Eleven o'clock! Before the vibration of the nearest chimes had died away, the rain—which had long been threatening over London—poured down for some five minutes in a fierce gust, and then, as if exhausted by its efforts, subsided into a steady drizzle. The waves of light, cast on the glistening pavement from the gas lamps flickering in the wind, shone on the stones; but the unstable shadows were cast back by the stronger, refulgence of the electric light at Covent Garden. Back into the gathered mist of Long Acre the pallid gleam receded; while, on the opposite side, the darkness of Russell Street seemed darker still. By Tavistock Street was a gin-shop, whose gilded front, points of flame, and dazzling glass seemed to smile a smile of crafty welcome to the wayfarer. A few yards away from the knot of loafers clustering with hungry eyes round the door, stood a woman. There were others of her sex close by, but not like her, and though her dress was poor and dilapidated to the last degree, the others saw instinctively she was not as they. She was young, presumably not more than five-and-twenty years, and on her face she bore the shadow of great care. Gazing, half sullenly, half wistfully, into the temptingly arrayed window, her profile strongly marked by the great blaze of light farther up the street, the proud carriage of the head formed a painful contrast to her scanty garb and sorrow-stricken face. She was a handsome, poorly dressed woman, with a haughty bearing, a look of ever-present care, and she had twopence in her pocket.

If you will consider what it is to have such a meagre sum standing between you and starvation, you may realise the position of this woman. To be alone, unfriended, penniless, in a city of four million souls, is indeed a low depth of human misery. Perhaps she thought so, for her mind was quickly formed. Pushing back the door with steady hand, she entered the noisy bar. She had half expected to be an object of interest, perhaps suspicion; but, alas, too many of us in this world carry our life's history written in our faces, to cause any feelings of surprise. The barman served her with the cordial she ordered, and with a business-like 'chink,' swept away her last two coppers. Even had he known they were her last, the man would have evinced no undue emotion. He was not gifted with much imagination, and besides, it was a common thing there to receive the last pittance that bridges over the gulf between a human being and starvation. There she sat, resting her tired limbs, deriving a fictitious strength from the cordial, dimly conscious that the struggle against fate was past, and nothing remained for it but—a speedy exit from further trouble—one plunge from the bridges! Slowly and meditatively she sipped at her tumbler, wondering—strange thought—why those old-fashioned glasses had never been broken. Slowly, but surely, the liquid decreased, till only a few drops remained. The time had come, then! She finished it, drew her scanty shawl closer about her shoulders, and went out again into the London night.

Only half-past eleven, and the streets filled with people. Lower down, in Wellington Street, the theatre-goers were pouring out of the Lyceum. The portico was one dazzling blaze of beauty and color; men in evening dress, and dainty ladies waiting for their luxurious carriages. The outcast wandered on, wondering vaguely whether there was any sorrow, any ruin, any disgrace, remorse, or dishonor in the brilliant crowd, and so she drifted into the Strand, heedlessly and aimlessly. Along the great street as far as St. Clement's Danes, unnoticed and unheeded, her feet dragging painfully, she knew not where. Then back again to watch the last few people leaving the Lyceum, and then unconsciously she turned towards the river, down Wellington Street, to Waterloo Bridge. On that Bridge of Sighs she stopped, waiting, had she but known it, for her fate.

It was quiet there on that wet night—few foot-passengers about, and she was quite alone as she stood in one of the buttresses, looking into the shining flood beneath. Down the river, as far as her eye could reach, were the golden points of light flickering and swaying in the fast-rushing water. The lap of the tide on the soft oozing mud on the Surrey side mingled almost pleasantly with the swirl and swish of the churning waves under the bridge. The dull thud of the cabs and omnibuses in the Strand came quietly and subdued; but she heard them not. The gas lamps had changed to the light of day, the heavy winter sky was of the purest blue, and the hoarse murmur of the distant Strand was the rustling of the summer wind in the trees. The far-off voices of the multitude softened and melted into the accents of one she used to love; and this is what she saw like a silent picture, the memories ringing in her head like the loud sea a child hears in a shell. A long old house of grey stone, with a green veranda covered with ivy and flowering creepers; a rambling lawn, sloping away to a tiny lake, all golden with yellow iris and water-lilies. In the centre of the lawn, a statue of Niobe; and seated by that statue was herself, and with her a girl some few years younger—a girl with golden hair surrounding an oval face, fair as the face of an angel, and lighted by truthful velvety violet eyes. This was the picture mirrored in the swift water. She climbed the parapet, looked, steadily around: the lovely face in the water was so near, and she longed to hear the beautiful vision speak. And lo! at that moment the voice of her darling spoke, and a hand was laid about her waist, and the voice said: 'Not that way, I implore you—not that way.'

The woman paused, slowly regained her position on the bridge, and gazed into the face of her companion with dilated eyes. But the other girl had her back to the light, and she could not see.

'A voice from the grave. Have I been dreaming?' she said, passing her hand wearily across her brow.

'A voice of providence. Can you have reflected on what you were doing? Another moment, and think of it—oh, think of it!'

'A voice from the grave,' repeated the would-be suicide slowly. 'Surely this must be a good omen. Her voice!—how like her voice.'

The rescuing angel paused a minute, struggling with a dim memory. Where had she in her turn heard that voice before? With a sudden impulse, they seized each other, and bore towards the nearest gaslight, and there gazed intently in each other's face. The guardian angel looked a look of glad surprise; the pale face of the hapless woman was glorified, as she seized her rescuer round her neck and sobbed on her breast piteously.

'Nelly, Miss Nelly, my darling; don't you know me?'

'Madge, why Madge! O Madge! to think of it—to think of it.'

Presently they grew calmer. The girl called Nelly placed the other woman's arm within her own and walked quietly away from the hated bridge; and, thoroughly conquered, the hapless one accompanied her. No word was spoken as they walked on for a mile or so, across the Strand, towards Holborn, and there disappeared.

The night-traffic of London went on. The great thoroughfares plied their business, unheedful of tragedy and sorrow. A life had been saved; but what is one unit in the greatest city in the universe? The hand of fate was in it. It was only one of those airy trifles of which life is composed, and yet the one minute that saved a life, unravelled the first tiny thread of a tangled skein that bound up a great wrong.

Two years earlier. It was afternoon, and the sun, climbing over the house, shone into a sick-room at Eastwood—a comfortable, cheerful, old room; from floor to ceiling was panelled oak, and the walls decorated with artist proofs of famous pictures. The two large mullioned windows were open to the summer air, and from the outside came the delicate scent of mignonette and heliotrope in the tiled jardinieres on the ledges. The soft Persian carpet of pale blue deadened the sound of footsteps; rugs of various harmonious hues were scattered about; and the articles of virtù and costly bric-à-brac were more suitable to a drawing-room than a bed-chamber.

On the bed reclined the figure of a man, evidently in the last stage of consumption. His cheek was flushed and feverish, and his fine blue eyes were unnaturally bright with the disease which was sapping his vital energy. An old man undoubtedly, in spite of his large frame and finely moulded chest, which, though hollow and wasted, showed signs of a powerful physique at some remote period. His forehead was high and broad and powerful; his features finely chiselled; but the mouth, though benevolent-looking, was shifty and uneasy. He looked like a kind man and a good friend; but his face was haunted by a constant fear. With a pencil, he was engaged in tracing some characters on a sheet of paper; and ever and anon, at the slightest movement, even the trembling of a leaf, he looked up in agitation. The task was no light one, for his hand trembled, and his breath came and went with what was to him a violent exertion. Slowly and painfully the work went on; and as it approached completion, a smile of satisfaction shot across his sensitive mouth, at the same time a look of remorseful sorrow filled his whole face. It was only a few words on a piece of paper he was writing, but he seemed to realise the importance of his work. It was only a farewell letter; but in these few valedictory lines the happiness of two young lives were bound up. At last the task was finished, and he lay back with an air of great content.

At that moment, a woman entered the room. The sick man hid the paper hastily beneath the pillow with a look of fear on his face, pitiable to see. But the woman who entered did not look capable of inspiring any such sentiment. She was young and pretty, a trifle vain, perhaps, of her good looks and attractive appearance, but the model of what a 'neat-handed Phillis' should be.

Directly the dying man saw her, his expression changed to one of intense eagerness. Beckoning her to come close to him, he drew her head close to his face and said: 'She is not about, is she? Do you think she can hear what I am saying? Sometimes I fancy she hears my very thoughts.'

'No, sir,' replied the maid. 'Miss Wakefield is not in the house just now; she has gone into the village.'

'Very good. Listen, and answer me truly. Do you ever hear from—from Nelly now? Poor child, poor child!'

The woman's face changed from one of interest to that of shame and remorse. She looked into the old man's face, and then burst into a fit of hot passionate tears.

'Hush, hush!' he cried, terrified by her vehemence. 'For God's sake, stop, or it will be too late, too late!'

'O sir, I must tell you,' sobbed the contrite woman, burying her face in the bedclothes. 'Letters came from Miss Nelly to you, time after time; but I destroyed them all.'

'Why?' The voice was stern, and the girl looked up affrighted.

'O sir, forgive me. Surely you know. Is it possible to get an order from Miss Wakefield, and not obey? Indeed, I have tried to speak, but I was afraid to do anything. Even you, sir——'

'Ah,' said the invalid, with a sigh of ineffable sadness, 'I know how hard it is. The influence she has over one is wonderful, wonderful. But I am forgetting. Margaret Boulton, look me in the face. Do you love Miss Nelly as you used to do, and would you do something for her if I asked you?'

'God be my witness, I would, sir,' replied the girl solemnly.

'Do you know where she is?'

'Alas, no. It is a year since we heard.—But master, if you ask me to give her a letter or a paper, I will do so, if I have to beg my way to London to find her. I have been punished for not speaking out before. Indeed, indeed, sir, you may trust me.'

He looked into her face with a deep unfathomable glance for some moments; but the girl returned his gaze as steadily.

'I think I can,' he said at length. 'Now, repeat after me: "I swear that the paper intrusted to my care shall be delivered to the person for whom it is intended; and that I will never part with it until it is safely and securely delivered."'

The woman repeated the words with simple solemnity.

'Now,' he said, at the same time producing the paper he had written with such pain and care, 'I deliver this into your hands, and may heaven bless and prosper your undertaking. Take great care, for it contains a precious secret, and never part with it while life remains.'

The paper was a curious-looking document enough, folded small, but bearing nothing outside to betray the secret it contained. We shall see in the future how it fared.

The girl glanced at the folded paper, and thrust it rapidly in her bosom. A smile of peace and tranquility passed over the dying man's face, and he gave her a look of intense gratitude. At this moment another woman entered the room. She was tall and thin, with a face of grave determination, and a mouth and chin denoting a firmness amounting to cruelty. There was a dangerous light in her basilisk eyes at this moment, as she gave the servant a glance of intense hate and malice—a look which seemed to search out the bottom of her soul.

'Margaret, what are you doing here? Leave the room a once. How often have I told you never to come in here.'

Margaret left; and the woman with the snaky eyes busied herself silently about the sick-room. The dying man watched her in a dazed fascinated manner, as a bird turns to watch the motions of a serpent; and he shivered as he noticed the feline way in which she moistened her thin lips. He tried to turn his eyes away, but failed. Then, as if conscious of his feelings, the woman said: 'Well, do you hate me worse than usual to-day?'

'You know I never hated you, Selina,' he replied wearily.

'Yes you do,' she answered, with a sullen glowering triumph in her eyes. 'You do hate me for the influence I have over you. You hate me because you dare not hate me. You hate me because I parted you from your beggar's brat, and trained you to behave as a man should.'

Perfectly cowed, he watched her moistening her thin lips, till his eyes could no longer see. Presently he felt a change creeping over him; his breath came shorter and shorter; and his chest heaved spasmodically. With one last effort he raised himself up in his bed. 'Selina,' he said painfully, 'let me alone; oh, let me alone!'

'Too late,' she replied, not caring to disguise her triumphant tone.

He lay back with the dews of death clustering on his forehead. Suddenly, out of the gathering darkness grew perfect dazzling light; his lips moved; the words 'Nelly forgive!' were audible like a whispered sigh. He was dead.

The dark woman bent over him, placing her ear to his heart; but no sound came. 'Mine!' she said—'mine, mine! At last, all mine!'

The thin webs of fate's weaving were in her hands securely—all save one. It was not worth the holding, so it floated down life's stream, gathering as it went.

Mr Carver of Bedford Row, in the county of Middlesex, was exercised in his mind; and the most annoying part of it was that he was so exercised at his own trouble and expense; that is to say, he was not elucidating some knotty legal point at the charge of a client, but he was speculating over one of the most extraordinary events that had ever happened to him in the whole course of his long and honorable career. The matter stood briefly thus: His client, Charles Morton, of Eastwood, Somersetshire, died on the 9th of April in the year of grace 1882. On the 1st of May, 1880, Mr Carver had made the gentleman's will, which left all his possessions, to the amount of some forty thousand pounds, to his niece, Eleanor Attewood. Six months later, Mr Morton's half-sister, Miss Wakefield, took up her residence at Eastwood, and from that time everything had changed. Eleanor had married the son of a clergyman in the neighborhood, and at the instigation of his half-sister, Mr Morton had disinherited his niece; and one year before he died, had made a fresh will, leaving everything to Miss Wakefield. Mr Carver, be it remarked, strongly objected to this injustice, seeing the baneful influence which had brought it about; and had he been able to find Eleanor, he hoped to alter the unjust state of things. But she disappeared with her husband, and left no trace behind; so the obnoxious will was proved.

Then came the most extraordinary part of the affair. With the exception of a few hundreds in the bank at Eastwood, for household purposes, not a single penny of Mr Morton's money could be found. All his property was mortgaged to a high amount; all his securities were disposed of, and not one penny could be traced. The mortgages on the property were properly drawn up by a highly respectable solicitor at Eastwood, the money advanced by a man of undoubted probity; and, further, the money had been paid over to Mr Morton one day early in the year 1882. Advertisements were inserted in the papers, in fact everything was done to trace the missing money, but in vain. All Miss Wakefield had for her pains and trouble was a poor sum of about eleven hundred pounds, so she had to retire again to her genteel poverty in a cheap London boarding-house.

This melancholy fact did not give Mr Carver any particular sorrow; he disliked that lady, and was especially glad that her deep cunning and underhand ways had frustrated themselves. In all probability, he thought, Mr Morton had in a fit of suspicion got hold of all his ready cash and securities, for the purpose of balking the fair lady whom he had made his heiress; but nevertheless the affair was puzzling, and Mr Carver hated to be puzzled.

Mr Carver stood at his office in Bedford Row, drumming his fingers on the grimy window-panes and softly whistling. Nothing was heard in the office but the scratch of the confidential clerk's quill pen as he scribbled out a draft for his employer's inspection.

'This is a very queer case, Bates, very queer,' said Mr Carver, addressing his clerk.

'Yes, sir,' replied Mr Bates, continuing the scratching. That gentleman possessed the instinct of always being able to divine what his chief was thinking of. Therefore, when Mr Bates said 'Yes, sir,' he knew that the Eastwood mystery had been alluded to.

'I'd most cheerfully give—let me see, what would I give? Well, I wouldn't mind paying down my cheque for'——

'One thousand pounds, sir. No, sir; I don't think you would.'

'You're a wonderful fellow, Bates,' said his admiring master. ''Pon my honor, Bates, that's the exact sum I was going to mention.'

'It is strange, sir,' said the imperturbable Bates, 'that you and I always think the same things. I suppose it is being with you so long. Now, if I was to think you would give me a partnership, perhaps you would think the same thing too.'

'Bates,' said Mr Carver earnestly, never smiling, as was his wont, at his clerk's quiet badinage, 'if we unravel this mystery, as I hope we may, I'll tell you what, Bates, don't be surprised if I give you a partnership.'

''Ah, sir, if we unravel it. Now, if we could only find'——

'Miss Eleanor. Just what I was thinking.'

At this moment a grimy clerk put his head in at the door.

'Please, sir, a young person of the name of Seaton.'

'It is Miss Eleanor, by Jove!' said Bates, actually excited.

'Wonderful!' said Mr Carver.

In a few seconds the lady was ushered into the presence of Mr Carver. She was tall and fair, with a style of beauty uncommon to the people of to-day. Clad from head to foot in plain black, hat, jacket, and dress cut with a simplicity almost severe, and relieved only by a white collar at the throat, there was something in her air and bearing which spoke of a culture and breeding not easily defined in words, but nevertheless unmistakable. It was a face and figure that men would look at and turn again to watch, even in the busy street. Her complexion was almost painfully perfect in its clear pallid whiteness, and the large dark lustrous eyes shone out from the marble face with dazzling brightness. She had a perfect abundance of real golden hair, looped up in a great knot behind; but the rebellious straying tresses fell over her broad low forehead like an aureole round the head of a saint.

'Don't you know me, Mr Carver?' she said at length.

'My dear Eleanor, my dear Eleanor, do sit down!' This was the person whom he had been longing for two years to see, and Mr Carver, cool as he was, was rather knocked off his balance for a moment.

'Poor child! Why, why didn't you come and see me before?'

'Pride, Mr Carver—pride,' she replied, with a painful air of assumed playfulness.

'But surely pride did not prevent your coming to see your old friend?'

'Indeed, it did, Mr Carver. You would not have me part with one of my few possessions?'

'Nonsense, nonsense!' said the lawyer, with assumed severity. 'Now, sit down there, and tell me everything you have done for the last two years.'

'It is soon told. When my uncle—poor deluded man—turned me, as he did, out of his house on account of my marriage, something had to be done; so we came to London. For two years my husband has been trying to earn a living by literature. Far better had he stayed in the country and taken to breaking stones or working in the fields. It is a bitter life, Mr Carver. The man who wants to achieve fortune that way must have a stout heart; he must be devoid of pride and callous to failure. If I had all the eloquence of a Dickens at my tongue's end, I could not sum up two years' degradation and bitter miserable poverty and disappointment better than in the few words, "Trying to live by literature,"—However, it is useless to struggle against it any longer. Mr Carver, sorely against my inclination, I have come to you to help us.'

'My dear child, you hurt me,' said Mr Carver huskily, 'you hurt me; you do indeed. For two years I have been searching for you everywhere. You have only to ask me, and you know anything I can I will do.'

'God bless you,' replied Eleanor, with the gathering tears thick in her eyes. 'I know you will. I knew that when I came here. How can I thank you?'

'Don't do anything of the sort; I don't want any thanks. But before you go, I will do something for you. Now, listen to me. Before your uncle died'——

'Died! Is he dead?'

'How stupid of me. I didn't know'——

Mr Carver stopped abruptly, and paused till the natural emotions called forth in the young lady's mind had had time to expend themselves. She then asked when the event had happened.

'Two years ago,' said Mr Carver. 'And now, tell me—since you last saw him, had you any word or communication from him in any shape or form? Any letter or message?'

Eleanor shook her head, half sadly, half scornfully.

'You don't seem to know Miss Wakefield,' she said. 'No message was likely to reach me, while she remained at Eastwood.'

'No; I suppose not. So you have heard nothing? Very good. Now, a most wonderful thing has happened. When your uncle died and his will came to be read, he had left everything to Miss Wakefield. No reason to tell you that, I suppose? Now comes the strangest part of the story. With the exception of a few hundreds in the local bank, not a penny can be found. All the property has been mortgaged to the uttermost farthing; all the stock is sold out; and, in fact, nothing is left but Eastwood, which, as you know, is a small place, and not worth much. We have been searching for two years, and not a trace can we find.'

'Perhaps Miss Wakefield is hiding the plunder away,' Eleanor suggested with some indifference.

'Impossible,' eagerly exclaimed Mr Carver—'impossible. What object could she have in doing so? The money was clearly left to her; and it is not likely that a woman so fond of show would deliberately choose to spend her life in a dingy lodging-house.'

'And Eastwood?'

'Is empty. It will not let, neither can we sell it.'

'So Miss Wakefield is no better off than she was four years ago!' Eleanor said calmly. 'Come, Mr Carver, that is good news, at any rate. It almost reconciles me to my position.'

'Nelly, I wish you would not speak so,' said Mr Carver seriously. 'It hurts me. You were not so hard at one time.'

'Forgive me, my dear old friend,' she replied simply. 'Only consider what a life we have been living for the past two years, and you will understand.'

'And your husband?'

'Killing himself,' she said; 'wearing out body and soul in one long struggle for existence. It hurts me to see him. Always hoping, and always working, always smiling and cheerful before me; and ever the best of men and husband. Dear friend, if you knew what he is to me, and saw him as I do day after day, literally wearing out, you would consider my hardness pardonable. I am rebellious, you know.''

'No, no,' said Mr Carver, a suspicious gleam behind his spectacles; 'I can understand it. The only thing I blame you for is that you did not come to me before. You know what a lonely old bachelor I am, and—how rich I am. It would have been a positive kindness of you to come and see me.—Now, listen. On Sunday, you and your husband must come and dine with me. You know the old Russell Square address?'

'God bless you for a true friend!' said Eleanor, her tears flowing freely now. 'We will come; and I may bring my little girl with me?'

'Eh, what?' replied the lawyer—'little girl? Of course, of course! Then we will talk over old times, and see what can be done to make those cheeks look a little like they used to do.—So you have got a little girl, have you? Dear, dear, how the time goes!—Now, tell me candidly, do you want any assistance—any, ah—that is—a little—in short, money?'

Eleanor colored to the roots of her hair, and was about to reply hastily, but said nothing.

'Yes, yes,' said Mr Carver rapidly.—'I think, Bates'——

But Mr Bates already had his hand on the cheque-book, and commenced to fill in the date. Mr Carver gave him a look of approbation, and flashed him a sign with his fingers signifying the amount.

'I suppose you have some friends?' he continued hastily, to cover Eleanor's confusion. 'It's a poor world that won't stand one good friend.'

'Yes, we have one,' replied Eleanor, her face lighting up with a tender glow—'a good friend. You have heard of Jasper Felix the author? He is far the best friend we have.'

'Heard of Felix! I should think I have. Read every one of his books. I am glad to hear of his befriending you. I knew the man who writes as he does must have a noble heart.'

'He has. What we should have done without his assistance, I shudder to contemplate. I honestly believe that not one of my husband's literary efforts would have been accepted, had it not been for him.'

'I can't help thinking, Nelly, that there is a providence in these things, and I feel that better days are in store for you. Anyway, it won't be my fault if it is not so. I have a presentiment that things will come out all right in the end, and I fancy that your uncle's fortune his hidden away somewhere; and if it is hidden away, it must be, I cannot help thinking, for your benefit.'

'Don't count upon it, Mr Carver,' said Eleanor calmly. 'I look upon the money as gone.'

'Nonsense!' said the gentleman cheerfully; 'while there is life there is hope. I begin to feel that I am playing a leading character in a romance; I do, indeed! Firstly, your uncle dies, and his fortune is lost; secondly, you disappear; and at the very moment I am longing—literally longing—to see you, you turn up. Now, all that remains is to find the hidden treasure, and to be happy ever afterwards, like the people in a fairy tale.'

'Always enthusiastic,' laughed Eleanor. 'All we have to do is to discover a mystic clue to a buried chest of diamonds, only we lack the clue.'

''Pon my word, my dear, do you know I really think you have hit it?' replied Mr Carver with great solemnity. 'Now, at the time you left Eastwood, your companion Margaret was in the house; and after your uncle's death, she disappeared. From a little hint Miss Wakefield dropped to me, your old friend was in the sick-room alone with your uncle the day he died.'

'Alone? and then disappeared,' said Eleanor, all trace of apathy gone, and her eyes shining with interest.

'Alone. Now, if we could only find Margaret Boulton'——

Eleanor rose from her seat, and approached Mr Carver slowly. Then she said calmly: 'There is no difficulty about that; she is at my house now. I found her only last night on Waterloo Bridge—in fact, I saved her.'

'Saved her? Didn't I say there was a providence in it? Saved her?'

'From suicide!'

A quarter of an hour later, Eleanor was standing outside Mr Carver's office, evidently seeking a companion. From the bright flush on her face and the sparkle in her eyes, hope—and a strong hope—had revived. She stood there, quite unconscious of the admiration of passers-by, sweeping the street in search of her quest. Presently the object she was seeking came in view. He was a tall man, of slight figure, with blue eyes deeply sunk in a face far from handsome, but full of intellectual power and great character; a heavy, carelessly trimmed moustache hid a sensitive mouth, but did not disguise a bright smile. That face and figure was a famous one in London, and people there turned in the busy street to watch Jasper Felix, and admire his rugged powerful face and gaunt figure. He came swinging down the street now with firm elastic step, and treated Eleanor to one of his brightest smiles.

'Did you think I had forgotten you?' he said. 'I have been prowling about Gray's Inn Road, for, sooth to say, the air of Bedford Row does not agree with me.'

'I hope I have not detained you,' said Eleanor timidly; 'I know how valuable your time is to you.'

'My dear child, don't mention it,' replied the great novelist lightly; 'my time has been well occupied. First, I have been watching a fight between two paviors. Do you know it is quite extraordinary how those powerful men can knock each other about without doing much harm. Then I have been having a long chat with an intellectual chimney-sweep—a clever man, but a great Radical. I have spent quite an enjoyable half-hour.'

'A half-hour! Have I been so long? Mr Felix, I am quite horrified at having taken up so much of your time.'

'Awful, isn't it,' he laughed lightly. 'Well, you won't detain me much longer, for here you are close at home.—Now, I will just run into Fleet Street on my own business, and try and sell this little paper of your husband's at the same time. I'll call in this afternoon; only, mind, you must look as happy as you do now.'

Jasper Felix made his way through a court into Holborn, and along that busy thoroughfare till he turned down Chancery Lane. Crossing the street by the famous Griffin, he disappeared in one of the interminable courts leading out of Samuel Johnson's favorite promenade, Fleet Street. The object of his journey was here. On the door-plate was the inscription, 'The Midas Magazine,' and beneath the legend, 'First Floor.'.. Ascending the dingy stair, he stopped opposite a door on which, in white letters, was written the word 'Editor.' At this door he knocked. Without pausing for a reply, he pushed open the door.

'How, de do, Simpson?' said Mr Felix, with a look of amusement in his blue eyes.

'Glad to see you, Felix,' said the editor of the Midas cordially. 'I thought you had forgotten us. I hope you have something for our journal in your pocket.'

'I have something in my pocket to show you,' answered Felix, 'and I think you will appreciate it.'

'Is it something of your own?' queried the man of letters.

'No, it is not; and, what is more, I doubt if I could write anything so good myself. I know when you have seen it, you will accept it.'

'Um! I don't know,' replied the editor dubiously. 'You see, I am simply inundated with amateur efforts. Of course, sometimes I get something good; but usually——Now, if the matter in discussion was a manuscript of your own——'

'Now, seriously, Simpson, what do you care for me or anything of mine? It is the name you want, not the work. You know well enough what sells magazines of the Midas type. It is not so much the literary matter as the name. The announcement that the next month's Midas will contain the opening chapters of a new serial by someone with a name, is quite sufficient to increase your circulation by hundreds.'

''Pon my honor, you're very candid,' rejoined Mr Simpson. 'But what is this wonderful production you have?'

'Well, I'll leave it with you. You need not trouble to read it, because, if you don't take it, I know who will.'

'What do you want for this triumph of genius?'

'Well, in a word, ten pounds. Take it or leave it.'

'If you say it is worth it, I suppose I must oblige you.'

'That is a good way of putting it; and it will oblige me. But mark me—this man will some day confer favors by writing for you, instead of, as you regard it at present, favoring him.'

The proprietor of the Midas sighed gently. The idea of paying over ten pounds to an unknown contributor was not nice; but the fact of offending Felix was worse.

'If,' said he, harping on the old string, and shaking his head with a gentle deprecating motion—'if it was one of yours now'——

'What confounded nonsense you talk!' exclaimed Felix impatiently.

'Don't get wild, Felix,' replied Mr Simpson soothingly. 'I will take your protege's offering, to oblige you.'

'But I don't want you to oblige me. I want you to accept—and pay for—an article good enough for anything. It is a fair transaction; and if there is any favor about it, then it certainly is not on your side.'

Mr Simpson showed his white teeth in a dazzling smile. 'Well, Felix, I do admire your assurance,' he said softly. 'I never heard the matter put in that light before. My contributors, as a rule, don't point their manuscript at my head metaphorically, and demand speedy insertion and prompt pay.—Do you want a cheque for this manuscript now?'

'Yes, you may as well give me the cash now.'

Mr Simpson drew a cheque for the desired amount, and passed it over to Felix, who folded the pink slip, and placed it in his pocket; whereupon the conversation drifted into other channels.

Queen Square, Bloomsbury, is a neighbourhood which by no means accords with the expectation evoked by its high-sounding patronymic. It is, besides, somewhat difficult to to find, and when discovered, it has a guilty-looking air of having been playing hide-and-seek with its most aristocratic neighbors, Russell and Bloomsbury, and lost itself. Before Southampton Row was the stately thoroughfare it is now, Queen Square must have been a parasite of Russell Square; but in time it seems to have been built out. You stumble upon it suddenly, in making a short-cut from Southampton Row to Bedford Row, and wonder how it got there. It is quiet, decayed—in a word, shabby-genteel—and cheap.

On the south side, sheltered by two sad-looking trees of a nondescript character, and fronted by an imposing-looking portico, is a decayed-looking house, the stucco of which bears strong likeness to the outside of Stilton cheese. The windows are none too clean, and the blinds and curtains are all deeply tinged with London fog and London smoke. For the information of the metropolis at large, the door bears a tarnished brass plate announcing that it is the habitation of Mrs Whipple; and furthermore—from the same source—the inquiring mind is further enlightened with the fact that Mrs Whipple is a dressmaker. A few fly-blown prints of fashions, of a startling description and impossible colour, support this fact; and information is further added by the announcement that the artiste within lets apartments; for the legend is inscribed, in runaway letters, on the back of an old showcard which is suspended in one of the ground-floor windows.

From the general tout ensemble of the Whipple mansion, the most casual-minded individual on lodgings bent can easily judge of its cheapness. The 'ground-floor'—be it whispered in the strictest confidence—pays twenty-five shillings per week; the honoured 'drawing-rooms,' two pounds; and the slighted 'second-floors,' what the estimable Whipple denominates 'a matter of fifteen shillings.' It is with the second-floors that our business lies.

The room was large, and furnished with an eye to economy. The carpet was of no particular pattern, having long since been worn down to the thread; and the household goods consisted of five chairs and a couch covered by that peculiar-looking horsehair, which might, from its hardness and capacity for wear, be woven steel. A misty-looking glass, in a maple frame, and a chimney-board decked with two blue-and-green shepherdesses of an impossible period, completed the garniture. In the centre of the room was a round oak table with spidery uncertain legs, and at the table sat a young man writing. He was young, apparently not more than thirty, but the unmistakable shadow of care lay on his face. His dress was suggestive of one who had been somewhat dandyish in time gone by, but who had latterly ceased to trouble about appearances or neatness. For a time he continued steadily at his work, watched intently by a little child who sat coiled up in the hard-looking armchair, and waiting with exemplary patience for the worker to quit his employment. As he worked on, the child became visibly interested as the page approached completion, and at last, with a weary sigh, he finished, pushed his work from him, and turned with a bright smile to the patient little one.

'You've been a very good little girl, Nelly.—Now, what is it you have so particularly to say to me?' he said.

'Is it a tale you are writing, papa?' she asked.

'Yes, darling; but not the sort of tale to interest you.'

'I like all your tales, papa. Uncle Jasper told mamma they were all so "liginal." I like liginal tales.'

'I suppose you mean original, darling?'

'I said liginal,' persisted the little one, with childish gravity. 'Are you going to sell that one, papa? I hope you will; I want a new dolly so badly. My old dolly is getting quite shabby.'

'Some day you shall have plenty.'

The child looked up in his face solemnly. 'Really, papa? But do you know, pa, that some day seems such a long way off? How old am I, papa?'

'Very, very old, Nelly,' he replied with a little laugh. 'Not quite so old as I am, but very old.'

'Yes, papa? Then do you know, ever since I can remember, that some day has been coming. Will it come this week?'

'I don't know, darling. It may come any time. It may come to-day; perhaps it is on the way now.'

'I don't know, papa,' replied the little one, shaking her head solemnly. 'It is an awful while coming. I prayed so hard last night for it to come, after mamma put me in bed. What makes mamma cry when she puts me to bed? Is she crying for some day?'

'Oh, that's all your fancy, little one,' replied the father huskily. 'Mamma does not cry. You must be mistaken.

'No, indeed, papa; I'se not mistook. One day I heard mamma sing about some day, and then she cried—she made my face quite wet.'

'Hush, Nelly; don't talk like that, darling.'

'But she did,' persisted the little one. 'Do you ever cry, papa?'

'Look at that little sparrow, Nelly. Does he not look hungry, poor little fellow? He wants to come in the room to you.'

'I dess he's waiting for some day papa,' said the child, looking out at the dingy London sparrow perched on the window ledge. 'He looks so patient. I wonder if he's hungry? I am, papa.'

The father looked at his little one with passionate tenderness. 'Wait till mamma comes, my darling.'

'All right, papa; but I am so hungry!—Oh, here is mamma. Doesn't she look nice, papa, and so happy?'

When Eleanor entered the dingy room, her husband could not fail to notice the flush of hope and happiness on her face. He looked at her with expectation in his eyes.

'Did you think mother was never coming, Nelly? and do you want your dinner, my child?'

'You do look nice, ma,' said the child admiringly. 'You look as if you had found some day.'

Eleanor looked inquiringly at her husband, for him to explain the little one's meaning.

'Nelly and I have been having a metaphysical discussion,' he said with playful gravity. 'We have been discussing the virtues of the future. She is wishing for that impossible some day that people always expect.'

'I don't think she will be disappointed,' said Mrs Seaton, with a fond little smile at her child. 'I believe I have found it.—Edgar, I have been to see Mr Carver.'

'I supposed it would have come to that. And he, I suppose, has been poisoned by the sorceress, and refused to see you?'

'O no,' said Eleanor playfully. 'We had quite a long chat—in fact, he asked us all to dinner on Sunday.'

'Wonderful! And he gave you a lot of good advice on the virtues of economy, and his blessing at parting.'

'No,' she said; 'he must have forgotten that: he gave me this envelope for you with his compliments and best wishes.'

Edgar Seaton took the proffered envelope listlessly, and opened it with careless fingers. But as soon as he saw the shape of the enclosure, his expression changed to one of eagerness. 'Why, it is a cheque?' he exclaimed excitedly.

'O no,' said his wife, laughingly; 'it is only the blessing.'

'Well, it is a blessing in disguise,' Seaton said, his voice trembling with emotion. 'It is a cheque for twenty-five pounds.—Nelly, God has been very good to us to-day.'

'Yes, dear,' said his wife simply, with tears in her eyes.

Little Nelly looked from one to the other in puzzled suspense, scarcely knowing whether to laugh or cry. Even her childish instinct discovered the gravity of the situation.

'Papa, has some day come? You look so happy.'

He caught her up in his arms and kissed her lovingly, and held her in one arm, while he passed the other round his wife. 'Yes, darling. Your prayer has been answered. Some day—God be thanked—has come at last.' For a moment no one spoke, for the hearts of husband and wife were full of quiet thankfulness. What a little it takes to make poor humanity happy, and fill up the cup of pleasure to the brim!

Round the merry dinner-table all was bright and cheerful, and it is no exaggeration to say the board groaned under the profuse spread. Eleanor lost no time in acquainting her husband with the strange story of her uncle's property, and Mr Carver's views on the subject—a view of the situation which he felt almost inclined to share after a little consideration. It was extremely likely, he thought, that Margaret Boulton would be able to throw some light on the subject; indeed the fact of her strange rescue from her self-imposed fate pointed almost to a providential interference. It was known that she had a long conversation with Mr Morton the day he died, a circumstance which seemed to have given Miss Wakefield great uneasiness; and her strange disappearance from Eastwood directly after the funeral gave some coloring to the fact.

Margaret Boulton had not risen that day owing to a severe cold caught by her exposure to the rain on the previous night; and Edgar and his wife decided, directly she did so, to question her upon the matter. It would be very strange if she could not give some clue.

'I think, Nelly, we had better take Felix into our confidence,' said Edgar, when the remains of dinner had disappeared in company with the grimy domestic. 'He will be sure to be of some assistance to us; and the more brains we have the better.'

'Certainly, dear,' she acquiesced; 'he should know at once.'

'I think I will walk to his rooms this afternoon.'

'No occasion,' said a cheerful voice at that moment. 'Mr Felix is here very much at your service. I've got some good news for you; and I am sure, from your faces, you can return the compliment.'

Mr Felix was much struck by the tale he heard, and was inclined, in spite of the dictates of common-sense, to follow the Will-o'-the-wisp which grave Mr Carver had discovered. In a prosaic age, such a thing as the disappearance of a respectable Englishman's wealth was on the face of it startling enough; and therefore, although the thread was at present extremely intangible, he felt there must be something romantic about the matter. Mr Felix, be it remembered, was a man of sense; but he was a dreamer of dreams, and a weaver of romance by profession and choice; consequently, he was inclined to pooh-pooh Edgar's half-deprecating, half-enthusiastic view of the case.

'I do not think you are altogether right, Seaton, in treating this affair so cavalierly,' he said. 'In the first place, Miss Wakefield is no relation in blood to your wife's uncle. If the property was in her hands, I should feel myself justified in taking steps to have the existing will set aside; but so long as there is nothing worth doing battle for, it is not worth while, unless Miss Wakefield has the money, and is afraid of proceedings——'

'That is almost impossible,' Eleanor interrupted. 'You have really no conception how fond she is of show and display, and I know no such fear would prevent her indulging her fancy, if she had the means to do so.'

'So long as you are really persuaded that is the case, we have one difficulty out of the way,' Felix continued. 'Then we can take it for granted that she neither has the money nor has the slightest idea where it is.—Now, tell me about this Margaret Boulton.'

'That is soon told,' Eleanor replied. 'Last night, shortly after eleven, I was crossing Waterloo Bridge——'

'Bad neighborhood for a lady to be alone,' interrupted Felix, with a reproachful glance at Seaton.—'I beg your pardon. Go on, please.'

'I had missed my husband at Waterloo Station, and I was hurrying home as quickly as I could——'

'Why did you not take a cab?' exclaimed Felix with some asperity. Then seeing Eleanor color, he said hastily: 'What a dolt I am! I—I am very sorry. Please, go on.'

'As I was saying,' continued Eleanor, 'just as I was crossing the bridge, I saw a woman close by me climb on to one of the buttresses. I don't remember much about it, for it was over in less than a minute, and seems like a dream now; but it was my old nurse, or rather companion, Margaret Boulton, strange as it seems. Now, you know quite as much as I can tell you.'

Felix mused for a time over this strange history. He could not shake off the feeling that it was more than a mere coincidence. 'Seriously,' he said, 'I feel something will come of this.'

'I hope so,' answered Eleanor with a little sigh. 'Things certainly look a little better now than they did; but we need some permanent benefit sadly.'

'I thought some day had come, mamma,' piped little Nelly from her nest on the hearthrug.

'Little pitchers have long ears,' said the novelist. 'Come and sit on poor old Uncle Jasper's knee, Nelly, and give him a kiss.'

'Yes, I will, Uncle Jasper; but I'm not a little pitcher, and I've not dot long ears—Mamma, are my ears long?'

'No, darling,' replied her mother with a smile. 'Uncle Felix was not speaking of you.'

'Then I will sit upon his knee.' Whereupon she climbed up on to that lofty perch, and proceeded to draw invidious distinctions between Mr Felix' moustache and the hirsute appendage of her father, a mode of criticism which gave the good-natured literary celebrity huge delight.

'Now,' continued Felix, when he had placed the little lady entirely to her satisfaction—'now to resume. In the first place, I should particularly like to see this Margaret Boulton to-day.'

'I do not quite agree with you, Mr Felix. It would be cruel, with her nerves in such a state, to cross-examine her to-day,' Mrs Seaton said with womanly consideration. 'You can have no idea what such a reaction means.'

'Precisely,' said Felix grimly. 'Do you not see what I mean? Her nervous system is particularly highly strung at present—the brain in a state of violent activity, probably; and she is certain to be in a position to remember the minutest detail, and may give us an apparently trivial hint, which may turn out of the utmost importance.'

'Still, it seems the refinement of cruelty,' said Eleanor, her womanly kindness getting the better of her curiosity. 'She is in a particularly nervous state. Naturally, she is inclined to be morbidly religious, and the mere thought of her attempted crime last night upsets her.'

'Yes, perhaps so,' Felix said; 'but I should like to see her now. We cannot tell how important it may be to us.'

'I declare your enthusiasm is positively contagious,' laughed Seaton,—'Really, Felix, I did not imagine you were so deeply imbued with curiosity. My wife is bad enough, but you are positively girlish.'

'Indeed, sir, you belie me,' said Eleanor with mock-indignation. 'I am moved by a little natural inquisitiveness; but I shall certainly not permit that unfortunate girl to be annoyed for the purpose of gratifying the whim of two grown-up children.'

'Mea culpa,' Felix replied humbly. 'But I should like to see the interesting patient, if only for a few minutes.'

Eleanor laughed merrily at this persistent charge. 'Well, well,' she said, 'I will go up to Margaret and ascertain if she is fit to see any one just yet; but I warn you not to be disappointed, for she certainly shall not be further excited.'

'I do not think the curiosity is all on our side,' Felix said, as Eleanor was leaving the room.—'You are a fortunate man, Seaton, in spite of your troubles,' he continued. 'A wife like yours must make anxiety seem lighter.'

'Indeed, you are right,' Edgar answered earnestly. 'Many a time I have felt like giving it up, and should have done so, if it had not been for Eleanor.'

'Strange, too,' said Felix musingly, 'that she does not give one the impression of being so brave and courageous. But you never can tell. I have been making a study of humanity for twenty years, and I have been often disappointed in my models. I have seen the weakest do the work of the strongest. I have seen the strongest, on the other hand, go down before the first breath of trouble. I have seen the most acid of them all make the most angelic of wives.'

'I wonder you have never married, Felix.'

'Did I not tell you my model women have always been the first to disappoint me?' he replied lightly. 'Besides, what woman could know Jasper Felix and love him?'

'Your reputation alone——'

'Yes, my reputation—and my money,' Felix said bitterly. 'Twenty years ago, when I was plain Jasper Felix, I did——But bah! I don't want to discuss faded rose-leaves with you.—Let us change the subject. I have some good news for you. In the first place, I have sold the article you gave me.'

'Come, that is cheering. I suppose you managed to screw a guinea out of one of your friends for me?'

'On the contrary, I sold it on its merits,' Felix replied, 'and ten pounds the price.'

'Ten pounds! Am I dreaming, or am I a genius?'

'Neither; which is true, if not complimentary. There, is the cheque to prove you are not dreaming; and as to the other thing, you have no genius, but you have considerable talent.—But I have some further news for you. I have had a note from the editor of Mayfair, to whom I showed your work. Now, Baker of the Mayfair is about the finest judge of literary capacity I know. He says he was particularly struck with your descriptive writing; and if you like to undertake the work, he wants you to visit the principal of the foreign gambling clubs in London, and work up a series of gossiping articles for his paper. The work will not be particularly pleasant; but you will have the entree of all these clubs, and the golden key to get to the working part of the machinery. The thing will be hard and somewhat hazardous; but it is a grand opportunity of earning considerable kudos. Will you undertake it?'

'Undertake it!' said Seaton, springing to his feet. 'Will I not? Felix, you have made a new man of me. Had it not been for you, I don't know what would have become of us by this time. I cannot thank you in words, but you know that I feel your kindness.'

'I do not see how this should not lead to something like fortune; anyway, it means comfort and ease, if I do not mistake your capacity,' said Felix, totally ignoring the other's gratitude. 'If I were in your place, I should not tell my wife I was doing anything dangerous.'

'Poor child, how thankful she will be! But you are perfectly right as regards the danger—not that I fear it particularly, though there is no reason to make her anxious.'

'What mischief are you plotting?' said Eleanor, entering the room at that moment. 'You look on particularly good terms with yourselves.'

'Good news, Nelly, good news! I have actually got permanent work to do. You need not ask whose doing it is.'

'No, no,' said Felix modestly. 'It is your own capability you must thank.—What about the patient?'

'I really must ask you to postpone your inquiry for the present,' she replied; 'she is incapable of answering any questions just now. Indeed, I am so uneasy, that I have sent for a doctor.'

'Indeed! Well, I suppose we must wait for the present.—And now, I must tear myself away,' said Felix, as he rose and proceeded to button his overcoat.—'Seaton, you must hold yourself in readiness for your work at any moment.—No thanks, please,' as Eleanor was about to speak. 'Now, I must go.—Good-night, little Nelly; don't forget to think of poor old Uncle Jasper sometimes.'

'Good-night, Felix,' said Edgar with a hearty hand-shake. 'I won't thank you; but you know how I feel.—Good-night, dear old boy!'

'How do you feel now, Margaret?'

'Nearly over, Miss Nelly. I shall die with the morning.'

A week later and the patient had got gradually worse. The constant exposure, the hard life, and the weeks of semi-starvation, had told its tale on the weak womanly frame. The exposure in the rain and cold on that eventful night had hastened on the consumption which had long settled in the delicate chest. All signs of mental exhaustion had passed away, and the calm hopeful waiting frame of mind had succeeded. She was waiting for death; not with any feeling of terror, but with hopefulness and expectation.

Up to the present, Eleanor had not the heart to ask for any memento or rememberance of the old life; but had nursed her patient with an unceasing watchful care, which only a true woman is capable of. All that day she had sat beside the bed, never moving, but noting, as hour after hour passed steadily away, the gradual change from feverish restlessness to quiet content, never speaking, or causing her patient to speak, though she was longing for some word or sign. 'You have been very good to me, Miss Nelly. Had it not been for you, where should I have been now!'

'Hush, Margaret; don't speak like that. Remember, everything is forgiven now. Where there is great temptation, there is much forgiveness.'

'I hope so, miss—I hope so. Some day, we shall all know.'

'Don't try to talk too much.'

For a while she lay back, her face, with its bright hectic flush, marked out in painful contrast to the white pillow. Eleanor watched her with a look of infinite pity and tenderness. The distant hum of busy Holborn came with dull force into the room, and the heavy rain beat upon the windows like a mournful dirge. The little American clock on the mantel-shelf was the only sound, save the dry painful cough, which ever and anon proceeded from the dying woman's lips. The night sped on; the sullen roar of the distant traffic grew less and less; the wind dropped, and the girl's hard breathing could be heard painfully and distinctly. Presently, a change came over her face—a kind of bright, almost unearthly intelligence.

'Are you in any pain, Madge?' Eleanor asked with pitying air.

'How much lighter it is!' said the dying girl. 'My head is quite clear now, miss, and all the pain has gone.—Miss Nelly, I have been dreaming of the old home. Do you remember how we used to sit by the old fountain under the weeping-ash, and wonder what our fortunes would be? I little thought it would come to this.—Tell me, miss, are you in—in want?'

'Not exactly, Madge; but the struggle is hard sometimes.'

'I thought so,' the dying girl continued. 'I would have helped you after she came; but you know the power she had over your poor uncle, a power that increased daily. She used to frighten me. I tremble now when I think of her.'

'Don't think of her,' said Eleanor soothingly. 'Try and rest a little, and not talk. It cannot be good for you.'

The sufferer smiled painfully, and a terrible fit of coughing shook her frame. When she recovered, she continued: 'It is no use, Miss Nelly; all the rest and all your kind nursing cannot save me now. I used to wonder, when you left Eastwood so suddenly, why you did not take me; but now I know it is all for the best. Until the very last, I stayed in the house.'

'And did not my uncle give you any message, any letter for me?' asked Eleanor, with an eagerness she could not conceal.

'I am coming to that. The day he died, I was in his room, for she was away, and he asked me if I ever heard from you. I knew you had written letters to him which he never got; and so I told him. Then he gave me a paper for you, which he made me swear to deliver to you by my own hand; and I promised to find you. You know how I found you,' she continued brokenly, burying her face in her hands.

'Don't think of that now, Margaret,' said Eleanor, taking one wasted hand in her own. 'That is past and forgiven.'

'I hope so, miss. Please, bring me that dress, and I will discharge my trust before it is too late. Take a pair of scissors and unpick the seams inside the bosom on the left side.'

The speaker watched Eleanor with feverish impatience, whilst, with trembling fingers, she followed the instructions. Not until she had drawn out a flat parcel, wrapped securely in oiled paper, did the look of impatience transform to an air of relief.

'Yes, that is it,' said Margaret, as Eleanor tore off the covering. 'I have seen the letter, and have a strange feeling that it contains some secret, it is so vague and rambling, and those dotted lines across it are so strange. Your uncle was so terribly in earnest, that I cannot but think the paper has some hidden meaning. Please, read it to me. Perhaps I can make something of it.'

'It certainly does appear strange,' observed Eleanor, with suppressed excitement.

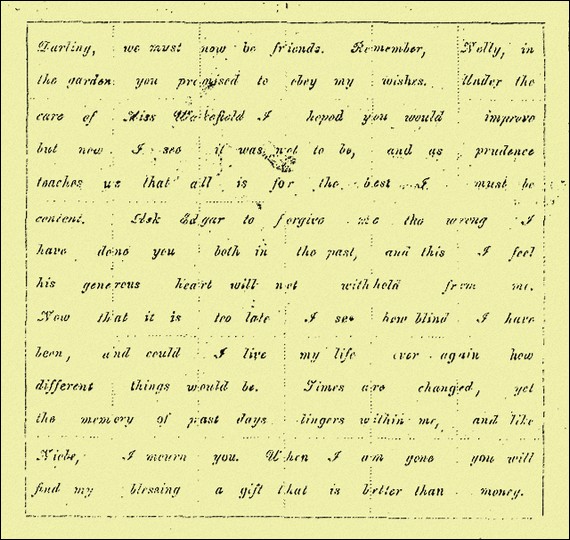

Turning towards the light, Eleanor read as follows:

Darling, we must now be friends. Remember, Nelly, in

the garden you promised to obey my wishes. Under the

care of Miss Wakefield I hoped you would improve

but now I see it was not to be, and as prudence

teaches us that all is for the best I must be

content. Ask Edgar to forgive me the wrong I

have done you both in the past, and this I feel

his generous heart will not withhold from me.

Now that it is too late, I see how blind I have

been, and could I live my life over again how

different things would be. Times are changed, yet

the memory of past days lingers within me, and like

Niobe, I mourn you. When I am gone you will

find my blessing a gift that is better than money.

The paper was half a sheet of ordinary foolscap, and the words were written without a single break or margin. It was divided perpendicularly by five dotted lines, and by four lines horizontally, and displayed nothing to the casual eye but an ordinary letter in a feeble handwriting.

The tiny threads of fate had begun to gather. All yet was dark and misty; but in the gloom, faint and transient, was one small ray of light.

Eleanor gazed at the paper abstractedly for a few moments, vaguely trying to find some hidden clue to the mystery.

'You must take care of that paper, Miss Nelly. Something tells me it contains a secret.'

'And have you been searching for me two long years, for the sole purpose of giving me this?' Eleanor asked.

'Yes, miss,' the sufferer replied simply. 'I promised you know. Indeed, I could not look at your uncle and break a vow like mine.'

'And you came to London on purpose?'

'Yes. No one knew where I was gone. I have no friends that I remember, and so I came to London. It is an old tale, miss. Trying day by day to get employment, and as regularly failing. I have tried many things the last two bitter years. I have existed—I cannot call it living—in the vilest parts of London, and tried to keep myself by my needle; but that only means dying by inches. God alone knows the struggle it is for a friendless woman here to keep honest and virtuous. The temptation is awful; and as I have been so sorely tried, I hope it will count in my favor hereafter. I have seen sights that the wealthy world knows nothing of. I have lived where a well-dressed man or woman dare not set foot. Oh, the wealth and the misery of this place they call London!'

'And you have suffered like this for me?' Eleanor said, the tears streaming down her face. 'You have gone through all this simply for my sake? Do you know, Madge, what a thoroughly good woman you really are?'

'I, miss?' the dying girl exclaimed in surprise. 'How can I possibly be that, when you know what you do of me! O no; I am a miserable sinner by the side of you. Do you think, Miss Nelly, I shall be forgiven?'

'I do not doubt it,' said, Eleanor softly; 'I cannot doubt it. How many in your situation could have withstood your temptation?'

'I am so glad you think so, miss; it is comfort to me to hear you say that. You were always so good to me,' she continued gratefully. 'Do you know, Miss Nelly dear, whenever I thought of death, I always pictured you as being by my side?'

'Do you feel any pain or restlessness now, Margaret?'

'No, Miss; thank you. I feel quite peaceful and contented. I have done my task, though it has been a hard one at times. I don't think I could have rested in my grave if I had not seen you.—Lift me up a little higher, please, and come a little closer. I can scarcely see you now. My eyes are quite misty. I wonder if all dying people think about their younger days, Miss Nelly? I do. I can see it all distinctly: the old broken fountain under the tree where we used to sit and talk about the days to come; and how happy we all were there before she came. Your uncle was a different man then, when he sat with us and listened to you singing hymns. Sing me one of the old hymns now, please.'

In a subdued key, Eleanor sang 'Abide with me,' the listener moving her pallid lips to the words. Presently, the singer finished, and the dying girl lay quiet for a moment.

'Abide with me. How sweet it sounds! "Swift to its close ebbs out life's little day." I am glad you chose my favorite hymn, Miss Nelly. I shall die repeating these words: "The darkness deepens; Lord, with me abide." Now it is darker still; but I can feel your hand in mine, and I am safe. I did not think death was so blessed and peaceful as this. I am going, going—floating away.'

'Margaret, speak to me!'

'Just one word more. How light it is getting! Is it morning? I can see. I think I am forgiven. I feel better, better! quite forgiven. Light, light, light! everywhere! I can see at last.'

It was all over. The weary aching heart was at rest. Only a woman, done to death in the flower of youth by starvation and exposure; but not before her task was done, her work accomplished. No lofty ambition to stir her pulses, no great goal to point to for its end. Only a woman, who had given her life to carry out a dying trust; only a woman, who had preserved virtue and honesty amid the direst temptation. What an epitaph for a gravestone! An eulogy that needs no glittering marble to point the way up to the Great White Throne.

Mr Carver sat in his private office a few days later, with Margaret's legacy before him. A hundred times he had turned the paper over. He had held it to the light; he had looked at it upside down, and he had looked at it sideways and longways; in fact, every way that his ingenuity could devise. He had even held it to the fire, in faint hopes of sympathetic ink; but his labor had met with no reward. The secret was not discovered.

The astute legal gentleman consulted his diary, where he had carefully noted down all the facts of the extraordinary case; and the more he studied the matter, the more convinced he became that there was a mystery concealed somewhere; and, moreover, that the key was in his hands, only, unfortunately, the key was a complicated one. Indeed, to such absurd lengths had he gone in the matter, that Edgar Allan Poe's romances of The Gold Bug and The Purloined Letter lay before him, and his study of those ingenious narratives had permeated his brain to such an extent lately, that he had begun to discover mystery in everything. The tales of the American genius convinced him that the solution was a simple one—provokingly simple, only, like all simple things, the hardest of attainment. He was quite aware of the methodical habits of his late client, Mr Morton, and felt that such a man could not have written such a letter, even on his dying bed, unless he had a powerful motive in so doing. Despite the uneasy consciousness that the affair was a ludicrous one to engage the attention of a sober business man like himself, he could not shake off the fascination which held him.

'Pretty sort of thing this for a man at my time of life to get mixed up in,' he muttered to himself. 'What would the profession say if they knew Richard Carver had taken to read detective romances in business hours? I shall find myself writing poetry some day, if I don't take care, and coming to the office in a billy-cock hat and turn-down collar. I feel like the heavy father in the transpontine drama; but when I look in that girl's eyes, I feel fit for any lunacy. Pshaw!—Bates!'

Mr Bates entered the apartment at his superior's bidding. 'Well, sir?' he said. The estimable Bates was a man of few words.

'I can not make this thing out,' exclaimed Mr Carver, rubbing his head in irritating perplexity. 'The more I look at it the worse it seems. Yet I am convinced——'

'That there is some mystery about it!'

'Precisely what I was going to remark. Now, Bates, we must—we really must—unravel this complication. I feel convinced that there is something hidden here. You must lend me your aid in the matter. There is a lot at stake. For instance, if——'

'We get it out properly, I get my partnership; if not, I shall have to—whistle for it, sir!'

'You are a very wonderful fellow, Bates—very. That is precisely what I was going to say,' Mr Carver exclaimed admiringly. 'Now, I have been reading a book—a standard work, I may say.'

'Williams's Executors, sir, or——?'

'No,' said Mr Carver shortly, and not without some confusion; 'it is not that admirable volume—it is, in fact, a—a romance.'

Mr Bates coughed dryly, but respectfully, behind his hand. 'I beg your pardon, sir; I don't quite understand. Do you mean you have been reading a—novel?'

'Well, not exactly,' replied Mr Carver blushing faintly. 'It is, as I have said, a romance—a romance,' he continued with an emphasis upon the substantive, to mark the difference between that and an ordinary work of fiction. 'It is a book treating upon hidden things, and explaining, in a light and pleasant way, the method of logically working out a problem by common-sense. Now, for instance, in the passage I have marked, an allusion is made, by way of example.—Did you ever—ha, ha! play at marbles, Bates?'

'Well, sir, many years ago, I might have indulged in that little amusement,' Mr Bates admitted with professional caution; 'but really, sir, it is such a long time ago, that I hardly remember.'

'Very good, Bates. Now, in the course of your experience upon the subject of marbles, do you ever remember placing a game called "Odd and Even?"'

Bates looked at his principal in utter amazement, and Mr Carver, catching the expression of his face, burst into a hearty laugh, faintly echoed by the bewildered clerk. The notion of two gray-headed men solemnly discussing a game of marbles in business hours, suddenly struck him as being particularly ludicrous.

'Well, sir,' Bates said with a look of relief, 'I don't remember the fascinating amusement you speak of, and I was wondering what it could possibly have to do with the case in point.'

'Well, I won't go into it now; but if you should like to read it for yourself, there it is,' said Mr Carver, pushing over the yellow-bound volume to his subordinate.

Mr Bates eyed the volume suspiciously, and touched it gingerly with his forefinger. 'As a matter of professional duty, sir, if you desire it, I will read the matter you refer to; but if it is a question of recreation, then, sir, with your permission, I would rather not.'

'That is a hint for me, I suppose. Bates,' said Mr Carver with much good-humor, 'not to occupy my time with frivolous literature.'

'Well, sir, I do not consider these the sort of books for a place on a solicitor's table; but I suppose you know best.'

'I don't think such a thing has happened before, Bates,' Mr Carver answered with humility. 'You see, this is an exceptional case, and I take great interest in the parties.'

'Well, there is something in that,' said Mr Bates severely, 'so I suppose we must admit it on this occasion.—But don't you think, sir, there is some way of getting to the bottom of this affair, without wasting valuable time on such as that?' and he pointed contemptuously at the book before him.

'Perhaps so, Bates—perhaps so. I think the best thing we can do is to consult an expert. Not a man who is versed in writings, but one of those clever gentlemen who make a study of ciphers. For all we know, there may be a common form of cipher in this paper.'

'That is my opinion, sir. Depend upon it, marbles have nothing to do with this mystery.'

'Mr Seaton wishes to see you, sir,' said a clerk at this moment.

'Indeed! Ask him to come in.—Good-morning, my dear sir,' as Seaton entered. 'We have just been discussing your little affair, Bates and I; but we can make nothing of it—positively nothing.'

'No; I suppose not,' Edgar replied lightly. 'I, for my part, cannot understand your making so much of a common scrap of paper. Depend upon it, the precious document is only an ordinary valedictory letter after all. Take my advice—throw it in the fire, and think no more about it.'

'Certainly not, sir,' Mr Carver replied indignantly. 'I don't for one moment believe it to be anything but an important cipher.—What are you smiling at?'

Edgar had caught sight of the yellow volumes on the table, and could not repress a smile. 'Have you read those tales?' he said.

'Yes, I have; and they are particularly interesting.'

'Then I won't say any more,' Edgar replied. 'When a man is fresh from these romances, he is incapable of regarding ordinary life for a time. But the disease cures itself. In the course of a month or so, you will begin to forget these complications, and probably burn that fatal paper.'

'I intend to do nothing of the sort; I am going to submit it to an expert this afternoon, and get his opinion.'

'Yes. And he will keep it for a fortnight, after having read it over once, and then you will get an elaborate report, covering some sheets of paper, stating that it is an ordinary letter. Who was the enemy who lent you Poe's works?'

'I read those books before you were born, young man; and I may tell you—apart from them—that I am fully convinced that there is a mystery somewhere. 'Pon my word, you take the matter very coolly, considering all things. But let us put aside the mystery for a time, and tell me something of yourself.'

'I am looking up now, thanks to you and Felix,' Edgar replied gratefully. 'I have an appointment at last.'

'I am sure I am heartily glad to hear it. What is it?'

'It was the doing of Felix, of course. The editor of Mayfair was rather taken by my descriptive style in a paper which Felix showed him, and made me an offer of doing the principal continental gambling-houses in London.'

'Um,' said Mr Carver doubtfully. 'And the pay?'

'Is particularly good, besides which, I have the entree of these places—the golden key, you know.'

'Have you told your wife about it?'

'Well, not altogether; she might imagine it was dangerous for me. She knows partly what I am doing; but I must not frighten her. I have had two nights of it, and apart from the excitement and the heat, it is certainly not dangerous.'

'I am glad of that,' said Mr Carver; 'and am heartily pleased to hear of your success—providing it lasts.'

'Oh, it is sure to last, for I have hundreds of places to go to. To-night I am going to a foreign place in Leicester Square. I go about midnight, and think I may generally be able to get home about two. I have to go alone always.'

'Well, I hope now you have started, you will continue as well,' Mr Carver said heartily; 'at any rate, you can continue until I unravel the mystery, and place you in possession of your fortune. Until then, it will do very well.'

'I am not going to count on that,' Edgar replied; 'and if it is a failure, I shall not be so disappointed as you, I fancy.'

It wanted a few minutes to eleven o'clock, the same night when Seaton turned into Long Acre on his peculiar business. A sharp walk soon brought him to the Alhambra, whence the people were pouring out into the square. Turning down——Street, he soon reached his destination—a long narrow house, in total darkness—a sombre contrast to the neighboring buildings, which were mostly a blaze of light, and busy with the occupations of life. A quiet double rap for some time produced no impression; and just as he had stood upon the door-step long enough to acquire considerable impatience, a sliding panel in the door was pushed back, and a face, in the dim gas-light, was obtruded. A short but somewhat enigmatical conversation ensued, at the end of which the door was grudgingly opened, and Edgar found himself in black darkness. The truculent attendant having barricaded the exit, gave a peculiar whistle, and immediately the light in the hall was turned up. It was a perfectly bare place; but the carpet underfoot was of the heaviest texture, and apparently—as an extra precaution—had been covered with india-rubber matting, so that the footsteps were perfectly deadened; indeed, not the slightest foot-fall could be heard. Following his guide in the direction of the rear of the house, and ascending a short flight of steps, Edgar was thrust unceremoniously into a dark room, the door of which was immediately closed behind him and locked. For a few seconds, Edgar stood quite at a loss to understand his position, till the peculiar whistle was again repeated, and immediately, as if by magic, the room was brilliantly lighted. When Edgar recovered from the glare, he looked curiously around. It was a large room, without windows, save a long skylight, and furnished with an evident aim at culture; but though the furniture was handsome, it was too gaudy to please a tasteful eye. The principal component parts consisted of glass gilt and crimson velvet; quite the sort of apartment that the boy-hero discovers, when he is led with dauntless mien and defiant eye into the presence of the Pirate king; and indeed some of the faces of the men seated around the green board would have done perfectly well for that bloodthirsty favorite of our juvenile fiction.

There were some thirty men in the room, two-thirds of them playing rouge-et-noir; nor did they cease their rapt attention to the game for one moment to survey the new-comer, that office being perfectly filled by the Argus-eyed proprietor, who was moving unceasingly about the room. 'Will you play, sare?' he said insinuatingly to Edgar, who was leisurely surveying the group and making little mental notes for his guidance.

'Thanks! Presently, when I have finished my cigar,' he replied.

'Ver good, sare, ver good. Will not m'sieu take some refreshment—a leetle champein or eau-di-vie?'

'Anything,' Edgar replied carelessly, as the polite proprietor proceeded to get the desired refreshment.

For a few minutes Edgar sat watching his incongruous companions, as he drank sparingly of the champagne before him. The gathering was of the usual run of such places, mostly foreigners, as befitted the neighborhood, and not particularly desirable foreigners at that. On the green table the stakes were apparently small, for Edgar could see nothing but silver, with here and there, a piece of gold. At a smaller table four men were playing the game called poker for small stakes; but what particularly interested Edgar was a young man deep in the fascination of ecarte with a man who to him was evidently a stranger. The younger man—quite a boy, in fact—was losing heavily, and the money on the table here was gold alone, with some bank-notes. Directly Edgar saw the older man, who was winning steadily, he knew him at once; only two nights before he had seen him in a gambling-house at the West End playing the same game, with the same result. Standing behind the winner was a sinister-looking scoundrel, backing the winner's luck with the unfortunate youngster, and occasionally winning a half-crown from a tall raw-looking American, who was apparently simple enough to risk his money on the loser. Attracted by some impulse he could not understand, Edgar quitted his seat and took his stand alongside the stranger, who was losing his money with such simple good-nature.

'Stranger, you have all the luck, and that's a fact. There goes another piece of my family plate. Your business is better 'n gold-mining, and I want you to believe it,' drawled the American, passing another half-crown across the table.

'You are a bit unlucky,' replied the stranger, with a flash of his white teeth; 'but your turn will come, particularly as the young gentleman is really the better player. I should back him myself, only I believe in a man's luck.'

'Wall, now, I shouldn't wonder if the younker is the best player,' the American replied, with an emphasis on the last word. 'So I fancy I shall give him another trial. He's a bit like a young hoss, he is—but he's honest.'

'You don't mean to insinuate we're not on the square, eh?' said the lucky player sullenly; 'because, if that is so——'

'Now, don't you get riled, don't,' said the American soothingly. 'I'm a peaceable individual, and apt to get easily frightened. I'm a-goin' to back the young un again.'