RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

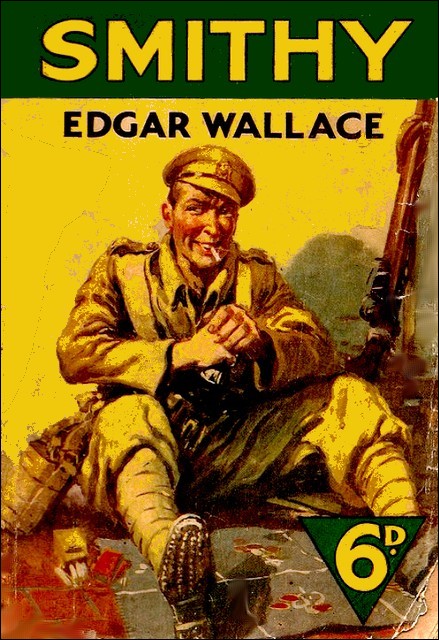

"Smithy," Sixpenny Reprint, George Newnes Ltd., London

Between 1904 and 1918 Edgar Wallace wrote a large number of mostly humorous sketches about life in the British Army relating the escapades and adventures of privates Smith (Smithy), Nobby Clark, Spud Murphy and their comrades-in-arms. A character called Smithy first appeared in articles which Wallace wrote for the Daily Mail as a war correspondent in South Africa during the Boer war. (See "Kitchener's The Bloke", "Christmas Day On The Veldt", "The Night Of The Drive", "Home Again", and "Back From The War—The Return of Smithy" in the collection Reports From The Boer War). The Smithy of these articles is presumably the prototype of the character in the later stories.

In his autobiography People Edgar Wallace describes the origin of of his first "Smithy" collection as follows: "What was in my mind... was to launch forth as a story-writer. I had written one or two short stories whilst I was in Cape Town, but they were not of any account. My best practice were my 'Smithy' articles in the Daily Mail, and the short history of the Russian Tsars (Red Pages from Tsardom, R.G.) which ran serially in the same paper. Collecting the 'Smithys', I sought for a publisher, but nobody seemed anxious to put his imprint upon my work, and in a moment of magnificent optimism I founded a little publishing business, which was called 'The Tallis Press.' It occupied one room in Temple Chambers, and from here I issued "Smithy" at 1 shilling and sold about 30,000 copies."

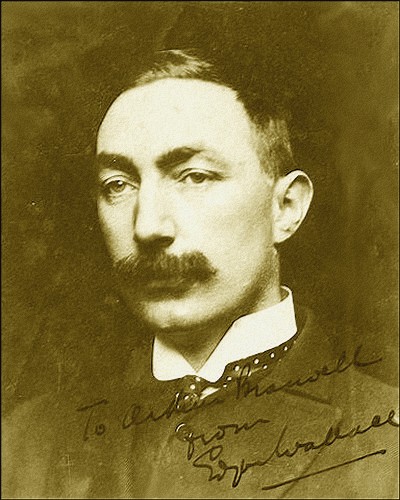

On March 24, 2015, the Oxford branch of Bonham's Auction House sold a first-edition author's presentation copy of Smithy for £400. This copy included a two-page inscription to Arthur Branwell and the following portrait photograph of the 30-year-old Edgar Wallace. —RG.

To Arthur Branwell from Edgar Wallace

"Smithy," Sixpenny Reprint, George Newnes Ltd., London

MILITARY "crime" is not crime at all, as we law-abiding citizens recognize it.

The outbreak in the Anchester Regiment was not a very serious affair; from what I can gather, it mostly took the form of breaking out of barracks after "lights out."

But, explained Smithy, it got a bit too thick, and one of the consequences was that the guard was doubled, pickets were strengthened, and the ranks of the regimental military police were, as a temporary measure, considerably augmented. I explain this for the benefit of my military readers, who may wonder how it was that both Smithy and Nobby Clark happened to be together on Number One post on the night of The Adjutant's Madness.

"I was tellin' the troops only the other night," said Smithy, "what would 'appen if they didn't give over actin' the billy goat.

"'Some of you bloomin' recruits,' I sez, 'think you're doin' somethin' very wonderful, climbin' over the wall, an' goin' into town when you ought to be in bed asleep; but it's the likes of me, an' Nobby, and 'Appy Johnson, chaps with twelve years' service, who's got to suffer. I'll bet you old Uncle Bill will start doublin' the guard to-morrer.'

"'Don't be down 'arted; Nobby sez; 'take a brighter view of life, Smithy.'

"Sure enough, next day it came out in orders that the guard was to be doubled, an' me an' Nobby was for it.

"When we mounted guard, the Adjutant, old Umferville, came over an' inspected us.

"'Who's first relief on Number One post?' 'e sez.

"'Clark an' Smith, sir,' sez the sergeant.

"'I don't want you chaps to make too much noise walkin' about, or shoutin',' sez the Adjutant, an' I'm blowed if 'is face wasn't as red as a piller-box.

"'What's the matter with Uncle Bill?' sez Nobby, as we was marchin' off.

"'I believe 'e's frightened about somethin',' I sez, puzzled.

"Number One post is between the back of the Adjutant's 'ouse and the wall where the chaps nip over. It used to be the Colonel's 'ouse; but when Uncle Bill got married a couple of years ago, the Colonel generously 'anded it over, an' took an 'ouse in town that wasn't so damp.

"It was the most excitin' guard me an' Nobby ever did, an' it was all through Uncle Bill. You never saw such goin's on in your life. 'E dodged in an' out of 'is 'ouse all day long. 'E'd start to walk across the square, then stop, as if 'e'd forgot something, then walk back to the 'ouse, then walk out again, then stop an' bite 'is nails an' stare more ghastly at nothin'.

"Once as 'e was passin', me an' Nobby shouldered arms to 'im, an' e stopped dead an' looked at us. 'E didn't move, but stood stock still for about five minutes starin' at me an' Nobby, sayin' nothin', an' me and Nobby felt quite uncomfortable.

"'Everything all right, sentry?' 'e sez at last.

"'Yes, sir,' sez me an' Nobby.

"'Sentry—' 'e sez, then stopped.

"'Which one, sir?' sez Nobby, an' the officer stared.

"'Are there two of you?' 'e sez.

"'Yes, sir,' sez me an' Nobby, an' e got very red an' muttered somethin' an' walked off.

"We was talkin' about it in the guardroom that night when we was drinkin' our guard allowance—one pint a man, accordin' to regulations. All the other chaps 'ad noticed Uncle Bill's strangeness, too.

"'It's drink,' sez Nobby, shakin' 'is 'ead. 'Wot a pity to see a pore young chap go wrong, all for the sake of the cursed liquor—after you with that pot, Smithy.'

"'You've 'ad your whack, Nobby,' I sez; 'don't come it on a pal.'

"'Did I?' sez Nobby. 'I must 'ave been thinkin' of the Adjutant.'

"'I think 'es 'aunted,' sez a chap from 'D'—a young chap.

"''Aunted!' sez Nobby, scornful. 'Why, there ain't no ghosts after Christmas, fat'ead!'

"'Never mind about Christmas,' sez the young chap; 'it's my belief 'es 'aunted, there's a spirit or somethin' follerin' 'im about.'

'Dry up,' sez Nobby, shudderin', for me an' im was on the worst relief, ten to midnight, an' four to six.

"When we mounted at 'last post' Nobby sez to me:—

"'Do you think there's anythin' in that ghost idea, Smith?'

"'No,' I sez. 'Still,' I sez, 'you never know.'

"'What's that?' sez Nobby, pointin' to a shadder movin' along the wall. So I shouts

"''Alt!—who goes there? '

"It turned out to be little Bobby Burns tryin' to break out of barracks, an' me an' Nobby captured 'im an' shoved 'im in the clink.

"Just before twelve me an' Nobby was standin' at ease, when we 'eard a most 'orrid groan. We jumps round with our 'arts in our mouths, an' there was the Adjutant in is overcoat an' slippers.

"'What the dickens are you starin' at?' 'e sez.

"'Beg pardon, sir,' stammers Nobby, 'I thought you was a ghost!'

"But the Adjutant didn't seem to 'ear what we said. 'E just walks up an' down mutterin' to hisself. Bimeby 'e sez, 'Keep a sharp look-out, an' don't make too much noise—d'ye hear, you Clark ; d'ye 'ear, you Smith?' 'e sez fiercely.

"'Yes, sir,' sez me an' Nobby; an' then the Adjutant went indoors.

"'Drink,' sez Nobby solemnly. 'Let this be a warnin' to you, Smithy.'

"When we come on duty again at four in the mornin', the two chaps we relieved looked scared out of their lives. 'I shall be bloomin' glad when its daylight,' sez one of 'em; 'we've 'ad an 'orrid time.'

"'Ow so?' sez Nobby.

"'The Adjutant's gone orf 'is napper: mad, that's wot 'e is,' sez the chap. ' 'E's bin walkin' up an' down talkin' to 'isself an' moanin' an' chuckin' 'is arms about.'

"'Nice thing, ain't it?' sez Nobby, after we was posted; 'if you ask me—why, 'ere the beggar comes again.'

"'What shall we do?' I sez.

"'Wait till 'e gets violent, then bang 'im with the butt of your rifle.'

"'You do it,' I sez.

"'No, you'd better do it, Smithy; you're the oldest soldier!'

"Up comes Umferville, and I'll take my oath there was tears in 'is eyes.

"'Sentry' 'e sez in a chokin' voice, 'challenge all persons approachin' your post.'

"'Yes, sir,' sez me an' Nobby.

"'Don't allow nobody to pass without challengin', ' 'e sez wildly, an' then run back to 'is 'ouse like mad.

"'Balmy,' sez Nobby; 'let's go an' tell the sergeant.'

"'Better wait,' I sez. So we waited.

"'The beggar 'ain't bin to bed,' sez Nobby after a bit, 'there's lights in all the rooms.'

"'I wonder what 'is missus thinks,' I sez, an' I felt sorry for Mrs. Umferville, who's a lady bred an' born.

"It wanted about an hour to daybreak when out rushes the Adjutant again an' makes straight for us.

"''Ere 'e comes,' I sez, liftin' up the butt of my rifle. 'Nobby, you're evidence that I only 'it 'im to save your life,' I sez.

"'Your life!' sez Nobby hastily.

"Up comes Umferville, sort of laughin' an' cryin'.

"'Sentry,' e sez, 'wot about your orders?'

"'Wot orders, sir?' I sez.

"'Some one's come into barracks,' 'e sez excitedly, an' you 'aven't challenged 'im.'

"''E ain't passed 'ere,' sez me an' Nobby together.

"'Yes, 'e 'as,' sez the Adjutant. 'Listen'

"We listens.

"''Ear anythin'?' sez the Adjutant.

Suddenly Nobby lets out a yell.

"'Guard, turn out,' 'e shouts, an' out come the guard with a run.

"'Wot's up?' sez the sergeant of the guard.

"'Present arms!' sez Nobby, 'to the Adjutant's new baby,' 'e sez."

"WHAT'LL be the badge for that?" asked Smithy

We were talking of the new course of military motoring that is contemplated.

"Cross' guns for marksman, cross' flags for signaller, cross' swords for instructor, cross' choppers for pioneer." mused Smithy.

"Cross pedestrians for military chauffeur," said I humorously.

"Cross corpses, if I know anything about it," said Smithy pessimistically. "Some of the chaps I know who are goin' in for motorin' I wouldn't trust with a clock-work p'rambulator."

"As you say," I began. "There—"

"Let alone motor-cars," interrupted Smithy gloomily.

"Of course there are—"

"Let alone bloomin' motor-cars," repeated Smithy, with a knowing nod of his head.

"I suppose," he went on, "you don't happen to know Spud Murphy, of 'B'—he's doin' duty now, but he used to be groom-of-the-chambers to Major What's-his-name?"

I know hundreds of Spud Murphys; but I could not recall this particular one.

"You wouldn't think," said Smithy, impressively, "that a tin-eyed rooster with four years' service, a low-down cellar-flapper from Islington that joined the Army to get away from the police, would 'ave the neck to apply for a job as shover to a choof-choof?"

"I should imagine," I remarked gently, "that the position of chauffeur requires—"

"Well," went on the indignant Smithy, "this unmentionable person did. You know Uncle Bill?"

I owned up to an acquaintance with that very kindly young officer, Captain Umfreville, of Smithy's battalion.

"Uncle Bill," said the irreverent soldier, "is one of the widest chaps in the regiment. There was a man in town who was agent for all kinds of motor-cars, but the one he was most fond of was a little thing he invented hisself. A four-'orse-power machine with bicycle wheels. He called it the 'Ravin' Jupiter,' and it was one of them run-away-and-play-whilst-papa- mends-the-carburator sort of machines.

"Well, Uncle Bill turns up in barrack one day as large as life, sittin' in a sort of bassinette and steam roller combined. He'd bought a 'Ravin' Jupiter,' and, what's more, he'd got it cheap.

"People used to larf, especially when it hurt somebody; but Uncle Bill knew a thing or two.

"A week afterwards he turned up with a ninety-'orse-power Little Nipper, or Nipper Minor, or something of the sort.

"His 'Ravin' Jupiter' had gone wrong, and while it was bein' righted the maker had lent him this car.

"I can tell you," said Smithy, with a reminiscent grin, "that old Uncle Bill didn't use that 'Ravin' Jupiter' three times a year; mostly he was cuttin' round the country in the Nipper, or a Damyer, or a Poosher, wot was lent him while the 'Ravin' ' car was gettin' a new inside.

The artfulness of Captain Umfreville caused Smithy a few minutes' amusement.

Then he returned with a scowl to the enormities of the miserable Spud Murphy.

"Spud comes to me one day an' sez, 'I'm goin' to be Bill's shover.'

"'Bill's how much?' I sez.

"'Bill's choofer,' he sez.

"'Wot do you know about motor-cars?' I sez.

"'E larfs. 'Never you mind,' e sez; 'I've driv' an ingin before now,' 'e sez.

"'Beer ingin?' I sez.

"'No,' e sez, 'a real ingin at a sawmills.'

"So Spud got his job," Smithy went on, "an' for a week he was messin' about the parade ground doin' fancy work, with Uncle Bill sittin' by his side givin' instructions.

"We used to sit outside the canteen and watch him and the officer.

"'E used to play on the thing with his 'ands and feet, and the tunes 'e got out of it was extr'ord'nary. Bill was a wonderful instructor.

"'Mark time on that blanky clutch,' he'd yell, and Spud would put his foot on the brake-pedal.

"'The other foot, you soor,' Bill'd shout, he 'avin' been in India with the other battalion.

"''Arf right!' And Spud would give the steerin'-wheel a yank to the left, an' the language of the captain was a disgrace to his company.

"I tell you Spud perspired, but he persevered, too, and used to work in little bits he learnt at the sawmill, and one day he comes up to me as pleased as Punch, an' waves a bit o' blue paper.

"'I've got me licence,' he sez.

"'O,' sez Nobby Clark—a caution, he is—'I suppose they'll let you out without a chain now,' 'e sez.

"'Don't you be funny,' sez Spud; 'I'm a licensed shover.'

"'What's that?' I sez. 'French for beer-can boy at a sawmills? '

"Well, right enough, about a week after, me and a couple of chaps was walkin' out in the country—it was a Sunday—when we 'eard a motor- car comin' up behind.

"'Hoomp ! Hoomp ! Hoomp!'

"Then, like a flash of dirty lightnin', somethin' dashed past in a cloud of dust, and there was me and the other chaps covered all over with muck, and a smell in the air like a paraffin stove.

"Bimeby," resumed Smithy, "we comes up with a motor-car pulled up at the side of a road with somebody crawlin' underneath.

"'There's only one man in the world that takes fourteen boots,' sez Nobby, 'and that's Spud Murphy;' so we pulls 'im out.

"'Now, then, you men,' sez Spud, doin' the haughty act, 'just leave me alone, will yer?'

"What's up, Spud?' I sez.

"'The off 'ind cylinder 'as come into contact with the sparkin' plug,' sez Spud, as bold as brass.

"'Sawmills,' sez Nobby Clark softly.

"'Wot are you goin' to do?' I sez, and the other chaps started lookin' underneath too.

"'I shall petrolize the trembler, and throw back the clutch into the ignition coil,' sez Spud, shuttin' 'is eyes and thinkin'.

"'Sawmills,' sez Nobby Clark quite plainly.

"Spud give him a look, then dives underneath the car with a spanner, while me an' Nobby tried to see what made the fog'orn work.

"'Oomph!'

"''Ere,' sez Spud Murphy, underneath the car, 'just you leave that 'orn alone.'

"'Oomph!'

"Spud wriggled out from under the car with a spanner in one 'and and a oilcan in the other.

"'E was red in the face, an' as wild as anything.

"'Didn't I tell you to leave it alone?' 'e sez to Nobby.

"'Sawmills!' sez Nobby; and that's why Spud 'it 'im."

Smithy heaved a sigh.

"Take my tip, don't you ever try to separate two chaps when one chap has a spanner in his 'and," he said, and continued:—

"Well, Spud lost 'is job, for a couple of red-caps* came up an' pinched 'im, an' the car 'ad to be dragged home by a fatigue party, and Uncle Bill drives his own car now; he's fed up with military shovers, and won't 'ave another."

* Military Police

"How do you know?" I asked curiously.

"I offered to drive for 'im," said Smithy modestly.

"IT's a great thing, getting a staff billet," remarked Private Smithy, resplendent in mufti of the hand-me-down pepper-and-salt variety. Smithy wore mufti consequent upon his recent appointment as groom to Major Somebody-or-Other, Deputy-Assistant-Adjutant-General (a) to Goodness- Knows-What-District.

"It's a relief to get out of regimentals," he sighed, self-consciously thrusting fingers into unaccustomed pockets. I ventured to murmur that he looked ever so much better in a scarlet coat and white belt, but Smithy demurred.

"Red tunics is all right in a way," he remarked philosophically, "but give me a smart civilian suit, turn-down collar, and a pair of brown boots for a change." At Smithy's request I "waited a bit " whilst he explored a small tobacconist's in the High Street.

He returned after a short absence, red in the face, but triumphant.

"Seven for a shilling—and an imitation crocodile leather case thrown in," he explained. "Have one?" Smithy added, with the air of a connoisseur, that it was "almost unpossible to buy a good cigar under tuppence."

Two draws convinced me that it was quite as impossible to get the genuine article at the rate of a shilling for seven.

"The red coat attracts a few, I'll admit," resumed Smithy. "I've known two silly jossers in my time who've joined the Army for the sake of the scarlet. One got his ticket three months after."

"Ticket," I may say in parenthesis, is the terse barrack-room formula for certificate of discharge.

"Colour blind, 'e was," Smithy went on, with an amused smile. "No, red coats don't bring recruits, nor," added Smithy emphatically, "nothing that the War Office ever did brings recruits." We were passing a hoarding as he spoke, and suddenly clutching my arm, he stopped dead and pointed to a placard. It was neatly printed in red and blue, and was about the size of a newspaper contents bill. It ran :

RECRUITS WANTED

FOR EVERY BRANCH OF

THE ARMY

GOD SAVE THE KING!

I nodded, and we resumed our walk.

"God save the King!" repeated Smithy flippantly. "God save the King if he don't get no more recruits than that there notice will bring him!" and Smithy laughed sarcastically.

He was silent for a while, and so occupied with his thoughts that I was able to drop my cigar down a friendly drain without observation.

"They can't get recruits nowadays," he resumed at length, and then, striking off at a tangent, "Why do fellers enlist?"

I thought it might be for the glory of a noble profession, and ventured to express this thought.

Smithy's reply was conveyed in one coarse, contemptuous word.

"Do you know why I enlisted?" he asked.

I did not hazard an opinion, and he continued: "Broke," he said tersely. "Broke to the wide, wide world; out of a job and had a row with the girl—but mostly I was out of a job.

"Show me a soldier," said Smithy, with a sort of gloomy enthusiasm, "and I'll show you a man who at some time or other has got down to his last tanner.

"Mind you," he added cautiously, "there are thousands of chaps in the Army—sergeants on the strength and all that, who've got on well and 'ave educated theirselves—they'll tell you, if you ask 'em, why they 'listed; it's because they struck pa with a roll of music and ran away from home."

Smithy ended this speech in a hoarse falsetto, presumably in imitation of some person or persons unknown.

"Why! I know a man—quartermaster-sergeant, who's got two houses of his own, and can vamp the accompaniment to any song you like. When he 'listed he walked into barracks on his uppers.

"And now he's got two houses—being a quartermaster-sergeant," added Smithy darkly, and not a little vaguely.

"And so long as the War Office is the War Office," he went on, "you'll always have an army of hard-ups. Because why?"

"Because," I submitted rather sadly, "the greater bulk of the population—"

"Not a bit," said the optimist, demolishing the results of systematic observation with a fine disregard for statistics. "Not a bit. It's because the War Office don't know what attracts soldiers.

"Why! may I be (three expurgated words) if I didn't see a bill the other day outside St. George's Barracks—it was called 'The Advantages of the Army'—and what do you think the pictures on it were about?

"One showed what a happy life a fine young feller could lead in the Royal Engineers. Picture of two pore Tommies in their shirt-sleeves carrying about a ton of wood, whilst three others was diggin' a big hole in the ground. 'Bridge-buildin' and Trenchin',' said the picture.

"Didn't you buy one of them books they was advertising so much last year?" Smithy asked abruptly.

I confessed.

"Did they send you a book showing you the advantages of buying a—what-do-you-call-it Britannia?"

I owned up to three pamphlets, eight letters, and a telegram.

"Ah !" said Smithy craftily, "and did they send you a picture showing you how you might get the brokers in if you didn't pay your instalment? No, of course they didn't. Well, this 'ere bill had six pictures. A pore slave of a lancer cleanin' his saddlery—advantages of the cavalry; a Tommy got up in marchin' order, with fifty pounds of equipment on his back—advantages of the Line ; and so on. What made 'em stop short of havin' one showin' Tommy being frog-marched to the clink," added Smithy, with gentle irony, "an' labellin' it. 'Advantages of the Canteen,' I can't imagine."

"What would attract a desirable class of recruits to the Army?" I made bold to ask.

"You'll laugh when I tell you," said Smithy very seriously. "A neat uniform for walkin' out; neat regulation boots instead of beetle crushers; a cap that ain't a pastrycook's cap.

"Make your bloomin' soldier advertise the Army make him look so as every counter-jumpin', quill-pushin' board-school boy who thinks 'es a cut above Tommy will be proud to change clothes with him. Dress him as ugly as you like for fightin'; but when he's at home, where he'll meet his pals and, likely as not, the girl he left his happy home for, give him a uniform that a civilian might envy." Smithy grew warm.

"If you want to show the advantages of the Army in pictures, give a picture of a soldier as he fancies himself best. Show his institutes; show him playin' billiards; show him in India lyin' on 'is charpoy with a bloomin' nigger servant taking orf his boots and another one pullin' a punkah. Show him in China ridin' like a lord in a ricksha; show him in his white helmet smokin' a cigar—ten for four annas—or in Gibraltar seein' a bull- fight; but don't show him in his shirt-sleeves carryin' coal!"

I was saying good-bye to Smithy when Nobby Clark of "B" Company met us.

Rude criticism of Smithy's civilian clothes was followed by a proposal that Smithy should accompany Nobby for a stroll round the town.

Smithy drew himself up.

"I hope, Private Clark," he said haughtily, "that I respect myself too highly to be seen walking about the streets with a common soldier!"

Officers commanding regiments are instructed to note among their subordinates such defects as shortness of temper or weakness of character likely to harm them in their career. —vide Army Order.

I STEPPED back quickly on to the kerb; the cab wheel that brushed against the sleeve of my coat spattered me with black mud.

The cabman threw over his shoulder the rudest expression he could summon at the moment, and I, who am a terrific linguist where the bad language of foreign countries is concerned, fired off three choice morsels of Tamil, which, had they been translated, would have brought that cabman back thirsting for my blood.

Smithy, from a place of safety on the pavement, chuckled.

"Don't lose your temper," advised my military friend—on furlough, by the way, and spending the Christmas holidays with a married sister off Portobello Road. "Puttin' down bad temper's a new Army reform." We had crossed the road in safety and were walking up Queen Victoria Street.

"Wot we want in the Army nowadays is politeness; bad language we can't abide; if we can't be good soldiers, let's be little gentlemen. The Anchester Regiment is the politest regiment goin' ; they call us the 'After you's'; our motto is, 'Quo fus et gloria ducunt,' which means, 'It's far better to be decent than glorious'; in fact—"

"In fact you're talking a lot of rot," I said irritably. Smithy smiled in a superior way.

"The other day," he went on, without taking further notice of my interruption, "we 'ad a lecture; Uncle Bill it was, the chap that 'ad the motor-car. 'Company will parade at 11 a.m. in "B" Company's barrack-room for a lecture on military manners, by Captain Umfreville.'

"We all like lectures," explained Smithy; "you can sit down to 'em, an' there's generally a fire in the room. Well, Uncle Bill starts off with a long yarn about a new Army Order, sayin' that chaps must not lose their tempers with other chaps; they ought to be polite an' kind an' courteous, an' he finishes up by sayin' he hoped he'd see an improvement in the company, that before we let our angry passions rise we ought to count twenty.

"After lecture we all goes over to the canteen; me an' Nobby Clark an' Spud Murphy an' Ugly Johnson.

All the chaps was talkin' about Uncle Bill's lecture, an' a chap of the 'G' Company says they's bin havin' a lecture too, about losin' your temper, in fact, the whole bloomin' regiment was lectured on it.

"We take it in turns to buy beer," explained Smithy; "this day it happened to be Spud's turn, but he seemed to forget it.

"'Pardon me, Spud,' sez Nobby, as polite as you please, 'talkin' about beer—'

"'I wasn't talkin' about beer, dear friend,' sez Spud, liftin' his cap.

"'Well,' sez Nobby, tryin' to smile in a friendly manner, 'suppose you talk about it—comrade?'

"Nobby nearly choked sayin 'Comrade,' owin' to his hatin' Spud Murphy worse than poison.

"So Spud shuts his eyes an' makes a noise like a chap thinkin'. 'Um—m—ah—oh, yus,' et cet'ra, whilst me an' the other chaps stood gaspin' for a drink.

"'When you've done makin' faces,' sez Nobby, gettin' red in the face, 'p'raps, gallant comrade, you'll buy some beer.'

"'It ain't my turn, dear Nobby,' sez Spud, as bold as brass.

"Nobby sort of went blue.

"'Not your turn!' 'e sez in an 'usky voice, 'not your turn—gallant soldier; not your bloomin' turn—brother?'

"'No,' sez Spud shortly; 'I bought it yesterday—comrade.'

"Nobby looks round at all the chaps who was watchin' 'im be polite to Spud, an' sez:—

"'Bought it yesterday—comrade? Why, you funny-faced perisher, it was Me wot bought it yesterday!'

"'Be polite,' sez Spud; 'don't lose your temper,' 'e sez 'or you'll be gettin. what you're askin' for,' 'e sez.

"'Wot's that?' sez Nobby, 'beer, you daylight robber, you thievin' recruit!'

"'Wot you're askin' for—comrade,' sez Spud, still tryin' to be polite, 'is a thick ear.' "

Smithy went on to a faithful recital of what Private Clark had said in response to this threat of personal violence.

For reasons purely private I suppress the lurid details.

"So at last Nobby paid for his own pint," Smithy resumed, "and sat in a comer by hisself, countin' twenty. For about a week after the barracks was like a Sunday school.

"The orderly sergeant comin' round to warn chaps for duty was like a parson givin' out notices just before the collection.

"'Is Private Jordan here?' sez the sergeant.

"'Yes, Sergeant,' sez Jerry Jordan.

"'I regret that I must warn you for picket duty to-morrow evenin'.'

"'Thank you kindly, Sergeant,' sez Jerry, who'd made arrangements to take his girl out that night.

"'Is Private Purser here?'

"'Yes, Sergeant, at your service,' sez Long Purser.

"'It's my painful duty to inform you that you must appear at company office tomorrow morning to answer the charge of not complying with an order.'

"'Don't mention it, Sergeant,' said Purser.

"One night Nobby comes to me an' sez, 'Look 'ere, Smithy, I'm about fed up with this countin' business.'

"'Are you, comrade?' I sez.

"'Not so much of the "comrade,"' sez Nobby nastily; 'I'm gettin' tired of hearin' Spud Murphy call me "ole friend" an' "chummy" an' "comrade," an' the very next time he comes snackin' me, I'll put him through the mill.'

"'Will you, dear friend?' sez I.

"'Yes, I will, fat 'ead,' sez Nobby.

"Next day, me an' Nobby bein' orderly men, we went down to the cookhouse about four o'clock to draw the tea.

"Spud's our cook; so Nobby sez to 'im:—

"'Ullo, greasy, wot's the price of drippin'?' Spud's got a second-class certificate, so rather fancies hisself.

"'Be a little more polite, Private Clark,' 'e sez in a loud voice so's the sergeant-cook could hear.

"So Nobby sez something to him.

"'Did you 'ear that!' sez Spud in an 'orrified voice.

"So Nobby sez something else to 'im.

"'Don't use that language in this clean cook'ouse.' sez Spud loudly, but the sergeant didn't take no notice. 'I'm surprised at you, Private Clark, losin' your temper like that.'

"So Nobby sez something else to 'im.

"'Say that again,' sez Spud, takin' off his coat.

"'Count twenty,' sez Nobby, with a sneer, 'like I do.'

"'Say that again,' sez Spud, so Nobby did."

Smithy paused to ruminate on that joyous memory.

"We got 'em apart at last, an' the sergeant-cook fell-in four of us to put 'em both in the guard-room.

"Next morning they was both up at company office. an' Uncle Bill sez, 'Did you count twenty, Clark? '

"'Yes, sir,' sez Nobby, 'five at a time,' 'e sez.

"'I ought to send you before the Colonel,' sez Uncle Bill, but I won't; you'll be both let orf with a caution.' "

"That was very sporting on the part of Umfreville," I remarked in some surprise.

"Yes," said Smithy, with a ghost of a smile. "Uncle Bill doesn't like takin' men before the Colonel."

"Why?" I asked.

"Him an' the Colonel ain't on speaking terms," explained Smithy naïvely.

SMITHY sprawled lazily on the grassy cliff. A gentle breeze blew in from the south, and the glassy, sunlit sea was dotted with laden transport boats.

Grazing within a radius afforded by the loose rein that Smithy held was the major's horse. In the soiled mustard-coloured garb that the soldier affects on manoeuvres, Smithy had followed both Red and Blue forces, for Major Somebody-or-other, whose serf he was, had been umpiring.

"If," said Smithy reflectively, "if we'd fought with umpires in South Africa, who do you think would have won?

"I can tell you," he went on, without waiting for an answer. "Take Ladysmith. Why, if that job had been part of manoeuvres, you'd have seen twenty little umpires come streaking up in their Panniers and Napiers and Baby Peugeots, blinding the Boers with dust, and they'd have had a conference on Wagon Hill and then they'd 've sent for George White.

"'Good mornin', Sir George,' they'd say. 'Fine weather we're havin'. 'Ow are the birds in this part of the world? My fifty-horse-power Damyer put up a dozen brace between here and Colenso,' they'd say. Then Sir George would talk about the shootin'.

"'Oh, by the way,' sez the umpire, 'wot about Ladysmith?'

"'Wot about it?' sez Sir George.

"'Well,' sez one of the umpires, polishin' his motor-goggles, 'I think you're out of action, don't you?'

"Sir George gets huffy.

"'Nothin' of the sort,' he sez; 'I can hold Ladysmith for months and months,' he sez.

"Then all the umpires larf, except one with spectacles.

"'Pardon me,' sez this one, 'you don't seem to understand that the strategic defensive calls for the preponderance of the tactical defensive—'

"'You dry up,' sez Sir George quick; 'I'm goin' to hold Ladysmith as long as we've got boots to eat.'

"But he'd have had to give way before the umpires, and Ladysmith would have gone in.

"Then," went on the great man, "take Colenso. The umpires would 'ave gone up to Botha—no, I don't know how they'd have got to him unless they went up in a balloon—and there would be me bold Botha directin' the fire of the First Loyal Sjamboks.

"'Cease fire,' shout the umpires, and Botha stares. 'Wot for?' he sez.

"You're defeated,' sez the umpire, and then goes on affably: 'What sort of a season are you havin' in this part of the world? Nice weather for the crops, By the bye, as I was comin' along in my ninety-four horse-power Wolseley, I put up twenty brace—'

"Then Botha gets mad.

"'What the howling raadzaal do you mean by sayin' that I'm defeated, when I've got a position here that I could hold for a month of Sundays?' he sez as wild as anything.

"The umpire gets very stiff.

"'I'd have you know, General, that you're not allowed to hold this position.'

"Why?' sez Botha, very astonished.

"Because it's out of bounds,' sez the umpire and so we'd have got Colenso."

Smithy stopped to watch a bare-footed sailor, with two little yellow and red hand-flags, wave erratic arms seaward.

He spelt out the message, having some knowledge of the semaphore.

"Make—your—own—arrangements," spelt Smithy, and added, with a dry laugh, "That's just the bloomin' thing the umpires don't allow for.

"I remember once," he continued, with unaccustomed animation, "when we were messing about after De Wet. You know the sort of thing—twenty miles a day in every direction. Every night we used to come up to the place where De Wet was the night before. There was half a battalion of Ours, one squadron of scallywags, two squadron of bushrangers, and a couple of pom-poms.

"Well, one day, when we wasn't exactly lookin' for De Wet, De Wet was lookin' for us, and you can bet he found us!

"Before we knew where he was he'd got our horses, and we was all lyin' flat on our chests envyin' the little ants that had as much cover as they wanted.

"We'd been shootin' away for about an hour, and it was easy to see we were pretty well surrounded.

"There was a sort of general in charge of our three columns, and he was twenty miles away with the other two.

"Bimeby we got a helio message from him—'Make the best arrangements you can; I can't get to you under six hours.' So our old man, and the scallywag captain—Somebody's Horse it was—an' the Australian major, had a sort of council of war underneath a water-barrel.

"'Well, gentlemen,' sez our old man, 'I'm afraid we're pipped,' he sez; 'rightly speakin',' he sez, 'we ought to shove up the white flag,' he sez; but I give everybody fair warnin',' he sez, 'that I'll shoot the man who as much as blows his nose with a white handkerchief,' he sez, with a wicked laugh.

"And the scallywag and the bushranger and the little gunner who had just crawled up, said, 'Hear, hear!'

"Then our old man goes on: 'The main body of the enemy is in a donga three hundred yards to our left,' he sez, 'and we've got to get that donga,' sez our old man."

Smithy's eyes were far away.

"Bimeby," he went on, "I heard the old man shouting, 'Concentrate your fire on that donga,' he sez ; then after a bit, when the dust begins to go up, he yells, 'Fix bayonets!' "

Smithy turned and looked me squarely in the face. "What would the umpire have said?" he asked. Why, we'd have been bloomin' well decimated—but we wasn't. The Boers didn't wait for the bayonet—they pushed off, and we got away with the guns.

"There's only one kind of war," said Smithy sagely, "and that's the kind that hurts. When the chap that's playin' the real game makes a misdeal or revokes, there's no reshuffle. If he puts up a big bluff and it comes off, he's a great man, and gets his picture in the papers. If it don't come off, why—"

Smithy's silence was eloquent.

"Umpires in war," he went on, "are food and feet and fingers—fingers for holdin' on to positions where, rightly, you should 'a' been kicked off.

"I know regiments that could never be put out action unless every man was killed—what's an umpire goin' to do with a lot like that?" he demanded. Somewhere down on the shingly beach below to a stentorian voice roared:

"Smith!"

Smith rose with alacrity.

"Comin', sir," he shouted. Then, as he led his officer's charger seaward, he turned.

"He's an umpire," he said, with a jerk of his thumb toward the beach, "but he's a very decent chap otherwise."

"IT was read out in reg'mental orders," said Smithy, "on the 9.30 parade, that a new lot of books 'ad arrived for the lib'ry. 'Suitable books for the Soldier,' it said, so that afternoon me an' Nobby goes over to the coffee-shop where the lib'ry is to 'ave a look. There was lots of other chaps there, an' we 'ad to take our turn.

"All the chaps was shoutin', 'Come on, Mac, give me that red one,' an' poor old Macmanus got 'isself all tied up in a knot tryin' to put dawn the names of the chaps that took out the new books. When it come to me an' Nobby's turn there was only two books left. Nobby got a blue one an' I got a red one.

"'Wot's yours, Smithy?' sez Nobby, an' I read it out: 'Temp'rance Statistics of the Army in India.'

"'Who Stat What's-'is-name?' sez Nobby.

"'Some bloomin' teetotaller,' I sez. 'Wot's yours?'

"'Ydraulics for Garrison Artillery,' 'e sez. 'Whose she, I wonder?'

"Spud Murphy got a book about 'Tactics in the Crimea,' George Botter (of 'G') got a yaller book about 'Afghanistan in Relation to the Frontier Question,' Mouldy Thompson got a big book about 'The 'Istory of the Army Service Corps,' whilst old 'Appy Johnson got the best of the lot, 'Records an' Nicknames of the British Army.'

"We all takes our books to the barrack-room, an' there was me an' Nobby an' all the rest of the chaps sittin' down 'oldin' our 'eads tryin' to understand what the books was about.

"When we gets over to the canteen that night everybody was tryin' to show off.

"Spud comes strollin' up to where me an' Nobby was sittin'.

"'Ullo, Nob,' 'e sez.

"'Ullo!' sez Nobby; 'what do you want, funny face?'

"Spud sits down alongside of me an' Nobby.

"'Talkin' about the Crimea—' 'e sez, like a chap sayin' a piece.

"'I wasn't talkin' about the Crimea,' sez Nobby.

"'Ave" you ever noticed that a great strategic opportunity was lost—'

"Nobby puts down the can 'e was drinkin' out of.

"''Old 'ard,' 'e sez. I think I grasp your meanin', Spud. You're referrin', unless I am mistaken, to the time when the garrison artillery didn't start workin' their 'ydraulics in a proper manner.'

"'No, I ain't,' snaps Spud. I'm talkin' about the tactics in the Crimea.'

"'An' I'm talkin' about 'ydraulics,' sez Nobby, as calm as a cucumber, 'becos that's the book that I'm a-readin'.'

"It was pretty sickenin'," explained Smithy, "wot with George Botter tryin' to pretend 'e knew all about Afghanistan, an' 'Appy Johnson wantin' to make bets about who was the first colonel of the Anchesters. Mouldy Thompson got to 'igh words with a driver of the A.S.C. about the Army Service Corps.

"'I suppose you don't know, Cocky,' sez Mouldy to this chap, 'that the old A.S.C. used to be called the Muck Train?'

"'No, I don't,' sez the A.S.C. chap nastily, 'an' wot's more, I don't see no call to go makin' personal remarks.'

"'Where no offence is meant, it is 'oped that no offence will be took,' sez Mouldy. 'Well, as I was sayin', the Muck Train—'

"'Shut up,' sez the A.S.C. chap, 'or 'I'll shut you up.'

"Just before 'fust post' me an' Nobby was sittin' in the corner talkin' about 'ydraulics and drink, when in come Gus Ward of the R.A.M.C.

"Up goes Mouldy to 'im as pleased as anything.

"'D'you know what they call the Medical Staff?' sez Mouldy.

"The medical bloke looks over 'is pot an' sez nothin'."

"They call 'em the "Linseed Lancers,"' sez Mouldy, laughin'.

"The medical finished 'is beer, puts down 'is pot, and sez to Mouldy:

"'Do you know what I call you?' 'e sez.

"'Don't be naaty,' sez Mouldy; 'this is in a book.

"'In a book, is it?' sez the medical. 'Well, you homoeopathic, subcutaneous mnemonic, what I'm going to call you won't be found in any book.'

"So then the medical chap started callin' Mouldy all the things 'e could remember at the minute, an' finished up with a few words out of the sick report.

"You must understand," explained Smithy, "that all the bloomin' battalion was on the same lay. There they was the next afternoon lyin' in their cots a readin' an' a mutterin' an' gettin' ready to show off.

"Wastin' their time"—Smithy was indignan—"an' well knowin' that we 'aven't got a decent bowler in the regiment. I didn't see anything of Nobby till I went over to the canteen that night. Everybody was talkin' about everything—all talkin' together. Suddenly I 'eard Nobby's voice:

"'No, you're wrong, Mouldy,' 'e sez; 'you're wrong about the artillery.'

"'Wrong!' sez Mouldy, very indignant; ''ow do you know?'

"'Because I do,' sez Nobby, 'an' what's more, Spud Murphy's wrong about the army in the Crimea, an' George Botter's talkin' through 'is 'at about Afghanistan, an' Dusty Miller's silly when 'e sez that Athens is in Germany (Dusty got a book on the decay of the classy or somethin' of the sort), an' when Billy Mason gits up an' talks about Africa—I've got a word to say.'

"An' with that old Nobby starts to criticise everybody, not confinin' hisself to 'ydraulics, you understand, but goin' all over the shop.

"Bimeby, old Spud Murphy, who'd been dazed by Nobby tellin' 'im a lot about the battle of Alma, strikes 'is for'ead an' shouts:

"'Old 'ard, Nobby—I see your little game—it's A's what your talkin' about.'

"'What d'ye mean?' sez Nobby, goin' red.

"'Why,' sez Spud, excited, 'you're talkin' about Abukir an' Abyssinia an' adjutants an' ants—they're all A's,' roars Spud.

"'Well,' sez Nobby, 'wot about it?'

"'Ask 'im a C question, somebody,' shouts Spud, gleeful.

"'Wot about crocodiles?' sez Dusty.

"Crocodiles an' alligators are all the same,' sez Nobby. 'Everybody knows that.'

"''Ear, 'ear,' I sez; an' the other chaps said the same.

"'Well,' sez Spud, thinkin', 'I'll give you a "M"—wot about monkeys?'

"Nobby thought a bit.

"'Apes,' 'e begins, 'was first invented—' 'Monkeys!' sez Spud.

"'Apes an' monkeys are all the same,' sez Nobby.

"'Well, tell us somethin' about Colonels—that's a C,' sez Spud, who was gettin' wild.

"It took Nobby a long time to think this out, then 'e starts:

"'Adjutants was first invented—'

"'I thought so,' sez Spud, joyful. 'P'raps you'll tell me when 'Cyclopaedias was invented—fortnightly 'cyclopedias, wot you buy for sevenpence,' sez Spud.

"An' Nobby looked quite uncomfortable."

"YOU don't 'appen to know our Bertie, do you?" asked Private Smith; "'E's a new chap only just joined from the depot: 'ighly educated an' all that: one of the struck-pa-with-a-roll-of-music-and-enlisted sort of fellows."

Smithy paused to ruminate upon the accomplished Bertie.

"I've 'eard 'im use words that wasn't in any dictionary," Smithy continued with enthusiasm, "an' 'e's settled arguments we've 'ad in the canteen without so much as lookin' in a book.

"There was a bit of a friendly discussion the other night about 'ow much alch'ol there was in beer, an' 'ow many pints it'd take to poison a chap. Gus Ward, the medical staff chap, worked it all out on a bit of paper, but some of the other chaps said 'e was talkin' through 'is 'at.

"To settle it—none of the other chaps would come outside when Gussie invited 'em—we sent over for Bertie.

"Over comes Bertie with a wot-can-I-do-for-you-my-poor-child sort of smile, an' we puts the question to 'im.

"'Twenty-two gallons an' a pint,' sez Bertie prompt.

"'You're a liar!' sez Nobby, an' the medical chap asked Bertie to come outside an' settle the question.

"'Don't be absurd,' sez Bertie. 'Nobody can tell me anything about alch'ol: it was discovered by a monk in 1320, when 'e was searchin' for the philosopher's stone. It is known at Lloyd's as a deadly sporadic an—'

"'Shut up,' sez Nobby; 'we don't want to know the geography an' 'istory of it, we want to know 'ow many pints of beer it takes to kill a chap.'

"'Thirty-one gallons an' two pints, as said before,' sez Bertie, huffily; 'an' in future, Private Clark, I don't want you to send for me to settle canteen controversialities.'

"'Wot's that last word?' sez Nobby, after Bertie had gone. 'Somethin' insultin', I'll lay.'

BERTIE'S ALMA MATER

"Me an' Nobby 'appened to be over at the coffee shop next night—it was the night before pay day, or we wouldn't 'ave been wastin' our time—when in comes Bertie.

"'E's got an 'orrid languid way of lookin' round, an' it was a minute or two before 'e spots me an' Nob.

"'Ullo, Clark,' 'e sez, with a nod just the same as if 'e was an officer. 'Ullo, Smithy.'

"'Ullo, face,' sez Nobby, who's always got a kind word for every one.

"'I'm gettin' tired of this sort of life,' sez Bertie, in a weary voice. 'I've got too much wot the French call savoir faire.'

"'See a doctor,' sez Nobby, 'or take plenty of exercise, like I do.'

"'You misunderstand me, Clark,' sez Bertie, with a sad smile. 'But, there, 'ow should you know, my poor feller?'

"'Bertie,' sez Nobby.

"'What?' sez Bertie.

"'Don't call me a "pore feller,"' sez Nobby, 'or I'll give you a dig in the eye.'

"'Don't lose your temper, Clark,' sez Bertie, hasty. 'What I meant to say was, you can't be expected to comprehend 'ow it feels for a chap who's drove 'is own brougham to be ordered about by cads of officers, cads an' bounders that my alma mater wouldn't 'ave in 'er set.'

"'Who's she?' sez. Nobby.

"'My rich aunt,' sez Bertie.

"'Livin' in the Marylebone Road?' sez Nobby.

"'No,' sez Bertie, carelessly: 'Porchester Gate.'

"'Ah,' sez Nobby, thoughtful, 'that's a work'ouse that must 'ave been built quite lately—'ow London grows, to be sure.'

"Bertie smiled an' shook 'is 'ead.

"'Ah, Clark!' 'e sez with a pityin' look, 'there's a good old French sayin' that goes, "Ontry noo sivvoo play," which means, "Don't argue with a fool.'

"'There's another good ole French proverb, sez Nobby, 'that sez, "Chuprao soor."'

"'What does that mean?' sez Bertie surprised, so Nobby told 'im.

THE BUN-WALLAH

"Bertie wasn't what you might call popular with the troops. For one thing 'e used long words that nobody even 'eard before, an' for the other, 'e was a bun-wallah of the worst kind."

(It is, I might say, one of the wilful fallacies of the Army that teetotallers live entirely on lemonade and buns.)

"We don't mind so much a chap bein' a teetotaller; every man to 'is taste, an' I've known some very good chaps in that line, but Bertie used to carry 'is fads a bit too far.

"For instance, 'e got me an' Nobby one night down to an A.T.A. (Army Temperance Association) meetin', an' so worked on Nobby's feelin's, by promisin' to lend him 'arf a crown till pay day, that Nobby ups an' signs the pledge.

"'I feel a diff'rent man already,' sez Nobby, after Bertie 'ad parted with the money, 'I do, indeed.'

"'Ah,' sez Bertie, proudly, 'you'll feel better when you've 'ad a week of it. Don't let your boon companions lure you back to the old 'abit,' 'e sez.

"'No fear,' sez Nobby, putting the 'arf-crown in 'is pocket.

"'Not so much of the boon companions, Bertie,' I sez, knowin' what 'e was eayin' was a smack for me.

"'When: they offer you the pot—refuse it like a man,' sez Bertie, working hisself up to a great state.

"'I will,' sez Nobby.

"'Look 'ere,' sez Bertie, excitedly, 'come up to the canteen now, an' put yourself to the test.'

"'Right you are,' sez Nobby, quick; 'let's 'urry up before it's shut.'

"So we all went up to the canteen, an' the first thing that 'appened when we got inside was Dusty Miller offerin' Nobby 'arf a gallon can. "'Drink 'arty, Nobby,' sez Dusty.

"Nobby looks at the can, then looks at Bertie, an' Bertie was smilin' 'appily all over 'is face."

"'No,' sez Nobby, chokin', 'no, Dusty, you mean well, but I'm on the tack—on the lemonade tack,' 'e sez. 'Good Nobby,' sez Bertie.

"'Let me take one last look at the cursed stuff,' sez Nobby, takin' the pot in 'is 'and; 'one last sniff,' 'e sez, 'one last taste o' the poison,' 'e sez, an' before we knew what 'ad 'appened 'e'd 'arf emptied the can.

"'It's no good, Bertie,' 'e sez sadly, 'the temptation is too strong, it's in me blood,' 'e sez. 'You can 'ave your 'arf-crown back on pay day."

"What chaps didn't like about Bertie most was the way 'e was always goin' on about 'is come-down in the world, 'ow e might have been livin' up in the West End, goin' to theatres every night of 'is life, an' drinkin' port wine with 'is meals, if 'e 'adn't been such a fool as to enlist.

"One night when 'e was' playin' billiards in the library Nobby got Bertie to settle a point whether an earl was an 'igher rank than a countess,

"'A countess, of course,' sez Bertie.

"'For why?' sez Nobby.

"Bertie gave a pityin' sort of laugh.

"'A countess is a lady count, an' a count is next to a marquis,' 'e see.

"'Ow do you know?' sez Nobby.

"Bertie gave a sort of a tired sigh, an' looked at the ceilin'.

"'My dear Clark,' 'e sez, 'it ain't for me to boast of the people I met before I come down in the world, but I might say I've met certain parties—no names mentioned—that our officers ain't even on speakin' terms with.'

"'In shops?' sez Nobby.

"'No, in country 'ouses,' sez Bertie stiffly.

"'Leave off pullin' Bertie's leg,' sez Spud Murphy, who always likes to get a rise out of Nobby. 'Anybody can see Bertie's mixed with 'igh-class people.'

"We was all silent for a bit, watchin' Dusty Miller, who was playin' Mouldy Turner a hundred up, tackle an' 'ard-lines cannon.

"We was very interested in it, epecially Bertie, who, couldn't take 'is eyes from the cloth.

"Dusty fluked 'is cannon an' missed the next shot, an' then Nobby got a sort of inspiration, an' calls out to. Bertie:

"'Call the game, marker!'

"'Seventy-six plays forty-two: spot to play, sir,' sez Bertie, absent- mindedly.

"I DIDN'T see you at our piece," remarked Smithy.

"I mean," he explained, "the Grand Amateur Performance of The Soldier's Revenge, played by the Regimental Dramatic Club, on behalf of the new wing of the Anchester Lunatic Asylum." Smithy stopped to clear the stem of his pipe with a hairpin. I regarded him suspiciously—and the hairpin with inward misgivings.

"There was about two dozen of our chaps in the piece," he resumed, "and the band was goin' to play durin' the intervals. Some of 'em—our chaps, I mean, not the band—was goin' to be soldiers, some of 'em was servants, some of 'em was villagers, but half of 'em was 'rioters' in the last act. "'B' Company and 'F' tossed up to see who'd be rioters and 'B' won, so 'F' had to be policemen.

"Nobby Clark comes to me the day before the performance an' sez, 'Look here, Smithy, come an' act.'

"'The goat?' I sez.

"'No,' he sez, 'come an' be Mike Dolan, the Escaped Convict, in Act IV.,' he sez; 'Fatty can't get into the clothes,' he sez.

"'No, thanks,' I sez. 'If you want Escaped Convicts, apply to "C" Company —there's lots of chaps there that would do it natural,' I sez.

"'Don't you be gay,' sez Nobby, 'or else you'll strain your funny bone. I'm goin' to be a gentleman visitor in Act II.—one of the 'ouse party.'

"'One of the gentlemen that washes up the plates?' I sez.

"'Loud larfter,' sez Nobby, sarcastically. 'I'm goin' to be a good shepherd in the last act,' he sez, 'an' when the rioters are goin' to bash the police I say, "'Old! what would you do, rash men?" an' then I tell 'em to think about their wives an' children,' he sez. "It was pretty sickenin' them last two days in barracks before the performance. There was Jimmy Spender walkin' about holdin' his head an' mutterin'; 'My lord, my lord, the enemy is on us; fly for your life!' an' Smiler Williams walkin' up an' down the square after 'lights out' talkin' to hisself, 'Come, comrades, let us drink to the 'ealth of our noble commander,' till Smiler's company officer, Captain Darby, gave him seven days for creatin' a disturbance in barracks after lights out. Ugly Johnson broke his collar-bone when he was rehearsin' his rescue from a burnin' buildin'.

"A lot of chaps was supposed to catch him in a blanket as he jumped out of a winder, sayin', 'A British soldier fears nothin'; but the chaps who was holdin' the blanket larfed so much at Ugly's mug, that they hadn't the strength to catch him." Smithy laughed, too, at the recollection.

"Well, the night come, an', havin' bought two seats in the gallery, I goes round to the house where Nobby's girl lives an' asked her to come an' see the play.

"'Nobby won't like my goin' out with you,' sez Nobby's girl.

"'Don't worry about that,' I sez; 'he'd have sent you a ticket hisself, only he's so shy,' I sez. So she put on her things," said Smithy, vaguely, "and went."

"We got two front seats where we could see everything, an' after the band gave a selection and the officers an' their ladies, an' the Bishop, an' the Mayor had come in, the curtain went up, an' there was Nobby strollin' about with a gun under his arm, pretendin' to be an actor. "Bimeby the old squire come in with his lovely daughter. 'Ah, Captain Beecher,' she sez to Nobby—she was a real actress, too—'why, it seems like old times to see you at "Silverton Grange."

"'Bai Jove!' sez Nobby, twistin' his moustache like he'd seen his superiors do. 'Bai Jove,' he sez, an' then he forgot what to say. "'The pleasure is mutual,' sez a holler voice from behind the, scenes.

"'The pleasure is beautiful,' sez poor Nobby, still twistin' his moustache.

"After a bit the old squire was murdered by Monty Warne, of 'H,' dressed up like a burglar, an' he did it well, too," commended Smithy, "stranglin' him so much that they had to send out for three-pennorth of brandy to bring him round.

"In the second act Nobby was supposed to be a visitor in evenin' dress.

"'Don't he look fine?' sez Nobby's girl.

"Nobby didn't have much to say in that act, except when young Fisher, who's got a baker's shop in the Highstreet, was falsely accused of murder, an' then Nobby seized his hand, an' said, 'I believe you to be an innocent man,' an' we all said, 'Hear, hear.'

"It was really Smiler Williams who ought've said that line, as Nobby was really supposed to be a villain, an' Smiler an' Nobby had words about it afterwards, till Nobby explained that young Fisher had promised him a job when he left the Army, an' he wanted to keep in with him.

"But the last scene was best," continued Smithy, "when the hungry rioters of 'B' come face to face with the policemen of 'F,' an' Nobby comes down to the footlights dressed up as a parson, and says, 'Hold!' "Just as he started to say his little piece one of the policemen, tryin' to be funny, hit him in the chest with a truncheon.

"'Hold hard,' sez Nobby, forgettin' all about the piece; 'wot are you tryin' to do, Corky?'—speakin' to Corky Speddings, who hit him.

"'Go on with the piece,' sez Corky, who was wild because had had nothin' to say in the play.

"Nobby took orf his parson's hat an' raised it an' said, 'Hold! What would you do, rash—' then another policeman threw a bit of bread at him. "Before anybody know what was happenin', Nobby dropped his hat an' landed the nearest policeman on the nose, an' then there was the most realistic riot that has ever been on a stage.

"Next mornin' Nobby asked me what I thought of his performance.

"'Fine,' I sez.

"'Do you think so?' he sez, very pleased, 'Don't you wish you could act, Smithy, an' take the part of a young lord or something?'

"'I can act,' I sez. 'I was actin' last night—The Absent Soldier.'

"'Talk sense,' sez Nobby, puzzled; 'you hadn't got a part.'

"'Oh yes I had,' I sez.

"'What part?' sez Nobby.

"'Your part,' I sez.

"But Nobby didn't understand."

"DO you believe in ghosts?" asked Private Smithy.

"What kind of ghosts?" I asked cautiously.

"There's a chap in H Company," explained Smithy—"his name's Turner, Mouldy Turner, we call him, owin' to his havin' been a moulder by trade. You never saw such a chap in your life," said Smithy enthusiastically. "Give him a pack o' cards an' a table an' he'll tell you things about your past life wot you've never heard before.

"He charges tuppence a time, an' it's worth it. I had twopenn'orth myself the other day.

"'Smithy,' he sez, dealin' out the cards all over the table, you're expectin' a letter from a dark man.'

"'No, I ain't,' I sez.

"'Well, you'll get it, he sez. 'It will bring good news.'

"An' sure enough," said Smithy, impassively, "that very afternoon Spud Murphy paid me two shillin's he borrered on the manoeuvres."

"But," I expostulated, "that wasn't a letter."

"It was better than a letter," said the satisfied Smithy.

"Well, old Mouldy counts the cards, seven to the left an' seven to the right.

"'There's a fair woman wot loves you,' sez Mouldy.

"'How fair?,' I sez, thinkin' of all the red-haired gals I know.

"'Pretty fair,' sez Mouldy, 'you're goin' on a long journey acrorse the sea.'

WHAT NOBBY SAW

"'Battersea?' sez Nobby, who was lookin on.

"'You shut up, Nobby,' I sez, 'go on, Mouldy.'

"'The nine o' spades,' sez Mouldy, scowlin' like anything at Nobby, 'is a sign of death. You'll hear of a friend dyin'. Not much ot a friend, either, but a ignorant chap with big feet,' he sez.

"'You leave my feet alone,' sez Nobby.

"All the chaps used to come to Mouldy, an' he was doin' well. I could see Nobby didn't like the way Mouldy was rakin' in the iron, an' one night, when me an' a few chaps was in the canteen torkin' about how teetotallers die when they get into a hot climate, Pug Williams came dashin' in, lookin' as white as a ghost.

"'Nobby Clark's took ill!' he sez, an' we rushes over to the barrack-room to find old Nobby sittin' on his bed with a horrible stare in his eye.

"'Wot's up, Nobby?' I sez, and just then Mouldy Turner comes in.

"'I see,' sez Nobby, in a moany sort of voice, 'I see a public house.'

"'You've seen too many public houses,' sez Mouldy, hastily.

"'The inside of a public house, sez Nobby.

"'That's the part I mean,' sez Mouldy.

"'I see a man with side whiskers an' a big watch-chain,' sez Nobby moanily; 'he's servin' be'ind the counter, an' there's a red-faced gel with yeller hair a-countin' money. Her name's Gertie,' sez Nobby, holding his for'ead. "Old Mouldy's jaw dropped an' he went white.

"'Where's my George? Where's my soldier boy?' moans Nobby, 'that's what she's a-sayin' of.'

"Mouldy's face got red.

"'Boys,' sez Mouldy, in a scared voice, 'old Nobby's got second-sight; he's a seein' the pub I go to up in London an' my young lady.'

"'Where's my brave soldier?' sez Nobby, groanin'; 'that's what she's a- sayin' of; where is my brave soldier wot rescued the colonel at Paardeberg?'

"'He's a wnnderin' now,' sez Mouldy, blushin'.

"'Let's take him to the, hospital,' sez Pug Williams, but just at that minuto Nobby sort of woke up.

"'Where am I?' he sez faintly.

"We told him what he'd been sayin', an' tried to persuade him to go to bed an' sleep it off.

"The next day the news got about that Nobby was second-sighted, an' when me and Nobby went to got our dinner pint all the chaps crowded round an' asked him to give a performance.

"It appeared from what Nobby told 'em that he'd always been second- sighted, an' when he was a kid he had to wear spectacles.

FORTUNES

"'Can you tell fortunes, Nobby?' sez Oatsey.

"'I can with hands, sez Nobby, lookin' at Mouldy; 'not with cards. Cards,' he sez, 'is swindlin'.'

"Can you tell mine, Nobby?' sez Pug Williams, holdin' out hid hand.

"'Certainly,' sez Nobby, who'd known Pug all his life, an' went to school with him.

"'You was born under an unlucky star,' sez Nobby, lookin' at the hand.

"'That's quite right,' sez Pug, qhite proud.

"'At School you was always gettin' into trouble,' sez Nobby, who happened to know that Pug did six months at a truant school.

"'That's right!' sez Pug, highly delighted.

"'You've had a lot a trouble through a dark man,' sez Nobby, knowin' that Pug got forty-two days for knockin' a nigger about, when the reg'ment was in India.

"'Marvellous!' sez Pug.

"From that day Nobby made money. Chaps used to come from every company to get their fortune told. Mouldy an' his cards did no bus'ness at all.

"Nobby charged thruppence a hand, cash on the nail; fourpence if he 'ad to wait till pay day.

"For sixpence Nobby used to have a fit an' see things. Sometimes two chaps would club together, an' then Nobby would have two fits for ninepence.

"One day up comes Ugly Johnson, of 'D.'

"'I want you to tell my fortune, Nobby,' he sez.

"'Cross me hand with silver, pretty lady,' sez Nobby.

"'Don't snack a chap about his face,' sez Ugly, very fierce.

"'No offence, Ugly,' sez Nobby.

"'And I ain't go'in' to cioss your bloomin' hand with silver,' sez Ugly, ''cos I've only got three'apence.'

"'That'll do, sez Nobby, who never let a customer go.

"'You've got a long life in front of you,' sez Nobby, lookin' at the hands.

"'Ah,' sez Ugly.

"'You've 'ad a stormy career in the past,' sez Nobby, 'but all will come right!'

"'Ah,' sez Ugly.

"'You've been crorsed in love,' sez Nobby.

"'That's a lie,' sez Ugly.

"'So it is,' sez Nobby, lookin' close at Ugly's paw, 'wot I thought was the crorsed-in-love line is only dirt. You've got a sensitive 'art, you think everybody's passin' remarks about your face,' sez Nobby.

SPIRITS

"'Never mind about my face,' snarls Ugly.

"'I don't mind it,' sez Nobby, 'even if other people do,' he sez.

"Well, old Ugly got mad an' went round puttin' it about that Nobby couldn't tell fortunes for nuts, and Mouldy sez that Nobby was tellin' a lot of lies an' makin' fun of the chaps, an' business began to fall orf.

"One afternoon Nobby sez to me, 'Smithy, trade's bad.'

"'Is it?' I sez.

"'Yes,' he sez, 'it's about time I had another fit.'

"'Have it now,' I sez, 'don't mind me.'

"That night, when we was all cleanin' up for commondin' officer's parade, an' the barrack-room was full, Nobby suddenly stood up, moanin' like anything.

"'I see!' he sez starin' about him, 'a man with a ugly mug. 'E's a- standing' on the blink—I mean brink of destruction.'

"We all walks over an' looks at Nobby. He was a ghastly sight, rollin' his eyes an' moanin'.

"'I see a chap,' sez Nobby, twistin' about as if he'd swollered a corkscrew, 'wot pretends to tell fortunes by cards. 'E's standin' on the brink of destruction too.'

"'Wake up, Nobby,' I sez, soothin' him; 'it's all right.'

"'I see,' began Nobby again, an' just at that minute in walks the colour-sergeant.

"He looks at Nobby rollin' an' squirmin' about, an' then sez to me:

"'Are you the oldest soldier here, Smith?'

"'Yes, colour-sergeant,' I sez.

"'Well,' sez the colour bloke, 'take a couple of men an' put Private Clark in the guardroom.'

"'Wot for?' sez Nobby, wakin' up sudden from his trance.

"'Drunk,' sez the colour-sargeant.

"'I ain't drunk,' roars Nobby, very indignant.

"'Pretendin' to be drunk, then,' sez the colour-sergeant; 'that's worse.'

"'I'm seein' spirits,' sez Nobby.

"'You've, been drinkin' 'em,' sez the colour bloke, an' Nobby was so wild that it took six of us to get him to the guairdroom.

"You might say seven," added Smithy, "for Old Mouldy did the work of two men."

Young and growing soldiers are prone to wear boots that are too small and too narrow mainly because of their smart appearance. —Army Council Memorandum to Officers.

"I SHOULDN'T like to be on the Army Council," said Smithy, with all seriousness.

I looked at my young military friend with feigned surprise.

"No, I ain't coddin'," he said earnestly. "I s'pose it's a good job; but never 'avin' been an officer, I can't say what it's like. But stands to reason it's a wearin' sort of life.

"Suppose the Army Council's meetin' to-day, the orderly on duty lights a fire, gets out new pens and blottin' paper, an' Army Form B47, just the same as if it was a court-martial—and," said Smithy, as a brilliant idea came to him— "it is a court-martial, and the Army's the prisoner.

"Well, in comes the Court, all in civilian clothes, Lyttelton in a soft felt 'at, an' Plumer in a red necktie, and Douglas got up to the nines.

"'Wot's on to-day?' sez Lyttelton.

"Reformin' the Army,' sez all the others together.

"'Rot,' sez Lyttelton. 'I don't believe the Army wants reformin'—except reformin' back to the place it was when civilians started holdin' post-mortems on it.'

"''Ear, 'ear,' sez all the Army Council, except Lord Don't-Know-Who, who looked embarrassed, 'e bein' a civilian.

"Wot about tight boots?' sez Some One after a long pause, durin' which the Financial Secretary was doin' sums on the blottin' paper an' crossin' 'em out when 'e found they was wrong.

"'Ah,' sez Some One Else, 'wot about tight boots?' So they all sits round givin' their opinions why soldiers should be Ugly and Comfortable.

"Well, after a bit they make up an order:—

"No lady-killin' boots allowed. Soldiers in possession of boots weighin' eight ounces will immediately exchange them for boots of the Regulation (or Policeman) Pattern, weighin' four pound. 'Fiat experimentum in corpore vili,' or 'If necessary make the experiment on a villainous corporal.'

"Yours truly,

"THE ARMY COUNCIL."

"Then they all get up an' stretch their legs.

"'What's on to-morrer?' sez one.

"'Army Reform,' sez the President; 'an' let's see you all 'ere at nine, sharp.'

"Then they all go home to their little flats, an' read the newspapers, an' wish they was Japanese sittin' tight in front of Kuropatkin instead of bein' soldiers tryin' to reform the Army so as to suit civilians' ideas.

"Sometimes it's boots, sometimes it's swearin', sometimes it's 'air—an' the 'smart, soldier-like appearance' order: this new order about boots, though, rather takes it."

Smithy's "It" is fairly obvious.

"They was talkin' about it in the canteen yesterday, when me an' Nobby went over to get our dinner beer.

"Wilkie—that red-lookin' chap with the shavin'-brush moustache—was puttin' it about that the order was only meant for 'B' Company.

"'Don't none of you chaps get worried about it,' sez Wilkie, who's an 'H' chap. 'This 'ere order's only meant for chaps with big feet tryin' to pretend they're Cinderellas.'

"'Meanin' me, Wilkie?' sez Nobby.

"'No names, no pack drill,' sez Wilkie.

"'Meanin' me, you red-'aired Bloomsbury scavenger?' sez Nobby.

"'If the cap—meanin' to say the boot—fits you, Private Clark, lace it up,' sez Wilkie; 'an', what's more.' 'e sez, 'don't forget the last Army order about swearin' an' losing your temper.'

"Next day," continued Smithy, "was commandin' officers' parade, an' when the company officers walked round the ranks there was trouble.

."'Where's your boots?' sez the captain to young Skipper Mainland.

"'Under my trousers,' sez Skipper.

"'Too small,' sez the officer; 'put this man down for a new pair, colour-sergeant.'

"'What's these, Clark?' sez the officer.

"'My feet, sir,' sez Nobby, gettin' red in the face.

"Beg pardon,' sez the officer, I thought they was a pontoon section,' 'e sez and we all laughed.

"I tell you," said Smithy enthusiastically, "our officer's a comic chap.

"That night you couldn't get into the 'Igh Street for feet. All the chaps was wearin' their biggest boots, an' one chap standin' on the kerb got 'is toes run over by a tramcar the other side of the street—in a manner of speaking," corrected Smithy hastily.

"'Oo should we meet when me an' Nobby was strollin' down Church Lane but Wilkie. Nice toonic, smart tight trousers with officers' stripes in 'em, saucy little boots, an' a cane with a silver knob on the end of it—that's Wilkie.

"'Hullo, Wilkie,' sez Nobby, 'wot Christmas-tree did you blow orf of?'

"Wilkie looked a bit pleased with hisself, an' was goin' to say somethin', when up comes the Provost Sergeant with 'is badge on 'is sleeve.

"'Evenin', Sergeant,' sez Wilkie very pleasant.

"But the Provost Sergeant didn't say nothin', only looked at Wilkie's feet

"'Nice weather for this time of the year,' sez Wilkie. 'It is indeed,' e sez.

"But Provost Sergeant only stared at Wilkie's feet.

"So Wilkie got red in the face.

"'Beg pardon, sergeant,' e sez; 'nothing wrong, I 'ope?'

"The Provost just kept on lookin'. Then 'e said, speakin' slowly, like a chap recitin':

"'The proper fittin' of boots on which the marchin' of an army depends is a matter of the first importance,' 'e sez.

"Wilkie looks at 'im; so did me an' Nobby.

"'I don't do no marchin' in these boots,' sez Wilkie, an' my boots an' Nobby's sort of shuffled into the gutter out of sight.

"'Young soldiers,' sez the Provost Sergeant, takin' no notice of what Wilkie said, are prone—'

"'Are what?' sez Wilkie.

"'Are prone to take a boot too short—in fact,' sez the Provost Sergeant, 'where did you get them ridiculous lady's shoes from, Mr. Bloomin' Wilkie? '

"' I got 'em,' sez Wilkie, from—.

"'No man who wasn't a lunatic would wear such fal-lal; they was meant for women, not soldiers.'

"'I got 'em—' sez Wilkie.

"'Makin' yourself a laughin'-stock,' sez the Provost, gettin' wild, 'wearin' boots that nobody but a fat-headed, dandified, ijiotic recruit would think of disgracin' 'is foot by puttin' inside.'

"'I got 'em off the Colonel's groom,' sez Wilkie, short.

"'Where'd 'e get 'em?' sez the Provost.

"'They're a pair of the Colonel's old 'uns,' sez Wilkie, what 'e got rid of—they was too big,' e sez."

POLITICS form no part of the barrack-room debating society. Mr. Atkins lives in a world of his own, and is not interested in the subjects that agitate his civilian brother.

He is interested in personalities, certainly, and Mr. Chamberlain and Lord Rosebery are very real persons to him; but talk about the respective merits of Free Trade and Protection and he will yawn. Very high politics, politics that make for war; parliamentary proceedings that have direct bearing upon pay, promotion, and uniform, are of the first importance; and does an hon. member ask the Secretary of State for War whether his attention has been called to the refusal of the proprietor of the "Green Man" to supply two soldiers in uniform with liquid refreshment, that hon. member may be certain that he will achieve a popularity out of all proportion to the service he has rendered the Army.

High politics include, of course, the Russo-Japanese War. As to the cause of that unhappy conflict no opinion is offered, since that is a matter which does not greatly concern the soldier; but the conduct of the campaign has won unstinted admiration for the plucky little Easterners.

I learnt this much from Smithy (we were watching an Army Cup match), and I learnt also that the popularity of a foreign Power may easily be exploited with profit.

"We 'ad a long talk about it the other night down in our room. Dusty Miller—him with the crooked nose—said that the Japs was winnin' because they'd got a better rifle than the Russians. Jimmy Walters said it was because the officers was more friendly with the men than what ours was.

"'All you chaps are talkin' through your 'eads,' sez Nobby; 'it ain't rifles, it ain't guns, and it ain't officers.'

"'You know a fat lot,' Spud Murphy stuck in, 'If it ain't none of them, what is it?'

"'Jue Jitsoo,' sez Nobby, with a cough.

"'Who's she, Nobby?' I sez, an' all the other chaps said the same.

"Jue Jitsoo,' sez Nobby slowly, 'is a sort of thing that you hit a chap without touchin' him, in a manner of speakin'.'

"'Talk sense, Nobby,' sez Spud, 'an',' he sez, 'don't try to talk about things you don't know nothin' about.'

"'I'll show you what I mean,' sez Nobby, gettin' up from 'is cot. 'I read about it in a book I bought—come 'ere, Dusty.'

"'What for?' sez Dusty, shrinkin' back.

"'I want to show you 'ow it's done,' sez Nobby, takin' orf 'is coat an' rolling up 'is sleeves.

"'Show Smithy,' sez Dusty.

"'Show Spud,' I sez, very hasty.

"Spud didn't like the idea, but Nobby said it was all right.

"'If you 'urt me,' sez Spud, threatenin', 'it's me an' you for it, Nobby.'

"'Don't cry,' sez Nobby, takin' 'old of Spud's arm an' then started to explain.

"'Suppose you're a thief,' e sez.

"'No snacks,' sez Spud.

"'Suppose you come up to me on pay-night an' try to pick my pocket.'

"'You ain't ever got anything on a pay-night,' sez Spud, with a larf.

"'Well,' went on Nobby, not takin' any notice of Spud, 'I just ketch 'old of you like this—an' that—an' there you are.'

"An' before Spud knew what was happenin' there he was, on the floor—whack!

"'Don't you do that again,' sez Spud, gettin' up.

"'Now,' sez Nobby, gettin' Spud by the throat, 'suppose you're a dangerous criminal an' I'm a policeman—'

"'Leggo,' sez Spud, strugglin'.

"'I just push you in the face, kick your leg, butt you with my 'ead—and there you are!' An' down went Spud on 'is back—bang!

"'Look 'ere,' sez Spud—he never could take a joke—'look 'ere,' he sez, 'don't you try your funny tricks on me, Nobby, or—'

"'What's the good of gettin' out of temper,' sez Nobby, an' we all said the same, so did a lot of chaps who'd come up from the room downstairs when they 'eard Spud fall. So we told him it was for the good of the reg'ment, an' we was all learnin' Ju-What's-its-name, an' we said no one else was strong enough to be, experimented on, an' so we calmed him down, an' he said he'd go on bein' an experiment.

"'Suppose I'm a robber,' sez Nobby, 'an' try to pinch your watch. Now what you've got to do is to catch 'old of my throat an' 'arf strangle me.'

"'I can do that,' sez Spud, brightenin' up.

"'An' what I've got to do is to prevent you,' sez Nobby. 'Now here I come, pretendin' to lift your watch.'

"It was as good as a pantomime to watch Spud waitin' to land one on Nobby when 'e got close enough; but somehow when Spud jumped forward to choke Nobby, Nobby wasn't there, an' down went Spud all in a 'eap.

"'E got up, feelin' 'is legs to see if they was broke, an' Shiner Williams, who happened only to arrive at that minute, asked Nobby to do it again, because he wasn't lookin' at the time.

"'That's what you call Ju-jitsoo, is it?' sez Spud.

"'Yes,' sez Nobby, puttin' on 'is coat, 'that's why the Japs always win, an' the Russians always lose.'

"'That's Ju-jitsoo, is it!' sez Spud, takin' orf 'is coat.

"'That's it, Spud,' sez Nobby. 'I 'ope it'll be a lesson to you—I don't charge you anything for learnin' you—but I'm willin' to give lessons at fourpence a time to any young military gentleman present. Who'll 'ave four-penn'oth?'

"'That's Ju-jitsoo, is it ' sez Spud, in a sort of dream; an' that 'e makes a rush, an' knocks poor old Nobby over an' sits on him.

"'What's the Ju-jitsoo for this, Nobby?' sez Spud, givin' him a punch.

"'Lemme get up,' sez Nobby.

"'Suppose you're a big-footed liar of a soldier what gets flattened out an' sat on for bein' too comic—what do you do next?' sez Spud, givin' Nobby a smack on the 'ead.

"'I haven't read that part yet,' gasps Nobby 'Let me get up an' 'ave a dekko at the book.'

"'Let 'im get up, Spud,' I sez.

"'Hullo, Smithy,' sez Spud, 'what are you stickin' your ugly nose in for?'

"'Never mind my nose,' I sez ; 'let Nobby get up, or I'll give you a wipe in the eye,' I sez.

"'I see,' sez Spud. 'Ju-jitsoo means always havin' a fat-'eaded pal handy to take your part,' he sez"

"THE officer," said Private Smithy, of the 1st Anchesters, "is a new officer. It isn't the new kind of uniform, or the new Salvation Army cap, or the new silly way of wearing his shoulder sash. He's a changed officer, if you understand. He don't look no different, and in many ways he's not altered a bit. He still plays polo an' bridge—what's bridge?"

I explained.

"Well, he still does all these things just about as much as ever he did, but I tell you 'e's an astounding blighter in many ways."

"It ain't so long ago," reflected this monument of the First Army Corps, "when officers used to come on parade at 10 a.m.—commanding officers' parade drill order—and we used to look at 'em hard to discover whether we'd seen 'em before. They used to troop down from the officers' mess buttoning up their brown gloves and hooking on their swords under their patrol jackets. They'd stand about for a minute or two yawnin' their blankey 'eads orf an' then the bugled sound 'Officers come and be blowed,' an' they'd fall in.

"Well, the colour-sergeant was always waitin' for 'em.

"'What's on this mornin',' says me fine captain.

"'Battalion drill, sir,' says the flag.

"'Oh, dash battalion drill,' sez the captain, walkin' round an' inspectin' the company. Take this man's name, colour-sergeant, for wearing his pouoh on the right side.'

"'Beg pardon, sir,' sez the flag, 'they're wore on the right side.'

"'So they are,' sez the intelligent captain, givin' a casual glance along the line. 'Well, take his name for 'aving a dirty belt.'

"'Right, sir,' sez the colour-sergeant.

DRILL—OLD STYLE

"When the inspection was over the officer would draw his sword and read the writin' on it, and draw noughts and crosses with it on the ground; then fall in six paces ahead of the centre of his company. Bimeby he'd see something 'appening to the company ahead of his.

"What's gain' on there, "colour-sergeant'?' he'd ask.

"'Formin' fours, sir, sez the colour-sergeant.

"'Oh, I forgot all about, that, sez his nibs. 'Company! Form fours!' an' not a man moves

"'You 'aven't numbered 'em, sir,' sez the colour-sergeant.

"'Hey?' sez the captain, gettin' red. 'Then why the dickens ain't they numbered when they fall in? Number off from the right, an' be quick about it.'