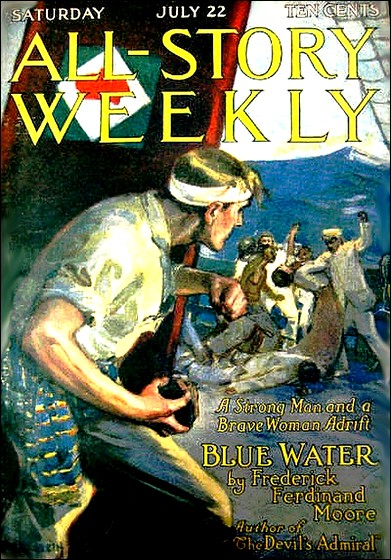

All Story Weekly with "The Devil Light"

Some men have an aversion to cats, others shrink back in horror from a third floor window and fight desperately to overcome the temptation to throw themselves into the street below. For others the mirror holds a devil who leers a man on to self-destruction. But for Hans Richter that cruel and puzzling light which he interpreted into E Flat held all that there was of threat and fear.

If you say that the obsession of little Hans savoured of madness, tell me something of yourself. Squeak a knife-edge along a plate, or knife-edge against knife-edge and watch the people shudder and grimace. They also are mad of the same madness. Some men and women grow frantic at the rustle of silk; others may not pass their palms over certain surfaces (such as plush or velvet) without a shivering fit. Exactly why, nobody knows.

There are undreamt of horrors in commonplace objects for some of us—Hans Richter had the advantage of hating and fearing that which was not commonplace.

He played second violin at the Hippoleum. He had little spare time with a daily matinée and a twelve o'clock rehearsal every Monday, but he utilized that spare time with great profit, being a most earnest student of colour values, and, moreover, a worshipper of heroes.

You had no doubt as to what manner of heroes qualified for his adoration. Nature had built him short and clumsy, with a pink, round face and blue eyes. She had built him cheap as a builder runs up a cottage out of the material left over from a more pretentious job.

'Well buttressed, but poorly thatched,' he described himself, and indeed the great Dame had been mean in the matter of head-covering, for his hair, sandy and fine, was in a quantity less than was necessary. His moustaches were mere wisps, but in the shape to which he trained them you read his mind, his faith and his pride.

He was a gentle soul, with strange and unusual views on lights, and a certain pride in his intimate knowledge of London. It was his boast that there was not a street in the metropolitan area which he had not visited, not a historic monument upon which he could not enlarge at length; and once on a more than ordinarily poisonous night of fog he had led Sam Burns by the hand from Holborn Town-Hall to Paddington Station, and never bungled a single crossing, never so much as mistook the entrance of a blind alley, though the fog was so thick that Sam could neither see his guide nor the pavement under his feet.

Oh, no, he was no spy—he hated the Prussian, as so many Bavarians did before the war (he was from Nurnberg). He was German all through, but neither favoured bureaucracy nor militarism.

They lived together, this curious pair, in a tiny house off Church Street, Paddington—in a neighbourhood of strange smells and of Sunday morning markets. Sam Burns was 'Mr Burns' in law, and entitled (did they but know it) to the respectful salute of policemen, for he was a naval gunner on the reserve of officers, and held the King's warrant.

They had one quality in common—that they were simple men — and because of this No 43 Bebchurch Street was a haven of peace.

For Sam directed such casual help as he could secure in his best quarter-deck manner, had a gift for spying out untidy corners and hurried scrubbings, a vigilance which earned for him the hatred and slander of the charladies of Paddington, and resulted in a constant melancholy procession of new servants.

They sat together by an open window on a Sunday evening in June 1914, taking the air. Sam's lean red face was one great scowl, for he was reading a thrilling murder case—facial contortion was part of the process of his reading.

'Murder's a curious thing,' he said at last, setting the paper down on his knee. 'I've killed men in my time—natives and that sort of thing—but always in what I might term the heat of battle. I wonder how it feels?'

Hans turned his mild face to the other and stared through his gold-rimmed glasses.

'Herr Gott!' he said. 'That you should talk about such subjects, Sam—who could think of murder on such a night? It is a night for thought—exalted thought!'

He stopped suddenly, pursing his lips and looking thoughtfully out of the open window, and upward to the patch of western sky which showed above the mean housetops.

'G minor,' he said abstractedly, and Sam grinned.

'You're mad on lights, Hans!" he chuckled. 'G minor!—what the dickens is G minor?'

Without turning his head or relinquishing his gaze the musician whistled a soft sweet note sustained, and full of sorrow.

Sam frowned.

'I'm beginning to see,' he admitted, 'yes—that's the kind of light it is. You're a crank on lights, Hans—'

The other swung round in his chair and reached for his violin and bow that lay on the table near him. He drew the bow across the muted strings and a gloomy stream of thick sound filled the little room.

'Purple,' he said, and played another long note—a joyous blatant note of arrogant triumph.

'Scarlet,' he smiled, and put the instrument back.

'Lights are horrible or beautiful—terrifying or adorable — listen.'

He seized the instrument again and sent the bow rasping across the strings.

'For God's sake don't make that infernal noise!' growled Sam shifting uneasily, for the note shrill and menacing carried terror in its volume.

Hans had the instrument on his knees. His lids were narrowed, his plump jaw outthrust.

'That is white light—the devil's light—cruel and searching. It stares and shrieks at me. There is a beckoning devil in that light. You see it on the stage—I have seen it a hundred times. It strips young girls of their modesty, it reveals the lie, it mocks the passé. You can see them staring at it—blinded and yet staring, their white teeth glittering, their red lips smiling like children smile when they are in pain—it is the light of war, and cruelty and suffering—phew!'

He flung the violin away and mopped his damp forehead with a big green handkerchief.

Sam rose from his window chair slowly.

'Hans, you're a fool,' he said, 'and I'm going to put a B major match to the A flat lamp.'

Hans laughed and rose too with the remark:

'And I'm going to a ten o'clock rehearsal—the show opens to- morrow—Gott! It is a quarter to ten already!'

It was not a happy rehearsal for the little German. There was a new American producer at the Hippoleum, a burly man in a grey sweater, who was quick to wrath, and had a wealth of unpleasant language.

In the third scene the lights went wrong. Four specially erected electric projectors had been fixed in the gallery, and on a certain chord, at the end of a song number, they had to concentrate upon the principal, who was singing. And they just didn't. One wandered off to the second entrance. One wavered undecidedly too far up stage, and the other two did not appear at all.

'Say, what's the matter with you?' exploded the producer. 'Are you crazy up there? Is this a joke?'

He said other sarcastic things, and said them through a megaphone, which somehow made them worse.

A hollow and apologetic voice answered from the deserted gallery.

'Put all your lines down—now put 'em on the proscenium arch—now put 'em all together up stage—now put 'em on the bald-headed fiddler in the orchestra—'

There was a gentle titter of laughter from the weary chorus—but it was short-lived.

The bald-headed fiddler was standing up facing the light, his face distorted with rage, his wild eyes glaring like a trapped animal, as his clawing hands flung out at the light.

A torrent of words, German and English, poured from his twisted mouth.

'Take it off! Take it off! Take it off!' he screamed.

There was an instant and a painful pause. The lights dimmed and an outraged producer strode down the central aisle of the theatre and confronted the second violin.

'For the lord's sake!' he said, mildly enough, 'have you gone mad, mister?'

The little man, one trembling hand curved about the orchestra rail, shook his head. He was very white, and the American, a judge of men, and kindly enough out of business hours, dropped his big hand on the other's shoulder.

'You go right along home and have a sleep, son,' he said gently; 'don't you worry—go right along home.'

'It's the light, sir,' faltered Hans, and blinked fearfully up at the gallery. I do not like the light—'

'Sure!' soothed the other; 'now you go right away and have a rest — there's nothin' comin' to you, son—on the square. I get just crazy like that myself.'

Hans did not lose his job—he played second fiddle on the opening night of that brilliant success, There You Are, Bunny! and would have gone on playing through the inevitable run but for certain great happenings in Europe. A prince of an Imperial house was killed, and when the message came to six chancelleries six separate and distinct ministers demanded of their war offices, 'How soon can you mobilize?'

Hans did not know this, but later he was to have misgivings.

'I must go home,' he said doggedly. 'I am too old to be of any use — but who knows?'

He looked wistfully at the red-faced Mr Burns, who sprawled across the table gloating over a newspaper chart which showed the relative proportions of the world's fleets.

Sam looked up.

'They'll want me,' he said with quiet satisfaction. 'My old captain will hoist his flag—he's vice admiral now—and he promised me that if ever there was a kick-up he'd take me. Who made the Penelope the best gunnery ship in the home fleet? Me, Hans!'

He thumped his thick chest and his eyes were puckered with proud laughter.

'I'm not too old for sea-going, but if I am there are lots of jobs for a man who ain't too old to spot a damned—'

He stopped in confusion. The eyes of Hans were set and the dominant expression in those eyes was envy.

'Gott!' he said with a sigh, 'I am no good—I hate war — it is terrible to think about—it is like the white light, a devil! But I must go back. Perhaps I may take the place of one—if He wants me!'

He left the next day—an exhilarating day for Mr Burns, for he had received a notification that 'my lords of the Admiralty' had accepted his offer of service.

Hans, with his brown ulster and his aged violin, came, packed his cheap gripsack and two brown paper parcels, paid his share of the expenses which were current, and went off in a taxicab.

'Good-by, Sam.'

'Good-by, Hans—good luck!'

The little man's grief was undisguised.

'I shall think of you—as a soft golden light, Sam,' he choked.

'That's right,' replied his less imaginative friend, 'yellow for me, Hans.'

Poor old Hans! So thought Mr Gunner Burns with a sigh...anyway, they weren't likely to meet. The little musician would scarcely be found amongst the ships' companies which the marksmanship of Gunner Burns foredoomed to destruction.

So passed Hans, and as for Sam, after a spell at Whale Island teaching the young and impetuous naval marksman how to shoot, he came back to Somewhere in England to more important duties.

There was a noise like the roll of a trap drum—an even 'br-r-r-r' of sound.

Gunner Burns standing in the darkness, dropped his head sideways and listened.

It was faint at first, but grew louder with every second that passed, and the noise came from the air.

Sam peered over the parapet in a swift, keen scrutiny of the sector south of the position. Somewhere beyond the inky belt of darkness which blotted out the nearest features of the landscape was London—London the vast and wealthy, a gigantic, flat hive buzzing and droning, unconscious of the danger.

As the watcher looked he pressed the electric button which was fixed to the wall near his hand, and almost instantly a second figure joined him.

The trap drum noise was now loud and angry, and the men craned their necks and searched the skies through their night glasses.

'There she is, sir!' said Sam in a low voice, 'the biggest they've got ... '

The officer at his side had his glasses on the lean shape that blotted no more than two or three stars at a time.

'What's her range?' he asked with the regret in his voice of one who anticipates an answer which will dash his hopes.

'Three or four thousand yards—shall I light her up?'

The other's hands had closed on the telephone receiver in the little recess beneath the parapet.

' 'Lo—that you, Shepherds Bush? Zep coming over, I'm going to light her up—no, only one as far as I can see. She'll start circling in a minute, looking for the small-arms factory as usual...Right!'

He turned to the man at his side with a grunted order. Something hissed and spluttered. Little bubbles of light outlined a big barrel shape somewhere in the rear of where he stood, and there leaped into the air a solid white beam of dazzling light which moved restlessly from side to side till it settled on something which looked for all the world like a silver cigar.

'She's just beyond range—but give her one for herself, Burns,' said the young officer. 'She's turning!'

The deafening crash of a gun woke the still night—a drift of smoke passed between the observer and his objective. As it cleared a tiny point of vivid light flicked and faded beneath the big silver cigar.

'Five hundred yards short,' was the bitter comment.

'She'll take some hitting! Keep the light on her—Shepherds Bush will pick her up in a minute...'

WHOOM!

The shock and pulsation of the explosion came to them. The trees rustled as though they had been stirred by a gust of wind, and the concrete parapet under the officer's hands trembled and shook again.

The old gunner at his side drew a sharp breath.

'Addlestone—that is!' he said. 'Fancy Addlestone! Good God, it doesn't seem real, does it? Why, when I was a kid I went to school at Addlestone...'

Another report followed, fainter than the first, and then over toward Addlestone came a red glow in the sky, a glow which gathered in brightness until it was almost golden.

'Them thermite bombs are pretty useful,' said the gunner with reluctant admiration. 'Hot! You can't get near a fire that's been started by one of them. I've seen men and women roasted to death by 'em, and they never knew what killed 'em. There's Shepherds Bush, sir!'

From the south two white beams had shot into the air and focused instantly on the fast moving cigar. She turned to the westward, and the lights followed. She moved in one majestic sweep to the east—but the lights did not leave her. They were the two great eyes of the dark world staring their wrath at the night bird.

'She wants that cloud dam' badly,' said the young naval officer. 'Put your light over the cloud—yes, it's big enough.'

He took up the telephone.

' 'Lo, Shepherds Bush...She's going for the cloud on the left. She's about level—no, I can't keep her lit up for much longer—she's getting beyond my range.'

The sky shape was now blurred and indistinct, for it had reached the misty edges of the cloud—in ten seconds it had disappeared. But now flashed into the air not two but a dozen searching eyes. They grew from the dark void beyond the hillcrest to the south, slender white spokes of light that criss-crossed incessantly. The cloud glowed yellow where the beam came to a dead end, and once it sparkled at a dozen points, For all the world, as Gunner Burns said, as if some one were striking a match along its under surface and had done no more than raise a shower of sparks.

'Shrapnel,' said the old authority approvingly; 'that'll rattle her a bit. Nothing like a nearby shell burst to make you take your eyes from the compass—there she is!'

Out she came from the same cloud-wall into which she had dived — into the gleam and glare of the searchlights. Left and right, beneath and at the side of her the light splashes came and went. They were as soft and as sudden as the glow the fireflies make.

The great machine turned again, her nose rose slowly into the air and her tail went down. The watchers could see the cloud of oily smoke at the stern as her speed increased.

'She's got to climb for it, and climb quick,' said the gunner.

A quick fan of light leapt up from the ground over by Golders Green.

WHOOM!

'A keepsake,' said the lieutenant grimly.

The telephone bell tinkled and an urgent voice demanded his immediate attention.

'She's going back to you, Carter—keep your light on her. She's twelve thousand seven hundred feet up and rising—shoot her off or she'll give you hell!'

'Ay, ay, sir!' the officer swung round. 'Light her up!'

Again the searchlight stabbed the dark, and again the cigar floated in a halo of soft radiance.

Then from the north came a new sound. It was not the 'br-r-r-r' they had heard before, but a purring note—a far-off motorcycle could reproduce the gentle din.

High above, the merest midgets in the vast space of starlit sky, three specks of earth-dust moved slowly across the field of the watchers' vision, and as they moved, in the limitless dome of the heavens a red ball of light lived and died. The young officer sought the telephone.

'Three aeroplanes up—they have signalled "shut down searchlights,"' he called breathlessly.

Two seconds passed, and then, as though one hand controlled the light shafts that swept the skies, they vanished.

They waited in the dark. The never-ceasing roar of the Zeppelin engines neither increased nor grew fainter. She was cruising laterally for some reason—the Golders Green telephone explained.

'We've hit her, sir—first or second compartment. Think one of her fore tractor screws is out of action...Yes, she got near us, but now she's drifting your way.'

'Her fourth visit,' said Sam.

'And every time she's gone straight to the place she wanted to reach,' added the officer with an impatient and wondering little 'ch'k' of his tongue. 'That fellow must know London like a book—he must know it blind to pick out his target with all the lights shaded and faked.'

Sam nodded and thought of a certain Hans Richter.

Poor old Hans! Fancy making Hans the focus of ten three-thousand candle-power searchlights! Sam grinned in the darkness.

Three...four...five minutes passed, then from the sky shot a thin beam of light that seemed from the viewpoint of the gun position to be aimed horizontally from the airship.

'Got her blinders on,' commented Sam. 'Aeroplanes are up to her level—there they are! Right ahead of her! They can do nothing with the light in their faces. She'll climb if she ain't climbing already.'

Another minute passed. Then a speck of red fire appeared in the black heavens, another red followed and then a green.

'Aeroplanes coming down—she's blinded 'em,' he said rapidly. 'Stand by to light her up—keep 'em off the aeroplanes...Now!'

From every point of the horizon the beams sprang until the sky was a thick jungle of converging light stalks. They beat fiercely, remorselessly, upon the big cigar as she zigzagged her way to safety and the north-west.

A thousand feet above the guns the landing lights of an aeroplane burnt blue, and the great bird swooped to earth. They ran out to him as the guns of Golders Green began a frantic bombardment of the disappearing Zeppelin.

It was Burns who helped the pilot to alight, and the boy who jumped to the ground was shaking from head to foot.

'Did you see it...did you see it?' he croaked. 'It was awful!'

They got him to the shelter of the position and to the little room behind. The airman was pinched and blue of face, but it was not his cold ride which had set him a tremble. He drank the cup of hot coffee they gave him, and as he did so his teeth were chattering against the edge of the mug.

'Awful!' he said at last; 'did you see it?'

'The Zep?'

He shook his head impatiently.

'No—after we gave the signal for the light, and they all came up—we were under the angle, and I looked up and suddenly a man—' he shivered and closed his eyes, 'a man leaped and straight out of the fore cabin...leaped and turned over and over...'

In the morning they made a search and found, in the big Mill Pond by Addlestone one who had in his lifetime been Hans Richter—the man who knew London and hated lights. Especially lights that could be translated into E flat.