RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

COUNSEL with the sleek head and large, loose mouth intimated that her Grace had no wish to press the charge; indeed, counsel might assure the Bench in confidence that the Duchess had approached this matter with the deepest pain. She desired to withdraw from the prosecution; she was even willing to take the prisoner into her service again. Of such kindly stuff are duchesses made.

Bench was dubious; Bench was a soured individual, who had been disappointed in a County Court judgeship; and Bench regarded this as a serious matter. Had not his learned friend stated that the stolen necklace was worth £30,000? Certainly such a statement had fallen from the loose mouth. But the inconvenience to her Grace! In fact, her Grace did not see when she could appear to prosecute.

"Case dismissed," said Bench. "Prisoner, you are discharged."

The tall girl with the tiger-lily face gazed helplessly around her. Colonna, who had been a scientific witness in a case just remanded, watched her intently. Whatever the prisoner's vices were, she was no thief. And Ia Ian, as the prisoner was described, looked exceedingly refined and ladylike, even for the maid of a duchess.

"You are discharged," the Bench repeated sharply. "Go away."

The prisoner drew a deep breath, as if to speak; then she seemed to change her mind. In an aimless, dreamy kind of way she drifted out of court like a human derelict floating along the stream of souls. But Colonna, who followed behind, noted how rigidly the hands were clenched. He stepped to the girl's side.

He stepped to the girl's side.

"You are in trouble," he said. "Can I assist you?"

The girl turned a pair of fearless, velvety black eyes upon the speaker. Beneath their liquid beauty, Colonna could read the passionate despair.

"If you can compel a liar to speak the truth, you can," Ia Ian replied.

Her English was perfect enough, clear and mellifluous, and yet suggestive of the bells and pomegranates. There was originality here, as well as beauty, and Colonna was interested.

"I have done stranger things than that," he said. "You may know my name—Colonna."

"Oh, yes. You are the great doctor. They say you can do witchcraft. But you can't make a duchess apologise to a tiring- maid."

"Why should I attempt so grotesque a thing?"

"Because you could be of no assistance to me without. You were in court, and heard the charge against me. Dr. Colonna, do I look like a thief?"

"You look no more like a thief than a—a lady's maid."

"Thank you. And yet there are few people who would believe my story. If you knew my history, you would say it was worthy of publication. And now I am practically penniless, without a home, and I have been proclaimed as a felon."

"Would it be a liberty on my part to ask you to tell me the story?"

"Not at all. There are times when sympathy and advice are worth untold gold. Do you know why I turned in this direction? I was going to throw myself over Waterloo Bridge."

Colonna attempted no pretty platitudes. On the contrary, in the most natural way, he suggested a chat in the comparative solitude of the Temple Gardens.

"I shall not detain you long," said Ia. "You must know that my father was a Scotchman, with a wild, romantic strain in his blood. Change of scene and adventure were absolutely essential to him, and I have often heard him boast that he has been in a score of places where no white man has ever set foot before. In Brazil there are certain forests which have never yet been explored—or so people think. Well, my father has been there, and, what is more, he has lived for ten years with one of the tribes. It was there that he made his great discovery, and it was there that he came into possession of the Varteg necklace, which is the cause of all my trouble."

"You mean you were charged with stealing your own property?" Colonna asked.

"You have guessed it exactly. That wonderful necklace originally came from Italy, but how it found its way amongst the Varteg tribe will probably remain a mystery to the end of time. My father's opinion was that those people were originally Italian refugees, who wandered away behind the belts of forest, which were subsequently rendered impregnable by some mighty earthquake. At any rate, there they are, and there was the necklace. When my father was dying, he gave that necklace into my possession as my fortune. We were far away from any friends, and we had little money. My instructions were to come to England, and take service with some lady of position here, so that when I came to tell my story I should be protected against robbery and suspicion. Furthermore, I was told that the necklace possessed certain hidden qualities, and that it was never to be worn for more than five minutes on the bare flesh. I fancy that in some way the stones were poisoned with some native preparation, the Vartegs being experts in that direction."

"You can hardly tell how you interest me," said Colonna. "Did your father ever tell you the name of this particular poison?"

"Oh, yes," Ia said confidently. "It was called pyrium."

"Amazing!" Colonna cried. "That was one of the most jealously guarded and secret poisons of the Borgias. And those savages you speak of actually possessed the Latin name. Moreover, the drug is well known to me, and its effects are exactly as you shadow. Tell me, did you ever wear that necklace?"

"I have had it on several times, of course. For five minutes it has no effect whatever. Then it seems to gall the skin, to pinch and burn in the most uncomfortable way, after which I always took it off. You will doubtless laugh at what I am going to say, but, after I have done so, I have several times imagined that I could see in red letters my name on my throat."

"Laughter is far enough away from me at the present time," said Colonna. "I have the best of reasons for knowing that every word you say is true. You have opened up a new field of thought and research for me. But I interrupt you."

"There is little more to tell," said Ia. "For twelve months I have been maid to the Duchess of Isleworth, and a week or two ago I decided to show the necklace to my mistress, and ask her advice and assistance. Unfortunately I did so. It so happens that her Grace has a necklace very much like mine, and you can imagine my feelings when I was accused of impudently stealing this. I lost my temper and said things, the upshot of which was that I was given into custody for stealing a diamond necklace. The Duchess produced her empty case, and—but the rest you know. What was the use of my protesting with such a power opposed to me?"

"I see your point," Colonna said thought fully. "Is her Grace short of money?"

"That is really the gist of the whole matter," Ia answered. "Her Grace had certain heavy gambling debts to meet, and she had to pawn her own stones to do so. I can even tell you where they are at the present time. She has a heart of flint and a nerve of steel. A little audacity, and I was powerless. See how she poses as my benefactress still! Dr. Colonna, I am absolutely ruined."

Colonna pondered over the strange story for a time. "I think I can see a way out of the difficulty," he said at length. "Already I have a vague idea of what may be done. But you must place yourself entirely in my hands."

Ia's eyes flashed. A new determination possessed her. "My fortune has gone," she exclaimed. "I have been robbed of that. But it is a small matter by comparison. But bereft of my good name, how am I to live? Restore me that, and you have my lasting gratitude."

"I will restore both your treasures," Colonna said quietly. "But I am afraid that you will find the conditions somewhat hard."

"To gain what you promise, no condition could be too hard."

"Not even the stipulation that you should accept the offer of the Duchess, and resume the post she is keeping open for you?"

Ia made no reply for the moment. Her head was slightly turned from Colonna, but he could see the white cameo of the face cold and rigid.

"It will be hard, indeed," the girl said presently. "Why should I do that?"

"It is absolutely necessary," said Colonna. "Unless I have in that house an ally, who is both bold and fearless, I can do nothing."

Ia nodded. Her teeth were clenched tightly. The colour was returning slowly to her cheeks; the steely glitter of her eyes faded. It was evident that her mind was made up.

"I will do it," she said, "because I feel I can trust you; and unless you have the same feeling, our endeavours will end in failure. Go on."

"Then, to proceed. Directly you enter that house, and resume your position, I want you to be a thief in earnest. The fact of your return will be evidence to the Duchess that she has you utterly crushed, and she will be contemptuously careless. You will have to steal your own necklace——"

"It would be missed at the end of four-and twenty hours."

"Which would be more than sufficient for my purpose," Colonna said drily. "Come, you must know all the Duchess's engagements—you know which is the safest time to borrow your own property."

Ia pondered the matter for a time.

"You can have it on Thursday morning. It will not be required till Friday, when we are giving the reception of the season. If you like, I will bring the necklace to you personally."

"Good," said Colonna. "Here is my card. And whatever you do, don't fail to bring the original case of the necklace with you."

COLONNA'S orders on the Thursday to his housekeeper were terse and pointed. If a lady called, she was to be admitted to him, and after her departure the doctor was in to nobody. This matter being settled, Colonna turned to his cigarette and The Morning Post. He was looking for the name of the Duchess of Isleworth in that exclusive organ, nor had he far to seek, for the lady's name loomed largely on the sheet. Colonna read as follows:

The dinner and reception to be given by the Duchess of Isleworth at Isleworth House to-morrow will be one of the most brilliant functions which wind up the season. Over a thousand invitations have been accepted for the reception.

Colonna smiled as he read. During the last ten days he had not

been idle. The Duchess was one of the most gorgeous butterflies

flitting over the purple parterre of Society, but it would

have puzzled the past masters in Burke and Debrett to say from

whence her Grace had originally arrived. Colonna could have

enlightened the curious as to where the amiable old Duke had

discovered the icy concrete he called his wife. Mixed up with the

story was a murder, to say nothing of a brace of American

divorces, and there were times when the smell of strong liquors

conjured up before her Grace's hard, handsome eyes memories of

the sawdust shanty where her earliest education was

neglected.

The purest chance had pitchforked this information in Colonna's way, and he meant to use it when the time came. He felt absolute confidence in the issue. So long as Ia procured the necklace, success was certain.

Ia came punctual to the appointed moment. Her cheeks were flushed, her eyes sparkled. There was no occasion to ask whether she had failed.

"I have brought it," she said, "and I have not forgotten to place the stones in the case my father gave to me. Will you see it now?"

Colonna waved the proffered treasure aside. He had his own particular reasons for not caring to examine the jewels until he was alone.

"Kindly place it on the sideboard," he suggested. "When would you like to have the thing returned?"

"To make sure, could you manage it by six o'clock to-day?"

"Yes. I shall be out then, but the parcel shall be left for you. I presume that no suspicions have been aroused."

"Not at all," Ia replied. "You know the Duchess, Dr. Colonna? I see your name on the list of reception guests for to-morrow night."

"I certainly intend to be present," Colonna smiled. "But, as to knowing the Duchess personally, I have not that extreme pleasure. I owe my introduction to a friend. I presume your mistress will wear that necklace to morrow?"

"Of course. There need not be any doubt on that point."

"Then you may regard your little matter as settled. Before eight-and-forty hours are over your head you shall have both the necklace and your good name untarnished. And now, I shall be obliged if you will be so good as to leave me. I have much to do between now and the time of your return. But, one thing, be careful. Under no consideration is the Duchess to wear the necklace to-night."

"Oh, she will not!" Ia exclaimed. "Her Grace is going down East after dinner to some lecture there, and she intends to retire early."

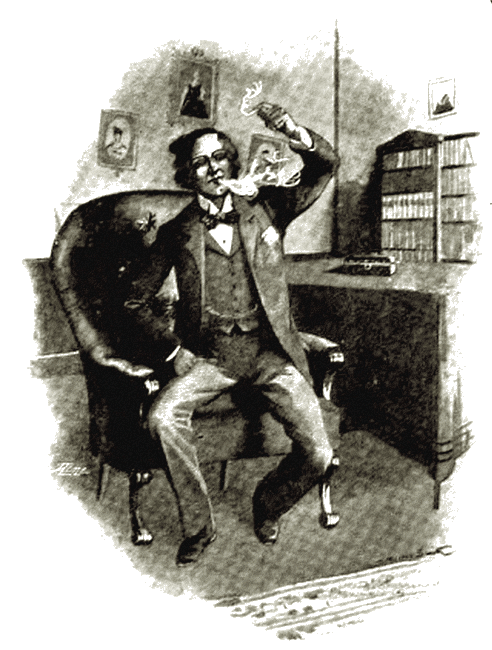

Ia slipped gracefully away. No sooner did Colonna hear the door closed behind her than he tossed his cigarette on the fire and took up the shabby and faded case which contained the brilliant cause of so much trouble. His fingers trembled as he threw back the lid. The inside of this was filled with vellum, yellow with age, and stained in a curious fashion.

He tossed his cigarette on the fire.

"This is stupendous," Colonna murmured. "Beyond question this gaudy treasure has passed through the hands of the Borgias. There is no mistaking the perfumes of the pyrium; nothing else could cause these stains. Some offshoot of the family must have fled for life with the necklace, and drifted abroad, then subsequently been merged into this tribe of Varteg. Did anyone ever hear so strange a story? And the strangest thing of all is that the pyrium should have retained some of its nature after the lapse of centuries—and merely painted on the stones at that. But stop. Did not Ia tell me that after wearing the necklace she could see her name? I begin to see a happy inspiration of her father here."

Holding the back of one of the centre stones—the five large drops—Colonna examined it carefully under a strong glass. As he did so, his eyes twinkled with satisfaction.

"It is there," he exclaimed, "and an artistic hand has been at work here. A weak solution of bhyrrh will restore the lost strength of the pyrium."

Colonna dived into his laboratory, presently to return with some milky liquid in a zinc bath, into which he plunged the necklace. This he carefully withdrew with a wire hook, and allowed it to stand till dry. On the back of the five centre stones, each nearly an inch in diameter, Colonna could trace something that resembled dull frosted letters. Even then the man of science did not appear to be satisfied. On the fleshy part of his forearm he pressed the back of one of the stones, and there retained it until two minutes had been ticked off on the watch. From the expression of Colonna's face, this operation was not free from pain, for his features were drawn, and his hands were tightly clenched together.

"A curious sensation," Colonna said with a sigh of relief as he removed the pressure at length. "Something like being tickled with red-hot feathers. And now to see if I am correct in my deductions."

Sure enough, when Colonna came to examine the white flesh, something very like a capital "I" seemed to be branded in purple upon it. Colonna appeared to be perfectly satisfied. From a long flexible tube by his side he produced some greasy, creamy substance, which on being applied to the scar caused it to disappear.

"A dangerous heirloom," he said. "Ian had no right to place so deadly a gaud in his daughter's hands without fully explaining its perils to her. Fortunately she has always implicitly obeyed the instructions not to wear it for more than five minutes. Ten would have been fatal without this antidote. Once justice has been done, I must rob the necklace of its fangs."

Apparently, Colonna was not yet at the end of his labours. Satisfied so far, he proceeded to turn his attention to the clasp of the necklace. The fastening was ancient, but no less ingenious for that. To a certain extent the spring had weakened. Once within his laboratory, Colonna rigged up a blow pipe and tube attached to the gas, and in this proceeded to soften the precious metal. An hour's work with a file and a pair of pliers completed the alterations to Colonna's satisfaction. On mature consideration he decided to remain until Ia called again. When the girl came, Colonna was ready to receive her.

"You feel satisfied," said Ia. "I can see it by your face."

"Perfectly satisfied," Colonna replied. "I had a happy thought just now, and decided to make assurance doubly sure. Tell me, has the Duchess ever worn the necklace?"

"Never yet in public."

"Well, it matters little either way. Here is the thing. I snap the clasp thus. Will you try and open it?"

With a smile Ia made the attempt. But she did not succeed.

"Strange," she murmured, "I have done it a hundred times before. Is this some of your wonderful witchcraft?"

"Not at all," Colonna replied. "I am an expert where old gold- and silver-craft is concerned. I saw at once that the clasp of the necklace was partially out of order or you could never have opened it from the swivel as you attempted. For the last hour or two I have been directing my attention to repairing the damage. If you will press your finger upon one of those raised studs the clasp will yield."

"I fail to see the point," said Ia.

"It is apparently a slight one," said Colonna, "but the point is of vital importance all the same. I so desire that, when the Duchess of Isleworth places this necklace about her neck, she will be powerless to remove it without assistance."

"The assistance of its real owner," Ia suggested with a smile.

"That will certainly tell in your favour," Colonna replied drily; "but that is not all. You will grasp the importance of it in good time. The Duchess is not above the assistance of art from the toilet point of view."

"She is terribly made up," Ia said tartly.

"Ah, I see you are a woman like the rest. So much the better for us. Take this little tablet and see that it is dissolved in the water with which the Duchess laves her face and hands to- morrow evening before dressing. It is merely something to harden the skin until the evening is well advanced. I don't want to say any more at present. Only, if I want you to-morrow night, be near at hand."

THE cream of the morning journals had indulged in no eagle

flights of journalese in alluding to the Duchess of Isleworth's

reception as a brilliant function. The season had been an

unusually smart one, the mortality amongst princelings had fallen

to the lowest ebb, and Society had lingered on longer than usual.

But the party in question was really the beginning of the

end.

By midnight the magnificent suite of apartments was crammed with beauty and intellect and fashion. For once every lady seemed to be pleased and happy, save the elderly host, who would have cheerfully seen the whole glittering pack thrown out of the windows if such a course had only cleared his drowsy path to bed.

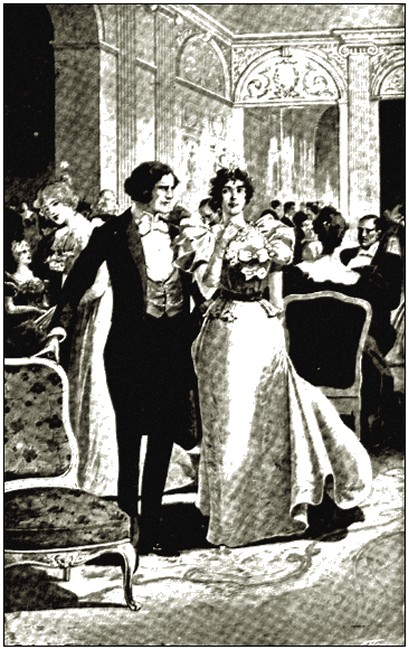

Never perhaps had the Duchess of Isleworth looked so superbly handsome. The liquid beauty of the great stones about her neck seemed to frame her loveliness in a stream of fire. She was listening with deepest interest to Colonna, who, in the centre of a circle, was discoursing of some poisons and their effects. Colonna was something more than the comet of a season.

She was listening with deepest interest to Colonna.

"I can scarcely credit it," said the Duchess. "This is a cynical age, doctor."

"From a professional point of view, no doubt," Colonna replied. "But I am telling you the truth. Those diamonds of yours, for instance."

"What of them?" the Duchess asked sharply.

"It is possible to render them more dangerous than a string of cobras. I believe those stones played their part in the police court recently. Your maid claimed them. I compliment your Grace on your generosity in that matter."

The Duchess smiled. But her eyes no longer met those of Colonna.

"You are not going to tell me that these heirlooms are poisoned?" she cried.

"Perhaps not," replied Colonna. "Those diamonds are centuries old—the gold-work proves it. Now I have in my possession a drawing of a necklace belonging to one of the Borgias which is absolutely a facsimile of the one you are wearing. The necklace in question played an important part in many a political crime. So far as I can gather, the distinguished owner finally incurred the displeasure of the Government, and had to fly for his life. Then comes the most extraordinary part of the story. The necklace turned up amongst a semi-barbarous tribe in Central America. As to the rest I can say nothing."

"Do you mean to say," the Duchess demanded, "that my maid's audacious story—practically the same as yours—was founded on fact?"

"Emphatically," said Colonna. "A strange coincidence, is it not? Still, as you say your necklace is a family heirloom—why—" And Colonna waved the suggestion carelessly aside.

"Positively, you frighten me," the Duchess laughed. "But we are not going to have our curiosity baffled in this irritating way. Let us suppose, for the sake of argument, that this necklace is the—well, the other one. Do you mean to say that the poison would still remain on it after the lapse of centuries?"

"Had that necklace been in the ark," said Colonna, "the effect would be equally deadly. Is your Grace ill?"

"No," came the hasty reply. "I have a strong imagination, and you startled me. What would the effect of the poison be?"

"The poison is just touched on the backs of the stones where they lie on the neck. After a quarter of an hour minute red specks appear, and the necklace seems to grow so hot that it can no longer be worn. In a few days—unless the proper antidote is supplied—the poison eats into the lungs, and before long the victim dies, apparently of rapid consumption."

As Colonna replied, he stole a rapid glance at his victim. He did not fail to note the yellow, sickly pallor of the cheeks, all the more ghastly under bloom de Ninon and powder of pearls.

The Duchess laughed again. "Then I am quite safe," she said. "I have worn my necklace over two hours."

"To keep up the play," said Colonna, "that does not free you. My ancestors were in the habit of preparing a more or less weak solution that they contrived to have applied to the skins of their victim, thereby nullifying the poison for one, two, or three hours, as the circumstances of the case required."

With which parting shot, Colonna backed away and melted into the crowd. It was nearly an hour before he approached his hostess again. That she was suffering physical pain, was patent to the meanest understanding. That she was frightened, the blank terror in her eyes proved. A shaking hand was clasped to her throat.

"Doctor," she whispered, "you may deem me mad, but positively I am suffering from all the sensations you described. Is it imagination or reality? These stones seem to me to be burning into the flesh."

"Imagination," Colonna suggested. "But why not remove the necklace?"

"I have tried to without attracting attention, but I cannot unfasten the clasp."

"Not loosen the clasp of your own necklace. You are joking with me!"

"Indeed I am doing nothing of the sort," came the passionate reply. "It appears to me to be some patent, ingenious affair. You say you have a facsimile drawing of this—would you mind trying to open it for me?" Colonna professed his willingness to do so, but either his fingers were clumsy, or he had forgotten the key to his own handiwork.

"I have failed," he said presently. "Shall I call in that audacious maid of yours? As she claimed the necklace, perhaps she can open it."

Had Colonna suddenly slashed his hostess across the face she had not cowered away from him in more fearful fashion. Sick and faint, she fell limp upon a seat. By this time a host of guests were standing by concernedly.

"I must send for your maid," Colonna said firmly. The Duchess held out a limp, detaining hand. But her strength was not equal to her resolution. The word was passed along rapidly, and in a short time Ia appeared. Colonna explained the situation to her.

"I can open it," she said with a certain proud humility. "It would be strange if I did not know the secret of my own property."

One touch and the string of limpid fires fell tinkling to the floor. Her Grace of Isleworth gave a great sigh of relief. She summoned up a smile to her lips. "It was nothing," she said. "I suppose my nerves are out of order—"

One touch and the string of limpid fires fell tinkling to the floor.

"Dr. Colonna," cried a voice from the crowd. "Dr. Colonna, what you told us just now was true. There are the red marks like letters on her throat——"

Colonna caught a shawl hastily, and threw it over the bare gleaming shoulders of his victim.

"Nonsense," he exclaimed; "a truce to this folly. The necklace was over-tight, and naturally that caused the irritation. Put the necklace in your pocket, Duchess, and do me the honour of taking my arm to some cooler spot. This room is too warm for you. Shall we try the library?"

The Duchess was perfectly willing. By the time the library was reached she had recovered the major portion of her self- possession. "I was horribly frightened," she said with a deep inspiration. "Am I marked, doctor?"

"Your Grace shall judge for yourself," said Colonna. His manner was curiously crisp and icy. On a table lay a Benares mirror framed in brass. As the Duchess flung off her wrap, Colonna held the glass before her eyes. She looked into it like a statue of terror. Well she might, for across the creamy whiteness of her throat were five letters in a thin crescent, standing out like characters of blood thus:

For full five minutes they both stood like characters in some striking tableau. With the pitiful face of a little child, the Duchess turned to Colonna.

"What does it mean?" she whispered.

"It seems to me," said Colonna, "that the solution is ridiculously easy. You stole that necklace from Ia Ian. Her story was true, as yours was false. You sold your own diamonds to pay your gambling debts, and you took Ia's to replace them. That is the identical necklace which was found by Ia's father among the Vartegs; but you know all about that as well as I do. Perhaps the poison after this lapse of time requires a longer time to act, perhaps Ia's father deliberately toned it down; but at any rate he has proved to whom the necklace really belonged. You must give it up."

"Oh, I will. I confess everything. I did take advantage of my position to steal it. But the poison, the poison. And I am not fit to die."

"You may make your mind quite easy on that score," Colonna said coldly. "You are not going to die. I may say that Ia was fortunate enough to fall in with me and tell me her story some days ago. At my desire she re turned to your employ, and at my request she brought me the necklace yesterday. Directly I inspected it I saw what was going to happen to the wearer; but I wanted to teach you a lesson, and get justice done at the same time. I have done both. Here is a little tube of an unguent which, if applied to your neck, will remove those marks, and nullify all evil effects. But I give it to you on one condition—you must clear Ia's name."

"And for ever lose my own."

"Not at all. The thing need not be done to-night. There need be no exposure. I am certain that Miss Ian will have no desire to cause you unnecessary humiliation. Come, you boasted just now that you had a strong imagination. We will give you four-and- twenty hours to think the matter over. The necklace you will give to me now. Can you see a way out?"

A flash of inspiration illuminated the face of the Duchess.

"I have it," she cried. "Place that shawl around my shoulders again. Now give me your arm."

The speaker swept into her drawing-room again, once more smiling, strong, and reliant. "Really, there was very little the matter," she said in a clear voice to those who had gathered eagerly around her. "Poison! What nonsense! Doctor Colonna was exaggerating. The reason of my distress was because just now I made a discovery that pained me deeply. I find I have done my maid an injury I can never wipe out. The necklace is hers after all. I only found it out when I discovered that the clasp is quite different to mine. The romantic part would take too long to tell here, but, almost at the same time as my maid showed me that necklace, I missed my own. Ah! the danger of a headstrong nature like mine! When I found to-night the injury I had done I was in despair. I racked my brains. Suddenly it came upon me that two years ago, in a fit of somnambulism, I had hidden some valuables in an old oak chest. At once I rushed to the place, and found——"

"Your own necklace," said the chorus.

"Wasn't it terrible?" the Duchess said, with a sweet, sad smile. "Good people, excuse me for a moment, as I must see Ia at once. Doctor Colonna, you have my scent bottle in your hand."

Colonna passed over the tube of unguent, and, with it tightly clasped in her hand, her Grace passed up the stairs like a trail of lambent cloud.

Her Grace passed up the stairs like a trail of lambent cloud.