RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

RGL e-Book Cover©

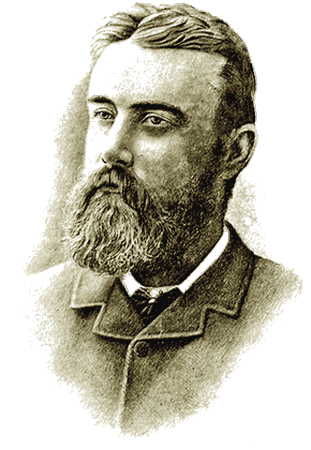

Ernest Favenc (1845-1908)

British-born and educated at Berlin and Oxford, Ernest Favenc (1845-1908; the name is of Huguenot origin) arrived in Australia aged 19, and while working on cattle and sheep stations in Queensland wrote occasional stories for the Queenslander. In 1877 the newspaper sponsored an expedition to discover a viable railway route from Adelaide to Darwin, which was led by Favenc. He later undertook further explorations, and then moved to Sydney.

He wrote some novels and poems and a great many short stories, reputedly 300 or so. Three volumes of his stories were published in his lifetime:

The Last of Six, Tales of the Austral Tropics, 1893

Tales of the Austral Tropics, 1894

My Only Murder and Other Tales, 1899

His short stories range from bush humor to horror, supernatural to strange, and to the privations of late 19th century exploration in Australia's unforgiving inland. His first two short story books (consolidated into one volume, as there is considerable overlap), are available free as an ebook from Project Gutenberg Australia.

—Terry Walker, January 2023

A PARTY of four of us—three whites and a black boy—while out on a prospecting trip in Western Australia, were induced by likely auriferous indications to push into the interior, far beyond the head of the Gascoyne. We were well equipped, and were especially lucky in the season; so we agreed, although the gold indications had failed, to go on and, if possible, work our way right through the unknown country to Kimberley. We were all experienced bushmen, and, as our horses were in good condition, there was nothing very hazardous in the attempt.

On Sunday, November 22nd, 1891, we were camped at a native well of fairly fresh water, where there was a patch of good feed for the horses, and about a mile away a small salt lake, on which were swans, geese, and other wildfowl. We determined to spell for a week in order to recruit, and, at the same time, do so without encroaching on our rations, as the game in the lake would support us.

With the exception of the flat on which was the good grass I mentioned, the country was desolate and barren in the extreme, sandy, and covered with spinifex. From a low sandhill not far from our camp a range was just visible to the northwest. It was to this point we determined to steer when we again started How far away it was, we could not determine, but it was a considerable distance, as we could only see it before sunrise and after sunset during the short clear twilight. Dan, the black boy, who came from the coast and did not understand the phenomena of the plains, used to declare that it was no range, but a cloud; and in spite of all our laughter about a cloud remaining always in one place, and always of the same shape, he stuck to his opinion.

At the end of the week we started. From various indications we imagined that we should find it dry ahead, and took what precautions we could. We left as soon as our horses had had their morning drink, and all day rode through an unvarying tract of spinifex plains and low sandhills.

By a great stroke of good luck, we came towards evening to a grassed flat between two sand ridges, where a passing thunderstorm had left a little water in a clay pan. This was just enough for our wants; but, strange to say, even from the top of the sand ridges we could no longer sight the range, although so much nearer to it. This could easily be accounted for by the formation of the country; but Dan, of course, put it down to his cloud theory. From the time we left the salt lake we had not seen a living thing of any sort, not even a lizard.

Next morning we started in the same direction, but still the country remained unchanged. Shortly after mid-day we ascended a sand ridge somewhat higher than usual, and simultaneously all pulled up at the sight in front of us. About two miles ahead was the range we had been steering for, hitherto shut out by the high ridge we were standing on.

A grim, bare, rocky range, with level but somewhat serrated summit running north and south: between us and it was a sand plain, without a vestige of vegetation on it stretching right to the rock at the foot of the range. The whole, under the fierce vertical sun, was so blinding and radiating, that involuntarily we put up our hands, as though shading our faces from the open door of a furnace.

"We'll tackle that later on," said Westall, one of my companions.

We agreed, and retraced our steps to where there were some miserable stunted gums affording a little shade Here we turned out and boiled the billy Whilst we had our meal, after relieving the horses of the packs and water-bags, we discussed our movements, and agreed to ride over to the range and examine it, leaving Dan to mind the other horses.

It appeared, certainly, as though we would have to push back to the salt lake during the night. In the afternoon we rode to the range across the belt of bare, blistering sand. It was granite, and beyond its barrier-like formation and surroundings there was nothing uncommon in it.

I turned to ride slowly one way, and Westall and James went the other. In about half an hour I returned to the point where our tracks struck the range, but could see nothing of my companions. I waited some time, and then rode slowly on their tracks. Soon I met James coming back.

"Where is Westall?" I asked.

"Oh, he turned back," he replied; "there's nothing to do, unless go up the range on foot; but Westall said he would go on a little further."

We waited, and as we did there came to our ears an awful cry of agony for help, that simultaneously we both shouted in reply, and pushed forward as fast as the sand would permit. It must have been a terrible cry to have reached us, for seemed to traverse nearly a mile before we came upon Westall—up to his waist in sand, and his horse, from which he had thrown himself over the saddle, in the same. Which bore the most agonised expression, man or horse, it was impossible to say.

The horse was incapable of movement; but Westall could till move his arms. They were in a dry quicksand, and the sand was burning hot. James seemed paralysed; but I, who heard of such things, jumped off, calling him to do the same, and commenced frantically to unbuckle my reins and slip my stirrup-leathers, in response to the despairing yells for help that came to us.

While still engaged in this task, the horse, with a scream of pain, disappeared. As fast as we could, we worked; then, approaching as closely as we dared, we threw the substitute for a rope to the wretched man, now nearly up to the I armpits.

It was too short. We threw ourselves flat, and felt the uneasy mass of burning sand immediately in front, and thought we could trust it. James got on his knees and tried another cast. This time u was successful. Westall caught the stirrup-iron at the end, and I, too, rose to seize the leather, when, as if determined not to lose its prey, the sand began to heave and work, consequent on the submergence of the horse, and Westall, who must have been mercifully dead with the sudden increased pressure, disappeared.

"Save yourself!" shrieked James; "it's got us."

If by magic, the sand beneath became tremulous and yielding. I was nearest the range, and throwing myself flat once more, commenced to roll toward it. James instinctively started to his feet to run, and was caught, as were the horses.

I reached the range, clutched the burning rock, and dragged myself on it. When I dared look, I wonder I did not go mad. James was digging his hands in the hot sand, striving to drag himself out; and the horses!—one stood quiet, trembling only, while the sweat rained down; the other strove and struggled, and whinnied piteously. And I had to sit there and watch it all, utterly helpless. The only thing I could do was to throw myself in and perish with them. But such a death! I turned face down, and covered my eyes, and tried to stop my ears.

Once I looked. The devilish sand seemed alive with fury or joy, shaking and quaking, and boiling almost. James must have been dead, for he was lying forward with his head on his arms. One of the horses was the same, the other was quiet; and I turned away.

When I looked again, everything had disappeared, only the glowing sand was still full of motion. I was alone.

When at last I regained some mastery over myself, the sun was sinking low. The treacherous, horrible sand was quiescent; but determined to wait until far into the night before seeking a passage; meanwhile, I commenced to make along the rocks to the spot where we struck the range, as being the safest place to attempt it. But I reflected—the hellish thing having been once set in motion, it may be days before it settles down again; meanwhile, Dan will either come to look for us, and perish too, or return to the old camp at the salt lake, and leave me to perish by a more lingering death than that my companions met with.

As this comforting thought struck me, I came upon what seemed a confirmation of my fears. Three skeletons lay on the rocks, and further off I saw the remains of two more natives who had been entrapped like I had. Perhaps a whole tribe had gone under. Surely if they could find no means of escape, what chance had I?

It was more than once I approached the edge of the rocks, meaning to dare the fatal passage; but my courage failed me. The range, as I said, was bare, smooth rock, and I had weighty object with which to test the condition of the sand. At last I thought of the dead bodies, and although the task was sufficiently repulsive, I managed to accomplish it, and dragged them to the edge of the range, and pushed them out on to the quicksand. They lay there unengulfed. Apparently, the way was open.

Still, I was too frightened to trust myself on my feet, and rolled the whole way across to the firm ground. When I got up and looked back, the two bodies had disappeared. I waited for no more, but hurried back to camp.

I explained what had happened to the boy, and he at once became terribly alarmed, and showed the greatest anxiety to leave such a dangerous neighbourhood. We reached the settled country after some days—that is to say, I reached it, for Dan disappeared before then. It will easily be understood that his disappearance was necessary, as if left to tell some garbled tale he might have been the cause of suspicion that I had murdered my mates; our experience having been too startling for ordinary belief.

For non-Australians, the "jackasses" in the last paragraph are kookaburras, birds popularly nicknamed "laughing jackasses" at the time.

TWO men—two swagmen—met on an outback road, about an hour or two before sundown, and they squatted down for a smoke, and exchanged confidences.

"You'll strike Hungry Hartford's place about sundown, and I don't envy you. You'll get tucker, such as it is. A pint of weevily flour; it it's beef, you'll get the New England tongue, or it it's mutton, you'll get a scraggy piece of the neck and shoulder. As for the tea, it's all stalks, and as for the sugar it's black with age, and no sweetness in it."

"There should be a law," said No. 2, "compelling squatters to furnish decent rations. How can they expect a man to travel on such cag-mag?"

"I quite agree with you," said No 1. "They talk about their Early Closing Acts and their Sunday closing, and their this, that, and the other, but how about our rights and privileges? Blow me, if they're regarded in the least. We should have a swagman's member in Parliament."

"We should," said No. 2, "and if I could make a rise I'd go in on that ticket; I can talk as well as most of them."

"You can, Bill, a deuced sight better than most. How would it be to get up a subscription through all the travelling fraternity, to subscribe to a fund to put you in Parliament."

"It might be done, Jim; but they'd all fight over who would be treasurer. Well, so long. I suppose I must put in an appearance at Hungry Hartford's, or I shall get no tucker, bad as it is;" and No 2 resumed his swag and his way.

While discussing Hungry Hartford's rations that night the conversation he had just had kept running in his head. Why should he not put up for Parliament? He was as well educated as the general run of members; he could talk fluently, and had any amount of assurance. On reflection, he seemed to possess the usual qualifications, and, thinking over it, he got into his rough bunk, and fell asleep.

"MR. SPEAKER, standing as I do here on the floor of the

Parliament House of a great and coming nation, with the dust of

honest tramping on my boots, and the taste of bad rations in my

mouth."

These were the words that awoke him, and he found himself in the gallery of a large hall, looking down upon a gathering of legislators, one of whom was then addressing the Speaker. The figure of the speaking member was arrayed in the rough dress of a swagman, and at his feet lay his rolled blanket; and then he noticed that there were others amongst the assemblage who were dressed as swagmen and had their swags lying at their feet; but somehow, to his practised eye, these men did not look quite the correct style of thing. But, strangest thing of all, the man who was addressing the House, was himself. It is not often that a man is privileged to look upon himself in the flesh, and this was Bill Denner's strange experience.

His double was still speaking:

"I have the honor to represent a large and important section of the community, and in the same of the community of swagmen, of sundowners, as they are more poetically called, I claim that this bill, authorising a swagmen, when his billy or waterbag leaks, to obtain a new one from any station owner, should be brought forward at once. That it will pass, considering the intellectual status of the legislators of New South Wales, I have not the slightest doubt. Which of you—I ask the question with confidence in tho answer—would like to be stranded on the burning plains of the West, with a leaky billy and a waterbag with holes in it? Not one of you. Then why should these poor men have to suffer the dangers and disadvantages of such a misfortune. I leave the matter in the hands of the House, satisfied that the feelings of humanity, of justice, and of common altruism, will lead to this most necessary bill being at once passed."

Now, during the latter part of this speech Bill Denner had felt a strange kind of compulsory feeling creeping over him, insisting on him going down and interviewing his double. He rose from his seat and passed down the stains, seemingly by a mere act of volition. His feet carried him round, whether he would or no, to a front entrance, and there he came face to face with the other Bill Denner.

The attendants and others took no notice of him, seemingly did not see him, but his counterpart recognised him at once, and seized him eagerly by the hand.

"So you hare come at last," he said. "I'm very glad; I'm getting sick of the job; but I've put you in a good place, old man. Lord, what fun it has been! Mind you keep up to the mark." He took Denner's arm as he spoke and led him outside.

"But," protested Denner, "don't it seem strange for people to see two men be much alike together?"

"Lord, man, no one can see you as long as I have your body. Come along to a quiet place and I'll tell you all I've done."

The pair went on till they came to a small pub with an empty back room, and they went in and sat down. The double rang the bell.

"Bring two long beers," he said.

"Two?" said the girl, inquiringly.

"Yes, two. I expect a friend here shortly." The girl brought them in. Then, when she had left the room, Denner poured one down his dry and dusty throat.

"Now fire away," he said.

"Well, you remember when you went to sleep in the traveller's hut at Hungry Hartford's station. In point of fact you went off in a trance, and I—"

"Was I buried?"

"Yes, you were buried right enough, and Hartford was very mad at your choosing his station to die on. So they didn't bury you deep, and I soon had you out, and thought I'd have a bit of fun in your body. As soon as I appropriated your body I found out what you had been thinking about, and the idea suited me down to the ground. Now, thinks I, if anybody can engineer this job I can."

"But who are you?" demanded Denner.

"Oh, one of the fourth spirits, who are allowed to play these pranks. I went into the thing con amore, and I very soon was returned as a member, ostensibly for Mudville, but in reality in the swagman interest. You'd be astonished how the idea took. The member of the Swagman's Interest became at once an important member of the House. I have got three bills through already—the Improvement of Rations Bill, the Disinfecting Travellers' Huts Bill, and the 4 o'clock Tea Bill, by which any traveller arriving at a station can demand afternoon tea if he comes early. The idea got so popular that other members commenced to copy the notion, and also my dress; but they can't do the real thing, as perhaps you have noticed. Anyway, they commenced to bring dogs in the House to make the thing realistic, but such a series of free fights followed that it had to be stopped. The dogs would fight, and then the members they belonged to would accuse one another of kicking their dogs, and more fights would follow. Now, I have put things in good working order for you, go ahead in the path I have marked out for you, only don't make a mess of things after I have had so much trouble in putting them right. Now, I'll tell you how you stand. I've saved a bit of money for you, living as I have done, and I can't take it with me, for I am going back to the spirit world, here it is, £75; take it, and pocket it. Now, mind your follow my advice, and stick to the path I have chalked out. Good-bye, there is somebody calling me, I must go. Your lodgings are at 47 Duchess Street; the rent is paid for this month. Good-bye, take care of yourself, for you are a noted man, and a celebrity in Sydney political circles."

Denner felt a sharp twinge of pain, and then he was sitting in the seat occupied by the stranger, and he was alone. Wondering much, be picked up the swag on the floor, and hoisting it on his shoulder, made a start out into the street to discover 47 Duchess-street.

With the money in his pocket, he had the sense to avoid the pubs, and reached his lodgings in safety. They were clean and tidy, and he was evidently a much respected man there, and was addressed as Mr. Denner, which was an innovation in a swagman's life.

He went to bed early, and next morning read in the paper the brilliant speech made by Denner, M.L.A., the night before, and he found himself styled the democrat of democrats.

Things went smoothly at first, for he stuck to the advice of his mysterious friend, and kept to the beaten path that was laid out for him. He received a deputation of swagmen, who, after presenting him with a testimonial for the benefits he had already obtained for them, requested him to introduce a bill to enable all swagmen to be provided with bicycles, at the expense of the State.

Gradually, as time went by, there crept over him a fatal longing for a tall hat. He resisted the fascination as long as possible, but at last it grew too strong, and he yielded to it. He bought a tall hat, and in the solitude of his room he tried it on. He looked in the glass, and shuddered. It was impossible to wear a top hat with his swagman's shirt and moleskins; no, he must have his hair and beard cut, and invest in full political rig; a frock coat must follow, or the old dress be retained—a compromise was impossible.

Fearing much, but led on by a fatal impulse, he indulged in the change of garments. As he stood before the glass, and noted his different appearance he seemed to hear an echo of mocking laughter in the room.

When he entered the House that night he was met with covert sneers and weak jokes. His speech fell flat, and as he looked upward he met the reproaching gaze of many swagmen in the gallery.

Next morning the papers alluded to him as the reformed swagman or the transfigured democrat. From thenceforth his influence departed. Representative swagmen called on him to resign, and, as a final effort, he travelled down to the backblocks, there to address a meeting of his constituents. There was a large gathering, and a very indignant one, and he quailed as he saw a vista of swagmen of all ages and sizes, all angry, all indignant, and all crowding up to the balcony with missiles in their hands.

"Call yourself a democratic swagman," they roared, "and wear a top hat and frock coat! Ugh!"

And then a shower of missiles of all sorts were rained on him, and he felt himself struck on the head. He started, and the whole scene disappeared from view.

HE was lying in the travellers' hut at Hungry Hartford's, and

the grey dawn was slowly stealing through the chinks in the

slabs.

"What a dream ."' he muttered. "No, I don't think I'll try to get into Parliament as the swagmen's member. Doesn't suit me."

He rolled up his swag and marched off along the road just as the jackasses were beginning their morning song.

I HAD long been interested in hypnotism, and as I fondly imagined, understood the science as well as a man without practical experience could. That was the trouble. In theory I was perfect, but as yet my practical experience, was limited to two attempts—both, I am bound to admit, failures. At this juncture my wife came to my rescue. She is of a mild and gentle disposition, and takes great interest in my scientific researches; but it never occurred to me that she could act as a subject for my experiments until after a conversation we held one day on the matter.

'There is a singular development in connection with hypnotism just recorded in this journal,' I said.

'What is it, Willy?' she asked.

'That if the person hypnotised thinks of some particular character, whether of history or fiction, whom he or she admires, they assume that character under the hypnotic influence. Further, that the hypnotiser can imbue the patient with the notion that he or she is some historical personage. But that,' I added, 'was known before. The first part of the paragraph is, however, novel.'

We talked over it for some time, and presently my dear wife said shyly—'Willy, suppose you try and hypnotise me. I will think of some favorite character. But mind, dear, you will not make me do anything foolish, will you?'

I assured her that I would not, and we commenced the experiment. To my astonishment it was a complete success.

'Now, Lucy,' I said, 'tell me who you are?'

The next moment I got a terrible blow in the face that nearly knocked me down. 'The most infectious pestilence upon thee!' said my wife. 'Hence, horrible villain! or I'll spurn thine eyes like balls before me; I'll unhair thy head!'

And she proceeded to do so by hauling me about by my beard, for I had no hair to speak of.

On she went: 'Thou shalt be whipped with wire and stewed in brine, smarting in lingering pickle!'

Good heavens! My gentle Lucy, who shrieked at a mouse, was transformed into Shakespeare's Cleopatra. As well as I could under the difficult I circumstances I removed the influence, but my wife had no sooner caught sight of me than she fell back on the sofa in a faint, with a cry of alarm.

No wonder. The first blow had caused a rush of blood to my nose, and the second one had swelled my eye, whilst being hauled about by the beard had left me slightly dishevelled. I must have been a pitiable sight indeed.

'Oh, what has happened?' she moaned,

'I'll tell you directly,' I said, behind my bloodsoaked handkerchief. 'I must go and stop this bleeding; it's only my nose.'

I went to my bedroom, and when the bleeding had somewhat stopped I told her what had happened.

'Is Cleopatra, as portrayed by Shakespeare, a favorite character of yours?' I asked.

My wife rather shamefacedly confessed that she did admire the domineering character of Cleopatra.

Here was a surprise. I should have thought that my wife would have admired one of the mild heroines of Jane Austen, but this disclosure took my breath away. It only shows how you can be married for years and yet not know one another's character. However, we agreed to drop the experiments at present, but the thing had given me an idea.

We were not too well off, but I had expectations from an old aunt. So too unfortunately had another nephew, an idle scapegrace of a fellow, who would squander all she left him in a year or two. But, most unjustly, my respected aunt had rather a weakness for him, and naturally I felt very serious about my inheritance at times. Why shouldn't I make sure, invite my worthy relative to stay with me, persuade her to let me hypnotise her, and while in that condition make her promise to make her will in my favor, to the exclusion of the other unworthy nephew?

I mentioned the idea to my wife, and she and I arranged the details of our plot. I found, on consulting all my authorities on hypnotism, that a promise given under the hypnotic influence remained binding until the patient was relieved of it by the hypnotiser. Instances were cited of confirmed drunkards promising to refrain from drink, and adhering to the promise; and of course I thought all these cases true. This was satisfactory. If I could only hypnotise the old lady my future was safe.

My aunt always enjoyed a visit to us. She was fond of her meals, and my wife was a capital cook; so she came readily on my invitation. I must admit that her visits were not an unalloyed blessing, for she took every advantage of her position, and was as exacting in her demands as one woman could well be. However, when there is money at stake, one puts up with that sort of thing, although my wife used to have a good cry every night in the seclusion of our room. Indeed, I felt at times half inclined to hypnotise my wife, and let my aunt have a little experience of her in the character of Cleopatra.

However, my way was partly cleared for me, for my aunt was deeply interested in the subject of hypnotism, and therefore I began to talk about it, and the successful (God forgive me) experiments I had made. We had a series of mock hypnotisms, and my wife acted her part well, for I was careful not to make the hypnotism a realism.

The old lady rose to the bait, and expressed a wish to be hypnotised. It was a nervous moment. What if I failed?

Fortunately, the old lady, my respected aunt, was a willing subject, and it was not long before I got her off into a real hypnotic trance; and I proceeded to question her on the subject of her will. She answered readily enough, and I found out that beyond a poor £500, the whole of her property was left unreservedly to her favorite nephew James. I told her that must be altered at once, and the name of William inserted instead of James. I hesitated whether I should allow James anything, but generosity prevailed, and I let him stand in for the £500.

I restored my respected aunt to her senses, and she expressed herself as much pleased at the success of the process. She stayed with us a little longer, and I repeated the mesmeric passes, and thoroughly fixed the will subject on her mind. We parted on the most affectionate terms, far more affectionate than ever we had been before.

A fortnight passed, and one day I received simultaneously a letter and a telegram. I opened the telegram. My dear aunt had suddenly expired in a fit of apoplexy. Surely we had not overfed the dear creature? The letter was from her, written the night before her sudden and lamented death. In it she upbraided me in a furious manner; said that I had made her a laughing stock and a show. She discarded me for ever, and I need not expect one penny of her money.

My wife and I gazed at each other in dismay. What on earth had occurred?

This is what happened, as I found out afterwards. That villain James heard somehow, through one of my servants I suppose, about the hypnotic experiments going on, and he laid a deep and artful scheme. There was at this time a mountebank performing in the town, who had a lot of miserable hired subjects whom he used to make perform all sorts of ludicrous and disgusting tricks under the pretended mesmeric influence.

To this entertainment James insisted on escorting my aunt She asked to be taken out after a short time had elapsed, and appeared very pre-occupied and silent.

'James!' she said, when they got home, 'I have been staying with William, and while there he hypnotised me. Do you think he made a show of me, like that man did with his patients?'

'Not a doubt about it,' said the villain.

'What! Made me eat tallow candles and stick pins in myself?'

'Yes.' In fact, I know, he did from one of the servants.'

My aunt nearly had a fit. Then she dismissed James, and wrote two letters—one to me, and one to her lawyers.

The next morning James turned up again, determined to drive the nail home, and told her a list of my atrocities that he pretended he had heard. He had just described how I called up the servants and made her dance a hornpipe before them, when suddenly she choked, turned red, and went off in a fit of apoplexy from sheer rage.

James had overdone it.

When the lawyer arrived she was dead. I shall never forget how James and I glared at one another while the lawyer opened the will. The hypnotic suggestion had held good, and James had cut his own throat. William got everything but the £500 which James got.

'I congratulate you, Mr. William,' said the lawyer. 'Your aunt only inserted your name about a fortnight ago.'

I have given up hypnotic experiments. I am quite satisfied about the matter.

THE river had long ceased running, the water holes were few and far between, and the cattle had worn long, dusty pads in and out to their feeding grounds, gradually working further and further up the ranges that bounded the valley through which the river ran.

The drought showed no signs of breaking up. True, thunderstorms gathered, and grew black and threatening; but in the end they melted away in idle bluster; a few heavy drops of rain, a flash or two of lightning, some heavy peels of thunder, and then a storm of drifting, blinding dust. All day the whirlwinds stalked over the burnt country, tall, revolving black columns; and, all night the stars shone out of a cloudless sky, bright, clear, and pitiless.

No moisture was in the air in the early morning, no dew spangled the tussocks of white, dry grass, that here and there survived—all was desolate under the cruel sun that lorded it all the day. The station horses were too poor to work, even if there had been anything to do, but sit down and wait for the rain, which, seemed as though it would never visit that portion of the earth again.

It was on an out-station in North Queensland that two men were doomed to keep each other company during this dreary period of heat and enforced idleness. The elder man managed to pass the time fairly well, plaiting green-hide into whips, bridles, and hobbles; the younger, whose tastes did not lie that way, after one or two ineffectual attempts to learn the knack of it, gave it up, and read the two or three tattered novels on the place for the tenth or twelfth time.

'Bob,' he said one morning, 'I shall assuredly go mad if this lasts much longer. What do you say if we take a trip up to the head of the river?'

'What for?' asked Bob.

'Just to see where it comes from. You remember when we followed it up to a gorge twelve months ago, and were blocked by a waterhole. That hole must be pretty dry. now, and we can get up higher.'

'What's the good,' muttered Bob, tugging at his plaits; 'only knocking horses about for nothing—and they're as fat as fools now; aren't they?' he added sarcastically.

'Oh! if we go steady, it wont hurt them. I'm dead sick of staying here doing nothing; we might find something interesting.'

'Pooh! This river just heads from the coast range just like all the others. There can't be anything new about it.'

'I don't know. That range seemed very curious to me, and I've had a hankering to get through that gorge ever since we were up there. Will you come?'

'Oh! I suppose so. We may as well do something to earn our rations. You can run some horses up from the four-mile bend this afternoon. I saw their tracks there the other day.'

The next morning the two men started, taking a packhorse with them, as they anticipated being away at least three days.

THREE days passed, and three hungry dogs at the out-station

looked vainly for their return, and consulted together as to the

feasibility of going out calf-killing. Three more passed, and the

lean and famished dogs held a council of war, but could decide

nothing, until one of them hit on the happy thought of shifting

their quarters over to the head station, eighteen miles away.

In consequence the residents there were astonished by the advent of three famished spectres, who were recognised as three out of the four dogs belonging to the out-station; the fourth had gone with the two men. Something was wrong evidently, and the manager and another man started over at once, well-armed, thinking the blacks might have raided the place.

It was dark when they arrived; but the slab hut, with its grey roof of bark, stood there, silent and lifeless, with no sign of any tragedy having taken place. There was a half-moon, and the night was bright and clear. They dismounted, and, knowing the secret of the clumsy latch, opened the door and entered. The manager struck a match, and surveyed the empty interior. As if the light had aroused something, a long, dismal, melancholy howl arose from the river, about a hundred yards away. Again and again it sounded, and the two stared at each other, until the match burned the superintendent's fingers, and he dropped it hastily.

'Surely that wasn't a dingo?' he asked. 'Didn't sound like one; but what else was it?'

'Blessed if I know. 'Twasn't a man, anyhow. Try if you can find the slush lamp; we'll make up a fire and boil our quarts.'

The lamp was trimmed, and a fire lighted, the quarts were put on, and the horses hobbled out to pick up such dry stuff as was left. The deserted hut had a weird, uncanny appearance, and dark shadows seemed to hide in the corners, dimly illuminated by the flickering flame.

'I wish it was morning; we can do nothing till then,' said Greenwood, the manager.

Of a sudden the cry arose again; but now it came swiftly towards the house, and with it came a sound like the beat of heavy wings. Both men had faced death in their lives, and were plucky enough; but now they were fairly stricken still with fright. And the cry came near, and circled round the hut, and the beat or the heavy wings accompanied it; and the wings seemed to flap against the walls, as though the wailing thing was trying to find entrance to the light.

'Come on, Dick!' cried Greenwood, in desperation; and flinging open the door, he rushed out, followed by his companion.

In the still, calm air the trees stood erect and motionless—not a bough or leaf stirred. The vertical moon searched every spot; but all around there was no sign of anything. The beat of the huge wings was silent; but a sound came from a distant belt of scrub like some strange being sobbing in great distress. The horses were standing still, sulking over the absence of feed, and did not appear to have been startled.

'We must tie them up to-night,' said Dick, breaking the silence, 'or they'll be miles away in the morning.'

'What on earth was that thing?' answered Greenwood, unheeding, and straining his senses to catch any sound or murmur; but all was quiet.

'Yes; tie them up, Dick,' said the manager, recovering himself. 'Tie them up in the verandah. They'll be company for us.'

He laughed mirthlessly, and after the horses had been secured they turned into the hut, and commenced their interrupted meal.

The night passed without their being disturbed, and by the first dawn the men were mounted, and glad to lose sight of the hut, where they had had such a dreary experience. They managed to pick up the tracks of the two men, and follow them up the river, until they got beyond the tracks of the horses' feeding grounds; then it was pretty easy work, for it was soon evident that the men were following the river for some purpose or other.

It was late in the afternoon when they reached a narrow gorge in the range, through which the river descended, and here their progress was blocked by a long and, apparently, deep waterhole, with sheer rocks rising on each side of it; but, strange to say, although they tracked the two right up to the water's edge, there were no return tracks.

Greenwood gazed at the water in perplexity. The sides were steep and inaccessible. Unless they had gone over the range, they could not have got round the hole. But then there was no turning back; the tracks went straight into the water, and were lost.

'They must have swum their horses across; but what for?'

It was getting late and their horses had had no feed the night before, so it was impossible to do anything more that night. Fortunately, Dick had noticed a patch of grass at the entrance of the gorge, and they went back there, and turned their hungry horses out and camped.

All night the silence was unbroken. No weird cries disturbed their restless naps, and no phantoms came to their camp, beating the air with invisible wings.

In the morning Greenwood determined to leave their horses where they were, there being no sign of blacks about, and try and get over the side of the gorge on foot. This they did, and in due course arrived at a point from which they could see the end of the water-hole, and some of the country beyond. But to theirs astonishment the end was impassable, blocked up by huge boulders and fallen rocks, a complete barricade.

'Whoever went in that hole never came out at the end,' said Dick.'

Greenwood examined the place carefully.

'It seems to me that those rocks have fallen recently. There's been a landslip lately.'

'Perhaps since they went through, and they can't get back,' suggested Dick. 'They would have managed it on foot; more likely the landslip caught them and their horses. Let's get as close as we can.'

They clambered on until they were right over the ruin below, and in sight of the country beyond the gorge.

A terrible looking place it was too, a barren, rocky basin, seemingly without vegetation of any sort. The course of the river could still be traced, showing a little water at intervals. But the singular thing about the landscape was that it was dotted over, with isolated, fantastic-looking rocks that took little imagination to conjure into eccentric and devilish forms, most of them like huge bats with extended wings.

'Blow me!' said Dick, 'but I never see'd rocks like that before.'

'Nor I either. Let's see if we can get down and find any tracks.'

After some trouble they reached the lower ground, and stood at the upper end of the water hole that blocked the gorge, above the huge mass of debris and rocks that formed an impassable barricade. Just above this Greenwood drew his companion's attention to a spring issuing from the scarred face of the cliff.

'I have it,' he said, after a little consideration. 'That hole was nearly dry when they came here, and they rode through it easily, then came this landslip, and that spring broke out and filled the hole up again.'

'We ought to find them up here then?'

'I'm afraid something has happened; they could have got back the way we came.'

'Dashed queer-looking place,' said Dick, looking round. Now that they were down in the basin the outlook was more weird than from up above. The strange isolated rocks rose up in front of them like an army of grotesque forms suddenly turned into stone. Greenwood went over to examine one of them. His footsteps made a hollow ring rise from the bare, flat rock, as though it was cavernous. He called Dick over.

'These things are easily accounted for,' he said. 'There's a soft stratum in this rock, and in heavy floods this flat we are on is all submerged, and that stratum has been washed away, and the hard rock left, standing. Look! there are one or two where the soft stuff has been washed clean away, and the rock has tumbled over.'

He pointed out the objects he was speaking of, but Dick, after looking at them, suddenly exclaimed, 'What's that there, Mr. Greenwood? There's something lying there as isn't a rock.'

They hastened over to it, and found to their dismay the clean-picked skeleton of a horse.

'Twasn't the crows did that, or dingoes either,' said Dick after a long pause. 'Besides there's no sign of them about.'

Both men stood silent and listened, but the stillness was unbroken by even the common sounds of the bush.

'Not a scrap of anything left but the bones,' remarked Greenwood, after examining the remains. 'Do you think it is one of theirs?'

Dick looked puzzled. Then he stooped down and examined one of the feet.

'It's old Ranger,' he said. 'See this crack in his hoof. When I was over a fortnight ago I put a shoe on for Bob to stop Ranger going lame. This is the shoe.'

'It's no good looking for tracks on this hard rock, but we must have a search round, anyhow. Don't get out of hearing, but cooee to me occasionally, and I'll answer. Fire a shot if you want me.'

The men parted and soon lost sight of each other amongst the standing pinnacles, but kept touch of each other's whereabouts by calling out at intervals. Presently Greenwood heard a shot, and going in the direction found Dick standing over the skeleton of a dog. Like the other the bones were picked clean and bare.

'Wonder how many horses they had with them?' said Dick.

'Wonder what sort of thing it is that has done this. It's not been done by anything in the bush that we know of, and I don't think there's much we don't know of.'

'By jingo! suppose they tackle our horses while we are away,' said Dick, and the thought made both men start.

'We must find something of Bob and young Daly before we leave,' returned Greenwood firmly, 'or come back to-morrow and keep on until we do. Whatever's left of them must be about here. We'll follow the river for a bit; it's early in the day yet.'

They followed the river up for a couple of miles, and found it only a channel worn in the solid rock, which spread on either side. No soil, no trees, nothing but the strange pinnacles all around them. They saw the ranges closing in ahead, and turned back without having found any clue.

'I have often wondered why this river came down so quickly,' said Greenwood. 'The water would accumulate in this barren, rocky basin and burst through the gorge with a rush?'

'By God! there's Bob,' suddenly interrupted Dick, running forward and calling Greenwood followed him, and found him wondering and perplexed.

'I'll swear I saw him as plain as I can see you, and he seemed to dodge behind one of these rocks, and now he ain't here.'

'It's strange he didn't answer you and come to us.'

'Strange. The old fellow must have got a touch of the sun and gone dotty. I've heard that they keep away when they are like that.'

'At any rate we must get on. If you saw him he must have seen and heard you.'

'If,' muttered Dick, aggrieved. 'I tell you, Mr. Greenwood, I did see him. Bob! Bob Blackburn!' he shouted.

Every echo in the ranges shouted back, 'Bob! Bob Blackburn!' but the cries were only echoes, and the two started again.

'There he is!' exclaimed Greenwood. 'You were right, Dick. Blackburn, here we are!'

He had gone again. They looked round every pinnacle and rock, but he was not in hiding anywhere.

Astonished and somewhat uneasy, the two resumed their way, and all the way to the gorge the mysterious figure appeared ahead, to first one, then the other, of them, and when they reached the gorge both saw it standing on the top of the tumbled rocks and boulders, and there it vanished.

The two looked at each other, and whispered awe-struck, 'You saw it too.'

Their nerves were getting a bit unhinged, but after a little they rallied.

'We must search these rocks,' said Greenwood. 'You saw where that thing disappeared?'

'Yes, what was it? It was Bob, and it wasn't Bob. However, we'll find out.'

Talking pretty loudly to keep one another's courage up, the two men commenced to climb the mass of fallen boulders to reach the place where they had seen the figure standing.

At times a boulder slipped and rolled down with a rumbling sound, and it was after one of these mishaps and some bad language from Dick, who had slipped, that they heard a cry, a voice seemingly calling for help. It seemed to float all round them; they could not locate it.

'It was a human voice, at any rate,' said Greenwood, and he shouted loudly in answer.

Again came the cry, but now they were on the watch, and were able to place it.

'It comes from underneath,' said Dick. 'One of 'em is buried alive.'

They were now close to the spot where the wraith had been seen, and a little search soon showed a rift, opening into a cavity under their feet. Greenwood stooped down and shouted:

'Any one there?'

His voice rumbled round the opening, which was apparently of some size, and an answer came back:

'Yes; Daly!'

It seemed some distance below, and Greenwood called out to know if it were safe to drop.

'I'm afraid not,' returned the imprisoned man. 'I'll crawl underneath, and you can judge.'

'What's the matter?'

'My leg's hurt; we got buried by a fall of rocks; but one big one has fallen across and saved me.'

'Where's Bob?' cried out Dick.

'He was killed, I hope. But something came and took him out. But I will tell you all. First get me out, get me out of this.'

After a time the entombed man stood beneath them, and by means of their belts and a handkerchief they managed to ascertain that there was nearly twelve feet of a drop.

'You're the strongest man, and I am the lightest,' said Dick; 'I'll drop down—you can lower me as far as you can.'

Greenwood lay down, and Dick lowered himself down and hung on by the edge of the hole; then Greenwood took his wrists and lowered him as far as he could and Dick reached the bottom safely.

'How have you lived all this time?' he asked.

'The pack-horse was killed too, and I managed to get the bags off, and there's water here.'

'How do you propose to get out?' shouted Greenwood, from the top.

'Hanged if I know. Daly can only stand on one leg, and he's mighty shaky. Could you cut some saplings, and—'

'Saplings!' retorted Greenwood.' 'You know there's nothing here but rocks.

'Pile some rocks up,' said the wounded man. 'I commenced to do it, but had to give up.'

'That's the only way, unless you wait here another night.'

'No!' called out Daly, in a voice of terror, 'it's at night if comes. Not another night.'

'Go ahead, Dick,' shouted Greenwood. 'I'll collect some on top as well, and drop them down. Stand from under when I sing out.'

The two men worked hard, for the afternoon was now wearing on, and at last had a heap high enough to enable Dick to assist Daly to crawl to the top, and from there Greenwood was able to reach down and help him, and they got him out. He was worn and haggard from pain and misery, but they forbore to ask him any questions, only Greenwood descended into the hole and examined it.

A great slab of the cliff seemed to have fallen forward, and got chocked in a leaning position. The rocks and rubble had rolled off this and blocked the sides. Daly called out to him to look at the lowest end behind the stones, and he would find the pack bags, tomahawk, and surcingle. Greenwood struck some matches, and by their aid found a sort of barricade of stones erected, and behind the articles specified. He handed them up, and followed himself.

'What was that barricade for?' he asked Daly.

'To hide from the thing that comes at night. It took away Bob and the horses.'

They asked no more, but set to work to help the hurt man away. It was a hard task, but, thanks to the moon, they succeeded in getting him over the range, and found the camp as they had left it. The horses had not strayed away, and, as Greenwood said, they were luckier than they deserved to be.

The next morning; after a sound sleep, Daly felt somewhat recovered and told his story.

'WHEN we came to the waterhole in the gorge, we found it quite

shallow, not over our horses' knees, so we rode through it,

meaning to camp on the top side of the gorge. When we got in

sight of the open country we saw that it was all flat rock, and

no place to camp, so we pulled up and were talking of coming back

here, to this place, which he had noticed, when there was a

tremendous crash, and the cliff seemed to fall in on us. We were

knocked down by the stones, for the big rock did not touch us,

but in fact saved my life. I believe they were all killed at

once, Bob, the horses, and the dog. I was bruised, but the worst

blow I got was this one on my ankle. As I lay there, half stunned

and stupid, I heard the rocks raining down on the huge slab that

protected me, until at last it grew darker, and I knew that I was

completely shut in, I got up, and found that I could only stand

on one leg. I limped about, and at last got underneath the

opening, and wondered if I could get out. The moon was not very

strong, then, so I had to wait till morning, at daylight I

commenced to look about, and saw poor old Bob and the horses and

dog all lying in the dim light, quite still; just where they had

fallen before the big slab came down and saved them from being

crushed. Then I began to collect stones to make a stand to

clamber out through the hole, but I hurt my foot trying to stand

on it, and had to give over. I took the bags off the pack-horse,

and that night the thing came.

'I first heard a cry, far away, come nearer and nearer... It was not a human cry, but like nothing I have heard before. It came close, I heard a noise like the beating of great wings, and then something commenced to clamber up the rocks outside, and there was a noise like sobbing; then the hole was darkened; and presently I heard something rustling and crawling about the place inside. I crouched in the leaning corner as far as I could, and then I heard the noise of something being dragged, along the rock, then the light came back through the hole, and I heard the howling again. This time it was answered; other things came up howling and crying, and once more the hole was darkened, and the dragging sound recommenced. Sometimes the thing crawling about seemed to come quite close to me, but it never touched me. At last the light of the stars was visible once more, and with great crying and the flapping of many wings the things departed; but for a long time I heard the wailing noise they made.

'In the morning I saw to my horror that Bob and the horses and dog had been taken away. I tried all I knew to get out, but only made my ankle worse, and I felt like blowing my brains out, for I saw no hope of anyone coming to my assistance. But I thought I'd stick to life as long as I could, for surely I could manage to make a hole somehow amongst the loose stones. So I gathered all the boulders I could crawl with and barricaded the low end of the cavern, for I was sure the horrid things would come back again. They did; every night there has been hooting and calling, and something rustling and searching about the cave. Whatever it was they could not get in altogether; but I think the awful things had a trunk that they thrust in, and it was not long enough to reach me. How I lived through it I don't know. It has put its mark on me for my life.'

After some further questions, Greenwood told Daly of the experiences he and Dick had been through, the winged thing that came to the hut, which was evidently one of the creatures that had been at the cave; how the ghostly appearance of poor Bob Blackburn led them to the opening, but for which probably he would not have been found.

'Then,' finished Greenwood grimly, 'I'm going to find out what these things are.'

'Take me home first,' cried Daly; 'I can stand no more.'

'Yes, we must go home first; there are a few things I want to prepare. Dick, you'll see the matter out?'

'Rather,' returned Dick, with force and brevity.

By easy stages, they took Daly to the head station, and then Greenwood made his preparations for a start.

The story, of course, had been told, and talked of, and the evening before Dick and he and a third volunteer were going to start, his black boy came to him with a tale he had heard from an old gin. No blacks went up that river now, though once, right, at the head of it, a large tribe used to camp; for there was a big lagoon there with fish and ducks in plenty.

One year it was fearfully dry, and some strange things came to the lagoon, flying things that killed the blacks, and sucked all their flesh away. The fish died in the lagoon, for the water turned black and stinking, the trees around it died; and what natives were left fled for their lives. Then the story went amongst the blacks that these awful things only came out when there had been no rain for a long, long time, and only when the rain came did they leave for the unknown places they came from. The description given of these creatures by the old gin was vague; but it agreed with what Greenwood had guessed.

THE next morning they started. After some trouble they found a

way up the range, by which they could take their horses, and

following the range round they finally arrived at the river

again, having thus gone round one side of the rocky basin. Just

beyond should lie the lagoon, if there was any truth in the

blacks' yarn. Expectantly, they looked over the crest, of the

range, and there, sure enough, was a dismal black lagoon,

surrounded by skeleton trees, in the midst of a barren, desolate

tract of land. No sign of life was visible.

They descended but could not approach the water, as the ground became marshy and boggy. The whole country seemed under a blight and a curse: Once Greenwood thought he saw a dark, undulating body rise above the gloomy surface, but he was never sure. His plans were formed, he had only come to make certain of the lagoon's existence. They turned their horses' heads back, and returned to their old camp at the end of the first gorge.

The next day they, were busy at work at the cave where Daly had been entombed. Having finished their work there, they repaired to the side opposite to where the hind slip had been, and after some trouble made a rude pathway, by which a lower ledge could be reached. Greenwood had brought a coil of fuse and some dynamite cartridges, intended for timber-splitting. He was going to try its effects on a little trap, he had thought of. The edge of the fallen slab looked very shaky, a charge might start it, and if so it would pin down any animal or thing with its head in the hole.

It was a brilliant moonlight night, now only a few days before full moon, when the watches took their position on the cliff, Greenwood being concealed: on the ledge, where the fuse terminated.

At last, the hooting and the beat of wings was heard; and in the moonlight they saw a huge dark shape come in sight, and drop on its feet at the side of the hole. Still bent on getting its victim, it thrust the long trunk it had into the aperture, and commenced to explore it, its enormous black bulk standing clearly defined, the wings propping at its sides. Dick nearly uttered an exclamation, for there was a stealthy step at his side. But it was only Greenwood, who had lit the fuse and joined them for safety.'

Some anxious minutes passed, then, the horrible thing lifted its head, and gave vent to the howls they had heard before. Greenwood was afraid, that the cartridges might explode while the thing had its head raised, but it plunged it in once more, and, as it did so, the explosion rang out, and the huge slab slipped down, and pinned it there.

The din that arose was awful. From far away came swift approaching hoots in answer to the cries of their desperate and struggling companion. They assembled round him to the number of half-a-dozen or so, and a babel of sound came up.

The men crouched in terror, dreading discovery when there suddenly came a loud crack and a dull grinding noise, followed by an almighty crash. The explosion had started another fall in the opposite cliff, and an avalanche came crashing on the monsters. A cloud of dust arose, thick with waiting cries; then followed another fall.

Out of the dust reek, Greenwood saw some gigantic form emerge, and sail away with a thunderous beating of wings, and then the cloud cleared and settled, but all was quiet down below, only the cliff they were on still seemed to rock with the concussion. The gorge was piled half full of rocks and rubble, but the creatures who had been caught in the fall were buried under tons and tons of rock.

The next day the rain clouds burst in fury, and since then the drought-demons have never been seen.

Only a white-headed man named Daly still tells to everyone who will listen his strange story. He is slightly deranged, and has been ever since that time.

"SAME old fence," said the swagman, as he contemplated an erratic piece of fencing by the side of the road. "That crooked tree still alive that Jim Staines hung himself on. It's quite pleasant to come back from one's wanderings and be welcomed by the old familiar objects such as these."

The swagman pulled out his pipe, and proceeded to fill it with a musing kind or air.

"Nine years since I was in this place, and blest if I think there's any change in it. Bet two to one old Jarmyn is still in the verandah looking out for travellers, and telling everybody of the roaring nights of the old days." He smoked on for a time, then a smile stole over this weather-worn features, and he resumed the swag he had thrown down, and went on his way.

"Darned if I don't do it," he muttered; "I've just enough coin to carry it through."

Maranoo, the township he was approaching, was just about the sleepiest of all the sleepy bush townships of New South Wales. A good-sized pocket handkerchief would have covered it. The one and only street was grass-grown to such a degree that it was generally used as a common. The daring stranger who walked down it during midday roused up disgusted milkers chewing their cud, and woke from pleasant dreams the sleeping horses. But in the opinion of the citizens of Maranoo a halo of glory still stuck to the place which time could not eradicate.

There had once been a gold field in its immediate neighborhood, and the memory of that field was the badge of honor of the Maranoos. True, the field had been of the smallest and poorest, but gold had been got there, and as years passed the nuggets increased in size and weight, and the mad orgies of the diggers were spoken of with bated breath. Nay, by whom started it was never known, but there were rumors of a deep lead, of such wonderful richness that, if once traced, the fortunes of Maranoo and the inhabitants thereof would be made for ever.

The swagman, whose name was Bates, had been on the field during its short-lived existence, and had been personally known to many of the inhabitants, having been one of those who had made a little—a very little—gold.

"Don't suppose they'll know me again, with my hair all white like it is. However, I'll chance it," and revolving these thoughts, he marched on along the road.

Soon the great township of Maranoo hove in sight, the first house, naturally, being a pub. There was old Jarmyn, as he had anticipated, still on the lookout for the diggers to return and rouse the welkin with festivity.

The architecture of the town was poor and simple in the extreme, but it sufficed, for the inhabitants did not put on airs. So long as they could spit in the road from their own doorway they were content.

The swagman pulled up at the old pub known to fame as the Digger's Rest, and throwing his swag on the verandah floor, greeted old Jarmyn with the intelligence that it was blanky hot for the time of year.

Jarmyn, after taking in the astounding fact that the newcomer was a stranger in reality, and not one of the townspeople masquerading as such, got up and proceeded methodically behind the bar, the shelves of which were mostly stocked with dummies.

"I don't mind if I do," said Bates. "P'raps you'll join me," and he ostentatiously drew forth some silver. Jarmyn had no objection, and joined.

"You don't mind a fellow here in the old diggings days of the name of Bates—Tom Bates—do ye?" asked the swagman.

"Bates! Name seems familiar like. A sort of cross-eyed, down-looking chap, was he?"

"Not at all. Eyes as straight as your'n—might have had a black 'un occasionally."

"Bates—Tom Bates. Of course," said the landlord, changing his tack, for even a swagman was a rare and precious being. "Now I mind him. I was thinking of Tom Gulliver. Yes, Bates. Friend of yours?"

"Rather. He and I went to West Australia, together."

"What, that 'ere Coolgardie I've heard tell on? Do anything there?"

"Me and Tom did first-rate at first, but he was allus a-hankering after something he'd left behind here. Weighed on his mind, it did, until he took sick with typhoid."

"Did he die?" said the landlord.

"Not he! Tom Bates die of typhoid—no fear! We got stone-broke, and the stonier we got the more Bates talked of Maranoo, and what there was there he'd left behind."

"What was it?" asked the landlord, filling the traveller's glass again. "Ah! that he never told me. Only he used to say, 'Just you wait, Jim Thomson, until we get back to Maranoo, and we'll just paint the town the bloomiest red ever was. You see, old Jarmyn (that's just what he said) 'll just go clean off his chump with joy when I tell him about it, and plump down a twenty-ounce nugget, and say, Drinks all round, and take it out o' that.'"

"I always did believe in the old times coming back," commented the interested Jarmyn.

By this time the news had travelled round that there was a stranger in the town, and one after another the Maranoos walked in. The talk became general, and all the old residents claimed to have known Tom Bates.

"And where may he be now?" asked the landlord.

"Tom Bates! Why, the poor old chap, he's lying dog sick in the orsepittal in Gobungalong. 'Jim,' he says to me, 'I'll pull round right enough. You go ahead, and wait for me at Maranoo, and the time we'll have of it—my colonial!'"

"I suppose," said the landlord, "he didn't let on where it was, did he?"

"He did not. I tell you, we was stone-broke and busted in West Australia, and just for the lack of turning up a slug or two we'd never have got back."

All eyes were fixed on the man who had really been to West Australia, which most of the Maranoos imagined to be somewhere in the neighborhood of New Zealand, and they had no notion exactly where that was.

"What did you want to turn up slugs for?" demanded a native-born Maranoosian. The traveller smiled in a superior manner.

"Slugs is nuggets out there," he condescended to explain.

"When do you think Tom Bates will arrive?" asked the landlord.

Jim Thomson, as he called himself, hesitated. "I want to have a little talk with you about that," he said. "Something atween ourselves—say, after dinner."

It being about that hour, the Maranoos dispersed, talking as they went of the interest to be aroused in their town and the probable disposal of unsalable town allotments.

"It's just this way with Tom Bates," said the hypocrite, after putting away a good, sturdy feed. "I told you as how we were both nigh stumped. Now, when Bates got took bad, and had to lay up in the orsepittal at Gobungalong, he says to me, 'Jim, you take what we've got left, and push on to Maranoo. If there's any of the real old sort who remember Tom Bates, they might advance a little loan, and down I'd come hot foot, and in less than a fortnight you see that place will just roar again!"

The landlord mused solemnly.

"Have a drink," said the traveller, jumping up.

"Mind you, I don't say as they will do it," remarked the landlord after the drinks had been swallowed. "But I don't mind sounding the leading townspeople, and together we might make up a little. How much do you think would be wanted?"

"Say, a matter of five pounds. What's that when you'll have fifty—aye, and fifties—pass over this very counter night after night," and he thumped the counter heavily as though anxious that it should bear witness to the truth of his prediction. Jarmyn nodded approvingly at the sentiment, and they parted for a while.

Now, amongst the townspeople there was, as there usually is in most sleepy-headed bush towns, a man of wonderful acuteness and discernment. In this case the local wiseacre was a kind of carpenter, painter, and Jack-of-all-trades. His name was Coop, and he had once had a wonderful experience. No less than being summoned to Sydney as a witness in a law case. True his evidence had not been required after all; but his expenses had been paid, and as time went on he persuaded himself that he had figured with great distinction in the witness box, had been put through a severe cross-examination by the opposing counsel, whom he had signally put to confusion. When there had been much excitement in the way of extra drinks, he was in the habit of adding something about a banquet and presentation by his Sydney admirers; but this was looked upon with suspicion.

Now, the case of Tom Bates was one to ponder over. He came to the conclusion that, as he expressed it, there was something in it. What that something was he could not explain; but as he was in the habit of remarking, "They can't take an old fox like me in. I've been to Sydney, and learnt all the tricks of the trade. It's my belief"—then a brilliant idea came to him—"Tom Bates has been murdered."

When it came to the matter of making up the £5 he gave nothing himself, but he urged the others to do so.

"Give him rope enough," he said, "it's my belief that that £5 will unearth a ghastly crime."

He communicated his suspicions to the local policeman, when that worthy would be sufficiently awake to listen to him. He held out a vision of promotion and stripes to him. He argued that a murder discovered in Maranoo would give the town as much notoriety as a new gold field. He made himself an objectionable nuisance, even to the easy-going Maranoos.

The £5 was collected, and handed over in one note to the swagman, who publicly placed it in an envelope with a letter, urging Tom Bates to immediately hasten to Maranoo, dead or alive, and point out the scene of the future rush. This envelope, with enclosure, was solemnly handed over to Jarmyn to post and register, and he rose to the occasion and shouted for all hands to drink success to the new rush.

"It's my belief," said the knowing man to the policeman, "that he's suspicious of us. He saw that I read him like a book, and I noticed he changed color. I must have seen him when I was in the court in Sydney. If he heard me trounce that barrister no wonder that he felt queer all over."

The policeman yawned. He was rather tired of Coop.

Another bright idea now occurred to Coop. As he was in the habit of saying, "Give me the opportunity, and see me rise to it." He determined to watch the pub that night to see that the guilty man did not escape. He did so, but without result. Not to be done, however, he invented such an adventurous recital of the night's proceeding, that he staggered even the constable. If Coop was willing to swear anything—no matter what—before the local J.P.—he would take upon himself to arrest the traveller on suspicion, but without the ceremony of swearing he professed that the law could do nothing.

Coop hesitated, but led on by vain glory, made an affidavit that to the best of his belief the man Thompson had murdered his mate Bates, in order to obtain possession of information concerning the whereabouts of a rich deposit of gold in the abandoned workings at Maranoo. It took a lot of trouble to induce the policeman to assist in the night watch, but Coop assured him that it must lead to fortune, and he consented to try an hour or two.

No one was more surprised than Coop when, after all had retired, they saw the traveller emerge from the public house, swag on shoulder. He stood still for a minute, looked up and down the deserted road; then, taking what is known as "a sight" at the building he was leaving, strode off.

Coop nudged the policeman, and they followed. "Be careful," whispered Coop, trembling somewhat, "he's a desperate man."

But the policeman, if stolid, was not afraid. He walked quickly after the swagman, who turned sharply when he heard the following footsteps.

"I arrist you on suspicion of having caused the death of one Thomas Bates, and ivery word you say will be used against you," he gabbled off.

The traveller stood quietly enough taking in the sense of what he said, then burst out laughing. "Hang it all mate, it's only a joke. I'm Thomas Bates myself."

"Oh that be blowed," said Coop, who had recovered confidence on seeing that there was no bloodshed imminent. "I knew Tom Bates well, none better. We were like brothers when he was here."

But the swagman still laughed. "You fool, Coop, don't you remember me? Not that we were ever very chummy, but many's the time I've shouted drinks for you when I had the stuff. Look here, I tell you I'm Tom Bates, so how can I have murdered myself?"

The policeman was puzzled. "If you had, it would be suicide, and I arrest you for murder."

"Arrest me! You can't arrest me for killing myself when I'm alive!"

"Oh, but I can, though, and I do. Coop here swears that you made away with one Thomas Bates."

"Coop does? Look here, you little varmint, I'll bring a double action against you for destitution of character and illogical imprisonment. How about that wife you deserted in Rattington? How about that drunken man you choked?"

Coop waited to hear no more, but departed.

"Have I got to go with you because that bally little liar has told you some cock and bull story?"

"Yes; we must have it cleared up now. Come along."

The swagman went.

So impressed were the townspeople with their belief in their coming benefactor Tom Bates that they absolutely refused to recognise the real Simon Pure, and Coop met with universal scorn and derision for starting the trouble. Moreover, the policeman related the accusations the swagman had thrown at him, and his wife coming to hear of it, the life of poor Coop became a burden and a reproach, besides which he was haunted by a dread of divers and unknown penalties being inflicted on him in the event of the traveller being Bates himself.

The case went up to the neighboring town, but as it all rested on the alleged disappearance of a man whose existence no one was sure of, there was naturally nothing in it. Gobungalong being appealed to, replied that everyone but a wooden-headed Maranoo man knew that there was no such thing as an hospital in Gobungalong; consequently, there never had been a Tom Bates there. The letter containing the enclosure was returned.

The traveller was discharged, accordingly, with a stern admonition not to come to that part of New South Wales again playing jokes on quiet people. He apologised; said that he only wanted to walk the first few miles in the cool night, his meals had been paid for, he had committed no crime—would the bench see fit to grant him something from the poor-box to help him along after this unjust and unlawful detention.

The presiding magistrate said that he was very sorry, but there was no poor-box. The Maranoo people should give him something by way of compensation; but they had all hastily left the court.

Jarmyn assembled the subscribers and paid them back their subscriptions to the Bates fund; then he locked the note up, and Maranoo was happy and sleepy, once more.

One month afterwards the disgusted commercial who paid Maranoo a periodical visit came on his rounds. Jarmyn had an account with him, and handed him the torn £5 note in payment.

The commercial looked at it, smiled, and gave it back. "What's the matter with it?" asked the astonished publican. "Aint it a good 'un?"

"It was once upon a time," replied the commercial, "but that bank is one of those that have burst up."

Jarmyn looked at the commercial in astonishment and dismay. "Why, I got it from the branch bank in Oraka myself, and the bank was open the other day."

He looked again at the note long and wistfully. "Blamed if I think it's the same," he muttered. Nor was it. The note had been changed by the swagman—a common enough trick, and not requiring much dexterity, as the commercial explained.

"Bust me, if he didn't want compensation!" roared Jarmyn. "I'll compensate him if I catch him!"

Strange to say, the townsfolk, while most sympathetic, did not see their way to handing back the contributions Jarmyn had returned to them, and there are now two factions in the once sleepy town. The Jarmynites are those who did not subscribe, and the anti-Jarmynites are those who did. Both parties detest Coop, and the policeman is watching for an excuse to run him in.

THE man in the boat stood up and looked at the shore he was slowly approaching; it appeared to be lonely and uninhabited. A sandy core, almost directly opposite, invited a landing, and that was the most hospitable thing to be seen. But the prospect seemed to please the man in the boat. He sat down and pulled wearily to the land, directing his course towards a clump of mangroves at the southern end of the little beach. The sea was calm, for the day was almost windless, and he landed without experiencing any difficulty. First, concealing the battered craft amongst the mangroves, he then hunted amongst the rocks above high-water mark till he found a little hole, still containing fresh water, left by a storm of the preceding day. Of this he drank deeply, and returning to the boat, took from the stern locker the scant materials for a meal, and sitting down devoured them ravenously.

"A wasted life," he muttered to himself when he had finished. "To think that in my despair and madness I should have urged him on to a needless death;" he arose and shook his clenched fist on high with a dramatic gesture. "But that traitor, that devil shall pay for it with his blood, I swear."

His next proceeding was to load the boat with heavy stones, push her into deep water, and sink her, so as to hide all traces of his landing. Then he lay down upon the hot sand to rest. At first he slept but little, being evidently disturbed by tormenting dreams, but exhaustion won the battle at last, and he sank into a dreamless sleep, that lasted until daylight the next morning. Then he arose, and meditating for a short time, turned his face to the south, and strode along the beach.

He knew that he was on the north coast of Queensland, but how far he would have to toil on before meeting with any help, he knew not. At last, towards noon, he espied a light-ship, moored at her anchorage no great distance from the shore; beyond, a spur from the range ran down into the sea, and formed a jutting cape. He stopped and pondered.

"Government dogs," he said at last, talking to himself as men used to solitude do, and there was a note of hatred in his low voice. "No, I will not surrender, unless obliged. I will look over the ridge ahead first." He struggled on, although evidently wearied out, and it was a couple of hours before he stood on the crest of the cape, and was able to command an extended view to the south. As he looked he gave vent to an exclamation of satisfaction. Some miles away a lugger was anchored close to the beach.

"Trepang fishers. I can trust them," he muttered, and resumed his weary march. The sun had sunk behind the range, when, at last, completely worn out, he stood on the beach opposite the lugger, and, mustering all his remaining strength, hailed her. The hail was heard, and answered, and, after a few minutes, a man got into the dinghy that was floating alongside, and sculled to the beach. The wanderer waded in to meet him. The fisherman, a genial looking fellow, gazed knowingly at him.

"Noumea?" he said, as a matter of course.

"Yes, Noumea, and starving;" returned the escapee in good English.

"Didn't you see the lightship as you came?"

"I did, but—" and the Frenchman gave an expressive shrug.

"Just as well, perhaps you didn't show yourself; old Brankstone puts on as much side as the captain of a man-of-war, ten chances to one the old ass would have shoved you in irons, and signalled to the first steamer."

"And you?" queried the Frenchman. "If you're starving, jump in and come aboard, we'll give you a feed, don't matter to us where you hail from; it looks as though you have had a devilish had time of it.

"Bad time, my God, no man ever went through such a time and lived."

He scrambled into the dingy, and they, were soon on board the lugger, lucre was only one more white man on board, beside the coloured crew, and he so much resembled the rescuer than it was not difficult to put them down as brothers: He looked at his brother and said laconically:

"New Caledonia?"

"Yes," assented the other, "we'll give him a feed and rest, lie's had a devil of a time, like the rest of them from there.

"I have money," urged the Frenchman, hastily.

"Oh, tommy rot. We don't take money from starving men," said the man who had I brought him on board, and whose name was Bob Davidson. "We were just going to have our chow ourselves when you came along, so sit down."