THERE is a certain Belgian village where in pre-war days the aristocracy of Belgium sojourned during the hot months of the summer. “Village” comes into the same category of mock-modest terms as “cottage” when it applies to the millionaire’s residence. It lies in a fold of hills amid scenery of exceptional beauty. If any peasants ever lived in this “village,” they had long since departed. The chateaux were in the possession of Illustrious Members of the Great General Staff. The tents of their escorts, guards and servants sprinkled the hillside. Lines of motor-cars were parked in the pleasant little Place before the very modern Gothic Hotel de Ville, where a band played to a select and limited audience on three evenings a week.

One morning a special train came to the station and a certain person in naval uniform alighted and was received with a guard of honor, and welcomed by innumerable military gentlemen with long shining swords and stiff back-bones.

Within two hours of his arrival five machines of the Umpty-fourth Squadron, carrying a necessarily limited supply of bombs rose from the aerodrome and made a bee-line for this pleasant village. They crossed the first and second barrages without mishap, reached the open country and, disdaining such invitations as loaded troop-trains afforded, they pushed their way steadily to the happy valley, fought down the patrols which guarded the approaches to their objective and passing in single file immediately above a certain chateau, they left that once handsome house a haggard and blazing ruin.

It was an interesting journey for Tam and Billy Best, who formed the crew of one machine, but the real interest began on the journey back, a circumstance which Tam had to some extent anticipated, for the last half of the journey northeastward had been across a country which was only revealed in patches.

Billy Best shouted down the speaking-tube: “We’ve got three bombs left. Shall I drop ’em on a train?”

Tam shook his head vigorously. “Ma engine’s knocking,” roared his voice, “and there’s a fog gathering—it would be no’ discreet to annoy the inhabitants.”

The engine trouble was developing. He had lost sight of his companions in the mist and the ground was now hidden from sight. He consulted his map, his watch and his compass. Somewhere beneath him was a big straggling forest westward of which was a plain clear of fences and ditches and sunk roads, where a landing might be effected without much damage.

He was some eighty miles behind the active front and if he could make a good landing in the fog there was at least a chance that he could put the engine right, for Tam was before all things a skilled mechanic.

He brought his machine lower and lower, searching for the tree-tops, and presently he sighted what he knew were the outliers of the forest. Allowing himself a margin to clear the solitary trees which were a feature for a mile west of the forest, he planed down and made a good landing on a perfectly smooth patch of meadow-land which had been reclaimed from the arid plateau.

The fog grew thicker, but this did not distress him. He had a rough idea where he had landed and the density of the mist would enable him to finish his work without fear of interruption.

The two went to work to strip that part of the engine which was affected and for an hour they toiled incessantly. It was not the first landing which Tam had made in enemy country and to some degree it was not the worst. Their biggest danger was that his engines had been heard, but against this he put the fact that he had shut them off more than a mile from the place where he landed. His work finished, he set out to make a reconnaissance. Fastening the end of a big ball of string to the undercarriage of the machine, and taking another ball in his pocket, he paid out the string. He moved off in the direction he judged the road would lie.

He had finished the first ball, had fastened it and was starting on the second when he heard the sound of horses hoofs within a dozen yards of him. He crouched down and listened. His knowledge of German was not particularly good, but from certain words, and especially the repetition of a certain illustrious name, he gathered that the raid had been more or less successful.

The horses passed and the rumble of the wagon they drew rolled away in the mist before he continued his progress through the fog. He reached the road, took his bearings and compared it with his map, tied a knot in the string so that he might judge the distance, and leaving the end on the ground he advanced cautiously down the road. The fog blotted out everything, but he had no difficulty in keeping to the paved causeway.

Presently a building loomed ahead. It was a squat cottage which was apparently used as an estaminet. The door was fastened, the windows were shuttered. Tam consulted his map again. An estaminet was marked west- southwest of the forest. This must be it. It looked deserted and yet he had an uncanny feeling that it was occupied.

He made a careful examination of the premises. Behind the cottage was a walled yard pierced by a door which had been left open. He slipped his automatic pistol from his pocket and stepped in. Access to the house from the yard was gained by a small door. He tried it and to his surprise it opened. He hesitated. His natural curiosity urged him forward, his as natural caution and the knowledge that there was nothing to be gained by continuing what was an idle search and a great deal to be lost if the house should be in the occupation of German soldiers or a German post, as it probably was, held him back.

The fog would not lift for some time and it was necessary that he should know something more about the ground than he did know. There were two roads from the forest, one to the north and one to the south, which ran nearly parallel, and he was not certain which of the roads he was on. If he was on the northern road, then his machine was faced with a deep belt of scrub which might make an attempt to rise not only difficult but dangerous. If it was the southern road, as the estaminet on his map seemed to indicate, it was plain sailing.

This might or might not be Le Coq d’Or. It was up to him to make sure.

He pushed the door open and stepped in with a light tread. He was in a room which was undoubtedly the outer room of an estaminet. There was nothing in the advertisements on the walls that gave him any information. He stepped across the room to a second door, turned the handle gently and opened it. Apparently it was untenanted. The only light -came from the back window which was half covered by a blanket.

Tam took-a little electric lamp from his pocket—you need such things in clouds—and flashed it around the room. He took one glance, then stepped back quickly.

“Come oot of that,” he said sharply, “come oot quick or I’ll shoot.”

There was a shuffle of feet and a man stepped slowly into the circle of light which the electric torch threw.

To describe him as a scarecrow would be to overstate the attractions of a scarecrow. His clothes were rags, his bare knees showed grimly through the rents in his trousers, his hands were indistinguishable in hue from the rusty blue jacket. His chest was bare, for in place of a shirt he had a strip of what was once white sheeting wound in cummerbund fashion about his waist. Hut it was the man’s face that left Tam speechless, his face and his head. His hair and beard were iron-gray, but one-half of his head had been shaved and one-half of his beard, the reverse half to that of the shaven portion of his head, had been clipped off.

He peered forward at Tam. “English?” he said hoarsely.

“Scots,” said Tam.

“Thank Gawd. I thought you was one of them Germans.”

Between “them” and “Germans” was a long string of unnecessary but pardonable words, singularly vivid and sanguine.

“You’re English, I gather,” said Tam. “Who else is here?”

“I’m on my own, sir,” said the man.

“Tell me, is this the Coq d’Or?”

“Right you are, sir,” said the nondescript stranger; “used to be kept by a Belgium till three days ago. They took him out and shot him. He’s buried on the other side of the road.”

“Come along wi’ me,” said Tam and led the way back along the road, until he came to where the ball of string lay. By its aid he guided himself back to the airplane.

“Speak softly,” said Tam. “Who arc ye and what are ye doing here?”

“Gee,” said Billy, staring at the amazing spectacle, “what’s this?”

The man grinned. “I ain’t very pretty, am I, sir? Name of Henry Burton, Port of London, able seaman of the Wapping Queen.”

“But for the Lord’s sake,” said Tam, “what did ye cut yer hair like that for?”

The eyes of Henry Burton hardened. “They did it,” he jerked his head eastward; “that’s the sort of thing they do to a seaman. A U-boat off Ireland, sir. Because we defended ourselves with our nine-pounder, they tried us, me and the skipper and another feller, the only men left alive after the poor Wapping Queen went down. Said we had no right to shoot at a war- ship—not after she’d torpedoed ours.”

Tam had heard of this barbarous treatment of sailor prisoners. “How did you come here?” he asked.

“I escaped, sir. I’ve been six weeks getting across Germany, walking by night and sleeping by day. I got to this place and the Belgium hid me in the cellar. He was very good to escaped prisoners, that’s why they shot him. Found him giving food to a French soldier that had got away. They didn’t think to search the cellar or they’d have got me, too.”

Tam looked at Billy and Billy looked at Tam.

“Weel?” said Tam.

“We can’t leave him here,” said Billy. “He can take the observer’s seat in the cockpit. I’ll sit behind you.”

Mr. Henry Burton turned his startled gaze on the two.

“What! me, sir,” he gasped, “go up in an airyplane? Not me, sir. A ship I understand, and land, but the air I don’t understand and don’t hold with.”

“Mon, ye’re mad,” said Tam.

“Not so mad that I’ll go gallivanting about in the air.” said Mr. Burton; “no, I’ll be all right, sir. You leave me alone. Give me a bit of grub, if you’ve got any, and I’ll find my way to Holland.”

“Ye’ll find yeer way back to prison,” said Tam. “You do as ye’re told, my mon. Get up into the seat and try it. ‘Tis a bonny place and as safe as the Glasgow Limited.”

“I don’t hold with Glasgow nor anybody that sails from that port,” said the obstinate Mr. Burton, “with all due respect to you, sir, though from your talk I should say you were Irish.”

Tam argued with the man fiercely, but he was adamant.

“See here,” said Billy, approaching the pathetic figure, “I give you my word that you’ll be safe. I am an American.”

“I don’t believe in Americans,” said Mr. Burton calmly.

“Have you any brains?” demanded the exasperated Billy.

“I have,” said Mr. Burton, “and 1 want to keep ’em.”

The fog was growing thinner. Tam knew that he had no time to waste. He was sure of his ground and knew that he would make a good getaway. He searched in his fusilage and took out a spare map he had of the north of France and Belgium.

“You understand a chart, I suppose?”

“Aye, sir,” said the man.

“There’s yeer road. Ye’re not on it noo.”

He opened the little case in which he kept his emergency rations and cleared it.

“Put those in yeer pocket. They’ll keep ye alive for a day or two,” he said. “I would give ye money but it’s no use to ye. Besides, I’ve got none. Are ye sure ye won’t come?”

“Sure, sir.”

“Is there anything else I can do for ye?”

“If it’s not asking too much, sir, I’d like the loan of that little pistol of yours.”

Tam handed over the weapon and explained its mechanism.

“I might want it,” said the man; “there’s been a party of soldiers up and down this road for the last few days looking for me. It might be very useful,” he said thoughtfully. “And if you get back and you meet any of my friends—I’ve got no relations—tell them that Henry Burton of the Wapping Queen, late of Cabel Street, Whitechapel, was alive and well when last seen.”

He shook hands solemnly with the two men and turning, walked back to the road and the fog engulfed him.

“My, it’s like sending a man to his death,” said Billy and he spoke prophetically; “can’t we club him, Tam, and put him in the fusilage?”

“A’d no like to be clubbing a man that is two heads bigger than mesel’,” said Tam.

“Can’t we—” Billy stopped suddenly.

There was a sound of voices, one voice sharp, barking, peremptory and menacing. Billy gripped Tarn’s arm and they listened. They heard the snick of breechblocks.

“Soldiers,” whispered Tam; “contact, Billy!”

He jumped up into the fusilage and Billy Best ran to the propellor. Before he could turn it, there was a shot. Tam recognized the sting of his automatic. There was another and a yell. Then three rifles crashed together. Billy swung the propellor round and with a roar the engine started and slowly the big scout machine dragged forward through the mist, gathering speed.

Tam looked back. He saw a great bulky form blundering through the fog, saw it stiffen its arms and the quick flash of another explosion ere it fell heavily to the earth.

“Puir feller,” said Tam to himself and turned his whole attention to his engine.

The machine was still on the ground. The pace was increasing, but at any moment a tree or a high bush or a fence might leap out of the fog and crash him. He waited as long as he dared and then put the nose of the machine up and she rose swiftly and steeply. There was a breathless few seconds when a tree-top loomed up and vanished beneath them. Tam continued to climb. Such was the density of the fog belt that he did not reach blue sky until the altimeter showed six thousand feet. Beneath him was an unbroken plain of white woolly mist. He looked at his watch. The repairs had taken him longer than he had thought, but there were still three or four hours of daylight. The fog carried for seventy miles and there was no sign of a break. Tam was growing anxious, for he could not risk a landing in a machine which took the ground at sixty miles an hour on a country which he knew was broken by innumerable small fields.

“It will thin out if we go on long enough, Tam,” yelled Billy encouragingly and Tam grunted.

He dropped lower into the fog, came down within a hundred feet of the ground and narrowly escaped collision with a tall chimney-stack.

“Was that Lille?” roared Billy through the speaking-tube.

“A dinna recognize the chimney-stack,” said Tam, but his sarcasm was wasted, since Billy took him literally.

The situation was becoming serious when of a sudden, as though some hand had cut the fog vertically from top to base, he dived out of the thin layer of mist through which he had been flying, into sunlight, and below him was the sea.

There was no sign of land, no sign of ships, but the solution to his difficulty was a simple one. He had but to turn, flying low, and set a direct course eastward to strike a beach. He turned the machine sharply and planed down to within a hundred feet of the sea and steered by compass due east. He was farther out to sea than he had believed. He dived again into the wall of mist, but the water was plainly visible.

Then of a sudden Billy Best, who had nothing to do but enjoy the view, gripped Tarn’s shoulder.

“Look, look!” he yelled.

Tam looked down. Right ahead of him and moving across his course was a long black ship. At first Tam thought it was a Belgian barge, and then:

“A submarine!” shouted Billy.

The boat was awash and as the scout flashed across her Tam saw three men in her conning-tower and they were moving with some haste. He might be ten or fifty miles from the shore, he might have just sufficient juice to bring his machine safely to land, but here was an imperative duty and he swung his machine round and roared through the speaking-tube one word, and that word was: “Bomb!’’

Billy took a squint through the bombing-sight and gripped the release as Tam dipped down to the water. The bow of the submarine was already under water when Billy dropped the first bomb. It fell short by a dozen yards and Tam brought the airplane round in a circle.

“How many have ye?” he shouted.

“Two more,” said the muffled voice of Billy.

“Stand by,” said Tam and dipped again.

Only the conning-tower was above the water. Billy released the bomb and it fell just aft of the disappearing boat, throwing up a great column of water which sprayed the wings of the machine.

“Hell!” said Billy.

Again Tam turned. It was a race against time. Once the conning-tower was under water the chances of a vital hit were small. Tam dropped the machine lower still. He was not fifty feet above the last visible portion of the U-boat when the bomb dropped true.

The roar of the explosion sounded even above the noise of the engine. The airplane was flung up into the air like a piece of paper. Tam made a desperate effort to right her, but the wings were under water before he could pancake.

His first thought was of the submarine. Her bow had risen out of the water, so that it stood on end. The sea was covered with a yellow oily film.

“On behalf of Henry Burton,” said Tam, as he watched the hull drop out of sight.

His own position was a perilous one. The sea, however, was calm, and the machine floated, though her engines were now under water.

“Can ye swim fifty miles?” asked Tam.

“A fifty-mile swim is one of my hobbies,” said Billy.

He took from his pocket a large stick of candy, broke it exactly in half, and handed Tam his portion.

Tam took it in silence. “’Tis a horrible thought,” he said.

“What’s a horrible thought?” asked the other.

“That two flyin’ men, or one and a half flyin’ men,” he corrected, “should be drowned eatin’ toffee.”

“Would you rather be drowned smoking a cigar? Because I’ve got two.”

“A’ll reserve that for the last agony,” said Tam, and tested it conventionally. “I could have wished that it were a Havana or an El Dorado, or one of the expensive brands that the lower-class millionaires smoke.”

Presently Billy asked again: “How far do you think we are from land, Tam? Quit fooling.”

“A verra long way, A think,” said Tam seriously; “that U-boat wouldn’t have been close in.”

“It’s very foggy,” suggested Billy.

Tam nodded. “There’s that chance,” he said.

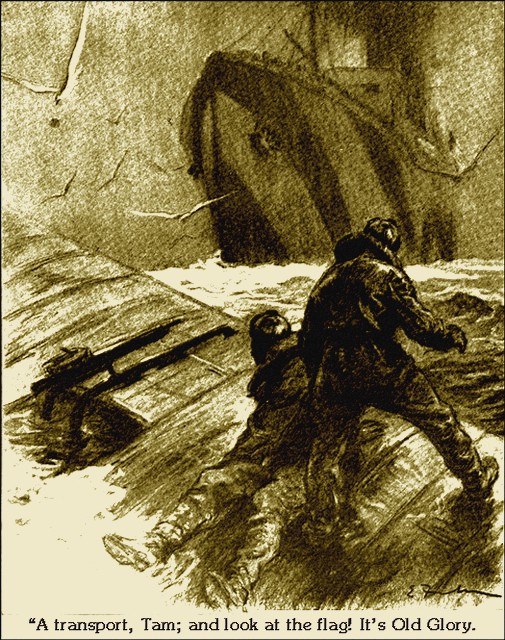

It was after sunset when rescue came. Out of the thin mist grew a big black ship, steaming slowly. Tam took his signal pistol from his pocket, fitted a cartridge and shot a Verey light into the air. They were near enough to see thousands of figures crowding the deck.

“It’s a transport,” cried Billy; “she’s stopping.”

“Oh, aye,” said Tam.

He had nearly reached the end of his cigar, but what was more important, the airplane was exhausting her last units of buoyancy. They saw the boat lowered away and the cream of foam as her engines went astern.

“Gee, Tam, it’s been a great day,” said Billy; “bombing von Tirpitz in the morning and his old murder boat in the afternoon—and by jiminy!” he stood up at some risk and his fresh young voice rose in one joyous yell, “A transport, Tam; and look at the flag! It’s Old Glory. Tam! It’s the greatest flag in the world, boy! Whoop! Do you see the flag, Tam? The flag that stands for God’s own country!”

"Mon, ye're light-headed," said Tam, "that's the American flag!"