ON Saturday afternoons there was peace in the Valley of Sweet Waters. Then the click and clack of pick and drill ceased, the grimy gangs went home and washed themselves, for the most part openly bewailing the fact that there were no licensed premises within five miles of the huge waterworks—works where eight thousand men were slaving and moiling to bring the glittering liquid pure across the Midlands. There was the canteen, of course, but the canteen was conducted upon narrow-minded lines, and with an abbreviated notion of the proper amount of intoxicating liquor requisite to the capacity of a self-respecting navvy. But there were ways of evading the authorities, as the said authorities sadly allowed.

The canteen was closed till dusk on Saturday, and thus eight thousand men, dotted in huts all along the lovely valley, were thrown upon their own resources. They played cricket with some vigour, they bathed in the mountain pools, there were foot races and long training walks—rambles frequently fatal to various poultry rambling thoughtlessly beyond the confines of the farmyards. Rabbits, too, were getting scarce, and Sir Myles Llangaren protested against the slaying of pheasants in August. He protested, too, against the poaching in Upper Guilt Brook, but this in a minor degree, seeing that the trout were small, albeit of excellent flavour.

As a matter of fact, three banksmen were poaching up above Guilt Bridge now. Two of them sat smoking and watching a third, who, prone on his stomach, was doing something in the stream with the aid of a stick and a fine copper wire. The thing looks impossible and absurdly insufficient, but there the captured fish lay.

"Got 'im," the fisherman grunted, lifting out a fat fish some six ounces in weight. "I dines at eight to-night in a dicky and black tie. Sort of family affair."

The other men laughed internally. The speaker was a short, powerful man, with glittering black eyes and dark snaky hair that had earned him the title of "Gipsy." The other two men were known as " Nobby " and "Dandy Dick," the latter reminiscent of an old playbill and of the fact that he usually wore a tie and had his hair with that pleasing plastered curl over the forehead which is called a Newgate fringe. Dandy also had a great, if vague, reputation for gallantry of a certain order.

As they sat there, another man came swinging up the valley. He also was of the navvy type, clean-limbed, with a suggestion of having seen service about him. He was dressed in black and wore a heavy pilot-coat, despite the heat of the day. He nodded none too familiarly.

"How do?" Gipsy shouted. The "How do?" of a navvy can be made hearty or exceedingly offensive, as the case may be. With the accent derisive on the first syllable it lends itself to quarrel in the easiest manner possible. "How do?"

The other passed on without any personal allusion to Gipsy's facial disadvantages, a fact that so astonished Nobby that he dropped his pipe and stared open-mouthed after the retreating figure.

"'Oo's'e?" he asked. "Call hisself a man! If Gipsy 'd hollered arter me like that, I'd ha' knocked his bloomin' 'ead orf. Straight."

Gipsy rolled over on his back in exquisite enjoyment. He belonged to the order of man who laughs at everything. Nobby's seriousness was a source of constant amusement to him.

"Calls hisself James Burton," he explained. "Ganger over Dandy's lot."

"It's a lie," Nobby said with emotion. "It's one of your lies, Gipsy."

"It ain't," Dandy struck in with equal politeness. "It's true. 'E's been about 'ere six weeks. Used to be a corporal in the Army, they say. No use, neither. Don't swear—can't, in fact. And when he wants anything, says 'Please. "

"Garn," Nobby said with withering contempt. "Ou'er gettin' at?"

Dandy reiterated his previous assertion, garnished with language that left no possible doubt of his absolute sincerity. Nobby had ceased to smoke for the moment. Mundane pleasures were as nothing in the contemplation of this phenomenon.

"Can't swear and says 'Please,'" he murmured. "Ow does 'e get the work done?"

"'E's after old Cocky Benwell's girl," said Gipsy, with meaning. He glanced at Dandy as he spoke. The latter winced ever so slightly.

"So I'm told," he said loftily. "But Lor'! what's the use? No chancer there."

Gipsy returned to the attack obliquely.

"I dunno," he said, with an air of profound philosophy. "Women's funny creatures. Goes in for flowers and all them things."

"Kate Benwell's very fond of flowers," said Dandy thoughtfully, "specially vi'lets. Stinking, I call 'em. 'Ad a bunch when I met 'er last night."

"Burton's got some fine vi'lets in his cottage garden," Gipsy observed. "Grows 'em under a frame in the cottage what he took from that Welshy bloke what's gone to Talgarth to live. Big blue 'uns with long storks, exactly the same as that Kate Benwell was wearin' in her boosum last night."

"I'd like to punch Burton's 'ead!" Dandy exclaimed with sudden passion.

Gipsy winked at himself with silent ecstasy. Nobby sucked at his pipe, regarding the sky with a rapt, stolid gaze. The humour of the situation was absolutely lost upon him, as the bright-eyed little man was perfectly well aware. His mental digestion was still seriously pained over the ganger who couldn't swear and said "Please" to his men.

"They'll be making me a ganger next," he said parenthetically. Nobody responded; the black-eyed man was waiting for developments.

Dandy broke out suddenly: "If a girl wants vi'lets," he said defiantly, "why, there's no reason why she shouldn't 'ave vi'lets. Come to think of it, they ain't much more offensive than bacca is to a pore bloke who can't stand smoke."

"Burton's are real beauties," said Gipsy. "Growed in a frame out o' doors where a man could 'elp himself after dark."

Dandy smiled. Gipsy's eyes conveyed nothing, though he began to see a pretty comedy opening out before his mental vision. Amusements were scarce in the Guilt Valley, and here was a fine way of adding to the gaiety of nations.

"No man could swear to a vi'let," Dandy said sententiously.

"Nor yet to a bunch of 'em, leaves an' all," Gipsy added softly. "You've got to put them all together and shove a bit of foliage round 'em."

Dandy took no heed of this original hint on the subject of floral decoration. He had gone off on his own train of thought.

"I dare say as other pore creatures up the valley—Welshies—grows vi'lets. Burton ain't got all the flowers in Wales, nor yet all the vi'lets neither. And if a man keeps them sort o' things out of doors nights, be deserves to lose 'em."

"Not as any of we 'ud take 'em," Gipsy grinned.

Nobby rose slowly, after drawing a ponderous silver watch from profound depths.

Gipsy took up his poaching apparatus again and adjusted the fine running wire.

"Just a few more," he said. "Where going, Nobby?"

"'Ome," Nobby said, with deep contempt. "It's six o'clock."

"Well, what o' that? We don't often get a chance "

"Chances be blowed!" Nobby growled. "Ain't it just six, and the canteen has been opened these ten minutes? And we wasting our time 'ere over a lot of silly trout as ain't to be named in the same day as a bloater. Come along."

This appeal, being too powerful and too cogent to be ignored, had the desired effect, and the trio made their way silently and thirstily down the valley.

UP to a certain time Dandy's feelings towards Miss Kate Benwell had been governed by a comfortable philosophy. He admired the girl, he had dallied with her on Sundays, but this had not prevented his liberal admiration of other women. He felt that as yet the easy swagger and the carefully oiled curl over his forehead ought not to be reserved for one of the opposite sex only.

Now things appeared to be different. That the Gipsy in his insidious way had brought about the change for his own wicked amusement. Dandy did not dream. Come what may, that poor creature of a Burton wasn't to have Cocky Benwell's girl. Besides, her eyes seemed to have grown brighter and her cheeks more ruddy of late. Critically examined, she was a prettier girl than Dandy had imagined. At the same time, she was a trifle more distant and cold than of yore. This fact landed Dandy in philosophic deeps, as it has often done in the case of cleverer men.

* * * * *

It was Sunday afternoon, and the valley lay bathed in the peaceful sunlight. Outside the long lanes of wooden huts, stalwart men in shirt-sleeves were minding small droves of children. Somebody was playing an accordion close by. There was a suggestion of rank tobacco-smoke on the air. Overhead a lark poured out a flood of melody. The shadow of a hawk was cast like a moving blight across the bracken.

A little further up the valley was a loose tangle of younger men. From the easy uneasiness of their attitudes they could only have been doing one thing. They were waiting for the coming of the fair, and their Sunday clothes troubled them sorely. A navvy in his working clothes is a fine sight, sometimes even an inspiring one; but the sombre raiment of the Sabbath is like a blight upon him. You can't see the magnificent torso, the knotted length of arm, the hard, lean flanks—nothing but a bunch of humanity.

Between two grinning, slouching lanes Dandy came down. He had a golf cap—plaid, with a huge purple and red star in the centre—planted at the back of his head, so that the glory of the plastered curl might not be dimmed, a handkerchief of many colours adorned his short bull neck, he had no collar, and his body was swathed in an enormous double-breasted pea-jacket many sizes too large for him. The moleskin trousers were also too long, but a pair of straps round the knees obviated that difficulty. He carried a white paper parcel in his hand.

Here was something for lambent wit to play upon. The youths ceased to chaff one another uneasily and with one accord turned upon Dandy. To flee was impossible; silent contempi would only have been accepted as a weakness.

"Carry your parcel. Dandy?" one suggested with humility. "Proud to."

Dandy turned with a smile. He was equal to the occasion.

"Couldn't do it," he said. "It's a diamond necklace for the chief engineer's wife. And you comes of a bad stock, Daniel. The last time as it was my painful dooty to give evidence agin' your old man—"

A burst of strident laughter finished the sentence. Daniel grinned redly.

"It's trotters," he said, "or pickles, or somethink of that kind. Give it a name, Dandy."

"It ain't trotters, nor cockles, nor winkles," Dandy said shortly. "It ain't the title-deeds of my new estate, and it ain't nothin' to do with nobody."

A weedy youth in an amazing check suit collapsed on the grass in a paroxysm of mirth. His comrades watched with affectionate anxiety.

"I've got it!" he gasped. "It's flowers, that's bloomin'-well what it is! A bookay with Dandy's best love to Kitty Benwell. 'Rose is red, the vi'let's blue, carnation's sweet, and so be you!' Blest if I can't sniff 'em!"

A score of more or less blunt noses were elevated in the air daintily.

"Like tripe, only more tender-like," said Daniel.

Before the roar of laughter that followed Dandy broke and fled. He was conscious of a hot, pricking sensation from head to foot. He would cheerfully have forfeited a week's wages to have preserved his secret intact. It would be many days before he heard the last of it. Many blighting retorts rose to his mind now that it was too late. He gripped the violets in his hand and shook them savagely. There was a wild impulse to hurl the offending package into Guilt Brook, but wiser counsels prevailed. The mischief was done now, and nothing could bring Nepenthe to the amused valley.

The reward came presently, however. From a bypath between the hills a girl emerged—a girl with an enormous feathered hat and plaid shawl, a girl exceedingly red in the face and black as to her eyes. Poets and painters and such effete people would have demurred to the girl's high colouring; another class of man would have summed her up as a fine woman. Dandy had made great sacrifice for her, and for the nonce in his eyes she was perfect.

"Who'd a-thought of seeing you, now?" he said breezily.

"Just what I was saying to myself, Mr. Dandy. Who, indeed?"

Dandy whistled with his eyes fixed steadily heavenwards.

"Going anywhere in particular?" he asked carelessly, yet with caution.

Miss Benwell simpered and looked down. Yet her eyes flashed alert and vigorous down the valley as if in search of somebody. She tittered. Under the circumstances she deemed it just as well to dissemble. Then

"Maybe I am and maybe Im not," she said archly.

"Well, that's just what Im going to do," Dandy observed. "So I'll walk part of the way there with you. Fond of flowers, eh?"

Miss Benwell remarked that she positively doted on flowers.

Dandy whistled again until the corners of his mouth relaxed into a broad grin.

"There's not many flowers as comes up to vi'lets," he said sententiously.

Miss Benwell agreed with enthusiasm. They were so sweet and so modest. Also she had read in the Society columns of a halfpenny novelette that they were such good taste.

"Especially blue 'uns," cried Dandy, catching her enthusiasm.

Yes, perhaps blue violets were on the whole preferable to the white variety. Their perfume was more pronounced and not too craftily subtle. All this Miss Benwell observed, averting her gaze most scrupulously from the paper parcel now getting unpleasantly warm in Dandy's powerful grip. As he stripped the paper away, the grin on his face broadened. He poked his fist rampantly under the girl's nose.

"For you," he said shortly. "A bookay. Wear 'em next your 'eart."

Miss Benwell couldn't have believed it. Anybody might have knocked her down with a feather. She placed the violets tenderly in the anatomical region suggested by Dandy.

"They are like some James Burton has," she said.

"Had," Dandy corrected. Then he recollected himself and proceeded craftily: "James Burton hasn't got any vi'lets like them. I got 'em up the valley; walked miles on purpose."

"Fancy that now!" Miss Benwell said sweetly.

"Walked my heels off almost, I did," said Dandy. "If James Burton, who's a poor creature and don't know the language—'ullo!"

The man in question stood before him. A man about his own build, with a pale, taciturn face and an eye that looked like power. His glance wandered from Dandy to the violets. His lips were parted, as if he had run far.

"You—you scoundrel!" he said. "I beg your pardon, Kate."

He turned on his heel with a slight suggestion of military salute and strode away up the valley.

Miss Benwell turned pale, flushed deep red, and tittered.

"Something disagreed with him," she laughed. "Better go this way, 'adn't we?"

Dandy gallantly replied that all ways were the same to him now. An hour or two later he returned to the huts with head erect and a sweet smile on his face. An acquaintance came down the road.

"'Ullo, Bill!" said Dandy. "So long."

"'Ullo!" the other responded. "'Ow nice you look, Vi'lets!"

Dandy stopped, clenched his fist, swore with fluency, and passed on.

GIPSY watched the progress of affairs from under his shrewd brows. He had engineered the whole business for his own amusement, and on the whole it was coming out beyond his most sanguine expectations. In towns Gipsy was a regular theatrical Saturday nighter, and under happier educational advantages might have blossomed into a dramatist. His first act had been eminently successful; the whole rugged community were laughing at Dandy, who, however, had his consolation in the fact that he had put Burton's nose out of joint for all time.

Still, all great victories have their drawbacks. For instance, it was by no means pleasant to be sniffed at by everybody. The boys were all whistling one air now, and on Dandy innocently asking the name, he was greeted with a chorus of "Sweet Violets." This tune he traced to Gipsy, still without suspicion of his friend's bona-fides.

"Why did you go for to do it?" he asked reproachfully.

They were all at dinner, with basins and tins between their knees. A little way off Ganger Burton was smoking in sullen silence. Though his vocabulary was mean and limited during the last day or two, there was an air about him that Dandy by no means liked.

"I never thought about you," the Gipsy said feelingly. "I was leading up to a joke. They tell me they was fine vi'lets that you gave to Kitty Benwell."

"No finer grown in the valley," Dandy responded shortly.

"And they say Burton was no end took, too, when you done him so fine." Dandy quivered. "More vi'lets where those others come from, I suppose?"

"Lots, if you go about getting them at night in the proper way."

"Then I'll show you how you can put the joke on to Burton. You go and buy a lot more of them flowers, and bring 'em down 'ere early on the ground in the mornin' afore Burton gets 'ere. Let every man stick two or three in his 'at or button-'ole, and there you are! See, old pal?"

To do him justice. Dandy "saw" immediately. The whole village bad divined exactly what was going on, and if this thing were done, every shred of ridicule would be shifted from Dandy's shoulders to those of Burton.

"Most likely drive him out of the shop," Dandy said joyfully.

"Do him brown altogether," the Gipsy responded. "If you ain't got the pluck to do it at the last minute, I'll show you a way "

"Ain't got the pluck! You see. Lor'! I'm laughing at it now."

So was the Gipsy. Only a close observer might have had a shrewd suspicion that he was laughing at his companion at the same time. Then he winked darkly and went his way.

Not one of the gang needed to be told the next morning that something was in the air. They were going to have some fun with their deservedly unpopular ganger, and that sufficed for them. Therefore when Dandy proffered all and several a few violets each next morning, the gift was accepted with a solemnity worthy of the occasion. Altogether it was a strange and moving sight, albeit correctly aesthetic.

"Not as we've any real use for them," said Dandy.

"No use at all," a big Cornishman usually called "Jigger" put in. Jigger was justly famed for his metaphors. "No more use'n side pockets to a toad."

Immediately upon this brilliant effort James Burton arrived upon the scene. He was more taciturn and deathly pale than usual. His eyes glittered strangely with the glint one sees in those of a newly-caged animal. It has been seen before now in the eyes of British troops when driven into a tight corner and orders are given to hold fire. They were the eyes of a man who was going to be dangerous when his time came. And the time was very near.

Nobody saw this save Gipsy. He began to understand that Dandy was going to get a warm quarter of an hour presently. He stripped to his grey shirt and peeled his black, powerful arms. Burton's quick gaze flashed along the slouching, smiling line of the gang. No need to tell him what had happened. Behind the anger blazing in his eyes there lurked the ghost of a smile. Mad as Burton was, he was not quite blind to the humour of the situation.

"What does all this tomfoolery mean?" he asked.

Somebody pushed the gigantic Jigger forward. He advanced with a wide, expanding smile.

"It's a sort of a club," he explained. "Don't you talk of your Primrose League no longer. This 'ere Vi'let League's the thing. It's all agin' drinkin' and swearin'—"

The speaker paused, blunderingly conscious that he had given the enemy an opening. Before he could recover himself, Burton shot in.

"I'm glad of that," he said. "Anything calculated to stop swearing will have my hearty support. You are a foul-mouthed set of blackguards, and there's a rascally thief now amongst you. And if you don't all get to work at once, I'll dock you a quarter of a day, certain."

For once Burton left off with the better of the argument. The whistle had gone and there was no time for reply. Moreover, if a man arrived a minute late, a ganger could put him back a quarter of a day, and repartee at something like threepence a word was too much like luxury.

Still, the gang could watch their leader under bent brows. He appeared to be taking less notice of them than usual, he seemed to be straining his eyes ever down the valley; he stood up erect and soldierly, like a sorely pressed outpost waiting for relief. There was more than one man in the Reserves in the gang who recognised the sergeant in that still figure.

Dandy alone was not satisfied; he shirked his work, he whistled offensively. Finally he took the stump of a cigarette from his pocket and lighted it with ostentatious care. A moment later and the cigarette was jerked into a puddle of clay, and Burton's heel upon it.

"You insolent scoundrel!" Burton said hoarsely. "I'll reckon with you presently. Move those bricks up to the head of the gully; get them done by dinner-time, or I report you for skulking. I'll teach you a lesson yet, my fine fellow!"

Dandy went limply about his task. He felt that he had a grievance against Providence. Moreover, he was properly impressed with the gleam in Burton's eye. Well, there were more violets in Burton's garden, and those violets had roots attached to them.

Where was Burton's gratitude, seeing that Dandy had thoughtfully spared a fine cluster of blooms under one of the glass lights? There was no chance of consulting Gipsy, who bent over his work in exemplary fashion.

At the first sight of real authority displayed by Burton, a moiety of the violets had disappeared. This was grovelling, and Dandy resented it accordingly. But Burton seemed to see nothing of the impression he had created, standing still and motionless, with his restless eyes strained down the valley. It was near dinner-time when a lad came up and handed an orange-coloured envelope to Burton.

He took it slowly and tore the cover. He read the lengthy telegraphic message with a blank, expressionless face, then he tore the flimsy into tiny shreds. Suddenly, without the slightest warning, he gave a yell that rang along the valley, after which he danced a hornpipe step deliriously. Before the astounded gang had grasped the situation. Burton was himself again.

"D.T.," said Jigger feelingly. There was a link between ganger and men at last. "I've seen poor beggars taken like it afore."

"It's j'y," said Gipsy, "that's what it is—j'y. And when the j'y passes away, pore old Dandy's goin' to cop a cold, see if he don't."

Burton walked through the gang unconcernedly until the whistle sounded for dinner. Then he darted vigorously down the valley, where presently a feminine figure joined him. It was only the keen eyes of Gipsy that discovered this, and amidst the babel of tongues Gipsy was strangely silent. The comedy had taken an unexpected turn, and his mind was busy scheming out a new dénouement.

DANDY stalked out of the canteen at an abnormally early hour considering that it was only Monday, and consequently there was no strain on the exchequer. But there are times when the cheerful cup does not cheer, and this was one of them. In the first place, Dandy's joke at the expense of Burton had lamentably missed fire, and all the afternoon Burton had handled the men with a vigour and fire that fairly dazed them.

Again, on the way to the canteen Dandy had met Miss Benwell. On attempting to take up love's dalliance at the interesting stage where it had stopped the previous Sunday, Dandy had been met with a chilling reception. Evidently something more than violets would be needed to heal the breach. At any rate, Kate Benwell should have no more of Burton's flowers. Dandy was enough of a horticulturist to know that flowers without roots were impossible. And he was going to take his measures accordingly.

Burton's trim little cottage was in darkness. His old housekeeper was gone, and Burton was away on pleasure somewhere, perhaps at Benwell's cottage. The thought filled Dandy with melancholy. His broad chest heaved with emotion.

It was getting quiet by this time, the canteen had closed, and the long lane of lights where the huts stood was picked out here and there with increasing gaps of darkness; presently the glow of Dandy's pipe was the only light to be seen.

Then he made his way cautiously into Burton's garden. He slipped the lights from the frames where the violets grew, and tugged at the roots. It was by no means easy work, and he lacked the necessary celerity for this kind of marauding. A score of yards away stood a hut, where tools and boxes and some cases of dynamite cartridges were stored. The dynamite had no business to be there, it was contrary to all kind of regulations, but there it was. And the lock was capable of easy picking.

Dandy crept over to the hut. The lock presented no great difficulties. Locks don't as a rule to gentlemen who wear Newgate fringes and are modestly silent as to their past. Inside the hut it was dark, but by the aid of his pipe Dandy found a draining spade—a long, narrow shovel, the very thing for his work. As he stumbled, the pipe fell from Dandy's lips and disappeared under a broad ledge. To find it now without striking a light was impossible. Well, one pipe was like another, and Dandy decided to risk it. Moreover, Burton might come home at any moment.

* * * * *

He was getting on with his work famously. Another moment or two and the last patch of fragrant blossoms would be no more. Dandy chuckled with the air of a man who has not toiled in vain. Then a nervous grip was laid on his shoulder.

"I want you, my friend," a voice said softly. "I've been waiting for this."

Dandy rose swiftly. It was pitch dark and as yet he had not been recognised. If it came to a fight, Dandy had no clinging doubts as to his chances of success. He could knock Burton down and make assurance doubly sure by flight. The plan of campaign flashed lightning-like through his brain. Ufortunately a counter-attack flashed through Burton's brain simultaneously. As Dandy lunged for him, he stepped aside, and down went the other with a smashing blow on the jaw.

The force of the blow fairly staggered the marauder. Dandy was no novice at the game, and he realised that he had met a master. Ere he recovered from the painful surprise, he was dragged by the heels into Burton's cottage and the door closed behind him. Every stick of furniture had been cleared from the room—it formed an ideal boxing-ring.

"Get up," Burton said pithily. "You'll take it fighting, I suppose?"

Dandy thought that on the whole he would. The sportsman would be content to give him a sound thrashing; if he shirked it, unpleasant magisterial proceedings might follow, and Dandy's feet had been too recently planted in the paths of virtue to risk that.

Taking it altogether. Dandy made a good fight of it. There was a huge swelling behind the ear, and his eyes were fast closing, also he was painfully short of breath. Finally, he lay on the floor with the haziest idea of his surroundings.

"Pretty fair for one out of training," Burton said quite cheerfully. "It's the canteen that does the mischief, my friend. Where did you get that spade from?"

"From the shed yonder," Dandy blurted out. "I picked the lock. I know you won't give a pore bloke away, but I dropped my pipe—"

"Dropped your what? Lighted?"

Dandy nodded. He was still too hazy to recollect the dynamite. With a cry. Burton dashed for the door. He stood there still as a statue for a moment.

"You madman!" he cried. "You careless, criminal fool! See what your pipe has done!"

The iron-framed windows were illuminated by a faint, unsteady glow. Down the breeze came the pungent odour of burning wood. The hut was on fire, and there was enough dynamite in it to destroy the neighbouring shanties like so many packs of cards. If the fire could be extinguished, and the cases of dynamite removed, nobody need be any the wiser, and no blame need attach to anybody.

"Come along!" Burton yelled. "There's water in the gully behind, and a couple of buckets in the kitchen. Get a move on you, and don't make any noise; if we can manage without disturbing the women and children, so much the better."

Dandy sat fettered by a sudden and all-conquering fear. Burton eyed him scornfully.

"A coward!" he said. "I didn't expect that of you."

Dandy would have protested, but his voice failed him. He was conscious of a certain grievance against Burton. He had just taken a severe punishment manfully and well, so that the accusation was in poor taste.

All the same, he was a coward. But for Burton, standing like a contemptuous sentinel in the way, he would have bolted. His idea was to have rushed yelling down the valley that a dynamite shed was on fire, and then placed a space as wide as possible between himself and the danger,

"You've got to come with me," Burton said grimly. "You cur! I'm just as frightened as yourself, only I'm not going to give way to it. I'm a soldier, an Engineer, and I know what the feeling is when the enemy are waiting for you behind cover, and you've got to advance whether you like it or not. Every man is more or less of a coward then. And if I'd given way to it, I should have been kicked out of the Army. But I didn't give way to it, and in a few weeks I shall have my commission. I came here on two months' furlough because there was a cloud hanging over me. But, thank God! my name is clear now, and the blackguard who tried to ruin me is found out. You thought I was a soft kind of fellow. I could have drilled you all. I'll drill you my lad! Come along with me. March!"

Burton spoke rapidly and clearly. There was the real ring of command in his voice; his eye was the eye of a born leader of men. Dandy obeyed mechanically. He could not have helped himself. He wondered vaguely what had come over this man. What a fool Gipsy had been!

By this time the fire had a good grip of the hut. There was water in the gully behind, and buckets. Burton threw open the door and entered. A fierce blast of heat and a pungent wrack of smoke drove him back. It would be impossible to do anything till the flames were driven back. After all, it might be necessary to rouse the people in the huts.

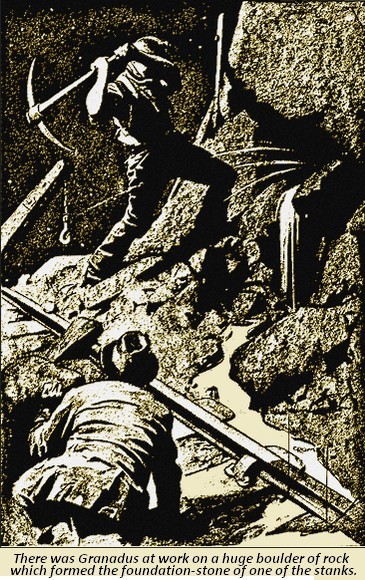

But not if Burton could help it. He and Dandy were working grimly now, hustling backwards and forwards with buckets, fighting the flames back inch by inch, taking their lives in their hands at the same time. As the smoke lifted sullenly, a big case of dynamite at the back was seen to burn furiously. Burton groaned to himself, his teeth close shut.

"How do you feel now?" he asked hoarsely.

Dandy wiped his streaming face. He was running wet, the beautiful Newgate curl was no more than a damp clout now. There was a queer, grey pallor under the tan of his cheeks. He laughed unsteadily.

"Funk!" he said—" blooming funk ain't no word for it. If I was by myself, I'd just 'ook it and 'owl. But I don't like to leave you."

The shamefaced Dandy would have been astounded to hear that this was courage of the highest order. But Burton's Egyptian experience had told him all about that. He patted the palsied Dandy on the back approvingly.

"We've got to get those back cases out," he said. "If we can manage those without a blow-up, the rest is plain sailing. Come along. Men have annexed the Victoria Cross for less than this."

Dandy moved forward. There was a queer choking in his throat, and he could hear his heart beating like a drum. But he was not going to be bested by Burton. They fought desperately up to the burning cases; they worked at them until their hands were covered with white blisters. But they had got them out at last. Blackened and blistered and bleeding, wet as rags from head to foot, Burton let off a jell that rang all down the valley. They had won.

"The other two—quick!" he said. "Now the water. We're safe, my lad."

A bucket or two of water and the thing was done. Dandy dropped upon a pile of clay, limp and exhausted. He was trembling like one after a long, weakening illness.

"I ain't coddin'," he said, " I ain't jokin'. Far from it. But I'm goin' to faint—me! me! Rummy, ain't it?"

He spoke half with a sob, half with a defiant growl. Burton produced brandy and poured a little down Dandy's throat. The burly, deep-chested navvy staggered to his feet. For some little time he seemed unable to speak. "You won't give me away?" he asked. "You're a man all through, that's what you are, and I'm a fool to doubt it. But seeing as I did my best bloomin' coward or no bloomin' coward—you won't let on as I showed the white feather?"

"Rot!" said Burton. "Give me your hand."

"What for? "Dandy asked suspiciously.

"To shake, of course. Because it is the hand of a hero. My good fellow, the man who conquers fear as you did is a hero. I never saw a braver thing done, and I've seen some plucky things in my time."

"If you hadn't been here," Dandy began, "I should've 'ooked it straight."

"I say you are a hero," Burton persisted.

Dandy graciously allowed it to pass. Way up the Valley of Sweet Waters they are still inclined to make much of Dandy, but he resolutely declines to be lionised.

But for Burton he would "'a' took and 'ooked it," and to this Dandy steadily adheres. But he didn't "'ook it," and Burton was there; and this is the history of a little of the British Army.

"All right, matey," he said, "'ave your own way. So long."

* * * * *

"She'd never 'ave 'ad aught to do with yer, Dandy," Jigger remarked to a select circle in the canteen. "Why, she's been engaged to Burton for four years. Eddicated better'n you think. And Burton's gotten his commission. There was a lot of trouble at Salisbury over some missing stores, and Kate Benwell got 'im a job here. Women's funny things. Dandy."

"Yes," Dandy said laconically, "they be. So's men, come to that."

There was a long silence, filled by the puffing of pipes and the tilting of tankards. Gipsy lay back smoking his cigarette.

"I never could see much fun in that vi'let business of yours, Dandy," he said.

Dandy looked up suspiciously. His mind was travelhng swiftly over recent events. Then he began to discern patches of light in dark places.

"Perhaps not," he said indifferently. "Happen as you know'd something about Burton before?"

Gipsy fell into the trap.

"Old Benwell telled me," he said. "Only it was a secret."

Dandy rose slowly to his feet and pointed to the door. A fine, flashing scorn was in his eye; anger filled his heart.

"If you'll come outside," he said slowly and ponderously, "just step outside for a few minutes, I'll make you as your own mother won't know you. I ain't a vindictive man—far from it—but I'd esteem the punchin' of your 'ead as real luxury."

But Gipsy was equal to the occasion. He hailed a passing potman.

"Fill all those cans," he said. "Boys, 'ere's the 'ealth of the bride and bride-groom! And if they don't make Dandy best man, they ought to be ashamed of themselves."

GIPSY removed his cigarette and glanced at the stranger. He was a small man, with garb reminiscent of towns—a frock-coat struggling with adversity, a glossy top-hat, owing its refulgent rays to benzoline. For the rest, the man was red, and had sanguine eyes behind glasses. He carried a big portfolio under his arm.

"If it ain't a rude question," Gipsy said blandly, "what the dickens are you after, mate?"

This was the dinner interlude. The clink of pick and the rattle of drill had ceased, and gang B14 were feeding, for the most part, out of red bandana handkerchiefs. Gipsy's cigarettes gained flavour from curiosity. Antiquarians and archaeologists he knew, but the specimen before him was quite new. He had never seen a book-agent before.

The small man, wandering into the big engineering camp high up the Valley of Sweet Waters, needed no more cordial greeting. The tiniest spark of curiosity blew up the floodgates of his loquacity. The glib words flowed on.

"'Arf time," Gipsy cut in. "The mate what shares my 'ut 'as got a parrot. Maybe as you might teach him to say a few words."

The little man smiled, nothing abashed. He spread out before Gipsy's admiring eyes a series of illustrations, views of the world at large, maps, sections of the human form divine, models of more or less up-to-date steam-engines—the whole pictorial art as applied to the "Universal Compendium Encyclopsedia," complete in twelve monthly parts at seventeen and sixpence per volume, first instalment down, the balance on faith. The book-agent is childlike and trusting, possibly because the seventeen and six down covers any predatory leaning on the part of the thirsty knowledge-seeker.

"That's what you want," said the little man, with fine insight. "This dictionary in itself, sir, is a liberal education. There's nothing—nothing that you won't find in it."

"Think so?" Gipsy asked doubtfully. "Anything about prizefights, mister?"

The little man pointed to a full-page drawing of a Roman gladiator, obviously pirated from one of the late Lord Leighton's drawings. He would like very much to know what Gipsy thought of that. The navvy was properly impressed. He regarded the gladiator's biceps critically. With a fund of knowledge like that, he would be uplifted over his fellows. Seventeen and sixpence was not much whereby he might be placed intellectually on a level with the resident engineers at Cwm House. Besides, when the thirst for knowledge played subordinate to thirst of a more commonplace character, and the exchequer was low, the volume would pawn in Rhayader for the requisite silver.

Gipsy rattled some money in his pocket. They were a sporting lot up the valley, and Gipsy's second in the Derby "sweep" had brought in a matter of over six pounds. He hesitated; seventeen and sixpence was not so much to a bachelor sharing a hut and drawing thirty-two shillings a week.

"I'll take it," he said. "And 'ere's the first money down."

"Then I'll book your order, sir," the little man said. Gipsy swelled with pride. His vivid imagination was running ahead of the present; there were reminiscences of the Industrious Apprentice in his mind.

"Perhaps your other volumes may come a little under the month, in which case—"

"Oh, I shan't mind that," Gipsy said largely. "You make out the paper."

"Certainly, sir. In that case, Form B is the one for you to sign. Your name, sir, please? Gipsy? Very good. And your Christian name, sir?"

All this with a humility that filled Gipsy with a pleased sense of importance. But as to the Christian name, there was a hitch. Did he possess one, it was lost in the backwash of boyish memories. He had never been called anything but Gipsy. At his feet lay a fine, florid drawing of Hercules. Gipsy spelt out the word slowly—his infinite resource came back to him.

"Rum thing," he said. "My Christian name's the same as that knobby bloke with the belt round his waist. H-e-r-c-u-l-e-s. Call it Herkules Gipsy, and you've got it first pop. What yer laughin' at?"

The little man explained that he wasn't laughing at all, it was merely a chronic catarrh, from which he had been a victim from boyhood. Gipsy scratched a pleasing hieroglyphic at the foot of a long, blue form, the benzoline-glossy hat was lifted with a flourish, and Gipsy was alone with the key of knowledge in his grasp—cheap at seventeen and sixpence.

The publishers of the "Universal Compendium Encyclopaedia" were less trustful than a first casual glance would have disclosed. But then Gipsy knew nothing about "remainders" or the fact that many old works of this nature—fruits of failure and bankruptcy of bygone publishers—are sold as so much waste-paper, the body or corpse being subsequently clothed in new outer garments and peddled to a confiding public through the medium of many little men with dilapidated frock-coats and hats resplendent of benzoline. As a matter of fact, had no further payment been made, the Universal Compendium Publishing Company would have lost nothing—which fact Gipsy did not grasp, as also he had no idea that he had signed a form consenting to receive the balance of the volumes monthly, or more frequently should the publisher deem the latter course expedient. Within a month the rest of the volumes did arrive, carriage paid, in a neat box, plus an invoice for something over £10, with a footnote to the effect that if the balance were not paid within fourteen days, proceedings for its recovery would be taken without further notice.

All this, however, escaped the usually sharp eye of the seeker after knowledge. It was very good of these people to send on the books which need not be paid for yet. Meanwhile, Gipsy was progressing with his liberal education. He knew something about Adam, who seemed to be mixed up in some way with a peculiar kind of fireplace; he gained some new information about Africa; of Agriculture he hoped presently to speak with authority; Algebra he was forced to ignore altogether. But the greatest delight lay in the pictures—twenty in each volume, harnessed to the text in the most indiscriminate fashion, but there they were.

It was not to be supposed that so fine a sportsman as Gipsy could have kept his new possessions a secret. There were those who scoffed, but others who firmly believed. Mothers came to know if the big book had any hints as to the teething of children, or the proper treatment of warts, whilst a third desired information as to the best way to boil cabbages; young navvies, with an eye to a hut of their own, asked Gipsy quietly if the book had any hints as to good, plain furniture, and the best way to get it on the instalment plan.

"I'm doing my best for the settlement," Gipsy replied. "It's a tough job, this 'ere liberal education, and apt to get confusing. I can't quite make out where I am sometimes. There's Anatomy. Now, is it a new kind of metal or a Colony in South Africa? But it'll all come right in time. Only I ain't found anythink about warts or furniture in the book as yet."

"Look the warts up under 'Antibilious,'" Mitchell, the painter, suggested. Mitchell was a man who had bid fair for fame as an artist at one time, only he could never keep sober for more than a week at a time. He had a fine, cynical humour of his own, a keen eye for character-study, and Gipsy, with his dramatic instincts, fairly fascinated him. "You've got the chance of becoming a great force here, old man."

Gipsy growled uneasily. He had a vague feeling that Mitchell had once been a gentleman. He was a master of phrases, too. But amongst the ten thousand navvies working, there were many who could have told lurid life-stories besides Mitchell, the painter. Dandy, standing by, sneered openly.

"What's the good on it," he asked, "when you can get Reynolds's every week for a brown? There ain't a good rattlin' bloomin' murder in all this volume what Gipsy's so set up about."

Gipsy smiled in a superior manner. Dandy eyed him with disfavour—he seemed to be on a different plane to his old mate now.

"Canteen's open," Mitchell suggested. "Come along. In the full flush of newly acquired knowledge, Gipsy ought to be able to tell us something about beer. Letter B, all in Volume I. of the Compendium."

"If you only knew what it was made of," Gipsy said in his most superior manner. All the same, he was moving towards the canteen with the rest. "There's a thing called quashyer—"

"If it was made o' mud flavoured with rotten eggs an' ditch-water," Dandy said vehemently, "it 'ud be all the same to me. Beer's beer. Been fond of it all my life, and ain't going to turn from it for all the Compendiums as was ever wrote."

A murmur of applause followed. Gipsy so far bent to popular opinion as to take a pint of the amber fluid himself. Sooth to say, he was a little tired of the Compendium. It was beginning to dawn before him that he could not live up to it. For the last month he and Dandy and Gammon had not had one poaching excursion together.

"I don't want to keep that book to myself," he said. "I'm all for public spirit. I'm going to turn it into a free library—one volume a week, turn and turn about. The subscription's a bob, limited to a 'undred. I'll collect that bob from a 'undred of you, and—"

"Bet you a tanner you don't collect five of 'em," a sportsman in the background suggested.

"Them as likes to jine, 'old up your hands," Gipsy said loftily.

There was no headstrong desire to comply with the request. The Higher Education found no favour in the camp. Two shillings only were proffered, both coupled with the suggestion that the coin should be promptly disbursed by Gipsy in the universal liquid. But even more enlightened communities have shown themselves averse to the blessings of the Free Libraries Act. Gipsy made a few scornful remarks, passed in tolerating silence.

Comparatively early the seeker after knowledge left his hut. Mitchell, the painter, accompanied him at his request. Dandy openly flouted his old ally and companion. Once the Compendium was a thing of the past, they might join forces again; meanwhile Dandy avowedly preferred the company of Gammon. It was a blow to Gipsy's pride, but he swallowed it.

Mitchell, the painter, was enjoying the comedy in his grave fashion. He had forgotten many things in his fall, but the dry humour of the born cynic had never failed him. He was laughing at Gipsy consumedly; but the latter was in bland ignorance of the fact. He jerked his thumb hospitably towards the spare chair in the hut and passed the tobacco.

"Wishing you hadn't gone in for higher classics?" Mitchell suggested.

"Got it first time," Gipsy said moodily. "It didn't sound much at first; but when I comes to think serious like over that seventeen bob a month... besides, I got all the books. And now they've sent me three papers that I can't make head or tail of. Like to see 'em?"

Mitchell nodded, and Gipsy produced three oblong sheets of dingy paper with the Eoyal Arms on the top. They were vague and depressing documents to the uninitiated, but Mitchell had had long experience in such matters during his careless days.

"What are they all about, mate?" Gipsy asked anxiously.

"County-court summons, to begin with," Mitchell explained. "According to the particulars attached to the summons, you signed an order for these books to be delivered as the publishers deemed fit. As you didn't pay on delivery, they have issued this summons—with costs, £13 9s. 4d"

Gipsy exploded into a genial laugh. The faith in his purse amused him.

"Go on!" he cried. "Me pay £13 and nine bob and fourpence. Hope they'll get it."

"Hope they will," Mitchell proceeded genially. "You took no notice, and judgment went by default."

"Sounds like a bit from the Compendium," Gipsy muttered. "Go on."

"So they issued a judgment summons, which costs you another ten shillings. As you ignored that, a committal order was made against you, as this third notice tells. Order suspended for fourteen days, but up to-morrow. You don't seem to understand, my friend. You ought to have appeared at Rhayader and explained matters to the judge. If this money isn't paid to-morrow, you will have to go to Brecon Gaol for six weeks. Why didn't you tell me before?"

"What!" Gipsy roared. "An' this a free country an' all! Lord! what a fool I've been! If I only 'ad the little cove with the slimy 'at 'ere now! Comin' along and takin' advantage of a poor, ignorant bloke like myself. An' thirteen pound nine an'—"

Gipsy paused, utterly overcome with the weight of this startling discovery. He sat in a dazed kind of way whilst Mitchell expounded the procedure of county-courts and the law as affecting the safety of the individual when the said individual had contracted a debt that he could not pay.

"If you had appeared to the summons," Mitchell said, administering what looked like very late comfort, "he might have let you off your bargain. At any rate, he would have made an order for payment at a few shillings a month, or something like that. As it is, you must pay at once. Of course, you have been the victim of a book-agent's dodge, but that doesn't help you much."

Gipsy groaned, and the flavour faded from his tobacco.

"An' all this for books!" he said scornfully—"books! Things I can't understand. I've puzzled over the things yonder till I've got a 'ead like Sunday morning. If it 'ad been for something as 'ad done me good! What shall I do about it, matey?"

Mitchell shook his head gravely. He looked deeply sympathetic. It was lucky for him that he could enjoy comedy without outward evidence of the fact. He could only suggest flight to some town. But Gipsy had cogent reasons for the peaceful seclusion of the country. He'd wait till the police came

"They're not police," Mitchell explained. "They are county-court bailiffs—probably there will be two of them, and they'll come from Rhayader. If I were you, I should go to a place where the air was more suited to your peculiar complaint."

But Gipsy declined to listen to any such temptations. His popularity counted for something. He would take a day off to-morrow and borrow the money, levying a small rate for the purpose. But, despite the measure of his popularity, Gipsy met with a cool response. The Compendium gave no play to the imagination. If Gipsy had lost a wife, for instance, or if he had assaulted a gamekeeper and was seeking to make up a tine, it would have been a different matter.

A man who wasted on classic literature hard money, that might have been spent on beer and tobacco, deserved no sympathy. A long morning's toil produced something under twenty shillings, most of it gleaned with the point of the bayonet, so to speak. In a lofty spirit, Gipsy had set out with the amiable intention of taking no more than a shilling from each man. Early in the day he had refused sevenpence in coppers with lurid language, by dinner-time he accepted a threepenny-bit from a despised teetotaller, with a wan smile. Literature is ever a thorny path.

"To think that I had come to this!" he said bitterly to Dandy in the dinner-hour. "This 'ere Joey I got from 'Anks, what's a rabid teetotaller. An' glad to get it. Well, mates?"

A gleam of the old geniality lighted Gipsy's eye as two strangers lounged up to them. There was a hard look about them; there was no sympathy in the eye of either. The taller of the two produced a paper.

"Looking for a party over a little matter of business," he said. "Name of Hercules Gipsy."

Dandy started and opened his mouth widely. Gipsy turned pale. If Dandy spoke, he was lost.

"Herkules Gipsy," the little man said thoughtfully. "Why, that's my old pal, dash my wig if 'e ain't "

Gipsy's thoughts were full of murder. His tea was hot—he thoughtfully poured about half a pint over Dandy's leg.

"What you make all that row about?" he growled. "I know who you mean, matey. It's a chap 'ere what bought a Compendium from a little bloke with a shiny 'at. If I'd got 'im 'ere—leastways, I—well, there! Gipsy told me all about it last night."

"Are you come to arrest 'im?" Dandy asked with sudden inspiration.

"For debt," the big stranger explained curtly. "Non-payment of a debt on county-court judgment."

"Seen 'im lately?" Gipsy asked carelessly and perspiringly.

"Seen 'im this mornin'," Dandy replied. "Got all his best on, and his other things done up in a 'ankerchief . 'Goin' to North Pole?' I says. ''Ookin' it,' says he. 'What for?' says I. 'Got into a bit of a mess,' says 'e. So I let 'im go, and there's an end on it."

"Unpopular, surly sort o' bloke, he was," Gipsy said thoughtfully. "Never did nothing but poke about in readin' books or that kind o' thing. Bet a tanner 'e's gone to Rhayader to look after 'is wife."

Dandy volunteered further details. Hercules Gipsy owed him a lot of money—he owed money all round, in fact. Dandy was glad that he had got into trouble. The strangers moved on presently and were lost to sight down the valley. Gipsy sat on a stone and wiped his beaded forehead.

"I owe you one for that, mate," he said. "But those chaps'll come back again. It mayn't be to-day, or yet to-morrow, but they'll come. And what's the good o' this?"

Gipsy displayed a big fist with some poundsworth of dingy silver in the centre of the hard palm, and snarled at it with bitter contempt. Dandy smiled. For the middle of the week this was wealth.

"I pulled you out of that, old 'un," he said. "An' a man don't think fast on a 'ot day like this. Might as well be 'ung for a sheep as a lamb."

"Righto," Gipsy said recklessly. "Come on. This way to the waxworks. It's going to be sixes."

The canteen stood invitingly open, the day was hot. The full measure of the canteen allowance was partaken of, and then the pair slipped out of the Settlement to the inviting shade of a public-house opposite. As Gipsy's pocket grew lighter, his spirits rose.

"I'll go and lie down," he said hazily. "I've got a plan. Dandy. I've got a plan, if I could only think of it. It's a very good plan, mate. I'll raise the money and pay off the little bloke in the glossy 'at. No, I won't, I'll keep the brass and see him further first!"

He pulled his cap fiercely over his eyes and strode resolutely in the direction of his hut. Dandy sighed into his empty mug and followed with discreet silence.

* * * * *

For the time being the philosophical side of Gipsy's nature was submerged. He had expected better things of his fellow-men. Also there was the blow to his pride. He had yet to learn that when popularity pulls against pocket, the struggle is a terribly unequal one. Anyway, this money must be found. Gipsy had tried to raise the rate openly and upon the strength of his individuality, and he had failed. He had no intention of going to gaol—his Romany blood turned cold at the mere suggestion; he would resort to strategy.

The man was a born dramatist and a maker of stories, only a beneficent legislation had not caught him early enough to teach him the proper equipment. He approached the matter now from the point of view of the novelist who has got his hero in a tight place and is bound to get him out of it again.

As Gipsy sat over his pipe, illumination came to him. He must impose upon a credulous public. A wide grin expanded over his face. He took down the volumes of the Compendium and selected a dozen or more of the engravings therein, and then by the aid of his knife he detached them neatly from the bindings. The plan of campaign was perfect. Gipsy waited now to see Mitchell, the painter, who took his evening stroll about this time. Presently the artist lounged along.

"'Arf a mo'," Gipsy drawled. "Want to earn a quid?"

Mitchell shook his head doubtfully. As a rule, his elderly housekeeper drew his pay and allowed him a certain modicum for tobacco-money. It was the only way in which the artist could possibly wrestle successfully with the drink craze. Give him a sovereign, and he would do nothing till it was gone.

"How long have you been a capitalist?" he asked. "Left over from the library, eh?"

Gipsy said something forcible on the subject of tabloid education. He pointed to the selected engravings taken by him from the Compendium.

"What a fool thing to do!" Mitchell expostulated. "Poor as the volumes were before, they are worth nothing now. You have utterly spoilt them."

Gipsy winked solemnly. There was all the air of a successful dramatist about him.

"I'm going to get you to help me," he said. "You just go and get those paints of yours—the oils. Bring all the pretty 'uns. I've got to get out of this mess; and if I ain't just a bloomin' Bobs at this game, strike me pink! Look at this bloke."

At arm's length Gipsy held up a counterfeit presentment of Hercules in a boxing attitude. He stood on a pedestal and was obviously "after" some celebrated statue or another. Gipsy eyed the muscular form admiringly.

"That's a model of physical development," Gipsy remarked. "The blighted Compendium says so. Also it's a work of art. Just so. An' if I took and tried to raise a bob on old 'Erkules in the canteen, I couldn't do it. But nobody's seen 'Erkules, which is a good thing. He's no good now, but you'll see when we've done with 'im. Go and get your paints."

There was comedy here somewhere, as Mitchell recognised. He had a profound admiration for Gipsy and his many "slim" expedients. He came from the class of men who know how to jest with a straight face. Mitchell came back presently with his oils and brushes, and Gipsy carefully locked the door before lighting the lamp.

"Now look 'ere," he said. "You've got to 'elp me over this job, matey. We've got to raise the spondulix from the delooded public. You just tackle old 'Erkules as I tell you. Take and paint 'im in tights, and a championship belt round 'is middle. Shove them bunches of fives of 'isn into four-ounce gloves."

"Make him a boxer and a bruiser up to date?" Mitchell asked with a grin.

"That's the time o' day," Gipsy said drily. "Up to date. Turn that 'ere butcher's block what he's standing on into a platform, and a rope round it. Wade in."

Mitchell waded in accordingly. At the end of half-an-hour the classic engraving of the famous athlete was transformed into a glaring oil presentment of a modern boxer of the approved type. Mitchell had been purposely prodigal of his colouring, and Gipsy was loudly enthusiastic. The flagrant vulgarity of it appealed to him strongly.

"Spiffin'!" he said. "Just the ticket for soup. All it wants now is a nice 'omely flavour of the pub about it. Just stick a red triangle with 'Bass's Beer Only' underneath, just behind old 'Erkules's 'ead, and there you are. What!"

Gipsy stood back and surveyed the work critically. Its crude colouring and flaring vulgarity touched him to the soul. No British "navvy " with a grain of sport in him could look upon that picture without the longing for possession.

"How long before it's dry?" he asked.

"Dry now," Mitchell explained. "That porous paper soaks up the oil directly. This is my masterpiece, Gipsy. I never hoped to paint anything like that."

Gipsy nodded approvingly. He was in the presence of genius. He took the picture up and rolled it with the greatest care. He was going out, he explained, as far as the canteen. If the painter possessed the fund of humour that Gipsy credited him with, that virtue would be gratified if Mitchell would look into the canteen a little later.

The canteen was pretty full as Gipsy entered. He took up his place at an empty table and spread out his work of art before him; he appeared to be in rapt and admiring contemplation. Presently one or two of his own gang lounged across, to see the cause of this thoughtful silence. They fell under the spell of Mitchell's genius.

"What is it, Gipsy?" asked one in an awed voice. "Where did you get 'im from?"

"Won 'im," Gipsy said carelessly, "in a raffle. A bob a share—last time I was in Cardiff. O' course you know who that is?"

"Bloke just trained ready for a mill, I reckon."

"Bloke ready for a mill!" Gipsy said, with bitter scorn. "Where do you come from? Was it four or five years you got? That there's Tom Flannigan, the Irish Terror, just before his successful scrap last March with Long Coffin, the American Champion. Knocked 'is man out after thirty-two rounds, lasting two hours."

The others gasped. The famous fight was still fresh in the recollection of most of them. It was impossible to look upon that form and those colours unmoved. Gipsy pinned the picture to the matchboarded wall behind him, and the hands crowded round to admire. No famous creation from a fashionable artist hung on the line attracted such respectful attention.

"I've got others," Gipsy said. "I value 'em at eight 'undred pounds. There was ten thousand put into that raffle, at a bob a nob, and I got first prize. Came by parcel post to-day, they did. Make me wish I was a married man, it does. To think of a 'ut, with some good sticks o' furniture, and them things 'angin' on the walls!"

"Want to sell it, Gipsy?" a distant voice asked anxiously.

Gipsy looked up, caught the eye of Mitchell, who was standing in the doorway. Neither man smiled; but if both had shouted with laughter, they could not have understood one another more perfectly. The luxury of the comedy was theirs alone.

"Well, I wasn't thinking about it," Gipsy said slowly. The suggestion appeared to give him a fresh train of thought. "It ain't often as a poor bloke like myself gets a picture what lots of nobs would be proud to 'ang in their drorin'-rooms. But I've 'ad misfortunes, as most of you know, and a few pounds—what'll you stand, Jimmie?"

"Ten bob," Jimmie said promptly, "an' a go of gin."

Gipsy snorted. If it had been pounds, now! He stood up, as if inspired by a new idea. The full light of the lamps shone on the dazzling colour picture. Why not raffle it at a shilling a share? Say sixty shares at that modest figure. A responsive murmur followed. Half-an-hour later, Gipsy strolled thoughtfully homeward with a bulging pocketful of greasy silver coins. Mitchell followed. After all, there were other acts to follow, and the first had been excellent.

"You'll get on," the painter said. "I should never have thought of that."

"Came to me like a perspiration," Gipsy said modestly. "Only I might 'ave waited a little longer. Believe I could 'a' got the whole bloomin' thirteen quid out o' that 'ere effort o' yourn. But there's more where the other came from. 'Oo's this?"

"That is a portrait of Sarah Siddons, the great tragedy actress, after Romney," Mitchell explained, as Gipsy proffered him a further illustration from the Compendium. "What do you propose to do with her? Leave us some of our illusions, Gipsy."

"She'll do," Gipsy muttered. "She's going to be the cellubrated Miss Netta Montgomery, what played in Nelson's portable theatre down at Cwm all last winter. Every single bloke in the settlement was fair gone on her, though I found 'er second-class myself. Lot o' yaller 'air an' a dress all over spangles. You know the sort of thing. Then I'll get another three quid for that. 'Ere's a cottage and what you call a landscape."

"Anne Hathaway's cottage," Mitchell murmured.

"Niver 'eard of 'er," Gipsy went on. "But it's goin' to be made into the Red 'Ouse up the valley, where the shepherd killed his wife in the spring. Put a few piles o' timber and a derrick in the background, and there you are. I shan't do much with it amongst the boys, but the wives will fairly rise to it. Give 'em a touch of the 'orrors, and you've got 'em every time."

Mitchell nodded. His face was grave, but his eyes danced with amusement. The oil was burning low in the lamp before he had finished his work. There was an expression of placid contentment on Gipsy's face.

"Come in to-morrow and do the other one," he suggested. "Strike me! I shan't want to trouble you any more after that. 'Picture of the Bronze 'Orse at Venice.' Touch 'im up, and put a boy in a pair o' tight breeches leadin' 'im by a 'alter, and there's the winner of the year's Derby what most of us backed. I'm goin' to pay for the bloomin' Compendium on this job, so as it'll cost me nothink. So long."

The following evening was a busy one for Gipsy. As he had confidently expected, there was a brisk demand amongst the younger fraternity over the portrait of Miss Netta Montgomery. She fell to Gammon, who had been a particular victim to her charms, but not until Gipsy had disposed of nearly eighty tickets. An almost equal popularity was enjoyed by the transformed Bronze Horse, whilst the mothers of the camp took a vivid, if morbid, interest in the picture of the Red House, where the murder had been committed.

Gipsy raked the money in and posed as a benefactor at the same time. His enterprise and public spirit enabled the settlement to gratify a natural passion for the best in art. But for Gipsy these elevating objects would never have found their way here at all. Later on, in the seclusion of his hut, Gipsy counted his spoils.

"'Ave some baccy," he suggested hospitably to Mitchell. "Fill your pouch... Fourteen pounds seventeen and sixpence. Dunnow where the tanner came from. When the bailiffs come, I shall be able to talk to 'em now. Still—"

Gipsy's face clouded thoughtfully. He had earned all that his own bright and particular seemed a pity to waste it on mere publishers. Many a beautiful spree, many a lurid Saturday night shone from that pile of silver on the table.

"Seems a pity, don't it?" Mitchell suggested, watching his companion's thoughts.

"Pity!" Gipsy snorted. "It's what them drapers call an appallin' sacrifice. Still, it ain't me what's goin' to pay for the Compendium. An' yet—"

Gipsy pulled at his pipe thoughtfully. He sat there under the lamplight after Mitchell had departed, thinking the matter out. The novelist in the rough had got his hero out of a tight place; but in all properly appointed romances the hero not only escapes from imminent peril in the deadly breach, but is in honour bound to score over the miscreants who, for the time being, have triumphed. And Gipsy practically had not scored at all. Being his own hero, he felt it. Thoughtfully he took an envelope and addressed it to the publishers of the Compendium. Then he produced a sheet of paper and laboriously proceeded to write a letter. It was a slow and painful process, but in the end it seemed satisfactory :—

Box 171, P.O.

Water Company's Scheme,

Cwm Valley.

Sirs,

A few friends of Mr Ercules Gipsy wot's left the valley and no address is desirous of seein wot I can do in the matter of the Compendium. Which never ought to have been sent in the way it was. Out of respec to the memory of Mr Gipsy and if he could be allode to come back we'll between us send you four pound ["five" scratched carefully out] and no questions ask. This to clear off all back pay and put the time sheet right. A answer from you by the next post saying as this is all right money will be sent.

Yours respeckfully for 6 of us,

Jon Price.

Gipsy duly despatched his letter, comfortable with the assurance that there were some scores of John Prices in the settlement. For the next day or two he was dreamy and preoccupied. The third day brought a letter from the publishers of the Compendium, offering, with large magnanimity, to cancel the debt and all proceedings on receipt of five pounds, coupled with a rider to the effect that the money must be received by return of post. It cost Gipsy a pang to part with his five sovereigns, but there was sweet consolation in the fact that he had the Compendium, plus nearly ten pounds, and that without the outlay of a single penny of his own money. Thus do the heroes of romances score over mere mundane and less brilliant creatures.

Gipsy ran into the arms of Mitchell as he came from the post-office.

"Suppose you had to pay?" he asked.

"Suppose I didn't," Gipsy said thoughtfully. "I wrote a letter to the Compendium bloke sayin' as a few pals of Gipsy's 'ud like to—what you call it?—compromise. And they took five bloomin' quid. And I've just posted the brass. What do you think of that?"

Mitchell shook his head admiringly and passed on. Gipsy returned thoughtfully to his hut. The gay volumes of the Compendium seemed to smile down at him. He could think with toleration of the words of the wily little book-agent now.

"After all," he muttered—"after all, there's something in a liberal education."

THE little man with the snaky hair and deep-set eyes, sitting in the corner of the canteen, was known to all and sundry as "Gipsy." To the uninitiated this title, of course, had no geographical significance. To the casual, Gipsy was no more than a foreman ganger employed upon the great new water system at Penguilt; but there were men working there who could have told you that, in the freemasonry of the craft, the name of Gipsy carried from the Golden Gate to the Yukon Valley, and from the Nile to the Amazon. The little man sitting there, drinking his beer and smoking something particularly painful in the way of a cigarette, was Bohemian to his blunt finger-tips. He would have resented the suggestion that he was anything but an Englishman, though his looks belied him, and the Zingari in his blood drifted him from time to time all over the world. He was a master of argot in many languages; he had its slang and its illusive profanities on the tip of his tongue. Wherever the spade and the drill and the dynamite cartridge carried in the making of the world's highways, you could have put Gipsy down over a gang of men, be they white or black, orange or copper-coloured, and he would have handled them, too, and they would have known that they had a man over them from the word "Go!"

Gipsy, therefore, was a celebrity in his way. Great captains of industry knew him by name; they encountered him from China to Peru, so that he formed the link between East and West, and in a way was proud of it. Gipsy might have made money had he been less generous and not quite so romantic. For there was a strong vein of sentiment in the little man, who, had he been blessed with the advantage of education, would most assuredly have made a name for himself as a dramatist. He was a Sardou without power of expression, a Shakespeare in embryo, lacking the gift of the written word. As a matter of fact, he could hardly write his own name; but he could plot and plan, and many a comedy had been played in the Settlement which had not been rehearsed from the written scrip.

There was nothing that Gipsy liked better than the weaving of romances in which he played the leading part. And to his credit, be it said, most of them were founded upon fact. There were those amongst the tough brotherhood of the pick and shovel who implicitly believed all that Gipsy said, and on the other hand were ranged the cynical, who spoke of him frankly and luridly as a liar. But this is essentially a penalty of greatness, and touched Gipsy not at all. In one respect, however, even the most doubting regarded Gipsy with veneration: he was by far the most gifted and accomplished poacher amongst the ten thousand odd gathered together there amongst the mighty reservoirs carved out of the hillsides of Penguilt. Everybody knew this, and Gipsy was flattered accordingly. There were trout and salmon there, partridges and pheasants, and grouse, too, on the upper moors. Gipsy looked after himself all right, and the mess-mates in his hut, but to the rest of them he was profoundly and almost eccentrically modest.

He talked fast enough—in fact, he was always talking—but not about the best way to circumvent the wily salmon or the elusive trout, and the more silent Gipsy was on these points, the more sure were his satellites when he was planning some wily campaign on his lordship's preserves. He was talking now, telling one of his stories in which he was playing the hero, as usual. It was hard on the time when Gipsy usually embarked upon his third pint of beer, and his mood had reached the softened and sentimental stage.

"I am tellin' you no word of a lie, mates," he said. "There is a poet as I once 'eard on as said somethin' about flowers what was meant to blush unseen. I read that bit in a paper as come my way about fifteen year ago, when we was makin' that dam for the Russian Government out in Manchuria. Remember it, Joe?"

The man addressed as Joe nodded over his pipe. One of the beauties of Gipsy's stories was their verisimilitude. He rarely embarked upon a romance without the presence of some witness who could speak geographically. Therefore Joe nodded.

"I made a tidy bit o' money them times," Gipsy went on. "I couldn't well spend it, and it began to pile up, till I'd sent 'ome nigh on seven 'undred quid in about three year. And then I begins to ask myself what I should do with it. Not but what I'd got an idea in me 'ead. Fust-rate idea for a play it were, too. It was all about a gel—a little gel as I picked up on them plains of Manchuria. She wasn't nothin' more than a peasant's kid as 'ad been abandoned by 'er father and mother in consequence of a bit of a scrap what 'ad taken place between some Manchus and a tribe of Chinese pirates. Found 'er in a burnin' 'ut, I did, wrapped up in a bit o' blanket. Funny thing, but that kid took to me from the first. And blowed if I 'adn't got my 'eroin' fust 'and!"

"Lor, what a liar it is!" an admiring voice came from the background. "But go on, Gipsy, cough it up."

"I was about to do so," Gipsy said, with some dignity. "And if you don't believe as that scrap took place, ask ole Joe 'ere."

Joe gave the desired assurance, and Gipsy resumed.

"As I was a-sayin'," he went on, "there was my 'eroin' all ready-made. What did I do with 'er? Why, adopted 'er, of course! I 'ad to put off the play, but that didn't matter. Now, mind, I'd got a tidy bit o' money put by, which I was pretty certain to do in fust time we got back to England.

So I goes to one of our engineers what 'ad got a missus and kids out yonder, and I puts it afore 'im plain. I tells 'im as that little nipper, what might 'ave been about four year old, was goin' to be my heiress."

A burst of laughter followed, but Gipsy went on gravely.

"I wanted that kid sent over to England to eddicate. And our engineer 'e says: 'Good iron!' Says that I should only make a fool of meself if I kept the money. So I passes it all over to 'im, and 'e agrees to spend it at the rate of about a 'undred quid a year on the kiddie's eddication, and, what's more, 'e does it. Now she is a lady, a real proper lady, as swanks about in 'er silks and satins, and mixes regular with the nobs. Fit to go into any 'ouse in the kingdom, she is. They tells me at the present time as she's governess to the daughters of a bloomin' earl. Lives in the 'ouse with them, and is regular one of the family. She's dark and she's beautiful and she's 'aughty, and I ain't sure as a lot more earls ain't on their bended knees askin' 'er to marry them."

"Ain't 'e a knock-out?" a voice in the tobacco fog said, appealing. "Ain't 'e better than a Sunday piper? Ever stay with 'er, Gipsy? Ever put in a week-end at one of them castles?"

"We 'ave never met," Gipsy said loftily. "My adopted daughter 'as not seen 'er toil-worn parent. Probably she never will. Who am I that I should stand in the girl's way? Why should I drag 'er down to my sordid level? It's what some newspapers call a perlite fiction that I am dead, and that in future the beautiful orphan will 'ave to rely upon 'erself for 'er daily bread."

"She might be able to lend yer a bit," a practical member of the audience suggested. "If she gets spliced to one o' them dooks you spoke of, she ought to be good for a couple o' quid a week. But it's all lies! We are a set o' fools to listen to it all. And yet, when you begins to tell one o' these 'ere stories o' yours, I am never quite sure whether you are a blithering liar or not!"

Gipsy smiled with the air of a man who is the recipient of some graceful and well-chosen compliment. He knew that he was holding his audience in spite of themselves, and these cynical lapses into common-sense were really attributes to his powers. One man, a little less easily moved than the rest, jeered openly.

"Wery good," he said. "But yer story don't go far enough, mate. There's few chaps in this camp what knows the Surrey Theatre and the old Britannia better'n me. I've seen that 'eroin' o' yours 'undreds o' times. Why, you're the bloke as she finds dying in a work'ouse, or drags into the marble 'alls by the scruff o' the neck on a snowy Christmas Eve! She calls you 'er benefactor, and 'er husband, the dook, shakes you by the 'and and fills you up with port wine and roast goose. So far it's all right, Gipsy. But you've got to 'ave somethin' as proves your indemnity."

"That proves my what?" Gipsy asked. "Lor, what an ignorant set o' blokes you are! Meanin' my identity, I suppose?"

"Well, that's just wot I said," replied the other man diplomatically. "You've got to 'ave a mark o' some sort—a wound as you got when you rescued 'er from the fire, or perhaps a photograph."

Gipsy smiled in a superior fashion.

"I thanks the right honerable gentleman for makin' the remark," he said. "He's been good enough to call me a liar. Well, I can't show no wounds—that's wot they calls scars in the play—but the photograph's all right. 'Ere, wot price this?"

From a capacious inner pocket Gipsy produced a stiff leather case, from which he took a framed photograph. It represented a girl on the eve of womanhood, a tall dark girl in evening-dress, with a face serenely beautiful and faintly smiling. She seemed typically one of the upper classes, essentially to the manner born, with that elusive suggestion of superiority that makes the thing which, for want of a better word, they call a lady. For a moment Gipsy regarded it with a certain reverent affection. Grudgingly he released it from his horny thumb and forefinger and passed it round amongst his mates.

"There yer are," he said defiantly, "that's the lidy. And if anybody 'ere calls 'er anythin' else, I'll push his fice in!"

There was no occasion for the threat, for the spirit of cynicism had vanished the moment that Gipsy had crowned his story with this startling piece of circumstantial evidence. Even the man in the far corner was silent and almost inclined to believe.

"Where's the lidy now?" a respectful voice asked.

"I dunno," Gipsy said shortly. "I got this photograph about two years ago, and I ain't made no inquiries since. I ain't goin' to stand in the girl's way. Some of these days there'll be a duchess or a countess as'll never know as she owes 'er 'appiness to a common ole bloke named Gipsy."

With these dignified words, Gipsy collected his photograph and walked slowly and sorrowfully out into the darkness. He conveyed a subtle impression that deep and tender chords had been touched, that he was a strong, silent man who wished to hide the full measure of his grief from the eyes of a cold and unsympathetic world.