Towards the end of the Boer War the bcdy of a woman was discovered on Yarmouth Sands. She had been strangled by a mohair bootlace. A laundry mark, a silver chain, and a tintype photograph provided the clues which eventually brought Herbert Bennett, the woman's husband, to justice for a mean and cruel murder.

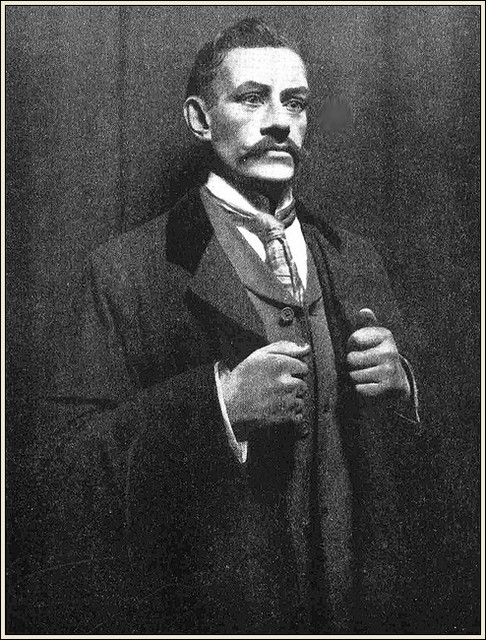

Herbert Bennett

THE murders committed by criminals who have been classified by criminologists as "Class D. Larcenists" make up a very large percentage. It is possible, if one sits in a magistrate's court throughout the year, to collect a list of names which will be almost certain to produce at least one murderer in the course of a generation.

A criminal of this type, however, now and then escapes conviction. He may be wanted by the police, but the chastening experience of prison life, which might possibly bring about a reformation, has been denied to him. He has behind him an embezzlement or two of a petty kind; he has probably been associated with two or three shady methods of obtaining money by false pretences; and to these offences may often be added affairs of gallantry, and, if not a bigamous marriage, at least one marriage and wife desertion.

There is no more dangerous criminal than a small larcenist who has escaped the consequence of his offences, through, as he believes, his own dexterity and skill. Having this good opinion of himself, he progresses from crime to crime, until there comes a moment when he finds no other escape from the consequences of his meanness and folly than the destruction of a human life which, as he believes, stands between himself and freedom. And so confident is he in his own genius for evasion that he will plan the most diabolical of crimes, perfectly satisfied in his mind that the success which has attended the commission of minor offences will not desert his efforts to evade the penalty of his supreme villainy.

And the meaner the larcenist, the meaner the criminal, the meaner the murder. The greater criminals, the Deemings and the Chapmans, killed on the grand scale. The crimes of such small men as Herbert John Bennett, some time a labourer at Woolwich Arsenal, are attended by those evidences of low cunning which enabled them to twist a way of escape out of their minor crimes, but which were utterly inadequate to protect them when the more complicated machinery of the law was set in movement, and the brightest brains of Scotland Yard were concentrated against them.

BENNETT was a man possessed of a smattering of education he received at one of the elementary schools, and he had, moreover, even as a boy, an ambition to shine in a higher stratum of society than that in which circumstances had placed him. Such an ambition is commendable enough, and has brought many a man from the gutter to the highest positions in the land—always providing that the climber has less regard for appearance than for the solid substance of his advancement.

Bennett, by no means intellectual, wished to appear rather than to be; and at the age of sixteen he set himself the task of supplying the deficiencies of his education. He had a mind for dancing, and considered the possibility of being able to play the piano with such skill that he might gain for himself an entry to doors that were now closed to him.

His gropings toward gentility brought him into contact with a young girl, whom he must have regarded as his social superior, since she had many of the attainments which he lacked, and was not only something of a musician, but sufficiently proficient to give lessons on the piano. He was seventeen, she was two years older, and he displayed toward her a devotion which was as passionate as it was ephemeral. Young as he was, he could talk impressively. He left her head reeling with magnificent prospects; the scope of his ambition left her breathless; and when he proposed, as eventually he did, she accepted him. Bennett, despite his youth, was a tempestuous lover.

"He had very big ideas for one of his station. Sometimes he would talk so grandly that even the people who knew him best believed that he was on the point of receiving some exceptionally good appointment, or was about to inherit enormous sums of money." He had had his smaller adventures, and fate and an excursion ticket had once carried him to his first view of the sea—at Yarmouth.

At his then impressionable age, Yarmouth became the first and only seaside place where happiness was to be found. The Cockney's devotion to his first love in this respect is proverbial, and there is little doubt that Yarmouth was, for Bennett, an enchanted beach ever after, just as Hastings is to the writer, and Brighton to so many hundreds.

The marriage to the music teacher was a hurried affair. They appeared one morning before a London registrar, and were made man and wife.

With marriage came dispointed illusionment for the girl. The great schemes began to dissipate into thin air. The fine appointment, which would have secured them "a detached house and garden, and possibly some poultry at the back," did not happen. Bennett made his living by a succession of little jobs, none of which he retained for any time. He was a grocer's assistant, a sort of shop-walker; odds and ends of jobs came his way; his leaving was more or less hurried, and where there was money to be handled, was accompanied by a suspicion, amounting in one or two cases to a certainty, that, in his yearnings for gentility, Bennett had cast overboard the principle that holds a man to honesty.

He became a canvasser, selling sewing-machines, and his plausibility and qualities of salesmanship earned him good commission. There was some suggestion that not all the orders were genuine, and a possibility that he sold some machines outright and collected the money for them without accounting to his employers.

Mrs. Bennett had an aged grandmother, with whom the couple were living. She had a small allowance, sufficient to keep her, if not in comfort, at least beyond the fear of want. Her possessions were few, but amongst them was a long silver chain and a very old-fashioned watch, in which she took great pride, and to which she attached such importance, though it was in truth a very clumsy piece of jewellery, that she made one of those informal, word-of-mouth wills, so common to people of her class, by saying, "When I am gone, this is yours, my dear."

Eventually she died, and the chain passed to the girl. By that time she was not greatly interested in chains or watches, and even the death of her grandmother brought no very great increase to a burden which was already more than she could bear.

The passionate youth she had married had developed into a bullying, hectoring young man, who never ceased to find fault, who cursed her openly and privately for ruining his life, and who did not hesitate to beat her. A child had been born of the marriage, and while it was coming she had been subjected to every kind of indignity and ill-treatment.

So Bennett moved from job to job. His limited education restricted his opportunities, and there was the additional handicap that he had often to rely upon characters and references which were obviously forged.

Of much that would be interesting about this period to the criminologist, there is no trace. It is certain that Bennett was engaged in some nefarious business, for he was changing cheques for large sums, and had suddenly changed his name and became Mr. Hood. In this name, he and his wife and baby left, somewhat hurriedly, for South Africa; and it is certain that at the time Bennett had sufficient money, not only to pay the fare out and maintain himself in Cape Town, but also to pay the return fare when, after a very short stay in Cape Town, he decided that South Africa offered no opportunities to a man of his ability, and returned.

Relationships between the Bennetts were now strained. The man had grown tired of his early love, told her she was a millstone about his neck, and attributed the passing of his dreams, the non-fulfilment of the bright promises of his youth, to the handicap of having to provide for her.

Their stay in Cape Town was a matter of days. The newness of the life, or, as he described it, the exclusiveness of Colonial society, irritated and frightened him, and they had scarcely settled down in their lodgings before he was back in the Adderley Street shipping office, arranging his passage back to England.

Their return to London was followed by a separation. He had managed to secure work in Woolwich, and, on the plea that the lodgings they had taken at Bexley Heath were too far from his work, he left his wife and came to live at Woolwich, where he posed as a single man, visiting his wife very occasionally, and doling out to her sufficient money to make both ends meet.

They had taken the lodgings at Bexley Heath in his own name, but it was as Hood that he was best known in Woolwich; and here, free from the encumbrance of his wife, he began to pay attentions to an attractive young girl, Alice Meadows.

ONCE more he assumed the role of ambitious young man, with immense prospects, and behind him a fascinating experience, for he could now talk of his foreign travels, could speak almost with authority upon South Africa (at that moment a centre of interest, for the Boer War was in progress), and from his imagination could evolve stories of adventure, very fascinating to a young girl who had spent most of her life within the confines of London.

It is clear that Bennett was not depending entirely upon the wages he earned at the Arsenal. He had some other source of revenue, and the probability is that he ran one of his get-rich-quick schemes as a side-line.

In the summer of 1900, soon after Miss Meadows and he had become acquainted, and he had met the Meadows family (impressing them as a young man of singular attainments), the question of a summer holiday was mooted, and what was more natural than that the first place which occurred to him as a likely spot was Yarmouth? At any rate, he wrote to a landlady in the place, asking her if she could reserve rooms for himself and his fiancée. The landlady, if she remembered him at all, was not aware that he was married.

In any case, she had no accommodation at the moment, and accordingly he reserved rooms at a little hotel, and went down with his fiancée, travelling first class, and spent a week in that delightful pleasure resort. They occupied separate rooms; he was a model of decorum; and those who noticed the rather undistinguished couple observed him as an attentive, considerate young man, who could not do enough for his companion.

The holiday seems to have been of a fairly innocent character. It gave them, however, an opportunity of discussing their future and of fixing the date of their wedding. Bennett, as usual, had great schemes which were on the verge of fruition, and the prospect must indeed have been a very brilliant one to Alice Meadows, who listened, open-mouthed, to the many inventions of her lover, learnt that he was well connected and expected in a very short time to inherit a fine property. Dazzled by his convincing lies, she made preparations to leave the place where she was employed as a domestic servant, and, with the assistance of her family, began to get together the clothes and dainty fripperies which are the especial possessions of a bride.

"A nicely behaved couple—I often saw them strolling along the South Beach," said an observer. "They were a model of what engaged people should be."

But alas for poor Alice Meadows! Her dreams were soon to dissipate into thin air; the growing treasures of clothing she was collecting were never to be worn for his pleasure; and the grand future, so far as he was concerned, was to end dismally on a gallows in Norwich Jail.

IT is the failing of all men who worship their own reputations, that they must be thought well of at any costs by the person who, for the moment, fills their eye. You may turn the leaves of criminal history and find this queer, perverted vanity showing in every other line. It of was the same with Deeming, with Chapman, with Dougal, with Crippen; it is difficult to find a case of murder where this distorted ego does not stand out in the criminal's psychology.

I can recall only three cases, a notable example of which was Smith, the brides-in-the-bath murderer, where this bloated sense of self-importance did not permeate the story of his supreme offence. There is no reason in the world why Bennett should not have married the girl, committing bigamy and risking the consequence of his misdemeanour. There was no reason why Crippen should not have run away with Miss Le Neve, or why Deeming should not have left his wife and children to the charity of his relations. But this passion for making a new start, for wiping out, as they believe, all that is past in one terrible act of savagery, as expressed in sixty percent of murder cases, was too strong for Herbert Bennett. In his muddled brain there was only one way of establishing himself as a single man and justifying all the lies he had told, and that was by removing the woman who stood between him and a new life.

Probably he also found, at this stage, that the drag upon his financial resources which this double life of his involved was reaching the breaking point. He had spent money on holidays, he had given Alice Meadows an engagement ring, and there came from his wife at Bexley Heath a request for a seaside holiday, which gave him the idea which was subsequently carried into effect.

He very seldom met his wife nowadays. His visits to Bexley Heath were few and far between. Nevertheless, his allowance to her enabled her to live without working too hard. She could afford, for example, to send out a small quantity of her linen to a neighbouring laundry.

Bennett does not seem to have been in any dire straits, or to have called upon his wife for assistance to meet his bills. In the course of their married life he had given her four or five rings, and at no time had she been asked to part with these, so the supposition that he had another source of income than his wages at the Arsenal is strengthened; for obviously it would have been impossible for him to have maintained two homes, and carried on an expensive courtship, on his salary as a labourer.

But the end was in sight, and he determined to rid himself of at least one expense; and when his wife mentioned in her letter a wish for a holiday, he replied promptly, suggesting Yarmouth, and giving her the address of the house where, only a month before, he had applied for lodgings for his fiancée.

On this occasion Mrs. Rudrum (this was the landlady's name) had a vacancy, and in the beginning of September Mrs. Bennett went down to Yarmouth with her child and took up her residence in Mrs. Rudrum's house. At her husband's request, however, she changed her name, and it was as Mrs. Hood that she was known to her landlady and the very few people who knew her by sight.

A reserved woman, who did not readily make friends, she seemed to be completely satisfied with the companionship of her child. The landlady observed: "The only thing that I noticed about her was that she wore a long silver chain around her neck, and had an old-fashioned watch. She was not the kind of woman that you would notice very much. She was very fond of her little girl and had no other thought than to keep her amused and happy."

One day, when she was strolling along the beach, a beach photographer came to her, and by his professional blandishments induced her to pose for a little tintype picture of herself and the child, and she was all the more ready to agree to his proposition because she had no picture of the little one. And so the photograph was taken, and thereafter occupied a place of honour in her tiny bedroom.

Who she was, and where she came from, nobody knew. Apparently no preliminary letter had been written to the landlady, and until she appeared at Mrs. Rudrum's, that lady had no idea she was coming. She was uncommunicative, not inclined to gossip, was typical perhaps of a large number of weekly trippers who visit seaside places, in that she had no identity except as a summer boarder.

Mrs. Rudrum was incurious. She did notice, however, that there arrived one morning a letter contained in a bluish-grey envelope and bearing the postmark of Woolwich. The contents of that letter are unknown: the instructions it contained she carried to her grave. But reconstructing the crime in the light of subsequent knowledge, it may be supposed that Bennett wrote to his wife, telling her that he would meet her on the Saturday night, giving her a rendezvous, and in all probability telling her that there was particular reason why he should not be seen in Yarmouth, and also why she should not divulge the fact that he was arriving at all. It is probable, too, that he told her to burn the letter, or else to bring it with her and give it to him when they met; for it is hardly likely that he would take the risk of so incriminating a document being left about for the landlady to see.

She was used to these furtive methods of his. A decent woman, with a respectable life behind her, would not acquiesce in these constant changes of name unless she knew, or believed, that her man's safety depended upon the deception. It is certain, moreover, that she must have been acquainted with his many curious methods of making money, and that she might therefore be dangerous to him if he deserted her.

Something of her complacence and her confidence is traceable to this knowledge. The landlady did not see the letter again, nor did she notice that it had been destroyed, so it is more likely that Bennett insisted upon his wife bringing the letter with her, in order that he could be sure it would fall into no other hands.

ON the Saturday night she put the child to bed, dressed herself with unusual care, putting on the silver chain and watch, and went out toward the front. She was seen by her landlady walking up and down outside the Town Hall, a building which is very near to the railway station, and it is certain that this was the rendezvous and that she was waiting for the arrival of the train which would bring Bennett from London.

Coming down, as he did, with murder in his heart, and the means of encompassing his wife's death in his pocket, and having taken such extraordinary precautions against being associated with the woman, it is almost staggering, yet typical of the careless workings of the criminal mind, that he should not only have met her before the Town Hall, in one of the busiest parts of Yarmouth, but that he should have taken her to a small inn near the quay, where they drank together, afterwards disappearing in the direction of South Beach.

South Beach at that time was a wild, untended stretch of sand and marram grass, to which courting couples instinctively bent their way. There were innumerable hollows where the swains could be sure of freedom from observation. One such hollow was occupied that night by a man and a girl, who saw two figures come out of the darkness and go into another depression near by. That they were lovers the two observers, very much more interested in themselves than their surroundings, accepted without question.

Bennett, unaware that he had been seen, settled himself down, with his wife at his side, his arm about her, words of love on his lips, and in his hand a mohair boot-lace about nine inches long, with which he intended to commit his hideous crime.

That the deed was done at the very moment when the woman, who still loved him, might expect from him nothing but tenderness, was proved when her body was found. The lovers near by heard a woman's voice pleading for mercy, but thought that they were skylarking and took no further notice. While he kissed his wife, Bennett had twisted the lace about her neck, drawn it tight and fastened it with a reef knot. She must have died within a few minutes, whilst he pressed the struggling figure deeper into the sand.

At midnight he appeared at the hotel, where he had stayed only a week or so before with Alice Meadows.

His manner was nervous and excited. He told the hotel porter that he had come down by the last train, and that he must leave by the first train out of Yarmouth in the morning. There was no appearance of a struggle; beyond a little agitation and his trembling hands when he took a drink, there was little remarkable in his appearance, and the porter very promptly forgot the incident of the unexpected visitor, called him in the morning in time to catch the seven o'clock train, and thereafter the matter went out of his mind, the more so, as he thought of Bennett as a young man newly-engaged and who was, as Bennett had told him on his visit, about to be married to a very charming girl.

SO far, we know the story of the murder. We are acquainted not only with the identity but the character of the murderer. We know the circumstances which led Mrs. Bennett to adopt the name of Hood, and why she came to Yarmouth. We have to consider now the problem which confronted the police force when, on the Sunday morning, it was reported by an early morning bather that the dead body of a woman was lying in the sands of South Beach, a mohair lace tied tightly about her neck. Yarmouth was still full of visitors, strangers to the town. It had its quota of undesirables, male and female. The police knew that the South Beach was infested, at certain hours of the night, with queer people, also strangers to the town. When the body was removed to the mortuary, and a brief examination had been made by local and county detectives, there was nothing to reveal who she was, where she had come from, what were the circumstances attending her death.

Their first view was that she was some unfortunate creature who had been maltreated by a chance acquaintance, one of those half-mad murderers who skulk all the time, unsuspected, in our midst. That was the view persisted in for a long time after the jury had returned a verdict.

The first rift in the cloud of anonymity came when Mrs. Rudrum, who had learnt of the murder from a neighbour, and who knew that her lodger had not returned all night, came down to the police station and made her report. She was shown the body, and instantly identified her as Mrs. Hood. Could the landlady tell the police whether any of her jewellery was missing? The rings were still upon the woman's hands, but the silver chain and the watch had gone.

"What silver chain was that?" asked the chief detective.

Mrs. Rudrum tried inadequately to describe the trinket, and then remembered that in the dead woman's room was the little photograph that had been taken on the beach. Accompanied by police officers, she went back to the house, and a very thorough search was made of the room. The photograph was taken away, and every drawer ransacked, for by now the police had learnt of the bluish-grey letter with the Woolwich postmark. But of this there was no trace. Nor was there any other document or writing which could throw the least light upon Mrs. Hood's identity, her friends or her place of origin. The landlady knew nothing; her lodger had "kept herself to herself, and told me none of her business."

On some of the linen was a laundry mark—just a number, 599. And with these two most slender clues, a small tintype picture showing, in microscopic proportions, a blurred chain, and the 599 laundry mark, the police began their search. But at every turn they were baffled. That Mrs. Hood had met a man outside the Town Hall, and that she had been seen in a public-house with him, only established the suspicion that the murderer was not a chance-found acquaintance, that the woman had met him by appointment, and that he came from somewhere outside of Yarmouth.

The Woolwich postmark narrowed down the search only in so far that every laundry in Woolwich was visited, the marks books inspected, still without bringing the authorities any nearer to their quarry. From time to time the inquest was adjourned, until, after six weeks, it seemed that the case was at an end, and the jury returned a verdict of "murder against some person or persons unknown."

The photographs were circulated far and wide, but without result for some time. Then, when the search seemed at an end (though such searches are never at an end where the Metropolitan police are concerned), a laundry manageress at Bexley Heath recognised, from the photograph of the laundry mark, the handiwork of her own establishment and, turning up the books, it was discovered that Number 599 had been given to a Mrs. Bennett.

The police were at that time systematically exploring every channel that would identify the laundry mark with the murdered woman, and detectives were instantly on the spot. The house in which Mrs. Bennett had lived was visited and, without hesitation, a woman who knew her identified, not only the photograph, but the chain which she had been wearing.

At Yarmouth she had told Mrs. Rudrum that she was a widow. At Bexley Heath she was known as a married woman, living apart from her husband, and people who lived in the same house remembered that she had frequently received letters which were enclosed in the bluish-grey envelopes that had been described at Yarmouth.

This was only the beginning of the new search. The police might find the sender of the letter, might even discover, as they suspected, that it was the husband of Mrs. Hood, and yet unearth no more than a bereaved man, ignorant of his wife's whereabouts and her fate. The investigations in Woolwich began all over again, and finally Herbert Bennett was discovered at the Arsenal.

Bennett had returned to town, and his first act was to meet Alice Meadows in Hyde Park, and subsequently he gave her a number of things belonging to his wife. These, however, did not include the chain and the watch, which he took from his wife's dead body, or, as is more probable, which she handed to him as they were walking along the beach, or when they sat down in the hollow, being afraid of losing something for which she had a personal affection.

Long before any arrest was made, the detectives conducted an inquiry into Bennett's movements. Having established beyond doubt the fact that he was a married man, the further discovery that he was courting another girl and that she was on the threshold of marriage, strengthened the suspicion that Bennett was responsible for the death of his wife.

The extraordinary rapidity with which the police work on such occasions as these was facilitated by the fact that Bennett had no idea he was under suspicion, although interrogations had been made of Alice Meadows, his friends had been visited and questioned, and Mrs. Bennett's relations had been seen by the police.

During this period Bennett displayed a mild interest in the Yarmouth murder. He had discussed the crime with his wife-to-be and her sister, and had expressed his surprise that the police had not been able to run the murderer to earth. He had even advanced theories as to how the crime was committed and the murderer escaped!

THEN, one day, when he might have thought that the crime had blown over, and that the police were now interested in something more promising, two detectives appeared and asked him to accompany them to the police station, and here, to his amazement and horror, he was charged with the murder of his wife.

Bennett then did what so many men have done to tighten the noose about their necks.

"Yarmouth?" he said indignantly. "Why, I have never been to Yarmouth in my life!"

There are so many parallel instances of similar acts of reckless stupidity that we can pass over his extraordinary folly without comment. Not only had he been at Yarmouth, but the police knew that he had been there with Alice Meadows. She herself made no secret of her innocent holiday; and there was the staff at the hotel at which he had stayed to prove the fact beyond any question of doubt.

How slender are the clues on which a murderer's detection hangs! A chance- taken picture made by a beach photographer; the accidental decision of Mrs. Bennett to wear her chain on that day—she did not wear it every day—was a link so strong that the cleverest advocate of the day, Mr. Marshall Hall, was not able to break it.

Even complete frankness could not have saved Bennett from the scaffold. Had he admitted that he came secretly to see his wife on the night of the murder, and that he left her the next day; if he had admitted his duplicity and the projected act of bigamy; if he had taken the police partly into his confidence; even then that chain which was found in his portmanteau was the most damning proof of his guilt. Without that silver trinket, Bennett could not have been convicted, much less hanged. If, when he found it in his pocket, he had thrown it into the fire, or dropped it into the river, not even his suspicious conduct, his denial of ever having been at Yarmouth, could have brought him to the condemned cell.

But there were the two unchallengeable facts: the silver chain, photographed on the woman two or three days before the murder; the evidence of her landlady that, on the night she went out to meet her husband, she was wearing that chain, and when she was seen outside the Town Hall later in the evening she was still wearing that chain; the absence of the chain from the body when it was discovered; and its finding in his possession—these were the unbreakable chains of proof which he could never shake off. There is an old Spanish saying that every murderer carries in his right hand the proof of his guilt, and never was this proverb so exemplified as in the case of the Yarmouth murder. What malignant imp induced him to take the chain at all, what perversity allowed him to keep it in his possession after the murder was discovered, and long after the description of this trinket had been circulated throughout the kingdom, we cannot tell.

"If the chain had not been found in Bennett's possession," said the greatest criminal authority of the day, "not only would the most striking piece of evidence have been removed from the prosecutor's brief, but there would have actually appeared a point in favour of the prisoner! The disappearance of the chain would have been adduced as a reasonable supposition that Mrs. Bennett had been killed by an unknown lover for the sake of its value."

So strong was popular feeling that, instead of being tried at the Norwich Assizes, Bennett was removed to the Old Bailey, and here, before the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Alverstone, he made his acquaintance with a London jury. Thirty witnesses were called—witnesses who spoke of Bennett's early married life, of his visit to South Africa, of his ill-treatment of his young wife, and his trip to Yarmouth. There was, of course, no evidence as to any act of felony or misdemeanour which procured him large sums of money from time to time, for the English law does not allow such evidence to be taken when a man is on trial for his life.

There were the hotel porter and the manager, who knew him and had looked after him when he was at Yarmouth with his fiancée. There were the people who saw him in the bar of the little inn near the quay. There was the landlady, and, most distressing of all, the girl to whom he was engaged.

To a man of Bennett's temperament, this was the most uncomfortable witness of all. "It was not the murder he had committed but the lies he had told which upset him," said an observer.

Time and time again we have seen a murderer display the most poignant emotion, not at the recital of his crime, but at the appearance in the witness-box of some person whose opinion he valued, and before whom he must now appear in the light of a boaster and liar.

If it is possible for such a man to possess affection which could be truthfully described as genuine, Bennett had found, in this newest of friends, the love of his life. He had been introduced to her family and had impressed them with his genius and his extraordinary knowledge of affairs. A man of perfect manners, he had impressed that least impressionable of persons, his future wife's sister.

When Alice Meadows stepped into the box, Bennett's eyes dropped; it was the only period during the trial that he gave evidence of his discomfort. Lower and lower sank his head as she related, in that unimpassioned atmosphere, the foolish stories he had told of his career, his prospects, his travels.

Bennett's imagination ran riot when his audience was a woman: his gifts of invention were never so marked as in those circumstances. He could listen without flinching to the record of his horrible deed—more horrible than can be related in cold print; he could watch with a detached interest the display of the trinket which he had taken from his wife a few minutes before her death, and could give his complete attention to the doctor's evidence. To Bennett, that was the least of his embarrassment. The real ordeal for him came when Alice Meadows exposed him as a braggart and a liar.

In this Bennett was not exceptional: all who have attended the trials of great criminals have witnessed a similar phenomenon. Armstrong's averted gaze and discomfort when the evidence of Madame X. was being taken, Crippen's agitation when reference was made to his relationship with Miss Le Neve, Seddon's flushed face when the purity of his freemasonry was called into question—one could multiply such instances by a hundred.

Throughout the trial Bennett's behaviour was exemplary.

The trial lasted six days, and at the end the jury required only thirty-five minutes to make up their minds, and, returning to the court, declared Bennett to be guilty of wilful murder. To the very last the man protested his innocence. Even when the judge assumed the black cap he showed neither fear nor any departure from his attitude of a misjudged man.

The sentence of the court was that he should be taken hence, and from thence to Norwich Jail, and that there he should be hanged; and under a strong guard he returned over the familiar route to Norwich—the route he had travelled with Alice Meadow's on the way to their holiday; the route he had followed when he was bound for Yarmouth with a cruel murder plan; now to expiate his crime within a few miles of the cemetery where his murdered wife was lying.

Here, on a chill day in March, he met his fate at the hands of the common hangman. But the memory of Bennett will be perpetuated for many years. His conviction will stand as a model of the efficacy of circumstantial evidence. Here was a case where a man committed a murder, and no weapon of any kind was traceable to him—for the mohair lace with which this unfortunate woman was strangled was not identified with one that had been in his possession at any time. There was undoubtedly a motive, though it might be urged that there was no immediate necessity for doing away with his wife, and that he gained very little by his crime. Even the laundry mark was only useful to the police in locating the woman's ordinary place of residence. It was on the flimsy links of an old-fashioned silver chain that the Crown depended to prove that Bennett was the murderer. And most effectively did they succeed.