RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

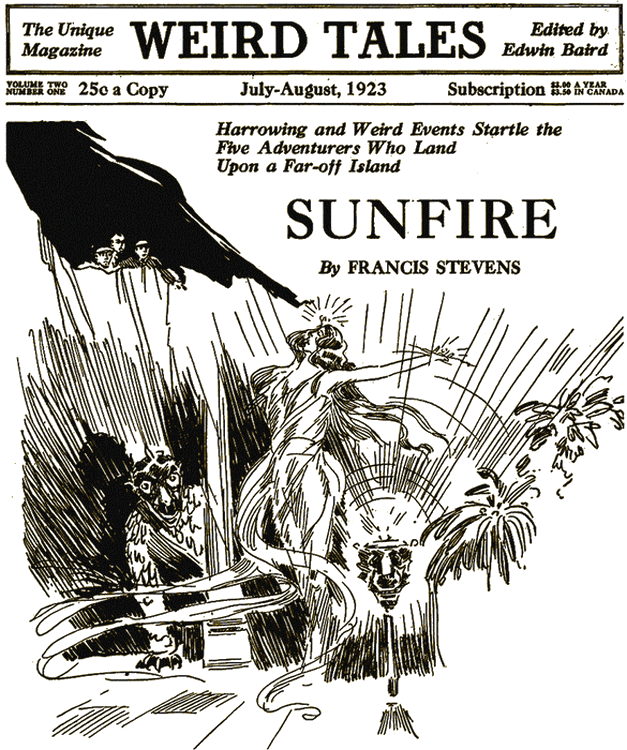

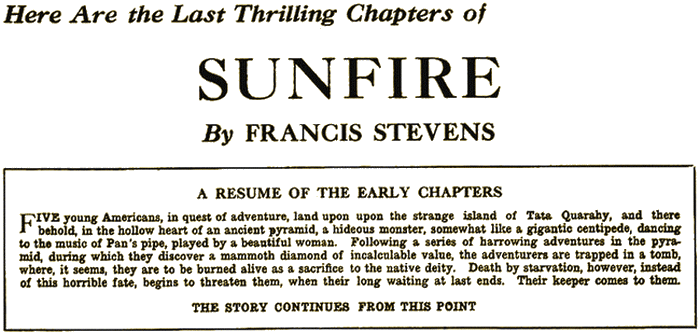

Weird Tales, Jul/Aug 1923, with 1st part of "Sunfire"

Headpiece from Weird Tales, Jul/Aug 1923

IT was close to high noon of the fourteenth day since leaving their motor-yacht, when the five men in the traveling canoe had their first view of the island of "Tata Quarahy," Fire of the Sun.

The walls of the winding river they traveled had grown steeper, higher, barren at last of vegetation. The Rio Silencioso, in its lower reaches a fever-ridden, malodorous stream, here flowed in austere purity. Its color was no longer dark, but a peculiar, brilliant hue—like red gold dissolved in crystal. The effect was partly from reflection of the heights between which it wound, slanting walls of rock, stratified in layers of rich color, from pale lemon to a deep red-orange. The equatorial sun cast its merciless glare over all. The last half- mile of their journey bore a close resemblance to ascending a stream of molten gold flowing through a flaming furnace.

However, the lurid rock walls ended at last. Poling through a channel too narrow for the sweep-like paddles, they floated out on the lake of the island. That it was the place told of by their guide, Kuyambira-Petro, there could be no question. But in the first glance it seemed less like a sheet of water with an island in the midst, than an immense flat plate of burnished gold, and, rising out of it—a pyramid of red flame.

"There is a broad water;" Petro had said. "There is an island. On the island is a strange power and some stone houses."

Had Kuyambira-Petro been taken to view the wonders of modern New York, his report on returning to his native Moju River village would have been much the same—and about equally descriptive.

Here before them, piled terrace upon terrace, constructed of rock that seemed literally aflame in its sunset colors, towered a monstrous mass of masonry. Even from where the canoe lay they could appreciate the enormous size of those blocks which formed the lower tier. Surrounding the pyramid at water-level, extended a broad platform of golden-yellow stone. Immediately above that rose a wall, red-orange in color, thirty feet high, without any apparent breach or means of ascent. Set well back from its upper edge were the first tier of Petro's "stone houses".

They were separate buildings, all of like shape, the end walls slanting inward to a-flat roof. Eight tiers of these, growing gradually smaller toward the top, completed the pyramid. The whole effect of the ponderous artificial mountain was strangely light and airy.

Above the truncated, eight-sided peak, there seemed to hover a curious nimbus of pale light. In the general glare, however, it was easy to suspect this vague, bright crown of being merely an optical illusion.

On board the canoe, the explorer-naturalist, Bryce Otway, turned a painfully sunburned countenance to Waring, war- correspondent and writer of magazine tales.

"It's there!" he breathed. "It's real! You see it, too, don't you! And, oh! man, man, well be the first—think of it, Waring!—the first to carry back photographs and descriptions of that to the civilized world!"

"Rather!" Waring grinned. "Take one thing with another, what a story!"

The other three, the young yacht-owner, Sigsbee, the little steward, Johnny Blickensderfer, more often known as John B., and Mr. Theron Narcisse Tellifer, pride of Washington Square in New York City, each after his own fashion agreed with the first speakers.

They had toiled hard and suffered much to reach here. Sigsbee's motor-yacht, the Wanderer, they had been forced to leave below the first rapids. The canoe journey had begun with four caboclos, half-breed native Brazilians, beside the guide, Petro, to take the labor of paddling.

Every man of these natives had succumbed to beri-beri, inside the first week. The epidemic spared the white men, doubtless because of their living on a different diet than the farina and chibeh, or jerked beef, which is the mainstay of native Brazil. Having come so far to solve the mystery of the Rio Silencioso, the five survivors would not turn back.

Rio Silencioso—River of Silence indeed, flowing through a silent jungle-land, where ho animal life stirred or howled, where there was only the buzz of myriad stinging insects to heighten rather than break the quiet of the nights. Others before them had tried to conquer the Silencioso. None had ever returned —none, that is, save the old full-blood Indian, Kuyambira- Petro. His story had interested the party of Americans on the Wanderer, and, though the guide himself had perished, brought them at last to this strange lake and pyramid. Reluctantly, merely because even a half-mile of further paddling under the noon sun promised to be suicidal, the heavy stone, used for an anchor was dropped to a gravel bottom six feet below. Preparations were made for the mid-day meal and siesta.

From where they lay, the lake appeared as a nearly circular pool, sunk in the heart of this surviving bit of what had once been a great chapadao, or plateau, before a few thousand years of wet-season floods had washed most of it down to join the marsh and mire of Amazon Valley. The outlet by which they had entered formed the only break in its shores. It was probably fed by springs from below, accounting for the crystal purity of its waters and the clean gravel of its bottom. Reflected from the shallow depths, the heat proved almost unbearable. Yet no one felt inclined to complain.

"Gehenna in temperature," as Tellifer, the esthete of the party phrased it, "but the loveliness of yon mountain of pyramiding flame atones for all!"

Sprawled in the shade of awning and palm-thatched cabin, they panted, sweated, and waited happily for the hour of release.

Around four-thirty came a breeze like the breath of heaven. The waters of the lake stirred in smooth, molten ripples. Across them moved a canoe-load of eager optimists. The vague haze of white glare that had seemed for a time to hover above the pyramid had vanished with the passing of the worser heat.

On the side which faced the river outlet, the thirty-foot wall, which formed the first tier, boasted neither gateway nor stair. Since it seemed likely that the ancient builders had provided some means of ascent more convenient than ropes or ladders, the canoe turned and circled the pyramid's base.

On closer view, the flame-colored wall proved to be a mass of bas-relief carved work. In execution, it bore that same resemblance to Egyptian art which marks much work of the ancient South and Central American civilizations. The human figures were both male and female, the men nude, bearing platters of fruit and wine-jars, the women clad in single garments hanging from the shoulders. The men marched, but the women were presented in attitudes of ceremonial dance; also as musicians, playing upon instruments resembling Pan's pipes of several reeds.

As Tellifer remarked, it seemed a pity to have spoiled what would otherwise have been a really charming votive procession, by the introduction of certain other and monstrous forms that writhed and twined along the background, and, in some cases, actually wreathed the dancers' bodies.

"Sun-worshippers!" scoffed Waring, referring to a surmise of Otway's regarding the probable religion of the pyramid's builders. "Centipede worshippers—hundred-legger devotees—or do my eyes deceive me? Hey, Otway! What price sun-worship now?"

"Don't bother me!" Otway's voice drifted back happily from the prow. "I'm in the land of undared dreams come true."

Part way around, in that plane of its eight-sided form which faced the west, they found what they were seeking. It was a stairway, fully a hundred feet wide at the base, leading from water-level to the very height of the pyramid, with broad landings at each tier. Where its lowest tread was lipped by the lake, enormous piers of carved stone guarded the entrance. It was a stair of gorgeous coloring and Cyclopean proportion. Its grandeur and welcome invitation to ascend should have roused the exploring party to even greater jubilance. Strangely, however, none of them at first gave more than a passing glance to this triumph of long-dead builders. In rounding the pyramid, indeed, they had come upon a sight more startling—in a way—than even the pyramid itself. Drawn up near the foot of the stair floated a great- collection of boats. They ranged in size front a small native dug-out to a cabined traveling canoe even larger than Otway's; in age, from a rotting, half- waterlogged condition that told of exposure through many a long, wet season, to the comparative neatness of one craft whose owners might have left it moored there a month ago at latest.

These, however, were by no means the whole of the marvel.

Over beyond the small fleet of deserted river-craft, floating placidly on buoyant pontoons, rested a large, gray-painted, highly modern hydro-airplane!

"THE boats," Otway was saying, "are a collection of many years' standing. We have to face the fact that we are not the first to reach this lake, and that, save for Kuyambira-Petro, not one of all those who preceded us has returned down that noble stairway, after ascending it. And that airplane! It has certainly not been here long. The gas in its tanks is unevaporated. Its motors are in perfect order. There is no reason why the man, or men, who came here in it should not have left in the same way—were they alive or free to do so!"

Otway, Alcot Waring and young Sigsbee stood together inside the doorway of one of the buildings in the pyramid's first terrace. The other two, Tellifer and John B., were still on board the canoe, drawn up among the derelict fleet at the landing stage. Otway had demanded a scouting party, before landing his entire force. Though the war-correspondent and Sigsbee had insisted on sharing the reconnaissance, Tellifer had consented to remain as rear-guard on the canoe, with the steward.

Ascending the stairs, the three scouts had turned at the first terrace and entered the building at the right. As they were on the eastern side of the pyramid, and the sun was sinking, the interior was very dim and shadowy. Enough light, however, was reflected through the tall doorway and the pair of windows to let them see well enough, as their eyes grew used to the duskiness.

They had entered a large room or chamber, in shape a square, truncated pyramid, twenty-five feet high, thirty-five in length and breadth. The floor was bare, grooved and hollowed through long usage by many feet. Around its inner walls ran a stone bench, broken at the back by an eight-foot recess. Therein, on a platform of stone slightly higher than the floor, a black jaguar- hide lay in a tumbled heap.

The hide was old and ragged. Its short, rich fur was worn off in many bald spots. Near the niche, or bed-place, a water jar of smooth clay, painted in red and yellow patterns, lay on its side as if knocked over by a hastily rising sleeper.

The walls were covered by hangings, woven of fiber and dyed in the same garish hues as the water-jar. In lifting the jaguar hide, a girdle composed of golden disks joined by fine chains dropped to the floor. The softly tanned hide itself, though worn and shabby, bore all around its edge a tinkling fringe of golden disks. Like those of the girdle, they were each adorned with an embossed hemisphere, from which short, straight lines radiated to the circumference. A crude representation of the sun, perhaps.

"Or free?" Waring inflected, repeating the naturalist's last words.

Bryce Otway flung out his hands in a meaning gesture.

"Or free!" he reiterated. "Man, look about you. These woven wall-hangings are old, but by no means ancient. In this climate, the palm-fiber and glass of which they arc made would have rotted in far leas than half a century. The animal that wore this black fur was roaming the jungle alive, not more than ten years ago. The golden ornaments—the painted pottery—they, indeed, might be coeval with the stones themselves and still appear fresh; but fabric and fur—Why, you must understand what I mean. You must already have made the same inference. This pyramid has been inhabited by living people within recent years. And if recently—why not now?"

"I say!" Sigsbee ejaculated. "What a perfectly gorgeous thing it would be, if you are right! If you are, then the fellows that came in the airplane are probably prisoners. I suggest we move right along upward—to the rescue. There are five of us. Every darn one knows the butt of his gun from the muzzle, and then some. If there are any left-overs of a race that ought to be dead and isn't hanging around here, strafing harmless callers, they'll find us one tough handful to exterminate. Come on! I want to know what's on the big flat top of this gaudy old rock- pile!"

Otway's eyes questioned the correspondent.

"Your party,'" Waring assured. "Agree on a leader—stick to him. But I think Sig's right. That airplane— mighty recent. Something doggone queer in the whole' business. Got to be careful. And yet—well, I'd hate to find those fellows later—maybe just an hour or so too late."

To Sigsbee's frank joy, the explorer smiled suddenly and nodded.

"I want to go on up," he admitted. "But I hesitated to make the suggestion. Petro didn't tell us of any people living here. There's no knowing, though, exactly what Petro really found."

Fifteen minutes later the entire party of five, rifles at ready, pistols loose in their holsters, advanced upon the conquest of the pyramid.

The great stairway led straight to the top. For some reason, connected perhaps with the hazy glare that had seemed to hover over it at noontime, every man of the five was convinced that both the danger and the solution of the mystery Waited at the stairway's head, rather than in any of the silent buildings that stared outward with their dark little windows and doorways like so many empty eye-sockets and gaping mouths.

Ahead, at his own insistence, marched Alcot Waring. A vast mountain of flesh the correspondent appeared, obese, freckle- faced, with small, round, very bright and clear gray eyes. He carried his huge weight up the stairs with the noiseless ease of a wild elephant moving through the jungle.

Just behind him, as the party's next best rifle-marksman, came the steward. John B. was a quiet little man, with doglike brown eyes, gentle manners, and a fund of simply-told reminiscence that covered experiences ranging almost from pole to pole.

Otway, the widely famed naturalist-explorer, peering through round, shell-rimmed spectacles set on a face almost equally round, and generally beaming with cheerfulness, walked beside young Sigsbee, whose life, before the present expedition, had been rather empty of adventure, but who was ready to welcome anything in that line.

Last, Mr. Theron Narcisse Tellifer brought up the rear, not, let it be said, from caution, but because his enjoyment of the view across the lake had delayed him. Tall, lank-limbed, he kept his somber, rather melancholy countenance twisted over one shoulder, looking backward with far more interest in the color of lake and sky than in any possible adventure that might await them. It required a good deal of experience with Tellifer to learn why his intimates used his initials as a nickname for him, and considered it appropriate.

So, in loose formation, the party essayed the final stage of that journey which all those who left their boats to rot at the stairfoot had courageously pursued.

The sun was dropping, swiftly now behind the western cliffs. The vast shadow of the pyramid extended across the eastern half of the lake and darkened tire shores beyond. The stairway was swallowed in a rapidly deepening twilight.

THE first real testimony the five received that they were indeed not alone upon the artificial island of rock came on the wings of a sound.

It was very faint, barely audible at first But it soon grew to a poignant, throbbing intensity. It was a sound like the piping of flutes—a duet of flutes, weaving a strange -monotonous melody, all in a single octave and minor key. The rhythm varied, now slow, now fast The melody repeated its few monotonous bars indefinitely.

The source of the sound was hard to place. At one moment it seemed to drift down from the air above them. At another, they could have sworn that it issued from or through the stair itself. They all paused uncertainly. The abruptness of a tropical sunset had ended the last of the day. Great stars throbbed out in a blue-black sky. The breeze had increased to a chill wind. All the pyramid was a mass of darkness about them, save that above the flat peak there seemed again to hover a faint, pale luminescence.

"Shall we go on?" Instinctively, Otway put the question in a whisper, though, save for the quaint fluting sound, there was no sign of life about them.

Out of the dark, Tellifer answered, a shiver of nervous laughter in his voice:

"Can we go back? The strange thing that has drawn so many hither is calling from the heart of the pyramid. It is—"

"I say, go on," counseled Waring, not heeding him. "Find out what's up there."

"Oh, come along," Sigsbee urged impatiently. "We can go up softly. We've got to find out what we're in for."

Softly, they did go, or as much so as was allowed by a darkness in which the "hand before the face" test failed completely. They had brought a lantern with, them, but dared not light it. Even intermittent aid from pocket flashes was ruled out by Otway. Unseen enemies, he reminded, might be ambushed in any of the buildings to right and left. The stairs, narrower toward the top, were also more uneven. They were broken in places, causing many stumbles and hushed curses. Once, Waring observed in a bitter whisper that the party would have formed an ideal squad for scouting duty across No Man's Land; they would have drawn the fire and located the position of every Boche in the sector.

Next moment Waring caught his own foot in a broken gap. The rattle of equipment and crackle of profanity with which he landed on hands and knees, avenged the victims of his criticism. In spite of mysterious perils, smothered laughter was heard upon the pyramid. Yet none of these indiscretions or accidents brought attack from any quarter. The monotonous fluting continued. As they neared the top, its poignant obligato to their approach grew over more piercing and distinct.

The final half dozen steps were reached at last. A bare two yards wide, they sloped up with sudden steepness. Halting the party, breathlessly silent now, Otway himself crept up this lost flight. From below, his companions saw his head rise, barely visible against the ghost of white luminance that crowned the pyramid. His entire figure followed it, wriggling forward, belly- flat to the surface.

After a long five minutes, they saw him again, this time standing upright. He seemed, as nearly as they could make out, to be beckoning them on. Then he had once more vanished.

Some question entered the minds of all, whether the beckoning figure had been really that of Otway, or some being or person less friendly. With a very eerie and doubtful sensation, they crept up the narrow flight and over the edge. Waring was first. He found himself on a broad, flat platform, or rim of stone. At its inner edge a crouching figure showed against the white glow, now appearing much brighter, flooding up from an open space at the center of the peak. Certain at last that the figure was Otway's, the correspondent catfooted to his side. Over the other's shoulder he looked downward. Then, with a hissing intake of breath, he sank to his knees. Supporting himself with hands on his rifle, laid along the stone rim, he continued to stare downward.

One by one, the others joined the first pair. Very soon, a row of five sun-bronzed, fascinated faces was peering down into the hollow heart of the pyramid.

The eight-sided top consisted of a broad rim surrounding an open space, some hundred and fifty feet across and a third of that in depth. From the point where they knelt, an inner stairway, set at an angle to the eastern plane of the pyramid, led steeply to the bottom of the hollow.

In effect, the place was rather like a garden. On all sides fruit trees, flowering shrubs and palms of the smaller, more graceful varieties, grew out of soil banked off from a central court by a low parapet of yellow stone. It was not the garden effect, however, which had paralyzed the watchers.

Their eyes were fixed upon two forms, circling in a strange, rhythmic dance around a great, radiant, whitely glowing thing, that rested on a circle of eight slender pillars in the middle of the lower One of the forms was that of a woman. Her hair, falling to a little below the shoulders, tossed wildly, a curling, fluffy mass of reddish gold. Arms, legs and feet were bare. A single garment of spotted jaguar hide was draped from shoulders to mid- thigh. For ornament she wore neither bracelets nor anklets, but the jaguar skin was fastened with golden chains and fringed with tiny gold bangles. Upon the red-gold hair a circlet of star-like gems flashed in prismatic glory.

To her lips the woman held a small instrument like a Pan's pipe or golden reeds. It was her playing upon this that produced the double fluting sound. Her dancing partner was a literal embodiment of the great demon, Terror. Its exact length was impossible to estimate. Numberless talon-like feet carried it through the dance figures with a swiftness that bewildered the eye.

The thing had the general shape of a mighty serpent. But instead of a barrel-like body and scaly skin, it was made up of short, flat segments, sandy yellow in color, every segment graced—or damned —with a pair of frightful talons, dagger-pointed, curved, murderous. At. times the monstrous, bleached-yellow length seemed to cover half the floor in a veritable pattern of fleeing segments. Again its fore part would rise, spiraling, the awful head poising high above the woman's.

At such moments it seemed that by merely straightening up a trifle higher, the demonish thing might confront its audience on the upper rim, eye to eye. For, eyes the thing possessed, though it was faceless. Two enormous yellow discs, they were, with neither retina or pupil, set in a curved, polished plate of bone- like substance. Above them a pair of whip-like, yard-long antennae lashed the air. Below the plate, four huge mandibles, that gnashed together with a dry, clashing sound, took the place of a mouth. During one of these upheavals, the head would sway and twist, giving an obviously false impression of blindness Then down it would flash, once more to encircle the woman's feet in loathsome patterns.

Not once, however, did the strange pair come in actual contact. Indifferent to her partner's perilous qualities, the woman pirouetted, posed, leaped among the coils, her bare feet falling daintily, always in clear spaces. The partner, in turn, however closely flashing by, kept its talons from grazing her garments, her flying hair, or smooth, gleaming white flesh.

The general trend of the dance was in a circle about the luminous mass on the central pillars.

"Chilopoda!" a voice muttered, at last. "Chilopoda Scolopendra! Chilopoda Scolopendra Horribilis!"

It sounded like a mystic incantation, very suitable to the occasion. But it was only the naturalist, Bryce Otway, classifying the most remarkable specimen he had ever encountered.

"Chilo-which? It's a nightmare—horrible!" This from Waring.

It remained for John B. to supply a more leisurely identification, made quite in his usual slow, mild drawl:

"When I was steward on the Southern Queen, 'Frisco to Valparaiso," said he, "Bill Flannigan, the second engineer, told me that one time in Ecuador he saw one of those things a foot and a half long. Bill Flannigan was a little careless what he said, and I didn't rightly believe him—then. Reckon maybe he was telling the truth after all. Centipede! Well, I didn't think those things ever grew this big. Real curious to look at, don't you think, Mr. Sigsbee?"

Young Mr. Sigsbee made no answer. What with the soft, glowing radiance of the central object on its pillars, the coiling involutions of one dancer, the never-ceasing gyrations of the other, it was a dizzying scene to look down upon. That was probably why Tellifer surprised every one by interrupting the dance in a highly spectacular manner.

His descent began with a faint sound as of something slipping on smooth stone. This was followed by a short, sharp shriek. Then, twenty feet below the rim, the willow-like plumes, of a group of slender assai palms swished wildly. Came a splintering crack—a dull thud—and "T.N.T." had arrived at the lower level.

It was a long drop. Fortunately, the esthete had brought down with him the entire crest of one of the assai palms. Between the springy bending of its trunk before breaking, and the buffer effect of the thick whorl of green plumes between himself and the pavement, Tellifer had escaped serious injury.

The men on the rim saw him disentangle himself from the palm- crest and crawl lamely to his feet. The girl, only a short distance off, ceased to gyrate. The golden Pan's pipes left her lips. With cessation of the fluting melody, the dry clashing of monstrous coils had also ceased. But in a moment that fainter, more dreadful sound began again.

Up over Tellifer's horrified head reared another head, frightful, polished, with dull, enormous yellow eyes—below them four awful mandibles, stretched wide in avid anticipation. Tellifer shrieked again, and dodged futilely.

TWO of the men left on the pyramid's inner rim were expert marksmen. The heavy, hollow-nosed express bullets from four rifles, all in more or less able hands, all trained upon an object several times larger than a man's head, at a range of only a dozen yards or so, should have blown that object to shattered bits of yellow shell and centipedish brain-matter in the first volley.

John B. was heard later to protest that in spite of the bad shooting light and the downward angle, he really could not have missed at that range—as, indeed, he probably did not. Some, at least, of the bullets fired must have passed through the space which the monstrous head had occupied at the moment when the first trigger was pulled.

But Scolopendra Horribilis, in spite of his awesome size, proved to have a speed like that of the hunting spider, at which a man may shoot with a pistol all day, at a one-yard range, and never score a bull's-eye.

One moment, there was Tellifer, half-crouched, empty hands outspread, face tipped back in horrified contemplation of the fate that loomed over him. There was the girl, a little way off, poised in the daintiest attitude of startled wonder. And there, coiling around and between them, and at the same time rearing well above them, was that incredible length of yellow plates, curved talons and deadly poison fangs.

From the pyramid's rim four rifles spoke in a crashing volley. Across the open level below, something that might have been a long, yellowish blur—or an optical illusion—flashed and was gone. There was still the girl. There was Tellifer. But Scolopendra Horribilis had vanished like the figment of a dream. One instant he was there. The next he was not. And well indeed it was for those who had fired on him that retreat had been his choice!

At the western side of the court was a round, black opening in the floor, like a large manhole. Down this hole the yellowish "optical illusion" had flashed and vanished.

As the crashing echoes of the volley died away, the girl roused from her air of tranced wonderment. She showed no inclination to follow her companion in flight. Judged by her manner, powder-flash and ricocheting bullets held no more terrors for her than had the hideous poison fangs of her recent dancing partner.

She tilted her head, coolly viewed the dim figures ranged along the eastern rim. Then, light as a blown leaf on her bare feet, she flitted toward her nearest visitor, Tellifer.

From above, Waring shouted at the latter to come up. Unless the girl were alone in the pyramid, the volley of rifle-fire must surely bring her fellow-inhabitants on the scene. Worse, the monster which had vanished down the black hole might return.

These perils, Waring phrased in a few forceful words. Seeing that, instead of heeding him, Tellifer was pausing to exchange a friendly greeting with the priestess of this devil's den, Waring added several more, this time extremely forceful words. Their only effect was to draw another brief-upward glance from the girl. Also, what seemed to be a shocked protest from Tellifer. The latter's voice did not carry so well as his friend's. Only a few phrases reached those on the upper rim.

"Alcot, please!" was distinct enough, but some reference to a "Blessed Damozel" and the "seven stars in her hair" was largely lost. At best, it could hardly have been of a practical nature.

The big correspondent lost all patience with his unreckonable friend.

"That—fool!" he choked. "Stay here, you fellows, I'm going after T.N.T.!"

And Waring in turn undertook the final stage of that long journey which so many others had followed, leading to the heart of this ancient pyramid. The five adventurers had the testimony of the pitiful fleet of derelicts at the landing stage that the pyramid had a way of welcoming the coming, but neglecting to speed its departing guests. They had seen the frightful companion of this girl.

And yet when Waring, breathing wrath against his friend, reached the lower level, he did not hale Tellifer violently thence, as he had intended. Instead, those still above saw him come to an abrupt halt. After a moment, they saw him remove his hat. They watched him advance the rest of the way at a gait which somehow suggested embarrassment— even chastened meekness.

"Mr Waring is shaking hands with her now," commented John B. with mild interest.

"This is madness!" Otway's voice in turn was raised in a protesting shout "Waring! Oh, Waring! Don't forget that hundred- legger! Well, by George! You two stay here. I'll run down and make that pair of lunatics realize—"

The explorer's voice, unnaturally harsh with anxiety, died away down the inner stair.

"If they think," said Sigsbee indignantly, "that I'm going to be left out of every single interesting thing that comes along—"

The balance of his protest, also, was lost down the inner stair. John B. offered no reasons for his own descent. Being the last to go, he had no one to offer them to. But even a man of the widest experience may yield to the human instinct and "follow the crowd."

When the steward reached the center of attraction at the lower level, his sense of fitness kept him from thrusting in and claiming a handclasp of welcome, like that which had just been bestowed on his young employer. But he, too, respectfully removed his hat. He also neglected to urge the retreat which would really have been most wise.

The trouble was, as Sigsbee afterward complained, she was such a surprising sort of girl to meet in the heart of an ancient pyramid, dancing with an incredible length of centipede! Some bronzed Amazon with wild black eyes and snaky locks would have seemed not only suitable to the place, but far easier either to retreat from or hale away as a hostage.

This girl's eyes were large, a trifle mournful. Their color was a dusky shade of blue, the hue of a summer sky to eastward just at the prophetic moment before dawn. The men who had come down into her domain made no haste away. Moreover, the need for doing so seemed suddenly remote; almost trivial, in fact. The face framed in that red-gold glory of hair, crowned with stars, was impossible to associate with evil.

By the time Otway had reached the scene, however, and received his first startled knowledge that references to a "Blessed Damozel" were less out-of-place than they had seemed from above, Waring had recovered enough to laugh a little.

"Otway," he greeted, "priestess of the ancient sun- worship—centipede worship—some sort of weird religion— wants to make your acquaintance! You're the local linguist Know any scraps of pre-Adamite dialect likely to fit the occasion?"

The explorer, too, had accepted the welcoming hand and looked into the dawn-blue eyes. He drew a long breath —shook his head over Waring's question.

"I'll try her in Tupi and some of the dialects. But this is no Indian girl. Can't you see, Waring? She's pure Caucasian. Of either Anglo-Saxon or French blood, by those eyes and that hair. Perhaps a trace of Irish. The nose and—"

"For Heaven's sake! Stop discussing her in that outrageous way," urged young Sigsbee, who had fallen victim without a struggle. "I believe she understands every word you're saying."

There was a brief, embarrassed pause. Certainly the grave, sweet smile and the light in the dusky eyes had for an instant seemed very intelligent. But when Waring spoke to her again, asking if she spoke English, the girl made no reply nor sign that she understood him. Otway made a similar attempt, phrasing his question in Portuguese, Tupi—universal trade language of Brazil—and several Indian dialects. All to no avail. French, Italian and German, resorted to in desperation, all produced a negative result. The resources of the five seemed exhausted, when Tellifer added his quota in the shape of a few sounding phrases of ancient Greek.

At that the sweet, grave smile grew more pathetic. As if deprecating her inability to understand, the girl drew back a little. She made a graceful gesture with her slim, white arms—and fled lightly away around the central pillars.

"Greek!" snorted Waring. "Think the Rio Silencioso is the Hellespont, Tellifer? You've frightened her away!"

The esthete defended himself indignantly. "It was an invocation to Psyche! Your frightful German verbs were the—"

"Gentlemen, we are playing the fool with a vengeance! She's gone to call that monstrous hundred-legger up again."

"Beg pardon, Mr. Otway, but you're wrong." John B. had unassumingly moved after the lady. He called back his correction from a viewpoint commanding the western side: "She's only closing the hole where it went down—and now she's coming back."

With needless heat, Sigsbee flung out "You fellows make me tired! As if a girl like that would be capable of bringing harm to anyone, particularly to people she had just shaken hands with and—and—"

"Smiled upon," Waring finished for him heartlessly. "Otway's right, Sig. Playing the fool. And we aren't all boys. Queer place. Too almighty queer! Woman may be planning anything. We must compel her to—There she goes! Bring the whole tribe out on us, I'll bet!"

"Beg pardon, Mr. Waring." John B. was still keeping the subject of discussion well in view. She had disappeared, this time into one of several clear lanes in the banked-off shrubbery that led from the central space toward the Walls. "I don't think the young lady means to call anyone, sir. She's coming back again."

As he spoke, the girl reappeared. In her slim hands she bore a tray-like receptacle made of woven reeds and piled high with ripe mangoes, bananas and fine white guava-fruits.

Here was a situation in which the most unassuming of yacht- stewards could take part without thrusting himself unduly forward. When John B.'s young employer beat him to it by a yard, and himself gallantly took the heavy tray from their hostess, John B. looked almost actively resentful.

Sigsbee returned, triumphant. The tray was in his hands and the girl of dawn-blue eyes drifted light as a cloud beside him.

"If anyone dares suggest that she's trying to poison us with this fruit," he said forcefully, "that person will have me to deal with!"

"Cut it, Sig. Matter of common sense. Know nothing about the girl."

Waring broke off abruptly. A selection of several of the finer fruits was being extended to him in two delicate hands. For some reason, as the girl's glance met his across the offering, the big correspondent's freckled face colored deeply. He muttered something that sounded remarkably like, "Beg pardon!" and hastily accepted the offering.

"'Her eyes,'" observed Tellifer, absently, "'were deeper than the depth of waters stilled at even'."

"Cut it, Tellifer! Please. Girl's a mere child. Can't hurt a child by refusing a pretty, innocent little gift like this fruit.

"She means us no harm," Otway came to his rescue firmly. "As you say, Waring, the girl is a mere child. She has never willfully harmed anyone. God knows what her history has been—a white child brought up by some lingering, probably degenerate members of the race that built this place. But clearly she has been educated as a priestess or votary in their religion. The fresco below, you'll recall, represents a votive procession with women dancers, dressed like this one, playing upon Pan's pipes, with the forms of monster centi—"

"Don't!" Young Sigsbee's boyish voice sounded keenly distressed. He had set down the tray and was reverently receiving from the girl his share of the fruit. "What we saw from the upper rim was illusion—nightmare! This girl never danced with any such horrible monster."

"T.N.T.!"

The exclamation, shout rather, came from Waring. Under the glance of those dawn-blue eyes, the correspondent had been trying to devour a mango gracefully—an impossible feat—when he observed Tellifer strolling over toward the central pillars. That great, glowing, white mass which they supported was of a nature unexplained. Waring, at least, still retained enough discretion to be deeply suspicious of it.

"Come back here!" he called. "We don't know what that thing is, Tellifer. May be dangerous."

The esthete might have been stone-deaf for all the attention he gave. As he approached closer to the glowing thing, the others saw his pace grow swifter—saw his arms rise in a strange, almost worshipping gesture.

And next instant they saw him disappear, with the suddenness of a Harlequin vanishing through a trap in an old-fashioned pantomime.

A portion of the stone floor had tipped up under his weight, flinging him forward and down. They saw him slide helplessly into what seemed to be an open space of unknown depth which the eight pillars surrounded. A faint cry was wafted up from the treacherous pit. Then silence.

Flinging the dripping mango aside, Waring dashed across the floor. The other three were close at his heels. Unlike the- massive construction of all other parts of the pyramid, the eight pillars were slender, graceful shafts of sunset-hued stone. Rising some dozen feet above the pavement, they were placed at the angles of an eight-sided pit, or opening.

The exact shape of the shining mass these pillars supported was more difficult to determine. Its own light melted all its outlines in a soft glory of pale radiance. The light was not dazzling, however. Drawing near to the thing, it appeared more definite. The lower surface, slightly convex, rested at the edges on the tops of the eight pillars. Rising from the eight-sided circumference, many, smaller planes, triangular in form, curved upward to the general shape of a hemisphere. The light of the mass issued from within itself, like that of a great lamp, except that there seemed to be no central brightest point, or focus. Looking at any portion, the vision was somehow aware that the entire mass was lucidly transparent. And yet so transfused with radiance was it that the eye could pierce but a little way beyond the outer surface.

Even in that excited moment, Waring had an odd, fleeting conviction that somewhere, sometime he had looked upon an object similar to this.

"'Ware the edge," he called to his companions—and himself approached it with seeming recklessness.

He was more cautious than he appeared. There were sixteen stones in the pavement around the pillars. Eight of them were pentagonal in shape, the points laid outward. These large slabs alternated with narrow oblong blocks, each based against one of the square pillars, radiating like wheel-spokes. The large slab that had thrown Tellifer might be the only treacherous one, or all the pentagonal blocks might be pivoted beneath. Should the spoke-like oblongs drop, however, any one of them would fling its victim against one of the pillars, instead of into the pit.

Waring did not stop to think this out. He merely instinctively assumed that the spoke-like stones were comparatively safe. Running to the inner end of one of thorn, he flung his arm about the pillar and bent forward, peering into the pit.

His companions had paused a little way behind him. They all knew what a really deep regard had existed between the big correspondent and the eccentric esthete. There was something pitifully tragic in seeing that great bulk of a man poised there, one arm stiffly outstretched, staring down into the abyss that had engulfed his friend.

They heard him draw a long, quivering sigh. When he spoke, his deep tones noticeably trembled:

"Like it down there! Darn you, T.N.T.! Next time I hear your death cry—stop and smoke a cigar before I charge around any! What's wrong? Lost your voice?"

Respect for tragedy appearing suddenly out of place, the other men followed Waring to the edge.

That is, Otway and John B., having noted the correspondent's path of approach, followed to the edge. Young Sigsbee, less observant, merely avoided the particular slab that had thrown Tellifer. He stepped out on the pentagon next adjoining and took one cautious stride.

The archaic engineers who balanced those slabs had known their business perfectly. The pointed outer ends were bevelled and solidly supported by the main pavement. But the least additional weight on the inner half was enough for the purpose intended. Sigsbee tried in vain to fling himself backward. Failing in that, he sat down and slid off a forty-five degree slope to join Tellifer.

As he disappeared, there came a little, distressed cry—the first sound of any kind which the dancer had uttered. The girl ran out along one of the oblong paths to cling round a pillar and stare down after Sigsbee.

The pit beneath the lucent mass was octagonal at the top, but, below, it curved to a round bowl-shape. Dead-black at the bottom, the upper planes shaded from brown to flame-orange. It was not over a dozen feet deep at the center. Tellifer, it seemed, had been standing in the middle, arms folded, face thrown back, contemplating the under surface of the shining mass above him with a rapt, ecstatic interest which took no heed of either his predicament or his friend's irritated protest. He had attention for nothing save the lucent mass. When Sigsbee in turn arrived, knocking the esthete's feet from under him, Tellifer emerged from the struggling heap, more indignant at being disturbed, than over his badly kicked shins.

In a moment he had resumed his attitude of entranced contemplation.

Standing ruefully up beside him, Sigsbee angered several eager questions hurled by the others, with an acerbic: "How do I know? Ask him! I can't see anything up there but a lot of white light that makes my eye? ache. I say, you fellows, won't you throw me a line or something and haul me out? Tellifer can stay here, if he admires the view so much. I can't see anything in it."

He glanced down at his clothes disgustedly, inspected a pair of hands the palms of which were black as any negro's.

"The bottom of this hole," he complained, "is an inch deep in soft soot! What a mess!"

"Soot!" Adjusting his shell-rims, Otway viewed the bottom of the bowl with new interest. "What kind of soot!"

"W-what? Why, black soot, of course. Can't you see? It's all over me, and Tellifer, too—only I don't believe he knows it." The younger man's wrath dissolved in a sudden giggle. "Niggers! Sweeps! Is my face as bad as his?"

"You don't understand," persisted Otway eagerly. "I mean, is it dry, powdery, like the residue of burned wood, or is it—Dr—greasy soot, as if fat had been burned there! What I'm getting at," he peered owlishly around his own pillar toward Waring's, "is that sacrifices may have been made in this pit. Either animal or human. Probably the latter. I've a notion to fall in there myself and see—"

"Well, you can if you want to, but help me out!" Sigsbee gazed in dawning horror at the black stuff coating his hands and clothing. "It is greasy! Help me up quick, so I can wash it off!"

"Mustn't be so finicky, Sig," chuckled Waring. "You aren't the burnt offering, anyway.' At least, not yet. Hello! What's wrong with our little friend!"

Face buried in her hands, the girl had sunk to a crouching position behind the pillar. Soft, short, gasping sounds came from her throat. Her whole slender body shook in the grip of some emotion.

"Why, she's crying!" said Otway.

"Or laughing." Sigsbee looked from his hands to Tellifer's face. "I don't blame her," he added loyally.

"Beg pardon, Mr. Sigsbee, but the little lady is crying." John B. had quietly left his own post and walked out on the dancer's oblong of safety. "I can see the tears shining between her fingers," he added gravely.

Four helpless males contemplated this phenomenon through a long quarter-minute of shocked silence. Suddenly Otway flung up his hands in a gesture so violent that it nearly hurled him headlong into the pit.

"Gentlemen," he cried desperately, "what is this place! Where are the people who must be about it somewhere! Who and what is that girl! Why is she crying! And what in the name of heaven is that great thing shining there above a sooty pit surrounded by man-traps!"

It was Tellifer who took up the almost hysterical challenge. He came to life with a long sigh, as of some great decision reached.

"Your last question," he said, "in view of the object's obvious nature, I assume to be purely oratorical. The others are of small importance. I have been deciding a real and momentous question—one the answer to which is destined to be on the lips of men in every quarter of the terrestrial globe, and but for a day or a year of fame, but through centuries of wondering worship! And yet," Tellifer waved a sooty hand in a gesture of graceful "deprecation," with all of what I may term my superior taste and intellect, I have been unable to improve on the work of that primitive but gifted connoisseur, Kuyambira-Petro.

"He has already christened this thing of marvelous loveliness. When he told us of this island he said that there presided here an anyi —a spirit—a strange power—and he called it Tala Quarahy! We could not understand him. The poor fellow's simple language had not words to describe it further. And yet, how perfectly those two words alone did describe it! Tala Quarahy! Sunfire! Why not let the name stand! Could any other be more adequate! 'Sunfire!' Name scintillant of light. Let it be christened 'Sunfire,' that even the fancy of men not blessed to behold it with material eyes, may in fancy capture some hint of a supernal glory. But perhaps," Tellifer glanced with sudden anxiety from face to face of his bewildered companions above him, "perhaps I take too much on myself, and you do not agree."

"T.N.T.," said Waring desperately, "for just one minute, talk sense. What is that thing up there—if you know!"

Tellifer's entranced vision strayed again to the huge bulk that seemed, in its radiant nimbus, to hover above rather than rest on the eight columns.

"I beg your pardon, Alcot," he said simply. "I really believed you knew. The phosphorescent light—the lucent transparency—the divine effulgence that envelopes it like a robe of splendid—Alcot, please! There is a lady present. If you must have it in elementary language, the thing is a diamond, of course!"

GETTING the two entrapped ones out of the sooty pit proved fairly easy. The sides of the bowl were smooth, but a couple of leather belts, buckled together and lowered, enabled the men below to walk up the steep curve, catch helping hands and be hauled to the solid paths behind the pillars.

Four of the men then retired from the treacherous ground, and in an excited, disputing group stood off, walked about, and from various viewpoints and distances attempted settling, then and there, whether Tellifer was or was not right in his claim that the enormous glowing mass above the pit was a diamond.

It must he admitted that for quite a time, the girl was forgotten. Only John B. failed to join in that remarkable dispute.

"Half a ton at least!" protested Waring. "Preposterous! Heard of stones big as hen's eggs. But this! Roc's egg! Haroun al Raschid—Sindbad—Arabian Nights! You're dreaming, T.N.T.! Half a ton!"

"Oh, very well, Alcot. It is true that I have some knowledge of precious stones, and that in my humble opinion Sunfire is as much a diamond as the Koh-i-noor. But of course, if you assure me that it is not—"

"How many karat is half a ton!" queried Sigsbee. "I say, Tellifer, how about that young mountain for a classy stickpin!"

"I refuse to discuss the matter further!" Tellifer's voice quivered with outraged emotion. "If either of you had the least capacity for reverent wonder, the faintest respect for the divinely beautiful, you would—you would hate anyone who spoke flippantly about Sunfire!"

"Gentlemen,"—Otway had dropped out of the discussion us he found its heat increasing—"why not leave deciding all this for a later time! Haven't we rather lost sight of our object in ascending the pyramid? What of those air-men whom we were so eager to rescue?"

Followed a somewhat shamefaced silence. Then the disputants, even Tellifer, agreed that the surprising line of entertainment afforded by the pyramid had indeed shifted their thoughts from a main issue.

"But we haven't seen anybody in need of rescue, so far," defended Sigsbee. "There is no one here but the girl."

"Beg pardon, sir." John B. had at last rejoined the group. In his brown eyes was a sad, mildly thwarted look, somewhat like that in the eyes of a dog left outside on the doorstep. "The young lady isn't here now, sir. After you and Mr. Tellifer climbed out of the pit, she seemed real pleased for a while and stopped crying. I tried talking to her, and I tried eating some of her fruit, but she didn't seem very much interested. And just now she went away. She went," John B. pointed down one of the open lanes, "out through that door and shut it behind her."

The steward paused. "And bolted it on the other side," he finished sadly.

The four eyed one another. There was mutual scorn in their glances.

"As a rescue party," opined Otway, "we are a fraud. As explorers of a perilous mystery, we are extremely unwise. As diplomats, we are a total loss. There we had a friend from the enemy's ranks who might have been willing to help free the prisoners—if there are any. She was intelligent. We might have communicated with her by signs. Now we have offended the girl by our neglect. If she returns at all, it may be in company with hostile forces."

"We've hurt her feelings!" Sigsbee mourned.

"All too darn queer!" reiterated Waring. "Rifle- fire—shouting—produced not a sign of life anywhere—except this girl."

"Of course, she may really be alone here." Removing the shell- rims, Otway polished them thoughtfully. He replaced them to stare again at the radiant mass of "Sunfire."

"Whether that thing is or is not a diamond," he continued, "one can understand Petro's characterizing it as an anyi, or spirit. To a mind of that type, the inexplicable is always supernatural. It is obvious, too, that—something or other is frequently burned in that pit. The girl wept because two of us had fallen in! I wonder what manner of horrible sights that poor child has witnessed in this place!"

Again Sigsbee bristled. "Nothing bad that she had any hand in!"

"Did I even hint such a thing!" The explorer's own amiable tone had grown suddenly tart; then he grinned. "Between the questions of 'Is it a diamond!' and 'Why is the girl!' we shall end by going for one another's throats. Suppose that instead of wasting time in surmise, we undertake a tour of inspection. We haven't half looked the place over. There may be other exits than the one our displeased hostess locked behind her. You are sure that it is locked, Blickensderfer!"

John B. nodded. "I heard her slide a bolt across. Besides, I tried it with my shoulder, sir."

"Very well. We'll hunt for other doorways."

Viewed from the central court, the eight walls of the great place were mostly invisible. Though the greatest of the palms were not over thirty feet tall, the radiance of Sunfire was not enough to illuminate the upper heights. The lower walls were hidden by a dense-luxuriance of vine-bound foliage.

Following one of the paved lanes cut through this artificial jungle, they discovered that another path circumscribed the entire court, between walls and shrubbery. By the use of their pocket-flashes they learned also that these inner walls were carved with Titan figures like those of the fresco which banded the pyramid's outer base.

The walls were perpendicular. At this level, there must be a considerable space between their inner surface and the outer slope. That it was not a space entirely filled with solid masonry was proved by the fact that at the end of each clear lane was a doorway. These exits, like those of the outer buildings, bore the shape of a truncated triangle. But, unlike them, they were not open, but blocked by heavy, metal doors, made of bronze or some similar metal. The one through which the girl had passed was set in the south-eastern wall. It was indeed fastened.

In circling the boundary path they encountered two more similar doors, one centering the southern wall and one the south- western, both of which resisted all efforts to push them open. Reaching the western side, however, they found, not one, but eight doors.

These were not only of different construction from the others, but all stood wide open. They faced eight very narrow paths through the greenery, running parallel with one another to: the central court. The overarching shrubbery shut out Sunfire's light But the party's pocket flashes made short work of determining where these eight portals led.

The entire party were rather silent over it, at first. There was something ominous and unpleasant in the discovery.

"Eight prison cells!" said Otway at last. "Eight cells, with chains and manacles of bronze, all empty and all invitingly neat and ready for the next batch of captives. I don't know how you fellows feel about it, but it strikes me we needn't have hurried up here. Our unlucky friends of the air-route are, I fear, beyond need of rescue."

Waring stood in the doorway of one of the empty cells. Again he flashed his light about. It was square, six feet by six at the base, in inner form bearing the shape of a truncated pyramid—save in one particular. The rear wall was missing. On that side the cell was open. A black shaft descended there. That its depth was the depth of the pyramid itself was proved when John B. tossed over the remains of a guava he had been eating. The fruit splashed faintly in water far, far below.

"For the prisoner. Choice between suicide and sacrifice," hazarded the correspondent. "Cheerful place, every way. These leg cuffs have been in recent use, too—not much doubt of that." The manacles were attached to a heavy chain of the bronze-like metal that in turn was linked to a great metal ring set in the floor. The links were bright in places, as if from being dragged about the floor by impatient feet.

"Suicide!" repeated Otway. "My dear fellow, how could a man fastened up in those things leap into the shaft behind!"

"One on me. Captive of these elephant-chains would certainly do no leaping. These triangular openings in the doors—"

"To admit light, perhaps. More likely to pass in food to the prisoner. But where are the jailers! Why are we allowed to come up, let off our guns at the sacred temple pet, be amiably entertained by the—priestess, or whatever she is, climb in and out of the sacrificial pit, and generally make ourselves at home, without the least attempt at interference."

"Came on an off night," Waring surmised. "Nobody home but Fido and little Susan."

"Alcot!" Again the esthete's tones sounded deeply injured. "Can your flippancy spare nothing of the lovely mystery—"

But here Waring exploded in a shout, of mirth that drowned the protest and echoed irreverently from the ancient carven walls.

"Lovely mystery is right, Tellifer! Lovely idiots, too! Stand about and talk. Stairway fifty yards off. Hole of that hell-beast between stairway and us. Somebody sneak in and let Fido loose again—hm! We can't shoot him. Proved that. Might as well try to hit a radio message, en route."'

"But the noise and the flash drove him off," reminded Otway. "Remember, the courage of the invertebrate animals is of a nature entirely different from that of even the reptilia. Friend 'Fido,' as you call him, is after all only an overgrown bug—though I shatter my reputation as a naturalist in misclassifying the chilopoda as bugs."

"Oh, can him in the specimen jar later, Professor. Come on around the northern side. Haven't looked that over yet."

"Beg pardon, sir." John B. had strayed on, a little beyond the last of the eight cells. He was examining something set against the wall there.

"I wonder what this is meant for! It feels like some sort of a handle—or lever."

His companions joined him. The steward's discovery was a heavy, straight bar of metal set upright, its lower end vanishing through an open groove in the pavement, standing about the height of a man's shoulder above it.

"It's a switch," asserted Waring gravely. "Electric light switch. Throw it over—bing! Out will go T.N.T.'s 'diamond'!"

Battle glinted again in Tellifer's moody eyes.

"It is an upright lever," said he, "intended to move something. Though I make no pretensions to the practical attitude of some others here, I can do better than stand idly ridiculing my friends when there is a simple problem to be solved in an easy and direct manner."

"T.N.T.! I apologize! Don't!"

But Tellifer had already grasped the upright bar. He seized it near the top and flung his weight against it. The bar moved, swinging across the groove and at the same time turning in an arc. Where it had been upright, it now slanted at a sharp angle.

"Oh, Lawdy! he's done it! What'll happen now!"

The correspondent's eyes, and those of the others also, roved anxiously about what could be seen of the walls and central court. But their concern over Tellifer's rash act appeared- needless. So far as could be seen or heard; throwing over the lever had produced no result.

Tellifer alone was really disappointed.

"Old, ugly, worn-out mechanism!" he muttered. And released the lever.

As if in vengeance for Tellifer's slighting remark, the lever flew back to the upright position with a speed and violence which flung the experimenter sprawling. The reversal was accompanied by a dull, heavy crash that shook the very floor beneath their feet.

"That was out in the central court!" shouted Sigsbee. "He's wrecked his 'diamond,' I'll bet!"

"Nonsense! The light is still there."

Waring started along the nearest lane. Then turned back and went to his friend, who had not risen.

"Hurt?" he demanded.

"Only my arm and a few ribs broken and a shoulder out of joint, thank you. But that frightful crashing noise! Alcot, don't tell me that' I have destroyed—destroyed Sunfire!"

"No, no. Your diamond's shining away to beat a Tiffany show- window."

"Hey, there, Waring! Throw that lever again, Will you?"

Otway's voice hailed from the central court, whither he and Sigsbee and the steward had gone without waiting for the other two. As Tellifer's injuries were not keeping him from getting to his feet, the correspondent turned his attention to the fever.

The bar went over without heavy pressure. After a moment Otway's voice was heard again:

"All right. But let her come up easy!"

Once more Waring complied. He found that by slacking the pressure gradually the bar returned to the upright position without violence. This time no crash occurred at the end. Finding that Tellifer had deserted him, Waring left the switch and followed.

He found the other four all draped around Sunfire's supporting columns, staring down into the pit.

"He cracked the bowl," Otway greeted, "and showed us how the sacrificial remains are disposed of. That lever works the dump!"

Waring had selected his oblong safety-path and joined the observers. . He saw that one side of the great stone bowl beneath Sunfire now showed a thin, jagged crevice running from upper edge almost to the bottom.

"Don't understand," frowned Waring.

"I'll work it for you, sir."

The obliging John B. fled to take his turn at the bronze bar. A minute later, Waring saw the whole massive, bowl-shaped pit beneath him shudder, stir, and begin to tip slowly sideways. It continued to tip, revolving as upon an invisible axis. In a few seconds, instead of gazing down into a soot-blackened bowl, he was staring up at a looming hemisphere of flame-orange stone that towered nearly to Sunfire's lower surface, twice the height of a tall man above him.

"Let her down easy, Blickensderfer!" called Otway again. "Afraid of the jolt," he added in explanation. "The remarkable thing is that when Tellifer allowed it to swing back full weight that first time, it didn't smash the surrounding pavement and bring these pillars down. But it merely cracked itself a bit."

Waring gasped. "D'you mean—Did I swing all those tons of rock around with one easy little push on that bar?"

"Seeing is believing," asserted Otway, as the revolving mass turned easily back into place, and they once more looked into a hollow, sooty bowl.

"Those ancient engineers knew a lot about leverage. How were the enormous stones of this pyramid brought across the lake and lifted into their places? This bowl is somehow mounted at the sides like a smelting pot on bars that pass beneath the pavement. That pavement, by the way," and the explorer cast an eager eye across the space between the pit and the western wall, "will have to come up. Uncovering the mechanism which operates this device may give some wonderful pointers to our modern engineers."

"But what's it for?" pleaded Waring.

"Why, you saw the black depths under the bowl. Likely, there is some superstitious prejudice against touching the charred remains of victims burned here. By throwing over the lever, the pit empties itself into the depths below. As I told you before—that lever works the dump."

"What—sacrilege!" Tellifer murmured.

"Well, of course, from our viewpoint it's not a very respectful way to treat human remains. But if you'll think of the cannibalistic religious rites of many primitive peoples, this one doesn't seem so shocking."

"You misunderstood me." Tellifer cast a glance of acute distress toward the gleaming mass above the pit. "I meant the dreadful sacrilege of insulting a miracle of loveliness like that, with the agony and ugly after-sights of human sacrifice!"

"That's a viewpoint, too," grinned Otway.

"And we're still talking! Human sacrifices! Here we stand—candidates—fairly begging for it. Angered priestess gone after barbaric hordes. Shoot us down from above. Regular death-trap. We lake precautions? Not us! We'd rather talk!"

"Beg pardon, Mr. Waring, but the little lady has come back, and she hasn't brought any barbaric hordes."

John B. had returned and his voice sounded mildly reproachful. "She seems to me to be acting real considerate and pleasant. I judge she noticed the soot on Mr. Sigsbee and Mr. Tellifer, and she's gone and taken the trouble to bring some water and towels so they can wash it off!"

THE steward's latest announcement proved correct, though not quite complete. While the guests had been entertaining themselves by inspecting the premises, the hostess must have quietly gone and returned, not once, but several times.

They found her standing beside an array of things which her slender strength could not possibly have availed to transport in a single trip.

There was a large, painted clay water jar. Neatly folded across its top lay a little heap of what might have been unbleached linen, though on examination the fabric proved to be woven of a soft, yellowish fiber, probably derived from one of the many useful species of palms.

Near this jar stood another smaller vessel, of the same general appearance, but surrounded by a half-dozen handleless bowls or cups carved out of smooth, yellow wood, highly polished. And still beside these things was another offering. Waring removed his hat again and ran his fingers through his hair.

"What's the big ideal" he demanded at large. "Water and towels —fine. Sig and T.N.T. sure need 'em. Festive bowls. May be finger-bowls, but I doubt it. Well and good. Though I, for one, draw the line at cocktails where I don't know my bootlegger. But why all the furriers' display? Does she want us to assume the native costume?"

Otway raised the largest of five black jaguar hides which were ranged in a neat row on the pavement.

"Here's yours, Waring," he chuckled. "The beast that grew this was a lord among his kind. You see, it fastens over the shoulders with these gold clasps. And there's a chain girdle. Suppose you retire to one of those eight convenient dressing-rooms and change? Then if the rest of us like the effect—"

"Set the example yourself! I'm no cave-man. But what's her idea?"

"She is trying to drive it through our thick skulls that she means only kindness toward us!" This from Sigsbee, who, having reverently allowed his hostess to pour water over his hands was now, with equal reverence, accepting a fiber napkin to dry them.

As if handling the heavy water jar had at last wearied her, the girl thereupon surrendered it to the steward. Tellifer, with a vengeful glare at his luckier predecessor, proceeded to his ablutions.

"My experience," said Otway, "has been that among strange peoples it is always well to accept any friendly acts that are offered. No matter what one's private misgivings may be, no trace of them should show in one's manner. By that simple rule I have kept my life and liberty in many situations where others had been less fortunate. Despite our suspicions, we have shown not a trace of hostility toward this girl. We have offered no violence nor rudeness. Who knows? If we continue on our good behavior we may find ourselves accepted as friends, not only by the girl but all her foster-people. I've proved it to work out that way more than once."

"She's a mighty nice girl." Waring was weakly accepting a polished yellow cup. "But d'you think we should risk drinking this—purple stuff?"

The explorer sipped testingly at the liquor which his hostess had gracefully poured from the wine jar. "It is only assai wine," he announced. "No harm in it—unless one indulges too freely. See—she is pouring herself a cup! We had best drink, I believe, and then indicate that we would like to meet her people."

"Sensible girl, too," approved Waring. "Cave-man costumes. Nice little gift. But no effort to force 'em on us. Well-bred kid. Out-of-place here, hm?"

"Oh, decidedly," the explorer agreed. "I shall take her away with me when we go."

Otway was a man of morally spotless reputation. As leader of the expedition, he had every right to use the first personal pronoun in announcing his intent to rescue this white girl. Yet the statement seemed displeasing to every one of the explorer's four companions. The glances of all turned upon him with sudden hostility. Sigsbee was heard to mutter something that sounded like "Infernal cheek!"

But Otway gave their opinion no heed. Like the rest, he had drained his cup of purple wine. Innocent though he had claimed the vintage to be, it had deepened the color of his sun-burned face with amazing quickness. The cool gray eyes behind the shell- rims had grown bright and strangely eager. He swayed slightly. He took an unsteady step toward the girl, who had thus far barely stained her lips with the purple liquor.

"Sure!" he added thickly, "Queer I didn't realize that sooner. Girl I've been—waiting for—always! Never got married, just that reason. Looking for this one. Take her away now!"

"You will not!"

Waring's mighty hand closed viselike on the naturalist's shoulder, wrenching him backward.

"Tha's right, Alcot," Tellifer approved. "He couldn't half 'preciate loveliness like hers. Tha's for me! I 'preciate such things. Lovely, girl— lovely diamond—lovely place—lovely 'dventure—"

As if in adoration of the prevailing loveliness of everything, Tellifer sank to his knees, and subsided gently with his head on one of the jaguar hides. Waring discovered that he was not restraining Otway, but supporting his sagging weight. He released it, stared stupidly as the explorer's form dropped limply to the floor.

Something was very much wrong. Waring knuckled his eyes savagely. They cleared for an instant. There stood the girl, Her dawn-blue eyes were looking straight into his. There were great tears shining in them! Her whole attitude expressed mournful, drooping dejection. The golden-yellow cup had fallen from her hand. Across the pavement a purple pool spread and crept toward the little bare white feet.

WARING knew that he, too, had fallen to the floor, and that he could not rise.

Over him was bending—a face. Above it a circlet of star- white gems gleamed with a ghostly luster, The form beneath was draped in the spotted hide of a jaguar, fastened at the shoulders with fine golden chains.

But that face! Old, seamed, haggard, framed in wild locks of ragged, straying gray hair, with terrible eyes whose dark light had feasted through unnumbered years upon vicious cruelty, with toothless mouth distended in awful laughter—a hag's face, the face of a very night-hag—and up beside it rose a wrinkled, claw-like hand, and hovered above his throat!

The vision passed. Merciful oblivion ensued.

AS he had been last to succumb under the terrific potency of that "harmless assai wine," so the correspondent was first to recover his normal senses.

After a few minutes of fogginess, he grasped the main facts of the situation well enough.

In a way, they scarcely even surprised him. Now that the thing was done, he saw with dreary dearness that this had been a foregone conclusion from the instant when five fools, ignoring all circumstantial evidence, had placed their trust in a pair of dawn-blue eyes.

Just at first he had no way of being sure that he was not the sole fool who had survived. But as the others, one by one, awakened and replied to the correspondent's sardonic inquiries, he learned that their number was still complete. Their voices, however, reached him with a muffled, hollow sound. They were accompanied by a clanking of heavy bronze chains, appropriately dismal.

Through the triangular opening in his cell door, Waring could see along a narrow lane in the greenery to the central court. The place was no longer illuminated by the ghostly radiance of Sunfire. It was daytime—and it was rainy weather. Through the open top of the pyramid the rain sluiced down in sheets and torrents, thundering on the palm-fronds, making of that small portion of Sunfire which was visible, a spectral mound of rushing water-surface. It also sent little exploring cold trickles beneath the closed doors of five prison cells—no longer empty.

"Lovely place!" groaned Waring "Oh, lovely! Friends and follow-mourners, it wasn't a new wine. It was the oldest of old stuff. K.O. drops. And we swallowed it! What's that? No, Otway. No more your fault than anyone's. I fell—you fell—we fell. The lot of us needed a keeper. From all signs, we've probably acquired one. It won't be little blue-eyed Susan, though. Her work's done. Such a well-bred kid, too! Wouldn't force native costume on anyone. Oh, no! Say, am I the only cave- man? Or is it unanimous?"

Report drifted down the line that reversion to barbaric fashions had not been forced on the correspondent alone. Not a stitch of civilized clothing, not a weapon, not a single possession with which they had entered the pyramid, had been left to any of the five. In exchange for those things, they had received each a neat stone cell, a handsome black jaguar hide, gold-trimmed, a chain adequate, as Waring had said, to restrain an elephant, —and a hope for continued life so slight as to be practically negligible.

After a time Waring informed the others of that last fading glimpse he had got of a frightful face bending over him. It was agreed that he had been privileged to look upon one of the "tribe" who inhabited the pyramid. No one, however, was able to explain why this "tribe" had allowed all those boats to rot, some of them through years, undisturbed at the landing state. Or why all save the girl were so extremely shy about showing themselves.

The noise of the rain ceased at last. The outer court brightened with sunshine. For any sounds or signs of life about them, the five might have been chained alone in an empty pyramid at the heart of an empty land. The utter strangeness of what had occurred combined with memory of their own folly to depress them. Those cells, too, despite the increasing heat outside, were decidedly chilly. Damp, cold draughts blew up from the open shafts at the back.. Much rainwater had crept in beneath the doors.

The jaguar-hides were warm as far as they went, but from the prisoners' civilized viewpoint, that wasn't half far enough. Bare feet shifted miserably on cold stone. An occasional sneeze broke the monotony. Except for fruit, none of the party had eaten anything since noon of the previous day. The drugged liquor, too, had left an aftermath of outrageous thirst. Yet neither food nor water had been given to them.

The noon hour arrived, as they could tell by diminished shadows and fiercely down beating glare. Still, no attention had come their way.

Tellifer's cell commanded the best view of the main court. As the sun had approached the zenith, the esthete's dampened enthusiasm had to some degree revived. If the lucent mass of Sunfire had been beautiful at night, beneath the noon sun it became a living glory that gave Petro's name for it, Tata Quarahy, Fire of the Sun, new meaning. Tellifer exhausted his vocabulary in trying to do its rainbow splendors justice. But when he finally lapsed into silent adoration the other four made no effort to draw him out of it. Their more practical natures had rather lost interest in Sunfire. Diamond or not, it seemed that the sooty pit beneath it was likely to be of more concern to them.

The sun-rays were now nearly vertical. The central court grew to be a mere dazzle of multicolored refraction. Waves of heat as from a furnace beat through the openings in the cell-doors. With them drifted, wisps of white vapor.

Presently, a low hissing sound was heard. The seething noise grew louder. In the court, great clouds of white steam were rising, veiling the brightness of Sunfire. The pit beneath it seethed and bubbled like a monstrous cauldron.

Practical-minded or not, it was Tellifer who solved the simple dynamics of what was going on.

"I was afraid of this," he said. "I was afraid last night, when I first saw the atrocious manner in which that miracle of beauty has been mutilated. Practically sawn in half, for it is an octahedral stone and must originally have possessed nearly twice its present mass.. But the lower part had been ruthlessly cleaved way, and the under surface ground and polished. The faceting extends only part way up the sides. The top is a polished cabochon. The scoundrels!" Tellifer's voice shook with emotion. "The soulless vandals! Whoever the fiends were, they cut the most marvelous jewel earth ever produced to suit a vilely utilitarian purpose! Sunfire is a great lens—a burning-glass. It is boiling the collected rainwater out of the pit now. When the pit is dry, the stone of its bowl will rise to red heat—White heat—who knows what temperature under that infernal sun? And that means—that means—"

"Death for any living thing in the pit." declared Otway quietly. "With a victim in the pit, sacrifice to the deity must occur at high noon on any day when the sky is free from clouds. But I say—" the explorer's voice was suddenly distressed—"don't take it that way, man! Why, there is always a chance so long as one has breath in one's body. Brace up!"

"Oh, you don't understand! Let me be!" There had been a heavy clanking sound in Tellifer's cell. A thud as of a despairing form cast down. "You don't understand!" repeated the esthete sobbingly. "There's no chance I Or hardly one in a million. And it isn't being killed in that pit that's bothering me. It's—Oh, never mind, I tell you! I don't want to talk about it. The thing is too shameful—too horrible! Let me be!"

As all further questioning was met with stony silence from the central cell, his companions did "let him be," at last.

That hysterical outburst from one of their number had not tended to brighten the general mood. It seemed to them, also, that if Tellifer really foresaw any more shameful and horrible fate than being broiled alive under a burning lens, he might share his knowledge and at least let them be equally prepared for it.

The day wore wearily by, measured only by lengthening shadows and lessening glare. The sudden night fell. There, on the eight rosy pillars, the iridescent splendor of Sunfire changed slowly to its ghostly glory of the dark hours.