; and that night British ministers waited in silence, hoping against hope that at the eleventh hour Britain would not be dragged into the war.

No reply came, and as Big Ben struck midnight the Great War had begun for our people: a war which was to entail the most terrible sacrifices of life, which was to desolate a million homes and bring us to the very verge of extinction and ruin.

"If," said Sir Edward Grey, "in a crisis like this, we ran away from those obligations of honour and interest as regards the Belgian Treaty, I doubt whether, whatever material force we might have at the end, it would be of very much value in face of the respect that we should have lost."

MANY of us will remember to our dying days those first hot days of the war, when our railway services were disorganized and train after train passed southward, crowded with cheering troops; young men in the very heyday of life who were going out to face a fearful death that we might live unmolested, untrammelled by a foreign conqueror. For myself, those first hours of war were hours of terrible solemnity. I think I was fortified by the presence of a girl who had so much to lose, and was in dreadful fear that the loss could not be averted. Lorrain had come up to my house to dinner that night—it was a holiday—and towards midnight she and I went into a church and sat down in that empty place, tenanted only by a few worshippers, and waited for the clock to strike.

How magnificently our people met that hour of supreme peril! With what a resolution, what a calm courage! To-day, when the war is almost a memory, I recall that immense crowd of volunteer soldiers which gathered about Scotland Yard, waiting patiently for its turn to go before the doctor and pass the necessary examination which would admit them to the Army. To-day, when I meet some working man who annoys me, some driver of a lorry who obstructs my car, some person who is rude to me in the street, I never reply, for fear that unconsciously I may be saying something bitter to one of those heroes who offered their bodies as a living rampart between the enemy and our homes.

The position on August 5th was this: our own army was beginning its mobilization, and an army of Germans had practically taken Liege, and there was no barrier to their progress across the Meuse. He was sending his army corps through Belgium, though his progress was necessarily slow, and made slower by the poverty of his military intelligence; for it was understood by German Army Headquarters, as I subsequently learned, that a British army had landed somewhere near Ostend. In point of fact there was nothing at Ostend more formidable than a strong detachment of marines, but whether the Germans knew or did not know this, it is certain that time was lost till the right of the advancing divisions was made secure from any possibility of attack from Ostend.

In the meantime our troops were being transported across the Channel as fast as ships could carry them; the concentration was completed seventeen days after the outbreak of war: a remarkable performance, even with our own little army, which, it was generally believed, had been referred to by the German Emperor as "the contemptible little army of General French." I might say in passing that there is no documentary or authentic support for the statement that the German Emperor said any such thing. In point of fact, as I happen to know from a very authentic source, the Kaiser had warned his staff officers not to regard the British Army too lightly.

By August 21st the British Army had taken up a position along the line of the canal from Conde in the west through Mons to Binche on the east, the 2nd Corps, under that brilliant general Sir H. Smith-Dorrien, being on the left, and the 1st Corps, under Sir Douglas Haig, on the right. The 3rd Army Corps had not yet arrived in France.

At this juncture of affairs, when war was declared, Mr. Asquith had recalled Lord Kitchener, who was on his way back to Egypt, and asked him to take control of the War Office. Lord Kitchener had a name that was famous throughout the land, and his influence upon recruiting was a vital one. He was not, by any standard, a great general, his forte being organization, and his real value, as I say, his extraordinary personality, which had fascinated Britain since the days of the Sudan War.

On Sunday, the 23rd, the battle opened, an attack being delivered in the main against the 2nd Corps, though the 1st Corps was also heavily engaged. At this time Sir John French, who was in command of the British troops, believed, as he had been informed by the French intelligence department, that he had only one cavalry division, and one, or at most two, enemy army corps before him. His troops were hardly engaged before he learned that there were three corps on his front, two of them actually engaged, the third moving to envelop his wing. Worse news than this came; for on French's right were two reserve French divisions and the 5th Army, and he had no news of what was happening to these until he learned that they had retired.

Fortunately, the British Army had a few but very efficient aeroplanes, and the Field-Marshal was able to discover the real strength of the situation, and when this became revealed, he ordered an immediate retirement, and there began that Retreat from Mons which has become historic.

All this news, however, did not come to us at once. We knew nothing, except a favoured few of us who had heard that there had been a heavy engagement and that our troops were retiring. It was a great shock to many, though how they could have imagined that our handful of men could have held up these superior forces, is difficult to understand.

From time to time I had scraps of news and tried to piece them together. Harry, I knew, was in the thick of it, but what was his fate I did not learn till a staff officer who had come over from the War Office to consult with my chief, asked me if Sergeant Harry Avon was any relation. At first I had a qualm of fear that he might have been killed, but apparently some detailed news had come through from the Commander-in-Chief, and it appeared that Harry had, single-handed with a machine-gun, held up the German advance near Maubeuge for half an hour, allowing our troops to be extricated from an impossible position.

"His name was mentioned, so I suppose you'll hear more of it," he said, and congratulated me when I told him of Harry Avon's relationship.

We heard from the other front. The Russian armies had broken into Eastern Prussia, and Berlin was so alarmed that it ordered the reinforcement of the eastern front by a corps which was withdrawn from Belgium but did not arrive in East Prussia until too late to be of service. There had been placed in command of the German troops a remarkable old man named General von Hindenburg, whose knowledge of the district was such that, by sheer manoeuvring, he was able not only to defeat but in a great part to destroy a superior number of Russian divisions.

In France the Germans were moving rapidly towards Paris. General Joffre, the Commander-in-Chief, had, however, prepared a line of defence, whilst the commander of Paris sent a division out in taxicabs to attack the enemy in flank. Von Kluck, who was commanding the right of the German Army, discovered these forces on his right flank, and edged his corps over westwards to meet the new danger. In so doing he left a sensible gap between his own army and the army on his left, and General Foch, who was before him, saw his opportunity and sent his troops forward to the attack.

The position was now so impossible for the German that he had no alternative but to retire to the line of the Aisne and the high ground behind that river. The Battle of the Marne has been glorified and described as a miracle, but though there was a general engagement, the retirement of the German, whilst it was forced upon the enemy, was voluntary in the sense that the German armies were not driven back, but decided to retire in order to re-establish the solidity of their front.

The little British army was now exhausted, but their recuperative powers were extraordinary. I doubt if there was ever any army of Britain that was the peer of that small, compact force which, having marched and fought for two hundred and fifty miles, were able, in the shortest possible time, to return to the attack. Whilst the British were resting, preparatory to a hasty re-organization, I had my first letter from Harry.

"Have you ever seen an army in retreat? It is not a terrible sight if it is a British army. I had a moment's chat with General Smith-Dorrien, who fought a magnificent battle at Le Cateau to check the German advance and give our men a little breathing time, and he said that it reminded him of nothing so much as a huge crowd coming away from a football match, and that, I think, just described the sight. All sorts of units were mixed up together. There was no question of marching in fours or in files; they just trudged along cheerfully, helping one another, turning back to fight under any strange officer that ordered them, as cheerfully—indeed with greater cheer—as they would have shown if these had been manoeuvres. There was no grumbling, no grousing; they were footsore and hungry, but cheerful to the last; and as they marched they sang a song called 'It's a Long Way to Tiparary.' Will you get a copy and send it to Lorrain? We are in for a very stiff time. The Germans are in a strong position on the Aisne, and I doubt if we shall be able to turn them out for years! Please do not faint at the thought that the war will go on for a year or two—nothing is more certain than that; if we drift into a state of position warfare, we shall not be able to turn these fellows out of France. Some their regiments fought magnificently, but you can't really beat our Tommy—he is the most wonderful soldier in the world."

It is almost impossible to record the history of that terrific combat in such a way as to show the great story in one picture. We were concerned at the Foreign Office, first with the entry of Turkey into the war, forced upon the Turkish Government as the result of Turkish battleships bombarding the Russians; and next, after the lapse of more than a year, the inevitable declaration from Bulgaria. She had grievances to redress, and it required no more violent change of face to link up with the Turks than it had been to fight with the Serbians.

Mr. Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, recognized the danger of this Turkish alliance, and was all for bringing Turkish resistance to an immediate end. This could be done if the Dardenelles, a narrow passage connecting the Mediterranean with the Black Sea, were forced. The Straits were, however, protected by forts sited on the peninsula of Gallipoli; and owing to the lack of agreement between the military and the naval authorities, and partly due to the reluctance of Lord Kitchener to release the divisions necessary to co-operate, the landing which might have been effective on the Gallipoli Peninsula in conjunction with the Fleet, was not attempted until months afterwards, when, although our gallant troops, reinforced by Australians, secured a foothold on the land at an enormous cost of life, they were unable to carry the strong positions which the Turks held, and the Straits, heavily mined and impassable, remained closed until the end of the war.

The conception was admittedly a great one, and had it been well timed, the attempt to reach Constantinople by sea could not have failed.

The Russians had succeeded in reaching Warsaw, but had been checked. For all her enormous manpower, Russia was not able to afford the aid so desirable. She was ill equipped, and whilst her troops were of the bravest, her munitions were unfortunately quite inadequate to enable her to assist us.

In the meantime, the position in France was becoming, as we called it, stabilized. A definite defence line extended from the North Sea, a little west of Nieuport, to the very frontiers of Switzerland. The French, at the outset of the war, had misguidedly marched into Alsace, and, after a preliminary victory, had been badly defeated and forced to retire to the Voages. That, then, was the position at the beginning of 1915—a state of stalemate, unrelieved by any great success on either side. The German fleet lay under its guns at Wilhelmshaven, whilst the real naval losses had been ours, for a number of our cruisers had been torpedoed by German submarines.

The main fleet lay at Scapa Flow, a roadstead exposed to attack; and it was an anxious time for us all, and especially for those at the Admiralty. At the outbreak of war Lord Louis Mountbatten, a very brilliant sailor, had resigned as the result of some ill-founded criticism of his German origin, and his place had been taken at the Admiralty by Admiral Fisher, a brilliant but elderly man; whilst Admiral Jellicoe had replaced Sir George Callaghan as Commander-in-Chief of the Battle Fleet.

One result of the Navy's vigil was to blockade Germany from the sea, so that her direct supplies were cut off from her, and she had recourse to smuggling such necessities as fats, copper and rubber through the neutral countries.

In those dreary days my chief relief were the letters from Harry, some of which Lorrain sent on to me, and some of which came direct. He had been promoted captain at the Battle of the Aisne, and, by a miracle which would have been unbelievable in the days before the war, was now commanding a battalion in the battle line.

"I'd like you to picture a dreary stretch of land, very flat and very featureless, the drab country being intersected by a number of bad roads, the crowns of which are paved with cobblestones; a light railway or two, across which a conveyance which is half tram-car and half railway train, plies a leisurely service. Something like Holland, with great windmills, innumerable waterways, canals, and little rivers—a squalid, sordid, uncomfortable country, dotted here and there with the headgear of coal-mines. You cannot get an idea at home of what the fighting is like. Picture this countryside, more undulating than usual, a hill covered with woods, a dim and blue background of trees; farmhouses dotted here and there; telegraph poles that stalk across the middle distance; a dilapidated railway with its rails twisted and wrecked and culverts shattered by dynamite; a row of humble cottages, where the peasants have been living, which is now a sandbagged fort, hastily painted a dull grey streaked with green by the engineers. Nothing else visible on the face of the earth; no sound of life or human beings, of soldier or transport or horse. And yet, hereabouts, are some fifty thousand men, and under camouflage—that is a new word which is becoming popular—and covers are guns and rifle pits. Suddenly, with only the warning of a furious cannonading, out of the earth spring a myriad grey coats...Watch them rush across the fire zone, dropping here and there, until only a handful reach the advance infantry trenches...Picture a wild and seemingly disordered scramble of khaki over the top, the flash and thud of bayonets, and the roaring yell as the infantry charge...We have left behind us the open character of the fighting of our earlier battlefields, and are now engaged, under conditions which are abominable. As we march up to our billets the landscape seems to be made up entirely of dead horses, cows and pigs which have been caught in the hail of shrapnel...We pass on our left a row of German dead laid out ready for burial in the graves which the peasants are digging."

I have said that the German was incapable of understanding our psychology, and no better proof of this can be adduced than the air-raids which terrified but did not frighten, if that subtle difference can be realized, the British people. After the first raid by Zeppelins, Whitehall was blocked with men rushing to the recruiters. For the first time, the war had been brought home to them, and they answered in no uncertain voice. Nevertheless, although hundreds of thousands flocked to the standard voluntarily, and Lord Derby in Lancashire alone raised, not battalions, but divisions, it was clear that the tax upon our man-strength was too severe to be met by voluntary recruitment. More serious was our own lack of ammunition. A new ministry had been created: the Ministry of Munitions, to which Mr. Lloyd George applied that fiery energy which has distinguished him in all his public life. Factories were converted; new factories were built—one at Chilwell, by Lord Chetwynd, was perhaps the most important of all; and a new ministry was formed, Mr. Asquith resigning as Prime Minister, and Mr. Lloyd George taking his place.

As I see the war in some sort of proportion, and seek to establish its values, particularly in regard to its conduct by the great political leaders of our time, especially Mr. Asquith and Mr. Lloyd George, I would use the illustration of a relay race, where one carried the baton across rough, uncharted country, handing it to his companion, who carried it to the goal along a much smoother road.

Oh, the delirium of those years! Italy's entry into the war, and her great advance against the Austrian line; Roumania's entry and martyrdom; and then the supreme crisis the revolution in Russia; the arrest, and subsequently the murder, of Czar Nicholas, and the arising of a new force: Bolshevism. Bolshevism we shall never understand until we realize that it was the attempt of an essentially eastern people to put into concrete form the idealism of a Western theorist.

One night we had a very heavy air-raid, and I had been kept up till about two in the morning, and was about to go to bed when the door-bell rang and my valet told me that Miss Avon wished to see me. At the first glance of her white face I knew that something dreadful had happened.

"Stanley has been killed," she said. "It was rather splendid: he led an attack upon a German machine-gun post, and Harry tells me he has been recommended for the Victoria Cross."

"Was Harry there?"

She nodded.

"We had a telegram from him to-night. We ought to have had it earlier, but the raid held up the delivery of messages."

She was very brave and calm about it all, but the effect upon my poor brother was deplorable, and I thought at first the shock would kill him. Afterwards we learned that Harry's battalion had been fighting side by side with the Coldstream Guards. The Guards had been put in, as they always were, to recover a position which seemed irretrievably lost.

We had no time for private griefs, however. The great German attack began in March, 1918, and it seemed that nothing could save us from annihilation, when the 5th Army had gone, and the German troops were pouring into what looked to be a gap that would separate the French from the British. Sir Douglas Haig, who had replaced Sir John French as Commander-in-Chief, sent the gravest news about our position. At such a moment, when the troops were depressed and whole divisions were in a state of confusion, the King went out to France, rode and walked amongst the exhausted soldiers, and by his very presence heartened them...A few months later began the great counter-attack which ended in the destruction of the German resistance, the abdication of the German Emperor and his flight into Holland, in which he was accompanied by his son, the Crown Prince. The Armistice was signed on November 11th, 1918.

THE war is very near to us, so near that it is impossible to gauge accurately the strength of our victory and the consequence of the German defeat. What we were to see was the old reaction which had followed the Napoleonic wars: the closing down of factories, the rapid increase of unemployment, partly caused through the taxations which, though they fell upon the monied classes in the shape of employers and leaders of industry, were to react almost disastrously against the working man. For if industries are taxed, less money is available for the extension of trade. A great corporation earning a profit of £100,000, which has to pay £40,000 in taxes, has that much less to employ in the extension of its business, the building of new factories, and the opening up of new markets.

I have omitted, in my brief summary of the war, reference to one of the most important incidents, and one which finally decided the fate of Europe—namely, the coming of America into the war and the transportation to Europe of an enormous force, which, though it arrived too late to make its weight felt, was the moral decisive factor. For the presence of these troops, a large number of whom were untrained to the actual hardships of campaigning, enabled Marshal Foch, who was the generalissimo of all the Western forces, to release his jealously held reserves whilst American divisions fought most gallantly in the Argonne side by side with the British, before that line of defence which was named after General von Hindenburg, who eventually commanded the German forces.

America had not only helped us with her enormous army and her limitless manhood reserves, but had loaned us huge sums of money, which had been borrowed from her people. And here I would say that there seems to have been at this time an impression that America had an immense national reserve of gold and wealth which she could lend her allies, and the loss of which, even if it were not repaid, could hardly affect her prosperity. This, of course, was a stupid error, for every penny that was loaned to Europe was borrowed from the little investors of the United States and had to be repaid to them. Moreover, the people of the United States gave us an extraordinary exhibition of altruism, for when the German submarines began their unprecedented attack upon British shipping, and the foodstocks of Great Britain became attenuated, the American people voluntarily rationed themselves and suffered deprivations, both in food and in coal, that we might not be defeated by hunger.

The war left Europe with many problems to solve. By the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, France recovered Alsace and a portion of Lorraine, although Alsace at any rate had been a purely German province until it had been taken from them two hundred years before.

The signing of the Peace Treaty did not end the fears of France. She was haunted by the fear that a great country numbering seventy millions of people would rapidly recuperate and in a short space of time would constitute a new menace against her security. The first object of the French, therefore, was not only to disarm the German but to make him incapable of recovering.

We had established ourselves along the Rhine: the British at Cologne, the French and Americans farther south; but this arrangement did not altogether fulfil the desires of the French politicians, the leader of whom was M. Poincare. He aimed at the occupation of the Ruhr, with its immense mineral wealth and its industrial machinery, and, seizing the opportunity which the failure of the German to deliver certain supplies, in accordance with the Treaty, afforded, he sent forward French troops to seize the towns, and there was organized in France a separatist movement, the ostensible leaders of which were Germans.

"The idea being," said Harry (we were sitting on the lawn of his club at Henley, watching the gay pageant of the regatta) "to create an independent buffer state between Germany proper and France. They think in Paris that the Rhinelanders are ready to proclaim an independent republic of their own."

"And are they?" I asked, well knowing what the answer would be.

He smiled.

"I should say not!" he said. "The Germans of the Rhine are bitterly opposed to the separatist movement, and although these rascals who are the so-called leaders of the separatists are working under the protection and with the approval of French troops, they are foredoomed to failure."

It is no secret, I might remark in parentheses, that the British Foreign Office did not see eye to eye with the French Government in this agitation for a separate buffer state, and that the advance of the French into the Ruhr was bitterly resented in this country, and, partly because of the moral pressure exercised by the British Government, the French troops were withdrawn.

"What is the feeling in Germany?"

"It is very sour against France," said Harry, "and I think they have some justification. The French have sent their coloured troops to occupy German towns, and the behaviour of some of these men is insolent in the extreme. In the British area, British and Germans are working together in harmony; and although, naturally, the Germans resent having their conquerors quartered upon them and being under the domination of a foreign power, our people are very well liked."

Germany was of course, now a republic. The Kaiser had abdicated before the signing of the Armistice and retired to Holland with his son, the Crown Prince (who was afterwards allowed by the German Government to return to his estate in Silesia). An attempt made by friends of Russia to establish a similar form of government to that which obtained in Moscow, had been ruthlessly suppressed. The leaders of the communistic party had been shot out of hand, men and women alike. Germany, in spite of its poverty and the extraordinary ravages which war had made upon its manhood, enjoyed a stable government which was ostensibly Republican, but which, Harry insisted, was largely Monarchist.

"And it will never be anything else," he said definitely. "They have the king habit; and although the Republican flag flies over the Government buildings, it is the old Monarchist flag that is carried in processions without interference. Sooner or later Germany will revert to something like its old system of government. But the new Kaiser will be a constitutional monarch, and possibly the control of the army will remain in the hands of the Reichstag."

"That will mean war," said I, but he shook his head.

"Britain is the key which opens the door of havoc," said he, to my surprise. "If anything like a working arrangement can be reached between Germany and England, war is impossible. Does it not strike you that war would have been equally impossible if Britain had been more closely in touch with Berlin in August, 1914? It was because the Germans regarded us as potential enemies that they put all their fortunes to the test of war.

"I am very fond of the French," he went on. "The world owes them a debt which we can never repay. But the French are a truly warrior people, and their history is that war has been the solution of all their problems since the days of the Roman invasion. You have to look at these things fairly and squarely, Uncle John, and honestly. We have to think, not for ourselves, but for the unborn generations who will come, who will be influenced by the truth or the falsehood of the records we leave behind us. We cannot jeopardize the future of our race by the mistaken sentiment of the moment.

"There were only two things to do with Germany after the war," he continued. "One was to mobilize every American, Briton, Frenchman and Italian, walk into the country and destroy every man, woman and child. The other was to regard them as part of a great European family and try to live with them. Of course they will recover—you can't prevent that—and they will again become a great military factor—that is also beyond our power to avert. Recognize the fact squarely, and sit down and puzzle out a way by which wars may be prevented, and unity established. It isn't the act of a foolish or a wicked statesman, a stupid or an ambitious king, which makes war in these days; it is the sentiment, deep-seated in the national heart; it is the trend of opinion generally held. The amour propre of a nation is a much more important factor than any international incident upon which the war-makers seize as an excuse for arming. We came into the war to save Belgium and in honour of our obligations—that is true, though the German could not possibly have fought if he had not come through Belgium. But what really brought us into the war was an anti-Germanism provoked by the Emperor William's precipitate cablegram to President Kruger."

I protested at this.

"Think it over," said Harry. "Go back in your own mind and watch how this resentment against the Germans grew and grew out of those five unnecessary lines of writing. Remember, all wars are fought by little boys at school, who have grown up a few years, but still carry in their minds subconsciously the impressions they have received at their most receptive age. You cannot teach children that wars are unnecessary, because they spend four or five years of their lives learning the beneficent effects of war. But you can teach them that they are the kings who throw down the gauntlet, and the kings who pick it up. You can teach them that war, without strong national prejudice, is an impossibility, and that that prejudice is very often based on a clever lie put into circulation, innocently or mischievously, by men who, having loosed the arrow, have no conception as to where it will fall or what misery will result."

I saw my brother that week-end, and obviously Harry had been to him, for I noticed an extraordinary change of viewpoint, and when he spoke it might have been with Harry's voice.

"I think," he said, "that he is the greatest Avon of all, because he is born soldier and a natural commander of men. He has the intelligence to look back for first causes. I feel bitter about the Germans, naturally," he said in a sad voice, and, remembering poor Stanley lying in a soldier's grave at Bapaume, I was silent. "And I suppose hundreds of thousands of other fathers feel as I. But a new race will be springing up, a new people will populate the earth, and it would be a sin and a shame to pass to them the virus and poison of our animosities."

A few weeks afterwards Harry refused the offer of a safe seat in Parliament. He said he had no desire to go into Parliament, though he spoke very respectfully of our legislators.

He told me a story about the King, which I feel must be placed on record. A great Eastern potentate who spends a great deal of his time in England, has a wonderful diamond worth £300,000, and it was suggested to him that the nation should buy this treasure and present it to the King, to be part of his Crown jewels. The Indian offered to contribute £100,000 of the subscription price, but first interviewed His Majesty to discover whether the project was to his liking. The King's answer was courteous but short.

"Whilst there are over a million unemployed people in this country, do not come to me with any scheme for buying diamonds," he said.

The situation in Britain after the war was rendered the graver by the continuance of a wartime measure—the dole. I talked with Harry about this system, and he pointed out to me that the dole was by no means a novelty.