General, Sir Ian Hamilton.

WAR was declared on August 4 at midnight (German time). At that moment the British fleet, mobilised and ready, was at the stations which had been decided upon in the event of war with Germany. By an act of foresight which cannot be too highly commended the fleet had been mobilised for battle practice a week or so before the actual outbreak of hostilities and at a time when it was not certain whether Great Britain would engage herself in the war. The wisdom of our preparations was seen after war was declared.

From the moment the battle fleet sailed from Spithead and disappeared over the horizon it vanished so far as the average man in the street was concerned, and from that day onward its presence was no more advertised.

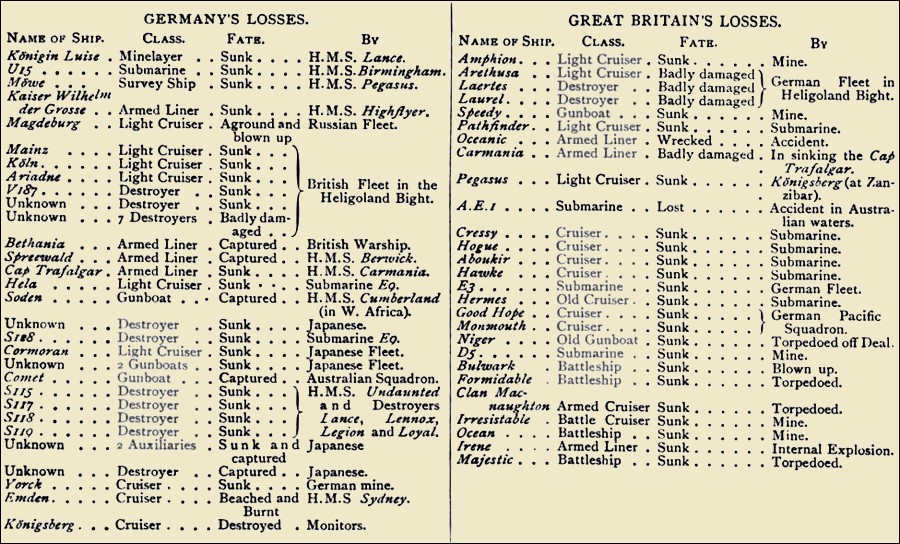

The first few days following the outbreak of war we suffered certain losses. On August 6 the Amphion was mined after having destroyed by gun fire the Königin Luise. On September 5 the Pathfinder was torpedoed by a "U" boat, and on September 22 the Aboukir, the Cressy, and the Hogue were destroyed by a German submarine. In the meantime the German had had his trouble. The Magdeburg was shot down by gun fire at the hands of the Russian navy. The Köln, the Ariadne and the Mainz with the German destroyer V187 had been caught in the Bight of Heligoland, and had been sunk.

We had our lessons to learn, and we were prompt to profit by dire experience. The closing of ships to save others had led to the triple disaster of September 22, and save for the vessels we lost in the South Atlantic fight and the two battleships, one of which (Bulwark) was torpedoed and blown up in November, and the other (Formidable) in December, and the blowing up of the Princess Irene in March, we endured no losses in home waters.

Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty.

In giving a survey of the sea operations one necessarily must deal with those services which are associated with the Navy, and a history of naval matters must necessarily lead to those great operations which developed so sensationally in the Dardanelles and on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

It had been hoped that, in the very early stages of the war, the British fleet would be given an opportunity of meeting the German Grand Fleet—a hope foredoomed, since with its marked inferiority it was unlikely that the enemy would try conclusions with his enemy on the sea.

Twice did any considerable portion of the enemy fleet venture forth and the thrilling story of the first adventure is told in Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty's despatch and in the supplementary despatches. The British moved into the Bight of Heligoland on Thursday, August 27, the First Battle Cruiser Squadron and the First Light Cruiser Squadron.

"At 4 a.m., August 28, the movements of the flotillas commenced as previously arranged," wrote Admiral Beatty, "the Battle Cruiser Squadron and Light Cruiser Squadron supporting. The Rear-Admiral, Invincible, with New Zealand and four destroyers having joined my flag, the squadron passed through the pre-arranged rendezvous.

"At 8.10 a.m. I received a signal from the Commodore (i),* informing me that the flotilla was in action with the enemy. This was presumably in the vicinity of their pre-arranged rendezvous. From this time until 11 a.m. I remained about the vicinity ready to support as necessary, intercepting various signals, which contained no information on which I could act."

* Torpedo Boat Destroyer Flotilla.

"At ii a.m. the squadron was attacked by three submarines. The attack was frustrated by rapid manoeuvring, and the four destroyers were ordered to attack them. Shortly after 11 a.m. various signals having been received indicating that the Commodore (i) and Commodore (2)* were both in need of assistance, I ordered the Light Cruiser squadron to support the torpedo flotillas."

* Submarines

"Later I received a signal from the Commodore (1) stating that he was being attacked by a light cruiser, and a further signal informing me that he was being hard pressed and asking for assistance. The Captain (3), First Flotilla, also signalled that he was in need of help.

"From the foregoing the situation appeared to me critical. The flotillas had advanced only ten miles since 8 a.m., and were only about twenty-five miles from two enemy bases on their flank and rear respectively. Commodore Goodenough had detached two of his light cruisers to assist some destroyers earlier in the day, and these had not yet rejoined. (They rejoined at 2.30 p.m.) As the reports indicated the presence of many enemy ships—one a large cruiser—I considered that his force might not be strong enough to deal with the situation sufficiently rapidly, so at 11.30 a.m. the battle cruisers turned to E.S.E., and worked up to full speed. It was evident that to be of any value the support must be overwhelming and carried out at the highest speed possible.

"I had not lost sight of the risk of submarines, and possible sortie in force from the enemy's base, especially in view of the mist to the southeast.

"Our high speed, however, made submarine attack difficult, and the smoothness of the sea made their detection comparatively easy. I considered that we were powerful enough to deal with any sortie except by a battle squadron, which was unlikely to come out in time, provided our stroke was sufficiently rapid.

"At 12.15 p.m. Fearless and First Flotilla were sighted retiring west. At the same time the Light Cruiser Squadron was observed to be engaging an enemy ship ahead. They appeared to have her beat.

"I then steered N.E. to sounds of firing ahead, and at 12.30 p.m. sighted Arethusa and Third Flotilla retiring to the westward engaging a cruiser of the Kolberg class on our port bow. I steered to cut her off from Heligoland, and at 12.37 p.m. opened fire. At 12.42 the enemy turned to N.E., and we chased at 27 knots.

"At 12.56 p.m. sighted and engaged a two-funnelled cruiser ahead. Lion fired two salvoes at her, which took effect, and she disappeared into the mist, burning furiously and in a sinking condition. In view of the mist and that she was steering at high speed at right angles to Lion, who was herself steaming at twenty-eight knots, the Lions firing was very creditable.

"Our destroyers had reported the presence of floating mines to the eastward and I considered it inadvisable to pursue her. It was also essential that the squadron should remain concentrated, and I accordingly ordered a withdrawal. The battle cruisers turned north and circled to port to complete the destruction of the vessel first engaged. She was sighted again at 1.25 p.m. steaming S.E. with colours still flying. Lion opened fire with two turrets, and at 1.35 p.m., after receiving two salvoes, she sank.

"The four attached destroyers were sent to pick up survivors, but I deeply regret that they subsequently reported that they searched the area but found none.

"At 1.40 p.m. the battle cruisers turned to the northward, and Queen Mary was again attacked by a submarine. The attack was avoided by the use of the helm. Lowestoft was also unsuccessfully attacked. The battle cruisers covered the retirement until nightfall. By 6 p.m. the retirement having been well executed and all destroyers accounted for, I altered course, spread the light cruisers, and swept northwards in accordance with the Commander-in-Chiefs orders. At 7.45 p.m. I detached Liverpool to Rosyth with German prisoners, seven officers and seventy-nine men, survivors from Mainz. No further incident occurred."

Of Commodore Tyrwhitt, the Commander of the Destroyer Flotilla, both Rear- Admiral Beatty and Rear-Admiral Christian (commanding the Light Cruiser and Torpedo Boat Destroyer Flotilla), spoke in the most unstinted terms of praise.

"His attack was delivered with great skill and gallantry," says the latter officer.

Admiral Christian also mentioned Commodore Roger T. B. Keyes in Lurcher.

"On the morning of August 28, in company with the Firedrake, he searched the area to the southward of the battle cruisers for the enemy's submarines, and subsequently having been detached, was present at the sinking of the German cruiser Mainz, when he gallantly proceeded alongside her and rescued 220 of her crew, many of whom were wounded. Subsequently he escorted Laurel and Liberty out of action, and kept them company till Rear-Admiral Campbell's cruisers were sighted."

As regards the submarine officers the Admiral specially mentions the names of:—

"Lieutenant-Commander Ernest W. Leir. His coolness and resource in rescuing the crews of the Goshawk's and Defender's boats at a critical time of the action were admirable, and Lieutenant-Commander Cecil P. Talbot. "In my opinion, the bravery and resource of the officers in command of submarines since the war commenced are worthy of the highest commendation."

Commodore Tyrwhitt's story takes us up into the thick of the fight.

"On Thursday, August 27, in accordance with orders received from their lordships, I sailed in Arethusa, in company with the First and Third Flotillas, except Hornet, Tigress, Hydra, and Loyal, to carry out the pre-arranged operations. H.M.S. Fearless joined the flotillas at sea that afternoon.

"At 6.53 a.m. on Friday, August 28, an enemy's destroyer was sighted, and was chased by the fourth division of the Third Flotilla.

"From 7.20 to 7.57 a.m. Arethusa and the Third Flotilla were engaged with numerous destroyers and torpedo boats which were making for Heligoland; course was altered to port to cut them off.

"Two cruisers, with four and two funnels respectively, were sighted on the port bow at 7.57 a.m., the nearest of which was engaged. Arethusareceived a heavy fire from both cruisers and several destroyers until 8.15 a.m., when the four-funnelled cruiser transferred her fire to Fearless.

"Close action was continued with the two-funnelled cruiser on converging courses until 8.25 a.m., when a 6-inch projectile from Arethusa wrecked the forebridge of the enemy, who at once turned away in the direction of Heligoland, which was sighted slightly on the starboard bow at about the same time.

"All ships were at once ordered to turn to the westward, and shortly afterwards speed was reduced to 20 knots.

"During this action Arethusa had been hit many times, and was considerably damaged; only one 6-inch gun remained in action, all other guns and torpedo tubes having been temporarily disabled.

"Lieutenant Eric W. P. Westmacott (Signal Officer) was killed at my side during this action. I cannot refrain from adding that he carried out his duties calmly and collectedly, and was of the greatest assistance to me.

"A fire occurred opposite No. 2 gun port side caused by a shell exploding some ammunition, resulting in a terrific blaze for a short period and leaving the deck burning. This was very promptly dealt with and extinguished by Chief Petty Officer Frederick W. Wrench, O.N. 158,630.

"The flotillas were re-formed in divisions and proceeded at 20 knots. It was now noticed that Arethusa's speed had been reduced.

"Fearless reported that the third and fifth divisions of the First Flotilla had sunk the German Commodore's destroyer and that two boats' crews belonging to Defender had been left behind, as our destroyers had been fired upon by a German cruiser during their act of mercy in saving the survivors of the German destroyer.

"At 10 a.m., hearing that Commodore (S) in Lurcher and Firedrake were being chased by light cruisers, I proceeded to his assistance with Fearless and the First Flotilla until 10.37 a.m., when, having received no news and being in the vicinity of Heligoland, I ordered the ships in company to turn to the westward.

"All guns except two 4-inch were again in working order, and the upper deck supply of ammunition was replenished.

"At 10.55 a.m. a four-funnelled German cruiser was sighted, and opened a very heavy fire about 11 o'clock.

"Our position being somewhat critical, I ordered Fearless to attack, and the First Flotilla to attack with torpedoes, which they proceeded to do with great spirit. The cruiser at once turned away, disappeared in the haze and evaded the attack.

"About ten minutes later the same cruiser appeared on our starboard quarter. Opened fire on her with both 6-inch guns; Fearless also engaged her, and one division of destroyers attacked her with torpedoes without success.

"The state of affairs and our position was then reported to the Admiral commanding Battle Cruiser Squadron.

"We received a very severe and almost accurate fire from this cruiser; salvo after salvo was falling between 10 and 30 yards short, but not a single shell struck; two torpedoes were also fired at us, being well directed, but short.

"The cruiser was badly damaged by Arethusa's 6-inch guns and a splendidly directed fire from Fearless, and she shortly afterwards turned away in the direction of Heligoland.

"Proceeded, and four minutes later sighted the three-funnelled cruiser Mainz. She endured a heavy fire from Arethusa and Fearlessand many destroyers. After an action of approximately twenty-five minutes she was seen to be sinking by the head, her engines stopped, besides being on fire.

"At this moment the Light Cruiser Squadron appeared, and they very speedily reduced the Mainz to a condition which must have been indescribable.

"I then recalled Fearless and the destroyers, and ordered cease fire.

"We then exchanged broadsides with a large four-funnelled cruiser on the starboard quarter at long range, without visible effect.

"The Battle Cruiser Squadron now arrived, and I pointed out this cruiser to the Admiral Commanding, and was shortly afterwards informed by him that the cruiser in question had been sunk and another set on fire.

"The weather during the day was fine, sea calm, but visibility poor, not more than three miles at any time when the various actions were taking place, and was such that ranging and spotting were rendered difficult.

"I then proceeded with fourteen destroyers of the Third Flotilla and nine of the First Flotilla.

"Arethusa's speed was about six knots until 7 p.m., when it was impossible to proceed any further, and fires were drawn in all boilers except two, and assistance called for.

"At 9.30 p.m. Captain Wilmot S. Nicholson, of the Hogue,* took my ship in tow in a most seamanlike manner, and, observing that the night was pitch dark and the only lights showing were two small hand lanterns, I consider his action was one which deserves special notice from their Lordships.

* The Hogue was afterwards destroyed by submarine.

"I would also specially recommend Lieutenant-Commander Arthur P. N. Thorowgood, of Arethusa, for the able manner he prepared the ship for being towed in the dark.

"H.M. ship under my command was then towed to the Nore, arriving at 5 p.m. on August 29. Steam was then available for slow speed, and the ship was able to proceed to Chatham under her own steam.

"I beg again to call attention to the services rendered by Captain W. F. Blunt, of H.M.S. Fearless and the Commanding Officers of the

destroyers of the First and Third Flotillas, whose gallant attacks on the German cruisers at critical moments undoubtedly saved Arethusa from more severe punishment and possible capture.

"I cannot adequately express my satisfaction and pride at the spirit and ardour of my officers and ship's company, who carried out their orders with the greatest alacrity under the most trying conditions, especially in view of the fact that the ship, newly built, had not been forty-eight hours out of the Dockyard before she was in action.

"It is difficult to specially pick out individuals, but the following came under my special observation:

H.M.S. Arethusa.

"Lieutenant-Commander Arthur P. N. Thorowgood, First Lieutenant, and in charge of the After Control.

"Lieutenant-Commander Ernest K. Arbuthnot (G), in charge of the Fore Control.

"Sub-Lieutenant Clive A. Robinson, who worked the range-finder throughout the entire action with extraordinary coolness.

"Assistant Paymaster Kenneth E. Badcock, my Secretary, who attended me on the bridge throughout the entire action.

"Mr. James D. Godfrey, Gunner (T), who was in charge of the torpedo tubes.

"The following men were specially noted:

"Armourer Arthur F. Hayes, O.N. 342026 (Ch.).

"Second Sick Berth Steward George Trolley, O.N. M.296 (Ch.).

"Chief Yeoman of Signals Albert Fox, O.N. 194656 (Po.), on fore bridge during entire action.

"Chief Petty Officer Frederick W. Wrench O.N. 158630 (Ch.) (for ready resource in extinguishing fire caused by explosion of cordite).

"Private Thomas Millington, R.M.L.I., No. Ch. 17417.

"Private William J. Beime, R.M.L.I., No. Ch. 13540-

"First Writer Albert W. Stone, O.N. 346080 (Po.).

"I also beg to record the services rendered by the following officers and men of H.M. ships under my orders:

H.M.S. Fearless.

"Mr. Robert M. Taylor, Gunner, for coolness in action under heavy fire.

"The following officers also displayed great resource and energy in effecting repairs to Fearless after her return to harbour, and they were ably seconded by the whole of their staffs:

"Engineer Lieutenant-Commander Charles de F. Messervy.

"Mr. William Morrissey, Carpenter.

H.M.S. Goshawk.

"Commander the Hon. Herbert Meade, who took his division into action with great coolness and nerve, and was instrumental in sinking the German destroyer V187, and, with the boats of his division, saved the survivors in a most chivalrous manner.

H.M.S. Ferret.

"Commander Geoffrey Mackworth, who, with his division, most gallantly seconded Commander Meade, of Goshawk.

H.M.S. Laertes.

"Lieutenant-Commander Malcolm L. Goldsmith, whose ship was seriously damaged, taken in tow, and towed out of action by Fearless.

"Engineer Lieutenant-Commander Alexander Hill, for repairing steering gear and engines under fire.

"Sub-Lieutenant George H. Faulkner, who continued to fight his gun after being wounded.

"Mr. Charles Powell, Acting Boatswain, O.N. 209388, who was gunlayer of the centre gun, which made many hits. He behaved very coolly and set a good example when getting in tow and clearing away the wreckage after the action.

"Edward Naylor, Petty Officer, Torpedo Gunner's Mate, O.N. 189136, who fired a torpedo which the commanding officer of the Laertes reports undoubtedly hit the Mainz, and so helped materially to put her out of action.

"Stephen Pritchard, Stoker Petty Officer, O.N. 285152, who very gallantly dived into the cabin flat immediately after a shell had exploded there, and worked a fire hose.

"Frederick Pierce, Stoker Petty Officer, O.N. 307943, who was on watch in the engine room and behaved with conspicuous coolness and resource when a shell exploded in No. 2 boiler.

H.M.S. Laurel.

"Commander Frank F. Rose, who most ably commanded his vessel throughout the early part of the action, and after having been wounded in both legs, remained on the bridge until 6 p.m., displaying great devotion to duty.

"Lieutenant Charles R. Peploe, First Lieutenant, who took command after Commander Rose was wounded, and continued the action till its close, bringing his destroyer out in an able and gallant manner under most trying conditions.

"Engineer Lieutenant-Commander Edward H. T. Meeson, who behaved with great coolness during the action, and steamed the ship out of action, although she had been very severely damaged by explosion of her own lyddite, by which the after funnel was nearly demolished. He subsequently assisted to carry out repairs to the vessel.

"Sam Palmer, Leading Seaman (G.L. 2) O.N. 179529, who continued to fight his gun until the end of the action, although severely wounded in the leg.

"Albert Edmund Sellens, Able Seaman (L.T.O.), O.N. 217245, who was stationed at the fore torpedo tubes; he remained at his post throughout the entire action, although wounded in the arm, and then rendered first aid in a very able manner before being attended to himself.

"George H. Sturdy, Chief Stoker, O.N. 285547 and

"Alfred Britton, Stoker Petty Officer, O.N. 289893, who both showed great coolness in putting out a fire near the centre gun after an explosion had occurred there; several lyddite shells were lying in the immediate vicinity.

"William R. Boiston, Engine Room Artificer, 3rd class, O.N. M.1369, who showed great ability and coolness in taking charge of the after boiler room during the action, when an explosion blew in the after funnel and a shell carried away pipes and seriously damaged the main steam pipe.

"William H. Gorst, Stoker Petty Officer, O.N. 305616.

"Edward Crane, Stoker Petty Officer, O.N. 307275.

"Harry Wilfred Hawkes, Stoker 1st class, O.N. K.12086.

"John W. Bateman, Stoker 1st class, O.N. K.12100.

"These men were stationed in the after boiler room and conducted themselves with great coolness during the action, when an explosion blew in the after funnel, and shell carried away pipes and seriously damaged the main steam pipe.

H.M.S. Liberty.

"The late Lieutenant-Commander Nigel K. W. Barttelot commanded the Liberty with great skill and gallantry throughout the action. He was a most promising and able officer, and I consider his death is a great loss to the Navy.

"Engineer Lieutenant-Commander Frank A. Butler, who showed much resource in effecting repairs during the action.

"Lieutenant Henry E. Horan, First Lieutenant, who took command after the death of Lieutenant-Commander Barttelot, and brought his ship, out of action in an extremely able and gallant manner under most trying conditions.

"Mr. Harry Morgan, Gunner (T), who carried out his duties with exceptional coolness under fire.

"Chief Petty Officer James Samuel Beadle, O.N. 171735, who remained at his post at the wheel for over an hour after being wounded in the kidneys.

"John Galvin, Stoker Petty Officer, O.N. 279946, who took entire charge, under the Engineer Officer, of the party who stopped leaks, and accomplished his task although working up to his chest in water.

H.M.S. Laforey.

"Mr. Ernest Roper, Chief Gunner, who carried out his duties with exceptional coolness under fire."

The remarkable character of this, the first and certainly the most comprehensive of naval despatches, is that it gives the crew and all branches of the naval service engaged. Battleship cruiser, light cruiser and torpedo boat destroyer alike gave their version and to these may be added the report of Commodore Keyes, who flying his broad pennant on Maidstone, commanded the submarines.

"Three hours after the outbreak of war Submarines E6 (Lieutenant-Commander Cecil P. Talbot) and E8 (Lieutenant-Commander Francis H. H. Goodhart) proceeded unaccompanied to carry out a reconnaissance in the Heligoland Bight. These two vessels returned with useful information, and had the privilege of being the pioneers on a service which is attended by some risk.

"During the transportation of the Expeditionary Force the Lurcher and Firedrake and all the Submarines of the Eighth Submarine Flotilla occupied positions from which they could have attacked the High Sea Fleet had it emerged to dispute the passage of our transports. This patrol was maintained day and night without relief until the personnel of our Army had been transported and all chance of effective interference had disappeared.

"These submarines have since been incessantly employed on the enemy's coast in the Heligoland Bight and elsewhere, and have obtained much valuable information regarding the composition and movement of his patrols. They have occupied his waters and reconnoitred his anchorages, and, while so engaged, have been subjected to skilful and well executed anti-submarine tactics; hunted for hours at a time by torpedo craft and attacked by gunfire and torpedoes.

"At midnight on August 26, I embarked in the Lurcher, and in company with Firedrake and Submarines D2, D8, E4, E5, E6, E7, E8, and E9, of the Eighth Submarine Flotilla, proceeded to take part in the operations in the Heligoland Bight arranged for August 28. The destroyers scouted for the submarines until nightfall on the 27th, when the latter proceeded independently to take up various positions from which they could co-operate with the destroyer flotillas on the following morning.

"At daylight on August 28 the Lurcher and Firedrake searched the area, through which the battle cruisers were to advance, for hostile submarines, and then proceeded towards Heligoland in the wake of Submarines E6, E7, and E8, which were exposing themselves with the object of inducing the enemy to chase them to the westward.*

* It was this daring manoeuvre which induced the German cruisers to move into the open sea.

"On approaching Heligoland, the visibility which had been very good to seaward, reduced to 5,000 to 6,000 yards, and this added considerably to the anxieties and responsibilities of the commanding officers of submarines, who handled their vessels with coolness and judgment in an area which was necessarily occupied by friends as well as foes.

"Low visibility and calm sea are the most unfavourable conditions under which submarines can operate, and no opportunity occurred of closing with the enemy's cruisers to within torpedo range.

"Lieutenant-Commander Ernest W. Leir, commanding Submarine E4, witnessed the sinking of the German Torpedo Boat Destroyer V187 through his periscope, and, observing a cruiser of the Stettin class close, and open fire on the British destroyers which had lowered their boats to pick up the survivors, he proceeded to attack the cruiser, but she altered course before he could get within range. After covering the retirement of our destroyers, which had had to abandon their boats, he returned to the latter, and embarked a lieutenant and nine men of Defender, who had been left behind. The boats also contained two officers and eight men of V187, who were unwounded, and eighteen men who were badly wounded.

"As he could not embark the latter, Lieutenant-Commander Leir left one of the officers and six unwounded men to navigate the British boats to Heligoland. Before leaving he saw that they were provided with water, biscuit, and a compass. One German officer and two men were made prisoners of war.

"Lieutenant-Commander Leir's action in remaining on the surface in the vicinity of the enemy and in a visibility which would have placed his vessel within easy gun range of an enemy appearing out of the mist, was altogether admirable.

"This enterprising and gallant officer took part in the reconnaissance which supplied the information on which these operations were based, and I beg to submit his name and that of Lieutenant-Commander Talbot, the Commanding Officer of E6, who exercised patience, judgment, and skill in a dangerous position, for the favourable consideration of their Lordships.

"On the 13th September E9 (Lieutenant-Commander Max K. Horton) torpedoed and sank the German light cruiser Hela six miles south of Heligoland.*

* Lieut. Max Horton was later to distinguish himself further, for he subsequently torpedoed a big German cruiser in the Baltic "A number of destroyers were evidently called to the scene after E9 had delivered her attack, and these hunted her for several hours.

"On the 14th September, in accordance with his orders, Lieutenant-Commander Horton examined the outer anchorage of Heligoland, a service attended by considerable risk.

"On the 25th September Submarine E6 (Lieutenant-Commander C. P. Talbot), while diving, fouled the moorings of a mine laid by the enemy. On rising to the surface she weighed the mine and sinker; the former was securely fixed between the hydroplane and its guard; fortunately, however, the horns of the mine were pointed outboard. The weight of the sinker made it a difficult and dangerous matter to lift the mine clear without exploding it. After half an hour's patient work this was effected by Lieutenant Frederick A. P. Williams-Freeman and Able Seaman Ernest Randall Cremer, official number 214235, and the released mine descended to its original depth.

"On the 6th October E9 (Lieutenant-Commander Max K. Horton), when patrolling off the Ems, torpedoed and sank the enemy's destroyer Si 26.

"The enemy's torpedo craft pursue tactics which, in connection with their shallow draught, make them exceedingly difficult to attack with torpedo, and Lieutenant-Commander Horton's success was the result of much patient and skilful zeal. He is a most enterprising submarine officer, and I beg to submit his name for favourable consideration.

"Lieutenant Charles M. S. Chapman, the second in command of E9, is also deserving of credit.

"Against an enemy whose capital vessels have never, and light cruisers have seldom, emerged from their fortified harbours, opportunities of delivering submarine attacks have necessarily been few, and on one occasion only, prior to the 13th September, has one of our submarines been within torpedo range of a cruiser during daylight hours.

"During the exceptionally heavy westerly gales which prevailed between the 14th and 21st September the position of the submarines on a lee shore, within a few miles of the enemy's coast, was an unpleasant one.

"The short, steep seas, which accompany westerly gales in the Heligoland Bight, made it difficult to keep the conning tower hatches open. There was no rest to be obtained and even when cruising at a depth of sixty feet the submarines were rolling considerably, and pumping, i.e., vertically moving about twenty feet.

"I submit that it was creditable to the commanding officers that they should have maintained their stations under such conditions.

"Service in the Heligoland Bight is keenly sought after by the commanding officers of the eighth submarine flotilla, and they have all shown daring and enterprise in the execution of their duties. These officers have unanimously expressed to me their admiration of the cool and gallant behaviour of the officers and men under their command. They are, however, of the opinion that it is impossible to single out individuals when all have performed their duties so admirably, and in this I concur."

There are things that must always be remembered, in estimating the work of the Navy. There are the peculiar nature of the task allotted to the Navy, the part it was expected to play in bringing about the end of the enemy's resistance, the difficulties and the enormous dangers it was called upon to share. These things considered, when we ask ourselves if the British Navy had carried out its part of the contract in the great war, there can be no other answer than an emphatic affirmative.

We were not fighting the German Navy, we were fighting the German nation.- Sheltered behind the men doing their splendid work up and down the seas were millions of people who looked to them for assistance in carrying out their daily avocations. They looked to the sea to bring them the means of livelihood, the raw materials to fashion into finished products, the coal, the iron ores, the fabrics, or the raw material of fabrics, and, vitally necessary, food to sustain life within the Empire.

Countries cannot live on themselves under modern economic conditions. They must have customers and clients to whom they must have access. When neither raw material is coming in nor completed manufacture going out, factories close down, many people are thrown out of employment, and labourers who were till then not only self-sustaining but were helping in the larger business of upholding the State, become a burden upon the nation.

So that, since Germany depended very largely upon seaborne trade, and since all her land borders save one were in the hands of the enemy, it is not difficult to understand the first duty of the Navy and the paramount importance of the task which was set for Admiral Jellicoe. It was a task which meant a constant hazardous patrolling and a continuous search of ships, neutral as well as enemy, since it has been found, and has been proved during the present war, that the German secured most of his advantages under a flag which was not his.

All this and more the Navy did, in its unwinking watch over the seas. Daily, hourly, our Navy spelt out the far-reaching significance of sea-power. In addition to its ceaseless patrolling, its tireless searching, which means the strangle-hold upon the trading of our enemy, it convoyed the great transports, with their war-material of men and guns, from the far places of the Empire.

It was not to be expected that its work could be carried on without mishap. Mine and raiding submarine were constantly at work against our ships. The nature of the work the Navy had to do made it, as it were, an enormous target for the enemy. Our own submarines had little chance of retaliating in like manner, for the German Navy lay behind the bolted doors of its secure harbours.

On page 35 is given a comparative list of disasters on the British and the German sides, up to the end of the first year of war. It will help the reader to understand the character of the naval war. It was of a character inevitable so far as our Navy was concerned.

The D5 was sunk as the aftermath of a visit of four German cruisers to our shores. A coastguard gunboat, the Halcyon, was engaged in patrolling early one misty morning, off Lowestoft, when the enemy's cruisers appeared. They fired several shots, damaging the Halcyon's wireless, and then made a prompt retreat at full speed. Although shadowed by some of our light cruisers, they could not be brought to action before dusk, and our pursuit was abandoned. One of these fleeing cruisers threw out a number of mines, and submarine D5 was sunk by exploding one of these.

It was afterwards learnt that the Yorck, a German cruiser which was presumably one of the squadron that had taken part in this spectacular but ineffective raid, had sunk owing to collision with one of the mines guarding Wilhelmshaven.

Of all the German ships the Emden gained the greatest notoriety, and it is a commentary upon the character of the British race that, in spite of the enormous amount of damage which the Emden did to British shipping—she paralysed the East Indian trade for over a month—the British people heartily admired the skill and courage of her Commander and crew, and paid willing tribute to the courtesy which Captain von Muller invariably showed to those who unfortunately came across the Emden's path.

When war broke out the Emden, a light armoured cruiser, was stationed at Kiao-chau, and possibly the inevitability of Japan joining in caused the German Admiralty to detach this light, fast cruiser to her work of destruction. Attended by colliers, she disappeared from the China seas, and reappeared in the Indian Ocean on September 10th.

The greater portion of the British fleet was at that time engaged in convoying the Indian contingent to Europe, so that the Captain of the Emden knew that he might with impunity come prowling through the Indian seas on the off-chance of picking up a few stray merchantmen. In this surmise he was justified, for in four days he had captured and sunk six merchant ships, removing their crews before sending the vessels to the bottom. On the 22nd the Emden suddenly appeared before Madras, and with an audacity worthy of the best traditions of the British Navy— upon which the German Navy was modelled—she bombarded this important Indian town, doing no more damage, however, than setting fire to a number of oil tanks. The time was night, and the bombardment only lasted for a quarter of an hour. Again she vanished, and news came of her in the Indian Ocean, where she went to work capturing and sinking the British merchantmen that came her way. An instance of Captain von Muller's humanity is cited in the case of the Kabinga. Yon Muller had intended sinking this vessel, when he found that the captain's wife was on board. He personally interviewed the lady.

"I cannot send you adrift in an open boat," he said with a twinkle in his eye, "so you must go back to England and tell the owners of the Kabinga that she is to be regarded as having been captured and sunk. . I present the ship to you."

And thus with a laugh he spared the boat.

In the middle of October H.M.S. Yarmouth, which had been ceaselessly searching for this pest of the ocean, came upon the Hamburg-Amerika liner Marcomania, and a Greek steamer which had been accompanying the Emden and carrying coal and ammunition for the vessel.

These two ships were promptly sunk by the British Commander, who could not afford at the moment to put a prize crew on board and send them into port. Undoubtedly this was a very great blow to the Emden; but between that period and October 22 she had sunk five more ships in the south-west.

The Admiralty recognised the feeling of unrest and insecurity which the presence of this ship created, and there was a concentration of fast cruisers, including French, Russian, and Japanese working in harmony with His Majesty's Australian ships Melbourne and Sydney, to search out and sink this danger to British commerce. Before she was captured, however, the Emden was to embark upon her last and most daring exploit.

Rigging an extra funnel to disguise herself, she steamed boldly into the roadstead at Penang, where there lay at anchor a Russian cruiser and a French destroyer. The new vessel's arrival was sighted by the officer of the watch on the Russian cruiser, and an interrogatory signal was flown to which the Emden replied "Yarmouth coming to an anchor." She came at full speed into the roadstead, and before anybody could realise what was happening she had slipped two torpedoes at the Russian, and then, as the French destroyer moved up to attack, she opened fire with both broadsides upon her two unprepared enemies, and sunk them at their moorings.

Nemesis was on her track, however. She went into Keeling Cocos Island with the object of destroying the wireless apparatus in that isolated spot, and the telegraph operator, recognising her, flashed out a warning signal which was picked up by the Minotaur and transmitted to H.M.S. Sydney.

The Emden landed a party which destroyed the instruments; but in the midst of their work of destruction the Emden's siren called them back. Before the landing party could reach the boat she was under way, for on the horizon loomed the grey hull of the Sydney, and her guns were already getting the range. The Emden's two funnels were shot away and she ran ashore, burning fiercely aft. Her losses were very heavy. The superior range of the Sydney's guns enabled the Commander of the Australian ship severely to damage his enemy without himself coming into range, except at the beginning of the action, when a well- placed shot by the Emden destroyed the range-finding apparatus and killed three men.

Simultaneously with the publication of this fine exploit came the news, no less encouraging, that another of the German commerce destroyers, the Königsberg, had been located up an East African river, and had been bottled up by the sinking of a collier in the fairway. The Königsberg was the ship which bombarded the Pegasus while it lay at anchor at Zanzibar.

In the Pacific a serious action off the coast of Chili resulted in our losing two cruisers, the Good Hope (the flagship of the Pacific Squadron) and the Monmouth. They tackled a superior concentration of German ships, including the Scharnhorst and the Gneisenau, which were lucky in having far heavier armament than the British ships possessed. The Glasgowsurvived and reached Valparaiso to tell the story of the unequal combat, Captain John Luce, of the Glasgow, having told the following story, a thrilling record of a gallant losing fight:—

"2 p.m.—Flagship signalled that apparently from wireless calls there was an enemy ship to northward. Orders were given for squadron to spread N.E. by E. in the following order:—Good Hope, Monmouth, Otranto and Glasgow, speed to be worked up to 15 knots.

"4.20 p.m.—Saw smoke; proved to be enemy ships, one small cruiser and two armoured cruisers. Glasgow reported to Admiral, ships in sight were warned and all concentrated on Good Hope.

"5.47 p.m.—Squadron formed in line ahead in following order: Good Hope, Monmouth, Glasgow, Otranto. Enemy, who had turned south, were now in single line ahead, 12 miles off, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau leading.

"6.18 p.m.—Speed ordered to 17 knots, and flagship signalled Canopus: 'I am going to attack enemy now.' Enemy were now 15,000 yards away, and maintained this range, at the same time jambing wireless signals. By this time sun was setting immediately behind us from enemy position . . . and while it remained above horizon we had advantage in light, but range too great.

"6.55 p.m.—Sun set, and visibility conditions altered, our ships being silhouetted against afterglow, and failing light made enemy difficult to see.

"7.3 p.m.—Enemy opened fired 12,000 yards, followed in quick succession by Good Hope, Monmouth, Glasgow. Two squadrons were now converging, and each ship engaged opposite number in the line. Growing darkness and heavy spray of head sea made firing difficult, particularly for main deck guns of Good Hope and Monmouth. Enemy firing salvoes got range quickly, and their third salvo caused fire to break out on fore part of both ships, which were constantly on fire till 7.45 p.m.

"7.50 p.m.—Immense explosion occurred on Good Hope amidships, flames reaching 200 feet high. Total destruction must have followed. It was now quite dark. Both sides continued firing at flashes of opposing guns. Monmouth was badly down by the bow and turned away to get stern to sea, signalling to Glasgow to that effect.

"8.30 p.m.—Glasgow signalled to Monmouth 4 enemy following us,' but received no reply. Under rising moon, enemy's ships were now seen approaching, and as Glasgow could render Monmouth no assistance, she proceeded at full speed to avoid destruction.

"8.50 p.m.—Lost sight of enemy.

"9.20 p.m.—Observed seventy-five flashes of fire, which was no doubt final attack on Monmouth.

"Nothing could have been more admirable than the conduct of officers and men throughout. Though it was most trying to receive a great volume of fire without chance of returning it adequately, all kept perfectly cool, there was no wild firing, and discipline was the same as at battle practice.

"When target ceased to be visible gun-layers spontaneously ceased fire.

"The serious reverse sustained has entirely failed to impair the spirit of officers and ships company, and it is our unanimous wish to meet the enemy again as soon as possible."

Admiral Cradock, who commanded the British squadron, had undoubtedly a force wholly inadequate to deal with the German vessels, should they decide upon a combination. The Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were superior to any ship which the British admiral had in his squadron, though the Good Hope could boast of two 9*2 guns, as against the 8-inch batteries of the enemy. But the 9 2, admirable weapon as it was in the days when it was the pet gun of the Navy, is a type of gun which was modern—twenty years ago. If you eliminate the 9'2 guns, then the British ships were at a great disadvantage to their enemy; for between them the German carried sixteen 8 2 guns, and no fewer than seventy- two smaller pieces ranging from 3*4 up to 5*9, as against the two 9'2 and forty- two other guns varying from 4-inch to 6-inch. The Scharnhorst and Gneisenau were two of the newest ships that Germany had launched, whilst on the other hand the Good Hope was a fifteen year old boat, and her main deck guns were so placed that in a heavy sea they were almost awash.

Recognising something of the danger, the Admiralty had detached an old battleship, the Canopus, to act with Admiral Cradock, but she unfortunately was without speed, though she carried 12-inch guns, which would give the British Squadron superiority over the enemy. The Canopus had not arrived, though it was apparently within signalling distance, on November 1st, when the Good Hope, sweeping slowly down the stormy sea off the south-west coast of South America, picked up a suspicious wireless message which suggested that an enemy warship was somewhere in the vicinity. The flagship sent a wireless to the Monmouth, the Otranto (a converted liner) and the Glasgow, to concentrate at a given point; and at half-past four that afternoon the British squadron, labouring through a heavy sea with a northerly gale, increasing every moment until it was almost a hurricane, blowing on their quarter, sighted smoke on the horizon, and presently made out a small cruiser and two armoured cruisers. Admiral Cradock's position was a dangerous one. He could recognise the gun superiority of his enemy. He could not afford to wait for the Canopus, a slow ship, nor could he afford again to lose sight of his elusive enemy. He signalled to form line ahead, and with the flagship leading, followed by the Monmouth, Glasgow, and Otranto, the squadron steamed inward, drawing closer every minute to the enemy. Both fleets were steaming in the same direction, and both altered their course inward to bring them together. It was a wild and impressive scene, that November night; the great, green waves, mountain high, the squadrons wallowing and rolling through the tumbling ocean, their decks awash and green sea sweeping over them. The sun was setting redly in the west, and the afterglow threw the ships of the British squadron into high relief, leaving the enemy veiled in the grey of the coming night. At seven o'clock fire was opened at 12,000 yards by the enemy, and the Good Hope, Monmouth, and Glasgow instantly came into action, the squadrons converging. The conditions were abnormal. Around the guns the men slipped and staggered as the shuddering vessels sunk and rose in the trough of the sea, and the icy blast of the hurricane shrieked along the unprotected decks and blinded the gunners with spray. Too soon the enemy's salvoes found their mark, and one of the 9*2 guns, which represented the only hope the British squadron had of outmatching the enemy, was put out of action a few minutes after the fight began.

With her smaller guns awash, with her big guns out of action, the Good Hope was a target for the great German cruisers to pound. Neither the Monmouth nor the Good Hope could make effective reply, and after half-an-hour of this unequal fight, both ships burning fore and aft, the Good Hope blew up amidships and went down in the dark. The Glasgow now moved off.

As we have seen by her Captain's despatch, she could render no assistance to the unfortunate Monmouth. This ship, with a bad list and making water rapidly, suddenly turned, signalling to the Glasgow to make for safety. "I am going to try to ram one of them," was her laconic signal, and that, and the stabbing pencils of gun fire in the dark, were all that the Glasgow could see of the doomed ship. Her gallant crew went to their death in a super-heroic attempt to destroy their enemy even in their last throes. Not a soul was saved from either the Monmouth or Good Hope.

Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee.

In that action the German ships engaged were the Gneisenau and the Scharnhorst, with the smaller Nürnberg. Both from the official account and from that supplied by eye-witnesses of the the fight, it does not seem that any other German vessel took part, and possibly the claim that the Nürnberg was the ship that gave the Monmouth her quietus was justified. Such a reverse, coming on the top of the success we had gained against the Emden, had a dispiriting effect, but the Admiralty acted with commendable promptitude. There was at Whitehall at this time Admiral Sturdee, who was acting as Chief of Staff to Lord Fisher. With no delay whatever he left his office chair, and, after the briefest instructions, journeyed to a certain port where the nucleus o%a new fleet was waiting, and hoisting his flag, set his squadron's bows direct for the eastern coast of South America.

We may suppose that the Japanese Fleet, already scouring the Pacific, were moving up in strength to force the enemy to leave the western waters. It is known that the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Nürnberg, Dresden and Leipzig rounded the Cape of Good Hope and moved up to that rendezvous where their colliers and their supplies were waiting. But within six weeks of their victory they paid the price.

It was a very strong squadron that Admiral Sturdee commanded, including the big battle cruisers, Invincible and Inflexible. On December 7th the British ships arrived at Port Stanley to coal, leaving the Canopus on guard outside the harbour. A fine intelligence system served Admiral Sturdee well, for on the very next day the German squadron under Admiral von Spee appeared (doubtless with the intention of seizing the islands and provisioning his ships) and, seeing only the Canopus—an easy prey—-advanced at once to the attack. Swiftly he discovered the trap laid for him, but not swiftly enough, for it was too late to run when the other British ships appeared and gave battle.

Since his defeat of Sir Christopher Cradock's squadron, von Spee had been harassed by the knowledge that English and Japanese ships were sweeping eastward in pursuit of him. But it is probable that he had been fairly confident that no new danger would threaten him from the Atlantic. Now, to his surprise, he had to face Sturdee's ships, their crews hot to avenge their fallen comrades.

From the beginning there could only be one end to the encounter. But von Spee, heavily over-matched, fought bravely on his flagship, upon which the British vessels at first concentrated their fire. At the end of an hour she began to settle, but she refused to surrender; at last her bow lifted out of the water, there was a great coughing of steam, and she went down with all on board. With the Gneisenau and the Leipzig it was the same.

The battle was not of long duration. The Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Leipzig were shot down with a loss to the Germans of probably 1,800 men, and the Nürnberg and Dresden utilising their great speed, sought to escape. This the Dresden succeeded in accomplishing, for she was three knots faster than her unfortunate companion. The Nürnberg, chased by fast cruisers, was destroyed by shell fire, and the Dresden slipped her pursuers, only to avert the evil day of her destruction, which from the first was inevitable.

Thus ended the great adventure which had begun with the declaration of war. It had seen the destruction of the Scharnhorst, Gneisenau, Emden, Leipzig, Nürnberg, and the bottling up of the Königsberg. Of the ships which Germany had sent out to harass the commerce of the Allies, only Karlsruhe and Dresden remained. Karlsruhe subsequently blew up whilst Dresden was finally brought to bay off the coast of Chili.

Throughout the war there was a certain co-ordination between the land and sea forces of the Crown which was apparent even to those unimaginative people who might not see at first glance what association there was between the destruction of von Spee's squadron and the safety of our army in France. Yet that association was very real. Sometimes the events on land had a very real connection with the naval position and in one case, the employment of the Monitors Severn and Mersey to shell the German trenches near Lombartzyde, the cooperation was expressed in a visible shape.

Toward the end of November the enemy was becoming desperate. The exhilaration which had been created in Berlin by the sinking of the Good Hope and the Monmouth off the coast of Chile, and by the victory which Germany had claimed to have inflicted upon the Russians, was replaced by a sense of depression and bitter chagrin when the news came that the fine Southern Pacific Squadron of the German Navy had been wiped out by Admiral Sturdee near the Falkland Islands. Add to this the fact that day after day had passed without any confirmation being received of the success which was supposed to have attended von Hindenburg's efforts against Warsaw, and you may realise something of that wave of impotent rage which swept across Germany, and induced the Great General Staff to find some desperate method of reviving the flagging spirits of the German people.

It was no heroic method that was chosen, no exploit undertaken which will live in German history as a deed of incomparable daring. Rather it is one of which the German will, in years to come, be loth to speak. On the night of November 15th five cruisers slipped out of Wilhelmshaven in the dark. Three of these were battle cruisers and two were light, unarmoured vessels; but all had the advantage of immense speed. A thick mist lay on the water, as with every light extinguished and steaming line ahead, the battle cruisers leading, the German fleet went at full speed westward. The journey was fraught with many dangers. British submarines and torpedo boats were patrolling the outer circle of German waters; cruisers were everywhere on the look-out for stray enemy craft. But the German evidently moved with complete confidence, for he was in possession of all the information he required as to the movements and the exact location of every British vessel. The system of espionage which had been going on in England ever since the war started served him in excellent stead. Not so excellent, however, but that the British Fleet learned at midnight that four or five vessels had succeeded in making their escape through the cordon, and in the early hours of the morning British battleship cruisers moved stealthily out from their bases and began to search the wide space of ocean for their enemy.

Seeking for enemy ships by night is a difficult matter under the most favourable circumstances. Looking for him in the early hours of that morning, when a sea fog covered the face of the water, was well-nigh hopeless.

Scarborough, the queen of British watering places, might well imagine war to be remote and apart from its own quiet, suave existence. People woke between seven and eight to a grey dawn and a thin driving mist, and may have felt some sense of satisfaction and pride when through the sea three great men-of-war came stealing cautiously towards the land. Scarborough itself, or such of Scarborough as was awake at that moment, had no doubt in its mind that these ships were British men-of-war. They had seen them before. The advent of battleships and cruisers was no new experience, and the few idlers on the sea front who were abroad at that hour speculated upon the names of these great grey shapes.

Then without warning the three ships belched fire. A strange new sound came to the peaceful people of the Yorkshire town. The dreadful scream of shell; the crashing of high explosives as the shells reached their objective; the frenzied cries of women struck down by murderous salvoes; the roar and tear of shattered buildings; the crashing of falling masonry; all these things told too plainly the almost unbelievable news that Scarborough, peaceful, unarmed and undefended, was the object of a German attack.

The raid itself, of course, had no military value whatever. So far from shaking the faith of the British, either in the justice of their cause or in the inevitability of their victory, the attack resulted in a great increase of recruits, for it brought home to even the most laggard of our fellow countrymen the realisation of the length to which the German would go to secure his ends. In a letter to the Mayor of Scarborough, Mr. Winston Churchill the First Lord of the Admiralty, designated the German squadron as baby-killers, and as baby- killers they will be remembered to the end of their days. The ignobility of the attack is, as I say, made evident by the complete suppression of the names of the ships which took part in the raid. It was not a matter of which any German sailor can be proud. There was an additional reason for secrecy to be found in the possibility of drastic reprisal if ever the captains of these ships fell into British hands.

The Scarborough raid, hailed with joy in Germany as an indication of Britain's inability to keep the seas, was successful only by the greatest of flukes. The British Admiralty had ample warning of the German intention, but their information led them to believe that the objective of the German Fleet was another part of the coast. To meet this raid a considerable force had been got together. When news came that the German had changed his plans and that he was already bombarding Scarborough, the Fleet set off with all haste to intercept the enemy, and would have succeeded in this object but for the fact that utilising a friendly fog bank, the German Fleet disappeared into the mist and made its escape.

The British Admiralty were equally well informed as to the departure of a Fleet which left Cuxhaven after dark on Saturday, January 23rd, and steamed slowly westward. It consisted of Derfflinger, Seydlitz, Moltke, Blücher, a number of small cruisers, including Kolberg, and a fleet of submarines and destroyers. When the news was received that this fleet was on its way, the British Battle Cruiser Squadron, under Admiral Sir David Beatty, consisting of Lion (flagship), Tiger, Princess Royal, New Zealand, and Indomitable, accompanied by a number of small craft, moved out to intercept the marauder, who was setting his course probably for Newcastle.

The composition of the enemy's squadron was interesting. Derfflinger was a brand-new ship, laid down only eighteen months previously and only completed for sea in November, 1914. She was perhaps the most powerful of Germany's battle cruisers. Moltke was a sister ship to Goeben, the Dreadnought cruiser which escaped our Fleet in the Mediterranean and ran for safety to the Dardanelles, afterwards being taken over by the Turk. Seydlitz was a very fast and powerful battle cruiser; Blücherwas a ship which was laid down in error, the Germans having received inaccurate information as to our ship- building intentions and having built Blücher with the idea of going one better than a mysterious ship which the British were building in one of the dockyards. That ship, as it happened, was Dreadnought, which, because of its size and its armaments, entirely negatived this effort of the German Admiralty, and established a new model for the world.

On the British side, Lion, a very powerful Dreadnought cruiser, was remarkable for its great speed. Tiger was not ready for the sea when war broke out, but Princess Royal, New Zealand and Indomitablehad all seen much sea service. Of these five Indomitable was the slowest. Cooperating with the battle-cruiser fleet was a destroyer flotilla, under Commodore Tyrwhitt who carried into action Arethusa and Undaunted, two ships which had already made their mark in the naval history of the war.

Unaware of the preparations which were being made to receive him, the German Admiral (probably Admiral Funke) came swiftly through the night, having distributed his instructions to his captains as to their objective. There is not much reason to doubt that that objective was again the undefended coast line.

The Marconi signallers on the German battleships, with their ear-pieces strapped to their heads, listened intently for any errant signal which would betray the presence of British warships. One signal alone came to them—the signal of a patrolling warship which was at that moment communicating with the shore a request concerning the domestic economy of the ship. Such a message was immensely gratifying to the German Admiral, who found in this innocent communication support for his faith in British unpreparedness.

The shock came at a little after seven in the morning, when, on the horizon, his look-out detected five pillars of misty smoke at suspiciously regular intervals. A scrutiny of these satisfied the German Admiral as to their nature. A string of signals fluttered up to his mainmast, and in obedience, this mighty fleet of Germany immediately swung round and headed for home with all speed.

At this time the ships of the British Fleet were not even visible to the naked eye. They were, indeed, no more than a blur of dun-coloured smoke upon the horizon, but the German Admiral, through his telescope, had been able to make out the composition of the force which was opposing him, and he was quite satisfied that discretion should be the better part of his valour.

Then ensued a thrilling flight, demoralising to the pursued, exhilarating to the pursuer, as every hour brought him nearer to his enemy. It was a pursuit carried out at first in silence, unbroken by roar of guns; a pursuit which was written in belching smoke that curled and trailed upon the dark green waters, and in the white fan of the flying warships' wake. Thirty miles had been covered by the racing ships, and the nearest British vessel was all but ten miles away when there came the first low rumbling thunder of the mighty British guns, and the shriek of a great shell. It struck the rearmost vessel, the Blacker, the slowest of the enemy fleet, and sent splinters of red-hot shell flying in all directions. It was followed instantly by another, and yet another; and then, as the British crept up hand over hand, the target was shifted from the rearmost ship, and Lion, leading the battle line, began dropping her shells upon Moltke and Seydlitz.

Moving at tremendous rates so that the two foremost British ships, Lion and Tiger, were well clear of their fellows these two began a continuous fire from their forward batteries, until at last they drew within long range of Derfflinger, and brought the whole of the German battle fleet under fire. And the German clapped on speed in his flight for home and the shelter of his mine field.

Back and forward went the quick exchange, Tiger engaging three ships at once, whilst the other ships of the line, Princess Royal, Indomitable and New Zealand, drew up to Blücher, which was now on fire fore and aft.

On Indomitable, the last of the line, the excitement had been intense. Would the slowest of the battle cruisers get up in time to join the fight? The stokers off duty ("the black squad ") settled that point. They volunteered to go down and assist their brethren in the deeps of the stokehole, that Indomitable might not be last in the hunt.

Stripped to the waist and tingling with joyful excitement they stoked Indomitable to such purpose that she pulled out four knots more than she had achieved upon her trials. And now the reward came. A signal to Indomitable, brief and to the point, "Settle Blücher!" brought this fine ship into action.

Blücher had heeled over and drawn out of the line, her fore turrets swept away, her bridge vanished, her steel tripod masts a mass of wreckage. With funnels battered and hanging limply, scarred and holed above and below water- line, she wallowed in the trough of the sea, still firing her guns desperately. Every British ship that passed her gave her one salvo, for she had been the craft which had begun the bombardment of Scarborough and the British gunners were saying "Remember Scarborough" as they fired. The end came when Tiger and Indomitable addressed themselves to the business of finishing Blücher for good.

Whilst this was going on, the German ships were rapidly approaching the mined sea area which had been prepared for such a contingency, a field lying fifty miles to the west of Heligoland. Here mines were thickly sown, and only ships having a complete knowledge of their position could be safe here.

It became evident to Sir David Beatty that he must break off action in a very short time, and he renewed his efforts to cripple the remainder of the German Fleet. Manoeuvring his ships so that he veiled them from the German gunners in the smoke which was pouring from the enemy's funnels, he drew closer, and the forward guns of Lion and Tiger thundered incessantly. The scene upon the battered German warships was indescribable. The shock and crash of exploding shells, which swept huge guns from their mountings as though they were toys, which destroyed men so that nothing was left of them, which made the very steel decks red-hot, drove some men mad.

Derfflinger was on fire forward, and flames were leaping up as high as the mainmast. Men from all the German ships were throwing themselves overboard, trusting to the hope of being rescued rather than to enduring that hell any longer. Moltke and Seydlitz, with fires blazing fore and aft, with the merciless shells dropping left and right, were in deplorable condition.

Then Lion met bad luck. A lucky shot fired by Seydlitz struck one of the feed tanks of the flagship and caused her to reduce speed, and at the same time enemy submarines were sighted to starboard of her. The German ships had reached the outer ring of the mine defences—a defence which they had elongated by the process of dropping overboard a number of mines in their flight. On the edge of the minefield lay the submarines, waiting their chance to defend the battleships; and when Sir David Beatty, realising that he had reached the margin of safety, decided to break off the action, these came out to attack Lion. Steaming with one engine, Lion steered to the north-west, and Admiral Beatty transferred his flag to one of the destroyers, and subsequently to Princess Royal. The starboard engines of Lionnow began to give trouble, and Indomitable took her in tow and brought her safely into port.

Now on the fringe of the minefield, with the advent of the strong submarine flotilla that had come out from Heligoland, the British Fleet was in danger. The long line of British destroyers which had been racing in the wake of the battle cruisers came up, and quickly assumed a formation which put them into a circle, the centre of which was the battle cruisers. Round and round at top speed the destroyers raced, ever widening their circle and ever keeping at a distance the baffled submarines. The great speed of the torpedo boat destroyer as compared with the slow-moving submarine rendered any possibility of attack upon the battle cruisers futile.

Other destroyers, standing by the place where Blücher had sunk, picked up as many of the exhausted men of that ship as they could, despite the operations of a German airship circling overhead, which, all the time, was attempting to drop bombs upon the rescuing destroyers.

Many of the men who were saved were in the last stages of exhaustion. Some were suffering from most terrible injuries; others were mad.

The captain of Blacker was taken on board one of the rescuing ships in a state of utter collapse.*

* He subsequently died in hospital.

In the morning these great cruisers of ours had trembled to the shock of explosions, and watchful men, in the dark, close confines of steel turrets, had worked their destructive guns. In the afternoon these same British sailors, relentless and remorseless, were searching their kits to provide clothing for the half-drowned, wholly chilled and utterly unnerved members of the enemy crews.

It was learned from the rescued men that the German Navy had sustained another complete loss. The Kolberg, one of the light cruisers, acting on the flank of the bigger ships, had been struck by over-salvoes which had passed their objective—the battle cruisers—and had sunk the smaller vessel. The German prisoners were agreed that she went down—a fact which the German Admiralty eventually denied.

It was a significant circumstance, which has been insufficiently commented upon, that the prisoners taken from the water consisted of representatives from all the ships of the flying German Fleet. In other words, the conditions had been so terrible upon the German warships which had escaped sinking, that men preferred death under the open sky and in the sea of icy water to a chance of life on these stricken ships.

Thus ended the second attempt of the German to reach the British coast, an attempt as ignoble in conception as it was disastrous in result. Our losses were:Lion, 17 wounded; Tiger, one officer and nine men killed, three officers and eight men wounded; Meteor, four men killed and one man wounded. The enemy losses were two ships and about 800 men. It was necessary to tow Lion and Meteor out of the area, but nearer to port Lion had sufficiently recovered to be able to come into harbour under her own steam. The injuries to the ships themselves were unimportant.

The battle was fought on Sunday, January 24, between the hours of 7.30 and 3 o'clock.

The work of the British airmen—both naval and army branches—was consistently excellent throughout, and as time went on, the British flying man, capable, resourceful, and daring, acquired ascendancy over his German rival. It is more convenient to deal first with the exploits of the naval branch of our air service.

Royal Naval airmen had accomplished a daring flight to Düsseldorf, destroying the Zeppelin shed there and with it one of the newest Zeppelins; and the success of that raid struck something like dismay into German hearts. The temper of the German people, which is represented in all the official accounts as steady and calm and most admirably confident, may best be gauged from the fact that it was necessary for the Military Commander at Cologne to issue special orders and injunctions to soothe the panic-stricken population, which for twenty years or more has been persistently told that, whatever might be the result of a war in which Germany was engaged, it was certain that the people of the interior towns would never hear the sound of a shot fired by an enemy.

The Zeppelin threat was one which had been held over Great Britain, not so much, one imagines, to terrorise our people as to keep the German folk in good heart.

The headquarters of the Zeppelin industry were at Friedrichshafen, on Lake Constance and it was known in the early days of November that two or three new Zeppelins were in course of manufacture at this place. Three British airmen decided upon the most daring raid that the war so far had produced. This was none other than an attempt to reach Friedrichsfaven from the French frontier and to destroy the Zeppelins in course of construction.

Three well-known men in the Naval Air Service were chosen for the work— Squadron Commander Briggs, Flight-Commander Babington and Flight-Lieutenant Sippe. Squadron Commander Briggs was one of the best air pilots we have had, a man who had put up the British altitude record to 15,000 feet.

The attempt involved a considerable amount of preparation, a very careful study of maps, and a reconnaissance, as far as it was possible to make one, for the first hundred miles of the flight. The statement made by Germany that our airmen were aided by information improperly conveyed by our diplomatic representatives in Switzerland needs no confutation. We had fought always with clean hands, and we had never yet utilised the territory or the sympathy of neutrals in order to secure our ends. This is not a claim which can be repeated with any truth by our enemy.

The attempt was made from Belfort, and early one grey morning, in the presence of the superior officers of the French garrison, who were the only people in the secret, the three gallant Britons began their flight. It was a flight without parallel in the history of this war, which has produced so many precedents. It carried the aviators over wild country, across high mountains, where every care had to be taken that the neutrality of Switzerland was not violated. For in these days nations claim the air as their territory just as assuredly as they claim the land below. The weather was intensely cold, and the gallant British airmen encountered, in one period of their flight, a very strong wind which caused them no little anxiety, threatening as it did the untimely termination of this adventure.

One of the aviators lost his way in a bank of cloud just before the objective was reached, and emerged to see Commander Briggs, shot at by anti-aircraft guns and shelled in all directions, making a steep dive down to the air shed where the new Zeppelin was building. Then, and only then, when he was sure of his ground, did Commander Briggs drop his terrible bombs. There was a burst of flame and smoke, but, undeterred, the second airman came swooping down in that inferno and dropped other bombs to complete the attack. In wide circles the aviators came back to their elevation, the wings of their machines riddled by rifle and shrapnel shot. Briggs alone fell, but steadied his flight and landed with little or no injury. For a few moments he was surrounded by an angry crowd, but a pointed revolver kept them at a respectful distance, until, on the arrival of an officer with some soldiers, the gallant Commander surrendered. It is reported, and we can only hope that the story is unfounded, that when the German officer discovered that the revolver with which the airman had been threatening his men was unloaded, he lashed his prisoner across the face with a riding whip.

The perils of his two companions were not at an end. If they had come unperceived, they were not to leave the country without risk. The news of their presence was telegraphed from town to town; motor-cars mounting machine guns and anti-aircraft cannon were dispatched at full speed to the most likely points; observers were specially detailed to watch the Swiss border and to note whether these adventurers crossed the frontier. But such was the extraordinary speed with which the airmen returned, that scarcely had the news of their arrival been received than the airmen themselves were over the place to which communication had been made and were out of sight before any effective step could be taken to intercept them.

The two officers, Lieutenant Sippe and Lieutenant Babington, were flying within sight of one another and at such a height that when they did come within the sphere of German anti-aircraft guns they defied every effort of the enemy to bring them down.

On the great barrack square of Belfort the French Commander waited anxiously as hours passed without news coming to him of the result of the raid. Situated as Belfort is, so close to the German frontier, it was impossible that the French should gain any news of the absent airmen from any distance, and the first intimation that the General and his Staff received was the sudden appearance in the air of two swooping aeroplanes which dived down on to the square and came to a halt within a few paces of where the Staff was waiting.

For this service the three officers, including Commander Briggs, were awarded the Legion of Honour by the French Government.

At Düsseldorf and Cologne it might reasonably have been supposed that the enemy was immune from attack, that they lay too far within their own borders to be subjected to the indignity of a bombardment at this stage of the war. Friedrichshafen, still farther away from the French frontier, never imagined that so outrageous a thing would happen as an attack upon its Zeppelin shed. But if there were two places which apparently were more secure than any other from attack either by land or sea, they were Wilhelmshaven and Cuxhaven. These, indeed, might be called the very sanctuary of Prussian naval life.

With waters protected by minefields thickly sown, with batteries placed at every point which commanded the approach of the Elbe, with Zeppelin bases left and right, and the whole of the German Navy anchored within reach of the Kiel Canal, the defences were so strong it would need more than an ordinarily desperate adventurer to place his head in the lion's mouth.

An air raid upon Cuxhaven was never seriously thought of by the German naval and military authorities, and no adequate provision was made to fight off such a raider. What was very clear to the German was that the nearest hostile land was separated by some 350 miles of water and that a raider would necessarily be compelled to make a 700 mile journey in the air. As it proved, such a journey was not necessary.

On Christmas Eve, Undaunted and Arethusa, attended by a small flotilla of fast torpedo boat destroyers, moved out of one of our ports and made their way across the North Sea. Piled high on the decks of these little cruisers, the newest and some of the most efficient of Britain's ships, were seven water planes.

There are certain of His Majesty's ships which are specially equipped for carrying water-planes ready for launching. One of these is Hibernia. Certainly neither Undaunted nor Arethusa were so equipped, and a strange sight they must have presented as they moved across the heaving waters with their strange cargoes. Their objective was a point not many miles south of Heligoland. It was no sudden raid against an undefended coast line, no hurried bombardment that this fleet had in view—a bombardment of a few minutes followed by a precipitous flight to safety—but a calm and leisured attack upon the very heart of the German naval service.

That they were sighted almost instantly is evident.

The Zeppelins on the island were first brought into action. They came looming from their great sheds, and rose upward, moving over the waters, already alive with submarine craft. The British captains knew their danger; they also knew the limitations of the enemy's submarines.

They must remain at a distance which would enable them to operate without fear of being struck by the British shells. Even here they were in some danger if they so much as put their periscope above water. They had, however, torpedoes, and these they launched against the daring raiders. The fast ships, such as Undaunted and Arethusa, had little to fear from torpedo attacks, so long as they knew the quarter from which that attack would be launched. The torpedo in its course through the sea leaves a distinct track, and the turn of a wheel will enable a fast moving cruiser to sweep clear from its path. Even against aircraft the dirigibles were ineffective, for here their uselessness was also clearly demonstrated. Three shells from the Undaunted driven straight into the air and bursting in alarming proximity to one great gasbag, set it swirling about, and another three sent up from the Arethusa completed the rout. The enemy's aeroplanes managed to get somewhere over the cruisers—a position in which it was impossible to shell them—and dropped several bombs, none of which, however, found its mark.

For three hours this extraordinary combat went on—a fight between a little sea-going fleet and the unseen peril which lurked in the ocean's depths, and the whirling terror which circled far above the cruisers.