RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

THE great painter stood out from the rest of his guests like a flash of sunlight on the dense blackness of a pine forest. He had ever been a man whose rod swallows all the rest. A placid smile played about the clean-shaven, sensitive mouth. Prince of painters and courtiers alike, Lord Falconridge was a personage: he was an onyx pillar supporting the cerulean canopy of Society.

Falconridge's conviction that he himself was an institution gave an added charm to his fascinating personality. No god can nod more charmingly than Jupiter. And here was the Jove of modern painters, gifted, imaginative, with a pencil that drew and fascinated immensely withal.

Favoured mortals who had the entrée to Kensington House Terrace would have found it difficult to describe Falconridge's lordly pleasure house there. They could babble incontinently of Corinthian capitals, marble halls, and flashing fountains. As to the rest it was too harmonious for any single object to fix the retina. Visitors carried away with them a pleased memory of marble and an atmosphere of scarlet, toned with the tender greens of palms and lemon trees.

That dash of crimson vividness appeared to be the keynote of Falconridge's life. It formed part of his individuality. No picture of his was complete without it, the loose Byronic knot at his throat was always of red silk.

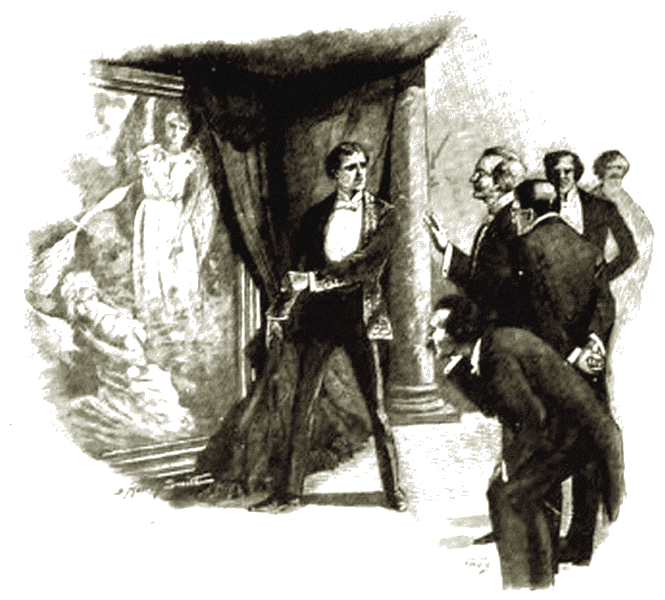

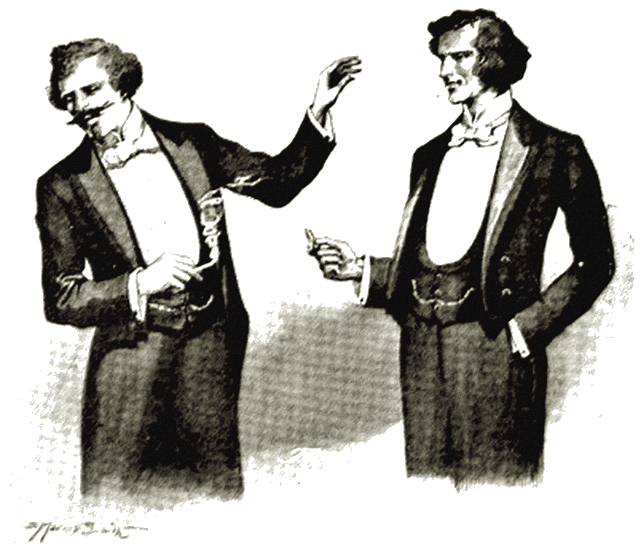

"Dost like the picture?" Falconridge quoted gaily. He stood at the top of the great studio, a noble and stately figure in evening dress, rendered all the more striking by the embroidered velvet coat he wore in lieu of the claw-hammer garment of conventionality. An air of romance like a faint perfume clung to that coat. Falconridge had had his affairs, both great and small, and as to the jacket in question, like Prince Arthur's kerchief, a "princess wrought it him." The rest of the story matters little, but the coat was as well known as a certain statesman's orchid.

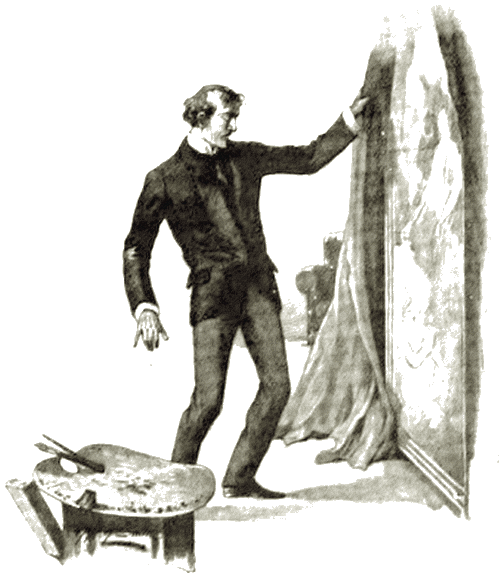

No one replied to the host's question for a moment. They were critical, those people standing there contemplating the glowing canvas from which Falconridge had drawn back the black curtains, in fact they had come on purpose to see the picture.

This curiosity might well be pardoned. The painting in question was like to become historic. Certainly Falconridge had never done anything finer. The sixtieth year of Her Most Gracious Majesty's reign seemed to have fused his genius there. The picture was at the same time a memento of the most glorious reign in history and the crowning work of the painter's career. A subdued triumph illuminated his face. As to the picture it was naturally an allegory. Peace with flaming sword rose out of the west and chased the powers of ignorance and darkness before her. The imagery, the boldness, and the delicacy of imagination matter little. Falconridge could see the answer to his question depicted upon the features of his guests.

"I should like to know what Gabriel has to say," he observed.

Gabriel, the leading art critic of his time, stepped forward. He spoke slowly.

"To reply off-hand would be foolish," he said. "You can't really judge a man by first impressions, to say nothing of a picture. I must come again and make the acquaintance of your latest creation at my leisure, Falconridge. There is something in it that I recognise as a new note in your work, and one striking peculiarity."

"I am going to learn something," Falconridge said with charming egotism. "What is it?"

"There is absolutely no crimson in your picture; for once the scarlet streak is missing."

"There is absolutely no crimson in your picture."

One of the black curtains fell like a pall from the artist's slim fingers. His face underwent a swift and terrible change, the lips were grey as ashes. He swayed like a poplar in the wind. Then the storm faded and he was himself again.

"A passing faintness," he murmured, "the heat of the room. No, I am all right now."

Back from the group gathered anxiously around Falconridge stood Victor Colonna. The atmosphere of the studio struck him as being delightfully cool and fresh. Obviously Falconridge must have been out of sorts to tender an excuse like that. Why then had Gabriel's discovery affected him so strangely.

"Sir, did you notice that, did you see?"

There was a painful ring in the speaker's tones. The hand laid upon Colonna's arm crushed unconsciously into the muscles like hooks of steel. Colonna turned to the speaker, a young man with an eager, intelligent face which seemed to suggest a close acquaintance with trouble and care.

"I saw something that surprised me, certainly," Colonna replied guardedly; "and you?"

"I have seen the devil. My God, how good he is to look upon—"

The words came thrilling with the passion of despair. A sane man suddenly conscious of the taint of homicidal mania could have expressed great mental anguish no more terribly or realistically than the speaker. Before Colonna could recover from his surprise the other had turned and plunged into the crowd.

Colonna followed at a respectful distance. His curiosity was piqued. On one side o the studio stood a bower of ferns, behind which a dimly shaded red lamp cast a pallid ray on a tinkling fountain. Here Colonna could watch.

Presently he saw Falconridge dexterously detach himself from his guests and come leisurely in his direction. Then Falconridge shot behind the screen of ferns. Colonna would have betrayed himself but for the strange, the guilty look on Falconridge's face. That the latter deemed himself to be unobserved was certain. There were heavy beads of moisture on his forehead. A tiny Japanese cabinet stood near. From this Falconridge drew a syringe, which he charged from a phial, and drawing up his sleeve, injected the morphia into his arm. A minute later and Colonna was once more alone.

Falconridge injected the morphia into his arm.

"Strange," he muttered; "strange that my suspicions should be confirmed. That wonderfully calm manner, the lustrous, steady gleam of the eye they all admire, have more than once suggested certain theories to me. And what a dose! This kind of thing must have been going on for years. And yet it would hardly account for that sudden guilty fear. The skeleton in this lordly palace must of necessity be a grizzly one."

Colonna drifted out amongst the other guests again. By this time they were scattered into groups, a violet trail of cigarette smoke drifted on the air, a pair of footmen passed along under a clinking load of crystal and old silver. An aged savant looked up from under a pair of penthouse brows as Colonna passed, and signalled him to his side.

"Sit down," he said; "I have something to say to you."

"And I have something to say to you, Paget. I have made a discovery."

"Ah! we are both thinking of the same thing. You know what is wrong with Falconridge?"

"My dear friend, I have just seen a dose of the morphia injected. I have had my suspicions for some little time. Is there insanity in our host's family?"

"You have partly hit it. I know I can trust you, Colonna. For three generations the curse of the Falconridge race has been dipsomania!"

"But our host is a staunch total abstainer."

"I know it. So were his father and grandfather before him. They were all men of iron resolution, but there are times when that craving cannot be fought down. Hence the morphia. The secret has been well kept."

"But it cannot possibly continue to that extent, Paget. You should have seen the dose! The creative faculty must be sapping away, and at this rate the nervous power of the draughtsman must decay. And yet, yet I never saw any work by Falconridge to compare with the picture we saw to-night."

Professor Paget looked cautiously round him before he replied.

"Do you feel quite sure, my friend," he whispered, "that Falconridge did paint the picture?"

Colonna started. A flash of lightning seemed to reveal before his mental vision a strange truth, a clarity merged into the black darkness again. A demon such as possessed Falconridge was certain to beat him to his knees in time. The artist would cling to himself as long as possible. And this picture had been talked about and promised for a year or more, though none knew but vaguely what it is was likely to be. For Falconridge to have failed in this endeavour were to stand in a white sheet and proclaim chaos.

Colonna could faintly picture the grim struggle in this palace between Falconridge and the invisible power waiting to drag him down. And then, by a curious parallel line of thought, Colonna found his mind drifting in the direction of the young man who had so startled him earlier in the evening. Colonna pointed him out to Paget.

"Who is the young man with the Rembrandt face?" he asked.

"Oh, that is one Walter Holyoake, an artist," Paget replied; "a man of originality and ideas, they tell me. The cults admire his work, but the public is not sufficiently educated as yet. I am afraid Holyoake has a bitter struggle."

Colonna pursued the conversation no further. There was no occasion to disclose to Paget the theory that was rapidly shaping itself in his mind—indeed, to do so would be to proclaim an outrageous absurdity. And Paget was nothing if not practical. Holy Writ to him was only Holy Writ so far as it could be proved.

Colonna moved away presently and passed into the hall. By this time the guests were thinning down. Presently Holyoake came out and took his hat and coat from one of the footmen. He bowed slightly to Colonna as he passed.

The latter followed a minute later. A sharp walk brought him up to Holyoake.

"May I stroll with you a little way?" he asked.

"The pavement is free to all, Dr. Colonna," was the reply. "Pardon me if I seem discourteous, but if ever a man was tortured by devils, I am that man to-night. And I am utterly powerless to prove that I—"

Holyoake paused abruptly. Under the pallid rays of a gas-lamp Colonna marked the exhausting agitation of his companion's face.

"Perhaps I can assist you," he suggested quietly.

A bitter laugh broke from Holyoake's lips. His face froze again.

"Maybe," he said indifferently, the indifference of despair; "and maybe you would accept my story with the contempt such a narrative deserves."

"Perhaps I know more than you give me credit for," Colonna responded. "May I be permitted to make a suggestion? You have suffered a great wrong from the hands of a man you have hitherto regarded as friend."

"A wrong! In the whole catalogue crime there has been no viler thing than this!"

"And at the same time you find yourself utterly powerless."

Holyoake shuddered from head to foot. He was evidently controlling himself with a effort.

"Utterly," he replied.

"Supposing that the Prince of Wales picked your pocket, and thus deprived you of all you had. Oh, know the mere suggestion sounds like that a madman. 'Fore heaven, I am nearly mad. But supposing that such a thing happened. What could you do? Lay an information, apply for a summons? Nothing of the kind. That would be to become a derision in the market-place. The boys would jeer at you in the street. Well, something of this kind has happened to me. Would you laugh if told you that Falconridge never laid a brush on the picture you saw to-night."

"No, I certainly should not laugh at you," Colonna responded.

"Sir, I am infinitely obliged. You give me courage to proceed. I propose testing your sense of humour still further. Suppose I say that I painted the picture and Falconridge stole it from me. Ah!"

Holyoake hung breathlessly on the reply. Sympathy was absolutely necessary to him at that present moment. When Colonna spoke he drew a deep breath like a swimmer who emerges after a long dive.

"I should believe every word you said," Colonna answered quietly. "To say the truth, I had partly guessed this already. Now let me hear your story. We are close by my rooms—-will you come in for half-an-hour?"

Holyoake responded gladly. The story he had to tell over a cigarette was a very simple one. The artist was an Australian who had bitterly annoyed his practical father by giving up to Art what was obviously intended for the tinned-mutton industry; there had been a quarrel and a subsequent truce upon terms. With a certain amount of money Holyoake was to come to London and there devote himself to Art for four years. If successful at the end of that time, well and good; if a failure, Holyoake was solemnly pledged to return and take up the business.

"It has been a struggle," Holyoake concluded. "More than once I have had practical lessons as to how the pawnbroking industry is conducted. The four years are nearly up, but success seemed assured at last. For a year I have devoted every spare moment to my picture; it has become part of myself. I have said nothing about it to a soul—until to-night no strange eye has seen the picture but Falconridge's. It was a bold stroke to call and ask him to come and view my painting, but, like a good many audacious things, it succeeded. Falconridge was quite enthusiastic in his praise. He offered me a corner of his studio where I could finish my work, and I accepted the offer gratefully. And then to-night he sprang that mine upon me. The colossal impudence of the whole thing was paralysing. I stood there dazed, doubting my own sanity. I was frightened to speak. And the more I thought of it, the more frightened I became. What could I do? To denounce that man or claim my own would have got me laughed out of the house—it might have even ended in my being handed over to the police. Consider the gulf between Falconridge and myself. Had I made such an accusation, not one soul out of all the millions in England would have regarded me as anything but an impudent impostor."

Colonna nodded thoughtfully. He read the position exactly. Unless something unforeseen happened, Holyoake was absolutely powerless. The refined cruelty of the crime stirred Colonna to a feeling of indignant scorn. Here was a case where the vellum scroll with the silver clasps would prove useful. The secrets of the Borgias should be applied to restoring to this honest man his own. In a few minutes Colonna had practically mapped out his plan of action.

"Have no fear," he said; "put your trust in me and this grievous wrong shall be repaired. Not only shall your picture be returned to you, but Falconridge shall do penance in a white sheet. Indeed, there is no other way out of the difficulty. Look at this."

Colonna produced from a small iron safe in the wall a lead tube such as oil paints are packed in, and, squeezing a tiny portion out, handed it to Holyoake.

"Smell," he said, "now put it down at once. What sensation are you most conscious of?"

Holyoake shuddered from head to foot. He opened his mouth as if to speak, as if something were struggling for utterance against his will. Then the feeling passed.

"I feel a wild desire," he said, "to tell you my secret thoughts. My God! fancy the soul of even the best of men being laid bare for inspection! He would never be able to look a fellow creature in the face again, and that was my sensation. Doctor, put that accursed stuff away."

"Doctor, put that accursed stuff away."

Colonna did as desired. There was a quiet smile of triumph on his lips. But what caused that smile he did not deem it necessary to tell Holyoake.

"You may go now," he said. "Are you one of the select who are asked to Falconridge's dinner on Wednesday week? You are! Then upon that evening you will have your own back again. I hope you have a steady nerve, for assuredly you will need it."

COLONNA came up from the sea at Sandmouth fresh and glowing like Aphrodite after his morning bath. There was no evil in his mind, his heart was free from worldliness. But all the same a faint smile flickered on his lips as he passed a bungalow smothered in roses to the quaint crest-tiles. There was a deal of "darling sin" about the place—a mixture of humility and costly refinement.

"Dives playing at Lazarus," Colonna muttered; "and yet there is no more miserable man on earth to-day than the owner of yonder place. I—"

At the same moment the door flew open, and a tall figure still in evening dress stood there framed in the creamy, dewy heads of the roses. Colonna crossed the road as Falconridge, for he it was, called him.

"The very man," the latter said hoarsely, "I have already been to your rooms."

"What is the matter? You look like a ghost."

"Man, I am suffering fearful tortures. I cannot sleep. There is nobody in the place awake yet besides myself. Come in."

"You want me to do something for you?"

"Assuredly I do. I know you are a wonderfully clever man, Colonna. I am not likely to forget that marvellous lecture of yours. It struck me just now that you might succeed where all those Harley Street people have failed."

Colonna nodded. He knew perfectly well what was the matter with Falconridge. The demons morphia and brandy were getting at deadly grip even with that grand constitution; the final struggle was not far off.

"Change your coat and come round my rooms with me," Colonna suggest "I can put you right for the present. You must be yourself for your special dinner Wednesday. Holyoake comes down for a function to-day, and will be my guest after Thursday."

Falconridge murmured something. It was evident that the mention of Holyoake's name had not left him unmoved. No other word escaped his lips till he found himself at length in Colonna's sitting-room facing the sea.

"One moment," said the latter; "the bottle I require is in my bedroom."

The speaker returned presently with small medicine-glass, half-filled with some evil-looking decoction like printer's ink. With a shudder Falconridge gulped it down. It seemed to revolt against his very soul.

"What awful stuff," he said, "it is drinking death." The nausea, however, was transient as summer lightning. The vile glare of the sufferer's eyes gave place to a clear luminosity, the bland courtier-like tone returned.

"Why can't the others do this for me?" he said. "Colonna, I am a man again, upon my word, for the first time for three years."

"Except late in the evenings," Colonna said quietly.

"What do you mean by that remark?" Falconridge demanded.

"You know perfectly well what I mean. What is the use of coming down to your place here unless you leave certain evil habits behind you?"

"So you have penetrated my secret! Well, it matters little, for the whole world will hear of it sooner or later. The thing is hereditary, Colonna. Of my struggles against it I shall say nothing. Still, I have had everything the world can give me. I have painted a great picture, and—"

"But Truth says the picture is not quite finished, and that you brought it down here to put on the crowning touch."

Falconridge nodded somewhat gloomily.

"Correct," he said. "There is a touch two I cannot get quite to my mind. But I hope to finish by Wednesday, and my dinner that night will be as the launching of the ship. The thing sounds very absurd, but I cannot get my crimson streak right. I'd give £1000 for one brushful of the real Titian brown-red."

"And suppose I could supply it?" Colonna asked. "I hold the secrets of bygone generations, you know. And the Borgias were ever patrons of the arts."

Falconridge looked up bright and eager as a schoolboy.

"If you only could," he exclaimed. "I want red with tenderness in it. It would be a new keynote, it would stamp the picture on the face of this generation. But you can't do it."

"I can, and will," Colonna responded. "You shall have the tubes this afternoon. You take my advice and go home quietly to breakfast."

THE Last of the Borgias was good as his word. Late in the

afternoon he left for Falconridge, two tubes of colour in a

compact case, one below the other. They were so packed, because

it was necessary to the scheme that the top tube should be used

first.

It was close on the dinner-hour, when Falconridge burst excitedly upon Colonna.

"I have done it," he cried. "I have succeeded beyond my wildest dreams. Colonna, you are a marvel; those colours are inspiration. Come, and be the first person to see my picture now it is really finished."

"You have got the crimson streak to your satisfaction?"

"That is but a faint way of expressing it. Come and see for yourself."

There was no great way to go, and Colonna complied willingly. Falconridge led the way through his little paradise to the studio beyond. There stood the picture in a strong North light, a curtain dropped on the frame.

"Now you shall see what you shall see," Falconridge cried. With eager hand he flung the canopy aside and pointed to the frame. As he did so the triumphant expression of his face changed, the smile was frozen on his lips. The bold crimson touch had utterly disappeared.

The bold crimson touch had utterly disappeared.

"I see nothing that I have not seen before," said Colonna.

Falconridge said nothing for a moment. His agitation was pitiable to witness. He attempted to speak, but no words came from his parched lips.

"Colonna," he managed to gasp presently, "I am going mad. What I told you just now must have been a mere figment of my imagination. And yet there is the brush, and there is my tube half-spent. This is a judgment upon me."

"You have been drinking again?" Colonna demanded.

"Well, yes," Falconridge confessed. "I felt so well this afternoon. And I-I—well, I could not keep away from it. There was the morphia also. People envy me—me! If they only knew what a miserable, helpless wreck I am!"

As he spoke Falconridge flung himself into his chair and cried as a child. Tears like those betrayed the utter weakness of the man. Colonna was touched, but there was in his mind no hesitation as to the course he had mapped out for himself.

"You are in an extremely bad way," he said. "These delusions, coming like this upon complete prostration, point to a very grave state of things. Doubtless you used that pigment elsewhere, and imagined that you had finished the picture. If you will take my advice, you will keep away from the studio till after Wednesday, and see as much cheerful society as possible in the meantime. Otherwise you may find yourself 'completing' your picture in a manner other people would call mutilation. Come, let me turn you out of here, and take the key with me."

Falconridge raised no objection to this somewhat arbitrary suggestion. Colonna left him in the conservatory moodily plucking the red heart out of a rose.

"A thousand pities," Colonna mused, "a thousand pities. But nothing can save that man now, and I might as well see this wrong righted. What a state his nerves must be in to allow me to fool him with that transparent juggling."

AS Colonna entered his sitting-room Holyoake rose to greet

him.

"I am here, you see," he said eagerly. "How are you progressing?"

"The reeling out of the line leaves nothing to be desired," said Colonna, with sardonic gravity. "I am slowly plucking the life out of a great soul. Make no mistake about that, Holyoake. Falconridge has fallen—he has succumbed after years of strife with an enemy that would have torn your heart out in a month. You will never be such a man as that. Still, justice is going to be done."

"You feel sanguine of success, Doctor?"

"Success is as certain as that you are standing there before me. If you will listen, I will tell you what has been done already."

Holyoake listened eagerly enough, but it was plain to see that he was puzzled.

"I must confess I quite fail to understand," he said. "Do you think that Falconridge really tampered with my picture?"

"I am absolutely certain of the fact," Colonna replied. "You are still utterly bewildered. If he had done so, the Titian red would be there. How the thing was done must be my secret for the present, but I will explain all in good time. As I have the key of the studio in my pocket, Falconridge is not likely to touch your picture again till the night of the dinner. I shall see that he is all right for that occasion, and after dinner the crowning stroke will be given. The success or failure depends upon one simple act of audacity of yours, if you have the courage."

"Courage—when my whole ambition, my assured future is at stake!"

"Good!" Colonna exclaimed. "I like to hear you talk in this fashion. What you have to do is extremely simple. When I give you the sign, act."

"Certainly, if you will tell me what I have to do."

Colonna gave certain short and vigorous directions. It was evident that Holyoake grasped them; it was equally evident that he fully intended to act upon them. But his astonishment was none the less great, for surely conditions so wild and extravagant were never laid upon a man before.

"It is like being in league with the devil," he said. Colonna smiled grimly. He appreciated the compliment to his powers.

"Then mind you act the part of Faust well," he said, "and without any of the vacillation displayed by that individual."

Holyoake rose and grasped his companion by the hand. A great light of resolution flashed like blue steel in his eyes.

"I am fighting for my child," he said "You will not find me wanting."

SHADED candles cast pools of light on the damask sea. Here and there a decanter stood like the ruddy glow of a beacon, pyramids of fruit made a refreshing spot for the eye to dwell on—artistic oases rifled of their sweetness. Dinner was a thing of the past, and already the diaphanous blue of tobacco floated over the table.

At the head of it Falconridge lounge gracefully. Never had he been in better form, but how the transformation was brought about only he and Colonna knew. Holyoake restless by the doctor's side, regarded his host carefully.

"I did not expect to see him quite thus," he said.

"No!" Colonna smiled. "He looks like an antagonist worthy of good steel now. You should have seen him this afternoon. But have no fear. The cordial administered by me will soon lose its effect; indeed, it has done so now, but you may have noticed the amount of champagne consumed by our host. Patience, my friend."

Holyoake had not long to wait. Soon the conversation drifted round to art, and the picture cropped up again. To-night was to see the last touch laid on, and the morrow would transfer the glowing canvas to London, where it was destined to be come the cynosure of countless admiring eyes. Most of the guests were in the studio by this time. Falconridge's palette and a half-spent tube of the Titian red lay close at hand. The artist smiled as he turned back his cuffs and took up a brush. And yet Colonna could see that his hands trembled strangely. Would the occasion be successful, or would that transient colour fade as before?

Still, it was no time for hesitation. Falconridge nerved himself for the effort. He squeezed a little of the moist pigment out on his palette, and as he did so Colonna stepped forward and laid a detaining hand upon his arm.

"That rare colour is cheap enough to me," he said. "An occasion like this is worthy of a fresh tube. You will find the second one in the case a little better than the first. Would you oblige me by trying it?"

Falconridge complied with one of his most courtly smiles.

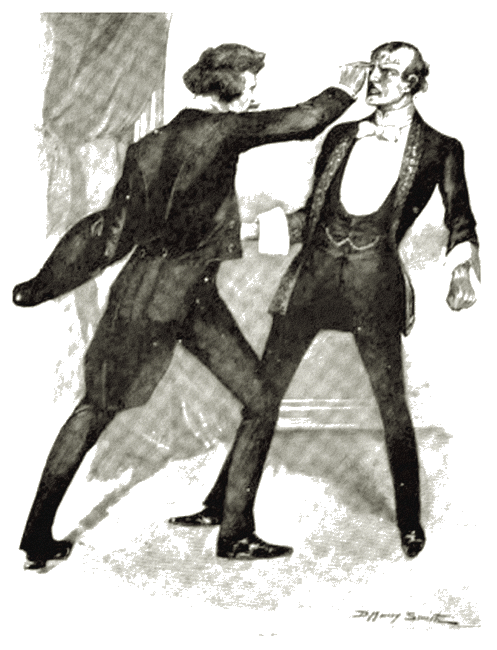

"It will be a fitting crown to the work," he said. Colonna turned and favoured Holyoake with a significant glance. The latter came forward, pale, but grimly determined to carry out the instructions Colonna had given him.

"It seems to me," he said quietly, "that the work could be in no better hand than mine."

There was a note of challenge in the tones. Falconridge accepted it promptly. A feeling of deadly sickness came over him, yet he braced himself to the fray. Surely he had strength and resolution to bear this fellow down.

"I hardly understand," he said with a smile. "Your jest is a little out of place, Holyoake, even if it is an after-dinner quip. Still, if you feel equal to the task——"

Holyoake took the proffered brush and palette amidst angry murmurs. With the pencil well charged, he advanced to Falconridge, and, with a quick, nervous touch, branded him across the forehead with the red legend: LIAR.

branded him across the forehead with the red legend: LIAR.

The effect of this monstrous insult may be imagined. Falconridge stood there white to the lips, and trembling as with ague. In a glass opposite he could see the crimson brand sear like letters of flame on the white flesh.

"Stand back," Holyoake cried. "What I have painted there is true. This picture is mine, I painted it, and Falconridge stole it from me. Ask him if it is not so."

Every eye was turned upon Falconridge. He seemed to be fighting down some impulse—he might have been struggling with some unseen foe. He fell upon his knees beaten there by the spiritual antagonist, his manner changed to the calmness of despair.

"Holyoake is right," he said, "he speaks the truth. What power it is that impels me to make this statement, and thus bring ruin and humiliation upon myself, I cannot tell. For three days now the impulse has been strong upon me, and I struggled against it with all my strength. But I can fight no longer—some occult power seems to drag the truth from my lips. I stole that picture."

A silence that could be felt followed this statement. Polite incredulity was stamped upon every face. As Falconridge noticed this he smiled bitterly.

"No, no," he resumed; "I am not mad—yet. That horror has still to come. And whilst I am about it, let me make full confession."

Falconridge spoke on for some time, sparing himself nothing. He told of the disease in his blood, and how it had finally conquered. He told how he had promised this picture, and how his talent had suddenly failed him. Then he proceeded to show how temptation and opportunity together had brought about his fall.

"The rest is silence," he concluded. "I shall paint no more because I cannot, and from to-night the world will know me no longer. Clear the room, gentlemen, if you please. The door shall be locked, and the key given to Holyoake to fetch his picture when he pleases. And believe me, my young friend, when what has happened comes to be told, your reputation will be none the worse for it."

Holyoake would have spoken, but Falconridge thrust him aside. Then he passed the stairs to his bedroom and the door bang sullenly behind him.

"I AM eager for the explanation," Holyoake said impatiently.

"It is very simple," Colonna replied, "especially as I had a man to deal with whose nerves were in a painful state of tension. Certain people find it hard to keep a secret, and Falconridge is one of them. You remember how Eugene Aram confided his crime to the schoolboy. That is the moral of this story. Everybody knows that a man in liquor will tell anything—it is a mere matter of more or less alcohol.

"By a little trick of my own I played upon Falconridge's nerves. The paint I gave him gives off fumes that affect the brain. Do you remember when you smelt it, the subtle stuff seemed to draw your soul from you? The were two tubes of that stuff, the first being fugitive colour.

"When Falconridge tried the paint on your picture, and found it subsequently missing, he was terribly shaken. But all the time the fumes were getting into his system, and when you laid on that dramatic touch of the pencil, the poison conquered. The stuff would have forced the truth from Hercules. You saw how Falconridge struggled to throw off its effects. You might as well try to sweep back the tide with broom."

"What do you call it?" Holyoake asked.

"Essence of hypnotism," Colonna smiled, "which is quite as good a name as any other, and at any rate that is what it is in effect. Holyoake, I am more sorry for Falconridge than words can tell. Still, what has happened is no bad thing for you, for you will use the body of that man as the stepping stone to fame. How often this happens in the tragedy we call, for the want of a better name, Life."