RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

RGL e-Book Cover 2016©

"The Crimson Blind," Ward Lock & Co, London, 1905

| I. Who Speaks? II. The Crimson Blind III. The Voice In The Darkness IV. In Extremis V. Received With Thanks VI. A Policy Of Silence VII. No. 218, Brunswick Square VIII. Hatherly Bell IX. The Broken Figure X. The House Of The Silent Sorrow XI. After Rembrandt XII. The Crimson Blind XIII. Good Dog! XIV. Behind The Blind XV. A Medical Opinion XVI. Margaret Sees A Ghost XVII. The Pace Slackens XVIII. A Common Enemy XIX. Rollo Shows His Teeth XX. Frank Littimer XXI. A Find XXII. The Light That Failed XXIII. Indiscretion XXIV. Enid Learns Something XXV. Littimer Castle XXVI. An Unexpected Guest XXVII. Slightly Farcical XXVIII. A Squire Of Dames XXIX. The Man With The Thumb Again |

XXX. Gone! XXXI. Bell Arrives XXXII. How The Scheme Worked Out XXXIII. The Frame Of The Picture XXXIV. The Puzzling Of Henson XXXV. Chris Has An Idea XXXVI. A Brilliant Idea XXXVII. Another Telephonic Message XXXVIII. A Little Fiction XXXIX. The Fascination Of James Merritt XL. A Useful Discovery XLI. A Delicate Errand XLII. Prince Rupert's Ring XLIII. Nearing The Truth XLIV. Enid Speaks XLV. On The Trail XLVI. Littimer's Eyes Are Opened XLVII. The Track Broadens XLVIII. Where Is Rawlins? XLIX. A Chevalier Of Fortune L. Rawlins Is Candid LI. Heritage Is Willing LII. Putting The Light Out LIII. Unsealed Lips LIV. Where Is The Ring? LV. Kicked Out LVI. White Fangs LVII. Hide-And-Seek Other Cover Images |

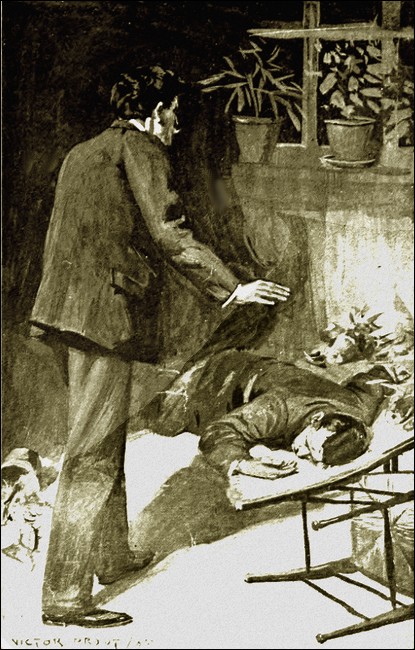

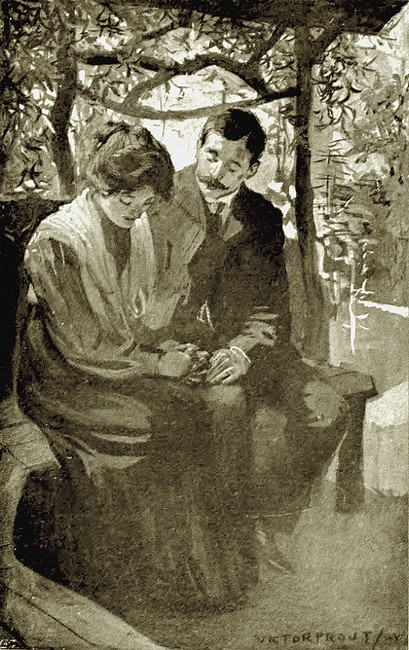

Frontispiece

Dead! Oh, yes, dead enough.

David Steel dropped his eyes from the mirror and shuddered as a man who sees his own soul bared for the first time. And yet the mirror was in itself a thing of artistic beauty—engraved Florentine glass in a frame of deep old Flemish oak. The novelist had purchased it in Bruges, and now it stood as a joy and a thing of beauty against the full red wall over the fireplace. And Steel had glanced at himself therein and seen murder in his eyes.

He dropped into a chair with a groan for his own helplessness. Men have done that kind of thing before when the cartridges are all gone and the bayonets are twisted and broken and the brown waves of the foe come snarling over the breastworks. And then they die doggedly with the stones in their hands, and cursing the tardy supports that brought this black shame upon them.

But Steel's was ruin of another kind. The man was a fighter to his finger-tips. He had dogged determination and splendid physical courage; he had gradually thrust his way into the front rank of living novelists, though the taste of poverty was still bitter in his mouth. And how good success was now that it had come!

People envied him. Well, that was all in the sweets of the victory. They praised his blue china, they lingered before his Oriental dishes and the choice pictures on the panelled walls. The whole thing was still a constant pleasure to Steel's artistic mind. The dark walls, the old oak and silver, the red shades, and the high artistic fittings soothed him and pleased him, and played upon his tender imagination. And behind there was a study, filled with books and engravings, and beyond that again a conservatory, filled with the choicest blossoms. Steel could work with the passion flowers above his head and the tender grace of the tropical ferns about him, and he could reach his left hand for his telephone and call Fleet Street to his ear.

It was all unique, delightful, the dream of an artistic soul realised. Three years before David Steel had worked in an attic at a bare deal table, and his mother had £3 per week to pay for everything. Usually there was balm in this recollection.

But not to-night, Heaven help him, not to-night! Little grinning demons were dancing on the oak cornices, there were mocking lights gleaming from Cellini tankards that Steel had given far too much money for. It had not seemed to matter just at the time. If all this artistic beauty had emptied Steel's purse there was a golden stream coming. What mattered it that the local tradesmen were getting a little restless? The great expense of the novelist's life was past. In two years he would be rich. And the pathos of the thing was not lessened by the fact that it was true. In two years' time Steel would be well off. He was terribly short of ready money, but he had just finished a serial story for which he was to be paid £500 within two months of the delivery of the copy; two novels of his were respectively in their fourth and fifth editions. But these novels of his he had more or less given away, and he ground his teeth as he thought of it. Still, everything spelt prosperity. If he lived, David Steel was bound to become a rich man.

And yet he was ruined. Within twenty-four hours everything would pass out of his hands. To all practical purposes it had done so already. And all for the want of £1,000! Steel had earned twice that amount during the past twelve months, and the fruits of his labour were as balm to his soul about him. Within the next twelve months he could pay the debt three times over. He would cheerfully have taken the bill and doubled the amount for six months' delay.

And all this because he had become surety for an absconding brother. Steel had put his pride in his pocket and interviewed his creditor, a little, polite, mild-eyed financier, who meant to have his money to the uttermost farthing. At first he had been suave and sympathetic, until he had discovered that Steel had debts elsewhere, and then—

Well, he had signed judgment, and to-morrow he could levy execution. Within a few hours the bottom would fall out of the universe so far as Steel was concerned. Within a few hours every butcher and baker and candle-stick-maker would come abusively for his bill. Steel, who could have faced a regiment, recoiled fearfully from that. Within a week his oak and silver would have to be sold and the passion flower would wither on the walls.

Steel had not told anybody yet; the strong man had grappled with his trouble alone. Had he been a man of business he might have found some way out of the difficulty. Even his mother didn't know. She was asleep upstairs, perhaps dreaming of her son's greatness. What would the dear old mater say when she knew? Well, she had been a good mother to him, and it had been a labour of love to furnish the house for her as for himself. Perhaps there would be a few tears in those gentle eyes, but no more. Thank God, no reproaches there.

David lighted a cigarette and paced restlessly round the dining-room. Never had he appreciated its quiet beauty more than he did now. There were flowers, blood-red flowers, on the table under the graceful electric stand that Steel had designed himself. He snapped off the light as if the sight pained him, and strode into his study. For a time he stood moodily gazing at his flowers and ferns. How every leaf there was pregnant with association. There was the Moorish clock droning the midnight hour. When Steel had brought that clock—

"Ting, ting, ting. Pring, pring, ping, pring. Ting, ting, ting, ting."

But Steel heard nothing. Everything seemed as silent as the grave. It was only by a kind of inner consciousness that he knew the hour to be midnight. Midnight meant the coming of the last day. After sunrise some greasy lounger pregnant of cheap tobacco would come in and assume that he represented the sheriff, bills would be hung like banners on the outward walls, and then.—

"Pring, pring, pring. Ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting, ting. Pring, pring, pring."

Bells, somewhere. Like the bells in the valley where the old vicarage used to stand. Steel vaguely wondered who now lived in the house where he was born. He was staring in the most absent way at his telephone, utterly unconscious of the shrill impatience of the little voice. He saw the quick pulsation of the striker and he came back to earth again.

Jefferies of the Weekly Messenger, of course. Jefferies was fond of a late chat on the telephone. Steel wondered grimly, if Jefferies would lend him £1,000. He flung himself down in a deep lounge-chair and placed the receiver to his ear. By the deep, hoarse clang of the wires, a long-distance message, assuredly.

"From London, evidently. Halloa, London! Are you there?"

London responded that it was. A clear, soft voice spoke at length.

"Is that you, Mr. Steel? Are you quite alone? Under the circumstances you are not busy to-night?"

Steel started. He had never heard the voice before. It was clear and soft and commanding, and yet there was just a suspicion of mocking irony in it.

"I'm not very busy to-night," Steel replied. "Who is speaking to me?"

"That for the present we need not go into," said the mocking voice. "As certain old-fashioned contemporaries of yours would say, 'We meet as strangers!' Stranger yet, you are quite alone!"

"I am quite alone. Indeed, I am the only one up in the house."

"Good. I have told the exchange people not to ring off till I have finished with you. One advantage of telephoning at this hour is that one is tolerably free from interruption. So your mother is asleep? Have you told her what is likely to happen to you before many hours have elapsed?"

Steel made no reply for a moment. He was restless and ill at ease to-night, and it seemed just possible that his imagination was playing him strange tricks. But, no. The Moorish clock in its frame of celebrities droned the quarter after twelve; the scent of the Dijon roses floated in from the conservatory.

"I have told nobody as yet," Steel said, hoarsely. "Who in the name of Heaven are you?"

"That in good time. But I did not think you were a coward."

"No man has ever told me so—face to face."

"Good again. I recognise the fighting ring in your voice. If you lack certain phases of moral courage, you are a man of pluck and resource. Now, somebody who is very dear to me is at present in Brighton, not very far from your own house. She is in dire need of assistance. You also are in dire need of assistance. We can be of mutual advantage to one another."

"What do you mean by that?" Steel whispered.

"Let me put the matter on a business footing. I want you to help my friend, and in return I will help you. Bear in mind that I am asking you to do nothing wrong. If you will promise me to go to a certain address in Brighton to-night and see my friend, I promise that before you sleep the sum of £1,000 in Bank of England notes shall be in your possession."

No reply came from Steel. He could not have spoken at that moment for the fee-simple of Golconda. He could only hang gasping to the telephone. Many a strange and weird plot came and went in that versatile brain, but never one more wild than this. Apparently no reply was expected, for the speaker resumed:—

"I am asking you to do no wrong. You may naturally desire to know why my friend does not come to you. That must remain my secret, our secret. We are trusting you because we know you to be a gentleman, but we have enemies who are ever on the watch. All you have to do is to go to a certain place and give a certain woman information. You are thinking that this is a strange mystery. Never was anything stranger dreamt of in your philosophy. Are you agreeable?"

The mocking tone died out of the small, clear voice until it was almost pleading.

"You have taken me at a disadvantage," Steel said. "And you know—"

"Everything. I am trying to save you from ruin. Fortune has played you into my hands. I am perfectly aware that if you were not on the verge of social extinction you would refuse my request. It is in your hands to decide. You know that Beckstein, your creditor, is absolutely merciless. He will get his money back and more besides. This is his idea of business. To-morrow you will be an outcast—for the time, at any rate. Your local creditors will be insolent to you; people will pity you or blame you, as their disposition lies. On the other hand, you have but to say the word and you are saved. You can go and see the Brighton representatives of Beckstein's lawyers, and pay them in paper of the Bank of England."

"If I was assured of your bona-fides," Steel murmured.

A queer little laugh, a laugh of triumph, came over the wires.

"I have anticipated that question. Have you Greenwich time about you?"

Steel responded that he had. It was five-and-twenty minutes past twelve. He had quite ceased to wonder at any questions put to him now. It was all so like one of his brilliant little extravanganzas.

"You can hang up your receiver for five minutes," the voice said. "Precisely at half-past twelve you go and look on your front doorstep. Then come back and tell me what you have found. You need not fear that I shall go away."

Steel hung up the receiver, feeling that he needed a little rest. His cigarette was actually scorching his left thumb and forefinger, but he was heedless of the fact. He flicked up the dining-room lights again and rapidly made himself a sparklet soda, which he added to a small whisky. He looked almost lovingly at the gleaming Cellini tankard, at the pools of light on the fair damask. Was it possible that he was not going to lose all this, after all?

The Moorish clock in the study droned the half-hour.

David gulped down his whisky and crept shakily to the front door with a feeling on him that he was doing something stealthily. The bolts and chain rattled under his trembling fingers. Outside, the whole world seemed to be sleeping. Under the wide canopy of stars some black object picked out with shining points lay on the white marble breadth of the top step. A gun-metal cigar-case set in tiny diamonds.

The novelist fastened the front door and staggered to the study. A pretty, artistic thing such as David had fully intended to purchase for himself. He had seen one exactly like it in a jeweller's window in North Street. He had pointed it out to his mother. Why, it was the very one! No doubt whatever about it! David had had the case in his hands and had reluctantly declined the purchase.

He pressed the spring, and the case lay open before him. Inside were papers, soft, crackling papers; the case was crammed with them. They were white and clean, and twenty-five of them in all. Twenty-five Bank of England notes for £10 each—£250!

David fought the dreamy feeling off and took down the telephone receiver.

"Are you there?" he whispered, as if fearful of listeners. "I—I have found your parcel."

"Containing the notes. So far so good. Yes, you are right, it is the same cigar-case you admired so much in Lockhart's the other day. Well, we have given you an instance of our bona-fides. But £250 is of no use to you at present. Beckstein's people would not accept it on account—they can make far more money by 'selling you up,' as the poetic phrase goes. It is in your hands to procure the other £750 before you sleep. You can take it as a gift, or, if you are too proud for that, you may regard it as a loan. In which case you can bestow the money on such charities as commend themselves to you. Now, are you going to place yourself entirely in my hands?"

Steel hesitated no longer. Under the circumstances few men would, as he had a definite assurance that there was nothing dishonourable to be done. A little courage, a little danger, perhaps, and he could hold up his head before the world; he could return to his desk to-morrow with the passion flowers over his head and the scent groves sweet to his nostrils. And the mater could dream happily, for there would be no sadness or sorrow in the morning.

"I will do exactly what you tell me," he said.

"Spoken like a man," the voice cried. "Nobody will know you have left the house—you can be home in an hour. You will not be missed. Come, time is getting short, and I have my risks as well as others. Go at once to Old Steine. Stand on the path close under the shadow of the statue of George IV. and wait there. Somebody will say 'Come,' and you will follow. Goodnight."

Steel would have said more, but the tinkle of his own bell told him that the stranger had rung off. He laid his cigar-case on the writing-table, slipped his cigarette-case into his pocket, satisfied himself that he had his latch-key, and put on a dark overcoat. Overhead the dear old mater was sleeping peacefully. He closed the front door carefully behind him and strode resolutely into the darkness.

David walked swiftly along, his mind in a perfect whirl. Now that once he had started he was eager to see the adventure through. It was strange, but stranger things had happened. More than one correspondent with queer personal experiences had taught him that. Nor was Steel in the least afraid. He was horribly frightened of disgrace or humiliation, but physical courage he had in a high degree. And was he not going to save his home and his good name?

David had not the least doubt on the latter score. Of course he would do nothing wrong, neither would he keep the money. This he preferred to regard as a loan—a loan to be paid off before long. At any rate, money or no money, he would have been sorry to have abandoned the adventure now.

His spirits rose as he walked along, a great weight had fallen from his shoulders. He smiled as he thought of his mother peacefully sleeping at home. What would his mother think if she knew? But, then, nobody was to know. That had been expressly settled in the bond.

Save for an occasional policeman the streets were deserted. It was a little cold and raw for the time of year, and a fog like a pink blanket was creeping in from the sea. Down in the Steine the big arc-lights gleamed here and there like nebulous blue globes; it was hardly possible to see across the road. In the half-shadow behind Steel the statue of the First Gentleman in Europe glowed gigantic, ghost-like in the mist.

It was marvellously still there, so still that David could hear the tinkle of the pebbles on the beach. He stood back by the gate of the gardens watching the play of the leaf silhouettes on the pavement, quaint patterns of fantastic designs thrown up in high relief by the arc-light above. From the dark foggy throat of St. James's Street came the tinkle of a cycle bell. On so still a night the noise seemed bizarre and out of place. Then the cycle loomed in sight; the rider, muffled and humped over the front wheel, might have been a man or a woman. As the cyclist flashed by something white and gleaming dropped into the road, and the single word "Come" seemed to cut like a knife through the fog. That was all; the rider had looked neither to the right nor to the left, but the word was distinctly uttered. At the same instant an arm dropped and a long finger pointed to the gleaming white square in the road. It was like an instantaneous photograph—a flash, and the figure had vanished in the fog.

"This grows interesting," Steel muttered. "Evidently my shadowy friend has dropped a book of rules in the road for me. The plot thickens."

It was only a plain white card that lay in the road. A few lines were typed on the back of it. The words might have been curt, but they were to the point:—

"Go along the sea front and turn into Brunswick Square. Walk along the right side of the square until you reach No. 219. You will read the number over the fanlight. Open the door and it will yield to you; there is no occasion to knock. The first door inside the hall leads to the dining-room. Walk into there and wait. Drop this card down the gutter just opposite you."

David read the directions once or twice carefully. He made a mental note of 219. After that he dropped the card down the drain-trap nearest at hand. A little way ahead of him he heard the cycle bell trilling as if in approval of his action. But David had made up his mind to observe every rule of the game. Besides, he might be rigidly watched.

The spirit of adventure was growing upon Steel now. He was no longer holding the solid result before his eyes. He was ready to see the thing through for its own sake. And as he hurried up North Street, along Western Road, and finally down Preston Street, he could hear the purring tinkle of the cycle bell before him. But not once did he catch sight of the shadowy rider.

All the same his heart was beating a little faster as he turned into Brunswick Square. All the houses were in pitchy darkness, as they naturally would be at one o'clock in the morning, so it was only with great difficulty that Steel could make out a number here and there. As he walked slowly and hesitatingly along the cycle bell drummed impatiently ahead of him.

"A hint to me," David muttered. "Stupid that I should have forgotten the directions to read the number over the fanlight. Also it is logical to suppose that I am going to find lights at No. 219. All right, my friend; no need to swear at me with that bell of yours."

He quickened his pace again and finally stopped before one of the big houses where lights were gleaming from the hall and dining-room windows. They were electric lights by their great power, and, save for the hall and dining-room, the rest of the house lay in utter darkness. The cycle bell let off an approving staccato from behind the blankety fog as Steel pulled up.

There was nothing abnormal about the house, nothing that struck the adventurer's eye beyond the extraordinary vividness of the crimson blind. The two side-windows of the big bay were evidently shuttered, but the large centre gleamed like a flood of scarlet overlaid with a silken sheen. Far across the pavement the ruby track struck into the heart of the fog.

"Vivid note," Steel murmured. "I shall remember that impression."

He was destined never to forget it, but it was only one note in the gamut of adventure now. With a firm step he walked up the marble flight and turned the handle. It felt dirty and rusty to the touch. Evidently the servants were neglectful, or they were employed by people who had small regard for outward appearances.

The door opened noiselessly, and Steel closed it behind him. A Moorish lantern cast a brilliant flood of light upon a crimson carpet, a chair, and an empty oak umbrella-stand. Beyond this there was no atom of furniture in the hall. It was impossible to see beyond the dining-room door, for a heavy red velvet curtain was drawn across. David's first impression was the amazing stillness of the place. It gave him a queer feeling that a murder had been committed there, and that everybody had fled, leaving the corpse behind. As David coughed away the lump in his throat the cough sounded strangely hollow.

He passed into the dining-room and looked eagerly about him. The room was handsomely furnished, if a little conventional—a big mahogany table in the centre, rows of mahogany chairs upholstered in morocco, fine modern prints, most of them artist's proofs, on the walls. A big marble clock, flanked by a pair of vases, stood on the mantelshelf. There were a large number of blue vases on the sideboard. The red distemper had faded to a pale pink in places.

"Tottenham Court Road," Steel smiled to himself. "Modern, solid, expensive, but decidedly inartistic. Ginger jars fourteen guineas a pair, worth about as many pence. Moneyed people, solid and respectable, of the middle class. What brings them playing at mystery like this?"

The room was most brilliantly lighted both from overhead and from the walls. On the shining desert of the dining-table lay a small, flat parcel addressed to David Steel, Esq. The novelist tore off the cover and disclosed a heap of crackling white papers beneath. Rapidly he fluttered the crisp sheets over—seventy-five Bank of England notes for £10 each.

It was the balance of the loan, the price paid for Steel's presence. All he had to do now was to place the money in his pocket and walk out of the house. A few steps and he would be free with nobody to say him nay. It was a temptation, but Steel fought it down. He slipped the precious notes into his pocket and buttoned his coat tightly over them. He had no fear for the coming day now.

"And yet," he murmured, "what of the price I shall have to pay for this?"

Well, it was worth a ransom. And, so long as there was nothing dishonourable attached to it, Steel was prepared to redeem his pledge. He knew perfectly well from bitter experience that the poor man pays usurious rates for fortune's favours. And he was not without a strange sense of gratitude. If—

Click, click, click. Three electric switches were snapped off almost simultaneously outside, and the dining-room was plunged into pitchy darkness. Steel instantly caught up a chair. He was no coward, but he was a novelist with a novelist's imagination. As he stood there the sweetest, most musical laugh in the world broke on his ear. He caught the swish of silken drapery and the subtle scent that suggested the fragrance of a woman's hair. It was vague, undefined, yet soothing.

"Pray be seated, Mr. Steel," the silvery voice said. "Believe me, had there been any other way, I would not have given you all this trouble. You found the parcel addressed to you? It is an earnest of good faith. Is not that a correct English expression?"

David murmured that it was. But what did the speaker mean? She asked the question like a student of the English language, yet her accent and phrasing were perfect. She laughed again noiselessly, and once more Steel caught the subtle, entrancing perfume.

"I make no further apology for dragging you here at this time," the sweet voice said. "We knew that you were in the habit of sitting up alone late at night, hence the telephone message. You will perhaps wonder how we came to know so much of your private affairs. Rest assured that we learnt nothing in Brighton. Presently you may gather why I am so deeply interested in you; I have been for the past fortnight. You see, we were not quite certain that you would come to our assistance unless we could find some means of coercing you. Then we go to one of the smartest inquiry agents in the world and say: 'Tell us all about Mr. David Steel without delay. Money is no object.' In less than a week we know all about Beckstein. We leave matters till the last moment. If you only knew how revolting it all was!"

"So your tone seems to imply, madam," Steel said, drily.

"Oh, but truly. You were in great trouble, and we found a way to get you out. At a price; ah, yes. But your trouble is nothing compared with mine—which brings me to business. A fortnight ago last Monday you posted to Mr. Vanstone, editor of the Piccadilly Magazine, the synopsis of the first four or five chapters of a proposed serial for the journal in question. You open that story with a young and beautiful woman who is in deadly peril. Is not that so?"

"Yes," Steel said, faintly. "It is just as you suggest. But how—"

"Never mind that, because I am not going to tell you. In common parlance—is not that the word?—that woman is in a frightful fix. There is nothing strained about your heroine's situation, because I have heard of people being in a similar plight before. Mr. Steel, I want you to tell me truthfully and candidly, can you see the way clear to save your heroine? Oh, I don't mean by the long arm of coincidence or other favourite ruses known to your craft. I mean by common sense, logical methods, by brilliant ruses, by Machiavelian means. Tell me, do you see a way?"

The question came eagerly, almost imploringly, from the darkness. David could hear the quick gasps of his questioner, could catch the rustle of the silken corsage as she breathed.

"Yes," he said, "I can see a brilliant way out that would satisfy the strictest logician. But you—"

"Thank Heaven! Mr. Steel, I am your heroine. I am placed in exactly the same position as the woman whose story you are going to write. The setting is different, the local colouring is not the same, but the same deadly peril menaces me. For the love of Heaven hold out your hand to save a lonely and desperate woman whose only crime is that she is rich and beautiful. Providence had placed in my hands the gist of your heroine's story. Hence this masquerade; hence the fact that you are here to-night. I have helped you—help me in return."

It was some time before Steel spoke.

"It shall be as you wish," he said. "I will tell you how I propose to save my heroine. Her sufferings are fiction; yours will be real. But if you are to be saved by the same means, Heaven help you to bear the troubles that are in front of you. Before God, it would be more merciful for me to be silent and let you go your own way."

David was silent for some little time. The strangeness of the situation had shut down on him again, and he was thinking of nothing else for the moment. In the dead stillness of the place he could hear the quick breathing of his companion; the rustle of her dress seemed near to him and then to be very far off. Nor did the pitchy darkness yield a jot to his now accustomed eyes. He held a hand close to his eyes, but he could see nothing.

"Well?" the sweet voice in the darkness said, impatiently. "Well?"

"Believe me, I will give you all the assistance possible. If you would only turn up the light—"

"Oh, I dare not. I have given my word of honour not to violate the seal of secrecy. You may say that we have been absurdly cautious in this matter, but you would not think so if you knew everything. Even now the wretch who holds me in his power may have guessed my strategy and be laughing at me. Some day, perhaps—"

The speaker stopped, with something like a sob in her throat.

"We are wasting precious time," she went on, more calmly. "I had better tell you my history. In your story a woman commits a crime: she is guilty of a serious breach of trust to save the life of a man she loves. By doing so she places the future and the happiness of many people in the hands of an abandoned scoundrel. If she can only manage to regain the thing she has parted from the situation is saved. Is not that so?"

"So far you have stated the case correctly," David murmured.

"As I said before, I am in practically similar case. Only, in my situation, I hastened everything and risked the happiness of many people for the sake of a little child."

"Ah!" David cried. "Your own child? No! The child of one very near and dear to you, then. From the mere novelist point of view, that is a far more artistic idea than mine. I see that I shall have to amend my story before it is published."

A rippling little laugh came like the song of a bird in the darkness.

"Dear Mr. Steel," the voice said, "I implore you to do nothing of the kind. You are a man of fertile imagination—a plot more or less makes no difference to you. If you publish that story you go far on the way to ruin me."

"I am afraid that I am in the dark in more senses than one," David murmured.

"Then let me enlighten you. Daily your books are more widely read. My enemy is a great novel reader. You publish that story, and what results? You not only tell that enemy my story, but you show him my way out of the difficulty, and show him how he can checkmate my every move. Perhaps, after I have escaped from the net—"

"You are right," Steel said, promptly. "From a professional point of view the story is abandoned. And now you want me to show you a rational and logical, a human way out."

"If you can do so you have my everlasting gratitude."

"Then you must tell me in detail what it is you want to recover. My heroine parts with a document which the villain knows to be a forgery. Money cannot buy it back because the villain can make as much money as he likes by retaining it. He does as he likes with the family property; he keeps my heroine's husband out of England by dangling the forgery and its consequences over his head. What is to be done? How is the ruffian to be bullied into a false sense of security by the one man who desires to throw dust in his eyes?"

"Ah," the voice cried, "ah, if you could only tell me that! Let my ruffian only imagine that I am dead; let him have proofs of it, and the thing is done. I could reach him then; I could tear from him the letter that—but I need not go into details. But he is cunning as the serpent. Nothing but the most convincing proofs would satisfy him."

"A certificate of death signed by a physician beyond reproach?"

"Yes, that would do. But you couldn't get a medical man like that to commit felony."

"No, but we could trick him into it," Steel exclaimed. "In my story a fraud is perpetrated to blind the villain and to deprive him of his weapons. It is a case of the end justifying the means. But it is one thing, my dear lady, to commit fraud actually and to perpetrate it in a novel. In the latter case you can defy the police, but unfortunately you and I are dealing with real life. If I am to help you I must be a party to a felony."

"But you will! You are not going to draw back now? Mr. Steel, I have saved your home. You are a happy man compared to what you were two hours ago. If the risk is great you have brains and imagination to get out of danger. Show me how to do it, and the rest shall be mine. You have never seen me, you know nothing, not even the name of the person who called you over the telephone. You have only to keep your own counsel, and if I wade in blood to my end you are safe. Tell me how I can die, disappear, leaving that one man to believe I am no more. And don't make it too ingenious. Don't forget that you promised to tell me a rational way out of the difficulty. How can it be done?"

"In my pocket I have a cutting from the Times, which contains a chapter from the history of a medical student who is alone in London. It closely resembles my plot. He says he has no friends, and he deems it prudent for reasons we need not discuss to let the world assume that he is dead. The rest is tolerably easy. He disguises himself and goes to a doctor of repute, whom he asks to come and see his brother—i.e., himself—who is dangerously ill. The doctor goes later in the day and finds his patient in bed with severe internal inflammation. This is brought about by a free use of albumen. I don't know what amount of albumen one would take without extreme risk, but you could pump that information out of any doctor. Well, our medical man calls again and yet again, and finds his patient sinking. The next day the patient, disguised, calls upon his doctor with the information that his 'brother' is dead. The doctor is not in the least surprised, and without going to view the body gives a certificate of death. Now, I admit that all this sounds cheap and theatrical, but you can't get over facts. The thing actually happened a little time ago in London, and there is no reason why it shouldn't happen again."

"You suggest that I should do this thing?" the voice asked.

"Pardon me, I did nothing of the kind," Steel replied "You asked me to show you how my heroine gets herself out of a terrible position, and I am doing it. You are not without friends. The way I was called up tonight and the way I was brought here prove that. With the aid of your friends the thing is possible to you. You have only to find a lodging where people are not too observant and a doctor who is too busy, or too careless, to look after dead patients, and the thing is done. If you desire to be looked upon as dead—especially by a powerful enemy—I cannot recommend a more natural, rational way than this. As to the details, they may be safely left to you. The clever manner in which you have kept up the mystery to-night convinces me that I have nothing to teach you in this direction. And if there is anything more I can do—"

"A thousand, thousand thanks," the voice cried, passionately. "To be looked upon as 'dead,' to be near to the rascal who smiles to think that I am in my grave.... And everything so dull and prosaic on the surface! Yes, I have friends who will aid me in the business. Some day I may be able to thank you face to face, to tell you how I managed to see your plot. May I?"

The question came quite eagerly, almost imploringly. In the darkness Steel felt a hand trembling on his breast, a cool, slim hand, with many rings on the fingers. Steel took the hand and carried it to his lips.

"Nothing would give me greater pleasure," he said. "And may you be successful. Good-night."

"Good-night, and God bless you for a real gentleman and a true friend. I will go out of the room first and put the lights up afterwards. You will walk away and close the door behind you. The newspaper cutting! Thanks. And once more good-night, but let us hope not good-bye."

She was gone. Steel could hear the distant dying swish of silk, the rustling of the portière, and then, with a flick, the lights came up again. Half-blinded by the sudden illumination Steel fumbled his way to the door and into the street. As he did so Hove Town Hall clock chimed two. With a cigarette between his teeth David made his way home.

He could not think it all out yet; he would wait until he was in his own comfortable chair under the roses and palms leading from his study. A fine night of adventure, truly, and a paying one. He pressed the precious packet of notes to his side and his soul expanded.

He was home at last. But surely he had closed the door before he started? He remembered distinctly trying the latch. And here the latch was back and the door open. The quick snap of the electric light declared nobody in the dining-room. Beyond, the study was in darkness. Nobody there, but—stop!

A stain on the carpet; another by the conservatory door. Pots of flowers scattered about, and a huddled mass like a litter of empty sacks in one corner. Then the huddled mass resolved itself into the figure of a man with a white face smeared with blood. Dead! Oh, yes, dead enough.

Steel flew to the telephone and rang furiously.

"Give me 52, Police Station," he cried. "Are you there? Send somebody at once up here—15, Downend Terrace. There has been murder done here. For Heaven's sake come quickly."

Steel dropped the receiver and stared with strained eyes at the dreadful sight before him.

For some time—a minute, an hour—Steel stood over the dreadful thing huddled upon the floor of his conservatory. Just then he was incapable of consecutive ideas.

His mind began to move at length. The more he thought of it the more absolutely certain he was that he had fastened the door before leaving the house. True, the latch was only an ordinary one, and a key might easily have been made to fit it. As a matter of fact, David had two, one in reserve in case of accidents. The other was usually kept in a jewel-drawer of the dressing-table. Perhaps—

David went quietly upstairs. It was just possible that the murderer was in the house. But the closest search brought nothing to light. He pulled out the jewel-drawer in the dressing-table. The spare latch-key had gone! Here was something to go upon.

Then there was a rumbling of an electric bell somewhere that set David's heart beating like a drum. The hall light streamed on a policeman in uniform and an inspector in a dark overcoat and a hard felt hat. On the pavement was a long shallow tray, which David recognised mechanically as the ambulance.

"Something very serious, sir?" Inspector Marley asked, quietly. "I've brought the doctor with me."

David nodded. Both the inspector and the doctor were acquaintances of his. He closed the door and led the way into the study. Just inside the conservatory and not far from the huddled figure lay David's new cigar-case. Doubtless, without knowing it, the owner had whisked it off the table when he had sprung the telephone.

"'Um," Marley muttered. "Is this a clue, or yours, sir?"

He lifted the case with its diamonds gleaming like stars on a dark night. David had forgotten all about it for the time, had forgotten where it came from, or that it contained £250 in bank-notes.

"Not mine," he said. "I mean to say, of course, it is mine. A recent present. The shock of this discovery has deprived me of my senses pretty well."

Marley laid the cigar-case on the table. It seemed strange to him, who could follow a tragedy calmly, that a man should forget his own property. Meanwhile Cross was bending over the body. David could see a face smooth like that of a woman. A quick little exclamation came from the doctor.

"A drop of brandy here, and quick as possible," he commanded.

"You don't mean to say," Steel began; "you don't—"

Cross waved his arm, impatiently. The brandy was procured as speedily as possible. Steel, watching intently, fancied that he detected a slight flicker of the muscles of the white, stark face.

"Bring the ambulance here," Cross said, curtly. "If we can get this poor chap to the hospital there is just a chance for him. Fortunately, we have not many yards to go."

As far as elucidation went Marley naturally looked to Steel.

"I should like to have your explanation, sir," he said, gravely.

"Positively, I have no explanation to offer," David replied. "About midnight I let myself out to go for a stroll, carefully closing the door behind me. Naturally, the door was on the latch. When I came back an hour or so later, to my horror and surprise I found those marks of a struggle yonder and that poor fellow lying on the floor of the conservatory."

"'Um. Was the door fast on your return?"

"No, it was pulled to, but it was open all the same."

"You didn't happen to lose your latch-key during your midnight stroll, sir?"

"No, it was only when I put my key in the door that I discovered it to be open. I have a spare latch-key which I keep for emergencies, but when I went to look for it just now the key was not to be found. When I came back the house was perfectly quiet."

"What family have you, sir? And what kind of servants?"

"There is only myself and my mother, with three maids. You may dismiss any suspicion of the servants from your mind at once. My mother trained them all in the old vicarage where I was born, and not one of the trio has been with us less than twelve years."

"That simplifies matters somewhat," Marley said, thoughtfully. "Apparently your latch-key was stolen by somebody who has made careful study of your habits. Do you generally go for late walks after your household has gone to bed, sir?"

David replied somewhat grudgingly that he had never done such a thing before. He would like to have concealed the fact, but it was bound to come out sooner or later. He had strolled along the front and round Brunswick Square. Marley shrugged his shoulders.

"Well, it's a bit of a puzzle to me," he admitted. "You go out for a midnight walk—a thing you have never done before—and when you come back you find somebody has got into your house by means of a stolen latch-key and murdered somebody else in your conservatory. According to that, two people must have entered the house."

"That's logic," David admitted. "There can be no murder without the slain and the slayer. My impression is that somebody who knows the ways of the house watched me depart. Then he lured his victim in here under pretence that it was his own house—he had the purloined latch-key—and murdered him. Audacious, but a far safer way than doing it out of doors."

But Marley's imagination refused to go so far. The theory was plausible enough, he pointed out respectfully, if the assassin had been assured that these midnight rambles were a matter of custom. The point was a shrewd one, and Steel had to admit it. He almost wished now that he had suggested that he often took these midnight rambles. He regretted the fiction still more when Marley asked if he had had some appointment elsewhere to-night.

"No," David said, promptly, "I hadn't."

He prevaricated without hesitation. His adventure in Brunswick Square could not possibly have anything to do with the tragedy, and nothing would be gained by betraying that trust.

"I'll run round to the hospital and come and see you again in the morning, sir," Marley said. "Whatever was the nature of the crime, it wasn't robbery, or the criminal wouldn't have left that cigar-case of yours behind. Sir James Lythem had one stolen like that at the last races, and he valued it at £80."

"I'll come as far as the hospital with you," said Steel.

At the bottom of the flight of steps they encountered Dr. Cross and the policeman. The former handed over to Marley a pocket-book and some papers, together with a watch and chain.

"Everything that we could find upon him," he explained.

"Is the poor fellow dead yet?" David asked.

"No," Cross replied. "He was stabbed twice in the back in the region of the liver. I could not say for sure, but there is just a chance that he may recover. But one thing is pretty certain—it will be a good long time before he is in a position to say anything for himself. Good-night, Mr. Steel."

David went indoors thoughtfully, with a general feeling that something like a hand had grasped his brain and was squeezing it like a sponge. He was free from his carking anxiety now, but it seemed to him that he was paying a heavy price for his liberty. Mechanically, he counted out the bank-notes, and almost as mechanically he cut his initials on the gun-metal inside the cigar-case. He was one of the kind of men who like to have their initials everywhere.

He snapped the lights out and went to bed at last. But not to sleep. The welcome dawn came at length and David took his bath gratefully. He would have to tell his mother what had happened, suppressing all reference to the Brunswick Square episode. It was not a pleasant story, but Mrs. Steel assimilated it at length over her early tea and toast.

"It might have been you, my dear," she said, placidly. "And, indeed, it is a dreadful business. But why not telephone to the hospital and ask how the poor fellow is?"

The patient was better but was still in an unconscious condition.

Steel swallowed a hasty breakfast and hurried off town- wards. He had £1,000 packed away in his cigar-case, and the sooner he was free from Beckstein the better he would be pleased. He came at length to the offices of Messrs. Mossa and Mack, whose brass-plate bore the legend that the gentry in questions were solicitors, and that they also had a business in London. As David strode into the offices of the senior partner that individual looked up with a shade of anxiety in his deep, Oriental eyes.

"If you have come to offer terms," he said, nasally, "I am sorry—"

"To hear that I have come to pay you in full," David said, grimly; "£974 16s. 4d. up to yesterday, which I understand is every penny you can rightfully claim. Here it is. Count it."

He opened the cigar-case and took the notes therefrom. Mr. Mossa counted them very carefully indeed. The shade of disappointment was still upon his aquiline features. He had hoped to put in execution to-day and sell David up. In that way quite £200 might have been added to his legitimate earnings.

"It appears to be all correct," Mossa said, dismally.

"So I imagined, sir. You will be so good as to indorse the receipt on the back of the writ. Of course you are delighted to find that I am not putting you to painful extremities. Any other firm of solicitors would have given me time to pay this. But I am like the man who journeyed from Jericho to Jerusalem—"

"And fell amongst thieves! You dare to call me a thief? You dare—"

"I didn't," David said, drily. "That fine, discriminating mind of yours saved me the trouble. I have met some tolerably slimy scoundrels in my time, but never any one of them more despicable than yourself. Faugh! the mere sight of you sickens me. Let me get out of the place so that I can breathe."

David strode out of the office with the remains of his small fortune rammed into his pocket. In the wild, unreasoning rage that came over him he had forgotten his cigar-case. And it was some little time before Mr. Mossa was calm enough to see the diamonds winking at him.

"Our friend is in funds," he muttered. "Well, he shall have a dance for his cigar-case. I'll send it up to the police-station and say that some gentleman or other left it here by accident. And if that Steel comes back we can say that there is no cigar-case here. And if Steel does not see the police advertisement he will lose his pretty toy, and serve him right. Yes, that is the way to serve him out."

Mr. Mossa proceeded to put his scheme into execution whilst David was strolling along the sea front. He was too excited for work, though he felt easier in his mind than he had done for months. He turned mechanically on to the Palace Pier, at the head of which an Eastbourne steamer was blaring and panting. The trip appealed to David in his present frame of mind. Like most of his class, he was given to acting on the spur of the moment.... It was getting dark as David let himself into Downend Terrace with his latch-key.

How good it was to be back again! The eye of the artist rested fondly upon the beautiful things around. And but for the sport of chance, the whim of fate, these had all passed from him by this time. It was good to look across the dining-table over venetian glass, to see the pools of light cast by the shaded electric, to note the feathery fall of flowers, and to see that placid, gentle face in its frame of white hair opposite him. Mrs. Steel's simple, unaffected pride in her son was not the least gratifying part of David's success.

"You have not suffered from the shock, mother?" he asked.

"Well, no," Mrs. Steel confessed, placidly. "You see, I never had what people call nerves, my dear. And, after all, I saw nothing. Still, I am very, very sorry for that poor young man, and I have sent to inquire after him several times."

"He is no worse or I should have heard of it."

"No, and no better. And Inspector Marley has been here to see you twice to-day."

David pitied himself as much as a man could pity himself considering his surroundings. It was rather annoying that this should have happened at a time when he was so busy. And Marley would have all sorts of questions to ask at all sorts of inconvenient seasons.

Steel passed into his study presently and lighted a cigarette. Despite his determination to put the events of yesterday from his mind, he found himself constantly returning to them. What a splendid dramatic story they would make! And what a fascinating mystery could be woven round that gun-metal cigar-case!

By the way, where was the cigar-case? On the whole it would be just as well to lock the case away till he could discover some reasonable excuse for its possession. His mother would be pretty sure to ask where it came from, and David could not prevaricate so far as she was concerned. But the cigar-case was not to be found, and David was forced to the conclusion that he had left it in Mossa's office.

A little annoyed with himself he took up the evening Argus. There was half a column devoted to the strange case at Downend Terrace, and just over it a late advertisement to the effect that a gun-metal cigar-case had been found and was in the hands of the police awaiting an owner.

David slipped from the house and caught a bus in St. George's Road.

At the police-station he learnt that Inspector Marley was still on the premises. Marley came forward gravely. He had a few questions to ask, but nothing to tell.

"And now perhaps you can give me some information?" David said, "You are advertising in to-night's Argus a gun-metal cigar-case set with diamonds."

"Ah," Marley said, eagerly, "can you tell us anything about it?"

"Nothing beyond the fact that I hope to satisfy you that the case is mine."

Marley stared open-mouthed at David for a moment, and then relapsed into his sapless official manner. He might have been a detective cross-examining a suspected criminal.

"Why this mystery?" David asked. "I have lost a gun-metal cigar-case set with diamonds, and I see a similar article is noted as found by the police. I lost it this morning, and I shrewdly suspect that I left it behind me at the office of Mr. Mossa."

"The case was sent here by Mr. Mossa himself," Marley admitted.

"Then, of course, it is mine. I had to give Mr. Mossa my opinion of him this morning, and by way of spiting me he sent that case here, hoping, perhaps, that I should not recover it. You know the case Marley—it was lying on the floor of my conservatory last night."

"I did notice a gun-metal case there," Marley said, cautiously.

"As a matter of fact, you called my attention to it and asked if it was mine."

"And you said at first that it wasn't, sir."

"Well, you must make allowances for my then frame of mind," David laughed. "I rather gather from your manner that somebody else has been after the case; if that is so, you are right to be reticent. Still, it is in your hands to settle the matter on the spot. All you have to do is to open the case, and if you fail to find my initials, D.S., scratched in the left-hand top corner, then I have lost my property and the other fellow has found his."

In the same reticent fashion Marley proceeded to unlock a safe in the corner, and from thence he produced what appeared to be the identical cause of all this talk. He pulled the electric table lamp over to him and proceeded to examine the inside carefully.

"You are quite right," he said, at length. "Your initials are here."

"Not strange, seeing that I scratched them there last night," said David, drily. "When? Oh, it was after you left my house last night."

"And it has been some time in your possession, sir?"

"Oh, confound it, no. It was—well, it was a present from a friend for a little service rendered. So far as I understand, it was purchased at Lockhart's, in North Street. No, I'll be hanged if I answer any more of your questions, Marley. I'll be your Aunt Sally so far as you are officially concerned. But as to yonder case, your queries are distinctly impertinent."

Marley shook his head gravely, as one might over a promising but headstrong boy.

"Do I understand that you decline to account for the case?" he asked.

"Certainly I do. It is connected with some friends of mine to whom I rendered a service a little time back. The whole thing is and must remain an absolute secret."

"You are placing yourself in a very delicate position, Mr. Steel."

David started at the gravity of the tone. That something was radically wrong came upon him like a shock. And he could see pretty clearly that, without betraying confidence, he could not logically account for the possession of the cigar-case. In any case it was too much to expect that the stolid police officer would listen to so extravagant a tale for a moment.

"What on earth do you mean, man?" he cried.

"Well, it's this way, sir," Marley proceeded to explain. "When I pointed out the case to you lying on the floor of your conservatory last night you said it wasn't yours. You looked at it with the eyes of a stranger, and then you said you were mistaken. From information given me last night I have been making inquiries about the cigar-case. You took it to Mr. Mossa's, and from it you produced notes to the value of nearly £1,000 to pay off a debt. Within eight-and forty hours you had no more prospect of paying that debt than I have at this moment. Of course, you will be able to account for those notes. You can, of course?"

Marley looked eagerly at his visitor. A cold chill was playing up and down Steel's spine. Not to save his life could he account for those notes.

"We will discuss that when the proper time comes," he said, with fine indifference.

"As you please, sir. From information also received I took the case to Walen's, in West Street, and asked Mr. Walen if he had seen the case before. Pressed to identify it, he handed me a glass and asked me to find the figures (say) '1771. x 3,' in tiny characters on the edge. I did so by the aid of the glass, and Mr. Walen further proceeded to show me an entry in his purchasing ledger which proved that a cigar-case in gun-metal and diamonds bearing that legend had been added to the stock quite recently—a few weeks ago, in fact."

"Well, what of that?" David asked, impatiently. "For all I know, the case might have come from Walen's. I said it came from a friend who must needs be nameless for services equally nameless. I am not going to deny that Walen was right."

"I have not quite finished," Marley said, quietly. "Pressed as to when the case had been sold, Mr. Walen, without hesitation, said: 'Yesterday, for £72 15s.' The purchaser was a stranger, whom Mr. Walen is prepared to identify. Asked if a formal receipt had been given, Walen said that it had. And now I come to the gist of the whole matter. You saw Dr. Cross hand me a mass of papers, etc., taken from the person of the gentleman who was nearly killed in your house?"

David nodded. His breath was coming a little faster. His quick mind had run on ahead; he saw the gulf looming before him.

"Go on," said he, hoarsely, "go on. You mean to say that—"

"That amongst the papers found in the pocket of the unfortunate stranger was a receipted bill for the very cigar-case that lies here on the table before you!"

Steel dropped into a chair and gazed at Inspector Marley with mild surprise. At the same time he was not in the least alarmed. Not that he failed to recognise the gravity of the situation, only it appealed in the first instance to the professional side of his character.

"Walen is quite sure?" he asked. "No possible doubt about that, eh?"

"Not in the least. You see, he recognised his private mark at once, and Brighton is not so prosperous a place that a man could sell a £70 cigar-case and forget all about it—that is, a second case, I mean. It's most extraordinary."

"Rather! Make a magnificent story, Marley."

"Very," Marley responded, drily. "It would take all your well-known ingenuity to get your hero out of this trouble."

Steel nodded gravely. This personal twist brought him to the earth again. He could clearly see the trap into which he had placed himself. There before him lay the cigar-case which he had positively identified as his own; inside, his initials bore testimony to the fact. And yet the same case had been identified beyond question as one sold by a highly respectable local tradesman to the mysterious individual now lying in the Sussex County Hospital.

"May I smoke a cigarette?" David asked.

"You may smoke a score if they will be of any assistance to you, sir," Marley replied. "I don't want to ask you any questions and I don't want you—well, to commit yourself. But really, sir, you must admit—"

The inspector paused significantly. David nodded again.

"Pray proceed," he said: "speak from the brief you have before you."

"Well, you see it's this way," Marley said, not without hesitation. "You call us up to your house, saying that a murder has been committed there; we find a stranger almost at his last gasp in your conservatory with every signs of a struggle having taken place. You tell us that the injured man is a stranger to you; you go on to say that he must have found his way into your house during a nocturnal ramble of yours. Well, that sounds like common sense on the face of it. The criminal has studied your habits and has taken advantage of them. Then I ask if you are in the habit of taking these midnight strolls, and with some signs of hesitation you say that you have never done such a thing before. Charles Dickens was very fond of that kind of thing, and I naturally imagined that you had the same fancy. But you had never done it before. And, the only time, a man is nearly murdered in your house."

"Perfectly correct," David murmured. "Gaboriau could not have put it better. You might have been a pupil of my remarkable acquaintance Hatherly Bell."

"I am a pupil of Mr. Bell's," Marley said, quietly. "Seven years ago he induced me to leave the Huddersfield police to go into his office, where I stayed until Mr. Bell gave up business, when I applied for and gained my present position. Curious you should mention Mr. Bell's name, seeing that he was here so recently as this afternoon."

"Staying in Brighton?" Steel asked, eagerly. "What is his address?"

"No. 219, Brunswick Square."

It took all the nerve that David possessed to crush the cry that rose to his lips. It was more than strange that the man he most desired to see at this juncture should be staying in the very house where the novelist had his great adventure. And in the mere fact might be the key to the problem of the cigar-case.

"I'll certainly see Bell," he muttered. "Go on, Marley."

"Yes, sir. We now proceed to the cigar-case that lies before you. It was also lying on the floor of your conservatory on the night in question. I suggested that here we might have found a clue, taking the precaution at the same time to ask if the article in question was your property. You looked at the case as one does who examines an object for the first time, and proceeded to declare that it was not yours. I am quite prepared to admit that you instantly corrected yourself. But I ask, is it a usual thing for a man to forget the ownership of a £70 cigar-case?"

"A nice point, and I congratulate you upon it," David said.

"Then we will take the matter a little farther. A day or two ago you were in dire need of something like £1,000. Temporarily, at any rate, you were practically at the end of your resources. If this money were not forthcoming in a few hours you were a ruined man. In vulgar parlance, you would have been sold up. Mossa and Mack had you in their grip, and they were determined to make all they could out of you. The morning following the outrage at your house you call upon Mr. Mossa and produce the cigar-case lying on the table before you. From that case you produce notes sufficient to discharge your debt—Bank of England notes, the numbers of which, I need hardly say, are in my possession. The money is produced from the case yonder, which case we know was sold to the injured man by Mr. Walen."

Marley made a long and significant pause. Steel nodded.

"There seems to be no way out of it," he said.

"I can see one," Marley suggested. "Of course, it would simplify matters enormously if you merely told me in confidence whence came those notes. You see, as I have the numbers, I could verify your statement beyond question, and—"

Marley paused again and shrugged his shoulders. Despite his cold, official manner, he was obviously prompted by a desire to serve his companion. And yet, simple as the suggestion seemed, it was the very last thing with which Steel could comply.

The novelist turned the matter over rapidly in his mind. His quick perceptions flashed along the whole logical line instantaneously. He was like a man who suddenly sees a midnight landscape by the glare of a dazzling flash of lightning.

"I am sorry," he said, slowly, "very sorry, to disappoint you. Were our situations reversed, I should take up your position exactly. But it so happens that I cannot, dare not, tell you where I got those notes from. So far as I am concerned they came honestly into my hands in payment for special services rendered. It was part of my contract that I should reveal the secret to nobody. If I told you the story you would decline to believe it; you would say that it was a brilliant effort of a novelist's imagination to get out of a dangerous position."

"I don't know that I should," Marley replied. "I have long since ceased to wonder at anything that happens in or connected with Brighton."

"All the same I can't tell you, Marley," Steel said, as he rose. "My lips are absolutely sealed. The point is: what are you going to do?"

"For the present, nothing," Marley replied. "So long as the man in the hospital remains unconscious I can do no more than pursue what Beaconsfield called 'a policy of masterly inactivity.' I have told you a good deal more than I had any right to do, but I did so in the hope that you could assist me. Perhaps in a day or two you will think better of it. Meanwhile—"

"Meanwhile I am in a tight place. Yes, I see that perfectly well. It is just possible that I may scheme some way out of the difficulty, and if so I shall be only too pleased to let you know. Good-night, Marley, and many thanks to you."

But with all his ingenuity and fertility of imagination David could see no way out of the trouble. He sat up far into the night scheming; there was no flavour in his tobacco; his pictures and flowers, his silver and china, jarred upon him. He wished with all his heart now that he had let everything go. It need only have been a temporary matter, and there were other Cellini tankards, and intaglios, and line engravings in the world for the man with money in his purse.

He could see no way out of it at all. Was it not possible that the whole thing had been deliberately planned so as to land him and his brains into the hands of some clever gang of swindlers? Had he been tricked and fooled so that he might become the tool of others? It seemed hard to think so when he recalled the sweet voice in the darkness and its passionate plea for help. And yet the very cigar-case that he had been told was the one he admired at Lockhart's had proved beyond question to be one purchased from Walen's!

If he decided to violate his promise and tell the whole story nobody would believe him. The thing was altogether too wild and improbable for that. And yet, he reflected, things almost as impossible happen in Brighton every day. And what proof had he to offer?

Well, there was one thing certain. At least three-quarters of those bank-notes—the portion he had collected at the house with the crimson blind—could not possibly be traced to the injured man. And, again, it was no fault of Steel's that Marley had obtained possession of the numbers of the notes. If the detective chose to ferret out facts for himself no blame could attach to Steel. If those people had only chosen to leave out of the question that confounded cigar-case!

David's train of thought was broken as an idea came to him. It was not so long since he had a facsimile cigar-case in his hand at Lockhart's, in North Street. Somebody connected with the mystery must have seen him admiring it and reluctantly declining the purchase, because the voice from the telephone told him that the case was a present and that it had come from the famous North Street establishment.

"By Jove!" David cried. "I'll go to Lockhart's tomorrow and see if the case is still there. If so, I may be able to trace it."

Fairly early the next morning David was in North Street. For the time being he had put his work aside altogether. He could not have written a dozen consecutive lines to save the situation. The mere effort to preserve a cheerful face before his mother was a torture. And at any time he might find himself forced to meet a criminal charge.

The gentlemanly assistant at Lockhart's remembered Steel and the cigar-case perfectly well, but he was afraid that the article had been sold. No doubt it would be possible to obtain a facsimile in the course of a few days.

"Only I required that particular one," Steel said. "Can you tell me when it was sold and who purchased it?"

A junior partner did, and could give some kind of information. Several people had admired the case, and it had been on the point of sale several times. Finally, it had passed into the hands of an American gentleman staying at the Metropole.

"Can you tell me his name?" David asked, "or describe him?"

"Well, I can't, sir," the junior partner said, frankly. "I haven't the slightest recollection of the gentleman. He wrote from the Metropole on the hotel paper describing the case and its price and inclosed the full amount in ten-dollar notes and asked to have the case sent by post to the hotel. When we ascertained that the notes were all right, we naturally posted the case as desired, and there, so far as we are concerned, was an end of the matter."

"You don't recollect his name?"

"Oh, yes. The name was John Smith. If there is anything wrong—-"

David hastily gave the desired assurance. He wanted to arouse no suspicion. All the same, he left Lockhart's with a plethora of suspicions of his own. Doubtless the jewellers would be well and fairly satisfied so long as the case had been paid for, but from the standpoint of David's superior knowledge the whole transaction fairly bristled with suspicion.

Not for one moment did Steel believe in the American at the Metropole. Somebody stayed there doubtless under the name of John Smith, and that said somebody had paid for the cigar-case in dollar notes the tracing of which might prove a task of years. Nor was it the slightest use to inquire at the Metropole, where practically everybody is identified by a number, and where scores come and go every day. John Smith would only have to ask for his letters and then drop quietly into a sea of oblivion.

Well, David had got his information, and a lot of use it was likely to prove to him. As he walked thoughtfully homewards he was debating in his mind whether or not he might venture to call at or write to 219, Brunswick Square, and lay his difficulties before the people there. At any rate, he reflected, with grim bitterness, they would know that he was not romancing. If nothing turned up in the meantime he would certainly visit Brunswick Square.

He sat in his own room puzzling the matter out till his head ached and the flowers before him reeled in a dazzling whirl of colour. He looked round for inspiration, now desperately, as he frequently did when the warp of his delicate fancy tangled. The smallest thing sometimes fed the machine again—a patch of sunshine, the chip on a plate, the damaged edge of a frame. Then his eye fell on the telephone and he jumped to his feet.

"What a fool I am!" he exclaimed. "If I had been plotting this business out as a story. I should have thought of that long ago.... No, I don't want any number, at least, not in that way. Two nights ago I was called up by somebody from London who held the line for fully half an hour or so. I've—I've forgotten the address of my correspondent, but if you can ascertain the number... yes, I shall be here if you will ring me up when you have got it.... Thanks."

Half an hour passed before the bell trilled again. David listened eagerly. At any rate, now he was going to know the number whence the mysterious message came—0017, Kensington, was the number. David muttered his thanks and flew to his big telephone directory. Yes, there it was—"0017, 446, Prince's Gate, Gilead Gates."

The big volume dropped with a crash on the floor. David looked down at the crumpled volume with dim, misty amazement.

"Gilead Gates," he murmured. "Quaker, millionaire, and philanthropist. One of the most highly-esteemed and popular men in England. And from his house came the message which has been the source of all the mischief. And yet there are critics who say the plots of my novels are too fantastic!"

The emotion of surprise seemed to have left Steel altogether. After the last discovery he was prepared to believe anything. Had anybody told him that the whole Bench of Bishops was at the bottom of the mystery he would have responded that the suggestion was highly probable.

"Still, it's what the inimitable Dick Swiveller would call a staggerer," he muttered. "Gates, the millionaire, the one great capitalist who has the profound respect of the labour world. No, a man with a record like that couldn't have anything to do with it. Still, it must have been from his house that the mysterious message came. The post-office people working the telephone trunk line would know that—a fact which probably escaped the party who called me up.... I'll go to Brunswick Square and see that woman. Money or no money, I'll not lie under an imputation like this."

There was one thing to be done beforehand, and that was to see Dr. Cross. From the latter's manner he evidently knew nothing of the charge hanging over Steel's head. Marley was evidently keeping that close to himself and speaking to nobody.

"Oh, the man is better." Cross said, cheerfully. "He hasn't been identified yet, though the Press has given us every assistance. I fancy the poor fellow is going to recover, though I am afraid it will be a long job."

"He hasn't recovered consciousness, then?"

"No, and neither will he for some time to come. There seems to be a certain pressure on the brain which we are unable to locate, and we dare not try the Röntgen rays yet. So on the whole you are likely to escape with a charge of aggravated assault."

David smiled grimly as he went his way. He walked the whole distance to Hove along North Street and the Western Road, finally turning down Brunswick Square instead of up it, as he had done on the night of the great adventure. He wondered vaguely why he had been specially instructed to approach the house that way.

Here it was at last, 219, Brunswick Square—220 above and, of course, 218 below the house. It looked pretty well the same in the daylight, the same door, the same knocker, and the same crimson blind in the centre of the big bay window. David knocked at the door with a vague feeling of uncertainty as to what he was going to do next. A very staid, old-fashioned footman answered his ring and inquired his business.

"Can—can I see your mistress?" David stammered.

The staid footman became, if possible, a little more reserved. If the gentleman would send in his card he would see if Miss Ruth was disengaged. David found himself vaguely wondering what Miss Ruth's surname might be. The old Biblical name was a great favourite of his.

"I'm afraid I haven't a card," he said. "Will you say that Mr. Steel would like to see—er—Miss Ruth for a few minutes? My business is exceedingly pressing."

The staid footman led the way into the dining-room. Evidently this was no frivolous house, where giddy butterflies came and went; such gaudy insects would have been chilled by the solemn decorum of the place. David followed into the dining-room in a dreamy kind of way, and with the feeling that comes to us all at times, the sensation of having done and seen the same thing before.

Nothing had been altered. The same plain, handsome, expensive furniture was here, the same mahogany and engravings, the same dull red walls, with the same light stain over the fire-place—a dull, prosperous, square-toed-looking place. The electric fittings looked a little different, but that might have been fancy. It was the identical room. David had run his quarry to earth, and he began to feel his spirits rising. Doubtless he could scheme some way out of the difficulty and spare his phantom friends at the same time.

"You wanted to see me, sir? Will you be so good as to state your business?"

David turned with a start. He saw before him a slight, graceful figure, and a lovely, refined face in a frame of the most beautiful hair that he had ever seen. The grey eyes were demure, with just a suggestion of mirth in them; the lips were made for laughter. It was as if some dainty little actress were masquerading in Salvation garb, only the dress was all priceless lace that touched David's artistic perception. He could imagine the girl as deeply in earnest as going through fire and water for her convictions. Also he could imagine her as Puck or Ariel—there was rippling laughter in every note of that voice of hers.

"I—I, eh, yes," Steel stammered. "You see, I—if I only knew whom I had the pleasure of addressing?"

"I am Miss Ruth Gates, at your service. Still, you asked for me by name."

David made no reply for a moment. He was tripping over surprises again. What a fool he had been not to look out the name of the occupant of 219 in the directory. It was pretty evident that Gilead Gates had a house in Brighton as well as one in town. Not only had that telephone message emanated from the millionaire's residence, but it had brought Steel to the philanthropist's abode in Brighton. If Mr. Gates himself had strolled into the room singing a comic song David would have expressed no emotion.

"Daughter of the famous Gilead Gates?" David asked, feebly.

"No, niece, and housekeeper. This is not my uncle's own house, he has merely taken this for a time. But, Mr. Steel—"

"Mr. David, Steel—is my name familiar to you?"

David asked the question somewhat eagerly. As yet he was only feeling his way and keenly on the lookout for anything in the way of a clue. He saw the face of the girl grow white as the table-cover, he saw the lurking laughter die in her eyes, and the purple black terror dilating the pupils.

"I—I know you quite well by reputation," the girl gasped. Her little hands were pressed to her left side as if to check some deadly pain there. "Indeed, I may say I have read most of your stories. I—I hope that there is nothing wrong."

Her self-possession and courage were coming back to her now. But the spasm of fear that had shaken her to the soul was not lost upon Steel.

"I trust not," he said, gravely. "Did you know that I was here two nights ago?"

"Here!" the girl cried. "Impossible! In the house! The night before last! Why, we were all in bed long before midnight."

"I am not aware that I said anything about midnight," David responded, coldly.

An angry flush came sweeping over the face of the girl, annoyance at her own folly, David thought. She added quickly that she and her uncle had only been down in Brighton for three days.

"Nevertheless, I was in this room two nights ago," David replied. "If you know all about it, I pray you to give me certain information of vital importance to me; if not, I shall be compelled to keep my extraordinary story to myself, for otherwise you would never believe it. Do you or do you not know of my visit here?"

The girl bent her head till Steel could see nothing but the glorious amber of her hair. He could see, too, the fine old lace round her throat was tossing like a cork on a stream.

"I can tell you nothing," she said. "Nothing, nothing, nothing."

It was the voice of one who would have spoken had she dared. With anybody else Steel would have been furiously angry. In the present case he could only admire the deep, almost pathetic, loyalty to somebody who stood behind.

"Are you sure you were in this house?" the girl asked, at length.

"Certain!" David exclaimed. "The walls, the pictures, the furniture—all the same. I could swear to the place anywhere. Miss Gates, if I cannot prove that I was here at the time I name, it is likely to go very hard with me."