RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

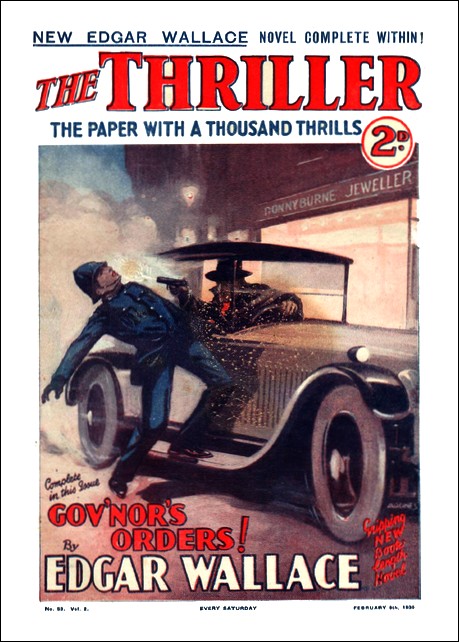

"The Guvn'or/Mr. Reeder Returns" — first UK and US editions

THE affair of Mary Keen was never forgotten by Robert Karl Kressholm. He was a good hater, as Mr. J.G. Reeder was to say of him one day.

Yet it was an odd circumstance that Mary, dead and buried in Westbury Churchyard, should remain as a raw place in the mind of a man who was, to all appearance and certainly by protestation, madly in love with a child— she was little more—who was twenty years his junior. But Bob Kressholm was like that. He was vain, had complete and absolute confidence in his own excellences. He might congratulate himself that he was young at thirty-seven and looked younger; that he was good-looking in an instantly impressing way and looked little older than at eighteen, when Mary had chosen Red Joe Brady in preference to himself.

Mary was dead of a broken heart—she passed three days after Joe had been released from a short-term sentence in Dartmoor. If Bob could have found her he would have offered consolation of sorts, but Joe had very carefully hidden her and his boy.

Kressholm never went to prison. He was too clever for that. Banks and jewellers' stores might become impoverished in a night, but "the Guv'nor" could not be associated with the happening. He was, he believed with reason, the greatest organiser in what is picturesquely described as "The Underworld." Nobody had ever brought a mind like his to the business of burglary. He had his own office and plant in Antwerp for the reconstruction of stolen goods. In Vienna a respectable broker handled such bonds and negotiable stock as came his way. He could boast to such intimates as Red Joe that he was "squawk-proof" and was justified in the claim. He came down to Exeter, where Haddin's Amusement Park was operating, partly to see and partly to dazzle Joe out of his dull but respectable mode of living. A big Rolls limousine was an advertisement of his own prosperity.

He did not see the balloon ascent, but the parachute dropped square in the road before his car, and the chauffeur had just time to pull up on the very edge of a tangled mass of cord, silk envelope and laughing girlhood.

"Where the devil did you come from?"

"Out of the everywhere," she mocked him.

She wore a boy's trousers, a blue silk shirt and a beret—an unusual head-dress in those days—and she' was lovely: golden-haired, fair-skinned and supple.

This was Wenna, daughter of Lew Haddin.

He drove her to the fair and delivered her to her father. Having come for the day, he stayed for the week; Red Joe had a bed put for him in his own caravan. Joe had a second van—a motor caravan, but this was not in the fair-ground. It was garaged in the town. His guest heard about this and drew his own conclusions—at the moment he was not interested in Red Joe's dangerous hobby.

And every day he grew more and more fascinated by the girl. He brought flowers to her, which she accepted, a jewelled bracelet, which she refused. Fat Lew Haddin offered lame apologies, for he was a good-natured man who gave things away rather readily and would have married off his daughter to almost anybody rather than worry.

Red Joe added to his unpopularity and stirred up all the smouldering embers of hatred by speaking very plainly to his guest.

"She's only a kid, Bob, and what have you and I to give any woman? The certainty of getting her a pass on visiting day and the privilege of writing her a letter once a month."

Kressholm answered coldly:

"Personally I've never been in stir, and I don't know what the regulations are about wives visiting husbands, and that sort of thing. Are you after her?"

"She's about the same age as my boy," said Joe wrathfully.

"Oh, you want her for the family, eh? You think you've got a call on all the women in the world. You're getting bourgeois, Red, since you've become a monkey dealer."

Red Joe wasn't quite sure what "bourgeois" meant, but he guessed it was applied offensively. Bob lived mostly in Paris and spoke two or three languages rather well. He was more than a little proud of his education, which was the basis of his superiority complex. Wenna, who had been a woman at twelve, had no doubts about Mr. Kressholm.

"What am I to do with this feller, Joe? The old man is no protection for an innocent maiden; he wanted me to go riding with his lordship yesterday, and saw nothing wrong in the idea that I should go up to London for a week and stay with Kressholm's friends. Fathers are not what they used to be."

Joe did not want to quarrel with his former associate; there were very special reasons why he should not. But before he could discuss the matter with Bob Kressholm, the girl had settled the affair.

There were two slaves of hers in the circus—Swedish gymnasts, who would have strangled Bob Kressholm and sat up all night to bury him, but she did not ask for outside help.

It happened in a little wood near the grounds on the last evening of the fair. She gave nobody the details of the encounter, not even Red Joe. All he knew was that Kressholm had left Exeter very hurriedly just as soon as the knife wound on his shoulder was dressed and cauterised by a local surgeon.

Wenna had learned quite a lot about knife play from one of her Swedish gymnasts, who had left his country as a result of his dexterity in this direction.

Thereafter Bob Kressholm had another grievance to nourish. A few months after he returned to Paris he learned that Mr. J.G. Reeder was interesting himself in a new issue of "slush" which, in the argot of the initiated, means forged money. And then he remembered the locked motor caravan which was Joe Brady's, but which he never slept in, or even brought to the fair ground. He returned to London on the very day Mr. Reeder had reached a certain conclusion.

"BRADY'S work," said J.G. Reeder.

He had fixed the bank-note against a lighted glass-screen and was examining it through a magnifying glass.

It was the fourteenth five-pound note he had inspected that week. Mr. Reeder knew all that there was to be known about forged bank-notes; he was the greatest authority in the world on the subject of forgery, and could, as a rule, detect a "wrong 'un" by feeling a corner of it. But these notes, which had been put into circulation in the year 1921, were not ordinary notes. They were so extraordinary that it required a microscopic examination to discover their spurious nature. He looked gloomily at the chief inspector (it was Ben Peary in those days) and sighed.

"Mr. Joseph Brady," he repeated; "but Mr. Joseph Brady is now an honest man. He is following a—um—peaceable and—er— picturesque profession."

"What profession?" asked Peary.

"Circus," replied Reeder soberly. "He was born in a circus—he has returned to his—um—interesting and precarious element."

When Red Joe Brady had finished a comparatively light sentence for forgery, he had announced his intention of going straight. It is a laudable but not unusual decision that has been made by many men on their release from prison. He told the governor of the gaol and the chief warder, and, of course, the chaplain (who hoped much, but was confident of little) that he had had enough of the crooked game and that henceforth...

He told Mr. Reeder this, taking a special journey to Brockley for the purpose.

Mr. Reeder expressed his praise at such an admirable resolution, but did not believe him.

It was pretty well known that Joe had money—stacks of it, said his envious competitors—for he was a careful man. He was not the kind that squandered his illicit gains and he had made big money. For example; what happened to the hundred thousand pounds bank robbery which was never satisfactorily explained: Kressholm had his cut, of course, but it was only a quarter. Bob used to brood on this; it was his illusion that there wasn't a cleverer man at the game than he. Anyway, the red-haired athlete, who had once been billed as Rufus Baldini, the Master of the High Trapeze, and was known in the police circles as Red Joe, had a very considerable nest-egg, maintained his boy at a first-class boarding school and, generally speaking, was rich.

He came out of prison to take farewell of a dying wife at a moment of crisis for Lew Haddin, of Haddin's Grand Travelling Amusement Park. That fat and illiterate man had employed a secretary to manage his private and business affairs, and the secretary had vanished with eighteen thousand pounds which he had drawn from Lew's London bank. And at the time Lew was wading through a deep and sticky patch of bad trading.

Joe was an excellent business man and, outside of his anti-social activities, an honest man. The death of his wife and the consciousness of new responsibilities had sobered him. He arrived at the psychological moment, had in an accountant to expose the tangle at its worst, and bought a half-interest in the amusement park, which for two years enjoyed exceptional prosperity.

The underworld also has its artists who work for the joy of working. There was no reason why Joe should fall again into temptation, but his draughtsmanship was little short of perfection, and he found himself drawing again. He might have confined himself to sketches of currency for his own amusement if there had not fallen into his hands the "right paper."

Now, the "right paper," is very hard to come by. As a rule, it does not require such an expert as Mr. Reeder to detect the difference between the paper on which English bank-notes are printed and the paper which is made for the special use of forgers. You can buy in Germany passable imitations which have the texture and the weight, and, to the inexpert finger, the feel of a bank-note. It is very seldom that paper is produced which defies detection.

Eight thousand sheets came to Joe from some well-intentioned confederate of other days, and his first inclination was to make a bonfire of them; but then the possibilities began to open up before his reluctant eyes... There was sufficient electric power at his disposal from the many dynamos they had in their outfit, and there were privacy and freedom from observation...

Mr. Reeder located Joe and put him under observation. A surreptitious search of his caravan revealed nothing. One morning Mr. Reeder packed his bag and went north.

There was a great crowd of people in the Sanbay Fair Ground when Mr. Reeder descended from the station fly which brought him to the outskirts of the town; he had not come direct from the station. He and his companion had made a very careful search of a caravan in a lock-up garage at the Red Lion.

Haddin's Imperial Circus and Tropical Menagerie occupied the centre of the ground. The tower of Haddin's Royal Razzy Glide showed above the enormous tent, and Haddin's various side-shows filled all the vacant sites. The municipality did not wholly approve of Haddin's, his band wagons, his lions and tigers, his fat ladies and giants, but the municipality made a small charge for admission to the ground, "for the relief of rates."

Mr. Reeder paid a humble coin, stoutly ignored the blandishments of dark-eyed ladies who offered him opportunities for shooting at the celluloid balls which dipped and jumped on the top of a water jet, was oblivious to the attractions of ring boards and other ingenious methods.

He had come too late for the only free attractions: the balloon ascent and the parachute jump by "the Queen of the Air." She was at the moment of Mr. Reeder's arrival resting in the big and comfortable caravan which was Mr. Haddin's home and centre.

But it was to see the "Queen of the Air" that Mr. Reeder had taken this long and troublesome journey. He sought out and found Red Joe Brady, whose caravan was a picture of all that was neat and cosy. Brady opened the door, saw Reeder at the foot of the steps, and for a moment said nothing; then:

"Come up, will you?"

He had seen behind Mr. Reeder three men whose carriage and dress said "detectives" loudly. "What's the idea, Mr. Reeder?"

Mr. Reeder shook his head sadly.

"All this is very unpleasant, Joe; and very unnecessary. I have searched that caravan of yours at the garage. Need I say any more?"

Joe reached his hat and overcoat from the peg. "I'm ready when you are," he said.

Joe was like that. He never made trouble where trouble was futile, nor excuses where they were vain.

Wenna heard the news after he had been taken away, and wept, not so much for Joe as for Danny, the boy who had spent his holidays with the circus and who had found his way into her susceptible heart.

Mr. Reeder was in the vestibule of the Old Bailey one day, and was conscious that somebody was looking at him, and turned to meet the glare of two eyes of burning blue fixed on him with an expression of malignity which momentarily startled him. She was very lovely and very young, and he was wondering in what circumstances he had deprived her of her father's care, when she came across to him.

"You're Reeder?" Her voice was quivering with fury.

"That's my name," he said in his mild way. "To whom have I the honour—"

"You don't know me, but you will! I've heard about you. You're the man who took Joe—took away Danny's father! You wicked old devil! You— you—"

Mr. Reeder was more embarrassed to see her weep than to hear her recriminations. He did not see her again for a very long time, and then in circumstances which were even less pleasant.

Generally speaking, Red Joe Brady was lucky to get away with ten years. Men had had lifers dished out to them for half that Joe had done.

AFTER his sentence Joe asked if he could see Mr. J.G. Reeder, and Mr. Reeder, who had no qualms whatever about meeting men for whose arrest and conviction he was responsible, went down to the cells under the court and found Red Joe handcuffed in readiness for his departure by taxi-cab to Wormwood Scrubbs.

Such occasions as these can be very painful, and it was not unusual for a prisoner to express his frankest opinions about the man who had brought him to ruin. But Joe was neither offensive nor reproachful. He was a spare man of medium height, and was in the late thirties or the early forties. His neatly brushed hair was flaming red—hence his nickname.

He met the detective with a little smile and asked him to sit down.

"I've no complaints, Mr. Reeder—you gave me a square deal and told no lies about me, and now I want to ask you a favour. I've got a boy at a good school; he doesn't know anything about me and I don't want him to know. I had the sense to put a bit of money aside and tie up the interest so that the bank will pay his fees, and give him all the pocket money he wants while I'm away. And a good friend of mine is going to keep an eye on him. The police don't know anything about the boy or his school. They're fair, I admit it, but they might go nosing around and find out that he's my son. They're fair, but they're clumsy, and it might happen that they'd give away the fact that his father was in stir."

"It's very unlikely, Joe," said Reeder, and the prisoner nodded.

"It's unlikely but it happens," he said. "If it does I want you to step in and look after the boy's interests. You can stop them going too far."

"Who is your 'good friend'?" asked Reeder, and the man hesitated.

"I can't tell you who he is—for reasons," he said.

There was something of uneasiness in his tone; only for the briefest moment did he reveal his doubt.

"I've known him years; in fact, he and I courted the same lady—my poor little wife, who's dead and gone. But he's a good scout and he's got over all that."

"Is he straight?" asked Mr. Reeder.

Joe was silent, pondering this question.

"With me, yes. Bob Kressholm—well, you know him, but he's never been 'inside.'"

Mr. Reeder said nothing.

"He's clever too. One of the wisest men in this country."

Reeder turned his grave eyes upon the man.

"I'd like to help you, Joe; but you'd be wise to give me the name of the school. I might do a little bit of overlooking myself."

Joe shook his head.

"I can't do that—I've asked Bob, and it would look as if I didn't trust him. All I want to ask you to do is to cover up the kid if anything comes out. I want that boy never to know what a crooked thing is."

The detective nodded, and they rose together. The taxi-cab was waiting and two warders stood by the open door. Joe changed the subject and considered his own and immediate misfortune.

"I can't understand how you got me," he said. "I thought I was well away with that second caravan. I hand it to you, you're smart."

Mr. Reeder offered him no enlightenment, nor did he ask the name of the boy. He knew that to the wild-eyed girl Red Joe was just "Danny's father." The next day he went in search of Bob Kressholm.

He found Bob sipping an absinthe frappé in a café near Piccadilly Circus. He was a lithe, dark man, who, in his confidence, surveyed the approach of the detective without apprehension; but when Mr. Reeder sat down by his side with a weary little sigh, Kressholm edged away from him.

"I saw a friend of yours yesterday, Mr.—um—Kressholm."

"Red Joe—yuh! I saw he'd gone down."

"Looking after his son, eh? Guardian of innocent childhood, H'm?"

Kressholm moved uneasily.

"Why not? Joe's a pal of mine. Grand feller, Joe. We only quarrelled twice—about women both times."

"You're a good hater," said Mr. Reeder gently.

He knew nothing then about Wenna Haddin and her ready knife. Nor what she had said to him about Danny.

He saw the man's face twitch.

"I've forgotten all about it—women do not interest me really."

Mr. Reeder sat, his umbrella between his knees, his bony hands gripping the crooked handle.

"H'm," he said, "a good hater. Joe wanted to know how he was caught. I didn't tell him that somebody called me up on the 'phone and told me all about the second caravan."

Kressholm turned his scowling face to the other.

"Who called you up?" he demanded truculently.

"You did," said Mr. Reeder softly. "You were under observation at the time—you didn't know that, but you were. I knew you were a friend of Brady's. I believe you were in the graft but I could never prove it. And you were seen to telephone to me from a public booth in the Piccadilly Tube at eleven twenty-seven one night—that was the hour at which the information came to him. Be careful what you do with that boy, Mr. Kressholm. That is all."

He got up, stood for a moment staring down at the uneasy man, and made his leisurely way from the restaurant.

Kressholm left London a week later, and very rarely returned; in the years that followed he proved himself an excellent organiser.

Danny Brady went out to him in less than a year.

In some mysterious way the story of his father's antecedents had reached the headmaster of his select school, and his guardian was asked to remove him. The boy came to see Wenna Haddin when the fair was at Nottingham. She was less depressed by his expulsion (for it was no less) than exhilarated by the prospect of his going to Paris.

A tall stripling, with dark auburn hair, he had grown since the girl had seen him last. She listened gravely to the recital of his plans, and her heart ached a little. If she did not like Mr. Reeder she hated Bob Kressholm.

"He's a queer man, Danny. I hope you'll be all right."

"Stuff! Of course I'll be all right," he scoffed. "Bob's a grand man—he wants me to call him Bob. Besides, he's a great friend of my father's."

She did not reply to this. Wenna was older than her years, knew men instinctively, and bitterly regretted all she had said about Danny that day in the wood, when she put into words the fantastical marriage plan of Danny's father.

So Danny went out; he came back a year later, a man, a careless, worldly young man, who had plenty of money to spend and had odd ideas about men and women, and the rights of property.

She used to correspond with him. Sometimes he answered her letters, sometimes months went past before he wrote to her.

Years went on, and Wenna seemed not a day older to him when he came back under a strange name. The old troth was re-plighted. He had had some experience in love-making. She felt curiously a stranger.

Two days after he left she heard of a big jewel robbery in Hatton Garden, and, for no reason at all, knew that he was the "tall, slight man" who had been seen to leave the office of a diamond merchant before his unconscious figure was found huddled up behind his desk. For by now Danny was an able lieutenant of the Governor.

ALMOST everybody associating with the criminal world had heard of "the Guv'nor." Scotland Yard referred to him jestingly. Inspector Gaylor did not believe in governors, except the "guv'nors" who ran the whizzing gangs, and he was acquainted with them because he had met and testified against these minor bosses, and had had the satisfaction, which only a policeman feels, in seeing them removed in the black van which runs regularly between the Old Bailey and Pentonville Prison.

But the real Governor, the big man, was a myth, a mariner's tale. Even when the jewel robberies began to assume serious proportions, nobody dared suggest that this visionary character had any connection with the crimes.

But to hundreds of lawless men, who spent the greater part of their lives in the cells of convict prisons, the Governor was a holy reality. He was immensely wealthy, he paid large sums to poor guys for their work and spent fortunes to keep them out of prison. At the very suggestion that a newcomer to Dartmoor was a highly paid lieutenant of the Governor, he was treated with respect which amounted to reverence.

This shining and radiant figure was, alas, unreachable. Nobody knew his identity. There was no channel by which a poor and bungling burglar might approach his divinity. They told stories about him—half-true, half-imaginary. He was a titled gentleman, who lived in a great house in the country and had his own motor cars and horses. He was a publican who kept a saloon in Islington. He was a trusted member of the C.I.D., who misused his position to his great advantage.

Certainly he chose discreet men to serve him, for never had any crime been brought home to him through the failure or loquacity of an assistant.

"The Governor!" said Inspector Gaylor scornfully, when there was first suggested to him the authorship of the Hatton Garden robbery. "You've been reading detective stories. That's Harry Dyall's work."

But when they pulled in Harry Dyall, his alibi was police-proof, and the more closely the crime was examined the more satisfied were the police that the robbery had been carried out by a master—which Harry was not.

"That's no corporal's job—it's a general's. If Bob Kressholm was in England I should say it was his," said Gaylor, who was called in by the city police.

It is very difficult for the police to believe in organised systems of crime carried out under the direction of one man.

"They meet in a dark cellar, I suppose," he sneered at the subordinate to whom the Governor was becoming a reality. "Wear masks and whatnots. Get that idea out of your mind, Simpson. Those things only happen in books."

The Governor and his general staff did not meet in dark cellars, nor did they wear masks. There is a big hotel near the Place de l'Opera in Paris which is rather noisy and rather expensive. The noisiest of all the rooms is the big saloon situated in one corner of the block. Here the incessant pip-squeak of taxi-cabs, the deep boom of motor horns, the thunder and ramble of cumbersome omnibuses are caught and amplified.

Four men played bridge; a fifth, and the younger, looked on impatiently.

The eldest of the four helped himself to a whisky and soda from a little table at his side, and threw down a card. The others followed suit mechanically. Nobody worried about the game. The cards might be convenient if some unexpected visitor arrived, though it was very unlikely that any such interruption would come.

"They called in Reeder over that Hauptman job of ours—you know that, Tommy?"

The man he addressed nodded.

"Reeder?" asked the young watcher. "Isn't he the fellow who pinched my father?"

Bob Kressholm nodded.

"Reeder is hot, but he doesn't as a rule touch anything but forgery. You needn't worry about him, Danny. Yes, he pinched your father. You owe him one for that."

The young man smiled.

"I remember—Wenna loathes him" he said. "Funny how women hold on to their prejudices. I was talking to her last week—"

Bob Kressholm's eyelids snapped.

"Talking to her—was she in Paris?"

For a moment Danny was embarrassed.

"Yes; she came over with her father to see a turn at the Hippique."

Kressholm was about to say something, but changed his mind.

"Anyway, Reeder's working with the police—he is in the Public Prosecutor's office now. You're not known in London, are you, Peter?"

Peter Hertz grunted something uncomplimentary about South Africa, a country where he was known, and Kressholm chuckled.

"Fine! But they don't send their prints over to Scotland Yard, so you're safe. Now listen, I've got a job for you boys..."

They listened for half an hour, and under his direction drew little plans on the backs of bridge markers. At eleven they separated. Danny Brady would have gone too, but the other asked him to wait behind.

"Stay on—I want to talk to you, kid." Kressholm was greyer than he had been when Red Joe went down for his ten.

"Why didn't you tell me Wenna was over?" he asked.

Danny looked uncomfortable.

"I didn't think you'd be interested, Bob," he said. Kressholm forced a smile.

"Always interested in Wenna—she doesn't like me. I saw her a couple of months ago and she treated me like a dog! God, she's lovely!"

That came out involuntarily. Danny's discomfort increased.

"She said nothing about me?" The young man lied with a head shake. "You and she are good friends, eh?"

"Why, yes. As a matter of fact, I gave her a ring—"

Kressholm nodded slowly; his blazing eyes were fixed on the carpet lest they betrayed him.

"Is that so? Gave her a ring? That's fine. I suppose you'll be thinking of throwing in your hand after this and settling down, eh? There's circus blood in you too."

Danny's face went red.

"I'm not going back on you," he said loudly. "I owe a lot to you, Bob—"

"I don't know that you do," said the other.

Here he did an injustice to himself as a tutor. For five years he had revealed wrong as an amusing kind of right, and black as an artistic variant of white. Crime had no shabby background in the golden flood-light of romance; its shabby rags, in the glamour with which he had invested them, became delightful vestments.

"You're doing the job—you're the Big Shot in the game, Danny. I wouldn't trust anybody but you. And talking of big shots—"

He went into his bedroom and came back with something in his hand that glittered in the lights of the chandelier.

"That's the first time I've trusted you with a gun. Don't be afraid to use it—you're not to get caught. There will be three cars planted for you with the engines running. I'll give you the plan. I'll have an aeroplane just outside of London. If you're pinched, don't worry: the Governor will get you out."

"That's the first time I've trusted you with a gun. Don't be afraid to use it."

The young man examined the revolver, fascinated. His hand trembled; he had a moment of exaltation, such as the young knight must have felt when the golden spurs were fastened to his heel.

"You can trust me, Governor," he breathed; "and if there's no get-out, send me the Life of Napoleon."

The Life of Napoleon had a special interest for the Governor's friends.

He stayed on for an hour whilst Bob talked about West End jewellers, their peculiarities and weaknesses...

MR. J.G. REEDER began to take a solicitous interest in West End jewellers' shops soon after the Hauptmann affair. For the Hauptmann affair was serious; that a shop manager should be bludgeoned in broad daylight and three emerald necklaces snatched from a show-case was bad enough; that the two thieves should escape with their booty was a very black mark against police administration.

Questions were being asked in Parliament, an under-secretary interviewed a police chief and made pointed comments on efficiency. Then it was that Mr. Reeder was asked to "collaborate." He was a member of the Public Prosecutor's staff, and for some strange reason was persona grata at Scotland Yard—which is odd, remembering how extremely unpopular non-service detectives are at that institution.

So it came to be that Mr. Reeder spent quite a lot of time wandering about the West End of London, his frock-coat buttoned tightly, his square-topped bowler hat at the back of his head, a disconsolate figure of a man. Jewellers came to know him; they were rather amused by his helplessness and ignorance of the trade.

One of them spoke to Inspector Gaylor.

"What use would he be in a raid? He must be a hundred years old!"

"A hundred and seven," said Gaylor soberly. "At the same time I wouldn't advise you to stand in his way if he's in a hurry."

Griddens was robbed that night, the contents of the strong room taken; the night watchman was never seen again. Then the Western Jewellers Trust had a visit which cost the underwriter twelve thousand pounds. Mortimer Simms, the court jewellers, was robbed in daylight.

Mr. Reeder was in bed when two of these robberies occurred. When he appeared after the Mortimer Simms affair he was subjected to a certain amount of derision.

But Mr. Reeder was not distressed. He continued his studies and delved into the mysteries of precious stones. He handled diamonds which were not diamonds but white sapphires, to the top of which a slither of diamond was attached. He examined samples of the faker's art which were entirely new to the detective. He learned of Antwerp agencies which were exclusively run for the disposal of stolen gems, and of other matters of criminal ingenuity which, he confessed in a tone of mingled admiration and shocked surprise, he had never dreamed about.

After the Mortimer Simms robbery he seldom left the West End; actually lived in a small hotel near Jermyn Street, and applied himself more closely to the study of jewels and their illicit collectors.

There was a long and blameless interval during which the Governor's men did not operate. Then one day a typewritten letter came to Mr. Reeder. It ran:

"Keep your eyes skinned. The Seven Sisters are going—and how! Conduit Street will be getting lively soon."

There was no signature. The paper on which the letter was written had a soft, matt surface such as you may find in the racks of any French hotel, and the "e" in "eyes" had been inadvertently typed "é." A week passed and nothing happened.

Then, on a dreary afternoon...

The Seven Sisters lay glittering in their blue velvet case for all who cared to stop and admire. They had been written about and photographed, and usually there was a sprinkling of people before Donnyburne's plate-glass window, doing homage to these seven perfectly matched diamonds which had once adorned a royal crown.

To-day, because it was raining and a gusty wind was blowing, people hurried down Conduit Street without pausing before the big jeweller's store to pay homage.

A big two-seater car drew slowly to the side of the kerb, passed in front of a stationary taxi-cab and came to a halt twenty yards west of Donnyburne's. A young man, wearing a long trench coat, got out at his leisure, examined one of the front tyres carefully, and walked slowly to the back of the car. A taxi driver, who stood on the edge of the kerb, smoking a short clay pipe, looked at the young man curiously, though there was little reason for curiosity, for there was nothing extraordinary about him. He was rather good-looking; his skin was a deep olive; on his upper lip was a small reddish moustache. The hair under the soft hat was red too, but nobody observed him very closely at the moment.

He walked back to Donnyburne's and stood before the window, examining the Seven Sisters. Then, without haste, he seemed to be drawing a circle with his finger. There was a curious squeaking sound, and when he pushed at the window the circle of glass fell inward. He lifted the case, snapped down the lid and walked back to where his car was waiting. The taxi driver had his back towards him, and saw him pass and jump into the car, which stood with its engines running. Then:

"Stop that man!"

Danny pushed inwards the circle of glass and snatched up the case of diamonds

Somebody screamed the words from the doorway of the jeweller's. It was unfortunate that a policeman turned the corner and came into sight at that moment. He saw the gesticulating shop assistant, and as the car moved he leaped upon the running-board and caught the left arm of the driver. For a second the young man jerked backward, but he could not loose the hold. His knees gripped the steering column as the car gathered speed; his right hand fell into his side pocket.

"That's yours," he said very calmly, and as cold-bloodedly as a butcher might destroy a beast, he shot the policeman through the face.

It was done in a second. He dropped the gun to his side, gripped the wheel and spun round the corner.

He had not seen the elderly man with the side whiskers and the queer top hat, a man who, in spite of the rain, did not wear an overcoat nor was his umbrella unfurled. If he had seen him he might not have considered Mr. Reeder a serious obstacle to his plans. Indeed, he gasped his amazement when, just as the car took a turn, he jumped to the running-board.

"Stop, please!"

The driver dropped his hand to his side. Before he could raise it something sprayed into his face, something that took the breath from his body and left him fighting for air.

Mr. Reeder switched off the engine, guided the car to the kerb, and allowed it to crash itself violently to a standstill against a stationary lorry. It had hardly stopped before he gripped the young man and dragged him on to the sidewalk.

Police whistles were blowing; he saw two policemen running, and handed over his prisoner.

"Search him before you take him to the station," he said gently. "It is quite permissible in the case of a man who is carrying dangerous firearms."

He picked up the pistol from the seat of the car, examined it carefully and dropped it into his pocket. The young man had recovered from the shock of the ammonia fumes that had been vaporised into his face, and by this time he was handcuffed. A cab drew up to the edge of the kerb, and the policeman signalled him.

"No, no." Mr. Reeder was very insistent. "There is too little room in a cab. Perhaps that gentleman would help us."

He nodded to a stout man in a big limousine which had pulled up to give its occupant an opportunity of satisfying his curiosity.

The stout man went pale at the suggestion that his car should be used for the conveyance of a murderer, but eventually he took his seat by the driver. It was to Marlborough Street that the prisoner was taken, and whilst the inspector was telephoning to Scotland Yard Mr. Reeder offered intelligent advice.

"Take every stitch of his clothing from him and give him new clothes, even if you have to buy them," he said. "I'm afraid I have a—um— rather—um—criminal mind, and I am just putting myself in this—er—unfortunate young man's place, and wondering exactly what I should do."

The clothing was removed; an old suit was discovered, and, by the time Chief Inspector Gaylor arrived from Scotland Yard, Mr. Reeder was making a very careful examination, not of the pockets, but of the lining of the murderer's discarded waistcoat. Between the lining and the shaped cloth of the breast he found a thin white paper which contained as much reddish powder as could be put upon the little finger-tip. In the lining of the coat he found its fellow. In the heel of the right boot, running the length of the sole, was a double-edged knife, thin and very flexible and keen.

"Pretty well equipped, Mr. Reeder." Gaylor viewed the discoveries with interest. "It almost supports your view."

"It quite supports my view, Mr. Gaylor, if you will allow me to say so." Mr. Reeder was apologetic. "As a rule I do not believe in—um— organised crime. The story of Napoleon Fagins at the heads of large bodies of men banded together for—um—illegal purposes is one at which—well, frankly, I have smiled hitherto."

"He got away with the Seven Sisters, eh?" Mr. Gaylor looked around. "Where are they?" Mr. Reeder shook his head.

"I'm afraid they're not here. That is one of the mysteries—indeed, the only mystery—of the raid. The assistant saw him from the moment he committed the crime till the moment he got into his car. When we arrested him we found neither the diamonds nor the case. The car is in the yard, being scientifically dissected, if I may employ so gruesome an illustration. I picked up the machine as it came round the corner, and there was no chance of his getting rid of the diamonds whilst he was under my eye.

"I searched his pockets the moment the police came up. And that—um—is that."

It was no coincidence that he had been in the region of Donnyburne's that afternoon. Mr. Reeder did not as a rule pay very much attention to anonymous "squawks," but he had been impressed by the paper, and the "e" with the acute accent. Such an afternoon was climatically most favourable for such a raid, and it was only by a fluke that he was not an actual witness of the murder. He had heard the shot and almost instantly the murderer's car had come into sight.

"He has given the name of John Smith, which is highly unimaginative. There are no papers to identify him. The car was hired from the Golston Garage—hired by the week, and a substantial deposit paid. John Smith has been seen in the West End of London, but nothing is known against him, and for the moment it is impossible to trace his address. I should imagine that he was living at a good hotel somewhere in the West End of London. He has lived in Paris, I should think; his shoes, his shirt and his necktie are French made. He probably arrived in London a week ago."

There was nothing to be gained by questioning John Smith. He seemed to feel the disgrace of wearing block-made clothes more acutely than the brand of murderer, and when the inspector questioned him he was indifferent and unrepentant.

"There's one thing I'd like to ask you—was that old bird who gassed me J.G. Reeder? I'd like to have him alone for a few minutes."

"You with a gun, I suppose?" said Gaylor savagely.

He was no philosopher where a comrade had been killed in the execution of his duty. People who kill policemen receive no consideration from such of the police as happen to be alive.

"With your hands, eh? He'd beat the life out of you, you dirty murderer!"

John Smith was amused.

"I shan't hang, don't worry," he said, almost airily. "Don't ask me who my confederates are, because I wouldn't dream of telling you. Besides, the new police regulations prevent your asking me questions, don't they?"

He showed two rows of even white teeth in a smile.

HE was as confident the next morning, the more so since his hotel address had been discovered and he was allowed to wear his own clothes, after they had been carefully searched.

The proceedings at the police court were formal. An indubitable murderer was in custody, and for the moment the police were concentrating on their search for the missing diamonds. Whither they had gone was a mystery. The taximan whose cab was near Donnyburne's said he had seen the murderer carrying a blue velvet case in his hand; that was the first thing that aroused his suspicion. He had not seen the murder committed; he had been looking round at the moment for his fare, a middle-aged lady whom he had picked up at Victoria and who had kept him waiting an hour, and eventually had not returned.

"It's the first time I've been bilked for ten years," he said. He had this little trouble of his own.

He had heard the shot, had seen the car go round the corner, leaving a dead man lying half in the road and half on the sidewalk, and had run to his assistance. A woman who was walking on the other side of the road, who also had heard the shot and had seen the machine pass on, was emphatic that nothing had been thrown from the car, nor did it seem likely to Mr. Reeder that the robber should attempt to throw away the gems he had won so dearly.

The car, as he had said, had been inspected, the lining removed, and had been stripped to its chassis and the inner panelling unscrewed. But there was no sign of the seven diamonds.

Not for the first time in his life, Mr. J.G. Reeder was up against the unbelievable. He had scoffed at gangs all his life; and here undoubtedly, and in the heart of London, was operating no mere confederacy of two or three men, whose acts were dictated by opportunity and expediency, but a body directed by a master mind (Mr. Reeder shuddered at the discovery that he was accepting such a bogey as a master criminal), operating on pre-determined plans and embodying not one branch of the criminal profession but several.

After the police court proceedings he went, as usual, by tramcar, a sad-looking figure, sitting in a corner seat, resting his hands upon the handle of his umbrella and expressing his gloom on his face.

The long journey was all too short for him, for he was resolving many things in his mind.

It was dark when he came to Brockley Road. As he alighted from the car and cautiously crossed that motor-infected thoroughfare he was amazed to see a familiar figure standing on the corner of the street. Gaylor did not often honour him by visiting the neighbourhood.

"You are here, are you?" Inspector Gaylor was obviously relieved.

Another man had alighted from the tramcar at the same time as Mr. Reeder, but he had hardly noticed him.

"It's all right, Jackson." Gaylor addressed him familiarly. "You'll find Benson up the road. Stay outside Mr. Reeder's house. I will give you fresh instructions when I come out."

They passed into Mr. Reeder's modest domicile together.

"You've got a housekeeper, haven't you, Mr. Reeder? I'd like to talk to her."

Mr. Reeder looked at him, pained.

"Aren't you being a little mysterious, my friend? You may think it odd, but I detest mysteries."

He was saved the trouble of ringing for his housekeeper, for that amiable lady came from some lower region to meet her employer.

"Has anybody been here?" asked Gaylor.

Mr. Reeder sighed, but did not protest.

"Yes, sir, a gentleman came with a letter. He said it was very urgent."

"Nothing else?" asked Gaylor. "He didn't leave a parcel?"

"No, sir," said the housekeeper, surprised.

Gaylor nodded.

The two men went to Mr. Reeder's study. The curtains were drawn, a little fire burned in the grate. It was one of those high-ceilinged rooms, and had an atmosphere of snug comfort. Gaylor closed the door.

"There's the letter." He pointed to the desk.

It was typewritten, addressed to "J.G. Reeder, Esq." and marked "Very Urgent."

"Do you mind seeing what it says?"

Mr. Reeder opened the letter. It was a closely typed sheet of manuscript, which had neither preamble nor signature. It ran:

Re John Smith. I am asking you what may seem at first to be an impossible favour. You are one of those who saw the shooting of Constable Burnett, and your evidence will be of the greatest importance in the forthcoming trial. I do not hope to save him if he comes into court. If you will help him to escape by such methods as I will outline to you, I will place to your credit the sum of fifty thousand pounds. If you refuse, I will kill you. I am putting the matter very clearly, so that there can be no mistake on either side. It is not necessary to tell you that fifty thousand pounds will provide you with comfort for the rest of your life and place you in a position of independence. I promise you that your name will not be connected with the escape. John Smith must not hang. I will stop at nothing to prevent this. Nothing is more certain than that you will meet your death if you refuse to help. If you are interested, and you agree, insert an advertisement in the agony column of The Times next Tuesday, in the following terms:

"JOHNNY,—meet me at the usual place.—JAMES."

and we will go further into this matter.

Reeder put down the letter and stared incredulously at his companion.

"Well?" said Gaylor.

"Dear me, how stupid!" murmured Mr. Reeder. He looked up at the ceiling. "That makes forty-one, or is it forty-two?"

"Forty-two what?" asked Gaylor curiously.

"Forty-two people have threatened to take my life if I didn't do something or other, or because I have done something—or is it forty-three?"

"I have had a similar letter," said Gaylor. "I found it at my house when I got home to-night. Reeder, this is one of the biggest things we have ever struck. It is certainly the biggest thing I have ever known in my experience as a police officer. It is something more than an ordinary gang. These people have money and probably influence, and for some reason or other we have hurt them pretty badly when we took this young man. What are you going to do?"

Mr. Reeder pursed his lips as if his immediate intention was to whistle.

"Naturally, I shall not put in the advertisement as our friend suggests," he said. "Why next Tuesday? Why not to-morrow? What is the reason for the delay? The letter was urgently delivered; it is sure to call for an urgent reply. It is a little too obvious."

Gaylor nodded.

"That is what I thought. In other words, nothing will happen to you until next Tuesday. My impression is that we are in for a troublesome time almost immediately; that is why I telephoned to the Yard to have one of my men pick you up and shadow you down here. These people will move like lightning. Do you remember what this fellow said this morning in court? The whole story was a fabrication and a case of mistaken identity. That is a pretty conventional excuse, Reeder, but it was very well timed. Who are the witnesses against this man? You are one of the principals; I am, in a way, another. The shop assistant is a third. The two policemen who arrested him hardly count. Huggins, the taxi-driver, one of the most important, disappeared at six o'clock this evening."

Mr. Reeder nodded at him thoughtfully. "I foresaw that possibility," he said.

"His taxi-cab was found in a side street off the Edgware Road," Gaylor went on. "There was blood on the seat and on the window of the cab. He lives over the mews very near the place where it was found. He hasn't been home, and I don't suppose he'll come home," he added grimly. "I have got two men looking after the shop assistant, who lives at Anerley. He also has had a warning not to go to court. Does that strike you as interesting?"

The fatal cab was found by a policeman... There was blood on the seat and over the wind-screen.

Mr. Reeder did not answer. He loosened his frock coat, put his hat carefully on a side table and sat down at his desk. He stared absently at Gaylor for some time before he spoke, then, opening a drawer, he took out a folder and extracted two sheets of foolscap.

"It is very bad to have preconceived ideas, Mr. Gaylor," he said. "I did not believe in gangs. I thought they were a figment—if you will excuse the expression—of the novelist's imagination, and here I am discussing them as seriously as though they were a normal condition of life. By the way, I knew the cabman had disappeared. It was silly of us not to have arrested him—in fact, I went to arrest him, and then I heard of the—um—accident."

Gaylor gaped at him.

"Arrest him?" incredulously. "Why on earth?"

"He had the Seven Sisters—the diamonds. Obviously nobody else could have had them. They were tossed into the cab by Smith—whose name, I think, is Danny Brady—as he passed. In fact, the cab was planted there for the purpose. Huggins—an interesting name— was one of the gang. The blood-stained cab is picturesque, but unconvincing. I should have the Channel ports very carefully watched and circulate a description of the—um—deceased."

MR. REEDER'S theory had a rapid confirmation. "Huggins" was picked up the next night, not at a Channel port, but at Harwich, and he took his place in the dock as an accessory to the murder.

Friday came and passed. There was no evidence of reprisal. Gaylor would have placed detectives on guard before and in Mr. Reeder's house, but that gentleman grew so unusually testy at the suggestion that the inspector decided to let his colleague die any way he wished.

"Die be—um—blowed!" said Mr. Reeder, and apologised for his vulgarity. "That letter was what is called in America a—um—'front.' In other words, it was a show-off and meant nothing. I suspect friend Kressholm is establishing an alibi."

"A little late for an alibi," said Gaylor.

"Not so late as you think," was Reeder's cryptic reply.

It was during the trial of Daniel Brady that Kressholm came to London. There was no reason why he should not. He held a British passport, and there was not a scrap of evidence to connect him with the crime.

He had not been at his hotel five minutes when they telephoned from the inquiry office to ask him if he would see a lady. Before they told him Wenna's name he knew who it was.

Sorrow had refined, as it had aged, her. He never realised how much older than Danny she was till he saw that pale, haggard face.

"I've seen Danny," she said breathlessly. "He told me that he was coming to London. I've called here three times this afternoon. He believes in you—"

"What did he tell you?" His voice was sharp.

The two men seized their victim and dragged him from the interior of the van.

Danny's confidence in him did not outweigh his alarm. That he should be even remotely associated with this crime...

She shook her head impatiently.

"You needn't worry, Kressholm; I know you are in this. No, no, he didn't tell me, but I know. What can we do? You've got to save him."

He was staring at her hungrily, and, distressed as she was, she did not realise that even in this tragic moment his interest was for her and not for the man who stood in the shadow of the scaffold.

"I don't know what we can do. I'm getting the best lawyers. Only Reeder's tied him up pretty completely."

"Reeder" she gasped. "That old man! Has he done this?"

Bob Kressholm nodded.

"He's always been down on the Bradys," he said glibly. "That old bird will rather die than let up on Danny. He was waiting for him—in fact, he arrested him."

She sat down heavily in a chair and buried her face in her hands. He stood looking at the slim, bent back. That must be the ring that Danny gave her —the glittering sapphire on her finger. He went angrily hot at the thought.

It must be ten years since that disagreeable episode in the wood. She had forgotten all that perhaps... he had been a little raw. At any rate, she had forgiven him or she would not be here.

"I hate to see you like this, Wenna," he said. "I'll fix Reeder for you one of these days."

She sprang to her feet, her eyes blazing.

"One of these days—you? Don't worry, Kressholm, I'll fix him. If anything happens to Danny—" Her voice broke.

He soothed her with the clumsiness which was part of his insincerity.

She would have attended the trial, but he dissuaded her; she would upset Danny, he said. In truth he was anxious that she should not meet Reeder, that astute man who had a disconcerting habit of telling unpleasant truths, and he was glad that the girl had taken his advice when, on the opening day of the trial, Reeder approached him outside the Old Bailey.

"You're giving evidence, of course, Mr. Kressholm?"

The other man turned his suspicious eye upon his questioner.

"What do I know about it? I know Danny, of course, but I've been out of the crooked game so long that he wouldn't have told me he was going to do a fool thing like shooting a copper."

"Indeed?" Mr. Reeder inclined his head graciously. "I suppose that governors do not take risks—"

"Governors!" said the man scornfully. "Where did you get that word? You've been listening to those penny-dreadful flatties at the Yard! No, I tried to keep the boy straight he's the son of my pal, and that's why he is having all the legal assistance that money can buy."

"And Mr. Huggins—who, by the way, was identified this morning by a South African police officer, who happened to be in London, as Peter Hertz —is his father a friend of yours?"

For a second Bob Kressholm was embarrassed.

"Naturally I shall look after him," he said at last. "I don't know the bird, but they say that he is a friend of Danny's. I don't even know the gang."

Mr. Reeder looked down at the pavement for a long time.

"Is there anything wrong with my boots?" asked Kressholm facetiously.

Mr. Reeder shook his head.

"No—only I shouldn't like to be standing in them," he said. "Red Joe Brady is due for release in a month's time."

He left the master-man with this unpleasant reminder.

The trial ran its inevitable course. On the second day the jury retired and returned with a verdict of guilty against Brady and Hertz. Danny was sentenced to death and Hertz to fourteen years' penal servitude.

Mr. Reeder was not in court. It was not his business to be there, so he did not hear the commendations of the judge, or see Danny's frosty smile as the sentence of death was passed and there came to him the realisation that the all-powerful Governor was for once impotent. He had listened to Reeder's evidence closely, and only once did he appear startled; that was when the detective told of the warning he had had that the Seven Sisters were threatened.

Mr. Reeder read the account in the late editions of the newspapers and sighed drearily.

Kressholm was not in court at the last, and had asked for an interview with the young man, a request which was refused.

It was nearly midnight and Mr. Reeder was preparing to go to bed, when he heard the front bell ring. He had had installed a small house telephone on to the street. It saved him a lot of trouble when his housekeeper had gone to bed. He pressed the knob which lit a small red lamp in the lintel of the street door and incidentally showed the concealed receiver of the 'phone, and asked:

"Who is there?"

To his surprise, "Kressholm" was the reply.

Kressholm was the last man in the world he expected to see that night. He went downstairs slowly, switched on the light in the hall and opened the door. The man was alone.

"I'm sorry to disturb you—" he began.

"I'll take your apologies in my office," said Reeder. "Do you mind walking ahead of me?"

He followed the visitor into the big room which was office and living-room, and, closing the door, pointed to a chair.

"I'll stand," said Kressholm shortly.

He was nervous. His restless hands moved from one button of his overcoat to the other. He put down his hat in one place, took it up and put it down in another.

"I want you to understand, Reeder," he began.

"Mister Reeder," said that gentleman gently. "If ever I put you in the dock you can call me what you like; for the moment I would rather be called 'mister' which means 'master,' and I will be your master sooner or later, or my name is Smith!"

Kressholm was taken aback by the correction. He scowled a little and then laughed nervously. "Sorry, Mr. Reeder, but this case has rattled me. You see, the boy was in my charge. His father and I were old friends."

Mr. Reeder had sat down at his writing-table. He leaned back now and sighed.

"Is all this necessary?" he asked. "It is not conscience that has brought you here; it is blue funk, isn't it?"

Kressholm went an angry red.

"I am afraid of nobody in the world." He raised his voice. "Not you —, and not that damned—"

"S-sh!" J.G. Reeder was apparently shocked. "I do not like strong language. You are afraid of nobody but Red Joe. I wonder, too, if you are afraid of that little circus girl who has paid several visits to your hotel? Miss Haddin, isn't it?"

Bob Kressholm stared but said nothing. He found a difficulty in speaking.

"She was—um—engaged to the young man. A fiery young woman; I remember her—yes. If she knew what I know—"

"I don't know what you mean," said Kressholm huskily.

"Then let me tell you why you have called on me," said Mr. Reeder.

He folded his arms on the table and fixed the other with a steely eye.

"When I see his father, you want me to tell him that I and Mr. Gaylor were offered fifty thousand pounds to secure his escape. We were also threatened with death if we did not agree."

Kressholm's face was ludicrous in its blank amazement.

"That is just what you wished to ask me," Mr. Reeder went on; "but you don't exactly know how to broach the subject. Well, it is difficult to convey to a police officer the fact that you have both tried to bribe and threaten him without involving yourself in a lot of trouble. I will save you a little trouble, anyway. You were establishing your defence. You trained this boy the way he has gone, and it is going to take the whole Metropolitan Police Force to save your life. If you are wise you will go back to France and let Red Joe give the French police the bother of arresting him for your murder."

"If you think I am afraid of Red Joe—"

Mr. Reeder nodded.

"You are terrified, and I think you have very good reason."

Reeder walked to the door and opened it.

"I don't want to talk to you any more, Kressholm." He glanced down. "I see you are wearing shoes this evening. Well, I should not like to be in those, either."

Kressholm gave no further explanation. None of his gang, seeing him now, would have recognised the ruthless Governor they knew.

DANNY BRADY was a foolish young man, but he had quite enough intelligence to know that his appeal, which he would make automatically, was doomed to failure. He was completely satisfied on the subject when the governor, making his morning visit to the condemned cell, told him that a parcel of books had arrived for him.

He showed Danny the list and told him he could have one volume at a time. Danny chose The Life of Napoleon. He spent the greater part of the day writing a letter to the girl he would never see again, and took The Life of Napoleon to bed with him. About eleven o'clock he put the book on the floor.

"Leave it there," he said to one of the watchers. "I don't think I am going to sleep very well to-night."

Now, a condemned prisoner may not sleep with his face covered. When Danny drew the coarse sheet over his head one of the watching warders admonished him.

"Turn down that sheet!" he said.

Just at that moment the sheet began to go red very rapidly, for Danny had cut his throat with a safety razor blade which had been carefully bound into the cover of the book.

All the available doctors could not save Danny's life; he died before twelve. The prison governor and four warders sat up all night long taking evidence from the warders concerned.

Mr. Reeder went down and saw the book. Afterwards he called at a London hotel where he knew Kressholm was staying. The man had recovered something of his old poise. He expressed his deep sorrow at the death of his young friend, but could give no information about that fatal Life of Napoleon. He admitted that in his youth he had been a bookbinder—that fact was registered on his documents at Scotland Yard, for Bob Kressholm had been twice in the hands of the police.

"I know nothing about it," he said. "I only put 'bookbinder' because I thought I'd get an easy job in prison. I don't see how the razor blade could be put into the binding—"

"It is a very simple matter," said Mr. Reeder patiently. "The boy had only to tear off the inside paper, and it was easy, because it was stuck with gum that had not even been set."

He and Gaylor made a search of the man's baggage, but found nothing in the nature of a bookbinding outfit. There was not sufficient evidence to have justified an arrest, but Kressholm spent that night in Scotland Yard answering interminable questions, and was a weary man when they had finished with him.

The sensation came into the afternoon papers in the shape of a short paragraph issued by Scotland Yard.

"Daniel Brady, lying under sentence of death, succeeded in committing suicide last night at eleven o'clock. The weapon was a safety razor blade which had been smuggled into the prisoner, bound in the cover of a book, by some person or persons unknown."

It was the next day that the inquest provided the full story of the tragedy. Mr. Reeder read it from start to finish, though he had heard the evidence of every witness before the case came to court. He was reading the newspaper in the room where he had interviewed Kressholm, and had put it down by his side, when there was a tap at his door and his housekeeper came in.

"Will you see a man named Joseph Brady?" she asked.

Mr. Reeder drew a long breath. He looked from the woman to the newspaper, then picked up the paper, carefully folded it and put it into his wastepaper basket.

"Yes, I will see Joseph Brady," he said softly.

Joe had not changed, save that his hair, which had been red, was almost white, and the smooth face that Reeder had known was drawn and haggard.

Reeder pushed up a chair for the stricken man, and he dropped into it. For fully five minutes neither spoke, then Joe lifted his head, and said:

"Thank God he went that way!"

Reeder nodded.

"I read about the case in prison." Brady's voice was even and steady. "I thought I'd get to London in time to see him, but I got there the morning after it happened. I could have seen him then, but it would have meant going to the inquiry and giving evidence, and telling a lot of things that I want to keep to myself."

There was another long interregnum of silence. The man sat, head bent, his arms folded on his breast. He showed no other evidence of his emotion. After a while he looked up.

"You're as straight a man as I've ever met, Reeder. I've heard other lags say they look upon you more as a pal than an enemy, but that isn't why I've come to see you. I've come to talk about"—there was a pause— "Kressholm—Bob Kressholm."

"Why bother with him?" asked Mr. Reeder, and knew he was saying something very inane.

A quick smile came and left the man's face.

"I thought I'd tell you something. I know all that Kressholm's done to my boy, and I know why he did it—about this kid Wenna, I mean. No, I haven't seen her, I won't see her yet. I've been talking with the boys, you know—the underworld, you call it—"

"I don't, but quite a lot of people do. And what did they tell you?"

"They say Danny was caught on a squeal—that somebody planted you to get him. The same man, I guess, who told you about my printing plant in the caravan." He paused expectantly, and when Mr. Reeder said nothing he laughed harshly. "I thought so! I've got money—stacks of it. I'm one of the few crooks who have ever made a fortune and kept it. I'm going to spend that money wisely. I'm going to use it to kill Kressholm."

Mr. Reeder murmured something admonitory, but the man shook his head.

"I'm telling you that I'm going to kill him. That's going to be my little joke. But I shan't be caught, and I shan't be punished. I'm going to hang him, Reeder—hang him by the neck till he's dead. That's the sentence I've passed on him! And neither you nor any other man will know it. That's the thought that's keeping me sane."

"You're mad, you fool," said Mr. Reeder, with unusual roughness. "No murderer ever gets away with it in this country. I'm not taking too much notice of what you say—I feel terribly sorry for you. If I were not an—um—officer of the law I should say he deserved almost anything that's coming to him. Get out of the country—go to the Cape or somewhere. I'll help you at Scotland Yard—"

Red Joe shook his head.

"I stay here. I'm not leaving this country even if Kressholm leaves. He'll come back—there's nothing more certain than that—and I'll kill him, Reeder! I came to tell you that, and to tell Scotland Yard that."

He picked up his hat and walked to the door. For once in his life Mr. Reeder found himself entirely devoid of speech. He walked to the window and looked out: a taxi-cab was waiting; he saw the man enter and drive off, and, going back to the telephone, he called Gaylor.

The inspector was out and was not reachable. Mr. Reeder contented himself with writing the gist of the interview and sending it by express post to Scotland Yard.

It occurred to him afterwards that it was his duty to arrest the man summarily; he was a convict on licence, and had uttered threats to murder, which in itself was a felony. But somehow that solution never occurred to Mr. Reeder. And it must be admitted, although he was on the side of the law, that it took him a long time to energise himself into ringing up the hotel where he knew Kressholm was staying. He did not expect to find that good hater, and was surprised when, after a short delay, Kressholm's voice replied to his.

The man listened and laughed scornfully. Evidently something had happened which had removed his fear of Red Joe, and what that something was Mr. Reeder was curious to know, but was not satisfied. It was Bob Kressholm who pointed out the strict path of duty, and Mr. Reeder was pardonably annoyed.

"If he threatened me why didn't you pinch him?" demanded Kressholm. "You'd look silly if he did me in—but he won't."

"Why are you so sure, my dear friend?" asked Mr. Reeder gently.

"Because, my dear friend," mocked Kressholm's voice, "I am a pretty difficult man to reach."

MR. REEDER was well aware of the fact; Kressholm never moved without his escort of gunmen. He had seen them hovering in the background that day at the Old Bailey. Not for nothing was he called "the Governor"; the very title presupposed a following. He had doubled his escort since he heard that Red Joe was out of prison. His men slept in the rooms on either side of his. He had a guard outside the hotel.

Kressholm would have gone to Paris—he knew the bolt holes better there, and had a certain pull with important officials, and, but for Wenna, he would have left England on the day of the inquest. But Wenna was unusually humble and pathetically helpless. Old Lew Haddin came down to London to bring her back to the show. He was not so much concerned by the tragedy which had broken her as by the loss of an attraction.

"I'll come when I'm ready," she said.

Lew complained sadly to Kressholm that girls were quite different from what they had been in the days of his mother.

"No respect for God or man—or fathers," he quavered. "She's afraid of nothing. She was making lions jump through hoops when she was ten, and she thinks no more of dropping two thousand feet on a parachute than you and me would think of walking downstairs."

He complained, but left her alone.

She had so far forgotten her old detestation of Bob Kressholm that she used to go to dinner with him in his suite. If she contributed nothing to his happiness—for she would sit for hours, hardly speaking a word, staring past him—she added zest and determination to this man who was in her thrall. He saw a grand culmination to these years of disappointment and rebuff. Red Joe he did not fear—he would be "taken care of." If he were uneasy at all it was because Joe made no direct attempt to see him, did not communicate by word or letter.

Though he professed to be without fear, he heaved a sigh of relief when he heard, from the man whom he had set to shadow him, that Brady had left one afternoon for the Continent. For one moment he had an idea of ringing up Scotland Yard and reporting this irregularity. A convict is not allowed to leave the district to which he is assigned, and a breach of this law might bring about his return to prison to complete his sentence.

Only once he spoke to Wenna Haddin about Joe. She answered his question with a shake of the head.

"No, I haven't seen him—poor man; I expect he's too heartbroken to see anybody. I think if anybody loved Danny as much as I did it was his father."

She thought for a long time, then she said: "I'd like to see him. Perhaps he'd help."

"With Reeder?" And, when she nodded: "Don't be silly! Joe thinks Reeder is the best chap in the world! That surprises you, doesn't it? But then, you see, Joe doesn't know what Reeder's done for him. That old man is as artful as the devil. If you told Joe he'd laugh at you."

She was eyeing him steadily.

"Why? If you can convince me you could convince him."

He was rather taken aback.

"I didn't convince you, I merely told you the truth," he said.

She did not answer this, and he reached out and laid his hand on hers. She made no attempt to withdraw it.

"Poor Red Joe!" Her voice softened.

He never knew how simple or complex she was; whether she was either, or just a humdrum medium made radiant through the eyes of his passion. Old Lew Haddin, white-haired and obese, could talk for hours in his monotonous, sleep-making voice and always the subject was Wenna and her peculiar values. Red Joe once said she had the brains of a general, but, by accounts, some generals are rather stupid.

"Why poor Joe?" he asked, and suddenly tightened his grip on her hand.

"We have kept his caravan just as he left it," she said. "Nobody uses it, of course; I tidy it every week. Lew grumbles at the cost of haulage" (she invariably referred to her parent in this familiar way) "and deducts it from Joe's share; he owns half the park." As she spoke she looked at him oddly. "You are a friend of Joe's?"

"Yes."

She nodded.

"Then I can ask you something. He was charged with forging bank-notes, wasn't he? Could they imprison him again supposing they found something else against him?"

Kressholm became suddenly very attentive. "Like what?" he asked.

"Bonds and letters of credit. I found the plates in the wall lining of the caravan. He had a sort of secret panel there. Nobody knew it."

Bob Kressholm's heart leapt.

"Are they there still?" he asked. He tried to give a note of carelessness to his inquiry.

She nodded.

"Yes, the plates, and the papers, and everything, Could the law punish him for that?"

He considered this.

"I shouldn't think so," he said.

He had hazy notions about the English law, but here he saw the making of a second charge, which might easily dispose of a serious menace. She told him that Joe had had an assistant, a man who still worked with the circus, and who was the only person beside herself who had access to the van.

When he left her that night Kressholm had made up his mind. He tried to get in touch with the detective, but J.G. Reeder was out of town. He was working on a case in the South of England. What that case was Kressholm learned from the newspapers, and his hopes rose higher.

MR. REEDER was very heavily engaged, but found time to call at Kressholm's hotel.

"I'd have come to you—" began Bob.

"I'd rather you didn't." J.G. could be offensive on occasions. "I have already a—um—bad name in Brockley."

Kressholm swallowed this with a grin.

"I noticed in the newspapers that you were working on a case, and I wondered if I could help you," he said. "I'd like to do you a turn if I could."

"I'm so sure of that," murmured Mr. Reeder. "It is a great joy to know that one's efforts are appreciated by the—um—unconvicted classes."

Without further preliminary Kressholm told him of what he had learnt from the girl, and J.G. Reeder listened without apparent interest. Yet, if this story were true, here was a big link in the chain he was piecing together with such difficulty.

"Are you sure that this story isn't suggested by the foolish paragraph you read in the newspapers?" he asked.

"If I die this minute—" began Kressholm.

"You would go straight to hell," said Mr. Reeder gravely. He was one of those old-fashioned people who believed in hell.

"No, this is straight, Mr. Reeder," protested Kressholm. "I thought that you ought to know this. I'm not telling you this because I am scared of Joe, so that I want to get him out of the way. I am telling you—well, because I feel that you ought to know."

Mr. Reeder nodded slowly.

"In the interest of justice, of course," he said. "Very—um— commendable. Where is this—er—entertainment park at the present moment?"

"They will be near Barnet next Monday," said Kressholm; then, anxiously: "What is the law on the subject, Mr. Reeder?"

J.G. pursed his lips thoughtfully.

"I'm not a lawyer," he said. "But, of course, it is very, very wrong to —um—be in possession of the instruments of forgery. And this assistant, you say, is still carrying on the—er—bad work?"

"So she—so I understand," Kressholm corrected himself hastily.

He offered a suggestion which was received without comment: Joe's caravan was invariably parked on the outside edge of the camp, and could be approached without observation. The night watchman who patrolled the fair-ground rarely went as far.

"I will undertake to get you the key of the van. As a matter of fact, I am staying the night on Monday. I suppose you could get a search warrant and that sort of thing; but I am asking you as a personal favour to make sure I'm right before you get a warrant. I do not want to be brought into this."

"You don't want to be brought into anything, Mr. Kressholm," said Reeder unpleasantly. "Hitherto you have been very successful. Is the young lady a friend of yours now?"

If he had stopped to think Bob Kressholm would have realised that no young lady's name had been mentioned.

"We have always been good friends," he said, and then realised his mistake. "I suppose you mean Miss Haddin I don't know what she's got to do with it."

"A nice young lady, but rather—impetuous," said Mr. Reeder. "She thought I was responsible for Joe's arrest, when really it was you. She probably thinks I was responsible for Danny Brady's death, when it was —um—you know, I think, who it was. It is all very interesting."

Mr. Reeder had something to think about. Nobody credited so staid and matter-of-fact a man with such an insatiable sense of curiosity as he possessed. All that night until he retired to his chaste bedroom he pondered the information Bob Kressholm had offered. His acquaintance with the law told him that the re-arrest of Red Joe would be followed by an acquittal. The man had served imprisonment for an act of forgery and if some other act, which had occurred concurrently, was revealed, the law would take a lenient view.

The mysterious assistant was another matter. Mr. Reeder had not heard of an assistant, but then there was quite a number of happenings about which he knew nothing.

It was a coincidence that he had been occupied for two or three days with the matter of forged letters of credit. There was no secret about this. The fact that the forged letters had been cashed and that Mr. J.G. Reeder, "the well-known forgery expert," had been in consultation with certain bank managers in Brighton had been published in the morning newspaper, and had been read by Kressholm. The man who was passing the letters had also negotiated some bearer bonds of a spurious character. That fact, too, was public property.

And yet all the evidence he had accumulated pointed to a certain hochstapler in Berlin, about whom the Berlin Criminal Police were pursuing close inquiries. There was a German end to it beyond any doubt, but that did not mean that the letters had not been forged in England. A search warrant would be easy to secure, and as easy to execute. Yet he hesitated to make the necessary application. If the truth be told, Mr. Reeder had a sneaking sympathy with Red Joe.

The police thought they had removed every kind of plate and press from the van. It was quite possible that the press had been renewed and was being employed to print from the plates which only Joe could have made. He consulted Gaylor on the subject, but the inspector was not enthusiastic. It was one of those frequently recurring periods when the police were unpopular because they had failed to secure two important convictions, and the usual questions were being asked in the House of Commons.

"It's the German crowd, I should think. Where did you get the information from? I'm sorry."

That was a question that police officers did not ask Mr. Reeder; he either volunteered the source or refused it, for he was very jealous about betraying the confidence of the least worthy of men. There was reason in this, because such revelations frequently compromised other and more important "squeaks."

Reviewing all the possibilities, J.G. Reeder decided not to pay a nocturnal visit to the Haddin menage, and when Mr. Kressholm rang him up at his home, he cut short the elaboration of that gentleman's instructions.

It was a disappointed man who travelled to Barnet on the Monday afternoon, though his discomfort was short lived.

He had re-established contact with Wenna Haddin—an amazing accomplishment, all the more remarkable because he had recovered all the old fascination she had exercised. Ten years is a very long time; men and women change in that period, especially women.