RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

THE lecturer held the vast audience in the hollow of his hand. They seemed to sway to his every movement, those men of science, learned and polyglot, gathered from all parts of the world to hear Dr. Victor Colonna.

For two hours had the doctor held his hearers spellbound. A slight, clean-shaven man, with eager, boyish face, and sanguine, mobile lips, he looked like a mere youth in the presence of those grey-beards. Yet the hair was grey upon the temples, there were innumerable fine lines under the flashing eyes. Not once in a generation is it given to a young man to keep the savants of the world at his feet, but Colonna was doing this, and more.

A great volume with two silver clasps lay on the lecturing table before him. The world boasted no more wonderful or unique volume. For the precious tome at one time had belonged to Lucrezia Borgia, and in it were recorded the recipes and effects of those poisons which had rendered infamous the memory of the Jezebel of her time.

One experiment had followed another in rapid succession. Men who had made toxicology a study from their youth up, smiled at their own ignorance. This volume had come down to the last of the Borgias, the only one of the family for generations who had the wit and ability to grasp its tremendous power and importance.

Then Dr. Colonna closed the volume with a bang. He seemed to heighten and expand with the force of his peroration.

Then Dr. Colonna closed the volume with a bang.

"For the present," he said, "I have finished. For generations that volume has been handed down in my family as an heirloom, a curiosity, and, I am the first of my race who has dared to study it. Impelled by my devotion to science, I have sought the key. It is for you to judge as to whether or not I have found it."

A prolonged burst of cheering followed this statement.

"You are kind enough to say I have." Colonna proceeded. "I might have kept these remarkable discoveries to myself—indeed, it may have been better for the world in general had I done so—but the mistress who sways us so imperatively to her will bade me speak. And what have I shown you to-night? A score or more of poisons, which were undreamt of yesterday—poisons strange and mysterious in their action; mandragora which strike down and leave no trace behind. Need I destroy a nation I can do so. Have I an enemy I desire to remove? I can sweep him away without the fear of detection. I can administer a bane that lies harmless in the system until the flesh comes in contact with another irritant months after, and the victim dies.

"So much for our boasted knowledge; so much for the 'darkness' of the Middle Ages. And I am going further still. I say some of the crimes of Brinvilliers were justifiable—I say, that under certain circumstances, some crimes are justifiable still. Would I use my knowledge to sweep a villain from my path? No, for I have too much confidence in myself. Would I use the precious knowledge I possess to save the poor and suffering, to free Europe from the blister and ban of Turkish rule, for example? I am not prepared to say."

As Colonna concluded, a great shout went up from the assembled crowd. They surged out of the building to the back of the hall, prepared to give the lecturer a hearty cheer, but already Colonna had departed. It was barely eleven when he reached his chambers. Those rooms in Bennett Street were plainly furnished, and betrayed nothing of a scientific nature, for Colonna had his workshops elsewhere. An elderly servant came up bearing a tray, on which was a bowl of bread and milk.

"We are going to bed, sir," she said. "Do you require anything more?"

"No," Colonna replied, "only do not fasten the front door. I may take a fancy to go out, or a friend may come in yet. I will see to it."

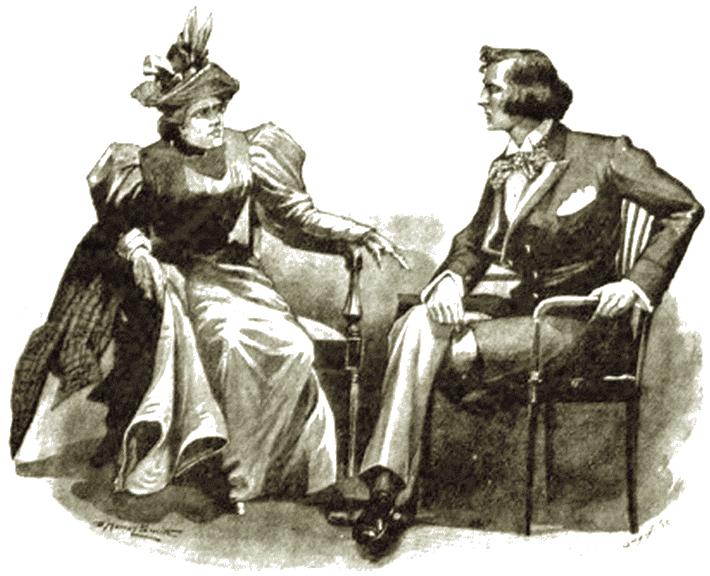

The simple supper dispatched, Colonna flung himself into a chair and proceeded to light a cigarette. Ere this was finished, the ringing of the front-door bell aroused him from his reverie. Colonna slipped down quietly, and opened the door. The tall figure of a woman, cloaked and veiled, stood there.

"You are Dr. Colonna," the lady said. "Can I see you at once and alone?"

There was a ring of power and command in the fluent voice. With no expressed feeling of surprise, Colonna signified that the speaker could precede him. She did so with a firm and determined step. Colonna closed his sitting-room door, and turned up the gas fully.

Standing in the full glare, the visitor swept away her cloak and hood with a superb gesture. She was past the first bloom of youth, dark, and wonderfully beautiful. Her air was queenly and commanding. With very little effort of imagination, Colonna could picture her with an imperial diadem on those ivory brows. Nathless, there was a wild, despairing look in the fine eyes, the full red lips drooped.

"I am Ellen Longwater, wife of the Master of Longwater," she said abruptly. Colonna bowed. The statement sounded wild and bizarre enough for comic opera, but the Doctor evinced no surprise.

"I have heard of you," he said. "What can I do for you?"

"Much," came the passionate reply. "Two hours ago, I was plunged in despair. To distract my thoughts, I went to hear you lecture. Need I tell you how completely you carried me away? And in your concluding remarks I saw a gleam of hope. You said you would not be prepared to hesitate where a people rightly struggling to be free were concerned. We are the people struggling to be free. A hair will turn the balance either way. Remove one man, and the happiness of a great family is assured. Will you do this for me?"

"You want me to use my knowledge to murder someone?"

"I will be perfectly frank with you. I do."

As if this were the most natural request in the world, Ellen Longwater dropped into a chair, and folded her hands. Nobody could have guessed how painfully every nerve of her body was thrilling.

"Truly a remarkable request," Colonna replied, with a remarkable allurement. "But why should I place myself so unreservedly in your power I have only to hold up my little finger and the man is obliterated. And then what is to prevent you using your hold to ask for more?"

"Oh, I have thought of all that," the listener responded rapidly. "I am prepared to sign a document which you will draw up, fully implicating myself. You may regard me as a madwoman—to all practical purposes I am. It makes me mad to see our ancient family, our prestige and money and influence in the throttling grasp of a scoundrel! Unless something is done, Count Henri Felspar will destroy us."

"Oh, then Felspar is to be my victim!"

"Yes, yes. You speak as if you knew him."

"By repute I know him very well indeed," Colonna replied. "Felspar is a man of science like myself. He enjoys a high reputation."

"But only as a savant. Felspar is one of the greatest scoundrels who ever lived. He is well-born, I grant you, especially on his mother's side. More Italian than anything else, there is a berserk vein in his nature that makes him utterly reckless where his aims and passions are concerned. He seems to be connected with any number of noble families; at any rate he is with ours."

Colonna bowed. The blood of the Longwaters was of the purest. The Master of that Ilk would not have exchanged his title and his Scottish roods for an Imperial diadem, and a province to boot. The Bohuns and the Burleighs were parvenus compared to them. More than once had the Longwater sang azul mingled with the purple stream of Stuart and Tudor.

"Your son is Master, I believe," Colonna suggested.

"My step-son," the lady corrected. "Hector Longwater is four- and-twenty, a noble, handsome fellow whom I love as deeply as if he were my own flesh and blood. As you may be aware, he is engaged to Princess Esmé of Valdemir."

Colonna smiled slightly.

"We are evidently coming to the point," he said. "I have had the pleasure of seeing the Princess. She is wonderfully beautiful, and if report speaks truly, as intellectual as she is lovely. Your step-son is fortunate."

"So it would seem," Ellen Longwater replied. "The Longwaters were rich before the late master married myself and my fortune. I was a Rosenthal, you know. Ultimately all my money will go to Hector, for I have no children, and I shall never marry again."

"The Valdemir family are poor?"

"Poor as they are distinguished, which is saying a great deal. Some day Princess Esmé will be ruler of Valdemir, her son and Hector's will govern the little kingdom, and with our fortune who knows what may happen. Leading statesmen, in two countries at least, have heard of the projected union with the liveliest satisfaction. For diplomatic reasons it is necessary to maintain Valdemir properly. This marriage would assure such a state of things. When I add that the young people love one another devotedly, you have the idyll perfect."

"The course of true love runs smoothly, then."

"It runs on oiled wheels of gold. But there is a fearful barrier."

"Taking the form of Felspar, I presume."

Ellen Longwater's dark eyes flashed. Her whole manner changed.

"You have guessed it," she said fervently. "The wedding day is fixed; the Princess and her friends are in England now. On Friday week the wedding is to take place in the private chapel at Longwater Royal—our Perthshire place, you understand. Then suddenly there comes a bolt from the blue in the shape of Felspar. Romantic as it may seem, Felspar is deeply enamoured of Esmé. He met her a year ago somewhere abroad, and she seems to have fascinated him. There is little doubt, I am sorry to say, that Esmé encouraged the man's advances. He is very handsome for his years, wonderfully clever and fascinating, and the girl was flattered by his attentions. Even then the proposed marriage was practically arranged. When Felspar heard what had happened he was almost beside himself. From time to time he has hinted that he could wreck us all if he chose, and, unfortunately, he is in a position to do so. Oh, the diabolical scoundrel!"

"Felspar is all you say," Colonna replied quietly. "By a strange coincidence I happen to know one or two things about him which I should not care to confide to you. A clever man, a great chemist, he has most extravagant tastes, and does not hesitate as to the means of gratifying them. One clear case at least of blackmail—"

"He is attempting to blackmail me now."

"He is attempting to blackmail me now."

"Ah," cried Colonna, "I thought we should come to that. A large amount?"

"Half a million of money, and he will take no less."

"Not if he has demanded that sum," Colonna murmured. "The question is—is he in a position to force your hand? If I am to take this matter up, there must be no half confidences."

"I came prepared to tell you everything," Ellen Longwater cried. "I told you that Felspar was connected with my late husband; indeed, they were great friends at one time. In those days the Master was deeply impressed with certain philosophical, social ideas. Unfortunately, he had nobody to control him then, and he plunged into the act of folly which now threatens us all with ruin. He married a beautiful daughter of the soil; she left him in three months and fled to America. She could not stand the new life; it frightened her, and crushed her down. When news came of her death, the Master married again—Hector's mother this time. And now it turns out that the first wife actually died on the very day Hector was born. This being so, Hector is no more Master of Longwater than yourself. And Felspar can prove this by documentary evidence. Need I say more?"

"You need not," Colonna said gravely, "knowing the man. The sum demanded is the price of Felspar's silence. He has waited till the psychological moment."

"Has he not! But Felspar is not to be trusted. He would take the money, and then betray the secret after—indeed, I know he intends to do so. He has invited himself to the wedding, and at the breakfast he fully intends to explode the mine. A young protégé of mine, Felspar's secretary, has gleaned something of this, and he has communicated with me. Of course, he has no idea of the real truth. Dr. Colonna, you see the desperate condition of affairs. Are we to go down ruined and disgraced, or is this human tiger to be slain? Do not answer lightly."

Colonna pondered for some time in silence. Then he looked up with a slight smile.

"I will fire the bullet," he said. "I will rid the world of this reptile. If ever the end justified the means it does so here. But you must sign that paper."

"I will sign anything you like to ask for."

The preparation of the document in question took some time, but finally it was accomplished. Then Ellen Longwater dashed her signature at the foot. Her eyes gleamed with the fire of a great resolution.

"What more?" she demanded.

"In the first place you will do exactly as I tell you. Have no fear of the consequences, for assuredly I shall not fail. To- night you will write to Felspar telling him that you utterly repudiate his offer, and bidding him do his worst. I presume you would have no objection to my being one of the wedding guests?"

"Your presence would be the greatest comfort and support to me."

"Then I will come. I can see my way to a dramatic curtain. I see your nerves are of the stoutest, and you will need them."

Ellen Longwater smiled somewhat scornfully.

"You may make your mind easy on that score," she said.

"Good," said Colonna. "Now tell me something of Felspar's habits. Where, for instance, is he staying at the present time?"

"That can easily be answered," said the fair conspirator eagerly. "So distinguished a savant as Count Felspar seldom has meals in the temporary quarters he occupies. There is a deal of the pride that apes humility about the Count—when he is short of money. He affects quite humble lodgings for himself, with a room at the top of the house for his secretary."

"Study and dining-room all in one, I presume?"

"Quite so. Can I do anything further?"

"For the present, nothing," Colonna replied. "The rest must be all left in my hands. Let this secretary, Antonio Ferra, know when I am coming. I can easily allay any of his suspicions by my zeal for yourself."

Ellen Longwater rose from her seat, and extended her hand. "How can I thank you sufficiently?" she said in trembling tones. "It was an act of madness to come here, but I was beside myself, and if failure should crown the attempt you are about to make—"

"Have no fear," Colonna said curtly, "I never fail. Let me hear when to call upon Ferra, and the hour, and as for the rest, go about your usual vocations as if nothing had happened. Good- night, and sleep in peace."

FOR two days nothing came to Colonna. Then the afternoon's

post brought him a card, on which were inscribed simply the

words:

To-night at eight. 17, Water Street, W.

Colonna dropped the card carefully into the heart of the fire. A little time later he opened an iron safe in the wall, and took from it a tiny blue wafer, which he placed in a pill box, together with a minute phial containing some grains of grey powder. Apparently this completed the simple preparation or what might tend to avert a social catastrophe.

Then quietly and reflectively he idled to Water Street. Here he discarded the cigarette he was smoking, and knocked. Presently the door was opened by a young man with a dark face and a Van Dyck beard.

"I am seeking Signor Antonio Ferra," Colonna said tentatively.

The man in the doorway smiled. "I am he whom you seek," he said, "and as a friend, you are welcome. Will you please to come in, Doctor Colonna?"

THE Count's sitting-room in Water Street was exceedingly simple, the furniture being of the usual lodging- house type. Between the windows stood a writing desk; opposite the door was a flimsy-looking chiffonier.

"I am quite alone till to-morrow," Ferra volunteered. "My distinguished master has gone to Birmingham to fulfil an appointment at a public meeting there."

So the pair chatted on for some time. It was getting late when a messenger arrived with a letter for Ferra. He frowned slightly as he read it. Colonna appeared to take no heed, though he knew perfectly well what the contents of the letter were. The thing had been carefully planned between Ellen Longwater and himself to get Ferra out of the way for a time.

"I am afraid I shall have to leave you for half-an-hour," said the latter. "But I am loth to part with you, Doctor. If you care to remain till I return—"

"With pleasure," Colonna responded. "I should like to finish our argument. And in your absence, I can think out new points."

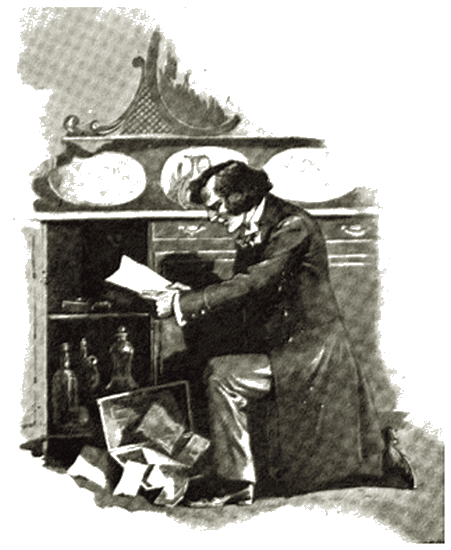

Ferra departed hastily, leaving Colonna apparently buried in thought, deep in a comfortable arm-chair. No sooner was the latter left alone than he sprang to his feet, alert and vigorous. Taking a bunch of keys from his pocket, he tried several on the flimsy sideboard, until one at length turned in the lock. There was little inside to attract Colonna's attention beyond some bottles and a few papers of no particular interest. But in one corner was a flat desk which seemed to arouse his curiosity.

"The papers I want are there," he muttered. "Felspar is a man of original ideas. Another person would have hidden them in a safe: no spy would waste his time on that wooden desk. As I am not a mere spy, I shall."

To open desk, was a more difficult matter than the chiffonier. A few papers were there. With a flashing gleam in his eyes Colonna pounced upon the very thing he required. Felspar had made no idle boast. Here was the letter which meant Hector Longwater's social destruction. And here, also, was the statement Felspar evidently intended to hurl at the wedding guests on that fateful Friday.

Colonna pounced upon the very thing he required.

Colonna perused the closely written pages rapidly. It was exactly as Ellen Longwater feared. The discourse was artfully arranged to create a profound sensation. Without warning the blow would fall. First came some well-chosen, happy phrases appropriate to the occasion, and then——

But Colonna had neither time nor inclination to go into this. "The stars in their courses fight upon our side," he murmured. "Felspar will read no page after his graceful compliments to the happy pair. When he has finished that, he will have to turn over. I will take the liberty of blotting out the few damning words that remain ere a turn of leaf is required. As this document has evidently been revised, I shall be perfectly safe."

Taking up a pen, Colonna scored out a dozen lines. Then, turning to the blue wafer, he crumbled it, and resuming his gloves, rubbed it over the opened manuscript vigorously. Apparently satisfied, the speech was replaced in the desk, and the remains of the wafer were carefully dropped into the heart of the fire, followed by the gloves Colonna was wearing.

"Longwater is saved," Colonna went on. "It was a happy thought of mine to look for the documentary evidence in that desk. But luck is ever for the audacious. How Shakespeare would have revelled in the dramatic scene which is to come!"

When Ferra returned at length, he found Colonna still half buried in the cavernous arm-chair, and apparently lost in reflection. Then they plunged once more into an animated debate, which lasted far into the night. Finally, Colonna rose to go.

"You ought to meet the Count," said Ferra.

"No doubt we shall soon," Colonna replied, somewhat drily. "In any case, I propose to do myself the pleasure of meeting him in Scotland on Friday."

IT was not till the Thursday night that Colonna saw Ellen

Longwater again. A brilliant company had gathered at Longwater

Royal. Dinner was well advanced before Colonna entered the great

banqueting hall. Felspar had not yet arrived. Once the function

was over, Ellen Longwater approached Colonna.

"I have heard nothing," she said. "Do'nt tell me you have failed!"

"Madame, I do not fail," was the cold reply. "I found your information correct in every detail."

"But the time, the time is so short. A few hours more, and Count Felspar's denunciation goes out to the whole world to hear."

"I know it. I could have set the clock back had I liked."

"Then why in the name of all one holds dear did you not do so?"

"Because I have a better plan," said Colonna. "And I have purposely refrained from doing so. You defied Felspar as I asked?"

"Your instructions were carried out to the letter. He replied, that I should regret my decision all my lifetime. He told me plainly when and how he means to bring about the catastrophe. He will propose the health of the bride, and—but I dare not allow my mind to dwell upon it."

"He shall propose the health of the bride," Colonna said grimly. "He shall pay a glowing tribute to groom and maiden. And there he shall cease. I am ready for him, fatally ready. Do you know I have had that letter in my hand?"

"In your hand! And you did not destroy it?"

"For what purpose? The loss would only have aroused Felspar's suspicions. And he could have easily procured fresh evidence. It is the man we want to destroy, and so destroy, that, at the moment of dissolution, those proofs fall into our hands. Now listen to me, and see that you follow me implicitly. Felspar is to be allowed to start his speech. You are to be on one side of him, and myself, if it can be so arranged, on the other. Then you are to procure for me, and leave in my room, one of the bottles of champagne which is intended for consumption to-morrow. The bottle will be returned to you, and you are to see that it is placed so that you and Felspar partake of it. You must have no fear—it won't hurt us. That is all you have to do. And, when to-morrow you hear the word 'eleven' from my lips, watch me carefully."

"You have no more to say!"

"Positively nothing. And, now I am going to felicitate the bride."

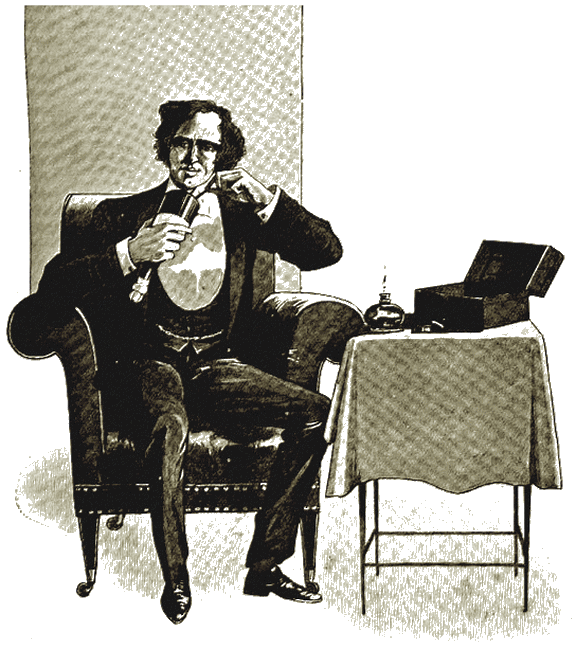

All the same, Colonna had not quite finished. When he retired to his room that night he found the bottle of champagne ready for him. From a dispatch box he took a tiny drill with a diamond point, and another of the blue wafers similar to the one used upon the manuscript pages of Felspar's wedding speech, and subsequent remarkable revelation.

In the bottom of the bottle Colonna drilled a minute hole and pressed a portion of the wafer into the receptacle. A dot of sealing wax laid on this completed these apparently simple preparations.

A dot of sealing wax completed these apparently simple preparations.

"The rest lies with Ellen Longwater," Colonna murmured. "If she carries out her instructions faithfully, Felspar is not likely to trouble her again."

With which remark Colonna turned into bed, and in a few minutes had fallen into a peaceful and untroubled sleep.

A BRILLIANT and distinguished crowd had gathered in Longwater Royal banqueting hall to pay a tribute to the popularity of the happy pair. There were practically no ordinary folk there beyond a pressman or two, who had had a hint to be present, but, none the less, the assembly was a social and representative one.

Count Felspar, a noble and handsome figure in immaculate dress, was quite a centre of attraction. Some there were who declared that his mouth was shifty, and his eyes a little too close together, but what great man is there who has no enemies?

The magnificent pageant proceeded. With his own hands Felspar filled his glass from the bottle placed somewhat prominently before him, and gulped the flowing nectar down.

Colonna sat next to Felspar, taking in everything with his glittering eyes. He saw the Count place the crystal chalice of rare wine to his lips, and a smile like summer lightning played about his face.

For some time the somewhat prosy orations went on, but at length a subdued thrill of expectancy passed through the assembly. A hush fell upon the guests as they looked eagerly to the side of the table where Felspar sat. He was to propose the toast of the day, and the Count had a pretty gift of public speaking.

Up to now Colonna had not spoken one word to Ellen. Now he laid his hand, as if by accident, on hers behind Felspar's chair, and then he flashed one glance into her eyes, after which he studiously refrained from further scrutiny.

He could see the deadly pallor of her features, the twitching of the hands; but Colonna noticed that the daintily moulded chin was firm and hard as marble.

The speech of the day commenced. It contained no brilliant flight of oratory, a thing hardly to be expected in a bridal discourse, but there were plenty of pithy points, delicate fancy, and playful humour. Some of the listeners wondered what those papers were in Felspar's hand. If they had only known—

"The time is at hand," Colonna whispered, "be prepared."

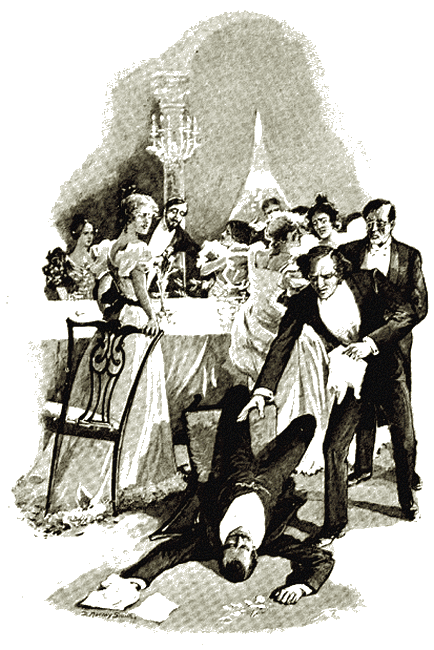

Ellen Longwater bent her head ever so lightly. She was listening with all her soul to the praise—praise conveyed as if flowing spontaneously from the speaker—of the virtues of the happy, happy pair. If Felspar stopped there, if he spoke no more, the cloud that threatened the happiness of a great family was gone for ever. Then Felspar paused as if breathless, a fine dramatic pause.

"That is the picture," he said suavely, "and who shall say it is not a glorious—"

"Eleven," came from Colonna's lips. "Eleven."

Amused and interested, the audience waited. But no further words came. The sound of a long, fluttering sigh echoed through the hall; close to Colonna and his ally was the crash of a falling body.

Colonna was the first to recover himself. With one bound he was by the stricken man, putting all opposition aside.

With one bound he was by the stricken man.

"Fetch a doctor," he cried, "the Count is dying."

Colonna's voice rang loud and clear. In such an ultra- fashionable gathering there was no difficulty in procuring medical aid. Two doctors were quickly on the spot, but one glance was sufficient. The physicians were quite unanimous in their verdict. Sudden failure of the heart's action was the cause of death—there was even no occasion for an inquest.

"Are you satisfied?" Colonna whispered.

Ellen Longwater shuddered from head to foot. "For my family," she murmured, "for Hector. We are saved, and I shall be the most miserable woman on earth to the day of my death. Before you leave you must come and tell me how the vile thing was done."

The speaker turned away, and plunged into the frightened crowd. Colonna followed her with a curious speculation in his eye.

"How like a woman!" he murmured. "Strange creature! Bad as she feels now, she would do the same thing to-morrow. And she will be another woman when I see her this evening."

Colonna was correct as usual. Curiosity had overcome terror for the time at least. "I am dying to know how it was done," said the pallid speaker. Colonna explained fully.

"The point is this," he said. "The poison was taken internally from the drugged bottle of wine. You yourself actually drank that poison, and yet, until the chain is completed, it is quite harmless. The blue wafer charged the wine, the blue wafer was also rubbed on Felspar's discourse. The contact with the hand on the fatal leaf did the deed; the drug within called for the drug without and as the two were brought into contact Felspar died of the shock. Horrible, if you like, and yet beautifully simple. But you need not look so pale—you are not likely to touch the wafer. And, in any case, the internal effects would be dead by morning."

"Wonderful!" Ellen cried. "I marvel you care to tell me this."

Colonna shrugged his shoulders.

"It is nothing," he said, "the simplest of all the tricks of my volume. Ah, how I could astonish you if I liked! And even with this childish toy, detection is absolutely impossible. All the same the Count's death would not have cleared you if I had not been present."

"And why, Dr. Colonna?" Ellen asked.

"Because the written speech would have betrayed you," Colonna replied. "That was why I was first at the Count's side. I crammed those papers in my pocket. There they are. What shall I do with them?"

"Burn them at once," Ellen Longwater said promptly.

The red heart of the fire ate into the winged words. Then as they faded away to dust and ashes, Ellen rose and pointed to the door.

"You have saved our honour," she said, "and from my heart I thank you. And now go, Dr Colonna. It is my one prayer that you and I may never meet each other face to face again."