Introduction — After the Deadlock on the Aisne

Chapter I. — The Move to the North

The Fourth Despatch: Ypres-Armentières

Chapter II. — The Struggle for the Coast

The New Field of Battle—Typical Warfare—How the British Came North—How the Great Battle Began—Bridging the Dykes—How the Dorsets held Pont Fixe—A Murderous Battle in the Dark.

Chapter III. — The Long Thin Khaki Line

The Royal Irish at Le Pilly—Increased Violence of Battle—Trench Warfare- -"Holding on"—The British at Antwerp—How the 4th Corps came into Existence— Why the Germans Wanted Calais—Germans Occupy Ostend—How the Belgians Fought— A Battle on Land, Sea, and in the Air—Sir John French's Daring Decision—The Memorable Battle for Ypres.

Chapter IV. — Great Deeds That Made an Undying Story

The Work of the 1st Corps—Pulteney's Advance—Gallant Regiments—The Story of the Royal West Kents—Five Days' Fight at Neuve Chapelle—Critical Days— London Scottish—The Worcestershires' Great Fight—Realistic Description of Fighting—The Defeat of the Prussian Guard.

Appendix: The Naval Division at Antwerp

The Standard History of the War, Vol. II, George Newnes, Ltd., London, 1915

THE fourth despatch of Field-Marshal Sir John French, dealing with the operations of the army under his command from the time the British forces left the trenches on the Aisne, and took up new positions in Northern France and in Flanders, is necessarily a crowded one, filled with stories of surprising and absorbing interest. "The deeds of the troops in these days," Sir John French has said, "will furnish some of the most brilliant chapters which will be found in the military history of our time." For many days the left flank of the Armies was in an exceedingly critical condition, and it is easy to see from the despatches how near the Germans were to establishing themselves on the northern coast of France.

Such was the magnitude of the operations, however, that the Commander-in- Chief is obliged to dismiss in a few lines actions which in other times would have been given far more prominence.

As it is they will live in history as glorious and memorable achievements. "No more arduous task," Sir John French has testified "has ever been assigned to British soldiers, and in all their splendid history there is no instance of their having answered so magnificently to the desperate calls which of necessity were made upon them."

I propose in this volume to give in full the memorable despatch, and, because of the necessary brevity with which it deals with great and important events and heroic struggles, I shall devote the rest of the volume to setting out more fully the great story which is only outlined in Sir John French's despatch. From its official nature, the despatch omits, of necessity, a mass of information which has reached us in other ways in incomplete, fragmentary, and disconnected forms. In supplying this descriptive matter, in filling in the wonderful story of marches and counter marches, of strategical and tactical manoeuvres, in telling of the great combats which took place, and of the regimental and individual acts of heroism, I hope to get these great events into some kind of perspective, and to present a connected story of how the glorious work was accomplished.

It was a delicate operation to withdraw the British forces from their position on the Aisne (where we left them at the conclusion of the previous volume) and transfer them to new positions a long way off in Northern France and Flanders. The prolonged battle of Ypres-Armentières, or the battle for the coast, as it has sometimes been called, was a development of the continuous struggle which commenced on the Aisne after the Great German Retreat from Paris. After weeks of continual stalemate, when neither side could move the other from strong entrenched positions, the efforts of the Allies and Germans alike were directed to attempting to outflank each other. There came a time on the Aisne when General Sir John French made up his mind that he would force events elsewhere.

It was on October 3rd that Field-Marshal Sir John French began the series of operations which had for its object the moving of his army from the position it held on the Aisne to the northernmost part of France. The object of the German commander had become clear; from necessity he had to extend his line northward to preserve his right flank from the threatening Allies. They made a virtue of that necessity by moving large bodies of troops in the direction of the coast. General Joffre was endeavouring to bring his troops in order to outflank the enemy and to drive him in upon his own interior lines. It is at this point that the despatch of Sir John French, with the contents of which this volume deals, begins. The full text of the Commander-in-Chief's official account of events follows.

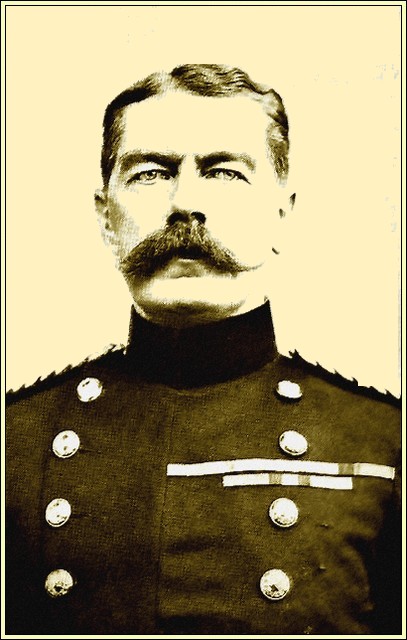

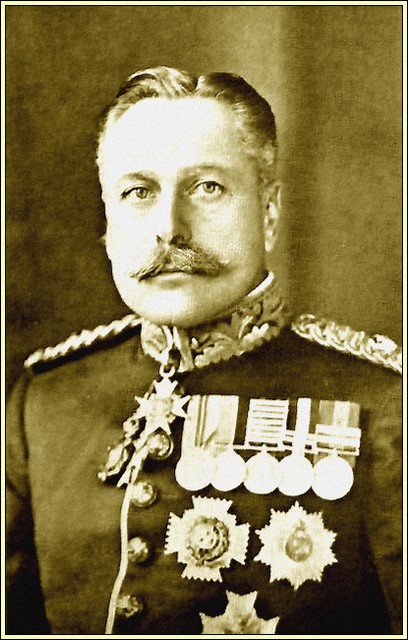

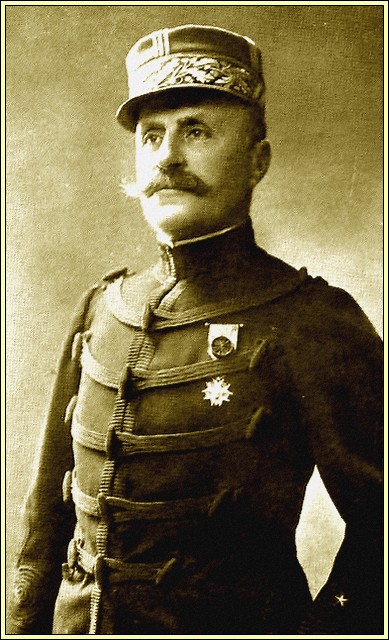

Lord Kitchener of Khartoum, Secretary of State for War.

(From Field-Marshal Sir John French)

RECEIVED by the Secretary of State for War from the Field- Marshal Commanding- in-Chief British Forces in the Field:—

General Headquarters, November 20, 1914.

MY LORD,

1. I have the honour to submit a further despatch recounting the operations of the Field Force under my command throughout the battle of Ypres- Armentières.

Early in October a study of the general situation strongly impressed me with the necessity of bringing the greatest possible force to bear in support of the northern flank of the Allies, in order effectively to outflank the enemy and compel him to evacuate his positions.

At the same time the position on the Aisne, as described in the concluding paragraphs of my last despatch, appeared to me to warrant a withdrawal of the British Forces from the positions they then held.

The enemy had been weakened by continual abortive and futile attacks, while the fortification of the position had been much improved.

I represented these views to General Joffre, who fully agreed.

Arrangements for withdrawal and relief having been made by the French General Staff, the operation commenced on October 3; and the 2nd Cavalry Division, under General Gough, marched for Compiègne en route for the new theatre.

The Army Corps followed in succession at intervals of a few days, and the move was completed on October 19, when the 1st Corps, under Sir Douglas Haig, completed its detrainment at St. Omer.

That this delicate operation was carried out so successfully is in great measure due to the excellent feeling which exists between the French and British Armies; and I am deeply indebted to the Commander-in-Chief and the French General Staff for their cordial and most effective cooperation.

As General Foch* was appointed by the Commander-in-Chief to supervise the operations of all the French troops north of Noyon, I visited his headquarters at Doullens on October 8 and arranged joint plans of operations as follows:—

* General Foch, to whose co-operation Field-Marshal Sir John French refers in such cordial terms, was, with General Joffre, decorated with the Grand Cross of the Bath on the occasion of H.M. the King's visit to the firing- line in December, 1914.

The 2nd Corps to arrive on the line Aire-Bethune on October 11, to connect with the right of the French 10th Army and, pivoting on its left, to attack in flank the enemy who were opposing the 10th French Corps in front.

The Cavalry to move on the northern flank of the 2nd Corps and support its attack until the 3rd Corps, which was to detrain at St. Omer on the 12th, should come up. They were then to clear the front and act on the northern flank of the 3rd Corps in a similar manner, pending the arrival of the 1st Corps from the Aisne.

The 3rd Cavalry Division and 7th Division, under Sir Henry Rawlinson, which were then operating in support of the Belgian Army and assisting its withdrawal from Antwerp, to be ordered to co-operate as soon as circumstances would allow.

In the event of these movements so far overcoming the resistance of the enemy as to enable a forward movement to be made, all the Allied Forces to march in an easterly direction. The road running from Bethune to Lille was to be the dividing line between the British and French Forces, the right of the British Army being directed on Lille.

2. The great battle, which is mainly the subject of this despatch, may be said to have commenced on October 11, on which date the 2nd Cavalry Division, under General Gough, first came into contact with the enemy's cavalry who were holding some woods to the north of the Bethune-Aire Canal. These were cleared of the enemy by our cavalry, which then joined hands with the Divisional Cavalry of the 6th Division in the neighbourhood of Hazebrouck. On the same day the right of the 2nd Cavalry Division connected with the left of the 2nd Corps which was moving in a north-easterly direction after crossing the above- mentioned canal.

By October ii Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien had reached the line of the canal between Aire and Bethune. I directed him to continue his march on the 12th, bringing up his left in the direction of Merville. Then he was to move east to the Laventie-Lorgies, which would bring him on the immediate left of the French Army and threaten the German flank.*

* At this time the Germans were engaged in a fierce battle with the French at Arras, and there were, apparently, no considerable number of troops available for the extension of the enemy line. But leaving von Kluck to hold an extended line from Soissons almost to the Argonne, first von Buelow's, then the King of Wurtemburg's, and finally the Crown Prince of Bavaria's Armies were moved northward, and it was against these latter, strengthened by certain Prussian Corps, that the British found themselves fighting.

On the 12th this movement was commenced.

The 5th Division connected up with the left of the French Army north of Annequin. They moved to the attack of the Germans who were engaged at this point with the French; but the enemy once more extended his right in some strength to meet the threat against his flank. The 3rd Division, having crossed the canal, deployed on the left of the 5th; and the whole 2nd Corps again advanced to the attack, but were unable to make much headway owing to the difficult character of the ground upon which they were operating, which was similar to that usually found in manufacturing districts and was covered with mining works, factories, buildings, etc. The ground throughout this country is remarkably flat, rendering effective artillery support very difficult.

Before nightfall, however, they had made some advance and had successfully driven back hostile counter-attacks with great loss to the enemy and destruction of some of his machine guns.

On and after October 13 the object of the General Officer Commanding the 2nd Corps was to wheel to his right, pivoting on Givenchy to get astride the La Bassée-Lille Road in the neighbourhood of Fournes, so as to threaten the right flank and rear of the enemy's position on the high ground south of La Bassée.

This position of La Bassée has throughout the battle defied all attempts at capture, either by the French or the British.

On this day Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien could make but little progress. He particularly mentions the fine fighting of the Dorsets, whose Commanding Officer, Major Roper, was killed* They suffered no fewer than 400 casualties, 130 of them being killed, but maintained all day their hold on Pont Fixe. He also refers to the gallantry of the Artillery.*

* A reference to the work of the Dorsets will be found in the accompanying narrative. The artillery has been so consistently good that there is a danger from the very level of its excellence we may be overlooking its superlative merit. From the moment the first gun was fired at Mons up to the end of the battle for the coast the Royal Regiment of Artillery accomplished marvels.

The fighting of the 2nd Corps continued throughout the 14th in the same direction. On this day the Army suffered a great loss, in that the Commander of the 3rd Division, General Hubert Hamilton, was killed.

On the 15th the 3rd Division fought splendidly, crossing the dykes, with which this country is intersected, with planks; and driving the enemy from one entrenched position to another in loop-holed villages, till at night they pushed the Germans off the Estaires-La Bassée Road and established themselves on the line Pont de Ham-Croix Barbie.

On the 16th the move was continued until the left flank of the Corps was in front of the village of Aubers, which was strongly held. This village was captured on the 17th by the 9th Infantry Brigade, and at dark on the same day the Lincolns and Royal Fusiliers carried the village of Herlies at the point of the bayonet after a fine attack, the Brigade being handled with great dash by Brigadier General Shaw.*

* A thrilling description of this fight will be found in the accompanying narrative, page 78.

At this time, to the best of our information, the 2nd Corps was believed to be opposed by the 2nd, 4th, 7th, and 9th German Cavalry Divisions, supported by several battalions of Jaegers and a part of the 14th German Corps.

On the 18th powerful counter-attacks were made by the enemy all along the front of the 2nd Corps, and were most gallantly repulsed; but only slight progress could be made.

From October 19 to October 31 the 2nd Corps carried on a most gallant fight in defence of their position against very superior numbers, the enemy having being reinforced during that time by at least one Division of the 7th Corps, a brigade of the 3rd Corps, and the whole of the 14th Corps, which had moved north from in front of the French 21st Corps.

On the 19th the Royal Irish Regiment, under Major Daniell, stormed and carried the village of Le Pilly, which they held and entrenched. On the 20th, however, they were cut off and surrounded, suffering heavy losses.

On the morning of the 22nd the enemy made a very determined attack on the 5th Division, who were driven out of the village of Violaines, but they were sharply counter-attacked by the Worcesters and Manchesters, and prevented from coming on.*

* The work of these two regiments has been uniformly excellent, and a further exploit of the Worcesters will be found on page 138.

The left of the 2nd Corps being now somewhat exposed, Sir Horace Smith- Dorrien withdrew the line during the night to a position he had previously prepared, running generally from the eastern side of Givenchy, east of Neuve Chapelle to Fauquissart.

On October 24 the Lahore Division of the Indian Army Corps, under Major- General Watkis, having arrived, I sent them to the neighbourhood of Lacon to support the 2nd Corps.

Very early on this morning the enemy commenced a heavy attack, but owing to the skilful manner in which the artillery was handled and the targets presented by the enemy's infantry as it approached, they were unable to come to close quarters. Towards the evening a heavy attack developed against the 7th Brigade, which was repulsed, with very heavy loss to the enemy, by the Wiltshires and the Royal West Kents.* Later a determined attack on the 18th Infantry Brigade drove the Gordon Highlanders out of their trenches, which were retaken by the Middlesex Regiment, gallantly led by Lieutenant-Colonel Hull.

* See page 125.

The 8th Infantry Brigade (which had come into line on the left of the 2nd Corps) was also heavily attacked, but the enemy was driven off.

In both these cases the Germans lost very heavily, and left large numbers of dead and prisoners behind them.

The 2nd Corps was now becoming exhausted, owing to the constant reinforcements of the enemy, the length of line which it had to defend, and the enormous losses which it had suffered.

By the evening of October 11 the 3rd Corps had practically completed its detrainment at St. Omer, and was moved east to Hazebrouck, where the Corps remained throughout the 12th.

On the morning of the 13th the advanced guard of the Corps, consisting of the 19th Infantry Brigade and a Brigade of Field Artillery, occupied the position of the line Strazeele Station-Caestre-St. Sylvestre.

On this day I directed General Pulteney to move towards the line Armentières-Wytschaete; warning him, however, that should the 2nd Corps require his aid he must be prepared to move south-east to support it.

A French Cavalry Corps under General Conneau was operating between the 2nd and 3rd Corps.

The 4th German Cavalry Corps, supported by some Jaeger Battalions,* was known to be occupying the position in the neighbourhood of Meteren; and they were believed to be further supported by the advanced guard of another German Army Corps.

* Light Infantry Regiments.

In pursuance of his orders, General Pulteney proceeded to attack the enemy in his front.

The rain and fog which prevailed prevented full advantage being derived from our much superior artillery. The country was very much enclosed and rendered difficult by heavy rain.

The enemy were, however, routed and the position taken at dark, several prisoners being captured.

During the night the 3rd Corps made good the attacked position and entrenched it.

As Bailleul was known to be occupied by the enemy, arrangements were made during the night to attack it, but reconnaissances sent out on the morning of the 14th showed that they had withdrawn, and the town was taken by our troops at 10 a.m. on that day, many wounded Germans being found and taken in it.

The Corps then occupied the line St. Jans Cappel-Bailleul.

On the morning of the 15th the 3rd Corps were ordered to make good the line of the Lys from Armentières to Sailly, which, in the face of considerable opposition and very foggy weather, they succeeded in doing, the 6th Division at Sailly-Bac St. Maur and the 4th Division at Nieppe.

The enemy in its front having retired, the 3rd Corps on the night of the 17th occupied the line Bois Grenier-Le Gheir.

On the 18th the enemy were holding a line from Radinghem on the south, through Perenchies and Frelinghien on the north, whence the German troops which were opposing the Cavalry Corps occupied the east bank of the river as far as Wervick.

On this day I directed the 3rd Corps to move down the valley of the Lys and endeavour to assist the Cavalry Corps in making good its position on the right bank. To do this it was necessary first to drive the enemy eastward towards Lille. A vigorous offensive in the direction of Lille was assumed, but the enemy was found to have been considerably reinforced, and but little progress was made.

The situation of the 3rd Corps on the night of the 18th was as follows:—

The 6th Division was holding the line Radinghem-La Vallée- Armentières- Capinghem-Premesques Railway Line 300 yards east of Halte. The 4th Division were holding the line from L'Epinette to the river at a point 400 yards south of Frelinghien, and thence to a point half a mile south-east of Le Gheir. The Corps Reserve was at Armentières Station, with right and left flanks of Corps in close touch with French Cavalry and the Cavalry Corps.

Since the advance from Bailleul the enemy's forces in front of the Cavalry and 3rd Corps had been strongly reinforced, and on the night of the 17th they were opposed by three or four divisions of the enemy's cavalry, the 19th Saxon Corps and at least one division of the 7th Corps. Reinforcements for the enemy were known to be coming up from the direction of Lille.

Following the movements completed on October 11, the 2nd Cavalry Division pushed the enemy back through Flêtre and Le Coq de Paille, and took Mont des Cats, just before dark, after stiff fighting.*

* The Mont des Cats is one of the few eminences in this somewhat featureless country. Only the most meagre description of this fight has been placed on record. The enemy had entrenched the slopes and held both flanks of the hill# and its capture by cavalry was a notable achievement.

On the 14th the 1st Cavalry Division joined up, and the whole Cavalry Corps under General Allenby, moving north, secured the high ground above Berthen, overcoming considerable opposition.

With a view to a further advance east, I ordered General Allenby, on the 15th, to reconnoitre the line of the River Lys, and endeavour to secure the passages on the opposite bank, pending the arrival of the 3rd and 4th Corps.

During the 15th and 16th this reconnaissance was most skilfully and energetically carried out in the face of great opposition, especially along the lower line of the river.

These operations were continued throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th; but, although valuable information was gained, and strong forces of the enemy held in check, the Cavalry Corps was unable to secure passages or to establish a permanent footing on the eastern bank of the river.

At this point in the history of the operations under report it is necessary that I should return to the co-operation of the forces operating in the neighbourhood of Ghent and Antwerp under Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Rawlinson, as the action of his force about this period exercised, in my opinion, a great influence on the course of the subsequent operations.

This force, consisting of the 3rd Cavalry Division under Major-General the Hon. Julian Byng, and the 7th Division, under Major-General Capper, was placed under my orders by telegraphic instructions from your Lordship.

On receipt of these instructions I directed Sir Henry Rawlinson to continue his operations in covering and protecting the withdrawal of the Belgian Army, and subsequently to form the left column in the eastward advance of the British forces. These withdrawal operations were concluded about October 16, on which date the 7th Division was posted to the east of Ypres on a line extending from Zandvoorde through Gheluvelt to Zonnebeke. The 3rd Cavalry Division was on its left towards Langemarck and Poelcappelle.

In this position Sir Henry Rawlinson was supported by the 87th French Territorial Division in Ypres and Vlamertinghe and by the 89th French Territorial Division at Poperinghe.

On the night of the 16th I informed Sir Henry Rawlinson of the operations which were in progress by the Cavalry Corps and the 3rd Corps, and ordered him to conform to those movements in an easterly direction, keeping an eye always to any threat which might be made against him from the north-east.

A very difficult task was allotted to Sir Henry Rawlinson and his command.* Owing to the importance of keeping possession of all the ground towards the north which we already held, it was necessary for him to operate on a very wide front, and until the arrival of the 1st Corps in the northern theatre—which I expected about the 20th—I had no troops available with which to support or reinforce him.

* The circumstances which led to the formation of the 4th Corps will be found in the narrative on page 93.

Although on this extended front he had eventually to encounter very superior forces, his troops, both cavalry and infantry, fought with the utmost gallantry and rendered very signal service.

On the 17th four French Cavalry Divisions deployed on the left of the 3rd Cavalry Division and drove back advanced parties of the enemy beyond the Forêt d'Houthulst.

As described above, instructions for a vigorous attempt to establish the British Forces east of the Lys were given on the night of the 17th to the 2nd, 3rd, and Cavalry Corps.

I considered, however, that the possession of Menin constituted a very important point of passage, and would much facilitate the advance of the rest of the Army. So I directed the General Officer Commanding the 4th Corps to advance the 7th Division upon Menin and endeavour to seize that crossing on the morning of the 18th.

The left of the 7th Division was to be supported by the 3rd Cavalry Brigade and further north by the French Cavalry in the neighbourhood of Roulers.

Sir Henry Rawlinson represented to me that large hostile forces were advancing upon him from the east and north-east and that his left flank was severely threatened.

I was aware of the threats from that direction, but hoped at this particular time there was no greater force coming from the north-east than could be held off by the combined efforts of the French and British Cavalry and the Territorial troops supporting them until the passage at Menin could be seized and the 1st Corps brought up in support.

Sir Henry Rawlinson probably exercised a wise judgment in not committing his troops to this attack in their somewhat weakened condition, but the result was that the enemy's continued possession of the passage at Menin certainly facilitated his rapid reinforcement of his troops and thus rendered any further advance impracticable.

On the morning of October 20 the 7th Division and 3rd Cavalry Division had retired to their old position extending from Zandvoorde through Kruiseik and Gheluvelt to Zonnebeke.

On October 19 the 1st Corps, coming from the Aisne, had completed its detrainment and was concentrated between St. Omer and Hazebrouck.

A question of vital importance now arose for decision.

I knew that the enemy were by this time in greatly superior strength on the Lys, and that the 2nd, 3rd, Cavalry, and 4th Corps were holding a much wider front than their numbers and strength warranted.

Taking these facts alone into consideration, it would have appeared wise to throw the 1st Corps in to strengthen the line, but this would have left the country north and east of Ypres and the Ypres Canal open to a wide turning movement by the 3rd Reserve Corps and at least one Landwehr Division which I knew to be operating in that region. I was also aware that the enemy was bringing large reinforcements up from the East which could only be opposed for several days by two or three French Cavalry Divisions, some French Territorial troops, and the Belgian Army.

After the hard fighting it had undergone the Belgian Army was in no condition to withstand, unsupported, such an attack; and unless some substantial resistance could be offered to this threatened turning movement, the Allied flank must be turned and the Channel Ports laid bare to the enemy.

I judged that a successful movement of this kind would be fraught with such disastrous consequences that the risk of operating on so extended a front must be undertaken; and I directed Sir Douglas Haig to move with the 1st Corps to the north of Ypres.

From the best information at my disposal I judged at this time that the considerable reinforcements which the enemy had undoubtedly brought up during the 16th, 17th, and 18th, had been directed principally on the line of the Lys and against the 2nd Corps at La Bassée; and that Sir Douglas Haig would probably not be opposed north of Ypres by much more than the 3rd Reserve Corps, which I knew to have suffered considerably in its previous operations, and perhaps one or two Landwehr Divisions.*

* Throughout the campaign after the first onslaught, Field-Marshal French has been very well informed by his scouts and "agents" as to the disposition and strength of the enemy.

At a personal interview with Sir Douglas Haig on the evening of October 19 I communicated the above information to him, and instructed him to advance with the 1st Corps through Ypres to Thourout. The object he was to have in view was to be the capture of Bruges and subsequently, if possible, to drive the enemy towards Ghent. In case of an unforeseen situation arising, or the enemy proving to be stronger than anticipated, he was to decide, after passing Ypres, according to the situation, whether to attack the enemy lying to the north or the hostile forces advancing from the east; I had arranged for the French Cavalry to operate on the left of the 1st Corps and the 3rd Cavalry Division, under General Byng, on its right.

The Belgian Army were rendering what assistance they could by entrenching themselves on the Ypres Canal and the Yser River; and the troops, although in the last stage of exhaustion, gallantly maintained their positions, buoyed up with the hope of substantial British and French support.*

* The battle for the coast brought out the fine staying qualities of the Belgian Army, to which a tribute is paid in the narrative.

I fully realised the difficult task which lay before us, and the onerous rôle which the British Army was called upon to fulfil.

That success has been attained, and all the enemy's desperate attempts to break through our line frustrated, is due entirely to the marvellous fighting power and the indomitable courage and tenacity of officers, non-commissioned officers, and men.

No more arduous task has ever been assigned to British soldiers; and in all their splendid history there is no instance of their having answered so magnificently to the desperate calls which of necessity were made upon them.

Having given these orders to Sir Douglas Haig, I enjoined a defensive role upon the 2nd and 3rd and Cavalry Corps, in view of the superiority of force which had accumulated in their front. As regards the 4th Corps, I directed Sir Henry Rawlinson to endeavour to conform generally to the movements of the 1st Corps.

On October 20 they reached the line from Elverdinghe to the cross-roads, one and a half miles north-west of Zonnebeke.

On the 21st the Corps was ordered to attack and take the line Poelcappelle-Passchendaele.

Sir Henry Rawlinson's Command was moving on the right of the 1st Corps, and French troops, consisting of Cavalry and Territorials, moved on their left under the orders of General Bidon.

The advance was somewhat delayed owing to the roads being blocked; but the attack progressed favourably in face of severe opposition, often necessitating the use of the bayonet.

Hearing of heavy attacks being made upon the 7th Division and the 2nd Cavalry Division on his right, Sir Douglas Haig ordered his reserve to be halted on the north-eastern outskirts of Ypres.

Although threatened by a hostile movement from the Fôret d'Houthulst, our advance was successful until about 2 o'clock in the afternoon, when the French Cavalry Corps received orders to retire west of the canal.

Owing to this and the demands made on him by the 4th Corps, Sir Douglas Haig was unable to advance beyond the line Zonnebeke-St. Julien-Langemarck- Bixschoote.

As there was reported to be congestion with French troops at Ypres, I went there on the evening of the 21st and met Sir Douglas Haig and Sir Henry Rawlinson. With them I interviewed General de Mitry, Commanding the French Cavalry, and General Bidon, Commanding the French Territorial Divisions.

They promised me that the town would at once be cleared of the troops, and that the French Territorials would immediately move out and cover the left of the flank of the 1st Corps.

I discussed the situation with the General Officers Commanding the 1st and 4th Army Corps, and told them that, in view of the unexpected reinforcements coming up of the enemy, it would probably be impossible to carry out the original role assigned to them. But I informed them that I had that day interviewed the French Commander-in-Chief, General Joffre, who told me that he was bringing up the 9th French Army Corps to Ypres, that more French troops would follow later, and that he intended—in conjunction with the Belgian troops—to drive the Germans east. General Joffre said that he would be unable to commence this movement before the 24th; and I directed the General Officers Commanding the 1st and 4th Corps to strengthen their positions as much as possible and be prepared to hold their ground for two or three days, until the French offensive movement on the north could develop.

It now became clear to me that the utmost we could do to ward off any attempts of the enemy to turn our flank to the north, or to break in from the eastward, was to maintain our present very extended front, and to hold fast our positions until French reinforcements could arrive from the south.

During the 22nd the necessity of sending support to the 4th Corps on his right somewhat hampered the General Officer Commanding the 1st Corps; but a series of attacks all along his front had been driven back during the day with heavy loss to the enemy. Late in the evening the enemy succeeded in penetrating a portion of the line held by the Cameron Highlanders north of Pilkem.

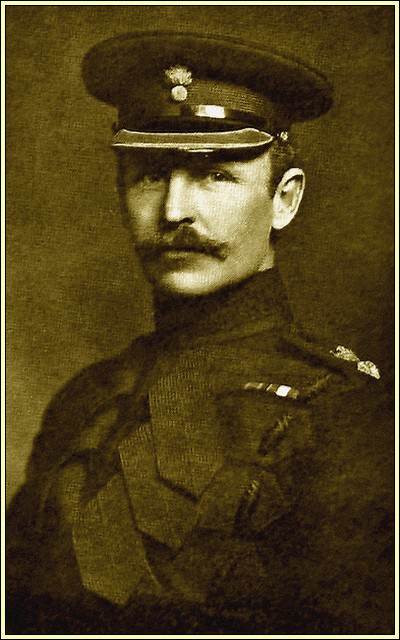

General Sir Douglas Haig.

At 6 a.m. on the morning of the 23rd a counterattack to recover the lost trenches was made by the Queen's Regiment, the Northamptons, and the King's Royal Rifles, under Major-General Bulfin. The attack was very strongly opposed and the bayonet had to be used. After severe fighting during most of the day the attack was brilliantly successful, and over six hundred prisoners were taken.*

* These three regiments have done consistently well throughout the campaign. Some idea of the pressure exerted against the Camerons may be gathered from the fact that it was necessary to send three battalions to retake the position from which they were driven by overwhelming numbers.

On the same day an attack, was made on the 3rd Infantry Brigade. The enemy advanced with great determination, but with little skill, and consequently the loss inflicted on him was exceedingly heavy; some fifteen hundred dead were seen in the neighbourhood of Langemarck. Correspondence found subsequently on a captured German Officer stated that the effectives of this attacking Corps were reduced to 25 per cent, in the course of the day's fighting.

In the evening of this day a division of the French 9th Army Corps came up into line and took over the portion of the line held by the 2nd Division, which, on the 24th, took up the ground occupied by the 7th Division from Poelzelhoek to the Becelaere-Passchendaele Road.

On the 24th and 25th October repeated attacks by the enemy were brilliantly repulsed.

On the night of the 24th-25th the 1st Division was relieved by French Territorial troops and concentrated about Zillebeke.

During the 25th the 2nd Division, with the 7th on its right and the French 9th Corps on its left, made good progress towards the north-east, capturing some guns and prisoners.

On October 27 I went to the headquarters of the 1st Corps at Hooge to personally investigate the condition of the 7th Division.

Owing to constant marching and fighting, ever since its hasty disembarkation, in aid of tin Antwerp Garrison, this division had suffered great losses, and were becoming very weak, therefore decided temporarily to break up the 4th Corps and place the 7th Division with the 1st Corps under the command of Sir Dougla Haig.

The 3rd Cavalry Division was similarly detaile for service with the 1st Corps.*

* There was only one infantry division in this weak corps and the task assigned to it had been a very heavy one.

I directed the 4th Corps Commander to proceed with his Staff, to England, to watch and supervise the mobilisation of his 8th Division, which was then proceeding.

On receipt of orders, in accordance with the above arrangement, Sir Douglas Haig redistributed the line held by the First Corps as follows:—

(a) 7th Division from the Château east of 510 Zandvoorde to the Menin Road.

(b) 1st Division from the Menin Road to a point immediately west of Reytel Village.

(c) 2nd Division to near Moorslede-Zonnebeke Road.

On the early morning of October 29 a heavy attack developed against the centre of the line held by the 1st Corps, the principal point of attack being the cross-roads one mile east of Gheluvelt. After severe fighting—nearly the whole of the Corps being employed in counter attack—the enemy began to give way at about 2 p.m.; and by dark the Kruiseik Hill had been recaptured and the 1st Brigade had re-established most of the line north of the Menin Road.

Shortly after daylight on the 30th another attack began to develop in the direction of Zandvoorde, supported by heavy artillery fire. In face of this attack the 3rd Cavalry Division had to withdraw to the Klein Zillebeke ridge. This "withdrawal" involved the right of the 7th Division. Sir Douglas Haig describes the position at this period as serious, the Germans being in possession of Zandvoorde Ridge.

Subsequent investigation showed that the enemy had been reinforced at this point by the whole German Active 15th Corps.

The General Officer Commanding 1st Corps ordered the line Gheluvelt to the corner of the canal to be held at all costs. When this line was taken up the 2nd Brigade was ordered to concentrate in rear of the 1st Division and the 4th Brigade line. One battalion was placed in reserve in the woods one mile south of Hooge.

Further precautions were taken at night to protect this flank, and the 9th French Corps sent three battalions and one Cavalry Brigade to assist.

The 1st Corps communications through Ypres were threatened by the advance of the Germans towards the canal; so orders were issued for every effort to be made to secure the line then held and, when this had been thoroughly done, to resume the offensive.

An order taken from a prisoner who had been captured on this day purported to emanate from the German General, von Beimling, and said that the 15th German Corps, together with the 2nd Bavarian and 13th Corps, were entrusted with the task of breaking through the line to Ypres; and that the Emperor himself considered the success of this attack to be one of vital importance to the successful issue of the war.

Perhaps the most important and decisive attack (except that of the Prussian Guard on November 15) made against the 1st Corps during the whole of its arduous experiences in the neighbourhood of Ypres took place on October 31.*

* A description of this fight is to be found on page 115 of the narrative.

General Moussy, who commanded the detachment which had been sent by the French 9th Corps on the previous day to assist Sir Douglas Haig on the right of the 1st Corps, moved to the attack early in the morning, but was brought to a complete standstill and could make no further progress.

After several attacks and counter-attacks during the course of the morning along the Menin-Ypres road, south-east of Gheluvelt, an attack against that place developed in great force, and the line of the 1st Division was broken. On the south the 7th Division and General Bulfin's detachment were being heavily shelled. The retirement of the 1st Division exposed the left of the 7th Division, and owing to this the Royal Scots Fusiliers, who remained in their trenches, were cut off and surrounded. A strong infantry attack was developed against the right of the 7th Division at 1.30 p.m.

Shortly after this the Headquarters of the 1st and 2nd Divisions were shelled. The General Officer Commanding the 1st Division was wounded, three Staff Officers of the 1st Division and three of the 2nd Division were killed.* The General Officer Commanding the 2nd Division also received a severe shaking and was unconscious for a short time. General Landon assumed command of the 1st Division.

* This was an extraordinary circumstance, and shows not only how close up were the Staffs, but the result of German espionage, because there can be no doubt that the enemy received exact information as to the positions the Staffs occupied.

On receiving a report about 2.30 p.m. from General Lomax that the 1st Division had moved back and that the enemy was coming on in strength, the General Officer Commanding the 1st Corps issued orders that the line, Frezenburg-Westhoek-bend of the main road-Klein Zillebeke bend of canal, was to be held at all costs.

The 1st Division rallied on the line of the woods east of the bend of the road, the German advance by the road being checked by enfilade fire from the north.

The attack against the right of the 7th Division forced the 22nd Brigade to retire, thus exposing the left of the 2nd Brigade. The General Officer Commanding the 7th Division used his reserve, already posted on his flank, to restore the line; but, in the meantime, the 2nd Brigade, finding their left flank exposed, had been forced to withdraw. The right of the 7th Division thus advanced as the left of the 2nd Brigade went back, with the result that the right of the 7th Division was exposed, but managed to hold on to its old trenches till nightfall.

Meantime, on the Menin road, a counterattack delivered by the left of the 1st Division and the right of the 2nd Division against the right flank of the German line was completely successful, and by 2.30 p.m. Gheluvelt had been retaken with the bayonet, the 2nd Worcester Regiment being to the fore in this, admirably supported by the 42nd Brigade, Royal Field Artillery.* The left of the 7th Division, profiting by their capture of Gheluvelt, advanced almost to its original line; and connection between the 1st and 7th Divisions was re- established. The recapture of Gheluvelt released the 6th Cavalry Brigade, till then held in support of the 1st Division. Two regiments of this brigade were sent at once to clear the woods to the south-east, and close the gap in the line between the 7th Division and the 2nd Brigade. They advanced with much dash, partly mounted and partly dismounted; and, surprising the enemy in the woods, succeeded in killing large numbers and materially helped to restore the line. About 5 p.m. the French Cavalry Brigade also came up to the cross-roads just east of Hooge, and at once sent forward a dismounted detachment to support our 7th Cavalry Brigade.

* This desperate and bloody battle for the village of Gheluvelt is described on page 137.

Throughout the day the extreme right and left of the 1st Corps' line held fast, the left being only slightly engaged, while the right was heavily shelled and subjected to slight infantry attacks. In the evening the enemy were steadily driven back from the woods on the front of the 7th Division and 2nd Brigade; and by 10 p.m. the line as held in the morning had practically been reoccupied.

During the night touch was restored between the right of the 7th Division and left of the 2nd Brigade, and the Cavalry were withdrawn into reserve, the services of the French Cavalry being dispensed with.

As a result of the day's fighting eight hundred and seventy wounded were evacuated.

I was present with Sir Douglas Haig at Hooge between 2 and 3 o'clock on this day, when the 1st Division were retiring. I regard it as the most critical moment in the whole of this great battle. The rally of the 1st Division and the recapture of the village of Gheluvelt at such a time was fraught with momentous consequences. If any one unit can be singled out for especial praise it is the Worcesters.

In the meantime the centre of my line, occupied by the 3rd and Cavalry Corps, was being heavily pressed by the enemy in ever-increasing force.

On October 20 advanced posts of the 12th Brigade of the 4th Division, 3rd Corps, were forced to retire, and at dusk it was evident that the Germans were likely to make a determined attack. This ended in the occupation of Le Gheir by the enemy.

As the position of the Cavalry at St. Yves was thus endangered, a counter- attack was decided upon and planned by General Hunter-Weston and Lieutenant- Colonel Anley. This proved entirely successful, the Germans being driven back with great loss and the abandoned trenches reoccupied. Two hundred prisoners were taken and about forty of our prisoners released.

In these operations the staunchness of the King's Own Regiment and the Lancashire Fusiliers was most commendable. These two battalions were very well handled by Lieutenant-Colonel Butler, of the Lancashire Fusiliers.

I am anxious to bring to special notice the excellent work done throughout this battle by the 3rd Corps under General Pulteney's command. Their position in the right central part of my line was of the utmost importance to the general success of the operations. Besides the very undue length of front which the Corps was called upon to cover (some 12 or 13 miles), the position presented many weak spots, and was also astride of the River Lys, the right bank of which from Frelinghien downwards was strongly held by the enemy. It was impossible to provide adequate reserves, and the constant work in the trenches tried the endurance of officers and men to the utmost. That the Corps was invariably successful in repulsing the constant attacks, sometimes in great strength, made against them by day and by night, is due entirely to the skilful manner in which the Corps was disposed by its Commander, who has told me of the able assistance he has received throughout from his Staff, and the ability and resource displayed by Divisional, Brigade, and Regimental leaders in using the ground and the means of defence at their disposal to the very best advantage.

The courage, tenacity, endurance, and cheerfulness of the men in such unparalleled circumstances are beyond all praise.

During October 22, 23, and 24 frequent attacks were made along the whole line of the 3rd Corps, and especially against the 16th Infantry Brigade, but on all occasions the enemy was thrown back with loss.

During the night of October 25 the Leicestershire Regiment were forced from their trenches by shells blowing in the pits they were in; and after investigation by the General Officers Commanding the 16th and 18th Infantry Brigades, it was decided to throw back the line temporarily in this neighbourhood.

On the evening of October 29 the enemy made a sharp attack on Le Gheir, and on the line to the north of it, but were repulsed.

About midnight a very heavy attack developed against the 19th Infantry Brigade south of Croix Maréchal. A portion of the trenches of the Middlesex Regiment was gained by the enemy and held by him for some hours till recaptured with the assistance of the detachment from the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders from Brigade Reserve. The enemy in the trenches were all bayonetted or captured. Later information from prisoners showed that there were twelve battalions opposite the 19th Brigade. Over two hundred dead Germans were left lying in front of the Brigade's trenches and forty prisoners were taken.

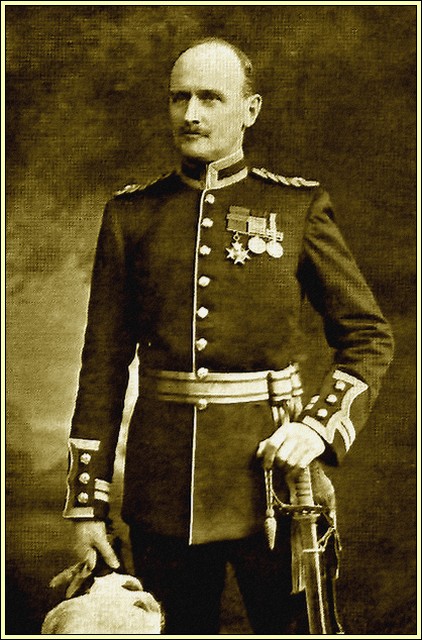

General K.H. Allenby, C.B., in Command of the Cavalry Corps.

On the evening of the 30th the line of the 11th Infantry Brigade in the neighbourhood of St. Yves was broken. A counter-attack carried out by Major Prowse with the Somerset Light Infantry restored the situation. For his services on this occasion this officer was recommended for special reward.

On October 31 it became necessary for the 4th Division to take over the extreme right of the 1st Cavalry Division's trenches, although this measure necessitated a still further extension of the line held by the 3rd Corps.

On October 20, while engaged in the attempt to force the line of the River Lys, the Cavalry Corps was attacked from the South and East. In the evening the 1st Cavalry Division held the line St. Yves-Messines; the 2nd Cavalry Division from Messines through Garde Dieu along the Wambeck to Houthem and Kortewilde.

At 4 p.m. on October 21 a heavy attack was made on the 2nd Cavalry Division which was compelled to fall back to the line Messines-9th kilo stone on the Wameton-Oostaveme Road-Hollebeke.

On the 22nd I directed the 7th Indian Infantry Brigade, less one battalion, to proceed to Wulverghem in support of the Cavalry Corps. General Allenby sent two battalions to Wytschaete and Voormezeele to be placed under the orders of General Gough, Commanding the 2nd Cavalry Division.

On the 23rd, 24th, and 25th, several attacks were directed against the Cavalry Corps and repulsed with loss to the enemy.

On October 26 I directed General Allenby to endeavour to regain a more forward line, moving in conjunction with the 7th Division. But the latter being apparently quite unable to take the offensive, the attempt had to be abandoned.

On October 30 heavy infantry attacks, supported by powerful artillery fire, developed against the 2nd and 3rd Cavalry Divisions, especially against the trenches about Hollebeke held by the 3rd Cavalry Brigade. At 1.30 p.m. this Brigade was forced to retire, and the 2nd Cavalry Brigade, less one regiment, was moved across from the 1st Cavalry Division to a point between Oostaveme and St. Eloi in support of the 2nd Cavalry Division.

The 1st Cavalry Division in the neighbourhood of Messines was also threatened by a heavy infantry column.

General Allenby still retained the two Indian Battalions of the 7th Indian Brigade, although they were in a somewhat exhausted condition.

After a close survey of the positions and consultations with the General Officer Commanding the Cavalry Corps, I directed four battalions of the 2nd Corps, which had lately been relieved from the trenches by the Indian Corps, to move to Neuve Eglise under General Shaw, in support of General Allenby.

The London Scottish Territorial Battalion was also sent to Neuve Eglise.*

*It was this village that, after three desperate charges, the distinguished Territorial regiment drove back the enemy with great loss.

It now fell to the lot of the Cavalry Corps, which had been much weakened by constant fighting, to oppose the advance of two nearly fresh German Army Corps for a period of over forty-eight hours, pending the arrival of a French reinforcement. Their action was completely successful. I propose to send shortly a more detailed account of the operation.

After the critical situation in front of the Cavalry Corps, which was ended by the arrival of the head of the French 16th Army Corps, the 2nd Cavalry Division was relieved by General Conneau's French Cavalry Corps and concentrated in the neighbourhood of Bailleul.

The 1st Cavalry Division continued to hold the line of trenches east of Wulverghem.

From that time to the date of this despatch the Cavalry Divisions have relieved one another at intervals, and have supported by their artillery the attacks made by the French throughout that period on Hollebeke, Wytschaete and Messines.

The 3rd Corps in its position on the right of the Cavalry Corps continued throughout the same period to repel constant attacks against its front, and suffered severely from the enemy's heavy artillery fire.

The artillery of the 4th Division constantly assisted the French in their attacks.

The General Officer Commanding 3rd Corps brings specially to my notice the excellent behaviour of the East Lancashire Regiment, the Hampshire Regiment, and the Somersetshire Light Infantry in these latter operations; and the skilful manner in which they were handled by General Hunter-Weston, Lieutenant- Colonel Butler, and the Battalion Commanders.

The Lahore Division arrived in its concentration area in rear of the 2nd Corps on October 19 and 20.

I have already referred to the excellent work performed by the battalions of this Division which were supporting the Cavalry. The remainder of the Division from the October 25 onwards were heavily engaged in assisting the 7th Brigade of the 2nd Corps in fighting round Neuve Chapelle. Another Brigade took over some ground previously held by the French 1st Cavalry Corps and did excellent service.

On October 28 especially the 47th Sikhs and the 20th and 21st Companies of the 3rd Sappers and Miners distinguished themselves by their gallant conduct in the attack on Neuve Chapelle, losing heavily in officers and men.

After the arrival of the Meerut Division at Corps Headquarters the Indian Army Corps took over the line previously held by the 2nd Corps, which was then partially drawn back into reserve. Two and a half brigades of British Infantry and a large part of the Artillery of the 2nd Corps still remained to assist the Indian Corps in defence of this line. Two and a half battalions of these brigades were returned to the 2nd Corps when the Ferozepore Brigade joined the Indian Corps after its support of the Cavalry further north.

The Secunderabad Cavalry Brigade arrived in the area during the 1st and 2nd November, and the Jodhpur Lancers came about the same time. These were all temporarily attached to the Indian Corps.

Up to the date of the present despatch the line held by the Indian Corps has been subjected to constant bombardment by the enemy's heavy artillery, followed up by infantry attacks.

On two occasions these attacks were severe.

On October 13 the 8th Gurkha Rifles of the Bareilly Brigade were driven from their trenches and on November 2 a serious attack was developed against a portion of the line west of Neuve Chapelle. On this occasion the line was to some extent pierced and was consequently slightly bent back.

The situation was prevented from becoming serious by the excellent leadership displayed by Colonel Norie, of the 2nd Gurkha Rifles.

Since their arrival in this country and their occupation of the line allotted to them, I have been much impressed by the initiative and resource displayed by the Indian troops. Some of the ruses they have employed to deceive the enemy have been attended with the best results and have doubtless kept superior forces in front of them at bay.

The Corps of Indian Sappers and Miners have long enjoyed a high reputation for skill and resource. Without going into detail I can confidently assert that throughout their work in this campaign they have fully justified their reputation.

The General Officer Commanding the Indian Army Corps describes the conduct and bearing of these troops in strange and new surroundings to have been highly satisfactory, and I am enabled, from my own observation, fully to corroborate his statement.

Honorary Major-General H.H. Sir Pratap Singh Bahadur, G.C.S.I., G.C.V.O., K.C.B., A.D.C., Maharaja-Regent of Jodhpur; Honorary Lieutenant H.H. the Maharaja of Jodhpur; Honorary Colonel H.H. Sir Ganga Singh Bahadur, G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E., A.D.C., Maharaja of Bikanir; Honorary Major H.H. Sir Madan Singh Bahadur, K.C.S.I., K.C.I.E., Maharaja-Dhirai of Kishengarh; Honorary Captain the Honourable Malik Umar Hayat Khan, C.I.E., M.V.O., Tiwana; Honorary Lieutenant Raj-Kumar Hira Singh of Panna; Honorary Lieutenant Maharai-Kumar Hitendra Narayan of Cooch Behar; Lieutenant Malik Mumtaz Mahomed Khan, Native Indian Land Forces; Resaldar Khwaja Mahomed Khan Bahadur, Queen Victoria's Own Corps of Guides; Honorary Captain Shah Mirza Beg, are serving with the Indian contingents.

While the whole of the line has continued to be heavily pressed, the enemy's principal efforts since November 1 have been concentrated upon breaking through the line held by the 1st British and 9th French Corps, and thus gaining possession of the town of Ypres.

From November 2 onwards the 27th, the 15th, and parts of the Bavarian 13th and 2nd German Corps, besides other troops, were all directed against this northern line.

About the 10th instant, after several units of these Corps had been completely shattered in futile attacks, a division of the Prussian Guard, which had been operating in the neighbourhood of Arras, was moved up to this area with great speed and secrecy. Documents found on dead officers prove that the Guard had received the Emperor's special commands to break through and succeed where their comrades of the line had failed.

They took a leading part in the vigorous attacks made against the centre on the 11th and 12th; but, like their comrades, were repulsed with enormous loss.

Throughout this trying period Sir Douglas Haig, ably assisted by his Divisional and Brigade Commanders, held the line with marvellous tenacity and undaunted courage.

Words fail me to express the admiration I feel for their conduct, or my sense of the incalculable services they rendered. I venture to predict that their deeds during these days of stress and trial will furnish some of the most brilliant chapters which will be found in the military history of our time.

The 1st Corps was brilliantly supported by the 3rd Cavalry Division under General Byng, Sir Douglas Haig has constantly brought this officer's eminent services to my notice. His troops were repeatedly called upon to restore the situation at critical points, and to fill gaps in the line caused by the tremendous losses which occurred.

Both Corps and Cavalry Division Commanders particularly bring to my notice the name of Brigadier-General Kavanagh, Commanding the 7th Cavalry Brigade, not only for his skill but his personal bravery and dash. This was particularly noticeable when the 7th Cavalry Brigade was brought up to support the French troops when the latter were driven back near the village of Klein Zillebeke on the night of November 7. On this occasion I regret to say Colonel Gordon Wilson, Commanding the Royal Horse Guards, and Major the Hon. Hugh Dawnay, Commanding the 2nd Life Guards, were killed.

In these two officers the Army has lost valuable cavalry leaders.

Another officer whose name was particularly mentioned to me was that of Brigadier-General FitzClarence, V.C., Commanding the 1st Guards Brigade. He was, unfortunately, killed in the night attack of the 11th November. His loss will be severely felt.*

* Brigadier-General Charles FitzClarence, V.C., Commander of the Irish Guards before the outbreak of war. He won his V.C. in South Africa.

The 1st Corps Commander informs me that on many occasions Brigadier- General the Earl of Cavan, Commanding the 4th Guards Brigade, was conspicuous for the skill, coolness, and courage with which he led his troops, and for the successful manner in which he dealt with many critical situations.

I have more than once during this campaign brought forward the name of Major- General Bulfin to your Lordship's notice.* Up to the evening of November 2, when he was somewhat severely wounded, his services continued to be of great value.

* Major-General Bulfin entered the army in 1885 and served in Burma and South Africa.

On November 5 I despatched eleven battalions of the 2nd Corps, all considerably reduced in strength, to relieve the infantry of the 7th Division, which was then brought back into general reserve.

Three more battalions of the same Corps, the London Scottish and Hertfordshire Battalions of Territorials, and the Somersetshire and Leicestershire Regiments of Yeomanry, were subsequently sent to reinforce the troops fighting to the east of Ypres.

General Byng in the case of the Yeomanry Cavalry Regiments and Sir Douglas in that of the Territorial Battalions speak in high terms of their conduct in the field and of the value of their support.

The battalions of the 2nd Corps took a conspicuous part in repulsing the heavy attacks delivered against this part of the line. I was obliged to dispatch them immediately after their trying experiences in the southern part of the line and when they had had a very insufficient period of rest; and, although they gallantly maintained these northern positions until relieved by the French, they were reduced to a condition of extreme exhaustion.

The work performed by the Royal Flying Corps has continued to prove of the utmost value to the success of the operations.

I do not consider it advisable in this despatch to go into any detail as regards the duties assigned to the Corps and the nature of their work, but almost every day new methods for employing them, both strategically and tactically, are discovered and put into practice.

The development of their use and employment has indeed been quite extraordinary, and I feel sure that no effort should be spared to increase their numbers and perfect their equipment and efficiency.

In the period covered by this despatch Territorial Troops have been used for the first time in the Army under my command.

The units actually engaged have been the Northumberland, Northamptonshire, North Somerset, Leicestershire, and Oxfordshire Regiments of Yeomanry Cavalry; and the London Scottish, Hertfordshire, Honourable Artillery Company, and the Queen's Westminster Battalions of Territorial Infantry.

The conduct and bearing of these units under fire, and the efficient manner in which they carried out the various duties assigned to them, have imbued me with the highest hope as to the value and help of Territorial Troops generally.

Units which I have mentioned above, other than these, as having been also engaged, have by their conduct fully justified these hopes.

Regiments and battalions as they arrive come into a temporary camp of instruction, which is formed at Headquarters, where they are closely inspected, their equipment examined, so far as possible perfected, and such instruction as can be given to them in the brief time available in the use of machine guns, etc., is imparted.

Several units have now been sent up to the front besides those I have already named, but have not yet been engaged.

I am anxious in this despatch to bring to your Lordship's special notice the splendid work which has been done throughout the campaign by the Cyclists of the Signal Corps.

Carrying despatches and messages at all hours of the day and night in every kind of weather, and often traversing bad roads blocked with transport, they have been conspicuously successful in maintaining an extraordinary degree of efficiency in the service of communications.

Many casualties have occurred in their ranks, but no amount of difficulty or danger has ever checked the energy and ardour which has distinguished their Corps throughout the operations.

As I close this despatch there are signs in evidence that we are possibly in the last stages for the battle of Ypres-Armentières.

For several days past the enemy artillery fire has considerably slackened, and infantry attack has practically ceased.

In remarking upon the general military situation of the Allies as it appears to me at the present moment, it does not seem to be clearly understood that the operations in which we have been engaged embrace nearly all the Continent of Central Europe from East to West. The combined French, Belgian, and British Armies in the West and the Russian Army in the East are opposed to the united forces of Germany and Austria acting as a combined army between us.

Our enemies elected at the commencement of the war to throw the weight of their forces against the armies in the West, and to detach only a comparatively weak force, composed of very few first-line troops and several corps of the second and third lines, to stem the Russian advance till the Western Forces could be completely defeated and overwhelmed.

Their strength enabled them from the outset to throw greatly superior forces against us in the West. This precluded any possibility of our taking a vigorous offensive, except when the miscalculations and mistakes made by their commanders opened up special opportunities for a successful attack and pursuit.

The battle of the Marne was an example of this, as was also our advance from St. Omer and Hazebrouck to the line of the Lys at the commencement of this battle. The rôle which our Armies in the West have consequently been called upon to fulfil has been to occupy strong defensive positions, holding the ground gained and in inviting the enemy's attack; to throw these attacks back, causing the enemy heavy losses in his retreat and following him up with powerful and successful counter-attacks to complete his discomfiture.

The value and significance of the rôle fulfilled since the commencement of hostilities by the Allied Forces in the West lies in the fact that at the moment when the Eastern Provinces of Germany are in imminent danger of being overrun by the numerous and powerful armies of Russia, nearly the whole of the active army of Germany is tied down to a line of trenches extending from the Fortress of Verdun on the Alsatian Frontier round to the sea at Nieuport, east of Dunkirk (a distance of 260 miles), where they are held, much reduced in numbers and moral by the successful action of our troops in the West.

I cannot speak too highly of the valuable services rendered by the Royal Artillery throughout the battle.

In spite of the fact that the enemy has brought up guns in support of his attacks of great range and shell power ours have succeeded throughout in preventing the enemy from establishing anything in the nature of an artillery superiority. The skill, courage, and energy displayed by their commanders have been very marked.

The General Officer Commanding 3rd Corps, who had special means of judging, makes mention of the splendid work performed by a number of young artillery officers, who in the most gallant manner pressed forward in the vicinity of the firing line in order that their guns may be able to shoot at the right targets at the right moment.

The Royal Engineers have, as usual, been indefatigable in their efforts to assist the infantry in field fortification and trench work.

I deeply regret the heavy casualties which we have suffered; but the nature of the fighting has been very desperate, and we have been assailed by vastly superior numbers. I have every reason to know that throughout the course of the battle we have placed at least three times as many of the enemy hors de combat in dead, wounded, and prisoners.

Throughout these operations General Foch has strained his resources to the utmost to afford me all the support he could; and an expression of my warm gratitude is also due to General D'Urbal, Commanding the 8th French Army on my left and General Maud'huy, Commanding the 10th French Army on my right.

I have many recommendations to bring to your Lordship's notice for gallant and distinguished service performed by officers and men in the period under report. These will be submitted shortly, as soon as they can be collected.

I have the honour to be,

Your Lordship's most obedient servant,

(Signed) J. P. D. FRENCH, Field-Marshal,

Commanding-in-Chief,

The British Army in the Field.

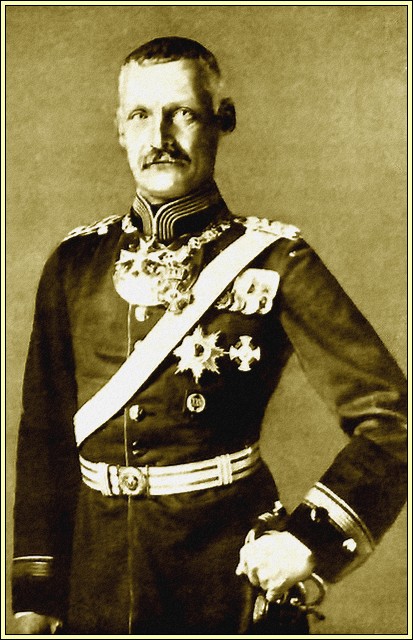

King Albert of Belgium.

The New Field of Battle—Typical Warfare—How the British Came North—How the Great Battle Began—Bridging the Dykes—How the Dorsets held Pont Fixe—A Murderous Battle in the Dark

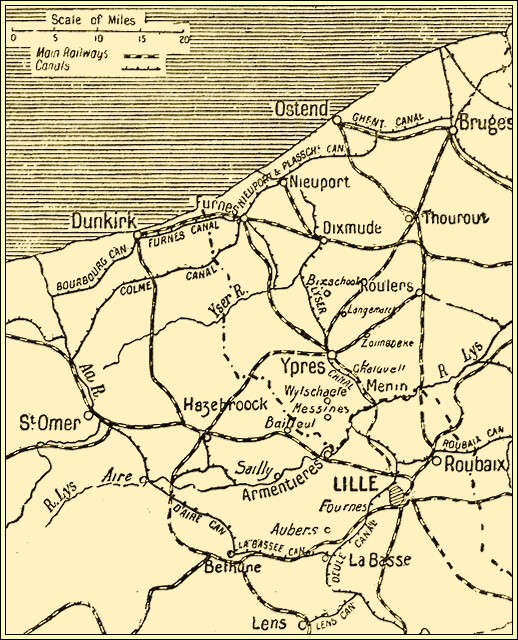

IF you can picture a great stretch of land, flat and featureless, save in one or two remarkable exceptions, and in your imagination lay out upon this drab, unattractive country a number of bad roads, a light railway or two, along which in normal times a conveyance which is half tramcar and half railway train plies a leisured service; if you can imagine something of Holland, with great windmills, innumerable thrifty waterways, canals and minor rivers, with here and there a straggling village possessing a name which even Baedeker does not record, and small towns that were the scene in other days of remarkable and sanguinary combats; if you can imagine a certain squalor, a certain sordidness— when you are approaching the manufacturing and mining districts—and also a certain charm, you are imagining south- west Belgium, in which has been fought the great Battle for the Coast.

Farther down, in the north of France, Arras and La Bassée played their parts, and played them worthily; but since for the moment our minds and our thoughts are concentrated upon the performances of our own Army, it will be well if we think only of the country west of the Yser, and that little strip of France which lies between Bethune, Hazebrouck, and the Belgian frontier. On these uninspiring fields, amidst gaunt hop poles and rotting beet fronds, in ugly little roads, by gaunt white farmhouses, most unlovely, in straggling copses and chilly plantations; in all the most unlikely settings has the heroism of the British Army been proved. In this war there are no longer battlefields; there are battle countries, and battle lines which stretch half across the Continent, which take in the waste and the wood, the town and the meadow, the river and the railway; but battlefields in Waterloo sense are of the past.

Let us picture for ourselves one of those fights, the extraordinary character of which is peculiar only to this war. A great stretch of countryside, more undulating than usual, a hill covered with woods, a dim and blue background of trees and ridge, farmhouses dotted here and there, telegraph posts that stalk across the middle distance, a dilapidated railway with its rails twisted and wrecked, and its culverts shattered by dynamite, a row of humble cottages where the peasants have been living now a sand-bagged fort hastily painted a dull grey and streaked with green by the handiest of engineers; and nothing else on the face of the earth—no sign of life, of human being, of soldier or gun, transport or horse.

Within hail there are perhaps 50,000 men. The aeroplane which comes buzzing overhead at a tremendous height can see what the observer on the ground could not detect—the long streaks of trenches where men stand to arms; the gun emplacements hidden by the boughs of trees; the rifle pits of the snipers; the defended farmhouses; the ditches and sunken roads packed with infantry pressed tight against the banks to avoid attracting the attention of the aerial observer. Seldom would it be possible for us to see without hearing, for all night long the guns have been booming on both sides, and the air has been filled with the whine of shells, rent with the crash of exploding shrapnel, fired, it may seem, carelessly, yet with good reason, for every shell is timed to burst above one of those scars in the surface of the earth, where men are waiting, deadly weapon in hand, ready to fling back the too daring attack of its enemy.

German grey coats springing up from the earth rush across the fire zone, and are annihilated by the close fire which is poured upon their flank.

For it is to the flank of the advancing infantry that the British soldier directs his attention, firing steadily by sections at the right- or left-hand man, and those who watch the German advance marvel as it whittles to the centre; its progress marked by a great broad arrow of dead and dying, the point towards the British trenches.

Then comes a scramble of the British to the earth, the quick flash and thud of bayonets, the wild yell which invariably accompanies an infantry charge, the scattering of Germans who go blundering back to their trenches, the shrill whistle that recalls the infantry to a safer formation, and again both sides disappear into their trenches, and there is nothing to mark the failure save the dead that both sides have left on the field.

You might tell of such a scene a hundred, a thousand times, and in very little different language describe almost every fight in which the British have been engaged. It is because of the sameness, the very monotony of heroism, that the historian will discover his greatest difficulty in dealing with this extraordinary campaign.

In the middle of October you would have seen the British cavalry columns feeling their way cautiously toward Armentières. Day by day, the cavalry of the opposing masses were whirling and manoeuvring in the difficult country which lies to the north of the Lys. Day by day the British guns were searching every likely position before them, and driving out crowds of Germans hastily flung forward from Lille to cover the work which the German army, not yet in full force on this front, was carrying out. Very steadily the progress went on; you would have seen the convoys passing up the ill-paved roads from the coast towns; you would have seen the stained and weather-worn motor cars and motor transports; you would have met knots of soldiers, a mounted orderly or two, streams of refugees retiring from shell-swept villages, and perhaps now and again you might hear the far-off murmur of the guns. The army had already passed this way in the wake of the cautious cavalry, had shelled a village or two, had had its aerial scouts sweeping through the air at a dangerous level to discover the character of the resistance which might be expected.

Eastward of Hazebrouck, the advancing British, in thickened formation, had come across the first serious opposition. Yet that also melted away, and these splendid columns went on. Each side was sparring for an opening, seeking for a battle front which the accident of war would reveal. North and south of the river Lys the British advance continued in the direction of Menin. Bad roads, intersecting waterways, canals, all the tiny arteries of commerce that feed town and village, that empty coalfields of their produce and bring merchandise in return; marsh and fen lands and treacherous bogs, all helped to make the progress a slow one. And there were many little clustering villages perched upon whatever rise of ground lifted the people of the countryside from the mist of the fens—points of vantage whence an enemy's artillery could concentrate its fire upon the advancing force.

In recording such events as go to the making up of a history of such a war as this, there is always a danger that one's perspective may shift, and that vivid patches of colour may dazzle us from following the road, and cause us to stray into those splendid fields of individual heroism and accomplishment which so attract and entice the wayfarer. This instance of courage, that example of fortitude, lead us from left to right, to pause in amazement and pride before the wonder which brave men inspire.

The scale of operations has been so extensive that were I to devote adequate space to dealing with detached events, scattered battles, and heroic deeds in the extensive field in which the Allies have been engaged, I should require several volumes. In this narrative I propose to gather up the threads of the story, to summarise into a connected whole the happenings and the great battles which have taken place from the date when operations on the Aisne came to a deadlock, to the middle of November, when the British Army, transferred from the region of the Aisne, had already for over a month in the north defied all efforts of the enemy to break through to Dunkirk and Calais. In this way I hope to give a broad view of the conflict. This summary will exhibit in a more definite form than would otherwise be possible the strategy pursued by Sir John French, the extraordinary cleverness of his plans, and the wonderful bravery of his troops in the face of formidable odds and amazing difficulties.

The prolonged battle of Ypres-Armentières, as I have said, was a development of the continuous struggle which commenced on the Aisne after the great German retreat from Paris. The efforts of the Allies and the Germans alike were directed to attempting to outflank each other. There came a time on the Aisne when it seemed to Sir John French that he would be warranted in withdrawing the British Forces from the positions they then held, and he took counsel with General Joffre to that end.

Field-Marshal French, with a large and cheerful army, growing somewhat impatient because of the block which the German had put upon further progress by his defence of the Aisne, importuned the French General to such good effect that one night the German watchers heard strange sounds from the British trenches. These they dismissed carelessly as a usual happening, for every night the men in the trenches were relieved by fresh troops, and that relief was not to be accomplished without a certain amount of noise. But in the morning, when the German aviators flew over the Allies' position, behold! the British were gone, so far as could be seen.

It was no easy business to withdraw the British forces from their position on the Aisne and transfer them to new positions a long way off in Northern France and Flanders; when the nightly reliefs were carried out French territorials took their places in the British trenches and the British Army withdrew quietly by train and road to the field of operations. For many days the left flank of the Armies was in an exceedingly critical condition, and it is easy to see from the despatches how near the Germans were to establishing themselves on the northern coast of France.

It was, as General French tells us, on October 3rd that Gough's Cavalry Division moved from Soissons, and passed northward to get upon the French left and begin a movement which was to outflank the German's right. It was not known at this moment how far the enemy was prepared to extend his line in order to cover his exposed flank; and perhaps it was not realised that he would move so immediately to mass troops in the threatened area. As likely as not—and time will prove the truth of this contention—the General Staff knew something of the intention of the German to move on Calais. At any rate, the German cavalry was dangerously near the main line which extends from Calais-Boulogne to Paris. There had been some raiding; a section of the line had been blown up; a culvert or two smashed, and naturally a certain number of reprisals, for the French cavalry are not wanting in enterprise or dash.

Lille was known to be occupied by enemy troops. La Bassée, one of the strongest positions on the line, was equally well held. There were even reports that the enemy in strength lay somewhere between Lille and the coast, and Sir John French, in conjunction with General Joffre, made his plans with due caution, realising the possibility of an unpleasant set-back, and taking no risk of incurring disaster at the enemy's hands.

Already the French line, in endeavouring to outflank the enemy, had extended practically up from Soissons to beyond Arras, when the English moved up to take their place upon the left of the French line. Sir John French took a margin of safety, and none too much as it proved, though he formed his line within a few miles of the coast. First to go was the 2nd Army Corps under Sir Horace Smith- Dorrien. This Corps, composed of some of the finest units in the British Army, was ordered to hold the line of a canal which runs between Bethune and Aire. Aire is a little south of St. Omer, and Bethune farther south- east.

The 2nd Corps was due to take up its position on the 12th of October, and to the minute it arrived on that day. The cavalry which had been on the French left now came up in front of the 2nd Corps, clearing the ground of any stragglers, and keeping touch with the enemy, and took up its position on the left of Smith-Dorrien's Corps. In the meantime the 3rd Army Corps had trained up to St. Omer, and fell in so that its right touched the left of the 2nd Corps.