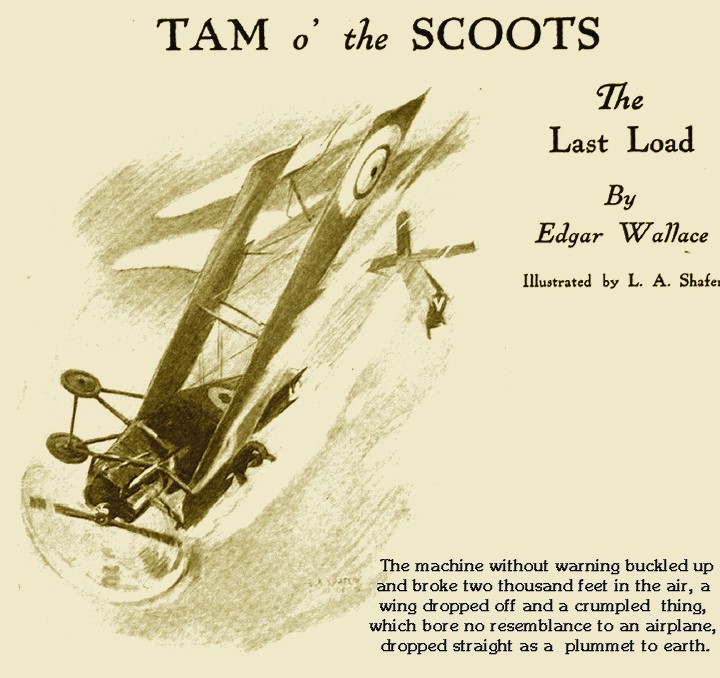

Tam o' the Scoots — A.L. Burt Edition, 1919

The world was a puddle of gloom and of shadowy

things,

He sped till the red and the gold of invisible day

Was burnish and flames to the undermost spread of his wings,

So he outlighted the stars as he poised in the grey.

Nearer was he to the knowledge and splendour of God,

Mysteries sealed from the ken of the ancient and wise—

Beauties forbidden to those who are one with the clod—

All that there was of the Truth was revealed to his eyes.

Flickers of fire from the void and the whistle of death,

Clouds that snapped blackly beneath him, above and beside,

Watch him, serene and uncaring—holding your breath,

Fearing his peril and all that may come of his pride.

Now he was swooped to the world like a bird to his nest,

Now is the drone of his coming the roaring of hell,

Now with a splutter and crash are the engines at rest—

All's well!—E.W.

LIEUTENANT BRIDGEMAN went out over the German line and "strafed" a depot. He stayed a while to locate a new gun position and was caught between three strong batteries of Archies.

"Reports?" said the wing commander. "Well, Bridgeman isn't back and Tam said he saw him nose-dive behind the German trenches."

So the report was made to Headquarters and Headquarters sent forward a long account of air flights for publication in the day's communiqué, adding, "One of our machines did not return."

"But, A' doot if he's killit," said Tam; "he flattened oot before he reached airth an' flew aroond a bit. Wi' ye no ask Mr. Lasky, sir-r, he's just in?"

Mr. Lasky was a bright-faced lad who, in ordinary circumstances, might have been looking forward to his leaving-book from Eton, but now had to his credit divers bombed dumps and three enemy airmen.

He met the brown-faced, red-haired, awkwardly built youth whom all the Flying Corps called "Tam."

"Ah, Tam," said Lasky reproachfully, "I was looking for you—I wanted you badly."

Tam chuckled.

"A' thocht so," he said, "but A' wis not so far frae the aerodrome when yon feller chased you—"

"I was chasing him!" said the indignant Lasky.

"Oh, ay?" replied the other skeptically. "An' was ye wantin' the Scoot to help ye chase ain puir wee Hoon? Sir-r, A' think shame on ye for misusin' the puir laddie."

"There were four," protested Lasky.

"And yeer gun jammed, A'm thinkin', so wi' rair presence o' mind, ye stood oop in the fuselage an' hit the nairest representative of the Imperial Gairman Air Sairvice a crack over the heid wi' a spanner."

A little group began to form at the door of the mess-room, for the news that Tam the Scoot was "up" was always sufficient to attract an audience. As for the victim of Tam's irony, his eyes were dancing with glee.

"Dismayed or frichtened by this apparition of the supermon i' the air-r," continued Tam in the monotonous tone he adopted when he was evolving one of his romances, "the enemy fled, emittin' spairks an' vapair to hide them from the veegilant ee o' young Mr. Lasky, the Boy Avenger, oor the Terror o' the Fairmament. They darted heether and theether wi' their remorseless pairsuer on their heels an' the seenister sound of his bullets whistlin' in their lugs. Ain by ain the enemy is defeated, fa'ing like Lucifer in a flamin' shrood. Soodenly Mr. Lasky turns verra pale. Heavens! A thocht has strook him. Where is Tam the Scoot? The horror o' the thocht leaves him braithless; an' back he tairns an' like a hawk deeps sweeftly but gracefully into the aerodrome— saved!"

"Bravo, Tam!" They gave him his due reward with great handclapping and Tam bowed left and right, his forage cap in his hand.

"Folks," he said, "ma next pairformance will be duly annoonced."

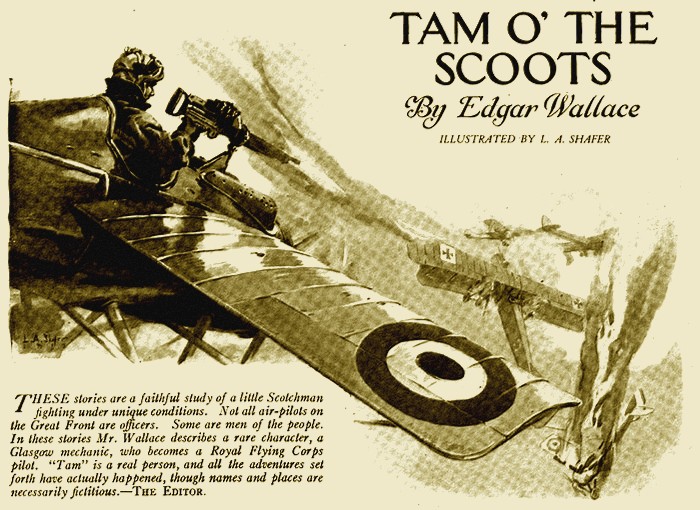

Tam came from the Clyde. He was not a ship-builder, but was the assistant of a man who ran a garage and did small repairs. Nor was he, in the accepted sense of the word, a patriot, because he did not enlist at the beginning of the war. His boss suggested he should, but Tam apparently held other views, went into a shipyard and was "badged and reserved."

They combed him out of that, and he went to another factory, making a false statement to secure the substitution of the badge he had lost. He was unmarried and had none dependent on him, and his landlord, who had two sons fighting, suggested to Tam that though he'd hate to lose a good lodger, he didn't think the country ought to lose a good soldier.

Tam changed his lodgings.

He moved to Glasgow and was insulted by a fellow workman with the name of coward. Tam hammered his fellow workman insensible and was fired forthwith from his job.

Every subterfuge, every trick, every evasion and excuse he could invent to avoid service in the army, he invented. He simply did not want to be a soldier. He believed most passionately that the war had been started with the sole object of affording his enemies opportunities for annoying him.

Then one day he was sent on a job to an aerodrome workshop. He was a clever mechanic and he had mastered the intricacies of the engine which he was to repair, in less than a day.

He went back to his work very thoughtfully, and the next Sunday he bicycled to the aerodrome in his best clothes and renewed his acquaintance with the mechanics.

Within a week, he was wearing the double-breasted tunic of the Higher Life. He was not a good or a tractable recruit. He hated discipline and regarded his superiors as less than equals—but he was an enthusiast.

When Pangate, which is in the south of England, sent for pilots and mechanics, he accompanied his officer and flew for the first time in his life.

In the old days he could not look out of a fourth-floor window without feeling giddy. Now he flew over England at a height of six thousand feet, and was sorry when the journey came to an end. In a few months he was a qualified pilot, and might have received a commission had he so desired.

"Thank ye, sir-r," he said to the commandant, "but ye ken weel A'm no gentry. M' fairther was no believer in education, an' whilst ither laddies were livin' on meal at the University A' was airning ma' salt at the Govan Iron Wairks. A'm no' a society mon ye ken—A'd be usin' the wrong knife to eat wi' an' that would bring the coorp into disrepute."

His education had, as a matter of fact, been a remarkable one. From the time he could read, he had absorbed every boy's book that he could buy or borrow. He told a friend of mine that when he enlisted he handed to the care of an acquaintance over six hundred paper-covered volumes which surveyed the world of adventure, from the Nevada of Deadwood Dick to the Australia of Jack Harkaway. He knew the stories by heart, their phraseology and their construction, and was wont at times, half in earnest, half in dour fun (at his own expense), to satirize every-day adventures in the romantic language of his favorite authors.

He was regarded as the safest, the most daring, the most venomous of the scouts—those swift-flying spitfires of the clouds—and enjoyed a fame among the German airmen which was at once flattering and ominous. Once they dropped a message into the aerodrome. It was short and humorous, but there was enough truth in the message to give it a bite:

Let us know when Tam is buried, we would a wreath subscribe.

Officers, German Imperial Air Service. Section—

Nothing ever pleased Tam so much as this unsolicited testimonial to his prowess.

He purred for a week. Then he learned from a German prisoner that the author of the note was the flyer of a big Aviatic, and went and killed him in fair fight at a height of twelve thousand feet.

"It was an engrossin' an' thrillin' fight," explained Tam; "the bluid was coorsin' in ma veins, ma hairt was palpitatin' wi' suppressed emotion. Roond an' roond ain another the dauntless airmen caircled, the noo above, the noo below the ither. Wi' supairb resolution Tam o' the Scoots nose-dived for the wee feller's tail, loosin' a drum at the puir body as he endeavoured to escape the lichtenin' swoop o' the intrepid Scotsman. Wi' matchless skeel, Tam o' the Scoots banked over an' brocht the gallant miscreant to terra firma —puir laddie! If he'd kept ben the hoose he'd no' be lyin' deid the nicht. God rest him!"

You might see Tam in the early morning, when the world was dark and only the flashes of guns revealed the rival positions, poised in the early sun, fourteen thousand feet in the air, a tiny spangle of white, smaller in magnitude than the fading stars. He seems motionless, though you know that he is traveling in big circles at seventy miles an hour.

He is above the German lines and the fleecy bursts of shrapnel and the darker patches where high explosive shells are bursting beneath him, advertise alike his temerity and the indignation of the enemy.

What is Tam doing there so early?

There has been a big raid in the dark hours; a dozen bombing machines have gone buzzing eastward to a certain railway station where the German troops waited in readiness to reinforce either A or B fronts. If you look long, you see the machines returning, a group of black specks in the morning sky. The Boches' scouts are up to attack—the raiders go serenely onward, leaving the exciting business of duel à l'outrance to the nippy fighting machines which fly above each flank. One such fighter throws himself at three of the enemy, diving, banking, climbing, circling and all the time firing "ticka—ticka—ticka—ticka!" through his propellers.

The fight is going badly for the bold fighting machine, when suddenly like a hawk, Tam o' the Scoots sweeps upon his prey. One of the enemy side-slips, dives and streaks to the earth, leaving a cloud of smoke to mark his unsubstantial path. As for the others, they bank over and go home. One falls in spirals within the enemy's lines. Rescuer and rescued land together. The fighting-machine pilot is Lieutenant Burnley; the observer, shot through the hand, but cheerful, is Captain Forsyn.

"Did ye no' feel a sense o' gratitude to the Almighty when you kent it were Tam sittin' aloft like a wee angel?"

"I thought it was a bombing machine that had come back," said Burnley untruthfully.

"Did ye hear that, sir-rs?" asked Tam wrathfully. "For a grown officer an' gentleman haulding the certeeficate of the Royal Flying Coorp, to think ma machine were a bomber! Did ye no' look oop an' see me? Did ye no' look thankfully at yeer obsairvor, when, wi' a hooricane roar, the Terror of the Air-r hurtled across the sky—'Saved!' ye said to yersel'; 'saved — an' by Tam! What can I do to shaw ma appreciation of the hero's devotion? Why!' ye said to yersel', soodenly, 'Why! A'll gi' him a box o' seegairs sent to me by ma rich uncle fra' Glasgae—!'"

"You can have two cigars, Tam—I'll see you to the devil before I give you any more—I only had fifty in the first place."

"Two's no' many," said Tam calmly, "but A've na doot A'll enjoy them wi' ma educated palate better than you, sir-r—seegairs are for men an' no' for bairns, an' ye'd save yersel' an awfu' feelin' o' seekness if ye gave me a'."

Tam lived with the men—he had the rank of sergeant, but he was as much Tam to the private mechanic as he was to the officers. His pay was good and sufficient. He had shocked that section of the Corps Comforts Committee which devoted its energies to the collection and dispatch of literature, by requesting that a special effort be made to keep him supplied "wi' th' latest bluids." A member of the Committee with a sneaking regard for this type of literature took it upon himself to ransack London for penny dreadfuls, and Tam received a generous stock with regularity.

"A'm no' so fond o' th' new style," he said; "the detective stoory is verra guid in its way for hame consumption, but A' prefair the mair preemative discreeptions, of how that grand mon, Deadwood Dick, foiled the machinations of Black Peter, the Scoorge of Hell Cañon. A've no soort o' use for the new kind o' stoory—the love-stoories aboot mooney. Ye ken the soort: Harild is feelin' fine an' anxious aboot Lady Gwendoline's bairthmark: is she the rechtfu' heir? Oh, Heaven help me to solve the meestry! (To be continued in oor next.) A'm all for bluid an' fine laddies wi' a six-shooter in every hand an' a bowie-knife in their teeth—it's no' so intellectual, but, mon, it's mair human!"

Tam was out one fine spring afternoon in a one-seater Morane. He was on guard watching over the welfare of two "spotters" who were correcting the fire of a "grandmother" battery. There was a fair breeze blowing from the east, and it was bitterly cold, but Tam in his leather jacket, muffled to the eyes, and with his hands in fur-lined gloves and with the warmth from his engine, was comfortable without being cozy.

Far away on the eastern horizon he saw a great cloud. It was a detached and imperial cumulus, a great frothy pyramid that sailed in majestic splendor. Tam judged it to be a mile across at its base and calculated its height, from its broad base to its feathery spirelike apex, at another mile.

"There's an awfu' lot of room in ye," he thought.

It was moving slowly toward him and would pass him at such a level that did he explore it, he would enter half-way between its air foundation and its peak.

He signaled with his wireless, "Am going to explore cloud," and sent his Morane climbing.

He reached the misty outskirts of the mass and began its encirclement, drawing a little nearer to its center with every circuit. Now he was in a white fog which afforded him only an occasional glimpse of the earth. The fog grew thicker and darker and he returned again to the outer edge because there would be no danger in the center. Gently he declined his elevator and sank to a lower level. Then suddenly, beneath him, a short shape loomed through the mist and vanished in a flash. Tam had a tray of bombs under the fuselage— something in destructive quality between a Mills grenade and a three-inch shell.

He waited...

Presently—swish! They were circling in the opposite direction to Tam, which meant that the object passed him at the rate of one hundred and forty miles an hour. But he had seen the German coming... Something dropped from the fuselage, there was the rending crash of an explosion and Tam dropped a little, swerved to the left and was out in clear daylight in a second.

Back he streaked to the British lines, his wireless working frantically.

"Enemy raiding squadron in cloud—take the edge a quarter up."

He received the acknowledgment and brought his machine around to face the lordly bulk of the cumulus.

Then the British Archies began their good work.

Shrapnel and high explosives burst in a storm about the cloud. Looking down he saw fifty stabbing pencils of flame flickering from fifty A-A guns. Every available piece of anti-aircraft artillery was turned upon the fleecy mass.

As Tam circled he saw white specks rising swiftly from the direction of the aerodrome and knew that the fighting squadron, full of fury, was on its way up. It had come to be a tradition in the wing that Tam had the right of initiating all attack, and it was a right of which he was especially jealous. Now, with the great cloud disgorging its shadowy guests, he gave a glance at his Lewis gun and drove straight for his enemies. A bullet struck the fuselage and ricocheted past his ear; another ripped a hole in the canvas of his wing. He looked up. High above him, and evidently a fighting machine that had been hidden in the upper banks of the cloud, was a stiffly built Fokker.

"Noo, lassie!" said Tam and nose-dived.

Something flashed past his tail, and Tam's machine rocked like a ship at sea. He flattened out and climbed. The British Archies had ceased fire and the fight was between machine and machine, for the squadron was now in position. Tam saw Lasky die and glimpsed the flaming wreck of the boy's machine as it fell, then he found himself attacked on two sides. But he was the swifter climber—the faster mover. He shot impartially left and right and below —there was nothing above him after the first surprise. Then something went wrong with his engines—they missed, started, missed again, went on —then stopped.

He had turned his head for home and begun his glide to earth.

He landed near a road by the side of which a Highland battalion was resting and came to ground without mishap. He unstrapped himself and descended from the fuselage slowly, stripped off his gloves and walked to where the interested infantry were watching him.

"Where are ye gaun?" he asked, for Tam's besetting vice was an unquenchable curiosity.

"To the trenches afore Masille, sir-r," said the man he addressed.

"Ye'll no' be callin' me 'sir-r,'" reproved Tam. "A'm a s-arrgent. Hoo lang will ye stay in the trenches up yon?"

"Foor days, Sergeant," said the man.

"Foor days—guid Lord!" answered Tam. "A' wouldn't do that wairk for a thoosand poonds a week."

"It's no' so bad," said half-a-dozen voices.

"Ut's verra, verra dangerous," said Tam, shaking his head. "A'm thankitfu' A'm no' a soldier—they tried haird to make me ain, but A' said, 'Noo, laddie—gie me a job—'"

"Whoo!"

A roar like the rush of an express train through a junction, and Tam looked around in alarm. The enemy's heavy shell struck the ground midway between him and his machine and threw up a great column of mud.

"Mon!" said Tam in alarm. "A' thocht it were goin' straicht for ma wee machine."

"What happened to you, Tam?" asked the wing commander.

Tam cleared his throat.

"Patrollin' by order the morn," he said, "ma suspeecions were aroused by the erratic movements of a graund clood. To think, wi' Tam the Scoot, was to act. Wi'oot a thocht for his ain parrsonal safety, the gallant laddie brocht his machine to the clood i' question, caircling through its oombrageous depths. It was a fine gay sicht—aloon i' th' sky, he ventured into the air-r-lions' den. What did he see? The clood was a nest o' wee horrnets! Slippin' a bomb he dashed madly back to the ooter air-r sendin' his S. O. S. wi' baith hands—thanks to his—"

He stopped and bit his lip thoughtfully.

"Come, Tam!" smiled the officer, "that's a lame story for you."

"Oh, ay," said Tam. "A'm no' in the recht speerit—Hoo mony did we lose?"

"Mr. Lasky and Mr. Brand," said the wing commander quietly.

"Puir laddies," said Tam. He sniffed. "Mr. Lasky was a bonnie lad — A'll ask ye to excuse me, Captain Thompson, sir-r. A'm no feelin' verra weel the day—ye've no a seegair aboot ye that ye wilna be wantin'?"

TAM was not infallible, and the working out of his great "thochts" did not always justify the confidence which he reposed in them. His idea of an "invisible aeroplane," for example, which was to be one painted sky blue that would "hairmonise wi' the blaw skies," was not a success, nor was his scheme for the creation of artificial clouds attended by any encouraging results. But Tam's "Attack Formation for Bombing Enemy Depots" attained to the dignity of print, and was confidentially circulated in French, English, Russian, Italian, Serbian, Japanese and Rumanian.

The pity is that a Scottish edition was not prepared in Tam's own language; and Captain Blackie, who elaborated Tam's rough notes and condensed into a few lines Tam's most romantic descriptions, had suggested such an edition for very private circulation.

It would have begun somewhat like this:

"The Hoon or Gairman is a verra bonnie fichter, but he has nae ineetiative. He squints oop in the morn an' he speers a fine machine ower by his lines.

"'Hoot!' says he, 'yon wee feller is Scottish, A'm thinkin'—go you, Fritz an' Hans an' Carl an' Heinrich, an' strafe the puir body.'

"'Nay,' says his oonder lootenant. 'Nein,' he says, 'ye daunt knaw what ye're askin', Herr Lootenant.'

"'What's wrong wi' ye?' says the oberlootenant. 'Are ye Gairman heroes or just low-doon Austreens that ye fear ain wee bairdie?'

"'Lootenant,' say they, 'yon feller is Tam o' the Scoots, the Brigand o' the Stars!'

"'Ech!' he says. 'Gang oop, ain o' ye, an' ask the lad to coom doon an' tak' a soop wi' us—we maun keep on the recht side o' Tam!'"

All this and more would have gone to form the preliminary chapter of the true version of Tam's code of attack.

"He's a rum bird, is Tam," said Captain Blackie at breakfast; "he brought down von Zeidlitz yesterday."

"Is von Zeidlitz down?" demanded half a dozen voices, and Blackie nodded.

"He was a good, clean fighter," said young Carter regretfully. "When did you hear this, sir?"

"This morning, through H. Q. Intelligence."

"Tam will be awfully bucked," said somebody. "He was complaining yesterday that life was getting too monotonous. By the way, we ought to drop a wreath for poor old von Zeidlitz."

"Tam will do it with pleasure," said Blackie; "he always liked von Zeidlitz—he called him 'Fritz Fokker' ever since the day von Zeidlitz nearly got Tam's tail down."

An officer standing by the window with his hands thrust into his pockets called over his shoulder:

"Here comes Tam."

The thunder and splutter of the scout's engine came to them faintly as Tam's swift little machine came skimming across the broad ground of the aerodrome and in a few minutes Tam was walking slowly toward the office, stripping his gloves as he went.

Blackie went out to him.

"Hello, Tam—anything exciting?"

Tam waved his hand—he never saluted.

"Will ye gang an' tak' a look at me eenstruments?" he asked mysteriously.

"Why, Tam?"

"Will ye, sir-r?"

Captain Blackie walked over to the machine and climbed up into the fuselage. What he saw made him gasp, and he came back to where Tam was standing, smug and self-conscious.

"You've been up to twenty-eight thousand feet, Tam?" asked the astonished Blackie. "Why, that is nearly a record!"

"A' doot ma baromeeter," said Tam; "if A' were no' at fochty thousand, A'm a Boche."

Blackie laughed.

"You're not a Boche, Tam," he said, "and you haven't been to forty thousand feet—no human being can rise eight miles. To get up five and a half miles is a wonderful achievement. Why did you do it?"

Tam grinned and slapped his long gloves together.

"For peace an' quiet," he said. "A've been chased by thairty air Hoons that got 'twixt me an' ma breakfast, so A' went oop a bit an' a bit more an' two fellers came behint me. There's an ould joke that A've never understood before—'the higher the fewer'—it's no' deefficult to understand it noo."

"You got back all right, anyhow," said Blackie.

"Aloon i' the vast an' silent spaces of the vaulted heavens," said Tam in his sing-song tones which invariably accompanied his narratives, "the Young Avenger of the Cloods, Tam the Scoot, focht his ficht. Attacked by owerwhelmin' foorces, shot at afore an' behint, the noble laddie didna lose his nairve. Mutterin' a brief—a verra brief—prayer that the Hoons would be strafed, he climbt an' climbt till he could 'a' strook a match on the moon. After him wi' set lips an' flashin' een came the bluidy-minded ravagers of Belgium, Serbia an'—A'm afreed—Roomania. Theer bullets whistled aboot his lugs but,

"His eyes were bricht,

His hairt were licht,

For Tam the Scoot was fu' o' ficht—"

"That's a wee poem A' made oop oot o' ma ain heid, Captain, at a height of twenty-three thoosand feet. A'm thinkin' it's the highest poem in the wairld."

"And you're not far wrong—well, what happened?"

"A' got hame," said Tam grimly, "an' ain o' yon Hoons did no' get hame. Mon! It took him an awfu' long time to fa'!"

He went off to his breakfast and later, when Blackie came in search for him, he found him lying on his bed smoking a long black cigar, his eyes glued to the pages of "Texas Tom, or the Road Agent's Revenge."

"I forgot to tell you, Tam," said Captain Blackie, "that von Zeidlitz is down."

"Doon?" said Tam, "'Fritz Fokker' doon? Puir laddie! He were a gay fichter—who straffit him?"

"You did—he was the man you shot down yesterday."

Tam's eyes were bright with excitement.

"Ye're fulin' me noo?" he asked eagerly. "It wisna me that straffit him? Puir auld Freetz! It were a bonnie an' a carefu' shot that got him. He wis above me, d'ye ken? 'Ah naw!' says I. 'Ye'll no try that tailbitin' trick on Tam,' says I; 'naw, Freetz—!' An' I maneuvered to miss him. I put a drum into him at close range an' the puir feller side-slippit an' nose-dived. Noo was it Freetz, then? Weel, weel!"

"We want you to take a wreath over—he'll be buried at Ludezeel."

"With the verra greatest pleasure," said Tam heartily, "and if ye'll no mind, Captain, A'd like to compose a wee vairse to pit in the box."

For two hours Tam struggled heroically with his composition. At the end of that time he produced with awkward and unusual diffidence a poem written in his sprawling hand and addressed:

Dedication to Mr. von Sidlits By Tam of the Scoots

"I'll read you the poem, Captain Blackie, sir-r," said Tam nervously, and after much coughing he read:

"A graund an' nooble clood Was the flyin' hero's shrood Who dies at half- past seven And he verra well desairves The place that God resairves For the men who die in Heaven.

"A've signed it, 'Kind regards an' deepest sympathy wi' a' his loved ains,'" said Tam. "A' didna say A' killit him—it would no be delicate."

The wreath in a tin box, firmly corded and attached to a little parachute, was placed in the fuselage of a small Morane—his own machine being in the hands of the mechanics—and Tam climbed into the seat. In five minutes he was pushing up at the steep angle which represented the extreme angle at which a man can fly. Tam never employed a lesser one.

He had learnt just what an aeroplane could do, and it was exactly all that he called for. Soon he was above the lines and was heading for Ludezeel. Archies blazed and banged at him, leaving a trail of puff balls to mark his course; an enemy scout came out of the clouds to engage him and was avoided, for the corps made it a point of honor not to fight when engaged on such a mission as was Tam's.

Evidently the enemy scout realized the business of this lone British flyer and must have signaled his views to the earth, for the anti-aircraft batteries suddenly ceased fire, and when, approaching Ludezeel, Tam sighted an enemy squadron engaged in a practise flight, they opened out and made way for him, offering no molestation.

Tam began to plane down. He spotted the big white-speckled cemetery and saw a little procession making its way to the grounds. He came down to a thousand feet and dropped his parachute. He saw it open and sail earthward and then some one on the ground waved a white handkerchief.

"Guid," said Tam, and began to climb homeward.

The next day something put out of action the engine of that redoubtable fighter, Baron von Hansen-Bassermann, and he planed down to the British aerodrome with his machine flaming.

A dozen mechanics dashed into the blaze and hauled the German to safety, and, beyond a burnt hand and a singed mustache, he was unharmed.

Lieutenant Baron von Hansen-Bassermann was a good-looking youth. He was, moreover, an undergraduate of Oxford University and his English was perfect.

"Hard luck, sir," said Blackie, and the baron smiled.

"Fortunes of war. Where's Tam?" he asked.

"Tam's up-stairs somewhere," said Blackie. He looked up at the unflecked blue of the sky, shading his eyes. "He's been gone two hours."

The baron nodded and smiled again.

"Then it was Tam!" he said. "I thought I knew his touch—does he 'loop' to express his satisfaction?"

"That's Tam!" said a chorus of voices.

"He was sitting in a damp cloud waiting for me," said the baron ruefully. "But who was the Frenchman with him?"

Blackie looked puzzled.

"Frenchman? There isn't a French machine within fifty miles; did he attack you, too?"

"No—he just sat around watching and approving. I had the curious sense that I was being butchered to make a Frenchman's holiday. It is curious how one gets those quaint impressions in the air—it is a sort of ninth sense. I had a feeling that Tam was 'showing off'—in fact, I knew it was Tam, for that reason."

"Come and have some breakfast before you're herded into captivity with the brutal soldiery," said Blackie, and they all went into the mess-room together, and for an hour the room rang with laughter, for both the baron and Captain Blackie were excellent raconteurs.

Tam, when he returned, had little to say about his mysterious companion in the air. He thought it was a "French laddie." Nor had he any story to tell about the driving down of the baron's machine. He could only say that he "kent" the baron and had met his Albatross before. He called him the "Croon Prince" because the black crosses painted on his wings were of a more elaborate design than was usual.

"You might meet the baron, Tam," said the wing commander. "He's just off to the Cage, and he wants to say 'How-d'-ye-do.'"

Tam met the prisoner and shook hands with great solemnity.

"Hoo air ye, sir-r?" he asked with admirable sang-froid. "A' seem to remember yer face though A' hae no' met ye—only to shoot at, an' that spoils yeer chance o' gettin' acquainted wi' a body."

"I think we've met before," said the baron with a grim little smile. "Oh, before I forget, we very much appreciated your poem, Tam; there are lines in it which were quite beautiful."

Tam flushed crimson with pleasure.

"Thank ye, sir-r," he blurted. "Ye couldna' 'a' made me more pleased —even if A' killit ye."

The baron threw back his head and laughed.

"Good-by, Tam—take care of yourself. There's a new man come to us who will give you some trouble."

"It's no' Mister MacMuller?" asked Tam eagerly.

"Oh—you've heard of Captain Müller?" asked the prisoner interestedly.

"Haird?—good Lord, mon—sir-r, A' mean—look here!"

He put his hand in his pocket and produced a worn leather case. From this he extracted two or three newspaper cuttings and selected one, headed "German Official."

"'Captain Muller,'" read Tam, "'yesterday shot doon his twenty-sixth aeroplane.'"

"That's Müller," said the other carefully. "I can tell you no more —except look after yourself."

"Ha'e na doot aboot that, sir-r," said Tam with confidence.

He went up that afternoon in accordance with instructions received from headquarters to "search enemy territory west of a line from Montessier to St. Pierre le Petit."

He made his search, and sailed down with his report as the sun reached the horizon.

"A verra quiet joorney," he complained, "A' was hopin' for a squint at Mr. MacMuller, but he was sleeping like a doormoose—A' haird his snoor risin' to heaven an' ma hairt wis sick wi' disappointed longin'. 'Hoo long,' A' says, 'hoo long will ye avoid the doom Tam o' the Scoots has marked ye doon for?' There wis naw reply."

"I've discovered Tam's weird pal," said Blackie, coming into the mess before lunch the next day. "He is Claude Beaumont of the American Squadron —Lefèvre, the wing commander, was up to-day. Apparently Beaumont is an exceedingly rich young man who has equipped a wing with its own machines, hangars and repair-shop, and he flies where he likes. Look at 'em!"

They crowded out with whatever glasses they could lay their hands upon and watched the two tiny machines that circled and dipped, climbed and banked about one another.

First one would dart away with the other in pursuit, then the chaser, as though despairing of overtaking his quarry, would turn back. The "hare" would then turn and chase the other.

"Have you ever seen two puppies at play?" asked Blackie. "Look at Tam chasing his tail—and neither man knows the other or has ever looked upon his face! Isn't it weird? That's von Hansen-Bassermann's ninth sense. They can't speak—they can't even see one another properly and yet they're good pals—look at 'em. I've watched the puppies of the pack go on in exactly the same way."

"What is Tam supposed to be doing?"

"He's watching the spotters. Tam will be down presently and we'll ask David how he came to meet Jonathan—this business has been going on for weeks."

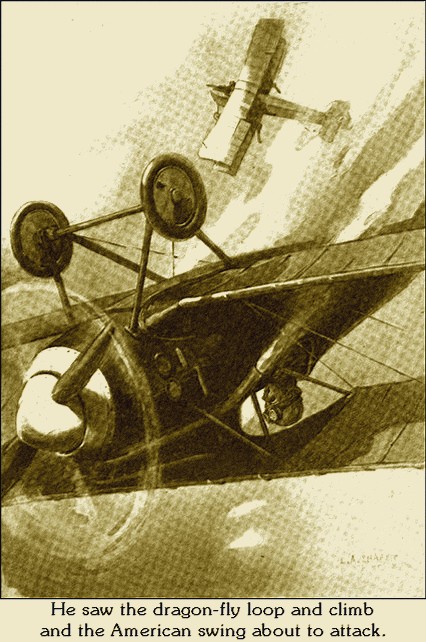

Tam had received the recall signal. Beneath him he saw the two "spotters" returning home, and he waved his hand to his sporting companion and came round in a little more than twice his own length. He saw his strange friend's hand raised in acknowledgment, and watched him turn for the south. Tam drove on for a mile, then something made him look back.

Above his friend was a glittering white dragon-fly, and as he looked the fly darted down at the American tail.

"Missed him!" said Tam, and swung round. He was racing with the wind at top speed and he must have been doing one hundred and twenty miles an hour, but for the fact that he was climbing at the extreme angle. He saw the dragon-fly loop and climb and the American swing about to attack.

But his machine was too slow—that Tam knew. Nothing short of a miracle could save the lower machine, for the enemy had again reached the higher position. So engrossed was he with his plan that he did not see Tam until the Scot was driving blindly to meet him—until the first shower from Tam's Lewis gun rained on wing and fuselage. The German swerved in his drive and missed his proper prey. Tam was behind him and above him, but in no position to attack. He could, and did fire a drum into the fleeing foeman, but none of the shots took effect.

"Tairn him, Archie!" groaned Tam, and as though the earth gunners had heard his plea, a screen of bursting shrapnel rose before the dragon-fly. He turned and nose-dived with Tam behind him, but now his nose was for home, and Tam, after a five-mile pursuit, came round and made for home also. Near his own lines he came up with the circling "Frenchman" and received his thanks — four fingers extended in the air—before the signaler, taking a route within the lines, streaked for home.

"Phew!" said Tam, shaking his head.

"Who were you chasing?" asked Blackie. "He can go!"

"Yon's MacMuller," said Tam, jerking his thumb at the eastern sky. "He's a verra likeable feller—but a wee bit too canny an' a big bit too fast. Captain Blackie, sir-r, can ye no get me a machine that can flee? Ma wee machine is no' unlike a hairse, but A'm wishfu' o' providin' the coorpse."

"You've got the fastest machine in France, Tam," said the captain.

Tam nodded.

"It's verra likely—she wis no' runnin' so sweet," he confessed. "But, mon! That Muller! He's a braw Hoon an' A'm encouraged by the fine things that the baron said aboot ma poetry. Ech! A've got a graund vairse in ma heid for Mr. Muller's buryin'! Hae ye a seegair aboot ye, Captain Blackie? A' gave ma case to the Duke of Argyle an' he has no' retairned it."

THERE arrived one day at the aerodrome a large packing-case addressed "Sergeant Tam." There was no surname, though there was no excuse for the timidity which stopped short at "Tam." The consignor might, at least, have ventured to add a tentative and inquiring "Mac?"

Tam took the case into his little "bunk" and opened it. The stripping of the rough outer packing revealed a suave, unpolished cedar cabinet with two doors and a key that dangled from one of the knobs. Tam opened the case after some consideration and disclosed shelf upon shelf tightly packed with bundles of rich, brown, fragrant cigars.

There was a card inscribed:

"Your friend in the Merman pusher."

"Who," demanded Tam, "is ma low acqueentance, who dispoorts himsel' in an oot-o'-date machine?"

Young Carter, who had come in to inspect the unpacking, offered a suggestion.

"Probably the French machine that is always coming over here to see you," he said, "Mr. Thiggamy-tight, the American."

"Ah, to be sure!" said Tam relieved. "A' thocht maybe the Kaiser had sent me droogged seegairs—A'm an awfu' thorn in the puir laddie's side. Ye may laugh, Mister Carter, but A' reca' a case wheer a bonnie detective wi' the same name as ye'sel', though A' doot if he wis related to ye, was foiled by the machinations o' Ferdie the Foorger at the moment o' his triumph by the lad gieing him a seegair soaked in laud'num an' chlorofor-rm!"

He took a bundle, slipped out two cigars, offered one to his officer, after a brief but baffling examination to discover which was the worse, and lit the other.

"They're no' so bad," he admitted, "but yeer ain seegairs never taste so bonnie as the seegairs yeer frien's loan ye."

"They came in time," said Carter; "we'd started a League for the Suppression of Cigar Cadging."

"Maybe ye thocht o' makin' me treesurer? Naw? Ah weel, a wee seegair is no muckle to gie a body wha's brocht fame an' honor to the Wing."

"I often wonder, Tam," said Carter, "how much you're joking and laughing at yourself when you're talking about 'Tam, the Terror of the Clouds,' and how much you're in earnest."

A fleeting smile flickered for a second about Tam's mouth and vanished.

"In all guid wairks of reference, fra' Auld Morre's Almanac to the Clyede River Time-Table," he said soberly, "it's written that a Scotsman canna joke. If A'd no talk about Tam—would ye talk aboot ye'sel's? Naw! Ye'd go oop an' doon, fichtin' an' deein' wi'oot a waird. If ye'll talk aboot ye'sel's A'll no talk aboot Tam. A' knaw ma duty, Mister Carter—A'm the offeecial boaster o' the wing an' the coor, an' whin they bring me doon wi' a bullet in ma heid, A' hope ye'll engage anither like me."

"There isn't another like you, Tam," laughed Carter.

"Ye dinna knaw Glasca,'" replied Tam darkly.

Lieutenant Carter went up on "a tour of duty" soon after and Tam was on the ground to watch his departure.

"Tam," he shouted, before the controls were in, "I liked that cigar —I'll take fifty from you to-night."

"Ower ma deid body," said Tam, puffing contentedly at the very last inch of his own; "the watch-wairds o' victory are 'threeft an' economy'!"

"I've warned you," roared Carter, for now the engine was going.

Tam nodded a smiling farewell as the machine skipped and ran over the ground before it swooped upward into space.

He went back to his room, but had hardly settled himself to the examination of a new batch of blood-curdling literature before Blackie strode in.

"Mr. Carter's down, Tam," he said.

"Doon!"

Tam jumped up, a frown on his face.

"Shot dead and fell inside our lines—go up and see if you can find Müller."

Tam dressed slowly. Behind the mask of his face, God knows what sorrow lay, for he was fond of the boy, as he had been fond of so many boys who had gone up in the joy and pride of their youth, and had earned by the supreme sacrifice that sinister line in the communiques: "One of our machines did not return."

He ranged the heavens that day seeking his man. He waited temptingly in reachable places and even lured one of his enemies to attack him.

"There's something down," said Blackie, as a flaming German aeroplane shot downward from the clouds. "But I'm afraid it's not Müller this time."

It was not. Tam returned morose and uncommunicative. His anger was increased when the intercepted wireless came to hand in the evening:

"Captain Müller shot down his twenty-seventh aeroplane."

That night, when the mess was sitting around after dinner, Tam appeared with a big armful of cigars.

"What's the matter with 'em?" asked Blackie in mock alarm.

"They're a' that Mister Carter bocht," said Tam untruthfully, "an' A' thocht ye'd wish to ha'e a few o' the laddie's seegairs."

Nobody was deceived. They pooled the cigars for the mess and Tam went back to his quarters lighter of heart. He slept soundly and was wakened an hour before dawn by his batman.

"'The weary roond, the deely task,'" quoted Tam, taking the steaming mug of tea from his servant's hands. "What likes the mornin', Horace?"

"Fine, Sergeant—clear sky an' all the stars are out."

"Fine for them," said Tam sarcastically, "they've nawthin' to do but be oot or in—A've no patience wi' the stars—puir silly bodies winkin' an' blinkin' an' doin' nae guid to mon or beastie—chuck me ma breeches an' let the warm watter rin in the bath."

In the gray light of dawn the reliefs stood on the ground, waiting for the word "go."

"A' wonder what ma frien' MacMuller is thinkin' the morn?" asked Tam; "wi' a wan face an' a haggaird een, he'll be takin' a moornfu' farewell o' the Croon Prince Ruppect.

"'Ye're a brave lad,' says the Croon Prince, 'but maybe Tam's awa'.'

"'Naw,' says MacMuller, shakin' his heid, 'A've a presentiment that Tam's no' awa'. He'll be oop-stairs waitin' to deal his feelon's-blow. Ech!' says Mister MacMuller, 'for why did I leave ma fine job at the gas-wairks to encoonter the perils an' advairsities of aerial reconnaissance?' he says. 'Well, I'll be gettin' alang, yeer Majesty or Highness—dawn't expect ma till ye see ma.'

"He moonts his graind machine an' soon the intreepid baird-man is soorin' to the skies. He looks oop—what is that seenister for-rm lairking in the cloods? It is Tam the Comet!"

"Up, you talkative devil," said Blackie pleasantly.

Tam rode upward at an angle which sent so great a pressure of air against him that he ached in back and arm and legs to keep his balance. It was as though he were leaning back without support, with great weights piled on his chest. He saw nothing but the pale blue skies and the fleecy trail of high clouds, heard nothing but the numbing, maddening roar of his engines.

He sang a little song to himself, for despite his discomfort he was happy enough. His eyes were for the engine, his ears for possible eccentricities of running. He was pushing a straight course and knew exactly where he was by a glance at his barometer. At six thousand feet he was behind the British lines at the Bois de Colbert, at seven thousand feet he should be over Nivelle- Ancre and should turn so that he reached his proper altitude at a point one mile behind the fire trenches and somewhere in the region of the Bois de Colbert again.

The aeronometer marked twelve thousand feet when he leveled the machine and began to take an interest in military affairs. The sky was clear of machines, with the exception of honest British spotters lumbering along like farm laborers to their monotonous toil. A gentlemanly fighting machine was doing "stunts" over by Serray and there was no sign of an enemy. Tam looked down. He saw a world of tiny squares intersected by thin white lines. These were main roads. He saw little dewdrops of water occurring at irregular intervals. They were really respectable-sized lakes.

Beneath him were two irregular scratches against the dull green-brown of earth that stretched interminably north and south. They ran parallel at irregular distances apart. Sometimes they approached so that it seemed that they touched. In other places they drew apart from one another for no apparent reason and there was quite a respectable distance of ground between them. These were the trench lines, and every now and again on one side or the other a puff of dirty brown smoke would appear and hang like a pall before the breeze sent it streaming slowly backward.

Sometimes the clouds of smoke would be almost continuous, but these shell- bursts were not confined to the front lines. From where Tam hung he could see billowing smoke clouds appear in every direction. Far behind the enemy's lines at the great road junctions, in the low-roofed billeting villages, on the single-track railways, they came and went.

The thunder of his engines drowned all sound so he could not hear the never-ceasing booming of the guns, the never-ending crash of exploding shell. Once he saw a heavy German shell in the air—he glimpsed it at that culminating point of its trajectory where the shell begins to lose its initial velocity and turns earthward again. It was a curious experience, which many airmen have had, and quite understandable, since the howitzer shell rises to a tremendous height before it follows the descending curve of its flight.

He paid a visit to the only cloud that had any pretensions to being a cloud, and found nothing. So he went over the German lines. He passed far behind the fighting front and presently came above a certain confusion of ground which marked an advance depot. He pressed his foot twice on a lever and circled. Looking down he saw two red bursts of flame and a mass of smoke. He did not hear the explosions of the bombs he had loosed, because it was impossible to hear anything but the angry "Whar-r-r—!" of his engines.

A belligerent is very sensitive over the matter of bombed depots, and Tam, turning homeward, looked for the machines which would assuredly rise to intercept him. Already the Archies were banging away at him, and a fragment of shell had actually struck his fuselage. But he was not bothering about Archies. He did swerve toward a battery skilfully hidden behind a hayrick and drop two hopeful bombs, but he scarcely troubled to make an inspection of the result.

Then before him appeared his enemy. Tam had the sun at his back and secured a good view of the Müller machine. It was the great white dragon-fly he had seen two days before. Apparently Müller had other business on hand. He was passing across Tam's course diagonally—and he was climbing.

Tam grinned. He was also pushing upward, for he knew that his enemy, seemingly oblivious to his presence, had sighted him and was getting into position to attack. Tam's engine was running beautifully, he could feel a subtle resolution in the "pull" of it; it almost seemed that this thing of steel was possessed of a soul all its own. He was keeping level with the enemy, on a parallel course which enabled him to keep his eye upon the redoubtable fighter.

Then, without warning, the German banked over and headed straight for Tam, his machine-gun stuttering. Tam turned to meet him. They were less than half a mile from each other and were drawing together at the rate of two hundred miles an hour. There were, therefore, just ten seconds separating them. What maneuver Müller intended is not clear. He knew—and then he realized in a flash what Tam was after.

Round he went, rocking like a ship at sea. A bullet struck his wheel and sent the smashed wood flying. He nose-dived for his own lines and Tam glared down after him.

Müller reached his aerodrome and was laughing quietly when he descended.

"I met Tam," he said to his chief; "he tried to ram me at sixteen thousand feet—Oh, yes. I came down, but—ich habe das nicht gewollt!—I did not will it!"

Tam returned to his headquarters full of schemes and bright "thochts."

"You drove him down?" said the delighted Blackie. "Why, Tam, it's fine! Müller never goes down—you've broken one of his traditions."

"A' wisht it was ain of his heids," said Tam. "A' thocht for aboot three seconds he was acceptin' the challenge o' the Glasca' Ganymede— A'm no' so sure o' Ganymede; A' got him oot of the sairculatin' library an' he was verra dull except the bit wheer he went oop in the air on the back of an eagle an' dropped his whustle. But MacMuller wasn't so full o' ficht as a' that."

He walked away, but stopped and came back.

"A'm a Wee Kirker," he said. "A' remembered it when A' met MacMuller. Though A'm no particular hoo A'm buried, A'm entitled to a Wee Kirk meenister. Mony's the time A've put a penny i' the collection. It sair grievit me to waste guid money, but me auld mither watchit me like a cat, an' 'twere as much as ma life was worth to pit it in ma breeches pocket."

Tam spent the flying hours of the next day looking for his enemy, but without result. The next day he again drew blank, and on the third day took part in an organized raid upon enemy communications, fighting his way back from the interior of Belgium single-handed, for he had allowed himself to be "rounded out" and had to dispose of two enemy machines before he could go in pursuit of the bombing squadrons. In consequence, he had to meet and reject the attentions of every ruffled enemy that the bombers and their bullies had fought in passing.

At five o'clock in the evening he dropped from the heavens in one straight plummet dive which brought him three miles in a little under one minute.

"Did you meet Müller?" asked Captain Blackie; "he's about —he shot down Mr. Grey this morning whilst you were away."

"Mr. Gree? Weel, weel!" said Tam, shaking, "puir soul—he wis a verra guid gentleman—wit' a gay young hairt."

"I hope Tam will pronounce my epitaph," said Blackie to Bolt, the observer; "he doesn't know how to think unkindly of his pals."

"Tam will get Müller," said Bolt. "I saw the scrap the other day —Tam was prepared to kill himself if he could bring him down. He was out for a collision, I'll swear, and Müller knew it and lost his nerve for the fight. That means that Müller is hating himself and will go running for Tam at the first opportunity."

"Tam shall have his chance. The new B. I. 6 is ready and Tam shall have it."

Now every airman knows the character of the old B. I. 5. She was a fast machine, could rise quicker than any other aeroplane in the world. She could do things which no other machine could do, and could also behave as no self- respecting aeroplane would wish to behave. For example, she was an involuntary "looper." For no apparent reason at all she would suddenly buck like a lunatic mustang. In these frenzies she would answer no appliance and obey no other mechanical law than the law of gravitation.

Tam had tried B. I. 5, and had lived to tell the story. There is a legend that he reached earth flying backward and upside down, but that is probably without foundation. Then an ingenious American had taken B. I. 5 in hand and had done certain things to her wings, her tail, her fuselage and her engine and from the chaos of her remains was born B. I. 6, not unlike her erratic mother in appearance, but viceless.

Tam learned of his opportunity without any display of enthusiasm.

"A' doot she's na guid," he said. "Captain Blackie, sir-r, A've got ma ain idea what B. I. stands for. It's no complimentary to the inventor. If sax is better, than A'm goin' to believe in an auld sayin'."

"What is that, Tam?"

"'Theer's safety in numbers,'" said Tam, "an' the while A'm on the subject of leeterature A'd like yeer opinion on a vairse A' made aboot Mr. MacMuller."

He produced a folded sheet of paper, opened it, and read,

"Amidst the seelance of the stars

He fell, yon dooty mon o' Mars.

The angels laffit

To see this gaillant baird-man die.

'At lairst! At lairst!' the angels cry,

'We've ain who'll teach us hoo to fly—

Thanks be, he's strafit!'"

"Fine," said Blackie with a smile, "but suppose you're 'strafit' instead?"

"Pit the wee pome on ma ain wreath," said Tam simply; "'t 'ill be true."

ON the earth, rain was falling from gray and gloomy clouds. Above those clouds the sun shone down from a blue sky upon a billowing mass that bore a resemblance to the uneven surface of a limitless plain of lather. High, but not too high above cloud-level, a big white Albatross circled serenely, its long, untidy wireless aerial dangling.

The man in the machine with receivers to his ears listened intently for the faint "H D" which was his official number. Messages he caught— mostly in English, for he was above the British lines.

"Nine—Four... Nine—four ... nine—four," called somebody insistently. That was a "spotter" signaling a correction of range, then... "Stop where you are ... KLBQ... Bad light... Signal to XO 73 last shot... Repeat your signal ... No... Bad light... Sorry—bad light... Stay where you are..."

He guessed some, could not follow others. The letter-groups were, of course, code messages indicating the distance shells were bursting from their targets. The apologies were easily explained, for the light was very bad indeed.

"Tam... Müller... Above... el."

The man in the machine tried the lock of his gun and began to get interested.

Now his eyes were fixed upon the rolling, iridescent cloud-mass below. From what point would the fighting machine emerge?

He climbed up a little higher to be on the safe side. Then, from a valley of mist half a mile away, a tiny machine shot up, shining like burnished silver in the rays of the afternoon sun, for Tam had driven up in a drizzle of rain, and wings and fuselage were soaking wet.

The watcher above rushed to the attack. He was perhaps a thousand yards above his enemy and had certain advantages—a fact which Tam realized. He ceased to climb, flattened and went skimming along the top of the cloud, darting here and there with seeming aimlessness. His pursuer rapidly reviewed the situation.

To dive down upon his prey would mean that in the event of missing his erratic moving foe, the attacker would plunge into the cloud fog and be at a disadvantage. At the same time, he would risk it. Suddenly up went his tail. But Tam had vanished in the mist, for as he saw the tail go up, he had followed suit, and nothing in the world dives like a B. I. 6.

No sooner was he out of sight of his attacker than he brought the nose of the machine up again and began a lightning climb to sunshine. He was the first to reach "open country" and he looked round for Müller.

That redoubtable fighter reappeared in front and below him and Tam dived for him. Müller's nose went down and back to his hiding-place he dived. Tam corrected his level and swooped upward again. There was no sign of Captain Müller. Tam cruised up and down, searching the cloud for his enemy.

He was doing three things at once: He was looking, he was fitting another drum to his gun, and he was controlling the flight of his machine, when "chk- chk-chk" said the wireless, and Tam listened, screwing his face into a grimace signifying at once the difficulty of hearing, and his apprehension that he might lose a word of what was to follow.

"L Q—L Q," said the receiver.

"Noo," said Tam in perplexity, "is 'L Q' meanin' that A' ocht to rin for ma life or is it 'continue the guid wairk'?"

Arguing that his work was invisible from the earth and that a more urgent interpretation was to be put upon the message, he turned westward and dived; not, however, before he had seen over his shoulder a dozen enemy machines come flashing up from the clouds.

"Haird cheese!" said Tam; "a' the auld cats aboot an' the wee moosie's awa'!"

He had intended going home, but a new and bright thought struck him. He turned his machine and pushed straight through the cloud the way he had come. He knew they had seen him disappearing and, airman like, they would remain awhile to bask in the sunlight and "dry off."

As a general rule Tam hated clouds. You could not tell whether you were flying right side up or upside down, and he had always a curious sense of nervousness that he would collide with something. Yet, for once, he drove through the swirling "smoke" with a sense of joyous anticipation, and presently began to rise gently, keeping his eyes aloft to detect the first thinning of the fog. Presently he saw the sunlight reflected on the upper stratas and began to climb steeply. His machine ripped out into the sun, a fierce, roaring little fury.

Not a hundred yards away was a fighting machine.

"Ticka—ticka—ticka—ticka—tick!" said Tam's machine-gun.

Tam's staring blue eyes were on the sights—he could not miss. The pilot went limp in his seat, the observer took his hand from his gun to grip the controls. Too late; the wide-winged fighter skidded like a motorbus on a greasy road and fell into the clouds sideways.

But now the enemy was coming at him from all points of the compass.

"Dinna let oor pairtin' grieve ye!" sang Tam and dropped straight through the clouds into the rain and a dim view of a bedraggled earth.

"There's Burley," said Blackie, clad in a long oilskin and a sou'wester as he checked off the home-coming adventurers. "Do you ever notice how his machine always looks lop-sided? There's Galbraith and Mosen—who's that fellow on the Morane? Oh, yes, that's Parker-Smith. H'm!"

"What's wrong?"

"Where's Tam—I hope those beggars didn't catch him— There he is, the devil!"

Tam was doing stunts. He was side-slipping, nose-diving and looping —he was, in fine, setting up all those stresses which a machine under extraordinary circumstances might have to endure.

"He always does that with a new machine, sir," said Captain Blackie's companion. "I've never understood why, because if he found a weak place, he'd be too dead for the information to be of any service to him."

Later, when Tam condescended to bring himself to earth, Blackie asked him.

"Why do you do fool stunts, Tam? The place to test the machine is on the ground?"

"Ye're wrong, sir-r," said Tam quietly; "the groond's a fine place to test a wee perambulator or a motor-car or a pair of buits—but it's no' the place to test an aeroplane. The aeroplane an' the submarine maun be tried oot in their native eelements."

"But suppose you did succeed in breaking something— and you went to glory?"

"Aye," said Tam quietly, "an' suppose A'm goin' oop wi' matchless coorage to save ma frien's frae the ravishin' Hoon an' ma machine plays hookey? Would it no' be worse for a' concairned, than if A' smash oop by mesel'?"

"Did you see Müller?"

"In the clouds. A' left him hauldin' a committee-meetin', Captain MacMuller in the cheer.

"'Resolvit,' says the cheerman, 'that this meetin', duly an' truly assembled, passes a hairty vote o' thanks to Tam o' the Scoots, the Mageecian o' the Air-r, for the grand fight he made against a superior enemy— Carried.

"'Resolvit,' says the cheerman, 'that we'll no' ta' onny more risk, but confine oor attentions to strafin' spotters—'

"Carried wi' acclaimation. The meetin' then adjoorned to enquire after machine noomber sax, eight, sax, two, strafed in the execution of ma duty."

It seemed almost as though Tam's words were prophetic, for the next day Smyth and Curzon were attacked whilst "spotting" for the "heavies" and fell in flames in No-Man's Land. They got Smyth in during the night and rushed him back to a base hospital; but Curzon was dead before the machine reached the ground.

The same morning Tam read in the German "Official":

"In the course of the day Captain Müller shot down his thirtieth enemy aeroplane, which fell before the English lines."

"It were no' the English lines, but the Argyll an' Sootherland Hielanders' lines," complained Tam. "Thairty machines yon Muller ha' strafit. Weel, weel!"

He went to his room very thoughtful, and the day following, being an "off" day, he spent between the machine-shop and the hangar where the B. I. 6 reposed. It must never be forgotten that Tam was a born mechanician. To him the machine had a body, a soul, a voice, and a temperament. Noises which engines made had a peculiar significance to Tam. He not only could tell you how they were behaving, but how they would be likely to behave after two hours' running. He knew all the symptoms of their mysterious diseases and he was versed in their dietary. He "fed" his own engines, explored his own tanks, greased and cleaned with his own hands every delicate part of the frail machinery.

There was neither strut nor stay, bolt nor screw, that he did not know or had not studied, tested or replaced. He cleaned his own gun and examined, leather duster in hand, every round of ammunition he took up. He left little to chance and never went out to attack but with a "plan, an altairnitive plan an' —an open mind."

And now since Müller must be settled with, Tam was more than careful.

The difficulty about aeroplanes is that they look very much like one another. Tam fought indecisively three big white Albatross machines before a Fokker hawk darted down from the shelter of a cloud-wraith and revealed itself as the temporary preoccupation of Captain Müller.

The encounter may be told in Tam's own words.

"I' the ruthless pairsuit of his duty, Tam was patrollin' at a height o' twelve thoosand feet, his mind filled wi' beautifu' thochts aboot pay-day, when a cauld shiver passes doon the dauntless spine o' the wee hero. 'Tis a preemonition or warnin' o' peeril. He speers oop an' doon absint-mindedly fingerin' the mechanism of his seelver-plated Lewis gun. There was nawthing in sicht, nawthing to mar the glories of the morn. 'Can A' be mistaken?' asks Tam. 'Noo! A thoosand times noo!' an' wi' these fatefu' wairds, he began his peerilous climb. Maircifu' Heavens! What's yon? 'Tis the mad Muller! Sweeft as the eagle fa'ing upon his prey, fa's MacMuller, a licht o' joy in his een, his bullets twangin' like hairp-strings. But Tam the Tempest is no' bothered. Cal-lm an' a'most majeestic in his sang-frow—a French expression —he leps gaily to the fray—an' here A' am!"

"But, Tam," protested Galbraith, "that's a rotten story. What happened after the lep—did you get up to him?"

"A' didna lep oop," said Tam gravely; "A' lep doon—it wis no' the time to ficht—it wis the time to flee—an' A'm a fleein' mon."

That he would deliberately shrink an issue with his enemy was unthinkable. And yet he rather avoided than sought Müller after this encounter.

One afternoon he came to Galbraith's quarters. Galbraith was rich and young and a great sportsman.

"Can A' ha'e a waird wi' ye?" asked Tam mysteriously.

"Surely," said the boy. "Come in—you want a cigar, Tam!" he accused.

"Get awa' ahint me, Satan," said Tam piously. "A've gi'en oop cadgin' seegairs an' A' beg ye no' tae tempit a puir weak body. Just puit the box doon whair A' can reach it an' mebbe A'll help mesel' absintminded. A' came — mon, this is a bonnie smawk! Ye maun pay an awfu' lot for these. Twa sheelin's each! Ech! It's sinfu' wi' so many puir souls in need—A'll tak' a few wi' me when A' go, to distreebute to the sufferin' mechanics. Naw, it is na for seegairs A'm beggin', na this time—but ha'e ye an auld suit o' claes ye'll no be wantin'?"

"A suit? Good Lord, yes, Tam," said Galbraith, jumping down from the table on which he was seated. "Do you want it for yourself?"

"Well," replied Tam cautiously, "A' do an' A' doon't—it's for ma frien', Fitzroy McGinty, the celebrated MacMuller mairderer."

Galbraith looked at him with laughter in his eyes.

"Fitzroy McGinty? And who the devil is Fitzroy McGinty?"

Tam cleared his throat

"Ma frien' Fitzroy McGinty is, like Tam, an oornament o' the Royal Fleein' Coor. Oor hero was borr-rn in affluent saircumstances his faither bein' the laird o' Maclacity, his mither a Fitzroy o' Soosex. Fitz McGinty lived i' a graund castle wi' thoosands o' sairvants to wait on him, an' he ate his parritch wi' a deemond spune. A' seemed rawsy for the wee boy, but yin day, accused o' the mairder o' the butler an' the bairglary of his brithers' troosers, he rin frae hame, crossin' to Ameriky, wheer he foon' employment wi' a rancher as coo-boy. Whilst there, his naturally adventurous speerit brocht him into contact wi' Alkali Pete the Road-Agent—ye ken the feller that haulds oop the Deadville stage?"

"Oh, I ken him all right," said the patient Galbraith; "but, honestly, Tam—who is your friend?"

"Ma frien', Angus McCarthy?"

"You said Fitzroy McGinty just now."

"Oh, aye," said Tam hastily, "'twas ain of his assoomed names."

"You're a humbug—but here's the kit. Is that of use?"

"Aye."

Tam gathered the garments under his arm and took a solemn farewell.

"Ye'll be meetin' Rabbie again—A' means Angus, Mr. Galbraith —but A'd be glad if ye'd no mention to him that he's weerin' yeer claes."

He went to a distant store and for the rest of the day, with the assistance of a mechanic, he was busy creating the newest recruit to the Royal Flying Corps. Tam was thorough and inventive. He must not only stuff the old suit with wood shavings and straw, but he must unstuff it again, so that he might thread a coil of pliable wire to give the figure the necessary stiffness.

"Ye maun hae a backbone if ye're to be an obsairver, ma mannie," said Tam, "an' noo for yeer bonnie face—Horace, will ye pass me the plaister o' Paris an' A'll gi' ye an eemitation o' Michael Angy-low, the celebrated face- maker."

His work was interluded with comments on men and affairs—the very nature of his task brought into play that sense of humor and that stimulation of fancy to which he responded with such readiness.

"A' doot whither A'll gi'e ye a moostache," said Tam, surveying his handiwork, "it's no necessairy to a fleein'-mon, but it's awfu' temptin' to an airtist."

He scratched his head thoughtfully.

"Ye should be more tanned, Angus," he said and took up the varnish brush.

At last the great work was finished. The dummy was lifelike even outside of the setting which Tam had planned. From the cap (fastened to the plaster head by tacks) to the gloved hands, the figure was all that an officer of the R.F.C. might be, supposing he were pigeon-toed and limp of leg.

The next morning Tam called on Blackie in his office and asked to be allowed to take certain liberties with his machine, a permission which, when it was explained, was readily granted. He went up in the afternoon and headed straight for the enemy's lines. He was flying at a considerable height, and Captain Müller, who had been on a joy ride to another sector of the line and had descended to his aerodrome, was informed that a very high-flying spotter was treating Archie fire with contempt and had, moreover, dropped random bombs which, by the greatest luck in the world, had blown up a munition reserve.

"I'll go up and scare him off," said Captain Müller. He focussed a telescope upon the tiny spotter.

"It looks more like a fast scout than a spotter," he said, "yet there are obviously two men in her."

He went up in a steep climb, his powerful engines roaring savagely. It took him longer to reach his altitude than he had anticipated. He was still below the alleged spotter with its straw-stuffed observer when Tam dived for him.

All that the nursing of a highly trained mechanic could give to an engine, all of precision that a cold blue eye and a steady hand could lend to a machine-gun, all that an unfearing heart could throw into that one wild, superlative fling, Tam gave. The engine pulled to its last ounce, the wings and stays held to the ultimate stress.

"Tam!" said Müller to himself and smiled, for he knew that death had come.

He fired upward and banked over—then he waved his hand in blind salute, though he had a bullet in his heart and was one with the nothingness about him.

Tam swung round and stared fiercely as Müller's machine fell. He saw it strike the earth, crumple and smoke.

"Almichty God," said the lips of Tam, "look after that yin! He wis a bonnie fichter an' had a gay hairt, an' he knaws richt weel A' had no malice agin him—Amen!"

"A'VE noticed," said Tam, "a deesposition in writin' classes to omit the necessary bits of scenery that throw up the odious villainy of the factor, or the lonely vairtue of the Mill Girl. A forest maiden wi'oot the forest or a hard-workin' factory lass wi'oot a chimney-stalk, is no more convincin' than a seegair band wi'oot the seegair, or an empty pay envelope."

"Why this disquisition on the arts, Tam?" asked Captain Blackie testily.

Three o'clock in the morning, and freezing at that, a dark aerodrome and the ceaseless drum of guns—neither the time, the place nor the ideal accompaniment to philosophy, you might think. Blackie was as nervous as a squadron commander may well be who has sent a party on a midnight stunt, and finds three o'clock marked on the phosphorescent dial of his watch and not so much as a single machine in sight.

"Literature," said Tam easily, "is a science or a disease very much like airmanship. 'Tis all notes of excl'mation an' question mairks, with one full stop an' several semi-comatose crashes—!"

"Oh, for Heaven's sake, shut up, Tam!" said Blackie savagely. "Haven't you a cigar to fill that gap in your face?"

"Aye," said Tam calmly, "did ye no' smell it? It's one o' young Master Taunton's Lubricatos an' A'm smokin' it for an endurance test— they're no' so bad, remembering the inexperience an' youth o' ma wee frien'—"

Blackie turned.

"Tam," he said shortly, "I'm just worried sick about those fellows and I wish—"

"Oh, them," said Tam in an extravagant tone of surprise, "they're comin' back, Captain Blackie, sir-r—a' five, one with an engine that's runnin' no' so sweet—that'll be Mister Gordon's, A'm thinkin'."

Captain Blackie turned to the other incredulously.

"You can hear them?" he asked. "I hear nothing."

"It's the smell of Master Taunton's seegair in your ears," said Tam. "For the past five minutes A've been listenin' to the gay music of their tractors, bummin' like the mill hooter on a foggy morn—there they are!"

High in the dark heavens a tiny speck of red light glowed, lingered a moment and vanished. Then another, then a green that faded to white.

"Thank the Lord!" breathed Blackie. "Light up!"

"There's time," said Tam, "yon 'buses are fifteen thoosand up."

They came roaring and stuttering to earth, five monstrous shapes, and passed to the hands of their mechanics.

"Tam heard you," said Blackie to the young leader, stripping his gloves thoughtfully by the side of his machine. "Who had the engine trouble?"

"Gordon," chuckled the youth. "That 'bus is a—"

"Hec, sir!" said Tam and put his hands to his ears.

They had walked across to the commander's office.

"Well—what luck had you?" asked Blackie.

Lieutenant Taunton made a very wry face.

"I rather fancy we got the aerodrome—we saw something burning beautifully as we turned for home, but Fritz has a new searchlight installation and something fierce in the way of Archies. There's a new battery and unless I'm mistaken a new kind of gun—that's why we climbed. They angled the lights and got our range in two calendar seconds and they never left us alone. There was one gun in particular that was almost undodgable. I stalled and side-slipped, climbed and nose-dived, but the devil was always on the spot."

"Hum," said Blackie thoughtfully, "did you mark the new battery?"

"X B 84 as far as I could judge," said the other and indicated a tiny square on the big map which covered the side of the office; "it wasn't worth while locating, for I fancy that my particular friend was mobile— Tam, look out for the Demon Gunner of Bocheville."

"It is computed by state—by state—by fellers that coont," said Tam, "that it takes seven thoosand shells to hit a flyin'-man —by my own elaborate system of calculation, A' reckon that A've five thoosand shells to see before A' get the one that's marked wi' ma name an' address."

And he summarily dismissed the matter from his mind for the night. Forty- eight hours later he found the question of A-A gunnery a problem which was not susceptible to such cavalier treatment.

He came back to the aerodrome this afternoon, shooting down from a great height in one steep run, and found the whole of the squadron waiting for him. Tam descended from the fuselage very solemnly, affecting not to notice the waiting audience, and with a little salute, which was half a friendly nod, he would have made his way to squadron headquarters had not Blackie hailed him.

"Come on, Tam," he smiled. "Why this modesty?"

"Sir-r?" said Tam with well-simulated surprise.

"Let us hear about the gun."

"Ah, the gun," said Tam as though it were some small matter which he had overlooked in the greater business of the day. "Well, now, sir-r, that is some gun, and after A've had a sup o' tea A'll tell you the story of ma reckless exploits."

He walked slowly over to his mess, followed by the badinage of his superiors.

"You saw it, Austin, didn't you?" Blackie turned to the young airman.

"Oh, yes, sir. I was spotting for a howitzer battery and they were firing like a gas-pipe, by the way, right outside the clock—I can't make up my mind what is the matter with that battery."

"Never mind about the battery," interrupted Blackie; "tell us about Tam."

"I didn't see it all," said Austin, "and I didn't know it was Tam until later. The first thing I saw was one of our fellows 'zooming' up at a rare bat all on his lonely. I didn't take much notice of that. I thought it was one of our fellows on a stunt. But presently I could see Archie getting in his grand work. It was a battery somewhere on the Lille road, and it was a scorcher, for it got his level first pop. Instead of going on, the 'bus started circling as though he was enjoying the 'shrap' bath. As far as I could see there were four guns on him, but three of them were wild and late. You could see their bursts over him and under him, but the fourth was a terror. It just potted away, always at his level. If he went up it lived with him; if he dropped it was alongside of him. It was quaint to see the other guns correcting their range, but always a bit after the fair. Of course, I knew it was Tam and I somehow knew he was just circling round trying out the new gun. How he escaped, the Lord knows!"

Faithful to his promise, Tam returned.

"If any of you gentlemen have a seegair—"he asked.

Half a dozen were offered to him and he took them all.

"A'll no' offend any o' ye," he explained, "by refusin' your hospitality. They mayn't be good seegairs, as A've reason to know, but A'll smoke them all in the spirit they are geeven."

He sat down on a big packing-case, tucked up his legs under him and pulled silently at the glowing Perfecto. Then he began:

"At eleven o'clock in the forenoon," said Tam, settling himself to the agreeable task, "in or about the vicinity of La Bas a solitary airman micht ha' been sighted or viewed, wingin' his way leisurely across the fleckless blue o' the skies. Had ye been near enough ye would have obsairved a smile that played aroond his gay young face. In his blue eyes was a look o' deep thought. Was he thinkin' of home, of his humble cot in the shadow of Ben Lomond? He was not, for he never had a home in the shadow of Ben Lomond. Was he thinkin' sadly of the meanness o' his superior officer who had left one common seegair in his box and had said, 'Tam, go into my quarters and help yourself to the smokes'?"

"Tam, I left twenty," said an indignant voice, "and when I came to look for them they were all gone."

"A've no doot there's a bad character amongst ye," said Tam gravely; "A' only found three, and two of 'em were bad, or it may have been four. No, sir- rs, he was no' thinkin' of airthly things. Suddenly as he zoomed to the heavens there was a loud crack; and lookin' over, the young hero discovered that life was indeed a bed of shrapnel and that more was on its way, for at every point of the compass Archie was belching forth death and destruction"—he paused and rubbed his chin—"Archie A' didn't mind," he said with a little chuckle, "but Archie's little sister, sir-r, she was fierce! She never left me. A' stalled an' looped, A' stood on ma head and sat on ma tail. A' banked to the left and to the right. A' spiraled up and A' nose-dived doon, and she stayed wi' me closer than a sister. For hoors, it seemed almost an etairnity, Tam o' the Scoots hovered with impunity above the inferno—

"But why, Tam?" asked Blackie. "Was it sheer swank on your part?"

"It was no swank," said Tam quietly. "Listen, Captain Blackie, sir-r; four guns were bangin' and bangin' at me, and one of them was a good one —too good to live. Suppose A' had spotted that one—A' could have dropped and bombed him."

Blackie was frowning.

"I think we'll leave the Archies alone," he said; "you have never shown a disposition to go gunning for Archies before, Tam."

Tam shook his head.

"It is a theery A' have, sir-r," he said; "yon Archie, the new feller, is being tried oot. He is different to the rest. Mr. Austin had him the other night. Mr. Colebeck was nearly brought doon yesterday morn. Every one in the squadron has had a taste of him, and every one in the squadron has been lucky."

"That is a fact," said Austin; "this new gun is a terror."

"But he has no' hit any one," insisted Tam; "it's luck that he has no', but it's the sort of luck that the flyin'-man has. To-morrow the luck may be all the other way, and he'll bring doon every one he aims at. Ma idea is that to-morrow we've got to get him, because if he makes good, in a month's time you won't be able to fly except at saxteen thoosand feet."

A light broke in on Blackie.

"I see, Tam," he said; "so you were just hanging around to discourage him?"

"A' thocht it oot," said Tam. "A' pictured ma young friend William von Archie shootin' and shootin', surroonded by technical expairts with long whiskers and spectacles. 'It's a rotten gun you've got, Von,' says they; 'can ye no' bring doon one wee airman?' 'Gi' me anither thoosand shots,' gasps Willie, 'and there'll be a vacant seat in the sergeant's mess;' and so the afternoon wears away and the landscape is littered wi' shell cases, but high in the air, glitterin' in the dyin' rays of the sun, sits the debonair scoot, cool, resolute, and death-defyin'."

That night the wires between the squadron headquarters and G. H. Q. hummed with information and inquiry. A hundred aerodromes, from the North Sea to the Vosges, reported laconically that Annie, the vicious sister of Archie, was unknown.

Tam lay in his bunk that night devouring the latest of his literary acquisitions.

Tam's "bunk" was a ten-by-eight structure lined with varnished pine. The furniture consisted of a plain canvas bed, a large black box, a home-made cupboard and three book-shelves which ran the width of the wall facing the door. These were filled with thin, paper-covered "volumes" luridly colored. Each of these issues consisted of thirty-two pages of indifferent print, and since the authors aimed at a maximum effect with an economy of effort, there were whole pages devoted to dialogue of a staccato character.

He lay fully dressed upon the bed. A thick curtain retained the light which came from an electric bulb above his head and his mind was absorbed with the breathless adventures of his cowboy hero.