Educated Evans, Webster's Publications, London, 1924

INSPECTOR PINE was something more than an Inspector of Police. He was what is known in certain circles as a Christian man. He was a lay preacher, a temperance orator, a social reformer. And if any man had worked hard to bring Educated Evans to a sense of his errors, that man was Inspector Pine. He had wrestled with the devil in Mr. Evans' spiritual make-up, he had prayed for Mr. Evans, and once, when things were going very badly, he had induced Mr. Evans to attend what was described as "a meeting of song and praise."

Educated Evans respected the sincerity of one whom he regarded as his natural enemy, but discovering, as he did, that a "meeting of praise and song" brought him no financial advancement, he declined any further invitations and devoted his energies and excursions to picking up information about a certain horse that was running in a steeplechase at Kempton Park on Boxing Day.

Nevertheless, Inspector Pine did not despair. He believed in restoring a man's self-respect and in re-establishing his confidence; but here he might have saved himself a lot of trouble, for the self-respect of Educated Evans was enormous, and he was never so confident as when, after joining in a hymn, two lines of which ran:

The powers of darkness put to flight,

The day's dawn triumphs over night,

he accepted the omen and sent out to all his punters "Daydawn—inspired information—help yourself." For, amongst other occupations, Educated Evans was a tipster, and had a clientèle that included many publicans and the personnel of the Midland Railway Goods Yard.

One day in April, Educated Evans leant moodily over the broad parapet and examined the river with a vague interest. His melancholy face wore an expression of pain and disappointment, his under-lip was out-thrust in a pout, his round eyes stared with a certain urgent agony, as though he had given them the last chance of seeing what he wanted to see, and if they failed him now they would never again serve him.

So intent was he that one who, although a worker in another and, to Evans, a hateful sphere, bore many affectionate nicknames, was able to come alongside of him and share his contemplation without the sad man observing the fact.

Fussing little tugs, lethargic strings of barges, a police-boat slick and fast—all these came under the purview of Educated Evans, but apparently he saw nothing of what he wanted to see, and drew back with an impatient sigh.

Then it was that he saw his companion and realised that here, on the drab Embankment, was one whom he had imagined to be many miles away.

The new-comer was a tall man of thirty, broad-shouldered, power in every line of him. He was dressed in black, and a broad-rimmed felt hat was pulled over his eyes. He was chewing a straw, and even if Mr. Evans had failed to identify him by another means, he would have known "The Miller"—whose other name was William Arbuthnot Challoner —by this sign.

"Why, 'Miller,' I thought you was dead! And here was I speculatin' upon the one hundred and ninety million cubic yards of water that passes under that bridge every day, and meditatin' upon the remarkable changes that have happened since dear old Christopher Columbus sailed from that very pier, him and the Pilgrim Fathers that discovered America in Fifteen Seven Nine—"

"The Miller" listened and yet did not listen. The straw twirled between his strong teeth; his long, saturnine face was turned to the river; his thoughts were far away.

"A lovely scene," said Mr. Evans ecstatically, indicating the smoky skyline; "the same as dear old Turner used to paint, and Fluter—"

"Whistler," said his companion absently

"Whistler, of course—dear me, where's my education!" Mr. Evans rolled his head in self-impatience. "Whistler. What a artist. 'Miller'—if you'll excuse the familiarity. I'll call you Challoner if you're in any way offended. What—a—artist! There is a bit of painting of his in the National Gall'ry. And another one in the—the Praydo in Madrid. Art's a perfect weakness with me—always has been since a boy. Do you know Sergeant? Great American painter. One of the greatest artists in the world. An' do you know the celebrated French artist, Carrot?

"Do you know," began "The Miller," speaking deliberately, and looking at the river all the time, "do you know where you were between 7.30 p.m. and 9.15 p.m. on the night of the eighth of this month?"

"I do," said Educated Evans promptly.

"Does anybody else know—anybody whose word would be accepted by a police magistrate gifted with imagination and a profound distrust of the criminal classes?"

"My friend, Mr. Harry Sefferal," began Evans, and "The Miller" laughed hollowly and with an appearance of pain.

"You have only to put your friend in the witness-box," he said, "you have only to let the magistrate see his sinister countenance to be instantly remitted to Dartmoor for the remainder of your life. Harry Sefferal could only save you from imprisonment if you happened to be charged with murder. Reading his evidence, the hangman would pack his bag without waiting for the verdict. Harry Sefferal!"

Mr. Evans shrugged.

"On the evening in question it so happened that I was playing a quiet game of solo in the company of a well-known and respected tradesman, Mr. Julius Levy—"

"You're a dead man!" groaned "Miller." "Julius Levy is the man who put the "u" into 'guilty.' Know Karbolt Manor?"

Mr. Evans considered.

"I can't say that I do," he said at last.

"Near Sevenoaks—the big house that Binny Lester burgled five years ago and got away with it."

Educated Evans nodded.

"Now that you mention the baronial 'all, 'Miller,' it flashes across my mind—like a dream, as it were, or a memory of happier days."

"Is there a ladder in your dream? A ladder put up to Lady Cadrington's bedroom window when the family was at dinner? Dream carefully, Evans."

Mr. Evans wrinkled a forehead usually smooth and unlined.

"No," he said; "I know the place, but I haven't been near there. I can take the most sacred oath—"

"Don't," begged "The Miller." "I would rather have your word of honour. It means more."

"On my word of honour as a gentleman," said Evans solemnly, "I have not been to, frequented, been in the vicinity of, or otherwise approached this here manor. And if I am not telling the truth may Heaven smite me to the earth this very minute!"

He struck an attitude, and "The Miller" waited, looking up at the skies.

"Heaven didn't hear you," he said, and took the arm of Evans. "Pine wants to see you."

Educated Evans shrugged his resignation.

"You are taking an innocent man," he said with dignity. "The Miller" bore the blow bravely.

"The Miller" was always "The Miller" to a certain class. He was taxed in the style and title of Detective-Sergeant W. Arbuthnot Challoner, Criminal Investigation Department. He was an authority upon ladder larceny, safe-blowing, murder, gangery, artfulness and horses. Round Camden Town, where many of his most ardent admirers had their dwelling-places, he was called "The Miller" because of this queer straw-nibbling practice of his.

He was respected; he was not liked, not even by Educated Evans, that large-minded and tolerant man. Evans was both liked and respected. In North London, as distinct from South London, erudition has a value. Men less favoured look up to those proficient in the gentle art of learning. Educated Evans was one of whom the most violent and the least amiable spoke with respect.

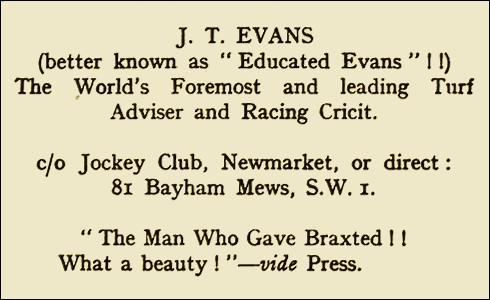

Apart from his erudition (he had written more speeches for the defence than any other amateur lawyer), he was undoubtedly in the confidence of owners, trainers, jockeys and head lads. He admitted it. He was the man who gave Braxted for the Steward's Cup and Eton Boy for the Royal Hunt Cup. There are men holding affluent positions in Camden Town who might trace their prosperity to the advice of Educated Evans. It was said, by the jealous and the evil-minded, that St. Pancras Workhouse has never been so full as it was after that educated man had had a bad season.

"It was a matter for regret to me," said Evans as he shuffled along by his captor's side, "that the law, invented by Moses and Lord What's-his-name, should be employed to crush, so to speak, the weak. And on the eve, as it were, of the Newbury Spring Handicap, when I did hope to pack a parcel over Solway."

"The Miller" stopped and surveyed his prisoner with curiosity and disapproval.

"Solway," he said deliberately, "is not on the map. St. Albyn could give Solway two stone and lose him"

The lip of Educated Evans curled in a sneer

"Solway could fall dead and get up and then win," he said extravagantly. "St Albyn ain't a horse, he's a hair trunk. The man who backs St. Albyn—"

"I've backed St. Albyn," said "The Miller" coldly. "I've had it from the owner's cousin, who is Lord Herprest, that, barring accidents, St. Albyn is a stone certainty."

Educated Evans laughed; it was the laugh of a man who watches his enemy perish.

"And they hung poor old Crippen," he said.

There was this bond of sympathy between "The Miller" and his lawful prey—that they were passionate devotees of the sport of kings. When "The Miller" was not engaged in the pursuit of social pests (among whom he awarded Educated Evans very nearly top weight) he was as earnestly pursuing his studies into the vagarious running of the thoroughbred racehorse.

"What about Blue Chuck?" he asked. "There's been a sort of tip about for him."

Evans pulled at his long nose.

"That's one that might do it," he admitted. "Canfyn's told his pals that it won't be ready till Goodwood, but that feller would shop his own doctor. I wouldn't believe Canfyn if he was standin' on the scaffold and took an oath on Foxe's Book of Martyrs."

Passers-by, seeing them, the shabby man in the long and untidy coat and the tall man in black, would never have dreamt that they were overlooking a respected officer of Scotland Yard and his proper prey.

"What makes you think that St. Albyn hasn't a chance, Evans?" asked "The Miller" anxiously.

"Because he ain't trying," said Evans with emphasis. "I've got it straight from the boy who does him. He's not having a go till Ascot, an' they think they can get him in the Hunt Cup with seven-five."

"The Miller" blew heavily. That very morning Teddie Isaacheim, a street bookmaker who possessed great wealth and singular immunity from police interference, had laid him fifty pounds to five and a half (ready) about this same St. Albyn. And five and a half pounds was a lot of money to lose.

"If you'd asked me I'd have told you," said Educated Evans gently. "If you'd come to me as man to man an' as a sportsman to a sportsman, instead of all this ridiculous an' childish nonsense about me actin' in a thievous and illegal manner, I'd have give you the strength of St. Albyn. And I'd have put you on to the winner of the one o'clock race to-morrow—saved specially... not a yard at Kempton.... not busy at Birmingham—havin' a look on at Manchester, but loose to-morrer!"

"What's that, Evans?"

"The Miller's" voice was mild, seductive, but Evans shook his head, and they marched on.

"Never," said the educated man with great bitterness, "never since old Cardinald Wolseley was pinched for giving lip to King Charles has a man been more disgustin'ly arrested than me. If I don't get ten thousand out of the police for false imprisonment... if I don't show up old Pine for this—"

"Is it Clarok Lass, old man?" asked "Miller," as they came in sight of the police station.

"No, it ain't Clarok Lass," said Evans savagely. "And if you think you're going to get my five pound special for a ha'porth of soft soap, you've got another guess coming. I'm finished with you, 'Miller,' I am. Didn't I give you King Solomon an' Flake at Ascot last year? Didn't I run all over the town to put you on to that good thing of Jordan's?"

"You've certainly done your best, Evans," agreed his captor soothingly, "and if I can put in a word for you—what did you say was going to win that one o'clock race?"

Educated Evans pressed his lips tightly, and a few seconds later "The Miller" was his business-like self.

"Here is Evans, sir; he says he knows nothing of the Sevenoaks job, and he can produce two witnesses to swear that he was in town at the time of the robbery. Maybe he can produce forty-two—"

Inspector Pine came in whilst Evans was being searched by the gaoler, and shook his head grievously.

"Oh, Evans, Evans! " he sighed. "And you promised me faithfully that you'd never come again!"

Educated Evans sniffed.

"If you think I came here on my own, sir, you're wrong."

Again the white-haired inspector shook his head.

"There's good in every human heart," he said. "I will not lose hope in you, Evans. What is the charge?"

"No charge, sir, detention. We want him in connection with the Sevenoaks affair, but there are a few alibis to be tested," said "The Miller."

So they put Educated Evans into No. 7, which was his favourite cell, and Evans wondered what horse in the Newbury Cup was numbered 7 on the card.

That night certain heated words passed between the Honourable George Canfyn and the usually amiable attendants at the Hippoleum Theatre. George, who had dined, retaliated violently.

George Canfyn was a man of property and substance, an owner of racehorses and a gentleman by law. His father was Lord Llanwattock. His other name was Snook, and he made candles in a very large way. And in addition to candles he made margarine, money and political friends. They in turn made him a Baron of the United Kingdom. The law made him a gentleman. God was not even consulted.

George was the type of man who liked money for money's sake. Most people tell you that money means nothing to them, only the things you can buy with it. George liked money plain. He wanted all the money there was, and it hurt him to see the extraordinary amount that had failed to come his way. He lived cheaply, he ate meanly, and he changed his trainer every year.

If a horse of his failed to win when he had his packet down, he did everything except complain to the Stewards. He never had the same jockey more than three times, because he believed that jockeys cut up races and arranged the winner to suit their own pockets. He believed all trainers were incompetent, and all the jockeys who weren't riding his horse to be engaged in a conspiracy to "take care" of it.

When he won (as he did very often) he told his friends before the race that his horse just had a chance, and advised them not to bet heavily. George hated to see the price come down, because he invariably had his bets with the S.P. offices. And when it won, he appeared surprised, and told everybody how he nearly had a fiver on, but thinking the matter over in a quiet place, he decided that, with the income tax what it was, it was criminal to waste money. And some people believed him.

George was in a fairly happy state of mind when he went out to the Hippoleum, for that morning he had come up from Wiltshire after witnessing the trial of Blue Chuck, his Newbury Cup horse. Blue Chuck had slammed the horses in the trial and had won on a tight rein by many lengths. And not a single writing person had tipped Blue Chuck. It was certain to start amongst the "100-6 others," and George was already practising the appearance of amazement which he would display when he faced his acquaintances.

In the cheerful contemplation of Wednesday Mr. Canfyn sallied forth, his complacency fortified by three old brandies, which had cost him nothing, a sample bottle having been sent to him by a misguided wine merchant. And then came the disaster.

Three policemen brought him into Hallam Street Station, and here the matter might have been satisfactorily arranged if the third of the three old brandies had not started to put in some fine work.

"I'll have your coats off your backs for this, you scoundrels!" he screamed, as they searched him scientifically. "I'm the Honourable George Canfyn, the son of Lord Llanwattock—"

"What's the charge?" asked the weary station-sergeant, who was not unused to such scenes of agitation.

"Drunk and disorderly and assault," said the policeman who had brought in this scion of nobility.

"I'm not drunk!" roared George.

"Don't take those things away from me, they're my private papers! And count that money—if there's a penny missing, have you kicked out of the police force—"

"Number 8," said the man on the desk, and they led George below.

"Oh, that a man should put an enemy into his mouth to steal away his brains," murmured the inspector, standing in the open doorway of his room. "Drink is a terrible thing, sergeant!"

"Yes, sir," said the sergeant, and looked up at the clock. It was perilously near ten.

The inspector went back to his room with a sigh. The big table was covered with cards and addressed envelopes, and the inspector was an elderly man and very tired. He looked for a long time at the accumulation of work that had to be finished before the midnight post went out.

Inspector Pine was, amongst other things, Secretary of the Racecourse Elevation Brotherhood for the Suppression of Gambling. And the cards were to announce a special meeting of the Brotherhood to consider next year's programme. And, as yet, not one of the thousand cards had been stamped with the announcement that, owing to a regrettable prior engagement, the Bishop of Chelsea would not be able to attend.

He was so contemplating the unfinished work when there was a tap at his door and "The Miller came in.

"A miracle has happened, sir," he said. "I've found three decent people who can swear that Evans was practically under their eyes when the larceny was committed. Mr. Isaacheim, the well-known and highly-respected commission agent—"

"A bookmaker," murmured Inspector Pine, reproachfully.

"Still, he's a taxpayer and a ratepayer," said "The Miller" loyally. "And though to me gambling is a form of criminal lunacy, we must take his word. And Mr. Corgan, of the 'Blue Hart'—"

"A publican," said old man Pine in distress.

"And a sinner. But he's a well-known town councillor. Can I tell the gaoler to let Evans go?"

Inspector Pine nodded, and his eyes returned to the unfinished work.

"You don't know anybody who could help me to put these cards into envelopes, I suppose, sergeant?"

It was an S.O.S.: an appeal directed to "The Miller" himself.

"No, sir," replied Miller promptly; and then, as a thought occurred to him: "Why don't you ask Evans? He's a man of education, and he'd be glad to stop for a few hours."

Educated Evans had spent a sleepless five hours in a large and sanitary cell, meditating alternately upon man's injustice to man and the depleted state of his exchequer. For his possessions consisted of twelve-and-sixpence put by for a railway ticket to Newbury, and the price of admission. For purposes of investment he had not so much as a tosser. It was the beginning of the season, and his clientèle had been dissipated by the mistaken efforts on his part to carry on business through the winter. It would take him to the Jubilee meeting before he could re-establish their confidence.

He heard the sound of an angry voice, and, peering through the ventilator of the cell, saw and recognised the Honourable George Canfyn being led to confinement. When the gaoler had gone:

"Excuse me, Mr. Canfyn," said Educated Evans, in a hoarse whisper, his mouth to the ventilator. He was all a-twitter with excitement.

"What do you want?" growled the voice of the Honourable George from the next cell.

"I'm Johnny Evans, sir, better known as Educated Evans, the well-known Turf Adviser. What about your horse, Blue Chuck, for to-morrow?"

"Go to hell!" boomed the voice of his fellow-prisoner.

"I can do you a bit of good," urged Evans. "I've got a stone pinch—"

"Go to blazes, you—"

In his annoyance he described Educated Evans libellously.

Educated Evans was meditating upon the strangeness of fate that had brought the son of a millionaire into No. 8, when the lock of his cell snapped back.

"You can go, Evans," said "The Miller" genially. "I've gone to no end of trouble to get you out—as I said I would. What's that horse in the one o'clock?"

"Clarok Lass," said Evans and "The Miller" swore softly.

"If I'd known that, I'd have left you to die," he said. "You said it wasn't Clarok Lass—here, come on, the inspector's got a job for you."

Wonderingly, Educated Evans followed the detective to the inspector's room, and in a few gentle words the nature of the job was explained.

"I will give you five shillings out of my own pocket, Evans," said Inspector Pine, "and at the same time I feel that I am perhaps an instrument to bring you to the light."

Educated Evans surveyed the table with a professional eye. He was not unused to the task of filling envelopes, for there was a time when he had a thousand clients on his books.

"Miller," glad to escape, left them as soon as he could find an excuse, and the inspector proceeded to enlighten his helper in the use of the stamp.

"When the stencil is worn out you can write another. Fix it over the inking pad so, and go ahead."

It was a curious stamp, one unlike any that Evans had ever used. It consisted of an oblong stencil paper, fixed in a stiff paper frame and a metal ink-holder. The inspector showed him how the stencil was written with a sharp-pointed stylus on a stiff board, how it had to be damped before and blotted after, and Evans, who had never stopped learning, watched.

"It will be something for you to reflect upon that every one of these dear people is an opponent to the pernicious sport of horse-racing. For once in your life, Evans, you are doing something to crush the hydra-headed monster of gambling."

"Where's that five shillings, sir?" said Evans, and the officer parted.

He was on the point of leaving Evans to his task when the station-sergeant came in.

"Here's the money and papers of that drunk, sir," he said, and deposited a small package on the desk. "Perhaps you'd better put them in the safe. He's sent for his solicitor, so he'll probably be bailed out. But he made such a fuss about his being robbed that it might be better to keep them until he comes before the magistrate in a sober mind."

Mr. Pine nodded and opened the big safe that stood in one corner of the room as the sergeant went out. First he put the money, watch and chain and gold cigarette case in a drawer. Then he took up the little pocket-book and turned the leaves with professional deftness.

"Another gambler," he said sadly.

"Who's that, sir?"

"A man—a gentleman who is unfortunately with us to-night," said Inspector Pine, and paused. "What is a trial, Evans?"

"A trial, sir?"

"It is evidently something to do with horse-racing," said the inspector, and read, half to himself: " 'Blue Chuck 8-7; Golders Green 7-7; Makin 7-0. Won four lengths. Time 1.39.' That has to do with racing, Evans?"

Educated Evans nodded, not trusting himself to speak.

"You have your five shillings, Evans. I will leave you now. Give the letters to the sergeant; he will post them. Goodnight."

From time to time that night the sergeant glanced through the open door of the inspector's room, and apparently Educated Evans was a busy man. At midnight, just as the Hon. George Canfyn's solicitor arrived, he carried his work to the station-sergeant's desk, and after the sergeant had made a quick scrutiny of the private office to see that nothing was missing, Evans was allowed to depart.

At ten o'clock next morning Inspector Pine was shaving when his crony and fellow-labourer in the social field (Mr. Stott, the retired grocer) arrived in great haste. And there was on Mr. Stott's face a look of bewilderment and annoyance.

"Good-morning, Brother Stott," said the inspector. "I got all those cards out last night—at least, I hope I did."

Mr. Stott breathed heavily.

"I got my card, Brother Pine," he said, "and I'd like to know the meaning of it."

He thrust a piece of cardboard into the lathered face of the inspector. There was nothing extraordinary in the card. It was an invitation to a meeting of the Brotherhood for Suppressing Gambling.

"Well?"

"Look on the other side," hissed Mr. Stott.

The inspector turned the card and read the stencilled inscription:

If any Brother wants the winner of the Newbury Handicap,

send T.M.O. for 20s. to the old reliable Educated Evans,

92 Bingham Mews. This is the biggest pinch of the year!

Defeat ignored! Roll up, Brothers! Help yourself,

and make T.M.O. payable to E. Evans.

"Of course, nobody will reply to the foolish and evil man," said the inspector, as he was giving instructions to "The Miller." "Every member of the Brotherhood will treat it with contempt; still, you had better see Evans."

When "The Miller" arrived at 92 Bingham Mews (it was the upper part of a stable) he found that melancholy man opening telegrams at the rate of twenty a minute.

"And more's coming," said Educated Evans. "There's no punter like a Brother."

"What's the name of the horse?" asked "The Miller" in a fever.

"Blue Chuck—help yourself," said Educated Evans. "And don't forget you owe me a pound."

"The Miller" hurried off to interview Mr. Isaacheim, the eminent and respectable Turf accountant.

MR. HOMASTER'S daughter was undoubtedly the belle of Camden Town, and when she retired from public life, there is less doubt that Mr. Homaster's trade suffered in consequence.

But as Mr. Homaster very rightly said that even the saloon bar was no place for a young lady, and although, as a result of her withdrawal, many clients who had with difficulty sustained themselves at saloon prices returned in a body to the public portion of the "Rose and Hart," where beer is the stable of commerce, Mr. Homaster (he was Hochmeister until the war came along) bore his loss with philosophy, and his reputation, both as a gentleman and a father, stood higher than ever.

Miss Belle Homaster was the most beautiful woman that Educated Evans had ever seen. She was tall, with golden hair and blue eyes, and a fine figure. Across her black, tightly-fitting and well-occupied blouse she invariably wore the word "Baby" in diamonds, that being her pet name to her father and her closer relatives.

Evans used to go into the saloon bar every night for the happiness of seeing her smile, as she raised her delicately pencilled eyebrows at him. She never asked unnecessary questions. A lift of those arched brows, a gracious nod from Evans, the up-ending of a bottle, a gurgle of soda water, and Evans laid a half-crown on the counter and received the change with a genteel "Thenks."

Sometimes she said it was a very nice day for this time of year. Sometimes, when it wasn't a very nice day, she asked, with a note of gentle despair: "What else can you expect?"

It was generally understood that Evans was her favourite. Certainly he alone of all customers was the recipient of her confidences. It was to Evans that she confessed her partiality for asparagus, and it was Evans who heard from her own lips that she had once, as a small girl, travelled in the same 'bus as Crippen.

A friend of his, at his earnest request, spoke about him glowingly, told her of his education and his ability to settle bets on the most obtuse questions without reference to a book. The way thus prepared by his friendly barker, Evans seized the first opportunity of producing samples of his deep knowledge and learning.

"It's curious, miss, me and you standing here, with the world revolving on its own axle once in twenty-four hours, thereby causing day and night. Few of us realise, so to speak, the myst'ries of nature, such as the moon and the stars, which are other worlds like ours. They say there's life on Mars owing to the canals which have been observed by telescopic observation. Which brings us to the question: Is Mars inhabited?"

She listened, dazed.

"The evolution of humanity," Evans went on enjoyably, "was invented by Darwin, which brings us to the question of prehistoric days."

"What a lot you know!" said the young lady. "Would you like a little more soda? The weather's very seasonable, isn't it?"

"The seasons are created or caused by the revolutions of the world—"

began

Evans.

But she was called away to tend the needs of an uneducated man who needed a chaser.

Everybody knew Miss Homaster. Even "The Miller." When that light and ornament of the criminal investigation department desired an interview with any of his criminal acquaintances, he was certain of finding them hovering like obese moths about the flame of her charm and beauty.

At eight, or thereabouts, Sergeant William Arbuthnot Challoner would push open the swing doors of the saloon bar and glance carelessly round, nod to such of his old friends as he saw, raise his hat to Miss Homaster and retire.

The news of her engagement was announced two days before she left the bar for good. It was to the unhappy Evans that she made the revelation.

"I'm being married to a gentleman friend of mine," she said, what time Educated Evans clutched the edge of the counter for support. "I believe in marrying young and being true. A wife should be a friend to her husband and help him. She ought to be interested in his business. Don't you agree, Mr. Evans?"

"Yes, miss," said Evans with an effort. "For richer and poorer, in sickness and in woe, ashes to ashes."

"The Miller" learnt of the engagement from Educated Evans.

"I believe in marriage," he said. "It keeps the divorce court busy."

A heartless, cynical man, in whom the wells of human kindness had run dry.

There is a legend that once upon a time "The Miller" had a fortune in his hand, or within reach of that member. "The Miller" never discussed the matter, even with his intimates. Even Educated Evans, who counted himself something more than an ordinary acquaintance, with rare delicacy never referred to that tremendous lost opportunity.

Yet there it was: Fortune, with a row of houses under each arm, had kicked at the door, and "The Miller" had hesitated with his hand on the latch.

Rows of houses, a motor-car, Tatts every day of his life if he so desired, and his ambition moved to such a lofty end—and lost because "The Miller" refused to credit the evidence of his own ears or to accept the dictum of the ancients, in vino veritas.

Mr. Sandy Leman was certainly in vino when "The Miller" pinched him for (1) drunk, (2) creating a disturbance, (3) conduct calculated to bring about a breach of the peace, (4) insulting behaviour. ("He was," to quote the expressive language of Educated Evans, "so soused that he tried to play a coffee stall under the impression it was a grand pianner.") As to the "veritas," was "The Miller" justified in believing that there was only one trier in the Clumberfield Nursery, and that trier Curly Eyes? Mr. Sandy Leman proclaimed the fact to the world on the way to the station, insisted on seeing the divisional surgeon to tell him, and made pathetic inquiries for Mr. Lloyd George's telephone number in order to pass the good news along to one about whom (in moments of extreme intoxication) he was wont to shed bitter tears.

"The Miller" had the market to himself, so to speak, and after much hesitation had five shillings each way. And that, after having decided overnight to take a risk and have fifty to win! Curly Eyes won at 100-6. "The Miller" read the news, cast the paper to the earth and jumped on it. That is the story.

Along the platform of Paddington Station came Educated Evans at a slow and not unstately pace. His head was held proudly, his eyes half-closed, as though the sight of so many common racing people en route for Newbury was more than he dared see, and in his mouth a ragged cigar. Race glasses, massive and imposing, were suspended from one shoulder, an evening newspaper protruded from each of the pockets of his overcoat.

Educated Evans halted before the locked door of an empty first-class carriage and surveyed the approaching guard soberly.

"Member," he said simply.

"Member of Parliament or Member of Tattersall's?" asked the sardonic

guard.

"Press," said Evans, even more gravely. "I'm the editor of The

Times."

The guard made a gesture.

"Where's your ticket?" he asked, and with a sigh Educated Evans produced the brief.

"Third class—and yesterday's," said the guard bitterly. "Love a duck, some of you fellows never lose hope, do you?"

"I shall take your number, my friend," said Evans, stung to speech. "The Railway Act of 1874 specifically specifies that tickets issued under the Act are transferable and interchangeable—"

The guard passed on. Evans saw the door of a corridor car open and the guard's back turned. He stepped in, and, sinking into a corner seat, blotted out his identity with an evening newspaper.

"I always say, sir," said Evans, as the train began to move and it was safe to appear in public, "that to start cheap is to start well. Not that I'm not in a position to pay my way like a gentleman and a sportsman."

His solitary companion was also hidden behind an extended newspaper.

"It stands to reason," Mr. Evans went on, "that a man like myself, who is, so to speak, in the confidence of most of the Berkshire and Wiltshire stables, and have my own co-respondents at Lambourn, Manton, Stockbridge, and cetera, it only stands to reason that, owning my own horses as I do—hum!"

"The Miller" regarded him coldly over the edge of his newspaper.

"Don't let me interrupt you, Evans," he said, politely. "Let me hear about these horses of yours, I beg! Tell-a-Tale, by Swank out of Gullibility, own brother to Jailbird, and a winner of races; Tipster, by Ananias out of Writer's Cramp, by What-Did-I-Give-Yer."

"Don't let us have any unpleasantness, Mr. Miller," said Evans, mildly. "I'm naturally an affable and talkative person, like the famous Cardinal Rishloo, who, bein' took to task by Napoleon for his garolisty, replied 'There's many a good tune played on an old fiddle.' "

"Not satisfied," continued "The Miller," "with defrauding the Great Western Railway by travelling first on a dud third-class ticket, you must endeavour, by misrepresentation of a degrading character, to obtain money by false pretences."

"The Miller" shook his head, and the straw between his teeth twirled ominously.

"What are you backing in the two-thirty?" asked Evans pleasantly. "I've got something that could lay down and go to sleep and then get up and win so far that the judge'd have to paint a new distance board. This thing can't be beat, Mr. Miller. If the jockey was to fall off this here horse would stop, pick him up, and win with him in his mouth! He's that intelligent. I've had it from the boy that does him."

"If he does him as well as you've done me," said "The Miller," "he ought to glitter! I'm doing nothing but your unbeatable gem in the Handicap. Isaacheim wouldn't lay me the money I wanted, so I thought I'd come down. Not that the horse will win."

The melancholy face of Educated Evans twisted in a sneer.

"It will win," he said with calm confidence. "If this horse was left at the post and started running the wrong way he could turn round and then win! I know what I'm talking about. I can't give you the strength of it without, in a manner of speakin', betrayin' a sacred confidence. But this horse will WIN! I've sent it out to three thousand clients—"

"That's a lie," said "The Miller," resuming his perusal of the Sporting Life.

"Well, three hundred—an' not far short."

Mr. Evans fingered the crisp notes in his pocket, and the crackle of them made music beside which the lute of Orpheus would have sounded as cheerful as a church bell on a foggy morning. He had certainly received inspired information. If Blue Chuck was not a certainty for .the Newbury Handicap, then there were no such things as certainties. He had seen the owner's description of the trial in the owner's pocket-book.

All that morning Mr. Evans had been engaged in despatching to his clients—for he was a tipster not without fame in Camden Town—the glorious and profitable news. For an hour he had carried the tidings of great joy to an old and tried clientèle. Some had been so well and truly tried that they publicly insulted him. Others to whom, leaning across the zinc-covered counter of the public bar, he had whispered the hectic intelligence, had drawn a pint, mechanically, and said "Is this another one of your so-and-so dreams?"

Educated Evans had time to catch the 12.38. Mr. Evans could have afforded a first-class ticket, but he held firmly to the faith that there were three states that it was the duty of every citizen to "best." First came the Government; then, in order of merit, came railway companies; thirdly, and at times even firstly, appeared the bookmaking class.

He had secured his ticket from a fellow sojourner at the Rose and Hart. Its owner valued it at two hog. Evans beat him down to eightpence.

"Making money out of Blue Chuck is easier than drawing the dole," said Evans, as I know. Mr. Miller, you understand these things. What would you put eighteen hundred pounds into if you was me?"

"Eh?" said the startled Miller. "You have got eighteen hundred pounds?"

"Not at the moment," admitted Evans modestly. "But that is the amount I'll have when I come back. It's a lot of money to carry about. House property is not what it was," he added, "nor War Loan, after what this Capital Levy is trying to do to us. Who is this feller Levy, Mr. Miller? It's Jewish; but I don't seem to remember the Christian name."

As the train was passing through Reading, Educated Evans delivered himself of a piece of philosophy.

"Bookmakers get fat on what I might term the indecision of the racin' public," he said. "The punter who follows the advice of his Turf adviser blindly and fearlessly is the feller who packs the parcel. But does he follow the advice of his Turf adviser blindly and fearlessly, Mr. Miller? No, he doesn't."

"And he's wise," said "The Miller," without looking up from his paper, "if you happen to be the Turf adviser."

"That may be or may not be," said Educated Evans firmly. "I'm merely telling you what I've learnt from years an' years of experience—and mind you, my recollection goes back to the old Croydon racecourse. It's hearin' things, it's bein' put off, it's bein' told this, that, and the other by nosy busybodies that enables Sir Douglas Stuart—ain't he? well, he ought to be—to spend his declining days on the Rivyera."

"The trouble with you, Evans," said "The Miller," folding his paper as the train slowed for Newbury, "is that you talk too much."

"The trouble with me," said Educated Evans, with dignity, "is that I think too much!"

He parted from the detective on the platform, and was making his way toward the entrance of the Silver Ring when he stopped dead. A lady was crossing the roadway to the pay gate, and the heart of Educated Evans leapt within him. He knew that black fox fur, that expensive velour hat, those high-buttoned boots. For a second the economist and the lover struggled one with the other, and the lover won. Educated Evans followed hot on her trail, wincing with pain as he paid 2s. 6d. and followed the lady to the paddock.

She turned at the sound of her name, and it must be said of Miss Homaster that her attitude toward Evans was not only extremely cordial but amazingly condescending.

"Why, Mr. Evans, whoever expected to see you?" she said. "What extraordinary weather it is for this time of the year!"

"It is indeed, Miss Homaster," said Evans. "Is your respected father with you?"

"No, I've come alone," said Miss Homaster, with a saucy toss of her head, "and I'm going to back all the winners."

Here was the chance that Educated Evans had been praying for, the opportunity which he never dreamt would come.

He had pictured himself rescuing her from burning houses, or diving into the seething waters of the canal and bringing her back to safety, perhaps breathing his last in her arms; but he had never imagined that the opportunity would arise of giving her "the goods."

"Miss Homaster," he said in a hoarse whisper, "I'm going to do you a bit of good. I've got the winner of the Handicap. It's Blue Chuck; he's a stone certainty. He could fall down and get up and then win."

"Really?" She was genuinely interested as he told her the strength of it.

He left her soon after (he knew his place) and strolled into the ring. He had been in Tattersall's once before, but the experience was not as thrilling as it might have been. An acquaintance saw him and came boisterously toward him.

"Hallo, Educated!" he said. "I've got something good for you, old cock; I've got the winner of the Handicap up me sleeve. Bing Boy! "

He looked round to see that he was not overheard, and in his interest he failed to see the cold sneer that was growing on the face of Mr. Evans.

"This horse," said his acquaintance, "has been tried good enough to win the Derby even if it was run over hurdles! This horse could fall down—"

"And I should say he would fall down," said Evans, his exasperation getting the better of his politeness. "You couldn't make me back Bing Boy with bad money. You couldn't make me back it with bookmakers who had twilight sleep and forgot all that happened a few minutes before. Bing Boy!" he said, with withering contempt.

Nevertheless, Bing Boy was favourite, and the horse that Educated Evans had come to back was at any price. Evans was disconcerted, alarmed. He went into the paddock and saw the scowling owner of his great certainty. He did not look happy. Perhaps it was because he had spent the greater part of the previous evening in an uncomfortable police-station cell.

Evans went in search of the man who gave him Bing Boy to get a little further information.

And they were backing Smocker. He was a strong second favourite, and it was difficult to get 7 to 2 about him. A man Evans knew drew him aside to a place where he could not be overheard by the common crowd and told him all about Smocker.

"This horse," he said impressively, as he poked his finger in Evans' waistcoat to emphasise the seriousness of the communication, "has been tried twenty-one pounds better than Glasshouse. He won the trial on a tight rein, and if what I hear is true—and the man that told me is the boy that does him—Smocker could fall down—"

"There'll be a few falls in this race," said Educated Evans hollowly.

The first few events were cleared from the card, and betting started in earnest over the Handicap, and yet Educated Evans delayed his commission. To nearly three hundred clients he had wired, "Blue Chuck. Help yourself. Can't be beaten." And here was Blue Chuck sliding down the market like a pat of butter on the Cresta Run! Tens, a hundred to eight, a hundred to seven in places.

"Phew!" said Educated Evans.

The notes in his pocket were damp from handling. He made another frantic dive into the paddock in the hope of finding somebody who would give him the least word of encouragement about Blue Chuck.

Again he saw the owner of Blue Chuck, scowling like a fiend.

And then somebody spoke to him, and he turned quickly, hat in hand.

"Why, I've been looking everywhere for you, Mr. Evans," said Miss Homaster.

"I've got such a wonderful tip for you. Your horse—Blue Chuck, wasn't it?—isn't fancied in the least bit. The owner told a friend of mine that he didn't expect he'd finish in the first three."

The heart of Educated Evans sank, but it was not with sorrow for his deluded clients.

"Smocker will win." She lowered her voice. "It is a certainty. I've just been offered five to one, and I've backed it."

"Five to one?" said Educated Evans, his trading instincts aroused. "You can't get more than four to one."

"I can," said the girl in triumph. "I'll show you."

Proud to be seen in such delightful company, Educated Evans followed her, through the press of Tattersall's, down the rails, until near the end he saw a tall, florid young man—no less a person than Barney Gibbet!

"Mr. Gibbet, this is a friend of mine who wants to back Smocker. You'll give him five to one?"

Gibbet looked sorrowfully at Educated Evans.

"Five to one, Miss Homaster?" he said, shaking his head. "No, it's above the market price."

"But you promised me," she said reproachfully.

"Very well. How much do you want on it, sir?"

The lips of Educated Evans opened, but he could not pronounce the words. Presently they came.

"Three hundred," he said in broken tones.

"Ready?" asked Mr. Gibbet, with pardonable suspicion.

"Ready," said Educated Evans.

It proved, on examination, that he only had £240. He had conjured up the other £60, for he was ever an optimist. In the end he was laid £1,100 to £220.

"You won't mind if I give you a cheque for your winnings?" asked Mr. Gibbet. "I don't carry a large sum of money round with me; it's not quite safe amongst these disreputable characters you meet upon racecourses."

"I quite agree," said Educated Evans heartily, and went up to the stand to see the race.

It was a race that can easily be described, calling for none of those complicated and intricate calculations which form a feature of every race description. Blue Chuck jumped off in front, made the whole of the running, and won hard held by five lengths. Two horses of whose existence Educated Evans was profoundly ignorant were second and third. Smocker was pulled up half-way down the straight.

Educated Evans staggered down from the stand and into the paddock. His only chance, and it seemed a feeble one, was that the twelve horses that finished in front of Smocker would be disqualified. But the flag went up, and a stentorian voice sang musically, "Weighed in!"

Educated Evans dragged his weary feet to the train.

"It doesn't leave for an hour yet," said an official.

"I can wait," said Educated Evans gently.

Just after the last race "The Miller" came along the platform looking immensely pleased with himself. He saw Evans and turned into the carriage.

"Had a good race, my boy?" he asked. "I did, and thank you for the tip."

"Not at all," murmured Evans in the tone of one greatly suffering.

"They tried to lumber me on to Smocker, but no bookmakers' horses for me!"

"Is he a bookmaker's horse?" asked Evans with a flicker of mild interest.

"Yes, he belongs to that fellow Gibbet—the man who's engaged to Miss Homaster.

Educated Evans tried to smile.

"If you feel ill," said the alarmed Miller, "you'd better open the window."

SOMETIMES they referred to Mr. Yardley in the newspapers as "the Wizard of Stotford," sometimes his credit was diffused as the "Yardley Confederation "; occasionally he was spoken of as plain "Bert Yardley," but invariably his entries for any important handicaps were described as "The Stotford Mystery." For nobody quite knew what Mr. Yardley's intentions were until the day of the race. Usually after the race, for it is a distressing fact that the favourite from his stable was usually unplaced, and the winner (also from his stable) started amongst the "100 to 7 others."

After the event was all over and the "weighed in" had been called, people used to gather in the paddock in little groups and ask one another what this horse was doing at Nottingham, and where were the stewards, and why Mr. Yardley was not jolly well warned off. And they didn't say "jolly" either.

For it is an understood thing in racing that, if an outsider wins, its trainer ought to be warned off. Yet neither Bert Yardley, nor Colonel Rogersman, nor Mr. Lewis Feltham (the two principal owners for whom he trained) were so much as asked by the stewards to explain the running of their horses. Thus proving that the Turf needed reform, and that the stipendiary steward was an absolute necessity.

Mr. Bert Yardley was a youngish looking man of thirty-five, who spoke very little and did his betting by telegraph. He had a suite at the Midland Hotel, and was a member of a sedate and respectable club in Pall Mall. He read extensively, mostly such classics as Races to Come, and the umpteenth volume of the Stud Book, and he leavened his studies with such lighter reading as the training reports from the daily sporting newspapers—he liked a good laugh.

His worst enemy could not complain to him that he refused information to anybody.

"I think mine have some sort of chance, and I am backing them both. Tinpot? Well, of course, he may win; miracles happen, and I shouldn't be surprised if he made a good show. But I've had to ease him in his work, and when I galloped him on Monday he simply wouldn't have it—couldn't get him to take hold of his bit. Possibly he runs better when he's a little above himself, but he's a horse of moods. If he would only give his running, he'd trot in! Lampholder, on the other hand, is as game a horse as ever looked through a bridle. A battler! He'll be there or thereabouts."

What would you back on that perfectly candid, perfectly honest information, straight, as it were, from the horse's mouth?

Lampholder, of course; and Tinpot would win. Even stipendiary stewards couldn't make Lampholder win, not if they got behind and shoved him. And that, of course, is no part of a stipendiary steward's duties.

Mr. Bert Yardley was dressing for dinner one March evening, and, opening his case, he discovered that a gold dress watch had disappeared. He called his valet, who could offer no other information than that it had been there when they left Stotford for Sandown Park.

"Send for the police," said Mr. Yardley, and there came to him Detective-Sergeant Challoner.

Mr. Challoner listened, made a few notes, asked a few, a very few, questions of the valet, and closed his book.

"I think I know the person," he said, and to the valet: "A big nose—you're sure of the big nose?"

The valet was emphatic.

"Very good," said "The Miller," "I'll do my best, Mr. Yardley. I hope I shall be as successful as Amboy will be in the Lincoln Handicap."

Mr. Yardley smiled faintly.

"We'll talk about that later," he said.

"The Miller" made one or two inquiries, and that night pulled in "Nosey" Boldin, whose hobby it was to pose as an inspector of telephones, and in this capacity had made many successful experiments. On the way to the station, "Nosey," so-called because of a certain abnormality in that organ, delivered himself with great force and venom.

"This comes of betting on horse races and follering Educated Evans' perishin' five-pound specials! Let this be a warning to you, 'Miller'!"

"Not so much lip," said "The Miller."

"He gave me one winner in ten shots, and that started at 11 to 10 on," ruminated "Nosey." "Men like that drive men to crime. There ought to be a law so's to make the fifth loser a felony! And after the eighth loser, he ought to 'ang! That'd stop 'em!"

"The Miller" saw his friend charged and lodged for the night, and went home to bed. And in the morning, when he left his lodgings to go to breakfast, the first person he saw was Educated Evans, and there was on that learned man's unhappy face a look of pain and anxiety.

"Good-morning, Mr. Challoner. Excuse me if I'm taking a liberty, but I understand that a client of mine is in trouble?"

"If you mean 'Nosey,' he is," agreed "The Miller." "And what is more, he attributes his shame and downfall to following your tips. I sympathise with him."

Educated Evans made an impatient clicking sound, raised his eyebrows and spread out his hand.

"Bolsho," he said simply.

"Eh?" "The Miller" frowned suspiciously. "You didn't give Bolsho?"

"Every guaranteed client received 'Bolsho: fear nothing,' " said Evans even more simply "following Mothegg (ten to one, beaten a neck, hard lines), Toffeetown (third, hundred to eight, very unlucky), Onesided (won, seven to two, what a beauty!), followin' Curds and Whey (won, eleven to ten—can't help the price). Is that fair?"

"The question is," said "The Miller" deliberately, "Did 'Nosey' subscribe to your guarantee wire, your £5 special, or your Overnight nap?"

"That," said Educated Evans diplomatically, "I can't tell till I've seen me books. The point is this: if 'Nosey ' wants bail, am I all right? I don't want any scandal, and you know 'Nosey.' He ought to have been on the advertisin' staff of Shelfridges, or running insurance stunts in the Daily Flail."

The advertising propensities of "Nosey" were, indeed, well known to "The Miller." He had the knack of introducing some startling feature into the very simplest case, and attracting to himself the amount of newspaper space usually given to scenes in the House and important murders.

It was "Nosey" who, by his startling statement that pickles was a greater incentive to crime than beer, initiated a press correspondence which lasted for months. It was "Nosey" who, when charged with hotel larceny (his favourite aberration), made the pronouncement that motor 'buses were a cause of insanity. Upon the peg of his frequent misfortunes it was his practice to hang a showing up for somebody.

The case of "Nosey" was dealt with summarily. Long before the prosecutor had completed his evidence he realised that his doom was sealed.

"Anything known about this man?" asked the magistrate.

A gaoler stepped briskly into the box and gave a brief sketch of "Nosey's" life, and "Nosey," who knew it all before, looked bored.

"Anything to say?" asked the magistrate.

"Nosey" cleared his throat.

"I can only say, your worship, that I've fell into thieving ways owing to falling in the hands of unscrupulous racing tipsters. I'm ruined by tips, and if the law was just, there's a certain party who ought to be standing here by my side."

Educated Evans, standing at the back of the court, squirmed.

"I've got a wife, as true a woman as ever drew the breath of life," "Nosey" went on. "I've got two dear little children, and I ask your worship to consider me temptation owing to horse-racing and betting and this here tipster."

"Six months' hard labour," said the magistrate, without looking up.

Outside the court Mr. Evans waited patiently for the appearance of "The Miller."

" 'Nosey' never had more than a shilling on a horse in his life," he said bitterly, "and he owes! Here's the bread being took out of my mouth by slander and misrepresentation; do you think they'll put it in the papers, Mr. Challoner?"

"Certain," said "The Miller," cheerfully, and Educated Evans groaned.

"That man's worse than Lucreature Burgia, the celebrated poisoner," he said, "that Shakespeare wrote a play about. He's a snake in the grass and viper in the bosom. And to think I gave him Penwiper for the Manchester November, and he never so much as asked me if I was thirsty Mr. Challoner."

Challoner, turning away, stooped.

"Was that Yardley. I mean the trainer?"

"The Miller" looked at him reproachfully.

"Maybe I'm getting old and my memory is becoming defective," he said, "but I seem to remember that when you gave me Tellmark the other day, you said that you were a personal friend of Mr. Yardley's, and that the way he insisted on your coming down to spend week-ends was getting a public nuisance."

Educated Evans did not bat a lid.

"That was his brother," he said.

"He must have lied when he told me he had no brothers," said "The Miller."

"They've quarrelled," replied Educated Evans frankly. "In fact, they never mention one another's names. It's tragic when brothers quarrel, Mr. Challoner. I've done my best to reconcile 'em—but what's the use? He didn't say anything about Amboya, did he?"

"He said nothing that I can tell you," was the unsatisfactory reply, and left Mr. Evans to consider means and methods by which he might bring himself into closer contact with the Wizard of Stotford.

All that he feared in the matter of publicity was realised to the full. One evening paper said:

RUINED BY TIPSTERS

Once-prosperous merchant goes to prison for theft.

And in the morning press one newspaper may be quoted as typical of the rest:

TIPSTER TO BLAME

Pest of the Turf wrecks a home.

Detective-Sergeant Challoner called by appointment at the Midland Hotel, and Mr. Yardley saw him.

"No, thank you, sir." "The Miller" was firm. He never forgot that he was a public schoolboy (he rowed stroke in his school boat the year they beat Eton in the final), and he was in many ways unique.

Mr. Yardley put back the fiver he had taken from his pocket.

"I will put you a tenner on anything I fancy," he said. "Who is this tipster, by the way?—the man who was referred to by the prisoner."

"The Miller" smiled.

"Educated Evans," he said, and when he had finished describing him Mr. Yardley nodded.

He was staying overnight in London en route for Lincoln, and was inclined to be bored. He had read the Racing Calendar from the list of the year's races to the last description of the last selling hurdle race on the back page. He had digested the surprising qualities of stallions that stood at 48 guineas and 1 guinea groom, and he could have almost recited the forfeit list from Aaron to Znosberg. And he was aching for diversion when the bell boy brought a card.

It was a large card, tastefully bordered with pink and green roses. Its edge was golden, and in the centre were the words:

Mr. Yardley read, lingering over the printer's errors.

"Show this gentleman up, page," he said.

Into his presence came Educated Evans, a solemn, purposeful man.

"I hope the intrusion will be amply excused by the important nature or character of my business," he said. This was the opening he had planned.

"Sit down, Mr. Evans," said Yardley, and Educated Evans put his hat under the chair and sat.

"I've been thinking matters over in the privacy of my den—" began

Evans, after

a preliminary cough.

"You are a lion tamer as well?" asked the Wizard of Stotford, interested.

"By 'den' I mean 'study,' " said Evans gravely. "To come to the point without beating about the bush—to use a well-known expression—I've heard of a coop."

"A what?"

"A coop," said Evans.

"A chicken coop?" asked the puzzled Wizard.

"It's a French word, meaning ramp,' said Evans.

"Oh, yes, I see. 'Coup'—it's pronounced 'coo,' Mr. Evans."

Educated Evans frowned.

"It's years since I was in Paris," he said; "and I suppose they've altered it. It used to be 'coop,' but these French people are always messing and mucking about with words."

"And who is working this coop?" asked the trainer politely, adopting the old French version.

"Higgson."

Educated Evans pronounced the word with great emphasis. Higgson was another mystery trainer. His horses also won when least expected. And after they won little knots of men gathered in the paddock and asked one another if the Stewards had eyes, and why wasn't Higgson warned off?

"You interest me," said the trainer of Amboy. "Do you mean that he is winning with St. Kats?"

Evans nodded more gravely still.

"I think it's me duty to tell you," he said. "My information "—he lowered his voice and glanced round to the door to be sure that it was shut—"comes from the boy who does this horse!"

"Dear me!" said Mr. Yardley.

"I've got correspondents everywhere," said Educated Evans mysteriously. "My man at Stockbridge sent me a letter this morning (I dare not show it to you) about a horse in that two-year-old race that will win with his ears pricked."

Mr. Yardley was looking at him through half-closed eyes.

"With his ears pricked?" he repeated, impressed. "Have they trained his ears too? Extraordinary! But why have you come to tell me about Mr. Higgson's horse?"

Educated Evans bent forward confidentially-

"Because you've done me many a turn, sir," he said "and I'd like to do you one. I've got the information. I could shut my mouth an' make millions. I've got nine thousand clients who'd pay me the odds to a pound—but what's money?"

"True," murmured Mr. Yardley, nodding. "Thank you, Mr. Evans. St. Kats, I think you said? Now, in return for your kindness, I'll give you a tip."

Educated Evans held his breath. His amazingly bold plan had succeeded.

"Change your printer," said Mr. Yardley, rising. "He can't spell. Good-night."

Evans went forth with his heart turned to stone and his soul seared with bitter animosity.

Mr. Yardley came down after him and watched the shabby figure as it turned the corner, and his heart was touched. In two minutes he had overtaken the educated man.

"You're a bluff and a fake," he said, good-humouredly, "but you can have a little, a very little, on Amboy."

Before Educated Evans could prostrate himself at the benefactor's feet Mr. Yardley was gone.

The next day was a busy one for Educated Evans. All day Miss Higgs, the famous typist of Great College Street, turned her Roneo, and every revolution of the cylinder threw forth, with a rustle and a click, the passionate appeal which Educated Evans addressed to all clients, old and new. He was not above borrowing the terminology of other advertisement writers.

You want the best winners—I've got

them.

Bet in Evans' way! Eventually, why not now?

I've got the winner of the Lincoln!

What a beauty!

What a beauty!

What a beauty!

Confidentially! From the trainer! This is the

coop of the season. Help yourself! Defeat ignored!

To eight hundred and forty clients (the postage alone cost thirty-five shillings) this moving appeal went forth.

On the afternoon of the race Educated Evans strolled with confidence to the end of the Tottenham Court Road to wait for the Star. And when it came he opened the paper with a quiet smile. He was still smiling, when he read:

Tenpenny, 1.

St. Kats, 2.

Ella Glass, 3.

All probables ran.

"Tenpenny?—never heard of it," he repeated, dazed, and produced his noon edition. Tenpenny was starred as a doubtful runner.

It was trained by Yardley.

For a moment his emotions almost mastered him.

"That man ought to be warned off," he said, hollowly, and dragged his weary feet back to the stable yard.

In the morning came a letter dated from Lincoln.

Dear Mr. Evans,—What do you think of my coop?—Yours, H. Yardley.

There was a P.S. which ran:

I put a fiver on for you. Your enterprise deserved it.

Evans opened the cheque tenderly and shook his head.

"After all," he said subsequently to the quietly jubilant "Miller," "clients can't expect to win every time—a Turf adviser is entitled to his own coops."

Tenpenny started at 25 to 1.

SATURDAY night in High Street, Camden Town, and the lights were blazing and the tram bells clanging dolefully. About each gas-lit stall a group of melancholy sceptics, for the late shopper is not ready to believe all that loud-voiced stall-holders claim for their wares.

At one corner a dense, hypnotised crowd of men listening to a diminutive spellbinder, wearing a crimson and purple racing jacket over a pair of voluminous tight-gartered breeches.

"... did I tell yer people that Benny Eyes was no good for the City an' Suburban 'Andicap? Did I tell yer not to back Sommerband for the Metropolitan? Did I tell yer on this very spot last week, an' I'm willing to pay a thousan' poun' to the Temperance 'Ospital if I didn't, that Proud Alec could fall down an' get up and then win the Great Surrey 'Andicap? Did I ..."

One of the audience edged himself free from the crowd with a sigh, and, so doing, edged himself into a quiet-looking, broad-shouldered man, who was chewing a straw and listening intently.

"Good-evening, Mr. Challoner," said Educated Evans.

"Evening, Evans," said "The Miller." "Picking up a few tips?"

A contemptuous yet pitying smile illuminated the face of the learned Evans.

"From him?" he said. "Do you buy detective stories such as is published in the common press in order to learn policery? No, Mr. Challoner—I was a-standing there as an impartial observer an' a student of the lower classes, their cupidity and credulity bringin' tears to my eyes. I won't knock Holley—I know the man; he takes my tips, and goes and sells 'em to the common people. I don't complain, so long as he don't use my name. But the next time he professes to be sellin' Educated Evans' £5 specials for fourpence I shall take action! "

"The Miller" half turned, and, after a second's hesitation, Educated Evans fell in at his side.

"You don't mind, Mr. Challoner?"

"Not a bit, Evans. If I meet anybody I know, I can tell them afterwards I was taking you to the station." Evans winced.

"Doesn't it do your heart good to see all these people out and about, and every one got his money honestly by working for it?"

Evans sniffed.

"You know your own business best," he said cryptically.

"Perhaps they're not all horny-handed sons of toil," admitted "The Miller," as a familiar face came into his line of vision.

"If my eyes aren't getting wonky, that was old Solly Risk I saw—how long has he been out?"

Educated Evans did not know.

"The habits of the criminal classes," he said, "are Greek to me, as Socrates said to Julius Caesar, the well-known Italian. They go in and they come out, and no man knoweth. Solly is as wide as that famous African river, the Amazon, discovered by Stanley in the year 1743. But you can be too wide, and snouts being what they are—"

"Snouts?" said "The Miller," elaborately puzzled. What is a 'snout'?"

"It's a phrase used by low people, an' I can well understand you've never heard it," said Evans politely.

"If, by that vulgar expression, you mean a man who keeps the police informed on criminal activities," said "The Miller," who knew much better than Evans the title and functions of a police informer, "let me tell you that Solly was arrested on clear evidence. That's a bad cold of yours, Evans?"

For Educated Evans had sniffed again.

"As a turf adviser and England's Premier sportin' authority," said Evans, "I've me time fully occupied without pryin' into other people's business. I've nothing to say against Ginger Vennett—"

"The Miller" stopped and regarded his companion oddly.

"Get it out of your mind that Ginger is a snout," he said. "He's a hard-working young man—more hard-working than his landlord."

"Or his landlady," suggested Evans, and this time his sniff was a terrific one.

"I know nothing about his landlady except that she's good looking, hard-working and too good for Lee," said "The Miller," and Educated Evans laughed hollowly.

"So was Cleopatra, whose famous needle we all admire," he said. "So was Lewd-creature Burgia, the celebrated wife of Henry VIII, who tried to poison him by pourin' boilin' lead in his earhole. So was B. Mary, who murdered the innercent little princes in the far-famed Tower of London in—"

"Don't let us rake up the past," pleaded "The Miller." "Have you seen anything of Lee lately? They tell me he's gone into the harness business again?"

It was a deadly insult he was offering to Educated Evans, and nobody knew this better than "The Miller." He was actually inviting Evans to turn Nose!

"I'm surprised at you, Mr. Challoner," said Evans, genuinely hurt, and "The Miller" laughed and went on.

Everybody liked "Modder " Lee—so called because in his cups he had a habit of describing the battle of Modder River (in which he took part), illustrating the line of attack by the simple method of dipping his finger in the nearest pot of beer and tracing the course of the Modder on the counter. He was a good friend, a quiet, unassuming citizen, and more than a faithful husband and father to the pretty shrew he had married in a moment of mental aberration.

His one weakness was harness. The sight of a set of harness set his blood on fire and provoked him to unlawful doings. He had taken carts, and had walked away with horses and sold them at the repository under the very noses of their owners, but harness was his speciality.

"It's a hobby," he told his lodger, a tall, good-looking and fiery-headed young man, who did nothing for a living except back a few up and downers and run for a bookmaker. He used to represent a West End firm of commission agents until unprofitable papers appeared in the bunch, and they discovered he was getting quick results over the tape at the Italian Club.

He had been a client of Educated Evans; but, following a dispute as to whether he had or had not received a certain winner (odds to 5s.), Educated Evans had struck his name from the list. And this was a source of great distress to Ginger, for he reposed an unnatural faith in the prescience of the educated man.

"I know more about harness," said Modder Lee, with pride, "than any other man in the business. I can walk down High Street and price every set I meet, and I'll bet that I'm not five shillings out! "

One night the stable of Holloway's Provision Stores was broken into, and a double set of pony harness was missing. Two nights later came an urgent call from Lifton Mews. A set of carriage harness, the property of Lord Lifton himself, had vanished....

"The Miller" made a few independent inquiries, met (by appointment and in a dark little street) a Certain Man, and made a midnight call at 930 Little Stibbington Street.

"The Miller" did not call at Little Stibbington Street to inquire after Lee's health, nor was it a friendly call in the strictest sense of the word. Mrs. Lee was in bed, and answered the door in a skirt, a shawl, an apron, and a look of startled wonder. Later, in the language of the psalmist, she clothed herself with curses as with a garment—for she was, ostensibly, a true wife.

"If I never move from this doorstep, Mr. Miller, and I'm a Gawd-fearing woman that's been attendin' the Presbyterian Church in Stibbington Street off an' on for years, if I die this very minute, my old man hasn't been out of this house for three days with rheumatics antrypus. Without the word of a lie, he can't move from his bed, and you know, Mr. Miller, I've never told you a lie—'ave I? Answer me, yes or no?"

"Let me talk to Modder," said the patient "Miller."

"He's that ill he wouldn't know you, Mr. Miller," she urged, agitatedly (if the neighbourhood, listening in to a woman, had not heard the agitation appropriate to the moment, she would have been condemned). "I haven't been able to get his boots on for days. He's delyrius, as Gawd's my judge! He don't know anybody, and, what's more, it's catching—measles or something—and you with a wife and family, too."

"I've caught measles before, but I've never caught a wife or family," said "The

Miller " good-naturedly.

"He won't know you." The reluctant door opened a little wider. "Mind how you go—the pram's in the passage, and the young man lodger upstairs always leaves his bit of washing to dry...."

Wet and semi-dry shirts flapped in the detective's face as he made his way to the back room, illuminated by a small oil lamp.

Entering, he heard a deep groan. And there was Lee in bed, and on his face a wild and vacant look.

"He won't know you," said Mrs. Lee, performing her toilet with the corner of her apron. In support of her statement Modder opened his mouth and spoke faintly.

"Is that dear mother?" he quavered. "Or is it angels?"

"That's how he's been goin' on for days," said Mrs. Lee, with great satisfaction.

"I 'ear such lovely music," said the tremulous Modder. "It sounds like an 'arp!"

"The Welsh Harp," said "Miller." "Now come out of your trance, Lee, and step round with me to the station—the inspector wants a talk with you."

Mrs. Lee quivered.

"Are you goin' to take a dyin' man from his bed?" she asked bitterly. "Do you want to see yourself showed up in John Bull?"

"God forbid!" said "Miller," and with a dexterous twist of his hand pulled the bedclothes from the invalid. He was fully dressed, even to his boots, and packed between his trousered legs was a new set of harness of incalculable value.

"It's a cop," said Lee, and got up without assistance. "There's a snout somewhere in this neighbourhood," he said, without heat. If I ever find him, I'll tear his liver out. And his lights," he added, as he remembered those important organs.

It was his ninth offence, and Lee, as he knew, was booked for that country house in Devonshire near the River Dart and adjacent to the golf links of Tavistock.

Having vindicated her position as a true wife and faithful helpmate, Mrs. Modder Lee returned to her honorary status of Respectable Woman. "The Miller" saw her coming out of a picture house with the red-haired lodger, and she tripped up to him coyly, a smile upon her undoubtedly attractive features. "The Miller" always said that if she had had the sense to keep her mouth shut she might have been mistaken for a French lady. He specified the kind of French lady, but the description cannot be given in a book that is read by young people.

"Oh, Mr. Challoner, I do owe you an apology for all the unkind things I said," she said, in her genteel voice; "but a wife must stick up for her husband, or where would the world be, in a manner of speaking?"

"That's all right, Mrs. Lee," smiled "The Miller," and glanced at her escort. I see Vennett is looking after you."

Mrs. Lee launched forth into a rhapsody of praise.

"He's been so good to me and the children," she said. "He's got a bit of money, and he doesn't mind spending it either—you've no idea how kind he's been to me, Mr. Challoner!"

"I can guess," said "The Miller."

"The Miller" was a philosopher. He accepted, in his professional capacity, a situation which sickened him to think about as a man. One morning he met Educated Evans at the corner of Bayham Street, and that learned man had on his face a look of peace and content which did not accord with his record as the World's Premier Turf Adviser. For Educated Evans had sent out three horses to his clients, of which two had finished fourth and fifth, and the third absolutely last, as "The Miller" knew.

"It's no good talking to me, Mr. Challoner," said Educated Evans firmly. "My information was that Rhineland could have run backwards and won. He was badly rode, according to the sportin' descriptions, and my own idea is that the jockey wasn't trying a yard."

"If Statesman doesn't win—" began "The Miller" threateningly, and Evans' face changed.

"You ain't backing Statesman, are you?" he asked.

"I've backed him," said "The Miller," and Educated Evans groaned.

"Then you've lost your money " he said with resignation.

"The Miller" frowned.

"I saw Ginger Vennett and he told me you'd given it to him as the best thing of the century that you had had this from the owner and that you told him to put every farthing he had in the world on it. What's the idea, Evans?"

"The idea is " said Mr. Evans speaking under the stress of great emotion, "that I want to put that snout where he belongs —in the gutter!"

"The Miller" gasped.

"Do you mean to tell me that you twisted him?"

"I do," said Evans savagely. "He's got all his savings on Statesman, who hasn't done a gallop for a month. If you've been hoisted with his peter, to use a naval expression, I'm sorry, Mr. Challoner; but I've got one for you on Saturday that can't lose unless they put a rope across the course to trip him up."

"The Miller" hurried away to the nearest telephone and called up Mr. Isaacheim.

"It's Challoner speaking, Isaacheim," he said. "That bet you took about Statesman—I think you'd better call it off."

"All right, Mr. Challoner," said the obliging Isaacheim. "I don't think much of it myself: the horse hasn't done a gallop for a month, and Educated Evans told me

"I know what Educated Evans told you," said "The Miller"; "but it's certainly understood that that bet's off."

In the afternoon "The Miller" bought an evening newspaper and turned to the stop press, and the first thing he saw was that Statesman had won

When, in the evening, he discovered that the price was 25 to 1, he went in search of Educated Evans, and found that sad man on the verge of tears.

"I did my best. It's no good arguing the point with me, Mr. Challoner," he said. "I've had Ginger round here congratulating me, but telling me that he'd forgotten to have the bet, and that's about as much as I can stand. The only thing I can tell you is don't back Blazing Heavens in the two-thirty race to-morrow, because I've give it to Ginger, and I've asked him, as a man and a sportsman, not to tell anybody, and to put his shirt on it. Revenge," he went on, "is repugnant to my nature. But a snout's a snout, and if I don't settle Ginger, then I'm an uneducated man—which, of course, I'm not," he added modestly.

Obedient to his instructions, "The Miller " refrained from backing Blazing Heavens, and, under any circumstances, would not have invested a red cent on a horse that had 21 lb. the worse of the weights with Lazy Loo. And Blazing Heavens won. Its price was 100 to 6.

Ginger sent a boy with a ten-shilling note to Educated Evans, and asked for his special for the next day.

Educated Evans sat up far into the night examining and analysing the programme for the following day, and at last discovered a certain runner, that not only had 14 lb. the worse of the weights, but enjoyed this distinction, that the training reporters of the sporting Press, who usually have something kind to say about every horse, dismissed him with a line : "Ours has no chance in the Tilbury Selling Handicap.

He saw also a paragraph in the following morning's newspaper that Star of Sachem—such was the elegant nomenclature of this equine hair trunk—was being walked to the meeting because his owner did not think that he was worth the railway fare.

Ginger came round to see Evans at his den; and Ginger was wearing a new gold chain and two classy, nearly-diamond rings, a new hat, and a tie of brilliant colours.