The Fighting Scouts — First Edition, 1919

LIEUTENANT BAXTER was writing letters home and, at the moment Cornish came into the mess-hut, was gazing through the window with that fixed stare which might indicate either the memory of some one loved and absent or a mental struggle after the correct spelling of the village billets he had bombed the night before.

Cornish, who looked sixteen, but was in reality quite an old gentleman of twenty, thrust his hands into his breeches pockets and gazed disconsolately round before he slouched across to where Baxter sat at his literary exercises.

“I say,” said Cornish in a complaining voice, “what the devil are you doing?”

“Cleaning my boots,” said Baxter without looking up; “didn’t you notice it?”

Second-Lieutenant Cornish sniggered. “Quit fooling. I say, what are you writing letters for? Good Heavens, you are always writing letters!”

Baxter withdrew his gaze from the window and went on writing with marked industry.

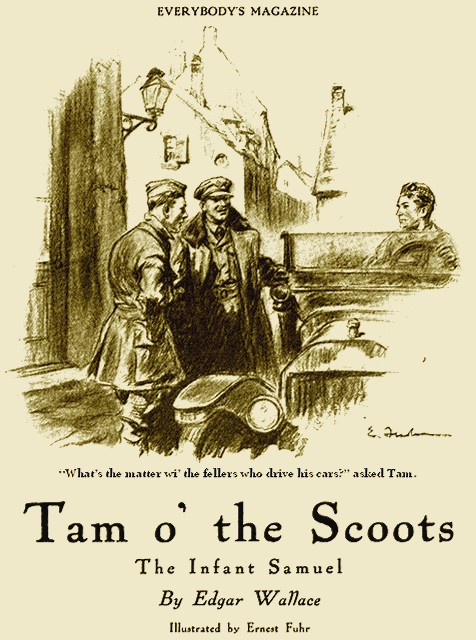

“I say,” said Cornish again, “there was a fellow of the American squadron in here to-day.”

Baxter sighed and put down his pen. “I am told that America is in the war,” he said politely. “This fact would probably account for the phenomenal happening.”

“He asked for rye whisky,” said Cornish, nodding significantly.

“Poor fellow.”

“When I told him that we hadn’t any rye whisky,” Cornish went on, “he asked, whether we weren’t fighting for civilization and the free something or other of peoples.”

Baxter swung round on his chair, his hands folded on his lap. “All this is very fascinating,” he said; “why don’t you write a book about it? And what are you doing here, may I ask? I thought you were going into Amiens?”

“I wish I’d gone,” said the gloomy young man; “it is blowing eighty miles an hour up-stairs. Depledge went up and was buffeted about all over the shop and nearly crashed. Saw a Hun and couldn’t get near him.”

“What was the Hun doing?” asked Baxter, interested in spite of himself.

“That’s the very question Depledge asked me.”

“But you didn’t tell him?” said Baxter. “You’re a reticent devil, Cornish! And now, if you don’t mind my communicating with my fond parents, perhaps you will go out into the garden and eat worms.”

“Oh, that reminds me,” said Cornish: “This American chap, a most excellent fellow, by the way, wanted to know what has happened to Tam.”

“Did you tell him?”

“No,” confessed Cornish.

“Do you know?” asked the patient Baxter.

“No,” admitted Cornish.

Baxter groaned. “Good-by,” he said.

“I say,” said Cornish.

“Good-by,” said Baxter loudly.

“This fellow,” Cornish drawled on in his even, monotonous voice, “this American fellow. I mean, the American fellow I saw this morning—”

“I thought you were speaking about the Spanish fellow you saw yesterday,” said Baxter wearily.

“No, this American fellow said that he had heard that Tam was coming back. Some brass-hat told him.”

“He was pulling your leg, my dear Cornish,” said Baxter; “these Americans stuff people, especially the young and the innocent. Now go to bed or go out and buy me some stamps or take my motor-bike and joy-ride into Amiens or go down to the workshop or—or go to the dickens.”

“You are very unsociable,” said Cornish, and wandered out.

He strolled across to the workshop and stood for a few minutes in that noisy hive watching the mechanics fitting a new tractor screw to his “camel,” then walked back to his quarters through the drizzle.

THE wind was blowing gustily. It slammed doors and sent gray clouds of smoke bellowing from the stove, it rattled the windows and whined and sobbed about the corners of the hut.

Then suddenly above the sigh and moan of it rose a shrill “whee-e-e!”

Cornish was in the act of sitting down as the sound came to him. He checked the action and, half-doubled as he was, leapt for the door and flung it open.

“Wh—oom—oom!”

The force of the explosion flung him back, the windows crashed outward, the ground beneath his feet rocked again.

Even as he fell he heard the shattering of wood where the bomb fragments ripped through the casings of the hut. He was on his feet in an instant and through the door.

High above the aerodrome, appearing and disappearing through the hurrying cloud-ruck, was a machine that swayed and jumped most visibly.

Cornish started at a run as the antiaircraft guns began their belated chorus.

He met Baxter struggling into his padded jacket before his hangar.

“We’ll take a chance,” said Baxter rapidly; “who’d ever imagine the swine would come over on a day like this?”

“Think he’ll come back?” asked Cornish.

The other shouted something unintelligible as he turned to climb into his tiny one-seater and Cornish guessed rather than heard the answer.

Three minutes later he was zooming up behind his superior, his machine dancing like a scrap of paper caught in the wind. The little scout climbed steeply, heading eastward, and Cornish, strapped to his seat, saw nothing but the gray race of cloud above him, until the altimeter registered eight thousand feet. Then he began to take notice.

A little below him and a mile away was Baxter’s machine, while a mile ahead of him and running across his bows was a Hun plane of respectable size and unusual lines. He observed with joy that the enemy was making bad weather of it, and banked round to run on a parallel course.

A rapid glimpse of the country told him that the adventurous enemy was making for home, and the proximity of the machine was probably due to the fact that the bomber had attempted to return against the wind to repeat his good work when he had sighted the chasers.

Baxter’s scout swung round behind the enemy. Cornish closed to his flank. The astonished but interested infantry in the trenches eight thousand feet below, heard above the purr of the engines the “ral-tat-tat-tat-tat!” of machine guns and saw the Boche side-slip. It was a scientific side-slip, wholly designed as an advertisement of the slipper’s distress, but it was not the weather for artful maneuvers. Suddenly the big machine began to spin, not a well-controlled spin, but rather following the motion of a corkscrew driven by a drunken hand.

The two scouts dived for him, their guns chattering excitedly, and the big Hun flip-flopped earthward, nose up, tail up, wing up—till he made a pancake crash midway between the line and the aerodrome of the Umpty-fourth.

Baxter followed and made a bad landing, but the Providence which protects the child was kinder to Cornish, who lit “like a blinking angel,” to quote a muddy and unprejudiced representative of the P.B.I.*

[* The infantry is invariably referred to by all other arms as the “Poor Blooming Infantry.” or words to that effect.—E.W.]

Luck was not wholly against the enemy (for the two German airmen were alive when their machine reached bottom) except that the friendly hands which had strapped them to their seats had done their work a little too effectively. By the time they had freed themselves from restraint, but before they had fired the incendiary bomb which was intended to destroy the machine, Baxter was out of his chaser and was standing on the under-carriage.

“Don’t fire the machine unless you’re awfully keen on a military funeral,” he said, and four gloved hands arose over two leather-helmeted heads.

“Don’t shoot. Colonel,” said the cheerful pilot, “I’ll come down.”

Baxter watched his prisoners descend before he restored his Colt automatic to its holster.

“Sorry and all that sort of thing,” he said to the pilot, “but you’ve got some nerve.”

“Give the barbarian credit for something,” replied the blue- eyed pilot, lighting a black cigar. “I’m afraid my friend here will want a doctor.” He indicated the very young and very pale officer, whose thumb had apparently been shot away. “He doesn’t speak English. My name is Prince Karl of Stettiz-Waldenstein, the last of the ancient race that carries the blood of Charlemagne.”

“Cheerioh,” said Baxter, “come along to our mess and have some lunch before the wolves get you and put you in a little cage. We’ll drop your friend at the hospital—my name, by the way, is Baxter, and I come from a long line of hardware merchants.”

The prince smiled. “Trade follows the flag,” he said. “My little friend’s father makes typewriters—and pretty bad ones. You ought to be friends.”

An R.F.C. picked them up and after depositing the wounded youth at the general hospital, the two foemen were whirled back to the aerodrome, their arrival coinciding with the return of the majority of the squadron from Amiens. The prisoner was talkative and lively. He had been educated at Harvard and Oxford, thought the war was pretty good sport, told a joyous tale of a grand-ducal aunt who had sent him a set of silken underwear embarrassingly embroidered with the legend: “Gott strafe England und America,” but would not offer any information about the machine he was flying.

“You can see what is left of it and discover for yourself,” he said to Major Blackie at parting; “she’s a fairly useful bus, but nothing as useful as she’s supposed to be. Oh, by the way, I nearly forgot to ask—where’s Tam?”

“Tam is in England,” smiled Blackie. “I thought you fellows knew. He got married and went away to be an instructor or something.”

“But surely he’s back,” persisted the other. “One of our circus commanders (you call them circuses, don’t you?) told me he was due back to-day—that was one of the reasons I came over. If the weather had been good we should have come in force!”

“A sort of ‘welcome home,’ eh?”

The prince grinned.

“Well, he isn’t here,” Blackie went on, “and so far as I know—excuse me.”

An orderly stood in the door with a scrap of paper in his hand which Blackie took and read.

“I MUST hurry you off,” he said; “the wind’s dropped and one of your circuses is going up.”

“Good luck to ’em,” said the prisoner as he shook hands.

The circus did not materialize in so far as the squadron was concerned, its activities being exclusively monopolized by certain enthusiastic but half-trained units of the U. S. F. C., which, while on a practise flight, and strictly against all instructions, engaged its more skilful enemy and bluffed it into retreat.

This was discussed among other matters after dinner that night.

“The gentlemen from Indiana got Fritz with his tail down,” said Baxter; “they were out doing a formation stunt with no idea in life save to avoid unpleasantness with their flight commander—it wasn’t a bad formation, by the way—when Fritz and his Imperial Circus butted into the simple children of the West.”

“What happened?”

“It was funny. The gentlemen from Indiana just dropped that formation nonsense. They simply went baldheaded for the nearest Hun and before you could say ‘knife,’ two Huns were spinning out of control and the circus was moving homeward with the United States of America in hot pursuit. It was comic to see the French instructor shooting off frantic recall signals.”

Blackie pulled out his cigar case and contemplated the interior with a look of gloom.

“I wonder why everybody thinks Tam is coming back—the cigars and the Americans remind me.”

“I’ll bet he’s no use for flying—when a chap is married he’s done for,” said a voice in a dark corner.

“Hit him, somebody,” growled Mortimer, the latest of the squadron benedicts. “Come out of your obscurity, Hector Misogynist; oh, it’s Cornish! Bah!”

Cornish came into the light unabashed. “Kipling wrote it about a fellow who wouldn’t take a fence or lead his squadron after he was married—got scared when he thought of his child and all that sort of thing.”

The door opened suddenly and a muffled figure stood in the entrance.

“Waiting patrol!” he barked. “Get up—light, bombing squadron over Corps Headquarters—get a wiggle on!”

A scamper of feet, wails and imprecations from the waiting patrol, a chorus of “Shut that door—damn you!” and the hum of engines outside. A confusion of voices, a more intense roar which dies down to silence, and the night patrol is away.

Blackie looked at his watch. “Simmonds, your flight had better stand by—they don’t usually strafe C. H. Q. There go our Archies—everybody stand by!”

Blackie hurried to his concrete office where a nonchalant telephonist was exchanging philosophy with another telephonist six miles away, and if the distant operator was the less philosophical of the two, he might be excused, since he was at that moment undergoing an aerial bombardment.

“Umpty-eighth bein’ bombed, sir,” reported the telephonist in the same surprised tone you might employ to announce that a football match had been postponed, “the ’Uns ’ave strafed two ’angars.”

“And knocked the H’s off the rest, eh?” said Blackie. “Ask O. Pip* if any of our people have signaled.”

[* Observation post.]

Click! A plug pushed home, a rasping buzz and— “Hello—O. Pip—Hallow! O. Pip. Reports? Right.” He turned. “Night squadron signaled nine thousand feet, sir—makin’ west. Encountered no H.A.”

He said this importantly, since there was a fine roll in “encountered” and a pleasant mystery—which was no mystery to anybody—in the abbreviations for “Hostile Aircraft” and “Observation Post.”

Baxter came back ten minutes later to report and inquire. “They seem to be leaving us alone, which is strange, after what that prince person said.”

“Apparently they are after the gentlemen from Indiana, who, I suppose, will be gnashing their teeth at their good kind instructor because he won’t let them go up in the dark, dark night.”

“We’re a cheerful lot of boys,” said Baxter. “Who called them the gentlemen from Indiana, by the way?”

“Tam,” said Blackie laughing; “he’d read a book with a title like that—Indiana was the word that took Tam’s fancy.”

“Hello—hello—yes—speak up, Clarence—bombin’ yer, are they—all right.” The operator half turned. “Bombing Squadron H. A. operatin’ over American Squadron H. Q., sir; one ’angar slightly damaged.”

Blackie nodded.

“Hello! Yes—one H. A. forced to descend by Archie fire, sir.”

Blackie nodded again. “They’re out to-night with a vengeance,” he said; “every bombing squadron Fritz has must be working.”

“Headquarters call, sir,” reported the telephonist and slipped the apparatus from his head.

Blackie sank into the seat vacated and adjusted the ear-pieces. “Yes—Umpty-fourth—yes, sir, Blackie speaking. Yes—they seem lively, yes, sir—(check this, Baxter) twelve machines to escort 947th and 958th squadrons on a bombing raid to be in the air at five aco-emma! (Got that, Baxter?) Yes, sir.”

He hung up the receiver. “Reprisals by order—wind up at D.H.Q.—slow music and death to the sleep-destroying Hun!”

WITH the dawn the escorting squadrons rose to their station, and Blackie from the ground saw the flicker of blue and green lights as the British bombing machines came over and their escort fell into place.

The drone of their engines had hushed to an intermittent buzz when Blackie strolled across the aerodrome to the deserted mess-room for his morning cup of tea.

The sergeant-major who walked at his side was expressing the gloomy views on the weather which sergeant-majors are permitted to hold, when he suddenly stopped talking and stood still.

“What’s the matter, Sergeant-major?” demanded Blackie.

“Somethin’ comin’ our way, sir.”

Blackie listened.

The sound of airplane engines which had almost died away was again audible.

“They’re not coming back?”

Blackie listened with a puzzled frown.

The noise rose from throb to buzz, from buzz to angry purr.

“’Uns,” said the sergeant-major’ sapiently. “That’s a circus—look, Sir!” He pointed eagerly. Twelve thousand feet above, the rays of the yet invisible sun caught the white wings of the enemy squadron. Tiny flecks that glittered in the dawn light and unmistakably hostile.

“Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom!”

“Pang! Pang! Pa-pa-pang!”

The sleepless Archies were at work and the skies were full of wailing.

“Oh, damn!” snapped Blackie, “every one of my machines up! Bomb-proof shelter for us, I think, Sergeant-Major.”

But the sergeant-major was staring at the skies. The big German formation so perfectly alined had suddenly broken. “The leader’s in trouble, sir.”

No need to say as much, for the leader was sweeping earthward in wide circles.

“Ticka-tacka, ticka-tacka!”

“Machine gun—what the dickens is wrong with ’em?”

A second machine fell out of formation, disastrously blazing. The formation was now confused and scattered. Three machines had banked over and turned for home. Another three—obviously fighting machines—were circling and the fierce chatter of their guns was eloquent of their annoyance.

“But what are they fighting—one another?” demanded the mystified Blackie. “None of our people are up—glory be! There goes another!”

One of the attackers crumpled and broke in the air and spun earthward.

Then Blackie saw.

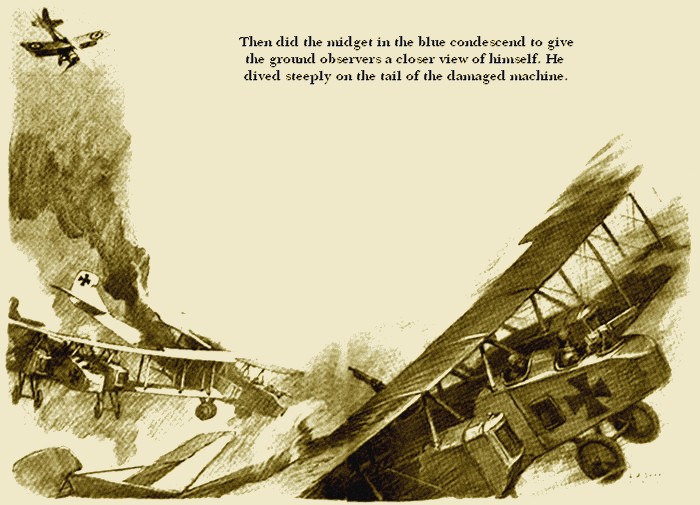

High above what had once been a formation was poised an airplane of microscopic size. It was a pin-point of light in the skies, so tiny that Blackie could not believe the evidence of his eyes until the circus turned homeward, one machine, obviously damaged and losing height with every yard it traveled, lagging in the rear.

Then did the midget in the blue condescend to give the ground observers a closer view of himself. He dived steeply on the tail of the damaged machine. They heard the splutter of his gun and saw the lame duck crash.

“But what is it—Sergeant-Major? Good Lord, it’s as big as a large-sized hat-box.”

The tiny stranger wheeled round, poised for a moment and then began a glide for the aerodrome.

As it drew nearer Blackie saw that his estimate of its size was not an extravagant one. It might be stowed in a big packing-case and might with no discomfort take shelter under the wing of a Handley-Page.

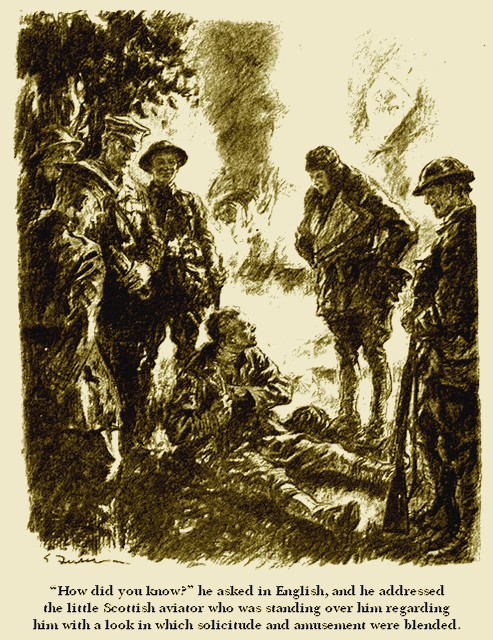

The midget lit lightly at the far end of the aerodrome, and Blackie ran to meet the visitor as he stepped down the few feet which separated the nascalle from the ground.

“I say, I’m awfully grateful to you, but from what toy-store did you dig out this contraption?”

The pilot shed his furry gloves and lifted the mica-eyed mask that hid his face before he spoke.

“A’ll be thankin’ ye, Major Blackie, sir, if ye’ll no speak disrespectfully of ma wee frien’, ‘Annie Laurie,’ the pride o’ Scotland an’ the terror o’ the Hoon.”

“Tam!” yelled Blackie, and gripped the scout by the shoulders. “Tam! You melodramatic humbug! You villain! Back again!”

“From ma honeymoon,” said Tam, shaking his head, “an’ just as I were gettin’ used to it—mon, war’s hell—have ye a seegair in your pooch—A’m travelin’ wi’oot ma baggage!”

WHEN the Grand Duke of Friesruhe, son of a Most Exalted and Princely House, heir to Wilhelm XXVI of Friesruhe, beloved nephew of a Kaiser and a Czar and Colonel of the Third Regiment of the Prussian Guard, expressed his august desire to become a flying officer, permission was immediately given and instructions were issued to the Commander of the Sixty-fourth Corps District (wherein the Duke was stationed) that his Serene Highness was to be allowed to enroll himself a member of the Flying Service, might be photographed in the uniform, might indeed accompany a considerably experienced and trustworthy expert on a ground trial, providing (a) the weather were propitious, (b) the reliability of the machine had been thoroughly tested, (c) staff photographers were present, but that he must not be allowed to fly.

Whereupon the Grand Duke of Friesruhe, who was quite a nice youth, lay low, mastered the technique of the airplane with great assiduity, and on a certain day which was not propitious in the matter of weather, and in a borrowed machine which was notoriously unreliable, climbed to twelve thousand feet alone and unaided in the full view of a pallid staff, which alternately prayed and swore. In the language of court circles it was an “escapade” and the matter did not become serious until the Duke insisted upon becoming a real pilot, whereupon he was summoned to Grand Headquarters and was lectured on obedience by the Most All Highest and Then Some.

He listened to the lecture in silence, standing rigidly at attention, and went back to his principality. Within three days the socialistic Arbeiter-Zeitung published in his city began a violent agitation for Peace at Almost Any Price, and since the Grand Duke was known to be behind the Friesruhe Arbeiter-Zeitung, and the succession to the throne was secure, Grand Headquarters reversed its decision, gave him full authority to break his neck and requested that the Arbeiter-Zeitung should be subjected to Preventive Censorship.

So the Duke went joyously to the front, and the Arbeiter-Zeitung explained that what it really craved for was a Peace with Annexations and Very Large Indemnities.

That is the true story of how Colonel, the Grand Duke of Friesruhe came to be an air fighter and eventually leader of what was known on the British, French and American fronts as “The Duke’s Museum.”

It differed from the recognized circuses in this respect: It consisted of two flights of five machines each, and those machines were more or less freakish. All the new types of airplane that ever came to the German army were first tried out by the Museum—and in the most freakish of all it was certain that the Duke himself would be found. The Duke was the first to fly a Fokker, the first to handle a Gotha; he was the very father-in-law of the Friedrichshafen, and the comparatively successful and the comparatively useless types he handled were legion.

The cry of, “Here’s the blinkin’ Museum comin’!” was sufficient to empty the dugouts and bring even battalion headquarters recklessly into the open to watch twelve “machines—assorted,” twelve different types of different speed and varying military values, come staggering across the sky—aerial infants learning to walk.

They were protected. High above drove the jealous scouts, buzzing like bees and relatively as large.

Many and fierce were the battles fought and many were the specimens from the Museum that crashed behind the German lines. But the Duke remained, and presently, on some fine day, our scouts would see him at the head of a straggling line of new and even more eccentric machines.

This new interest had come during the absence in England of Second Lieutenant Tam of the Scouts, and his first acquaintance with the Museum was when, returning from a reconnaissance, he barged into the ragged formation and was greeted (from the ground) by a protective barrage of “flaming onions”—the onion being a highly inflammable rocket which it is unpleasant to meet. He did not stop to investigate, having certain photographic plates which needed urgent development.

“’Twas no’ a sense of duty that brought me oot a’ ma coorse,” reported Tam to his chief as they sat in the mess that night. “’Twas no’ the quickenin’ pulse of ma fichtin’ ancestors—’twas the instinct that makes a wee boy push his way into the crood that surroun’s a lad in a fit. Mon! but A’m keen on gettin’ a squaint at the Airchduke.”

“Grand Duke,” corrected Blackie; “Archdukes are Austrian.”

“’Tis the same, Major Blackie, sir,” said Tam calmly; “Airchdukes are the grandest dukes in Austria—A’m studyin’ the subject of dukes the noo. There’s a bonnie book just come to me frae ma—frae a friend o’ mine” (he never spoke, save in this cautious fashion, of the pretty and vivacious little American girl he had married, and who was now living in Devonshire and watching with apprehension every messenger-boy who carried a telgram); “’tis a wonderful book an’ must have cost twa dollars.”

“Eight shillings,” corrected the youthful “ace” Bagley.

“Twa dollars, ma friend,” said Tam, “an’ less than eight shillin’s, for the currency of ma adopted country is fine an’ healthy. Well, noo, why do you interrupt me? This book is aboot war in the days before flyin’ machines. They were gay times. When a commander led his flight o’er the enemy’s line, he just cranked up his one-seated chairger, filled his petrol-tank wi’ beer and whusky—accordin’ to whether he was a squire mechanic or a knight obsairver—took a good grip of a ten-foot joystick an’ said to his wee page—‘Contact—let her rip, Alec;’ an’ off he’d zoom across the wairld, not carin’ whether it snowed. An’ when he met a Hun he’d ficht and ficht till he crashed him an’ cut off his heid. Then by rights all the golden airmor of the Hun was his. Or, if he just brought him doon oot of control, he’d put him in a cage an’ say, ‘Yon feller’s ma pairsonal property—his relations can buy him back for ten thousand rose-nobles.’”

“You could buy the earth and Paris if you held your prisoners to ransom, Tam,” said Blackie.

“A’m no’ so sure,” said Tam, shaking his head; “’tis only the men-at-airms an’ the young squires A’ve pinched, wi’ an occasional baron—but barons are nothin’ in Gairmany. Every Hun A’ve brought doon so far A’ve called ‘Baron,’ an’ the only mistake A’ve made was when A ought to have said ‘Coont’ or ‘Prince.’ There are more barons in Gairmany than there are second loots in the British Army—they’re as plentiful as Very lights on a strafe night. Suppose A held a baron to ransom, an’ suppose A got through a letter to his family Slosh or Schloss, sayin’—’Dear Sair or Madame: A have found a baron bearin’ your name an’ address. Kindly send ransom for same in strictest confidence.’ What d’ye think A’d get? A ten-cent postal stamp?”

“Get the Duke, Tam, and earn promotion,” said Blackie, “he smokes the finest cigars of any man in Germany and his pockets are usually filled with them.”

“He’s a deid mon!” said Tam.

But a grand duke takes a lot of killing.

Tam, patrolling from Gx. 971. A. to Tm. 141 Q (you will search in vain for this hideous disguise of the limits of the Saarville district), came into contact with a flying formation which he at first identified as von Bissing’s circus, usually to be found in this region. Closer inspection, however, revealed the fact that the formation was made up of “job lots” and Tam disappeared into the base of a cumulus and circled through the thick mist to pass the time which must elapse before the Museum came within fighting distance. It had been heading his way and so also had the overhead escort—five famous air-fighters formed the guard of honor.

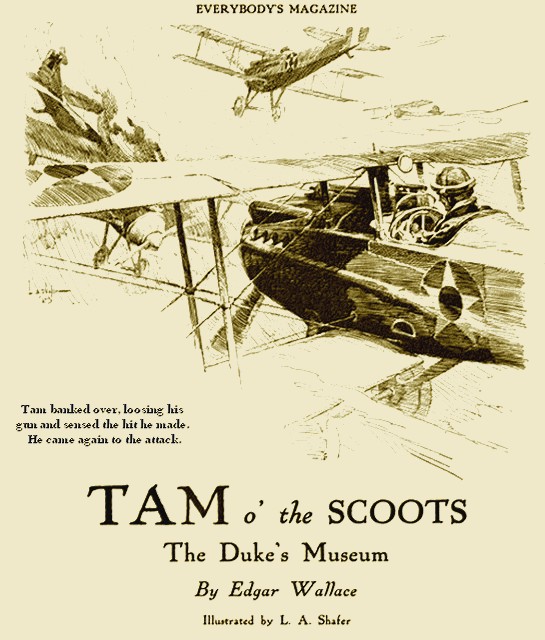

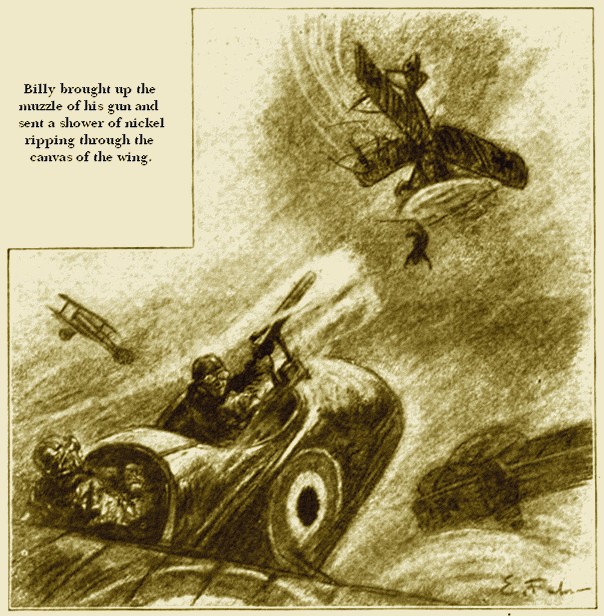

Tam skimmed lower and lower until only the thinnest veil of mist separated him from the Grand Ducal Squadron. He judged them to be fifteen hundred feet beneath when he dived straight into the center of the formation.

Airplanes do not emit a startled squeal or roll up the whites of their eyes or shriek for help, but they have a way of illustrating emotion. They scattered and dived, some to the east, some to the north—all except, one, a new Alto-Albatross that pushed its nose up to meet the droning fury.

It was to this machine that Tam directed his attention. He passed the Albatross in a flash, something snapped behind him and a wire stay dangled loosely. He looped back to secure some of the height he had lost, but the Duke was quicker and had maneuvered for the attacking position. Tam banked over, loosing his gun and sensed the hit he made. He came again to the attack, half-circled his enemy, now enveloped in smoke, let fly another fusillade and dropped steeply for earth. Tam did not look up to discover what the German escort was doing. He knew. He dropped because he calculated that at that moment five angry machines, piloted by most redoubtable fighters were driving for him.

He fell for the cover which the flying British Archie gives to airmen in distress, but the five fell with him, for the machine of a Most Exalted Person was smoking and burning in mid-air, and each and every one of the five would be held accountable for any change in the succession to the throne of Friesruhe.

THE Seventy-ninth Patrolling Flight of the United States Army witnessed these deeds from afar off and consumed with morbid curiosity came down from their lofty plane to investigate—and the chase ended.

It was the flight commander who reported, subsequently, that the Duke’s machine had made a good landing.

“A’m hopin’ the Duke was no’ burned,” said Tam, “that would be an awfu’ waste o’ good seegairs.”

The Duke was no’ burned. His incomparable Museum and Exhibiton of Mechanical Marvels and Magical Air-Conquering Apparatus paraded the Ypres front that same week with the greatest eclat, but this time (according to the report of the Umpty-ninth Squadron R.F.C. supported by the veracious “gulls” of the Royal Naval Air Service) the number of the escort was such that they darkened the sky.

The commander of the Umpty-first complained bitterly that he had lost three machines because of “this infernal obstruction” in the skies.

His machines had been good-natured bombers which were homewardly plodding their weary way, after dropping about three tons of high explosives on Roulers railway station, when they had fallen in with the Museum and its board of trustees, and three pedigreed Page machines were sorely stricken and now lay somewhere in Flanders.

Then one day, a message came through to four fighting squadrons.

“This Museum business is getting on the nerves of G.H.Q.,” said Blackie to his assistant.

“What’s wrong, sir?” asked that youth.

“The Museum is to be found and smudged out—its aerodrome is to be bombed at every opportunity and the Duke must be crushed.”

Lieutenant Baxter whistled. “That’s not like G.H.Q.,” he said, “that black-hand stuff. What has the poor old Duke been doing?”

Blackie shook his head. “God knows,” he said, “but it is something fierce to stir up G.H.Q.—the American and French squadrons have had the same instructions.”

He opened a steel safe and took out from a drawer which he unlocked, a long yellow envelope which had been heavily sealed. From this he extracted a slip of paper on which were written about eight lines of handwriting.

“Send Tam to me,” he said.

Tam was in the middle of a long composition designed for his “friend,” embellished at unexpected intervals with those poems which only Tam could write. He hastily locked away his letter and hurried across to the orderly room.

“Shut the door, Tam,” said Blackie—and when this was done—”what I tell you now is in absolute confidence. To-morrow we start sending out to find the Duke and he is to be brought down, if possible, within our lines. If that is not feasible, he must be crashed, and by crashed I mean his machine must be destroyed. You will tell your flight no more than this, that if necessary, you must engineer a collision in mid-air—in fact, ram him.”

“Aye, sir,” said Tam, gravely nodding.

“I don’t know why this order has come out, but it is a very special and confidential instruction. These measures are not to be put into movement until”—he consulted the paper again—“‘twelve o’clock noon on the eighteenth’—that’s to-morrow.”

Tam saluted and departed.

“What do you make of it, sir?” asked Baxter.

“I hardly know,” replied Blackie slowly; “but from what some of the Huns we have captured say I rather fancy we have been underrating the Duke. He is one of the best, boldest and most inventive flyers in the German service. He has tried out every good machine they have had, and has made them practicable for general service. I rather fancy the big escort is more to protect him in his experiments than to save his blue blood from spilling. Remember, all his flights are carried out under war conditions.”

“But what are the rest of the Museum?” asked Baxter.

“That apparently is camouflage to hide the fact that the machine that is being tried out is the one which the Duke is flying—you remember we used to do the same thing when poor Hall was alive. Hall perfected the Wingate Stabilizer at twelve thousand feet under Archie fire; he improved our bomb sights while actually circling over Treves. I rather suspect that the Duke is a genius of a similar order.”

AT twelve o’clock the next day, punctually to the second, the Museum came into sight to the east of St. Quentin. It consisted of ten machines flying in V-shape formation, and as usual no one machine was like another. At the apex of the V was a monoplane with an unusually long nacelle, an unusually long and remarkably narrow wing spread.

The observers, through their telescopes, reported that there was nothing more remarkable than the fact that the monoplane, in spite of its high engine power, did not lose place but maintained its position even though its companions were obviously more antiquated “buses,” but most remarkable of all was the report which came through Lieutenant Gordon T. Simms, an observer of the U..S. Air Service, an extract from whose report may be quoted:

“Until engaged by enemy patrols, I had an uninterrupted view of the enemy formation, which was led by a large monoplane resembling in appearance the old Antoinette, which acted as leader. At a distance of a mile or more I saw the Antoinette machine slow until it almost stopped, the remainder of the formation passing on until ten seconds later the formation had advanced leaving the Antoinette well in the rear. It had the appearance of being almost stationary for half a minute, at the end of which time it went forward again at great speed, and took its place at the head of the formation. In the position from which I observed this, it was impossible that I could be the victim of an optical illusion.”

Air experts are equally emphatic that it is impossible that an airplane can stand still without losing height. The man who invented such a machine or a pilot who could employ mechanism to produce that result would very nearly solve the last problem of aviation.

At three o’clock in the afternoon, the Museum was seen following the line of the Scarpe in a southwesterly direction, escorted by twenty battle-planes in two formations of ten. The escort was attacked by the 904th, the 623d and the 612th squadrons of the British, and by the 120th and 121st flights of the U. S. Air Services, and by de Mouleys’ famous squadron of “aces”; and the battle which raged in the air has come to be historic. Fourteen German airplanes were crashed or driven down out of control and three British and one French. But in the course of the fighting the Museum got away. Again the report came through that the Antoinette had distinctly slowed her pace until she was almost at a standstill.

Following this, three British bombing squadrons raided the aerodrome where the Museum was known to reside, and dropped particularly powerful bombs upon the underground hangars—ignoring the inviting array of matchwood sheds which the Germans had erected to draw the fire of raiders.

On the twenty-first, the Museum, with the inevitable Antoinette at its head, but this time made up of much faster machines, came over the British lines and was attacked by the defensive squadrons, four of the Museum dying the death before their guardians could come to their assistance.

Again the Antoinette escaped, and bitter were the words which came humming along the wire which connected G.H.Q. with the squadrons concerned. There was a great ringing of telephone bells, and secret discussions in locked offices where eminent officers consulted in Hindustani, to the intense annoyance of the military exchange.

At eight o’clock, Blackie walked into Tam’s quarters, locked the door behind him, took from his pocket a map and a large-caliber pistol of unfamiliar pattern.

Without any preliminary he began:

“The Antoinette is at the Gisors aerodrome—the experimental aerodrome to the north,” he said. “We are not taking any chance with a bombing squadron. The hangar is certain to be underground. Here is a signal pistol we took from one of the Museum machines that crashed. It is loaded with a cartridge which shows a red and green light. That is the landing signal for this particular aerodrome.”

Tam waited.

“G.H.Q. has heard about you and they want you to make a landing. You will probably be shot if you are caught. Here you are,” he spread the map and laid his finger upon a green patch; “that is a fairly level plain about two hundred yards from the aerodrome. Land there and get into the hangar as well as you can. You will destroy the machine.”

“And they will make anither,” said Tam.

Blackie shook his head.

“It will take them nine months to make another like it,” he said. “I have seen the Director of Intelligence. He tells me that this Antoinette is being perfected in the air, and, that the Duke is the only man that can fly it so far. You may not be able to get back to your machine,” he went on, “but you must take the risk. Only use the landing light if they get an Archie barrage on you.”

He shook hands and walked abruptly away. He was sending his best man to his death, and. anything he might say, now, would be feeble and inadequate. Tam looked at the map and looked at the pistol, opened his desk and took out the letter which he had just finished writing.

He added this P.S.:

“I’ll be awa’ to make a call on another aerodrome. Tam.”

TO the north of Gisors is a small aerodrome consisting of about half a dozen flimsy huts and three underground hangars which are approached by broad sloping runways. The hangars themselves are protected by nine feet of sandbagging and so elaborately camouflaged that it would be impossible to detect from the air either the runway or the bulge of earth which corresponded to the roof of the underground chambers.

In one of these were three men, two of them officers, one an old and spectacled mechanic in field-gray. The hangar was brilliantly illuminated with ground, roof and wall lights, so that there was not one bit of the long and dainty machine which stood in the center of the hangar that was not flooded with light.

THE younger of the officers and, if the truth be told, the least distinguished was, contrary to all regulations, smoking a long thin cigar and eyeing the machine with knitted brows. The second of the officers, an older man and one of higher rank, was shaking his head in admiration.

“Your Highness has performed a miracle,” he said; “this will rank as one of the greatest mechanical discoveries of the war.”

It was the younger man’s turn to shake his head. “Not yet, von Grosser,” he said sharply; “you are premature. Perhaps in a month we may reduce the thing to a formula. At present I am making new discoveries every day.”

He walked slowly around the machine. There was nothing extraordinary in its appearance save that, in addition to the tractor screw in front, it carried a small propeller behind the driver’s seat, a propeller which was fitted at a curious angle.

“Von Missen is very anxious to make a flight in her,” said the older officer. “I think he has recently arrived. I saw his landing lights a few moments ago.”

“Von Missen is a fool,” said his Highness, “and he would be a dead fool if he essayed it. Three times she has failed, for some reason I can not understand. But I shall get it right,” he nodded; “yes, I shall get it right. If—”

“If?” repeated von Grosser.

“If the people over there,” he jerked his head to the west, “don’t get me.”

Von Grosser laughed. “Your Highness may be assured that that will never happen,” he said; “they have tried and failed. They have bombed every aerodrome between here and St. Quentin. Why,” he shrugged, “I do not know.”

“Because they know, my friend, that if they get me, this machine—”

He was looking at Colonel von Grosser as he spoke. The Colonel was facing the narrow entrance which admitted into the hangar when the great sliding doors were closed and he saw the other’s eyebrows rise and a comical look of incredulity and annoyance dawn upon his face.

“What—”

“Hands up, all of ye!”

A figure stood in the doorway, his face half hidden by the mica goggles he still wore, puffed and padded from head to foot in a soiled yellow leather jacket.

“Come oot o’ that,” said Tam, “come oot, uncle!” He waved the frightened mechanic to the far wall, “which of ye is the Airchduke?” he demanded.

The younger man laughed. “I am the Grand Duke of Friesruhe,” he said; “if I am the person you are seeking?”

“And is that yer fine machine?” said Tam.

“That’s my fine—”

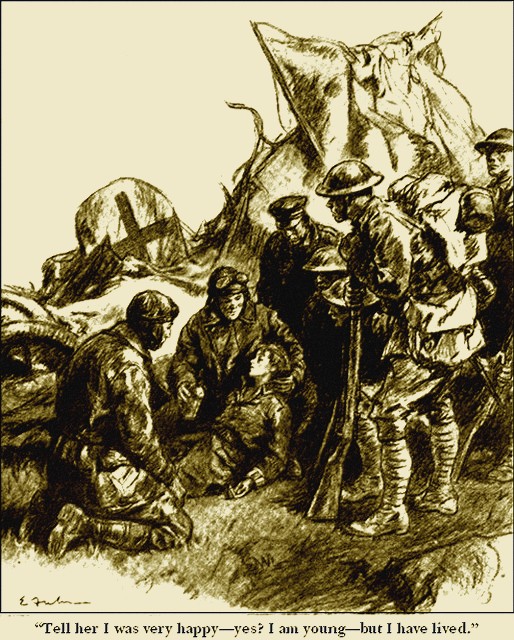

Something cracked from Tam’s left hand, a blazing ball of fire leapt toward the machine, filling the hangar with a pungent and disagreeable odor. The ball struck one of the wings, which burst into a blaze.

“Thairmite,” said Tam, “don’t try to put it oot.”

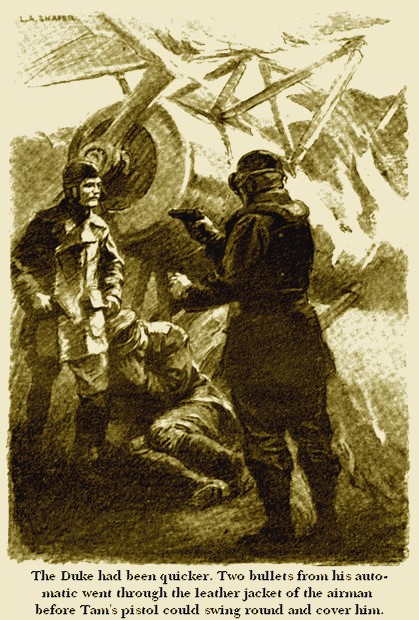

Von Grosser, paralyzed by the apparition, suddenly came to life. His hand dropped to the holster at his belt, but before he could draw his weapon Tam shot him down. The Duke had been quicker. Two bullets from his automatic went through the leather jacket of the airman before Tam’s pistol could swing round and cover him.

The machine was now blazing furiously. The room was an inferno. Tam beckoned first the Duke and then the mechanic toward the little door and he himself dragged the wounded man to the safety of the little passage.

Tam led the way up the steep incline to the open air. Suddenly he turned, and with a lightning blow felled the mechanic. Then he gripped the Duke by the arm and started at a jog-trot across the aerodrome.

Dense volumes of smoke were pouring through the interstices. The alarm had already been given and the shouts of command came to them through the darkness.

“Where are you going?” said the Duke suddenly and stopped dead.

“A’m going back to ma wee bed,” said Tam, “and ye’re comin’ wi’ me.”

“Then you’ll take me dead,” said the Duke in German and leaped at his captor.

An arm like a bar of steel flung him backward.

“By God, you shall suffer for this!” said the breathless young man.

“Oh, aye,” said Tam, “d’ ye no’ ken me?”

“I don’t want to ken you, damn you,” stormed the Duke in English.

By this time they had passed through the fence wires which Tam had cut. The Scotsman was making his way with confident step toward the plain where his machine awaited him.

“A’m Tam,” he said complacently; “d’ye na’ ken Tam? A’m Tam, the Scoot. Noo, Duke, over yon’ there’s a bonnie machine wi’ a nice comfortable seat for an obsairver. Will ye be my obsairver back to the British fines?”

The Duke thought a moment. “Under the circumstances, I think I will,” he said.

HALF-WAY back, and what time all the telegraph wires leading into Germany were in a condition bordering on hysteria, and while search-lights swept the skies and Archie barrages worked double time, Tam leaned over and tapped the silent figure in the observer’s seat upon the shoulder.

The Duke adjusted the speaking-tube and listened.

“Hand over yeer seegairs,” said Tam, remembering at this, the eleventh hour, that something was due to him.

THE entry of the United States into the European war may be likened to the entry of a large and enthusiastic boys’ school into a strange bathing-pond. There was a great leap, a monstrous splash, much laughter, many whoops of joy, a few yells of consternation and a considerable amount of spluttering. The experienced swimmers who were already in and were not finding the water any too fine, had been through exactly the same process before they learned the art of natation, and neither criticized nor sneered nor grew greatly hilarious, realizing that in time the hubbub would die down and there would be some desperately good swimming going on and that some of them would have to battle hard to keep abreast of the new material.

They were not all amateurs, these new arrivals. There were some who could do fine breast strokes and wonderful overhand movements and there were others who floated quite nicely. These were the “old contemptibles” of the American Army, those wise and wicked men who had sneaked away to Europe disguised as Frenchmen, Canadians, Englishmen—any old thing that gave them the right to enter the war zone.

Among the voertrekkers in the field of honor was a very considerable body of American gentlemen who were formed into a flying squadron attached to the French army and did truly wonderful work, being by nature adventurers. They earned world fame and deservedly so, for they did famous deeds which were chronicled in American newspapers and so fired the imagination of youthful America that when the big splash occurred, a large number of the swimmers made their way in the direction of those instructors in that peculiar form of warfare which is waged between the clouds and the stars.

A volume of recruits flowed into the American aerodromes to learn their business, but there was nevertheless a steady trickle of youthful talent toward France. Americans who were wintering in Egypt, Americans who were observing Paris or amusing themselves in London, very naturally directed their steps toward the American headquarters in France. They thought, and there was reason for it, that they were losing time by going to America and taking unjustifiable risks from submarines. Moreover, they were most anxious to finish the war before the other America came in, and so they filled the anterooms of the American military attachés in various cities of the world and armed with imposing passports and divers documents, they made their way to a town, which we will call Bonville, where there had been established in the twinkling of an eye the nucleus of an American Air Service.

The older men taught them the game—the stunts they found out for themselves. They did things which no reasonable and well-conducted airman should do, but everybody seemed to agree that under the circumstances those extraordinary departures from convention were wholly justified.

Tam of the Scouts was sent on a swift single-seater to make certain observations of the country which extends from the back of the British line to the sea. He was discovering landmarks whereby hostile airmen could find their way to a certain naval port. Wherever these landmarks were too conspicuous they would be camouflaged; even the course of a river, which helped a bombing squadron at night, might so be changed in appearance that it would not serve for guidance.

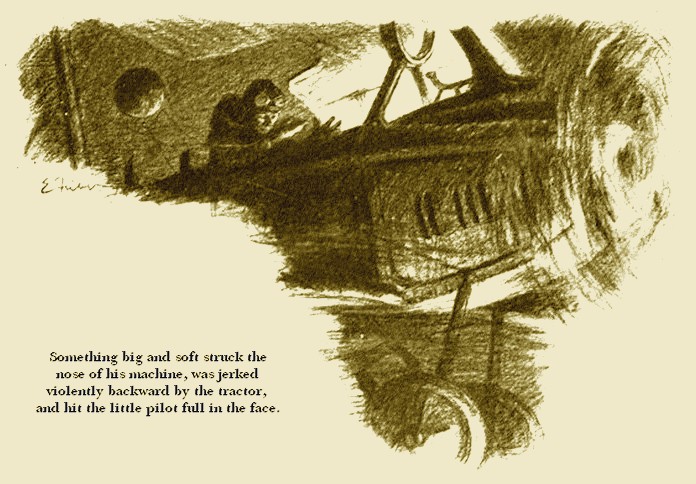

He reached the sea, circled over the port and headed back for his aerodrome. He was ten minutes’ distance from the town, that is to say, some fifteen miles, when he was attacked in the air by a large formation which when he approached it had been orderly and regular in its appearance, but which broke and broke unpleasantly when he came within rifle-shot. Two of the machines took no part in the attack. Their pilots were firing strangely colored lights with every evidence of agitation, but the remainder came upon him like a swarm of hornets and Tam was compelled to nose-dive into the middle of them, letting off his Lewis gun and very narrowly escaping a collision with a large and old-fashioned biplane which seemed to suffer from some chronic aeronautic affliction which caused it to loop the loop involuntarily.

Tam planed down to within a thousand feet of the earth, fluttered and ruffled. It was not his business to fight people and certainly not his business to take on fifteen hostile airplanes single-handed, and as he had the foot of his enemies, he had no difficulty in shaking off all except one pursuer, who chased him back to the aerodrome and when he landed, plumped down within a dozen yards.

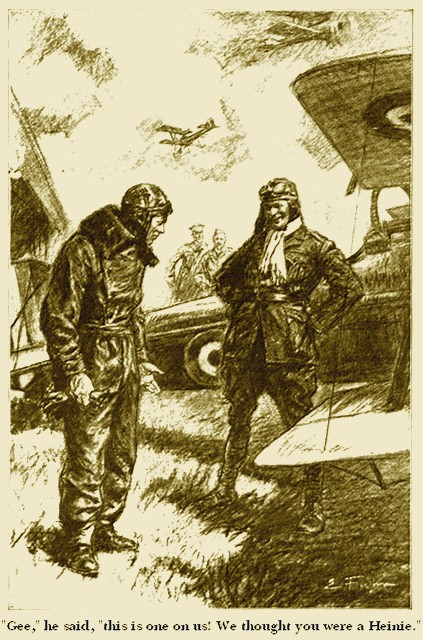

Tam walked across to the pilot as he was hastily unbuckling the straps about his middle and addressed him sadly: “Sirr,” he said, “can ye no’ tell a Hun when ye see him?”

The flushed young man who had jumped from the chaser shrieked with laughter.

“Gee,” he said, “this is one on us! We thought you were a Heinie.”

IT transpired that Tam had butted into the kindergarten, the boldest kindergarten that had ever learned the C-A-T, cat, of aviation.

Later came Captain Bredwell of the United States Army, a teacher of the new idea and a veteran of war. He was very apologetic.

“Training a set o’ pups is child’s play compared with teaching these kids not to hit anything they see running loose. I tried to call ’em to heel and just as well might Noah have whistled for the dove after he had got well on his way to Ararat. I am very sorry.”

“Not at all,” said Blackie. “Tam enjoyed it; didn’t you, Tam?”

“Weel,” said Tam, “A’m no’ so sure. A’ll be coming over your way to morrow, sir,” he said to the American officer. “What time do ye take your young gentlemen up?”

“From eleven till one, if the weather’s good,” said the other.

Tam nodded.

“A’ll be coming about two,” he said, “and ye’ll recognize me by the fact that A’m wearin’ a red rose in ma buttonhole and carrying the Scotsman in ma right hand.”

“The kindergarten is pretty difficult to handle,” confessed Captain Bredwell over the luncheon-table; “you see, we haven’t had time to ground them in the fear of God and military history. They are young, they are keen, they are full of spunk but they haven’t got the hang of this military business.”

He shook his head reprovingly at the boy who had chased Tam back to the aerodrome, but the youth was at that moment in a heated discussion with Lieutenant Curten on the relative merits of British and American motor-cars, both, strangely enough, being the sons of men who had grown rich in exploiting the public passion for speed.

“’Tis no’ discipline that young Rain-in-the-Neck wants,” said Tam—he had a trick of applying the nomenclature to be found in the works of his favorite authors to those who pleased him. “’Tis a little machine-gun practise. He was on ma trail a’ the time and didna get me—Mon, that’s inexcusable.”

“What really happened, Tam?” asked Baxter, and the babble of noise which accompanied every meal in the Umpty-fourth hushed to silence.

Tam looked over his audience as an experienced lecturer might.

“’Twas a fearfu’ experience,” he said. “Wingin’ ma way homeward wi’ no thocht o’ danger, wi’ a blaw sky o’erhead an’ the gay green airth beneath, A was thinkin’ o’ you young gentlemen an’ the veecious practise ye’ve got into of smokin’ cigarettes that produce anemia, palpitation, hairt disease an’ cold feet, when ma attention was attracted by the appearance on ma starboard bow of a graund aggregation of talent that would have made Buff’lo Bill tairn in his grave.

“At the moment A did not realize ’twas the United States Airmv practisin’ for bluidy war. Ma first thocht was that ’twas a party of French bairdmen that had been celebratin’ the feast of the Moulin Rouge.”

“Say!” chuckled Captain Bredwell loyally, “that’s rather tall—I guess the formation wasn’t perfect, but—”

Some one whispered to him and he sat back with a grin.

“Whilst ma mind was occupied wi’ givin’ the merry pairty a wide miss,” continued Tam, “the—what you might tairm for want of a better word—formation broke up an’ the ghastly truth dawned on me.”

He paused.

“’Twas a Wild West show,” he said solemnly, “yes sirrs! There was buckin’ broncos, an’ shairpshooters, an’ lasooers, an’ wild Injans an’ the pairformance started promptly—there was no waitin’. Whilst I was attacked on the right by Sittin’ Bull an’ on the left by Denver Dan, Mexican Joe dived from above, utterin’ the war-cry or totem or what-not of his fierce clan. Alkali Ike tried to ram me—or tried not to ram me, A don’t know which, but the result was nearly the same. The Colorado Kid caught ma controls a swat wi’ his sixty-six shooter—an’ A was chased to ma old log cabin by Rain-in-the-Neck howlin’ for the blood of the paleface.”

Tam’s acquaintance with the technique of the classics was an extensive one. He went on in his singsong tone.

“Of the rest of the story there is na much to be told.” he said. “Tam, the indomitable scoot, is noo an auld man wi’ gray hair, an’ may be seen, leadin’ his grandson to the scene of his great ficht, pointin’ oot the place in the sky where he was nearly straffit. Denver Dan ended his evil life in a low drinkin’ shanty, Rain-in-the-Neck is a Bug Hoose, whilst the Colorado Kid got releegion an’ made money.”

There was terrific applause when Tam finished—loudest of all from that same Rain-in-the-Neck (in private life Cadet Cyril Yanderberg).

THE story of Tam’s encounter with the kindergarten became public property. From Dunkirk down to Belfort hundreds of messes recounted the story with such embellishments as fancy dictated and in a remarkably short space of time it came to the ears of Captain Fritz von Stoffel, and naturally von Stoffel was greatly interested, for he was chief of the Baby-killers’ Circus.

It must be said that the babies he killed were mostly Germans. He was a disciplinarian of the fierce and fiery type. He never spoke, he barked. His lightest whisper was something between a rifle-shot and the explosion of a pop-gun. He had never raided London nor had he raided any of the villages that lie between the Kentish coast and the metropolis. Indeed he had never crossed blue water. He earned his title of Baby-killer because his specialty lay in the strafing of rest-camps, hospitals, unprotected artillery bases and observation balloons. He took few risks and in consequence endured very few casualties in air fighting; indeed, the heaviest death-roll resulted from his practise of sending nervous young pilots aloft in a high wind.

Now, most circuses are sporting. They are out looking for trouble and when they find it they get as close as they can and stay as long as it is safe, but everybody knows that von Stoffel’s circus never did anything which could be exaggerated into recklessness. It so happened when the news of Tam’s adventure came to the gallant captain that he had received a hint from the head-quarters of the corps to which he was attached—one of those broad Prussian hints that left a scar—that his cautiousness was developing into a vice, and it was suggested that it might be necessary to ask him to take a long leave for the benefit of his health and hand his command over to his junior.

Von Stoffel spent an evening in his stuffy and airless dugout grappling with “A Plan.” That plan, set forth with much detail, was delivered into the hands of the corps commander and by him transmitted to Highest Authority, retransmitted to the corps commander with certain hieroglyphics of approval scrawled upon its margin and by him forwarded to von Stoffel, who did everything but kiss the aforesaid hieroglyphics in his ecstatic happiness.

TAM of the Scouts was ordered one fine day to take a flight into Darkest France, and pursue investigations concerning the transportation of German troops westward. Two of his machines developed engine trouble and returned and Tam went on with the two that remained and had a most exciting morning. For though his machine was a scout and not of the bombing type, he carried four bombs for exactly the same reason that the average Western citizen carries a gun in his hip pocket, and passing over a seemingly deserted aerodrome he dropped a couple to discover whether anybody was at home.

He had hardly observed the bursts before his machine was ringed with well-aimed shrapnel. Whereupon his two companions, who were quite out of the danger zone, very naturally closed into it and one of these secured a direct hit upon a building which Tam surmised must have been the private brewery of that aerodrome, for he and his companions were immediately attacked with unparalleled ferocity by the owners of the aerodrome, who had been out hunting and approached their home behind the cover which a stratum of cloud afforded.

Whereupon the three British airmen decided that it was getting very late and streaked westward, all out, losing a little height to increase the margin which lay between them and their pursuers. They passed over the line, disgracefully deserted at this particular moment by fighting craft, with six machines still in pursuit.

Now, no airman, in whatever distress of mind he may be, will fly from an enemy over his own territory, even should the enemy be overwhelmingly stronger, and in conformity with the unwritten law of air fighting, no sooner had the zigzag of trenches been left in his rear than Tam signalled “Engage” and swung round to meet his enemies.

Two modern air-planes separated at a distance of four-hundred and fifty yards approach each other at such a speed that they pass in the time that you can count six. In three of these seconds the decisive battle is fought. Either you “get” your enemy, your enemy “gets” you, or you “get” one another.

In a flash as they passed Tam saw the enemy pilot drop, and as he himself had no inclination to drop, he knew he had won, unless the enemy observer had escaped and was using the dual controls.

Imagine these two machines passing each other on a parallel course and a second later a third machine dropping from the blue and missing the tail of the attacker by inches. Picture a second British machine falling after this bolt, his gun shooting vertically earthward, along the nacelle of the diving German; imagine two other enemy machines banking over and shooting sideways and indiscriminately at Tam and his assistant—a roaring, whirling mix-up of air-planes bucking and jumping, slipping, climbing and diving, and suppose that all this happens in the space of some twenty seconds, and you visualize an air battle at its most intense period.

Tam looked down as the second machine fell in flames and began his glide to earth, for he did not need to see the remainder of the enemy flight wheel eastward to know that the battle was over. One of his own machines was going down in circles. Tam saw this and wrinkled his nose—that was the only sign of sorrow he ever showed—and there was reason enough, for that easy spiral which was bringing a dead pilot and a dead observer to earth would end in a crash.

Tam’s report was almost uninteresting by the side of another report which was being flashed along the wire to Headquarters Intelligence. It was the report of a young and keen intelligence officer who had sat by the bedside of a dying German air-man, one of those whom Tam had grounded, and had listened to the unconscious man as he talked of his home in Darmstadt and his mother and the fishing on the Moselle, and how splendid it would be to go to Marienbad this summer and other things which had made the intelligence officer lean over the bed, listening intently and scribbling notes in the little book he whipped from his tunic pocket.

THE air-man died before he said very much. If he had died sooner he would have saved the German army quite a number of casualties.

Tam was roused from his bed at midnight by the entrance of his superior.

“Sorry to wake you from your beauty sleep.” said Blackie, putting no hint of sorrow in his voice, “but there’s the greatest stunt on.”

Tam sat up in bed blinking at the electric light.

“Take an interest, you sleepy devil,” said Blackie.

“Oh, aye,” said Tam. “A’m awfu’ interested. A’m speechless wi’ it.”

Blackie sat himself on the bed. “The Hun is going to strafe the kindergarten to-morrow,” he said; “you butted into the Baby- killers.”

“You don’t mean it.” said Tam, wide awake. “It was no’ von Stoffel?”

“It was von Stoffel,” nodded Blackie, “and you interrupted a practise attack. I have always said the kindergarten flies too near the line for safety. I don’t think they will after this. It is a pretty low-down thing to do, but I suppose it’s fair. Von Stoffel is taking big flights to-morrow and intends swooping down on the kindergarten and there shall be a great slaughtering of innocents, according to the plan. Intelligence found it out and you are for the stunt,” he shook his head mournfully. “You are a lucky beggar,” he said; “I don’t mind admitting that I asked to go in your place, but my life is much too valuable.”

“What is the stunt?” asked Tam.

Blackie chuckled. “The kindergarten will remain in school to- morrow,” he said, “their places in the air will be taken by the aces. All the squadrons in this part of the world are to send one. You are the representative of the Umpty-fourth.”

Tam swung his legs out of bed.

“There’s no need to get up,” said Blackie, “the stunt isn’t on for another nine hours.”

“Mon,” said Tam. unbuttoning his pajama jacket, “’twill take me that time to learn the American language.”

AT five o’clock in the morning two specially chosen patrols flew to the region of the kindergarten’s aerodrome and began sweeping the skies eastward, forming a barrage through which no inquisitive Hun might pass. They were not protecting the kindergarten, far from it. They had a certain duty to perform and when that was performed, as it was by eight o’clock, the patrols signalled one another good-by and departed for their homes, leaving the way clear for von Stoffel, who was due at eleven, that being the hour when the kindergarten took the air.

But between five and eight the aces began to arrive, sweeping down from great heights and ranging themselves in nice orderly lines on the broad expanse of the aerodrome. Tam was the first to arrive. De Rochleaux, with twenty-nine crashed to his credit, was the second. Mildred of the Hundred and Umpty-first Squadron, who had on one memorable occasion taken on a circus single-handed and had brought down six machines, was the third, and after his arrival the aces fell thick and fast.

Le Fevre, Runnymede, Lord Arthur Saxman, Townly, the American instructor with eighteen skull-and-cross-bones painted on the nose of his machine to represent the eighteen sad occurrences to the German Army, Minter “the guardian of Ypres”—they all met for breakfast, full of joy at the forthcoming meeting. They took the air at 10:15, flying raggedly, the most beautiful piece of camouflage that was ever seen in the air.

At exactly the same hour von Stoffel snapped the case of his great gold watch and remarked to his obsequious adjutant: “Before we come back the American correspondents will have something to write home about.”

He glanced down at the long line of airplanes, pilots in their places, mechanics standing by the propellers, and raised his hand in a signal. Instantly there was a roaring and snorting, thudding and thundering din of engines. His hand dropped and his graceful Fokker leaped forward and zoomed up at an acute angle. One after the other the squadron followed and ten minutes later the formation was in being.

Von Stoffel, sitting in the cock-pit before the pilot, fired his signal pistol and the big circus moved westward. The German commander adjusted his ear-piece and speaking-tube, fired off a few rounds from his gun to test it and then gave himself up to the enjoyable prospect before him.

The circus crossed the British lines and were greeted by Archie in the usual manner. Von Stoffel, his powerful field-glasses to his eyes, searched the distant heavens.

“Ah! There they are,” he said triumphantly, and signaled “Enemy in Sight.”

“We shall have to climb,” said a voice in his ears, the voice of his squadron’s crack pilot, “they are much higher than we.”

“What are we flying at?”

“Ten thousand feet, Herr Captain; they are at twelve thousand.”

This was hitch number one. The reconnaissance patrols which von Stoffel had sent out had reported that the kindergarten never flew higher than eight thousand feet. The baby-killer signaled a change of direction and asked for altitude and the big formation began climbing. Again the direction was changed.

“They are climbing too,” said the voice of his pilot. “I think they are going up to fifteen thousand.”

Von Stoffel swore and again his squadron climbed.

The spurious kindergarten watched these maneuvers with the greatest hilarity. Lord Arthur Saxman, by reason of his seniority, commanded the right wing.

“Bags I the great white chief,” he said joyously and went down in an alarming nose-dive, working both his guns—for he was a two-gun man and ambidextrous.

“That big bomb for mine!” said Captain Bredwell and dropped simultaneously.

“Big fellow, I want ye,” and Tam dropped, his gun rapping furiously.

This was all very hard luck on von Stoffel, because either of these aces could have settled him.

Of the twenty-two strafers that set forth to beat up the kindergarten, four came back, two limping, if a knocking engine be the equivalent to a limp, and a German communiqué of that night read:

“WE CONDUCTED A SUCCESSFUL RAID UPON AN AMERICAN AVIATION CENTER. SEVERAL MACHINES WERE SEEN TO FALL IN FLAMES. ALL OUR MACHINES RETURNED SAFELY.”

This telegram, thoughtfully transmitted from headquarters to the kindergarten mess, where they were entertaining the noisiest bunch of guests that had ever assembled, embellished the end of a perfect day.

TAM of the Scouts sat enthroned on the edge of the billiard table—which, appropriately enough, since he formed the topic of conversation, was a luxury donated by the Splendiferous Lieutenant Walker-Mannsell whose paternal relative was reputed to have so much money that he had refused war contracts. This Splendiferous One, still spoken of by the squadron with affection and amusement, lay in a little grave to the west of Mossy Face Wood, and that the squadron joked about him is accounted for by the fact that the men of the R.F.C. never die, and, accordingly, are never invested with solemn post-mortem virtues designed to prove that they were really too good to live.

Therefore he was “The Splendiferous One” and “S.W.M.” and men roared over the jokes told against him—and if they always ended the story with “good old Splendif, he was a lad of the village”—why, they would have done the same if he had been just outside the mess-room.

“A call to mind an argument wi’ Mr. Walker-Mannseel,” said Tam. (Observe that Tam was a sergeant when the boy was living and Tam regarded it as extremely disrespectful to quote the nickname he would never have employed to one who was his superior.) “’Twas hoo much an ordinary spendthreeft could spend in a day if he’d gie his mind to it—A said five dollars, but the wee lad rather thocht that if a body corn-centrated he micht spend seex.”

“Good old Splendiferous,” said Blackie, laughing with the rest; “but you haven’t told us what happened to Goldheimer.”

Tam had begun the story of the magnificent Goldheimer and had drifted through a dissertation on plutocracy in the field, to one of the best loved of his officers.

“Goldheimer” had been born Thysen-Hyndorpf. He had been born with a steel ingot in his mouth, for his parent had been the veritable Theodore Thysen, the Westphalian steel baron. His brother officers had named him Goldheimer and even worse, and in due course the fame of him came to the right side of the line, and his photograph, cut from a Berlin society journal, adorned the green notice-board of the mess of the Umpty-fourth.

There he smirked, with his stout, vacant face, his stiff little mustache, his tiny monocle, his imposing Pickelhaube, and men of the patrol on their way to the sheds would stop and examine the features thoughtfully and wonder if it was their luck to get him that day.

Goldheimer was rich—rich beyond the dreams of actresses. He was so rich that if he had written down his fortune in marks he would have had writer’s cramp before he reached the last cipher.

He was so offensively rich that every hard-up subaltern of the R.F.C. pined for his destruction.

“ ’Twas no’ like the lad to be oot before the air was war-m,” said Tam, resuming his narrative at the point where it had been diverted, “an’ ye may imagine ma surprise, when passin’ to the sooth o’ Cambrai—at the place where the Hoon has five or six bridges across the canal—to obsairve the expensive ootfit of Mc Goldheimer riskin’ the mornin’ air. There was no mistakin’ him. His seelver-mounted wings, the graund gold monogram on his silken wings, the filigree fusilage by Mr. Benny Vinturo, the heavy di’mond buckles to his stays, the jeweled engine an’ the gun-metal gunwork of his gun. ‘Tam,’ says A to mesel’, ‘are ye no’ ashamed to be seen oot in the same sky as yon? Awa’ wi’ ye!’ A says, ‘be off an’ brush yeer pants an’ change yeer cravat—look at Mc Goldheimer,’ A says, ‘take a lesson from him—follow him,’ A says—so A followed.

“He sat in his seat a fine figure of a man. His surtout or haubeck was of some clingin’ material that clung. Aboot his shapely heid was a broad band of dull gold richly encrusted wi’ uncut rubies; a simple collar of celluloid an’ mother-of-pairl or father-of-concrete completed the picture.

“A dived for to make his acquaintance. But he was prood. The haughty intolerance which comes from generations spent in the board-room cuttin’ down expenses would not allow him to unbend. He side-flopped wi’ dignity, but A was no’ to be shaken off.

“‘Ma mannie,’ says’ A, ‘do ye no’ ken that Tam o’ the Scoots is on yeer trail? Have ye no creepin’ sensation up an’ down yeer spine to tell ye that the terror of the cloods is stayin’ wi’ ye?’ Apparently not. Wi’ the courage of despair the reckless millionaireman tairned on his remorseless pursuer, his coorse face inflamed wi’ drink, high livin’ an’ annoyance. He glared at his persecutor, the gold fillin’s of his teeth quiverin’ with passion.

“Glancin’ scornfully at his puny opponent he banked o’er and got the sun* of his absent-minded but resourceful foe. ’Twas a contest that Homer or Rudyard Kiplin’ would have taken the elevator to see. Capital an’ labor battled in the cloods. The hated money classes an’ the sweatin’ proletariat joined issues. The idle rich—an’ no’ so idle wasn’t that lad as ye’ll notice, if ye take a squint at the wings of ma wee Kitten—the idle rich an’ the haggard toiler, alone, or nearly alone, under the watchin’ stars, focht that the wairld should be made safe for democracy.

[* “Getting the sun” is to get between the sun and your enemy.]

“It ended a’ too soon,” said Tam sadly. “A came down in a fine dive an’ loosed ma last drum at the diamond sun-burst he wore on the back of his neck an’ he responded. Instantly gold bullets was hailin’ aboot my ears. If A’d stayed long enough A’d have died a millionaire. Dazzled an’ blinded A broke off the unequal contest an’ dropped slowly to airth.”

“Which means that Goldheimer’s patrol got on your tail and strafed you?” suggested Baxter.

“Aye—something like that,” admitted Tam; “there were ten o’ the lads—Tam could have tackled nine—but the fearless boy fra’ Glasgow was outnumbered.”

“Goldheimer putting on frills?” somebody asked and Tam smiled.

“A’d be sorry to lose the wee feller—he’s a graund practise for the young an’ inexperienced aviator.”

In real life, whatever may be the case in fiction, the multi-millionaire, even though he may have inherited his fortune, is very infrequently a fool. He may generally be distinguished by his uneasiness, his suspicion and that shrewd business ability which we associate with confidence men. Nor are stout young men who affect monocles and wear ridiculous mustaches necessarily brainless, lethargic and addicted to the four a.m. habit.

Goldheimer was a notable illustration of the fact that great possessions sometimes go hand in hand with great mental capacities.

Many crack pilots, French and British, had gone out to say how d’ye do to the Goldheimer patrol and had come back more cracked than ever. He was fat but nippy. His eye was glassy, but behind the sights of a machine-gun it had all the robust qualities of the big game hunter. He was ridiculous but his airmanship was sublime. The scalps of seventeen British machines hung to his bomb-proof wigwam and he was always out to add to his collection.

“As like as not the puir lad’ll be shot down by an Archie that’s aimin’ at somethin’ else,” said Tam, “or he’ll fall to the kindergarten—”

“Which reminds me,” said Blackie, looking up from his cards, “I am going to plant a Hun** on you.”

[ *“Hun” is a term applied to all aviation recruits.]

“A Hun!” said Tam is consternation.

Blackie’s eyes twinkled as he nodded.

“Cadet William Best of the United States Army,” he said. “They are breaking up the kindergarten and attaching one youngster to each of the French and British squadrons. As a matter of fact,” he went on, “you will find William quite a pleasant young man, he has already had some air-fighting experience. He attached himself to the Camelot Squadron about six months ago and though he has not undergone his full technical course, he is a pretty wise bird.”

Tam had got down from the billiard table and was looking dolefully at his superior.

“Am A to understand, Major Blackie, sir, that A must teach this young gentleman controls?”

“No, no, Tam,” laughed Blackie, “not so bad as that. You will just give him tips on air fighting. From what I have heard of him he does not require much tuition. Be at the office to-morrow morning at ten o’clock and I will introduce you.”

At that hour Tam met his pupil. He was young, very young. His face was fresh and pink like a girl’s, his gray eyes, full of laughter, were lit with those eager fires which God kindles in children to warm the ashes of their parents’ hearts.

“This is Cadet Best,” introduced Blackie; “this is Second Lieutenant McTavish who will take you under his wing.”

“Glad to meet you,” said Cadet William Best joyously and extended a large, firm hand.

Tam and his charge surveyed one another in an amused silence.

“That is all,” said Blackie after an embarrassing pause.

Tam jerked his head to his companion and they passed out of the office.

“Have ye a bed, sir?” asked Tam.

“Sure—I carry one around in my grip,” said the cheerful youth.

“What A mean,” said Tam, “have ye a place to lay yeer weary heid if ye survive the dangers an’ perils o’ the elements?”

Cadet William Best grinned and shook a head which in its bright-eyed alertness showed no signs of weariness.

“Weel,” said Tam, “ye’ll bunk wi’ me. If ye leave the door open an’ sleep wi’ yeer feet oot o’ the window there’ll be room for ye.”

No other word was spoken. Tam led the way with dignity, opened the door of his quarters and ushered his friend into the little room.

“Do ye smoke?”

“Sure.”

“Would ye like a seegair?”

“Try me.”

Tam thought a while. “Yeer too young for seegairs,” he said; “they try the nairves an’ weaken the nairvous system—A’ll give ye a stick o’ candy.”

He groped under his bed and produced a large box of familiar tint and embellishment. This he opened, disclosing a platoon of large cigars lying stiffly at “attention” wearing the gold and scarlet waist-belts of their caste.

“Perhaps ye’d better smoke,” said Tam gloomily; “they cost one franc twenty-five per, an’ A doot if they’re paid for.”

“Fine,” said Mr. Best enthusiastically; “these look good to me—where do you buy ’em?”

“A dinna buy seegairs,” said Tam. “They’re donated by ma friends, admirers—an’ pupils.”

“I get you,” nodded the other, puffing luxuriously.

“A’m a prood an’ tetchy feller,” said Tam; “ye must no’ hairt ma feelin’s by handin’ ’em to me in a coorse an’ brutal manner. Ye must just leave ’em aroond careless an’ A’ll find ‘em—yeer name is William, A doot?”

“William,” agreed the pupil.

“A’ll be callin’ ye Billy,” said Tam; “’tis a nickname A’ve invented. Ye’ll be Billy Best—no, ye’ll be Boy Billy Best inside this room so that ye may retain a sense of ma superiority in age, morals an’ proved efficiency. Ye may call me Tam an’ ye may sleep on that bed when the sheets are changed.”

“Where will you sleep?” demanded Billy Best with a hint of truculence in his tone.

Tam rubbed his chin. “A’ll sleep on the floor—A prefair it. A’ve never slept in a bed in ma life. Gie me a heap o’ slag an’ a couple o’ bricks an’ A wouldna’ call the king ma uncle.”

Billy drew at his cigar deliberately.

“You may can all that sleeping-on-the-cold-ground stuff,” he said; “the floor for mine—I’m a hog-sleeper. Nothing short of a head-on collision wakes me and I prefer broken glass to Ostermoors.”*

[* An American matress brandname.]

“A could never sleep in a bed,” protested Tam; “’tis effiminate practise an’ weakens the army’s morale.”

The timely arrival of the quartermaster sergeant with a fatigue party and a second bed put an end to the discussion.

It was after this was installed and the heavy-footed mechanics had departed that Billy Best, acquainting himself with his new surroundings, discovered things behind a cretonne curtain—four rows of shelf tightly packed with literature; not the commonplace literature stiffly bound and consistently neglected which you would find in a library of the literary dilettante; not the musty tomes that decorate the study of the professor, but bright, vital, red-blooded stories between paper covers of lurid design.

Tam was writing at his table when he heard a gasp and looking up, went very red, for Billy Best, his eyes blazing with joy, was examining a twenty- four page monograph devoted to the life and death of Yellowstone Jim who was (as the explanatory subtitle revealed) The Lone Bandit of Crow’s Nest Canyon.

“Ye’ll no’ want to be readin’ that stuff,” said Tam uncomfortably—he was a little sensitive with strangers; “they belong to a young frind o’ mine.”

“Do you mean to say you haven’t read them?” asked the amazed youth. “See here—if you haven’t, make a start. This is the only stuff worth reading. You can have your Scotts and Dickenses and Thackerays—this is meat.”

“Weel,” said Tam, “A’ll no’ say A haven’t glanced through these degradin’ wairks of fiction.”

“Aw!” grunted the boy, “degrading nothing—this is life! Look at this one, ‘The Pawnee Cache or Black Dick’s Fight for Fortune’—one of the best yarns—”

“Mon, it’s easy to see ye’ve no’ read—here gie me the books—here it is. ‘Mollie the Moorman or The Thugs of Utah’—when ye’re talkin’ aboot stories will ye cast yeer eye o’er that yin!”

Tam was excited now—Billy Best’s voice was raised to a key of dispute.

“You’re nutty, Tam! This Pawnee Cache yarn—”

We may leave them to their disputation. Wiser men, men grown gray in the service of Arts and Letters, have argued as fiercely and with less kindliness over matters in no sense more important.

At ten o’clock the next morning Tam and his new assistant took the air—Tam at the controls, Billy in the cockpit for’ard.