THE crime of Herbert Armstrong, M.A., the Welsh solicitor, who murdered his wife by administering arsenic, was especially mean and contemptible. Love affairs entangled his life and flattered his vanity, and it is probable that a hatred of his dull and respectable existence in a tiny village was one of the motives for his terrible deed. This story of Armstrong is told by Mr. Edgar Wallace, who attended the trial, and on behalf of a newspaper syndicate offered the convicted man £5,000 for his confession—an offer which was refused.

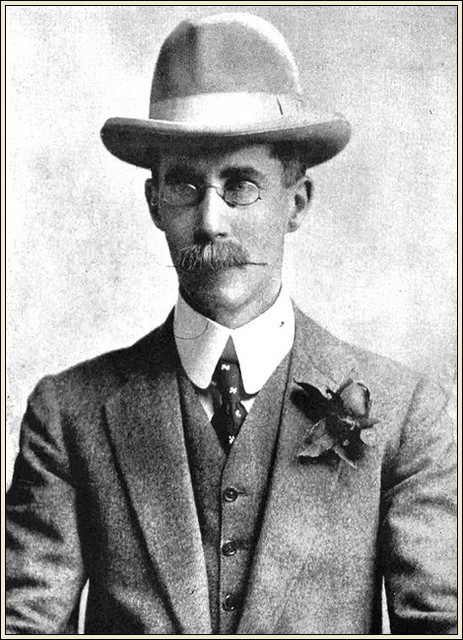

Herbert Armstrong.

THE little village of Cusop, on the borders of Herefordshire and Wales, is not graced by any very distinguished or beautiful buildings, nor hereabouts is the stately lodge entrance of any great country house. Indeed, one of the best of the houses in the village (and this would have been pointed out to you in the year 1920) is a somewhat plain dwelling known as "Mayfield." It is such a residence as you might expect a country gentleman of very limited income would occupy. It had its garden, its pleasant approaches, and, within the somewhat cramped space of "Mayfield," the apartments were more or less ordinary. There was a drawing-room and a boudoir for the lady of the house, a small room designated "the study," where the master might bring his work home in the evening and pursue his investigations into the troubles of his neighbours, without too great an interference by the noise of the piano which his wife loved to strum.

Herbert Rowse Armstrong was a solicitor, and the war, which had drawn this quiet, inoffensive-looking Little man into the service of the Army, at the Armistice delivered him back to the admiring village, and to his colleagues of Hay, a fully-fledged Major, a rank he was loth to renounce. There are photographs extant, and they were at the moment highly prized by their grateful recipients, showing the Major mounted on a horse, a fine figure of a soldier, and finer since his equestrian exercises did not betray his lack of inches.

Major Armstrong had come to the village of Hay from Devonshire, where, at Newton Abbot, he had practised his profession, without securing for himself that success for which his many qualifications seemed to fit him; for he was a Master of Arts of the University of Cambridge, something of an authority upon land tenure. And when, having married a wife, he transferred himself to a new sphere of operations, it did not appear likely that the little village of Hay, off the main track, away from railway and arterial roads, would give him greater opportunities of achieving success than he had enjoyed in the more populous district of Newton Abbot.

There was in Hay at the time an elderly solicitor, whose partner Armstrong became. The elderly solicitor had an elderly wife, and it is a curious fact that, as soon as Armstrong had settled himself down and learnt the ropes of the business, and had become acquainted with the country gentry, his elderly partner should have died with strange suddenness, to be followed in a few days by his wife. The prosecution did not, at the trial which followed, attempt to establish Armstrong's responsibility for the death of his partner. There were very many reasons why the Crown should concentrate upon the charges which were eventually made against him, without risking the negative result which might follow an attempt to prove further crimes against this remarkable man.

Armstrong became a personage of some local importance when he was appointed Clerk to the Justices of Hay, and in this capacity he sat beneath the bench, advising them on points of law, a kindly yet efficient man, somewhat severe on poachers and on those who broke the law in a minor degree. As a solicitor, he appeared from time to time at the various assize courts. The queer little court- house at Hereford knew him; he had sat at the horseshoe-shaped table before judges and had instructed counsel, and, generally speaking, performed the duties peculiar to his profession with judgment and skill.

In appearance he was a short but perfectly proportioned man. He had a small, round head, covered with close-cropped, mouse-coloured hair, was small of hand and foot, and had a countenance which was at once benignant and shrewd. His eyes were blue, set deeply in his head and rather close together. The overhanging brows were shaggy, and his prognathic jaw was hidden by a heavy moustache.

HERBERT ARMSTRONG was well-liked and trusted by everybody with whom he was brought into contact. Cambridge University had given him a finish which made him an acceptable guest at the country houses in the neighbourhood, and although, by reason of his being a stranger, he had the administration of no great family fortune, he nevertheless built up with some rapidity a practice which put him in a position of trust. On behalf of his clients he bought, sold and negotiated for land, had a finger in many sales and local flotations, and was looked upon, not only as a safe man, but as a lawyer with a certain social distinction.

His wife, Kathleen Mary, seems to have been of a somewhat finicking disposition. She had rigid views on social behaviour, exacted from her husband's friends the attention and courtesy which were her right, and exercised, if the truth be told, a mild form of domestic despotism which prohibited her husband smoking in the house except in his own room.

She had her "afternoons," her select dinner parties, and the etiquette which governs a small village was rigorously enforced. A somewhat difficult woman, all the more so because she had a little money of her own, some £2,500, and in all probability refused to her husband those loans which, to men of his character, come so easy to negotiate.

Nevertheless, they were a happy family from the outsiders' point of view. There were three children of the marriage, and neighbours regarded the Armstrongs as united and good-living people. They were regular attendants at the village church; Mr. Armstrong, as he was in the early days, was seldom away from home until the call of war took him to a South Coast town and subsequently to France.

Mrs. Armstrong was a little inclined to melancholia. She was a musician of exceptional ability, and would spend hours at her piano, but there was no suggestion that her despondency was caused by any act of her husband or by her knowledge of his misconduct.

To Armstrong the war may have come in the nature of a pleasant relief. It took him from his restricted activities to a larger and wider world, pregnant with opportunity, to new faces, new interests, and, incidentally, to new ambitions.

It was whilst he was quartered on the South Coast that he met a lady who was subsequently to play a sensational part in his life. Her name, well-known to the Press, has never been divulged publicly, and I do not purpose deviating from the very charitable attitude which the Press of the day adopted. It is no secret, however, that Madame X was a middle-aged lady possessed of much property, and with whom Armstrong became acquainted some time in 1918. He was an attentive friend, and there grew up between these two people a friendship, which seems to have been wholly innocent as far as the lady was concerned. She knew he had a wife "in delicate health," and she formed the impression that his marriage was an unhappy one.

Armstrong's behaviour seems to have been perfectly proper, and the friendship, stimulated by exchanges of letters, developed into a tacit understanding that, if the "delicate health" of Armstrong's wife took a serious turn, the Major, after a decent interval, would appear to claim the fulfilment of a promise which was never actually asked and never given.

Doubtless this little, middle-aged man, with his iron-grey moustache, was a dapper figure in uniform, well likely to raise a flutter in the heart of a lady who had passed her fortieth year. In course of time Armstrong was demobilised, came back to Hay, and plunged into arrears of work, taking up the threads from his assistant, and being welcomed on his first appearance as clerk to the Hay Justices, with many encomiums on his public spirit and courage.

Whatever appearance he might make to those who did not probe too deeply beneath the surface, there is little doubt that Armstrong was something of a profligate in a mean and sordid way. It is not permissible to tell, at this early stage, the evidence which the police unearthed of his amours; but undoubtedly, in the argot of the village, he "carried on," though of this Mrs. Armstrong was ignorant, as also was an elderly lady who lived with the family, a Miss Emily Pearce, who was devoted equally to the husband and the wife, and kept a maternal eye upon the children.

Miss Pearce seems to have been everything from housekeeper to nursery governess. She was the kind of family friend which is almost indistinguishable from an upper servant.

Outside of his work, Armstrong had only one hobby, and that was gardening. Though he employed an odd gardener, he himself supervised the work, and helped mow the lawn, trim the rose bushes, and generally assisted in beautifying his limited estate. He made several purchases of weed-killer, and on two occasions had bought a quantity of arsenic, both in its commercial and its chemical form, for the purpose, as was claimed and as undoubtedly was the fact, of destroying the weeds which flourished exceedingly and had taken a new lease of life since his personal supervision had been removed by the war. There is no suggestion that the weed-killer was employed for any other purpose than that for which it was purchased. Armstrong attacked the enemies of his lawn with great vigour, and gradually brought his garden back to the state in which he had left it.

He found something else on his return from the war. A new solicitor had established himself in Hay, and was taking a fair share of the work which country disputes and land conveyance provide. This Mr. Martin was married to a lady who was the daughter of the local chemist, and Armstrong must have known of his existence before he put his uniform on, but at any rate, when he did know, there was nothing unfriendly in his attitude. Indeed, he seemed anxious to do all that lay in his power to make the path of the new man as smooth as possible, and even went to the trouble of securing for him a commissionership of oaths. In this he was probably not altogether unselfish, for there was no commissioner of oaths nearer than Hereford, and it frequently happened that the remoteness of this official was an embarrassment to Armstrong himself.

Whatever may have been his object (and it is not inconceivable, even in an innocent man, that he should have combined courtesy with profit), the Major was on the most friendly terms with his younger rival, and assisted him to the best of his ability whenever such assistance was needed. In course of time, as was natural, they represented opposing interests, one of which demanded from Armstrong the return of certain monies which had been paid to him on account of property in the sale of which he was interested.

Long before this happened, Armstrong was faced with a domestic crisis. His wife had grown steadily more and more morose. Her interests had become more self-centred. She was infinitely harder to please than she had been, and exaggerated the most petty irritations into events of tremendous importance. Amongst other victims of her rigid code had been the unfortunate Mr. Martin, who had been guilty of the unpardonable solecism of appearing at one of her afternoon parties—in flannels! To call on Mrs. Armstrong in flannels was an offence beyond forgiveness. Martin was blacklisted, and became, from the poipt of view of this woman, whose mind was obviously a little deranged, a social outcast.

SO acute was the form her malady took that Armstrong consulted the family doctor, Dr. Hinks, and it was decided, after taking a second opinion, that this unfortunate lady should be transferred to a lunatic asylum in the neighbourhood "for observation." She was admitted and examined by the medical superintendent, who found her suffering from a mild form of peripheral neuritis. Since it was not a case of mania, and the symptoms were of a more or less elusive kind, she was given a certain measure of freedom, though the doctor at Barnwood Asylum, on the strength of certain delusions and incoherence of speech, had accepted her as insane.

It was on September 22nd, 1920, that Mrs. Armstrong was admitted to this institution, where she remained for four months. During the period of her detention she wrote a number of very sane and clearly expressed letters to her husband, in which she begged him to bring her home for the sake of her children. There is little question that to Mrs. Armstrong the children were a first consideration.

Armstrong paid several visits to Barnwood, and, finding her health had improved visibly, after Christmas he took steps to have her removed to his house. She returned on January 25th, 1921, so much improved in health that both Armstrong and the family doctor were delighted—at least, Armstrong "displayed a great deal of satisfaction."

Evidently this development was not at all in accordance with Armstrong's expectations. Whether the sharp attack of illness which had left her with these delusions, that had subsequently brought her to Barnwood, was the result of poison, is a matter which can never be known with any certitude. In all probability the man had already begun his "experimenting." He had in his study a quarter of a pound of white arsenic, and one may assume that the first illness of Mrs. Armstrong was due to the administration of this deadly poison.

With her return to "Mayfield," his plans underwent a change. She had made a will, leaving practically everything to himself, and revoking an earlier will which made such a distribution of her property that he would benefit to a very small extent. He was in some financial difficulty, but the determining factor in his action was Mrs. Armstrong's "difficulty." He was weary of her, her primness, her rigid sense of propriety, her faculty for making enemies.

Herbert Armstrong, in short, had grown sick and tired of excessive respectability—and in his hatred of his cramped and too well-ordered life you may well find the primary motive for his terrible crime. It is extremely doubtful that the small sum of money, some £2,000, which would pass into his keeping on his wife's death, had anything to do with his determination to get rid of her. This is a view which may be contested; but, as one who followed the case very carefully from its beginning to its tragic finish, that is the conclusion I formed, and that, I believe, is also the view of eminent counsel engaged in the case on either side. His wife had become an incubus, a daily trial to him. He decided upon taking the step which was to lead him to the gallows.

A week or so after her return from Barnwood, Mrs. Armstrong was taken violently ill following a meal. The family doctor was called in, and prescribed certain medicine. Mrs. Armstrong was put to bed, a nurse was engaged, and she made a fairly good recovery. There was no suspicion in the mind of the doctor that his patient was suffering from arsenical poisoning. He thought that it was a return of her old trouble, and treated her for peripheral neuritis, being strengthened in his diagnosis by the recovery which she made.

She was hardly well before a second attack followed. Armstrong received from his magisterial colleagues the sympathy to which he was entitled, and one of his friends sent him up some bottles of champagne. This fact did not emerge at the trial, but it is possible that the agent through which Mrs. Armstrong received the dose of arsenic which ended fatally was champagne. Probably Armstrong himself opened the bottle and gave his wife a glass. Unfortunately, at the trial this point was never cleared up, by reason of the fact that there was not one of the principal witnesses for the Crown who could clearly remember who opened the bottle and who gave its contents to this wretched woman. And so there was no reference to champagne at all in the evidence which was taken at the Hereford Assize Court.

This is a curious fact: that Armstrong was convicted without any proof being put in that he administered with his own hands, food or drink of any description whatsoever; and there were many, cognisant of all the facts, who believed that this would be a fatal bar to a conviction, and the foundation of the optimism which was shown by the defence is also to be found in this curious circumstance. Armstrong was eventually convicted, not because he was proved to have given his wife poison, but because he had accessibility and the opportunity for so administering it. But for the haziness of witness's memories, on this point, the conviction of the Major would have been a foregone conclusion.

On the night before her death, when she was weak and exhausted as the result of arsenic administered to her a day or two days previously, Armstrong gave to his wife a glass of champagne in which he had dropped five or six grains of this tasteless and colourless alkaloid. She drank the wine, being refreshed by the draught, and although she was weak, talked sanely and rationally of her illness and of the house and its management. In the middle of the night Dr. Hinks was sent for, and arrived to find her in extremis. She died on the morning of February 22nd, 1921, and the doctor certified that she had succumbed to natural causes.

The sympathy of the village and the countryside went out to this lonely man, left with three small children; the funeral was attended by every local notability, and the distress of the bereaved widower at the graveside was commented upon.

Armstrong, in his quiet, self-repressive way, bore himself manfully.

"In many ways I am glad that her sufferings are over," he told a friend. "The best and truest wife has gone to the Great Beyond, and I am left without a partner and without a friend."

HE caused a large tomb-stone to be erected over the grave, properly and tenderly inscribed, and it was placed in such a position that every Sunday morning, when he and his motherless children went up to the church, they passed the white stone. Through the summer and the autumn that followed, a tribute of flowers lay upon the sepulchre of the murdered woman. He himself took the choicest roses to adorn the grave.

He was, he said, so run down by the tragedy that he sought leave of absence and went abroad, having communicatcd with Madame X that the trials of his sick wife were at a merciful end.

Armstrong's itinerary was a curious one, for he not only visited Italy, but took a trip to Malta, for no especial reason except that he had always been interested in that romantic island.

On his return to "Mayfield," Madame X was invited to stay with him, and there is a possibility that the advent of the lady who was a potential Mrs. Armstrong caused a little heartburning in certain quarters. Others may have considered that they had a prior right to the fascinating Herbert Armstrong.

Armstrong docs not appear to have wasted very much of the money which came to him from his wife's estate. That money was practically intact at the moment of his arrest. But he does seem to have drawn very heavily upon funds which were entrusted to him to complete certain purchases of land. There arose a triangular correspondence between himself, Martin the solicitor, and a land agent living in Hereford. Perhaps "triangular" is hardly the word, in so far as it implies that Martin was concerned with the Hereford land agent. But certainly the negotiations which should have been completed hung fire, and there came from Martin a peremptory demand, on behalf of his client, that the money deposited should be returned. What was the cause of dispute between Martin and the land agent at Hereford has not transpired. After a visit to Hay and on his return to Hereford, the land agent died very suddenly.

One day Martin met Major Armstrong in the village, and reminded him that he had not received a satisfactory reply to a letter he had sent concerning the money and the property which was the cause of the dispute concerning them. Armstrong smiled; he had a quick, inscrutable smile that lit his face for a second and died as instantly, leaving him expressionless.

"I think," he said, "there is a great deal too much letter-writing between us, and the best thing you can do is to come up to tea with me and we will talk the matter over."

Mr. Martin, probably remembering the coldness of his reception when first he put his foot across the threshold of "Mayfield," demurred to this suggestion, but eventually agreed. That afternoon he went up to "Mayfield," was most graciously received by Armstrong, who led him to the drawing-room, where a tea-table had been laid. There was a cake-basket, one of those wicker affairs which carry three tiers of cakes and bread and butter, and, in this particular case, a plate of buttered scones. The tea was poured out, Armstrong handed a cup to his visitor, and chatted pleasantly, and a little ruefully, of his failure to meet the demands of his legal friend, and then:

"Excuse fingers," said Armstrong, and handed a wedge of hot buttered scone to his guest.

That scone had been sprinkled with the tasteless white powder which had removed Mrs. Armstrong from the world.

Martin ate it to the last crumb, drank his tea, and, after a more or less satisfactory talk, walked back to Hay, where he lived with his wife.

It was not until he was taking his dinner that night that he began to feel ill, and then so alarming were the symptoms that he was put immediately to bed and Dr. Hinks was summoned.

Whatever Dr. Hinks's views were about this sickness, so strangely resembling that which had preceded Mrs. Armstrong's death, Martin's father-in-law, Davis the chemist, held a very decided opinion. It was part of his duty as a pharmaceutical chemist to understand, not only the properties, but the actions of various poisons, and to know also something about their antidotes. His son- in-law's sickness was obviously caused by arsenic. He immediately conveyed his suspicions to Dr. Hinks, and that practitioner accepted that possibility, an attitude which undoubtedly saved Martin's life.

It is impossible for a leading man in a tiny village like Hay to be taken seriously ill without the news becoming public property; and when, a few days after Martin, very white and shaky, had made a public appearance, he met Armstrong, the Major was intensely sympathetic.

"You must have eaten something which disagreed with you," he said (very truly), "and I have a feeling that you will have another illness very similar."

Martin probably registered a silent vow that if he could help it that second illness should not occur. He, with Dr. Hinks, had sent a certain fluid to London for analysis, and when the analyst's report came, showing a considerable trace of arsenic, Scotland Yard was notified.

In the meantime there was another curious happening. Mr. and Mrs. Martin received one day a box of chocolates, and, upon eating one, Mrs. Martin was taken ill. The fact that these chocolates, which contained arsenic, could not be traced to Armstrong, resulted in that aspect of the man's villainous activities being dropped at the trial.

ARMSTRONG was growing desperate. He made another futile attempt to induce Martin to pay a further visit, and, when that failed, asked him up to his office for tea, an invitation which was declined.

The mentality of such people as Major Armstrong is puzzling, even to the expert psychologist. One supposes that they are mad, that they are paranoiac in the sense that they have to an excessive degree the delusion of their own infallibility. Certainly Armstrong must have realised, from the repeated refusals of Martin to deal with him, that he was under suspicion; and a normally minded man, even though he were not a Master of Arts and a clever lawyer, even if he had not the assistance of a large experience in criminal cases, would have taken immediate steps to remove every trace of his guilt and to cover himself against the contingency of exposure. Armstrong went about his work in the usual way; he was to be found in his place when the local court assembled, exchanging smiles with the presiding justices, who knew nothing whatever of the suspicion under which their clerk lay, and assisting them to deal with the peccadilloes of local wrongdoers. He was corresponding with Madame X, and at the same time was conducting an illicit love affair, of which evidence was plentiful in the village of Cusop.

Scotland Yard, having all the facts in its possession, including the statement made by Dr. Hinks as to the symptoms of Mrs. Armstrong, was necessarily compelled to act with the greatest circumspection and caution. The man under suspicion was not only a lawyer, who would be conversant with every move in the criminal game, but he held a high position. It was impossible, in this tiny village, to conduct such an inquiry as would have been set on foot supposing the suspected man were living in London. Even the advent of two strange men in the village would have set tongues wagging, and Armstrong would have been warned that all was not well; whilst, if those strangers were reported to be inquiring about his movements, then the task of bringing him to justice was rendered all the more difficult.

The officer in charge of the case was favoured by the fact that the nights were long and dark. He and his assistant were in the habit of arriving at Hay by motor-car long after the shops had closed and the people had dispersed to their several homes, pursuing their inquiries in secrecy and returning towards midnight to their headquarters at Hereford. Martin was seen and cross-examined, a statement taken of his visit to "Mayfield" and the subsequent attempts of Armstrong to induce him to make a further call: the chemist who supplied the arsenic displayed his books; Dr. Hinks showed his case-book and gave particulars of Mrs. Armstrong's illness; whilst one of the nurses who had looked after that unfortunate lady up to her death was also interviewed, under a pledge of secrecy.

On New Year's Eve, 1921, the police were in possession of sufficient evidence to justify an arrest, not on a charge of murder, but for the attempted murder of Martin. The Home Office had been consulted, and permission to exhume the body of Mrs. Armstrong had been tentatively given, to be followed later by the actual order which only the Home Office authorities can issue, and which was, in fact, issued once Armstrong was under lock and key.

When he reached his office, that morning, he was followed into the room by the two detectives in charge of the case. He must have realised, as the cross- examination grew closer and closer to Martin's illness, that he was more than under suspicion, but he did not by any sign betray either his guilt or his apprehension. He did, however, volunteer to make a written statement, and was left alone to prepare this, an opportunity which he could have put to good use if he had remembered that in his pocket, amongst a number of old papers, was a small package containing three grains of arsenic—a fatal dose!

But he was so confident in his own ability to hoodwink the police, so satisfied that, occupying the position he did, no charge could be brought against him without his receiving sufficient warning, that he never dreamt that the open arrest would be followed by a closer one. The normal course that would have been taken, had he been under suspicion, was for an application to be made to the local justices for his arrest, and it is certain that he banked upon receiving this warning, never dreaming that Scotland Yard would move independently of the justices, and that the first intimation he would receive would be the arrival of the detectives with a warrant granted by superior authority.

He was dumbfounded to learn from the inspector in charge (Crutchley) that he must consider himself in custody on a charge of attempting to murder Martin by the administration of arsenic.

"But you cannot do that," he protested. "The charge is preposterous. Where is your warrant?"

The warrant was shown to him, and the discovery that it had been issued some days previously must have come to him like the knell of doom.

He was conducted to the local lock-up, which he had so often visited and to which he had been instrumental in consigning so many petty breakers of the law, and there he was searched, and the tell-tale packet of arsenic found in his pocket. This act of indiscretion on his part had been little short of madness. He must have carried the arsenic in the hope of Martin accepting one of those invitations which he had so frequently issued, never dreaming that this damning proof of his villainy would go far to hang him.

"What is this. Major Armstrong?" asked the inspector sternly.

"That is arsenic." Armstrong's voice was cool, his nerve unshaken.

"Why do you carry this arsenic in your pocket?"

"I use it to kill the dandelions on my lawn," he said, and elaborated this story later.

From the little cell he heard the church bells of Hay ring in the dawn of a New Year through which it was fated that he should not live. In the morning he again appeared in the court he knew so well, but this time a stranger sat at the clerk's place, and the bewildered justices, in sorrow and consternation, gazed upon their friend standing in the dock, wearing his British-warm overcoat and smiling affably at the friends whom he recognised in the court.

The position was an incredible one. The first few moments in that tiny court- house were poignant in their tragedy. Armstrong was committed on remand to Gloucester Prison. Again he was brought up, formal evidence given, and again he was remanded. In the meantime the police and the Home Office authorities had exhumed the body of Mrs. Armstrong, and in a near-by cottage Sir Bernard Spilsbury, the Home Office authority, performed his gruesome task, removing the portions of the body which were to be sent to the Government analyst.

Armstrong came up before the court one morning to learn that there was a second charge against him, namely, that he did feloniously murder Kathleen Mary Armstrong by administering arsenic on or about the 21st day of February, 1921.

THE court proceedings, and those at the coroner's inquest which followed, will always be remembered by the journalists who were present. The court was so tiny, and the incursion of reporters so great, that the most extraordinary methods were employed to cope with the situation. Tables were extemporised from coffin-boards, and upon these the representatives of the great London dailies wrote their accounts of the proceedings.

It so happened that at the time of the preliminary inquiry, the Assize Court was in session, and it seemed that the man would be compelled to wait for six months before he was brought to the bar of justice. But Mr. Justice Darling announced that he would hold a special assize for the trial of Armstrong, and this was formally opened on April 3rd, after the man had been committed on both charges: that of the attempted murder of Martin, and of killing his wife.

Armstrong's attitude throughout the preliminary inquiries had been taciturn and confident. He had followed every scrap of the evidence with the keenest interest, but had said little or nothing, and I think was the most confident man in the court when he was finally committed for trial, and knew that he was leaving the neighbourhood in which he had lorded it so long, and where he had lived for so many years in the odour of sanctity and the approval of his fellows.

His vanity supported him, as it has done with so many poisoners—for men who destroy life in this dreadful manner are so satisfied that no evidence other than that which they might offer themselves can be of value in securing a conviction, that they are certain up to the very last that they can escape the consequences of their ill-doing. There has never been, in the history of poisoners, a single instance of a man confessing his guilt.

Such was the public interest in the trial, and so serious a view did the law authorities take of this case, that the Attorney-General, Sir Ernest Pollock, now Master of the Rolls, was sent down to conduct the prosecution, the defence being in the hands of Sir Edward Curtis Bennett, a brilliant advocate who had conducted the prosecution of all the spies caught in England during the war.

On a cold day, with snow blowing through the open windows of the court, Herbert Rowse Armstrong stepped lightly into the dock and bowed to the thin- faced man in the judge's box. He was as neatly dressed as ever—brown shoes, with fawn-coloured spats, brown suit and brown tie perfectly harmonised. He had been brought over by motor-car from Gloucester Gaol that morning, had interviewed his counsel, and now, with an assurance which allowed him to glance round the crowded court-house and nod to his friends, he listened to the cold, dispassionate statement of his crimes.

He was in a familiar setting: he knew most of the court attendants by sight or name; in happier circumstances he had exchanged views and words with the Clerk of the Assizes; the Under-Sheriff was known to him personally; he had even appeared to instruct counsel before the judge who was now to conduct the trial. He sat back in his chair, his arms folded, a motionless and intent figure, following the evidence of every witness, the blue eyes seldom leaving their faces. Even at that hour he was satisfied that the evidence which could be produced would be insufficient to secure a conviction, either for murder or attempted murder, and he expressed to the warders, who had to bring him every day the long journey from Gloucester, his faith that the case for the Crown was so ill-constructed that the trial could not but end in his acquittal.

"If this case were tried in Scotland," he told them, "there could be no question that 'Not proven' would be the verdict." Sir Ernest Pollock put the case fairly and humanely against him, and it was not until Armstrong himself went into the box that the full weight of the law's remorseless effort began to tell against him. In the witness-box Armstrong was a suave, easily smiling and courteous gentleman. His soft, drawling voice, his easy manner, his very frankness, told in his favour; nor did the cross-examination of the Attorney- General greatly shake the good impression he made. But there was a man on the bench wise in the ways of murderers, who saw the flaws in Armstrong's defence. When Mr. Justice Darling folded his arms, and, leaning forward over his desk, asked questions in that soft voice of his, the doom of Herbert Rowse Armstrong was sealed. They were merciless questions, not to be evaded nor to be answered obliquely.

Firm to the very last, Armstrong met the dread sentence of the. court without any evidence of the emotion which must have possessed him, and when the clerk of the court asked, in halting tones:

"What have you to say that the court should not now give you judgment to die according to law?"

Armstrong almost rapped out the word:

"Nothing!"

Though his guilt had been established on evidence which was good and sufficient for the twelve men who tried him, he was not without hope that, on certain misdirections, he would secure a reversal of the verdict at the Court of Appeal. But this court, which exercises its powers of revision very jealously, saw no reason to interfere with the course of the law, and on May 31st, on Derby Day, Armstrong met his fate.

During his period of incarceration in Gloucester Gaol he had occupied the condemned cell, adjoining the execution shed, which is, in fact, a converted cell opening into the apartment where condemned men spend their last weeks of life. The disadvantage of this arrangement is that almost every sound in the death chamber can be heard in the condemned cell, and Armstrong, who knew Gloucester Gaol—knew too the proximity of his cell to the place of his dread end—must have been keyed up to the slightest sound. It was necessary that the executioner should try the trap, whilst Armstrong was at exercise. He arrived, however, too late for this to be done overnight, and it was not till the following morning that the drop was tested.

At seven o'clock Armstrong, who had been up an hour, was invited by the warders to take a final walk in the exercise yard, an experience unique for a man under sentence of death. The sky was blue and cloudless, the morning warm and balmy, and he strolled about in the limited space allotted to him, showing no evidence of the terrible agony which must have been in his soul. After nearly an hour's walk he was conducted back to the condemned cell, where the minister of religion was already waiting, and within a very short time he had paid the penalty for his crime.

The Armstrong murder may become historic from the point of view of the lawyer, since he was condemned on evidence which was entirely and completely circumstantial. But, as Sir Ernest Pollock pointed out at the trial, in a poison trial direct evidence is practically impossible.

"In this case," said Sir Ernest, "we know that Mrs. Armstrong died from arsenical poisoning. This body of evidence which will be called before you will be directed piece by piece, circumstance by circumstance, pointing to a conclusion that it was the prisoner at the bar who killed his wife.

"She died from arsenical poisoning. Who had the means, who had the opportunity in August and in February, who had the motive to administer the poison?

"You find the means with the prisoner. You find the opportunity—the one man who was at 'Mayfield' both in August and in February. You find the motive in the will referred to."

Though there was no proof of the administration of poison, and the evidence of motive, as far as Mrs. Armstrong's fortune was concerned, was perhaps the weakest that has ever been put against any man on the capital charge, nevertheless, nobody who knew him, and who was brought into close touch with his life, will doubt that Armstrong was guilty.

Before Ellis pulled the bolt, the slight figure standing on the drop said something that was indistinguishable. One present thought that it was a confession of guilt—more likely it was a last protest of innocence.

Armstrong had refused an offer of £5,000 which I had made to him a few days before for a complete confession of his crime.