THE plausible and sinister adventurer who, for the love of gain and of an easy life, preys upon women, is a familiar figure in the history of crime. Camille Holland was fifty-six when Dougal captured her affections, and the unhappy romance of a rich old maid led to her murder at this infamous scoundrel's hands. The crime might have gone unpunished but for one damning clue. It was a pair of shoes which brought Dougal to the scaffold after the lapse of years.

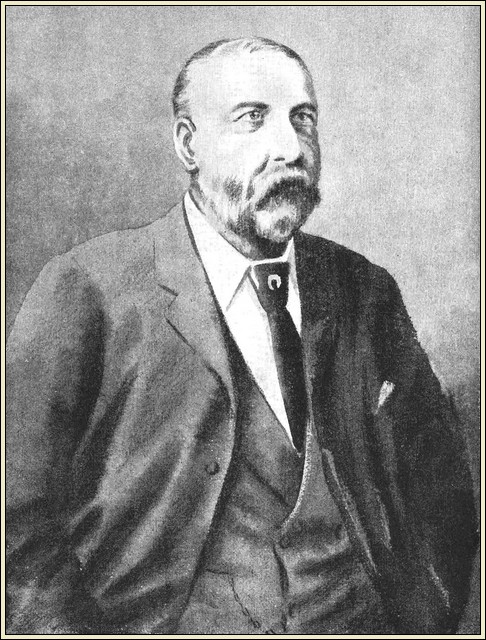

Herbert Samuel Dougal.

AT the age of fifty-six a spinster may well be resigned to an old maid's life. Into the life of Camille Cecille Holland romance had not come, though it was inevitable that she should possess her dreams. For she was a woman of imagination. She scribbled sentimental little stories, and painted in water-colours sentimental little landscapes—mills and ponds and green woodlands—pleasant, pretty scenes.

Camille Holland did not look her years: most people thought she was forty. A certain refinement of face and trimness of figure, an exquisite smallness of foot (her chief pride) lent to her an attractiveness which is unusual in women who have passed through many loveless years, "living in boxes," having no home but the boarding-house and cheap hotels which she frequented, and no human recreation but the vicarious acquaintanceships she formed in her uneventful journeyings.

She could afford an occasional trip to the Continent; she could afford, too, other occasional luxuries, for her aunt, with whom she had lived many years at Highbury, had left her the substantial fortune of £7,000, invested in stocks and shares, which brought her from £300 to £400 a year. Amongst her investments was £400 invested in George Newnes, Limited, which shares were to play an important part in the detection of one of the cruellest crimes of the century.

Living as she did, it was natural that she had few friends. There was a nephew in Dulwich, who saw his aunt occasionally; there was a broker to whom she was known, and a banker on whom she sometimes called. Very few tradesmen knew her, because she ran no accounts, buying in whatever town she happened to be, and paying cash.

IT was in the early days of the Boer War, when military men had acquired the importance which war invariably gives to them, that a smart-looking, bearded man called at the boarding-house in Elgin Crescent, Bayswatcr, where Miss Holland was in residence. He had evidently met Miss Holland, for he sent up a card inscribed "Captain Dougal," and was immediately received by the lady in her hostess's drawing-room. He appeared a great friend; he came again and again, took the lady out for long strolls in Hyde Park, and once they went to dinner and to a theatre together.

The devotion of Captain Dougal must have brought to realisation one of the romantic dreams of this spinster whom love had passed by, and she warmed to his subtle flattery, his courtesy and his obvious admiration. When, in his manly way, he confessed to her that he was unhappily married and there could be no legal culmination to their love, she was shocked, but did not dismiss him. Life was passing swiftly for her, and she was confronted with the alternatives of going down to oblivion starved of love, or accepting from him the ugly substitute for marriage.

There was undoubtedly a great struggle, sleepless nights of heart-searching, before she surrendered the principles to which she had held, and let go her most cherished faiths. But in the end the surrender was complete. One afternoon she met him at Victoria Station, and together they went to a little house at Hassocks, near Brighton, the house having been rented for two months by her imperious lover.

Dougal's earlier marriage, he said, had been a very unhappy one.

"I need not have told you I was married at all," he said. "You would never have discovered the fact. But I cannot and will not deceive you, or treat you so badly as to marry you bigamously."

His scruples, his fairness, his very misfortune, were sufficient to endear him further to this infatuated woman of fifty-six, who for the first time in her life was experiencing the passion about which she had read and heard, and about which, in her mild and ineffective way, she had written. And those first months at Hassocks brought her a joy that fully compensated her for the illegality of the union.

The adventure was at least no novelty to Samuel Herbert Dougal, sometime quartermaster-sergeant of the Royal Engineers. Nor was it the first time that he had described, in his soft Irish tongue and in the most glowing colours, the happiness in store for his victim. His very brogue, so attractive to the ears of women, was an acquisition, for he had been born in the East End of London, a neighbourhood which had grown a little too hot for him at a very early age, and had made him accept the Army as an alternative to prison.

In a very short time he had gained promotion, for he was a remarkable draughtsman, and so clever with his pen that he earned for himself amongst his comrades the name of Jim the Penman. From his earliest days he had preyed on women, for he had been one of those parasitical creatures to whom a sweetheart meant a source of income.

At twenty-four he married, taking his wife with him when his regiment was moved to Halifax, Nova Scotia. She died there, with suspicious suddenness. Pleading that her death had upset him, he was allowed a short furlough in England, and returned with a second wife, a tall, young and good-looking woman, who tended his children and seemed to be possessed of some means of her own, for she had a quantity of jewellery. Nine weeks after arrival, she also was seized with a sudden illness, and, like his first wife, died and was buried within twenty-four hours, the death being due, according to Dougal, to her having eaten poisonous oysters. Under military regulations it was not necessary to register the death in the town of Halifax, and beyond the fact that Dougal seemed to be very unfortunate in the matter of his wives, no notice was taken.

There was in Halifax at the time a girl who had been a friend of both the Mrs. Dougals. Though no marriage ceremony occurred, Dougal, by his very audacity, succeeded in imposing upon his comrades to the extent of their accepting her as his wife, going to the length of forging a marriage certificate, which, however, did not deceive the officer commanding, whose signature was necessary to secure her a free passage to England. This union was a short one, and the man's brutality and callousness were such that she decided to return to Canada.

"What excuse shall I offer my friends?" she asked tearfully. To which he replied, with that cynicism which was part of the man:

"Buy yourself a set of widows' weeds, and tell them that your husband is dead."

Dougal left the Army with twenty-one years' service, the possessor of that good conduct medal which is the scorn of most military men, and some three shillings a day pension—an amazing end to his military career, remembering that during his period of service he served twelve months' imprisonment with hard labour for forging a cheque in the name of Lord Wolseley, Commander-in-Chief of the Forces in Ireland.

Scarcely had the Canadian woman left than another girl was installed in his home, only to flee in the middle of the night from his violence.

He was successively steward of a Conservative club at Stroud Green, manager of a smaller club at the seaside, and held numberless other positions for a short length of time; invariably his terms of employment ended abruptly, and as invariably the cause had to do with his treatment of the women with whom he was brought into contact.

First and foremost Dougal was a forger. He could imitate handwriting with such remarkable fidelity that even those he victimised hesitated to swear to the forgery.

When he met Miss Holland he had lost his youthful slimness; the fair, curling moustache was touched with grey, and he had added the pointed beard which lent him a certain sobriety of appearance that so ill accorded with his character. He was a man versed in the arts and wiles of wooing. The life at Hassocks was a dream of happiness to his dupe, and her own nature and predilections assisted him to the fulfilment of his plans.

There can be little doubt that Dougal was a poisoner; the circumstances attending the deaths of his first and second wife, the callous conduct he displayed in those events, almost prove his responsibility. But many years had elapsed since those tragedies; at least two great poisoning cases had been tried in the courts; and he must have learnt how dangerous it was, in so law- abiding a country as England, to repeat the crimes of Halifax.

Moreover, the death of Miss Holland could not in any way benefit him, since he had no legal claim upon her. There is some slight evidence that he tried to induce her to make a will in his favour, but Miss Holland, despite her infatuation, displayed an unusual acumen when the question of placing her signature to a document arose.

THE life at Hassocks, delightful as it was, was not exactly the kind of life that the woman desired. She did not want to rent a house; she wanted to settle down, to have a permanent home of her own; and Dougal, to whom she expressed her wishes, agreed with her. When she told him that she would like to buy a farm, he instantly became an authority on farming. Nothing would please him better than to live the simple, rustic life; and accordingly they began a search for a suitable habitation, and the columns of the newspapers were carefully perused.

Eventually a suitable property was found. This was Coldham Farm, in the parish of Clavering in Essex, and negotiations were begun with Messrs. Rutter, of Norfolk Street, Strand, for the acquisition of the house and acreage. If the property had a disadvantage, it was that it was remote and lonely, the nearest village being Saffron Walden, and the equivalent to "town" the town of Newport, a quaint and ancient place which all people who motor from London to Newmarket pass through without giving it a further thought.

The price of Coldham Farm was £1,550, and Dougal, who had charge of all the arrangements, settled with Messrs. Rutter that a conveyance should be made in his name. Miss Holland selling off some of her stock in order to secure the money for the purchase. One day she called with Dougal at Norfolk Street, and the necessary documents were placed before her for her signature. Instead of being perfectly satisfied with the arrangements as he had made them, she read through the conveyance with a frown, and shook her head.

"The property is conveyed to you," she said. "I don't like that. It must be conveyed to me."

"It doesn't make any difference; it is only a matter of form," pleaded Dougal, who seemed to have made no secret of their relationship, even to Rutter's clerk.

"If we are to be known as Mr. and Mrs. Dougal, how can you have the conveyance in your maiden name? Everybody will know our secret."

Apparently Miss Holland was superior to the malignant tongues of gossip.

"It must be conveyed in my name," she said stubbornly, and, despite all Dougal's protests, despite his private interview with her, when he must have urged more intimate considerations, she had her way. The conveyance was torn up, a fresh document was prepared, and Coldham Farm was transferred to her.

The pair left Hassocks at the end of January, 1899, and took lodgings at the house of a Mrs. Wiskens in Saffron Walden, where they remained until April 22nd. Mrs. Wiskens, in addition to letting lodgings, was a dressmaker, who had a small clientele, and she added to the income she derived from "lets" by doing odd dressmaking jobs, repairs, etc., incidentally serving Miss Holland in this capacity.

Their life at Saffron Walden seems to have been a pleasant time for Miss Holland. Dougal was still the attentive and devoted "husband," and nobody in that respectable little town dreamt that the formality of a marriage ceremony had been overlooked.

From time to time they drove over to their new home, the purchase of which had not yet been completed, and Dougal simulated a knowledge of farming which must have been very comforting to the woman, who undoubtedly had her suspicions of his ability to conduct even this small establishment.

It was a smallish house, surrounded by a moat, and, to the romantic eye of the aged spinster, possessed many attractions. It was she who decided to rename Coldham Farm, which became the "Moat House Farm," the Post Office being notified of this change.

They moved into Moat House Farm in April, soon after the purchase was completed. The former owner of the farm left behind him a small staff of labourers, cowmen, etc., which Dougal re-engaged for the work of the farm.

Front view of the lonely Moat House Farm.

Dougal purchased a horse and trap, threw himself with vigour into his new work, devised changes, including the filling in of certain parts of the moat; whilst Miss Holland, who did not disguise her pride in her new possession, set about the furnishing of the house, and brought from London a grand piano to beguile the tedium of the long evenings. She was something of a musician, just as she was something of an artist, and she may well have looked forward to a life of serene happiness with the man who had come so strangely into her life, and whose love had changed every aspect of existence. It would have been remarkable if Dougal, after his adventurous career, could be satisfied with the humdrum of farming.

He might be amused and interested for a month or two, but after that the restrictions, which the woman imposed, the necessity for keeping up the pretence of devotion, and the various petty annoyances which her shrewdness produced, must have its effect. Change was vital to him—not necessarily change of scene, but change of interest. No one woman could satisfy him, and he took an unusual interest in the choice of the girl servant that Miss Holland engaged.

This proved to be Florence Havies, who look up her situation three weeks after the Dougals had gone into their new home. On the very morning of her arrival Dougal came into the kitchen, looked at the girl, and, finding her attractive, put his arm around her waist and kissed her. The girl, to whom such attentions were only alarming, complained immediately to her mistress.

It was the first hint that Miss Holland had received of the man's character, and when, trembling with hurt vanity, she demanded an explanation, Dougal tried to laugh the matter away.

"She is only a kid," he smiled; "you surely don't think I was serious?"

Whether he succeeded in allaying the woman's suspicions is not known, but he did not give her time to forget the incident. That night, when Miss Holland was in bed and Dougal was supposed to be in the kitchen downstairs, a terrified scream broke the silence, and Miss Holland, jumping out of bed, made her way to the servant's room, to find her in a condition bordering upon hysteria. After a while the girl was calmed, and told her story. She had been awakened by hearing Dougal at the door demanding admission in an undertone. The door was bolted, but the man had flung his weight against it and was on the point of bursting in when the girl had screamed.

Bewildered, horrified by her discovery, Miss Holland went back to her room, to find Dougal in bed and apparently asleep. She was not deceived however. She charged him with his offence and ordered him from the room, the girl sleeping with her that night.

The scene that followed in the morning, when the man and the outraged woman met, was one of intense bitterness. Throughout breakfast she reproached him—reproaches which he bore with extraordinary meekness. Either he had intended making a breach by his act, or else he had utterly misjudged her complacence. At any rate, he seemed startled by her vehemence and impressed by her sincerity.

It is possible he had never met a woman of her type before, and certainly he was a terrible experience to her. The discovery shocked her, threw her for the moment off her balance and left no definite view but one that the man must go. There was no question of her taking her departure and leaving her property in his hands; she had made it very clear to him, when the conveyance was signed, that she was entirely devoid of that form of quixoticism.

Dougal himself did nothing during that morning except wander disconsolately about the farm. He was seen, with his hands in his pockets, looking thoughtfully at the moat, at one of the half-filled trenches which served to drain the farmyard proper. His attempt to make up the quarrel was the signal for a fresh outburst, until she was so exhausted by the violence of her anger that she sat down on the stairs and, covering her face with her hands, gave herself up to a fit of passionate weeping. Thus Florrie Havies saw Miss Holland and tried to comfort her.

The girl had not been idle. Realising that she could no longer stay in the house with Dougal, she had written to her mother, asking her to come and fetch her the next day; and, as she told her mistress, she was looking forward anxiously to her parent's arrival.

To the girl Miss Holland confided her sorrows and her contrition for the folly which she had been led into committing. At the moment she had no definite plan, except that Dougal must leave the farm and that their relationship must be broken.

Dougal had no illusions on the subject, and throughout the day was facing the prospect of returning to his precarious method of living. All his plans had come undone; the prospect of an easy life had vanished; his scheme for getting the farm into his own hands had failed. He had no hold whatever on the woman except her goodwill, which he had exhausted by his folly.

To a man of his avaricious nature the prospect of losing all hope of handling his "wife's" money was maddening. It is certain that he had already tried to induce her to make a will in his favour, but his failure in this respect would not greatly have troubled him, for an opportunity would arise, if he were given sufficient time, either to forge such a will, or by some trick to induce her to sign a document which would give him control of her wealth after her death. His precipitate action and her resentment destroyed his chance in this respect.

Camille Holland was not a young and inexperienced girl, to be cajoled. She might be ignorant of lovers and their ways, but she had a remarkably good idea of her rights, as she had already shown him, and a reconciliation seemed beyond hope.

What passed between them in secret will never be known, but from subsequent happenings it is certain that she agreed to allow a period of grace, possibly a day or so, to find other quarters. That she gave, or intended to give him, any monetary assistance is doubtful; she neither communicated with her bankers, nor was any cheque drawn in his favour.

Possibly his retention on the farm was a matter of expediency so far as she was concerned. She had to go into Newport that night to do some shopping, and she may have needed him to drive her there. The fact that they subsequently left the farm together does not prove that there was any reconciliation, but rather that she was making use of him, as she herself was not able to drive.

People living in the country did most of their shopping on Fridays, and undoubtedly it was to visit Newport for that purpose that Miss Holland dressed herself about half-past six on the night of Friday, May 19th, and, going into the kitchen, asked her servant if there was anything she required.

One of the theories offered was that she was taking Dougal to the railway station and intended returning alone, but as she made no statement to the girl, who would be mostly affected by this action, the probability is that the more simple explanation is the true one.

The girl went out and saw that Dougal had harnessed the horse and was awaiting the arrival of his wife. She saw Miss Holland get up by the man's side, and as he flicked his whip and the trap drove over the moat bridge, she heard Miss Holland say:

"Good-bye, Florrie. I shall not be long."

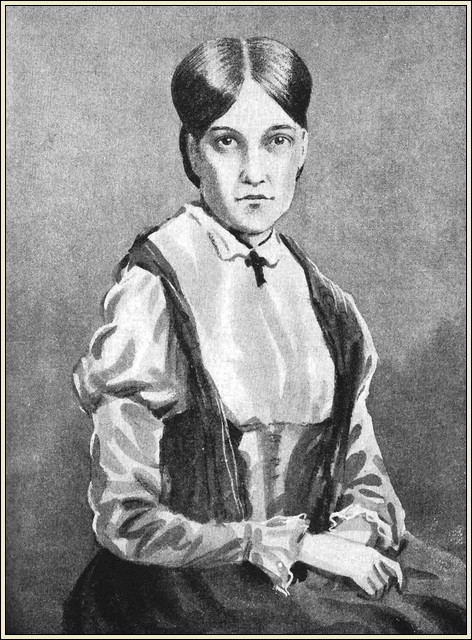

Camille Holland

NOBODY else saw them depart. It was quite light, and very unlikely that Dougal offered the woman any violence at that moment. It is certain that the trap did not go into Newport, and that Miss Holland did no shopping whatever. What is more likely is that Dougal employed the drive, following unfrequented roads, to secure from his mistress her forgiveness for his act, and that his efforts were unsuccessful. It is probable that the time occupied by his vain attempt to bring about a reconciliation was such that it was too late to go into Newport, and that, at her request, he drove her back to the farm.

At half-past eight Florrie Havies heard the sound of cart-wheels crossing the bridge, and a few minutes later Dougal came into the kitchen. At half-past eight in the middle of May, before the introduction of summertime, it would be almost dark. The girl looked up apprehensively and, seeing him arrive alone, asked:

"Has Mrs. Dougal gone upstairs?"

"No," replied Dougal; "she has gone up to London by train. She will be back to-night. I am going to fetch her."

On the face of it the story was palpably false, for there was no train from Newport to London until one that left at eleven o'clock in the evening, the previous one having departed a few minutes after the pair left the farm together. This, however, Florence Havies did not know, and she accepted the story, which in all probability confirmed some statement Miss Holland had made in the course of the day to the effect that she would consult her solicitors or her nephew, or somebody whom she could trust, about the terrible position in which she found herself.

What happened was that Dougal had returned to the farm half an hour before he came into the kitchen, and, having induced Miss Holland to descend, had shot her dead by means of a revolver which he had placed just below the right ear, and had dropped the body into one of the half-filled trenches he had made in his work on the moat. It is certain that he did not bury her at once, and that when he made his excuse for going out to meet her by a later train, in reality he carried a spade to the spot and occupied the time in filling in the ditch so that the remains of the unfortunate woman were hidden from view.

Again he came back, to say that Mrs. Dougal had not arrived, and probably would not be back until the midnight train, going out again and continuing his dreadful work, before he returned, at a quarter to one, with the news that she would not come that night.

"You had better go to bed," he said, and the frightened girl went up to her room, locked, bolted and barricaded the door as well as she could with a few articles of furniture in the room, and spent the night standing at the window, fully dressed, starting at every sound.

She did not hear Dougal come upstairs, and, so far as she could tell, he did not go to bed that night. As soon as the dull dawn light appeared in the sky, Dougal had returned to the scene of his crime, and by the light of day had searched for and removed all suspicious traces of his deed, throwing more earth into the trench and levelling it down so that the notice of the farm labourers should not be attracted. "When the girl came down early in the morning she was surprised to find that Dougal was in the kitchen, and had already prepared his breakfast. He greeted her with a cheerful smile.

"I have just had a letter from Mrs. Dougal," he said (a surprising statement to make, considering the earliness of the hour and the known fact that the post was not delivered until eight o'clock). "She says she is going away for a short holiday, and she will send another lady down."

The curious fact was that Dougal had indeed arranged for a lady to come to the farm, for, some days previous to the occurrence, he had written to his third wife, telling her to come to Stanstead, a village in the neighbourhood, and had rented a small cottage for her, where she took up her residence on the day before the murder. This, however, is no proof that the murder was long premeditated.

Dougal was now a landed proprietor, and thought he could afford the luxury of another establishment, especially since the rent of that establishment was no more than six shillings and sixpence a week.

The knowledge that his wife was there added to the fact that he knew the girl was leaving that same day, was seized upon by him as a heaven-sent coincidence, for he guessed the girl would talk, and the appearance of another woman at the farm would thus be accounted for.

That same day Florence Havies' mother arrived and took her daughter away, not without expressions of regret on the part of Dougal that the girl should have so misrepresented his action, his contention being that he had knocked at the door intending to wind up a clock that was in the room!

The mentality of Dougal is not impressive. The crude lies he told about the letter having arrived before it could possibly have been delivered, the lie he told the girl's mother, no less than the stupidity of making advances to a girl who was a perfect stranger to him and who had previously repulsed him, speak very little for his intelligence, though they point to the queer egotism which is the peculiar possession of the professional murderer.

Scarcely had the servant disappeared than a new Mrs. Dougal, and this time the real Mrs. Dougal, arrived. He must have written on the morning following the murder, telling her to come. In the next four years the Moat Farm saw many mistresses. The real Mrs. Dougal came and went; new and attractive servants arrived, and became victims to the man's unscrupulous desire for novelty. Amongst these were two sisters, one of whom became the mother of his child.

His financial position was now assured; he had gained from Miss Holland a very complete knowledge of her possessions; he knew the name of her broker, and copies of their letters and of all previous stock and share transactions were available.

Ten days after the murder the Piccadilly branch of the National and Provincial Bank received a letter, written in the third person, asking for a cheque-book. One was sent, addressed to Miss Camille Holland, The Moat House, and on June 6th a letter was received by the bank, enclosing a £25 cheque and asking for payment in £5 notes. The bank sent the money on in the usual way, but the manager, noticing some slight discrepancy in the signature, asked that this demand should be confirmed. In reply came a letter:

"The cheque for £25 to Dougal is quite correct. Owing to a sprained hand there may have been some discrepancies in some of my cheques lately signed."

DOUGAL now set himself the task of converting Miss Holland's securities into cash, and her brokers, Messrs. William Hart, received instructions to sell. It is probable that she had sufficient money on her person or in the house at time of her death to carry him on for a month or two, for it was not until September that he instructed the brokers to sell stock to the value of £940, which was duly paid into Miss Holland's account. This was followed a month later by a smaller cash payment, and a year later by a payment of £546. In addition to these, on September 18th a letter purporting to be signed by Camille C. Holland instructed the bank to forward certificates of £500-worth of United Alkali shares and £400 of George Newnes' Preference.

Dougal went about his work with extraordinary care. All the monies that were paid on account of Miss Holland went into her bank and remained in the current account until he withdrew it by cheque in her name.

A year later, at the same time as he was instructing Hart, he forwarded a request that the bank should send to Hart a number of other shares for sale.

The skill with which the forgeries were executed may be illustrated by the fact that when, three years later. Miss Holland's nephew denounced a certain cheque as a forgery, he was equally emphatic that other documents bearing her signature were forgeries, though they were proved by the bank to have been signed by Miss Holland herself on the bank premises.

Nor did Dougal stop short at forging cheques; whole letters in her handwriting were sent to the brokers and bankers, the writing so cleverly imitated that both the banker and the broker concerned were satisfied that they were genuine. In all, Dougal secured in this way nearly £6,000.

During the three years that followed the death of Camille Holland nobody seemed to have had the slightest suspicion that she had come to a violent end. Nor is this remarkable, for the only person who knew of their relationship, the servant, Florence Havies, had long since left the neighbourhood and had married, whilst Miss Holland's only living relative, the nephew, was not in the habit of receiving letters or any kind of communication from his aunt. The house agent who had heard the little breeze which followed Dougal's attempt to get the property transferred to himself, had ceased to take any interest in Moat Farm after it had been removed from his books as a saleable proposition.

Dougal's path was by no means a smooth one. He had to face police-court proceedings brought by Kate Cranwell, the servant, in regard to her child. In the early part of 1902 one of Dougal's victims, who had been admitted into closer confidence than her predecessors, was spurred by jealousy, and a desire to get even with the man who had wronged her, to make a statement to the police regarding Miss Holland's disappearance. She could not have known the facts, and it is probable that Dougal, in an unguarded moment, had boasted that he was enjoying the income of the dead woman, and imagination had supplied the informer with a garbled version of what had really happened.

It was at first believed that Miss Holland was alive, locked up somewhere by Dougal, and forced from time to time to sign cheques on his behalf. This at least was the theory of Superintendent Pryke, in charge of the district, who called at the farm and had a talk with Dougal. The latter, as usual, was frankness itself.

"I know nothing about her, and have not seen or heard from her since I took her and left her at Stanstead Station three years ago. I drove her there with her luggage, consisting of two boxes."

"But don't you know her relations or friends?" asked the superintendent.

Dougal shook his head.

"She left nothing behind her in the house. We had a tiff, in consequence of the servant telling her that I wanted to go into the girl's room."

"Have you seen any papers bearing the name of Miss Holland, or any letters addressed to her?" asked the superintendent.

"None," replied Dougal—a somewhat rash statement to make, in view of the fact that letters had been continuously delivered at the house addressed to Miss Camille Holland.

"It is said she is shut up in the house," said the superintendent. "Will you let me have a look round?"

Dougal laughed and said:

"Certainly; go where you like."

THE superintendent made a very careful inspection of the house, but found nothing, and returned to ask if it was true that Dougal had given away some of Miss Holland's clothes to his own wife and servant, and that they had had them altered. He replied:

"I couldn't do that, because she left nothing behind her."

Dougal had an account at the Birkbeck Bank, and the day that Superintendent Pryke saw him he drew out practically the whole of his balance, £305. This fact was known through a shrewd inspector (Marsden), who did not share the superintendent's complete faith in Dougal's bona fides. Undoubtedly Superintendent Pryke was gulled by the seeming frankness of the master of Moat Farm, and his report was creditable to the man whom he had cross-examined.

Marsden began searching round for a relative, and presently found the nephew, who was taken to see certain The cheques which had been drawn and had been apparently signed by Miss Holland. He declared them, without too close an inspection, to be forgeries. This was all that Marsden required. He was satisfied that Camille Holland had been done to death, but it was absolutely necessary that he should have Dougal in safe keeping whilst he made a leisurely examination of the property; and though the grounds for the warrant were very slight, and, indeed, the evidence of the nephew would have been absolutely worthless to secure a conviction for forgery, the warrant was granted.

A cheque had been drawn by Dougal in Miss Holland's name, and the bank had paid him the sum in £10 notes. These notes were immediately stopped, and, as though he were knowingly playing into the hands of the police, Dougal went to the Bank of England to change the £10 notes into £5 notes, signed a false name on the back of one, and was immediately arrested on a charge of forgery.

Had no further charge followed, it is certain that Dougal would not have been convicted, for the evidence against him was of the flimsiest kind, and the fact that both the broker and the banker were satisfied that the signatures were genuine would have disposed of the prosecution's case.

But the arrest served its purpose: no sooner was Dougal in the hands of the police than Scotland Yard descended upon the Moat Farm and took possession.

Thereafter followed days and weeks of search which will not readily be forgotten, either by the police or by those journalists, like myself, whose duty held them to this bleak and ugly spot. Week after week, Dougal, handcuffed and between warders, was marched from the railway station to the little courthouse at Saffron Walden to hear the scraps of evidence and the invariable request for a remand. Week after week the police probed and pried, dug up floors and examined outhouses, in the vain hope of finding something which would solve the mystery of Miss Holland's disappearance.

What complicated the search was the discovery in the first day or two of a skull in one of the sheds. It had the appearance of having been burnt, and at first it was thought that this was a portion of the remains of the woman. But it afterwards transpired that the skull had been at the farm when Miss Holland was still alive.

It is a curious fact that, though the general opinion amongst the reporters present was that the body of the woman was in the moat, and although it was also known that in the early days of Dougal's occupation there were open trenches leading to the moat, no attempt was made to investigate these "leaders" until every other channel had been explored and every possible hiding- place examined. The police were giving up the search in despair when one of the journalists present said to the detective in charge:

"Why don't you open one of these trenches that Dougal filled up?"

A corner of the moat at the Moat Farm.

The idea occurred simultaneously to Detective Inspector Marsden, and a labourer was sent for with instructions to dig steadily. His work had not proceeded far when his spade turned up a boot. Very soon afterwards the body of Miss Holland was exposed, and Dougal's secret was a secret no more.

With some difficulty the body was brought to ground level and taken to a summerhouse. A jury was hastily summoned, and the first sitting of the inquest was held in a great, stark barn on the property.

Hither, heavily guarded, Dougal was brought, and the scene was one which will long linger in the memory of the witnesses. The old barn with its thatched roof was crumbling away with age and neglect. The only light was that admitted by the door, which had been swung back. Here, under the twisted beams and crooked rafters, the court arranged itself as best it could, and Dougal, led past the open grave of his victim, came into the gloom of this queer coroner's court.

The work of the police, however, was not finished with their terrible discovery. Was the body that of Camille Holland? The face was unrecognisable; there were no peculiar marks by which she could be identified. The rotten remnants of a dress might be sworn to by Mrs. Wiskens of Saffron Walden, who had stitched some braid upon it, but it was not sufficient evidence to convict Dougal.

The dress was like thousands of other dresses; the hair shape, the bustle, the various other wisps of clothing which were found might have been worn by any other woman. All that was known was that she had been a woman and that she was murdered, for there was a bullet-hole in the skull, and the bullet itself was discovered at the post-mortem examination.

Still, there was sufficient evidence to commit Dougal for trial on the capital charge, and there was one witness, and one witness alone, who could hang him. This was Mold, a bootmaker of Edgware Road.

Miss Holland had patronised Mold regularly. Her feet were so small (and they had been her great pride) that her boots had to be specially made for her, and Mr. Mold had built a last and made a number of pairs of boots of one pattern. They were half a size smaller than she required, and were lined with lamb's- wool. Mold invariably made these himself, working his initials with brass tacks in the heels of each pair.

There might be in the world thousands of women with small feet, thousands who wore tiny boots; there might be many who wore tiny boots lined with lamb's- wool, as these were lined; but the "M" in brass tacks found in the dead woman's heel was undoubtedly Mold's work, and he only had one customer who wore shoes of this kind, and that customer was Camille Holland.

Dougal's trial ran an extraordinary course. He stood up in the quaint assize court at Chelmsford and received sentence of death from the lips of Mr. Justice Wright, and on a bright July morning he stood up again, this time to meet the executioner. For a second he flinched, until somebody handed him a glass of brandy and water, and he drank it down. Then, without a word, he submitted to the strapping and paced the short distance to the scaffold. There was a tense and deathly silence, broken by the agitated voice of the chaplain.

"Dougal, are you guilty?"

There was no reply.

Billington fingered the lever nervously and looked almost imploringly at the pastor as though he were asking him not to prolong the agony of the man on the drop.

"Dougal, are you guilty or not guilty?" asked the clergyman again, and in a low but clear voice came the muffied reply:

"Guilty."

As he spoke the word Billington pulled the lever.