RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library.

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

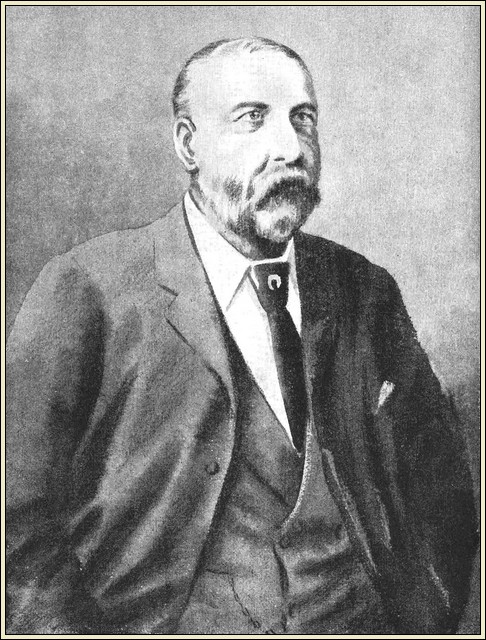

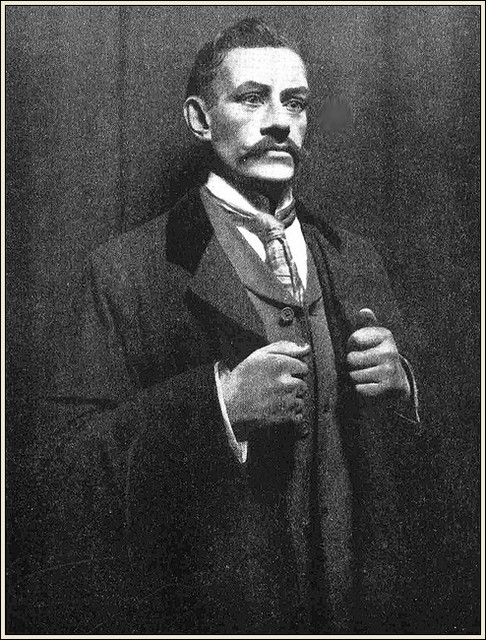

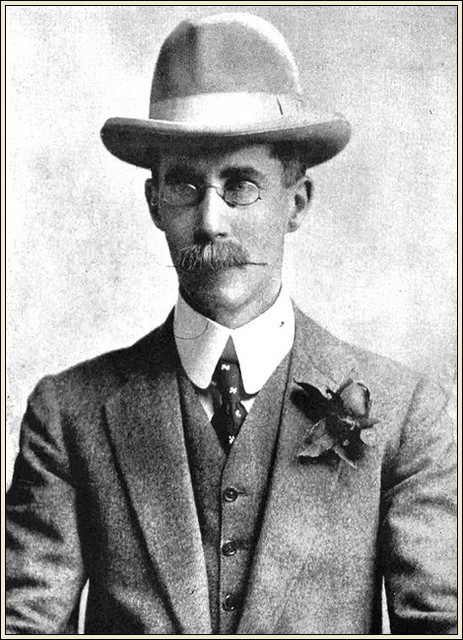

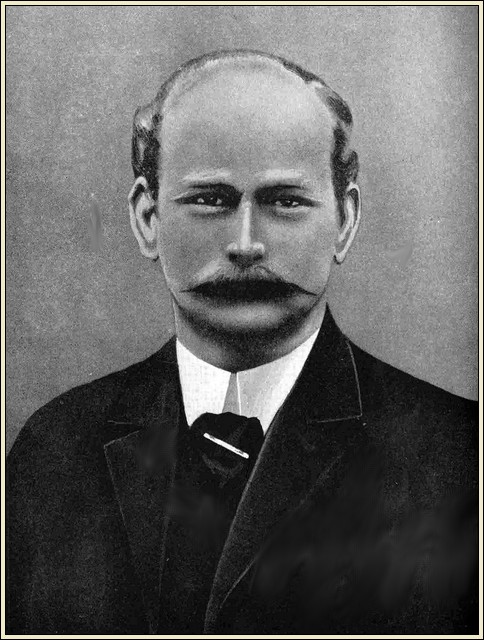

EDGAR WALLACE made his name as a journalist with a series of reports from the Second Boer War written for the London Daily Mail in 1900-1902.

In 1901 Hutchinson & Co., London, published 41 of these reports under the title Unofficial Dispatches of the Anglo-Boer War. In 2012 RGL published an expanded version of this collection containing 65 articles, some of which were written after the war. (See Reports from the Boer War).

After the Second Boer War, Wallace continued to write for the Daily Mail while he pursued his career as an author of sensational detective fiction. Throughout most of his subsequent life he contributed articles, essays and sketches to this and other periodicals.

With Edgar Wallace—Journalist RGL offers a collection of these articles from the sources indicated after each title. They are presented in chronological order. They do not include the articles from Reports from the Boer War, or from Red Pages from Tsardom and This England: Studies of To-day, which RGL has published separately.

This collection will be revised and expanded as further newspaper and magazine articles by Edgar Wallace become available.

—Roy Glashan, 4 October 2020.

NOTHING outside the equipages of Royalty created so much sensation and called for greater admiration than the wonderful state coaches in which, some of the members of the peerage drove to and from the Abbey. The Duke of Marlborough and his Duchess rode through admiring crowds in a deep-crimson coach with real silver fittings, which evoked, loud cheers. Consuelo, Duchess of Manchester, appeared in a coach simply dazzling, with a gorgeous hammer-cloth, which was only equalled by that of the Duke of Somerset's new coach, whose hammmer-cloth cost him over £800. The Northumberland state carriage was a magnificent affair in white and silver, carrying ten people altogether, five of the family inside, and an equal number of the most elaborately and gorgeously appointed servants clinging to the outside. One of the most moving moments on Constitution Hill was when a strange little company of white-haired men with medals on their coats came marching—slow and stiff, but very proud and erect—to one of the stand's. They were the survivors of the charge of Balaclava. The Green Park was alive with fluttering handkerchiefs, and cheers went up from the stands.

Never before in the history of England have grandchildren of the Sovereign in direct line of succession been present in the Abbey at the Coronation. The Coronation, it is estimated, cost £125,000. When Queen Victoria was crowned the cost was £69,401, at the crowning of William IV, £43,159, and the Coronation of George IV, £243,388.

Two ladies with a bag of provisions took up a position on the rising ground in Picadilly before midnight. They whiled away the night reading by the light of a bicycle lamp tied to the park railings. After waiting nearly fifteen hours they only saw the procession through the kindness of a policeman. When the route was cleared the crowd got in front of them, but the constable, knowing how long they had waited, considerately passed them through to the front.

Mr Edgar Wallace in the Daily Mail thus describes the return of the King:—

"AND now the Horse Guards, and in their rear a glimpse of a golden panoply. No need to consult your programme, the hurricane of cheers, the tossing hats, the shrill acclamations of the women proclaiming unmistakably—the King!

Nearer... the escort passes, and the finicking cream ponies pick their way daintily. Crane forward... The King is smiling—bowing and smiling. How well he looks. Left and right he bows, the great crown glittering on bis head. You only see him for a second. It is a glimpse of a very happy man—a proud, contented man. A man, who has gripped death by the throat and of his unconquerable will triumphed.

It is only a glimpse, for hardly does your eye rest on him than you attention, your cheers, your love, is claimed by the beautiful woman who sits by his side. Not smiling—but the face of a woman whol is silently praying. Silent, and lovely, we do her homage for the moment, and then she passes, and something like a sigh runs through the crowd, and they forget to watch for the Prince of Wales, but follow the great swaying coach with a happy man and the pale woman with wistful eyes. The Duke of Connaught and his soldier son you forget to notice. The Duke of Portland, the Duke of Buccleuch pass—the King's procession ends.

The interest dies momentarily, the passing gorgeous uniform might be so much drab for all the effect it has upon the spectator. Heads craned forward to see the last of the King's carriage. Then the band crashes "God! save the King" again—it is the Prince of Wales's coach passing. "Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful," says an old lady, touching an arm, and tears stand in her eyes. "What?—the procession?" "No, sir; the Queen. Wasn't she lovely."

There was no lack of comic relief in the various incidents in the vicinity of the Abbey. One of the peeresses, exhausted by long waiting for her carriage, sat down in despair on the ground in the courtyard with her velvet robes folded under her as a cushion, while her husband sought the erring coachman attired in his velvet and miniver. Another peer rushed, coronet in hand, down the streets calling for a hansom, receiving an impromptu ovation from the crowd, which disconcerted him a little.

One of the most beautiful moments was the crowning of the Queen, which was performed with her Majesty kneeling. As her Majesty passed to her footstool the four duchesses advanced to hold the canopy. Their crimson trains were spread fan-wise, and when her Majesty rose their trains were readjusted by four gentlemen. The Duchess of Buccleuch's page did the same to her Grace's train. The King and Queen were evidently quite au fait with the whole ceremony, and on more than one occasion, when hesitation occurred, guided the procedure. The Queen was assisted by the Bishop of Oxford, who took her hand whenever there was a step to mount.

The crowning of the Queen was a much shorter function, but it gave rise to one of the most extraordianry effects possible. At the moment that the crown was placed on her head each peeress put on her coronet, and, as seen from the peers' stand, the whole bank of fluttering down opposite was in a flash converted into one great white trellis work, in every opening of which a face was framed. This singular illusion was produced by the hundreds of pairs of white-gloved arms all simultaneously being raised to an angle over the head.

The Maharajah of Scindia's jewels were brought to the Abbey the evening before the Coronation. Previous to the ceremony his Keeper of the Jewel's attended, and in one of the robing rooms the jewels were put on. An eyewitness describes the Indian Prince as being "swathed in diamonds."

The value of the actual contents of Westminster Abbey during the ceremony is perhaps such as no human brain could estimate. Apart from the regalia, the worth of one single diadem, the Queen's crown, is computed at £100,000. The solid gold plate belonging to the Abbey and the Chapels Royal, if melted down, would buy several warships. An increased value is added by history, each piece having been the property of some English sovereign.

Everybody admired the Queen's crown. It was specially made for the, occasion, and was composed entirely of diamonds, each of which is mounted in a silver setting. This is the only precious metal which comlpletely shows the brilliance of fine stones. Gold is only used on the inner and hidden portions of the mounting, for the sake of lightness and strength. The circlet, unsurpassed in effect by that of any existing crown, is 1½ inches in width, and is entirely encrusted with brilliants of the finest water. These diamonds, varying in size from one specially fine in color weighing, nearly 17 carats, down for the smallest necessary to carry out the design, are of the most perfect cutting, and are placed as closely together as possible throughout. This method is adopted so that no metal is visible, and renders the entire circlet one blaze of light. This rich band supports four large cross-patées, and thee largest of these displays the Koh-i-Noor, the grand and unique feature of the orown. Three very large diamonds of extraordinary lustre occupy the centres of the other cross-patées. The total number of stones used is 3,688.

By her Majesty's special command the crown was constructed as lightly as possible—an immense advantage when in use. Every effort experience and skill could dictate resulted in keeping the entire weight down to only 22oz 15dwt, a result never before attained.

HE was seventy years old, was this Habitant, and his name was Du Bois. As a matter of fact, it is still.

His face is lined and seamed with the joys and sorrows of his years. A large, generous mouth, grey twinkling eyes, a chin white with the stubble of three unshaven days, and a hand heavy and big. He smokes—and smoked—a tobacco which smells like nothing so much as a conflagration in a soap factory. Often as not he grows it himself, and its aroma reminds you of the fact that tobacco is sometimes called a weed. His French is the French of Louis Quinze, his English is broken and charming. His piety and devotion to Holy Church are beautiful in their simplicity, and his sentiments are Canadian. If he is more than usually progressive they are Canadian-French.

He appeals to me, this Habitant, as a most unregenerate, lovable, treasonable rogue. A big-hearted, gentlemanly Anglophobe. I think I rather like him for his native antipathies. I do not know whether this speck of grit in the national bearings is not almost as healthy as over-much lubricant. Nor do I think I am doing him an injustice when I point out this—from a British point of view—weakness of his. He sees things out of proportion, does this Habitant. There is a story told which illustrates this.

THE French lumberman who came down from the backwoods, where news is scarce, found Quebec in mourning.

"De Queen ees dead," explained an acquaintance.

"Mon Dieu!" said our lumberman, and then, thoughtfully, "Who have got de job?"

"Edouard," was the reply.

"Ba gosh," and the lumberman grew more thoughtful, "'e mus' have good pull wit' Laurier!"

It is a little world of its own, French Canada. Outside

its limits there is nought worthy of consideration. And it is a

beautiful world. A world of forests, dark and sweet-scented; of

broad-bosomed rivers and flashing mountain streams. A world of

snug homes and kindly curés, of little fenced gardens and

big fenced fields. A world that wakes with white dawns, and works

from the moment the red sun gilds the village spire till the

spire's cracked bell tinkles the Angelus. Horny-handed, bowed-backed, hard-faced, and simple-minded are the people of this

world, earning their living by the sweat of their brow year in

and year out without question or complaint. Content to till and

harvest as their fathers did before them: happy to live the life,

hopeful to die the death, of their class and kind, such is the

way of les Habitants.

WHETHER they love England little or much; whether or not they look askance at an Imperialism unifying the aspirations of—to them—an alien race; wherever and however their ideals be grounded, or their conscious efforts directed, they are none the less excellent citizens of Canada, and helpful, however unwillingly or unconsciously, in the building up of Greater Britain. They are an atomic survival of mediaevalism; their laws, their customs, their very speech are relics of another age. The Grand Seigneur, with his High Rights, passed not more swiftly in France than did the Reds of the Midi—that hungry, heroic crowd—in their march northward. Untouched by the bloody shear that worked a frenzied people's will, intimidated by no loaded tumbril jolting a pallid aristocracy to destruction, the Grand Seigneur is to-day a person—in Quebec. Perhaps he profited by example, and perchance his right of pillory, pit and gallows, and others more unspeakable, are as so many shadows; perhaps he has grown bourgeois, and instead of exercising his lordly will to remove the popular grievance, he writes to the newspapers—but there is sufficient of the old sieur left to be remarkable. "Quaint old Quebec," they call the town of that name. Quaint is the term that describes all French Canada. And as to loyalty to Great Britain—bear with me while I sound the Habitant, and piece together from his broken English the sentiments of Habitant Canada.

"PLAINTEE Englishman come to Canada now: on Ste. Rose dey come also—et ees mos'ly politique-fiscalité, yas?"

Crudely enough I put the fiscal problem before him in a few words.

"I s'pose mese'f dat beeg beezness on Englan'—Yas? Milor' Chamb'lan—pardon, M'sleur Chamb'lan—mak' plenty troub' wit' de fisc. De Canayen-Français, you compren', not de Englishman-Canayen—hees not worry wit' fisc or w'at Englishman t'ink. You tink dat cur'is? Mais!"

It is just lovely to listen to him, this seared old man with the patient smile. He is so artless in the confession of his political faith, he is so confident in the honesty of his views. Sometimes, abandoning the rugged, home-made reasoning, bejewelled with metaphor of forest, field, and river, he drops into the stilted dogmatics of his favourite newspaper. You recognise as you listen, and welcome almost as a friend, the tricky phraseology of the partisan leader-writer. Then he breaks back to the lake and the rapid as texts for his little sermon.

"Englan' she lak man dat tak' canoe d'écorce on beeg rapide. One tam she float firs' rate, ev'ryt'ing smoot' lak glass. Dat w'en you mak' beeg beezness wit' all worl', eh? Bimeby n'odder contree cam' long, an' dey tak' leetle bit your beezness, an' den n'odder she tak' leetle bit, an' den n'odder. Som' lak you tak' canoe up rapide, she mak's dam' hard. So Chamb'lan 'e say, 'De curran she run too fas' as we can pull—we mus' mak' de grande portage—yas?'"

Briefly, I sketched to the Habitant the possibilities of preferential tariffs, and the closer union of the Empire. That portion of the scheme which deals with the question of a contribution to Imperial defence met with his emphlatlc disapproval.

"W'AT use mak' de foolishness lak dat?" he inquired—for him— impatiently. "S'pose you mak' trouble wit' La Russ; you 'ave beeg war wit' her—you holler out, 'Come, Jean Du Bois, I mak' beeg fight wit' La Russ, you com' right 'long an' bring wit' you all de frien's you can fin.' I say, 'La R:uss don' mak' troub' w't' me, w'y shall I mak' worry wit' de Englishman, her beezness?'"

All of which, as I sternly explain ed to the Habitant, is most dreadfully unpatriotic. And what is patriotism? asked my Habitant.

"Love for your country," answered I, unthinkingly, "and a readiness to sacrifice, if needs be, your life at her need."

The Habitant looked a little puzzled. This, said he in effect, is my country. Here was I horn as was my father before me. Here are my children and my grandchildren. I know these lakes, these woods, these fields, as I know my own garden. My grandfather fought for this land, driving out the Yankees in 1812, while I carried my rifle in the Fenian invasion. I speak French, but France is not my home. I live under the British flag, but England is nothing to me. I am a Canadian first and last, and if he who loves his country best is the finest patriot, then there is no greater patriot than I.

Briefly this is the attitude of French Canada. It is actively loyal to Canada; it is not actively disloyal to Great Britain. "Canada first," this is its motto. Only there is really no second—absolutely none. If you can understand a passion for Quebec, with an apathy for the rest of Canada, and an attitude of supreme indifference toward the remainder of the British Empire, not to say the civilised world, you can understand the French-Canadian and place him at his value. He is not an Imperialist, he is not a "Rule Britannia" loyalist: he represents Isolated Parochialism at its best and worst; he is an anachronism, a bit of the seventeenth century living on the fringe of the twentieth. And, withal, he is rather lovable: if his outlook is narrow, his humanity is broad: if his ideas are small, his heart is large. I like the Habitant—Toronto, forgive me—on first acquaintance he is pleasing, Perhaps if I had to live alongside him all my life— But then, I have not.

THE cable messages have given some slight indication of the deep feeling of resentment felt by Canada at the recent judgment of the Alaska Arbitration Tribunal, but though the newspapers raged and gave "scare-head" captions to their articles upon the subject it would appear that the elder colony of the Empire maintained a very dignified and sensible moderation over the judicial reverse which her people so keenly felt. The utterances of her leading statesmen have shown that the tie with the Motherland will survive the strain of many Alaskan awards. It is interesting, however, to learn how Canadian sentiment was affected by the decree of the Commission, and this is graphically told by Mr Edgar Wallace, the able war correspondent of the Daily Mail, who happened to be in the Dominion at the time. Mr Wallace writes:

"TO deny that Canada is at the present moment boiling over with honest wrath would be to deny that she possesses any sense of rectitude, and that the spirit which she has inherited from the Motherland, that abhorrence of injustice which made a teapot of Boston Harbor, is still existent. How it strikes you at Home I cannot gauge, but here in the heart of the Dominion, where every man's first thought is of his country and where patriotism swamps the personal equation, to one catching the spirit of the people, and in one's sympathy unconsciously expatriating oneself from Britain, there comes a momentary glimpse of that inbred distrust of Englishmen and English methods that is characteristic of the colonial attitude toward the Mother Country.

"Rightly or wrongly—I am too near Hades to take a dispassionate view of the Higher Criticism—the decision of the Commission has widened the cracks and fissures in the Imperial fabric to such an extent that one holds one's breath lest a little extra strain should rend the structure from crown to base, and split this great Empire as easily as lightning might cleave an oak. You have only to think how near we have been to losing South Africa when it was the toss of a penny whether or not the Vierkleur should float from Capetown to the Zambesi; you have only to remember how we lost the great country that lies to the south of Canada and to realise that the hundred years that have brought the steam engine and the electric telegraph have not changed emotional mankind—since emotions are not a matter of education, and the feelings of the man who slips on the sidewalk are identical with those of William of Normandy who tripped on the English foreshore—to know that British injustice—as we see it here—has again set a colony aflame with impotent rage, and the work of the last few years of sane Downing street administration has been undone, in as few minutes.

"You may talk to the Canadian until your breath fails, and you will never convince him that Great Britain is not prepared at all times to sacrifice Canadian interests to gain the goodwill of the United States. Despite your Anglo-American societies, your flag-wagging, musical-hall outbursts of foolish sentimentality, the eternal clap-trap of the destinies of the Anglo-Saxon races—meaning the Anglo-American races—the Canadian knows what you in England do not know: that commercially and naturally the Yankee is the worst enemy Great Britain has in the world; that nowhere is England more hated, that nowhere in the world was news of British disasters in the late war received with greater glee and more joyous celebration than in the Union.

"Here stories of unspeakable atrocities were given the freest circulation, cartoons depicting John Bull in humiliating circumstances were without exception the only kind published. Tariffs designed to strike at Britain and Canada were erected, and Canada being close at hand has felt the full lash of 'our cousin's' venom. And all this time, the English statesmen have been preaching the doctrine of closer relations with the United States, Canada has been standing with her back to the wall, fighting for "dear life against the attacks of this cousin of ours. Do not think I am extravagant or intemperate. It would be impossible for me to attempt to convey, except in the slightest degree, the strength of the feeling between these two countries, a feeling which is accentuated to bitterness by the finding of the Alaska Commission.

"Canada has an excellent memory. There is not a child from school who could not tell you the story of the Ashburton treaty, by which Canada lost her free seaport on the east and a great wedge of country which now constitutes the State of Maine. There is a legend, too, of that same treaty by which, in addition to the country on the east, Canada lost the States of Washington and Oregon on the west; that these two States were lost because the Commissioner, a great fisherman, could not catch salmon with fly in one of the rivers and consequently handed over a country containing so worthless a stream to the Union! It is only a legend, and there is probably nothing in it, but it is one that is half believed in Canada, and who shall say, with a knowledge of the eccentricities of English statesmanship before them, that Canadians do wrong to credit the seeming absurd?"

HAVING thus pictured Canadian sentiment as it is, the correspondent proceeds to outline the possible consequences. He does not believe for one moment that as a result the preference granted to the Mother Country will be withdrawn. Canada is too large-minded, too broad-visioned, to play the tit-for-tat game. But she may well reconsider the question of tariffs if. the unmistakeable voice, of England rejects Mr Chamberlain's proposals, calculated to encourage her agricultural industries. Canada, Mr Wallace declares, will never join the Union. Washington's dream of a united American from the Tropic to the Arctic can never be realised. American as they are in habit, in method, in literature, and—to the Britisher inexperienced in the niceties of accent—in tongue, yet they are as distinct from the Yankee in thought, sentiment, and morality as is New Orleans from Dawson. Canada's natural way is the way of independence. Unhampered and untrammelled by overmuch interference from Downing street she is steadily following the inevitable course of her great destiuy. If she is turned aside it will be towards England. If England does not invite her before she passes out of reach or earshot she will make for nationality. At present Great Britain's hold on the colonies is purely nominal—there may come a time when the assumption of "possessing" such a colony as Canada will be farcical. There may, too, come a time when if England's invitation is not too tardy, and Canada, harkening, inclines her steps toward the Mother Country when the Canadian and the British interests will so blend and be so indispensable one to the other that the question of separation will be as remote as the days when Anglia and Northumbria stood for distinct national ideals.

Montreal, Canada, November 7, 1903

I WAS asleep when I tumbled out of a Pullman on to an almost deserted platform. I dreamt still of the morning glories of the Hudson river, the sheer, green-dappled banks, and the broad, lordly stream; the blue Katskill Mountains rising fold on fold, the hidden heights of the Adironacks, the wondrous beauty of the autumnal foliage, and the grey lakes in the twilight of the forests. It was one long, confused dream.

I dozed as I handed my keys to the Custom-house officer, and what time he was laying bare the mysteries of my wardrobe I was mentally surveying the bleak baggage-room for something comfortable to sit on. In a haze I walked to my cab and sank blissfully into its snuggest corner. It was the driver who roused me to wakefulness "Où vous descendrai-je, m'sieu?" he asked.

Then it was that I knew my journey from New York was indeed completed, and I was in Canada. It is one of the annoyances that beset the path of the travelling Imperialistic Britisher that there is something in the language or custom of nearly every British dependency calculated to impress him with his own crass ignorance. It is so much simpler and easier to be a stay-at-home Little Englander, to ignore the Colonies as factors in our national life, to dismiss their importance with a wave of the hand, and settle their complex problems—conveniently translated into English by obliging partisans—with a stroke of the pen.

Because if you want to get down to bedrock principles, to investigate conditions and grievances at first hand, you must, before you start off on your quest, take a thorough course in languages, which will include French, Dutch, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Hindustani, Tamil, Chinese, Asiatic, Greek, and about three hundred separate and distinct native dialects. Thus will you be able to hold converse with your fellow-subjects the Empire over from Canada to Cyprus, and from Hong-Kong to Gibraltar.

Here in Montreal a somewhat fragmentary knowledge of the "taal" helps me not at all. For two-thirds of the citizens are French, the policemen, the postmen, the very elevator boys in your hotel speak but broken English, and the more influential portion of the city's Press is printed in the language that the unintelligent Englishman associates with menus. This is a fact forcibly brought home to the unlettered stranger, for whom the oft-repeated warning in park and square, "Ne passez pas sur le gazon," has no especial terrors, so that he will transgress with a blissful tranquility of mind until a kindly policeman brings hian back to what are literally the paths of righteousness.

And this is Montreal: Imagine a beautifully-dressed woman, in down-at-heel slippers, or a city of noble buildings—and primitive roadways; imagine a city with cathedrals built on the plan of St. Peter's at Rome and Nôtre Dame of Paris—with wooden side-walks. Electric cars whiz over corded roads, and broughams and motor-cars jolt unevenly along the tree-fringed avenues. Montreal is the worst-paved city in the world, considering its pretensions, considering, too, that here we have the New York of Canada, the London of the West.

Perhaps the former title better suits this mother of cities. French-American she is essentially. Forget, the fact that orchestras play "God Save The King" at the end of performances: that that population's loyalty to the Throne, is unquestionable—forget these, and there will be no single thing to remind you that you are on British soil. The stamp of America is on the town and on one-third of the people, and Holy Rome looks down from a dozen emulating spires and turrets with a benign eye upon the faithful majority.

American in commerce, American in habit—we drink ice-water for breakfast and in driving keep to the right—American in speech, in thought, and—except for the reverence it has for the Throne and Person—in sentiment, it promises, if it be the microcosm of a composite Dominion, to render the student's path by no means one of roses.

For here in Montreal you have every evidence of a dominant Roman Catholicism, a religious dictatorship, a power which, scornful of dissemblance and fearless of criticism, might well stand behind a Government or a people indicating its requirements and urging its demands, strong within the unassailable battlements of its sanctity.

For good or for ill the power of the priesthood stands as a very real and tangible factor in the future of this Colony. For good one cannot but think, since the traditions of Canada are made glorious by the memory of her brave priests' deeds, and since foremost among her pioneers went these pale-faced, dark-eyed priests, carrying with that fearlessness which is equally shared by fanatic and fatalist the elements of Christianity to the wigwams of the Iroquois. And since Montreal owes its very existence to the attempt made a century ago to form a veritable kingdom of God on American soil, the manifestation of this ideal cannot fail to be gratifying to those who believe—as some do—that the progress of a country is naturally coincident with the prosperity of the Roman Church.

I have spoken of Montreal as being the New York of Canada, and it does seem, from ite very position, that not only will it be to Canada what New York is to the States—as indeed it already is—but in course of time, remembering the enormous resources of Canada, it will be equal in wealth, population, and importance. Like New York, practically an island town, it has greater opportunities for expansion, and if it has the disadvantage of being closed to river traffic for certain months in the year owing to its frozen waters, it is far nearer to a free seaboard—free in a purely climatic sense—than is that other great lake town, Chicago.

The French-Canadian of Montreal cares little enough for the future; lives very much for to-day. See him, clean-shaven, sharpfeatured, somewhat sallow, and wearing his hair in a sleek, rigidly-trimmed bunch at the back of his head. Slightly below the medium height, yet a man of some brawn; lithe and alert in his movements, voluble and buoyant in his speech, remarkably expressive in his gesticulations—a Frenchman who can ride, shoot, swim, or row—that is the French-Canadian. He is much more of an athlete than his brother across the Channel. He is less emotional, cooler-headed, and has such a fund of common sense as to almost denationalise him. Essentially be is a Frenchman, and yet—

Perhaps it is that he has absorbed something of the qualities of his English neighbor; perhaps its is only that he is French and not Parisian—we sometimes confuse the types. At any rate, he is an excellent companion this Frenchman. When he gets over the natural suspicion with which all Continental races regard the Englishman he will become expansive.

QUEBEC is a bit of old France transplanted across the ocean; Montreal is twentieth-century American in the middle of the street tapering off to Louis Quinze sidewalks; Toronto is openly, unblushingly American in a hustling, unwearying fashion—this you will find if you do business in this queen of cities. Toronto is also aggressively British, and Orange at that.

Exactly whether the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne is observed I cannot say, but this I know—Toronto is Orange.

Ottawa is the cleanest of little towns. Here England and France hold equal sway, and here every man you meet who is not a Civil servant is a Yankee drummer.

Leave behind you Montreal and Quebec, Ottawa, and Toronto, and the lesser towns about. Go north from Toronto, straight up the map to where the Canadian Pacific Railway bustling westward forms the never-ending top line of a capital "T."

GO to bed on the couch that has, at a porter's magic touch, sprung into existence from nowhere in particular, and sleep. You will run so easily that you will doubt the man who tells you the number of miles per hour you are travelling.

In the morning you will awake and find yourself in Canada. Not the Canada, you have been visiting this past three weeks; not the Canada of tall smokestacks belching bellowing blackness; of broad, straight streets and ten-storied stores—but the Canada you have read about, dreamt about; the Canada that your youthful imaginings people with hooked-nosed red men in the wholesale scalp business. Straight young trees all crimson and gold trembling in their gaudiness; lush grasslands sloping to little white-frothed torrents. Great rugged kopjes with firs atop and a hundred varieties of vegetation softening the harsh outlines of their bases. Hollows and hills and thick, clustering copses. Here a rushing rapid and there a big placid stretch of lake with little wooded isles and tree-grown shores.

Your fancy will people the waste as the train flashes westward. Here, by the side of this dancing, darting, whirling, rock-fretted current might well have lived and loved the dusky Minnehaha. Stealing through this little wood,into which the train plunges for a minute and then throws backward might easily have come Hiawatha, himself. You get a momentary glimpse of a squirrel, a comical furry streak that flies at the train's approach.

"DO not shoot me, Hiawatha," you murmur unconsciously. All day long you will travel with your unopened book on your knees reading the great story of nature in the ever-changing pictures of Manitou Himself. 0 the joy of it! that first day's ride westward.

Stand on the observation platform and watch the track drawn from under you; watch trees and stones and hills and lakes fly backward and disappear at each fresh turn of the road. Watch the horizon of the greak lake, watch the purple-blue islands, and the daintily scalloped bays, and the rivers splashing over tiny Niagaras in their haste to join this fresh-water sea. Feel the keen autumn air and catch the glorious scent of the pines and you will not nave lived in vain.

Day will follow day. Portage, lake, river, road, hill, river, township, lake, portage, wood, lake—so they will follow end on end. No two rivers quite the same. Some choked with a thousand jumbled logs, some clear and still, and black with the shadows of overhanging trees. Some racing and roariag between rocks that show up like the blackened fangs of some submerged leviathan. No two towns; no two hills, or woods, or clearings; each characteristic of its peculiar self. Nature broke the mould of each wild thing she shaped. The eye does not weary nor the mental palate clog of this over-loveliness.

THE country is one great flat expanse, patchily wooded and decorously watered—how sedately the streams roll hereabouts! Then, before the flatness becomes monotonous or the wheat-bearing qualities of the black-turned earth can be fully explained by the Yankee drummer in the smoking room, the train runs through the outskirts of a township, which proves to be a town, which, as solid stone buildings spring across the line of vision, and electric tramway-cars pause in their wild flight to let us pass, proves to be the city of Winnipeg, the Chicago of Canada.

Canada is proud of Winnipeg—although not quite so proud as Winnipeg is of itself. There is a mild jealousy between towns in the East. When they wish to be very nasty they speak slightingly of the hustling qualities of each other.

"But," says Toronto—"But," says Quebec—"But," say Montreal, Ottawa, Hamilton, London, and Windsor—"if you want to see a Real Live Typical Canadian city, a city that will Open your Eyes and make you Marvel, go to Winnipeg!"

And that is just what Winnipeg is. It is very real. It is very much alive—except on Sundays, when it atones in tiptoeing silence for its youthful indiscretions—and it is very typical of this young nation of Canada. It is the new Canada, the Canada of to-morrow.

MONTCALM and Wolfe, Quebec and the Heights of Abraham, the historical richness of the East are things apart. Tbe East stood for civilisation; now it stands for settled orderliness. Not that the West is any the less law-abiding than the East. But it is so boundless, so vast, so illimitable, so wondrously potential that the older provinces of the Dominion, cramped by routine, narrowed by invariable system, and made small in Western eyes by the knowledge of their limitations, are regarded as but appendants to the West. And Winnipeg is the key of the West, the heart of it, the barometer of its prosperity.

In Winnipeg you get no chance of showering encomiums on the city. The baggage man who takes your traps from the depot gives you a précis of the history of Winnipeg, the elevator-boy contrives between the first and the fourth floors to inculcate a knowledge of the relative importance of Winnipeg and the rest of Canada, The chambermaid, depositing clean towels in your room, lingers at the door to deliver a disquisition on the Rise and Growth of Winnipeg, with some Remarks on Its Remarkable Future. The polite clerk who registers you, the imposing barber who removes the three-day stubble from your chin, the bell-boy who brings you distressing cablegrams from headquarters, all contribute their quota to your education, and the head waiter, as he arranges your serviette before you, leans over the back of your chair and asks in a respectful whisper. "What do you think of Winnipeg?"

Mr. Edgar Wallace, special correspondent of the London Daily Mail, wrote from Tangier on June 20th last:—

THAT excellent and amiable young man, Moulai el Aziz, is probably at this very moment opening packing-cases at his palace in Fez quite unconscious of the steel wedge of civilisation that has been thrust into the hitherto impenetrable casing of his Empire—a wedge that, so far, has not misplaced or strained in the slightest degree the fabric that it will one day splinter and tear and destroy.

I sometimes wonder whether Moulai cares overmuch; whether he would not welcome, even at the risk of his throne and life, the Europeanising of Morocco, and would not exchange his precarious magnificence for a guaranteed security and a more modest state.

Imagine, if you can, the Czar of All the Russias casting envious eyes on the Principality of Monaco, and you may gauge the state of mind of Sultan Moulai at the moment.

There are two views of the Sultan of Morocco, and both are correct. There is one which sees a prodigal, a vain spendthrift, an, irresponsible dilettante, and the wrecker of his country, There is another which shows a modest, good-hearted, sympathetic soul, with European tendencies. As I say, both views are about correct.

IT is difficult to hit upon an expression that exactly describes him. The brutal Anglo-Saxon phrase that conveys the best expression of his Majesty, is, to my mind rather disrespectful.

The Sultan is "a young fool."

Every father in the world who has to put his hand into his pocket to pay his son's bills; every man who has had a younger brother constantly getting into a row; every head of every school in the world will recognise the type, and will oblige me by passing on to people who are not so well-informed the exact shade of significance my description has.

The Sultan has no great vices: indeed, for an Oriental be is singularly healthy-minded. The stable has a greater attraction for him than the seraglio—that is one of the grievances Morocco has against him—and he is not bloodthirsty; indeed, I do not think that even in his folly he is a weak man.

The greatest of his sins from the European standpoint is his reckless extravagance. He is a sort of Jubilee Juggins. He has got the spending habit in its most acute and worst form. He throws away money on the most paltry excuses, and will cheerfully spend a thousand pounds, when to spend a shilling would be rank folly.

AN English catalogue came to his hand one day. Idly turning the leaves, he came upon the illustration of a gold watch. Beneath the cut was a detailed jewelled-in-seven-holes-and-lever-escapement description, which showed, as it was intended to show, that the man who had gone through life without possessing watch No. XZ 98, had lived in vain, and that without that watch life was a dreary, sorrowful vale of colorless days and breathless nights.

"I want this watch," said the Sultan, almost ashamed for the moment that he had been so long unpossessed of this masterpiece.

The Grand Vizier bowed. "How many shall I order for your Majesty?" he asked.

The Sultan thought for a moment.

"Seventy-six," he said. It was the first number that came Into his head.

Mouths afterwards a great packing-case arrived at the palace.

"Your Majesty's watches have arrived," explained an official.

"Watches? What watches?" asked Moulai in astonishment.

"Your Majesty ordered seventy six."

The Sultan yawned. "Did I?" he asked carelessly. "Well, I suppose you would like two?"

The obsequious official prostrated himself in ecstasies of delight.

"And you, and you," said the Sultan, indicating various members of his court.

Of course they would, and so the watches passed round the court, and never one of these marvellous time pieces did the Sultan retain for himself.

He has a garage, in which stand twenty automobiles. Except within tho limited area of his palace there exists no road in Morocco fit even for a cycle.

He possesses scores of aluminium cycles, which the slightest obstacle crumbles like paper. He has a gold- and diamond-studded camera which cost him £2000. He takes four snapshots a month, and has a store of photographic paper valued at £400.

HE has lumbered up his palace with tawdriness and drained his exchequer to buy a hundred specimens of the one thing in the world he does not require. He has outworn the patience of his European friends by a hundred childish whimseys, and has alienated the sympathy and loyalty of his subjects by aping those English qualities which Englishmen least admire. Think of him riding out in public in the pink coat and white stock of the hunt. Think of his looking-glass bedstead, his musical boxes, his mechanical toys, his cameras and gramophones, and the never-ceasing procession of packing.cases arriving from Europe brimming with trumpery gew-gaws, the contents of which may keep his interest aroused for ten minutes, but certainly no longer.

What of his army and what of his people?

His army is an untrained, undrilled, lawless rabble. And he is to a great extent responsible. He might, now, have had a force at his. back that would have kept him secure upon his throne. Regiments have been raised, equipped, and drilled by English-officers. Then, without warning, they have been disbanded, the horses sold, the equipment disposed of below cost. Why? The Government needed money. Moulai el Aziz needed money—money for air-guns, and ping-pong tables, and motor cars and mechanical toys.

His people despise him, as why should they not? He has outraged all conventions—and Mussulman convention is Mussulman law—by introducing into Morocco customs and modes of living utterly at variance with the Eastern idea. Had he been a stronger man, had he been better advised, he might have earned the hatred of the Moors of to-day and the gratitude of posterity. He might have outraged convention by initiating reforms that would have been of lasting benefit to his country.

HE might have made both Europe and Morocco his debtors, and held off for another hundred years the danger of foreign occupation. But as it is, he has no friends. His follies have isolated him. It way be politic to save him his throne. It may be necessary—it will be necessary—to protect him, not less against himself than against his people, but outside the help that policy dictates there is nothing for the young Sultan of Morocco and his unwise counsellors but that variety of mild contempt that one reserves for wilful children.

The change that is coming to his fortunes is coming quickly enough. The revolution that is to set Morocco ablaze from end to end is all but kindled. This time it will not be a case of an ambitious pretender seeking adherents to a personal cause. It will be the people against Moulai. The Sultan alone seems unconscious of the impending disaster. He does not know—he of all people — hat Morocco is unanimous in its intention to strip him of his authority.

That Morocco will succeed in its designs upon the Sultan is only possible should Moulai remain in Fez. It is urged that whatever happens he must remain in that city, for to surrender Fez is to surrender the throne.

Sentimentally this is, of course, true, but for the young monarch to remain in his present position is for him to court calamity. "Who holds Fez holds Morocco," the saying goes, but a live Sultan under the guns of the Powers in Tangier is better than a very dead Sultan in Fez.

Moulai has now one chance. He may come to Tangier and place himself under the protection of the French Minister, a course, that he will, I have not doubt, adopt. He will lose Fez; the whole of the interior of Morocco will take up arms against him, and the country will have to be systematically and vigorously subdued, one might even say reconquered—but all this is inevitable under any circumstances. He will save his throne, which is a consideration for Europe, and he will save his head, which is a greater consideration—for him.

On June 17th, Mr Edgar Wallace wrote to tho London Daily Mall from Tanglers as follows:—

IF you look out of your bedroom window to the left, you will see the hills of Andulusia, quite close at hand. And Andalusia is Spain, and Spain is quite European, and almost civilised.

If you turn your head ever so slightly to the right, you will see at your feet, Tangier, which is Darkest Africa and the Mysterious East all rolled into one. Also, it is the first or second century—or, rather. It is before the Christian era.

Mohammedanism is almost a modernity. Tho electric light flickering feebly at the corners of dark passages may pass for a miracle. The hotels are improved caravanseries, and need not count.

Perhaps it is the food, or the methods, or the rooms, but whatever it is, there is nothing in the average Tangier hotel that clashes with that prevailing spirit of antiquity which is Tangier's very own.

Low hills, all olive-green, circle the blue bay. A thin golden ribbon of beach separates the blue and olive of land and water, and, perched uncomfortably at an angle of 30 degrees, Tangier, all of a jumble, sits with her feet in the sea.

Tier on tier, flat roof of flaring orange overlooking flat roof of washed-out blue, a white, bright, yellowy Jerusalem of a town, it rises—Tangier ancient, unchangeable, insanitary.

IT is Eastern; the East one reads about in one's callow youth; the turbancd East; the East in jellab and fez; the East that carries spears and quaint, long-barrelled, queer-stocked guns; the East that says its prayers on Liberty carpets, and goes to the mosque at all sorts ot inconvenient hours.

Laden donkeys stagger through the cobble-paved passages that serve for streets. Coal-black negroes, all thews and perspiration jog past you with tinkling bell and bulging, dripping woter-bag Grave Jews in black, shavon-headed hillsmen all in rags, curious visitors from Fez—you know the curiosity that is expressed by a scowl—and slovenly soldiery in soiled tunics pass and repass you every second. Blanketted ghosts of women, their faces muffled, shuffle awkwardly from street to street.

A bored little boy leads a hideously blinded old man to a group of idlers in the thronged marketplace. The old man whines his formula, and the little boy, with his eyes fixed on a troupe of acrobats, repeats the appeal mechanically.

"In the name of God, who will buy me a little oil for my supper?"

"... for my supper?" pipes the boy abstractedly.

But the bogging bowl goes unfilled.

A lisping objurgation in Spanish from one. "Go away can#t you?" in English from anothe; only a Moor stops in his stiide to search a capacious leather bag at his side, and throws five centimes into the outstretched hands. "In the name of God"

A BABEL of voices around you, In this same marketplace. Arabic mostly, then Spanish, then French, and somotimes English.

"Say!"

An American "jacky," as bright as a baby's smile and as incongruous a vision in this out-of-the-world spot as an automobile in heaven.

"Say! Where'ss this English post-office?

He has a little group of Arab boys about him. Open-mouthed, abashed little boys filled with the wonder and awe of youth for mankind in uniform.

Little Raisuli riding fiery Arab sticks and armed with deadly accurate bamboo canes, slung at their backs with strings of cotton, cease their maraudings, and the blubbering infantle Perdicaris seizes the opportunity of making his escape.

Debonair and happy-go-lucky, with a a smile on his wind-bitten face, the man who has come to stop Raisuli's greater game passes, down the ill-paved streets, followed, by the awe-stricken youth of Tangier.

"Ingles?" asks, villager from Fahs of the seller of charcoal.

"Americo," answers that wise gossip, and spits reflectively.

I think that this is the only dark spot on—Raisuli's otherwise irreproachable reputation; the only point on which Tangier—the real Tangier that lives on fried fish in rancid oil—is not prepared to see eye to eye with the popular hero of the moment.

Tangier is beginning to think that perhaps Raisuli was a little indiscreet in his selection of a victim. It was, says Tangier, sitting cross-legged on a greasy divan, with its shoes left at the door, it was very foolish to take the Americans. Had it been only an Englishman....

IF the truth bo told, there was a time when Tangier did not hold this doubt of Raisuli's wisdom, when it chuckled mightily over the brigand's exploit, and voted that gentleman what is Arabic for 'the limit.' But the joke of the thing had scarcely taken definite shape before all the warships in the world came chasing into the bay.

And all the warships in the world flew a flag that has absolutely no right to be within 3000 miles of Tangier.

These lean white ships came to anchor and sent men ashore— ships postmen and chief petty officers mostly—who spoke the English language with a White Star accent. Then news filtered through to the bazaars and to the stuffy cafés. It came from various sources. From Moors that waited at table at the hotels; from outdoor servants at the Legations; from Moors who knew Spaniards who know everything; from donkoy-boys and boatmen, and even beggars.

And the news was to this effect Perdicarls, who was stolon from Tangier, was an American; the ships that were crowding up the bay were American also—except the one stove-polished vessel that had suddenly appeared from nowhere, and that was English—and it seemed that the taking away of Perdicaris had annoyed and agitated the United. States of America to a lamentable and quite unjustifiable degree. America has no sense of humor, said Tangier, only, of course, in more Oriental and stately language. Raisuli's joke was not appreciated, and the warships had come fully prepared to work all kinds of mischief to the archltectural glories of Tangier.

AT first Tangier was astonished; then she was pained; then the blind, unreasoning passions of the East—the true East— were aroused. The frantic fear of weak men at the mercy of the strong lay on the souls of Mahomet Ali ben Absolom el Hassen.

The fierce pride of this strange people that has resisted the advance of civilisation for a thousand years, was inflamed, and for a time it looked as though the presence of the American warships was likely to have an effect other than that anticipated.

Chrlstians were stoned—furtively, if you can imagine a furtive stoning. The infidel was insulted in the streets, and one unimportant holy man, a sort of Eastern Dowle, was all for preaching a holy war against. Christianity generally. He raged along the beach half-naked and called us horrible names, but his friends got him away and put him to bed, and in the morning he apologised like a little gentleman. One man—it was on a Mohammedan feast day, and therefore pardonable—discharged his ancient musket at the Baltimore and sat down on the sands waiting for the ship to sink. In fact, in the language of local journalism, "Excitement was running high in Tangier, and all the best people of the town regarded the situation as serious.

But serious situations in Morocco come and go like April rains. The Affaire Perdicaris is quite serious enough; how serious will not be realised until after his release. For then it will be that the Powers will talk with painful plainness to Morocco, and the ships that are lying idle in Tangier Bay will serve a most useful purpose.

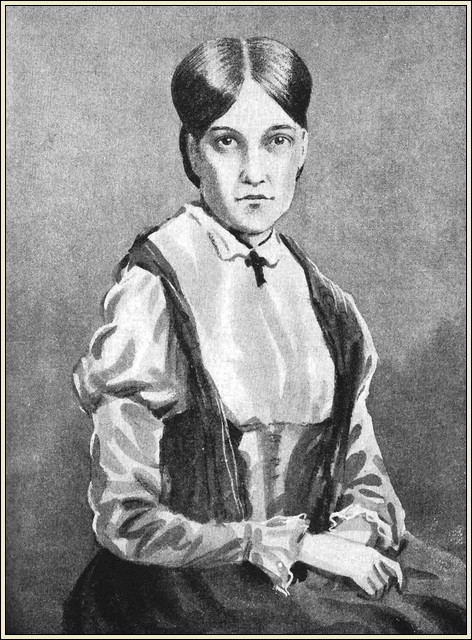

Mr. Edgar Wallace's search for a wife for a British Columbian colonist has had a tragic sequel.

It will be remembered that some months ago, when Mr Wallace was engaged on a series of articles on "The Homeless Poor of London," a description of the life of poor, destitute girls inspired Mr. Cochrane, a young colonial farmer, to apply to Mr Wallace for his offices in choosing a wife from among these homeless ones.

Having secured satisfactory references from the young man, with a certificate as to his good character from the Rev. Mr Duncan, of Salmon Arm, British Columbia, Mr Wallace set about choosing the girl.

The letters of the colonist were published and his needs made known through the columns of the "Daily Mail," and the result was that over six hundred girls expressed their willingness to go out.

"It will be a Robinson Crusoe sort of life," wrote the young colonist, "amid the silence of the tall firs and the everlasting snows of the mountains." Yet, in spite of the lonely life promised, the applicants were numerous; not even the prospect of a log hut for a house and the isolation of their new home deterred them.

From among many applicants one was chosen. Three hundred might have been chosen just as well, so excellent were the qualifications of the girls. A cablegram was sent to the Rev. Mr Duncan asking him whether he would offer a home for the girl until she was married, and to this he Immediately agreed.

A telegram was sent to the girl telling her that the choice had fallen upon her, and in response to Mr. Edgar Wallace's request she called upon him the same night, and was given the money necessary to purchase a few articles for the journey.

By arrangement with the Canadian Pacific Railway, the girl was to have left London to embark on the Lake Manitoba for Canada.

Early the next morning a cable arrived at this office.

COCHRANE DIED SUDDENLY. — DUNCAN.

In this laconic message from the kindly pastor of Salmon Arm is the shattering of the poor girl's hopes. With her scanty trousseau all ready for embarkation within a few days of her romantic wedding, the lover she had never seen, tbe husband she had never met; dies suddenly in all the loneliness of the Rockies, and the silence of the tall firs, as he himself described it.

— Dally Mail.

OF late the cables have had a good deal to say about Morocco and the trouble brewing there. Particular interest attaches to Tangier, since the German Emperor visited it, and in view of the future possibilities a description of the place'at the time of the Kaiser's visit will interest all our readers.

There, is a great stretch of bay, dotted by in numerable boats (writes Edgar Wallace in the "Daily Mail"), a jumble of gleaming white houses rising tier on tier, distant stretches of rugged blue hills, tall minarets of green-tiled mosques, and a long ribbon of yellow beach to mark where land and water meet.

Months ago, before ever the name of Germany was connected in any way with Morocco, the people who gathered in Moorish cafés, drinking mint tea and smoking vile hasheesh, speculated on the coming of someone who would "free" Morocco.

These people spoke the name of Moulal Aziz and spat, called him openly Moulal the foolish, Moulai the Christian, Moulal the unprintable; and they burnt fires on the hills about and gathered in their hundreds, by tribes, to hear the story of how Moulai had sold Morocco to France.

There is little wonder, therefore, in their enthusiasm at the Kaiser's advent, remembering always the sedulous efforts of the German agents to implant in the Oriental mind a picture of Wilhelm the Liberator.

It is not difficult to understand why the unofficial Spaniard has accorded such hearty welcome to the German War Lord. The Spaniard easily predominates in Tangier, outnumbering English and French combined by 12 to 1.

Spanish is the language of Tangier, next to Arabic, and there is scarcely a Moor who does not speak the dialect of Andalusia.

The Spaniards regard Tangier as theirs by right,of commercial conquest; a French occupation would necessarily be more distasteful than English.

The ex-War Minister lives in a little palace that stands high on the sea-front, looking towards the blue mountains of Spain.

I went to see him once (says Mr. Wallace). A pleasant, refined Moorish gentleman with laughing eyes and hands that were more expressive than speech. It was a pleasant experience to find a War Minister who treated me with considerable deferencnce. A very discreet man, Menhembi, and a brother Briton, being, in fact, Sir "Somebody" Meuhembi, 'K.C.M.Q. He is never tired of telling about that investiture.

"I am a British subject," he smiles quietly, as though enjoying the recollection. "I admire British methods of colonising; how can I do otherwise? I have seen Egypt. One day I hope to see India; they tell me that is more wonderful still."

The Sultan made Menhembi a British subject in reward for his services! Later the Sultan desired to confiscate his properly and arrest Menhembi, and found, to his cost, that while having a War Minister who is a British subject had many .advantages, it had its compensating drawbacks, for no sooner did the Sultan's Mahala surrouud the palace of Menhembi than a British cruiser came streaking across from Gibraltar, and wanted to know what all the trouble was about. That is why Menhembi smiles when he says he is a British subject.

He must have been a curious, sort ot War Minister, for he, is covered with battle scars.

Though Tangier threw itself open to receive the Kaiser, though cannons boomed and drums beat, and all Morocco bowed down to the great War Lord, yet one place was closed to him. Perhaps the Moors are the strictest of all Mahommedan sects; no Christian dog, be he king or peasant, can profane the sanctuaries of Islam in Morocco. The mosques of Tangier are closed to all but the faithful.

In the light of the opinions expressed in this article, it is not difficult to understand why the inhabitants of Morocco object to the proposal of the French Government to open a highway between Tangier and Fez. The landing of the French engineers to construct a harbor at Tangier may lead to serious trouble.

(By Edgar Wallace, in the London Evening News)

TAKE one dead man. One man done to death violently. One man whose soul has been wrenched from his body without a second of grace.

Outstretched on the frozen ground, with a bitter wind whirling the show-dust over the tense, still face, he lies, that once was a breathing, thinking man. Hands half-clenched, defy the flying clouds, and the eyes that stare, but do not see, look wonderingly upwards.

Take this one man, this fragment, this smallest and least considerable pawn in the great game, multiply him by fifty thousand, twist him, as the grotesqueness of your fancy dictates, into ten thousand horrid shapes; embellish your awful picture with the unprintable details of battles—remembering always that the bullet does not always kill cleanly, and that bursting shrapnel and one-pound automatic guns create a havoc that can only be imagined by people who have served on coroner's juries—and you have formed in your mind something like the battlefield of Mukden.

WHERE the victorious army has passed, where the retreating army has retired, panicky and demoralised, with ducking of heads and affrightened glances over shoulders, when men have whimpered arnd sobbed in their rage and rear, the dormant fears of childhood responding to the knowledge of the death behind; where men running for cover have suddenly squealed like frightened horses, and tumbled over and over like rabbits, on this deserted battlefield there lies the silence of the grave.

The Things that lie so still seem part of the white earth on which they lie, be closely cuddled to the earth they are.

There is fighting yet, for the horizon is ablaze, and the guhr-r-r-r-r of rifle fire comes borne on the cold north wind.

It will be hours yet before the will-o'-the-wisp lanterns of the search parties come flickering over the plain, separating the quick from the dead, composing these poor limbs, digging great, trenches, and clearing away in the darkness of the night the awful work of day.

BEFORE they come, the lantern men with their bamboo stretchers, the birds will have arrived. For the birds will drop out of the sky, and stand in a contemplative circle, waiting.

Great, beastly birds, with sleek, black coats and beady eyes. They will wait, for they are patient, till quivering limbs are still, till every sign of life has departed, before they do their work.

They will wait days, if needs be, but their wait will be almost fruitless, for long before carrion can take on courage the burying regiments will have cleared the ground, leaving only the horses and the dumb beasts who have fallen victims to the disputes of men.

I WAS at home to receive George. I was in the garden wandering somewhat abstractedly up and down when they came to me and told me that George had arrived.

Soon after, I was invited in to meet him. He was tremendously agitated, and was shouting his orders at the top of his voice.

It struck me that he was making himself very much at home—after all, it was my house; not that he cared: he scarcely noticed me; in fact, I don't think he even nodded.

There is something radically wrong with England; the fine old courteous manners, the stately bows, the artistic salute of other days are forgotten, and so, far from giving me any of his society, George seemed to sleep all the time during the first four days of his visit. This sounds very much like exaggeration, but I can produce witnesses.

All that I heard of him was his grumbling, indignant, what-the-dickens-next voice raised at meal-times—he took his food in his own room—a practice of which I most certainly do not usually approve.

George—his name is really Bryan something-or-other, but I call him George after a favourite cabman—is rather a reticent chap and his manners are not particularly good. But for certain expectations that we have, I do not know that I should tolerate his presence in my house.

For instance, when I met him a few ?days after he came I did my best to be polite and make him feel at home. "How do you do?" I asked, with grave courtesy. But George favoured me with a prolonged stare as though he had never met me before in his life, and yawned undisguisedly.

"Are you enjoying your stay?" I asked desperately; for however rude one's guests may be, there is really no reason why one should imitate their vices—even hospitality has its limits.

George turned his head abruptly away and pretended to be engrossed in the landscape.

HE has been under my roof now for over a month, and I have

scarcely got a civil word out of him. It is very hard to be

snubbed unmercifully in one's own house, and by one who is

practically a perfect stranger. I find his visit all the more

trying because we have so few tastes in common. George has a

practice of turning night into day, and the noise of his

Bacchanalian revels at 2 a.m. rouse me to something akin to

fury.

For I am helpless. He neither cares for what I threaten nor pays the slightest attention to my entreaties. He treats me with marked coolness, and once—the indignity of it!—put out his hand and touched me as if to satisfy his mind upon the question whether I was really alive or if I went by machinery.

ANOTHER two months has passed: George is still here. I wonder

whether he expects us to support him permanently? I have

discovered one or two quite human traits in him. He is possessed,

I find, of an inordinate vanity. He will, if he be encouraged,

spend hours before his looking-glass, murmuring appreciatively

the while.

It is, as I once pointed out to him, an extremely primitive form of amusement, and I offered to take him out on to the links to see Charles Hands play golf, which is, I should imagine, something particularly funny and entertaining. My advance met with so little response that it has not been repeated.

I am becoming almost reconciled to his stay, the more so since he is evincing of late a desire to be on good terms with myself, and has thrown out one or two tentative smiles in my direction, which have been remarkably gratifying.

After all, it is much more pleasant to be on good terms with one's relatives—and especially relatives from whom one has great expectations—than to hear them constantly grumbling and finding fault.

I SUPPOSE he will stay the year now. I must confess he

improves on acquaintance, and for some remarkable reason he is

tremendously popular with the womenfolk of the house. He has

dropped a good many of his mannerisms: that affected you-have-the-advantage-of-me stare of his has given place to a more human

and more kindly expression. Then, again, he is much more

tractable, and will listen without interrupting.

"If I may be permitted to say so," I said to him the other day, "you're improving, George."

George accepted the familiarity with a suggestion of his old hauteur, but said nothing.

"Of course, I couldn't very well be rude to a chap who was practically my guest—even though he was a relation, and—"

I looked around to find George going through his daily gymnastic course. He had not asked me whether I objected—I do not know anybody more off-handed than George—but had started off on Exercise I.

Exercise I.—Lie flat on the back, raise both arms and twirl them in eccentric circles, at the same time shooting out the legs as though swimming.

GEORGE has decided to stay the year—in fact, the year is

more than up, and he has arranged to have the room next to mine.

This would have been, impossible a year ago owing to the late

hours he kept and to his extraordinary leaning to rowdiness. Now,

however, thanks to the country air, early hours, and the good

clean moral atmosphere of my home, he has become almost a

reformed character. We have long conversations, rather one-sided,

since George is only just picking up the English language. In his

own tongue he is remarkably fluent, and makes himself understood

to everybody except me. He has got a remarkably sweet smile, and

when I see that smile I look around to see what he has broken

—for he is still very eccentric.

He is of a literary turn of mind, and simply devours the newspapers if he can get hold of them. He is shrewd, too, with just that touch of low cunning that marks the successful financier.

The other day he pulled my watch from my pocket, and bit it to see if it was good. Of course, it was quite an unconventional way of testing a timepiece, and several jewellers to whom I related the instance say that they have never heard of such a method being employed, but, after all, one bites sovereigns.

He is annoyed less frequently than he used to be; he does not raise his voice so often, and sometimes when he is detected going back to his former evil practices he gives an embarrassed laugh which indicates very clearly that he is by no means proud of his uproarious past.

I HAVE asked George to stay on and make his home

with me. We have agreed to let bygones be bygones, and to say

nothing of his somewhat cavalier treatment of the master of the

house. After all, we all have our failings, and although George

has not shod all his weaknesses—yet he is becoming more

sociable, and is not above taking a word of advice from his well-wishers. I for one have got so used to meeting him, so used to

his peculiar ways, that I should miss him if he left us—so

I am content to go on sitting by his cot, whistling absurd music-hall tunes and watching with a certain pleasure his frantic

attempts to stand "all alone."

BEFORE the door of a frowsy café that opens on to the Plaza—that plaza that has seen no change for a hundred years—I sit in the sunshine and drink coffee.

Partly because coffee is a more natural drink for a Britisher than Amontillado—at ten in the morning.

To-day is Conference day. If you did not know this, the shoeblack who haunts the café would tell you, and the polite porter of the Algeciras Club would give confirmation.

Cobble-paved streets rattle as the first carriage passes unevenly. A grave old man with a snowy flowing board and black-rimmed glasses is talking earnestly to his vis-à-vis. Probably they are discussing the weather or the latest accident to the Russian Minister's dog. At the street corner half-a-dozen French journalists raise their hats politely, and . the old gentleman as politely acknowledges:

HERE comes carriage number two. Filled with white-robed Moors, who do not talk to one another, but take stock of the houses, the people, and the -life of the street.

Then following on come carriages three and four. In the first of these sits a man by himself. A dapper, good-natured, keen-eyed gentleman with curly hair and that indescribable suggestion of tolerant surprise that distinguishes the Englishman whether he be diplomat or tourist. Sir Arthur Nicolson goes to the Conference unsupported by any technical adviser—he knows all that is to be known about Morocco. Then the Americans. White, grey-haired and soldierly; Gummere, a strong, simple man hiding his kindly nature behind a cynical smile.

And so they come, diplomat after diplomat, and the wheels of their hired carriages beat an endless tattoo.

For some we have a respectful bow—even the Englishman who never lifts his hat short of the National Anthem will give the most ornate of flourishes to the two Frenchmen as they pass. One is sad with the sadness of over-much learning—that is Reveil: the other looks like a happy father, and is ever ready to smile—that is Regnault.

Of some as they pass we exchange a flippant word. Such and such is a hopeless muddler, such and such does not care a snap of his fingers whether the Conference succeeds or fails, so long as he can get back to the capital he graces so well. This man is without finesse: that without discretion; and it is whispered that that one—no, not the man on the right, but the other—you will see him as the carriage turns the corner—is altogether too impossible for words.

So you perceive as I perceive sitting here in the sun and sipping coffee, that the Conference is a very human assembly, by no means to be regarded with awe. A number of people you could pat on the back and call "old chap" without inviting the thunderbolts of heaven.

Let them pass. In an hour they will be back with their portefeuilles tucked under their arms. They will go back to lunch at the Reina Cristina, and we shall see them sitting at little round tables—each nation at its own table, each table solemnly flying a tiny national ensign.

AND sitting here in the sun, with an importunate but unavailing beggar whining monotonously at my elbow, I wonder what Jean Prideaux, the tinsmith at Bayonne, is doing just now, and Pierre Riaut, who makes shoes in, Arreau, in the valley of the Pyrenees, and young René Imatz, of Bigorre, and that good Jules Pourtet. who is carpenter, tailor, and wheelwright in Argelès. René was to have been married in March; Pierre is doing rather well, and is contemplating a change to Bordeaux.

I think of these as the pleasant old gentlemen rumble past; I am still thinking of them as Tattenbach, hard-faced, Bismarckian of head, and, to my sentimental eyes, remorseless, goes on his way; and suddenly there comes an uneasiness to my mind that almost amounts to terror. Do our well-dressed, well-fed friends give a thought to Pierre and Jules and René?

It would be terrible to believe that they do not. For the first time I wish they were less human and possessed of omniscient qualities and preternatural reason.

For suppose the Conference fails?

Suppose those noble gentlemen decide that there is no possibility of reconciling those two nations—what then?

They will—our friends of the Conference—go back to their homes with something like a sigh of relief. They will scatter across Europe like schoolboys released from irksome tasks. Back they go to their little embassies, their little villas, to their clubs and departments and chancelleries—and Algeciras will go back to its sloth and its dirt and its dullness.

Et après?

PERHAPS a war—only perhaps; but still, perhaps. Not a war, my military friends, in a country specially created by God for war.

Not a war in n waste, with league-long hills to hold and dongas to hide in, and fronts a mile apart.

But war in a civilised country. War in little village streets, war that means blue smoke curling over trim flower gardens, and dead men lying limply among crushed roses.

War that will call Pierre from his last, and Jean Prideaux from his shop, and young René from poor little Suzanne, and will hurry, them, and thousands such as them, to a quick death and a hastily-dug trench of a grave.

War in a country through which you have motored, dead men at the inn whereat you drank, and the wreckage of war strewn about those same white roads on which the car ran so smoothly.....

They are coming back now, those ambassadors, smiling and talking, and bowing to you and me....

The Conference is adjourned for four days.... The President must go to Madrid on Saturday to meet the King of Portugal.... An attaché has just told me that he will be glad when the rotten thing is over....

But I think—I must break off here, for a man has come down to tell me the latest funny story about the Russian minister's dog.

Madrid, March 29, 1906

THERE is in Spain a tall, slim, sallow youth with a perpetual smile. It is the frank smile of undisguised delight at the joy of living and finding things out. For him life is a birthday, with thousands of presents still unopened. His smile—were I less respectful I might call it a delighted grin, for such it is in very truth—is for the joy of discovery.

I SAW him standing up in his carriage once at Burgos, responding to the hoarse "vivas" of the country folk. He might have saluted gravely, taken his seat solemnly, and driven away in the pomp and circumstance of his rank—that would have been kingly. But he kept to his feet with that amused smile which is chuckle suppressed, and waved his hand cheerily. He waved it to the ladies crowding the balconies, to the children perilously perched on unsuitable elevations, to the swart-faced peasants wrapped in their shawls.

And the love of his people, the people who had watched the fatherless boy grow towards manhood, was his first discovery. Then he discovered other good things, riding and the joy of the hunt, and the delight of travel; and he went on smiling.

Then he discovered that, given the nerve, a man might drive a car over a straight road at 100 kilometres an hour and that was nearly the greatest discovery of all. Coincidentally with this, the Spanish people, who did not share his enthusiasm for rounding dangerous corners at full speed, remarked mildly, but with that mordant humour which is characteristic of the race, that there was no heir to the throne.

They say of Alfonso XIII. that he was the best-ruled child in the world, and if this be so, to-day he vindicates the Latin proverb, which may be found in the appendices of most oheap dictionaries, and which is to the effect that the best-ruled is the best ruler. So that when it came to choosing a wife, and when before him were arrayed the dozen or so of uninteresting but eligible princesses of royal blood, Alfonso, who, as an amateur photographer, realises the fallibility of re-touched photographs, started forth on a tour of inspection.

THE eligibles of Europe were mostly concentrated in Berlin, but the young man—we may suppose that he carried it off with that smile of his—was politely indefinite, and went outside the list, and chose a lady of England, who had certainly never been included.

Therefore the King has made yet another discovery, and that is the sweetest of all.

All Royal matches are love matches. It is part of our eternal hypocrisy to hail them as such, but here is a match which comes to the hardened cynic as rain following a drought. Here is a real love match, an infatuation that is eminently boyish in its intensity, an eager love-making that would satisfy the most exacting of sentimentalists—notice the King's smile in the photographs—and a match-making so much at first hand that, if the truth be told, it almost estranged the boy King from his mother.

Spain is the home of Catholic majestv. In these days of agnosticism the wave of free thought has passed over Spain and left it untouched; indeed, if anything, it has closed the ranks of Roman Catholicism against the heretical intruder.

The news of the match was received with genuine enthusiasm by the people of Spain. One hears of little else throughout the country; one sees their portraits exhibited in every other shop. Ena of Battenberg entered the hearts of the common people, of the bourgeois, and of the thinking classes—and I say this without gush and without cant.

If the truth be pursued, the match found no favour in the ultra-Catholic circle of the Court. Queen Maria Cristina had hoped that the choice would have fallen upon a princess of Austria of her faith; and the great officers of State, who have for years stood next to the throne and who through the King have ruled Spain, were at one in that opinion.

"A Catholic by birth, the urged, and though they were in the minority yet they formed the minority that rules and has governed Spain for years.

We may, without stretching our imagination, imagine the King smiling this opposition. For this King from the first has had his way in things that count.

THEY tell a story about him, a story of a small boy standing before the portrait of Philip IV., by Velasquez, in the gallery here. He looked long and earnestly at the picture. Then...

"I also will have a chin like that, he said, and set himself to work from dav to day, despite many smacking, to pinch and mould his face to the shape of his ancestor's.

That it was an ugly chin does not matter—it was the chin of Philip, and to-day when I saw the picture by Velasquez I was almost startled by the remarkable likeness between the two monarchs.