|

I - Without A Friend II - A Desperate Venture III - On Guard IV - The Warning Light V - Deeper Still VI - The Peril Speaks VII - "Uneasy Lies The Head..." VIII - The Very Man IX - "Pongo" X - A Friend At Court XI - In The Garden XII - A Prodigal Son XIII - The Modern Journalist XIV - Baffled! XV - The Search XVI - Was It Russia? XVII - A Bow At A Venture XVIII - Watching XIX - The Quest Of The Papers XX - A Special Effort XXI - "Forewarned, Forearmed" XXII - The Trail Grows XXIII - General Maxgregor XXIV - At The Window XXV - An Unexpected Honour |

XXVI - Loyal Silence XXVII - Lechmere To The Rescue XXVIII - The Power Of The Press XXIX - In Maxgregor's Chambers XXX - Her Friend, The Queen XXXI - A Surprise For Jessie XXXII - No Time To Lose XXXIII - The Fish On The Line XXXIV - A Royal Actor XXXV - A Race For The Throne XXXVI - Annette Tells A Story XXXVII - Cross Purposes XXXVIII - On Broken Ground XXXIX - In The Camp Of The Foe XL - Thin Ice XLI - Annette At Bay XLII - The Countess Returns XLIII - In Search Of The King XLIV - Dead! XLV - Check! XLVI - Mate In Two Moves XLVII - The Situation Is Saved XLVIII - The Papers At Last XLIX - Love And Roses |

The girl stood there fighting hard to keep back the tears from her eyes. The blow had been so swift, so unexpected. And there was the hurt to her pride also.

"Do I understand that I am dismissed, Madame?" Jessie Harcourt asked quietly. "You mean that I am to go at the end of the week?"

The little woman with the faded fair hair and the silly affectation of fashion was understood to say that Miss Harcourt would go at once. The proprietress of the fashionable millinery establishment in Bond-street chose to call herself Madame Malmaison though she was London to the core. Her shrill voice shook a little as she spoke.

"You are a disgrace to the establishment," she said. "I am sorry you ever came here. It is fortunate for me that Princess Mazaroff took the propel view so far as I am concerned. Your conduct was infamous, outrageous. You go to the Princess to try on hats for her Highness and what happens? You are found in the library engaged in a bold flirtation with her Highness's son, Prince Boris. Romping together! You suffered him to kiss you. When the Princess came here just now and told me the story, I was—"

"It is a lie," Jessie burst out passionately. "A cowardly lie on the part of a coward. Why did not that Russian cad tell the truth? He came into the drawing room where I was waiting for the Princess. Don't interrupt me, I must speak, I tell you."

Madame Malmaison subsided before the splendid fury of Jessie's anger. She looked more like a countess than a shop girl as she stood there with her beautiful eyes blazing, the flash of sorrow on her lovely face. Madame Malmaison had always been a little proud of the beauty and grace and sweetness of her fitter-on. Perhaps she felt in her heart of hearts that the girl was telling the truth.

"I hope I am a lady," Jessie said a little more gently—"at any rate, I try to remember that I was born one. And I am telling the truth—not that it matters much, seeing that you would send us all into the gutter rather than offend a customer like the Princess. That coward said his mother was waiting for me in the library. He would show me the way. Then he caught me in his arms and tried to kiss me. He wanted me to go to some theatre with him to-night. He was too strong for me. I thought I should have died of shame. Then the Princess came in and all the anger was for me. And that coward stood by and shirked the blame; he let it pass that I had actually followed him into the library."

The girl was telling the truth, it was stamped on every word that she said. Madame Malmaison knew it also, but the hard look on her greedy face did not soften.

"You are wasting my time," she said. "The Princess naturally prefers her version of the story, and she has demanded your instant dismissal. You must go."

Jessie said no more. There was proud satisfaction in the fact that she had conquered her tears. She moved back to the splendid showroom with its Persian carpets and Louis Seize furniture as if nothing had happened. She had an idea that Madame Malmaison believed her, and that the latter would be discreet enough to keep the story from the other hands. And Jessie had no friends there. She could not quite bring herself to be friendly with the others. She had not forgotten the days when Colonel Harcourt's daughter had mixed with the class of people whom she now served. Bitterly Jessie regretted that she had ever taken up this kind of life.

But unhappily there had been no help for it. Careless, easy going Colonel Harcourt had not troubled much about the education of his two girls and when the crash came and he died, they were totally unfitted to cope with the world. The younger girl, Ada was very delicate, and so Jessie had to cast about to make a living for the two. The next six months had been a horror.

It was in sheer desperation that Jessie had offered her services to Madame Malmaison. Here was the ideal fitter-on that that shrewd lady required. She was prepared to give a whole two guineas a week for Jessie's assistance and the bargain was complete.

"Well, it was all over, anyway, now," Jessie told herself. She was dismissed and that without a character. It would be in vain for her to apply to other fashionable establishments of the kind unless she was prepared to give some satisfactory reason for leaving Madame Malmaison. Her beauty and grace and charm would count for nothing with rival managers. The bitter, hopeless, weary struggle was going to begin all over again. The two girls were utterly friendless in London. In all the tragedy of life there is nothing more sad and pathetic than that.

Jessie conquered the feeling of despair for the moment. She had all her things to arrange; she had to tell the girl under her that she was leaving for good to-night. She had had a dispute with Madame Malmaison, she explained and she would not return in the morning. Jessie was surprised at the steadiness of her own voice is she gave the explanation. But her cold fingers trembled, and the tears were very heavy in the beautiful eyes. Jessie was praying for six o'clock now.

Mechanically she went about her work. She did not heed or hear the chatter of her companions; she did not see that somebody had handed her a note. Somebody said that there was no answer, and Jessie merely nodded. In the same dull way she opened the letter. She saw that the paper was good; she saw that the envelope bore her name. There was no address on the letter, which Jessie read twice before having the most remote idea of its meaning.

A most extraordinary letter, Jessie decided when at length she had fixed her mind into its usual channel. She read it again in the light of the sunshine. There was no heading, no signature.

"I am writing to ask you a great favour (the letter ran). I should have seen you and explained, but there was no time. If you have any heart and feeling you cannot disregard this appeal. But you will not ignore it, however, because you are as good and kind as you are beautiful. The happiness of a distressed and miserable woman is in your hands. Will you help me?

"But you will help me, I am certain. Come to 17 Gordon Gardens, to-night at half-past 9 o'clock. Come plainly dressed in black, and take care to wear a thick black veil. Say that you are the young person from Forder's in Piccadilly, and that you have called about the dress. That is all that I ask you to do for the present. Then you will see me, and I can explain matters fully. Dare I mention money in connection with this case? If that tempts you, why the price is your own—500 pounds, 1000 pounds await you it you are bold and resolute."

There was nothing more; no kind of clue to the identity of the writer. Jessie wondered if it were some mistake; but her name was most plainly written on the envelope. It bad been left by a district messenger boy, so that there was no way of finding out anything. Jessie wondered if she had been made the victim of some cruel hoax. Visions of a decoy rose before her eyes.

And yet there was no mistake about the address. Gordon Gardens was one of the finest and most fashionable squares in the West End of London. Jessie fluttered over the leaves of the London Directory. There was Gordon Gardens right enough—Lady Merehaven. The name was quite familiar to her, though the lady in question was not a customer of Madame Malmaison's. All this looked very genuine, so also did the letter with the passionate, pleading tone behind the somewhat severe restraint of it all. Jessie had made up her mind.

She would go. Trouble and disappointment had not soured the nobility of her nature. She was ready as ever to hold out a helping hand to those in distress. And she was bold and resolute too. Moreover, as she told herself with a blush, she was not altogether indifferent to the money. Only a few shillings stood between her and Ada and absolute starvation. 500 pounds sounded like a fortune.

"I'll go," Jessie told herself. "I'll see this thing to the bitter end, whatever the adventure may lead to. Unless, of course, it is something wrong or dishonest. But I don't think that the writer of the letter means that. And perhaps I shall make a friend. God knows I need one."

The closing hour came, and Jessie went her way. At the corner of New Bond-street a man stood before her, and bowed with an air of suggested politeness. He had the unmistakable air of the life debonaire; he was well dressed, and handsome in a picturesque way. But the mouth under the close-cropped beard was hard and sensual; the eyes had that in them that always fills the heart of a girl with disgust.

"I have been waiting for you," the man said. "You see, I know your habits. I am afraid you are angry with me."

"I am not angry with you at all," Jessie said, coldly. "You are not worth it, Prince Boris. A Man who could play the contemptible cur as you played it this morning—"

"But, ma cherie, what could I do? Madame la Princess, my mother, holds the purse-strings. I am in disfavour the most utter and absolute. If my mother comes to your establishment and says—"

"The Princess has already been. She has told her version of the story. No doubt she heartily believes that she has been told the truth. I have been made out to be a scullery girl romping with the page boy. My word was as nothing against so valuable a client as the Princess. I am discharged without a character."

Prince Boris stammered something, but the cruel light of triumph in his eyes belied his words. Jessie's anger flamed up passionately. "Stand aside and let me pass," she said: "and never dare to address me again. If you do, I will appeal to the first decent man who passes, and say you have grossly insulted me. I have a small consolation in the knowledge that you are not an Englishman."

The man drew back abashed, perhaps ashamed, for his dark face flushed. He made no attempt to detain Jessie, who passed down the street with her cheeks flaming. She went on at length until she came to one of the smaller byways lending out of Oxford-street, and here, before a shabby-looking house, she stopped and let herself in with a latchkey. In a bare little room at the top of the house a girl was busy painting. She was a smaller edition of Jessie, and more frail and delicate. But the same pluck and spirit were there in Ada Harcourt.

"What a colour!" the younger girl cried. "And yet—Jessie, what has happened? Tell me."

The story was told—indeed, there was no help for it. Then Jessie produced her mysterious letter. The trouble was forgotten for the time being. The whole thing was so vague and mysterious, and moreover there was the promise of salvation behind it. Ada flung her paint brush aside hastily.

"You will go?" she cried. "With an address like that there can be no danger. I am perfectly certain that that is a genuine letter, Jess, and the writer is in some desperate bitter trouble. We have too many of those troubles of our own to ignore the cry of help from another. And there is the money. It seems a horrible thing, but the money is a sore temptation."

Jessie nodded thoughtfully. She smiled, too, as she noted Ada's flushed, eager face.

"I am going," she said. "I have quite made up my mind to that. I am going if only to keep my mind from dwelling on other things. Besides, that letter appeals to me. It seems to be my duty. And as you say, there is the money to take into consideration. And yet I blush even to think of it."

Ada rose and walked excitedly about the room. The adventure appealed to her. Usually in the stories it was the men only to whom these exciting incidents happened. And here was a chance for a mere woman to distinguish herself. And Jessie, would do it, too, Ada felt certain. She had all the courage and resolution of her race.

"It's perfectly splendid!" Ada cried. "I feel that the change of out fortunes is at hand. You are going to make powerful friends, Jessie; we shall come into our own again. And when you have married the prince, I hope you will give me a room under the palace roof to paint in. But you must not start on your adventure without any supper."

Punctual to the moment Jessie turned into Gordon Gardens. Her heart was beating a little faster now; she half felt inclined to turn back and abandon the enterprise altogether. But then such a course would have been cowardly, and the girl was certainly not that. Besides, there was the ever unceasing grizzly spectre of poverty dangling before Jessie's eyes. She must go on.

Here was No. 17 at length—a fine, double fronted house, the big doors of which stood open, giving a glimpse of the wealth and luxury beyond. Across the pavement, to her surprise, Jessie noticed that a breadth of crimson cloth had been unrolled. The girl had expected to find the house still and quiet, and here were evidences of social festivities. Inside the hall two big footmen lounged in the vestibule; a row of hats testified to the fact that there were guests here to dinner. A door opened somewhere, and a butler emerged with a tray in his hand.

As the door opened there was a pungent smell of tobacco smoke, followed by a bass roll of laughter. Many people were evidently dining there. Jessie felt that she needed all her courage now.

It was only for a moment that the girl hesitated. She was afraid to trust her own voice: the great lump in her throat refused to be swallowed. Then she walked up the scarlet-covered steps and knocked at the door. One of the big footmen strolled across and asked her her business.

"I am the young person from Forder's, in Piccadilly," Jessie said, with a firmness that surprised herself. "I was asked by letter to come here at this hour to-night."

"Something about a dress?" the footman asked flippantly. "I'll send and see."

A moment later and the lady's maid was inviting Jessie up the stairs. As requested, the girl had dressed herself in black; she wore a black sailor hat with a dark veil. Except in her carriage and the striking lines of her figure, she was the young person of the better class millionaire's shop to the life. She came at length to a dressing-room, which was evidently about to be used by somebody of importance. The dressing-room was large and most luxuriously fitted; the contents of a silver-mounted dressing-bag were scattered over the table between the big cheval glasses; on a couch a ball dress had been spread out. Jessie began to understand what was going on—there had been a big dinner party, doubtless to be followed presently by an equally big reception. One of the blinds had not been quite drawn, and in the garden beyond Jessie could see hundreds of twinkling fairy lamps. The adventure was beginning to appeal to her now; she was looking forward to it with zeal and eagerness.

"My mistress will come to you in a moment," the maid said, in the tone of one who speaks to an equal. "Only don't let her keep you any longer than you can help. The sooner you are done the sooner I shall be able to finish and get out. Good night!"

The maid flitted away without shutting the door. Jessie's spirits rose as she looked about her. There could be no possible chance of personal danger here. Jessie would have liked to have raised her veil to get a better view of all these lovely things that would appeal to a feminine mind, but she reflected that the black veil had been strongly insisted upon.

A voice came from somewhere, a voice asking somebody also in a whisper to put the lights out. This command was repeated presently in a hurried way, and Jessie realised that the voice was addressing her. Without a minute's hesitation she crossed over to the door and flicked out the lights. Well, the adventure was beginning now in real earnest, Jessie told herself. The voices whispered something further, and then in the corridor Jessie saw something that rooted her to the spot. In perfect darkness herself, she could look boldly out into the light beyond. She saw the figure of a man half led and half carried between two women—one of them being in evening dress. The man's face was as white as death. He was either very ill or very near to death, Jessie could see; his eyes were closed, and he dragged his limbs after him like one in the last stage of paralysis. One of the ladies in evening dress was elderly, her hair quite gray; the other was young and handsome, with a commanding presence. On her hair she wore a tiara of diamonds, only usually affected by those of royal blood. She looked every inch a queen, Jessie thought, as with her strong gleaming arms she hurried the stricken man along. And yet there was a furtive air about the pair that Jessie did not understand at all.

The phantom passed away quietly as it had come, like a dream; the trio vanished, and close by somebody was closing a bedroom door gently, as if fearful of being overheard. Jessie rubbed her eyes as if to make sure that the whole thing had not been a delusion. She was still pondering over that strange scene in a modern house, when there came the quick swish of drapery along the corridor, and somebody flashed into the room and closed and locked the door. That somebody was a woman, as the trail of skirts testified, but Jessie rose instantly to the attitude of self.

She had not long to wait, for suddenly the lights flashed up, and a girl in simple evening dress stood there looking at Jessie. There was a placid smile on her face, though her features were very white and quivering.

"How good of you!" she said. "God only knows how good of you. Will you please take off your hat, and I will.......? Thank you. Now stand side by side with me before the glass. Is not that strange. Miss Harcourt? Do you see the likeness?"

Jessie gasped. Side by side in the glass she was looking at the very image of herself!

"The likeness is wonderful," Jessie cried. "How did you find out? Did anybody tell you? But you have not mentioned your own name yet, though you know who I am."

The other girl smiled. Jessie liked the look of her face. It was a little haughty like her own, but the smile was very sweet, the features resolute and strong just now. Both the girls seemed to feel the strangeness of the situation. It was as if each was actually seeing herself for the first time. Then Jessie's new friend began to speak.

"It is like this," she exclaimed. "I am Vera Galloway, and Lady Merehaven is my aunt. As my aunt and my uncle, Lord Merehaven, have no children, they have more or less adopted me. I have been very happy here until quite lately, until the danger came not only to my adopted parents, but to one whom I love better than all the world. I cannot tell you what it is now, I have no time. But the danger to this house and Charles—I mean my lover—is terrible. Fate has made it necessary that I should be quite free for the next few hours, free to escape the eyes of suspicious people, and yet at the same time it is necessary that I should be here. My dear Miss Harcourt, you are going to take my place."

"My dear Miss Galloway, the thing is impossible," Jessie cried. "Believe me. I would help you if I could—anything that requires courage or determination. I am so desperately placed that I would do anything for money. But to take your place—"

"Why not? You are a lady, you are accustomed to society. Lord Merehaven you will probably not see all the evening, Lady Merehaven is quite short-sighted. And she never expects me to help to entertain her guests. There will be a mob of people here presently, and there is safety in numbers. A little tact, a little watchful discretion, and the thing is done."

Vera Galloway spoke rapidly and with a passionate entreaty in her voice. Her beautiful face was very earnest. Jessie felt that she was giving way already.

"I might manage it," she admitted dubiously. "But how did you come to hear of me?"

"My cousin, Ronald Hope, told me. Ronald knew your people in the old days. Do you recollect him?"

Jessie blushed slightly. She recollected Captain Hope perfectly well. And deep down in her heart she had a feeling that, if things had turned out differently, she and Ronald Hope had been a little more than mere acquaintances by this time. But when the crash came, Jessie hart put the Captain resolutely aside with her other friends.

"Well, Ronald told me," Vera Galloway went on. "I fancy Ronald admired you. He often mentioned your name to me, and spoke of the strange likeness between us. He would have found you if he could. Then out of curiosity I asked a man called Beryll, who is a noted gossip, what had become of Colonel Hacker Harcourt's daughters, and he said one of them was in a milliner's shop in Bond-street, he believed Madame Malmaison's. Mind you, I was only mildly curious to see you. But to-day the brooding trouble came, and I was at my wits' end for a way out. Then the scheme suddenly came to me, and I called at Malmaison's this morning with a message for a friend. You did not see me, but I saw you. My mind was made up at once, hence my note to you....And now I am sure that you are going to help me."

"I am going to help you to do anything you require," Jessie said, "because I feel sure that I am on the side of a good cause."

"I swear it," Vera said with a passionate emphasis. "For the honour of a noble house, for the reputation of the man I love. And you shall never regret it, never. You shall leave that hateful business for ever....But come this way—there are many things that I have to show you."

Jessie followed obediently into the corridor a little behind Vera, and in the attitude of one who feels and admits her great social inferiority. They came at length to a large double window opening on to some leads, and then descending by a flight of steps to the garden. The thing was safer than at first appeared, for there were roll shutters to the windows.

It was very quiet and still in the garden, with its close-shaven lawns and the clinging scent of the roses. The silent parterre would be gay with a giddy, chattering mob of society people before long, Vera hurriedly explained. Lady Merehaven was giving a great reception, following a diplomatic dinner to the foreign Legation by Lord Merehaven. Jessie had forgotten for the moment that Lord Merehaven was Secretary for Foreign Affairs.

The big windows at the back of the dining room were open to the garden; the room was one blaze of light that flickered over old silver and priceless glass on banks of flowers and red wines in Bohemian decanters. A score or more men were there, all of them distinguished with stars and ribbons and collars. Very rapidly Vera picked them out one by one. Jessie felt just a little bewildered as great, familiar names tripped off the tongue of her companion. A strange position for one who only a few hours before had been a shopgirl.

"We will walk back through the house," Vera Galloway said. "I must show you my aunt. Some of the guests are beginning to arrive, I see. Come this way."

Already a knot of well-dressed women filled the hall. Coming down the stairs was the magnificent woman with the diamond tiara, the woman who had helped along the corridor the man with the helpless limbs. Jessie elevated her eyebrows as the great lady passed.

"The Queen of Asturia," Vera whispered. "You have forgotten to lower your veil. Yes, the Queen of Asturia. She has been dining here alone with my aunt in her private room. You have seen her before?"

"Yes," Jessie replied. "It was just now. Somebody whispered to me to put out the lights. As I sat in the dark I saw—; but I don't want to appear inquisitive."

"Oh, I know. It was I who called to you from my bedroom to put the lights out. I had no wish for that strange scene on the stairs to be.....you understand?"

"And the sick man? He is one whose name I ought to know, perhaps."

"Well, yes. Whisper—come close, so that nobody can hear. That was the King of Asturia. You think he was ill. Nothing of the kind. Mark you, the Queen of Asturia is the best of women. She is good and kind—she is a patriot to her finger tips. And he—the king—is one of the greatest scoundrels in Europe. In a way, it is because of him that you are here to-night. The whole dreadful complication is rooted in a throne. And that scoundrel has brought it all about. Don't ask me more, for the secret is not wholly mine."

All this Vera Galloway vouchsafed in a thrilling whisper. Jessie was feeling more and more bewildered. But she was not going back on her promise now. The strange scene she had witnessed in the corridor came again to her with fresh force now. The ruler of Asturia might be a scoundrel, but he certainly was a scoundrel who was sick unto death.

"We will go back to my room now," Vera said. "First let me dismiss my maid, saying that I have decided not to change my dress. Go up the stairs as if I had sent you for something. You will see how necessary it is to get my maid out of the way."

The bedroom door was locked again, and Vera proceeded to strip off her dress, asking Jessie to do the same. In a little time the girls were transformed. The matter of the hair was a difficulty, but it was accomplished presently. A little while later and Jessie stood before the glass wondering if some other soul had taken possession of her body. On the other hand, Vera Galloway was transformed into a demure-looking shop assistant waiting a customer's orders.

"I declare that nobody will know the difference," she said. "Unless you are in a very strong light, it will be impossible to detect the imposture. You will stay here and play my part, and I shall slip away disguised in my clothes. Is that ten o'clock striking? I must fly. I have one or two little things to get from my bedroom. Meanwhile, you can study those few points for instruction that I have written on this sheet of paper. Study them carefully, because one or two of them really are of importance."

Vera was back again in a moment, and ready to depart. The drama was about to begin in earnest, and Jessie felt her heart beating a little faster. As the two passed down the stairs together, they could see that the handsome suite of rooms on the first floor were rapidly filling. One or two guests nodded to Jessie, and she forced a smile in reply. It was confusing to be recognised like this without knowing who the other people were. Jessie began to realise the full magnitude of the task before her.

"I am not in the least satisfied with your explanation," she said, in a very fair imitation of Vera Galloway's voice. After all, there is a great sameness in the society tones of a woman. "I am very sorry to trouble you as the hour is late, but I must have it back to-night. Bannister, whatever time this young person comes back, see that she is not sent away, and ask her in to the little morning room. And send for me."

The big footman bowed and Vera Galloway slipped into the street. Not only had she got away safely, but she had also achieved a way for a safe return. Jessie wondered what was the meaning of all this secrecy and clever by-play. Surely there must be more than one keen eye watching the movements of Vera Galloway. The knowledge thrilled Jessie, for if those keen eyes were about they would be turned just as intently upon her. A strange man came up to her and held out his hand. He wanted to know if Miss Galloway enjoyed the Sheringhams' dance last night. Jessie shrugged her shoulders, and replied that the dance was about as enjoyable as most of that class of thing. She was on her guard now, and resolved to be careful. One step might spoil everything and lead to an exposure, the consequences of which were altogether too terrible to contemplate.

The strange man was followed by others; then a pretty fair girl fluttered up to Jessie and kissed her, with the whispered question as to whether there was going to be any bridge or not. Would Vera go and find Amy Macklin and Connie, and bring them over to the other side of the room? With a nod and a smile Jessie slipped away, resolving that she would give the fair girl a wide berth for the remainder of the evening. In an amused kind of way she wondered what Amy and Connie were like. It looked as if the evening were going to be a long series of evasions. There was a flutter in the great saloon presently, as the hostess came into the room, presently followed by the stately lady with the diamond tiara in her hair.

The guests were bowing right and left. Presently the Queen of Asturia was escorted to a seat, and the little thrill of excitement passed off. Jessie hoped to find that it would be all right, but a new terror was added to the situation. She, the shop-girl, was actually in the presence of a real queen, perhaps the most romantic figure in Europe at the present moment. Jessie recalled all the strange stories she had heard of the ruling house of Asturia, of its intrigues and fiery conspiracies. She was thinking of it still, despite the fact that a great diva was singing, and accompanied on the piano by a pianist whose reputation was as great as her own. A slim-waisted attache crossed the room and bowed before Jessie, bringing his heels together with a click after the most approved court military fashion.

"Pardon me the rudeness, Mademoiselle Vera, but her Highness would speak to you. When you meet the princess, the lady on the left of the queen will vacate her chair. It is to look as natural as possible."

Jessie expressed her delight at the honour. But her heart was beating more painfully just now than it had done any time during the evening. The thing was so staggering and unexpected. Was it possible that the queen knew of the deception, and was party to the plot? But the theory was impossible. A royal guest could not be privy to such a trick upon her hostess.

With her head in a whirl but her senses quite alert, Jessie crossed the room. As she came close to the queen, a lady-in-waiting rose up quite casually and moved away, and Jessie slipped into the vacant seat. She could see now how lined and wearisome behind the smiles was the face of the Queen of Asturia. And yet it was one of the most beautiful faces in the world.

"You are not surprised that I have sent for you, cherie?" the queen asked.

"No, Madame," Jessie replied. She hoped that the epithet was correct. "If there is anything that I can do—"

"Dear child, there is something you can do presently," the queen went on. "We have managed to save him to-night. You know who I mean. But the danger is just as terribly imminent as it was last night. Of course, you know that General Maxgregor is coming here presently?"

"I suppose so," Jessie murmured. "At least, it would not surprise me. You see, Madame—"

"Of course it would not surprise you. How strangely you speak to-night. Those who are watching us cannot possibly deduct anything from the presence of General Maxgregor at your aunt's reception. When he comes you are to attach yourself to him. Take him into the garden. Then go up those steps leading to the corridor and shut the general in the sitting-room next to your dressing-room—the next room to where he is, in fact. And when that is done come to me, and in a loud voice ask me to come and see the pictures that you spoke of. Then I shall be able to see the general in private. Then, you can wait in the garden by the fountain till one or both of us comes down again. I want you to understand this quite clearly for heaven only knows how carefully I am watched."

Jessie murmured respectfully that she knew everything. All the same, she was quite at a loss to know how she was to identify General Maxgregor when he did come. The mystery of the whole thing was becoming more and more bewildering. Clearly Vera Galloway was deep in the confidence of the queen, and yet at the same time she had carefully concealed from her majesty the fact that she had substituted a perfect stranger for herself. It was a daring trick to play upon so exalted a personage, but Vera had not hesitated to do it. And Jessie felt that Vera Galloway was all for the cause of the queen.

"I will be in wait for the general," she said. "There is no time to be lost—I had better go now."

Jessie rose and bowed and went her way. So far, everything had gone quite smoothly. But it was a painful shock on reaching the hall to see Prince Boris Mazaroff bending over a very pretty girl who was daintily eating an ice there. Just for a moment it seemed to Jessie that she must be discovered. Then she reflected that in her party dress and with her hair so elaborately arranged, she would present to the eyes of the Russian nothing more than a strange likeness to the Bond-street shopgirl. At any rate, it would be necessary to take the risk. The prince was too deep in his flirtation to see anybody at present.

Once more Jessie breathed freely. She would linger here in the hall until General Maxgregor came. He would be announced on his entrance, so that Jessie would have to ask no questions. Some little time elapsed before a big man with a fine, resolute face came into the hall.

Somebody whispered the name of Maxgregor, and Jessie looked up eagerly. The man's name had a foreign flavour—his uniform undoubtedly was; and yet Jessie felt quite sure that she was looking at the face of an Englishman. She had almost forgotten her part for the moment, when the general turned eagerly to her.

"I'll go upstairs presently," he murmured. "You understand how imperative it is that I should see the queen without delay. It is all arranged, of course. Does the queen know?"

"The queen knows everything, General," Jessie said. She felt on quite firm ground now. "Let us stroll into the garden as if we were looking for somebody. Then I will admit you to the room where the queen will meet you presently. Yes, that is a very fine specimen of a Romney."

The last words were uttered aloud. Once in the garden the two hurried on up the steps of the corridor. From a distance came the divine notes of the diva uplifted in some passionate love song. At another time Jessie would have found the music enchanting. As it was, she hurried back to the salon and made her way to the queen's side. One glance and a word were sufficient.

The song died away in a hurricane of applause. The queen rose and laid her hand on Jessie's arm. She was going to have a look at the pictures, she said. In a languid way, and as if life was altogether too fatiguing, she walked down the stairs. But once in the garden her manner altogether changed.

"You managed it?" she demanded. "You succeeded. Is the general in the room next to your sitting-room? How wonderfully quick and clever you are! Would that I had a few more like you near me! Throw that black cloak on the deck chair yonder over my head and shoulders. Now show me the way yourself. And when you have done, go and stand by the fountain yonder, so as to keep the coast clear. When you see two quick flashes of light in the window you will know that I am coming down again."

Very quietly the flight of steps was mounted and the corridor entered. With a sign Jessie indicated the room where General Maxgregor was waiting for the queen; the door opened, there was a stifled, strangled cry, and the door was closed as softly as it had opened. With a heart beating unspeakably fast, Jessie made her way into the garden again and stood by the side of the ornamental fountain as if she were enjoying the cooling breezes of the night.

On the whole, she was enjoying the adventure. But she wanted to think. Everybody was still in the house listening to the divine notes of the great singer, so that it was possible to snatch a half breathing space. And Jessie felt that she wanted it. She tried to see her way through; she was thinking it out when the sound of a footstep behind caused her to look round. She gave a sudden gasp, and then she appeared to be deeply interested in the gold fish in the fountain.

"I hope he won't address me. I hope he will pass without recognition," was Jessie's prayer.

For the man strolling directly toward the fountain was Prince Boris Mazaroff!

Here was a danger that Jessie had not expected. She was not surprised to see Prince Boris Mazaroff there; indeed, she would not have been surprised at anything after the events of the last few hours. There was no startling coincidence in the presence of the Russian here, seeing that he know everybody worth knowing in London, and all society would be here presently.

Would he come forward and speak? Jessie wondered. She would have avoided the man, but then it seemed to be quite understood that she must stay by the fountain till the signal was given. All this had been evidently carefully thought out before Vera Galloway found it an imperative necessity to be elsewhere on this fateful night.

Would Mazaroff penetrate her disguise? Was the most fateful question that Jessie asked herself. Of course he would see the strong likeness between the sham Vera and the milliner in the Bond-street shop; but as he appeared to be au fait of Lord Merehaven's house, and presumably know Vera, he had doubtless noticed the likeness before. Jessie recollected the girls who had greeted her so smilingly in the hall, and reflected that they must have known Vera far better than this rascally Russian could have done, and they had been utterly deceived.

Mazaroff lounged up to the fountain and murmured something polite. His manner was easy and polished and courteous now, but that it could be very different Jessie knew to her cost. She raised her eyes and looked the man coldly in the face. She determined to know once for all whether he guessed anything or not. But the expression of his face expressed nothing but a sense of disappointment.

"Why do you frown at me like that, Miss Vera?" he asked. "What have I done?"

Jessie forced a smile to her lips. She could not quite forget her own ego, and she knew this man to be a scoundrel and a coward. Through his fault she had come very close to starvation. But, she reflected, certainly Vera could know nothing of this, and she must act exactly as Vera would have done. Jessie wanted all her wits for the coming struggle.

"Did I frown?" she laughed. "If I did, it was certainly not at you. My thoughts—"

"Let me guess your thoughts," Mazaroff said in a low tone of voice. He reclined his elbows on the lip of the fountain so that his face was close to Jessie's. "I am rather good at that kind of thing. You are thinking that the queen did not care much for the pictures."

Jessie repressed a start. There was a distinct menace in the speaker's words. If they meant anything they meant danger, and that to the people whose interests it was Jessie's to guard. And she knew one thing that Vera Galloway could not possibly know—this man was a scoundrel.

"You are too subtle for me," she said. "What queen do you allude to?"

"There was only one queen in this conversation. I mean the Queen of Asturia. She left the salon with you to look at certain pictures, and she was disappointed. Where is she?"

"Back again in the salon by this time, doubtless," Jessie laughed. "I am not quite at home in the presence of royalty."

The brows of Mazaroff knitted into a frown. Evidently Jessie had accidentally said something that checkmated him for a moment.

"And the king?" he asked. "Do you know anything about him? Where is he, for example?"

Jessie shook her head. She was treading on dangerous ground now, and it behoved her to be careful. The smallest possible word might lead to mischief.

"The queen is a great friend of mine," Mazaroff went on, and Jessie knew instantly that he was lying. "She is in danger, as you may possibly know. You shake your head, but you could tell a great deal if you chose. But then the niece of a diplomatist knows the value of silence."

"The niece of a diplomatist learns a great deal," Jessie said coldly.

"Exactly. I hope I have not offended you. But certain things are public property. It is impossible for a crowned head to disguise his vices. That the King of Asturia is a hopeless drunkard and a gambler is known to everyone. He has exhausted his private credit, and his sullen subjects will not help him any more from the public funds. It is four years since the man came to the throne, and he has not been crowned yet. His weakness and rascalities are Russia's opportunity."

"As a good and patriotic Russian, you should be glad of that," Jessie said.

"You area very clever young lady," Mazaroff smiled. "As a Russian, my country naturally comes first. But then I am exceedingly liberal in my political views, and that is why the Czar prefers that I should more or less live in Western Europe. In regard to the Asturian policy, I do not hold with the views of my imperial master at all. At the risk of being called a traitor, I am going to help the queen. She is a great friend of yours also."

"I would do anything in my power to help her," Jessie said guardedly.

The Russian's eyes gleamed. In a moment of excitement he laid his hand on Jessie's arm. The touch filled her with disgust, but she endured it.

"Then you never had a better opportunity than you have at the present moment," Mazaroff whispered. "I have private information which the queen must know at once. Believe me, I am actuated only by the purest of motives. The fact that I am practically an exile from my native land shows where my sympathies lie. I am sick to death of this Russian earth hunger. I know that in the end it will spell ruin and revolution and the breaking up of the State. I can save Asturia, too."

"Do I understand that you want to see the queen?" Jessie asked.

"That is it," was the eager response. "The queen and the king. I expected to find him elsewhere. I have been looking for him in one of the haunts he frequents. I know that Charles Maxwell was with him this morning. Did he give you any hint as to the true state of affairs?"

"I don't know who you mean?" Jessie said unguardedly. "The name is not familiar to me."

"Oh, this is absurd!" Mazaroff said with some show of anger in his voice. "Caution is one thing, but to deny knowledge of Lord Merehaven's private and confidential secretary is another matter. Come, this is pique—a mere lovers' quarrel, or something of that kind."

Jessie recovered herself at once. If Mazaroff had not been so angry he could not have possibly overlooked so serious a slip on the part of his companion.

"It is very good of you to couple our names together like this," Jessie said coldly.

"But, my dear young lady, it is not I who do it," Mazaroff protested. "Everybody says so. You said nothing when Miss Maitland taxed you with it at the Duke's on Friday night. Lady Merehaven shrugs her shoulders, and says that worse things might happen. If Maxwell were to come up at this moment—"

Jessie waved the suggestion aside haughtily. This information was exceedingly valuable, but at the same time it involved a possible new danger. If this Charles Maxwell did come up—but Jessie did not care to think of that. She half turned so that Mazaroff could not see the expression of her face; she wanted time to regain control over her features. As she looked towards the house she saw twice the quick flash of light in one of the bedroom windows.

It was the signal that the queen was ready to return to the salon again. Jessie's duty was plain. It was to hurry back to the bedroom and attend to the good pleasure of the queen. And yet she could not do it with the man by her side; she could think of no pretext to get rid of him. It was not as if he had been a friend. Mazaroff was an enemy of the heads of Asturia. Possibly he knew a great deal more than he cared to say. There had been a distinct menace in his tone when he asked how the queen had enjoyed the pictures. As Jessie's brain flashed rapidly over the events of the evening, she recalled to mind the spectacle of the queen and the strange lady who dragged the body of the helpless man between them. What if that man were the King of Asturia! Why, Vera Galloway had said so!

Jessie felt certain of it—certain that for some reasons certain people were not to know that the King of Asturia was under Lord Merehaven's roof, and this fellow was trying to extract valuable information from her. As she glanced round once more the signal flashed out again. For all Jessie knew to the contrary, time might be as valuable as a crown of diamonds. But it was quite impossible to move so long as Mazaroff was there.

She looked round for some avenue of escape. The garden was deserted still, for the concert in the salon was not yet quite over. Even here the glorious voice of the prima donna floated clear as a silver bell. The singer was flinging aloft the stirring refrain of some patriotic melody.

"The Asturian National Anthem," Mazaroff said softly. "Inspiring, isn't it?"

Jessie could feel rather than see that the signal was flashing out again, She looked about her for some assistance. In the distance a man came from the direction of the house. In the semi-darkness he paused to light a cigarette, and the reflection of the match shone on his face. Jessie started, and her face flushed. It seemed as if the stars were fighting for her to-night. She recognised the dark, irregular features behind the glow of the match. She had made up her mind what to do. Surely the queen would understand that there was cause for delay that some unforeseen danger threatened.

The man with the cigarette strolled close by the fountain. He had his hands behind him, and appeared to be plunged in thought. He would have passed the fountain altogether without seeing the two standing there, only Jessie called to him to stop in a clear gay voice.

"Have you lost anything, Captain Hope?" she asked. "Won't you come and tell us what it is?"

Jessie's voice was perfectly steady, but her heart was beating to suffocation now. For Vera's cousin, Captain Ronald Hope, was perfectly well known to her in her own private capacity as Jessie Harcourt. Hope had been a frequent visitor at her father's house in the old days, and Jessie had had her dreams. Had he not inspired Vera's daring scheme? Hope had not forgotten her, though she had elected to disappear and leave no sign, the girl knew full well; for had not Hope told Vera Galloway of the marvellous likeness between herself and Jessie Harcourt?

It was a critical moment. That Hope had cared for her Jessie well knew, though she sternly told her heart that it was not to be. Would he recognise her and penetrate her disguise? If the eyes of love are blind in some ways they make up for it in others.

Jessie's heart seemed to stand still as Hope raised his crushed hat and came leisurely up the steps of the fountain.

"I was looking for my lost and wasted youth. Miss Galloway," he said. "How are you, Prince? What a night!"

"A night for lovers," Mazaroff said, though Jessie could see that he was terribly annoyed at the interruption of their conversation. "Reminds one of birds and nightingales and rose bowers. Positively, I think of the days when I used to send valentines and love tokens to my many sweethearts."

"And what does it remind you of, Captain Hope?" Jessie asked.

"You always remind me of my friend Jessie Harcourt," Hope said. "The more I see of you, the more I see the likeness."

"The little shopgirl in Bond-street," Mazaroff burst out. "I have met her. Ah, yes."

"We are waiting for Captain Hope to tell us what the evening reminds him of," Jessie said, hurriedly.

"Certainly," Captain Hope said. "Afterwards I may want to ask Prince Mazaroff a question. This reminds me of a night three years ago—a night in a lovely lane with the moon rising at the end of it. Of course, there was a man and a woman in the lane, and they talked of the future. They picked some flowers, so as to be in tune with the picture. They picked dog roses—"

"'Your heart and mine' played out with the petals," Jessie laughed. "Do you know the other form of blowing the seed from a dandelion, only you use rose petals instead?"

There was a swift change on the face of Captain Hope. His face paled under the healthy tan as he looked quickly at Jessie. Their eyes met just for a moment—there was a flash of understanding between them. Mazaroff saw nothing, for he was lighting a cigar by the lip of the fountain. Jessie broke into some nonsense, only it was quite uncertain if she knew what she was saying. She appealed to Mazaroff, and as she did so she knocked the cigar that he had laid on the edge of the fountain so that it rolled down the steps on to the grass.

"How excessively clumsy of me!" Jessie cried. "Let me get it back for you. Prince Boris."

With a smile Prince Mazaroff proceeded to regain his cigar. Quick as a flash Ronald Hope turned to Jessie.

"What is it you want?" he asked. "What am I to do to help you? Only say the word."

"Get rid of that man," Jessie panted. "I can't explain now. Only got rid of that man and see that he is kept out of the way for at least ten minutes. Then you can return to me if you like."

Hope nodded. He appeared to have grasped the situation. With some commonplace on his lips he passed leisurely towards the house. Before Mazaroff could take up the broken threads of the subject a young man, who might have been in the diplomatic service, came hurrying to the spot.

"I have been looking everywhere for you, Prince Boris," he said.' "Lord Merehaven would like to say a few words to you. I am very sorry to detain you but this is a matter of importance."

Mazaroff's teeth flashed in a grin which was not a grin of pleasure. He had no suspicion that this had been all arranged in the brief moment that he was looking for his cigar, the thing seemed genuine and spontaneous. With one word to the effect that he would be back again in a moment, he followed the secretary.

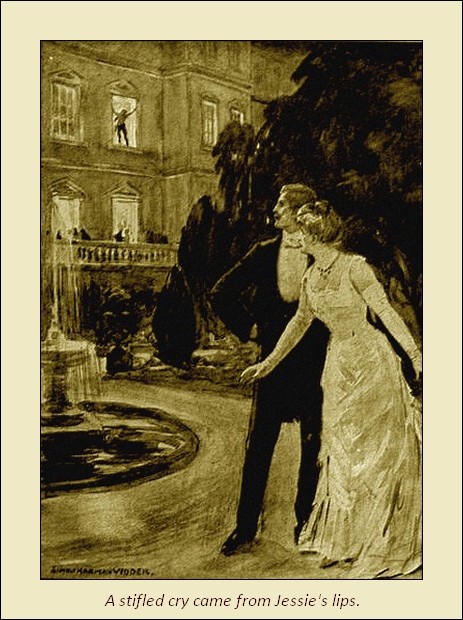

Jessie had a little time to breathe at last. She looked round her eagerly, but the signal was not given again. Ought she not to fly up the stops of the corridor? the girl asked herself. As she looked up again at the now darkened window the light came up for a moment, and the figure of a man, recognisable as that of General Maxgregor, stood out in high relief. The head of the figure was shaken twice, and the light vanished again. Jessie could make nothing of it except that she was not to hurry. Whilst she was still waiting and wondering what to do, Captain Ronald Hope returned. His face was stern, but at the same time there was a tender light in his eyes that told Jessie not to fear.

"What is the meaning of it all?" he asked. "I never had such a surprise in my life. When you spoke about our old sweetheart pastime of your heart and mine played with the petals of the wild rose, I recognised you for Jessie Harcourt at once, because we invented that game and the understanding was that we were never to tell anybody else. Oh, yes, I see that you are my dear little Jessie now."

The tender words thrilled Jessie. She spoke with an unsteady smile on her lips.

"But you did not recognise me till I gave you a clue," she said. "Are you very angry with me, Ronald?"

"I meant to be if ever I found you," Hope said. "I am going to be stern. I was going to ask you why you had—"

"Dear Ronald you had no right to speak like that. Great friends as we used to be—"

"Oh, yes, I know what you are going to say. Great friends as we were I had never told you that I loved you. But you knew it perfectly well without any mere words of mine; your heart told you so. Though I have never kissed you—never so much as had my arm about your waist—we knew all the time. And I meant to wait till after my long stay in Ireland. Then your father died, and you were penniless, and you disappeared. My dearest girl why did you not tell me?"

"Because you were poor Ronald. Because I did not want to stand between you and your career. Ada and myself were as proud as we were penniless. And I thought that you would soon forget."

"Forget! Impossible to forget you, Jessie. I am not that kind of man. I came here frequently because I was trying to get a diplomatic appointment, through my friend General Maxgregor, in the Asturian service, where there is both trouble and danger and the chance of a future. And every time that I saw Vera Galloway my heart seemed to ache for the sight of you. I told her about you often. Now tell me, why did your pride break down so suddenly to-night? You might have passed for Vera had you not spoken about the roses."

"I had the most pressing need of your assistance," Jessie said hoarsely. "I did not want to disclose myself, but conscience called me imperatively. I dare say you are wondering why I am masquerading here as Miss Galloway, and where she is gone. I cannot tell you. She only found me out to-day, and implored me to come to her and take her place. My decision to do so was not free from sordid consideration. I played my part with success till that scoundrel Mazaroff came along. At present I am in attendance on the Queen of Asturia, who is in one of the rooms overhead with General Maxgregor and a helpless paralytic creature who is no less than the King of Asturia. If you ask me about this mystery I cannot tell you. The whole thing was fixed up in a desperate hurry, and here I am. It was necessary to got Prince Mazaroff out of the way so that the Queen could return without being seen. I should not be surprised to find that Mazaroff was no more than a vulgar Russian spy after all."

"I feel pretty well convinced of it," Hope said. "But how long is this to go on, Jessie?"

"Till Miss Galloway comes back dressed in the fashion of the Bond-street shopgirl. Then we shall change dresses, and I shall be free to depart."

Hope whispered something sweet, and the colour came to Jessie's cheeks. She was feeling resolute and brave enough now. As she turned and glanced at the upstairs window she saw the light spring up and the blind pulled aside. Then a man, stripped to his shirt and trousers, threw up the window and stood upon the parapet waving his arms wildly and gesticulating the while. A stifled cry came from Jessie's lips. If the man fell to the ground he would fall on the stone terrace and be killed on the spot.

But he did not fall; somebody gripped him from behind, the window was shut, and the blind fell. There was darkness for a few seconds, and then the two flashes of the signal came once more, sharp and imperative.

Puzzled, vaguely alarmed, and nervous as she was. Jessie had been still more deeply thrilled could she have seen into the room from whence the signal came. She had escorted the Queen of Asturia there, and subsequently the man known as General Maxgregor, but why they came and why that secret meeting Jessie did not know.

In some vague way Jessie connected the mystery with the hapless creature whom she knew now to be the King of Asturia. Nor was she far wrong. In the dressing-room beyond the larger room where that strange interview was to take place the hapless man lay on a bed. He might have been dead, so silent was he and so still his breathing. He lay there in his evening dress, but there was nothing about him to speak of his exalted rank. He wore no collar or star or any decoration; he might have been no more than a drunken waiter tossed contemptuously out of the way to lie in a sodden sleep till the effects of his potations passed.

The sleeper was small of size and mean of face, the weak lips hidden with a ragged red moustache; a thin crop of the same flame-coloured hair was on his head. In fine contrast stood the Queen of Asturia, regally beautiful, perfectly dressed, and flashing with diamonds. There was every inch of a queen. But her face was bitter and hard, her dark eyes flashed.

"And to think that I am passing my life in peril, ruining my health and shattering my nerves for a creature like that," she whispered vehemently. "A cowardly, dishonest, drunken hog—a man who is prepared to sacrifice his crown for money to spend on wine and cards. Nay, the crown may be sold by this time for all I know."

The figure on the bed stirred just a little. With a look of intense loathing the Queen bent down and laid her head on the sleeper's breast. It seemed to her that the heart was not moving.

"He must not die," she said, passionately. "He must not die—yet. And yet, God help me, I should be the happier for his release. The weary struggle would be over, and I could sleep without the fear of being murdered before my eyes. Oh, why does not Paul come?"

The words came as if in protest against the speaker's helplessness. Almost immediately there came a gentle tap at the door, and General Maxgregor entered. A low, fierce cry of delight came from the Queen; she held out a pair of hands that trembled to the newcomer. There was a flush on her beautiful face now, a look of pleasure in the splendid eyes. She was more like a girl welcoming her lover than a Queen awaiting the arrival of a servant.

"I began to be afraid, Paul," she said. "You are so very late that I—"

Paul Maxgregor held the trembling hands in a strong grasp. There was something in his glance that caused the Queen to lower her eyes and her face to flush hotly. It was not the first time that a soldier had aspired to share a throne. There was more than one tradition in the berserker Scotch family to bear out the truth of it. The Maxgregors of Glen had helped to make European history before now, and Paul Maxgregor was not the softest of his race.

Generally he passed for an Asturian, for he spoke the language perfectly, having been in the service of that turbulent State for the last twenty odd years. There was always fighting in the Balkans, and the pay had attracted Paul Maxgregor in his earliest days. But though his loyalty had never been called in question, he was still a Briton to the backbone.

"I could not come before, Margaret," he said. "There were other matters. But why did you bring him here? Surely Lord Merehaven does not know that our beloved ruler—"

"He doesn't, Paul. But I had to be here and play my part. And there came news that the King was in some gambling house with a troupe of that arch fiend's spies. The police helped me, and I dragged him out and I brought him here by way of the garden. Vera Galloway did the rest. I dared not leave that man behind me, I dared not trust a single servant I possess. So I smuggled the King here and I sent for you. He is very near to death to-night."

"Let him die!" Paul Maxgregor cried. "Let the carrion perish. Then you can seat yourself on the throne of Asturia, and I will see that you don't want for a following."

The Queen looked up with a mournful smile on her face. There was one friend here whom she could trust, and she knew it well. Her hands were still held by those of Maxgregor.

"You are too impetuous, Paul," she said softly. "I know that you are devoted to me, that you—you love me—"

"I love you with my whole heart and soul, sweetheart," Maxgregor whispered. "I have loved you since the day you came down from your father's castle in the hills to wed the drunken rascal who lies there heedless of his peril. The Maxgregors have ever been rash where their affections were concerned. And even before you became Erno's bride I warned you what to expect. I would have taken you off then and there and married you, even though I had lost my career and all Europe would have talked of the scandal. But your mind was fixed upon saving Asturia from Russia, and you refused. Not because you did not love me—"

The queen smiled faintly. This handsome, impetuous, headstrong soldier spoke no more than the truth. And she was only a friendless, desperate woman after all.

"I must go on, Paul," she said. "My duty lies plainly before me. Suppose Erno dies? He may die to-night. And if he does, what will happen? As sure as you and I stand at this moment here, Russia will produce some document purporting to be signed by the king. The forgery will be a clever one, but it will be a forgery all the same. It will be proved that Erno has sold his country, the money will be traced to him, and Russia will take possession of those Southern passes. This information comes from a sure hand. And if Russia can make out a case like this, Europe will not interfere. Spies everywhere will make out that I had a hand in the business, and all my work will be in vain. Think of it, Paul—put your own feelings aside for a moment. Erno must not die."

Maxgregor paced up and down the room with long, impatient strides. The pleading voice of the queen had touched him. When he spoke again his tone was calmer.

"You are right," he said. "Your sense of duty and honour make me ashamed. Mind you, were the king to die I should be glad. I would take you out of the turmoil of all this, and you would be happy for the first time in your life. We are wasting valuable time. See here."

As Maxgregor spoke he took a white package from his pocket and tore off the paper. Two small bottles were disclosed. The General drew the cork from one of them.

"I got this from Dr. Salerno—I could not find Dr. Varney," he explained—"and as for our distinguished drunkard—he takes one. The other is to be administered drop by drop every ten minutes. Salerno told me that the next orgie like this was pretty sure to be fatal. He said he had made the remedy strong."

The smaller bottle was opened, and Maxgregor proceeded to raise the head of the sleeping figure. He tilted up the phial and poured the contents down the sleeper's throat. He coughed and gurgled, but he managed to swallow it down. Then there was a faint pulsation of the rigid limbs, the white, mean face took on a tinge as if the blood were flowing again. Presently a pair of bloodshot eyes were opened and looked dully round the room. The king sat up and shuddered.

"What have you given me?" he asked fretfully. "My mouth is on fire. Fetch me champagne, brandy, anything that tastes of drink. What are you staring at, fool? Don't you see him over there? He's got a knife in his hand—he's all dressed in red. He's after me!"

With a yell the unhappy man sprang from the bed and flew to the window. The spring blind shot up and the casement was forced back before Maxgregor could interfere. Another moment and the madman would have been smashed on the flagstones below. With something that sounded like an oath Maxgregor dashed forward only just in time. His strong hands reached the drink-soddened maniac back, the casement was shut down, but in the heat and excitement of the moment the blind remained up, so that it was just possible from the terrace at the end of the garden to see into the room.

But this Maxgregor had not time to notice. He had the ruler of Asturia back on the bed now, weak and helpless and almost collapsed after his outburst of violence. The delusion of the red figure with the knife had passed for a moment, and the king's eyes were closed. Yet his heart was beating now, and he bore something like the semblance of a man.

"And to think that on a wretch like that the fate of the kingdom hangs," Maxgregor said sadly. "You can leave him to me, Margaret, for the time being. Your absence will be noticed by Mazaroff and the rest. Give the signal...Why doesn't that girl come?"

But the signal was repeated twice with no sign of the sham Miss Galloway.

The two conspirators exchanged uneasy glances. The king seemed to have dropped off again into a heavy sleep, for his chest was rising steadily. Evidently the powerful drug had done its work. Maxgregor had opened the second phial, and had already began to drop the spots at intervals on the sleeping man's lips.

"There must be something wrong," the queen said anxiously. "I am sure Miss Galloway is quite to be relied upon. She knew that she had to wait. They—why does she not come?"

"Watched, probably," Maxgregor said between his teeth. "There are many spies about. This delay may cause serious trouble, but you must not return back by yourself. Try again."

Once more the signal was tried, and after the lapse of an anxious moment a knock came at the door. The queen crossed rapidly and opened it. Jessie stood there a little flushed and out of breath.

"I could not come before," she explained. "A man found me by the fountain. I can hardly tell you why, but I am quite sure that he is your enemy. If you knew Prince Boris Mazaroff—"

"You did wisely," the queen said. "I know Mazaroff quite well, and certainly he is no friend of mine or of my adopted country. You did not let him see you come?"

"No, I had to wait till there was a chance to get rid of him, madame. A friend came to my assistance, and Lord Merehaven was impressed into the service. Mazaroff will not trouble us for some little time; he will not be free before you regain the salon. And this gentleman—"

"Will have to stay here. He has to look after the king. Lock the door, Paul."

Maxgregor locked the door behind the queen and Jessie. They made their way quickly into the garden again without being seen. It was well that no time was lost, for the concert in the salon was just over, and the guests were beginning to troop out into the open air. The night was so calm and warm that it was possible to sit outside. Already a small army of footmen were coming with refreshments. The queen slipped away and joined a small party of the diplomatic circle, but the warm pressure of her hand and the radiancy of her smile testified to her appreciation of Jessie's services.

The girl was feeling uneasy and nervous now. She was wondering what was going to happen next. She slipped away from the rest and sauntered down a side path that led to a garden grove. Her head was in a maze of confusion now. She had practically eaten nothing all day; she was feeling the want of food now. She sat down on a rustic seat and laid her aching head back.

Presently two men passed her, one old and grey and distinguished-looking, whom she had no difficulty in recognising as Lord Merehaven. Nor was Jessie in the least surprised to see that his companion was Prince Mazaroff. The two men were talking earnestly together.

"I assure you, my Lord. I am speaking no more than the truth," Mazaroff said eagerly. "The secret treaty between Russia and Asturia over those passes is ready for signature. It was handed to King Erno only to-day, and he promised to read it and return it signed in the morning."

"Provided that he is in a position to sign," Lord Merehaven said drily.

"Just so, my Lord. Under that treaty Russia gets the Southern passes. Once that is a fact, the fate of Asturia is sealed. You can see that, of course?"

"Yes, I can see that, Prince. It is a question of absorbing Asturia. I would give a great deal for a few words now with the King of Asturia."

"I dare say," Mazaroff muttered. "So would I for that matter. But nobody knows where he is. He has a knack of mysteriously disappearing when on one of his orgies. The last time he was discovered in Paris in a drinking den, herding with some of the worst characters in Europe. At the present moment his suite are looking for him everywhere. You see, he has that treaty in his pocket—."

Lord Merehaven turned in his stride and muttered that he must see to something immediately. Mazaroff refrained from following, saying that he would smoke a cigarette in the seclusion of the garden. The light from a lamp fell on the face of the Russian, and Jessie could plainly see the evil triumph there.

"The seed has fallen on fruitful ground," Mazaroff laughed. "That pompous old ass will—Igon! What is it?"

Another figure appeared out of the gloom and stood before Mazaroff. The newcomer might have been an actor from his shaven face and alert air. He was in evening dress, and wore a collar of some order.

"I followed you," the man addressed as Igon said. "What am I looking so annoyed about? Well, you will look quite as much annoyed my friend, when you hear the news. We've lost the king."

Something like an oath rose to Mazaroff's lips. He glanced angrily at his companion.

"The thing is impossible," he said. "Why, I saw the king myself at four o'clock this afternoon in a state of hopeless intoxication. It was I who lured him from his hotel with the story of some wonderful dancing he was going to see, with a prospect of some gambling to follow. I spoke in glowing terms of the marvellous excellence of the champagne. I said he would have to be careful, as the police have their eyes on the place. Disguised as a waiter the king left his hotel and joined me. I saw him helplessly drunk, and I came away with instructions that the king was to be carefully watched, and that he was not to be allowed to leave. Don't stand there and tell me that my carefully planned coup of so many weeks has failed."

"I do tell you that, and the sooner you realise it the better," the other man said. "We put the king to bed and locked the door on the outside. Just before dusk the police raided the place—"

"By what right? It is a private house. Nothing has ever taken place there that the police object to. Of course, it was quite a fairy tale that I pitched to the King of Asturia."

"Well, there it is," the other said gloomily. "The police raided the place. Possibly somebody put them up to it. That Maxgregor is a devil of a fellow, who finds out everything. They found nothing, and went off professing to be satisfied. And when I unlocked the door to see we hadn't gone too far with the king, he had vanished. I only found them out a little time ago, and I came to you at once. Not being an invited guest, I did not run the risk of coming to the house, but I got over the garden wall from the stables beyond, and here I am. It's no use blaming me, Mazaroff; I could not have helped it—nobody could have helped it."

Mazaroff paced up and down the gravel walk anxiously. His gloomy brows were knitted into a frown. A little while later and his face cleared again.

"I begin to see my way," he said. "We have people here to deal with cleverer than I anticipated. There is no time to be lost, Igon. Come this way."

The two rascals disappeared, leaving Jessie more mystified than ever. Then she rose to her feet in her turn, and made her way towards the house. At any rate, she had made a discovery worth knowing. It seemed to be her duty to tell the queen what she had discovered. But the queen seemed to have vanished, for Jessie could not find her in the grounds of the house. As she came out of the hall she saw Ronald Hope, who appeared to be looking for somebody.

"I wanted you," he said in an undertone. "An explanation is due to me. You were going to tell me everything. I have never come across a more maddening mystery than this, Jessie."

"Don't even whisper my name," the girl said. "I will tell you everything presently. Meanwhile, I shall be very glad if you will tell me where I can find the Queen of Asturia."

"She has gone," was the unexpected reply. "She was talking to Lady Merehaven when a messenger came with a big letter. The queen glanced at it, and ordered her carriage at once. She went quite suddenly. I hope there is nothing wrong, but from the expression of your face—"

"I hope my face is not as eloquent as all that," Jessie said. "What I have to say to the queen will keep, or the girl I am impersonating can carry the information. Let us go out into the garden, where we can talk freely. I am doing a bold thing, Ronald, and—what is it?"

A footman was handing a letter for Jessie on a tray. The letter was addressed to Miss Galloway, and just for an instant Jessie hesitated. The letter might be quite private.

"Delivered by the young person from Bond-street, Miss," the footman said. "The young person informed me that she hoped to come back with all that you required in an hour, Miss. Meanwhile, she seemed anxious for you to get this letter."

"What a complication it all is," Jessie said as she tore open the envelope and read the contents under the big electrics in the hall. "This is another mystery, Ronald. Read it."

Ronald Hope leaned over Jessie's shoulder and read as follows:—

"At all hazards go up to the bedroom where the king is, and warn the General he is watched. Implore him for heaven's sake and his own to pull down the blind!"

Jessie crushed the paper carelessly in the palm of her hand. Her impulse was, of course, to destroy the letter, seeing that the possession of it was not unattended with danger, but there was no chance at present. The thing would have to be burnt to make everything safe.

"How long since the note came?" she asked the footman with an assumption of displeasure. "Really, these tradespeople are most annoying."

The footman was understood to say that the note had only just arrived, that it had been left by the young person herself with an intimation that she would return presently. To all of this Jessie listened with a well-acted impatience.

"I suppose I shall have to put up with it," she said. "You know where to ask the girl if she comes. That will do. What were we talking about, Captain Hope?"

It was admirably done, as Ronald Hope was fain to admit. But he did not like it, and he did not hesitate to say so. He wanted to know what it all meant. And he spoke as one who has every right to know.

"I can hardly tell you," Jessie said unsteadily. "Events are moving so fast to-night that they are getting on my nerves. Meanwhile, you seem to know General Maxgregor very well—you say that you are anxious to obtain a post in the Asturian service. That means, of course, that you know something of the history of the country. The character of the king, for instance—"

"Bad," Hope said tersely, "very bad, indeed. A drunkard, a rogue, and a traitor. It is for the queen's sake that I turn to Asturia."

"I can quite understand that. Queen Margaret of Asturia seems very fortunate in her friends. Look at this. Then put it in your pocket, and take the first opportunity of destroying it."

And Jessie handed the mysterious note to Ronald, who read it again with a puzzled air.

"That came from Vera Galloway," the girl explained. "She is close by, but she does not seem to have finished her task yet. Why I am here playing her part I cannot say. But there it is. This letter alludes to General Maxgregor, who is upstairs in one of the rooms in close attendance on the King of Asturia, who is suffering from one of his alcoholic attacks. Do you think that it is possible for anybody to see into the room?"

"Certainly," Ronald replied. "For instance, there are terraces at the end of the garden made to hide the mews at the back from overlooking the grounds. An unseen foe hidden there in the trees, with a good glass, may discover a good deal. Vera Galloway knows that, or she would not have sent you that note. You had better see to it at once."

Jessie hurried away, having first asked Hope to destroy the note. The door of the room containing the king was locked, and Jessie had to rap upon it more than once before it was opened. A voice inside demanded her business.

"I came with a message from the queen," she whispered. She was in a hurry, and there was always the chance of the servants coming along. "Please let me in."

Very cautiously the door was opened. General Maxgregor stood there with a bottle in his hand. His face was deadly pale, and his hand shook as if he had a great fear of something. The fear was physical, or Jessie was greatly mistaken.

"What has happened?" she asked. "Tell me, what has frightened you so terribly."

"Frightened!" Maxgregor stammered. It seemed odd at the moment to think of this man as one of the bravest and most dashing cavalry officers in Europe. "I don't understand what you mean?"

With just a gesture of scorn Jessie indicated the cheval glass opposite. As Maxgregor glanced at the polished mirror he saw a white, ghastly face, wet with sweat, and with a furtive, shrinking look in the eyes. He passed the back of his hand over his moist forehead.

"You are quite right," he said. "I had not known—I could not tell. And I have been passing through one of the fiercest temptations that ever lured a man to the edge of the Pit. You are brave and strong, Miss Galloway, and already yon have given evidences of your devotion to the queen. Look there!" With loathing and contempt Maxgregor indicated the bed on which the King of Asturia was lying. The pitiful, mean, low face and its frame of shock red hair did not appeal to Jessie.

"Not like one's recognized notion of royalty," she said.

"Royalty! The meanest beggar that haunts the gutter is a prince compared to him. He drinks, he gambles, he is preparing to barter his crown for a mess of pottage. And the fellow's heart is hopelessly weak. At any moment he may die, and the heart of the queen will be broken. Not for him, but for the sake of her people. You see this bottle in my hand?"

"Yes," Jessie whispered. "It might be a poison, and you—and you—"

"Might be a poisoner," Maxgregor laughed uneasily. "The reverse is the case. I have to administer the bottle drop by drop till it is exhausted, and if I fail the king dies. Miss Galloway, when you came into the room you were face to face with a murderer."

"You mean to say," Jessie stammered, "that you were going to refrain from—from—"