RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900)

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

Based on a painting by Ivan Aivazovsky (1817-1900)

"Marooned on Australia

Blackie and Sons, London, 1895

"Marooned on Australia

Blackie and Sons, London, 1896

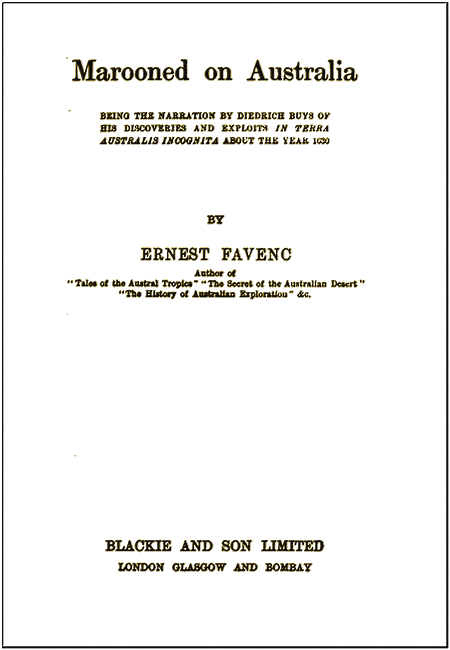

IN the following romance I have endeavoured to associate the tradition of De Gonneville's visit to Australia with the historical fact of the wreck of the Batavia, and the marooning of two of the mutineers. The wreck of the Batavia is perhaps one of the most murderous tragedies that ever happened in any part of the world. One of the ruffians confessed, before being hanged, to having killed and assisted to kill, twenty-five defenceless people. A full account of the wreck and the massacre will be found in Pinkerton's Early Voyages.

I have taken a liberty with history in introducing Captain Sharpe, the buccaneer, as in reality he never visited the Australian coast, although some of his crew did. I must also confess to having taken some freedom with chronology as, under the name of Hoogstraaten, I have introduced Abel Janz Tasman many years before his actual advent on the western coast of Australia; and De Witt's voyage of discovery really took place before the wreck of the Batavia. I trust, however, that in a romance these inaccuracies will be pardoned.

In the appendix the reader will find an account of the setting up of the great Cross by De Gonneville, and the record of Sir George Grey regarding the head carved on the Rock.

Ernest Favenc.

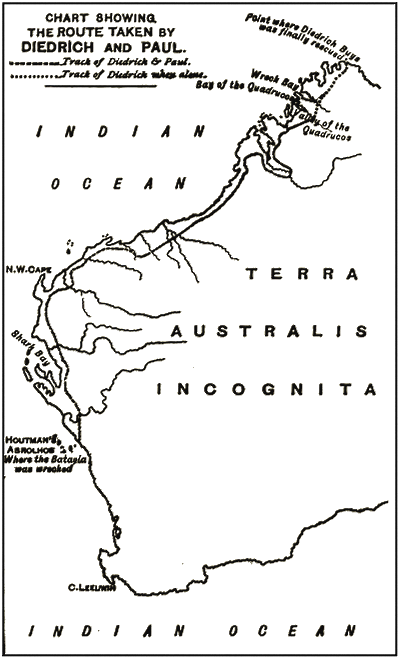

Chart showing the route taken by Diedrich and Paul.

Paul and Diedrich are marooned in a great unknown land.

JEROM CORNELIS! Even now after all the suffering and danger I have gone through, that man's face, the face of the tempter, comes back to me as vividly as ever.

My father was a substantial merchant of Harlem, and in that town I was born, being the second son. That was the age of discovery, and the thirst for it was inherent in nearly every youth. The wonderful success of the Dutch East India Company had fired all men with enthusiasm, and as I grew towards manhood, I longed to make one of the many bands of adventurers who often left for the East. So persistent did I become that my father at last consented to my going, thinking that a voyage would probably cure me. Having some influence with several of the directors of the great company, he obtained for me a subordinate position as clerk to the supercargo on board of the Batavia, one of a fleet of eleven ships about to sail from the Texel to Java.

Jerom Cornelis was the supercargo. He had been an apothecary in Harlem, and as such I had known him for some time. He was a man of ability and education, and I had a boyish admiration for him. Now I know him to have been a man whose talents were marred by an intense, almost childish vanity, and a disposition, cruel and relentless as the tiger's. As a lad of eighteen, I saw nothing but the wonderful fascination he exercised, and listened entranced when he dazzled my imagination with pictures of future greatness in the rich islands of the eastern seas.

Our voyage was a stormy one, and as the Batavia had over two hundred souls on board, the discomfort was great. I shared a cabin with Cornelis, and in every way that singular man strove to win my affection. Why he did so I cannot say even to this day.

We had been nearly two months at sea, when Cornelis confided to me a plan he had formed, in conjunction with the pilot and some other mutinous spirits, to seize the ship and turn pirate. I endeavoured to dissuade him, but without avail; he bound me over to secrecy and assured me that my life was safe whatever happened, as he would not allow me to take an active part in it, which I certainly had no intention of doing. The plot, however, was frustrated by the weather and other causes, and although I am certain it came to the ears of our commander, Captain Pelsart, he did not, unfortunately, hang the mutineers out of hand as one would have expected from a man of his determination.

Now one would have thought that this would have revealed to me the true character of Cornelis, but such an infatuated fool was I, and so beguiled by his specious tongue, that I still remained his friend and admirer.

We had now doubled the great southern cape, and storm after storm burst upon us with relentless fury. One by one we lost sight of our consorts and at last found ourselves alone; driven out of our course into an unknown sea.

To add to our distress, Captain Pelsart was confined to his berth with sickness and the vessel was in charge of the pilot, who apparently lost all reckoning. It was on the morning of the 4th June, 1629, for the date is indelibly engraven on my memory, that our voyage was brought to a fatal termination by the vessel striking on a reef of rocks. When I got on deck there was nothing visible but white surf and foam everywhere, and we had to wait until daylight, the ship bumping heavily meanwhile.

Daybreak showed us to be in the neighbourhood of a group of rocky islands, one of which was close to us. Finding that the ship was irretrievably damaged Captain Pelsart proceeded to land the passengers and crew on the nearest island. Great confusion ensued and many of the sailors broached some casks of wine in the cargo and got drunk. Provisions were landed, but very little water, and as none could be found on the island, our captain, after two days, started with a boat's crew to the mainland, which we could see in the distance and which was supposed to be the mysterious continent known as Terra Australis.

I had been separated from Cornelis in the turmoil of the wreck, and indeed it was not until the Batavia was utterly broken up that he came ashore almost dead. He had been floating for two days on the topmast of the ship, carried backwards and forwards by the current, until at last he drifted near enough to gain the land.

On regaining strength he assumed command, in the absence of the captain, and in spite of all the bloody deeds of that guilty man I will say that he restored some sort of order amongst the demoralized crew and passengers. One of the petty officers named Weberhayes was despatched with some thirty men or more, including some French soldiers in the pay of the Company, to a large island visible to the eastward. If successful in finding water he was to light two fires. The water supply consisting only of rain in the holes in the rock, another smaller party were conveyed to a neighbouring islet.

All this was done in furtherance of a plan maturing in the mind of Cornelis. He retained about him all the ruffians on whom he could rely when the time came to act. This soon arrived. For Pelsart not returning Cornelis threw off the mask. He assembled all his followers at a meeting at which I was forced to attend, and here they all swore a solemn oath to stand by each other, and if Pelsart had gone on to Java and returned with a ship they would endeavour to capture it, if not they would build one out of the remains of the Batavia, and start north on a piratical cruise. But first, the mouths of those who could not be trusted had to be silenced for ever.

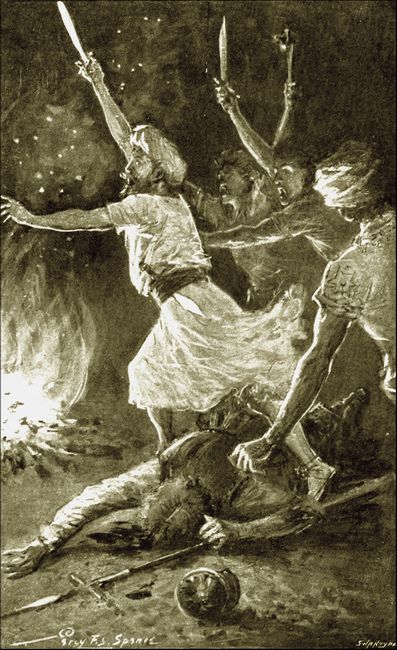

That night I was awakened by shrieks, groans, and cries for mercy. Cornelis and his myrmidons were butchering in cold blood the helpless people whom they had not admitted to the conspiracy.

I could do nothing during that night of horror, but try and close my ears to the piteous cries of the victims. Next morning, with their lust for murder still unsated, they went over to the small island and recommenced their fiendish work on the defenceless people. Unfortunately for Cornelis, however, some few escaped and during the night succeeded in making a raft and crossing to the large island, where Weberhayes and his party were. They informed him of the butchery that had taken place and put him on his guard.

The vanity of Cornelis now got the ascendency of him. He had himself proclaimed Governor-general of the barren, rocky islet we were on, which was christened "Batavia's Grave". He had the merchants' chests broken open, and from the stuffs contained therein uniforms were made for a chosen body-guard. This being done, it was determined to exterminate Weberhayes and his men.

Not knowing of the escape of some of the victims, they rowed up confidently, expecting to take the party by surprise, but were surprised themselves. Weberhayes and his followers, armed only with such rude weapons as clubs and stones, fell upon them suddenly, killed some, and forced the others to make a hasty retreat.

Incensed at this repulse, Cornelis led a fresh assault in person and I was ordered into the boat. I had no stomach for the fight, and did not feel particularly sorry when we got more soundly beaten than before.

Weberhayes' party now had arms, taken from the dead mutineers, and Cornelis resorted to treachery. He sent the chaplain, whose life had been spared, to negotiate; and meanwhile he tried to bribe the French soldiers with some of the treasure of the Batavia, but they were loyal and at once reported the matter to Weberhayes. A truce was then agreed on. Cornelis was to send over some provisions and receive water in return, of which there was a permanent supply on the island. Weberhayes, however, rightly mistrusted Cornelis and was on his guard; so when a sudden attack was made he was prepared, and not only beat them off with loss, but captured Cornelis.

This was the end of the rebel Governor General. I never saw Cornelis again until the rope was round his neck.

Now commenced on the island I was on, called "Batavia's Grave", a wild pandemonium. There were still some casks of wine left, and the ruffians drank and quarrelled, and fought with knives over useless pieces of silver. With the capture of Cornelis every semblance of a plan seemed to have vanished. Never shall I forget the horror of that time, although I have seen blood flow like water since. Five wretched women who had been spared from the massacre, two of them being the daughters of the chaplain, were stabbed to death by these devils, and how I escaped a knife through my heart I know not.

At last one morning a sail was in sight, and aided by a fair wind a large ship came swiftly on and soon dropped anchor halfway between the island of Weberhayes and "Batavia's Grave". Hastily arming themselves a large boat's crew from our island started to board the ship. Weberhayes was, however, before them. As Pelsart—for it was he with the Sardam frigate—left the ship, intending to land, he was intercepted by Weberhayes who told him the true state of the case. They returned on board and awaited the coming of the other boat. The mutineers, in their gaudy uniforms, were allowed to come well within range. They were then hailed and ordered to drop their weapons overboard and come on board; which they did, and were at once put in irons. Pelsart then landed, but the rest made no resistance and were secured, I being amongst them.

We were kept close prisoners on the island for many days whilst the sailors of the Sardam tried to recover the treasure lost in the Batavia. Then one day we were taken on board. Some of us were interrogated, some not. I had to confess that I had accompanied one of the armed boats which attacked Weberhayes. There was a short consultation in the cabin, then the deadly work of retribution commenced. One after another the murderers were run up to the yard-arm, and then their bodies were thrown into the sea. Cornelis was hung from a higher yard than the others, in acknowledgment of his leadership. They all died sullenly and defiantly.

As I expected a like death, and had now become used to scenes of bloodshed, I looked on in apathetic despair. At last when it seemed that my turn had come, for there was nobody but myself and a sailor named Paul left, the executions ended; for the ropes were unreeved from the blocks, the anchor raised, some sails set, and the ship stood in for the mainland. Not a word was said to either of us. Paul was an old sailor, and one who had kept his hands as free from bloodshed as possible. He looked inquiringly at me, but I could only do the same to him. Neither of us knew what this meant.

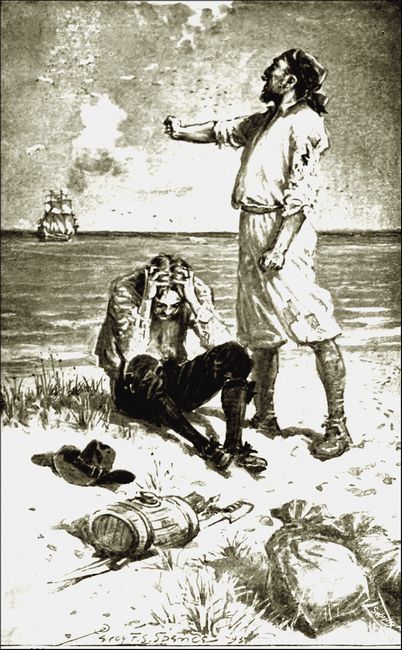

When within a short distance of the land the ship hove to, and a boat was lowered. Our irons were struck off, and we were ordered to get in. A short row took us to a spot where there was easy landing on a beach, sheltered by a rocky reef which broke the surf. When the boat grounded we were ordered out; a couple of bags of biscuit, a breaker of fresh water, a tomahawk, and a cutlass were passed on to the beach. As the sailor who placed these things down stooped near me he whispered something that gave me a clue to our fate. He was one of Pelsart's men and came from my native town of Harlem. The boat's crew shipped their oars and pulled rapidly back to the Sardam.

Paul muttered a terrible curse and looked at me. There was no longer any doubt. We were marooned on the coast of the great unknown South Land. To die at the hands of the giant savages said to inhabit it, or the more dreadful strange beasts. What the friendly sailor had whispered to me was, "Keep your heart up. Ships may be round here soon."*

[* On his second voyage of discovery Tasman was instructed to call at the Abrolhos, and endeavour to find the two men left by Pelsart; to learn from them all they had found out about the country, and if they desired it, to give them a passage to Java. The record of this second voyage of Tasman's has, however, been either lost or destroyed.]

So far as I know they never came; when the Sardam's masts sank beneath the horizon, both Paul and I had looked our last upon a European sail for many long years.

THE loneliness of the night that soon closed around us was such as I had never experienced before. Every strange sound or cry of a night-bird startled us from our uneasy sleep on the sand: both of us were heartily glad when daylight banished some of the unknown terrors that had haunted us through the hours of darkness.

After our meagre meal of biscuit and water, I proposed that we should make an excursion a short distance inland, and find out what sort of a place it was where we were abandoned. Paul agreed; and this I must confess here, that, although in after adventures we took opposite sides, and to avenge a great wrong I had to consent to his death, yet during the first years of our miserable exile Paul was the best companion a man could have had.

We hid our water and provisions in a secure place, as we only intended to make a short excursion; then we climbed the low rocks at the back of the beach and found ourselves on a sandy flat, covered with coarse wiry grass. Beyond was a thicket or close forest of low trees and towards this we made our way, Paul armed with the hatchet and I with the cutlass.

We found the thicket barren and grassless, and beyond again was an opening in which we saw, as we thought, a large village of white huts. We listened, but hearing no sound we advanced cautiously towards it. We soon found out our mistake. What we supposed were huts were big mounds of earth built up, as I now know, by a large light-coloured ant. Paul climbed up on the highest of one of these, which was nearly ten feet, and from the top called to me that he could see a low range of hills in the distance, then he came down hastily and whispered that he saw smoke rising a short distance away.

After talking the matter over we agreed that, as we were bound to come in contact with the inhabitants at some time or other, it would be just as well to have it over at once, so we advanced with outward boldness in the direction of the smoke. I confess that my heart sank at the thought of meeting these savage and formidable giants, who were reported to have killed and eaten many of the Company's sailors, but I kept a good face and we were soon close to the place. We came upon them unexpectedly, for they were squatting round two or three fires cooking shell-fish. They raised a great hubbub when they saw us, and most of them ran away, but some raised their lances in a threatening manner.

Both Paul and I gained courage when we saw these Indians, for they were not giants at all, being rather undersized, with thin legs and arms. They were black and quite naked. We shouted to them, and, having read of such things, I broke off a green bough and held it up. This appeared to please them for they lowered their lances, and after some delay allowed us to approach. One of them then gave a peculiar cry, and the rest of the tribe, including the women and children, approached timidly from their hiding-places.

Conversation was of course impossible, but we made them understand at last that we wanted to find out where they obtained their fresh water. They led us to a sandy patch of ground where there was an old tree with white bark. Here a hole had been dug and covered with boughs. On tasting the water it proved to have a somewhat sweet flavour but was quite fit to drink.

Thus relieved of one of our chief causes of anxiety, we determined to make friends with these wretched Indians and, if possible, live with them until another discovery-ship visited the coast; for I believed in the warning whisper of the sailor. I can never understand why my life was spared. Not on account of my youth, for a poor ship's boy, younger than I, was hanged. However, it matters little now.

I pass over the time we spent on this portion of the coast, vainly waiting for the ship that never came. We accustomed ourselves to go without clothes, like the Indians, and they taught us to hunt and what roots and berries were fit to eat. On the other hand our cutlass and tomahawk were very useful, as they had only tools of blunt stone. We kept our clothes carefully, in case of being rescued, but in the course of nearly two years this hope grew faint, and then a bold project entered my head. I began to think that to the north this great Terra Australis must run up very close to Java, and that, if we could make our way there, we might be able to cross by the aid of a raft or canoe to some of the islands and get in the track of the Company's ships. ships. Moreover, the blacks, pointing to the north, had told us that up there lived people who wore clothes. Not like ours, but still they did not go naked. Inquiring still further I found that these people lived on the same land that we were on, the natives being confident that there was no big water to cross. They had never seen these people themselves, as they were a long way off, but they had heard of them from other Indians.

Paul was quite ready to go, when I confided my plan to him, for life amongst these poor Indians was of the most sordid kind, and we could not stand the torment of the swarms of flesh flies, as could the Indians. They had, however, been very kind to us; for, after all, they could have murdered us at any time and secured the cutlass and hatchet, which they much coveted.

I consulted with Paul how we could reward them, and we finally smashed up the old water-keg, which was now almost useless, and breaking the iron hoops into convenient lengths for knives, distributed them amongst the men of the tribe, who were more delighted with this than if we had given them wallets full of gold.

We had vessels chopped out of soft wood for carrying water, we had learnt how to make fire with two sticks, one old man was coming with us as far as he knew the country, and they gave us a stick with notches cut on it which would ensure our friendly reception by the neighbouring tribe, of whom we had met some members when on our hunting excursions. So we left these poor Indians, who had succoured us in our misery and helplessness, and but for whom we would have died of starvation on that barren coast. They wept and wailed when we turned our faces to the north and left them, for these Indians are like children, easily moved to show emotion, either of anger or grief.

The old man stayed with us three days, then he returned, and we were left alone with an unknown world before us. We journeyed but slowly, for we had to hunt for our food as we went, and that consisted mostly of roots and small vermin, although now and again we managed to secure a large and singular animal which, although possessing four legs, progresses on its hind ones alone, in a series of astounding leaps. It was the time of year when there are many thunder-storms, so that we did not suffer from want of water, and this was of great assistance, for in this dry and hot climate thirst is to be greatly dreaded. We passed through the territory or hunting-grounds of the tribe next to where we had been living without seeing any but a few scattered males, who, as they knew of our existence, did not trouble us or express surprise.

It was a rough journey and we were nearly starved several times. At last we came to a tribe who displayed great hostility at our appearance although none of the others had done so. In fact one tribe had entertained us most hospitably for many months during which it rained incessantly. These Indians, however, would not let us approach them, although it seemed to me that they displayed more fear than anything else.

This made me think that perhaps we were drawing near to the neighbourhood of the strange people who, being evidently more civilized, would in all probability be feared by these other Indians. This I afterwards discovered to be the case.

We found it much harder travelling amongst these hostile or frightened tribes than before, also the days were much hotter and the sun now went right over our heads at noonday so that we had no shadows, which frightened Paul, although usually a bold fellow enough. Moreover, he began to be afraid that we were approaching the country of the giants who had slain the Company's sailors, and I confess that I had my fears of it as well. We fared miserably, as I said before, for not only had we to hunt for a living, but the Indians of these parts are extremely treacherous, and would follow us for miles, seeking an opportunity to drive their lances at us, and another weapon they had, made of bent wood, which made a whirring noise as it flew, and was very hard to avoid. Fortunately, we had now acquired as much practice as these savages, and I warrant they did not come off best in any fair encounters that we had.

Still, it was weary work having to be always on the watch, and dragged us down sorely. At times we followed the sea shore, when the sandy formation of the coast allowed it, then again we would be forced back into a desolate region of rocks and thickets.

It must have been two years after leaving the place where we were marooned that we came to a hilly, broken region, whereon there were many of the trees that grow straight up for nearly fifteen or twenty feet and then have tops like bunches of grass. The blacks, our first friends, had taught us how to find out the eatable parts of these trees so that we fared better; and, strange to say, in that region we found no inhabitants, nor traces of any. No old camps, no marks of their stone tomahawks on the tree trunks, no traces of man at all. Although this made us wonder it was a great relief to us; and on that account game was plentiful, there being no Indians to keep the animals in check. So we grew stronger and in better heart, travelling slowly and resting often.

The weather was delightfully fine and water plentiful. In this country there is very little difference in the seasons, save that one part of the year is wet and the remainder dry. The rain comes from the north-west, and during the dry months the wind blows from the exactly opposite direction, namely, the south-east.

IT was early one morning that we suddenly came to a Rock on which we both caught sight, at the same time, of a rude carving of a man's head. Much startled, for it was the first sign of human occupation we had seen for some time, we examined it carefully; and we both were struck by observing that this head was not a copy of the natives of the country we had passed through. For these Indians are all most ugly, having blubber lips, flat noses, and low foreheads; but this head was that of a handsome man although without any beard. It was carved in the perpendicular face of the Rock, and the countenance bore a somewhat severe expression; in fact, after such a long and rude separation from any of our kind, both Paul and I felt somewhat awed as we gazed at it.

The Rock bore no other mark nor inscription save this solemn, life-sized head. It was almost on the crest of a rise, and no sooner had we passed it, than we came on to a beaten pathway on which were fresh footmarks, not naked like an Indian's, but more resembling those of a boot without heels.

I confess that this sudden coming upon the fresh traces of a civilized race so unmanned both of us that we felt a strong inclination to beat a hasty retreat. For you must remember that we had now been about four years living either with savages or by ourselves in a wilderness.

"Shall we follow the path?" I whispered to Paul, for I felt afraid to speak loud.

He looked around and then answered in the same low tone:

"Let us look over the ridge."

I nodded assent, and carefully and cautiously we advanced to the top. Hiding behind a heap of rocks we looked over. What did we see?

The ridge we were on sloped abruptly down the other side, into a beautiful open valley, through which ran a broad river. We saw green patches like cultivated fields, thickets of tall trees, low houses with white walls, and, above all, human beings, clothed and apparently wearing a kind of head-dress. Paul and I gazed speechless with amazement. Then, to my astonishment, he burst out crying and sobbing, and I could not help but follow his example.

When we were somewhat calm, we retraced our footsteps and, having repassed the Rock, halted to debate how we should best approach this strange people. All through our wanderings we had carried with us our jerkins and breeches that we might not appear naked before any civilized race we met. We had, of course, never worn them, and they were still in a fair state of preservation, though weather-stained. Some distance back we had crossed a small runlet; to this we returned and proceeded to make our toilet as best we were able. We washed ourselves carefully, and then did what we could to put our wild hair and beards in order. This was hard work, for the cutlass was too blunt for such work; but by lighting a fire and using the glowing ends of sticks we singed each other's redundant locks down to fair proportions. After we had dressed ourselves, feeling very strange in our unaccustomed clothing, we shook hands with each other and went to meet whatever fate was in store for us.

We had scarcely risen to our feet when we were alarmed by a loud outcry from the very spot on the ridge we had just left. Then followed a strange sound, like the blowing of a horn, and after that all was still.

I said to Paul:

"Let us go on and get it over."

He assented, and we walked up the ridge.

When about half way up we saw a party of men approaching. They were dressed in a garment like a long shirt, belted round the waist, and wore small turbans. They were all armed and advanced rapidly towards us; one man in front, who wore a shell slung over his shoulder ( which was the occasion of the noise we had heard ), was pointing to the ground. Evidently it was the discovery of our barefooted tracks that had alarmed them. So intent were they in looking on the ground that it was not until they were comparatively close that they observed us. They stopped short, in silence, although some lifted their weapons.

We made up our minds for instant death, and stood awaiting it, our only weapon being the almost useless cutlass, which I had thrust in the belt of my jerkin. The tomahawk had long since been worn out, and we had thought it better not to carry native weapons.

To our intense astonishment one man suddenly uttered a shout, and all the raised weapons fell. The cry was taken up, and whilst some ran back towards the valley, the others approached with smiles and gestures of welcome. To this, you may be sure, we were nothing loath to respond, and we soon found ourselves being conducted in state towards the valley.

The man who seemed to be in authority spoke volubly in his own tongue, but we could only shake our heads in reply. I noticed that all the party wore sandals of hide, made, as I found out afterwards, from the skin of the jumping animal I have already spoken of.

We were led in a friendly fashion past the Rock with the head carved on it, and then it was that I remarked for the first time that all our escort were beardless, like the head. Both Paul and I, as I may here well state, were fair men, like most of my countrymen, and although our skins were burnt nearly black, our blue eyes and yellow hair showed at once that we were not native Indians.

We were led down into the valley by a broad well-trodden pathway, and on reaching the foot found many people assembling to see us, having been roused by those who ran back. I noticed but few things then, for our excitement was too great, only that the women wore a garment like the men, and the men being all beardless, the only distinction in the appearance of the sexes was that the women wore their hair long, prankt with flowers, parrots' wings, and other adornments.

We soon approached a larger cluster of houses, which I supposed to be the heart of the town, although the town was scattered all up and down the valley. The houses were much the same in design, being but one story high, with flat roofs; but this ugliness was relieved by the sides being made sloping, like the sides of a pyramid. Some of the houses were larger than others by reason of having wings thrown out. They were built of mud and coated with a kind of whitewash to preserve them from the rain. There were flowering shrubs and beautiful trees everywhere, for the valley seemed to be most fertile.

Presently we approached what appeared to be the largest of the houses in the town, if such a scattered lot of houses could be called a town. There seemed to be a good deal of bustle going on, and when we arrived close the crowd parted and a fine looking man came forward, dressed but little better than the rest, with the exception that his turban was bright red whilst all the others wore white.

He approached us eagerly and looked curiously at us, then said something in a language different from what the others had been using, which sounded somewhat familiar to me, but which I still could not understand. He repeated it, and catching a word that sounded like "ar-me" I said it after him. This delighted him hugely, and he looked at me so kindly that, instinctively, I held out both my hands which he seized and shook warmly, then, leaning forward kissed me on both cheeks. Paul followed my example, and all the people standing around seemed as pleased as possible.

The man with the red turban—whom I may as well say at once was the chief, King Quibibio—led us into the house. For the moment we could scarcely see, the room being darkened to keep out the flesh-flies, which here, as in all parts of Terra Australis, are the greatest possible torment. But as they will not enter a darkened room, the Quadrucos, which is the name of these people, keep their houses darkened. Our eyes soon grew accustomed to the dim light, and we found the interior delightfully cool, on account of the thickness of the walls. There were skins and other kinds of mats about the floor but no seats of any kind, for these people always sit or recline on the ground.

The king motioned us to be seated, setting the example by lying down on a rug. He then called out an order in his own language and a boy came in with two cups made of shells, filled with what I now know to be green cocoa-nut milk. After being so long used to tepid, brackish water I thought it the most delicious beverage I had ever tasted. The boy took back the empty cups and presently came in with a large earthenware bowl of water. He washed our feet, which we submitted to quietly enough, and then proceeded to fasten on each of us a pair of sandals, such as were worn by all the others. This seemed to give the king the liveliest satisfaction, and after motioning the boy to leave he resumed his attempts at conversation.

I may as well here mention that the investiture of the sandals made us members of the family. The meaning of it I will describe later on.

Pointing to himself the king said, "Quibibio", then he pointed to me and I replied, "Diedrich", this, after some repetitions, he succeeded in mastering. Paul was much easier, and then we practised on the king's name until we had it perfectly.

We now had time to look about the room, which was spacious and lofty, and although destitute of any furniture but the rugs and mats, seemed exactly suited to the climate. Doorways opened in two or three directions, and before them hung curtains or screens of reeds. Seeing our curiosity the king led us outside, through the doorway by which we had entered, and taking us a little distance away pointed to the wall. We then saw one reason why they were made sloping. Shallow steps, or rather a stairway, was cut in them to enable the inhabitants to easily reach the flat roof.

Quibibio ascended, and we followed him on to a flat roof surrounded by a low parapet. I never saw a lovelier sight than that beautiful valley presented. The white houses seemed to nestle in clumps of verdure, the cultivated fields, though easily discernible, were not separated by walls, for these people possessed no domestic animals, and they rather regarded the fields as serving as a lure to bring in the big jumping animals from the neighbouring hills. It was a most peaceful scene, and, coming to it suddenly, as we did, out of the great desolate wilderness, we could scarce believe but that we were dreaming.

ON descending we found an ample repast laid out on the floor. It consisted of various kinds of game, birds, fish, and boiled herbs. We also found awaiting us two more people, whom Quibibio, by signs, gave us to understand were his son and daughter. I was rather astonished to find these young people so old, as I had taken the king to be only about middle age, but the beardless faces were very deceptive. In fact the only difference noticeable between the Princess Azolta and her brother, Prince Zolca, lay in the length of the hair, and the fact that Azolta wore flowers round her head.

The Quadrucos are a fine race, and as Azolta was a most beautiful girl Paul could not keep his eyes off her during the meal, until I had to tell him that he might give offence. Her twin brother, as I afterwards learned he was, appeared to be of a lively disposition, and to greatly regret that we could not understand each other.

The meal being finished the attendant boy brought round a basin of water for us to wash our hands in; and we then arose from our reclining position, which I and Paul found very irksome.

Azolta retired, as also did Quibibio, leaving his son, Zolca, to entertain us. This he did by smilingly inviting us to walk out. We took our way down a beaten track by the side of the river, which was a broad, sandy stream, with long reaches of water. We soon reached a gorge through which the river descended, or at least the small stream it then was, in a series of cascades. Zolca led us up an easy ascent by the side of this gorge, and we suddenly found ourselves within sight of the ocean. At our feet lay a well-sheltered bay, overlooked by the rise we were on, and beyond was the sea unstudded by a sail. Some large-sized canoes were lying near the beach, and on the rise on which we stood were several men, some with shells slung across their shoulders. Zolca waited quietly until I happened to turn my head slightly, and then I started with surprise, for close to us was reared a wooden Cross, some thirty feet in height.

We approached, and when near it Zolca bent his knee as Roman Catholics do. Paul and I, being of course of the Reformed Religion, did not do so, until it struck me that it would be policy to follow Zolca's example. I whispered this to Paul, and we then both knelt down.

Then we examined the cross. It was firmly put together and well planted in the earth; but the inscription that had been cut on it, of which I could but detect a few letters, had been almost entirely defaced by the weather. The cross was made of a ships' spars, and must have been a prominent object from seaward.

Zolca patted the post that formed the cross, and said, two or three times, a word that sounded like "Gon-vil". This awakened a chord in my memory, which I could not explain until it suddenly flashed before me. And I saw myself a boy in old Harlem, pondering over stories of adventure; and amongst them that of the Norman captain, Paulmier de Gonneville, who discovered a great south land, where he stayed with the natives for six months, finding them very peaceful and gentle, although warlike towards other tribes. My memory now becoming clear, I recalled reading of the great Cross he erected, and how he had taken a prince of the country to France, promising to return with him, which, however, he was prevented from doing.

This, then, was the land, and thus was our friendly reception accounted for. It was more than one hundred years since Paulmier de Gonneville had been there, but the tradition that he would return had evidently been faithfully handed down and preserved. I now saw what course to pursue, and felt thankful that my boyish love of reading about discoveries had given the information.

"Gonneville! Gonneville!" I said eagerly, and the delighted native repeated it. Then he insisted on our returning with him, and on arriving at what may be called the palace, he produced a Latin missal, inside of which I could trace in faded characters:

"Jean Binot Paulmier de Gonneville. Honfleur, 1503."

After deciphering it I read it aloud, much to the pleasure of the

two natives, for Quibibio had now joined us. Zolca next produced an

old-fashioned, short sword, evidently of French make, but there was no

inscription on it. Struck by a sudden thought, I drew the old cutlass

I had carried so long and presented it to Zolca, making him understand

that it was a present. He seemed at first so pleased with the wretched

weapon that he could only look at it with delighted eyes; then he put

his hands on my shoulders and kissed me on both cheeks, a French custom

handed down, I presume, from Gonneville's time. I heartily wished the

performer had been his sister, Azolta, who had entered the room and was

gazing shyly at us.

I now, having got a footing, as it were, tried to show them by signs, and drawings on the ground with my finger, what had happened to us; how our ship had been wrecked, how we had lived amongst the Indians—at which both father and son showed signs of disgust,—how we had walked on and on until we came to their country. They seemed to readily comprehend it all, and from that time we were as one of the race, and from the date of giving him the cutlass Zolca was my brother. We at once assumed the Quadruco dress, and every one was our friend.

I will now give some account of these people, it being of course what I have since learned.

They are, or, alas! were, of a light colour, with dark hair and eyes, and as I said before, beardless. They were well built, averaging about five feet eight or nine; extremely good looking, especially the women, many of the young girls being nearly as beautiful as Azolta. Their dress, which was woven out of the woolly pod of a bush, was a single garment like a long shirt, with a girdle round the waist; it reached a little below the knee, and was the same in both sexes. The men wore a turban, but the women wore only ornamental head-dresses of flowers and feathers. They had little occasion to work, the valley being so fertile, and the hunting was merely a pastime and an exercise. The men had but one wife (Quibibio's was dead), and family affection seemed very strong between them. They had a simple kind of religion, which I don't think was much thought of, and consisted merely in a belief in a Great Spirit, who sometimes was kind, and sometimes angry. They had plenty of dances and games, but very few rites or ceremonies.

The tradition of their origin was that their forefathers, with their wives, came from some far-away island in two large canoes; that they found the valley they lived in almost uninhabited, save for some scattered families of savages who fled at sight of them, and they settled down and had lived there ever since.

Of their wars with the Indians, and with two other nations who came from the sea in big boats, I shall have to speak presently, as I had to take my part in them.

The cocoa-nuts growing in groves up and down the valley of the river were, they told me, brought by their ancestors from the land from which they came. This I could most readily believe, as we had seen none throughout our long journey; nor would the arid country we passed through have supported them. So far as I could make out the Quadrucos, at the time of our visit, numbered 800 souls.

I applied myself diligently to learning the language, and with two such teachers as Zolca and his sister it was easy work. Paul did not make such rapid progress, on account of his want of education, but he could soon make himself understood.

One day Zolca came to me in great glee and showed me the old cutlass, polished up and made as sharp as a razor. Little did I then think to what use I should one day see that keen blade put! I asked him who did it, and he took me to a large house I had never yet entered. In it we found many men at work sharpening and cleaning swords, hatchets, and heavy knives, but all very coarsely and roughly made. I was astonished at the sight, for I had no idea that they had any knowledge of metals, but Zolca informed me that these weapons had been taken from the dead bodies of their enemies, belonging to the two tribes who came from the sea and fought them.

By this time we could fairly understand each other, and Quibibio approached me on a subject which had evidently been troubling him.

"When would I teach them to make swords?"

On inquiry it turned out that de Gonneville when he left promised to return, and told the then king, Arosca, that he would bring back men who would teach them how to make metal, and also how to fight like his people.

I hesitated before replying, and then told the king that I was afraid no metal existed in his land, but that Paul and I would go. through the weapons they had, and teach his people how men fought in our country. In saying this I, of course, relied upon Paul, who had once seen military service. This answer satisfied Quibibio, and I held a consultation with Paul, who readily agreed to do something that would raise his importance.

Next day, then, we inspected the weapons they made themselves, putting on one side those captured from the enemy. We found that not only did they all possess serviceable bows and arrows, but, in addition, most of the men were expert slingers, and all could throw the lance with precision. They had, however, no system of fighting, each man acting independently, and this was due to the enemies they had had to deal with.

On first coming to the land, some hundreds of years ago, no doubt, their only foes were the native Indians, whom they called Papoos, and these they easily vanquished. Still, however, they had occasional trouble with them, so a beaten path was marked out around the settlement, and this was traversed twice a day by sentinels. As every Quadruco wore sandals, it was easy to detect a barefooted footmark crossing the path, and it was this which led to our detection. The Indians, however, grew to fear them greatly, which was the cause of the abandoned tract of country Paul and I had passed over.

Then a fresh enemy arose. Men came from the sea in great canoes, half the size of Gonneville's, and nearly as high out of the water. These men were of two races, and although they both attacked the Quadrucos, they also fought between themselves when they met.

Fortunately they had not appeared until the settlement was numerous enough to resist them, and as yet, though some of them had actually landed, none had succeeded in getting beyond the shore. These people used bows and arrows, swords, and another weapon which, by its description, I took to be a blow-pipe. A look-out was constantly kept for these marauders, and the shell which was ingeniously turned into a trumpet was sounded as the signal of danger.

Paul was now made captain, and took the work with pleasure, for I think he felt sore that I had been made so much of, and was anxious to also attract admiration.

With my assistance he divided his men into archers, slingers, and a small body of swordsmen, all of them also being armed with lances. In addition, finding that they had no notion of the use of the shield,—strange to say, for even the Papoos knew about that,—we set some of the artificers to work and soon had some light wooden shields covered with hide, which we taught them how to use, for I had been trained to arms in Harlem, as all youths of my position were.

Time passed quickly and happily. The Quadrucos were delighted with their new employment, and as for me, so long as I could look in Azolta's dark eyes and hear her soft voice, I wanted no more.

THE season of rains had passed over, and the valley was one mass of verdure and flowers. Azolta, Zolca, and I were wandering along in the early morning when the harsh note of the war-shell came from seaward, and was taken up and repeated again and again. It was a most discordant sound in such a scene of peace, and no wonder that Azolta started and clung to me. Zolca's eyes blazed, and he ran towards the men who were approaching with the tidings. Two large vessels had appeared on the horizon, evidently bearing down towards the settlement.

Thanks to our constant training there was no confusion in gathering our forces. The archers mustered together under Paul; I had charge of the slingers; and Zolca led the small body of men armed with swords. and shields. The women had been instructed to prepare plenty of food, and also to have long strips of the stuff of which they made their dresses ready for the wounded. Then we marched to the shore, old Quibibio leading.

The two vessels were still at some considerable distance, so we halted on the top of the rise and watched them approach.

Suddenly I recognized our coming enemies from old engravings in the books of travel, which I had read. They were Mongols I could tell by their strangely-shaped vessels, with their huge lop-sided sails. I had seen many pictures of these ships and of the people. I turned to an old Quadruco near me and asked:

"Have not these people heads like this?"—showing the back of my hand—"and tails on their heads?"

"Yes," he answered.

So I knew then that these were Mongol junks that were approaching, and had not much fear, for I had heard that my countrymen in Java used these Mongol people to work in the fields.

We had erected strong barricades at the foot of the low hills commanding the bay, and along here the slingers and archers were posted in alternate parties. Zolca and his swordsmen lay in readiness to rush down and encounter any who might succeed in reaching the land in spite of our volleys of arrows, spears, and stones.

As there was still ample time, the women went round distributing food and drink to the men, and it was a pretty sight to see with what coolness and cheerfulness they did it. But the fact was that Paul's organization, rude as it was, had infused great confidence in them, after the loose disorderly way they had fought before. Azolta herself brought me some food, and when she looked at me before going away I saw that there were tears in her glorious eyes. Then before I knew what I was doing, I caught her in my arms and kissed her. And this, on the eve of battle, was our first kiss.

The wind now dropped, and the Mongol pirates put out sweeps and came down more rapidly. Evidently some amongst them knew the way, for they came straight into the bay, one leading, and as soon as they got as near the shore as they dared they anchored, lying close alongside each other. All our men kept under cover and maintained a perfect silence, as they had been ordered to do. In this silence we could plainly hear the shouts and orders of the pirates who seemed to be all talking at once. I had small concern as to the result, for I had heard the Company's sailors speak most contemptuously of these Mongols. In this, however, I erred.

Heavy, clumsy boats were now dropped into the water and filled with men, and some of them pulled towards my side of the bay, for Paul and I were now posted on opposite sides. I noticed, however, that only about a third of the boats left the ships, the others remaining as it were in concealment, between the two vessels. This was a simple trick which had however deceived the Quadrucos before and cost many lives. Namely, by a feigned attack they had induced all the Quadrucos to rush to one point, and then sent the remainder of the boats to an unguarded spot. We were prepared for this, and the pirates were destined to receive a lesson.

On they came, three boat-loads, propelling their craft by standing up at the oars and facing the bows. I allowed them to come so close that my men got impatient; but I had my reasons for this, and was delighted to see that all the men at the other side of the bay kept close. When the boats were in quite shallow water I gave the signal, and such a storm of arrows, spears, and stones burst on the astonished Mongols that they turned tail at once. The leading boat had received such a hail of missiles that the men were too staggered to stop her, and with the way she had on, she grounded.

This I had anticipated, and giving the signal agreed on, Zolca and his swordsmen came bounding down, Zolca yards ahead. The Mongols showed but little fight and were cut down and killed without mercy, whilst some of the Quadrucos received but slight wounds. My men kept up a relentless fire on the other two boats as they clumsily turned round, and they must have finally reached their ships half full of dead and dying.

While this was going on Paul told me he had the greatest difficulty in keeping his men close, and had he not succeeded it would have spoilt all. The Mongols, although making a great clamour on board their junks at witnessing the repulse of their party, evidently believed that their stratagem had succeeded, for the remainder of their boats, five in number, now made for what they thought was the unguarded side of the bay. Zolca and his men immediately started round to assist Paul, and I and most of my men followed; which was fortunate, for the leader of this party was more cautious, and ordered his boats to land at different points, so that the attack was at five places at once.

This, however, did not save him or his force, for from their cover Paul's men suddenly assailed them with such a hurricane of arrows, &c., that they dared not approach. This leader, however, kept his boats out of the very shallow water and ordered a number of his men overboard, to land everywhere. The manoeuvre caused delay, and by this time Zolca had arrived, closely followed by me and my men, and the pirates struggling in the water, unable to use their weapons properly, were all killed, excepting a few who managed to regain their boats which made back for the junks.

None of our men had been killed and only a few slightly wounded, so well had we taught them to keep under cover, whilst the pirates had lost a boat and over a hundred men killed, besides the wounded. By the capture of the boat we gained a great number of weapons of all kinds, and from the dead bodies many more were taken.

Naturally there was much rejoicing amongst the Quadrucos, and when I met Azolta she kissed me of her own accord.

Meantime the pirates showed no signs of leaving, and, as I now know, these piratical junks were packed full of men.

Paul drew my attention to what they were doing, which appeared to be throwing one another overboard. He explained to me that they were simply killing those who were very badly wounded, and throwing the bodies overboard, this, seemingly, being their barbarous practice.

We next held a conference and came to the conclusion that the Mongols intended to wait until night before attempting another onslaught. After our men had eaten a good meal, and had some relaxation, we formed small camps round the bay, where it would be handy for them to reach their posts when wanted; a close watch being, of course, kept on the pirates.

The bay was now alive with sharks, attracted by the dead, but all the bodies we could get I ordered to be taken to the rocky headlands and thrown into the outer sea. So we soon got rid of the sight of these hideous, yellow, flat-faced monsters, with their bald heads and black tails.

I now called Paul and Zolca on one side and communicated to them an idea which I had conceived. The moon rose about two hours after dark, and it was most likely that the pirates would make their attempt shortly before daylight. I therefore proposed to utilize these two hours of darkness by attacking in our turn. It was now only an hour or so past noon, so that we had ample time to prepare. When I explained my plan Paul grasped it at once, and Zolca, although he did not fully comprehend how it was to be done, would, after the success of the morning, have done anything we desired. I sent for some of the most expert bowmen, and with them we went back to the town, which was rash; but then we could have reached the shore in time had there been any sign of another attack. Paul made these men practise shooting up in the air, so that the arrows would fall straight down as if from a height; he measured off a certain distance, and after a short time they grew very skilful at it, making the arrows drop almost exactly within the mark every time.

Meanwhile Zolca and I started some of the women to make three huge bundles of dry palm-leaves; and these, when finished, were bound together at the top, and a loop attached. We then put them to soak in the palm-oil that we used for our lights at night.

Our preparations were now complete, and we had nothing to do but wait and watch until nightfall. There is but little twilight in this country, and as soon as it became too dusk for the Mongols to see us we sent men to collect all the available canoes. When quite dark Paul and I took the smallest canoe and set out for the pirate junks. Our intention was to cut those boats adrift which had not been taken on board again, but were towing astern. We did not paddle, but I propelled the canoe from the stern by means of a lance, while Paul lay in the prow with one of the sharpest swords we could get, ready in his hand. It was very dark, and once under the tall side of the junk we were comparatively safe.

It was a strange feeling to be so close to these wretches, and hear them jabbering and quarrelling overhead. No order appeared to be kept, for they all seemed talking at the same time and none listening. Cautiously we made our way under the stern, which, sloping outwards, completely sheltered us. Here we noted what we wanted to see for our next move, and then I gently impelled the canoe towards the boats. The tide was rising so that the junks swung shoreward, which was just what we wanted. Four boats were towing astern, and after a few noiseless cuts from the keen blade they were floating towards the land. No alarm had been given, and in a few moments the three boats belonging to the other junk were adrift and following the first four.

We did not wait any longer, but I sculled the canoe straight away at right angles. It was lucky I did so, for a tremendous uproar arose on both ships, somebody having caught sight of the boats drifting away. Thinking that whoever had cut the boats loose must be on board, they directed a shower of arrows after them, taking no heed in our direction. Some of the pirates jumped overboard, but doubtless the sharks took all save one, and he actually swam to one of the boats, and was there transfixed by an arrow from one of his own countrymen, for his dead body lay in the bottom when the boats stranded—which they very soon did, for the tide here rises thirty feet or more and makes very rapidly.

We landed at another part of the beach and began our preparations for the real assault. Zolca was delighted with our safe return, and as our time of darkness was but short, we hurried on with everything.

The hubbub on board the junks still continued, but of that we thought little—they could do no more.

Our picked bowmen were drafted into the boats, and we soon had them stationed at what we calculated was the right distance from the ships. We had judged most admirably, for by the shouts of alarm and fear we could tell that the arrows were falling on the pirates like rain from heaven. Zolca was in charge, and by our instructions he kept up the fire intermittingly, that is to say, he would give them one volley, then, after an uncertain interval, another, so that they did not know when to expect it.

Now our turn came, with the three bundles of oil-soaked palm-leaves and some live coals carefully covered up, we started in the same canoe that had done us such good service already. We pulled to Zolca's boat, and he ordered one vigorous volley which must have made the Mongols skip below again. Then we shot like an arrow, straight as we could paddle, for we had determined to throw off all disguise. The stern of the junk where we had been before was reached in safety, and on the great, creaking rudder we hung one of our fire-bundles, the other two we suspended anywhere we could, driving them fast into their places with three swords we had brought with us for the purpose. Having a lance with us, with a bundle of this same stuff at the head, we floated back a bit, lighted this at the hot coals, and touched off the fire-bundles. All this we were enabled to do unobserved, for the sterns of these junks overhang the water a long way, so that it was like a roof over us; moreover, the pirates were all under cover, expecting another shower of arrows.

The oil-soaked bundles burst into immediate flame. Paul hurled the burning spear on board, where it set fire to the roof of their cooking-house, and we paddled desperately back without any harm. Zolca ordered one more volley, and we drew out of the circle of light and waited.

I WAS in great hopes that if the junk took fire properly it would communicate the flames to the other one, for these unwieldy vessels are built of most inflammable materials. This was not the case. The other junk's crew cut their cable, and drifted out of reach before the fire got fierce hold; then they put out their sweeps and went out to sea, leaving their companions to their fate. The moon now rose, and we had a full view of the scene. Truth to tell, the spear hurled on board by Paul had done more damage than our fire-bundles. It had ignited the top of the cook-house, and from there it had run up the huge sail and masts, whilst the only damage our fire-bundles had done was to burn the rudder and a hole in the upper part of the stern. This, however, was sufficient to put the junk at our mercy.

The Mongols were apparently working hard to extinguish the fire, but without much avail, for the masts, rigging, and sails were soon all aflame, and presently came tumbling about their ears.

Zolca had all the boats drawn round in a circle to prevent the escape of any of the pirates who might jump over, whilst others on shore watched for the same purpose. I did not see any try it, although the junk burned for some hours, until she seemed to have nothing left to burn. Still she did not sink, and we kept our watch all night. When daylight broke she lay there, black and smoking, but with no signs of life on board. I feel pretty certain that when they saw they were doomed, most of them voluntarily sought death in the flames, for I have since learnt that suicide is a custom of these people. Zolca and some of his men boarded her, and found that she had been burnt clean out, nothing but the hull being left.

Whilst engaged in this we heard a great shouting from the shore, and soon learned that the other junk had run on a reef of rocks just outside the bay, and was now lying on her side with the waves breaking over her. As there is a tremendous surf at this place there was little chance for any of the pirates to have escaped, but to make sure Zolca placed a guard there; but none were ever seen, and the waves soon made short work of the wreck. When the tide was nearly full we towed the burnt vessel as far up the sand as we could, and there broke her up, and got a quantity of iron from her.

Things having come to this happy issue, and all our enemies being destroyed,—that is, for the time, for we did not relax any vigilance in watching for others,—life went on easily and happily, especially for me with my beautiful Azolta.

Soon after our victory over the Mongol pirates Azolta and I were publicly betrothed amidst great rejoicing. Quibibio now seemed to have reached all he had desired. He had been the one to witness the return of men from, as he supposed, De Gonneville's country, who had taught his people how to fight, and now I was betrothed to his daughter, and had promised to live and die in his country. Zolca, too, was untiring in his devotion to me, and would have laid down his life for me.

Paul had set his affections on a very pretty girl, the daughter of one of the principal men, and he was betrothed at the same time. This betrothal, according to the custom of the race, was to last one year, when the marriage ceremony took place.

That year passed peacefully and quietly. Paul and I had a house allotted to us, and wore the red turban; but I now began to notice a change in my fellow-exile. So long as there had been hardships to encounter, and fighting to look forward to, he was one of the best and cheeriest of men, although but a rough sailor without any education. But now the life of ease and indolence seemed to bring all his worst qualities to the front. He had no resources to fall back on, although I tried hard to interest him in the work I was doing, namely, trying to teach the natives new arts and industries. I had succeeded in making a rude kind of paper, and after that the manufacture of ink was easy, and with the pinion feather of a bird for pen I had begun to teach Zolca and others the use of written characters.

Paul took no interest in this. He sighed for the rude joys of his former sailor life, the strong drink, the dancing, the singing, and rough jokes of boon companions. Of dancing and singing we had plenty, but the graceful flower-dances of the Quadruco girls did not suit him when he remembered the clumsy jigs of his sailor days.

One day, when I was trying to rally him, he replied hastily that he wished he had been hanged at the yard-arm of the Sardam frigate before he had come to rot in this place. Then he flung out of the house, and I saw him no more that day.

I was in hopes that when he was married he would become reconciled to our quiet life, where, if we were cut off from the world, we at least were well fed and enjoyed a beautiful climate. But this was not to be. That evening he came to me and proposed that we should build a small vessel out of the timbers of the junk, and make our way north to Java. I reminded him that we should probably be hanged at once as two of the mutineers of the Batavia. But he replied that by this time they must have forgotten all about us.

"And if not," he said, sinking his voice, "I have knowledge of what will purchase our pardon readily."

"What do you mean?" I asked.

"There is this valley, and—there is more."

While the tempter thus spoke I saw my old home in Harlem, my parents, who had doubtless mourned me both as dead and guilty, and a longing to return came over me. Then the loving eyes of Azolta, soon to be my wife, blotted out the picture, and I knew my duty.

Since my exile and residence amongst the Quadrucos I had learned to look at things from a far different stand-point than the ignorant boy who sailed from the Texel. Then I saw no harm in the Company occupying the lands of the natives, dispossessing and making slaves of them. I had been taught no better. Now I saw the wickedness of it, and the idea of these peaceful, happy people, who had sheltered us in our distress and treated us with honour and distinction, being handed over to the rapacity of the Company, and the tender mercies of its servants, struck me with horror, and I vowed in my heart that I would fight to the last drop of my blood in their defence, even against my own people.

"What do you mean by more?" I asked Paul.

"There is gold here," he returned. "Plenty of it. I found a lot of stones with veins of the metal, when I was out hunting one day."

He went to the corner where he slept and brought out some white stones in which he showed me yellow streaks which certainly looked like gold.

"I have seen it before," he said, "though not in this shape."

Now this determined me more than ever. Should my countrymen learn of this, nothing would stop them from swarming over the land, and the fate of the Quadrucos would be settled.

"Paul," I said, "have you no gratitude for the people who welcomed us and treated us so well? Do you not know what will happen to them if the Company hears of this place, and establishes a Factory here? Can you say that you have the heart to dream of such a plan?"

"Right well do I know what will happen, Diedrich; but it is a lot that must be theirs sooner or later; you yourself must confess that. Some discovery-ship will poke her nose into that bay some fine morning, and then the thing is done."

"But don't let yours be the hand to do it," I replied.

"I am wearied here," he answered, "and above all, it is so easy to get away; where those clumsy junks go, we can go, and what Master Francis Pelsart did in his boat, from where the Batavia's bones lie, we can do easily from here in a better boat, which we will build."

"I would sooner cut off my right hand than consent," I replied. "These people have adopted us, and here I will live and die!"

"For the sake of a pretty savage!" sneered Paul.

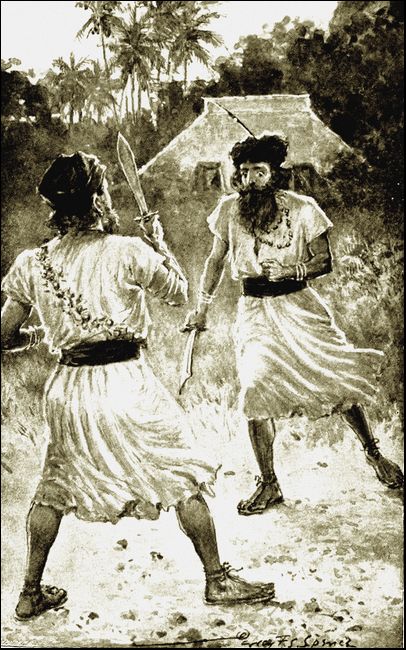

Mad with sudden rage at this allusion to Azolta, I drew the short

sword I now always wore, and was about to fall on Paul, who drew his

and stood upon the defensive.

Paul drew his short sword and stood on the defensive.

For a moment we faced each other, then Paul dropped the point of his weapon.

"Let us not quarrel, friend Diedrich," he said, "we have been through too many perils together to try to slit each other's skins now. I will forget this mad scheme of mine, though in truth I am tired of this life."

I knew he was but feigning, but I held out my hand and he shook it, and we returned our weapons to our belts. But from that day there was ill-blood between Paul and me.

I understood it all now. It was not the monotony of the life, for Paul was too rough to mind that; it was the discovery of the gold that had so changed him. Here it was useless to him—no better than common rock; but once free, with the knowledge of its locality, and he could enjoy himself to the end of his days.

Azolta noted my abstraction, but I could not tell her the cause, for I was meditating whether or not I should confide in Zolca. For Paul had not given up his purpose, of that I had felt sure, and although he could do nothing by himself, still he must be watched. The death of Quibibio decided me.

The old king died happy. These people did not fear death in the least. All his wishes and hopes had been fulfilled. His son Zolca, who would succeed him in the mildly paternal rule which was all that was demanded from the king of the Quadrucos, was a noble fellow; his daughter was about to be married to me, who was as an adopted son; his enemies by sea had been beaten and destroyed. He was ready to die, and he died calmly, smilingly, with the three of us kneeling beside him.

He was buried beside his ancestors, and Zolca now reigned in his place. The mourning did not last long, for death was looked upon as inevitable; and it in no way delayed my marriage to Azolta.

Paul and I were married on the same day, and I took up my quarters in the palace. Since our outbreak we had been ostensibly on the old terms, but in my heart I knew that Paul had in no way relinquished his purpose.

Zolca now being in supreme command, I resolved to take him into my confidence.

It was a long task, for I had to explain things to him which he had not the experience to grasp. In the first place I had to find out if he knew about the gold; to my astonishment he did, and said he could take me straight there. Of course he did not know about the value of gold, but he had noticed the yellow stuff in the rocks when he had been out hunting. I now explained to him that this yellow stuff was what all white men craved. That some would do anything for it. That if they came to hear of it being here they would come in big ships and take it, driving him and his people out of the valley to wander amongst the Papoos, if they did not do worse. That they would have weapons which his people could not resist. He seemed scarcely to understand me, for in his simple mind all men of my colour were friends, "amis" as the Norman captain had taught his ancestors.

To explain things I asked him what he thought the Mongol pirates would have done had they beaten us instead of our beating them.

"Killed us all," he replied promptly.

"That is what the white men would do, only in another fashion," I told him.

Then, my boyish reading coming back again, I related the story of the Conquest of Mexico and all its horrors.

"Deedrick," he said at last, that being their pronunciation of my name, "brother, why tell me all this?"

Then, though greatly loath, I told him that Paul had found the gold, and that the sight of it had changed his nature. That he had proposed to me to build a vessel and go to where our countrymen lived to the north, and bring them back and show them the gold.

"But why?" he asked, in bewilderment. "Is he not happy here?"

It was cruel work, like kicking a dog who would lick your hand, but I had to do it. I told him that men like Paul had such a desire for gold and all it would buy in our country, that they would do anything to get it; that it made them worse than the pirates; that it turned a good man into a bad man. Be it remembered that crime was almost unknown amongst these people; petty quarrels there were, but nothing more, therefore it was extremely hard for me to explain to Zolca.

I then said that we must not trust Paul; that he was bold and clever, and now that he had set his mind on it he would never let the matter rest.

"But, brother," said the bewildered prince, "why are you not like the others?"

I said that some men had stricter notions than others, and I had had very strict parents; moreover, I loved Azolta more than all the gold in the world.

Poor Zolca! He got up and walked about; then, cast himself on the ground again and I saw great tears in his eyes. It was his first experience of human nature. Of course he had never felt for Paul as he did for me, still he had believed in him. At last he sprung up and his eyes were blazing.

"Deedrick! I will kill him before he shall harm my people!"

Prophetic words!

BUT for the grief and anxiety occasioned me by Paul's conduct I should now have been perfectly happy. With my bride Azolta, and my brother Zolca, and congenial work in the instruction of the people, I could scarcely realize that I was the man, who, as a boy, had been herded with mutineers, and put ashore to starve on the unknown land of Terra Australis.

As for Paul, apparently he had settled down to married life and forgotten his plan of sailing for Java, and bringing the Company's men down to show them the gold and the fertile valley of the Quadrucos; but I felt quite sure that he meant to carry it out on the first opportunity.

My attempt to introduce the use of tables and chairs amongst the Quadrucos was not very successful. Zolca and my wife tried hard to accustom themselves to this new mode of eating and drinking, &c., but I am afraid the others only lay on the floor and looked at the furniture. They took to writing, however, and having concocted a simple code of signs, Zolca and I could communicate easily.

One morning the blowing of the war-shell announced danger from the northern side of the valley. Zolca, Paul, and I, with a body of men whose duty it was to hold themselves in readiness—for we had taught the Quadrucos not to rush on like a rabble, but to do everything according to method—proceeded to the spot. We found that several footprints of the Papoos had been found, crossing and recrossing the beaten path which the sentinels patrolled. As these were not very formidable foes, Zolca and his men proceeded in pursuit of them, and Paul and I returned. Before leaving the place, however, Paul asked me if I had seen the paintings in the caves near where we were. I had heard of them from Zolca, who professed not to know by whom they had been done, but I had never visited the place. Paul led me to it. They were gigantic figures, without mouths, dressed in long robes, with halos around their heads. There were also characters resembling written words on the walls of the cave. I imagined they had been done by the Quadrucos who first landed.

As we went slowly home I noticed that Paul seemed most friendly, he talked about the hardships and dangers we had gone through together, and what a happy life we had suddenly dropped on. In fact I never saw him more subdued and affectionate. Zolca did not return that day, evidently his pursuit had led him further than he expected.

I slept soundly, to be awakened at sunrise by my name being loudly called from outside the house. Hurrying out I found Namoa, one of the principal men of the valley, in a state of great excitement. As day broke, the sentinels on watch for the pirates saw a boat with a white sail leaving the bay. They then missed one of the largest of the boats we had captured from the Mongols.

Paul had started for Java!

I concealed all signs of emotion, and with Namoa made inquiries. We found that Paul had taken with him his wife and her two brothers. How he had wrought upon them to join him I cannot say, but they must have been secretly at work for some time, preparing the sail and mast, etc. This, then, accounted for his plausible manner the night before, to lull my suspicions to rest. Zolca's absence was another chance in his favour, and he seized the opportunity.

I treated the matter lightly, explained that Paul had only gone to try how the boat would sail, as we intended rigging masts on all of them. I surmised that he meant it as a surprise for us, that was the reason he had said nothing about his intended trip.

When Zolca returned, which he did in a few hours, having followed the Papoos for a long distance but failed to overtake them, it was quite a different thing, and his eyes showed me that the untamable savage was still latent in him.

However, I had thought the matter over, and had come to the conclusion that Paul never would reach Java. In the first place, even if he escaped shipwreck, he had a most hazy idea as to its whereabouts; in all probability he would land on some strange island, peopled with savages, and he and his party would be murdered. I considered it would be a miracle if he reached Java, unless he was picked up by one of the Company's discovery-ships. Then again, he could not carry a sufficiency of provisions and water to last him through calm weather, when he could not sail. He had spoken of Captain Pelsart's voyage in the boat, but Pelsart was a navigator with a well-built boat, not a clumsy Mongol affair; also he had a boat's crew of trained sailors. Altogether I looked upon it as a rash and desperate enterprise that only an ignorant man would undertake, and one sure to bring destruction on the heads of the parties engaged in it.

All this I confided to Zolca, who, I think, understood most of my reasoning and felt reassured. Suddenly our conversation was interrupted by the blowing of the sentinel's shell from seaward. We hastened there and, to our intense surprise, found that the boat with the white sail was returning. Now, although I was glad that this, to a certain extent, confirmed what I had already told Namoa and the rest, still I knew that Paul was not coming back willingly, and this idea was soon made a certainty, for, almost immediately, a Mongol junk came into sight. Paul was evidently running back to escape a worse fate.

I drew Zolca on one side and told him the tale I had told Namoa and urged him to accept it as the best policy. We could settle with Paul privately, meantime we wanted his help to fight the pirates. To this he agreed, and when finally the boat ran up to the beach, I hailed Paul in our own language and told him how to act. He was sharp enough to see the situation, and it was evident that the other Quadrucos had no suspicion of the attempted flight. Paul's companions would, of course, divulge it presently, but not until we had dealt with the junk, and I was anxious to avoid any disunion in our ranks with an enemy in sight.

After our last fight I had carefully gone over the bay and found out the channel leading into it. Also, that this channel passed close to one of the headlands of the bay. On this knowledge my plans had long since been formed in case of another attack. As the junk, which was much larger than either of the former two, drew near, we all took up our stations as before, with the exception that a body of bowmen under Namoa, stationed themselves on the headland commanding the channel.