RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

THE curtain had just fallen on the second act of Die Meistersinger; de Resske's flute-like tones still seemed to linger in the fretted roof. There was a rustling of fans, a shimmer of satin and gloss of pearls as the audience, released from the spell, rippled into conversation. Colonna lounged in his stall, contemplating the brilliant mise en scène as one does a striking picture. Then he turned to his companion, a slight little man with restless eye and quick, vivacious manner.

"Is the mouse in the trap yet?" he asked.

"Oh, yes," replied the other, who was no less a personage than Sir William Wallace, the great Political Economist. "That is the man in the third box of the grand tier."

"Indeed, he looks a mere boy."

"Young as he looks, Baron Rosalba is nearly forty. Our Cyclopean financiers 'arrive' early nowadays. A most dangerous fellow, Colonna—a genius beyond question, with a nerve of steel and the heart of a tiger where his personal interests are concerned. If he succeeds in his present undertaking, England is doomed."

"So bad as that!" Colonna murmured.

"Oh! I am not exaggerating," Wallace responded gravely. "Consider how Rosalba squeezed our working classes over the Oil Trust. This other affair, of which I got wind quite by accident, is a far more serious thing. If Rosalba is successful, he will control the price of grain and breadstuffs for Europe for years to come. If he liked to say the word we should practically be deprived of bread. Consider for a moment the awful consequences of such a thing. Why, that man would be in a position to make terms with us like a conquering sovereign. Frankly, I am frightened, and that is why I came to you."

"Quite so," said Colonna. "If Rosalba were removed——"

"Oh, I don't quite mean that!" Wallace said, hastily. "There are more ways of killing a dog than hanging him. If you could cripple that audacious intellect, for instance, or—well, you know how fine is the line between genius and insanity. A tiny pebble cast into a piece of intricate machinery is quite as destructive as a thunder bolt. You take me?"

"Perfectly," Colonna responded. "The process will be expensive."

"My dear fellow, money is no object whatever."

"Very good. You will so arrange it that I can draw what money I require without trouble or delay. As to the rest, everything must be left entirely to me. All I ask you to do is to bring my intended victim and myself together. You know Rosalba intimately, you say. Can you tell me if we have anything in common?"

"One thing in sympathy between you I can mention offhand," Wallace replied. "Rosalba has a craze for the collecting of rare and quaint curiosities. He is quite a connoisseur like yourself. I cannot think of anything else."

"It will suffice." said Colonna. "And the sooner we meet the better."

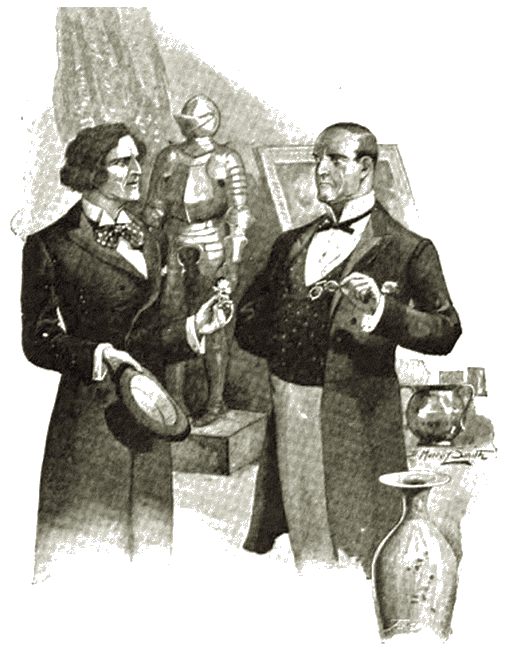

COLONNA came slowly down the marble steps leading from

Wallace's town house into Palace Gardens, and took his way

eastward. He had left behind him a most congenial luncheon party,

conspicuous amongst whom was Rosalba. A casual conversation on

matters ceramic and artistic had drawn the two men together.

Colonna did not need to be reminded that a difficult task lay

before him, and from the doctor's features it was evident that he

was puzzled.

"Yonder man is the cream of a million," he muttered. "Quiet as a cat, and yet as cruel and relentless where his own ends are concerned. And yet in ten minutes I could reduce him to a babbling idiot for life. Still, one does not care to take a bludgeon to fight a master of fence. How to proceed for the present I know not."

Colonna had thought out a dozen schemes only to abandon them directly. Defeat irritated him for the moment, and retarded the process of deglutition. He resolutely put the thing out of his mind for the present. He strolled along Oxford-street thence along Bond-street, where he was accosted by a tradesman who came out of a certain shop with an eager air. Most people know Tregold's, that veritable museum of all that is rare and curious.

"Have you got something to show me, Tregold?" Colonna asked.

"Well, sir, I didn't think of you," Tregold responded. "But when I saw you looking into the window it struck me you might like to see a little thing I picked up yesterday. I can't give it a name for the life of me."

Colonna followed into the dingy shop with eagerness tempered by the caution of the collector who had grown veteran in the battle of bargains. Tregold produced from a little wash-leather bag a perfect gem in the way of silversmith's work. It was an exquisite rose, with two sprays of leaves, the flower itself being hammered gold. Evidently the thing was of medieval design.

"What do you make of it, Doctor?" the dealer asked, eagerly. Colonna's eyes flashed. Otherwise he preserved his outward calm. "It would be difficult to say," he replied. "Symbolic, I should imagine."

"Only one cannot authenticate it. If I did not know where every single specimen was at the present moment, I should say one of the Papal 'Holy Roses' had fallen into my hands. Very likely this is a copy of the one sent by the Pope to Charles V. of Spain. In that case its value is by comparison small."

"I am prepared to purchase it at a price," Colonna said, tentatively.

"I am prepared to purchase it at a price," Colonna said, tentatively.

"And, upon my word, I don't know what price to say. Two hundred guineas?"

"Say a hundred and fifty. It is what you people call a pig in a poke, you know."

A few minutes later, and Colonna passed out of the shop with his new treasure in his pocket. He felt the extravagant pleasure of a child with a new toy. Then he hailed a cab, and was driven homeward. Once there, he laid the exquisite rose on the table and contemplated it with sparkling eyes.

"What a treasure!" he exclaimed. "And how fortunate that my family volume should contain an account of this unique thing. What it would fetch, properly authenticated, Heaven only knows."

Colonna took the curio from the table and gently pressed the head of the stem, at the same time taking care to keep his hands well free from the flower. It was well he did so, for from every petal there darted a thin sharp tongue of metal like a curved needle. Each needle on close examination proved to be hollow. Directly the pressure was taken off the stem they disappeared once more.

"No question about it," Colonna muttered. "It is the veritable thing itself. And——"

Colonna dropped suddenly into a chair. The inspiration he had been seeking came upon him like a blinding flash. The idea was so stupendous that it almost overpowered him for the moment. In an instant the whole scheme in its minutest detail lay like a map of fire upon the grey tissue of the brain. Rosalba was doomed now.

"The instruments are to my hand," said the plotter, "every puppet in its place, and I have only to pull the strings. Carmen is more or less in my power, and in any case she would do anything for money. She shall be the dainty bait in the gilded cage, and Rosalba shall enter it with his eyes open."

Then Colonna took down a medical treatise from a shelf and became engrossed in its pages until it was time to dress for dinner.

EVERY London season sees one or more brilliant comets

flash across the all too brief empyrean and fall into the

boundless darkness again. And in the present year of grace

perhaps the most coruscating meteor was Carmen Clay. A beautiful

and talented actress, the wife of an American millionaire, Carmen

had taken London by storm. The mere fact that she and her husband

were not on speaking terms was merely the sauce piquante to the

dainty dish.

Colonna knew his fellow Italian well; he could, had he liked, point to the pestiferous refuse heap where this gaudy butterfly was evolved. And when Colonna allowed Carmen's claims to regal blood to pass, she was in a way grateful. Rich by virtue of her marriage, Carmen was nevertheless always short of money. The Serpent of Old Nile was no more fascinating than she, her smile was one of melting tenderness, what time she was heartless and cruel as the grave. To Colonna this fascinating enigma was as an open book.

He sat opposite to Carmen Clay in the daintiest corner of, perhaps, the daintiest drawing-room in all Kensington. Colonna was ever a welcome guest there. The smiling and easy contempt with which he treated his hostess charmed her.

"Well," she said, "I suppose you want something, or you would not be here."

"Absolutely correct," Colonna responded, candidly. "I want a great deal."

"Ah! You are aware that I never do anything for nothing?"

"Dear madam," Colonna murmured, "you pain me. Could it be possible for anyone to know you and pass by as if you were on ordinary woman? To study a character like yours is a living and a constant joy to me."

Carmen's red lips displayed two rows of seed pearls in a caressing smile. A subtle perfume filled the air. The dainty curves of that perfect figure were covered by a foam of lace and a ripple of Liberty inspiration. Cooler heads than Colonna's might have been turned by that picture.

"To be perfectly honest," said Carmen, "I am fearfully hard up. The amount?"

"Two thousand pounds is a deal of money," said Colonna, tentatively.

"It is, Colonna; you are going to ask me to do something awful."

"Indeed, I am not. I shall merely give you a lesson to learn and a congenial part to play. I shall pay for all the cost of stage management, and when the performance is over you will get your cheque. Could anything be more simple?"

"Go on. I am absolutely consumed with curiosity."

"All in good time. Do you happen to have met Baron Rosalba?"

"Two or three times lately. The Baron and myself are quite good friends."

"He is a very rich man," Colonna said, drily. "You say he knows how to take care of his wealth. So much the better for my little scheme. Now, as you are doubtless aware, the Baron is a veritable Napoleon of finance. He has a great programme on now which will put millions in his pocket, and may seriously affect the future of Europe—of England especially. Therefore it becomes necessary to frustrate this plan. As to that, I will coach you in due course. To make assurance doubly sure, a paper will be drawn up for the Baron's signature. There will be a concession to X which, if signed, will render his plan futile. When you are up in your part, you will let the Baron know that you have discovered the plot, and boldly demand his signature."

"Which will assuredly be refused," said Carmen.

"The first time, doubtless," Colonna said, coolly. "You will accept this gracefully, and avow your intention of trying again. The next time you will score."

"If any other man had said so I should have laughed in his face."

"That is a very pretty compliment, cara, and none the less so because it is sincere. All the same, I am quite sanguine of success. Your part will reach you to-night, and you will get it up without delay. Then you will copy out the concession in your own hand, and take the first opportunity of asking the Baron to sign it. Within a week of this you are going to send out invitations for a gipsy dance."

"And what may a gipsy dance be?"

"It is going to be a little inspiration of your own. There will be no programmes, no formal supper, and a real gypsy band for music. And there will be no servants. This latter stipulation is important. The guests will be asked from twelve to four, and once they have arrived all doors will be locked to the close. Society is only a big child with a new drum, and society will be charmed. I will take care the thing is properly pushed in the papers. It will cost you nothing."

"That is very nice," Carmen laughed, "but as far as I can see it brings us no nearer to the signature of that paper."

"I am just coming to the crux of the thing," Colonna replied. "Of course, we must lay a trap for Rosalba. What is to happen once the bird is caught you will find mapped out in your own part. Here is the cage."

Colonna drew a small box from his pocket, and from the crimson leather within produced the golden rose. Carmen gave a cry of delight.

"How exquisitely lovely!" she exclaimed. "Where did you pick that up? But I fail to see how that pretty thing can effect Rosalba."

Colonna, by way of reply, look up the rose and pressed the stem. He explained the whole working of the needles to Carmen, to her great delight.

"If you open this corona by touching this tiny stud," he said, "you disclose this dial. It looks like a watch, it has works like a watch, but really the thing is a time-clock. If the clock is wound up, and set, say, at twelve, precisely at the hour those curved needles shoot out. They are very long, you see, and if they gripped your arm, for instance, they would retain a hold until pressure was brought to bear upon the stem. Suppose someone steals the thing, and pockets it when set, it would be a case of the Spartan boy and the fox, especially if the man who stole it was so carefully watched that he could not dispose of it."

"Your meaning is not quite plain yet," said Carmen.

"That I now arrive at," Colonna replied. "Rosalba has quite a mania for rare and costly curios, and how rare this is you don't know. I am going to tell him that this is yours, and pique his curiosity. No, I am not going to leave it here now, but it will be placed on a table in your inner drawing-room on the night of the dance. There are two doors to that room, are there not? Good. At a certain time in the evening Rosalba will steal that rose, and you and I will see it done."

"Colonna, you must be raving!"

>"Colonna, you must be raving!"

"Never more sane in my life," Colonna smiled, for the marvels of the book with the silver clasps were uppermost in his mind. "As sure as you are seated there, Rosalba will steal that treasure within five minutes of one o'clock on the night of the dance. The dial will be set for a little after one. Rosalba will place it in his pocket, and then he will discover that we have seen the theft. Scores of honest collectors would do the same thing."

"How slow you are!" Carmen said. "And then?"

Colonna smiled quietly.

"You will find all the rest, or so much, at any rate, as I mean you to know, written in your part, which you will follow up to the minutest detail. No, I am not going to tell you any more at present."

"I could strike you! At any rate, you will leave the rose here?"

"No, I cannot even do that, Carmen," Colonna replied. "There are certain reasons why I could not do so. Surely you are satisfied."

"One has to be pliant with you," Carmen replied, almost tearfully; "and the money you mentioned will come opportunely."

Then Colonna rose and took his leave.

Rosalba's inscrutable face looked across the circular dining- table to Colonna. The former had dined with the doctor—a repast absolutely simple, though the wines were rare and curious, quite cameos in their way, as Rosalba remarked.

"I owe you a debt of gratitude for asking me to dine here tonight," said the latter. "Your English Sundays are terribly depressing, but to-night I have dined poetically, and your art treasures are a dream."

"And we finish up the day at Carmen's gypsy dance," Colonna smiled. "Come, all English Sundays are not absolutely hopeless. And, by the way, there is one thing at Carmen's you must not omit to see. You will remember, of course, that one of the Popes sent Charles V. of Spain a 'Holy Rose.' You will also recollect that Charles, to get Francis I. of France out of his way, hit upon the happy expedient of copying the rose, and forwarding the poisoned copy to Francis as the original—thereby gaining the latters friendship and destroying him at the same time. The affair was discovered, and the plot failed in consequence."

"It did," said Rosalba, "and that famous forgery has never been heard of since."

"You mean not till a few days ago," Colonna said, drily.

For once in a way Rosalba displayed signs of excitement. "You don't mean to say the thing is extant!" he exclaimed.

"Certainly I do," Colonna replied. "I have had it in my hands; indeed, at the present time it is in Carmen's drawing-room. But you will see it for yourself presently. I thought you would be interested in my discovery. Come, one more glass of this liqueur, and we will smoke a cigarette and depart. Allow me?"

Colonna took up a clean glass and held it up to the light. There appeared to be on the crystal a fleck of dust that annoyed him, for he took a clean serviette from the sideboard, unfolded it, and then polished the glass afresh. Just for an instant the glass took on a metallic blue, which as instantly faded. He poured out the rare liqueur, and passed it to Rosalba.

"There are only four flasks of that in Europe," he said. Rosalba praised the liquid with the tempered moderation of a connoisseur. As he sipped the last drop Colonna, with a faint smile flecking his lips, glanced at the clock. Its silver chime struck twelve.

The host pushed the silver cigarette box across the table. "It is time for us to go," he said.

Rosalba, was nothing loth. There was a certain suggestion of uneasiness in his manner which Colonna did not fail to notice.

"Do you know," the financier said, presently, "that I am conscious of a strange impulse to do something extravagant? Perhaps my nerves are a trifle out of order. And yet I am quite light and buoyant. I had half a mind just now to pick your pocket of your watch—a practical joke, you understand."

"In fact, you have reverted for the moment to the elementary predatory stage of the born financier," Colonna suggested drily. "But here we are."

By this time most of Carmen's guests had assembled. The function promised to be a brilliant one, and the very cream of the 'smart' division had gathered there, attracted by the novelty of the proceeding. Already dancing was in full swing, and as Colonna and his companion drove up the last carriage was depositing its burden. Carmen was quite free to receive the new comers.

She was looking specially alluring in some clinging drapery with a foam of lace over. Apparently her warmest smile was for Rosalba.

"Positively, you are the last to arrive," she said. "I have given orders for all the doors to be locked. There is no escape till four in the morning. Baron, am I to take your visit here as a good omen?"

"You mean that I shall sign a certain document?" Rosalba asked.

"Yes, you might have changed your mind, perhaps."

"My dear madame, I never change my mind in business matters. If you were a man, you will see the impossibility of your request."

Colonna appeared to be slightly puzzled. In a light and graceful way he conveyed his jealousy of the understanding between Carmen and Rosalba, and suggested that he might be favored with a share in the mystery.

"No, no," Carmen smiled brilliantly. "This is between the Baron and myself. And I do not despair yet of getting my own way."

Colonna moved away with a suggestion that his presence was de trop. He passed into the smaller drawing-room, where he took the 'Holy Rose' replica from his pocket, and placed it conspicuously on the table. That Rosalba would be certain to mention the thing, and ask to see it, he knew. Therefore, when the Baron came in accompanied by Carmen he felt no surprise.

"Colonna is here," said the former. "Now, may I beg of you to let me see this unique treasure?"

Carmen shrugged her ivory shoulders carelessly.

"That golden rose you gave me," she explained. "The Baron is most anxious to examine it. Dr. Colonna will act as cicerone here, because my guests claim my attention."

"The thing is yonder," said Colonna. "Examine it for yourself." Rosalba took up the curio most reverently. He appeared to be engrossed in its examination.

Colonna followed Carmen from the room.

"One word with you," he said. "You are playing your part uncommonly well. I feel certain that everything is absolutely safe in your hands. But one thing keep uppermost in your mind. Do not fail to enter this room by this door precisely on the stroke of one. I have no more to say."

Carmen nodded with a meaning glance, and passed on. Colonna returned to the room where Rosalba stood absolutely engrossed with the golden rose. So enraptured was he that Colonna spoke twice without eliciting a reply.

"You do not doubt its genuineness?" Colonna asked.

"Not for a moment," Rosalba replied. "With a strong glass I can see the secret mark of the famous, or rather infamous, artist upon it. There is no question that our charming hostess has here a treasure worth anything in reason. I made her an offer just now that would have tempted most people, but she refused, or at least she made such conditions as rendered a sale impossible."

Colonna asked no questions, because he knew perfectly well what those conditions were. It was all part of the programme. The main condition was the signing by Rosalba of the concession which would render his gigantic scheme futile.

"I have the first refusal," he said. "There is another peculiarity about the thing which you will appreciate more fully presently. Come and show yourself, there are many people here who are asking for you."

Rosalba dragged himself away with some little difficulty. He seemed absent and strange in his manner, and the inner drawing- room seemed to draw him like a magnet.

Colonna watched everything narrowly from the other side of the room. A gilt clock pointed to a few minutes to one when Colonna missed Rosalba.

The time had come to act. Colonna crept along in the direction of the inner drawing room, pushing aside the portière just as a silver chime struck one. At the same instant Carmen entered from the other door.

By the table on which lay the Golden Rose stood Rosalba. A trembling hand raised the treasure, and the next instant it lay snug in the financier's breast pocket. Then he became conscious of being watched from either side. Only for a fraction of a second did Rosalba betray any signs of confusion. Men of his mark are beyond weaknesses of that ordinary mundane kind. The Baron was going to brazen it out.

He became conscious of being watched from either side.

"Ah," he said gaily, "madame, you are suspicions. I came to have another look at that treasure of yours, and I find it has disappeared."

"Then somebody has stolen it," Carmen replied. "A poor, practical joke, perhaps. Still, as all the doors are locked, and nobody can depart without my good will and pleasure, I feel perfectly safe."

Rosalba said nothing for a moment. The lips were pressed firmly together, his face was white, though not with fear. For a second, perhaps, he bent almost double, and a great bead of perspiration rolled down his forehead.

As he straightened himself again a sharp cry of pain escaped him. With his left hand clasped to his side, he shivered with the torture he was enduring.

A sharp cry of pain escaped him.

"You are ill," Colonna said with solicitude. "I will give you brandy."

The doctor passed out hurriedly. Apparently the cordial in question had quite escaped his mind, for a minute later he mingled with the gay crowd of guests there as if he had nothing engrossing on his mind.

Meanwhile Carmen and Rosalba stood facing each other. The infernal little instrument in the Baron's pocket had done its work. He had stolen the treasure precisely in the way and at the time Colonna had prophesied, and he knew perfectly well that Carmen was aware of the hiding place of the missing article.

He would brazen it out yet, he told himself. Some diabolical juggling had been practised upon him—he was the victim of a plot. Meanwhile the thing in his pocket seemed to be eating into his very vitals. If Carmen would only leave him alone for a moment that he could restore it to its place.

He plunged his hand furtively into his pocket, but by some means unknown to him the rose had got entangled there. Nothing short of cutting away the lining would be sufficient. Would that woman by his side never go!

"You are ill?" Carmen asked.

"I—I shall be better presently," Rosalba gasped. "A sudden spasm. I am not used to them. If I am left alone for a time."

But Carmen declined to move.

"I could not think of such a thing," she declared. "Come with me, and I will find you a cordial. Anyone can see you are suffering agonies."

With a smothered curse upon his lips, Rosalba complied. His face was white and set, but no further groan of pain escaped him. With the sweetest expression of solicitude upon her face, Carmen administered to his requirements. Another guest claimed her attention for a moment, and Rosalba grasped the opportunity.

He threaded his way dexterously through the dancers and made for the hall. Beyond him lay the front door and safety. Another minute and he would be free from that accursed thing. He turned the handle savagely. The door was locked. A languid footman who was standing there respectfully declined to open the portal.

"But I am ill, dying, man!" Rosalba said, hoarsely.

"I have not the key, sir," was the reply. "My mistress——"

Rosalba turned away with a groan. Once more he tugged savagely at the accursed thing in his pocket, only to cause himself still more exquisite pain. It seemed to have eaten into his very flesh. In a vague kind of way Rosalba returned to the drawing-room to be pounced upon by Carmen at once. He suffered himself to be led into the inner drawing-room, where he sat down.

"Baron!" Carmen exclaimed, "you have only yourself to thank for this."

"Why?" Rosalba asked, the combative instinct not yet crushed.

"Because you are a thief," said Carmen; "because you stole my golden rose. To deny it is futile, for both Dr. Colonna and myself saw you. The thing is in your breast pocket at the present moment. You little dreamt of the mechanism contained therein when you elected to play the felon in my house. You can no more get rid of that thing without assistance than you can fly. Am I to denounce you to my guests as a vulgar pilferer who comes here——"

"Enough," Rosalba groaned; "I am not blind; like a fool I have stepped into the trap, and like a fool I must pay the penalty. Your price?"

"Your signature to the concession I have shown you."

"Which has been dictated to you by a master mind. To do such a thing would be to place a rapier in the hands of my most dangerous foe. I refuse."

Carmen's eyes flashed.

"Very well," she said. "Let us see what powers of endurance you possess. Can you put up with your present pain for nearly three hours? Even then at the end your crime shall be exposed."

Rosalba fumed with futile fury. Even then his strength was nearly spent. It was just possible to sign that paper and circumvent Carmen after all.

"I am afraid you have the whip hand of me," he said, after a long pause. "The paper!"

From a drawer Carmen produced the document in question. She placed it, together with an inked pen, in Rosalba's hand. He dashed his signature at the foot.

"That is well," said Carmen. "And now I will go and fetch the wherewithal to free you from your pain. I will be no longer than I can help."

So saying, Carmen darted from the room. Immediately outside Colonna was listlessly lounging. With a smile of triumph Carmen placed the paper in his hands.

"Victory," she whispered. "What am I to do now?"

"Carry out the rest of the programme," Colonna replied. "Offer to try and rid Rosalba of his ingenious little Frankenstein. Place your hand in his pocket carefully, and press the stud on the stem of the rose. It is very simple."

With a bright nod of appreciation Carmen returned to the drawing room. With some little hesitation she carried out Colonna's instructions. A touch of her strong fingers, a little click and the golden rose, apparently simple and harmless, lay in her hand.

"There," she cried. "What surgeon could have done that better?"

Something like a sob broke from Rosalba.

"I breathe again," he said, hoarsely. "May I look at that instrument of the devil? No, keep it, never do I handle the thing again. And now, madame, having been successful in your vile scheme, perhaps you will permit me to depart."

"With pleasure," Carmen replied, with the most brilliant of smiles. "I trust that you will bear no malice. I have merely got the better of you in a little financial transaction."

"I bear no malice," Rosalba said, grimly, "but if ever you or Colonna come under my thumb I'll crush you both with the greatest possible pleasure."

After the Baron had at length departed, Colonna listened with an amused smile to Carmen's graphic description. Then in a carefully careless kind of way he placed the golden rose in a box which he concealed in his pocket.

"Surely you will give me that!" Carmen suggested.

"No," was the firm reply. "There are many reasons against it. And I think you are going to be well paid for your work. Let me compliment you upon it, Carmen. I will see you again some time in the morning."

COLONNA, ruminating over his matutinal cigarette, was

somewhat rudely interrupted by a visitor. Sir William Wallace

burst into the room, full of intense excitement.

"Have you seen a morning paper?" he demanded.

"No," Colonna replied. "Is there anything startling?"

"Startling! I should say so indeed, Rosalba has committed suicide. He was found dead in his room early this morning with a bullet in his brains. I hope, Colonna, I hope sincerely that your little scheme——"

"He was found dead in his room."

"You can make your mind quite easy on that point," Colonna said, calmly. "My scheme was quite successful, the concession was duly signed, and if Rosalba committed suicide, beyond question he did it out of mortification. And as long as we have the concession, his representatives, or accomplices, are powerless."

"I must own," Wallace answered, "that you have taken a weight off my mind. Would you mind explaining the modus operandi?"

"Delightfully simple. Rosalba was detected in an act of theft in a private house, and he signed the concession as the price of silence. As you are perfectly aware, there is a certain form of hysteria which is part and parcel of the malady called kleptomania. In my formulae I have a virus which, administered to a person, causes an irresistible desire to pilfer. This I administered to Rosalba, designing the poison to produce an effect at a certain time."

"But how could you graduate it to a moment?"

"By personal experiments," Colonna said, calmly. "I tried a series of doses on myself, taking care to remain here till the effect had passed. In Rosalba's case the thing acted like clockwork. As to the rest, fate placed in my hands a little instrument that rendered success absolutely certain. When you told me Rosalba had committed suicide I was as surprised as yourself."

For a long time after his visitor had departed, Colonna sat silent and thoughtful in his chair. Then at length he rose.

"There was no occasion to tell Wallace all the truth," he said. "And it was best after all to remove Rosalba. So the formula was right after all, and those poisoned needles in the rose produced the desire for self-destruction, which Lucrezia Borgia claimed for it. To cause your enemy to die by his own hand seems an immense saving of risk and labor."