Field-Marshal Sir John French

Commander of the Expeditionary Force

IT is unnecessary within the scope of this volume to do more than sketch the events which led to a condition of war between Great Britain, France, Russia, Belgium and Servia on the one part, and Germany and Austria-Hungary on the other.

The assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his consort at Sarajevo, on July 25, was the ostensible reason for the presentation of the Austro- Hungarian note to Servia. This made demands upon Servia with which no self- governing state could comply, and was followed by military preparations in the dual kingdom.

Russia, who saw in these demands an oblique challenge to her as guardian of the Slav peoples, at once began to move. But at the earnest request of Sir Edward Grey her military mobilization was delayed whilst efforts were made not only by Great Britain, but by France to induce the Government of Germany to exercise its undoubted influence to avert war between Servia and Austria- Hungary.

Germany tacitly declined to second the efforts of Great Britain, and on July 30 a partial mobilization of the Russian Army was ordered, followed on the next day by a ukase commanding a general mobilization.

Even now Great Britain did not give up hope of averting the calamity of a European war, though Germany had declared herself in a state of war. But on the following day all hope of peace was abandoned. Although the mobilization of the Russian Army was explicitly directed towards Austria-Hungary, who had opened her campaign against Servia by a bombardment of Belgrade, the German Government cast the torch into the world.

On August 1 at 7.30 p.m. (Russian time) Germany declared war upon Russia, and German troops waiting on the frontier, gathered there in readiness, invaded the Neutral State of Luxemburg, and, seizing the railway, established the headquarters of the invading army in the capital. This was immediately followed by an ominous movement on the frontier of Belgium, the neutrality of which country was guaranteed by the Powers, including Great Britain, France and Germany.

Great Britain addressed questions couched in identical terms to France and Germany. Would these powers respect the neutrality of Belgium?

The reply of the French Government was prompt, and was in the affirmative. In the war of 1870, France had given a similar undertaking and had most honourably fulfilled her part, though by so doing she was compelled to fight the disastrous battle of Sedan.

The German reply, however, was evasive. Great Britain repeated her question, and demanded, through her Ambassador, a reply by eleven o'clock that night (German time). This was on August 4, two days after Germany had called upon Belgium to allow the unhampered passage of her troops through that country—a demand which was rejected by the Belgian Government with little hesitation.

On August 4 two German Army Corps, under General von Emmich, were already hammering at the door of Belgium, claiming admission. But the door was a particularly stout one, and Liège, splendidly commanded by General Leman, swept back the first attack without difficulty.

On the 4th of August, whilst the guns thundered about Liège, the order went forth for the mobilization of the British Army, and there followed the quiet, orderly gathering of reservists all over Great Britain.

On the 6th of August two of the Liège forts were silenced. The gallant commander—General Leman—was taken prisoner, having been found in an unconscious state amidst the ruins of one of the forts he had so bravely defended.

So terrible had been the havoc created by the Belgian artillery and infantry fire that the German commander asked for an armistice of twenty-four hours to bury his dead, a request which was refused.

But the German had his foothold, and through the area which had previously been swept by the guns of the two forts which were now destroyed the main body of the covering army passed into the town of Liège, leaving the remainder of the forts intact.

Heavy fighting between the Belgians and the invader now followed. French troops rushed northward, held Dinant and the country about, and there were fierce encounters between the traditional enemies who, further south, were already at grips in Alsace.

Between the German occupation of Liège and the events which are chronicled in this book, much happened. There was prolonged and bitter outpost fighting between the Belgians and their invader, and after a siege of ten days the remaining forts of Liège were reduced by means of very heavy guns. Among them the 42-centimeter howitzer, specially constructed by Krupps, was employed with very deadly effect.

The covering armies under von Emmich had been strongly reinforced, and it was now evident that the main attack upon France was to be expected from this quarter.

It was not until the 16th of August that the first instalment of the Expeditionary Army of Great Britain completed its landing in France. That force was under the command of Field-Marshal Sir John French. It consisted of two Army Corps, the composition of which was not revealed. Sir John French hastened to Paris for a brief consultation with the French War Minister and his colleagues before leaving to make his dispositions for resisting the advance of the enemy from Belgium.

Now threatened by the rapid advance of the main German Army, the Belgian Government transferred its seat from Brussels to Antwerp. On the 20th, the German Army entered Brussels, the civic guard having been disarmed by order of the burghomaster.

Whilst the right wing of the Germans was in possession of the capital, other great armies were moving diagonally toward the French frontier. On the 21st of August the French, who were holding a line of which the Belgian town of Charleroi was either the left or the left centre, came into touch with the enemy, and fierce fighting ensued.

On the next day another German Army attacked Namur, which marked the right of the French position. Namur, which was expected to offer even a more determined resistance than Liège had done, was carried after two days' fighting.

The French were beginning to fall back from Charleroi when, on August 22, the British came to their position at Mons, which lies directly to the left of where the French had been fighting. Only now did it become apparent to the defending line that the attack was being made in overwhelming strength. The battle of Charleroi was ended, our Ally was actually falling back, and Namur had been evacuated when the events which Sir John French describes began.

(From Field-Marshal Sir John French)

RECEIVED by the Secretary of State for War from the Field-Marshal Commanding-in-Chief, British Forces in the Field—

September 7, 1914.

MY LORD,

I have the honour to report the proceedings of the Field Force under my command up to the time of rendering this despatch.

The transport of the troops from England both by sea and by rail was effected in the best order and without a check. Each unit arrived at its destination in this country well within the scheduled time.

The concentration was practically complete on the evening of Friday, the 21st ultimo, and I was able to make dispositions to move the Force during Saturday, the 22nd, to positions I considered most favourable from which to commence operations which the French Commander-in-Chief, General Joffre, requested me to undertake in pursuance of his plans in prosecution of the campaign.*

[* It will be remembered that Sir John French visited the French War Office in Paris before leaving for the front to take command of the British Expeditionary Force.]

The line taken up extended along the line of the canal from Condé on the west, through Mons and Binche on the east. This line was taken up as follows—

From Condé to Mons inclusive was assigned to the 2nd Corps, and to the right of the 2nd Corps from Mons the 1st Corps was posted. The 5th Cavalry Brigade was placed at Binche.

In the absence of my 3rd Army Corps,* I desired to keep the Cavalry Division as much as possible as a reserve to act on my outer flank, or move in support of any threatened part of the line. The forward reconnaissance was entrusted to Brigadier-General Sir Philip Chetwode with the 5th Cavalry Brigade, but I directed General Allenby to send forward a few squadrons to assist in this work.

[* One division (20,000 men) of the 3rd Corps came over in time to play a very worthy part in the fight at Le Cateau later. They got out of the train and went straight into battle, a fact which General French emphasizes later.]

During August 22nd and 23rd these advanced squadrons did some excellent work, some of them penetrating as far as Soignies, and several encounters took place in which our troops showed to great advantage.

At 6 a.m. on August 23 I assembled the Commanders of the 1st and 2nd Corps and Cavalry Division at a point close to the position, and explained the general situation of the Allies, and what I understood to be General Joffre's plan. I discussed with them at some length the immediate situation in front of us.

From information I received from French Headquarters I understood that little more than one, or at most two, of the enemy's Army Corps, with perhaps one Cavalry Division, were in front of my position;* and I was aware of no attempted outflanking movement by the enemy. I was confirmed in this opinion by the fact that my patrols encountered no undue opposition in their reconnoitring operations. The observation of my aeroplanes seemed also to bear out this estimate.

[* About this time the information as to German movements were very vague. We knew that they were massing on the right bank of the Meuse north of Liège, and that they were assembling before Namur. The appearance of the great army in and about Brussels was, however, reported many days before the 22nd, which makes the lack of information afforded to General French a little inexplicable.]

About 3 p.m. on Sunday, the 23rd, reports began coming in to the effect that the enemy was commencing an attack on the Mons line, apparently in some strength, but that the right of the position from Mons and Bray was being particularly threatened.

The Commander of the 1st Corps had pushed his flank back to some high ground south of Bray, and the 5th Cavalry Brigade evacuated Binche, moving slightly south; the enemy thereupon occupied Binche.

The right of the 3rd Division, under General Hamilton, was at Mons, which formed a somewhat dangerous salient,* and I directed the Commander of the 2nd Corps to be careful not to keep the troops on this salient too long, but, if threatened seriously, to draw back the centre behind Mons. This was done before dark. In the meantime, about 5 p.m., I received a most unexpected message from General Joffre by telegraph, telling me that at least three German Corps, viz. a reserve corps, the 4th Corps and the 9th Corps, were moving on my position in front, and that the 2nd Corps was engaged in a turning movement from the direction of Tournay. He also informed me that the two reserve French divisions and the 5th French Army on my right were retiring,† the Germans having on the previous day gained possession of the passages of the Sambre between Charleroi and Namur.

[* A salient is a position projecting outward at an angle, and consequently assailable from two sides. Forces holding such a position may easily be surrounded or cut off from the main body.]

[† What few people realize is that in their retreat from Mons and Condé the British were largely on their own. They saw nothing of the French on their right save Territorial troops, and did not know of the desperate fighting round Charleroi. Indeed, very few of the British force ever saw a French soldier after the fighting began until the 27th of August.]

In view of the possibility of my being driven from the Mons position, I had previously ordered a position in the rear to be reconnoitred. This position rested on the fortress of Maubeuge on the right and extended west to Jenlain, south-east of Valenciennes, on the left. The position was reported difficult to hold, because standing crops and buildings made the siting of trenches very difficult and limited the field of fire in many important localities. It nevertheless afforded a few good artillery positions.

When the news of the retirement of the French and the heavy German threatening on my front reached me, I endeavoured to confirm it by aeroplane reconnaissance; and as a result of this I determined to effect a retirement to the Maubeuge position at daybreak on the 24th.

A certain amount of fighting continued along the whole line throughout the night, and at daybreak on the 24th the 2nd Division from the neighbourhood of Harmignies made a powerful demonstration as if to retake Binche. This was supported by the artillery of both the 1st and 2nd Divisions, whilst the 1st Division took up a supporting position in the neighbourhood of Peissant. Under cover of this demonstration the 2nd Corps retired on the line Dour-Quarouble-Frameries. The 3rd Division on the right of the Corps suffered considerable loss in this operation from the enemy, who had retaken Mons.

The 2nd Corps halted on this line, where they partially entrenched themselves, enabling Sir Douglas Haig with the 1st Corps gradually to withdraw to the new position; and he effected this without much further loss, reaching the line Bavai-Maubeuge about 7 p.m. Towards midday the enemy appeared to be directing his principal effort against our left.

I had previously ordered General Allenby with the Cavalry to act vigorously in advance of my left front and endeavour to take the pressure off.

About 7.30 a.m. General Allenby received a message from Sir Francis Fergusson, commanding 5th Division, saying that he was very hard pressed and in urgent need of support. On receipt of this message General Allenby drew in the Cavalry and endeavoured to bring direct support to the 5th Division.

During the course of this operation General De Lisle, of the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, thought he saw a good opportunity to paralyse the further advance of the enemy's infantry by making a mounted attack on his flank. He formed up and advanced for this purpose, but was held up by wire* about 500 yards from his objective, and the 9th Lancers and 18th Hussars suffered severely in the retirement of the Brigade.

[* Barbed wire entanglements may be hastily but none the less effectively constructed for the protection of infantry and artillery from Cavalry attack. This protection might be given more easily in such a country as that through which the British were fighting, by the fact that there may have been a great deal of "natural wire" (i.e. wire fences fixed by farmers to mark boundaries, etc.).]

The 19th Infantry Brigade, which had been guarding the Line of Communications, was brought up by rail to Valenciennes on the 22nd and 23rd. On the morning of the 24th they were moved out to a position south of Quarouble to support the left flank of the 2nd Corps.

With the assistance of the Cavalry Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien was enabled to effect his retreat to a new position; although, having two corps of the enemy on his front and one threatening his flank, he suffered great losses in doing so.

At nightfall the position was occupied by the 2nd Corps to the west of Bavai, the 1st Corps to the right. The right was protected by the fortress of Maubeuge, the left by the 19th Brigade in position between Jenlain and Bry, and the Cavalry on the outer flank.

The French were still retiring, and I had no support except such as was afforded by the fortress of Maubeuge; and the determined attempts of the enemy to get round my left flank assured me that it was his intention to hem me against that place and surround me. I felt that not a moment must be lost in retiring to another position.

I had every reason to believe that the enemy's forces were somewhat exhausted, and I knew that they had suffered heavy losses. I hoped therefore that his pursuit would not be too vigorous to prevent me effecting my object.

The operation, however, was full of danger and difficulty, not only owing to the very superior force in my front, but also to the exhaustion of the troops.

The retirement was recommenced in the early morning of August 25 to a position in the neighbourhood of Le Cateau, and rearguards were ordered to be clear of the Maubeuge-Bavai-Eth Road by 5.30 a.m.

Two Cavalry Brigades, with the Divisional Cavalry of the 2nd Corps, covered the movement of the 2nd Corps. The remainder of the Cavalry Division, with the 19th Brigade, the whole under the command of General Allenby, covered the west flank.

The 4th Division commenced its detrainment at Le Cateau on Sunday, the 23rd, and by the morning of the 25th eleven battalions and a Brigade of Artillery with Divisional Staff were available for service.*

[* This Division had only left Cambridge on the Saturday morning (22nd), and had come through punctually without stopping. It is believed that the transportation of the 4th Division through England and the very proper reticence and secrecy shown in the dispatch of this force, gave rise to the extraordinary rumour that a strong Russian force was passing over our railways. It was after the dispatch of the 4th Division that this rumour began to gain ground.]

I ordered General Snow to move out to take up a position with his right south of Solesmes, his left resting on the Cambrai-Le Cateau Road south of La Chaprie. In this position the Division rendered great help to the effective retirement of the 2nd and 1st Corps to the new position.

Although the troops had been ordered to occupy the Cambrai-Le Cateau- Landrecies position, and the ground had, during the 25th, been partially prepared and entrenched, I had grave doubts—owing to the information I received as to the accumulating strength of the enemy against me—as to the wisdom of standing there to fight.

Having regard to the continued retirement of the French on my right, my exposed left flank, the tendency of the enemy's western corps (II) to envelop me, and, more than all, the exhausted condition of the troops, I determined to make a great effort to continue the retreat till I could put some substantial obstacle, such as the Somme or the Oise, between my troops and the enemy, and afford the former some opportunity of rest and reorganization. Orders were, therefore, sent to the Corps Commanders to continue their retreat as soon as they possibly could towards the general line Vermand-St. Quentin-Ribemont.

The Cavalry, under General Allenby, were ordered to cover the retirement.

Throughout the 25th and far into the evening the 1st Corps continued its march on Landrecies, following the road along the eastern border of the Forfit de Mormal, and arrived at Landrecies about ten o'clock. I had intended that the Corps should come further west so as to fill up the gap between Le Cateau and Landrecies, but the men were exhausted and could not get further in without rest.

The enemy, however, would not allow them this rest, and about 9.30 p.m. a report was received that the 4th Guards Brigade in Landrecies was heavily attacked by troops of the 9th German Army Corps who were coming through the forest on the north of the town. This brigade fought most gallantly and caused the enemy to suffer tremendous loss in issuing from the forest into the narrow streets of the town. This loss has been estimated from reliable sources at from 700 to 1000. At the same time information reached me from Sir Douglas Haig that his 1st Division was also heavily engaged south and east of Maroilles. I sent urgent messages to the Commander of the two French Reserve Divisions on my right to come up to the assistance of the 1st Corps, which they eventually did. Partly owing to this assistance, but mainly to the skilful manner in which Sir Douglas Haig extricated his Corps from an exceptionally difficult position in the darkness of the night, they were able at dawn to resume their march south towards Wassigny on Guise.

By about 6 p.m. the 2nd Corps had got into position with their right on Le Cateau, their left in the neighbourhood of Caudry, and the line of defence was continued thence by the 4th Division towards Seranvillers, the left being thrown back.

During the fighting on the 24th and 25th the Cavalry became a good deal scattered, but by the early morning of the 26th General Allenby had succeeded in concentrating two brigades to the south of Cambrai.

The 4th Division was placed under the orders of the General Officer Commanding the 2nd Army Corps.

On the 24th the French Cavalry Corps, consisting of three divisions, under General Sordfit, had been in billets north of Avesnes. On my way back from Bavai, which was my "Poste de Commandement" during the fighting of the 23rd and 24th, I visited General Sordfit, and earnestly requested his co-operation and support.* He promised to obtain sanction from his Army Commander to act on my left flank, but said that his horses were too tired to move before the next day. Although he rendered me valuable assistance later on in the course of the retirement, he was unable for the reasons given to afford me any support on the most critical day of all, viz. the 26th.

[* No account of the retirement has as yet been published by the French War Office, so that it is impossible to say tinder what circumstances General Sordfit's Division had been rendered temporarily ineffective. The French had been very heavily engaged on the British right—the part played by the cavalry in that engagement is yet to be made known. At the end of the war, when the full French reports are published, this failure of the French cavalry will probably admit of remarkable explanation.]

At daybreak on August 26 it became apparent that the enemy was throwing the bulk of his strength against the left of the position occupied by the 2nd Corps and the 4th Division.

At this time the guns of four German Army Corps were in position against them, and Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien reported to me that he judged it impossible to continue his retirement at daybreak (as ordered) in face of such an attack.

I sent him orders to use his utmost endeavours to break off the action and retire at the earliest possible moment, as it was impossible for me to send him any support, the 1st Corps being at the moment incapable of movement.

The French Cavalry Corps, under General Sordfit, was coming up on our left rear early in the morning, and I sent an urgent message to him to do his utmost to come up and support the retirement of my left flank; but owing to the fatigue of his horses he found himself unable to intervene in any way.

There had been no time to entrench the position properly, but the troops showed a magnificent front to the terrible fire which confronted them.

The Artillery, although outmatched by at least four to one, made a splendid fight, and inflicted heavy losses on their opponents.

At length it became apparent that, if complete annihilation was to be avoided, a retirement must be attempted; and the order was given to commence it about 3.30 p.m. The movement was covered with the most devoted intrepidity and determination by the Artillery, which had itself suffered heavily, and the fine work done by the Cavalry in the further retreat from the position assisted materially in the final completion of this most difficult and dangerous operation.

Fortunately the enemy had himself suffered too heavily to engage in an energetic pursuit.

I cannot close the brief account of this glorious stand of the British troops without putting on record my deep appreciation of the valuable services rendered by General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien.

I say without hesitation that the saving of the left wing of the Army under my command on the morning of the 26th August could never have been accomplished unless a commander of rare and unusual coolness, intrepidity, and determination had been present to personally conduct the operation.

The retreat was continued far into the night of the 26th and through the 27th and 28th, on which date the troops halted on the line Noyon-Chauny-La Fère, having then thrown off the weight of the enemy's pursuit.

On the 27th and 28th I was much indebted to General Sordfit and the French Cavalry Division which he commands for materially assisting my retirement and successfully driving back some of the enemy on Cambrai.

General D'Amade also, with the 61st and 62nd French Reserve Divisions, moved down from the neighbourhood of Arras on the enemy's right flank and took much pressure off the rear of the British Forces.

This closes the period covering the heavy fighting which commenced at Mons on Sunday afternoon, August 23, and which really constituted a four days' battle.

At this point, therefore, I propose to close the present despatch.

I deeply deplore the very serious losses which the British Forces have suffered in this great battle; but they were inevitable in view of the fact that the British Army—only two days after a concentration by rail—was called upon to withstand a vigorous attack of five German Army Corps.*

[* Roughly about 250,000 men. General French at this time had two Army Corps, a Cavalry Division and the 4th Division of eleven battalions and an artillery brigade, in all about 98,000 men. Smith-Dorrien's force of 50,000-60,000 men had at one time four German Corps arrayed against him.]

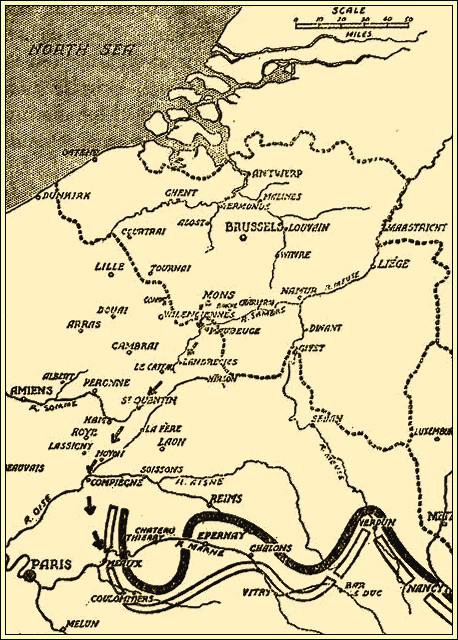

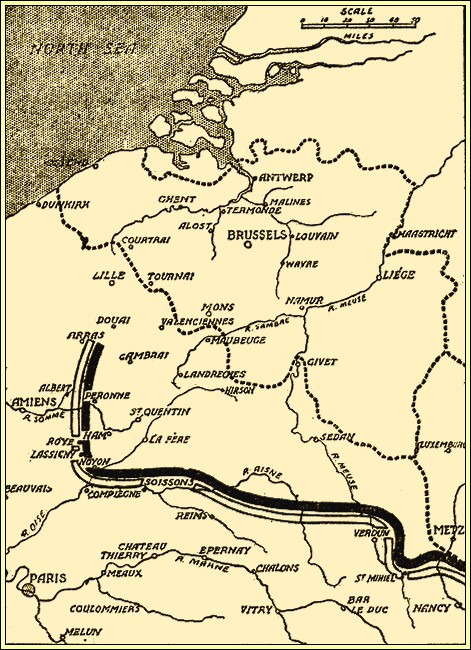

The line of the retreat from Mons is indicated by

arrows.

The approximate position of the opposing armies at the

most southerly point of the German advance is also shown.

It is impossible for me to speak too highly of the skill evinced by the two General Officers commanding Army Corps; the self-sacrificing and devoted exertions of their Staffs; the direction of the troops by Divisional, Brigade and Regimental Leaders; the command of the smaller units by their officers; and the magnificent fighting spirit displayed by non-commissioned officers and men.

I wish particularly to bring to your Lordship's notice the admirable work done by the Royal Flying Corps under Sir David Henderson.* Their skill, energy, and perseverance have been beyond all praise. They have furnished me with the most complete and accurate information which has been of incalculable value in the conduct of the operations. Fired at constantly both by friend and foe, and not hesitating to fly in every kind of weather, they have remained undaunted throughout.

[* Sir David Henderson, in addition to being largely the organizer of the air-service, is an authority upon Reconnaissance. His regiment was "The Thin Red Line" (the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders) and he saw active service in the Soudan, where he was mentioned in dispatches; in South Africa (wounded) he was again "mentioned," and earned the Distinguished Service Order.]

Further, by actually fighting in the air, they have succeeded in destroying five of the enemy's machines.

I wish to acknowledge with deep gratitude the incalculable assistance I received from the General and Personal Staffs at Headquarters during this trying period.

Lieutenant-General Sir Archibald Murray,* Chief of the General Staff; Major-General Wilson, Sub-Chief of the General Staff;† and all under them have worked day and night unceasingly with the utmost skill, self-sacrifice and devotion; and the same acknowledgment is due by me to Brigadier-General Hon. W. Lambton, my Military Secretary and the Personal Staff.‡

In such operations as I have described the work of the Quartermaster-General is of an extremely onerous nature. Major-General Sir William Robertson# has met what appeared to be almost insuperable difficulties with his characteristic energy, skill and determination; and it is largely owing to his exertions that the hardships and sufferings of the troops—inseparable from such operations—were not much greater.

[* Sir Archibald James Murray was for many years Director of Military Training, and the efficiency of the British Army owes much to his splendid work. His regiment was the Royal Inniskillen Fusiliers. He was dangerously wounded in South Africa.]

[† Major-General Henry Hughes Wilson, C.B., has had a great deal of war service, and has seen fighting in India and South Africa. For some years he was commandant of the Staff College, and has held several staff appointments. He was Assistant-Director of Staff duties at the War Office, and also held the post of Assistant Adjutant-General between I goo-6. He is an Irishman and an old Rifle Brigade Officer.]

[‡ Major-General the Hon. William Lambton is the son of the second Earl of Durham, and served with distinction in the Coldstream Guards. He has held very important posts, and was Lord Milner's Military Secretary in South Africa for some years. Major-General Lambton has been in the personal entourage of the King, being Groom-in-Waiting to his Majesty.

[# Sir William is another Staff College Commandant with a considerable experience of war. He has done excellent work for the intelligence department both at home and on active service. He took part in the operations for the relief of Chitral, where he was severely wounded. In South Africa he was also on the Intelligence Staff, and rendered invaluable service to the Commander-in-Chief.

I have not yet been able to complete the list of officers whose names I desire to bring to your Lordship's notice for services rendered during the period under review; and, as I understand it is of importance that this despatch should no longer be delayed, I propose to forward this list, separately, as soon as I can.

I have the honour to be,

Your Lordship's most obedient Servant, (Signed) J.D.P. French, Field- Marshal,

Commander-in-Chief, British Forces in the Field.

General Joffre, Commander of the French Army

WHILST the British were thus engaged, the French on their right were being driven into French Lorraine, and the German forces left to contain the Belgian Army were carrying out their work of destruction.

On the day that Sir John French was fighting so desperately before Le Cateau-Cambrai, the Germans, on the pretext of punishing the shooting of some of their soldiers by the civilian population, had set to work to destroy Louvain, a Zeppelin had dropped bombs on Antwerp, and the great battle before Lemberg had begun in Galicia. These facts are given that the reader may assemble in their chronological order the events of that fateful week. There can be no doubt but that the position of the British Army was critical. If the arrival of the 4th Division had been delayed for two hours the Army Corps under Smith-Dorrien could hardly have extricated itself without suffering enormous losses, if indeed it could have got away at all. The fighting was of a peculiarly fierce character, but pressed as they were the British were a terribly punishing force. Their fire, well directed, was never wasted. The men nursed their ammunition and "shot for heads."* The story is told by one officer that he had all his work cut out to get one section to retire, and there can be no doubt that the losses we sustained in the shape of missing and prisoners taken by the enemy was due largely to the courage of our men, who stuck to their work of beating back the Kaiser's corps.

The German soldiers themselves directed the whole of their resources to outflanking their British opponents.

An Imperial order had gone forth to the German forces directing them

"to devote the whole of your attention to the treacherous English and to walk over General French's contemptible little army."

The task was no light one, in whatever spirit of confidence the German legions came. They sustained enormous losses in the face of the British rifle fire, which has won the admiration of the Allies.

Cool as though on parade or firing at Ash ranges, the infantry were offered excellent practice at between 500 and 600 yards. This is the range at which the British army has invariably shown its highest percentage of hits, and the German losses before Cambrai and Le Cateau must have been very heavy, for the rifle used by our men is the best weapon in the field.

Even in their success the Germans were again and again repulsed.

"They came on in solid formation," writes one officer, "shoulder to shoulder, the most confident body of men that ever marched on to a battle- field. Some of them had unsmoked cigars stuck between the buttons of their tunics ... it looked as if nothing could arrest that heavy mass, but after a sighting shot or two our men got the range and then you saw things happen. In three minutes from being a solid body it became a ragged, straggling line, then it peeled away to nothing. Behind was another double company, and the same thing happened all over again. It was extraordinary to see them skipping and jumping over the bodies of their fallen comrades only to fall themselves and become a further obstacle to the men behind."

This was the British punch, a staggering one, but numbers told in the long run. Swiftly moving columns began to work round the British left, and the order to retire came none too soon. Field-Marshal French was himself under fire most of this day.

[In the internal of the Field-Marshal's personal despatches "Eye-Witness" sent home official reports from time to time.]

IT is now possible to make another general survey of the operations of the British Army during the last week.

No new main trial of strength has taken place. There have indeed been battles in various parts of the immense front which, in other wars, would have been considered operations of the first magnitude; but, in this war, they are merely the incidents of the strategic withdrawal and contraction of the allied forces necessitated by the initial shock on the frontiers and in Belgium, and by the enormous strength which the Germans have thrown into the western theatre, while suffering heavily through weakness in the eastern.

The British Expeditionary Army has conformed to the general movement of the French forces and acted in harmony with the strategic conceptions of the French General Staff.

Since the battle at Cambrai on August 26, where the British troops successfully guarded the left flank of the whole line of French Armies from a deadly turning attack supported by enormous force, the 7th French Army* has come into operation on our left, and this, in conjunction with the 5th Army on our right, has greatly taken the strain and pressure off our men.

[* This was the territorial corps under General Armande.]

The 5th French Army in particular on August 29 advanced from the line of the Oise River to meet and counter the German forward movement, and a considerable battle developed to the south of Guise. In this the 5th French Army gained a marked and solid success, driving back with heavy loss and in disorder three German Army Corps, the 10th, the Guard, and a reserve corps. It is believed that the Commander of the 10th German Corps was among those killed.

In spite of this success, however, and all the benefits which flowed from it, the general retirement to the south continued and the German armies, seeking persistently after the British troops, remained in practically continuous contact with our rearguards.

On August 30 and 31 the British covering and delaying troops were frequently engaged, and on September 1 a very vigorous effort was made by the Germans, which brought about a sharp action in the neighbourhood of Compiègne.

This action was fought principally by the 1st British Cavalry Brigade and the 4th Guards Brigade and was entirely satisfactory to the British.

The German attack, which was most strongly pressed, was not brought to a standstill until much slaughter had been inflicted upon them and until 10 German guns had been captured. The brunt of this creditable affair fell upon our Guards Brigade, who lost in killed and wounded about 300 men.*

[* This was the first decisive check administered to the advancing enemy. Some of the finest troops in the German Army were engaged and the little battle occurred in thickly wooded country.]

After this engagement our troops were no longer molested. Wednesday, September 2, was the first quiet day they had had since the battle of Mons on August 23. During the whole of this period marching and fighting had been continuous, and in the whole period the British casualties had amounted, according to the latest estimates, to about 15,000 officers and men.

The fighting, having been in open order upon a wide front with repeated retirements, has led to a large number of officers and men and even small parties missing their way and getting separated, and it is known that a very considerable number of those now included in the total will rejoin the colours safely.

These losses, though heavy in so small a force, have in no wise affected the spirit of the troops. They do not amount to a third of the losses inflicted by the British force upon the enemy, and the sacrifice required of the Army has not been out of proportion to its military achievements.

In all, drafts amounting to 19,000 men have reached our Army or are approaching them on the line of communication, and advantage is being taken of the five quiet days that have passed since the action of September 1 to fill up the gaps and refit and consolidate the units.

The British Army is now south of the Marne, and is in line with the French forces on the right and left. The latest information about the enemy is that they are neglecting Paris and are marching in a south-easterly direction towards the Marne and towards the left and centre of the French line.

The 1st German Army is reported to be between La Ferté-sous-Jouarre and Essises-Viffort. The 2nd German Army, after taking Reims, has advanced to Chateau-Thierry and to the east of that place. The 4th German Army is reported to be marching south on the west of the Argonne, between Suippes and Ville sur Tourbe. All these points were reached by the Germans on September 3.

The 7th German Army has been repulsed by a French Corps near D'Einville. It would, therefore, appear that the enveloping movement upon the Anglo-French left flank has been abandoned by the Germans, either because it is no longer practicable to continue such a great extension or because the alternative of a direct attack upon the allied line is preferred. Whether this change of plan by the Germans is voluntary or whether it has been enforced upon them by the strategic situation and the great strength of the Allied Armies in their front will be revealed by the course of events.*

[* The line of the Marne was now held by the French in great strength, and the converging German Armies found themselves opposed to forces vastly superior in point of strength and freshness to those which had been engaged to them previously.]

There is no doubt whatever that our men have established a personal ascendancy over the Germans, and that they are conscious of the fact that with anything like even numbers the result would not be doubtful.

The shooting of the German infantry is poor, while the British rifle fire has devastated every column of attack that has presented itself. Their superior training and intelligence has enabled the British to use open formations with effect, and thus to cope with the vast numbers employed by the enemy. The cavalry, who have had even more opportunities for displaying personal prowess and address, have definitely established their superiority.

Sir John French's reports dwell on this marked superiority of the British troops of every arm of the service over the Germans. "The cavalry," he says, "do as they like with the enemy until they are confronted by thrice their numbers. The German patrols simply fly before our horsemen. The German troops will not face our infantry fire, and as regards our artillery they have never been opposed by less than three or four times their numbers."

The following incidents have been mentioned—

During the action at Le Cateau on August 26 the whole of the officers and men of one of the British batteries had been killed or wounded with the exception of one subaltern and two gunners. These continued to serve one gun, kept up a sound rate of fire, and came unhurt from the battlefield.

On another occasion a portion of a supply column was cut off by a detachment of German cavalry and the officer in charge was summoned to surrender. He refused, and starting his motors off at full speed dashed safely through, losing only two lorries.

It is noted that during the rearguard action of the Guards Brigade on September 1 the Germans were seen giving assistance to our wounded.

The weather has been very hot with an almost tropical sun, which has made the long marches trying to the soldiers.* In spite of this they look well and hearty, and the horses, in consequence of the amount of hay and oats in the fields, are in excellent condition.

In short it may be said that the war so far as it has advanced has given most promising opportunities of adding to the reputation of the British arms and of achieving notable and substantial successes; but we must have more men so as to operate on a scale proportionate to the strength and power of the Empire.

[* For the first time in its history the British Army was fighting without either ceremonial head-dress or wearing the tropical helmet which is usually so indispensable a part of the British soldier's equipment. The army fought and is still fighting in its caps, and in the hot weather to which the despatch refers these were supplemented by a piece of khaki cloth hanging from the back of the cap and designed to protect the nape of the neck.]

September 17, 1914.

MY LORD,

In continuation of my despatch of September 7, I have the honour to report the further progress of the operations of the forces under my command from August 28.

On that evening the retirement of the force was followed closely by two of the enemy's cavalry columns, moving south-east from St. Quentin.

The retreat in this part of the field was being covered by the 3rd and 5th Cavalry Brigades. South of the Somme General Gough, with the 3rd Cavalry Brigade, threw back the Uhlans of the Guard with considerable loss.

General Chetwode, with the 5th Cavalry Brigade, encountered the eastern column near Cerizy, moving south. The Brigade attacked and routed the column, the leading German regiment suffering very severe casualties and being almost broken up.

The 7th French Army Corps was now in course of being railed up from the south to the east of Amiens. On the 29th it nearly completed its detrainment, and the French 6th Army got into position on my left, its right resting on Roye.

The 5th French Army was behind the line of the Oise between La Fère and Guise.

The pursuit of the enemy was very vigorous; some five or six German corps were on the Somme, facing the 5th Army on the Oise. At least two corps were advancing towards my front, and were crossing the Somme east and west of Ham. Three or four more German corps were opposing the 6th French Army on my left.

This was the situation at one o'clock on the 29th, when I received a visit from General Joffre at my headquarters.

I strongly represented my position to the French Commander-in-Chief, who was most kind, cordial, and sympathetic, as he has always been. He told me that he had directed the 5th French Army on the Oise to move forward and attack the Germans on the Somme, with a view to checking pursuit. He also told me of the formation of the 6th French Army on my left flank, composed of the 7th Army Corps, four reserve divisions, and Sordfit's corps of cavalry.

I finally arranged with General Joffre to effect a further short retirement towards the line Compiègne-Soissons, promising him, however, to do my utmost to keep always within a day's march of him.

In pursuance of this arrangement the British forces retired to a position a few miles north of the line Compiègne-Soissons on the 29th.

The right flank of the German Army was now reaching a point which appeared seriously to endanger my line of communications with Havre. I had already evacuated Amiens, into which place a German reserve division was reported to have moved.

Orders were given to change the base to St. Nazaire, and establish an advance base at Le Mans. This operation was well carried out by the Inspector-General of Communications.

In spite of a severe defeat inflicted upon the Guard 10th and Guard Reserve Corps of the German Army by the 1st and 3rd French Corps on the right of the 5th Army, it was not part of General Joffre's plan to pursue this advantage, and a general retirement on to the line of the Marne was ordered, to which the French forces in the more eastern theatre were directed to conform.

A new army (the 9th) has been formed from three corps in the south by General Joffre, and moved into the space between the right of the 5th and left of the 4th Armies.

Whilst closely adhering to his strategic conception to draw the enemy on at all points until a favourable situation was created from which to assume the offensive, General Joffre found it necessary to modify from day to day the methods by which he sought to attain this object, owing to the development of the enemy's plans and changes in the general situation.

In conformity with the movements of the French forces, my retirement continued practically from day to day. Although we were not severely pressed by the enemy, rearguard actions took place continually.

On September 1, when retiring from the thickly wooded country to the south of Compiègne, the 1st Cavalry Brigade was overtaken by some German cavalry. They momentarily lost a horse artillery battery, and several officers and men were killed and wounded. With the help, however, of some detachments from the 3rd Corps operating on their left, they not only recovered their own guns, but succeeded in capturing twelve of the enemy's.

Similarly, to the eastward, the 1st Corps, retiring south, also got into some very difficult forest country, and a somewhat severe rearguard action ensued at Villers-Cotterets, in which the 4th Guards Brigade suffered considerably.

On September 3 the British forces were in position south of the Marne between Lagny and Signy-Signets. Up to this time I had been requested by General Joffre to defend the passages of the river as long as possible, and to blow up the bridges in my front. After I had made the necessary dispositions, and the destruction of the bridges had been effected, I was asked by the French Commander-in-Chief to continue my retirement to a point some twelve miles in rear of the position I then occupied, with a view to taking up a second position behind the Seine. This retirement was duly carried out. In the meantime the enemy had thrown bridges and crossed the Marne in considerable force, and was threatening the Allies all along the line of the British forces and the 5th and 9th French Armies. Consequently several small outpost actions took place.

On Saturday, September 5, I met the French Commander-in-Chief at his request, and he informed me of his intention to take the offensive forthwith, as he considered conditions were very favourable to success.

General Joffre announced to me his intention of wheeling up the left flank of the 6th Army, pivoting on the Marne, and directing it to move on the Ourcq; cross and attack the flank of the 1st German Army, which was then moving in a south-easterly direction east of that river.

He requested me to effect a change of front to my right—my left resting on the Marne and my right on the 5th Army—to fill the gap between that army and the 6th. I was then to advance against the enemy in my front and join in the general offensive movement.

These combined movements practically commenced on Sunday, September 6, at sunrise; and on that day it may be said that a great battle opened on a front extending from Ermenonville, which was just in front of the left flank of the 6th French Army, through Lizy on the Marne, Mauperthuis, which was about the British centre, Courtecon, which was the left of the 5th French Army, to Estemay and Charleville, the left of the 9th Army under General Foch, and so along the front of the 9th, 4th, and 3rd French Armies to a point north of the fortress of Verdun.

This battle, in so far as the 6th French Army, the British Army, the 5th French Army, and the 9th French Army were concerned, may be said to have concluded on the evening of September 10, by which time the Germans had been driven back to the line Soissons-Reims, with a loss of thousands of prisoners, many guns, and enormous masses of transport.

About September 3 the enemy appears to have changed his plans and to have determined to stop his advance south direct upon Paris, for on September 4 air reconnaissances showed that his main columns were moving in a south-easterly direction generally east of a line drawn through Nanteuil and Lizy on the Ourcq.

On September 5 several of these columns were observed to have crossed the Marne; whilst German troops, which were observed moving south-east up the left bank of the Ourcq on the 4th, were now reported to be halted and facing that river. Heads of the enemy's columns were seen crossing at Changis, La Ferté, Nogent, Chateau-Thierry, and Mezy.

Considerable German columns of all arms were seen to be converging on Montmirail, whilst before sunset large bivouacs of the enemy were located in the neighbourhood of Coulommiers, south of Rebais, La Ferté-Gaucher and Dagny.

I should conceive it to have been about noon on September 6, after the British forces had changed their front to the right and occupied the line Jouy-le Chatel-Faremoutiers-Villeneuve le Comte, and the advance of the 6th French Army north of the Marne towards the Ourcq became apparent, that the enemy realized the powerful threat that was being made against the flank of his columns moving south-east, and began the great retreat which opened the battle above referred to.

On the evening of September 6, therefore, the fronts and positions of the opposing armies were, roughly, as follows—

ALLIES.

6th French Army.—Right on the Marne at Meux, left

towards

Betz.

British Forces.—On the line Dagny-Coulommiers-Maison.

5th French Army.—At Courtagon, right on Estemay.

Conneau's Cavalry Corps.—Between the right of the British and the left

of

the French 5th Army.

GERMANS.

4th Reserve and 2nd Corps.—East of the Ourcq and facing

that river.

9th Cavalry Division.—West of Crecy.

2nd Cavalry Division.—North of Coulommiers.

4th Corps.—Rebais.

3rd and 7th Corps.—South-west of Montmirail.

All these troops constituted the 1st German Army, which was directed against the French 6th Army on the Ourcq, and the British forces, and the left of the 5th French Army south of the Marne.

The 2nd German Army (IX, X, X.R. and Guard) was moving against the centre and right of the 5th French Army and the 9th French Army.

On September 7 both the 5th and 6th French Armies were heavily engaged on our flank. The 2nd and 4th Reserve German Corps on the Ourcq vigorously opposed the advance of the French towards that river, but did not prevent the 6th Army from gaining some headway, the Germans themselves suffering serious losses. The French 5th Army threw the enemy back to the line of the Petit Morin River, after inflicting severe losses upon them, especially about Montceaux, which was carried at the point of the bayonet.

The enemy retreated before our advance, covered by his 2nd and 9th and Guard Cavalry Divisions, which suffered severely.

Our cavalry acted with great vigour, especially General De Lisle's Brigade, with the 9th Lancers and 18th Hussars.

On September 8 the enemy continued his retreat northward, and our army was successfully engaged during the day with strong rearguards of all arms on the Petit Morin River, thereby materially assisting the progress of the French Armies on our right and left, against whom the enemy was making his greatest efforts. On both sides the enemy was thrown back with heavy loss. The First Army Corps encountered stubborn resistance at La Trétoire (north of Rebais). The enemy occupied a strong position with infantry and guns on the northern bank of the Petit Morin River; they were dislodged with considerable loss. Several machine guns and many prisoners were captured, and upwards of 200 German dead were left on the ground.

The forcing of the Petit Morin at this point was much assisted by the cavalry and the 1st Division, which crossed higher up the stream.

Later in the day a counter-attack by the enemy was well repulsed by the 1st Army Corps, a great many prisoners and some guns again falling into our hands.

On this day (September 8) the 2nd Army Corps encountered considerable opposition, but drove back the enemy at all points with great loss, making considerable captures.

The 3rd Army Corps also drove back considerable bodies of the enemy's infantry and made some captures.

On September 9 the 1st and 2nd Army Corps forced the passage of the Marne and advanced some miles to the north of it. The 3rd Corps encountered considerable opposition, as the bridge at La Ferté was destroyed and the enemy held the town on the opposite bank in some strength, and thence persistently obstructed the construction of a bridge; so the passage was not effected until after nightfall.

During the day's pursuit the enemy suffered heavy loss in killed and wounded, some hundreds of prisoners fell into our hands, and a battery of eight machine guns was captured by the 2nd Division.

On this day the 6th French Army was heavily engaged west of the River Ourcq. The enemy had largely increased his force opposing them, and very heavy fighting ensued, in which the French were successful throughout.

The left of the 5th French Army reached the neighbourhood of Chateau-Thierry after the most severe fighting, having driven the enemy completely north of the river with great loss.

The fighting of this army in the neighbourhood of Montmirail was very severe.

The advance was resumed at daybreak on the 10th up to the line of the Ourcq, opposed by strong rearguards of all arms. The 1st and 2nd Corps, assisted by the Cavalry Division on the right, the 3rd and 5th Cavalry Brigades on the left, drove the enemy northwards. Thirteen guns, seven machine guns, about 2000 prisoners, and quantities of transport fell into our hands. The enemy left many dead on the field. On this day the French 5th and 6th Armies had little opposition.

As the 1st and 2nd German Armies were now in full retreat, this evening marks the end of the battle which practically commenced on the morning of the 6th instant, and it is at this point in the operations that I am concluding the present despatch.

Although I deeply regret to have had to report heavy losses in killed and wounded throughout these operations, I do not think they have been excessive in view of the magnitude of the great fight, the outlines of which I have only been able very briefly to describe, and the demoralization and loss in killed and wounded which are known to have been caused to the enemy by the vigour and severity of the pursuit.

In concluding this despatch I must call your lordship's special attention to the fact that from Sunday, August 23, up to the present date (September 17), from Mons back almost to the Seine, and from the Seine to the Aisne, the Army under my command has been ceaselessly engaged without one single day's halt or rest of any kind.

Since the date to which in this despatch I have limited my report of the operations, a great battle on the Aisne has been proceeding. A full report of this battle will be made in an early further despatch.

It will, however, be of interest to say here that, in spite of a very determined resistance on the part of the enemy, who is holding in strength and great tenacity a position peculiarly favourable to defence, the battle which commenced on the evening of the 12th inst. has, so far, forced the enemy back from his first position, secured the passage of the river, and inflicted great loss upon him, including the capture of over 2000 prisoners and several guns.

I have the honour to be,

Your Lordship's most obedient Servant, (Signed) J.D.P. French, Field- Marshal,

Commander-in-Chief,

British Forces in the Field.

ON Friday, September 4, it became apparent that there was an alteration in the direction of advance of almost the whole of the 1st German Army. That Army since the battle near Mons on August 23 had been playing its part in the colossal strategic endeavour to create a Sedan for the Allies by outflanking and enveloping the left of their whole line so as to encircle and drive both British and French to the south.

There was now a change in its objective; and it was observed that the German forces opposite the British were beginning to move in a southeasterly direction instead of continuing southwest on to the Capital.

Leaving a strong rearguard along the line of the River Ourcq (which flows south and joins the Marne at Lizy-sur-Ourcq) to keep off the French 6th Army, which by then had been formed and was to the north-west of Paris, they were evidently executing what amounted to a flank march diagonally across our front. Prepared to ignore the British, as being driven out of the fight, they were initiating an effort to attack the left flank of the French main army which stretched in a long curved line from our right towards the east, and so to carry out against it alone the envelopment which had so far failed against the combined forces of the Allies.

On Saturday, the 5th, this movement on the part of the Germans was continued, and large advanced parties crossed the Marne southwards at Trilport, Sammeroy. La Ferté-sous-Jouarre and Chateau-Thierry. There was considerable fighting with the French 5th Army on the French left, which fell back from its position south of the Marne towards the Seine. On Sunday large hostile forces crossed the Marne, and pushed on through Coulommiers past the British right. Further east they were attacked at night by the French 5th Army, which captured three villages at the point of the bayonet.

An earlier despatch from headquarters gave the following particulars, which are amplified in the above account.

On September 6 the southward advance of the German right reached its extreme points at Coulommiers and Provins, cavalry patrols having penetrated even as far south as Nogent-sur-Seine. This movement was covered by a large flanking force west of the line of the River Ourcq, watching the outer Paris defences and any Allied force that might issue from them. The southward movement of the enemy left his right wing in a dangerous position, as he had evacuated the Creil-Senlis-Compiègne region through which his advance had been pushed.

The Allies attacked this exposed wing both in front and flank on September 8. The covering force was assailed by a French Army based upon the Paris defences, and brought to action on the line Nanteuil-le Haudouin-Meaux. The main portion of the enemy's right wing was attacked frontally by the British Army, which had been transferred from the North to the East of Paris, and by French Corps advancing alongside of it on the line Crécy-Coulommiers-Sézanne.

The combined operations have up to the present been completely successful. The German outer flank was forced back as far as the line of the Ourcq. There it made a strong defence, and executed several vigorous counter-attacks, but was unable to beat off the pressure of the French advance. The main body of the enemy's right wing vainly endeavoured to defend the line of the Grand Morin River, and then that of the Petit Morin.

Pressed back over both of these rivers and threatened on its right owing to the defeat of the covering force by the Allied left, the German right wing retreated over the Marne on September 10. The British Army, with a portion of the French forces on its left, crossed this river below Chateau-Thierry, a movement which obliged the enemy's forces west of the Ourcq, already assailed by the French corps forming the extreme left of the Allies, to give way and to retreat north-eastwards in the direction of Soissons.

Since the 10th the whole of the German right wing has fallen back in considerable disorder, closely followed by the French and British troops. Six thousand prisoners and fifteen guns were captured on the 10th and 11th, and the enemy is reported to be continuing his retirement rapidly over the Aisne, evacuating the Soissons region. The British cavalry is reported to-day to be at Fismes, not far from Reims.

While the German right wing has thus been driven back and thrown into disorder, the French armies further to the east have been strongly engaged with the German centre, which had pushed forward as far as Vitry. Between the 8th and 10th our Allies were unable to make much impression west of Vitry.

On the 11th, however, this portion of the German Army began to give way, and eventually abandoned Vitry, where the enemy's line of battle was forming a salient under the impulse of French troops between the upper Marne and the Meuse. The French troops are following up the enemy and are driving portion of his forces northwards towards the Argonne forest country.

The 3rd French Army reports to-day that it has captured the entire artillery of a hostile army corps—a capture which probably represents about 160 guns. The enemy is thus in retreat along the whole line west of the Meuse and has suffered gravely in moral, besides encountering heavy losses in personnel and material.

On Monday, September 7, there was a general advance on the part of the Allies in this quarter of the field. Our forces, which had by now been reinforced, pushed on in a northeasterly direction, in co-operation with an advance of the French 5th Army to the north and of the French 6th Army eastwards, against the German rearguard along the Ourcq.

Possibly weakened by the detachment of troops to the eastern theatre of operations, and realizing that the action of the French 6th Army against the line of the Ourcq and the advance of the British placed their own flanking movement in considerable danger of being taken in rear and on its right flank, the Germans on this day commenced to retire towards the north-east. This was the first time that these troops had turned back since their attack at Mons a fortnight before, and, from reports received, the order to retreat when so close to Paris was a bitter disappointment. From letters found on the dead there is no doubt that there was a general impression amongst the enemy's troops that they were about to enter Paris.

On Tuesday, September 8th, the German movement north-eastwards was continued, their rearguards on the south of the Marne being pressed back to that river by our troops and by the French on our right, the latter capturing three villages after a hand-to-hand fight and the infliction of severe loss on the enemy.

The fighting along the Ourcq continued on this day and was of the most sanguinary character, for the Germans had massed a great force of artillery along this line. Very few of their infantry were seen by the French. The French 5th Army also made a fierce attack on the Germans in Montmirail, regaining that place.

On Wednesday, the 9th, the battle between the French 6th Army and what was now the German flank guard along the Ourcq continued. The British Corps, overcoming some resistance on the River Petit Morin, crossed the Marne in pursuit of the Germans, who were now hastily retreating northwards. One of our corps was delayed by an obstinate defence made by a strong rearguard with machine guns at La Ferté-sous-Jouarre, where the bridge had been destroyed.

On Thursday, September 10, the French 6th Army continued its pressure on the west while the 5th Army, by forced marches, reached the line Chateau-Thierry-Dormans on the Marne. Our troops also continued the pursuit on the north of the latter river, and after a considerable amount of fighting captured some 1500 prisoners, four guns, six machine guns, and 50 transport wagons.

Many of the enemy were killed and wounded, and the numerous thick woods which dot the country north of the Marne are filled with German stragglers. Most of them appear to have been without food for at least two days. Indeed, in this area of operations the Germans seem to be demoralized and inclined to surrender in small parties, and the general situation appears to be most favourable to the Allies.

Much brutal and senseless damage has been done in the villages occupied by the enemy. Property has been wantonly destroyed, pictures in the chateaux have been ripped up, and the houses generally pillaged. It is stated on unimpeachable authority, also, that the inhabitants have been much ill-treated.

Interesting incidents have occurred during the fighting. On the 10th part of our 2nd Army Corps advancing north found itself marching parallel with another infantry force at some little distance away. At first it was thought that this was another British unit. After some time, however, it was discovered that it was a body of Germans retreating. Measures were promptly taken to head off the enemy, who were surrounded and trapped in a sunken road, where over 400 men surrendered.

On the 10th a small party of French under a non-commissioned officer was cut off and surrounded. After a desperate resistance it was decided to go on fighting to the end. Finally the N.C.O. and one man only were left, both being wounded. The Germans came up and shouted to them to lay down their arms. The German commander, however, signed to them to keep their arms, and asked for permission to shake hands with the wounded non-commissioned officer, who was carried off on his stretcher with his rifle by his side.

The arrival of the reinforcements and the continued advance have delighted the troops, who are full of zeal and anxious to press on.

Quite one of the features of the campaign, on our side, has been the success attained by the Royal Flying Corps. In regard to the collection of information it is impossible either to award too much praise to our aviators for the way they have carried out their duties or to over-estimate the value of the intelligence collected, more especially during the recent advance.

In due course, certain examples of what has been effected may be specified and the far-reaching nature of the results fully explained, but that time has not yet arrived. That the services of our Flying Corps, which has really been on trial, are fully appreciated by our Allies is shown by the following message from the Commander-in-Chief of the French Armies received on the night of September 9 by Field-Marshal Sir John French—

"Please express most particularly to Marshal French my thanks for services rendered on every day by the English Flying Corps. The precision, exactitude, and regularity of the news brought in by its members are evidence of their prefect organization and also of the perfect training of pilots and observers."

To give a rough idea of the amount of work carried out it is sufficient to mention that, during a period of 20 days up to September 10, a daily average of more than nine reconnaissance flights of over 100 miles each has been maintained.*

[* The value of the Flying Arm of the Army owes much to the indefatigable attention paid to it by Colonel Seely when Secretary of State for War. Colonel Seely, himself an experienced pilot, did more than any other member to create an efficient air-service. Though the editor holds other political views than those Colonel Seely represents he feels that it would be unjust to withhold credit from the Minister of War.]

The constant object of our aviators has been to effect the accurate location of the enemy's forces, and, incidentally—since the operations cover so large an area—of our own units. Nevertheless, the tactics adopted for dealing with hostile aircraft are to attack them instantly with one or more British machines.

This has been so far successful that in five cases German pilots or observers have been shot in the air and their machines brought to the ground. As a consequence, the British Flying Corps has succeeded in establishing an individual ascendancy which is as serviceable to us as it is damaging to the enemy. How far it is due to this cause it is not possible at present to ascertain definitely, but the fact remains that the enemy have recently become much less enterprising in their flights. Something in the direction of the mastery of the air has already been gained.

In pursuance of the principle that the main object of military aviators is the collection of information, bomb-dropping has not been indulged in to any great extent. On one occasion a petrol bomb was successfully exploded in a German bivouac at night, while, from a diary found on a dead German cavalry soldier, it has been discovered that a high explosive bomb thrown at a cavalry column from one of our aeroplanes struck an ammunition wagon. The resulting explosion killed 15 of the enemy.

[This despatch, with the official notes by "Eye-Witness" on the Headquarters Staff, covers by far the most important period of the campaign to date, for although fighting of a yet more determined character was subsequently seen, undoubtedly the moment which inspired hope in every heart was in that fateful day when the Allies assumed the offensive and began to press back their pursuer.

Whilst the despatch is very lucid on most points it lacks—naturally enough in an official document—that atmosphere which communicates to the reader something of that exhilaration which all sections of the Allied Armies must have felt when it became clear that at last the retirement had ended and the offensive movement against the enemy had begun.

The advance was not general, nor was it made without terrific opposition. The lines rocked before they buckled, and in some places, notably in the centre, terrible encounters were of hourly occurrence. Ground was won stubbornly foot by foot, and the advancing hosts of Germany, flushed with triumph and with Paris in sight, did not give ground without great slaughter. They were strongly armed by success, heedless of danger, scornful of failure. They were, too, in sight of their goal and were not lightly to be turned from their supreme triumph.

The human element must always be taken into account when weighing cause and effect, and if the Germans marched like machines and fought like machines, they thought and hoped like men. Every letter taken from the dead was full of faith and confidence. Paris lay open to them—they anticipated an entry on the day they were turned back.

Remembering this factor and remembering too how they had, as far as they knew, driven back the whole Anglo-French Army before them, it is not difficult to understand with what bewilderment and rage they felt themselves slipping from their foothold and from being pursuers became the pursued.—EDITOR.]

General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien. With the Expeditionary Force

October 8, 1914.

MY LORD,

I have the honour to report the operations in which the British forces in France have been engaged since the evening of September 10.

1. In the early morning of the 11th the further pursuit of the enemy was commenced, and the three corps crossed the Ourcq practically unopposed, the cavalry reaching the line of the Aisne River; the 3rd and 5th Brigades south of Soissons, the 1st, 2nd, and 4th on the high ground at Couvrelles and Cerseuil.

On the afternoon of the 12th from the opposition encountered by the 6th French Army to the west of Soissons, by the 3rd Corps south-east of that place, by the 2nd Corps south of Missy and Vailly, and certain indications all along the line, I formed the opinion that the enemy had, for the moment at any rate, arrested his retreat, and was preparing to dispute the passage of the Aisne with some vigour.

South of Soissons the Germans were holding Mont de Paris against the attack of the right of the 6th French Army when the 3rd Corps reached the neighbourhood of Buzancy, south-east of that place. With the assistance of the artillery of the 3rd Corps the French drove them back across the river at Soissons, where they destroyed the bridges.

The heavy artillery fire which was visible for several miles in a westerly direction in the valley of the Aisne showed that the 6th French Army was meeting with strong opposition all along the line.

On this day the cavalry under General Allenby reached the neighbourhood of Braine, and did good work in clearing the town and the high ground beyond it of strong hostile detachments. The Queen's Bays are particularly mentioned by the General as having assisted greatly in the success of this operation. They were well supported by the 3rd Division, which on this night bivouacked at Brenelle, south of the river.

The 5th Division approached Missy, but were unable to make headway.*

[* This would be one of the new Divisions which were sent to France to reinforce the army.]

The 1st Army Corps reached the neighbourhood of Vauxcéré without much opposition.

In this manner the battle of the Aisne commenced.

2. The Aisne Valley runs generally east and west, and consists of a flat- bottomed depression of width varying from half a mile to two miles, down which the river follows a winding course to the west at some points near the southern slopes of the valley and at others near the northern. The high ground both on the north and south of the river is approximately 400 ft. above the bottom of the valley, and is very similar in character, as are both slopes of the valley itself, which are broken into numerous rounded spurs and reentrants. The most prominent of the former are the Chivre spur on the right bank and Sermoise spur on the left. Near the latter place the general plateau on the south is divided by a subsidiary valley of much the same character, down which the small River Vesle flows to the main stream near Sermoise. The slopes of the plateau overlooking the Aisne on the north and south are of varying steepness, and are covered with numerous patches of wood, which also stretch upwards and backwards over the edge on to the top of the high ground. There are several villages and small towns dotted about in the valley itself and along its sides, the chief of which is the town of Soissons.

The Aisne is a sluggish stream of some 170 ft. in breadth, but, being 15 ft. deep in the centre, it is unfordable. Between Soissons on the west and Villers on the east (the part of the river attacked and secured by the British forces) there are eleven road bridges across it. On the north bank a narrow-gauge railway runs from Soissons to Vailly, where it crosses the river and continues eastward along the south bank. From Soissons to Sermoise a double line of railway runs along the south bank, turning at the latter place up the Vesle Valley towards Bazoches.

The position held by the enemy is a very strong one, either for a delaying action or for a defensive battle. One of its chief military characteristics is that from the high ground on neither side can the top of the plateau on the other side be seen except for small stretches. This is chiefly due to the woods on the edges of the slopes. Another important point is that all the bridges are under either direct or high-angle artillery fire.

The tract of country above described, which lies north of the Aisne, is well adapted to concealment, and was so skilfully turned to account by the enemy as to render it impossible to judge the real nature of his opposition to our passage of the river, or to accurately gauge his strength; but I have every reason to conclude that strong rearguards of at least three army corps were holding the passages on the early morning of the 13th.

3. On that morning I ordered the British forces to advance and make good the Aisne.*

[* To establish themselves on the furthermost bank.]

The 1st Corps and the cavalry advanced on the river. The 1st Division was directed on Chanouille, via the canal bridge at Bourg, and the 2nd Division on Courtecon and Presles, via Pont-Arcy and on the canal to the north of Braye, via Chavonne. On the right the cavalry and 1st Division met with slight opposition, and found a passage by means of the canal which crosses the river by an aqueduct. The Division was, therefore, able to press on, supported by the Cavalry Division on its outer flank, driving back the enemy in front of it.

On the left the leading troops of the 2nd Division reached the river by nine o'clock. The 5th Infantry Brigade were only enabled to cross, in single file and under considerable shell fire, by means of the broken girder of the bridge which was not entirely submerged in the river. The construction of a pontoon bridge was at once undertaken, and was completed by five o'clock in the afternoon.

On the extreme left the 4th Guards Brigade met with severe opposition at Chavonne, and it was only late in the afternoon that it was able to establish a foothold on the northern bank of the river by ferrying one battalion across in boats.

By nightfall the 1st Division occupied the area Moulins-Paissy-Geny, with posts in the village of Vendresse.

The 2nd Division bivouacked as a whole on the southern bank of the river, leaving only the 5th Brigade on the north bank to establish a bridge head.

The 2nd Corps found all the bridges in front of them destroyed, except that of Condé, which was in possession of the enemy, and remained so until the end of the battle.

In the approach to Missy, where the 5th Division eventually crossed, there is some open ground which was swept by heavy fire from the opposite bank. The 13th Brigade was, therefore, unable to advance; but the 14th, which was directed to the east of Venizel at a less exposed point, was rafted across, and by night established itself with its left at St. Marguerite. They were followed by the 15th Brigade, and later on both the 14th and 15th supported the 4th Division on their left in repelling a heavy counter-attack on the 3rd Corps.

On the morning of the 13th the 3rd Corps found the enemy had established himself in strength on the Vregny Plateau. The road bridge at Venizel was repaired during the morning, and a reconnaissance was made with a view to throwing a pontoon bridge at Soissons.