There were tears in the girl's eyes—tears of futile anger and despair. The danger was so great, and yet safety was so near. If only the black horse would stumble or swerve, if only she could work the bit into that iron mouth and bring him to a standstill altogether. Her gloves were cut to ribands now; the blue veins stood out on the slender white wrists.

And still the horse flew on down the rocky path leading to the lych-gate. He would charge through the gate into the green old churchyard beyond, but no longer with his rider fighting for life on his back. The arch of the lych-gate would sweep her from the saddle with a blow that would crush the life out of her. Mary Dashwood could see that plainly enough; she knew that she had only a few more minutes to live.

She set her teeth and blinked the welling tears from her proud blue eyes. She was not afraid—no Dashwood was ever afraid—but the pity of it! She saw the great beeches rising on either side of the path, she saw the blue sky beyond, the song of the birds came to her ears. And she was only twenty-two, and life was very dear to her.

The moment was coming ever nearer. The black horse was thundering along the straight downward path; the lych-gate was in sight. Mary discarded the idea of throwing herself from the saddle; she would have only been dashed to pieces on the rocks on either side of the road. She had been warned, too, not to take the black horse. She bent low to escape an overhanging bough; her hat was swept away; the shining chestnut hair began to stream from her shapely head.

There was a crackling of sticks in the wood on the right; surely, a hundred yards or so ahead, a face looked over the high fence, the figure of a man was holding on to the overhanging bough of an oak tree. Mary Dashwood wondered if the man realised her danger. Perhaps he did, for he crooked a leg over the bough and hung arms downward over the roadway. He was saying something in a smooth, firm voice.

"Pull to the side of the road," said the voice. It almost sounded like a command. "Drop the reins and clear your stirrup as you near me. And have no fear."

The big horse thundered on. Despite her peril, Mary did not fail to notice how strong and brown and capable the stranger's hands looked... It was all done so quickly and easily as to rob the episode of romantic danger—two hands, warm and tender, and yet firm as a steel trap, grasped the girl's slender wrists, she was floated lightly from the saddle, and in the next instant she was swaying dizzily on her feet in the road. The pride and courage of the Dashwoods availed nothing now—it was but a mere woman who fell almost fainting by the roadside.

She opened her eyes presently to the knowledge that a strong arm was supporting her. A bright blush mounted to her proud, beautiful face. The colour deepened as she saw the look, half admiration, half amusement, on the face of her rescuer.

"Mr. Darnley," she stammered. "I—I hardly expected to see you here. A little over two years ago, in Paris, you saved my life before."

"It is good to know that you have not forgotten it," Ralph Darnley murmured. "And yet the coincidence is not so strange as it seems. I did not come to these parts moved by any unaccountable impulse—I simply had business here. And I was told that a walk through the park would repay me for my trouble. As I was making a start out, through a copse I saw your predicament and hastened to your assistance. A handy tree did the rest. The only strange part of the affair is that you should be here, too."

"Nothing strange about that," the girl smiled, "seeing that the Hall is my home."

It was a commonplace statement of facts, and yet the words seemed to hurt Ralph Darnley as if they had been lashes to sting him. The honest open brown face paled perceptibly under its tan hue. A dozen emotions changed in those clear brown eyes.

"I—I don't quite understand," he remarked. "When we met in Paris two years ago, Miss Mary Mallory——"

"Quite so. Mary Dashwood Mallory. But, you see, the head of the family was alive then. He died nearly two years ago without any children, in fact, his only son died years ago somewhere abroad—it was a rather sad story—and my father came into the title and estates. He is Sir George Dashwood now. You can quite see why he changed his name."

"Of course. Only you can see that I could not possibly know this. What a grand old place it is, and what a grand old house! You must have grown very fond of it."

"I love it," Mary Dashwood cried. The look of haughty pride had faded from her face, leaving it refined and beautiful. "I love every stick and stone of it, it is part of my very life. You see, I have practically lived here always. As my father was in the Diplomatic Service, and my mother died young, it was necessary for somebody to look after me. I spent my childhood here with old Lady Dashwood, who has now gone to the dower house—such a wonderful old body!"

But Darnley did not appear to be listening. He made an effort to recover himself presently. He was like a man who dreams.

"I can quite appreciate your feelings," he said quietly. "I understand that the Dashwoods have ruled here for three hundred years. It is a fine estate; they tell me the heirlooms are almost priceless. And yet I am sorry."

The girl looked sharply up at the speaker.

"Why should you be sorry?" she demanded.

"Because it is the end of a dream," Darnley said. "I rather gathered in Paris that your father was poor. The fact levelled things up a little. It is just possible that you may remember our last evening together in Paris."

"I recollect," Mary said, the delicate colour flushing her cheeks again. "But I thought that we had closed that chapter finally, Mr. Darnley."

"No. That chapter can never be closed for me. I loved you from the first moment that we met, and I shall go on loving you till I die. I asked you to be my wife, and you refused me. The future mistress of Dashwood could not stoop to the son of a Californian rancher, though I happened to be an English gentleman by birth. I hope I took your refusal quietly, though it was a great blow to me. There can be no other woman for me, Mary."

"I am sorry," the girl said, "but see how impossible it is. Perhaps I am a little old-fashioned, perhaps it is the fault of my bringing up. That like must mate with like has always been the motto of the Dashwoods. These new people, with their wealth and noise and ostentation can never cross the threshold of Dashwood Hall. My father is fond of finance, but he never dreams of bringing his City friends here."

Darnley smiled to himself. He recollected the days in Paris, when Mary's father had been hand-in-glove with many a dubious French financier.

"We are wandering from the point," he said. "In any case your strictures do not touch me, for I have no money. My poor father left me comfortably off, as he thought, but my mine of silver is ruined now, ruined by a firm of City swindlers whom I was fool enough to regard as honest men. It was a very bad thing for me when I came in contact with Horace Mayfield."

It was the girl's turn to start guiltily. The beautiful face flushed once more.

"I know Mr. Mayfield," she said. "He is the only one of my father's business friends who comes here. We make an exception in his favour, because he is so well connected. Frankly, I do not like him, but I thought that he——"

"That he is a cold-blooded and calculating rascal to the core," Darnley said. "I trusted him, and he left me almost penniless. Many people will tell you I am saying no more than what is actually true. And, because I am poor, I came down here thinking to find a little something that belonged to my people years ago. And so I met you, Mary, and discovered that I love you with the same old pure affection, that will go on burning in my heart till I die. It may strike you as strange that a poor man should speak to Miss Dashwood, of Dashwood, like this. Mind you, I am young, and strong, and able, and I shall come into my kingdom again. And love is worth all the rest; it is better far than money, or position, or pride of birth. If I could hear you say that you cared for me now! You are so beautiful; behind all your pride the woman's heart beats true enough. May God grant that you meet the right man when the time comes! I would give you up to him willingly and shake his hand on it. But to think of your being the wife of some brainless nonentity, of some brutal ruffian who has nothing but an old title to cover his moral wickedness, why the thought is unbearable. Mary, I think I could find it in my heart to kill that man."

The words came slowly and clear as cut steel. Calm as he was, Darnley's tones vibrated with passion. He drew the girl towards him, and laid his hands on her shoulders so that he could look down into the fathomless lake of her blue eyes. Strange as it was, Mary Dashwood did not resent that which would have been insolent familiarity in anybody else. There was something so strong and dominating about this man; she thrilled with a strange tenderness and pride in the knowledge that he loved her. True, on his own confession, he was penniless, but then he treated the loss of his money in a way that only a strong man could assume.

"I love you, dear," he said, very gently and tenderly. "I love you, Mary, and no words could say more. I shall live to see the ice and pride melt from your heart, I shall live to see the beautiful womanhood within you blossom like a rose. The day will come when you will be prouder far to own a good man's heart than you will be to call yourself a Dashwood. You may frown, but I feel certain that my words will come true. And, meanwhile, I am afraid that there is no hope at all for me, my dear."

"It is impossible," Mary said coldly. Yet her voice trembled and tears came to her eyes. "Oh, I know that you are a good man and true, but you must make allowances for me. And besides, love is only a name to me. I owe my life to you, and believe me, I am too grateful for words. And if the time should ever come—oh, how selfish I am. Look at your arm. It is bruised and bleeding. It must have happened when you lifted me from the saddle. You must come up to the house and have it attended to at once."

"I don't think—" Darnley hesitated; "yes I will. It's really nothing. Let me catch your horse for you and we will walk across the path together."

There were the lodge-gates at last, with the name of the Dashwoods carved in mossy stone, and the great iron gates from the cunning hand of Quentin Matsys himself. Beyond, the noble elms planted in the days of Elizabeth led to the house, a great Tudor mansion with gabled and latticed windows covered with ivy to the quaintly carved roof-tree. The gardens spread wide on either side; there was a thick hedge of crimson roses bounding the park, and in its purple glory the dappled deer reposed. Ralph Darnley drew a deep breath as he took in the splendid beauty and serenity of it all. For three hundred years the reign of the Dashwoods had lasted, and not a stain had shown itself on the family escutcheon all that time. Darnley could excuse all Mary's pride.

"It is exquisitely beautiful," he said, with a slight catch in his voice. "How vividly it recalls Tennyson's line—'a haunt of ancient peace.' I am trying to make due allowances for your feelings, Miss Dashwood. If I had been brought up here, my views would be the same as yours. I love old houses."

Mary smiled one of her rare tender smiles. Darnley's eulogy touched her. She led the way through a great flagged hall, the walls of which were a perfect dream of carving; from their frames dead and gone Dashwoods looked down. There was oak carving everywhere, the ceilings were panelled, in the stained glass windows masses of flowers stood. Ralph would have stopped to admire it all, but Mary hurried him on.

"We will go into the breakfast-parlour," she said. "Then I will endeavour to show you that I can be useful as well as ornamental. Excuse me one moment—I must get rid of these torn gloves. Ring the bell, please, for Slight, the butler, and ask him for warm water and towels."

Ralph laid his hand on the bell as Mary flitted away. The old butler came presently, a thin little man, pink and white, the embodiment of what an old servant should be. Ralph gave his directions clearly enough, but the man stood there shaking from head to foot. There was joy and terror and amazement on his face; the tears gathered in his rheumy eyes.

"Mr. Ralph!" he whispered, "Mr. Ralph come back from the grave! Come back after all these years! What will the master say if he knows? I'm dreaming, that's what is the matter; I've gone off my head or I'm dreaming. And after forty years!"

The speaker came forward tremblingly and touched Ralph's hand. Apparently the contact with warm flesh and blood reassured him, for the pink apple bloom came back to his cheek.

"The same and yet not the same," he went on. "Stands to reason as forty years must make a deal of difference. But you are Mr. Ralph over again all the same. I loved him, sir. I mourned for him like a child of my own. I taught him to ride; I taught him to use a gun. I had to stand between him and Sir Ralph when the crash came. And you are his son as sure as there is a Heaven above us."

"Not quite so loud," Ralph said. "Pull yourself together, Slight. I take it you are old Slight about whom my father talked so often. He did not forget you, Slight. On his deathbed he gave me a message for you."

"And so my dear Mr. Ralph is dead. Dear, dear. What shall I call you, sir?"

"You are to call me nothing for the present," Ralph said. "I am Mr. Darnley, Slight, and you are to be discreet and silent. I had quite left you out of my calculation when I came here to-day; in fact, I had forgotten all about you. It never occurred to me that you would discover the likeness to what my father was forty years ago. I will ask you to meet me this evening, say, at half-past ten at the lodge-gates, for I have much to say to you."

"And, meanwhile, is nobody to know anything about you, sir?"

"Not a soul. The present head of the house never saw my father. The only one likely to recognize me would be the dowager Lady Dashwood, who is at the dower house. I am placing myself and my happiness entirely in your hands, my faithful old Slight, and I ask you not to betray me. Rest assured that it will all come right in time. Meanwhile, I have hurt my arm, and I require towels and soap and hot water."

Slight went his way with the air of a man who dreams. He came back presently, followed by Mary Dashwood. She dressed Darnley's arm skilfully enough. The touch of her fingers was soft and soothing. She was a tender and feeling woman now, without the slightest suggestion of cold pride on her face.

"I think that is all," she said quietly. "How brave and strong you are: how little you make of your courage. And yet few could have done what you did for me to-day. But I am forgetting that my father will be glad to see you. Let us go to the library."

A tall figure rose from a mass of papers heaped on a table. Here in the library was the same restful air of calm repose, the same patrician silence that brooded over everything like the spirit of the place. A flood of sunlight, tempered by the amber and blue of the stained glass windows filled the room; the rays centered upon the tall figure with the thin white face and grey hair, standing by the table.

"My daughter has been telling me everything, Mr. Darnley," Sir George said. "It was well and bravely done of you... I am glad to see you in my house."

Darnley murmured something appropriate; he hoped that the expression of his face was not betraying his emotions. For the change in Sir George since they had last met was startling. The old, jaunty, easy manner was gone, the straight figure was lost, the iron-grey hair was white as snow. There were deep lines of care and suffering graven on the pleasant face, a suggestion of fear, or fright, or remorse. This was a man who carried some secret in his heart. Darnley felt that he would have passed Sir George in the street unrecognized. And yet the man appeared to possess everything that made life worth living. Ralph ventured to offer some suitable comment on the house and the beauty of the surroundings. A look of infinite sadness overcame the features of Dashwood for the moment. The slender fingers clutched as if at something unseen, as the fingers of a drowning man might clutch at a straw.

"Yes, it is perfect enough," he said dreamily. "A perfect house in a perfect setting. And Mary loves it even more than I do. It seems almost impossible to connect this place with sin and suffering and the sordid cares of life—what is it, Slight?"

"A telegram for you, Sir George," the old butler murmured. "Is there any reply, sir?"

Sir George murmured that there was no reply. He dropped the telegram in an unconcerned way upon the table, but his hand was shaking again, and his features looked terribly white and worn.

"From Horace Mayfield," he said huskily. "He is coming down to-day, on a rather important piece of business, and will probably stay the night. By the way, Darnley, it would give me great pleasure if you would dine with us this evening."

Ralph would have refused. It would have been an exquisite pleasure to spend a long summer evening with Mary in that delightful old house, but then it seemed impossible to be under the same roof as Horace Mayfield. It appeared strange that that handsome, plausible, well-bred scoundrel should be a friend of Dashwood. Ralph was framing a courteous refusal when he became conscious that Mary was regarding him with a pleading glance. Her face was weary and anxious looking, her eyes were alight with an appeal for help. She was asking Ralph to come, and yet she did not want her father to see how eager she was.

"I shall be delighted," Ralph answered. "Half-past seven, I think. And now I must be going."

Ralph turned away into the great dim hall followed by Mary. A ray of sunlight fell upon her beautiful face and grateful blue eyes.

"That was very good of you," she murmured. "Mr. Darnley, Ralph, if I should want a friend in the near future, I feel assured that I can rely upon you."

"I love you with my whole heart and soul," Ralph replied. "And some day you will give that love to me. I would give my life for you, if necessary, and you know it."

The cloth had been drawn in the old-fashioned way, so that the candles in the ancient silver branches made pools of brown light on the polished mahogany of the dining table. Here were palms and flowers, feathery fronds, rays of light streaking the sides of blushing grapes and peaches with the downy bloom on them. The candle rays glistened somberly on deep ruby red wines in crystal decanters; the table was as a bath of silver flame in a background of sombre brown shadows. A noiseless servant or two, gliding about, ministered to the wants of the guests. How peaceful, how restful and refined it all was, Ralph thought, the only jarring note being the person opposite him, a clean-shaven, hard-featured man with a glass screwed in his left eye. And what a hard, firm mouth he had. He was quite at his ease, too, in Dashwood's presence; he chatted with glib assurance to the man whom he had robbed as deliberately as if he had picked his pocket. Actually he had met Ralph in the drawing-room an hour before, with a smile and a proffered hand, as if they had been two men taking up the threads of a desirable acquaintance.

Ralph's fingers had itched to be at the throat of the man, but he had to smile and murmur the ordinary polite commonplaces. He shut his teeth together now as he noted Mayfield's insolently familiar, not to say caressing, manner towards Mary Dashwood. Sir George looked on and smiled in a pained kind of way. He reminded Ralph unpleasantly of a well-broken dog in the presence of a harsh master. It was almost pathetic to see how Dashwood hung on any word of Mayfield. Surely there was some guilty knowledge between the two, some powerful hold that Mayfield had on his host. It was with a feeling of relief that Ralph saw Mary rise at length. He opened the door for her, and she playfully asked him not to be too long, it was so lovely a night.

"I'll come with you now," Ralph answered. "I don't care to smoke, and I never touch wine after dinner. I fear Sir George wants to talk business, which seems to me to be a desecration on an evening like this. Shall we go outside?"

"I think it would be nice," Mary said. "No, I shall not need a wrap."

She stepped through the double French window that led to the lawn. The full light of the moon flashed on her ivory shoulders and played in gilded shadows on her hair. As she looked upwards, Ralph could catch the exquisite symmetry of her face. A desire to speak possessed him, a desire to tell the girl strange and wonderful things. Here was his heart's object standing pale and beautiful by his side; he had only to stretch out his hands and the flowers were his for the plucking. It only needed a few words and the whole situation would be changed. But Ralph was silent, he was too strong and masterful a man for that. What he won he would win by sheer merit, by intrinsic worth alone. He could have purchased the kisses and caresses for which his heart hungered, but he knew that they would be no more than Dead Sea fruit on his lips.

"You are very silent," Mary said at length. "What are you thinking about?"

"About you," Ralph said boldly. "I was thinking how beautiful you looked with the fuller moonlight on your face. It is only when you recollect that you are Miss Dashwood, of Dashwood Hall, that I like your expression least. And you are not always happy."

"What do you mean by that?" Mary asked. There was a startled look in her eyes. "Why should I not be happy?"

"Why, indeed! But the fact remains that you are not. I do not want to appear inquisitive, but there is a worm in the heart of the rose somewhere. Mary, why do you allow your father to ask Mayfield here when you dislike him so much? Though you are exclusive and can show your pride, yet you allow that man to be insolently familiar with you. He laid his hand on your arm to-night, and I could have struck him for it. It is not as if you cared for him——"

"Oh, no, no," Mary said with a shudder. "I detest him. He is so cold and calculating, you cannot chock him off. I thought that when I refused to marry him——"

"Ha! I expected something of the kind. Mayfield is not the man to take 'No' for an answer once he has set his heart upon a thing. I told you before that he was a scoundrel, and I am in a position to prove it. Not that the fellow has done anything to bring himself within the grip of the law—your City rascal is too clever for that. And your father is afraid of him; he watches him as a dog watches his master. If he is in the power of that man he must get out without delay. He must raise money on the property——"

"He can't," Mary said sadly. "My father has not taken me into his confidence. But you can see how much he has aged and altered lately, and you looked quite shocked when you met this morning. I don't know what it is, but I feel that some evil is impending over him. That is why I asked you to be my friend. You see my father is not really a rich man. He has the income of this fine estate, it is true. I believe he could get rid of Horace Mayfield if he could raise money on the property, but that is impossible. Old Sir Ralph, my great uncle, had a serious quarrel with his wife—that is the present dowager Lady Dashwood, you understand. It must have been all Sir Ralph's fault, for she is the dearest old lady. The heir to the property took the side of his mother when the separation came, and left Dashwood Hall, declaring that he would never see the place again. There is only one man living who knows the whole facts of the case, and that is Slight. But his lips are sealed. The old man loved young Ralph Dashwood as if he had been his own child. Ralph the younger went off to America, and has never been heard of again. That was forty years ago. When old Sir Ralph died two years ago, and my father came into the property, no will could be found. So my father, being next of kin, succeeded to the property and the rents of the estate. It is a settled estate, and each possessor has only what is called a life-interest in it. Now it is just possible that some day an heir will turn up. It is more than likely that young Ralph Dashwood married in America, and left a family. Or he may be still alive, and is waiting to claim, for his son, that which he declined to touch himself. Most people know this, and that is why my father could never raise a penny on the family property. If he could, he would not long remain under the heel of Horace Mayfield. Oh, if we could only find a way!"

"I begin to understand," Ralph said thoughtfully. "If old Sir Ralph had died leaving a will, things might have been very different. Is that what you mean?"

"Partly. Sir Ralph died leaving a good deal of ready money. That will no doubt come to us in time, but for the present we cannot touch it in the absence of proof of the death of the youngest Ralph Dashwood. I mean the one who went to America. Old Lady Dashwood says she is sure that her husband did leave a will, and that he had divided all his money, with certain provisions. If that will could be found, we should be in a position to get rid of Mayfield. What a hateful thing this money is, and what misery it seems to bring everybody. But I am afraid that I am very selfish and exacting. Why should I worry you with our troubles?"

"My shoulders are broad, and I have very few of my own," Ralph smiled. "Indeed, I am more interested than you imagine. As I told you to-day, I am a poor man, thanks to one who is a guest here at the present moment. But, still, don't forget the fable of the mouse and the lion. I may find a means of freeing you from the net yet. But here come the others."

Mayfield emerged from the window on to the lawn. His cigar seemed to pollute the sweet-scented night; he was talking loudly to Sir George.

"We shall know presently," he said. "The worst of living buried in the country is that one is out of touch with telegrams and telephones. I told my secretary to wire directly he heard from Worham and his partner."

"Don't let us talk about it," said Sir George in a voice that shook a little. "Let us enjoy the beauty of the night. . . . I began to wonder what had become of you, Darnley. So you and Mary have been communing with Nature together. You will have a cigar before you go?"

Darnley declined the offer. He did not care to stay any longer in Mayfield's presence. And it was getting on to half-past ten, when he had promised to meet Slight. He made his excuses and passed across the lawn in the direction of the avenue. At the end of the rose garden he paused to look back.

He saw the picture of the grand old house standing out in the moonlight; he could see Mary, pale and silent, a dainty figure in white and amber. He saw Mayfield bend familiarly to her, and the girl draw coldly away. There was a fierce tumult in his heart, a desire to go back and proclaim his story. He could stretch out a hand, and put an end to all that without delay. But he preferred to wait. He was going to win Mary, and wear her like a white rose on the shield of a knight. He was going to bend down the barrier of her pride, and win her for himself alone, as himself, and not as a man who had the advantages of fortune on his side.

These thoughts filled his mind as he walked down the avenue. He knew that he had far to go before the goal was in sight. He almost walked over a figure standing just inside the lodge gates, and his thoughts came tumbling to earth again.

"I beg your pardon, Slight," he said. "I was miles away just now. Let us sit on this tree stump in sight of the old house and talk things over."

THE old man stood there in the moonlight, his face agitated and his lips quivering.

"I can hear the master's voice again," he murmured. "Time seems to have gone back with me. It is as if you had come like a ghost from the grave, Mr. Ralph. And it was close here that your father stood, after the great quarrel, and swore that Dashwood Hall should see him no more... And so you have come back to claim your own, sir?"

"I must be very like my father, or what my father was like forty years ago," Ralph said thoughtfully. "Sit down, Slight, please don't stand looking at me like that. I did not expect to be recognized in this way, and I am not here to claim my own, at least, not in the fashion that you mean. My father chose deliberately to forfeit his inheritance. My grandfather gave him the chance of coming into his own again. But he always refused, as you know, Slight. And now Sir George Dashwood reigns in his stead."

"The estate, the title—everything is yours, Sir Ralph," Slight said doggedly.

"No, no. Forty years ago there was a great upheaval here. It was a quarrel that could never be patched up or healed. At the bottom of it was family pride, the accursed kind of pride that stifles every feeling of humanity and turns hearts into flints as hard as the nether millstone. The upshot of that quarrel was a permanent separation between my grandfather and the present dowager Lady Dashwood; it drove my father into exile. It broke the heart of one of the best and truest women that ever lived. And all this to keep from so-called contamination the blood of the Dashwoods. Before my father went away he took steps to make his sacrifice complete. He executed a deed cutting off the entail of the estate, so that the late Sir Ralph could do what he pleased with it."

"I don't quite understand that, Sir Ralph," Slight said.

"Don't address me by that title," Darnley replied. "Let me explain. Most people believe that a family estate like ours cannot be left elsewhere. But if the heir likes to execute a deed for the purpose of cutting off the entail as it is called, why, the holder for the time being can do what he likes with the property. My father did this with his eyes wide open, and you witnessed the deed, Slight."

"I recollect it," Slight said slowly. He made the admission grudgingly. "It was my task to deliver it into the hands of old Sir Ralph. If I had only known!"

"You would have destroyed it. You would have carried your loyalty to my father so far. But the deed was delivered to my grandfather and subsequently he made his will. For twenty years there was silence between father and son, a silence which was broken at length by the father, who wrote to the son and asked him to return. Then Sir Ralph wrote once more to my father and said that he would give the latter twenty years to decide. He had made a will at the same date as that of the second letter, leaving everything to my father, provided that within twenty years of that date he claimed his patrimony. If the date passed, then everything was to go to the man nominated in that will. I need not say that the man so indicated was Sir George Dashwood. In other words, if I make no sign for six months, the property becomes his irrevocably. I can claim the property as my father's heir, and I can produce that will as proof of my claim."

"But the will was never found," Slight said eagerly. "We looked for a will everywhere."

"It was hidden away. In old Sir Ralph's last letter to my father he explained the hiding-place. I have only to let Sir George know where the will is, and he is safe. For the will directs the finder to the repository of the deed cutting off the entail, so that Sir George can prove his claim then to everything. At present he has no more than the income of the estate, and I have ascertained that he has many old debts to pay off. In addition to this he is under the thumb of a scoundrel."

"Ay, that he is," Slight muttered. "We servants learn a great deal more than you gentlemen give us credit for. That Mayfield means mischief. They say that he's rich. But riches don't content him. He wants to marry Miss Mary. And she can't bear the look of him. If only he can ruin Sir George, his path will be clear. Miss Mary would break her heart if she had to leave this place. From a child she was brought up here, she loves every stick and stone. And she was always led to believe that some day it would belong to her, because her father was the last of the old race, seeing that we all regarded Master Ralph as dead and buried. And Miss Mary had dreams of being mistress here some day, and, maybe, dreams, too, of a good husband and children of her own. Ay, it's a terrible weapon this Mayfield has in his hands."

"So it seems," Ralph replied. "I know the rascal well, for he ruined my father two years ago. Mind you, at that time, I had never heard of Dashwood Park. I was merely the son of a Mr. Darnley who had done well silver mining in California. Mayfield came to us in London and we trusted him, trusted him to such an extent that nearly all we had passed into his hands. It was only on his death-bed that my father told me everything, told me what my birthright was, and how I could secure it, if I did not wait too long. So I came down here to look about me, and to my surprise I found that I had met Miss Mary before in Paris. Is she a favourite here, Slight?"

"Ay, indeed she is, sir," Slight replied. There was a ring of passionate sincerity in his speech. "We all love her dearly. Strangers think that she is cold and distant. It may be so. But we all know the heart of gold that beats under that placid breast. It is in times of sickness and trouble that we know of the angel in our midst. I'm not denying that Miss Mary is tainted with the curse of family pride. But still... Ah, sir, if you ever looked out for a wife, why there is the very one for you. You the head, and she the mistress. It would be a happy day for me."

"That is just what I mean," Ralph said quietly. "Slight, I have been in love with your mistress for two long years. And I am going to marry her some day. But I have my own idea and my own way of leading up to that happiness. She must care for me for my own sake, and not because I am Sir Ralph Dashwood, of Dashwood Hall, and she a—pauper. No, no. My lady shall stoop to me, she shall tell me with her own sweet lips that a good man's love is worth all the pride of place, worth a dozen old families and a score of houses like this. Then she shall know everything, but not before."

"And that will be too late," sighed Slight. "Before that Mr. Mayfield will have ruined Sir George, and Miss Mary will marry him to save the old house. She would make any sacrifice and face any degradation for the sake of her pride. Though every fibre of her body may call out against the pollution of that man's touch, she would smile at him before the world and pretend to be happy. It's a dangerous experiment, Mr. Ralph, and don't you try it. I haven't lived in the world for nigh on four-score years for nothing. If you love Miss Mary, and if she comes to care for you, she'll care none the less because you are master of this good old place. And if her father is ruined——"

"My good Slight, her father is not going to be ruined. Unless I am greatly mistaken, he is exceedingly anxious to be rid of Horace Mayfield. I presume it is a mere matter of money, and for the sake of argument call it £50,000. Sir George owes Mayfield that sum. In the present circumstances he could not hope to repay it. A disgraceful bankruptcy may follow, a criminal collapse even, for Mayfield would not hesitate where his desires and interests are concerned. But suppose I could show Sir George a way to get this money? In that case he could rid himself of that scoundrel at any sacrifice. I have only to let Sir George know where the will is hidden and he is free."

"It would be wrong, sir, cruelly wrong to yourself," Slight cried. "You could never appear after that and claim your own. Sir George would be no more than an innocent impostor. And you, the real master of Dashwood, would be compelled to earn your bread."

"I don't see it exactly," Ralph smiled. "My father never intended to claim his inheritance. He cut himself off from England deliberately. And after all these years, would it not be a cruel thing to deprive Miss Mary of a home which she has come to regard as her own? But I have made up my mind, Slight, and nothing shall deter me from it. You may call me a visionary and a dreamer if you like, but my hands are strong and capable, and I have been taught to use my head. I want you to be discreet and silent; I want you to be my witness when the time comes. I should not have taken you into my confidence, but that you recognized me at once. All day I have been wandering about the dear old place. I have studied all its ancient beauties. We can't wonder that Miss Mary has come to regard it as part of her life. It has cost me more than a passing effort to restrain my covetousness."

Ralph stifled a sigh as he looked about him. He could see the fine old house clear cut against the sky; in the park the oaks and beeches hung like great sentinels guarding the home of the ages. And it was so still and peaceful, so suggestive of all that is worth having in life. A cry from somewhere broke the perfect silence, the bleat of a sheep from distant pastures.

"It shall be as you wish, sir," Slight said at length. "I could never refuse your father anything, and I can refuse you nothing when you look at me out of the past with his eyes. But sorrow and trouble will come of this; you mark my words."

"No, no," Ralph cried as he rose to his feet. "True and sterling happiness, the death and destruction of the family pride which has been our curse for many generations. I am going my own way to work and you are going to help me. Now come and show me the big window in the staircase that my father used when he wanted to leave the house late at night to visit poor Maria Edgerton, the child-wife, the child of the people, who was killed by our family pride as surely as if she had been murdered. My mother was a good woman, Slight, she had her husband's respect and affection, but his heart was always with the girl who suffered so much to become his wife. I hope that her grave has never been neglected, Slight."

"No, sir," Slight said huskily. "We have seen to that—her ladyship and myself between us. That is the window, sir, the big stained glass one with the light behind it. You can get up on to the leads with the aid of the ivy. At the bottom of the window is a brass knob. If you press it, the window opens inwards, and there you are. But I hope you don't need to burgle your own house, seeing that you are a welcome guest there. And, as I was saying just now——"

The speaker paused, for the soft, rich silence of the night was broken by a cry. The long drawing-room window leading to the lawn was still open; the lamplight flooded on pictures and china and flowers. A figure came to the window, a tall figure with upraised hands and hair wild and dishevelled.

"You scoundrel," the figure cried. "You have done this to ruin me!"

The speaker's tones rang out with passionate vehemence. He stumbled down the steps, into the garden, and repeated his accusation loudly. It all seemed strangely out of place there, Ralph thought; it was no spot for sordid emotions, and angry passions. The words rang clear and loud to the startled vault of heaven; a blackbird started from her nest and flew across the lawn with nervous twitter. Then another figure came from the drawing-room, the trim, immaculate figure of Horace Mayfield.

"For goodness' sake, control yourself Dashwood," he said curtly. "There is nothing in the world to make all this ridiculous fuss about. It is all the fortune of war. We tried to get the best of these fellows, and they looted us instead. It was no fault of mine that these cablegrams miscarried. My manager has sold me—a thing that sometimes happens in the City. All we have to do is to pay and look pleasant."

"But I can't pay, and you know it. Nobody understands the tenure on which I hold the property better than you do. If I wait for the money, what happens?"

"I am afraid it will be very awkward," Mayfield said. "People will refuse to believe that you have been a victim of a fraud. They will actually regard the fraud as your own. Whereas, if you pay up cheerfully, nothing can be said. Personally, I am all right. I kept my name out of the business so that you could have all the credit. Unfortunately, you will get all the blame as well. There may not be a prosecution; of course, it is not an easy matter to get the Public Prosecutor to interfere in these cases. The only thing for it is to take the bull by the horns and get out of all by paying."

Sir George laughed in a bitter kind of way. He stood with his back to the house, facing the man who had brought all this about. He seemed to be almost beside himself with fury. The whole man was transformed.

"I have no money," he said, "and you know it. You have deliberately brought me to this pass for purposes of your own. You have traded upon my love of gambling to get me into your hands. And I might have been happy and comfortable here. I was getting rid of my millstone of debt so nicely when you came along once more. But for you, I should not stand here now outside my own home, an honoured house for three centuries, a ruined and desperate man with a vision of a prisoner's dock before me. You are a rich man——"

"Possibly, Dashwood. At any rate, I am in a position to find money. But there is no kind of friendship or sentiment when one comes to business. You are not a child that you can accuse me of luring you to your ruin. Still, I am not disposed to take offence. I will undertake to settle the matter for you in time. But you must have a joint guarantee and I want another person to become security for you. You understand what I mean. If Miss Mary will be so good as to give me her word——"

A sudden cry of passion broke from the older man. He seemed to lose all control of himself. He dashed forward and smote Mayfield with fury on the mouth. The latter staggered back a thin streak of blood trickling from his under lip.

There was no outbreak, no display of passion, on the part of Mayfield. He was surprised and shaken by the impetuosity of the attack, but he stood there calmly, as he wiped the blood from his face. His features might have been carved out of solid marble, and the full light of the moon heightened the effect. In spite of his knowledge of the man, Ralph could not but admire him at that moment. One who could keep his feelings under such control would prove a dangerous foe.

It was a strange, weird scene altogether, terrible and repulsive by very force of contrast. The environment was so quiet and peaceful, so exalted and refined. Ralph stood as if rooted to the spot. He saw Sir George advance again, he saw the hand upraised once more. All the pride of rank and place had fallen from the man; he was transformed for the moment to a savage. Then Mayfield caught the uplifted arm and held it in a grip like a vice.

"You will gain nothing by this," he said quietly. "You seem to forget that I am a guest under your roof. Would you alarm your servants, would you have them know what their master is, when all his passions are aroused? Come, sir, this is not what one has a right to expect from the owner of Dashwood Park. You owe me an apology——"

The words were lost on Sir George. He wrenched himself free, he turned and faced the house with uplifted arms. The demon of anger still possessed him.

"I owe you nothing," he cried. "But for you I should be one of the happiest men alive. If I had been content to pay off old debts by degrees nothing would have happened. But I listened to you, with what result you know. You are a trickster and a cheat, a liar and a knave. You have laid a trap for me, and I have tumbled into it with my eyes open. What you mean to say in as many words is this—unless I can procure the sum of £50,000 in a few days I stand every chance of a criminal prosecution. You know exactly how I am situated, you know that I am helpless."

"You are not in the least helpless," Mayfield said sternly. "To a certain extent the fault is mine, and I am prepared to do all that is in my power. You have only to say the word and the money is yours. Promise me that your daughter shall become my wife, get her to say the word, and the situation is absolutely changed. I neither admit nor deny your accusations. You could not prove them—a jury would give a verdict against you, if you tried to do so. And if Miss Mary does me the honour to become my wife——"

"Never," Dashwood cried. "Never in this world. Our women only wed honourable men."

"Is that really so? And what manner of man will the world call you if I fail to come to your assistance? Control yourself—listen to me for a moment. Do you realise what will happen to you if I go away without coming to some understanding? The police will come here and arrest you, it may be when you are entertaining friends. They will take you away, with handcuffs on your wrists. You will stand in the dock charged with a vulgar conspiracy to defraud innocent shareholders, and the charge will be proved. And if you ever come out of gaol again, it will be as a broken and dispirited man. It will be useless, when it is too late, to look for any consideration from me, I am not likely to forget the blow you dealt me just now. And, whilst you are raving like a lunatic, we might be settling the matter comfortably over a cigar. You are a man of the world; at least you will be once more when this fit of midsummer madness has passed. Explain everything to your daughter if you like, put any face upon it that you please. Agree to my conditions and you can sleep in peace to-night, and every other night, for the matter of that. Listen to the voice of reason, and I will forget the treatment I have had at your hands."

But Sir George was not listening. Apparently a terrible struggle was going on in his breast. He could see now, how neatly and cleverly he had been trapped, he could see that he had no remedy against the man who had schemed for this position. And he was innocent himself of anything dishonourable. And now to give his daughter to this man! The mere idea was horrible. The meanest hound on the estate was far better off than Sir George at this moment.

"Do your worst," he shouted. His voice rang out on the startled silence. "Do your worst. If I could kill you now, I would do so. You are not fit to live, your presence is an insult to any honest man. I can see nothing, I am going blind..."

Sir George clasped his hands to his eyes; everything for the moment had faded from his sight. The blood was rushing wildly through his head; there was a din like the clang of hammers in his brain. He was beside himself with grief and passion. His voice uprose again and broke the stillness of the night horribly. What were his title and his old family worth now? It was all as nothing, in the presence of this threatened calamity.

"Mary, Mary," he cried, "come to me. Come, whilst I have the strength left to tell you the truth. To-morrow I shall be too weak, to-morrow I shall not dare to give all this up. Come, and tell him that you will have none of him."

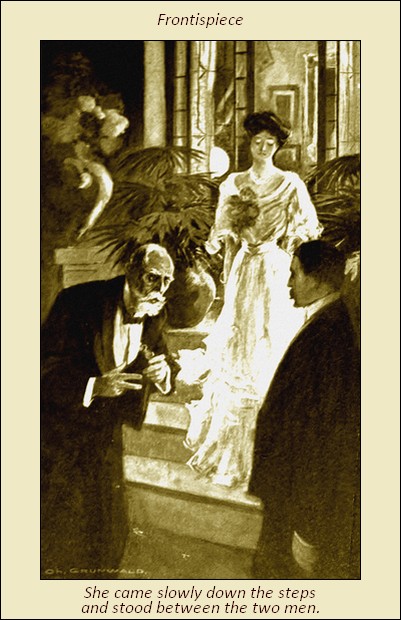

The speech ended in a yearning scream. It was a strange setting for so peaceful a scene. Ralph Darnley made a step forward, with the impulse to interfere, strong upon him. Then a figure came between the light and the window, and Mary appeared. She stood there, tall and stately in her white dress; her eyes were filled with stern disapproval. She came slowly down the steps and stood between the two men. She did not fail to notice Mayfield's cut lip and the spot or two of blood on his gleaming shirt front.

"What is the meaning of this?" she asked. "Father, you don't mean to say——"

"Ay, but I do," Dashwood said doggedly. "I struck him. Would that I had killed him! There would be far less disgrace for the family in the end. I struck him, and he took it quietly like the cur and craven that he is!"

"I hardly think that I deserve that," Mayfield said. "Whatever my failings may be, you will not find a lack of physical courage amongst them. Sir George has been very unfortunate in his speculations, and he chooses to blame me for it. We only got the news late to-night. A man in whom we trusted has played the knave, and Sir George is likely to suffer for it. To put the matter quite plainly, unless your father can find a very large sum of money in a few days he will probably be prosecuted. One can make any allowance for his feelings in the circumstances, but that is no reason why he should accuse one of deliberately laying a plot to ruin him. As to the assault upon me, why let it pass. In the excitement of the moment——"

"Pardon me," Mary said quietly, "I heard my name mentioned. My father's voice was raised so loudly that I could not help hearing something of what passed. You did me the honour to say that I might avert the catastrophe."

"That is so," Mayfield retorted in the same self-contained manner. "In certain circumstances I am prepared to stand by your father. I can say that it is a misunderstanding so far as he is concerned, and that I am prepared to take over the venture as it stands, and pay everybody who has lost confidence in it. I could write to the Press and vindicate the honour of the man who stood in the light of prospective father-in-law to me."

The girl's face whitened in the moonlight. Ralph could see the heaving of her breast. She had taken in the situation like a flash of inspiration. There was none of the grinning triumph of the successful rogue on Mayfield's face; it was all being quietly and decorously done, but the grip of iron was there all the same, the iron hand in the velvet glove. Mary essayed to speak, but words failed her for the moment. Sir George stood between the man and his prey with trembling hands outstretched as if to keep them apart. His lips opened, he gabbled something too incoherent for understanding, then he collapsed like a heap of black cloth on the grass. Something seemed to snap in his brain, then a blank came over him.

Mary forgot everything else in the dictates of humanity. With a cry she knelt on the grass by the side of the stricken man. Ralph came forward, slowly followed by Slight. It seemed natural that he should be there at that moment. Mary turned towards him instantly. Here was the friend in need that she so sorely prayed for.

"It is some kind of seizure," she said. "My father had one two years ago in Paris. He was warned then to avoid any undue excitement. Will you please help me to carry him to his room? Slight, call a groom up and send him to Longtown for a doctor."

"No occasion," Mayfield remarked. "Give me the key of the stables, and I will take my car into Longtown and bring the doctor back with me. It will take less time."

It was a weary two hours that passed before the doctor arrived. Still, his account was a fairly cheerful one when it came. It was merely a case of rest and quietness and careful nursing. Sir George had fallen into a kind of troubled sleep.

Ralph turned to go. Mayfield had volunteered to take the doctor home again. Slight was sitting with his master till Mary was ready to return. She stood by the window leading to the lawn; that means of exit was as good as any other, Ralph said.

"What were you doing outside to-night?" the girl asked keenly.

"We will go into that another time," Ralph suggested. "I did not mean to listen, but I heard everything. Did I not tell you that Mayfield was a villain?"

"I have felt it before now. Without any apparent cause for it, I have detested that man. And he has always acted as if he had only to say the word and I would consent to be his wife. On two occasions I have refused him. To think that men should be such villains where innocent girls are concerned! Of course, he has led my father into a terrible position, and my hand is to be the price of his freedom. Ralph, I am so dreadfully, horribly afraid of that man! How wonderfully he must have controlled himself when my father struck him! And how cleverly he insinuated that he might be allowed to appear as my future husband. I tell you I would give up everything to be free of this tangle. What is my pride, what is my home here, so long as the happiness of a lifetime is at stake!"

"That is a lesson that I have tried to teach you before," Ralph said quietly. "Mary, I love you. The time will come when you will love me. If ever you needed a friend in your life, you need one at this moment. I could show you a way out, but after that I should never dare to claim my reward, because the obligation in your eyes would be too great. I want you to care for me for my own sake. Still, you need have no anxiety. Within the next few hours Mayfield will be powerless to harm you."

"Ralph, you speak in enigmas. I pray you to be plain. Can't you trust me?"

"My dear, in this matter I cannot trust anybody; by Heaven, I can hardly trust myself. Ah, if you only knew how I love you and how great the temptation is! But the reward that I am working for will be all the sweeter when the time comes. Go sleep now with a calm mind, for I pledge my honour that things shall be as I say."

Mary's two hands had fluttered out to Ralph. She was moved by the deep sincerity of his words, for a broken smile, half respect and half affection, quivered on her face. With an impulse that he could not resist, Ralph drew the girl to him and laid his lips on hers. Then, with a sigh, he put her from him and turned towards the window.

"There," he said, "I ask no pardon for my audacity. I could not help it. And that kiss was as pure as if it came from your mother's lips."

"The first from any man," Mary murmured, a pink flush on her face. "You are a good man, Ralph, and it is a pity I did not meet you before the curse of the family pride fell upon me. Good night, and God bless you for all your kindness to me."

The window closed and the blind fell, the lights in the house began to vanish one by one, and still Ralph lingered there on the grass. He saw Mayfield return, he saw the last ray extinguished, save for the solitary glow in Sir George's bedroom. A clock over the stables struck the hour of two, and still Ralph stood there oblivious of the flight of time.

He was thinking of the dramatic scene of the evening. More than once he mourned his lost opportunities. He had all the strings in his own hand, the game was entirely his, and he felt, too, that in spite of her fateful pride, Mary was beginning to care for him. If not, why had she taken his kiss so sweetly? Ralph had only to proclaim his identity, he had merely to prove his title to the estate, and at once he would be in the position to free the present occupier of Dashwood Hall of his peril. And Mary would not refuse to marry the man whose blood was as pure as hers. But Ralph had made up his mind what to do. He would win her love as Ralph Darnley, afterwards the truth could be told. Why not to-night? he asked himself. There was no time like the present. He would go and find the will, he would let Sir George know where it was.

The house was still now, and Ralph knew the way... He was in the long corridor presently, here was the old oak dower-chest and the panel below it. Here was the spring by which the panel was released. The thing was ridiculously easy.

Ralph pressed in the spring and the panel came away. Within it was a long manuscript written on thick white paper. Ralph thrilled as he read the endorsement. Beyond doubt, here was the will of his grandfather, Sir Ralph Dashwood. All this was quite plain in the moonlight. It only needed now to put the will at the bottom of the dower-chest and write a letter to Sir George anonymously, and tell him where to seek for it. And Ralph had only to be silent henceforth, and the deception would pass for all time. Verily Mayfield's triumph was likely to be a very short one, and...

Somebody was speaking to Ralph: Mary, with her hair over her shoulders, and a candle in her hand. Her face was cold and set, her eyes filled with stern displeasure.

"Thief in the night," she said. "What is the meaning of this, Mr. Darnley?"

A sense of blinding, unreasonable anger held Ralph for the moment. He was doing nothing wrong. He was acting entirely for the best, and here he was taken under the most shameful conditions—a miserable, degraded thief in the night. From the coldness of Mary's voice, from the scorn in her eyes, he could read the reflection of her thoughts. And yet he was acting from the highest and most honourable motives. Surely no man was ever impelled by a loftier idea of self-sacrifice.

"I ask what you are doing," Mary repeated. "Do not tax my patience too far."

There was no mistaking the menace in those clearcut tones. Thus would the daughter of the house of Dashwood address a burglar or other midnight intruder. Ralph felt that she would have been not in the least afraid to face a felon of that type; his face tingled as he felt himself set down in the same category. He cudgelled his brains for some plausible explanation which should be anything but the right one. The edge of the failing moon still left a shaft of pallid light shining through the great stained glass window; it flung into high relief the arms and motto of the family of Dashwood. And those arms and that motto belonged to the man who stood there with the shamefaced air of a boy caught in a fault.

"I am still waiting for you to speak," Mary went on. "It is possible that there may be some explanation of this amazing conduct of yours."

The cold, proud voice seemed to doubt it all the same. And yet one word would have swept all the clouds of suspicion away. Ralph knew that it lay in his power to bring that white, haughty figure to her knees; one inkling of the truth and the whole situation was changed. For all this belonged to Ralph; Mary was no more than an honoured guest in the house. Yes, it all belonged to him, the grand old house, the matchless pictures, the furniture from the time of Elizabeth, the great sweeps of upland country, and the farms lying snug under their red roofs.

A few words spoken, and what a difference there would be! Those words meant that Ralph would have held out his hands and asked Mary to come and help him to reign here. Ay, and she would have come, too. Her point of view would be entirely changed. And she must love him. Indeed, he had more than a feeling that she loved him now, without being aware of the state of her affections. Her heart would go out to him, and there would be peace and happiness for evermore.

The temptation was great, so great that the beads of perspiration stood out on Ralph's forehead. But he crushed the temptation down; his pride came to his assistance. No, when Mary came to love, she should love the man for his own sake, she should tell him so, and Dashwood should be as nothing in comparison.

"I came here to look for something," Ralph said at length.

"Indeed! Judging by what you hold in your hand I should say that you have found it. How did you manage to obtain entrance to the house?"

"Quite a simple matter," Ralph replied. "I climbed on to the leads outside the big window. By pressing a knob outside, the window can be made to open."

"Really! I have lived here practically all my life, and I was not aware of that fact. For an absolute stranger, your knowledge of the house is exceedingly comprehensive. May I ask if you have found what you were looking for?"

"I have," Ralph said huskily. "Permit me to replace it in the old chest. To-morrow, if your father is well enough, I will see him and explain. I beg to assure you that I have what criminal lawyers call a perfect answer to the charge."

"And you ask me to believe this?" Mary burst out passionately. "How do I know that you are not one of those who are in league against us? How do I know that your indignation against Horace Mayfield is not all assumed?"

"How do you know that I am a gentleman?" Ralph retorted. "You cannot explain why."

"Indeed I cannot," Mary said bitterly. "I trusted you, I regarded you as a friend. I asked for your assistance and you promised it to me. In my heart I thanked God that I had a friend that I could rely upon. Actually, you caused me to forget the difference between our stations in life. And now!"

The girl paused, with something like tears in her voice. She looked very sweet and womanly at that moment, Ralph thought. He could afford to ignore the suggestion of the social gulf between them. The temptation to tell the truth came over him again, but once more he fought the impulse and conquered it.

"In spite of your distressful pride, you are a very woman," he said. "I am your friend and more than your friend. For your sake, there is nothing that I would not do. It is for your sake that I am here to-night, strange as it may seem. A little time ago, fate placed me in possession of certain information closely touching on the fortunes of your house. Please do not ask me to explain, for I cannot do so without spoiling everything. Call me a sentimentalist, if you like—perhaps the air of the grand old place has affected me. Anyway, there it is. I came here to-night to place you in possession of certain information that would for ever have rid you of the hateful presence of the man who calls himself Horace Mayfield. I did not want to place you under any kind of obligation, so I chose this method——"

"But why?" Mary exclaimed. "Why? Have you not saved my life twice? Could a million obligations like this increase the burden of my debt of gratitude to you?"

"That is right," Ralph admitted. "Call me a Quixote if you like. I am. The day will come when your eyes will be no longer blind, when love will come before everything. I have my own way of getting my ends, and am too proud to rely upon anything but myself. I am going to make you happy, and you are going to be the mainspring of that happiness."

Ralph spoke almost with the spirit of prophecy upon him. It would all come right some day, but he little dreamed of the trouble and tribulation that were near at hand. All he could see now was that Mary's eyes were growing dim and softer.

"My knowledge is going to save you," Ralph went on. "But I did not wish you to know that I had any hand in the business. As I said before, you must not ask me to explain. I want you to give me your hand, and to say that you regard me as being still beyond suspicion. Oh, I know that it is a deal to ask. But a long pedigree and the possession of a grand old house are not necessary to the honour of a man. I admit that I crept here like a thief in the night. If you charged me, I should have nothing to say, my character would be forever ruined. If you——"

Ralph paused, and his face flushed with annoyance. A petulant voice calling for Mary broke the silence—shuffling feet came along the corridor. Dishevelled and dazed. Sir George Dashwood stood there, candle in hand, looking from the glorious white figure with the rippling golden hair to the faint outline of Darnley. The old man was haggard and trembling, yet a certain dignity sustained him.

"I have called you three times," he said. "I needed you, my child. I woke up with my head better and a raging thirst upon me. Then I thought that I heard voices here and I came out. The situation, Mr. Darnley, is singular. Permit me to remind you that it is not the usual thing——"

The speaker paused. He seemed to be struggling for words to express his feelings.

"Quite so, Sir George," Ralph said eagerly. "I—came back for something. I helped you into the house after your illness overcame you. Forgive me if I seem to have stayed a little too long in my anxiety to be of assistance. If you will take my advice you will go back to your room without delay."

Sir George muttered something to the effect that he was very tired. He babbled about cool springs in the woods, he accepted Mary's arm as a weary child might do. It seemed almost impossible to believe that this was the sprightly, gallant figure that Ralph had known in Paris so short a time ago. But when Ralph had gone by the way in which he had come, and once more Sir George was in his bedroom, a change came over him. He eagerly drank the soda-water that Mary had procured for him.

"No, no," he cried, "tired as I am, I cannot sleep yet. I was half asleep, I was between waking and dreaming, and I was dying of thirst. I came out into the corridor and saw you standing there with Ralph Darnley. There were certain words that seemed to be burned into my brain with letters of fire. You were angry with him, and yet he was going to be a friend to us. That was no common thief in the night, Mary. What was it he found? What was it that was going to rid us of the hateful presence of Horace Mayfield? Don't tell me that I was dreaming, don't say that it was all a cruel delusion on my part. The secret, the secret, girl."

The words came like a torrent. Out of his white and hazard face, Dashwood's eyes gleamed like restless stars on a windy night. The clutch on the girl's arm was almost painful in its intensity. Mary wondered why she was trembling so.

"Hush," she said. "You must sleep now, or you will be really ill again. Leave it till the morning, when you will be better able to understand. I cannot tell you now; indeed, I know no more than you do yourself. But now you must go to sleep!"

Sir George lay back on the bed with weary eyelids closed. His last effort had cost him more than he knew. Mary's will had conquered for the moment, and he felt disposed to obey. All the same the strange thread of logical reason was going on in his mind. The only thing that could save him and preserve the proud traditions of the Dashwoods must be something in the way of papers or documents of some kind. He lay there, allowing Mary to make him comfortable for the night. He lay there long after the girl had departed to her own room and the house was wrapped in close slumber. But the quietness was soothing to Sir George's brain. His mind was growing stronger and more logical; the dazed dream of the scene in the corridor began to shape itself into concrete facts.

What had Ralph Darnley been saying? Yes, it was all coming back now. Darnley had learned certain facts somewhere, bearing on the fortunes of the house of Dashwood. Surely there was nothing so wildly improbable in this, seeing that Ralph Darnley had passed the best part of his life in America. The late Ralph Dashwood, the original heir to the property, had lived in America, too. Of course, America was a large continent, but that was no reason why Ralph Dashwood and Darnley's father should not have been friends. Had not Ralph Darnley admitted that he had business in the neighbourhood of Dashwood Hall? Perhaps he had come to make money out of his information. But then the young fellow was a gentleman, and would not stoop to that kind of thing.

Still, he knew there was no getting away from the fact, for had not Dashwood heard it from the younger man's lips? A means whereby it was possible to get rid of Horace Mayfield for ever! The mere idea sent the blood throbbing through the sick man's veins, and brought him in a sitting position in bed. That meant documents or papers of some kind; it could really mean nothing else. Dashwood remembered vividly now that Ralph had been standing by the old dower-chest in the corridor and that he had had a paper in his hand. So far as Dashwood knew, the old chest had not been opened for years. It was by no means a bad hiding-place. Perhaps——

Slowly the sick man dragged himself to his feet. He had promised Mary that he would lie quietly there till the morning, but he could not find it in his heart to keep that promise. Sleep was out of the question. Dashwood looked at his watch to find that it was only just half-past three, five hours before it would be time to rise. It seemed like an eternity. And all the while that fiend, Horace Mayfield, was sleeping under the same roof. Suppose he had been listening to what was going on. Suppose that he had had his suspicions attracted to the dower-chest! The mere thought was intolerable; it was impossible to lie there with such a torture praying on his mind. And the house was as still as death.

Sir George lighted his candle, though the bright summer dawn was creeping up from the east and the birds were beginning to twitter outside in the garden. The long corridor was getting pink and saffron with the strengthening colour from the great window. And under it lay the object of the sick man's search. Here it was with the lid unfastened and a mass of papers on the top. The first document was long in shape, neatly folded, and bearing an endorsement in a legal hand. The paper was yellow and faded, but the ink was quite plain for the eye to read. Yes, here it was, right enough, the yellow paper that meant happiness to all and the full splendour of the house of Dashwood.

"How did he know, how did he discover it?" Sir George muttered. "My hands are so shaky that I can hardly hold the paper. The will of Sir Ralph Dashwood, dated 1877, and duly witnessed by the family lawyer and his clerk... Provided that for the space of twenty years after this date my son Ralph does not appear either by himself or by the heir or heirs male of his body... Ah, six months more and the property comes to me absolutely! Strange that the will should come to light so near to the time appointed by Sir Ralph for—but that hardly helps me, seeing that my danger is so close at hand... What is this? A deed executed by Ralph Dashwood the younger cutting off the entail... I wonder where that is? Perhaps the yellow sheet of parchment lying by the side of the will... By Heavens it is! Oh, this is a direct interposition of Providence to save the good old name from disgrace. And this is what Ralph Darnley was looking for as a pleasant surprise for me. Armed with these documents, I can raise all the money necessary. I can kick Horace Mayfield out of the house, I can——"

The speaker staggered to his feet and pressed his hands to his throbbing, reeling head.

He was nearer to collapse again than he knew. He would have denied the fact that he was terribly afraid of Mayfield, but it was true all the same. The aim of the financier had never been quite hidden from his eyes; for some time past he had an instinctive knowledge of what Mayfield was after. His family pride had bidden him to have no more of Mayfield, but he had not listened. Proud as he was, he had not hesitated to stoop to gambling transactions, with the risk that he would not be able to pay his debts if he lost. Surely he deserved a sharp lesson and a cruel awakening.

But he was free now, fortune was on his side. His great good luck sent him trembling from head to foot like some amazed criminal who has been discharged by a stupid jury. He would have to give up nothing. He was still Sir George Dashwood with a grand estate, and a house with a history of three hundred years behind it. He would go to London to-morrow with those papers in his possession and his bankers would be ready to accommodate him to any amount in reason. He would pay the sum that Mayfield had mentioned, and wash his hands of the whole transaction. He would show the world how a country gentleman deals with these things. It never struck Dashwood that he was a feeble creature who had juggled with the good name that he proposed to hold so highly; he little realized the deep self-abnegation that had led to this dazzling piece of good fortune.

"Kick Mayfield out," he repeated, "after breakfast. Let him see that I am not in the least afraid of him; make him understand that we are little better than strangers for the future. Ah, that will be a triumph."

He hugged the papers to his breast, like a mother with a child. There were weak and senile tears in his eyes. He had lost nothing after all; the fine old house, the wide and well-kept estate, the great timber in the park and the deer there, were all his. He started as the sound of a footstep fell upon his ears. It seemed to him that somebody was creeping along the corridor. Perhaps it was Mayfield, who had found out what had happened. Mayfield was strong and unscrupulous, and he might try to gain possession of those papers by force. Sir George would have hidden himself, but it was too late, and besides it was broad daylight now.

The first rays of the morning sun shone on the old man as he stood there huddling those precious papers to his breast. He might have been some clumsy thief detected in the act. With a sigh of relief he recognized the figure of Slight coming in his direction. The old butler only looked a shade less distracted than his master, and his eyes were drawn and haggard; obviously he had not been to bed.

"What—what are you doing here?" Sir George stammered. "Why are you spying upon me like this? Why are you down so early?"

Slight made no reply. His gaze was fixed in a dazed kind of way on the papers which Sir George was still hugging to his breast. There was something like horror in the old man's eyes. There might have been the proofs of murder there.

"So you've got them," he said in the voice of one who talks to himself. "So he has carried out his threat and they have passed into your possession. Take and burn them, take and pitch them on the fire, and watch them till the last ash has vanished. You will be a happier man for it, Sir George, and a great wrong will be averted."

"What does the man mean?" Sir George cried in astonishment. "Slight, what are you talking about? Say it all over again. If you are mad or drunk——"

"Not mad," Slight said mournfully. He seemed to have come to his senses suddenly. He spoke now as one does when acting under a great restraint. "Not mad, Sir George, and as to the other thing, why... But the secret is not mine. I promised solemnly not to open my lips. I have given you the best advice one man can give another, but more I dare not say. Burn them, burn them, burn them, for the love of Heaven!"

Slight turned away and seemed to totter down the corridor. The full light of the strong morning sun was shining through the gold and crimson glories of the great stained glass window now, the birds were singing sweetly outside. The park grew fair and green as the dew rolled back across the fields; the garden blazed in the sunshine. Sir George saw all this as he looked through his bedroom window. The fierce joy and pride of undisputed possession were upon him; everything was safe now.

"Slight is mad," he murmured. "What does that old man know? What can he know? Let me put these papers away where they will be safe. How shaky I feel; how my head swims! If I could only get an hour or two of sleep...."

The big clock on the breakfast-room mantelpiece was chiming the hour of ten as Sir George came downstairs. He was a little later than usual, and he apologized to his guest for his want of punctuality with a courtly air. He was not accustomed to country hours, he said; he doubted if he ever should be. He made no allusion whatever to his last night's quarrel, his manner was perfectly natural and easy. If anything, there was a suggestion of bland patronage in his tone.

Mayfield glanced keenly at his host from time to time. There was something here that he quite failed to understand. He had expected to find Sir George apologetic and rather frightened. On the contrary, he was more like a bishop who entertains a curate than anything else. And Mayfield could get nothing from Mary, who sat at the head of the table, cold and stately, yet serenely beautiful, in her white cotton dress. Mayfield ground his teeth together and swore that Dashwood should pay for this before long. He held the fortunes of the baronet in the hollow of his hand; his passion for Mary was the more inflamed by her icy coldness. It would be good to humble her pride in the dust, to compel her to come to his feet and do his bidding. All the same, Mayfield had made up his mind to have an explanation after breakfast. He smiled and talked, though his anger was hot within him.

"Mr. Mayfield will want a time-table presently, my dear," Sir George was saying in his most courtly manner. "I am afraid that we have intruded too long already on his valuable time."

"I have always time to spare for you," Mayfield said with a snarling smile. "And Miss Mary need not trouble about the time-table. You forget that I have my car here which will get me to London by mid-day. Before I go I should like to have a few words with you, Sir George. You will pardon me for mentioning it, but we left matters in rather an unsatisfactory condition last night."

The little shaft passed harmlessly over Sir George's head. He smiled blandly.

"To be sure we did," he said. "You are quite right, we will settle things up before you go. What do you say to a cigar on the terrace after breakfast? No, you need not go, Mary. I have a reason for asking you to listen to our business conversation. We had a quarrel last night, when I regret to say I lost my temper. For that exhibition of unseemly and vulgar violence I sincerely beg your pardon, Mayfield. I apologize all the more humbly because we are not likely to meet very often in the future. Henceforth our business transactions promise to be slender, for after this week I am determined that the City shall not see me again. You will quite see, Mayfield, that in future our intercourse must cease. It is rather painful to talk to a guest like this, but you will understand me."

Mayfield's face expressed his astonishment. He wondered if Sir George had taken leave of his senses, and deluded himself into the belief that he was the possessor of a vast fortune. And yet the speaker was absolutely calm and collected. What could possibly have happened since last night to change him like this?

"Perhaps I am rather dense this morning," Mayfield said slowly, "but I cannot follow you at all. Yesterday I explained to you the position of affairs fully. We had been deceived by a trusted servant of mine, and you were called upon to pay £50,000. Failing this, you would perhaps have to face a criminal charge. Unfortunately, your hold upon the estate is so slender that it would not be possible for you to borrow any large sum of money. Not to speak too plainly, your position was, and is, a desperate one. Partly because I was in a measure instrumental in bringing about this lamentable state of affairs, I offered to advance you the money. In other words, I offered to give you £50,000. It is true there was a condition, but I merely allude to that in the presence of Miss Dashwood."