THERE are no poppies in the garden of sleep, though, if you come there in the season of the year, there are many flowers. And these flowers are born when you and I talk of yesterday's snowstorm, and the children's twelfthcake is still a fleeting, unstable joy. Then Tregarthen Island is gay with flowers, great beds of them. There are daffodils and narcissus knee deep, and violets fragrant and richly purple under the cactus hedges. And they nod and droop and flourish to the booming plunge of the Atlantic surges.

Where is it? What matters it? Not so many leagues from Tintagel, for they tell tales of King Arthur, and there is a deep apple orchard in the heart of the island where Lancelot slew the dragon whose teeth were flaming swords. And the gladioli flourish there in scarlet profusion.

The island of Tregarthen is a long, green, luscious slice from the mainland, some eight miles long by five in width. It is sheltered from the east and north by granite walls rising sheer and grim for a thousand feet and its music is the Atlantic thunder and the scream of innumerable sea-fowl. There are gardens in the sea-pools, there are wide stretches of sands golden as Aphrodite's hair, and the sky is fused into a blue so clear and ambient that the eye turns from it with an ecstasy of pure delight. You shall see presently what manner of place this kingdom by the sea is.

"Miriam," the princess said, "Miriam, this is paradise."

Miriam hoped that no harm had come to the small, black box. The remark was inconsequent, as the princess pointed out in her clear high voice. What did it matter if the Trevose fisherman who had brought them across was a little clumsy? Had Miriam noticed what a splendid torso he had, and what a picture he made with his blue eyes and brown skin, seared and tanned, and his white beard?

The princess stood watching the landing of her boxes. She could not have been anything else but a princess, of course, she was dressed so beautifully. Nobody in these parts had ever seen such dresses before, not even the travelled ones who had known great cities like Plymouth and Exeter.

She was tall and fair, with eyes as blue as the bounding sea, and hair as golden as the sands she trod. She carried herself imperiously as the daughter of a conquering race, and there were diamonds on her fingers and in the coral of her ears. A woman learned in the mysteries of the toilette would have told you that that heather-mixture coat and skirt, engirt by a silver buckled belt, could only have come from Paris. The same wise woman would have added that the princess was American and very rich. In which the wise woman would have been absolutely correct. To mortals she was known as Mary Blenkiron, only daughter of the late Cyrus K. Blenkiron of Pittsburg, Pa., who, as all the world knows, died two years ago—in 1885—after a heartbreaking financial duel with Zeus Z. Duncknew, in which he lost four million dollars, dying a comparative pauper with a mere ten million dollars or so. Thus do some men make failures of their lives.

Mary was something more than an heiress and an exceedingly beautiful girl. She was good, she was clever, headstrong of course, and fond of her own way. Other girls besides heiresses have been known to show the same weakness. And what manner of girl Mary Blenkiron was, you will see for yourself presently.

Between the girl and her companion there was contrast enough. Miriam Murch owned to fifty, to save the trouble of explaining that she was ten years less; and though she was thin and gaunt and brown, her skin was unwrinkled and healthy. There was a suspicion of down on her upper lip; her mouth was wide and humorous; and it was only when you came to look into those wonderful brown eyes of hers that you forgot to feel that here was a woman who ought to have been born a man.

Here was a girl who had started twenty years ago, with one of the first typewriters, to carve her way to fortune. At forty she was the absolute owner of three flourishing daily papers, all of which she had built up for herself. A busy, happy, shrewd, kindly, hard-working woman whose only grievance was that she could not enter Congress, and run for the Presidency. But this calumny might have been, and probably was, a libel of Mary Blenkiron's.

Michael Hawkes, the boatman, was staring in blank astonishment at a crisp piece of paper Mary had placed in the desert of his huge brown palm.

"I'm no scholar," he said defiantly. "What's a man want with book learning so long as he can count the cod and mackerel?"

"It's a five pound note for your trouble," Mary explained sweetly. "The only literature I know that meets with no adverse criticism."

Hawkes regarded the paper suspiciously with his head on one side. He had heard of banks and kindred institutions. James Trefarthen up to Tretire had lost all his money in one.

"You couldn't make it half a crown?" he asked, tentatively.

Mary laughed, and Hawkes so far forgot himself as to smile. Your Cornish fisherman, joking with difficulty even more than a Scotchman, is not given to levity of this kind, but the man who could hear Mary Blenkiron laugh unmoved, would have been mentally or morally deficient.

"You are corrupting the native, my dear," Miss Murch said. "Give him talents of silver and let him depart in peace."

Hawkes went off with three half-crowns, having scornfully refused half a sovereign, as savouring of lustfulness, and departed with the suggestion that he would come and take the ladies off again presently, Mary's insinuation that they intended to remain being received with scorn.

"Tregarthen won't let you stay," he said. "No visitors are allowed on the island. Seeing you would come, you had to come—being a woman."

With this Parthian shot, Hawkes climbed into his boat, and slowly pulled for the mainland. Nobody ever did anything in a hurry there. Energy would have been resented as an outrage on the feelings of the community, except at such times as the sea rose in its wrath and the trail of the rockets smote the reeling sky over beyond Tregenna Sand.

Miss Murch sat down on the little black box, which had been carried from the boat by Hawkes, and looked calmly around her. It was a February afternoon, and yet it was possible to sit in the sun without the smallest personal discomfort. The air was heavy with the scent of flowers, outside, the sea was getting up, a long ground-swell was rolling in from the Atlantic. When this ground-swell ran for days together, even in the finest weather, it was impossible for boats to land on Tregarthen. Hawkes had mentioned this, but Mary had regarded it more as an advantage than otherwise. Even Tregarthen could not control the elements.

"I think, my dear," Miss Murch said, in her clear, incisive tones, "I think it is time that you and I came to an understanding. As a hard business woman I am entitled to an understanding. To please you I have come four thousand miles. To please a girl who takes advantage of my weakness——"

"And the love you have for me," Mary said parenthetically.

Miss Murch put on her pince-nez—this when she was going to be terrible. Strong men, even unscrupulous financiers, had trembled before the flash of those glasses. Mary laughed.

"I don't care," she said—"I really don't care. I came here because the founder of our family was originally a wanderer from Tregarthen. He was persecuted for his religion, and he fled to New England. He was one of the original Pilgrims who came over in the Mayflower."

"According to statistics," Miss Murch observed, "there are at the present time no less than 250,000 American families claiming direct descent from the original Pilgrim Fathers. I met one in New York the week before we sailed. He had a nose like a scimitar, which nose he used largely for the purpose of articulation. His name was Vansleydon."

"An impostor," Mary said calmly. "But you know that what I say is true, because you have seen my ancestress Marcia Blenkiron's diary. And that diary was actually written on this very island. All those delightfully quaint phrases were actually penned here. Think of it, my dear, think of the delight of exploring the island! I want to see the place where Amyas Blenkiron saved the life of his rival, and where Marcia found the dying Spaniard after the Spanish galleon, Santa Maria, was wrecked here. And I believe you are as interested as I am."

Miss Murch candidly admitted the weakness. As a matter of fact, Marcia Blenkiron's precious diary was in the little black box with the rest of Mary's diamonds, and hence the anxiety.

"I'm an American, and proud of the fact," Miriam said. "But I wish my country was a trifle older. I wish we had a history, a past, as the people have here. That is why I can enter into your longing to see the place. But shall we be allowed to see it? The island belongs to Tregarthen—not Mr., or Sir, or Lord anything, but simply Tregarthen. It sounds delightfully feudal. The island belongs to Tregarthen, who makes all the laws, pays neither taxes nor excise, and you have heard them say what a peculiar man he is. The people here are a form of Christian Commonwealth, a self-supporting community, who pay no rent or dues of any kind and who hold communication with nobody. Tourists who have heard of the place and tried to get a footing here have been rigidly excluded. And I don't fancy that Mary Blenkiron, beauty and heiress, will care to be shot off the island like a common trespasser."

Mary was bending over a sea-pool, clear as the ambient air and filled with the most brilliant pictures in many hues. The reflection of her exquisite face was smiling back at her.

"Miriam, where is your boasted friendship? Did you ever know a man who could refuse me anything? You will see what you will see. Let me once smile on that man and he is lost. Then you shall fix your glasses and glare at him, and we will walk over his prostrate body."

She waved her wet jewelled hands lightly towards a floating grey gull.

"I am not going to be expelled from the land of my ancestors," she said. Then she lay back, filled with the pure delight of being.

And surely all the joys of life were bound up in that one slim young person with the diamonds on her fingers, and the diamonds, too, in her sparkling eyes. Health, wealth, beauty, and a volume of fresh sensations—new, and with the leaves uncut—before her; what more could the heart wish for?

She grew grave in the contemplation of the perfect things about her. Though it was but February, the sun was full of grateful warmth, and the breeze, blowing in from the wide Atlantic fields, was crisp and clear. Behind lay the island, with the flowers and orchards and green meadows, while against the granite cliffs of the mainland the long ground-swell was thundering. Each long-crested wave broke with a booming plunge, millions of yards of creamy white lace seemed to be creeping ribbon fashion along the cliffs. Almost at Mary's feet an old dog-seal gravely disclosed his grizzled moustache and wide speculative eyes ere he sank like a stone again.

"This is going to be absolutely delightful," the girl cried. "Miriam, we will stay here till we get tired of it."

Miss Murch murmured something relevant to the policy of her papers, and the shortcomings of a certain managing editor of hers. Nevertheless the charms of the place were not lost upon her.

It would be good to stay here, pleasant to explore all the scenes disclosed in that quaint old diary. What would Tregarthen say when Mary stood confessed as a relative of his? For Marcia Blenkiron of the diary had once been Marcia Tregarthen in the days of old.

"I fear we shall have trouble with him," she said, à propos of nothing.

"With Tregarthen, you mean?" Mary replied. "Not at all, my dear. We shall manage him entirely by kindness. And if he discloses Napoleonic leanings we must bring up our Guards and spring the Great Secret upon him. There may perhaps be no occasion to use the Great Secret at all. But if the worst comes to the worst we hold the key to the position."

"True," Miriam murmured. "I had forgotten that. Still, it is time we made a move of some kind. Here comes a native."

A man lurched down to the beach. He was dressed like a sailor, with a red stocking-cap on the back of his splendid head. A young man, lean-flanked, broad-chested, full of life and vigour. Burnt to a deep mahogany was his clear grained skin, his dark gipsy eyes met Mary's blue ones fearlessly. There was curiosity and frank admiration in his glance.

"What are you doing here?" he asked.

A fisherman beyond question, a fine type of a young Cornish fisherman, fearless, frank, meeting every man—and woman—on terms of absolute equality. Your fisherman has been lord of himself for many generations, and knows nothing of the slimy by-paths to wealth, and calls no man master. The gaoler of dubious millions was no greater autocrat than these Phoenician-descended fisher-folk.

But Mary was slightly annoyed. She came on one side of her family from a humble stock, therefore she was disposed to take her present exalted station seriously. Miriam smiled. She would have loved Mary less but for her little weaknesses.

"That magnificent creature has not properly appraised you," she said. "He is in darkness as to your millions. Your diamonds convey nothing to his eye. Tell him what you are worth, tell him about those Chicago tramway shares. Your beauty he evidently appreciates."

Mary laughed; her displeasure was as elusive as breath on a mirror.

"Will you tell us where we can find Mr.—I mean Tregarthen?" she asked.

"Tregarthen has sent me for you," the man replied. "I am Gervase Tretire. Who are you, and what is that woman's name?"

Mary explained faintly. For the first time in her life she wanted an ally. She glanced at Miriam, who was silently enjoying the situation. To see Mary getting the worst of an encounter with a mere man was delightful.

"It is kind of Tregarthen, very kind," Mary said, with a thin sarcasm utterly lost on one listener. "And when Tregarthen gets us, what do you suppose he will do with us, Mr. Tretire?"

"Eh?" Tretire demanded. "What's that?"

Mary repeated the question. The man had never been addressed as Mr. in the whole course of his life, and possibly hardly recognized his patronymic from the lips of another. Slowly he comprehended.

"Send you back again," he said promptly. "Pack you off to the mainland soon as the swell runs down. We have no strangers here."

"He says 'strangers' out of politeness," Miriam murmured. "But his tone plainly denotes that he means tramps. We are suspicious characters, Mary."

"Well, sir, and meanwhile what can we do?"

"You can go to the Sanctuary," Tretire explained.

"The Sanctuary!" Mary echoed. "Delightful! Do we do penance there?"

"I don't know about penance," Tretire said dubiously; "but you clean out your own cell and cook your own food."

Mary listened entranced. There was a mediaevalism about this far beyond her most sanguine expectations. Tretire was obviously melting. No man is insensible to the flattery of an interested audience. Even as he spoke a figure came down to the beach towards the little group, a tall thin man, with a refined dreamy face and eyes like the sea. In years he could have been no more than forty, but his hair was quite white. The contrast was not displeasing; in fact, it was exceedingly fascinating.

Tretire turned to him easily, yet not without deference.

"Tregarthen," he said, "these are the women you spoke of—Miriam Murch and Mary Blenkiron. Mary Blenkiron is the pretty one."

THE man with the refined features bowed with the grace of courts and palaces. He was a Louis, a Charles, a Bayard and troubadour at the same time. Yet he might have been—indeed, from his own point of view he was—a monarch welcoming strangers to his court. A handsome man with a dreamy intellectual face, the face of a poet, and the hard firm mouth of a soldier. A man who formed his own judgments—generally wrong ones—and who acted up to them to the detriment of himself and everybody about him. But you will know more about that presently.

"I wish I could say I was glad to see you," he said. "Did they not tell you at Trevose that under no circumstances were strangers permitted within the Dominion of Tregarthen? I am king here, I make my own laws, I can imprison my subjects without let or hindrance. I could send you to gaol, and the British House of Commons has no right of interference."

"All these things," Mary said, "did they tell us at Trevose. And, being women, that is exactly the reason why we are here."

Something like a smile trembled on Tregarthen's thin lips.

"However," he replied, "we must make the best of it now that you are here. So long as this ground-swell runs it is impossible for a small boat to reach the mainland. After a big storm out in the western ocean the swell sometimes runs for days."

"The longer the better," Mary murmured.

"Perhaps you will have cause to modify your opinion," Tregarthen suggested dryly. "Sometimes we are compelled to have people here from the mainland, as last year, for instance, when the herring failed us entirely, and half the people at Trevose were starving. But they have to conform to our regulations, and I fear I cannot make any exception in your favour. In the Sanctuary are our poor—it is a workhouse, if you like to call it so. There you will have to reside, indeed there is no other place for you. You will wear a blue woollen dress with white cuffs and collars. Nothing like this, oh no."

He indicated Mary's faultlessly cut tweed gown and her jewels with a fine contempt. Once more Miriam smiled. A little colour crept into Mary's cheeks. The performance of walking over the man's body was not working out in strict accordance with the programme.

"It might help us a little," she said coldly, "if I were to tell you who we really are. I am an American."

Tregarthen glanced once more at the diamonds.

"So I should have gathered," he said pointedly.

"Of English extraction," Mary went on rapidly. Really, this monarch was too painfully outspoken. "My name is Blenkiron, and I claim and can prove direct descent from the Amyas Blenkiron of this island."

"Pray go on," Tregarthen replied, "I am deeply interested."

Mary melted in a moment. She spoke of the diary which she knew almost by heart, she touched on scenes in the history of the island which Tregarthen had deemed to be known only to himself. Beyond question the girl was all she claimed to be. Tregarthen admitted this as a monarch might who interviews a claimant to an attainted estate.

"I cannot deny what you say," he admitted, magnanimously. "Some of these days I should like to see that diary which is more than once quoted in the archives of the Dominion."

"I will try and get it for you," Mary said demurely.

Thus Mary's diplomacy. But then she had a good and pressing reason why she should not show Tregarthen the diary. Why she did not desire to show it to him, and what happened on the occasion when she did show him, will be told in due course. Her eyes were full of smiling promise.

"Are we still doomed to the Sanctuary?" she continued.

"Unfortunately, yes. Indeed, there is nowhere else you could possibly go. And if you were my own sister I could not violate one of my rules for you. In my own house I have male vassals only, so you could not come there. The cottages, I am ashamed to say, are of the humblest. We are miserably poor here, we can only fish rarely, and our flowers are a little later than those of Scilly, and therefore fetch less money at Plymouth and Bristol. Fortunately my people have no taxes to pay and no rent. We are a Christian Commonwealth and I am the Lord Protector."

Cromwell might have said it or Wolsey. For one brief moment Mary was actually deeply impressed.

"Have you no manufactures?" Miriam asked. "No source of employment for the poor women? You know what I mean?"

Tregarthen's eyes flashed. The spring of fanaticism that Miriam had guessed at from the first was tapped. His speech gushed out like water from the living rock. Miriam watched him with all the palpitating interest the student of human nature feels for a new type.

"I would cut off my right hand first," he cried. He strode to and fro across the wet sand; he had forgotten his audience. "Rather would I see my people starving in a ditch. I say your modern commerce is a hateful and loathsome thing; that what you call business is a delusion and a lie. And now you have dragged women into it, women who should remain pure and unspotted from the world, who should remain at home and make it beautiful. Once start a manufactory here, and the purity and morality of my people are doomed. Poor they may be, but honest and upright they are, and so they shall remain while there is strength in my arm and breath in my body. Let the men stick to their flowers and their fish, let them toil in the sweet air and in God's blessed sunshine, and they will be as their fathers before them—good men, with no guile in their hearts. Do you know that there has been no crime of any kind on this island for over a century? But once you send greed and the love of gain amongst us, you destroy our purity for ever. And anything would be better than that."

"There is a great deal in what you say," Miriam replied. "And at the same time a deal of nonsense. Do you know, sir, that I have made a large fortune by my own efforts?"

"You have my profound sympathy," Tregarthen said with feeling.

Indeed, he was so obviously sincere that all the contemptuous anger died out of Miriam's heart.

"You are utterly and absolutely wrong," she said. "There is a large field waiting for women, a field that calls to her. Oh, I would not have her different from what she is for all the wealth in the world. But I have found scores of them starving with temptations such a man as you cannot dream of," Miriam said, glaring behind her spectacles. It was Mary's turn to look on and enjoy the fray. "Do you know what I would do with you if I had my way?"

"Could one hazard a guess as to the wishes of a woman?" Tregarthen asked.

"Well, I would send you out into the fierce hard wolfish world with just one solitary half-crown in your pocket to get your own living. I would starve your eyes clear and your mental vision clean. Ah, you should learn what it is to be a defenceless woman, you should learn what opportunities you are wasting here. That's what I would do with you, if I had the chance."

"A woman at work, at man's work, is an outrage before God," Tregarthen cried stubbornly. "You will never see that here."

"What if your flowers fail?" Mary asked.

"We starve, or near it," Tregarthen admitted. "But we are patient. Complaining is for the children. They are tried in the fire of affliction, and they endure it with silence."

Miriam listened quietly, but the gleam of battle was in her eyes. On woman's mission she was the greatest authority in the United States. The Employer was no god in the car, nothing more than the conduit pipe from which flowed Capital. And here was an Employer, a king of Employers, who regarded starvation as one of the first attributes of labour. That man would have to be taught things. When she had her glasses on, Miriam would have taught things to the Czar.

"Do you starve with them?" she repeated.

"Yes," Tregarthen replied simply, "I do."

"You starve deliberately in the land of plenty? Do you know that I could make your island as fine a paying property as Monte Carlo? Of course I don't mean as a gambling resort. Do you know that I have three newspapers with an average weekly circulation of five million copies? I could 'boom' your island—every good American during the European tour would come here. Huge hotels would spring up. From thirty to forty thousand pounds annually would find their way into the pockets of your subjects. There would be no more trouble, no more starvation—all would be peace and happiness."

"Don't," Mary gasped. "Please don't, Miriam."

The light of battle died out of Miriam's eyes and she laughed. At the same time she was filled with bitter contempt for Tregarthen. The man was so regal and yet so bigoted and narrow. But still he starved with the rest when the flowers failed.

"Is your flower harvest now?" she asked.

"From now till the beginning of April," said Tregarthen. "That is, during the next six weeks. When the Scilly and French crops begin to flag we step in. Of course we get nothing like the Scilly prices, because they have what the tradesmen call 'the cream of the market,'"—he pronounced the phrase with an air of supreme contempt—"and then we get snow sometimes and frosts. You will see for yourself that our flowers are more robust than those from Scilly. But even a good season barely serves us with food."

"And the pilchards?" Mary asked.

"They only come once in two or three years now. At the top of the island, at Port Gwyn, you will see fifty or sixty deserted, dismantled cottages. That was once my most thriving village. But the pilchards failed and failed, and the villagers dropped off and died one by one—of starvation."

"They couldn't have done that in America," Miriam snapped. "They would have hustled round for something to do. And if you had stepped in with your antediluvian ideas, they would have deposed you."

Tregarthen smiled in a pained manner. This newspaper woman was a terror to him; but he got to love her in time, as everybody did. For the present most of his speech and all of his eyes were for Mary. He had never looked upon so bright and glorious a creature as this before. Mrs. Guy, the Rector's wife up to St. Minver, was a handsome woman, but she had no loveliness, no dresses like Mary. He turned for relief to Mary.

"Show us your flowers," she said.

Tregarthen silently led the way beyond the long hedge of cactus and oleander bushes to the fields beyond. Here was a valley surrounded by a high foliage, palms, bamboo shoots and pampas grass, a warm and sunny valley filled from end to end with sheets of flowers.

Mary gave an involuntary cry of delight. So far as the eye could reach, there were nothing but blooms set out regularly with narrow grassy paths between. There were daffodils, big tranquil yellow and blood-red blooms, waving narcissus, jonquils, and beyond these again vivid flashes of gladioli and tulips and great waxen-headed hyacinths, stiff and splendid. There were tiny green hollows, too, filled with violets. Besides these, there were other flowers that Mary had not seen before.

The sun was shining clearly over this paradise, the air was heavy with perfume. From beyond the rampart hedges came the boom of the sea. Tregarthen surveyed the scene with an air of pride.

"This is our main garden," he said. "We have no place in the island that is so well protected as this. There are orchards and corn-fields, and on the sloping sides to the west we grow our potatoes. But this is the spot where our hopes and interests are centred."

"How large is it?" asked Miriam, the practical.

"About forty acres altogether. Most of our womenkind are here, you see."

There were women and girls harvesting the flowers, young and old, perhaps some five score altogether. They were dressed in plain blue woollen gowns short in the skirt, they had strong boots, and homespun black stockings, and on their heads were stiff frilled caps that looked like fans placed gracefully at the back of their heads. As one or another stood up, Mary noticed the freedom and grace of their carriage. One, a girl, passed with a frank bold glance, but with no vulgar curiosity in it, though the people she saw were strangers. Mary moved towards her in a friendly manner.

"Please may I speak to her?" she asked Tregarthen.

"Surely yes. You are going to stay here a few days, you are going to dress like the rest, and live like them too. Jane, come here."

The girl advanced fearlessly. "Yes," she said; "do you want me, Tregarthen?"

She was absolutely natural and self-possessed, she answered all Mary's questions in a manner that many a Society aspirant might have envied. She spoke of the harvest of the flowers, the planting of the bulbs, of the constant clamour of the dealers for more foliage, which they were unable to give without diminishing the vitality of the parent bulb. And all this time she was opening out a new world to Mary.

The skin under its olive varnish was clear as milk, her dark eyes were utterly fearless, and yet there was the reflection of a tragedy in them. But then, there were times when starvation was perilously close at hand.

"I should like to see more of that girl," Mary said, when Jane had departed, nodding over a bunch of daffodils.

"You can see them all as much as you please," Tregarthen said regally. "You shall see all the machinery of the island. Meanwhile I have had all your belongings removed to the Sanctuary. When you have had supper I shall be glad for you to assume the garments provided for you. To-morrow you may explore the island at your leisure, and will perhaps do me the honour of dining with me at one o'clock."

There was dismissal in the tones of the speech. Mary did not know whether to resent it or not. She had forgotten for the moment that this man and his ancestors had been rulers of Tregarthen for seven hundred years.

"There is one thing you have forgotten," she said.

"Indeed," the Protector asked, "and what is that?"

"To show us where the Sanctuary is. Do they expect us there? Are rooms prepared for us? Shall we be in the way?"

"Everything is ready for you. There is always room in the Sanctuary. You will draw your rations and sup at the common table, after which you are free to do as you please till ten o'clock, when all lights are extinguished. You will perhaps do me the honour of dining with me to-morrow. One o'clock."

He bowed low, with a sweep of his soft felt hat, and went his way. Mary stood watching him until he was out of sight.

"A fine man, a handsome man, and a man who lives entirely for his people," she said, not without enthusiasm. "Miriam, I feel as if I had slipped back half a dozen centuries. We are going to have a good time here."

"Yes, and these people are going to have a good time later on," Miriam snapped. "A splendid man if you like, but a visionary and a fool. What business has he to starve these people when they might have peace and plenty? Some of the finest crops in the kingdom might be grown here—a little enterprise might change the whole aspect of the place. Look at that splendid girl who spoke to us just now. She might have been a duchess, only she is too handsome. And yet you saw the shadow of the tragedy in her eyes. Tregarthen ought to be made to get his own living or starve. If we could only persuade him to take a voyage round the world! Shall we save these people, Mary?"

Mary's eyes gleamed. "Yes, yes," she cried. "The lesson shall be taught—taught kindly if possible, but taught all the same. It seems horrible to think of famine in connection with a paradise like this. That man must be brought to his knees. If not, we will invoke the aid of the Great Secret."

Miriam nodded approval. What the Great Secret was and how it affected Tregarthen will be seen all in good time. For the present Mary pleaded a wholesome and unromantic hunger, and a desire for the Sanctuary and rest.

The Sanctuary was over beyond the flower garden, they were told, amongst the orchards where the apple trees were, and whence came the cider in due season. The two visitors climbed up and looked down into the valley. Then they turned to one another with a cry of admiration and delight.

A shelving broken valley lay below them, a green pleasance fed and watered by a stream fringed by ferns—maidenhair, kingfern, and the like. There were hundreds of trees in the orchards, apple trees just touched with tender emerald points where the buds were bursting. And back in the valley was a long low stone house covered to the quaint twisted chimneys with creepers, out of which mullioned windows peeped. A more perfect specimen of an old abbey it was impossible to imagine. All about it lay wide green lawns gay with flowers.

"It is Tennyson's 'haunt of ancient peace,'" Mary cried. "We only want the moan of doves, and the murmur of innumerable bees to complete the picture. Did you ever see anything so lovely? And to think that we are actually going to live in that delightful place!"

Miriam was duly enthusiastic. Perhaps she was also thinking of the frost and snow, and of the tragedy in Jane's splendid eyes. And the man who owned this paradise in his ignorance and folly seeing the tragedy of those eyes day by day yet doing nothing to avert it.

"I'll fight him," she thought, "fight him and beat him on his own ground. No mortal man has the right to play Providence like this."

Mary just caught the last few words. "But he starves with his own people," she said.

"Fine excuse, truly," Miriam cried. "I knew a girl, a rich girl, who would have given her opinion with considerable freedom to a less picturesque host than ours. Don't let the glamour of it overwhelm you, Mary; don't blind your eyes to that man's awful folly. I could render the place rich and prosperous in a year without so much as brushing the dew off a single illusion. It's monstrous, Mary, perfectly monstrous. Every woman here has her living in her own hands, and a good one, too. Don't you remember what the diary said about the Spanish lace?"

Mary recollected. It was all coming back to her now.

"But suppose the art is lost," she suggested. "My ancestress, Marcia, had it, and so had two other women in the island. They learnt it from the survivors of the Spanish galleon after the defeat of the Armada. It was a great art, the making of that Spanish lace. I saw some of it in Paris the other day, modern make, quite, and they asked me ten guineas a yard for it——"

"And you bought it, of course?" Miriam smiled.

"I plead guilty," Mary admitted. "It was like a lovely cobweb. And to think that once they made that kind of lace here, to think that somebody on the island may still possess the art. Do you think it possible that such can be the case, Miriam?"

Miriam shook her head and pointed towards the Sanctuary.

"Let us go and see," she said. "There is a deal of promiscuous knowledge to be gained by asking questions."

A BROAD path, bordered on each side by flowers, led down to the Sanctuary, and an old sun-dial with some monkish inscription stood before the open door. It was all singularly quiet and beautiful, and yet everything was strongly eloquent of poverty, from the bare windows to the rusty lichen strewn apple trees with which the homestead was surrounded.

"A wholesale pruning of these trees would be an advantage," Miriam said critically. "All this is monkish, and mediaeval, and distinctly Romanish. And yet Tregarthen is a Protestant. What does it mean?"

"In the brave old days, Tregarthens were Catholics," Mary explained. "The only one in the family who made a noise in the world was Rupert Tregarthen, who took a prominent part in the Reformation. It is all in the diary, and accounts for this monastery here."

They passed under a noble archway into a cloistered quadrangle beyond. On the smooth green a number of rooms or cells abutted, shaded by the long delicate tracery of the cloisters. At the far end was one large lofty room once a chapel, doubtless, but now used as a refectory, or common dining-hall. In the centre of the lawn, round what had once been a fountain, a little group had gathered.

They were men and women, old, and past work. As Mary turned round she saw a second refectory, and this she judged correctly to be given over to the men. But just for the moment she was more fascinated by the group round the ruined fountain. How old and worn and faded they looked, and yet how clean!

Their life's work was finished, and they were in the autumn of their days. They seemed perfectly happy and comfortable in the sunshine. It seemed impossible to connect famine and starvation and death with these people, for they sat amongst flowers, the Atlantic surges were the music of their dreams, and the air they breathed was the breath of life itself.

They turned towards the newcomers with that frank free gaze Mary and her companion had noticed in Jane and Gervase Tretire. There was no adulation, no class difference here, not even in Tregarthen's case, though they would have done anything for him. They bowed gravely, and one, a very old white-haired palsied man, said something that sounded like a welcome. Then they fell to talking again, save for one woman, as if the strangers had not existed. Nothing could have been in better taste. They were talking of the sea, ever talking of the sea, the boats, the pilchards, the big take of mackerel 'over to Trevose.' Sometimes in bad weather they reverted fearfully to the flowers, but usually they had only one subject and that was the sea.

One of the women detached herself from the group, and crossed over to Mary and Miriam. The former smiled in pure delight. She saw a woman well stricken in years, a woman bent with seven decades of trouble and care and anxiety. Once she had been tall, and she was still beautiful, despite her plain woollen dress. The fanlike cap on her head was no whiter than her abundant hair. There were wrinkles on her faded brown face, innumerable wrinkles like the markings on the rind of a melon, yet the cheeks were red, and the dark eyes clear as those of a child. She spoke slowly and quietly, with a gentle dignity. Dressed in satins, with family gems of price on her long slender fingers, she would have passed for the chatelaine of some great house; and she was talking to two ladies who were absolutely assured that they were in the presence of a third.

"I am Naomi, widow of Isaac Polseath over to Garrow," she said. "He and my two sons and my son-in-law, James Pengelly, were drowned nineteen years ago in the great storm in September. That is why I am here. They told me you were coming and I prepared your cells for you. We sup at seven in the refectory yonder. Shall I show you your cells?"

"You are very kind," Mary said faintly. It was all she could say. Nothing but good breeding prevented her from staring Naomi out of countenance. Up to now she was the greatest surprise in this surprising island.

"Was your husband a fisherman?" Miriam asked.

"Yes, sure. We have all been fishermen since time out of mind, until the day when Tregarthen brought the flowers here. Many a time I have helped with the fish, and sailed the boat, too, for my poor master who is gone. But please to come this way."

Mary followed wondering. She hoped that she had not gaped, that Naomi had not caught her with her mouth wide open. In all her experience and all her reading she had never come upon anything like this before. She had lost the power of asking questions. Even Miriam, who was a perfect interrogation point, was silent. She saw the small stone-flagged cell, lighted by a high pointed window exquisitely traced; she saw the spotless white bed, the open grate, and the cupboard containing one or two plain cooking utensils. On the bed lay a blue woollen gown. Opposite was a table with an unframed fragment of looking-glass. Mary did not know that this was a luxury pure and simple.

"To-night my niece Ruth has cooked your mackerel and potatoes," Naomi explained. "Tomorrow she will teach you how to do it for yourselves. You must not mind Ruth: rare impulsive and headstrong she is. Never was a body on Tregarthen before like Ruth. But a good girl in the main."

"I am sure of it," Mary cried. "My dear kind Naomi!"

But the elder woman had gone, had slipped away with tact and feeling. She had indicated by a glance the woollen dress lying on the bed. Mary slipped hers on and gazed at herself critically in the fragmentary looking-glass.

"An admirer of mine once remarked that I could not look bad in anything," she said sententiously. "On the whole I fancy I shall survive the uniform. On the other hand, you will look a perfect fright."

"I would rather have my brains than your beauty," said Miriam, calmly. "You are intoxicated with the place at present, but to-morrow you will not rest till you have had your needle and cotton at work and fitted that frock properly. Tregarthen may despoil you of your Redfern's and Worth's gowns, but he can't very well ask you to remove your Worth's corset. When that dress fits you you will look as beautiful as ever, Mary."

"I don't think there is any doubt about it," Mary said serenely.

A wonderful evening, a delightful evening, truly! First of all there was that magnificent old refectory dimly lighted by candles, its marvellous tracing peeping out of the Rembrandt shadows, the carvings on the walls, the wonderful windows. Then there were the long tables covered with coarse white cloths and gay with flowers. There were perhaps fifty women in the refectory altogether, the aged who lived in the cloistered sanctuary, and their younger relations who were permitted to reside with them and see to their wants when not engaged in the struggle for bread.

For meat there was fish and potatoes and bread, eaten off wooden platters. For drink there was tea in small quantities, and a thin hard repulsive cider, the vin du pays that caused Miriam to regret the want of the pruning-knife in the orchards. A white-haired woman, far older than Naomi, sat at the head of the table and said a long quaint grace, then they fell to and ate slowly and with refinement. Mary, who had seen costly feasts ravished in famous restaurants, was greatly pleased.

"They are never in a hurry," she murmured, "which is in itself a sign of good breeding. Miriam, has it occurred to you that these good fisher-folks are ladies and gentlemen?"

"They each have a clear pedigree of seven hundred years," Miriam replied. "They don't drink, and they don't swear, and they have nothing to excite their cupidity. I wonder if they grow peas in the island."

"What do you mean by that, you inconsequent creature?"

"Well, I was wondering how they would eat them. You will observe we have merely two-pronged forks. You can't eat peas with two-pronged forks, steel or otherwise. And I am morally certain that no soul here could so far defile himself as to put his knife in his mouth. Let us stay here till the green-pea season, and solve the mystery."

Mary laughed that clear wholesome laugh of hers, at some remark of her companion, and a girl opposite looked up. Mary immediately grew grave again, for she was critically regarding the most beautiful creature she had ever seen in her life. Mary was so fair herself, and so frankly aware of her own loveliness that she could afford to recognize beauty in others. She saw a perfectly oval brown face, a complexion as pure as running water, with the exquisite rose pink under the tan. A haughty face, a real patrician face with short upper lip, arched eyebrows, and a nose thin and arched also. She saw a pair of dark grey eyes that seemed to speak, so full of expression were they. It was a wilful face, too, the face of one who understands, and suffers, and rebels against the suffering. Here was a girl who, if you could only make a friend of her, would lay down her life for you. Lastly, it was the face of a girl who was educated.

"Did you ever see anything like her?" Mary whispered.

"Never," Miriam replied, with perfect sincerity. "And what a figure! And what a face! Keen and strong, and educated, too. Another wonder, Mary. Where did that girl get her education from?"

"I wonder who she is?" Mary said inconsequently. "We'll ask Naomi. Miriam, I am going to try and make a friend of that girl; something draws me towards her. And I fancy she is well inclined to us."

Impulsively Mary nodded across the table and smiled. Instantly the suggestion of hauteur and uncertainty in the girl's face vanished, and she smiled in reply; a frank charming smile it was.

"What a sensation she would create in Society," said Miriam. "Here is a girl half starving on an island who would be a duchess at least in a year. And yet I dare say she is engaged to some fisher lad who has no ambition beyond a hut and a boat of his own."

"There's ambition enough in her," said Mary. "When the meal is over and that dear old Mother Shipton yonder has returned thanks, we'll go and ask Naomi."

The meal was over at length, the candles were extinguished, and the company slowly departed. They took no notice whatever of the strangers, everything was in perfectly good taste. Mary followed Naomi along the cloisters.

"May I come in for a moment," she asked, "or do I intrude?"

"Come in, my dear, come in," was the reply. "I make an aim to sit down and read the Good Book for half an hour before I lay my old bones down to rest. But there's plenty of time. Come in."

Mary entered, followed by Miriam. Like everything else they had seen, the place was spotlessly clean. I believe the expression that you could eat your dinner off the floor is the correct one under the circumstances where the good housewife is concerned. One or two pictures, almanac style, graced the stone walls. But they were pictures of the sea, always the sea.

"May I ask you a question?" said Mary. "There was a girl seated opposite me to-night. Any one so beautiful——"

Mary paused, conscious that somebody had entered the room. She turned round to see the very girl standing behind her.

"Mary Blenkiron and Miriam Murch," Naomi said, "this is Ruth."

The girl inclined her head somewhat haughtily. And yet there was a quiver of the lips and a luminous moisture in her eyes. Mary held out her hand.

"I am pleased to know you, Ruth," she said. "Will you call me Mary?"

The girl caught the hand almost passionately. "That I will," she cried. "Ah, if you only knew how I had longed for something like this, longed for the day when. . . . and—and God bless you, Mary!"

MARY positively refused to go any further for the present. She was tired and happy and lazy, for it had been one of those Days of Rare Delight that come to us all at times, days that we frame in golden memories and varnish with sweet recollections. She had been up early; she had seen the sun gild the latticed windows and the quaint twisted chimney-stacks of the Sanctuary; she had seen the brown shadows chased from the cloisters and the children playing on the green. These latter treated her with a superb scorn, a shy scorn that was yet perfectly self-possessed. Mary had seen Courts, had even backed breathlessly from Royalty itself, but she had seen no self-possession like unto this.

It was the same with all of them; men, women, and children alike. They answered her with straight and fearless eyes and a consciousness of complete social equality that still irritated this petted Democrat a little. They were poor folk, they were dreadfully ignorant and conceited (twin sisters, these), but they were certainly refined and there was no trace of vulgarity about them. It seemed almost impossible to believe that these broad-chested, straight-limbed men who carried themselves like princes should be unable to read. Assuredly Tregarthen had a deal to answer for.

Mary had seen the cottages, small and clean and yet eloquent with poverty; she had conversed with men and women and had looked into their eyes. And in all the eyes was the shadow of the tragedy, the haunting fear of hunger. Even the children had it.

Now, according to the tenets of all the smug philosophers, these people should have been utterly and entirely happy. They had no rent or taxes to pay, every householder was technically owner of his lands and hereditaments. A tithe of his earnings went to Tregarthen, who handled all the money, and the rest belonged to the tiller of the soil. There were no public-houses, no newspapers, and no post-office. There was a lovely island and a climate as perfect as any God has vouchsafed to the British Isles. Obviously, then, it was the duty of these people to be happy. They should have run races, garlanded themselves with flowers, and danced to the sackbut and hautboy.

But they did none of these things, albeit they were a hardy and well-nourished race. They had no sports, no conversation beyond the eternal sea and the prospects of narcissus and daffodil, they seldom laughed or smiled because the phantom of starvation was always before them. Mary thought of it angrily. Tregarthen could stop this by the raising of his hand. He should stop it, and she would compel him to do so. In the first place she would try argument, logic, and all the rest of it, and if that failed the great coup should be sprung. If Tregarthen only knew!

It seemed to Mary that she had seen everything. She had seen the harvest of the flowers going forward, she had seen the mile-long endless cable by which the baskets of blooms were transferred to the mainland at such time as the Atlantic ground-swell came reeling across the bay. She had seen Tregarthen's partially ruined castle on the headland where the lord of the island kept his solitary state. Time was when Tregarthen Castle had been a fortress of note, a ruin spoken of in legends and woven into fireside tales. As yet Mary had not explored its gloomy grandeur; that, she hoped, was to come. For the present she was interested in the human document with the aid of Miriam and Ruth who had been impressed into the service. Ruth had harvested her flowers before the sun was on them.

Mary was seated on the crest of the Valley of Contrasts. The spot had no official name of the kind, but it was even as Mary had described it. In front the tossed, wind-blown sandhills trended to the beach-dunes ruffled and quilled with weeds and carpeted with sea-pinks. Wild and desolate was this side with the chain of rocks, below this the firm reaches of sand stretched, and then the sea, blue as sapphire, and curling in from the Atlantic in huge long-crested waves, which broke thundering on the sands or carried up to the ramparts of the mainland, and dashed to pieces there like mile upon mile of exquisite billowy lace. The stagnant air trembled with the thunder of the breaking rollers, across the track of the sun a diaphanous haze of spray hung. Here you had all the spectacle of a great storm at sea with never a breath of wind to ruffle the head of a budding daffodil. And all this within five hours of London, so please you.

That is what lay on one side; the great crinkled face and the mighty voice of the Atlantic, the sweetest air under heaven, and just at the back of the sand dunes, where Mary was sitting, the edge of a valley which is a perfect paradise of flowers and waving foliage. It was like sitting on the edge of two climates. Practically speaking, it was a mere matter of shelter from the winds. One side of a tree might be blown sand and sea-pinks, the other a smiling oasis. Mary broke out enthusiastically.

"I should like to stay here always," she said.

Ruth laughed. There was something hopeless in the sound, a something suggestive of dark, screaming nights and the breaking up of boats in it.

"You wouldn't," she said. "I have seen Paradise turned into a howling desert by the frosty breath of one night. How redly the sun goes down! Did you ever see anything so magnificent as the crimson flush of that big sea?"

Mary was moved by it, and said so. Again Ruth laughed.

"It looks like frost," she replied. "Maybe the wind may shift a point or two south and carry it away. Frost is our nightmare at this time of the year. If it comes, not a flower yonder will be worth gathering in the morning. You see, we are too close to the mainland—if we were ten miles out to sea we should be better off. If the frost comes we are ruined. We shall have to struggle on as best we can till spring comes again. It happened two years ago. . . . God grant you may never see such a sight as that. And the pilchards had failed, so there was little to expect from the villagers over to Trevose. Many of the children died, even strong men perished. And the pity of it is that it could have been so easily averted."

"Who by?" Miriam asked sharply.

"By Tregarthen. Tregarthen is a good man, he loves his people heart and soul, but in some things he is no more than a madman. He is king here, and we are his subjects. And we would do anything for him. But he will do nothing for us because it is a crime for women to work, and he fears the greed of gold that business would bring. Can you do nothing for us?"

Ruth's eyes were gleaming, her hands were outstretched passionately. She walked up and down the spit of sand with the sinuous grace of a tiger. In all the fair picture was nothing fairer than this.

"I can do a great deal for you, Ruth," Mary said. "I am rich, for one thing; and there are other means at my disposal. But if there are others in the island who feel as you do——"

"There are none, except perhaps my dear Naomi, and she is old and fearsome. I am the only snake in the paradise—I and Gervase Tretire. And I feel all these things because I have read and studied, and I understand."

"Oh, oh! So you have read and studied?" said Miriam. "Where?"

"It is a secret. You must not tell anybody. My Naomi taught me to read. Then the Rector of St. Minver over to Trevose took an interest in me and he lent me books. Mr. Guy is a scholar and a gentleman, and he has a fine library. I have read nearly all his books. I know Shakespeare, and Milton, and Addison, and Steele, and Tennyson, and Shelley. And I know Kant, and Adam Smith, and Mill also. If these people here knew what I know and feel, they would burn me for a witch likely. And yet it is all for them; for their sakes I could make Tregarthen blossom like a rose. You may say that it does so now; but not always, not always. You are not laughing at me?"

She paused, with a sudden suspicion in her splendid eyes. Mary was touched, and even the loose lines of Miriam's mouth were quivering.

"I am very far from laughing at you, dear Ruth," Mary said gently. "I am going to try and do something for Tregarthen, and you shall be my ally. Yet it would be a thousand pities to see anything like trade or commerce here. Come, I see you have thought out a way to physical salvation."

Ruth sat down, and her eyes ceased to dilate.

"I have prayed for something like this," she murmured. The dying saffron of the day was on her face and glorified it. "You are rich, and you have told me you have Tregarthen blood in your veins. Don't leave us here to starve again. Fight Tregarthen; bring him to his senses. Make him understand that woman has a mission in life that is not all crystallized in the bearing and care of children."

"That is not original, Ruth," Miriam said demurely.

"I fancy it is Spencer," Ruth admitted. "But you know what I mean. The men here could grow the flowers and catch the fish, but we want something to fall back upon when the flowers fail and the pilchards are shy. We want summer, and spring, and autumn visitors; in fact, visitors all the year round. Rector Guy up to St. Minver came here to die of consumption three years ago. You will see for yourself what a testimonial to our air he is when he comes over to conduct service on Sunday afternoons. But what we want is some other staple industry."

Mary smiled. She couldn't help it. It seemed so strange to hear this glorious untamed daughter of the sea and sand discoursing learnedly of staple industries, and supply and demand, and the like. But Ruth saw nothing of this.

"Give us that and I will ask for nothing more," she said. "For the rest we are the model of a Christian commonwealth. We have no rents or taxes, we give a tithe to Tregarthen. The bad years he suffers, the good years he benefits. All we want is something we can work at all the year round."

Mary nodded thoughtfully. She looked from the climbing spume thundering on the cliffs away behind to the valley where the harvest of the flowers was going on. She felt the salt breath of the sea on her face. High overhead the gulls were calling. The boats of Trevose were drifting with the tide in the harbour.

"It must be something ideal," she said. "Something refined and dreamy. A Chicago man would recommend pigs. Fancy pigs in Tregarthen!"

"Don't," Miriam said. "Don't, Mary."

"Very well, I won't. It all comes of having a father who never talked anything but dollars, except when he varied his discourse with shares. Certainly we don't want any dollars or shares here. Painting or carving—perhaps children's toys. There is a good deal of latent poetry in Dutch dolls if you properly appreciate the subject. Then there is spinning; Tregarthen tweed, for instance, with the smell of the thyme in it. I could get Worth to make me a few gowns. What do you say to Tregarthen homespuns?"

Ruth looked up eagerly. The poor child had a wide and promiscuous education, but she was not of the world, and she had not learnt to laugh at things. The tragedy of the empty cupboard is a long way removed from persiflage that often covers an aching heart.

"Where are you going to get your sheep?" asked Miriam the practical. "I have a far better suggestion than that. Lace-making is the occupation for Tregarthen. Ruth, is the art lost in the island?"

Ruth looked up with scared eyes.

"Who told you about that?" she whispered.

"It is all in the diary I told you about this morning," Mary explained. "The art has been lost in Spain, but it was known here some century or two ago. Ruth, don't tell me the art is lost here also."

Ruth looked around her, fearful lest the birds of the air had carried the story. She bent to her companion eagerly.

"The art is alive," she said. "Tregarthen found it out four years ago, and all the pillows and bobbins were destroyed except mine. It was Naomi who gave me the lace of her own making, and I took it to Exeter and sold it for twelve pounds. That money kept Tregarthen for six weeks. But Tregarthen was furious, and Naomi destroyed almost everything. I didn't—I couldn't do it. Give us that industry, and Tregarthen knows sorrow and hunger no more."

"And you can do it?" Mary asked.

"I can do it," Ruth replied proudly; "but Naomi can do it better. And it's lovely. Shall I show you some of it to-night?"

"Vive la revolution!" Mary cried. "You shall, my dear, you shall."

And so the red flag of rebellion was raised.

THE four conspirators sat in Naomi's room. Ruth was uneasy, yet defiant, Naomi partly afraid, and with a look of shame that seemed strangely out of place on her frank, beautiful face. Mary and Miriam were calm. The door of the room was open to the cloister, for the night was warm, and the oil lamp cast lances of light upon the carved pillars, worn pavement, and smooth grass beyond. From the outer air, like the boom of a Titanic hive of bees, came the roar of the ground-swell. No light shone from any other cell, and it seemed as if they had the world to themselves. It was the eve of the revolution, and great events were to spring therefrom.

"My dear life," said Naomi. "I don't know when I felt so ashamed of myself."

"You are a darling," said Mary, incontinently and impulsively. "What wrong can you do by telling me the story of the lace?"

Naomi murmured that it was not loyal to Tregarthen. He had interdicted the thing, and she had promised to spin her fairy cobwebs no longer; indeed, the Protector was under the impression that the bobbins and stays, and the quaint old cushions, had been destroyed. He had nearly broken Naomi's heart at the same time; but it was a small matter. Flowers were all very well, but lace meant commerce and competition and the consequent moral degradation of all good and true Islanders.

That Naomi was an artist Tregarthen did not know. He was not aware that her whole heart and soul thrilled and glowed in those slender fingers and expanded in the poetry of her weaving. She had bowed her head uncomplainingly, but something had gone out of her life at the same time. Suppose you took away from Mascagni his music, from Poynter or Alma Tadema their brushes and pigments, and bade them paint no more, you would not harm them less than the autocrat of Tregarthen harmed poor old Naomi. She cared nothing for the lucrative side of her art—it was Ruth who had insisted upon that—she only loved the beauty of it, for this aged woman—ignorant and uneducated—was a Cellini in thread, an Angelo in silk and flax, and Miriam read her like an open book.

"It was a great deprivation to you," Miriam said quietly.

Naomi took the speaker's hand in hers and pressed it convulsively. A deep light was shining in her eyes. Over the bridge of years these two women came together and understood one another, and Mary divined what was passing in their minds.

"Ah, if you only knew!" Naomi murmured. "I loved it. My mother, who taught me the art, said I should make a better worker than herself, and maybe she was right. I began as a child; my fingers itched for the warp and the woof before I could speak plainly. Then I learnt to work without patterns; they came to me as I went along. I never thought about selling the lace, no such idea ever came into my mind. Sometimes one piece would take me as long as three years to complete. Let me show you."

Naomi was speaking fast and excitedly now. There was no fear of Tregarthen before her eyes. Here was an artist who for seventy years had lived neglected, and had at last found a critical and appreciative audience. She did not know that this was the happiest moment of her life, but it was. She did not know that she was going to show these strangers something beyond price, something that money could not buy.

She crossed the flagged floor, and opened an oaken cupboard in the corner. From this she produced a cashmere shawl (there had been wreckers on Tregarthen in the dark ages), and from its folds a small handful of black tangle. Then the tangle was thrown over the table, and covered it with a wonderfully fine silken mesh showing a pattern that might have come from the dainty pencil of Inigo Jones, or Pugin, or some of the great Italian designers. The pattern wandered over the cobweb apparently without beginning or end, and yet the design was perfect with a masterful, definite, dainty purpose.

Mary cried aloud in her delight. She had never seen anything so exquisite before. She poured out on Naomi a thousand extravagant but sincere compliments, she touched the diaphanous fabric as if fearful that it would shrivel up like butterfly down under her fingers.

"You wonderful creature," she said; "you did that yourself?"

"Without a pattern," Naomi replied. Her cheeks were glowing with honest pride, her eyes had grown marvellously young and bright again. "Five years it took me to do that. And Ruth doubts that it would fetch less'n a hundred golden sovereigns at Horton's to Exeter."

Mary caught the square and draped it round her shoulders. It might have been four feet square, but weighed no more than a thistle-down.

"You ridiculous old creature!" she exclaimed. "My dear creator, my very great artist, my original genius, you could not buy this in Paris for two thousand guineas! The art of the lace is lost, even the more antique stuff has no such texture and pattern as this! Naomi, you are an artist! With proper advantages your name would have been a household word in two hemispheres. Good Americans would make pilgrimages to see you. Noble painters, great connoisseurs, crowned heads would delight to do you honour. Your name would have lived in after years, as Benvenuto Cellini's has done. Ask Miriam, ask anybody who knows anything about it."

Naomi laughed, with the tears in her voice. The praise was music to her, as praise from the critic of understanding ever is to the artist. Matthew Arnold might have conveyed what Mary conveyed more subtly, but the homage of the ordinary to the great achievement Naomi properly understood.

"I am glad you like it," she said. "Keep the shawl, my dear, and welcome."

Mary sank speechless into a chair. She had to finger the lace about her shoulders to feel that the whole thing was not some delirious delicious kind of dream. And what could you do with a dear, absurd old creature like this? Mary's eyes were full of tears, that hung like crystals on her purple ashes. There had been the pain and joy and delight of conception and delivery—the mingled anguish and pleasure that goes with the production of good things—and she was only too pleased to see it pass into the hands of beauty and appreciation. She turned to Miriam doubtfully.

"What shall I do?" she asked.

"Keep it," said Miriam. "Some of these dark nights an American heiress will be missing from the deck of an Atlantic liner, and subsequently the delightfully personal young men on the New York press will be chronicling the fact in cold print that 'Miriam Murch is home again looking yellower and plainer than ever, and wearing a lace shawl that will make Fifth Avenue dudines sit up and purr.' Naomi, you have given our Mary a priceless gift."

"She looks like a picture in it," Naomi pleaded, with the air of one who asks a favour. "Let her keep it. I—I can make another."

"I dare say," Miriam said. "But when you are gone, who can do as well?"

Ruth looked up swiftly, defiantly. She had been honestly admiring Mary's soft fair beauty. Her own dark loveliness flashed gloriously by the side of it. Not till then had Miriam noticed her long slender fingers.

"I can," the girl cried. "Don't make any mistake about that. I'm not so cunning at it as Naomi, but I shall be in time. Let me show you."

From the old oaken cupboard she produced the pillow and bobbins and everything necessary for lace-making. A half-finished design was on the pillow. Directly the fascinated spectators saw those long fingers flashing and tossing amongst the bobbins they knew that the wandering art was safe here. The pillow was a large affair, a ponderous wooden block, but Ruth lifted it with ease.

"How strong you are!" Mary murmured.

"All the women are strong here," Ruth said indifferently. "That is because of the life we lead. But see here, Mary Blenkiron. This pattern came from one of the Spanish galleons wrecked here after the defeat of the Armada. Two were saved—the wife and daughter of Captain Don Jose del Amanda. It was they who taught Tregarthen how to make this lace, and the daughter grew up and married one Ambrose Pengelly, who was an ancestor of mine. That is why I am dark, and that is also why I am rebellious and quarrelsome, and lacking in proper respect, Tregarthen says. But Tregarthen cannot rob me of my art, and cannot prevent my helping the island next time trouble comes, and I will tell him so."

She stood up there Cassandra-like, defiant. She might have been the good genius of the island fighting for light and freedom. She made a wonderful picture as she stood there in the gleam of the lamplight.

"Not so loud," Naomi said fearfully. "If Tregarthen should hear you!"

A shadow fell athwart the open door and cut off the lances of light that played upon the brown stone cloister. Outside the booming of the sea seemed to rise higher.

"He has heard you," Tregarthen's voice said.

He stepped into the room, big, strong, majestic, with anger burning in his eye. He looked so regal, so masterful. And yet Miriam, who could read men, saw that the mouth was as the mouth of a dreamer often is—a little weak and irresolute. Most women would have been pleased to call this man master. With a little cry Naomi laid her white hands on the pillow as a mother might protect a child from danger.

"Don't be angry with me," she cried. "Don't be angry, Tregarthen."

Mary came forward swiftly. Her head was thrown back, her eyes were shining. This spoilt child of fortune had no mind to be treated like a schoolboy caught in an apple raid. Who was Tregarthen that he should lord it like this?

"Be not afraid, good people," she said, in her clear high-pitched tones. "There is nothing in the least to be afraid of. Naomi and Ruth have been showing me a specimen of their lacework, and instructing me how it is to be made. The piece I am wearing now is worth two thousand pounds. If you were not so blind and headstrong you would cultivate the gifts of your people and set them beyond the reach of want for ever."

Tregarthen started angrily. This was not at all the way to address a monarch on his own soil, and in face of his own people. But Mary was angry, and the right of free speech is the most cherished of American institutions. Tregarthen would have been loth to own it, but he never admired a woman more than he admired Mary at this moment.

"I have heard those stock arguments over and over again. I could sell my island and retire in comfort any time. With your western contempt for things established, it would be hopeless to make you understand. Be good enough to hand that lace to me. The rest will be destroyed to-morrow."

Mary paused in the reply that was intended to overwhelm Tregarthen once and for all time. The Great Secret trembled on her lips, but she remembered it in time, and all the passion died out of her heart. She would give this man his chance—she would give him every opportunity of coming to reason. She would spare him now, much for the same reason that Father Mackworth spared Charles Ravenshoe.

"You will do nothing of the kind," she said, with dignity. "I have a claim on these things, for I have purchased them. And if you destroy them by force I will bring an action against you in the English Law Courts. I shall prove that you have deprived me of a valuable discovery, and I shall sue you for £10,000. It will cost you double that sum from first to last, and where will your precious island be then? You will have to sell it, and your people will fight you in their new prosperity. Do you understand, Tregarthen?"

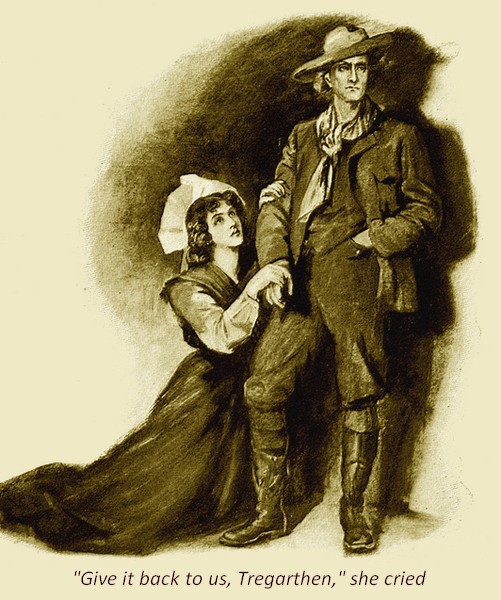

A shaft of common sense had touched him, for he smiled uneasily. There was a good deal of force in what Mary said, and a just monarch should ever be an upholder of the sacred rights of property. As he moved back Ruth came forward and threw herself at his feet. She caught his right hand to her lips, she burst out into wild and passionate speech.

"Give it back to us, Tregarthen," she cried. "Give it back to us, because we love it, and because it puts the bread into our mouths. Don't be hard, Tregarthen. Remember what happened two years ago. And the red light was on Tintagel as the sun went down; so help me Heaven."

Nothing could have been finer, or more intense and dramatic. Ruth had utterly abandoned herself to the feelings of the moment. She was a queen pleading on her knees for the lives of her people. Under the bronze of Tregarthen's face a red flush was creeping. Gently, yet masterfully, he raised Ruth.

"You must not kneel to me," he said. "You are forgetting. And if the red light was on Tintagel, the Lord's will be done."

He bent his head as if an unheard prayer had passed from his heart to the gate of his lips, then the mingled look of obstinacy and fanaticism that Mary had noticed before came over his face. He looked big and strong enough to ward off any disaster, and yet Mary felt that strength to be illusory. In an odd way she contrasted him in her mind with a fine piece of china, a handsome painted vase as yet unfused and hardened in the fire. Once through the furnace, there was the making of a man here.

Ruth turned away hopelessly. Her passion had spent its force as a wave beats itself out against the rocks. The promised land was in sight, the pilot aboard, and yet the captain deliberately swung his prow from the haven. Tregarthen turned to go, but Mary followed him. She came up to him, Miriam behind her, just as he passed beyond the shadow of the Sanctuary.

"You are bent upon this mad thing?" she asked.

"You are bent also on keeping the lace and the patterns?"

"Of course. Why destroy that which is priceless? Some day you will listen to reason—oh yes, you will, though you shake your head. What is the meaning of this red light on Tintagel?"

"The sign of a frost, sometimes severe, sometimes slight. If it comes badly all the flowers will be destroyed. In any case the flowers on the uplands must go."

"That is where the Lees' and the Hawkens' and the Braunds' cottages are. If their flowers are destroyed, what becomes of them?"

"They will retire for a time into the Sanctuary, of course."

"And yet you can prevent this? You have only to hold out your hand, and the tragedy will depart from the island for ever. You are the most wicked and selfish man I ever met in my life."

"I will not argue with you," Tregarthen retorted. "And I will not have any more of that lace manufactured in the island. You are not to return it to Naomi."

"I will not return those patterns till you ask me to do so."

"And that will be never."

Mary looked towards the sheaves of stars piled high in the bending dome, and she smiled. But Tregarthen could not see that.

"I will not return them," she repeated demurely, "till you ask me to do so."

She turned away as Tregarthen strode homeward, with a feeling that he had got the better of the argument.

"I shall have to conquer that girl," he told himself.

Meanwhile the others made their way back to the cells. Miriam was smiling demurely.

"There is a man who will have to be conquered," she said. "He imagines in his blind conceit and ignorance that he has got the best of our Mary. That exalted monarch does not know our Mary and the power she wields. It will be a pleasant surprise for him when it comes."

Mary smiled in reply, but dreamily.

"Do you know," she admitted, "I like Tregarthen. I fancy that I could become very fond of that man."

WITH the morning the great ground-swell died away, the grey swinging battalions no longer smote upon the cliffs, the boats were dancing upon the wrinkled blue bay. Out of a perfect sky the sun was shining, moreover the threatened frost had not come, for Mary had been upon the uplands before breakfast to see.

A kindly-looking man with grey hair and keen features stood talking to Miriam as Mary came up. His eyes were at once the eyes of a fighter and a scholar. His clean shaven lips were keen and humorous. His dress was a compromise between that of a parson and a sportsman, item, tweed trousers tucked into sea boots and correct clerical waistcoat and tie, item, a worn Norfolk jacket and a battered cap of sorts. A tall wiry man, keen as a hawk and kindly as a dove, a disappointed man who had been driven from the front rank by a physical disorder and forced back to pure air and quiet—for there are some who cannot live in towns. His disappointment had given a certain pungency to this man's speech. For the rest he who had once been in the running for a bishopric was perforce curate-in-charge of St. Minver 'up to Trevose,' where every man was a Dissenter and where the church congregation could be counted on the fingers. Thus the Reverend Reginald Guy, prince of gentlemen and best of good fellows.

"This is Mr. Guy, Rector of St. Minver," Miriam explained.

"Who has come begging, Miss Blenkiron," Guy explained. "Possibly the fact may not astonish you. A friend of mine says that the sturdiest beggars of all are to be found in the Establishment. But my alms are a favour. Lady Greytown, who is by way of being related to my wife, writes that you are down here for a time. We should take it as a great favour if you will come and stay with us for a day or two. We see so few people from the towns here excepting in the summer when Trevose has its complement of visitors. Will you come?"

Guy's tone was almost pleading. Mary understood the loneliness of these good, refined, educated people amidst the beauty and ignorance of the place. She looked at Miriam and nodded.

"We will come with pleasure," she said. "I was once on the Pacific coast for six months, after an illness, and I can quite understand your feelings."

They pushed off in the boat presently, having changed their dresses in defiance of Tregarthen. They were good women and original ones, but they had not the sheer audacity to present themselves to Mrs. Guy in blue woollen frocks, the waists of which were under their arms. Then they landed on the long razor-backed piece of sand that constituted Trevose harbour, where the fishermen were lounging with the boats pulled beyond high water. The fishers stared coolly yet not insolently, but never a one lent a hand to parson's boat though they accepted his speech with benign toleration. On the whole Mary gathered the impression that they were sorry for him.

"Are they intolerably rude or intolerably lazy?" Mary asked. "Is there some blistering sin for a Dissenter to help a Churchman?"

"Not a cardinal sin," Guy smiled. "I dare say they would look for forgiveness in time. The men condescend to speak to me, they come to my reading-room and use my bagatelle board and smoke my tobacco. But it is tacitly understood that I am in no way to tamper with their spiritual welfare, or lead them towards Romish practices. The parson has his uses all the same. He is expected to approach Lord Greytown when they want anything, he has to get up subscriptions when there is a boat lost or the nets have to be abandoned. In the summer all the people let their houses, and every prospective tenant is referred to me. I write something like five hundred letters every summer."

"And yet they won't touch your boat," Mary said.

"Well, they are a queer people. Till I came down here I had but a hazy idea what independence of character means. And they are proud. It is their constant boast that they are Cornishmen. Now, I can understand a man being proud to call himself a Briton, or else a Scot or Irishman. But why this conceit because one happens to see the light on the peninsula called Cornwall?"

"Pretty, but poor," Miriam said. "A county tied up with bits of string. But you didn't tell us why they refused to handle your boat."