The articles in this PGA/RGL compilation were originally published in the British daily newspaper The Morning Post. The texts given here were for the most part extracted from the New Zealand Evening Post. The scanned versions of the original articles can be viewed at the "PapersPast" website, which is maintained by the National Library of New Zealand. A link to the digitised version of each article is provided via the attribution line following the article's title.

Two articles—"Charlotte's" and "99, Something Crescent"— were not included in the first PGA/RGL edition of The England (January 1912). These and the illustrations in the present edition were extracted from a PDF image file of the book download from the Bodleian Library, Oxford, England.

Edgar Wallace introduces this collection with the words:

"These little bits of observation and experience are reprinted from the Morning Post. They might be more pretentiously and truthfully entitled Leaves from a Journalist's Notebook—but I refrain! With all their imperfections I dedicate them to the Master Writer of our Amusing Trade, Rudyard Kipling."

I STOPPED my car before the gates to admire the little house. It is one of those picturesque old places that are all angles and gables. And there are high poplars and beautifully trimmed hoi hedges and a velvety little lawn as smooth as a billiard table.

In summertime there are flowers, gold and scarlet and blue, in the wide beds fringing the lawn—now one must be content with the green symmetry of box and laurel and the patch of deep red which marks Molly's chrysanthemums. Behind the house is a very serious vegetable garden and a field where chickens stalk. And an orchard—about two acres in all.

Such a house and grounds as you might buy for some twenty-five hundred or three thousand pounds. Perhaps cheaper, for it lies away from railways and is off the main road. Town folk would call it lonely, though it is entitled to describe itself as being on the fringe of the London area.

Somebody lives here (you would say if you did not know) with a comfortable income. A snug place—the tiny week-end home of some stockbroker who does not want the bother and expense of the upkeep of a more pretentious demesne.

There was no need to ask the owner of the cottage that nearly faces the oaken gates, because I am in the fullest possession of all the necessary facts.

"Mrs. F— lives there. Oh, yes, she's lived there for years. She's a lady... I don't know anything about other people's business, mister."

This latter in a manner that is both suspicious and resentful. If Mrs. F— were immensely rich, our cottager would advertise her splendours; reticence he would not know. Mrs. F— isn't rich. She's immensely poor.

Molly, who met me halfway across the lawn, put the matter in a phrase. "We are 'The-Crashed,'" said Molly definitely, "and we try not to be Poor Brave Things—Poor Brave Things get on Mummie's nerves. Mrs. G— is a poor brave thing, and writes to the newspapers about it—well perhaps she doesn't exactly write to the newspapers, but she sort of gets her name in as the officer's widow who is beginning all over again to build her war-shattered fortune by designing furniture."

Molly is fourteen, and at Cheltenham. The bare fact of the "crash" and its cause are recorded, on one of the many memorials that one passes at crossroads on the way to the races.

To the Glory of God

and the Memory of

the following Officers,

Non-Commissioned Officers

and Men of the

Royal Blankshire Regiment,

who fell in the Great War.

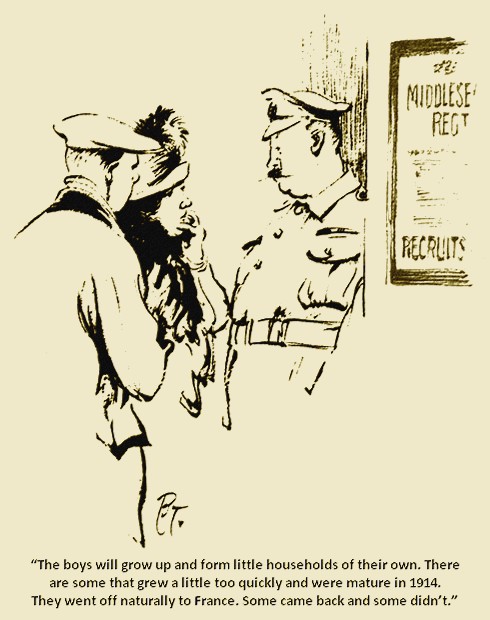

Molly's father got his majority in June, 1914—I forget to what, pension his widow, is entitled under the Royal Warrant. He left a small house in Berkshire that needed a lot of repairs, an old car that he had bought secondhand, a couple of hunters, a lot of odd dogs, and four children—three girls and a boy.

Oh, yes, and (as Molly reminds me) four hundred shares in Somethingfontein Deeps.

He, was killed early in the war, before he had time to save money, and everybody was terribly sympathetic, especially about Molly, "who was three, or some ridiculous age.

Molly's mother had some well-off relations—not rich, but people who kept two or three gardeners and had a flat in town. So there was a family council, and everybody agreed that the small house in the country should be sold, and Molly's mother should take an even smaller house. Family councils of this kind always advise selling the house and getting something smaller. Happily, nobody wanted to buy the little mansion unless big repairs were effected, and electric light put in and parquet flooring and running water in every room, and all that sort of thing. Molly's mother worked it all out,on a piece of paper when the children were in bed, and discovered that the repairs would cost a little more than the house would fetch, in the open market. So she elected to stay on. She had one maid, who refused to leave her, and a gardener so deaf that he couldn't be told that his services were dispensed with.

Molly's mother had two hundred a year to live on and four children to educate.

"Mother decided to breed rabbits, which are notoriously prolific," said Molly. "It was the only poor brave thing she did. But she got terribly self- conscious about them, and confined herself to chickens—which are natural. Anybody can keep chickens without it getting into-the papers. She did try hard to write love stories, but she said they made her sick. I read one the other day, and it made me sick, too. Mrs. Griffel, who has the cottage down the road, was another war widow. Lord L—, who owns most of the land round here, gave her the cottage, and she has two tons of coal and all sorts of things. Nobody gave us anything, because, we were supposed to be gentry. I asked Mummie if she would have taken two tons of coal, and Mummie said, 'Like a shot!' But nobody offered, and we had one fire going besides the kitchen for years. It was terribly cold in the winters."

Education was an important matter. Tom had to go to Rugby, because Molly's father went to Rugby. The well-off relations helped, though their prosperity was diminishing with the years. The richest and most generous was a shareholder in certain coal mines, and dividends began to flutter like a bad pulse.

There was no question of "keeping up appearances." Molly's mother didn't care tuppence who knew of her poverty. She used to journey on a push bike every Saturday to Reading to buy in the cheapest market. And this small, sharp-featured lady was a terrible bargainer. She is not pretty—wholesome, but hot pretty. She cast no sad, appealing glance at susceptible butchers; she quoted glibly wholesale prices, and grew acrid when frozen mutton was offered in the guise of Southdown.

There was some help for Tom at Rugby—either an inadequate Government grant or a scholarship. One of the girls had only a year to stay at school when the crash came. Molly's elder sister began her education at a moment when coal mines were paying concerns—Molly was unfortunate in beginning her first term at Cheltenham under the cloud of an industrial crisis.

The two hundred a year has remained two hundred, but Molly's mother has performed miracles. Tom is at Woolwich, and Molly is at Cheltenham. God knows how she balances her budget, and what fierce and urgent appeals to the well-to-do relatives are slipped into the letter-box at the end of the lane. She does what cannot be done—adds two and two and makes it six.

I suspect Molly knows—she is so insistent upon that one point they are not Poor Brave Things.

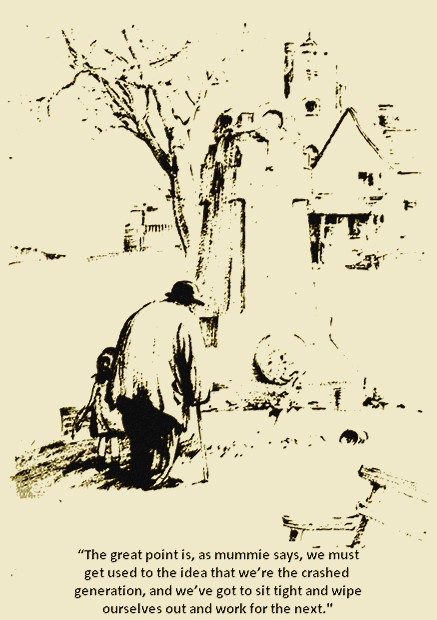

"Getting married is going to be the bother." Molly was terribly, serious. "We're all so devilishly plain" (she uses this kind of language occasionally) "and unfortunately none of us is romantic—I mean we don't want be nurses or go on the stage or do anything eccentric. The great point is, as Mummie says, we must get used to the idea that we're the crashed generation, and we've got to sit tight and wipe ourselves out and work for the next. And Mummie says that there are hundreds and thousands of us, and we're jolly lucky to have a house and not live in lodgings, Tom thought he ought not to go into the Army because of the awful expense, but that's all rot. Mummie says that ashes without a Phoenix are just dirt."

Molly's mother is only one of the crashed, as she says. But for Molly, who is rather loquacious, you might never hear of them, because they are most awfully scared of attracting attention, or qualifying for admission to the Society of Poor Brave Things. Up and down the land, in out-of-the-way villages, in obscure lodgings, in very populous suburbs, the regimental ladies who crashed are keeping step with Molly's mother.

MY friend the Communist (a very nice man) only knows two classes, the Idle Rich and the Proletariat.

"People without regular jobs." I suggested, having looked it up for crossword purposes.

No, he meant "Proletariat."

"Wage earners?"

No, he still meant "Proletariat," but what that meant he wasn't quite sure.

"Karl Marx—"

He beamed.

"That's the fellow—what he says—"

"Wage labourers—wage earners," said I. "Only the people who work for a living are the proletariat."

My friend was rather depressed by this narrow interpretation of his grand word.. Anyway (here he brightened) the Idle Rich were, not to be explained away by the dictionary.

"Look at 'em! Any night you like in the West End! Motor-cars, fal-de- lals, wimmin, wine!"

"And song," I helped him, but he was not grateful.

"Go down to the Savoy any night you like," he stormed. "I've heard 'em on the wireless, laughing and clapping their hands for more music. And I've seen 'em through the windows at other places, sitting at tables and drinking wine— the price of every bottle would keep a family from starvation for a week! And outside on the Embankment, people without a shelter to their heads or a crust to eat. That's what is going to bring about the revolution!"

Because I am interested in revolutions I went to the cradle of the coming upheaval.

I do not know a nicer cradle or a more cheerful-sounding. To hear it all on the wireless is one thing, to be a participator is another.

The buzz and blare of the ballroom is not so noticeable as through the microphone. You scarcely hear the tuning of fiddles or the twink-twank of an absent-minded thumb on a banjo string. These things fit into a larger sensation— shaded lights and amber candelabras and the glitter and gleam of silver on white tables, and flowers and white-shirted diners, and beautiful women, and women who hope they are looking that way. The idle rich were having a most strenuous time.

The last time I met the idle rich youth who grinned at me from the next table was somewhere between the Baldock and Stevenage. He had come down from Cambridge, driving an awful-looking little car that he had wheedled from his idle rich father (one of those wealthy suffragan bishops who earn nearly £800 a year), and he begged from me the price of a two-gallon tin of juice. He had only a shilling in his pocket; his term allowance of £10 having been squandered in the riotous pursuit of pleasure and those hectic gaieties which are such a deplorable feature of University life.

He told me later that he had been invited to dinner by a topping fellow (the father of another undergraduate), that he was having a topping time. The topping fellow who invited him (a largish man with a cherubic smile) was another of the idle rich. He was an official of a big engineering company and spent most of his life sleeping on trains and interviewing hardfaced men who bought machinery. When he wasn't sleeping on trains he was sleeping on ships hound for foreign parts, or sleeping on ships bound for home. His wife manages to see him for two months in the year.

He doesn't dance, but he likes to see the young people enjoy themselves. There is wine on his table. Every magnum represents more than the fortnight's salary he received when he started work with the company he now controls. He sits a little dazed, a little absent, his mind completely occupied with centrifugal pumps and machine-tools, watching the brilliant throng gyrating to the rhythm of the band. The beautiful women in their indescribable dresses, the chameleon changes of hues, the subtle fragrances which come to nostrils used to the scent of lubricating oils and hot metals.

I like to reduce things to table form: pages of statistics fascinate me. Here is a census of the known idle rich within view:—

(1) A retired tea planter from Assam. Age about 50. Very rich. He had ten years of heart-breaking labour, rising at dawn, working in the plantation all day, and sleeping in a little bungalow a trifle larger than a suburban summer house by night. Worked like a navvy, seven days a week, and took no holiday during the first years of his apprenticeship. Paced season after season of disappointment and partial failure till the luck turned. Now he is home and trying to recover the wasted years.

(2) A director of a big newspaper combine. The most cheerful soul that ever came from Scotland. Spent his early married life in a one-roomed lodging, denied himself more than the bare necessities to ensure against unemployment; employed his spare hours in work.

(3) A rather imposing man who looks like a Cabinet Minister. A gossip writer in one of the newspapers. A hard-working and not particularly brilliant man, who is earning his living at this moment.

(4) A theatrical "magnate" who once peddled shoelaces in New York.

(5) The son of an impoverished Irish peer, wounded in the war, and himself working in a city office.

(6) A millionaire distiller who battled up from 6s a week clerkship, and who in the evening, of life, finds his chief pleasure in watching young people enjoying the life he was denied.

It is impossible that the census could be complete. Idle rich? I know a few. By some mysterious, wise workings of Nature, rust and rot go together, and one looks for the idle rich in queer places where nice people do not go. They run to poetry of an exotic kind and to strange friendships. Some write nasty little plays. Mostly they live on the association of nasty little people, and move in a cloud of sycophants and parasites. One reads regularly of their doings in gossip paragraphs—there is one writer who specialises in such a chronicle. Now. they are on the Lido, extravagantly costumed or engaged in lunatic games; now they are at Deauville; now doing something extraordinary or bizarre in London itself. They have Baby Parties, where they array themselves in the costumes of childhood, or Treasure Hunts, or officiate at mysterious gatherings. You never see them on a race-course or in the hunting field. They may appear at St. Moritz or in ten costumes per diem, but they do nothing more exciting than pose for their photographs.

And in due course they die, and their estates are divided amongst their wholesome relatives, and that is the end of them.

But this Savoy ballroom belongs to youth, gilded but not golden; wearing the uniform of affluence, but no more. Money doesn't worry the subaltern down for a short leave. He isn't giving the party, but he is the soul of it. He asks for nothing more than a pretty partner, a syncopated jig-tune, perfectly timed, and his. enjoyment is in ratio to his partner's dancing ability.

He is young and good-looking, fresh-faced, bubbling over with energy. He has no money, and doesn't want much. He needs for the moment a perfectly topping time. Good wine is wasted on him. He can never remember the menu. He would as soon drink lemonade. He has not learnt to call things and people "divine." Mostly he talks about cars—fast, ugly, uncomfortable cars—but fast.

He may not be in the Army or the Navy. Perhaps he is in the motorcar business, which has an irresistible fascination for youth. Or in an office. You know that he is "public school" from the moment that you hear him speak—it really does not matter whether he is soldiering or selling buttons.

There is a waiter at the Savoy who is a great friend of mine; we have this bond of union, that we went to the same school, and he knows more about the idle rich than any man in London.

"Is there anybody here who does nothing for a living?" I asked. He knew a man from the Argentine and another from France who had no occupation but dancing.

"But English?"

He took a careful survey of the room. It must have been an off night for the idle rich, since he could; only; distinguish one man.

"And he's a member of Parliament!" he said, almost apologetically.

HE isn't a tramp. He very seldom leaves the West End and never goes out of London. He is very unwashed and wears two overcoats, and I have never seen him begging. Shuffling along by the edge of the pavement, his downcast eyes seeking a cigarette-end, he would be an object of pity, if compassion could overcome nausea.

The women of his species you can find any afternoon or evening, sleeping in the doorway recesses of West End theatres. Why she chooses theatres nobody knows, unless they are the only public, buildings about the doorways of which it is permissible to loiter without incurring the censure of the police. She is terribly grimy and carries a market bag in which she stores the treasures she finds in her waking hours.

Everybody associated with charitable work has tried to help them both— the Impossible Man and the Impossible Woman. They have been prayed over and bathed and given good food and good advice and money and clothes and disinfectants; but they have gone back to The Life and the two overcoats and the gallery entrance of St. Martin's Lane.

A lady friend of mine who had incited her husband to kill a former lover, and was tremendously well known in consequence, once told me that the spectacle of the Impossible People was a shame and a disgrace to England.

"We wouldn't stand for it in New York," she said.

So you see how badly we compare with New York, and even Chicago, which has two murders a day, but no Impossible People. Because they wouldn't stand for it.

In warmish weather, when charitable well-to-do folks, their hearts glowing with loving kindness and wine, dash down to the Embankment and distribute largesse to the submerged, the Impossible People gravitate towards the Embankment. They occupy most of the available seats and huddle themselves up in odd corners, looking oh, so wretched, and they take their share of what is coming.

In the winter they keep to the brighter, warmer spots, knowing that loving kindness doesn't often square with cold feet, and that slumming comes more natural on a warm, moonlit night in June than in the icy blasts of December, when a north-easter is blowing and horribly cold rain is liable to trickle down the necks of vicarious philanthropists.

I dislike the Impossible People because they are like the small boys who are always getting in the way of the photographer who is snapping the genuine article.

There is one called Old Frank, whom I have known for years. This frowsy man was old and dirty in 1910. He has slept out of doors ever since (except for a month he spent in Pentonville), and soap advertisements are meaningless to him There he is—a shuffling old body with his three waistcoats and cardigan jacket, alive and fit. There has been a war. Thousands of men have passed in their prime. Millionaires and princes, with all the resources of medicine and surgery at their command, have been gathered to their fathers. Old Frank, who sleeps in the oddest corners, and garners his meals in unbelievable places, is prime and hearty.

I have only given him one penny in my life. He remembers the circumstance vividly. He also remembers all the air raids.

"Frank, there is only one remedy for you,—and that is a lethal chamber," I told him when I met him a few nights ago.

He was not offended.

"There ain't many of us left now," he said, regretfully. It was as though he were speaking of a decaying industry—you might have imagined that he was a flint-knapper or something of the sort.

He named about thirty impossible people, all males, and could, with an effort, have named a hundred.

He was once a soldier, and got a wandering fit on him when quite a young man. He became a tramp in the more noble sense, but the country was too lonely, and farmers kept dogs and rural policemen were entirely unsympathetic In the country the Vagrancy Act is a real, vital thing. In London it is a curiosity. He "did" three weeks in Exeter Prison and three weeks in Gloucester, and so he came back to London, where the police are kind. He was not sorry for himself, but regretted the passing of two old friends of his, one of whom had been knocked down by a motor-omnibus a few months before.

"These motors oughtn't to be allowed," he considered.

Unlike his kind, who take an intensive interest in themselves, are casually concerned about their fellow-unfortunates, and are wholly oblivious of the phenomena of life that appear daily before their eyes, Old Prank is sensitive to economic conditions.

"There's less regulars on the pavement," he said, "but there's more outsiders than any time I can remember. They come and go and don't stay long. Young fellers, some of 'em, out of work and not used to the road. Gentle chaps, clurks, and what not. Some of 'em had good positions, too—orficers in the army. They drift in an' drift, out."

You can watch the drift if you spend a night at the "Morning Post" home— a place where wretchedness loses for a while some of its depressive quality. Here come the pieces that refuse to fit into the jigsaw puzzle called Economic Life. Some have lost all shape and belong to the waste section that go into the rag-bag. Some are only momentarily lost to place. Youngish men, rather bewildered, rather ashamed, by this glaring emphasis of their inadequacy.

They don't exactly know how they got here It is easy to explain, but difficult to convince them that such an explanation is a true one.

I wonder how many people realise the number of wrecks there are that are traceable to the coal strike of three years ago? Immediately after that strike I edited a hard-luck page for a weekly newspaper, and at least thirty per cent, of the men who confessed their ruin traced it directly to that strike. Small shopkeepers, like master men, found them.selves one day (figuratively) snug and comfortable; the next day they were waiting in a queue for admission to a Church Army institute or begging admission to the "Morning Post" home.

Now you find plenty of small tradesmen; you find, too, officers and soldiers with a bitter recollection of gratuities ill-spent. Not squandered— just badly spent. They invested their all in business, which they knew nothing whatever about. Poultry farms and garages and things that seem easy.

Chess figures carved from bones, as big as a man's fist, and said to date back to the tenth century, are now on show in the British Museum.

NOTHING gives Bill a bigger laugh than newspaper articles on prison reform. The State started to reform Bill when, as a ragged little pickpocket of 12, they sent him to an institution for youthful delinquents. I don't know how long he was there, but he went in a clumsy, inept little thief, and came out as dexterous an expert as ever picked a pocket or dipped a bag.

Then he became a burglar and a jewel thief (he got his introduction to the right kind of mentors when he was in Pentonville); and later he learnt from a friend in Dartmoor of the good pickings that could be had by a man of smart appearance who hangs around railway stations and picks up momentarily neglected suitcases. Bill has a poor opinion of humanity, and his one grim jest which never fails to tickle me is that when he meets a funeral he takes off his hat and says piously: "Thank Gawd he's going straight!"

Alec is another burglar: a slim, refined man with an amazing vocabulary (he speaks with a very pleasant Scottish accent, and is invariably voluble and earnest). He is an office-breaker.

Joe is known to the police as a ladder larcenist. Of late he has been dignified with a new title—they "call him a cat-burglar. But he is still a ladder larcenist, whose job of work it is to enter bedrooms whilst the family are at dinner, usually by means of a ladder, lock the door, and, clearing off all the available jewellery, make his escape, all within a period of ten minutes. The ladder larcenist who takes more than ten minutes at his job is regarded as a bungler.

I don't know whether Bill has ever engaged in ladder larceny, but he confesses that at the moment he is too fat. We were talking the other day about the possibility of burgling my flat, the difficulty of climbing up into my study, which overlooks a busy street, and the almost impossibility of opening a safe of a well-known make, in which I keep, if, the truth be told, nothing more valuable than the duplicate copies of manuscripts that have gone to America, and have not yet been printed. Bill was amused.

"No man of intelligence would dream of climbing up the front of your house," he said. "All he wants is a key blank"—(I have a patent lock on the front door)—"and I'll show you how he does it."

He produced a key blank from his pocket, which he swore he kept only as a souvenir and not for business, blackened it with a match, inserted it in the lock of my door, turned it gently, and then, withdrawing it, showed me the marks that had been made on the blackened surface.

"I could file that key to fit your door in a quarter of an hour," he said. "All I've got to do is to step into a telephone box, call you up, and if there is no reply—-which shows that the family are out—walk round, try the key, file it, and be inside your flat under half an hour. As to the safe—!"

He said insulting things about the safe, and left me with the impression that a child of three could overcome that obstacle with a corkscrew.

I don't know how many times Bill has been in prison. He has been flogged for bashing a "screw"; he has been birched for various offences; he has been in Dartmoor, in Portland, and Parkhurst, and dislikes them all, but finds nothing in the experience calculated to act as a certain deterrent to the criminally minded. I call him a burglar, but he isn't really a burglar, for he loathes night work and the danger attendant upon breaking into occupied premises. Of late years, he tells me, "fencing" has become a well-organised business. Mr. Fence is sitting in the saloon bar of a handsome establishment at Islington, when there enters, a respectable-looking man known to him. Possibly they drink together. After a while Mr. Fence and Mr., Burglar adjourn outside. Says the burglar: "I'm going to 'do' a fur store in Wardour street. I wish you'd come along, Mr. X, and price it for me."

"Is it dead or alive?" asks the interested "fence," meaning thereby: "Is it a lock-up shop or is it one over which people are living?"

"It is dead," explains the thief; and the next morning the fence drives down to Wardour street strolls into the shop, examines a few of the furs offered for sale, and makes a rapid and fairly accurate estimate of the value of the shop's contents. That afternoon he meets the burglar, or a friend of the burglar's, by appointment; there is a little bargaining, a little haggling, and eventually a sum is agreed upon. The contents of that unfortunate store have been sold before the burglary is committed. The place to which the furs are to be taken is decided upon, and nothing more is left than for the crime to be committed, the furs taken away and stored, for the thief to receive his price.

Similarly, whilst your Rolls-Royce is outside your door, there may be a car thief and his receiver haggling over its price hours before it is "knocked off" and disappears from all human ken, later to find its way to the colonies or to India, the latter being a favourite market for stolen motor-cars. It may be some satisfaction to you to know that the Morris-Cowley, the pride of your house, which vanished mysteriously a year ago, is now the favourite vehicle, of a Babu clerk and his bright-eyed family somewhere around Lahore.

Our burglars arc-considerably more attractive than, say, the American variety.

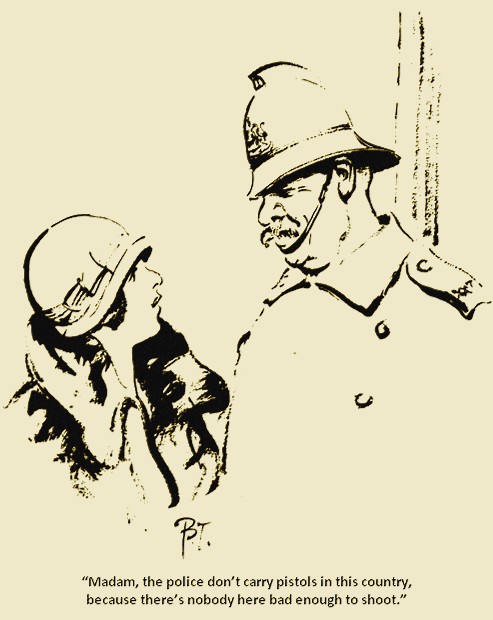

"Have you ever carried a gun, Bill? I asked, and he was genuinely shocked.

"Good God, no!" he said. "What do you want a gun for? If you want to commit murder, go out and commit it. If you want to be a burglar, be a burglar. No policeman is going to be afraid of a gun. You've either got to kill him or he'll get you. Besides, these men are doing their duty. When a lag says, 'I'd sooner be hung than go back to prison,' there's nothing to stop him hanging himself is there?" His own theory is that shootings are prevalent in America because the police carry pistols.

"When you hear of mail vans being held up, or post offices, by people with revolvers, you can bet that the chaps who do the job are amachers."

Individual burglary is not a thriving trade in these days. There are two or three little confederations responsible for most of the more startling robberies, and these, according to Bill, owe their immunity to their perfect organisation. They'll take, a year to plan a real big job, and very likely get one of their own people inside the premises six months before they bust the place. They have tools worth hundreds of pounds, and work to a time-table. Generally they're foreigners, who go around the Continent between busts."

The day of the old burglar, with his dark lantern, his bit of candle, and his simple jemmy, has passed. This is the age of the specialist; and although there may be a sprinkle of old-timers, who are prepared to take the risk of a "bust" with little or no preliminary investigation, they are seldom successful.

"It's just as hard to burgle a country house as it is to get into a bank nowadays," said Bill. "And, anyway, silver doesn't pay for stealing. Most of the big jobs you read about are done at country houses by somebody inside. An old lag gets a job as butler or chauffeur, and waits till he finds something worth taking before he skips. In fact, there are more of this kind of crime nowadays than actual burglaries."

He tells me there is a class of "workman" who specialises in dressmakers' shops, and, curiously enough, not the great establishments, but the smaller, struggling fry.

"It doesn't pay," he said, "but they're satisfied with a few pounds for a night's work, and the job's a pretty easy one if you know anything about the beats, when the police are likely to be around.

"Generally speaking," summarised Bill a little despairingly, "the game's never been so bad as it is to-day. When I was a boy, almost every house had a box hidden somewhere, and you were pretty sure of finding money in it. Tradesmen especially. Nowadays people have banks and cheque books."

A cheque book, by the way, is regarded by most burglars as a valuable acquisition. A man who specialises in the stealing of cheque books told me once that a packet of Bank of England "kites" (cheques) would always fetch £20 from a fence. He sells them to the members of the well-dressed mobs that haunt the West End, and these in turn, make big profits by inducing simple-minded tradesmen to cash big cheques after banking hours. But that is another graft. Bill is emphatic on only one point— that burglary is not what it used to be.

Small boys without tummy pains are not quite natural. Especially in that month of the year when the orchard is a place of greenish apples spuriously rouged. But in November... and when passing under rapid review all that was of his dietary on the previous day without, detecting anything more ache- compelling than Vitamin A...

It isn't right. So you ask for a history of this disagreeable pain that makes a small boy inclined to double up like a jack-knife.

And, of course, he is drawlingly vague. Last year? Oh, yes, but really not bad; a sort of... you know.

Once he remembered, when he was in Caux, just a funny sort of ache that went on and on. I remembered, too sitting on the edge of his bed, the temperature 20 below, and the heat turned off. And I lectured him on the gluttony of small boys, and the horrid things that happened to them when they eat marachino-nougat before going to bed.

But now it is November. "Does that hurt?" If you press a little boy gently to the right of what is euphemistically called his "button," and he winces painfully, you call in your family doctor, and after he has asked a lot of uncomfortable questions and has done his little bit of pressing, he looks at you knowingly and says with diabolical cheerfulness:

"Well, my boy, you know what that is?"

And, of course, you do. And when you've adjourned with him to your study you ask the inevitable question: "Well, whom shall we get?" And he as inevitably replies: "Y-Z."

You knew all the time he was going to say "Y-Z", but you ask just to make him testy. He only gets testy on two subjects—the suggestion that you shouldn't call in "Y-Z" and the unbusinesslike methods of nursing homes.

All this happens if you are a wise lather or husband. If you're unwise you say, a little resentfully: "Can't this thing be cured without an operation?... I must think it over for a week."

If, whilst he is thinking it over the patient dies, he says that the doctor "didn't understand the case," or (this is even more popular) "the doctor should have seen, this coming months ago."

For myself, I said: "Y-Z, of course." And at nine Y-Z's handsome limousine came to a halt before my humble flat. Y-Z is rather young-looking, a leisurely and amusing teller of good stories. Fresh-complexioned, longish-nosed (you cannot be very clever if you have a small nose), something of an athlete, I should imagine. There is the small boy, rather amused, on the bed when Y-Z strolls in, hands in pockets. He is rather engaging, knows boys' talk backwards (which is a little more intelligent and purer than man's talk), strikes a very high note of confidence.

Back he strolls to the study, hands in pockets...

Doesn't seem very bad, but it ought to come out. Going abroad, are you?" He shakes his head at this. "It might be all right—but why sit on a bomb?" I agree. When? The doctor, a foreseeing man, as well as the greatest G.P. in London, has already booked a room. He confirms this by telephone. Y-Z, the surgeon produces his engagement book. It is alarmingly full. "Let him go in to-morrow; we'll do it on the next morning. What about ten o'clock?"

The doctor thinks ten is a good time.

A telephone inquiry. Dr. Z is doing one at ten. The great doctor grows a little choleric (he must sound terrible on the telephone). "Most unbusinesslike... I told you ten o 'clock."

"I'll bet he didn't," says Y-Z sotto voce. "

"...Well, eleven-thirty."

"That will suit me," says Y-Z.

It suits everybody. Even the small boy on the bed who is promised "treatment"—that wicked word "operation" is never used. (Next afternoon, as a treat, he goes to the cinema—both of the films have operations in them!).

Have you ever sat in the: waiting-room of a nursing, home and seen the cars come up? The anaesthetist, in a little runabout, with his little black bag (anaesthetists aren't allowed to have Rolls-Royces), and then the doctor with his little black bag, and then the surgeon with his absurdly small equipment. Have you heard them foregather in the hall and talk about the weather, and that poor old soul who popped off last week?

"She had a long innings," says somebody cheerfully.

And then the wait—eternities until the brisk anaesthetist comes down looking awfully pleased with himself.

Well, that's a relief. He wouldn't be smiling, or discussing outside the petrol-eating propensities of American cars with my chauffeur, if the small boy had died under the anaesthetic. He would be thinking up a good story for the Coroner. (You think things like that when you're in the waiting-room of a nursing home.)

And now the surgeon comes in.

"I had a bit of a shock."

He explains in non-technical language the reason for the shock. If the operation had been delayed a month—a week. He spreads out his hands expressively. He is saying "Good-bye" to the small boy.

Later that same small boy is on view propped up by a bed- rest—terribly white, with dark shadows under his big eyes. He is drowsy, a little sick, has a pain in his side which he cannot understand, is not interested in anything. In three days he will be eating boiled chicken, and between proud references to his lost appendix will be devouring the exciting stories of Mr. Percy Westerman at the rate of two books a day. That little job cost me a hundred guineas—one hundred guineas for the use of those sure, confident hands for a quarter of an hour. It is the cheapest service I know.

Somebody else has the use of those hands to-day. Poor Mrs. Brown who is in the Something Hospital. She is literally a washerwoman, and has never seen a hundred guineas in her life and never will. Somebody gave her a "letter" to the hospital. She also has had queer pains, but the idea of an operation is dreadful. All her neighbours put the corner of their aprons to their mouths in horror at the thought "It's awful... with all them bits o' boys lookin' at you an' practisin' on you, maybe."

The bits of boys will be looking on just as all young surgeons in the making look on, but it will be Y-Z in a white wrapper who will "do it." He will talk rather rapidly as he works—perhaps he will tell stories of great surgeons and what they have done; but he will be just as careful, just as expeditious, just as considerate as he was with the small boy. And if Sir X-0 (whose fee sometimes runs into four figures) is performing the operation he will give the washerwoman just as much intensive thought as he gave the Duchess when she was being treated in her West End nursing home.

It would cost the washerwoman nothing.

The people who pay big money to big surgeons make the least extravagant outlay of their lives. They are doing something for Mrs. Brown, too. That is the excellence of our system. What he did for Mrs. Brown he did also for her boy son in Flanders—maybe he learnt a lot of his trade there. He has a string of letters after his name which suggest military virtue. In queer old barns and chateaux, with shells bursting picturesquely and unpleasantly close...

Modern surgery is the most wonderful phenomenon of the age. I say this having seen some of the old surgery. It is worth just what life is worth' Never be afraid to call in Mr. Y-Z or Sir X-O or Mr. Z-X. That is, if you want to live.

You lose an awful lot of fun in England if you only talk to the people you meet in the club. Their very affluence has stripped them of romance and the glamour of great pasts. I am a teller of stories by profession, but I seldom take stories from real life because they are so improbable that literary critics say: "Well...! Really...!" and a writer who makes a literary critic angry ought to be well slapped.

All the real stories, the big ones, are not contained between covers. Adventures...?

There's a stout and sturdy young joiner who will come to your house and cover your walls with oak panelling that looks really old—worm-holes and knot-holes, and bits of moulding breaking off through extreme age, and all that sort of thing. He rides a motor-bike and was nearly killed a year ago somewhere in Kent, but he is all right now and is going to be married. Maybe he is married.

A stout fellow, terribly tightly dressed, with a reddish, round face and good-looking.

I got tired of talking about wormholes, so I ventured to express views about Stalin. He brightened.

"I was with Denikin's army," he said staggeringly. "It was really awful. The Bolshies retreated on Moscow because they thought Denikin's crowd was led by British officers—they were Russki's really, in British officers' uniform. My feet were frozen and I was taken to the hospital, and then the Bolshies began their advance. We could hear the guns in the hospital. A Russian nurse used to come and sit on my mattress and, drawing her fingers across her pretty neck, used to say: 'Presently Russians come—' they cut your t'roat!' Cheerful, eh? A pal of mine got me out under fire. Laid me on a sledge and ran for it. What was my job? I don't know what I didn't do! Machine-gun instructor—everything!".

Here was Denikin's army in London, N.W.! You would never know that unless you took the trouble to find out.

A rather dour, middle-aged taxi driver brought me home one evening. In front of where he pulled up was a big American car. He looked at it critically and wondered if the back axle was O.K. in the new model.

"Know it?" I asked. He nodded.

"Last time I drove one was over the Khyber Pass," he said. "They're wonderful on hills."

The chauffeur who was standing by the car had views. His driving was in Serbia. He was awarded a gold medal, but never got it.

Khyber Pass and Monastir compared notes. They said horrible things about certain makes of cars. I sat on the running board and listened, I think my neighbours thought I was the worse for drink.

There are two racing reporters—you can meet them at any meeting. One of these took convoys to the edge of the Afghan country, and knows quite a lot about the playful ways of hill rivers. The second man had an easier job. All he had to do was to teach young flying corps officers to jump out of balloons. He knows almost as much about parachutes as he does about Galopin' Blood. But these two are not really eligible for my category of commonplace people. Journalists are very uncommon people—especially racing journalists. My experience of life is that the best stories are those of the most (apparently) commonplace folk, and the worst are those of men whose lives you would imagine were packed with thrills. I once interviewed a hangman, and all that he said was: "Well, sir... it was like this..."

He never really got interesting until he started to talk about chickens and advanced this brand-new theory about biology: That hens lay eggs and produce all cockerels if you put the nest under a green light. And that was a lie. Probably hens do that sort of thing for hangmen, but they don't do it for humble reporters.

You could not walk through Covent Garden Market any morning without rubbing shoulders with incredible adventure. It comes to your door, if you can see.

One night rather late there arrived at my flat a gentleman who talked with an accent—well as the good people of Walworth road speak. He was selling tickets for a concert on behalf of broken-down horse cabmen. His voice was loud and hearty. He was, he confessed with pride, of the people. And he was educated—at where do you think? I won't tell you the school but it has as proud a name as any in England; a great public school that has sent out splendid generals and statesmen.

I didn't believe him till he began rattling out from memory long passages of Virgil. My Latin is negligible, but I knew enough to be staggered.

"That's the kind of muck I had to learn," he complained bitterly. By the way, he is pretty well known in South London, but I know he will not object to my telling the story—he oven invited me to "put it in a book."

His father, a self-made and uneducated man, amassed a fortune—I think he owned buses. When the father died intestate the fortune was thrown into Chancery. An unimaginative master decided that our hero and his brother should be educated. He only knew one school—the boys were sent there.

"I hated it," said my friend. "Latin an' Greek an' God knows what! As soon as I came out and got hold of a bit of money I bought a pub in the ________ road!"

Would you say that was possible? It is not only possible, but it is a fact. A thoroughly honest, decent fellow, is this public school boy. But he hated the life —loathed his companions. Can't you see him sitting at prep., his mind hovering about "The Red Cow" of his dreams?

There are some amazing people in London. Down Pimlico way a lady was pointed out to me. She lived in a shabby lodging, and, attired in carpet slippers and an old cap pinned to her brassy hair, she was carrying a beer jug to a nearby public house. To get, she said pleasantly, her morning ration. I happen to know that she made history—changed the succession of a great reigning house of Europe. It seems absurd, but it is a fact. The story cannot be told, but it is common property in Press circles.

The truth is that in this country (and possibly in no other country) there are no commonplace people except to the superficial observer. If you can't see behind the eyes or get into the minds of folk and accept just what they present to you, features, figures, and manners, the world must be a dull place. And you miss a lot of drama. And some splendid pathos.

There is a man working for me—an Irishman. A big, good-looking Handy Andy, and a splendid car driver and mechanic. It was his ambition to ride at Brooklands on a racer, and at last his chance came. A well-known driver was taking him in a race as a mechanic. On the morning of the race: — "I'm sorry, F—, I've just learnt that you are an Irishman."

"Yes, sir."

"I can't take you. My brother was murdered in Ireland by Sinn Feiners, and I've sworn never to employ an Irishman."

"Very good, sir," said F— quietly. He did not tell the car racer that his own father, an inspector of the R.I.C., had been shot down in cold blood in the streets of his native town.

A pretty little house on the Bury road, every wall or every room covered with paintings—there is a Greuze in my bedroom, and I sleep on a noble bed designed for Royalty.

Raphael looks down upon me in the dining-room as I eat real Yorkshire pudding—the host comes from that county. And Yorkshire pudding served as a course and eaten solemnly—and what Yorkshire pudding! Not the custardy stuff that London cooks prepare; not the thin slither of yellow pastry that cracks down on your plate at the fashionable restaurant. But Yorkshire pudding.

The host is a burly gentleman; the other guest is a dapper, shrewd man from France.

"I saw that horse this morning—you' shouldn't let him run loose... I never saw a horse more improved, and if he has any luck they can't keep him out of the first three."

He was talking of Asterus, who occupied that position in the Cambridgeshire. It was rather a depressing week for host, for the betting tax was due next Monday, and he was a professional backer of horses.

A gambler? Not exactly—in the Monte Carlo sense.

You see, racing, from the professional backer's point of view, is a business. You can reduce a field of thirty-seven runners to four or five, and can say nearly with certainty: "One of these five will win." You cannot sit at a table at Monte Carlo and be assured that, of the thirty-seven numbers, one of five will turn up. That is the difference between racing and gambling. If you take black and red and gamble on one or the other, there is nothing to prevent red and black coming up alternately; but if you match Coronach against a selling plater in twenty races, it is definitely certain, bar accidents, that Coronach will win every time.

You can make mistakes, of course.

Arthur (as I-will call him) climbed up to the stand as the horses were at the post.

"Have you made a bet?"

He nodded.

"I've got twenty-eight hundred pounds on Adam's Apple," he said, "and, having seen him go to the post, I think I've lost my money."

Something had happened to Adam's Apple. He was beaten, and well beaten, and returned to the paddock with peculiar symptoms, to which the attention of the stewards was drawn.

Arthur knew he was beaten before the field came to the dip.

"I've lost," he said in a conversational tone, and asked me whether I had slept well on the previous night. There was no emotion, no hectic reviling of horse and jockey. He had lost—that was all. If he had won, he would still have asked me if I had slept well. He won a thousand on the last race, and finished the day losing £1300.

"I have turned over as much as two millions in a year—my winnings on balance were not very considerable. If I had paid a tax of 2 per cent. I should have lost £20,000 on the year!"

He goes to the South of France regularly, but the tables never see him. One of his friends complained that he had lost £5000 in six weeks. "You haven't," said Arthur promptly. Indignantly the friend produces his pass- book.

"Still you haven't lost," said Arthur, and proved it.

The man had been playing regularly, and from every coup the Casino had extracted its little tax. The friend sat down and worked out roughly how much the Casino authorities had taken—£8000. "You've won three thousand—congratulations! " said Arthur sardonically.

That 2 per cent, tax has made betting impossible for him, and he argues that racing will be made impossible for the masses. The "same principles apply whether a man bets in shillings or thousands.

"Kitty" is draining steadily. With every twenty-five bets the stake is absorbed to the State. Politically, the result will be interesting to see. For some reason racing folk are conservative in politics—even the smaller fry are Tories. My own view (which is entirely dispassionate) is that the Bets Tax will produce an enormous turnover of votes, and that it will be remembered against the party when the coal strike is forgotten.

But that we shall see. It is certain that every bookmaker will be a nucleus of anti-Government propaganda, and that the rough machinery exists to spread that propaganda. This factor is not to be despised. A test canvass would, I think, produce results that would stagger the party managers. As to Arthur, he can afford to wait and "look on," but he is more favourably situated than some of the other "pros."

"Quite a lot of people will go out of ownership in a year or so. Two thirds of owners can only afford to keep up a stable if they can bet—you can't keep horses on the money you win through stakes. If the tax continues, we may not feel the effect for three years."

The professional backer lives a strenuous live. He is up in the morning (if he lives at Newmarket), watching the horses at exercise. He has to understand horses, and mostly he must be able to distinguish in the course of a race just what every animal is doing. His judgment is perfect. He will tell you two furlongs from home what horse will win, and when they finish by the post in a close finish he seldom is in error when he names the winner, however bad the angle may be.

There was a race at Newmarket when three horses, widely separated seemed to have passed the judge in a line. He knew that I had backed one, which in my judgment was third. "Yours has won for a fiver!" he said, but I didn't bet. I knew that he must be right. And I was wise in my generation, for the horse I had backed had won by a head.

Arthur seldom bets on handicaps—it must be a weight-for-age race or nothing.

What does a man like that do with the money he wins? He took me in his car to a place beyond Dullingham, and introduced, me to his new stud farm. They were ploughing the far field, and bricklayers were already at work laying the first courses !of his new boxes. This untidy field was to hold three paddocks—that stretch of grass land was for the yearlings. His sire, the pride of his eyes, was coming here, and he was very confident about the future. "I put all my money back into racing side of racing. I have just sold my old stud farm—l think this is a better one." I spoke well of his stallion, one of the grandest looking horses i have ever seen at stud. "This is where the gambling comes in," he said. "That horse should have won the Stakes at Goodwood, but was left at the post. He could have won pulling up, and his fee at stud would have been somewhere in the region of ~8 guineas. As it is, I am giving subscriptions for nine guineas—it is the only way I can 'prove' him. He'll sire great horses, that is certain. Look at his legs! The hardest thing to breed out of a horse is bad legs, and yet breeders send their valuable mares quite gaily to broken-down animals and pay 198 guineas for the privilege." I watched the big tractors steaming away on the far field,and turning the dirty green into rich black earth, and seemed to be very far away from the precarious game. And yet it is all part of.it. All round were cottages occupied by families that lived on horse-racing, though they themselves may never have seen the colours on a horse. The ploughman and the tractor men, the hedgers, and bricklayers.

A smart-looking man in gaiters came across the soon-to-be paddocks. "I've just been looking at that mare's pedigree, Mr. A—. She's got two close crosses to Galopin'..."

The stud groom brings you nearer to the track. Yet he is not passionately interested in the actualities of racing.

Driving back, Arthur indicated the points of interest in the landscape. "Captain Cuttle stands over there, and..." He named in rapid succession a dozen famous names. Newmarket again. The main street blocked with hackney carriages and char-a-bancs, and the pavements thronged with newspaper sellers and purveyors of race cards; all the world flocking up to the Heath, and the air vibrating with tips. And a little later: "I'll take you six hundred to four twice!" The tapes are up, and the huge field is on its way home. Thousands of race-glasses are levelled on the silken jackets. And then, as the field comes down Bushes Hill, a bookmaker airs his opinion. "I'll lay five hundred to two, Sea Girt!"

"Take you!" One of Arthur's kind backs his judgment, and wins.

Going home that evening: "There's a mare coming up at the December sales that ought to be bought—she hasn't foaled a winner, but I'm confident that she will. A friend of mine bought a mare, kept her for years and she never gave him a foal worth racing. The year he sold her she had a colt that won £12,000 in stakes..." A precarious game.

Parsons..." One does not know very much about them. Some of them have nice houses in beautiful little country towns. Some go trudging through the slush and fog of London. All seem desperately short of money. One is awfully careful about what one says in their presence, and they marry you and all that sort of thing.

An ill-paid profession, sometimes an annoying profession, for do they not occasionally refuse to bury Dissenters or even refuse burial at all in consecrated ground? And do they not some times figure in scandalous columns of Sunday news—an appropriate day for the exposition, of their weaknesses? Whereupon do we not raise our voices and say:

"Ah! These parsons...!"

Down Tidal Basin way on a rainy night last week they came and knocked up a parson. His parents live rather nobly in a Yorkshire mansion, and have cars and things. He lives meanly in a very small house, a thin, rather plain young man (he admits this joyfully), and be has to keep body to soul on a dietary a little better than you can get in a workhouse, but not so good as they serve at Dartmoor. He got out of his bed and went out into the night, and eventually was guided to a hovel where a man lay with the sweat of death upon his face and a great unrest in his heart. And he was there, in that frowsy room, until daylight came uncleanly through the panes, and the man went to his appointed end.

He had to go back to his little church for Matins. Nobody else was in the church—few people came at that hour. At 11 o'clock he had to meet church officials about the heating of the little mission hall. He lunched expensively with Lady Somebody. He was rather bored, and would gladly have taken the value of it instead, but she was helping to raise some money for one of his funds. People who saw him lunching probably said:

"These parsons! They do themselves jolly well."

He had some old women to see in the afternoon; lonely old women who were not picturesquely starving, but were dying of dullness. They have enough to live on, but nobody speaks to them. They just sit and look out of the window at the backyard, or put a little coal on the fire, or make themselves a cup of tea. They are the living dead. The noisy tide of life sweeps past them but none of the noises is directed towards the sad old women and men who hobble from bed to fireplace, and from fireplace to window.

"Bore me?" he chuckled. "Of course they bore me! They would have plenty of visitors if they were amusing. But it is worth being bored to see them brighten up at the sound of a human voice. They like their religion in its most formal shape—some of them shy when I tell them I am an Anglo-Catholic—they want to know what I think of the Pope! Poor, drab creatures—but you can find lots of flowers and beauty in their lives."

Were they churchgoers? Frankly, he wasn't sure.

"But what we're building on is the knowledge that the Church of Christ is not a friendly society which has no benefits except for its members. People come to me at all hours to ask me if I would visit their dying relatives. And I go. I've never seen them before nor heard of them. I have the shining example of the Jewish rabbi who, on the field of battle, gave absolution to a dying Catholic. A stout fellow, that—and inspired."

Curiously enough, the old cadging class that hung like parasites to the robes of the Church have dropped off. The blanket and coat brigade that attended two services on Sunday, and had its material reward at intervals, seems to have shrunk to platoon size since the war.

"The terrible thing about dying people is the anxiety of their friends to 'humour' them.

A great West End surgeon had told me the same thing in almost identical language a few days before. He said the most pathetic spectacle in the world is a dying man or woman who really wants something done which nobody will do.

"Get me the documents that you'll find in the top right-hand drawer of my desk!"

The well-meaning wife or husband tries to soothe the sufferer.

"That will be all right—don't worry everything will be all right."

The poor, exhausted creature has no strength to insist. Sometimes it is a bundle of letters to read which will add bitterness to a widow's sorrow. Once it was a book of dubious character.

Nobody takes dying people seriously—which is dreadful.

My Ritz-lunching parson has many callers at his little house. Girls in trouble—women whose furniture has been distrained—men who would like him to break bad news that they have not the courage to break...

His church is not crowded on Sunday. Nor do his parishioners call him blessed as he passes by. They greet him with embarrassed grins; most of them think that he makes a fine living out of parsoning.

"Otherwise," they argue, "why should he?"

They have for him the same respect as they offer to the fire brigade; that is in many ways a perfect parallel.

The Church has grown curiously since the war. Such trace of its development as may be found in statistics gives no real understanding of what has taken place. Men came back from France immensely advanced in their views of eternity. Death was a palpable fact; ordinarily a man might go through the best part of his life and never see the ludicrous thing that once held a soul. War changed that for millions. The phenomenon was a daily experience. It was the living which became curiosities. And what after? Here's a man in a white surplice who one thing; here's a man in a biretta who says different. Some men found temporary comfort and courage in one set of observances, some in another. I imagine that in the vast majority of cases the final settlement of this soul business was postponed with the contingency that, if the Reaper came m the meantime, they had effected a sort of short-term spiritual assurance.

Certainly the god of war has a countenance more terrible than the god of peace.

They came back in their millions, not to mope or mourn or pray, but to find relaxation and forgetfulness of the mad years that had gone. And such as retained any curiosity on the object learnt on inquiry that the civilian God was something of a stranger. It is absurd of course, but the God who is beseeched to bring rain for farmers bears no resemblance to the terrific God to whom hearts go out in an agony of supplication when red death is leering at your elbow.

"People had to scrap their old conceptions and begin building again. And the Church is the gainer. I especially believe that the Anglo-Catholic Church has gained most."

There is a stout evangelical section which is for "broadcasting" the Church, making wider the gap between the old Church and the new. They believe that Christian religion should be stripped of its fal-de-rals and its esotericism. Where the stripping shall stop, nobody knows.

The passion for simplicity of service and observance would be understandable if the Christian religion were of itself entirely free from mysteries. But it isn't. If it is, then there is no religion. When your scientist and your philosopher have found a purely logical explanation for such phenomena as the Resurrection and Prayer, when even faith is reduced to a pathological term—when all the mysteries are mysteries no longer, what remains? You may go on informalising until there is nothing left. And the strange thing to me is that, even as the Socialist sneers at evening dress, yet wears a red tie, so those who are all for removing crosses from churches are sticklers for the formal. They must have pews of a certain shape and discomfort— they even close their eyes when they pray! Why? There is nothing more reprehensible in a genuflexion than in kneeling to pray. One act of adoration cannot be wrong and another right because different sets of muscles are employed in the process.

"Prayer book revision?" My friend the priest shook his head. "I really don't know what will happen. They will leave me my altar..."

He needs his altar very badly; In the early morning you will find him kneeling there as the church bell clangs unmusically. Always providing that he has not been called somewhere.

"Doctor says mother can't live another hour, and father says would you come along an' say a piece?"

"To the old village church

They marched our young he'ro,

'Aim straight at me 'art!'

Was the last words he said,

Exposin' his breast

To the points of their ri-fills.

The smoke cleared away—

Our young he'ro lay dead!

"GOOD GOD!" said I, shocked. "Haven't they forgotten that song?"

"They don't forget nothing in the Army," said Ernest with pride.

Here was I in a canteen—a sort of idealised canteen—and here was Private Somebody-or-other singing the song that brought tears to my youthful eyes way back in '94. Nothing has changed. The Army forgets nothing.

Do you ever realise that there are no printed rules for hopscotch or rounders or tipcat, and no treatise on the art of spinning tops? The mystery of these noble practices is handed down from generation to generation by word of mouth. And nobody has ever laid down the rule that the favourite songs of the Army should be Irish revolutionary songs, and yet they have been for so long as I can remember. I suppose there is a certain plaintiveness about Irish songs which appeals to the sentimental soldier—for soldiers are still sentimental.

No change. More money, a little more work, better feeding (in dining- halls instead of the barrack-rooms), but otherwise just the same, old Army—the Army of '14 and the Army of Wellington and Marlborough. Who told the soldier that Ypres was to be pronounced "Wipers"? The British Army has always called : Ypres "Wipers." Marlborough's soldiers did. I saw a letter the other day from one of Marlborough's officers. "The men speak cf the town as Wypirs," he wrote. In one respect, however, there has been a change for the worse. An old dummer with umpteen years' service says that beer is not what it was.

But then they used to say the same thing when I was a soldier. There was an old Crimean veteran, Callaghan, of the Rifle Brigade, who could and did speak for hours on the subject of Brews. He was a teetotaller when I met him, having been driven to this distressing decision by the falling off in the quality of Army beer.

The older men, the '14 veterans, will tell you, shaking their heads, that the Army isn't what it was. But then, the Army has never been what it was. In 1893 I was told by an ancient barrack warden that when he was soldiering—it was soldiering.

"The present generation" (I can hear his quavering voice now) "is midgets compared with the men who was soldiering when I was a recruit."

And so on ad infinitum —down the ages will go that head-wagging. "In my time soldiering was soldiering!"

A second-in-command major challenged the "no change" theory.

"There is one difference—we don't get half as many 'drunks' as we did. In your time you'd probably have three drunks in the 'clink' every night—we very rarely get them. I think the standard is higher than it was before the war—physique and character. Certainly the Army of to-day as more technically perfect; the drill and training approximate nearer to the realities of war. We are building up a magnificent force."

The Army really doesn't change, because it is recruited from an unchanging class—youthful working-class people. Men of better education, the kind that with luck and application have got a job pupil-teaching or bank clerking, can make good in the Army only if they are good mixers. Tommy still resents swank.

Of one who gave himself airs because he imagined he was superior to his fellows, Ernest said:—

"He struck pa with a roll of music and run away for a soldier!"

I was awe-stricken. "Do they still say that?" I asked in a hushed voice.

The Army doesn't change. As, for instance:

"The worst thing about soldierin' is that people look down on you. When there's a—"

"—war on," I finished, "they make a fuss of you, but now the war's over they treat you like dirt, and won't let their daughters go strolling with you down dark and draughty lanes."

"You heard about it?" said Ernest, interested.

"Thirty-three years ago," I told him.

Private soldiers are very human and are pleasant to talk to; warrant officers terrify me because they have grievances which revolve in some mysterious fashion around the Royal Warrant for Pay and Promotion. And a warrant officer with a grievance is more fearful than measles...

Here is the old square again, gravelled and uneven. And the old red barracks with their shining windows, and the faint blare of a bugle summoning orderly sergeants, and the little knot of left-footed recruits being initiated into certain mysteries.

Gosh! How lovely and young it makes you feel to see three youthful military gentlemen pushing a hand-cart full of coal, under the eyes of a self-conscious lance-corporal, and to hear one wind-blown fragment of speech as they pass.

"There ought to be a so-and-so coal mine outside every so-and-so married quarters!"

In my days love and light refreshment were the curses of the Army. To- day, even as the guard-rooms have fewer occupants, so have the hospitals—in certain respects. We are much more intelligent about things to-day—broader, more humane, and we teach soldiers things that would never have been possible in the prudish 'nineties. Aldershot, as everybody knows, is the hub of the military universe (though Catterick is making a little hub of its own), and in or about Aldershot are all the mysteries and wonders which science has evolved for the destruction of possible enemies. The new soldier by rights should be a slim wan with a bulbous forehead, a little short-sighted and mathematically minded. He should approximate to those supermen whom it is the joy of Mr. Wells to describe when he is not engaged in particularising the nasty amours of self-made men.

Think of all the material progress we have seen since the days of the Martini-Henry! The tanks and gas masks, the armour-plated aeroplanes and wireless, and the Lord knows what. But the spirit of progress has not touched the poor so-and-so infantry; they are just whore they were in the days of William the Conqueror.

Ernest (who is something of a find) wrinkles his nose sneeringly at science.

"I've heard all the muck about the next war—repeatin' rifles an' what-not. And gas and sick-smoke and aeroplanes that can wipe out Aldershot in three ticks. Death-rays—you ain't mentioned them! But when the war comes, what'll it be? A fatig' just the same as the last one! Workin' parties an' whizz-bangs, snipers, and cetera. 'Over the top and good luck, old boy!' I know!

"They'll sit down an' work it out on paper—so many places to be

wiped out with aeroplanes, so many miles of trenches to be took by tanks, and

so on and so forth. An' when the places ain't wiped out and the trenches

ain't took, they'll say, 'Shove in the Fif' Division, an' see what they can

do.'

"Moppin' up is war—not tanks an' aeroplanes—it's fillin' up the gaps that counts. I'm not sayin' anything against science, but I'll believe in it when the War Office takes away the soldiers' bayonets and scraps the bombin' school."

In almost exactly these words did Ernest recapitulate his faith in the indispensable infantry.

"That is about the silliest book I have ever read," said Diana.

I took the slim volume from her hand and read it. And as I read, my hair stood up. It was the nastiest little book that has ever come my way, being the confession of a peculiarly unpleasant young lady who had the habit of going into the woods and taking off her clothes. And, of course, it was most "literary," all high-falutin', and on the loftiest plane. It has to be that, or the queer folk who like that kind of stuff would have no excuse for reading it.

"But it is so well written," they plead.

I put the book down.

"What do you think of this kind of muck?"

"I think it is silly," said Diana, "and it is not terribly well written. Anyway, who would do that sort of thing?"

That was all. Nothing about the blatant indecency of it—its syrupy impurities. Diana is not so terribly modern that she stands out from her girl friends. They have all read the little book.

("Please return it directly to the librarian," says the lady at the library, a little shocked.)

There are stern fathers who, having seen that kind of literature in their daughter's hands, would grow tremendous and awful. They would talk about what their dear mothers would say if they were alive, and the effect on their dear grandmothers. But that is rather stupid.

There was an age when girls were not supposed to have legs—only trim little ankles, and those only occasionally, when big masculine D-s produced faintness in gently-nurtured females. An age of artificiality that tolerated the nude in Renaissance art, but rather suggested that things had improved since then.

This is an age of reality; emphatically more wholesome. Gone are the days of nasty ancient mysteries which were not mysteries at all, though everybody pretended they were. Truth is a great killer of diseased imaginations. There is an idea amongst quite nice people that the modern girl drinks too much, smokes too much, keeps abominable hours, and is rather heartless.

"Which means,",said Diana, in relation to the last stricture; "that she isn't as sentimental as she was. I don't think we are—in fact, I'm sure. Naturally, I can't remember pre-war men, but I am certain that they weren't as sentimental as the young men of to-day. They slop! I know it's an ugly word, but they just slop. Women are being driven to heartlessness in self-defence."

Later Diana was very frank on a matter which her mother would never have discussed with her father.

"That's silly, too," she said when (very mildly) I pointed this out. "If a motor engine were human, I am sure it would never blush when it discussed its carburettor. I think the other generations of women must have had an awful time—they were never allowed to have anything but headaches. That is why they never had their appendices out—they weren't supposed to have 'em! It was ladylike to die gracefully surrounded by your weeping relatives, but only the doctor and the intimate friends of your family were allowed to know that it was something to do with the tummy.

"And the mysteries! Whispered in dark corners like a tribal secret—The Thing Unknown To Man! And think of the girls who went to their marriage with the idea that the doctor brought the baby in a big black bag——"

"Stuff," said I.

"Stuff," echoed Diana. "I know a girl who was brought up nicely. Her mother told her nothing—froze her to death when she asked. You know the sort of thing—'My dear, that is not the sort of thing one wishes to talk about.' A sort of inverted vanity."

Now the modern girl knows. Is she worse or better for the knowledge? If she is worse, then society is in a rotten state, for these secret matters are discussed very frankly.

And of course she is better. Prurience succumbs to the germicidal qualities of Stark Truth. You discover that if you are acquainted with any of the big girls' schools in the country. Behind the slang phrases employed to describe the indescribables of life is sheer sanity—which is Truth. It is good form to be flippant on subjects that would make the overworked and over-libelled grandmother turn in her grave; it is bad form to make such matters a subject of conversation.

I was in a night club (so called) last Wednesday, and had a good look round for the cocktail-drinking. and modern young lady who is supposed to haunt these establishments. There were about two or three known to me, and they were drinking something innocuous. They had come in after a theatre, and were gone before 1 o'clock.

"The average nice girl hasn't a look in at these places," said Diana, relentlessly. "You could comb all the night clubs in London any night and never find more than two dozen, and they would be with their parents or uncles or things. Young men haven't any money. Most of the women you see at the club are middle-aged, and if they're young and pretty and are always dancing with the same partner whenever you meet them, they are 'What'll I Do's.'"

"What is a 'What'll I Do'?" I asked.

"Don't you know that brand of song?" asked Diana. "'The Broken Doll' and 'What'll I Do' and 'You Made Me Love You'? They're all about girls who have lost their well-off dancing partners—poor dears!"

There is an idea abroad that her growth to athletic excellence marks the complete emancipation of the modern girl.

"That's silly—girls have always played tennis and hockey as long as I can remember. Golf isn't novel, either. People get foolish ideas about women's athleticism from seeing freakish ladies boxing and running. Everything that, has 'come over' girls in the past twenty years is to the good. Short skirts and open necks, shingles too. If men like long hair let 'em grow it! Let it be their crowning glory. Women have never been so sensibly dressed as they are today—they are leading the dressmakers, for a change. In the old days a Paris dressmaker could ordain just what we had to wear. They've tried to get back their old supremacy and failed. Time and time again they have tried to bring the hem of the dress to the ground, and they haven't. Women have found their legs—literally!"

The modern youth, whilst he grows properly indignant at the suggestion that he is a "slop," is quite satisfied with the modern girl. A blasé bachelor told me!

"A boy can always tell her that he is broke, and it's nice in other ways. Girls are better pals than they ever were. They're easy to get on with, and you don't have to pretend. We've lost a lot of the pretty-pretty stuff that is so popular on the Continent—the bowings and scrapings and hand- kissing, but that stately business never meant anything. I congratulate myself that I had the sense to wait for this generation to come along."

* * * * *

There she goes—just ahead, of me!

"At the wheel of somebody's car, her shingled hair blown all ways, the end of a golf bag sticking up out of the dickey. Beside her crouches a bare-headed boy in a University who winces every time she changes gear. Presently she turns abruptly to take a side turning. She doesn't put out her hand until she turns the wheel... Fortunately I have fierce brakes on my car. The modern girl is a rotten driver.

The musher got his cab on the never-never system. He paid so much down and pays, so much for years and years. Too much for too long. The cab, looking at it with an honest eye, is worth something under £400—he has to pay nearly £900. Some men have paid more. It is a form of licensed brigandage which has been going on for years.

Saddled with this horrible liability, the "musher" (by which name the small owner-driver of taxi-cabs is known) took to himself a working partner.

Nobody asks the cab whether it likes the work day and night—it just does. Every morning and evening it is cleaned and the engine gets a bit of a rest.

It is a hard sort of life; the reward is poor; it is often a struggle to keep a family and pay the installments. There are one or two cab builders who have played the game with the men. Most of these have only made their presence felt recently.

I have owned some beautiful cars in my time-I've never had one that cost as much as the taxi which would have brought me home to-night but for an unfortunate journey to Belsize Park; just think of it—for another few hundred pounds you could buy a 1925 car, second-hand, but of the best make and in fine condition!

"They talk! about taxi-men expecting tips—they couldn't live, without 'em! I've been out since 3 o'clock this afternoon, and I've not taken enough to pay for the juice I've used! I hand it over to my mate at 10 o'clock. He takes the theatre and supper trade—as much as he can get of it. The theatre trade's a gamble, especially on wet nights. You don't get regular riders but three or four.people who use us instead of a bus.

"I was on the rank for three hours the other, night, and when it came to my turn to; pick, up, I got an old gentleman who wanted to go from Haymarket to Pall-Mall. One shilling—no tip. Three hours' waiting, and me, dreaming of taking home a young swell and his lady-friend and going to Hampstead by the longest way—three times round the Outer Circle and up Avenue road."