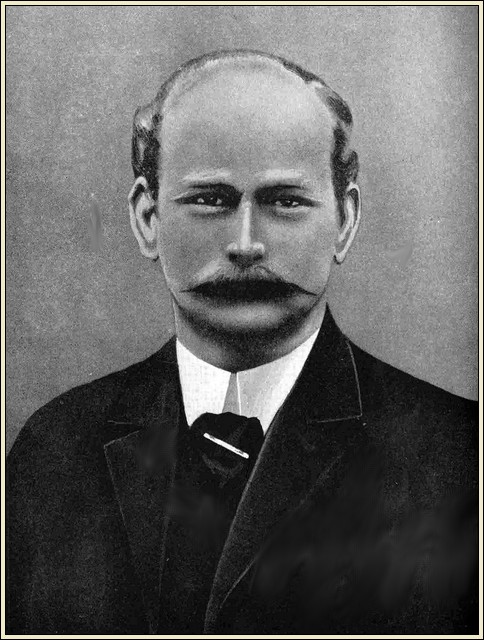

Frederick Henry Seddon.

IN the long record of sinister and evil men who make up the world's murderers, there are many duplications. In a dozen cases one sees the same motive, the same dominant ego, the same half-crazy reasoning, which induces otherwise sane people to commit the acts which bring them to the gallows. The unique criminal, unique in his method or in his circumstances, occurs at long intervals. Murders induced by jealousy are many; crimes based on vanity occur in considerable numbers. But seldom do we find a case resembling, and never a case parallel with, that of Frederick Henry Seddon, who, together with his wife, was tried in March, 1912, for the murder of Eliza Mary Barrow.

SEDDON was essentially a business man, shrewd, near, a little unimaginative. He was the type sometimes met with in the train on the way to the City: a man of dogmatic opinions, a little over-bearing, wholly intolerant of other people's opinions. You could imagine Seddon holding rigid political views, and regarding all who did not share them as being outside the pale.

Generally he was accounted, by those who knew him best, as a very excellent manager; a man who gave nothing away, and who was credited with considerable possessions, which his thrift and his gift for driving a hard bargain had accumulated for him.

Seddon lived in a good-sized house at Tollington Park, North London, with his wife and five children. It was a fairly large house and his own property (as he often boasted), and here he carried on his profession of insurance agent, being superintendent of that district and having under his charge a number of collectors, who were kept very busy by their energetic taskmaster. Seddon was certainly a man bound to get on. In the interests of his business he worked day and night; he was indefatigable in his search for new "lives," yet found time to indulge in certain social amenities, and was an officer of a very honourable society, where he was considerably respected.

That Seddon was a true Freemason in the real sense of the word can be doubted. Men of his intelligence too often adopt Masonry as a means to an end, believing that fellowship with so many of the best intellects in a district gives them advantages in business. Nevertheless, it was his ambition to rise to the supreme heights of Masonry, and all his spare time was given to the assiduous study of the craft and to fitting himself for higher office than that which he at present held.

A mean, hectoring man, bombastic of speech, loud of voice, that crushed all opposition, his business grew rapidly, but not so fast as he could wish. The dominant passion of Seddon's life was money. Not every miser is a recluse, who hides his bags of gold in inaccessible places and shrinks from the society of his fellow-men. There are some, who are to be met with in every sphere of commercial activity, well-groomed misers who are not to be suspected of their vice, and Seddon was one of these. He worshipped money for money's sake. He never spent a farthing that he could avoid. His household accounts were most minutely examined day by day, and the money he doled out for household expenses was the smallest sum he could in decency offer to his unfortunate wife.

Seddon's dreams had a golden hue. The rich were very wonderful in his eyes, and he would find his recreation in relating to his friends his surprising knowledge of the wealth which was possessed by the great figures of the financial world.

He had saved penny by penny, pound by pound, gradually piling up his assets painfully and slowly. Never once had a large amount come to him in one sum, and one of his bitterest complaints was that he had no rich relations who were likely to die and leave him a fortune. Not the least interesting item of the newspapers was the paragraph which appears every day under the heading "Latest Wills," and he would pore over this in the evenings. Sometimes he would learn of a rich man or woman who had died intestate, the money going to the Crown, and this would throw him into a fury.

"All that money wasted! Thrown into the gutter! It is criminal!"

THERE was in London, though of her existence Seddon was ignorant for some time, a middle-aged woman who shared Seddon's peculiar passion for money. She, however, had never had to scrape and strive. She had been left a small fortune in the shape of house property—at least it was a small fortune to her—which brought her in £5 or £6 a week. She was as mean as Seddon, parting with every penny with the greatest reluctance, and worshipping money, even as he did, for money's sake.

It follows that she was a difficult tenant to any landlady who gave her accommodation, and she shifted her lodgings very frequently, taking with her the small boy whom she had adopted, Ernie Grant.

In his restless search for people whom he could persuade to take out insurance policies, Seddon came into contact with this middle-aged spinster, Miss Eliza Barrow, and these two sharp-minded beings recognised in one another kindred souls. Seddon's immediate interest in the woman was a purely business one, but he had ever an eye to the main chance, and it had been his practice to leave no avenue to fortune unexplored.

"Friends should pay dividends," was one of his mottoes; and there is little doubt, after he had discovered that Miss Barrow was not a likely subject for insurance, that he turned over in his mind a way by which this new acquaintance should "pay dividends." Miss Barrow's complaint against landladies was perennial. Her interest in life was confined by the walls of the lodgings she had, and it may be imagined that they had not long met before she was telling him of her various landladies' enormities, the high cost of living, the peculations of lodging-house servants, and the difficulty of finding a home where these causes for distress would be more or less non-existent.

Seddon was a quick thinker. He had a big house in Tollington Park, and several of the upper rooms were unoccupied. This woman could pay dividends in the shape of rent, and in many other ways was a desirable tenant, for he had learnt of her house property and her steady income, and there was no fear that she would come to him on a Monday morning and bring excuses instead of money. So Seddon patted the little boy on the head with easy benevolence, and remembered his empty rooms.

"I think my rooms would suit you very well," he said. "We live very quietly; you will be in the house of a successful business man who may be able to help you from time to time in the matter of advice, and I'll arrange it so that you live more cheaply with me than you have been living heretofore."

The arrangement was most welcome to the woman, who was in the throes of one of her periodical fits of resentment against her landlady.

She had lived in many homes. Once she had stayed with her cousin, Mr. Frank Ernest Vonderahe, but that arrangement had not been satisfactory, and she had wandered off with her boy to yet another lodging.

Life at Tollington Park was entirely to Miss Barrow's satisfaction. She had the opportunity of talking business with Seddon; he admitted her to his confidence, allowed her to be present when he was handling the large sums of money which came in from the collectors—a sight very precious to Miss Barrow, who, in spite of her possessions, had probably not seen so much gold before. And the knowledge that he was trusted with such huge sums increased her confidence in him; so that she brought her own financial difficulties to him (the cost of repairs, tenants' demands and the like), and accepted his advice on all matters concerning her estate.

The friendship grew to a stage probably beyond her anticipations. Her confidence came to be a blind trust in his integrity and prescience. It developed, as was subsequently discovered, in her taking the rash step of purchasing an annuity upon his advice.

It is certain that Frederick Henry Seddon saw in Eliza Barrow a greater profit than the meagre sums he obtained by giving her lodging. There was about him the additional flavour of deep religious principles. Seddon had a reputation as a lay preacher and public orator. He was fluent of speech, better educated than most men of his class, and he could be, in his lighter moments, a most entertaining and charming man. He charmed Eliza Barrow to this end, that one day he induced her to sell her Indian stock for £1,600, to get rid of her house property and to trust him with the money. She was obviously confident, from his manner to her adopted child, that the boy would lose nothing from being left in Seddon's charge, for she made no provision whatever for his future until a few days before her death.

Seddon had gone to work deliberately, with a set plan, and the first part of his scheme having been brought to a successful issue, nothing remained but to perpetrate the dreadful deed which he may have contemplated from the very moment he had obtained Miss Barrow's confidence.

Since no poisoner has ever confessed his method, it is only possible to reconstruct the story of such a murder by an understanding of the murderer's mentality, and by piecing together such scraps of evidence as are available.

Seddon probably purchased a small quantity of arsenic in some part of London in which he was unknown. But he was shrewd enough to prepare, at the same time, a defence for himself. He purchased a number of fly-papers—paper impregnated with arsenic, which, when placed in a wet saucer, destroys any fly which lights upon it—and several of these he placed in Miss Barrow's bedroom.

He knew, for he had made a study of poison trials, that one of the questions which decides the guilt or innocence of any person accused of poisoning, is the accessibility of the poison: in other words, whether it is possible, through accident or design, for poison to be self-administered.

The only way that arsenic could be self-administered by a demented or careless woman was to have strong solutions of arsenic in her bedroom. He did not apparently realise that, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred where a person is found poisoned, the police look for a motive, and find one in a case where a person who had the opportunity of administering the poison directly benefits by the death.

"Seddon always thinks of everything," said an admiring colleague. "That is why he has been so successful."

Undoubtedly Seddon thought of most of the possibilities, but never dreamt that his cunning plan would be exposed.

In many ways Miss Barrow was most favourably placed from his point of view. She had quarrelled with her relations, and those very distant relations. She had no personal friends, and beyond the Vonderahes, who came occasionally to see her, and were received with marked coldness, no interfering individual who would inquire too closely into her sudden demise.

THE Seddon's family were on very good terms with their lodger. Maggie Seddon and her mother did the cooking for her. Seddon himself was seldom in her room. When she became ill, only on one occasion did Seddon give Miss Barrow her medicine. A doctor was called in, saw nothing suspicious, identified Miss Barrow's symptoms with a natural derangement; and if he was surprised when one day he was summoned to find the unfortunate lady in extremis, it was one of those surprises which are the normal experience of every medical practitioner, and he did not hesitate to give a certificate stating that her death was due to natural causes.

Three days before her death, Seddon persuaded Miss Barrow to make a will leaving all that she possessed to Ernest and Hilda Grant, appointing Seddon the sole executor. Again we see the cleverness oi the move; for now Seddon had so arranged matters that suspicion would be even more remote from himself. He had no possible interest in her death (unless the secretly-arranged sale of the annuity came to light), and such sums of money and property which had been Miss Barrow's as would be left he might use until the children came of age.

Miss Barrow died on the Thursday, and no sooner was the breath out of her body than Seddon bustled off to interview an undertaker, and arranged for the cheapest possible funeral. Not only did he do this, but he made a gruesome bargain with the man which gives us an interesting insight into his mastering desire to save money at every opportunity. Seddon told the undertaker that an old lady had died in his house, and it would have to be an inexpensive funeral. He had found four pounds ten in the room, he said, and that would not only have to defray the funeral expenses, but find the fees due to the doctor. Thereupon the undertaker bargained to carry out the funeral at an inclusive price of three pounds seven and sixpence and allowed Seddon a small commission on the transaction. Seddon had memorial cards printed, with an appropriate verse of sorrow; he bought a quantity of black-edged envelopes and paper, and wrote a number of letters, which, however, were never delivered or posted.

No man could have taken greater precautions than did Seddon to clear himself of any suspicion that he was implicated in the death of this wretched lady. Miss Barrow died on the Thursday, and on the Saturday was buried in a common grave, although there was a family vault, about which Seddon could not have been ignorant. He was, however, anxious to get the body underground with the least possible delay, for, once buried, he knew that there would be considerable difficulty in getting an exhumation.

Although not on specially good terms, Miss Barrow had been in the habit of calling on the Vonderahes, and the fact that she had not appeared, and that they had seen nothing either of her or the boy, was remarked upon by Mrs. Vonderahe.

"I can't understand why we have not seen Miss Barrow for so long," she said to her husband. "Why don't you walk round to Tollington Park and see how she is getting on?"

Ernest Vonderahe, who was not particularly interested in his cousin, was nevertheless a dutiful relative, and on the Wednesday evening strolled over to Tollington Park. The door was opened by Seddon's general servant, Mary Chater, who stared at him blankly.

"I've come to see how Miss Barrow is getting on. Is she well?"

The girl gasped.

"Haven't you heard?" she demanded in amazement. "Miss Barrow is dead and buried—didn't you know?"

Vonderahe could only stare at her.

"Dead and buried?" he said incredulously. "When did she die?"

"Last Thursday."

"But this is only Wednesday!"

"She was buried on Saturday," said the maid.

"Can I see Mr. Seddon?"

The girl shook her head.

"He's out, and won't be back for an hour," she said.

Staggered by this startling news, Vonderahe went back and saw his wife. At his suggestion, she dressed, and they went back again to Tollington Park, arriving about nine o'clock in the evening. This time they saw Maggie Seddon, the daughter, but Seddon was not visible.

"Father has gone to the Finsbury Park Empire and won't be back till very late," she said, and could give them little or no information about Miss Barrow's illness, nor did they think it worth while to question the child.

The Vonderahes went home and a family council was summoned, consisting of Vonderahe and his brother, with their wives, and they discussed the mysterious suddenness of Miss Barrow's illness until far into the night, arriving at the decision that the two women should interview Seddon the next morning and discover more about the circumstances of the woman's death.

Accordingly, the next morning the two wives went to Tollington Park, and the door was again opened by Maggie Seddon. Apparently they were expected, for they were shown immediately into the dining-room. The visitors were kept for some time before the insurance superintendent and his wife made their appearance. He was his usual self, calm, confident, neatly dressed and in every respect self- possessed. But his wife displayed the greatest nervousness, and, throughout the interview which followed, was on the point of breaking down.

Seddon strode into the apartment, pulled out a watch (which proved to be the property of the late Miss Barrow), looked at it significantly, and remarked in a loud tone that he hadn't much time to spare and he hoped that they would be brief. And then, when his wife began to speak, he silenced her firmly but kindly.

"Now, my dear, you're too much upset to be able to tell anything," he said, and explained that his wife had been greatly shocked by the death of the lodger and had not yet recovered. "You sit there and don't upset yourself. I can tell these ladies all they wish to know."

Mrs. Seddon may have had a suspicion that all was not well. The manner of Miss Barrow's death, the haste of the funeral, may have seemed to her suspicious things.

"Now," said Seddon briskly, "just tell me who you are, and what relation you are to the deceased Miss Barrow" And, when he was told, he handed them a copy of a letter written to Vonderahe, which the latter had not received.

The letter was brief and to the effect that Miss Barrow was dead. It invited them to the funeral which had taken place on the previous Saturday. It added that, a few days before her death. Miss Barrow had left a will in which she gave "what she died possessed of" to Hilda and Ernest Grant, and appointed Seddon as sole executor.

Apparently Seddon had everything prepared: the copy of the letter, a funeral card, a copy of the will, and a large blank envelope into which he put these documents and handed them to one of the ladies present.

So far, in spite of the brusqueness of the man—his callous indifference to the feelings of Miss Barrow's relatives and the scarcely veiled antagonism he showed to these inquirers—there was nothing suspicious beyond his manner; and it is probable that, had Seddon been more conciliatory, expressed a little more sorrow, and stage-managed that interview a little more deftly, he might have escaped the consequence of his villainy.

As it was, he again looked at his watch pointedly, and when one of the ladies asked if he would see Mr. Ernest Vonderahe he shrugged his shoulders.

"I am a business man, and I think I've wasted quite enough time on this matter," he said. "I really can't be bothered answering questions put by inquisitive people."

These two ladies had gone to Tollington Park with the misguided idea that, because of their relationship, they would be asked to take possession of Miss Barrow's effects. If the will were genuine, and her death had occurred under normal circumstances, they could not, of course, touch a single article without permission from the executor; and legally, Seddon's position was unassailable.

But in their ignorance of the law, they expected to be given certain of Miss Barrow's goods. Their real suspicions began when they found that, justifiably, Seddon meant to retain in his possession all the property the administration of which had been specifically left to him. It was only when they found that they were being sent empty-handed away from Tollington Park that they began to regard Seddon's behaviour as suspicious; and his ignorance of their psychology was responsible for his undoing.

It was not till some weeks later, on October 0th, after many family councils, that Mr. Ernest Vonderahe saw Seddon. The insurance agent had gone to Southend for a holiday, feeling, he said "a little under the weather." And that period gave Ernest Vonderahe an opportunity of making closer inquiries into the possessions of Miss Barrow when she died. He discovered something about her investments; she was the landlady of a public-house called the "Buck's Head," and the proprietress of a barber's shop adjoining the public-house; had a considerable sum of money in the bank, and at the time of her death had quite a large sum in ready cash.

Whether the relatives of Miss Barrow were chiefly concerned with the manner of her death, or whether they suffered under an indignant sense of being robbed of that which was rightfully theirs, we need not inquire. All the investigations which went on were in the direction of ascertaining the exact amount of benefit Seddon might have received from the woman's disappearance. It was a very proper and natural line of investigation, to which no exception could be taken. It is perfectly certain that, supposing the will to be genuine—and this was not disputed—whatever might be the result of their inquiries, they themselves could not be benefited by a single penny through the exposure of Seddon as a murderer.

The Vonderahes saw something of one of the "beneficiaries" under the will. Little Ernie Grant came to see them, but was invariably accompanied by one of Seddon's children, either the girl or the boy, and the suspicions of the Vonderahes were deepened, because they saw, in this chaperonage, an attempt to prevent them questioning the child as to the manner of Miss Barrow's death.

On Seddon's return from Southend, Vonderahe decided to call upon him, and sent him a message to that effect. And the visitor was accompanied by a friend "as witness." Seddon had no illusions as to the antagonism of the deceased woman's cousin. He had heard something more than the subterranean rumbling which was to precede the cataclysm, and his line of preparation—to meet the unspoken charges which he knew Vonderahe would have in mind—took the shape of adopting towards his inquisitor a lofty and high-handed manner, which had served him so successfully in dealing with other disagreeable people in his business.

Like all poisoners, Seddon was completely satisfied of his own invincibility. He was as confident as Armstrong had been up to the day of his death. He could even challenge still greater antagonism by attempting to cow his inquisitive visitors into submission to his point of view. Vonderahe and his friend were in the parlour, cooling their heels, for twenty minutes before Seddon and his wife came into the room.

"MR. Frank Ernest Vonderahe?" asked Seddon, and, when the relative had answered in the affirmative, Seddon spoke to the second of the men, under the impression that Vonderahe's companion was his brother.

Seddon was smoking a large cigar, and motioned his visitors to chairs with a lordly air.

"Now what is all this about?" he asked. "You are under the impression that some money is due to you from the estate of Miss Barrow? The will is perfectly clear, and I don't see why I should give you any further information. If your solicitor cares to see my solicitor, all very well and good."

In spite of this high-handed proceeding, Ernest Vonderahe began to question the man.

"Who is now the owner of the 'Buck's Head'?" he asked, referring to one of the properties which had been Miss Barrow's.

"I am," said Seddon quickly, "and the barber's shop next door is also mine. I've bought the property—in fact, I am always open to buy property if it shows any chance of a reasonable return. This house is mine, and I have a number of other properties. That is my private business: I buy and sell whenever a bargain is offered."

The propriety of Seddon's purchasing properties of which he was the executor for his own benefit, did not seem to have occurred to either of the two men, and Ernest Vonderahe shifted his inquiries to a complaint that his relative had been buried in a common grave, when there was a handsome family vault at Highgate available.

Seddon replied that he thought the vault was full up, though this excuse might have been invented on the spur of the moment. The "Buck's Head" and the barber's shop had, he declared, been bought in the open market. It was his business to dispose of the property, and as his bids were higher than any others, there was nothing remarkable about it being knocked down to him. When they pressed their inquiries, Seddon said (I am quoting the statement of Ernest Vonderahe):

"That is for the proper authorities to find out. I am perfectly willing to meet any solicitor. I am prepared to spend a thousand pounds to prove that all I have done in regard to Miss Barrow is perfectly in order."

Until this interview, according to the evidence which was subsequently offered at the trial of Seddon, the inquiries and the suspicions had been confined to the narrow circle of the Vonderahes and their intimate friends. But after this point-blank refusal of Seddon to discuss the affairs of the dead woman, and when it seemed that no useful purpose would be served by further interviews, the Vonderahes did what they should have done in the first place—communicated their suspicions to the police.

Such communications are not rare at Scotland Yard, and the police authorities act with the greatest circumspection before they take any drastic action to confirm the suspicions of relatives. There are probably twenty complaints to every exhumation; possibly the number is much larger. But the police, in this case, had something else to work upon than the bald suspicions of the Vonderahes. There was, in the first place, the hasty burial, and, in the second, the fact that, as executor or direct beneficiary, Seddon had obtained a number of effects which were the property of the deceased woman and which were now under his control. The doctor was interviewed by the police and, strengthened by his evidence, the Home Office made an order for the exhumation of the body.

These forces were at work all unknown to Seddon, who went about his daily business, satisfied in his mind that, if he had not allayed the doubts in the mind of Ernest Vonderahe, he had at least so baffled him, by his bold challenge to put the matter into his solicitor's hands, that no further trouble need be anticipated.

Removed to the cemetery mortuary, the body was examined by Drs. Wilcox and Spilsbury, now Sir William Wilcox and Sir Bernard Spilsbury, the Home Office pathologists. Certain organs were removed and forwarded for analysis, and the body was reinterred.

It was a grim coincidence that Seddon's business took him to St. Mary's Hospital at the time when Miss Barrow's remains were undergoing chemical examination, and that he was shown over a portion of the laboratory whilst that examination was in progress!

The chemist's report to the Home Office was emphatic: a very large quantity of arsenic had been found in the remains, and on this report the Home Office ordered an inquest.

Seddon was working at his accounts one night, when his daughter came to tell him that a policeman wanted to see him.

"A policeman?" said Seddon. "What does he want? Ask him to come in."

The officer walked into the room, helmet in hand, and handed him a paper.

"I am the coroner's officer," he said, "and this is a summons for you to attend an inquest on the body of Eliza Barrow, which will be held to- morrow."

Not a muscle of Seddon's face moved. Eliza Barrow! Until that moment he had not known that an exhumation order had been made. This was his first intimation that the net was closing round him.

When the officer had departed, Seddon swept aside the work on which he had been engaged, and sat down, coolly and calmly, to work throughout the night, packing his wife and children off to bed, whilst he prepared answers to such questions as might be put to him.

The grey dawn of a November day found him haggard and drawn, his table littered with papers covered with his clerkly writing. He had prepared for every possible contingency; had an answer for every question which might possibly be put to him; had checked and compared answer with answer, so that his story should be logical and convincing.

The inquest lasted for the greater part of a fortnight. And now suspicion became certainty. Seddon's conduct, tested and probed, did not react, as he had hoped, to his advantage. On December 4th he was arrested on the charge of murdering Eliza Barrow.

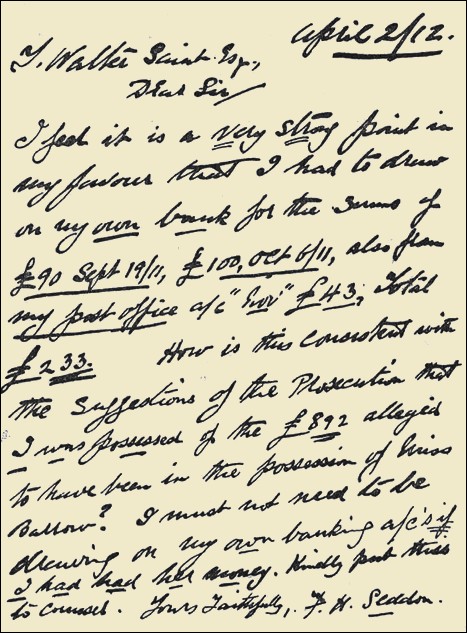

Facsimile: Letter written by Seddon in the

luncheon interval just before the dismissal of his appeal.

For more than a month, while he was nder arrest, his wife was allowed her freedom. But as the law officers examined more closely the evidence available, it was obvious that Scddon's wife was also under suspicion; and, to the amazement and idignation of the murderer, she was arrested on January 15th, 1912.

Seddon plied the detectives with questions as to the nature of the poison, and as to whether it might not have been self-dministered. "It was not carbolic acid, was it?" he asked. "There was some in her room. Have you found arsenic in the body?"

All Seddon's transactions with the deceased woman now came into the light of day, and, incidentally, the motive for the murder. Miss Barrow had converted a considerable amount of her shares, of which she possessed some £1,600 worth, into cash, and purchased from Seddon an annuity of some £155 per annum. Whilst she lived, he had to pay her £3 5s. a week, and it was to save this paltry sum, in the belief that she would live many years, that Seddon had murdered her. The transaction in itself was not unusual. Seddon, as an insurance superintendent, dealt in annuities, but this time the transaction was carried out for his own benefit. The will, therefore, leaving everything she possessed to Ernie and Hilda Grant, was a hollow document which meant nothing, since her only possessions at the time of her death were the cash she had at her bank and her own personal possessions.

The trial, which began at the Old Bailey in March, 1912, before Mr. Justice Bucknill, excited general interest. The Attorney-General, Sir Rufus Isaacs, now Viceroy of India, appeared for the prosecution; Sir Marshall Hall, then Mr. Marshall Hall, defended the man; whilst Mr. Rentoul, now Judge Rentoul, defended Mrs. Seddon.

Throughout the trial, Seddon kept up that unemotional detached attitude which he had shown from the very moment of his arrest. Mrs. Seddon, on the other hand, was a sad and dejected figure. She could indulge in none of the breezy exchanges which Seddon had with his counsel, nor could she regard with equanimity a visit to the witness-box, which Seddon welcomed rather than otherwise.

Seddon depended upon the fact that no person had seen him administer poison to the deceased woman. And this, as has already been pointed out, is the basis of confidence in the case of every man or woman charged with murder by poison. It was as though he put into words the attitude of such men:

"I am willing to admit that the woman died of poison. I admit that I benefited considerably by her death, but you cannot prove that I gave her the poison. I may have brought food to her, and unless the prosecution can, beyond all possible doubt, prove that poison was in that food, and placed there by me, you must return a verdict of Not Guilty."

Never in the history of criminal jurisprudence has there been a case where a convicted poisoner has been detected in the act of administering poison, either in food or otherwise. The poisoner banks upon suspicion being equally attached to other persons than himself, and thus securing the benefit of the doubt. Seddon's confidence was fated to receive a terrible shock. After an hour's deliberation the jury returned with a verdict of "Guilty" against Seddon, and "Not Guilty" against Mrs. Seddon. Seddon bent over and kissed his wife; in another minute they were separated, never to see one another again except through the intervening bars.

The Clerk of Arraigns put the usual question: "What have you to say that the Court should not give you judgment to die according to law?" And then occurred the most dramatic and, to many people in the court, the most painful incident of the trial. Seddon stood stifily erect and began a long speech which declared his innocence. He ended by making a Masonic sign which was unmistakable to Mr. Justice Bucknill, himself a Freemason: "I declare before the Great Architect of the Universe that I am not guilty, my lord." The judge was visibly distressed, but, recovering himself instantly, passed sentence of death, and Seddon paid the penalty for his crime at Pentonville Gaol on April 18th, 1912.