RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

RGL e-Book Cover 2015©

"The Mystery of the Ravenspurs," J.S. Ogilvie Publishing Co, New York, 1911

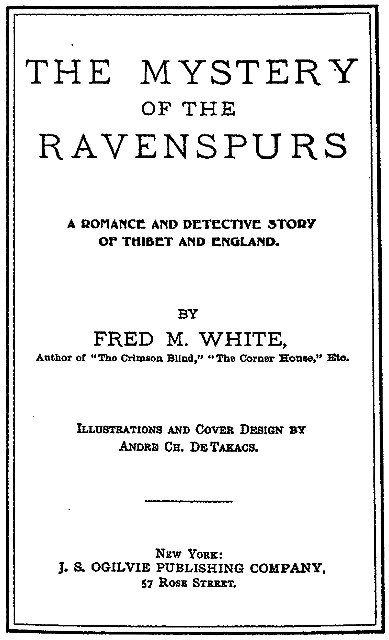

"The Mystery of the Ravenspurs," Title Page

| I - The Shadow Of A Fear II - The Wanderer Returns III - The Cry In The Night IV - 101 Brant Street V - A Ray Of Light VI - Abell Carries Out His Errand VII - More Light VIII - A Master Of Fence IX - April Days X - A Little Sunshine XI - Another Stroke In The Darkness XII - Geoffrey Is Put To The Test XIII - Reeling Off The Thread XIV - "It Might Be You" XV - Ralph Ravenspur's Conceit XVI - The White Flowers XVII - Whence Did They Come? XVIII - Mrs. Mona May XIX - Vera Is Not Pleased |

XX - A Fascinating

Woman XXI - The Mystery Deepens XXII - Deeper Still XXIII - Marion Explains XXIV - Marion's Double XXV - Geoffrey Is Puzzled XXVI - Geoffrey Begins To Understand XXVII - An Unexpected Guest XXVIII - More Of The Bees XXIX - Mrs. May At Ravenspur XXX - A Leaf From The Past XXXI - The Silk Thread XXXII - More From The Past XXXIII - Vera Sees Something XXXIV - Exit Tchigorsky XXXV - Mrs. May Is Pleased XXXVI - Mrs. May Learns Something XXXVII - Diplomacy XXXVIII - Geoffrey Gets A Shock |

XXXIX - Princess Zara's

Terms XL - The Iron Cage XLI - Waiting XLII - The Search XLIII - Nearer XLIV - Still Nearer XLV - Baffled XLVI - Nearing The End XLVII - Tchigorsky Further Explains XLVIII - More From The Past XLIX - Ralph Takes Charge L - A Kind Uncle LI - "What Does This Mean?" LII - "As Proof Of Holy Writ" LIII - A Little Light LIV - Exit The Asiatics LV - A Shock For The Princess LVI - Marion Comes Back LVII - Hand And Foot |

This story was first brought out about a year ago under a somewhat different title in a high grade book and sold at $1.25 per copy, and at that price had a ready sale. The publishers were good friends of ours and as the story created such marked interest we secured from them the right to publish it as a paper-covered book, which we are selling at 25 cents each by the thousands of copies; indeed, we considered it so popular that we thought that all of the subscribers of THE ILLUSTRATED COMPANION would like to read the story and should enjoy the right. We go upon the principle that we ought not to withhold any good thing from our readers that we can afford to give them.

Our publication is published for our subscribers. Our subscribers were not created for our publication. Therefore we have secured the serial rights to the story and every one of our subscribers will enjoy the pleasure of reading this entrancing story of mystery and adventure whether they buy the book or not.—Ed. note.

Cover page of "The Illustrated Companion," Mar 1913

A grand old castle looks out across the North Sea, and the fishermen toiling on the deep catch the red flash from Ravenspur Point as their forefathers have done for many generations.

The Ravenspurs and their great granite fortress have made history between them. Every quadrangle and watch-tower and turret has its legend of brave deeds and bloody deeds, of fights for the king and the glory of the flag. And for five hundred years there has been no Ravenspur who has not acquitted himself like a man. Theirs is a record to be proud of.

Time has dealt lightly with the home of the Ravenspurs. It is probably the most perfect mediaeval castle in the country. The moat and the drawbridge are still intact; the portcullis might be worked by a child. And landwards the castle looks over a fair domain of broad acres where the orchards bloom and flourish and the red beeves wax fat in the pastures.

A quiet family, a handsome family, a family passing rich in the world's goods, they are strong and brave—a glorious chronicle behind them, and no carking cares ahead.

Surely, then, the Ravenspurs should be happy and contented beyond most men. Excepting the beat of the wings of the Angel of Death, that comes to all sooner or later, surely no sorrow dwelt there that the hand of time could fail to soothe.

And yet over them hung the shadow of a fear.

No Ravenspur had ever slunk away from any danger, however great, so long as it was tangible; but there was something here that turned the stoutest heart to water, and caused strong men to start at their shadows.

For five years now the curse had lain heavy on the house of Ravenspur.

It had come down upon them without warning; at first in the guise of a series of accidents and misfortunes, until gradually it became evident that some cunning and remorseless enemy was bent upon exterminating the Ravenspurs root and branch.

There had been no warning given, but one by one the Ravenspurs died mysteriously, horribly, until at last no more than seven of the family remained. The North country shuddered in speaking of the ill-starred family. The story had found its way into print.

Scotland Yard had taken the case in hand, but still the hapless Ravenspurs died, mysteriously murdered, and even some of those who survived had tales to unfold of marvellous escapes from destruction.

The fear grew on them like a haunting madness. From first to last not one single clue, however small, had the murderers left behind. Family archives were ransacked and personal histories explored with a view to finding some forgotten enemy who had originated this vengeance. But the Ravenspurs had ever been generous and kind, honorable to men and true to women, and none could lay a finger on the blot.

In the whole history of crime no such weird story had ever been told before. Why should this blow fall after the lapse of all these years? What could the mysterious foe hope to gain by this merciless slaughter? And to struggle against the unseen enemy was in vain.

As the maddening terror deepened, the most extraordinary precautions were taken to baffle the assassin. Eighteen months ago the word had gone out for the gathering of the family at the castle. They had come without followers or retainers of any kind; every servant had been housed outside the castle at nightfall, and the grim old fortress had been placed in a state of siege.

They waited upon themselves, they superintended the cooking of their own food, no strange feet crossed the drawbridge. When the portcullis was raised, the most ingenious burglar would have failed to find entrance. At last the foe was baffled; at last the family was safe. There was no secret passages, no means of entry; and here salvation lay.

Alas, for fond hopes! Within the last year and a half three of the family had perished in the same strange and horrible fashion.

There was Richard Ravenspur, a younger son of Rupert, the head of the house, with his wife and boy. Richard Ravenspur had been found dead in his bed poisoned by some lemonade; his wife had walked into the moat in the darkness; the boy had fallen from one of the towers into a stone quadrangle and been instantly killed.

The thing was dreadful, inexplicable to a degree. The enemy who was doing this thing was in the midst of them. And yet no stranger passed those iron gates; none but Ravenspurs dwelt within the walls. Eye looked into eye and fell again, ashamed that the other should know the suspicions racking each poor distracted brain.

And there were only seven of them now, who almost longed for the death they dreaded.

There was Rupert Ravenspur, the head of the family, a fine, handsome, white-headed man, who had distinguished himself in the Crimea and the Indian Mutiny. There was his son Gordon who some day might succeed him; there was Gordon's wife and his daughter Vera. Then there was Geoffrey Ravenspur, the orphan son of one Jasper Ravenspur, who had fallen under the scourge two years before.

And also there was Marian Ravenspur, the orphan daughter of Charles Ravenspur, another son who had died in India five years before of cholera. Mrs. Charles was there, the child of an Indian prince, and from her Marion had inherited the dark beauty and soft, glorious eyes that made her beloved of the whole family.

A strange tale surely, a hideous nightmare, and yet so painfully realistic. One by one they were being cut off by the malignant destroyer, and ere long the family would be extinct. It seemed impossible to fight against the desolation that always struck in the darkness, and never struck in vain.

Rupert Ravenspur looked out from the leads above the castle to the open sea, and from thence to the trim lawns and flower-beds away to the park, where the deer stood knee-deep in the bracken.

It was a fair and perfect picture of a noble English homestead, far enough removed apparently from crime and violence. And yet!

A deep sigh burst from the old man's breast; his lips quivered. The shadow of that awful fear was in his eyes. Not that he feared for himself, for the snows of seventy years lay upon his head, and his life's work was done.

It was others he was thinking of. The bright bars of the setting sun shone on a young and graceful couple below coming towards the moat. A tender light filled old Ravenspur's eyes.

Then he started as a gay laugh reached his ears. The sound caught him almost like a blow. Where had he heard a laugh like that before? It seemed strangely out of place. And yet those two were young, and they loved one another. Under happier auspices, Geoffrey Ravenspur would some day come into the wide acres and noble revenues, and take his cousin Vera to wife.

"May God spare them!" Ravenspur cried aloud. "Surely the curse must burn itself out some time, or the truth must come to light. If I could only live to know that they were to be happy!"

The words were a fervent prayer. The dying sun that turned the towers and turrets of the castle to a golden glory fell on his white, quivering face. It lit up the agony of the strong man with despair upon him. He turned as a hand lay light as thistledown on his arm.

"Amen with all my heart, dear grandfather," a gentle voice murmured. "I could not help hearing what you said."

Ravenspur smiled mournfully. He looked down into a pure, young face, gentle and placid, like that of a madonna, and yet full of strength. The dark brown eyes were so clear that the white soul seemed to gleam behind them. There was Hindoo blood in Marion Ravenspur's veins, but she bore no trace of the fact. And out of the seven surviving members of that ill-fated race, Marion was the most beloved. All relied upon her, all trusted her. In the blackest hour her courage never faltered; she never bowed before the unseen terror.

Ravenspur turned upon her almost fiercely.

"We must save Vera and Geoffrey," he said. "They must be preserved. The whole future of our race lies with those two young people. Watch over them, Marion; shield Vera from every harm. I know that she loves you. Swear that you will protect her from every evil!"

"There is no occasion to swear anything," Marion said in her clear, sweet voice. "Dear, don't you know that I am devoted heart and soul to your interests? When my parents died, and I elected to come here in preference to returning to my mother's people, you received me with open arms. Do you suppose that I could ever forget the love and affection that have been poured upon me? If I can save Vera she is already saved. But why do you speak like this to-day?"

Ravenspur gave a quick glance around him.

"Because my time has come," he whispered hoarsely. "Keep this to yourself, Marion, for I have told nobody but you. The black assassin is upon me. I wake at nights with fearful pains at my heart—I cannot breathe. I have to fight for my life, as my brother Charles fought for his two years ago. To-morrow morning I may be found dead in my bed—as Charles was. Then there will be an inquest, and the doctors will be puzzled, as they were before."

"Grandfather! You are not afraid?"

"Afraid! I am glad—glad, I tell you. I am old and careworn, and the suspense is gradually sapping my senses. Better death, swift and terrible, than that. But not a word of this to the rest, as you love me!"

The hour was growing late, and the family were dining in the great hall. Rupert Ravenspur sat at the head of the table, with Gordon's wife opposite him. The lovers sat smiling and happy side by side. Across the table Marion beamed gently upon the company. Nothing ever seemed to eclipse her quiet gaiety; she was the life and soul of the party. There was something angelic about the girl as she sat there clad in soft, diaphanous white.

Lamps gleamed on the fair damask, on the feathery daintiness of flowers, and on the lush purple and gold and russet of grapes and peaches. From the walls long lines of bygone Ravenspurs looked down—fair women in hoops and farthingale, men in armor. There was a flash of color from the painted roof.

Presently the soft-footed servants would quit the castle for the night, for under the new order of things nobody slept in the castle excepting the family. Also, it was the solemn duty of each servitor to taste every dish as it came to the table. A strange precaution, but necessary in the circumstances.

For the moment the haunting terror was forgotten. Wines red and white gleamed and sparkled in crystal glasses. Rupert Ravenspur's worn, white face relaxed. They were a doomed race, and they knew it; yet laughter was there, a little saddened, but eyes brightened as they looked from one to another.

By and bye the servants began to withdraw. The cloth was drawn in the old-fashioned way, a long row of decanters stood before the head of the house and was reflected in the shining, brown polished mahogany. Big log fires danced and glowed from the deep ingle-nooks; from outside came the sense of the silence.

An aged butler stood before Ravenspur with a key on a salver.

"I fancy that is all, sir," he said.

Ravenspur rose and made his way along the corridor to the outer doorway. Here he counted the whole of the domestic staff carefully past the drawbridge, and then the portcullis was raised. Ravenspur Castle and its inhabitants were cut off from the outer world. Nobody could molest them till morning.

And yet the curl of a bitter smile was on Ravenspur's face as he returned to the dining-hall. Even in the face of these precautions two of the garrison had gone down before the unseen hand of the assassin. There was some comfort in the reflection that the outer world was barred off, but it was futile, childish, in vain.

The young people, with Mrs. Charles, had risen from the table and had gathered on the pile of skins and cushions in one of the ingle-nooks. Gordon Ravenspur was sipping his claret and holding a cigar with a hand that trembled.

Hardy man as he was, the shadow lay upon him also; indeed, it lay upon them all. If the black death failed to strike, then madness would come creeping in its track. Thus it was that evening generally found the family all together. There was something soothing in the presence of numbers.

They were talking quietly, almost in whispers. Occasionally a laugh would break from Vera, only to be suppressed with a smile of apology. Ravenspur looked fondly into the blue eyes of the dainty little beauty whom they all loved so dearly.

"I hope I didn't offend you, grandfather," she said.

In that big hall voices sounded strained and loud. Ravenspur smiled.

"Nothing you could do would offend me," he said. "It may be possible that a kindly Providence will permit me to hear the old roof ringing with laughter again. It may be, perhaps, that that is reserved for strangers when we are all gone."

"Only seven left," Gordon murmured.

"Eight, father," Vera suggested. She looked up from the lounge on the floor with the flicker of the wood fire in her violet eyes. "Do you know I had a strange dream last night. I dreamt that Uncle Ralph came home again. He had a great black bundle in his arms, and when the bundle burst open it filled the hall with a gleaming light, and in the centre of that light was the clue to the mystery."

Ravenspur's face clouded. Nobody but Vera would have dared to allude to his son Ralph in his presence.

For over Ralph Ravenspur hung the shadow of disgrace—a disgrace he had tried to shift on to the shoulders of his dead brother Charles, Marion's father. Of that dark business none knew the truth but the head of the family. For twenty years he had never mentioned his erring son's name.

"It is to be hoped that Ralph is dead," he said harshly.

A sombre light gleamed in his eyes. Vera glanced at him half-timidly. But she knew how deeply her grandfather loved her, and this gave her courage to proceed. "I don't like to hear you talk like that," she said. "It is no time to be harsh or hard on anybody. I don't know what he did, but I have always been sorry for Uncle Ralph. And something tells me he is coming home again. Grandfather, you would not turn him away?"

"If he were ill, if he were dying, if he suffered from some grave physical affliction, perhaps not. Otherwise—"

Ravenspur ceased to talk. The brooding look was still in his eyes; his white head was bent low on his breast.

Marion's white fingers touched his hand caressingly. The deepest bond of sympathy existed between these two. And at the smile in Marion's eye Ravenspur's face cleared.

"You would do all that is good and kind," Marion said. "You cannot deceive me; oh, I know you too well for that. And if Uncle Ralph came now!"

Marion paused, and the whole group looked one to the other with startled eyes. With nerves strung tightly like theirs, the slightest deviation from the established order of things was followed by a feeling of dread and alarm. And now, on the heavy silence of the night, the great bell gave clamorous and brazen tongue.

Ravenspur started to his feet.

"Strange that anyone should come at this time of night," he said. "No, Gordon, I will go. There can be no danger, for this is tangible."

He passed along the halls and passages till he came to the outer oak. He let down the portcullis.

"Come into the light," he cried, "and let me see who you are."

A halting, shuffling step advanced, and presently the gleam of the hall lantern shone upon the face of a man whose features were strangely seamed and scarred. It seemed as if the whole of his visage had been scored and carved in criss-cross lines until not one inch of uncontaminated flesh remained.

His eyes were closed; he came forward with fumbling, outstretched hands, as if searching for some familiar object. The features were expressionless, but this might have been the result of those cruel scars. But the whole aspect of the man spoke of dogged, almost pathetic, determination.

"You look strange and yet familiar to me," said Ravenspur. "Who are you, and whence do you come?"

"I know you," the stranger replied in a strangled whisper. "I could recognise your voice anywhere. You are my father."

"And you are Ralph, Ralph, come back again!"

There was horror, indignation, surprise in the cry. The words rang loud and clear, so loud and clear that they reached the dining-hall and brought the rest of the party hurrying out into the hall.

Vera came forward with swift, elastic stride. With a glance of shuddering pity at the scarred face she laid a hand on Ravenspur's arm.

"My dream," she whispered. "It may be the hand of God. Oh, let him stay!"

"There is no place here for Ralph Ravenspur," the old man cried.

The outcast still fumbled his way forward. A sudden light of intelligence flashed over Gordon as he looked curiously at his brother.

"I think, sir," he said, "that my brother is suffering from some great affliction. Ralph what is it? Why do you feel for things in that way?"

"I must," the wanderer replied. "I know every inch of the castle. I could find my way in the darkest night over every nook and corner. Father, I have come back to you. I was only to come back to you if I were in sore need or if I were deeply afflicted. Look at me! Does my face tell you nothing?"

"Your face is—is dreadful. And as for your eyes, I cannot see them."

"You cannot see them," Ralph said in that dreadful, thrilling, strangled whisper, "because I have no sight; because I am blind."

Without a word Ravenspur caught his unhappy son by the hand and led him to the dining-hall, the family following in awed silence.

The close clutch of the silence lay over the castle like the restless horror that it was. The caressing drowsiness of healthy slumber was never for the hapless Ravenspurs now. They clung round the Ingle-nook till the last moment; they parted with a sigh and a shudder, knowing that the morrow might find one face missing, one voice silenced for ever.

Marion alone was really cheerful; her smiling face, her gentle courage were as the cool breath of the north wind to the others. But for her they would have gone mad with the haunting horror long since.

She was one of the last to go. She still sat pensive in the ingle, her hands clasped behind her head, her eyes gazing with fascinated astonishment at Ralph Ravenspur.

In some strange, half-defined fashion it seemed to her that she had seen a face scarred and barred like that before. And in the same vague way the face reminded her of her native India.

It was a strong face, despite the blight that suffering had laid upon it. The lips were firm and straight, the sightless eyes seemed to be seeking for something, hunting as a blind wolf might have done. The long, slim, damp fingers twitched convulsively, feeling upwards and around as if in search of something.

Marion shuddered as she imagined those hooks of steel pressed about her throat choking the life out of her.

"Where are you going to sleep?" Ravenspur asked abruptly.

"In my old room," Ralph replied. "Nobody need trouble about me. I can find my way about the castle as well as if I had my eyes. After all I have endured, a blanket on the floor will be a couch of down."

"You are not afraid of the family terror?"

Ralph laughed. He laughed hard down in his throat, chuckling horribly.

"I am afraid of nothing," he said; "If you only knew what I know you would not wish to live. I tell you I would sit and see my right arm burnt off with slow fire if I could wipe out the things I have seen in the last five years! I heard of the family fetish at Bombay, and that was why I came home. I prefer a slumbering hell to a roaring one."

He spoke as if half to himself. His words were enigmas to the interested listeners; yet, wild as they seemed, they were cool and collected.

"Some day you shall tell us your adventures," Ravenspur said not unkindly, "how you lost your sight, and whence came those strange disfigurements."

"That you will never know," Ralph replied. "Ah! there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our narrow and specious philosophy. There are some things it is impossible to speak of, and my trouble is one of them. Only to one man could I mention it, and whether he is alive or dead I do not know."

Marion rose. The strangely-uttered words made her feel slightly hysterical. She bent over Ravenspur and kissed him fondly. Moved by a strong impulse of pity, she would have done the same by her uncle Ralph, but that he seemed to divine her presence and her intention. The long, slim hands went up.

"You must not kiss me, my child," he said. "I am not fit to be touched by pure lips like yours. Good-night."

Marion turned away, chilled and disappointed. She wondered why Ralph spoke like that, why he shuddered at her approach as if she had been an unclean thing. But in that house of singular happenings one strange matter more or less was nothing.

"The light of my eyes," Ravenspur murmured. "After Vera, the creature I love best on earth. What should we do without her?"

"What, indeed?" Ralph said quietly. "I cannot see, but I can feel what she is to all of you. Good-night, father, and thank you."

Ravenspur strode off with a not unkindly nod. As a matter of fact, he was more moved by the return of the wanderer and his evident sufferings and misfortunes than he cared to confess. He brooded over these strange things till at length he lapsed into troubled and uneasy slumber.

The intense gripping silence deepened. Ralph Ravenspur still sat in the ingle with his face bent upon the glowing logs as if he could see, and as if he were seeking for some inspiration in the sparkling crocus flame.

Then without making the slightest noise, he crept across the hall, feeling his way along with his fingertips to the landing above.

He had made no idle boast. He knew every inch of the castle. Like a cat he crept to his room, and there, merely discarding his coat and boots, he took a blanket from the bed.

Into the corridor he stepped and then, lying down under the hangings of Cordova leather, wrapped himself up cocoon fashion in his blanket and dropped into a sound sleep. The mournful silence brooded, the rats scratched behind the oaken panelled walls.

Then out of the throat of the darkness came a stifled cry. It was the fighting rattle made by the strong man suddenly deprived of the power to breathe.

Again it came, and this time more loudly, with a ring of despair in it. In the dead silence it seemed to fill the whole house, but the walls were thick, and beyond the corridor there was no cognisance of anything being in the least wrong.

But the man in the blanket against the arras heard it, and struggled to his feet. A long period of vivid personal danger had sharpened his senses. His knowledge of woodcraft enabled him to locate the cry to a yard.

"My father," he whispered. "I am only just in time."

He felt his way rapidly, yet noiselessly, along the few feet between his resting-place and Ravenspur's room. Imminent as the peril was, he yet paused to push his blanket out of sight As he came to the door of Ravenspur's room the cry rose higher. He stooped, and then his fingers touched something warm.

"Marion," he said; "I can catch the subtle fragrance of your hair."

The girl swallowed a scream. She was trembling from head to foot with fear and excitement. It was dark, the cry from within was despairing, the intense horror of it was dreadful.

"Yes, yes," she whispered hoarsely. '"I was lying awake and I heard it. And that good old man told me today that his time was coming. I—I was going to rouse the house. The door is locked."

"Do nothing of the sort. Stand aside."

The voice was low but commanding. Marion obeyed mechanically. With great strength and determination Ralph flung himself against the door. At the second assault the rusty iron bolt gave and the door flew open.

Inside, Ravenspur lay on his bed. By his bedside a night light cast a feeble, pallid ray. There was nobody in the room besides Ravenspur himself. He lay back absolutely rigid, a yellow hue was over his face like a painted mask, his eyes were wide open, his lips twisted convulsively. Evidently he was in some kind of cataleptic fit, and his senses had not deserted him.

He was powerless to move, and made no attempt to do so. The man was choking to death; and yet his limbs were rigid. A sickly, sweet odor filled the room and caused Ralph to double up and gasp for breath. It was as if the whole atmosphere were drenched with a fine spray of chloroform. Marion stood in the doorway like a fascinated white statue of fear and despair.

"What is it?" she whispered. "What is that choking smell?"

Ralph made no reply. He was holding his breath hard. There was a queer, grinning smile on his face as he turned towards the window.

The fumbling, clutching, long hands rested for a moment on Ravenspurs forehead, and the next moment there was a sound of smashing glass, as with his naked fists Ralph beat in the lozenge-shaped windows.

A quick, cool draught of air rushed through the room, and the figure of on the bed ceased to struggle.

"Come in," said Ralph. "There is no danger now."

Marion entered. She was trembling from head to foot; her face was like death.

"What is it? What is it?" she cried. "Uncle Ralph, do you know what it is?"

"That is a mystery," Ralph replied. "There is some fiend at work here. I only guessed that the sickly odor was the cause of the mischief. You are better, sir?"

Ravenspur was sitting up in bed. The color had come to his lips; he no longer struggled to breathe.

"I am all right," he said. His eye beamed affectionately on Marion. "Ever ready and ever quick, child, you saved my life from that nameless horror."

"It was Uncle Ralph," said Marion. "I heard your cry, but Uncle Ralph was here as soon as I was. And it was a happy idea of his to break the window."

"It was that overpowering drug," said Ravenspur. "What it is and where it came from must always remain a mystery. This is a new horror to haunt me—and yet there were others who died in their beds mysteriously. I awoke to find myself choking; I was stifled by that sweet smelling stuff; I could feel that my heart was growing weaker. But go, my child; you will catch your death of cold. Go to bed."

With an unsteady smile Marion disappeared. As she closed the door behind her, Ravenspur turned and grasped his son's wrist fiercely.

"Do you know anything of this?" he demanded. "You are blind, helpless; yet you were on the spot instantly. Do you know anything of this I say?"

Ralph shook his head.

"It was good luck," he said. "And how should I know anything? Ah! a blind man is but a poor detective."

Yet as Ralph passed to his strange quarters, there was a queer look on his face. The long, lean claws were crooked as if they were fastened about the neck of some enemy, some foe to the death.

"The hem of the mystery," he muttered. "Patience, and prudence, and the day shall come when I shall have it by the throat, and such a lovely throat too!"

There was nothing about the house to distinguish it from its stolid and respectable neighbors. It had a dingy face, woodwork painted a dark red, with the traditional brass knocker and bell-pull. The windows were hung with curtains of the ordinary type, the venetian blinds were half-down, which in itself is a sign of middle-class respectability. In the centre of the red door was a small brass plate bearing the name of Dr. Sergius Tchigorsky.

Not that Dr. Tchigorsky was a medical practitioner in the ordinary sense of the word. No neatly-appointed 'pill-box' ever stood before 101; no patient ever passed the threshold.

Tchigorsky was a savant and a traveller to boot; a man who dealt in strange and out-of-the-way things; and the interior of his house would have been a revelation to the top-hatted, frock-coated doctors and lawyers and city men who elected to make their home in Brant-street W.

The house was crammed with curiosities and souvenirs of travel from basement to garret. A large sky-lighted billiard-room at the back of the house had been turned into a library and laboratory combined.

And here, when not travelling, Tchigorsky spent all his time, seeing strange visitors from time to time, Mongolians, Hindoos, natives of Thibet—for Tchigorsky was one of the three men who had penetrated to the holy city of Lassa, and returned to tell the tale.

The doctor came into his study from his breakfast, and stood ruminating, rubbing his hands before the fire. In ordinary circumstances he would have been a fine man of over six feet in height.

But a cruel misfortune had curved his spine, while his left leg dragged almost helplessly behind him, his hands were drawn up as if the muscles had been cut and then knotted up again.

Tchigorsky had entered Lassa five years ago as a god who walks upright. When he reached the frontier six months later he was the wreck he still remained. And of those privations and sufferings Tchigorsky said nothing. But there were times when his eyes gleamed and his breath came short, and he pined for the vengeance yet to be his.

As to his face, it was singularly strong and intellectual. Yet it was disfigured with deep seams checkered like a chessboard. We have seen something like it before, for the marks were identical with those that disfigured Ralph Ravenspur and made his face a horror to look upon.

A young man rose from the table where he was making some kind of an experiment. He was a fresh-colored Englishman, George Abell by name, and he esteemed it a privilege to call himself Tchigorsky's secretary.

"Always early and always busy," Tchigorsky said. "Is there anything in the morning papers that is likely to interest me, Abel?"

"I fancy so," Abell replied thoughtfully. "You are interested in the Ravenspur case?"

A lurid light leapt into the Russian's eyes. He seemed to be strangely moved. He paced up and down the room, dragging his maimed limb after him.

"Never more interested in anything in my life," he said. "You know as much of my past as any man, but there are matters, experiences unspeakable. My face, my ruined frame! Whence come these cruel misfortunes? That secret will go down with me to the grave. Of that I could speak to one man alone, and I know not whether that man is alive or dead."

Tchigorsky's words trailed off into a rambling, incoherent murmur. He was far away with his own gloomy and painful thoughts. Then he came back to earth with a start. He stood with his back to the fireplace, contemplating Abell.

"I am deeply interested in the Ravenspur case, as you know," he said. "A malignant fiend is at work yonder—a fiend with knowledge absolutely supernatural. You smile! I myself have seen the powers of darkness doing the bidding of mortal man. All the detectives in Europe will never lay hands upon the destroyer of the Ravenspurs. And yet, in certain circumstances, I could."

"Then, in that case, sir, why don't you?"

"Do it? I said in certain circumstances. I have part of a devilish puzzle; the other part is in the hands of a man who may be dead. I hold half of the banknote; somebody else has the other moiety. Until we can come together, we are both paupers. If I can find that other man, and he has the nerve and the pluck he used to possess, the curse of the Ravenspurs will cease. But, then, I shall never see my friend again."

"But you might solve the problem alone."

"Impossible. That man and myself made a most hazardous expedition in search of dreadful knowledge. That formula we found. For the purposes of safety, we divided it. And then we were discovered. Of what followed I dare not speak; I dare not even think.

"I escaped from my dire peril, but I cannot hope that my comrade was so fortunate. He must be dead. And without him I am as powerless as if I knew nothing. I have no proof. Yet I know quite well who is responsible for those murders at Ravenspur."

Abell stared at his chief in astonishment. He knew Tchigorsky too well to doubt the evidence of his simple word. The Russian was too strong a man to boast.

"You cannot understand," he said. "It is impossible to understand without the inner knowledge that I possess, and even my knowledge is not perfect. Were I to tell the part I know I should be hailed from one end of England to the other as a madman. I should be imprisoned for malignant slander. But if the other man turned up—if only the other man should turn up!"

Tchigorsky broke into a rambling reverie again. When he emerged to mundane matters once more he ordered Abell to read the paragraph relating to the latest phase of the tragedy of the lost Ravenspur.

"It runs," said Abell. "'Another Strange Affair at Ravenspur Castle. The mystery of this remarkable case still thickens. Late on Wednesday night Mr. Rupert Ravenspur, the head of the family, was awakened by a choking sensation and a total loss of breath. On attempting to leave his bed, the unfortunate gentleman found himself unable to move.

"'He states that the room appeared to be filled with a fine spray of some sickly, sweet drug or liquid that seemed to act upon him as chloroform does on a subject with a weak heart. Mr. Ravenspur managed to cry out, but the vapor held him down, and was slowly stifling him—"

"Ah!" Tchigorsky cried. "Ah! I thought so. Go on!"

His eyes were gleaming; his whole face glistened with excitement.

"'Providentially the cry reached the ears of another of the Ravenspurs. This gentleman burst open his father's door, and noticing the peculiar, pungent odor, had the good sense to break a window and admit air into the room.

"'This prompt action was the means of saving the life of the victim, and it is all the more remarkable because Ravenspur, a blind gentleman, who, had just returned from foreign parts.'"

A cry—a scream, broke from Tchigorsky's lips. He danced about the room like a madman. For the time being it was impossible for the astonished secretary to determine whether this was joy or anguish.

"You are upset about something, sir," he said.

Tchigorsky recovered himself by a violent effort that left him trembling like a reed swept by the wind. He gasped for breath.

"It was the madness of an overwhelming joy!" he cried. "I would cheerfully have given ten years of my life for this information. Abell, you will have to go to Ravenspur for me to-day."

Abell said nothing. He was used to these swift surprises.

"You are to see this Ralph Ravenspur, Abell," continued Tchigorsky. "You are not to call at the castle; you are to hang about till you get a chance of delivering my message unseen. The mere fact that Ralph Ravenspur is blind will suffice for a clue to his identity. Look up the timetable!"

Abell did so. He found a train to land him at Biston Junction, some ten miles from his destination. Half an hour later he was ready to start. From an iron safe Tchigorsky took a small object and laid it in Abell's hand.

"Give him that," he said; "You are simply to say, 'Tchigorsky—Danger,' and come away, unless Ralph Ravenspur desires speech with you. Now go, and as you value your life do not lose that casket."

It was a small brass box no larger than a cigarette-case, rusty and tarnished, and covered with strange characters, evidently culled from some long-forgotten tongue.

A sense of expectation, an uneasy feeling of momentous event about to happen, hung over the doomed Ravenspurs. For once, Marion appeared to feel the strain. Her face was pale, and though she strove hard to regain the old gentle gaiety, her eyes were red and swollen with weeping.

All through breakfast she watched Ralph in strange fascination. He seemed to have obtained some kind of hold over her. Yet nothing could be more patient, dull and stolid than the way in which he proceeded with his meal. He appeared to dwell in an unseen world of his own; the stirring events of the previous night had left no impression on him whatever.

For the most part, they were a sad and silent party. The terror that walked by night and day was stealing closer to them; it was coming in a new and still more dreadful form. Accident or the intervention of Providence had averted a dire tragedy. But it would come again.

Ravenspur made light of the matter. He spoke of the danger as something past. Yet it was impossible wholly to conceal the agitation that filled him. He saw Marion's pale, sympathetic face; he saw the heavy tears in Vera's eyes, and a dreadful sense of his absolute impotence came upon him.

"Let us forget it," he said, almost cheerfully. "Let us think no more of the matter. No doubt, science can explain the new mystery."

"Never," Ralph said, in a thrilling whisper. "Science is powerless here."

The speaker's sightless eyes were turned upwards; he seemed to be thinking aloud rather than addressing the company generally. Marion turned as if something had stung her.

"Uncle Ralph knows something that he conceals from us," she cried.

Ralph smiled. Yet he had the air of one who is displeased with himself.

"I know many things that are mercifully concealed from pure natures like yours," he said. "But as to what happened last night, I am as much in the dark as any of you. Ah! if I were not blind!"

A strained silence followed. One by one the company rose until the room was deserted, save for Ralph, Ravenspur and his nephew Geoffrey. The handsome lad's face was pale, his lips quivered.

"I am dreadfully disappointed, uncle," he observed.

"Meaning from your tone that you are disappointed with me, Geoff. Why?"

"Because you spoke at first as if you understood things. And then you professed to be as ignorant as the rest of us. Oh, it is awful! I—I would not care so much if I were less fond of Vera than I am. I love her; I love her with my whole heart and soul. If you could only see the beauty of her face you would understand.

"And yet when she kisses me goodnight, I am never sure that it is not for the last time. I feel that I must wake up presently to find that all is an evil dream. And we can do nothing, nothing, nothing but wait and tremble, and—die."

Ralph had no reply; indeed there was no reply to this passionate outburst. The blind man rose from the table and groped his way to the door with those long hands that seemed to be always feeling for something like the tentacles of an octopus.

"Come with me to your grandfather's room," he said. "I want you to lend me your eyes for a time."

Geoffrey followed willingly.

The bedroom was exactly as Ravenspur had quitted it, for as yet the housemaid had not been there.

"Now look round you carefully," said Ralph. "Look for something out of the common. It may be a piece of rag, a scrap of paper, a spot of grease, or a dab of some foreign substance on the carpet. Is there a fire laid here?"

"No," Geoffrey replied. "The grate is a large, open one. I will see what I can find."

The young fellow searched minutely. For some time no reward awaited his pains. Then his eyes fell upon the hearthstone.

"I can only see one little thing," he said.

"In a business like this, there are no such matters as little things," Ralph replied. "A clue that might stand on a pin's point often leads to great results. Tell me what it is that attracts your attention."

"A brown stain on the hearthstone. It is about the size of the palm of one's hand. It looks very like a piece of glue dabbed down."

"Take a knife and scrape it up," said Ralph. He spoke slowly and evidently under excitement well repressed. "Wrap it in your handkerchief and give it to me. Has the stuff any particular smell?"

"Yes," said Geoffrey. "It has a sickly, sweet odor. I am sure that I never smelt anything like it before."

"Probably not. There, I have no further need of your services, and I know that Vera is waiting for you. One word before you go—you are not to say a single word to a soul about this matter; not a single soul, mind. And now I do not propose to detain you any longer."

Geoffrey retired with a puzzled air. When the echo of his footsteps had died away, Ralph rose and crept out upon the leads. He was shivering with excitement; there was a look of eager expectation, almost of triumph, on his face.

He felt his way along the leads until he came to a group of chimneys, about the centre one of which he fumbled with his hands for some time.

Then the look of triumph on his face grew more marked and stronger.

"Assurance doubly sure," he whispered. His voice croaked hoarsely with excitement. "If I had only somebody here whom I could trust! If I told anybody here whom I suspected they would rise like one person, and hurl me into the moat. And I can do no more than suspect. Patience, patience, and yet patience."

From the terrace came the sounds of fresh young voices. They were those of Vera and Geoffrey talking almost gaily as they turned their steps towards the granite cliffs. For the nerves of youth are elastic, and they throw off the strain easily.

They walked along side by side until they came to the cliffs. Here the rugged ramparts rose high with jagged indentations and rough hollows. There were deep cups and fissures in the rocks where a regiment of soldiers might lie securely hidden. For miles the gorse was flushed with its golden glory.

"Let us sit down and forget our troubles," said Geoffrey. "How restful the time if we could sail away in a ship, Vera, away to the ends of the earth, where we could hide ourselves from this cruel vendetta and be at peace. What use is the Ravenspur property to us when we are doomed to die?"

Vera shuddered slightly, and the exquisite face grew pale.

"They might spare us," she said, plaintively. "We are young, and we have done no harm to anybody. And yet I have not lost all faith. I feel certain that Heaven above us will not permit this hideous slaughter to continue."

She laid her trembling fingers in Geoffrey's hand, and he drew her close to him and kissed her.

"It seems hard to look into your face and doubt it, dearest," he said. "Even the fiend who pursues us would hesitate to destroy you. But I dare not, I must not, think of it. If you are taken away I do not want to live."

"Nor I either, Geoff. Oh, my feelings are similar to yours!"

The dark, violet eyes filled with tears, the fresh breeze from the sea ruffled Vera's fair hair and carried her sailor-hat away up the cliff. It rested, perched upon a gorse-bush overhanging one of the ravines or cups in the rock. As Geoffrey ran to fetch the hat he looked over.

A strange sight met his astonished gaze. The hollow might have been a small stone quarry at some time. Now it was lined with grass and moss, and in the centre of the cup, which had no fissure or passage of any kind, two men were seated bending down over a small shell or gourd placed on a fire of sticks.

In ordinary circumstances there would have been nothing strange in this, for the sight of peripatetic hawkers and tinkers along the cliffs was not unusual.

From the shell on the ground a thick vapor was rising. The smell of it floated on the air to Geoffrey's nostrils. He reeled back almost sick and faint with the perfume and the discovery he had made. For that infernal stuff had exactly the same smell as the pungent drug which had come so near to destroying the life of Rupert Ravenspur only a few hours before.

He reeled back almost sick and faint with the perfume and the discovery he had made.

Here was something to set the blood tingling in the veins and the pulses leaping with a mad excitement. From over the top of the gorse Geoffrey watched with all his eyes. He saw the smoke gradually die away; he saw a small mass taken from the gourd and carefully stowed away in a metal box. Then the fire was kicked out, and all traces of it were obliterated.

Geoffrey crept back to Vera, trembling from head to foot. He had made up his mind what to do. He would say nothing of this strange discovery to Vera; he would keep it for Ralph Ravenspur's ears alone. Ralph had been in foreign parts, and might understand the enigma.

Meanwhile, it became necessary to get out of the Asiatics' way. It was not prudent for them to know that a Ravenspur was so close. Vera looked into Geoffrey's face, wondering.

"How pale you are!" she said. "And how long you have been!"

"Come and let us walk," said Geoffrey. "I—I twisted my ankle on a stone, and it gave me a twinge or two. It's all right now. Shall we see if we can get as far as Sprawl Point and back before luncheon?"

Vera rose to the challenge. She rather prided herself on her powers as a walker. The exercise caused her to glow and tingle, and all the way it never occurred to her how silent and abstracted Geoffrey had become.

When Ralph Ravenspur reached the basement, his whole aspect had changed. For the next day or two he brooded about the house, mainly with his own thoughts for company. He was ubiquitous. His silent, catlike tread carried him noiselessly everywhere. He seemed to be looking for something with those sightless eyes of his; those long fingers were crooked as if about the throat of the great mystery.

He came into the library where Rupert Ravenspur and Marion were talking earnestly. He dropped in upon them as if he had fallen from the clouds. Marion started and laughed.

"I declare you frighten me," she said. "You are like a shadow—the shadow of one's conscience."

"There can be no shadow on yours," Ralph replied. "You are too pure and good for that. Never, never will you have cause to fear me."

"All the same, I wish you were less like a cat," Ravenspur exclaimed petulantly, as Marion walked smilingly away. "Anybody would imagine that you were part of the family mystery. Ralph, do you know anything?"

"I am blind," Ralph replied doggedly. "Of what use is a blind man?"

"I don't know. They say when one sense is lost the others are sharpened. And you came home so mysteriously; you arrived at a critical moment for me; you were at my door at the time when help was sorely needed. Again, when you burst my door open you did the only thing that could have saved me."

"Common-sense, sir. You were stifling, and I gave you air."

Ravenspur shook his head. He was by no means satisfied.

"It was the common-sense that is based upon practical experience. And you prowl about in dark corners; you wander about the house in the dead of night. You hint at a strange past; but as to that past you are dumb. For Heaven's sake, if you know anything, tell me. The suspense is maddening."

"I know nothing, and I am blind," Ralph repeated. "As to my past, that is between me and my Maker. I dare not speak of it. Let me go my own way, and do not interfere with me. And whatever you do or say, tell nobody—nobody, mind—that you suspect me of knowledge of the family trouble."

Ralph turned away abruptly and refused to say more. He passed from the castle across the park slowly, but with the confidence of a man who is assured of every step. The recollection of his boyhood's days stood him in good stead. He could not see but he knew where he was, and even the grim cliffs held no terrors for him.

He came at length to a certain spot where he paused. It was here years ago that he had scaled the cliffs at the peril of his neck and found the raven's nest. He caught the perfume of the heather and the crushed fragrance of the wild thyme, but their scents were as nothing to his nostrils.

For he had caught another scent that had brought him up all standing with his head in the air. The odor was almost exhausted; there was merely a faint suspicion of it, but at the same time it spoke to Ralph as plainly as words.

He was standing near the hollow where Geoffrey had been two days ago. In his mind's eye Ralph could see into this hollow. Years before he had been used to lie there winter evenings when the brent and ducks were coming in from the sea. He scrambled down sure-footed as a goat.

Then he proceeded to grope upon the grass with those long, restless fingers. He picked up a charred stick or two, smelt it, and shook his head. Presently his hand closed upon the burnt fragments of a gourd. As Ralph raised this to his nostrils his eyes gleamed.

"I was certain of it," he muttered. "Two of the Bonzes have been here, and they have been making the pie. If I could only see!"

As yet he had not heard of Geoffrey's singular discovery. There had been no favorable opportunity of disclosing the secret.

Ralph retraced his steps moodily. For the present he was helpless. He had come across the clue to the enigma, but only he knew of the tremendous difficulties and dangers to be encountered before the heart of the mystery could be revealed. He felt cast down and discouraged. There was bitterness in his heart for those who had deprived him of his precious sight.

"Oh, if I could only see!" he cried. "A week or month to look from one eye into another, to strip off the mask and lay the black soul bare. And yet if the one only guessed what I know, my life would not be worth an hour's purchase! And if those people at the castle only knew that the powers of hell—living, raging hell—were arrayed against them! But they would not believe."

An impotent sigh escaped the speaker. Just for the moment his resolution had failed him. It was some time before he became conscious of the fact that some one was dogging his footsteps.

"Do you want to see me?" he demanded.

There was no reply for a moment. Abell came up cautiously. He looked around him, but so far as he could a see he and Ravenspur were alone. As a he caught sight of the latter's face he had no ground for further doubt.

"I did want to see you and see you alone, sir," Abell replied. "I believe I have the pleasure of speaking to Mr. Ralph Ravenspur?"

"The same, sir," Ralph said coldly. "You are a stranger to me."

"A stranger who brings a message from a friend. I was to see you alone, and for two days I have been waiting for this opportunity. My employer asks me to deliver this box into your hands."

At the same time Abell passed the little brass case into Ralph's hand. As his fingers closed upon it, a great light swept over his face; a hoarse shout came from lips that turned from red to blue, and then to white and red again, just as Tchigorsky had behaved when he discovered that this man still lived.

"Who gave you this, and what is your message?" Ravenspur panted.

"The message," said Abell, "was merely this: I was to give you the box and say, 'Tchigorsky—Danger,' and walk away, unless you detained me."

"Then my friend Tchigorsky is alive?"

"Yes, sir; it is my privilege to be his private secretary."

"A wonderful man," Ralph cried; "perhaps the most wonderful man in Europe. And to think that he is alive! If an angel had come down from heaven and asked me to crave a boon, I should have asked to have Tchigorsky in the flesh before me. You have given me new heart of grace; you are like water in a dry land. This is the happiest day I have known since—"

The speaker paused and mumbled something incoherent. But the stolid expression had gone from his scarred face, and a strange, triumphant happiness reigned in its stead. He seemed years younger, his step had grown more elastic; there was a fresh, broad ring in his voice.

"Tchigorsky will desire to see me," he said. "Indeed, it is absolutely essential that we should meet, and that without delay. A time of danger lies before us—danger that the mere mortal does not dream of. Take this to Tchigorsky and be careful of it."

He drew from a chain inside his vest a small case, almost identical to the one that Abell had just handed to him, save that it was silver, while the other was brass. On it were the same queer signs and symbols.

"That will convince my friend that the puzzle is intact," he continued. "We hold the key to the enigma—nay, the key to the past and future. But all this is so much Greek to you. I will come and see my friend on Friday, but not in the guise of Ralph Ravenspur."

"What am I to understand by that, sir?" Abell asked.

"It matters nothing what you understand," Ralph cried. "Tchigorsky will know. Tell him 7.15 at Euston on Friday, not in the guise of Ravenspur or Tchigorsky. He will read between the lines. Go and be seen with me no more."

Ralph strode off with his head in the air. His blood was singing in his ears; his pulses were leaping with a new life.

"At last!" he murmured; "after all these years for myself and my kin! At last!"

There was a curious, eager flush on Ralph Ravenspur's face. He rose from his seat and paced the room restlessly. Those long fingers were incessantly clutching at something vague and unseen. And, at the same time, he was following the story that Geoffrey had to tell with the deepest attention.

"What does it mean, uncle?" the young man asked at length.

"I cannot tell you," Ralph replied. His tones were hard and cold. "There are certain things no mortal can understand unless—; but I must not go into that. It may be that you have touched the fringe of the mystery—"

"I am certain that we are on the verge of a discovery!" Geoffrey cried eagerly. "I am sure that stuff those strangers were making was the same as the drug or whatever it was that came so near to making an end of my grandfather. If I knew what to do!"

"Nothing—do nothing, as you hope for the future!"

The words came hissing from Ralph's lips. He felt his way across to Geoffrey and laid a grip on his arm that seemed to cut like a knife.

"Forget it!" he whispered. "Fight down the recollection of the whole thing; do nothing based upon your discovery. I cannot say more, but I am going to give you advice worth much gold. Promise me that you will forget this matter; that you will not mention it to a soul. Promise!"

Geoffrey promised, somewhat puzzled and dazed. Did Ralph know everything, or was he as ignorant as the rest?

"I will do what you like," said Geoffrey. "But it is very hard. Can't you tell me a little more? I am brave and strong."

"Courage and strength have nothing to do with it. A nation could do nothing in this case. I am going to London to-day."

"You are going to London alone?"

"Why not? I came here from the other side of the world alone. I have to see a doctor about my eyes. No, there is no hope that I can ever recover my sight again; but it is possible to allay the pain they give me."Ralph departed. A dogcart deposited him at Biston Junction, and then the servant saw him safely into the London train. But presently Ralph alighted, and a porter guided him to a cab. A little later and the blind man was knocking at the door of a cottage in the poorer portion of the town.

A short man, with a seafaring air, opened the door.

"Is it you? Elphick?" Ralph asked.

The short man with the resolute face and keen, grey eyes exclaimed with pleasure:

"So you've got back at last, sir. Come in, sir. I knew you'd want me before long."

Ralph Ravenspur felt his way to a chair. James Elphick stood watching him with something more than pleasure in his eyes.

"We have no time to spare," Ralph exclaimed. "We must be in London to-night, James. I am going up to see Dr. Tchigorsky."

"Dr. Tchigorsky!" Elphick exclaimed. "Didn't I always say as how he'd get through? The man who'd get the best of him ain't born yet. But it means danger, sir."

"Danger you do not dream of," Ralph said impressively. "But I cannot discuss this with you, James. You are coming with me to London. Get the disguise out, and let me see if your hand still retains its cunning."

Apparently it had, for an hour later there walked from the cottage towards the station an elderly, stout man, with white hair and beard and whiskers. His eyes were guarded by tinted glasses; the complexion of the face was singularly clear and ruddy. All trace of those cruel criss-cross lines had gone. Wherever Elphick had learned his art, he had not failed to learn it thoroughly.

"It's perfect; though I say it as shouldn't," he remarked. "It's no use, sir; you can't get on without me. If I'd gone with you to Lassa, all that horrible torture business would never have happened."

Ralph Ravenspur smiled cautiously. The stiff dressing on his face made a smile difficult in any case.

"At all events, I shall want you now," he said.

It was nearly seven when the express train reached Euston. Ralph stood on the great bustling, echoing platform as if waiting for something. An exclamation from Elphick attracted his attention.

"There's the doctor as large as life!" he said.

"Tchigorsky!" Ralph cried. "Surely not in his natural guise. Oh, this is reckless folly! Does he court defeat at the outset of our enterprise?"

Tchigorsky bustled up. For some reason or other he chose to appear in his natural guise. Not till they were in the cab did Ravenspur venture to expostulate.

"Much learning has made you mad," he said bitterly.

"Not a bit of it," the Russian responded. "Unfortunately for me the priests of Lassa have discovered that I am deeply versed in their secrets. Not that they believe for a moment that Tchigorsky and the Russian who walked the valley of the Red Death are one and the same. They deem me to be the recipient of that unhappy man's early discoveries. But your identity remains a secret. The cleverest eyes in the world could never penetrate your disguise."

"It comforts me to hear that," Ralph replied. "Everything depends upon my identity being concealed. Once it is discovered, every Ravenspur is doomed. But I cannot understand why you escape recognition at the hands of the foe."

A bitter smile came over Tchigorsky's face.

"Can you not?" he said. "If you had your eyes you would understand. Man, I have been actually in the company of those who flung me into the valley of the Red Death and they have not known me. After that I stood in the presence of my own mother, and she asked who I was.

"The marks on my face? Well, there are plenty of explorers who have been victims to the wire helmet and have never dreamt of entering Lassa. I am a broken, bowed, decrepit wreck, I who was once so proud of my inches. The horrors of that one day have changed me beyond recognition. But you know."

Ralph shuddered from head to foot. A cold moisture stood on his forehead.

"Don't," he whispered. "Don't speak of it. When the recollection comes over me I have to hold on to my senses, as a shipwrecked sailor clings to a plank. Never mind the past—the future has peril and danger enough. You know why I am here?"

"To save your house from the curse upon it. To bring the East and West together, and tell of the vilest conspiracy the world has ever seen. Do you know who the guilty creature is, whose hand is actually striking the blow?"

"I think so; in fact I am sure of it. But who would believe my accusation?"

"Who, indeed? But we shall be in a position to prove our case, now that the secrets of the prison-house lie before us. We have three to fear."

"Yes, yes," said, Ralph. "The two Bonzes—who have actually been seen near Ravenspur—and the Princess Zara. Could she recognise me?"

Ralph asked the question in almost passionate entreaty.

"I am certain she could not," Tchigorsky replied. "Come, victory shall be ours yet. Here we are at my house at last. By the way, you have a name. You shall be my cousin, Nicholas Tchigorsky, a clever savant, who, by reason of a deplorable accident, has become both blind and dumb. Allons."

Lady Mallowbloom's reception rooms were more than usually crowded. And every other man or woman in the glittering salon was a celebrity. There was a strong sprinkling of the aristocracy to leaven the lump; here and there the flash of red cloth and gold could be seen.

In his quiet, masterly style Tchigorsky pushed his way up the stairs. Ralph Ravenspur followed, his hand upon the Russian's arm. He could feel the swish of satin draperies go by him; he caught the perfume on the warm air.

"Why do you drag me here?" he grumbled. "I can see nothing; it only bewilders me. I should have been far happier in your study."

"You mope too much," Tchigorsky said gaily. "To mingle with one's fellows is good at times. I know so many people who are here to-night."

"And I know nobody; add to which circumstances compel me to be dumb. Place me in some secluded spot with my back to the wall, and then enjoy yourself for an hour. I dare say I shall manage to kill the time."

There were many celebrities in the brilliantly-lighted room, and Tchigorsky indicated a few. A popular lady novelist passed on the arm of a poet on her way to the buffet.

"A wonderful woman," the fair authoress was saying. "Eastern and full of mystery, you know. Did you notice the eyes of the Princess?"

"Who could fail to?" was the reply. "They say that she is quite five and forty, and yet she would easily pass for eighteen, but for her knowledge of the world. Your Eastern Princess is one of the most fascinating women I have ever seen."

Others passed, and had the same theme. Ralph stirred to a faint curiosity.

"Who is the new marvel?" he asked.

"I don't know," Tchigorsky admitted. "The last new lion, I suppose. Some pretty Begum or the wife of some Oriental whose dark eyes appear to have fired society. By the crowd of people coming this way I presume the dusky beauty is among them. If so, she has an excellent knowledge of English."

A clear, sweet voice arose. At the first sound of it, Ralph jumped to his feet and clutched at his throat as if something choked him. He shook with a great agitation; a nameless fear had him in a close grip.

"Do you recognise the voice?" Ralph gasped.

The Russian was not unmoved. But his agitation was quickly suppressed. He forced Ralph down in his seat again.

"You will have to behave better than that if you are to be a trusty ally of mine," he said. "Come, that is better! Sit still; she is coming this way."

"I'm all right now," Ralph replied. "The shock of finding myself in the presence of Princess Zara was overpowering. Have no fear for me."

A tall woman, magnificently dressed, was making her way towards Tchigorsky. Her face was the hue of old ivory, and as fine; her great lustrous eyes gleamed brightly; a mass of hair was piled high on a daintily-poised head. The woman might have been extremely young so far as the touch of time was concerned, but the easy self-possession told another tale.

The red lips tightened for an instant, a strange gleam came into the dark, magnetic eyes as they fell upon Tchigorsky. Then the Indian Princess advanced with a smile, and held out her hand to the Russian.

"So you are still here?" she said.

There was the suggestion of a challenge in her tones. Her eyes met those of Tchigorsky as the eyes of two swordsmen might meet. There was a tigerish playfulness underlying the words, a call-note of significant warning.

"I still take the liberty of existing," said Tchigorsky.

"You are a brave man, doctor. Your friend here?"

"Is my cousin, Nicholas Tchigorsky. The poor fellow is blind and dumb, as the result of a terrible accident. Best not to notice him."

The Princess shrugged her beautiful shoulders as she dropped gracefully into a seat.

"I heard you were in London," she said, "and something told me that we should meet sooner or later. You are still interested in occult matters?"

Again Ralph detected the note of warning in the speech. He could see nothing of the expression on that perfect face; but he could judge it fairly well.

"I am more interested in occult matters than ever," Tchigorsky said gravely, "especially in certain discoveries placed in my hands by a traveller in Thibet."

"I am more interested in occult matters than ever,"

Tchigorsky said gravely,

"especially in certain discoveries placed in my hands by a traveller in

Thibet."

"Ah! that was your fellow-countryman. He died, you know!"

"He was murdered in the vilest manner. But before the end, he managed to convey important information to me."

"Useless information unless you had the key."

"There was one traveller who found the key, you remember?"

"True, doctor. He also, I fancy, met with an accident that, unfortunately, resulted in his death."

Ralph shuddered slightly. Princess Zara's tones were hard as steel. If she had spoken openly and callously of this man being murdered, she could not have expressed the same thing more plainly. A beautiful woman, a fascinating one; but a woman with no heart and no feeling where her hatreds were concerned.

"It is just possible I have the key," said Tchigorsky.

The eyes of the Princess blazed for moment. Then she smiled.

"Dare you use it?" she asked. "If you dare, then all the secrets of heaven and hell are yours. For four thousand years the priests of the temple at Lassa and the heads of my family have solved the future. You know what we can do. We are all-powerful for evil. We can strike down our foes by means unknown to your boasted Western science. They are all the same to us, proud potentate, ex-meddling doctor."

There was a menace in the last words. Tchigorsky smiled.

"The meddling doctor has already had personal experience," he said. "I carry the marks of my suffering to the grave. I remember how your peasants treated me, and this does not tend to relax my efforts."

"And yet you might die at any moment. If you persist in your studies you will have to die. The eyes of Western men must not look upon the secrets of the priests of Lassa and live. Be warned, Dr. Tchigorsky; be warned in time. You are brave and clever, and as such command respect. If you know anything and proclaim it to the world—"

"Civilization will come as one man, and no stone in Lassa shall stand on another. Your priests will be butchered like wild beasts; an internal plague spot will be wiped off the face of the outraged earth!"

The Princess caught her breath swiftly. Just for one moment there was murder in her eyes. She held her fan as if it were a dagger ready for the Russian's heart.

"Why should you do this thing?" she asked.

"Because your knowledge is diabolical," Tchigorsky replied. "In the first place, all who are in the secret can commit murder with impunity. As the Anglo-Saxon pushes on to the four corners of the earth that knowledge must become public property. I am going to stop that if I can."

"And if you die in the meantime? You are bold to rashness. And yet there are many things that you do not know."

"The longer I live the more glaring my ignorance becomes. I do not know whence you derive your perfect mastery of the English tongue. But I do know that I am going to see this business through."

"Man proposes, but the arm of the priest is long."

"Ah! I understand. I may die tonight. I should not mind. Still, let us argue the matter out. Say that I have already solved the whole weird business. I write twenty detailed statements; I enclose the key in each. These statements I address to a score of the leading savants in Europe.

"Then I place them in, say, a safe deposit until my death. I write to each of those wise men a letter with an enclosure not to be opened till I die. That enclosure contains a key to my safe, and presently in that safe all those savants find a packet addressed to themselves. In a week all Europe would ring with my wonderful discoveries. Think of the outcry, the wrath, the indignation!"

The Princess smiled. She could appreciate a stratagem like this. With dull, stolid and averted face, Ralph Ravenspur listened and wondered. He heard the laugh that came from the lips of the Princess; he detected the vexation underlying it. Tchigorsky was a foeman worthy of her steel.

"That you propose to do?"

"A question you will pardon me for not answering," said Tchigorsky. "You have made your move and I have made mine. Whether I am going to do the thing, or whether I have done so, remains to be seen. Whether you dare risk my death now is a matter for you to decide. Check to your king."

Again the Princess smiled. She looked searchingly into Tchigorsky's face, as if she would fain read his very soul. But she saw nothing there but the dull eyes of a man who keeps his feelings behind a mask. Then, with a flirt of her fan and a more careless mocking curtsey, she turned to go.

"You are a fine antagonist," she said; "but I do not admit yet that you are check to my king. I shall find a way. Good-night!"

She turned and plunged into the glittering crowd, and was seen no more. A strange fit of trembling came over Ravenspur as Tchigorsky led him out.

"That woman stifles me," he said. "If she had only guessed who had been seated so near to her! Tchigorsky, you played your cards well."

Tchigorsky smiled.

"I was glad of that opportunity," he said. "She meant to have me murdered; but she will hesitate for a time. We have one great advantage—we know what we have to face, and she does not. The men are on the board, the cards are on the table. It is you and I against Princess Zara and the two priests of the temple of Lassa. And we play for the lives of a good and innocent family."

"We do," Ralph said grimly. "But why—why does this fascinating Asiatic come all those miles to destroy one by one a race that she can scarcely have heard of? Why does she do it, Tchigorsky?"

"You have not guessed who the Princess is, then?"

Tchigorsky bent down and whispered three words in Ralph's ear. And not until Brant-street was reached had Ralph come back from his amazement to the land of speech.

The terror never lifted now from the old house. There were days and weeks when nothing happened, but the garrison did not permit itself to believe that the unseen enemy had abandoned the unequal contest.

The old people were prepared for the end which they believed to be inevitable. A settled melancholy was upon them, and it was only when they were together that anything like a sense of security prevailed. For the moment they were safe—there was always safety in numbers.

But when they parted for the night they parted as comrades on the eve of a bloody battle. They might meet again, but the chances were strong against it. For themselves they cared nothing; for the younger people, everything.

It was fortunate that the fine constitutions and strong nerves of Geoffrey and Vera and Marion kept them going. A really imaginative man or woman would have been driven mad by the awful suspense. But Geoffrey was bright and sunny; he always felt that the truth would come to light some day. And his buoyant sanguine nature reacted on the others.

Nearly a month had elapsed since the weird attempt on the life of Rupert Ravenspur; four weeks since Geoffrey's strange experience on the cliffs; and nothing had happened. The family had lapsed once more into their ordinary mode of living; blind Ralph was back again, feeling his way about the castle as usual, silent, moody, in the habit of gliding in upon people as a snake comes through the grass.

Ralph came in to breakfast, creeping to his chair without touching anything, dropping into it as if he had fallen from the clouds. Marion, next to him, shuddered. They were quite good friends, these two, but Marion was slightly afraid of her uncle. His secret ways repelled her; he had a way of talking with his sightless eyes upturned; he seemed to understand the unspoken thoughts of others.

"What is the matter?" he asked.

Marion laughed. None of the others had come down yet.

"What should be the matter?" she replied.

"Well, you shuddered. You should be sorry for me, my dear. Some of these days I mean to tell you the story of my life. Oh, yes, it will be a story—what a story! And you will never forget it as long as you live."

There was something uncanny in the words—a veiled threat, the suggestion of one who had waited for a full revenge, with the knowledge that the time would come. Yet the scarred face was without expression: the eyes were vacant.

"Will you not tell me now?" Marion asked softly. "I am so sorry for you."

The sweet, thrilling sympathy would have moved a stone, but it had no effect upon Ralph. He merely caressed Marion's slim fingers and smiled. It was significant of his extraordinary power that he found Marion's hand without feeling for it. He was given to touch those slim fingers. And yet he never allowed Marion to kiss him.

"All in good time," he said; "but not yet, not yet."

Before Marion could reply, Mrs. Gordon Ravenspur came into the room. Marion seemed to divine more than see that something had happened. She jumped to her feet and crossed the room.

"Dear aunt," she said quickly. "What is it?"

"Vera," Mrs. Gordon replied. "She called me into her room just now saying she was feeling far from well. I had hardly got into her room before she fainted. I have never known Vera do such a thing before."

Ralph was sitting and drumming his fingers on the table as if the subject had not the slightest interest for him. But, with the swiftness of lightning, a strange, hard, cunning expression flashed across his face and was gone. When Marion turned to him he had vanished also. It almost seemed as if he had the gift of fernseed.

"A mere passing weakness," Marion said soothingly.

"I should like to think so," Mrs. Gordon replied. "In normal circumstances I should think so. But not now; not now, Marion."

Marion sighed deeply. There were times when even she was oppressed.

"I'll go and see Vera," she said. "I am sure there is no cause for alarm."

Marion slipped rapidly away up the stone stairs and along the echoing corridor towards Vera's room. She was smiling now, and she kissed her hand to the dead and gone Ravenspurs frowning upon her from the walls. Then she burst gaily into Vera's room.

"My dear child," she cried, "you really must not alarm us by—"

She paused suddenly. Vera, fully dressed, was seated in a chair, whilst Ralph was by her side. He seemed more alive than usual; he had been saying something to Vera that had brought the color to her face. As Marion entered he grew grave and self-contained; like a snail retreating into its shell, Marion thought. He sat down, and tattooed with his fingers on the dressing-table.

"I had no idea you had company," Marion smiled.

"I intruded," Ralph said gravely. There was a sardonic inflection in his voice. "Yet I flatter myself that Vera is the better for my attention."

Marion looked swiftly from one to the other. She was puzzled. Almost flawless as she was, she had her minor weaknesses, or she had been less charming than she was, and she hated to be puzzled. Vera was no longer pale and all signs of languor had departed, yet she looked confused, and there was the trace of a blush on her cheeks.

"Sometimes I fancy that Uncle Ralph is laughing at us all," she said, with a laugh that was not altogether natural. "But I am all right now, dear Marion. Save for a racking headache, I am myself again."

Marion, solicitous for others always, flew for her smelling salts. In three strides Ralph was across the floor, and had closed the door behind her. His manner had instantly changed, he was fully of energy and action.

"Take this," he whispered. "Take it and the cure will he complete. Crush it up between your teeth and drink a glass of water afterwards."

He forced a small, white pellet between Vera's teeth; he heard her teeth crushing it. With his peculiar gift for finding things, he crossed over to the washstand and returned with a glass of water.

"You are better?" he asked, as Vera gulped the water down.