The history of famous detectives, imaginary and otherwise, has frequently been written, but the history of a famous criminal—never.

This is a bold statement, but a true one all the same. The most notorious of rascals know that sooner or later they will be found out, and therefore they plan their lives accordingly. But they are always found out in the end. And yet there must be many colossal rascals who have lived and died apparently in the odour of sanctity. Such a character would be quite new to fiction, and herein I propose to attempt the history of the Sherlock Holmes of malefactors.

Given a rascal with the intellect of the famous creation in question, and detection would be reduced to a vanishing point. It is the intention of the writer to set down here some of the wonderful adventures that befell Felix Gryde in the course of his remarkable career.

* * * * *

EVERY schoolboy knows the history of the rise and progress of the Kingdom of Lystria. Forty years ago a clutch of small independent states in South-Eastern Europe, the lapse of less than half a century had produced one of the most powerful combinations on the face of the universe. As everybody also knows, this result was produced by the genius of a quartette who in their time made more history than falls to the lot of the most stormy century. For years they kept the makers of atlases busy keeping pace with the virile growth of Lystria.

But time brings everything in due course; the aged makers of Empire laid aside the pen and the sword, and death came at length to the greatest of the four, even unto Rudolph Caesar, whom men called Emperor of Lystria. Wires, red-hot with the burden of the message, flashed the news to the four corners of the earth; column after column of glowing obituary were thrown together by perspiring "comps"; Caesar's virtues were trumpeted far and wide. It was the last sensation he was like to make.

Meanwhile Mantua, the capital of Lystria, had arranged for a month of extravagant funeral pomp and circumstance fitting the occasion. The papers teemed with the sombre details. The laying in state—a matter of eight days— was to be a kind of glorified Lyceum stage effect. The cold Caesarian clay was to be given over to no vile earthworm, but had been embalmed without delay.

All this pageant Felix Gryde had read of in the seclusion of his London lodgings, in Barton Street. The florid extravagance of the Telegraph awoke in him a vein of poetic heroism—daring with something Homeric in it. The slight, quiet-looking man with the pale features and mild blue eyes did not look unlike the popular conception of a minor poet, save for the fact that Gryde was clean of garb and kept his hair cut.

A smile trembled about the corners of his sensitive mouth.

"Here is a chance," he murmured, "for a really clever soldier of fortune like myself to distinguish himself. I can see in this the elements of the most remarkable and daring crime in the history of matters predatory. Here is a handful of glorified dust guarded night and day by the flower of an army. The stage is brilliantly lighted, passionate pilgrims are constantly coming and going. What a thing it would be to steal that body and hold it up to the ransom of a nation."

Gryde sat thinking this over until the roar of London's traffic sank to a sulky whisper. He might have been asleep, dead, in his chair. Then he rose briskly, lighted a cigarette, and turned up the lamp again. He rang the bell, and a servant entered. The man waited for his master's orders.

"Lye," said Gryde, "I am going away for a day or two. You will get everything ready for me to leave Charing Cross by the nine train in the morning. You will get a letter from Paris saying when I shall return."

The man bowed silently and went out. Then Gryde retired to bed and slept like a child till the morning. Before nightfall he found himself speeding along in a certain continental express towards his destination. Through the blackness of the next night, looking out of the window of the carriage, he could see a faint saffron arc of flame beating down from the sky, the reflection of the countless points of fire in the city of mourning. Gryde's destination was reached, for Mantua was at hand. The train drew into the station.

"One against half a million," Gryde muttered: "a pin's point to a square of bayonets. A good thing I speak the language perfectly."

He took up his handbag, and plunged unheeded into the heart of the city.

NOTHING more sombre and at the hangings same time more magnificent in the way of a spectacle had ever been witnessed than the ceremonial daily taking place in the chancel of the cathedral at Mantua.

Every window in that immense structure had been darkened by crape the Corinthian columns were draped in the trappings of woe, dark cerements which only served to show up the genius of carver and architect.

The cathedral was faintly illuminated by thousands of candles. The body of the dead monarch lay upon a bare wood bier which made a vivid contrast to the velvet trappings, the piled-up pyramids of flowers, and the brilliant uniforms of the surrounding guards.

These latter, men picked for their fine physique, stood almost motionless around the bier. All down the nave a double line of them were drawn up, and every faithful subject had to pass between them on the way to pay a last tribute of respect to the dead monarch.

They came literally in their thousands, quiet, subdued, and tearful. It was easy for a stranger to mingle with the throng and notice everything: there were dusky corners and quaint, deep oaken stalls where those who cared could hide and watch the progress of the pageant.

Two men had crept behind the gorgeous line of guards into one of these. They had no fear of being detected, lost as they were in the gloom. An additional security was lent by the nebulous wreath of smoke rising from thousands of candles. The features of one of the men were pale, his build as slight; he had deep blue eyes and a sensitive mouth. As to his companion, it matters very little. He was merely the confederate necessary to the carrying out of Gryde's scheme. Gryde did not require his tools to think: that part of the business he always looked to himself. All he wanted was one to faithfully carry out his instructions, to act swiftly, and to possess indomitable courage. There was not a town in Europe where Gryde could not lay his hand upon a score such. For the rest this man passed under the name of Paul Fort.

"A devil of an undertaking," muttered the latter.

"Nothing of the kind," Gryde replied: "the thing is absurdly simple. I admit that on the face of it the stealing of an Emperor from under the eyes of his people is a difficult matter. You shall see. The easiest conjuring tricks always seem the most astounding. From our point of view, £100,000 lies waiting on those bare boards for us. Some people may call those the ashes of departed Caesar—they represent a carcase which, will prove a valuable market commodity."

"But you must get your carcase first."

"I am going to. How? By a conjuring trick. I shall spirit the departed Caesar right from under the eyes of his afflicted people. When? This very evening when the crowd will be at its thickest. Do you see that grating right behind the bier? Well, that communicates with the vaults. The custodian of the vaults will sleep very soundly when he retires this evening, and he will temporarily lose possession of his keys. Not that he will be any wiser for that. It was very thoughtful indeed for the architect who built this place to prepare and execute so minute a plan of the building. I have been studying it very carefully in the library here. This grating now supplies the chancel with hot air. You have already gathered that this evening I shall have the keys of the vaults. Now you hear what to do. Be good enough to repeat your instructions."

"I am to come here alone," Fort said, "about ten o'clock. Then I am to make my way up into the gallery, the key of which you have given me, and I am to remain out of sight till you give a certain signal. Then one by one, at intervals of half a minute, I am to drop those big glass marbles you gave me into the chancel and amongst the congregation. Then I am to leave by the leads, climb down the lightning-conductor at the end of the Chapel of Our Lady, and join you at our lodgings without delay."

"Good," Gryde muttered. "There is no more to be said. Go."

* * * * *

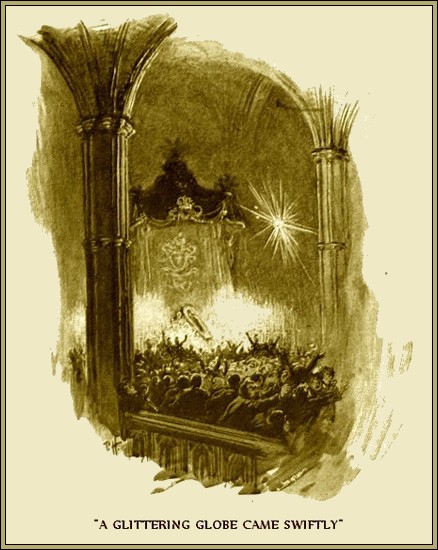

It was the sixth evening of the lying in state and the popular holiday in Mantua. The great cathedral was absolutely packed with people. So great was the crush that the police responsible for order looked grave and anxious. Still the occasion was one of gloom and seemliness, and the procession moved slowly. Even up to the bier the crowd was so thick that only here and there were the scarlet and gold uniforms of the guards picked out vividly against the dense black.

Over the tread of restless feet and the sound of smothered mourning rose the wail of the organ chanting dirges for the departed. The candles guttered and smoked, as the waves of hot air drifted over them. The very solemnity of the place carried awe into the hearts of the spectators. The sudden bang and jar of a falling chair came with a startling echo.

A second later and a glittering globe came swiftly towards the floor. It might have been one of the golden points of the great corona there. It came speeding down like an arrow from a bow, and then suddenly faded into nothingness.

As it did so a hurricane blast seemed to fill the cathedral, a tremendous explosion followed, the vast audience reeled and rocked as if from the shock of a cavalry charge. Ere they could recover from the surprise, another explosion followed.

The piping scream from a woman's throat rang into the roof. With one accord the audience turned a sea of grey faces towards the big west doors. It only wanted the pressure of a child's hand now to set the avalanche in motion. Another and a louder roar followed, there came a roaring wind, the countless candles flared and hissed, and then came the new horror of darkness.

"For Heaven's sake, the doors!" rang out a voice familiar enough to every soldier in Mantua. "Don't rush there; the danger cannot be so very great."

The stern command seemed to hold, the human sheep. As the doors rolled back, the points of flame from the street lamps twinkled through the opening. The black wave rolled steadily on, and a fearful disaster was averted. In a few moments, save for the guard, the cathedral was deserted. Meanwhile the explosions appeared to have ceased. The guard struggled up to the chancel, and after a time the candles were lighted again. Strange to say, not a single human form lay on the marble floor.

"What could it have been?" muttered an officer.

"Nihilists," replied the colonel of the guard. "A foolish display, and intended for show alone. Still, the disaster might have been a terrible one."

The young lieutenant said nothing. His limp hand fell from the waxed point of his moustache, his eyes were fixed upon the bier. The colonel had seen fright before, and, being a brave man, respected it.

"What is the matter?" he asked. The lieutenant found his voice at last.,

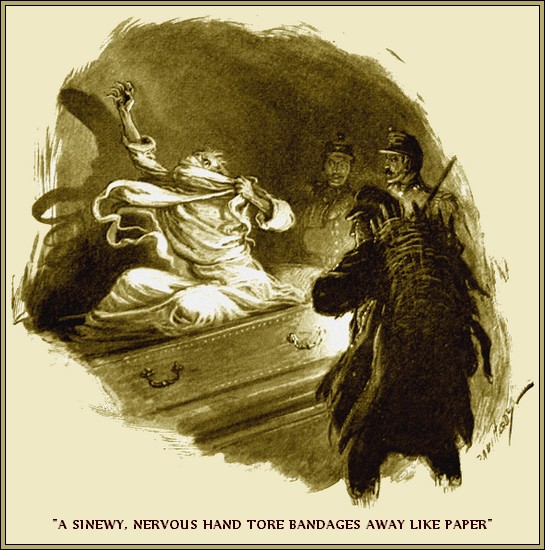

"Look there," he said in a frozen whisper. "The Emperor! The scoundrels have been successful. The bier is empty. Why do such wretches live?"

An oath crept from under the colonel's grizzled beard. The shaking of his hand alone betrayed the emotion that he felt.

"My God!" he murmured. "I had died rather than this had happened."

IT would be idle to attempt to describe the sensation created by the disappearance of the late Emperor of Lystria. Europe had not been so thrilled since the assassination of a one time Czar of Russia. The daily papers teemed with the latest news, and rumours current as to the reasons for the outrage.

Naturally the plot was laid at the door of the Nihilists, and countless arrests were made. But search high and low as they could, no trace of the body could be found. In vain a free pardon was offered to anyone connected with the crime who would come forward and make confession, in vain was a large reward offered.

Count Desartes, Chief Commissioner of Police, and his subordinates were puzzled. They had absolutely no proof whatever to go upon. Nothing came till the third day, when there arrived a letter bearing the Mantua postmark. It was unsigned, undated and unheaded, and written on a long slip torn from the margin of a newspaper. It was simply sealed and addressed and came minus an envelope. As for the letter itself, it was printed by hand in small capitals throughout. It ran thus:

"YOUR EMPEROR IS SAFE AND UNMOLESTED. REST ASSURED THAT THE BODY OF SO BRAVE AND GOOD A MAN IS NOT LIKELY TO RECEIVE ANY INDIGNITY AT OUR HANDS. THE RECOVERY OF THE REMAINS IS A MERE MATTER OF MONEY. ONE HUNDRED THOUSAND GOLD CROWNS IS THE RANSOM DEMANDED, AND NOTHING LESS WILL BE TAKEN. OTHERWISE RUDOLPH CAESAR IS NEVER LIKELY TO REST WITH HIS FATHERS. COMMUNICATIONS IN ANSWER TO THIS WILL ALONE BE ACCEPTED IN THE WAY OF AN ADVERTISEMENT IN THE COLUMNS OF THE ZEITUNG. THEY MUST BE HEADED TO 'CORONET' ONLY."

For a long time did Desartes ponder over this strange letter. If the bona fides of the rascals could be assured, the money would have to be paid, provided always that strategy resulted in failure.

"In any case this letter must be answered," the Count remarked to Wrangel, his next in command. "Let it be announced that we accept the terms, and shall be prepared to pay over the money if we are satisfied that the object we seek will be obtained. See to it at once."

The result of this now brought another letter from the scoundrels. The money difficulty still barred the way. The possession of so large a sum of money in cash was extremely likely to lead to detection. The safeguards proposed by the writer of the letter were stringent. And unless these were complied with, no further communications, could be exchanged.

After a delay of six days, and many fruitless letters, a way out of the difficulty was hit upon. The suggestion was so simple, not to say childish, that Desartes smiled as he perused the ultimatum He might have known that with such men to deal with the simplest and most apparently straightforward plan could really conceal a profundity of cunning and prudence.

To all practical purposes Gryde placed himself unreservedly in Desartes' hands. He assumed that the latter would act honourably towards him: that a secret meeting would take place and the money handed over, when the hiding-place of the late head of the Caesars would be disclosed.

"THE PLACE OF MEETING," Gryde wrote, "WILL BE AN APPARENTLY DESERTED HOUSE IN THE UNTERSTRASSE NO 14. ON FRIDAY NEXT YOUR MESSENGER WILL GET FROM THE BANK IN THE SAME STREET THE NECESSARY MONEY IN GOLD. WE SHALL SEE THAT HE RECEIVES THIS, AND HE WILL PROCEED WITH THE SAME TO NO. 14 IN A CAB. HE WILL KNOCK AT THE DOOR, WHEN A MAN IN LIVERY WILL RECEIVE HIM AND HELP HIM TO CARRY THE GOLD TO A ROOM ON THE GROUND FLOOR. THIS SERVANT WILL BE AN INNOCENT DUPE PROCURED FOR THE OCCASION.

"ALL THIS MUST TAKE PLACE EXACTLY AT FOUR O'CLOCK. IF THE THING IS PROPERLY CARRIED OUT AND NO TREACHERY ATTEMPTED, THE FIVE O'CLOCK POST WILL CONVEY TO COUNT DESARTES THE HIDING-PLACE OF THE DECEASED MONARCH. TO GET AT THE BODY AND RESTORE IT TO ITS PLACE WILL TAKE SOME TIME. ALL THIS TIME THE MESSENGER WITH THE MONEY WILL REMAIN IN NO. 14, BUT AT SEVEN O'CLOCK IN THE EVENING HE WILL BE FREE TO DEPART. IF HE ATTEMPTS TO DO SO BEFORE, HIS HOURS ARE NUMBERED. THIS IS FINAL."

Desartes smiled as he read. He advertised in the Zeitung that all these matters should be carried out faithfully, and up to a certain point he meant all he said.

"We will do it, Wrangel," he said. "The gold shall be procured, and you shall convey the same to No. 14. It shall be the real red gold, and you shall remain there till seven as arranged. Meanwhile a perfect cordon of police shall surround the house, and when the time comes we will take the place and the miscreants as well. This will, of course, be subsequent to the discovery of the Emperor's body. As to the rest I will leave all the arrangements in your very capable hands."

"Your Excellency may be perfectly assured," Wrangel murmured. Whereupon Desartes went tranquilly off to dinner.

* * * * *

It was one o'clock on the eventful Friday, and Gryde was seated in his room awaiting the arrival of Fort. On the table before which he was seated lay a large number of sealed and stamped letters, and a champagne bottle nearly full into which one of those patent screw taps had been inserted. There was a peculiar star on the side of the bottle, suggesting that the same had nearly perished by contact with another hard body, and on the top of the star a spot of wax. But as the champagne exported to Lystria is dipped in wax to the shoulder of the bottle, the fact was not likely to cause attention.

A minute or two later and Fort entered.

"I'm glad you've come," said Gryde.

"All the same, there is nothing further to report. What you have to do is precisely as arranged. You will go to No. 14 at five o'clock precisely and there await the messenger from the bank. Make him open the box and show you the gold, so as to be certain of its being genuine. At a few minutes before seven I will come also—"

"And if the messenger does not arrive?" Fort suggested.

"In that case you will know that treachery is afloat. Therefore you will consult your own safety by staying where you are. Give me the agreed signal from the window and I will put my plan into execution for setting you at liberty. And mind, you are to remain perdu till a quarter to five."

Fort nodded. He was a little puzzled, but at the same time he had a doglike faith in his leader. He would have faced anything for the latter.

"I'll do exactly as you say," he said.

"Good. Now we will have one glass of champagne together, and then I shall turn you out, as I have much to do."

Gryde pressed the lever and a glass of champagne foamed out. As he filled a second glass his forefinger rested on the star on the bottle. The second glass he handed to Fort, and took down the first at one pull.

"Enough for the present," he said. "Now go."

Punctually at four o'clock—exactly an hour before the time arranged for Fort's arrival, strange to say—Wrangel drove up to No. 14 with his burden. As he rang the bell a man replied, and assisted Wrangel to convey his heavy load to a room at the back, then bowed and disappeared.

In the hall Gryde awaited him. None could have recognised him in his disguise.

"You may go now," he said; "my friend has arrived. Here is a gold piece for you."

Scarcely had the door closed behind the dupe when Gryde crept to the room where Wrangel awaited somebody. His back was to Gryde. The latter carried in his hand the weapon somewhat humorously termed a life-preserver. One blow straight and swift under the lobe of the right ear and Wrangel dropped in his tracks like a bullock. In less time than it takes to tell he was gagged and bound and literally rolled into the cellar.

For the next three-quarters of an hour Gryde was busy. He had to transfer the gold to a number of small cases marked "Cycle Bearings" and consigned to a certain house in the neighbourhood of Fenchurch Street, London. The back of the house opened upon a narrow, dingy lane faced by a blank wall of a factory. As Gryde got the last of his cases into the lane a waggon lumbered along.

"Here," Gryde cried, "you're late, you know. Get these boxes aboard. As I'm going the same way I'll ride with you to the station."

The driver made no objection to a fellow working man accompanying him. And thus it came about that Gryde personally superintended the dispatch of his treasure per passenger train, and a few minutes after Fort's arrival at No. 14 was on his way to the frontier in the same train as the precious metal. A workman lounged in the corner of a third-class carriage. Who would have identified him as being the author of the most sensational crime known in modern Europe?

Meanwhile Fort waited and waited doggedly. A clock somewhere struck seven. At the same moment the front door opened and heavy feet tramped in. Fort was on the alert in an instant. That he had been betrayed never occurred to the brave ruffian for a moment.

He knew that he would have to fight for his life. He set his teeth hard and faced the ring of police who had sprung upon him. He had no weapon. He sprang forward with the courage and force of despair. An instant later he was struggling and fighting with the strength of a tiger.

Then his strength seemed suddenly to relax, he fell back helplessly into the arms of one of his captors. A blue tinge came over his face; the side of his mouth drew up in a horribly grotesque manner. A shudder and shiver, and Fort had escaped. He was dead.

Almost before the police could realise what had happened, Desartes came, hurrying in. His air was elated. His eyes sparkled with triumph.

"The rascals told the truth," he exclaimed. "The Emperor has been found concealed in a stone coffin in the vaults below the cathedral. We had a long search for the body. The miscreants removed it by the way of the grating behind the bier. You have the man, and you have recovered the money as well."

One of the police explained the new feature of the drama. A search was made, but no gold could be found, nothing but Wrangel in the cellar groaning pitifully and anathematising what had happened. But gold there was none, and to this day the hiding-place of the same is wrapped in mystery. That they had obtained possession of the leading villain in the cast, Desartes never doubted. And he had escaped them.

* * * * *

And in the fulness of time Gryde read the "solution" of the mystery comfortably in London. He had his money, he had come out of the danger unscathed. He had coolly and in cold blood betrayed his colleague to save himself, for the champagne had been poisoned to make assurance doubly sure.

"And how ridiculously easy it was after all," the master scoundrel muttered as he flung his paper aside. "What a success, too, were those gelatine bombs, exploded by the force of their fall. Neat and not destructive. Police! I could rob the Bank of England itself, and trace the crime to Scotland Yard. Maybe I will some day, before I settle down to growing orchids and courting the gods of the bourgeoisie."

THE Mahrajah of Curriebad was for the present located in Jermyn Street. On the following day he was commanded to Windsor for the regulation dinner; in the meantime he had practically chartered the hotel.

Morals the Mahrajah possessed none—they would have been perfectly superfluous in any case—but money he had in plenty. For this reason the India Office people were fond of him.

At the present moment they were desirous of getting something out of their distinguished visitor: more territory, more men, an extra sack of diamonds; and the Windsor interview was expected to clinch the business. Meantime the dusky potentate winked the other eye. He fully appreciated the meaning of the phrase. He had a private music-hall of his own at Curriebad.

Incidentally it may be mentioned that a more consummate rascal than Nana Rau never drew the breath of life through shifty lips. Of his early career people knew but little. They noted that he spoke excellent English, and that his knowledge of the Stud-Book was not of a perfunctory character.

Nana Rau had just dined alone. As he lighted his second cigarette a servant entered with the announcement that a visitor waited below. With rare graciousness the Prince ordered the gentleman to be conveyed into his presence.

He came, he bowed, he closed the door behind him.

"My name is Wilfred Vaughan, your Highness," he said.

The potentate nodded. The stranger prepossessed him, he was so exquisitely dressed.

"Sit down, Mr. Vaughan," he said, "and take a cigarette. Then, if you please, you can proceed to unfold your business."

"I am obliged to you. Ah, what it is to be an Eastern Potentate! Now, it would be impossible for me to get cigarettes like these. My good friend, it is possible that you have forgotten the old Oxford days?"

"That is a long time ago—twenty years," Nana Rau replied, uneasily.

He felt uneasy, too. The India Office would have been surprised to hear that Nana Rau had ever been at Oxford. But then he was not Nana Rau at all, and four good lives stood between him and the sacks of Curriebad diamonds. Also incidents had happened at Oxford which it was expedient should remain buried in the silent tomb with the flowers blooming atop, and no white stone to mark their memory. Even now, were those stories told, Nana Rau knew that his connection with the throne of Curriebad would come to an abrupt conclusion.

"Twenty years are nothing," Vaughan said sententiously, "and my memory is good."

"You are Vaughan of 'The House,' of course. What can you remember?"

"Well, for instance," Vaughan smiled, "there was a pretty tobacconist's assistant: she was found dead under very suspicious circumstances. About the same time an Indian student at Christ Church disappeared. The police were anxious to find him—very anxious. Strange to say he was never heard of again; and, until to-day, I haven't seen him since."

Nana Rau recovered his equanimity. His thin lips ceased to twitch. He felt that this was a mere matter of money.

"Old chap," he said quite cordially, "what's the figure?"

"You always were a sensible man," Vaughan replied. "Never any dashed Oriental poetry about you. All the same, there is no figure—in money signs, that is."

"Then what the deuce do you want?"

"That I can hardly go into in detail. Let us speak plainly. I've got the whip hand of you: a few words from me and your interest in the sovereign lord and ruler business stops. You recognise that, of course. That I require something is obvious. I want you to stay away from Windsor to-morrow."

Nana Rau smiled at the suggestion.

"Absurd," he said; "you know I dare not do so."

"Under ordinary circumstances, no. But these are not ordinary circumstances. You are merely going semi-officially. There will be no State fuss; you will dine at the Castle, and return here next morning. What is intended to take place yonder you know as well as I do."

"I don't want to go. It's certain to be deuced slow. And if you can only show me some way out of the difficulty without compromising myself--"

"Of course I have my plans prepared," Vaughan interrupted.

"You don't leave Paddington till a train somewhere about six. Here is my card with my address. My place is out at Epsom. Come out there and lunch with me to-morrow, and bring your suite with you, baggage and all, and if we can't come to terms, my carriage shall take you to Paddington."

"I have only two chaps with me besides my cook," said the Prince.

"Good. So much the better. Then you will come?"

"Well, there is no harm in that," said Nana Rau. "I will."

A few minutes later Wilfred Vaughan, alias Felix Gryde, was placidly walking along Piccadilly. He turned into the Café Soyer, where the other parties to the conspiracy were awaiting him and dinner. They were the tools to be used and to be discarded when the curtain fell.

"It's all right," Gryde proceeded to explain over the bisque. "I told you Nana Rau was the same man I used to be at Oxford with twenty years ago. I spotted him at Ascot, and I never forget a face. Nana was terribly frightened, and, indeed, it was no idle boast that I could bring about his ruin."

"Will he come?" asked tht second conspirator.

"And will the original plan stand?" asked the third.

"Exactly as arranged. You will look after all the details, as I shall be very busy till luncheon time to-morrow. You will see that the cold luncheon is properly laid out by the local caterer, and pay for it. Then the keys must be packed up so as to be posted to the landlord's agent directly we leave the house. Let the carriage be ordered for 3.30 prompt, and pay the liveryman for that also. Let it be understood that we have just taken the house for six months furnished— which is, indeed, the fact—and go to a registry office to inquire about servants. Order a dozen, and say the housekeeper will call to interview them on a certain day. Each of us, till the time for changing comes, retains his present disguise."

As a "make-up" artist Gryde had no equal. Several society acquaintances there passed him without a s:gn of recognition.

"That's all very well," suggested one of the lieutenants; "but suppose any of the Castle people happen to have seen Nana Rau?"

"Which they haven't done," said Gryde. "I have made the most minute inquiries on this head. Besides, one Eastern Potentate is as like another as two peas when he is in his full war paint. It's any money nobody yonder speaks the language, and if they do I shall make it my pleasure to stick to English. As you have both presumably been in England before, you can do the same. You have carefully studied the plans of the apartments I gave to you?"

The others protested that they had.

"Very good," Gryde concluded; "in that case there is no more to be said. We ought to find enough within easy reach yonder to reward us for all our trouble. And the servants of the sovereign shall assist us in getting it away. I hope you won't find it altogether too slow."

Gryde settled the score and they rose to depart. In the street they separated, and each took a different way. Then they went to bed early and virtuously as befit men who have before them matters of importance on the morrow. On the whole they slept better than Nana Rau, Mahrajah of Curriebad.

IT WAS with considerable misgivings that Nana Rau drove with two dusky assistants down to Epsom the following morning.

With him was all his baggage, a formidable-looking amount for a night out; but then the dazzling splendour of Eastern attire cannot be measured by Western sartorial restrictions. These big trunks contained the full war paint which Nana Rau and suite intended to don after luncheon, and ere proceeding to Windsor.

One thing Nana Rau was fully resolved upon. Nothing should induce him to play into "Vaughan's" hands unless the latter could provide him with a proper way out of the difficulty. It was only natural that the Prince should desire to protect himself, and nothing short of being able to show that he was the innocent victim of a vile conspiracy would satisfy him.

The Indians reached Vaughan's hospitable mansion at length and were met at the door by that individual himself.

"I am afraid I shall have to request you to dispense with a deal of ceremony," he said. "The fact is, this place has been let furnished for about a year, and my late tenants only turned out of it last week, and thus we are terribly short of servants. These footmen don't seem able to do anything without a lot of women to help them."

Vaughan, or Gryde rather, rang the bell violently, and presently a pair of men-servants appeared breathlessly. They were a fine-looking pair of men, and their livery left nothing to be desired. The astute reader will have little difficulty in guessing who these footmen were.

"Whatever have you fellows been doing?" Gryde demanded.

"Please, sir," replied one, in the purest of Cockney accents, "it's all along of the new cook, which she's drunk--"

Gryde waved these details aside.

"I desire to know nothing of these matters," he replied. "Take the Prince up to the room prepared for him, and these gentlemen also, and see that they have everything they require. Luncheon is prepared, I suppose?"

"Luncheon is waiting in the dining-room now, sir."

A little later and Nana Rau, together with his host and attendants, sat down to one of the most perfect luncheons it is possible to imagine. The Prince was a bit of an epicure in his way, and as the meal proceeded he softened. The choice champagne rendered him indifferent to the calls of Windsor. And really, it seemed quite bad taste to stand in the light of so enlightened a bon vivant as Vaughan.

Absolutely nothing had been left undone. The luncheon was a work of art, the wines were cameos in their way, and the waiting of the two confederates left nothing to be desired. In the poetic language of the modern Babylon, Nana Rau was an accomplished "tiddler"; in the old days he would have been a three-bottle man, and to leave such a feast of alcohol for a mere Court function partook almost of the nature of a crime.

"Then why leave it?" Gryde asked, when the attendants had withdrawn and he and the Prince were alone. "Stay and make an evening of it."

"What's the good of talking that dashed nonsense?" said Nana Rau thickly. "You know as well as possible that I must go."

"But it was arranged that I was to take your place."

"O! I know that's your game. I suppose you've got some diplomatic swindle on. Only show me a clear way out—a way which will absolutely absolve me from all blame—and you shall take my place with pleasure."

"I am about to do so," said Gryde.

"I think I shall be able to satisfy even your scruples if you will permit me to leave you for a minute."

Nana Rau waved his hand majestically. He wanted no other company beyond that superb champagne. He closed his eyes with the ecstasy of it He opened them again with a start five minutes later. Then, with a beatific smile upon his face, he slipped from his chair on to the floor and slept.

* * * * *

Let no slur rest upon the fair fame of Nana Rau. For instance, he was a great deal more sober than Mr. Pickwick when discovered in the village pound. But even the strongest of heads cannot rise superior to a bottle or so of '74 champagne plus a narcotic of potent properties.

A minute or two later Gryde entered the room, followed by his two "footmen."

"You fellows did your part uncommonly well," Gryde said. "The Christy minstrel on the floor is firm enough, and so are the others. They are perfectly safe here until this time to-morrow. Now then, boys—no time to be lost. Let us go upstairs at once and get the Eastern robes on. Very nice to think that we should be actually provided with our disguises."

The work was by no means easy, though Gryde was an artist so far as this branch of his profession was concerned. But patience and skill overcomes all things, and at length the task was accomplished. It would indeed have puzzled an Englishman to have told the counterfeit from the originals.

"This thing will make a bit of a stir," said Gryde.

"Egad, you are right there," said one of the others, grimly. "Look here, Mr. Vaughan, I'm not very particular, but I have jibbed a bit over this job. Any ordinary woman in England, but when it comes to--"

"You seem to regard me as somewhat simple," Gryde interrupted. "Do you suppose I should be guilty of anything in such fearful taste?"

"But I was under the impression that we were going down on purpose to—"

"So we are. But my words will come true all the same. At six o'clock this evening important information, bearing upon the face of it every evidence of truth, will reach the India Office. A certain great lady will be informed of the same without delay. And Nana Rau will not kiss the hand of her to whom he owes fealty."

The scrupulous one said no more, being quite satisfied with this explanation.

A little later a resplendent carriage drove up to the house, and the three Indians gravely emerged. Two of them stood aside and bowed low as Gryde passed, and then, when the two huge trunks were hoisted on the carriage, they entered.

The journey to Paddington was made without incident. Gryde had laid his plans so carefully, he had made so many inquiries beforehand, that he has nothing to fear from any display of ignorance on his part.

Everything went well, the retained carriage was entered at length, and the train started.

"Nothing wanting," said Gryde, with an air of satisfaction; "not a single hitch—and, really, this is a most critical part of the performance. They might have laid a strip of crimson carpet across the platform, but at times like these one is not disposed to be hypercritical. Windsor will be the next trouble."

But Windsor proved no bother at all. The red liveried servants were allowed to take everything in their own hands, and ere long the adventurers found themselves bowling along the wide avenues up to the Castle.

"How do you feel?" asked Gryde.

"Uncommonly nervous," said the others in chorus.

Gryde smiled. He did not appear to be suffering from the same malady. On the contrary, he was perfectly at his ease.

"The great charm of this mode of life," he muttered," lies in the fact that it never lacks variety."

AS FAR AS their reception was concerned, even the sensitive mind of an Indian could find nothing at which to take offence. It was, of course, with profound regret that the pseudo Nana Rau heard that no visitors could be expected at the royal table the same evening in consequence of a slight indisposition on the part of a certain great ruler. Nor was it suggested by the gorgeous official who conducted the interview that the visit of the Prince should be prolonged in consequence.

"It is greatly to be regretted," Nana murmured.

"I can assure you that the regret is mutual," was the reply. "If the Prince will honour us by dining with the Household, together with his suite"

"I shall be delighted," the Prince interpolated. "As to my suite, they had better dine in the apartment apportioned to their use. Afterwards you will greatly oblige me by letting an attendant conduct them over the state rooms, and show them some of the treasures of this wonderful place. It is a pleasure that my faithful followers have looked forward to for a long time."

"Everything shall be done to make them comfortable," the big official replied. "May I remind the Prince that we dine at eight."

Nana Rau nodded carelessly and intimated his desire to be alone with his men. The request was immediately granted. For a little time the three conspirators stood as far from the door as possible talking in whispers.

"You see how beautifully things are falling out," said Gryde. "We are here without any suspicion being aroused. There is no chance of public sentiment being awakened by a flagrant insult to the sovereign. All we have to do is to fill these big trunks in the still watches of the night, and get these good people to convey them to the station for us in the morning. By way of spotting all the things worth having, an attendant will take you round presently and point out the plums to you. But I need not waste my time on advice; you are both capital judges of articles of value."

"And as to you?"

"As to me, I dine with the Household. Of course, you both occupy my dressing-room. We leave by a train about seven, as I have an engagement in Manchester to fill to-morrow night, or, at least, the real Nana has, so we shall be away before anything is missing."

"And if things are missed just after we start?"

"What matter? We should be the last to be suspected. And you may be certain the common or garden police would never be consulted in a matter like this. Absolutely nothing in the way of a public scandal would be permitted. And say they looked like bringing it home to us. Would they care to stop us, and cart us off to a police-station? Not a bit of it. Am I not a man of power in our country? A trustworthy courtier would come to us with every expression of regret to call for the few trifles that were by mistake taken away with our luggage. But as we are not going to Jermyn Street, and as we shall emerge on Paddington platform clothed and in our right minds, they have little chance of seeing those treasures again."

There was sound logic in every word that Gryde uttered. Unless by any chance, and that was indeed a remote one, the real Indian was discovered, they were absolutely safe. But, even if by some strange fortune the Simon Pure was unearthed, the powerful drug would seal his lips for some hours yet.

It was, therefore, with an easy conscience and a mind at rest that Nana Rau went down to dine with the Household. He would have felt a little more comfortable, perhaps, in ordinary evening dress, but nobody seemed to notice this. At the same time he had the satisfaction of knowing that there was positively no flaw in his attire, and all the more so because at least two generals who knew India well were present.

Gryde said very little, and that little awkwardly. His cue was to do the shy and slightly suspicious guest, which part he acted to perfection.

A little before eleven he deemed it prudent to retire. In that exalted of all exalted spheres they are not particularly late, and by twelve o'clock sleep brooded over the Castle.

But not in the two rooms devoted to the Indian guests. They sat waiting and talking there for the critical moment to arrive, which hour had been fixed by Gryde for two. Meantime they had to wait.

"You have seen everything?" Gryde murmured.

"Well, not everything," was the reply; "but enough, and more than enough. We can take away thousands of pounds' worth of stuff without quitting this floor."

"So much the better," Gryde replied with a smile. "Never run any unnecessary risks. Not that it would matter very much if one of you were taken." The time crept slowly on, and at length the hour came. Gryde jumped to his feet. He was alert and eager enough now. There was no need for lights, as all the passages gleamed. What they had to fear were the watchmen. But there were three of them.

"Now follow me," Gryde whispered. There was no time for hesitation. The corridors appeared to be silent and deserted, but at any time a watchman might come along. But nothing happened to disturb the work of the adventurers. Tapestry hangings and Cordova leather here and there not only looked patrician and valuable, but they formed capital cover for a laden thief whose modesty is in proportion to the value of his burden.

At the end of an hour Gryde's bedroom presented an appearance of dazzling splendour. Most of the treasures collected were not only historic but of immense intrinsic value. On the whole, the haul was perhaps a better one than the theft of the regal corpse.

Even Gryde was satisfied at length.

"No more," he said. "Now remove those bars of lead from the baggage and hide them behind the curtains. Pack the stuff away quietly and then get to bed. We shall have to be up a little after six, remember."

Shortly after seven the next morning three shivering Orientals were sped away from the Castle by a big official, who strove politely to hide his yawns. When the station was reached and the Orientals were alone they developed new vigour. One of them even went so far as to see the baggage safely in the van. Perhaps he mistrusted the absent guard, for he followed it in, the others standing by th« door.

His movements were peculiar and rapid. He touched a spring on each box and the basket frames fell all to pieces. These were immediately hidden under mail bags. Three huge portmanteaux of different colour were revealed. To each of these a label bearing a different name was attached; the baggage was quite transformed.

Then the shivering Orientals went on their way to the carriage reserved for them. Directly they were inside the blinds were pulled down. The loose Eastern robes were discarded, and beneath them were disclosed three typical English garbs—a parson's, a country squire's, and that of a man about town. With the free use of the lavatory and a make-up box produced by Gryde, he and the other artists were utterly changed by the time Slough was reached. Just before then a big bundle was carefully dropped out of the window. The train pulled up at Slough. Gryde opened the window opposite the platform.

"Now," he whispered, "you've all got your tickets?"

Confederates One and Two nodded curtly. An instant later the door was closed again with the curtains still down, and the trio had reached the further platform without attracting the slightest attention. When they strolled back again by the proper way to the train they appeared to be strangers to each other, for each entered a different carriage, not, needless to remark, the one with the drawn blinds. Then the train sped on towards Paddington.

Once arrived there, Gryde was out of the carriage before the train had fairly stopped. In this move the other actors were not far behind him. The great object now was to secure the baggage and get it out of the station without delay. Out came the stuff tumbling on the platform, and a moment later the three precious portmanteaux were hoisted upon three cabs and all driven away at once to separate destinations. The coup had been accomplished!

But not with much to spare. As Gryde looked with lamb-like gaze over the tops of his glasses, a parson to the life, he saw coming down the slope into the station two quiet men, who appeared to see nothing. Gryde smiled.

"They've found it out and telegraphed," he chuckled, "or else two shining lights like Marsh and Elliott would not have been put on the job. If they have found Nana Rau, why we have no time to lose. If not, why so much the better."

It was about nine o'clock the same evening, and the three conspirators, absolutely without disguise, and qua Gryde and Co., were seated over dinner in the former's rooms. They had the air of men who had done well and virtuously

"You managed to get rid of your lot?" Gryde asked.

"Yes," the first man responded. "All beyond recognition by this time. You'll see to the disposal?"

"I suppose you are all right?" Gryde said to the other.

"I am also satisfied," said he. "We both deposited the plunder as you directed. Most of my stuff was jewelled, and you can't recognise jewels. We are as safe as houses. For my part I should like to have a bit of a rest, considering that I haven't seen my own natural face for a fortnight. When I look at myself in the glass I feel quite startled."

"Let's go round to a restaurant," suggested Gryde, " and see if anything's come out."

The proposal found favour in the eyes of the others. In the St. Giles's one or two men were languidly discussing something in connection with Windsor Castle and incidentally Indian princes.

"What's that?" Gryde demanded.

"All in the Globe," said an exhausted voice. "Rum case, by Jove!"

Gryde took up the special Globe and turned it over languidly. He had hardly' expected to find the case public. But all the same it was, and nothing had been lost in the display of the juicy item:

BURGLARY AT WINDSOR CASTLE

INGENIOUS AND SUCCESSFUL FRAUD

AN INDIAN PRINCE IS DRUGGED AND IMPERSONATED BY THIEVES

From information just received it is evident that last night a clever and successful attempt at burglary was carried out at Windsor Castle.

It appears that H.R.H. the Mahrajah of Curriebad was summoned to Windsor for some purpose of State, and this seems to have been known to the miscreants. The Prince was lured away to Epsom by an individual claiming to be an old friend of his, the pretext being an invitation to luncheon. There he and his attendants were drugged and locked in a deserted house whilst the pseudo Indians repaired to Windsor.

What happened there we are not in a position to say, but early this morning the Prince and his attendants escaped from their prison-house, and lost no time in laying the case before the proper authorities. The police are extremely reticent upon the point, but we have the best authority for saying that during the night the daring thieves carried away from Windsor articles to the value of thousands of pounds. How they managed to get clear away is a mystery, for though the sham Indians were seen to enter their reserved carriage at Windsor, it is certain they did not detrain en route. Up to the present nothing has been heard or seen of them.

At the last moment we are informed that a large bundle of Oriental robes have been picked up on the line near Slough. How they got there must for the present remain a mere matter for conjecture.

Gryde smiled as he laid the paper aside.

"Looks to me like a hoax," he said,

"Depend upon it, our friend the Mahrajah got screwed and imagined the whole thing. Burglary at Windsor Castle! The whole thing is too absurd."

With which Gryde went off to play pool, at which game, as usual, he proved singularly successful. But he declined to stay late.

"No," he said; "I was up nearly all night. Some other time, perhaps. But you chaps may depend upon it those 'Indians' will never be caught. See you fellows in a day or two. I'm going out of town to-morrow for a time."

But Gryde's tools never saw him again. They had pooled their plunder, and Gryde was to dispose of it. Yet days and weeks went by, and like the raven,

"Still is sitting, never flitting,"

they tarried for the master who came not.

"Some day," growled No. 1, "we shall meet Vaughan again; then let him look to himself. I should know him anywhere."

Vain boast, fond delusion. Tools it was necessary for Gryde to have, but as to using them and making familiar as Gryde with them—never! A myth was "Vaughan," and as a myth he is likely to remain.

SACKVILLE MAYNE was still sober, although it was nearly two. The marble clock in the Mornington Arms Hotel recorded the hour and the phenomenon. Years of vinous environment has not yet robbed Mayne of the manorial air, although the necessary acres for the part were gone long ago.

Neither had Mayne quite lost the art of dining. He had done ample justice to the dinner presented by his peripatetic host the Duke de Cavour. The wines left nothing to be desired.

"I am charmed," said the Duke in quite passable English, "charmed to have met you again. Our last foregathering in Naples was many years ago."

For Mayne's part he had forgotten the incident entirely. The Duke's memory was evidently more trustworthy than his own. All Mayne knew was that he had been in Naples at the time his noble host had mentioned. The latter, an elderly buck with small eyes and a ludicrous pointed moustache, nodded over his glass.

"Those were pleasant days," he said, "twenty years ago! Dear me! And yet when I saw you in the billiard room last night I recognised you instantly. And what horses you used to drive in those days!"

Mayne smiled. The Duke had touched him on a tender spot. As the fond mother clings to the reprobate son who spells the family ruin, so did Mayne still love the equine flesh which had been his destruction.

"I've come down in the world," he said. "Egad, how I manage to live upon my paltry little place is a mystery even to myself. But I still continue to have a bit of blood about me. It isn't every man who can boast of having bred and run two Derby winners."

"The old Godolphin blood, I presume?" suggested the Duke.

Mayne nodded. There was a bond of union between himself and his host. All he knew about the latter he had gleaned that day from the Almanach de Gotha. The exclusive volume in question recorded the fact that de Cavour was an enthusiast where racing was concerned. In a hazy kind of way, he wondered what so great a man was doing in Mornington.

"You race still?" the Duke asked.

"Oh no, I can't afford it. I only wish I could. I've got a colt entered for the Royal Clarendon Stakes at Oldmarket— run-off next week, you know—but I shall have to forfeit. Bar Sinister can beat any horse in the race bar the favourite—ay, and even beat Rialto too, if wound up."

"Come, my friend, you are not so poor as all that."

Mayne smiled into his glass. Good wine develops the philosophical side of a man's nature. It also taps the well-springs of confidence.

"Indeed I am," he said; "and yet with a little capital, I think I could see my way clear. I would sell my soul for £1,000."

"Men are prepared to take big risks for sums like that."

"I know it. I am prepared to undertake anything short of manslaughter."

The Duke paused in the manipulation of a cigarette in his slim fingers. For an elderly, gouty gentleman with a suggestion of apoplexy in the region of the carotid, he had remarkably clean sinewy hands.

"I can show you how to make £1,000 with no risk at all," he said quietly. "All you have to do is to take the money and hold your tongue."

"How pleasant! And the conditions?"

"Nothing more than the loan of your colt Bar Sinister. You will permit me to find the money for the stakes, and the horse will be sent up to-morrow to a stable I shall mention, and in due course he will win the Royal Clarendon."

"Without a month's preparation the thing is impossible."

The Duke smiled. There was a strange light in his beady eyes.

"There is many a slip, of course," he responded. "Anyway, it matters very little whether Bar Sinister wins or not. That is a mere detail in my scheme. The question is, can I have the horse if I deposit the money?"

"Now you ask the question, of course you may."

"Good. Mind, this is a profound secret. The horse is to be sent to Oldmarket to Gunter's stables to run in your name. Whether Bar Sinister wins or not matters very little. The favourite is firmly established at even money, so if I were you I should not back the colt."

Mayne nodded carelessly. It was not for him to suggest that some rascality was afloat. He had known in his time racing dukes with no more inherent morality than dustmen. "It's all the same to me," he said, "as long as I get the money. By the way, on the day following the Clarendon, the cup is run for at Silverpool. Haven't you got something starting there?"

"A horse of my own breeding," the Duke responded. "Confetti. No chance, I fear. The odds are forty to one against. Only a few personal friends know I am in England, or perhaps the odds would be a little less. You will see to this matter at once."

Mayne gave the desired assurance. Then the Duke proceeded to take from his pocket notes to the value of one thousand pounds.

"I am going to Oldmarket in the morning," he explained, "but not as the Duke de Cavour. I have my reasons for being known as Mr. Smith. If you desire to communicate with me please do so in that name per Gunter. Again let me urge upon you the advantage of silence in this matter."

A little while later and Mayne was driving his weedy bay towards his place which lay just outside Mornington. Meanwhile, the Duke de Cavour alias Smith had retired to his private sitting-room. Once there he lighted a cigarette and locked the door. With a quasi-magical sweep of his hand, he removed wig and moustache, and stood confessed for the time being in the legitimate form of Felix Gryde.

"Now let me see how I stand," he muttered, throwing himself into a chair. "I am the Duke de Cavour. In my disguise, made up from personal inspection of the distinguished individual in question, I could defy the noble mother of de Cavour to tell the difference between us. For the present the genuine article is under private restraint in Genoa. That is a fact of which the world knows nothing. To make matters still more safe, there is no need for me to appear personally, except at the finish to draw the money from the turf commissioners; and nobody will know that the horse running as Confetti in the Silverpool Cup is anything but de Cavour's colt. One way and another I ought to make £100,000 out of this business; and I deserve it, for the scheme has occupied all my care and attention for a whole year."

So saying Gryde rose and proceeded to unlock a dispatch box, and took from thence two large photographs. They were both likenesses of horses and appeared to be taken from the same plate. Gryde regarded them long and earnestly.

"A wonderful resemblance." he said, "the same age to a month, the same marks, the same everything. It's the Godolphin blood in both, I expect. Upon my word, I don't know which is Mayne's Bar Sinister, and which is the favourite for the Grand Clarendon, Sir George Julyan's Rialto. I wonder what Mayne would say if he knew I had been hanging about here for six weeks to get that photograph. And what a coup this is going to be!"

OLDMARKET, as everybody knows, is the headquarters of the racing world. There are many training establishments there, from the palatial concern with its hundreds of hands down to the tiny quarters from whence from time to time a "dark horse" emerges, and some Tom Jones springs into sudden prominence, and thenceforth is respectfully spoken of by equine scribes as Mr. Thomas Jones.

Such an establishment was Gunter's, which boasted a tumble-down house, and a row of ill-found stables tenanted for the most part by platers. Gunter and two lads found themselves quite equal to the task set before them.

Gunter was a typical specimen of his class, sharp, dapper, and cunning, and good enough for anything outside the pale of the law. On the night following the little dinner at Mornington, Gunter sat in his shabby parlour, a rank cigar in his mouth—a tumbler of gin and water before him.

On the other side of the table was a foxy-looking man, dressed like a stud groom, and whom Gunter addressed with grudging civility as Mr. Smith. We have seen him before under the guise of the Duke de Cavour.

"I suppose it is all right?" asked the latter.

"Oh, it's all right up to now" Gunter replied dubiously. "Bar Sinister came in the dusk clothed up to the eyes, and I stored him into a loose box at once. I took care that the lads didn't see too much."

"You've got them out of the way, of course?"

"Yes, they won't be back till morning. Your part of the business satisfactory?"

"Perfectly. Don't you be afraid over me. Within a fortnight's time you will have your pockets full of money, and I shall be back on my way to Australia again the richer for the coup. You see I don't show up at all—merely a horse of mine goes from this stable to run for the Silverpool Cup. The Duke de Cavour is not known in English sporting circles, and nobody takes an interest in him. It's quite safe, because there really is such a man, and at present he is under restraint—don't you hear? It doesn't matter what name I take in my betting against Rialto for the Grand Clarendon on Friday so long as I have satisfied my commissioner of my bona fides. I have employed a different commissioner to put my money on Confetti for the Silverpool."

"And if they find out that your Confetti is really--"

"How can they? Confetti has never appeared in public yet. Still, the likeness between the two horses is so wonderful that I am not particularly uneasy. Now you have a good look at the colt? You know Rialto, of course?"

"What do you think? Do I know my own mother?"

"Very good. Then come to the stables and let us see that everything is quite in order."

Gunter followed with a lantern. In one of the stalls stood a handsome dark chestnut clothed to the eyes, the clothes, strange to say, marked in blue with the monogram "G.J."—nothing less, in fact, than Sir George Julyan's copyright The set had been stolen from the owner of the favourite for the Grand Clarendon for a purpose which will be disclosed in due course.

The chestnut was stripped, and for some time Smith and Gunter stood contemplating him from all points of view.

"It is a wonderful likeness to Rialto," Gunter exclaimed. "If you'd searched the world you would not have found a better match."

"It has taken me nearly a year to do it," Smith replied.

"Well, you look like getting your money back, sir. If I could only see the next two hours safely over, why--"

"Leave that to me," responded the other sternly. "Everything is ready. You have managed to get a key to fit the back entrance to Lorrimer's stable?"

Gunter nodded. Lorrimer's was a big establishment close at hand where Sir George Julyan's horses were trained, and where Rialto, the favourite for the Grand Clarendon, lay at the present moment.

Then Smith addressed his colleague long and earnestly. The latter followed every word carefully. When the hour of midnight struck the lights were put out and the stable door gently opened. It was pitch dark then, but it made no difference to Gunter. He could have found his way for a radius of a mile blindfold. The turf was thick and yielding underfoot, so that the adventurers made no noise. They were not alone, for Gunter was leading Bar Sinister by the bridle. Silently they made their way across the heath to a spot where a clump of trees were faintly outlined. These were not far from Lorrimer's stables. The journey was made without a single soul being encountered.

The critical moment had arrived-- Smith, or to call him by his proper name, Felix Gryde, peered into the darkness. Not more than a hundred yards away from him he could make out Lorrimer's stables.

Gunter fairly shivered with excitement. Rogue and big as he was, this was the first scheme in which had entered the element of personal danger.

"Now you stay here perfectly still till you hear me whistle," Gryde said sternly; "and when I do so, bring the horse forward. Don't show up yourself, the idea being to lead these people to believe that Rialto has found his way out of the stable."

Gunter muttered something, and Gryde disappeared. He came at length to the buildings and proceeded to skirt round them till the far side was reached. Here he stopped and listened intently. Not a sound was to be heard from the semi-detached building where the favourite for the Royal Clarendon was quartered. Then Gryde stepped into the outer box, opening the door by means of a key. There was plenty of straw littering the floor, which Gryde proceeded to moisten with the aid of a jar of paraffin with which he had armed himself for the purpose.

All remained perfectly still. No sound came from the room over the box where the favourite lay beyond a tough snore. The head lad in charge of Rialto had evidently dropped into a sound slumber.

"I hope he won't sleep too long," Gryde chuckled.

The next proceeding was to advance into the box devoted to the pampered quadruped. To fix blinkers over the animal's eyes was a sufficiently delicate job, but it was at length accomplished.

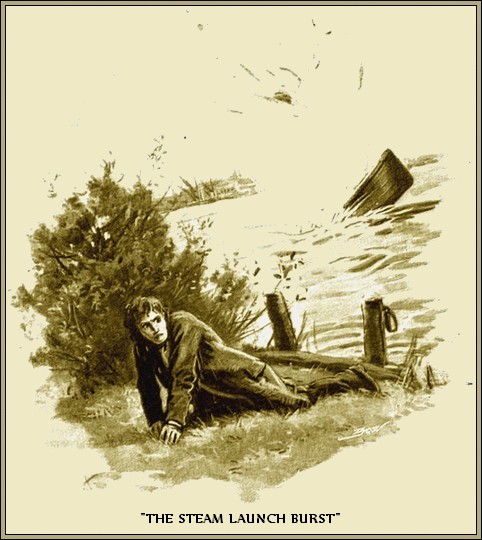

Then the far stable door was just opened. A match was laid to the saturated straw and a brilliant tongue of flame shot up. In less time than it takes to tell the whole place was roaring and crackling.

Two minutes were allowed to lapse and then Gryde crept into the open. He commenced to hammer on the walls and to yell "Fire" at the top of his voice.

From an uneasy dream the head lad was aroused. Scared and frightened he stumbled down the ladder and bolted out for his life. Before the occupants of the other boxes were aroused, Gryde had passed into the stable again. There was still room for a clear passage for the horse. It was just touch and go, but Gryde coaxed the frightened animal out and led it away into the darkness. An instant later and a shrill whistle rang out on the air.

By this time quite a small mob of helpers had arrived.

Buckets were procured, and amongst much noise and clatter the fire was extinguished. But what had become of the horse? No sooner had this question commenced to pass from lip than a pair of ears sharper than the rest discerned the sound of hoofs.

"Here's the tit," yelled a voice from the darkness, "standin' here like a lamb. Blest if I ever see such a knowing creature."

The head lad gave a sigh of relief.

"Thank goodness!" he muttered. "Here, Joe, go and turn those colts out of the far box yonder and get Rialto in at once."

Apparently the horse was none the worse for his adventure. He appeared to be unhurt down to the last row of braid upon his blanket. That anything was wrong, that the affair was anything but an accident, nobody dreamed.

Meanwhile Gryde with his prize had slipped away to an appointed spot, where he waited patiently till everything had passed off quietly. At the end of an hour Gunter approached with the greatest caution.

"Ah, I see you've got him," he whispered.

"Of course I have. How did you get on?"

"Splendidly," Gunter replied. "They never saw me at all, and they took Bar Sinister for their own Rialto as naturally as possible; and I'll lay a wager that not one of them will ever know the difference. In all the years I've been in this line, I never saw such a likeness."

"You are right there," said Gryde.

"But hadn't we better get Rialto back to our own stable without further delay?"

A little later, and Rialto stood in the place where Bar Sinister recently was. The two men watched him with admiration.

"The finest colt in England and the best three-year-old to-day," Gryde exclaimed. "But he isn't going to be Rialto or Bar Sinister any longer. Your lads haven't seen him stripped, you say, so they haven't a notion what he is like. Now then, you boast that you can 'fake' a horse better than any man in England. Let us see you get rid of those white stockings and star, in fact turn the finely trained Rialto into the half wound Confetti—the Confetti who is to land me such a coup over the Silverpool Cup."

Gunter chuckled hoarsely.

"Don't you worry," he said. "Confetti won't gain a friend when he's pulled out for the preliminary canter on Monday, and he'll win in a canter. Go and smoke a cigar in my room and leave me for a couple of hours. When you come back, I shall be able to astonish you."

All the same it was nearly daylight when Gunter summoned Gryde to see the result of his handiwork. He held up the lantern with artistic pride.

"There," he laughed hoarsely, "what do you think of that?"

Gryde expressed his satisfaction, as well he might. Gone were the white stockings and the star, gone was the sleek and glossy coat. The difference in the appearance of the colt was wonderful. He was transformed into another animal.

"Looks ragged and half trained," Gunter chuckled. "Suggests speed, but a little thick, perhaps. They'll open their eyes a bit up yonder when he spreadeagles his field for the Silverpool. He's simply chucked in at the weight."

* * * * *

An extremely fashionable crowd had assembled at Oldmarket the following afternoon to witness the race for the Grand Clarendon. Royalty was present, and the stands were packed with fair women and brave men. Amongst the latter, perfectly at home and yet apart from the rest, was a neatly attired individual, who, had he been asked his name, would have answered to that of Smith. He lolled over the railings in front of the enclosure, a cigarette in his well-gloved fingers. Any sportsman of note would have passed his get-up approvingly, and yet there was nothing about the man to attract attention—he seemed to fit quite naturally into the picture.

Probably the least excited spectator present when the horses were weighed out for the Grand Clarendon was this Smith, otherwise Gryde. Close behind him were a lot of superb sporting dandies, conspicuous amongst them being Sir George Julyan, the owner of Rialto. As the latter swept past the stand in the preliminary canter, Sir George looked a little uneasy; so did his companions.

"Is that horse really fit, Julyan?" asked one.

"I should have said emphatically yes on Monday," Julyan replied. "So you notice the difference, eh? Seems short, and inclined to lather. Just my luck if Rialto got a cold on the night of the fire."

Those of the public who knew a horse when they saw one shared the uneasiness. The favourite dropped a point or two in the betting.

As the kaleidoscope of brilliant jackets flashed out in a streaming band from under the eye of the starter Rialto dropped to fourth place, and so continued until at length the horses came into the home stretch.

"Rialto is coming, I see," remarked one of the group behind Gryde.

The latter stole a glance at Sir George's face. The latter was perfectly calm and collected, but his lips flickered like a tongue of flame in a fire.

"I don't think so," he said. "Ribton is riding him."

Just an instant the favourite shot out only to drop back again. Then amidst a perfect babel a rank outsider challenged, Rialto made a desperate effort, and finally was beaten by half a length.

The ring cheered to the echo; everybody else was ominously silent. With a click Sir George snapped his race glasses together.

"Well, they can't say Rialto didn't run a game horse," he said. "Egad, the burning of that bundle or two of straw cost me £40,000."

"Precisely the sum I have won," Gryde told himself. "The pseudo Rialto was a game horse; indeed, a little later on it may be that I have provided Sir George with a better animal than his own. No use staying here any longer. And now we shall see what kind of a turn the real Rialto will do me on Monday.

AT TWENTY minutes past three on the following Monday afternoon a ragged-looking colt with a fine turn of speed flashed along between the white posts fencing off thousands of turfites, and once more the ring was rejoicing in the pleasing and remunerative pastime of "skinning the lamb."

Outsiders frequently win big races, but the spectacle of a horse absolutely unknown striding twenty lengths ahead of anything else past the judge's chair is not quite so common. Until the numbers went up, nobody knew who had won the Silverpool.

There was a good deal of raucous mirtn in the ring. But one or two Napoleons of the pencil were observed to look grave. The owner of the fortunate Confetti was supposed to be somewhere on the course, but nobody had seen him.

After the jockey had weighed in, Gunter and "Mr. Smith" discussed the matter calmly.

"You are perfectly satisfied?" asked the latter.

"Well, what do you think?" exclaimed the delighted Gunter. "I've made ten thousand clear. And a prettier plant, a plant more worthy of 'Awley Smart, I never heard tell of. I expect you've done better."

"A trifle," Gryde said drily. "You know what to do next. It seems a pity, but it's the only way to keep the thing from creeping out. Rialto, otherwise Confetti, must never run another race."

Gunter winked knowingly.

"It does seem a pity," he said, "but I'll do exactly as you tell me."

The confederates shook hands and parted. It was the last time they were likely to meet: a piece of information Gryde did not deem it necessary to impart to Gunter. And as the former sat in propria persona and entirely shorn of disguise in his club, he was calmly reading as follows in the special Globe:

THE SILVERPOOL CUP

DEATH OF THE WINNER

The sensational victory of the rank outsider Confetti in the Silverpool Cup to-day is followed by a no less tragic sequel. It appears that whilst the animal was being personally rubbed down by Gunter, his trainer, the colt burst a blood vessel, and died a few minutes later. Confetti had no other engagements this season, but all the same the Duke de Cavour is to be condoled with on his loss.

Gryde smiled as he lay back smoking a thoughtful cigar.

"Really," he told himself, "this has been a very pretty piece of business. And they say there cannot be anything new in the way of a racing fraud. Not only have I proved the contrary, but also I have hit upon a scheme which will never be found out. First I find a horse so like Rialto that I exchange one for the other without fear of detection. Even the Grand Clarendon defect is naturally accounted for. I make a pile of money laying against Rialto—a certainty this. Then the real Rialto, artistically faked, runs as Confetti. This means still more money. And as the Duke is safely out of the way, where he is likely to see no English papers, with friends who don't know a horse from a halter, that avenue of detection is closed. The rest of my money I can safely draw on Monday, and then "Mr. Smith's" place will know him no more. A pity to destroy Rialto, but it was necessary. The course taken renders everything absolutely safe.

"And as to Sackville Mayne? Well, Mr. Mayne is not likely to open his mouth. He has had a thousand pounds for his horse, knowing perfectly well that some swindle was afloat, and though he may wonder, the last thing he will do will be to ask questions. You can always, buy that class of man. Perhaps I ought to have had Bar Sinister, now passing as Rialto, poisoned, but that is a mere detail. And how easy it has all been! Really, next time I must try something with an element of danger in it. Wonder if there is anyone in the billiard-room. I should like a bit of excitement after this humdrum business."

THE Daily Telephone of June 19th last contained the following announcement:

"The claim made by the Randstrand Republic against the Cape Federation Company has at length been settled upon terms. The official arbitrators have assessed the damages at one million of pounds, which is ordered to be paid within the next four weeks. Whether this is the final chapter in the romance of the Morrison Raid remains to be seen. If the latest advices from South Africa are to be trusted, this is merely the prologue."

Thousands of interested Englishmen read the paragraph over the matutinal coffee, but none perused it with more interest than Mr. James Greenbaulm, the eminent Cape merchant, in his Fenchurch Street office.

Greenbaulm had not been in England long. He was understood to be one of the most recent of the Cape millionaires, and he had come to this country with the intention of opening a personal branch in London. For the rest, he was in avowed sympathy with the Randstrand Government, and as frankly against England. Open hostility of this kind is only possible in this country — indeed, we rather seem to encourage it.

A large, pursy, clean-shaven man, with sub-Semitic cast of face and piercing grey eyes was Greenbaulm. He was the incarnation of sleek respectability. His very garments suggested Capital. The type can be recognised at a glance; it is met only in the City, though the genus does occasionally stray as far as Manchester and Liverpool.

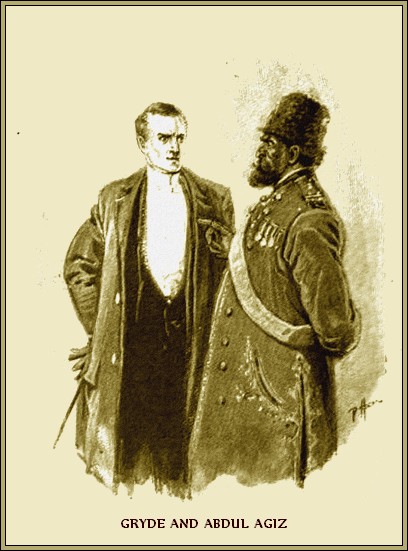

An electric gleam flashed behind Greenbaulm's spectacles. He laid the Telephone aside with an air of decision; then he quitted his office and made his way to a set of chambers in one of the narrow streets off Cheapside. Hereabouts are situated the offices of Lemesurier and Co., merchants.

Greenbaulm demanded to see the head of the firm, and was at once admitted into the latter's private room. A thin man, with sanguine, eager face and thin nervous lips, rose to greet him. Enthusiast was writ large all over him. There was no bigger crank and no more brilliant specimen of a Little Englander in the House of Commons than Stephen Lemesurier. Some men have creeds, others have nothing but passions. Lemesurier belonged to the latter category.

The Morrison Raid had stirred all the emotion in his nature. He would have given a good round sum to see England driven bag and baggage out of the Randstrand. And if open hostilities broke out, he had publicly announced his intention of giving £100,000 to the oppressed Republic. Neither was Lemesurier alone in this determination. There were others besides himself, as Greenbaulm was perfectly aware.

"You have seen the Telephone?" said the latter. "What are you going to do?"

"Act," Lemesurier cried. "As a Randstrander yourself, you must know as much as I do. There is trouble brewing out yonder; our Government means to force the Republic into fighting—there will be more disgraceful landgrabbing. But this award is a slice of luck I hardly expected."

"We haven't got it yet," Greenbaulm said drily.

"No, but it is certain to come. The question is, will it come in time? I think not. Therefore a few of us have decided to advance the million to the accredited agent of the Randstrand Republic, taking a lien on the award as security. Nine of us are prepared to put down our money at any time; indeed, it is already posted in the United Cape Bank here. We want one more man to find a tenth."

Greenbaulm produced a cheque-book from his pocket and dashed off a draft. This he coolly handed to Lemesurier.

"That matter is settled then," he said. "I take it Dr. Leyden can draw the money at any time he requires. Of course you know that every penny of this is going to be laid out in Brussels."

"For munitions of war. Certainly I do. I quite understood that was the object of the advance. It would never do for the stuff to come from Germany, though Germany is backing up the Republic. But isn't it quite time that Dr. Leyden should reach here from Berlin?"

"Leyden is not in Berlin at all," Greenbaulm explained. "The papers are all wrong. He is in London—or, at least, he will be to-morrow—for a few days, and he will call upon you at a time to be arranged for the cheque."

"I should like to have his address," Lemesurier suggested.

"He has no address. It is better not. He will call upon you the first thing. And you will recommend him—we are strangers—to come and see me at Hammersmith. You can give him directions where to find me. And the sooner this business is settled the better, you understand."

Whereupon Greenbaulm went off about his business. A peculiar smile flickered about the corners of his mouth as he went along.

"If I were an absolute monarch," he muttered, "I would hang a man like that. This is the only country in the world where a man can boast of being a traitor with impunity. But you are going to have an expensive lesson, Mr. Lemesurier."

The inference of all this was perfectly plain. A few fanatics were going to advance the sinews of war to a prospective enemy. And Dr. Leyden, the accredited agent of the opposing State, was coming to fetch the money. In specie, the same could be transferred to the Continent and there exchanged for lethal weapons.

But Greenbaulm did not return immediately to his office; in fact, he was not seen there for the rest of the day. Instead of this he called a cab and astonished the driver by an order to proceed to Poplar. The transaction was agreed to upon terms highly satisfactory to the jehu.*

[ * Jehu - cab-driver. After King Jehu in the Old Testament, known for driving his chariot furiously. ]

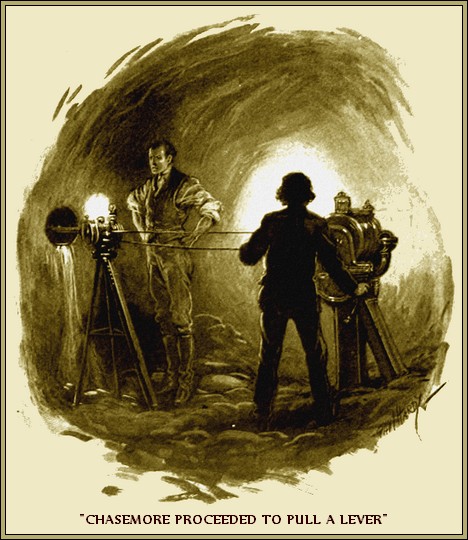

Most people knew, by name at least, the famous Poplar establishment of Elswick and Company. There everything ingenious and mechanical that goes upon wheels is manufactured. Greenbaulm was evidently expected, for one of the partners met him.