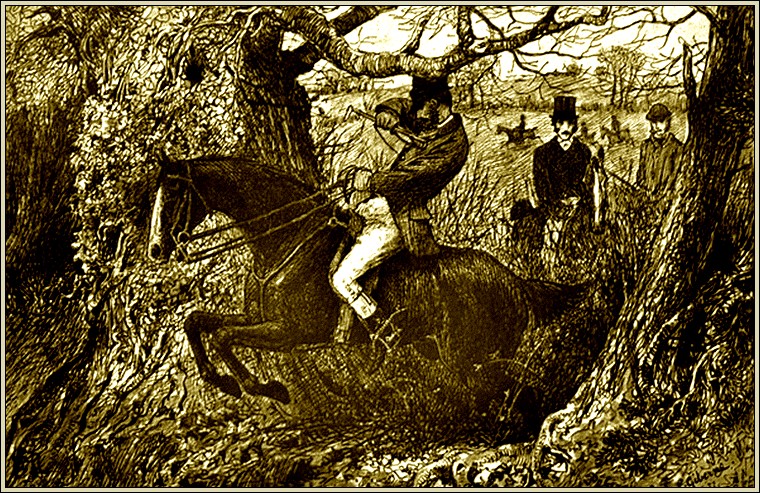

Frontispiece: ...leaving brothers, husbands, even admirers, hopelessly in the rear.

As in the choice of a horse and a wife a man must please himself, ignoring the opinion and advice of friends, so in the governing of each it is unwise to follow out any fixed system of discipline. Much depends on temper, education, mutual understanding and surrounding circumstances. Courage must not be heated to recklessness, caution should be implied rather than exhibited, and confidence is simply a question of time and place. It is as difficult to explain by precept or demonstrate by example how force, balance, and persuasion ought to be combined in horsemanship, as to teach the art of floating in the water or swimming on the back. Practice in either case alone makes perfect, and he is the most apt pupil who brings to his lesson a good opinion of his own powers and implicit reliance on that which carries him. Trust the element or the animal and you ride aloft superior to danger; but with misgiving comes confusion, effort, breathlessness, possibly collapse and defeat. Morally and physically, there is no creature so nervous as a man out of his depth.

In offering the following pages to the public, the writer begs emphatically to disclaim any intention of laying down the law on such a subject as horsemanship. Every man who wears spurs believes himself more or less an adept in the art of riding; and it would be the height of presumption for one who has studied that art as a pleasure and not a profession to dictate for the ignorant, or enter the lists of argument with the wise. All he can lay claim to is a certain amount of experience, the result of many happy hours spent with the noble animal under him, of some uncomfortable minutes when mutual indiscretion has caused that position to be reversed.

If the few hints he can offer should prove serviceable to the beginner he will feel amply rewarded, and will only ask to be kindly remembered hereafter in the hour of triumph when the tyro of a riding-school has become the pride of a hunting-field,—judicious, cool, daring, and skilful—light of hand, firm of seat, thoroughly at home in the saddle, a very Centaur

"Encorpsed and demi-natured With the brave beast."

In our dealings with the brute creation, it cannot be too much insisted on that mutual confidence is only to be established by mutual good-will. The perceptions of the beast must be raised to their highest standard, and there is no such enemy to intelligence as fear. Reward should be as the daily food it eats, punishment as the medicine administered on rare occasions, unwillingly, and but when absolute necessity demands. The horse is of all domestic animals most susceptible to anything like discomfort or ill-usage. Its nervous system, sensitive and highly strung, is capable of daring effort under excitement, but collapses utterly in any new and strange situation, as if paralysed by apprehensions of the unknown. Can anything be more helpless than the young horse you take out hunting the first time he finds himself in a bog? Compare his frantic struggles and sudden prostration with the discreet conduct of an Exmoor pony in the same predicament. The one terrified by unaccustomed danger, and relying instinctively on the speed that seems his natural refuge, plunges wildly forward, sinks to his girths, his shoulders, finally unseats his rider, and settles down, without further exertion, in the stupid apathy of despair.

The other, born and bred in the wild west country, picking its scanty keep from a foal off the treacherous surface of a Devonshire moor, either refuses altogether to trust the quagmire, or shortens its stride, collects its energies, chooses the soundest tufts that afford foothold, and failing these, flaps its way out on its side, to scramble into safety with scarce a quiver or a snort. It has been there before! Herein lies the whole secret. Some day your young one will be as calm, as wise, as tractable. Alas! that when his discretion has reached its prime his legs begin to fail!

Therefore cultivate his intellect—I use the word advisedly—even before you enter on the development of his physical powers. Nature and good keep will provide for these, but to make him man's willing friend and partner you must give him the advantage of man's company and man's instruction. From the day you slip a halter over his ears he should be encouraged to look to you, like a child, for all his little wants and simple pleasures. He should come cantering up from the farthest corner of the paddock when he hears your voice, should ask to have his nose rubbed, his head stroked, his neck patted, with those honest, pleading looks which make the confidence of a dumb creature so touching; and before a roller has been put on his back, or a snaffle in his mouth he should be convinced that everything you do to him is right, and that it is impossible for _you_, his best friend, to cause him the least uneasiness or harm.

I once owned a mare that would push her nose into my pockets in search of bread and sugar, would lick my face and hands like a dog, or suffer me to cling to any part of her limbs and body while she stood perfectly motionless. On one occasion, when I hung in the stirrup after a fall, she never stirred on rising, till by a succession of laborious and ludicrous efforts I could swing myself back into the saddle, with my foot still fast, though hounds were running hard and she loved hunting dearly in her heart. As a friend remarked at the time, "The little mare seems very fond of you, or there might have been a bother!"

Now this affection was but the result of petting, sugar, kind and encouraging words, particularly at her fences, and a rigid abstinence from abuse of the bridle and the spur. I shall presently have something to say about both these instruments, but I may remark in the mean time that many more horses than people suppose will cross a country safely with a loose rein. The late Colonel William Greenwood, one of the finest riders in the world, might be seen out hunting with a single curb-bridle, such as is called "a hard-and-sharp" and commonly used only in the streets of London or the Park. The present Lord Spencer, of whom it is enough to say that he hunts one pack of his own hounds in Northamptonshire, and is always _in the same field with them_, never seems to have a horse pull, or until it is tired, even lean on his hand. I have watched both these gentlemen intently to learn their secret, but I regret to say without avail.

This, however, is not the present question. Long before a bridle is fitted on the colt's head he should have so thoroughly learned the habit of obedience, that it has become a second instinct, and to do what is required of him seems as natural as to eat when he is hungry or lie down when he wants to sleep.

This result is to be attained in a longer or shorter time, according to different tempers, but the first and most important step is surely gained when we have succeeded in winning that affection which nurses and children call "cupboard love." Like many amiable characters on two legs, the quadruped is shy of acquaintances but genial with friends. Make him understand that you are his best and wisest, that all you do conduces to his comfort and happiness, be careful at first not to deceive or disappoint him, and you will find his reasoning powers quite strong enough to grasp the relations of cause and effect.

In a month or six weeks he will come to your call, and follow you about like a dog. Soon he will let you lift his feet, handle him all over, pull his tail, and lean your weight on any part of his body, without alarm or resentment. When thoroughly familiar with your face, your voice, and the motions of your limbs, you may back him with perfect safety, and he will move as soberly under you in any place to which he is accustomed as the oldest horse in your stable.

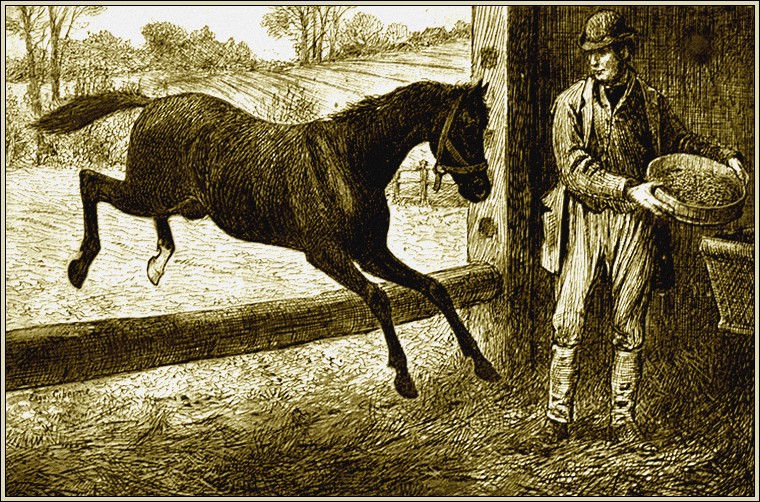

Do not forget, however, that education should be gradual as moon-rise, perceptible, not in progress, but result. I recollect one morning riding to covert with a Dorsetshire farmer whose horses, bred at home, were celebrated as timber-jumpers even in that most timber-jumping of countries. I asked him how they arrived at this proficiency without breaking somebody's neck, and he imparted his plan.

The colt, it seemed, ran loose from a yearling in the owner's straw-yard, but fed in a lofty out-house, across the door of which was placed a single tough ashen bar that would not break under a bullock. This was laid on the ground till the young one had grown thoroughly accustomed to it, and then raised very gradually to such a height as was less trouble to jump than clamber over. At three feet the two-year old thought no more of the obstacle than a girl does of her skipping-rope. After that, it was heightened an inch every week, and it needs no ready reckoner to tell us at the end of six months how formidable a leap the animal voluntarily negotiated three times a day. "It's never put no higher," continued my informant; "I'm an old man now, and that's good enough for me."

I should think it was! A horse that can leap five feet of timber in cold blood is not likely to be pounded, while still unblown, in any part of England I have yet seen.

The Dorsetshire farmer's plan of teaching horses to jump timber.

Now the Dorsetshire farmer's system was sound, and based on common sense. As you bend the twig so grows the tree, therefore prepare your pupil from the first for the purpose you intend him to serve hereafter. An Arab foal, as we know, brought up in the Bedouin's tent, like another child, among the Bedouin's children, is the most docile of its kind, and I cannot but think that if he lived in our houses and we took as much notice of him, the horse would prove quite as sagacious as the dog; but we must never forget that to harshness or intimidation he is the most sensitive of creatures, and even when in fault should be rather cautioned than reproved.

An ounce of illustration is worth a pound of argument, and the following example best conveys the spirit in which our brave and willing servant should be treated by his lord.

Many years ago, when he hunted the Cottesmore country, Sir Richard Sutton's hounds had been running hard from Glooston Wood along the valley under Cranehoe by Slawston to Holt. After thirty minutes or so over this beautiful, but exceedingly stiff line, their heads went up, and they came to a check, possibly from their own dash and eagerness, certainly, at that pace and amongst those fences, _not from being overridden_.

"Turn 'em, Ben!" exclaimed Sir Richard, with a dirty coat, and Hotspur in a lather, but determined not to lose a moment in getting after his fox. "Yes, Sir Richard," answered Morgan, running his horse without a moment's hesitation at a flight of double-posts and rails, with a ditch in the middle and one on each side! The good grey, having gone in front from the find, was perhaps a little blown, and dropping his hind legs in the farthest ditch, rolled very handsomely into the next field. "It's not _your_ fault, old man!" said Ben, patting his favourite on the neck as they rose together in mutual good-will, adding in the same breath, while he leapt to the saddle, and Tranby acknowledged the line—"Forrard on, Sir Richard!—Hoic together, hoic! You'll have him directly, my beauties! He's a Quorn fox, and he'll do you good!"

I had always considered Ben Morgan an unusually fine rider. For the first time, I began to understand _why_ his horse never failed to carry him so willingly and so well.

I do not remember whether Dick Webster was out with us that day, but I am sure if he was he has not forgotten it, and I mention him as another example of daring horsemanship combined with an imperturbable good humour, almost verging on buffoonery, which seems to accept the most dangerous falls as enhancing the fun afforded by a delightful game of romps. His annual exhibition of prowess at the Islington horse show has made his shrewd comical face so familiar to the public that his name, without farther comment, is enough to recall the presence and bearing of the man—his quips and cranks and merry jests, his shrill whistle and ready smile, his strong seat and light, skilful hand, but above all his untiring patience and unfailing kindness with the most restive and refractory of pupils. Dick, like many other good fellows, is not so young as he was, but he will probably be an unequalled rider at eighty, and I am quite sure that if he lives to the age of Methuselah, the extreme of senile irritability will never provoke him to lose his temper with a horse.

Presence of mind under difficulties is the one quality that in riding makes all the difference between getting off with a scramble and going down with a fall. If unvaried kindness has taught your horse to place confidence in his rider, he will have his wits about him, and provide for _your_ safety as for his own. When left to himself, and not flurried by the fear of punishment, even an inexperienced hunter makes surprising efforts to keep on his legs, and it is not too much to say that while his wind lasts, the veteran is almost as difficult to catch tripping as a cat. I have known horses drop their hind legs on places scarcely affording foothold for a goat, but in all such feats they have been ridden by a lover of the animal, who trusts it implicitly, and rules by kindness rather than fear.

I will not deny that there are cases in which the _suaviter in modo_ must be supplemented by the _fortiter in re_. Still the insubordination of ignorance is never wholly inexcusable, and great discretion must be used in repressing even the most violent of outbreaks. If severity is absolutely required, be sure to temper justice with mercy, remembering that, in brute natures at least, the more you spare the rod, the less you spoil the child!

I recollect, in years gone by, an old and pleasant comrade used to declare that "to be in a rage was almost as contemptible as to be in a funk!" Doubtless the passion of anger, though less despised than that of fear, is so far derogatory to the dignity of man that it deprives him temporarily of reason, the very quality which confers sovereignty over the brute. When a magician is without his talisman the slaves he used to rule will do his bidding no longer. When we say of such a one that he has "lost his head," we no more expect him to steer a judicious course than a ship that has lost her rudder. Both are the prey of circumstances—at the mercy of winds and waves. Therefore, however hard you are compelled to hit, be sure to keep your temper. Strike in perfect good-humour, and in the right place. Many people cannot encounter resistance of any kind without anger, even a difference of opinion in conversation is sufficient to rouse their bile; but such are seldom winners in argument or in fight. Let them also leave education alone. Nature never meant them to teach the young idea how to shoot or hunt, or do anything else!

It is the cold-blooded and sagacious wrestler who takes the prize, the calm and imperturbable player who wins the game. In all struggles for supremacy, excitement only produces flurry, and flurry means defeat.

Who ever saw Mr. Anstruther Thompson in a passion, though, like every other huntsman and master of hounds, he must often have found his temper sorely tried? And yet, when punishment is absolutely necessary to extort obedience from the equine rebel, no man can administer it more severely, either from the saddle or the box. But whether double-thonging a restive wheeler, or "having it out" with a resolute buck-jumper, the operation is performed with the same pleasant smile, and when one of the adversaries preserves calmness and common sense, the fight is soon over, and the victory gained.

It is not every man, however, who possesses this gentleman's iron nerve and powerful frame. For most of us, it is well to remember, before engaging in such contests, that defeat is absolute ruin. We must be prepared to fight it out to the bitter end, and if we are not sure of our own firmness, either mental or physical it is well to temporise, and try to win by diplomacy the terms we dare not wrest by force. If the latter alternative must needs be accepted, in this as in most stand-up fights, it will be found that the first blow is half the battle. The rider should take his horse short by the head and let him have two or three stingers with a cutting whip—not more—particularly, if on a thorough-bred one, as low down the flanks as can be reached, administered without warning, and in quick succession, sitting back as prepared for the plunge into the air that will inevitably follow, keeping his horse's head well-up the while to prevent buck-jumping. He should then turn the animal round and round half-a-dozen times, till it is confused, and start it off at speed in any direction where there is room for a gallop. Blown, startled, and intimidated, he will in all probability find his pupil perfectly amenable to reason when he pulls up, and should then coax and soothe him into an equable frame of mind once more. Such, however, is an extreme case. It is far better to avoid the _ultima ratio_. In equitation, as in matrimony, there should never arise "_the first quarrel_." Obedience, in horses, ought to be a matter of habit, contracted so imperceptibly that its acquirement can scarcely be called a lesson.

This is why the hunting-field is such a good school for leaping. Horses of every kind are prompted by some unaccountable impulse to follow a pack of hounds, and the beginner finds himself voluntarily performing feats of activity and daring, in accordance with the will of his rider, which no coercion from the latter would have induced him to attempt. Flushed with success, and if fortunate enough to escape a fall, confident in his lately-discovered powers, he finds a new pleasure in their exercise, and, most precious of qualities in a hunter, grows "fond of jumping."

The same result is to be attained at home, but is far more gradual, requiring the exercise of much care, patience, and perseverance.

Nevertheless, when we consider the inconvenience created by the vagaries of young horses in the hunting field, to hounds, sportsmen, ladies, pedestrians, and their own riders, we must admit that the Irish system is best, and that a colt, to use the favourite expression, should have been trained into "an accomplished lepper," before he is asked to carry a sportsman through a run.

Mr. Rarey, no doubt, thoroughly understood the nature of the animal with which he had to deal. His system was but a convenient application of our principle, viz., Judicious coercion, so employed that the brute obeys the man without knowing why. When forced to the earth, and compelled to remain there, apparently by the mere volition of a creature so much smaller and feebler than itself, it seemed to acknowledge some mysterious and over-mastering power such as the disciples of Mesmer profess to exercise on their believers, and this, in truth, is the whole secret of man's dominion over the beasts of the field. It is founded, to speak practically, on reason in both, the larger share being apportioned to the weaker frame. If by terror or resentment, the result of injudicious severity, that reason becomes obscured in the stronger animal, we have a maniac to deal with, possessing the strength of ten human beings, over whom we have lost our only shadow of control! Where is our supremacy then? It existed but in the imagination of the beast, for which, so long as it never tried to break the bond, a silken thread was as strong as an iron chain.

Perhaps this is the theory of all government, but with the conduct and coercion of mankind we have at present nothing to do.

There is a peculiarity in horses that none who spend much time in the saddle can have failed to notice. It is the readiness with which all accommodate themselves to a rider who succeeds in subjugating _one_. Some men possess a faculty, impossible to explain, of establishing a good understanding from the moment they place themselves in the saddle. It can hardly be called hand, for I have seen consummate horsemen, notably Mr. Lovell, of the New Forest, who have lost an arm; nor seat, or how could Colonel Fraser, late of the 11th Hussars, be one of the best heavy-weights over such a country as Meath, with a broken and contracted thigh? Certainly not nerve, for there are few fields too scanty to furnish examples of men who possess every quality of horsemanship except daring. What is it then? I cannot tell, but if you are fortunate enough to possess it, whether you weigh ten stone or twenty, you will be able to mount yourself fifty pounds cheaper than anybody else in the market! Be it an impulse of nature, or a result of education, there is a tendency in every horse to make vigorous efforts at the shortest notice in obedience to the inclination of a rider's body or the pressure of his limbs. Such indications are of the utmost service in an emergency, and to offer them at the happy moment is a crucial test of horsemanship. Thus races are "snatched out of the fire," as it is termed, "by riding," and this is the quality that, where judgment, patience, and knowledge of pace are equal, renders one jockey superior to the rest. It enables a proficient also to clear those large fences that, in our grazing districts especially, appear impracticable to the uninitiated, as if the horse borrowed muscular energy, no less than mental courage, from the resolution of his rider. On the racecourse and in the hunting field, Custance, the well-known jockey, possesses this quality in the highest degree. The same determined strength in the saddle, that had done him such good service amongst the bullfinches and "oxers" of his native Rutland, applied at the happy moment, secured on a great occasion his celebrated victory with King Lud.

There are two kinds of hunters that require coercion in following hounds, and he is indeed a master of his art who feels equally at home on each. The one must be _steered_, the other _smuggled_ over a country. As he is never comfortable but in front, we will take the rash horse first.

Let us suppose you have not ridden him before, that you like his appearance, his action, all his qualities except his boundless ambition, that you are in a practicable country, as seems only fair, and about to draw a covert affording every prospect of a run. Before you put your foot in the stirrup be sure to examine his bit—not one groom in a hundred knows how to bridle a horse properly—and remember that on the fitting of this important article depends your success, your enjoyment, perhaps your safety, during the day. Horses, like servants, will never let their master be happy if they are uncomfortable themselves. See that your headstall is long enough, so that the pressure may lie on the bars of the horse's mouth and not crumple up the corners of his lips, like a gag. The curb-chain will probably be too tight, also the throat-lash; if so, loosen both, and with your own hands; it is a pleasant way of making acquaintance, and may perhaps prepossess him in your favour. If he wears a nose-band it will be time enough to take it off when you find he shows impatience of the restriction by shaking his head, changing his leg frequently, or reaching unjustifiably at the rein.

I am prejudiced against the nose-band. I frankly admit a man in a minority of one _must_ be wrong, but I never rode a horse in my life that, to my own feeling, did not go more comfortably when I took it off.

Look also to your girths. For a fractious temper they are very irritating when drawn too tight, while with good shape and a breast-plate, there is little danger of their not being tight enough. When these preliminaries have been carefully gone through mount nimbly to the saddle, and take the first opportunity of feeling your new friend's mouth and paces in trot, canter, and gallop. Here, too, though in general it should be avoided for many reasons, social, agricultural, and personal, a little "larking" is not wholly inexcusable. It will promote cordiality between man and beast. The latter, as we are considering him, is sure to be fond of jumping, and to ride him over a fence or two away from other horses in cold blood will create in his mind the very desirable impression that you are of a daring spirit, determined to be in front.

Take him, however, up to his leap as slow as he will permit—if possible at a trot. Even should he break into a canter and become impetuous at last, there is no space for a violent rush in three strides, during which you must hold him in a firm, equable grasp. As he leaves the ground give him his head, he cannot have "too much rope," till he lands again, when, as soon as possible, you should pull him back to a trot, handling him delicately, soothing him with voice and gesture, treating the whole affair as the simplest matter of course. Do not bring him again over the same place, rather take him on for two or three fields in a line parallel to the hounds. By the time they are put into covert you will have established a mutual understanding, and found out how much you _dislike_ one another at the worst! It is well now to avoid the crowd, but beware of taking up a position by yourself where you may head the fox! No man can ride in good-humour under a sense of guilt, and you _must_ be good-humoured with such a mount as you have under you to-day.

Exhaust, therefore, all your knowledge of woodcraft to get away on good terms with the hounds. The wildest romp in a rush of horses is often perfectly temperate and amenable when called on to cut out the work. Should you, by ill luck, find yourself behind others in the first field, avoid, if possible, following any one of them over the first fence. Even though it be somewhat black and forbidding, choose a fresh place, so free a horse as yours will jump the more carefully that his attention is not distracted by a leader, and there is the further consideration, based on common humanity, that your leader might fall when too late for you to stop. No man is in so false a position as he who rides over a friend in the hunting field, except the friend!

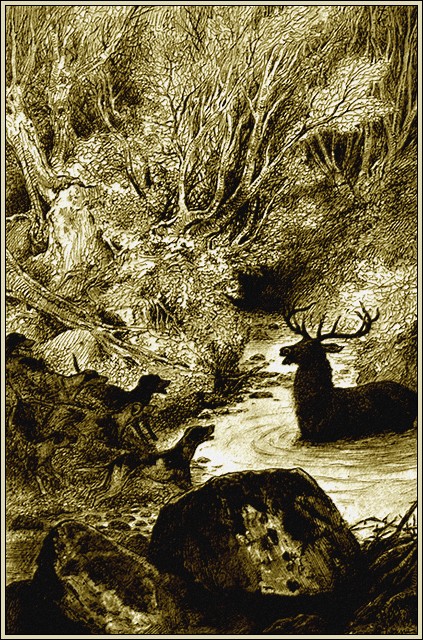

Take your own line. If you be not afraid to gallop and the hounds _run on_, you will probably find it plain sailing till they check. Should a brook laugh in your face, of no unreasonable dimensions, you may charge it with confidence, a rash horse usually jumps width, and there will be plenty of "room to ride" on the far side. It takes but a few feet of water to decimate a field. I may here observe that, if, as they cross, you see the hounds leap at it, even though they fall short, you may be sure the distance from bank to bank is within the compass of a hunter's stride.

At timber, I would not have you quite so confident. When, as in Leicestershire, it is set fairly in line with the fence and there is a good take-off, your horse, however impetuous, may leap it with impunity in his stroke, but should the ground be poached by cattle, or dip as you come to it, beware of too great hurry. The feat ought then to be accomplished calmly and collectedly at a trot, the horse taking his time, so to speak, from the motions of his rider, and jumping, as it is called, "to his hand." Now when man and horse are at variance on so important a matter as pace, the one is almost sure to interfere at the wrong moment, the other to take off too soon or get too close under his leap; in either case the animal is more likely to rise at a fence than a rail, and if unsuccessful in clearing it a binder is less dangerous to flirt with than a bar. Lord Wilton seems to me to ride at timber a turn slower than usual, Lord Grey a turn faster. Whether father and son differ in theory I am unable to say, I can only affirm that both are undeniable in practice. Mr. Fellowes of Shottisham, perhaps the best of his day, and Mr. Gilmour, _facile princeps_, almost walk up to this kind of leap; Colonel, now General Pearson, known for so many seasons as "the flying Captain," charges it like a squadron of Sikh cavalry; Captain Arthur Smith pulls back to a trot; Lord Carington scarcely shortens the stride of his gallop. Who shall decide between such professors? Much depends on circumstances, more perhaps on horses. Assheton Smith used to throw the reins on a hunter's neck when rising at a gate, and say,—"Take care of yourself, you brute!"—whereas the celebrated Lord Jersey, who gave me this information of his old friend's style, held his own bridle in a vice at such emergencies, and both usually got safe over! Perhaps the logical deduction from these conflicting examples should be not to jump timber at all!

But the rash horse is by this time getting tired, and now, if you would avoid a casualty, you must temper valour with discretion, and ride him as skilfully as you _can_.

He has probably carried you well and pleasantly during the few happy moments that intervened between freshness and fatigue; now he is beginning to pull again, but in a more set and determined manner than at first. He does not collect himself so readily, and wants to go faster than ever at his fences, if you would let him. This careless, rushing style threatens a downfall, and to counteract it will require the exercise of your utmost skill. Carry his head for him, since he seems to require it, and endeavour, by main force if necessary, to bring him to his leaps with his hind legs under him. Half-beaten horses measure distance with great accuracy, and "lob" over very large places, when properly ridden. If, notwithstanding all your precautions, he persists in going on his shoulders, blundering through his places, and labouring across ridge and furrow like a boat in a heavy sea, take advantage of the first lane you find, and voting the run nearly over, make up your mind to view the rest of it in safety from the hard road!

Ride the same horse again at the first opportunity, and, if sound enough to come out in his turn, a month's open weather will probably make him a very pleasant mount.

The "slug," a thorough-bred one, we will say, with capital hind-ribs, lop ears, and a lazy eye, must be managed on a very different system from the foregoing. You need not be so particular about his bridle, for the coercion in this case is of impulsion rather than restraint, but I would advise you to select a useful cutting-whip, stiff and strong enough to push a gate. Not that you must use it freely—one or two "reminders" at the right moment, and an occasional flourish, ought to carry you through the day. Be sure, too, that you strike underhanded, and not in front of your own body, lest you take his eye off at the critical moment when your horse is measuring his leap. The best riders prefer such an instrument to the spurs, as a stimulant to increased pace and momentary exertion.

You will have little trouble with this kind of hunter while hounds are drawing. He will seem only too happy to stand still, and you may sit amongst your friends in the middle ride, smoking, joking, and holding forth to your heart's content. But, like the fox, you will find your troubles begin with the cheering holloa of "Gone away!"

On your present mount, instead of avoiding the crowd, I should advise you to keep in the very midst of the torrent that, pent up in covert, rushes down the main ride to choke a narrow handgate, and overflow the adjoining field. Emerging from the jaws of their inconvenient egress, they will scatter, like a row of beads when the string breaks, and while the majority incline to right or left, regardless of the line of chase as compared with that of safety, some half dozen are sure to single themselves out, and ride straight after the hounds.

Select one of these, a determined horseman, whom you know to be mounted on an experienced hunter; give him _plenty of room_—fifty yards at least—and ride his line, nothing doubting, fence for fence, till your horse's blood is up, and your own too. I cannot enough insist on a jealous care of your leader's safety, and a little consideration for his prejudices. The boldest sportsmen are exceedingly touchy about being ridden over, and not without reason. There is something unpleasantly suggestive in the bit, and teeth, and tongue of an open mouth at your ear; while your own horse, quivering high in air, makes the discovery that he has not allowed margin enough for the yawner under his nose! It is little less inexcusable to pick a man's pocket than to ride in it; and no apology can exonerate so flagrant an assault as to land on him when down. Reflect, also, that a hunter, after the effort to clear his fence, often loses foothold, particularly over ridge and furrow, in the second or third stride, and falls at the very moment a follower would suppose he was safe over. Therefore, do not begin for yourself till your leader is twenty yards into the next field when you may harden your heart, set your muscles, and give your horse to understand, by seat and manner, that it must be in, through, or over.

Beware, however, of hurrying him off his legs. Ride him resolutely, indeed, but in a short, contracted stride; slower in proportion to the unwillingness he betrays, so as to hold him in a vice, and squeeze him up to the brink of his task, when, forbidden to turn from it, he will probably make his effort in self-defence, and take you somehow to the other side. Not one hunter in a hundred can jump in good form when going at speed; it is the perfection of equine prowess, resulting from great quickness and the confidence of much experience. An arrant refuser usually puts on the steam of his own accord, like a confirmed rusher, and wheels to right or left at the last moment, with an activity that, displayed in a better cause, would be beyond praise. The rider, too, has more command of his horse, when forced up to the bit in a slow canter, than at any other pace.

Thoroughbred horses, until their education is complete, are apt to get very close to their fences, preferring, as it would seem, to go into them on this side rather than the other. It is not a style that inspires confidence; yet these crafty, careful creatures are safer than they seem, and from jumping in a collected form, with their hind-legs under them, extricate themselves with surprising address from difficulties that, after a little more tuition, they will never be in. They are really less afraid of their fences, and consequently less flurried, than the wilful, impetuous brute that loses its equanimity from the moment it catches sight of an obstacle, and miscalculating its distance, in sheer nervousness—most fatal error of all—takes off too soon.

I will now suppose that in the wake of your pilot you have negotiated two or three fences with some expenditure of nerve and temper, but without a refusal or a fall. The cutting-whip has been applied, and the result, perhaps, was disappointing, for it is an uncertain remedy, though, in my opinion, preferable to the spur. Your horse has shown great leaping powers in the distances he has covered without the momentum of speed, and has doubled an on-and-off with a precision not excelled by your leader himself. If he would but jump in his stride, you feel you have a hunter under you. Should the country be favourable, now is the time to teach him this accomplishment, while his limbs are supple and his spirit roused. If he seems willing to face them, let him take his fences in his own way; do not force or hurry him, but keep fast hold of his head without varying the pressure of hand or limb by a hairsbreadth; the least uncertainty of finger or inequality of seat will spoil it all. Should the ditch be towards him, he will jump from a stand, or nearly so, but, to your surprise, will land safe in the next field. If it is on the far side, he will show more confidence, and will perhaps swing over the whole with something of an effort in his canter. A foot or two of extra width may cause him to drop a hind-leg, or even bring him on his nose;—so much the better! no admonition of yours would have proved as effectual a warning—he will take good care to cover distance enough next time. Dispense with your leader now, if you are pretty close to the hounds, for your horse is gathering confidence with every stride. He can gallop, of course, and is good through dirt—it is also understood that he is fit to go; there are not many in a season, but let us suppose you have dropped into a run; if he carries you well to the finish, he will be a hunter from to-day.

After some five and twenty minutes, you will find him going with more dash and freedom, as his neighbours begin to tire. You may now ride him at timber without scruple, when not too high, but avoid a rail that looks as if it would break. To find out he may tamper with such an obstacle is the most dangerous discovery a hunter can make. You should send him at it pretty quick, lest he get too near to rise, and refuse at the last moment. He may not do it in the best of form, but whether he chances it in his gallop, or bucks over like a deer, or hoists himself sideways all in a heap, with his tail against your hat, at this kind of fence this kind of horse is most unlikely to fall.

The same may be said of a brook. If he is within a fair distance of the hounds, and you see by the expression of his ears and crest that he is watching them with ardent interest, ride him boldly at water should it be necessary. It is quite possible he may jump it in his stride from bank to bank, without a moment's hesitation. It is equally possible he may stop short on the bank, with lowered head and crouching quarters as if prepared to drink, or dive, or decline. He will do none of these. Sit still, give him his head, keep close into your saddle, not moving so much as an eyelash, and it is more than probable that he will jump the stream standing, and reach the other side, with a scramble and a flounder at the worst!

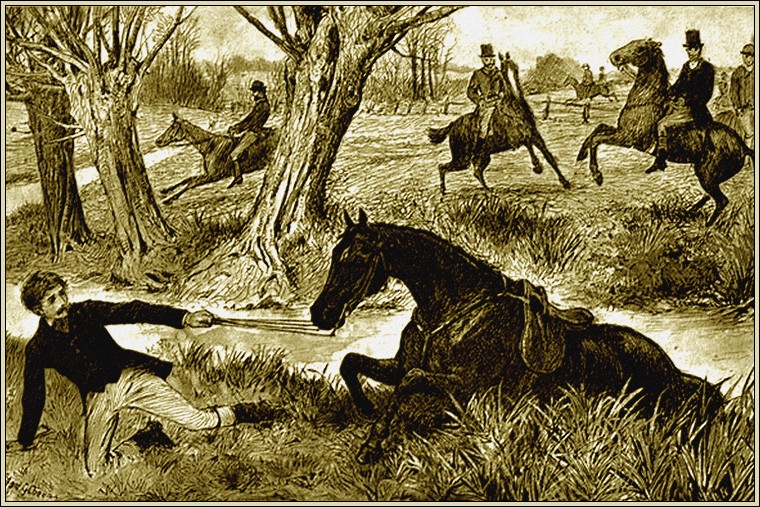

If he should drop his hind-legs, _shoot_ yourself off over his shoulders in an instant, with a fast hold of the bridle, at which tug hard; even though you may not have regained your legs. A very slight help now will enable him to extricate himself, but if he is allowed to subside into the gulf, it may take a team of cart horses to drag him out.

When in the saddle again give him a timely pull; after the struggle you will be delighted with each other, and have every prospect of going on triumphantly to the end.

If he should drop his hind legs, shoot yourself off over his shoulders...

I have here endeavoured to describe the different methods of coercion by which two opposite natures may be induced to exert themselves on our behalf in the chase. Every horse inclines, more or less, to one or other extreme I have cited as an example. A perfect hunter has preserved the good qualities of each without the faults, but how many perfect hunters do any of us ride in our lives? The chestnut is as fast as the wind, stout and honest, a safe and gallant fencer, but too light a mouth makes him difficult to handle at blind and cramped places; the bay can leap like a deer, and climb like a goat, invincible at doubles, and unrivalled at rails, but, as bold Lord Cardigan said of an equally accomplished animal, "it takes him a long time to get from one bit of timber to another!" While the brown, even faster than the chestnut, even safer than the bay, would be the best, as he is the pleasantest hunter in the world—only nothing will induce him to go near a brook!

It is only by exertion of a skill that is the embodiment of thought in action, by application of a science founded on reason, experience and analogy, that we can approach perfection in our noble four-footed friend. Common-sense will do much, kindness more, coercion very little, yet we are not to forget that man is the master; that the hand, however light, must be strong, the heel, however lively, must be resolute; and that when persuasion, best of all inducements, seems to fail, we must not shrink from the timely application of force.

The late Mr. Maxse, celebrated some fifty years ago for a fineness of hand that enabled him to cross Leicestershire with fewer falls than any other sportsman of fifteen stone who rode equally straight, used to profess much comical impatience with the insensibility of his servants to this useful quality. He was once seen explaining what he meant to his coachman with a silk-handkerchief passed round a post.

"Pull at it!" said the master. "Does it pull at you?"

"Yes, sir," answered the servant, grinning.

"Slack it off then. Does it pull at you now?"

"No, sir."

"Well then, you double-distilled fool, can't you see that your horses are like that post? If you don't pull at _them_ they won't pull at _you_!"

Now it seems to me that in riding and driving also, what we want to teach our horses is, that when we pull at them they are _not_ to pull at us, and this understanding is only to be attained by a delicacy of touch, a harmony of intention, and a give-and-take concord, that for lack of a better we express by the term "hand." Like the fingering of a pianoforte, this desirable quality seems rather a gift than an acquirement, and its rarity has no doubt given rise to the multiplicity of inventions with which man's ingenuity endeavours to supply the want of manual skill.

It was the theory of a celebrated Yorkshire sportsman, the well-known Mr. Fairfax, that "Every horse is a hunter if you don't throw him down with the bridle!" and I have always understood his style of riding was in perfect accordance with this daring profession of faith. The instrument, however, though no doubt producing ten falls, where it prevents one, is in so far a necessary evil, that we are helpless without it, and when skilfully used in conjunction with legs, knees, and body by a consummate horseman, would seem to convey the man's intentions to the beast through some subtle agency, mysterious and almost rapid as thought. It is impossible to define the nature of that sympathy which exists between a well-bitted horse and his rider, they seem actuated by a common impulse, and it is to promote or create this mutual understanding that so many remarkable conceits, generally painful, have been dignified with the name of bridles. In the saddle-room of any hunting-man may be found at least a dozen of these, but you will probably learn on inquiry, that three or four at most are all he keeps in use. It must be a stud of strangely-varying mouths and tempers which, the snaffle, gag, Pelham, and double-bridle are insufficient to humour and control.

As it seems from the oldest representations known of men on horseback, to have been the earliest in use, we will take the snaffle first.

This bit, the invention of common-sense going straight to its object, while lying easily on the tongue and bars of a horse's mouth, and affording control without pain, is perfection of its kind. It causes no annoyance and consequently no alarm to the unbroken colt, champing and churning freely at the new plaything between his jaws; on it the highly trained charger bears pleasantly and lightly, to "change his leg,"—"passage"—or "shoulder in," at the slightest inflection of a rider's hand; the hunter leans against it for support in deep ground; and the race-horse allows it to hold him together at nearly full-speed without contracting his stride, or by fighting with the restriction, wasting any of his gallop in the air. It answers its purpose admirably _so long as it remains in the proper place_, but not a moment longer. Directly a horse by sticking out his nose can shift this pressure to his lips and teeth, it affords no more control than a halter. With head up, and mouth open, he can go how and where he will. In such a predicament only an experienced horseman has the skill to give him such an amount of liberty without license as cajoles him into dropping again to his bridle, before he breaks away. Once off at speed, with the conviction that he is master, however ludicrous in appearance, the affair is serious enough in fact.

Many centuries elapsed, and a good deal of unpleasant riding must have been endured, before the snaffle was supplemented with a martingale. Judging from the Elgin Marbles, this useful invention seems to have been wholly unknown to the Greeks. Though the men's figures are perfect in seat and attitude through the whole of that spirited frieze which adorned the Parthenon, not one of their horses carries its head in the right place. The ancient Greek seems to have relied on strength rather than cunning, in his dealings with the noble animal, and though he sat down on it like a workman, must have found considerable difficulty in guiding his beast the way he wanted to go.

But with a martingale, the most insubordinate soon discover that they cannot rid themselves of control. It keeps their heads down in a position that enables the bit to act on the mouth, and if they must needs pull, obliges them to pull against that most sensitive part called the bars. There is no escape—bend their necks they must, and to bend their necks means to acknowledge a master and do homage to the rider's will.

It is a well-known fact, and I can attest it by my own experience, that a _twisted_ snaffle with a martingale will hold a runaway when every other bridle fails; but to guide or stop an animal by the exercise of bodily strength is not horsemanship, and to saw at its mouth for the purpose cannot be expected to promote that sympathy of desire and intention which we understand by the term.

If we look at the sporting prints of our grandfathers and great-grandfathers, as delineated, early in the present century, we observe that nine out of every ten hunters were ridden in plain snaffle bridles, and we ask ourselves if our progenitors bred more docile beasts, or were these drinkers of port wine, bolder, stronger, and better horsemen than their descendants. Without entering on the vexed question of comparative merit in hounds, hunters, pace, country and sport, at an interval of more than two generations, I think I can find a reason, and it seems to me simply this.

Most of these hunting pictures are representations of the chase in our midland counties, notably Leicestershire and Northamptonshire, then only partially inclosed; boundary fences of large properties were few and far between, straggling also, and ill-made-up, the high thorn hedges that now call forth so much bold and so much timid riding, either did not exist, or were of such tender growth as required protection by a low rail on each side, and a sportsman, with flying coat-tails, doubling these obstacles neatly, at his own pace, forms a favourite subject for the artist of the time. Twenty or thirty horsemen, at most, comprised the field; in such an expanse of free country there must have been plenty of room to ride, and we all know how soon a horse becomes amenable to control on a moor or an open down. The surface too was undrained, and a few furlongs bring the hardest puller to reason when he goes in over his fetlocks every stride. Hand and heel are the two great auxiliaries of the equestrian, but our grandfathers, I imagine, made less use of the bridle than the spur.

With increased facilities for locomotion, in the improvement of roads and coaches, hunting, always the English gentleman's favourite pastime, became a fashion for every one who could afford to keep a horse, and men thought little of twelve hours spent in the mail on a dark winter's night in order to meet hounds next day. The numbers attending a favourite fixture began to multiply, second horses were introduced, so that long before the use of railways scarlet coats mustered by tens as to-day by fifties, and the _crowd_, as it is called, became a recognized impediment to the enjoyments of the day.

Meantime fences were growing in height and thickness; an improved system of farming subdivided the fields and partitioned them off for pastoral or agricultural purposes; the hunter was called upon to collect himself, and jump at short notice, with a frequency that roused his mettle to the utmost, and this too in a rush of his fellow-creatures, urging, jostling, crossing him in the first five minutes at every turn.

Under such conditions it became indispensable to have him in perfect control, and that excellent invention, the double-bridle, came into general use.

I suppose I need hardly explain to my reader that it loses none of the advantages belonging to the snaffle, while it gains in the powerful leverage of the curb a restraint few horses are resolute enough to defy. In skilful hands, varying, yet harmonising, the manipulation of both, as a musician plays treble and bass on the pianoforte, it would seem to connect the rider's thought with the horse's movement, as if an electric chain passed through wrist, and finger, and mouth, from the head of the one to the heart of the other. The bearing and touch of this instrument can be so varied as to admit of a continual change in the degree of liberty and control, of that give-and-take which is the whole secret of comfortable progression. While the bridoon or snaffle-rein is tightened, the horse may stretch his neck to the utmost, without losing that confidence in the moral support of his rider's hand which is so encouraging to him if unaccompanied by pain. When the curb is brought into play, he bends his neck at its pressure to a position that brings his hind-legs under his own body and his rider's weight, from which collected form alone can his greatest efforts be made. Have your curb-bit sufficiently powerful, if not high in the _port_, at any rate long in the _cheek_, your bridoon as _thick_ as your saddler can be induced to send it. With the first you bring a horse's head into the right place, with the second, if smooth and _very_ thick, you keep it there, in perfect comfort to the animal, and consequently to yourself. A thin bridoon, and I have seen them mere wires, only cuts, chafes, and irritates, causing more pain and consequently more resistance, than the curb itself. I have already mentioned the fineness of Mr. Lovell's hand (alas! that he has but one), and I was induced by this gentleman to try a plan of his own invention, which, with his delicate manipulation, he found to be a success. Instead of the usual bridoon, he rode with a double strap of leather, exactly the width of a bridle-rein, and twice its thickness, resting where the snaffle ordinarily lies, on the horse's tongue and bars. With his touch it answered admirably, with mine, perhaps because I used the leather more roughly than the metal, it seemed the severer of the two. But a badly-broken horse, and half the hunters we ride have scarcely been taught their alphabet, will perhaps try to avoid the restraint of a curb by throwing his head up at the critical moment when you want to steady him for a difficulty. If you have a firm seat, perfectly independent of the bridle,—and do not be too sure of this, until you have tried the experiment of sitting a leap with nothing to hold on by—you may call in the assistance of the running-martingale, slipping your curb-rein, which should be made to unbuckle, through its rings. Your _curb_, I repeat, contrary to the usual practice, and _not your snaffle_. I will soon explain why.

The horse has so docile a nature, that he would always rather do right than wrong, if he can only be taught to distinguish one from the other; therefore, have all your restrictive power on the same engine. Directly he gives to your hand, by affording him more liberty you show him that he has met your wishes, and done what you asked. If you put the martingale on your bridoon rein you can no longer indicate approval. To avoid its control he must lean on the discomfort of his curb, and it puzzles no less than it discourages him, to find that every effort to please you is met, one way or the other, by restraint. So much for his convenience; now for your own. I will suppose you are using the common hunting martingale, attached to the breast-plate of your saddle, not to its girths. Be careful that the rings are too small to slip over those of the curb-bit; you will be in an awkward predicament if, after rising at a fence, your horse in the moment that he tries to extend himself finds his nose tied down to his knees.

Neither must you shorten it too much at first; rather accustom your pupil gradually to its restraint, and remember that all horses are not shaped alike; some are so formed that they must needs carry their heads higher, and, as you choose to think, in a worse place than others. Tuition in all its branches cannot be too gradual, and nature, whether of man or beast, is less easily driven than led. The first consideration in riding is, no doubt, to make our horses do what we desire; but when this elementary object has been gained, it is of great importance to our comfort that they should accept our wishes as their own, persuaded that they exert themselves voluntarily in the service of their riders. For this it is essential to use such a bridle as they do not fear to meet, yet feel unwilling to disobey. Many high-couraged horses, with sensitive mouths, no uncommon combination, and often united to those propelling powers in hocks and quarters that are so valuable to a hunter, while they scorn restraint by the mild influence of the snaffle, fight tumultuously against the galling restriction of a curb. For these the scion of a noble family, that has produced many fine riders, invented a bridle, combining, as its enemies declare, the defects of both, to which he has given his name.

In England there seems a very general prejudice against the Pelham, whereas in Ireland we see it in constant use. Like other bridles of a peculiar nature it is adapted for peculiar horses; and I have myself had three or four excellent hunters that would not be persuaded to go comfortably in anything else.

I need hardly explain the construction of a Pelham. It consists of a single bit, smooth and jointed, like a common snaffle, but prolonged from the rings on either side to a cheek, having a second rein attached, which acts, by means of a curb-chain round the lower jaw, in the same manner, though to a modified extent, as the curb-rein of the usual hunting double-bridle, to which it bears an outward resemblance, and of which it seems a mild and feeble imitation. I have never to this day made out whether or not a keen young sportsman was amusing himself at my expense, when, looking at my horse's head thus equipped, he asked the simple question: "Do you find it a good plan to have your snaffle and curb all in one?" I _did_ find it a good plan with that particular horse, and at the risk of appearing egotistical I will explain why, by narrating the circumstances under which I first discovered his merits, illustrating as they do the special advantages of this unpopular implement.

The animal in question, thoroughbred, and amongst hunters exceedingly speedy, was unused to jumping when I purchased him, and from his unaffected delight in their society, I imagine had never seen hounds. He was active, however, high-couraged, and only too willing to be in front; but with a nervous, excitable temperament, and every inclination to pull hard, he had also a highly sensitive mouth. The double-bridle in which he began his experiences annoyed him sadly; he bounced, fretted, made himself thoroughly disagreeable, and our first day was a pleasure to neither of us. Next time I bethought me of putting on a Pelham, and the effect of its greater liberty seemed so satisfactory that to enhance it, I took the curb-chain off altogether. I was in the act of pocketing the links, when a straight-necked fox broke covert, pointing for a beautiful grass country, and the hounds came pouring out with a burning scent, not five hundred yards from his brush. I remounted pretty quick, but my thoroughbred one—in racing language, "a good beginner"—was quicker yet, and my feet were hardly in the stirrups, ere he had settled to his stride, and was flying along in rather too close proximity to the pack. Happily, there was plenty of room, and the hounds ran unusually hard, for my horse fairly broke away with me in the first field, and although he allowed me by main force to steady him a little at his fences, during ten minutes at least I know who was _not_ master! He calmed, however, before the end of the burst, which was a very brilliant gallop, over a practicable country, and when I sent him home at two o'clock, I felt satisfied I had a game, good horse, that would soon make a capital hunter.

Now I am persuaded our timely _escapade_ was of the utmost service. It gave him confidence in his rider's hand; which, with this light Pelham bridle he found could inflict on him no pain, and only directed him the way he delighted to go. On his next appearance in the hunting-field, he was not afraid to submit to a little more restraint, and so by degrees, though I am bound to admit, the process took more than one season, he became a steady, temperate conveyance, answering the powerful conventional double-bridle with no less docility than the most sedate of his stable companions. We have seen a great deal of fun together since, but never such a game of romps as our first!

Why are so many brilliant horses difficult to ride? It ought not to be so. The truest shape entails the truest balance, consequently the smoothest paces and the best mouth. The fault is neither of form nor temper, but originates, if truth must be told, in the prejudices of the breaker, who will not vary his system to meet the requirements of different pupils. The best hunters have necessarily great power behind the saddle, causing them to move with their hind-legs so well under them, that they will not, and indeed cannot lean on the rider's hand. This the breaker calls "facing their bit," and the shyer they seem of that instrument, the harder he pulls. Up go their heads to avoid the pain, till that effort of self-defence becomes a habit, and it takes weeks of patience and fine horsemanship to undo the effects of unnecessary ill-usage for an hour.

Eastern horses, being broke from the first in the severest possible bits, all acquire this trick of throwing their noses in the air; but as they have never learned to pull, for the Oriental prides himself on riding with a "finger," you need only give them an easy bridle and a martingale to make them go quietly and pleasantly, with heads in the right place, delighted to find control not necessarily accompanied by pain.

And this indeed is the whole object of our numerous inventions. A light-mouthed horse steered by a good rider, will cross a country safely and satisfactorily in a Pelham bridle, with a running martingale on the _lower_ rein. It is only necessary to give him his head at his fences, that is to say, to let his mouth alone, the moment he leaves the ground. That the man he carries can hold a horse up, while landing, I believe to be a fallacy, that he gives him every chance in a difficulty by sitting well back and not interfering with his efforts to recover himself, I know to be a fact. The rider cannot keep too quiet till the last moment, when his own knee touches the ground, then, the sooner he parts company the better, turning his face towards his horse if possible, so as not to lose sight of the falling mass, and, above all, holding the bridle in his hand.

The last precaution cannot be insisted on too strongly. Not to mention the solecism of being afoot in boots and breeches during a run, and the cruel tax we inflict on some brother sportsman, who, being too good a fellow to leave us in the lurch, rides his own horse furlongs out of his line to go and catch ours, there is the further consideration of personal safety to life and limb. That is a very false position in which a man finds himself, when the animal is on its legs again, who cannot clear his foot from the stirrup, and has let his horse's head go!

I believe too that a tenacious grasp on the reins saves many a broken collar-bone, as it cants the rider's body round in the act of falling, so that the cushion of muscle behind it, rather than the point of his shoulder, is the first place to touch the ground; and no one who has ever been "pitched into" by a bigger boy at school can have forgotten that this part of the body takes punishment with the greatest impunity. But we are wandering from our subject. To hold on like grim death when down, seems an accomplishment little akin to the contents of a chapter professing to deal with the skilful use of the bridle.

The horse, except in peculiar cases, such as a stab with a sharp instrument, shrinks like other animals from pain. If he cannot avoid it in one way he will in another. When suffering under the pressure of his bit, he endeavours to escape the annoyance, according to the shape and setting on of his neck and shoulders, either by throwing his head up to the level of a rider's eyes, or dashing it down between his own knees. The latter is by far the most pernicious manoeuvre of the two, and to counteract it has been constructed the instrument we call "a gag."

This is neither more nor less than another snaffle bit of which the head-stall and rein, instead of being separately attached to the rings, are in one piece running through a swivel, so that a leverage is obtained on the side of the mouth of such power as forces the horse's head upwards to its proper level. In a gag and snaffle no horse can continue "boring," as it is termed against his rider's hand; in a gag and curb he is indeed a hard puller who will attempt to run away.

But with this bridle, adieu to all those delicacies of fingering which form the great charm of horsemanship, and are indeed the master touches of the art. A gag cannot be drawn gently through the mouth with hands parted and lowered on each side so as to "turn and wind a fiery Pegasus," nor is the bull-headed beast that requires it one on which, without long and patient tuition, you may hope to "witch the world with noble horsemanship." It is at best but a schoolmaster, and like the curbless Pelham in which my horse ran away with me, only a step in the right direction towards such willing obedience as we require. Something has been gained when our horse learns we have power to control him; much when he finds that power exerted for his own advantage.

I would ride mine in a chain-cable if by no other means I could make him understand that he must submit to my will, hoping always eventually to substitute for it a silken thread.

All bridles, by whatever names they may be called, are but the contrivances of a government that depends for authority on concealment of its weakness. Hard hands will inevitably make hard pullers, but to the animal intellect a force still untested is a force not lightly to be defied. The loose rein argues confidence, and even the brute understands that confidence is an attribute of power.

Change your bridle over and over again, till you find one that suits your hand, rather, I should say, that suits your horse's mouth. Do not, however, be too well satisfied with a first essay. He may go delightfully to-day in a bit that he will learn how to counteract by to-morrow. Nevertheless, a long step has been made in the right direction when he has carried you pleasantly if only for an hour. Should that period have been passed in following hounds, it is worth a whole week's education under less exciting conditions. A horse becomes best acquainted with his rider in those situations that call forth most care and circumspection from both.

Broken ground, fords, morasses, dark nights, all tend to mutual good understanding, but forty minutes over an inclosed country establishes the partnership of man and beast on such relations of confidence as much subsequent indiscretion fails to efface. The same excitement that rouses his courage seems to sharpen his faculties and clear his brain. It is wonderful how soon he begins to understand your meaning as conveyed literally from "hand to mouth," how cautiously he picks his steps amongst stubs or rabbit-holes, when the loosened rein warns him he must look out for himself, how boldly he quickens his stride and collects his energies for the fence he is approaching, when he feels grip and grasp tighten on back and bridle, conscious that you mean to "catch hold of his head and send him at it!" while loving you all the better for this energy of yours that stimulates his own.

And now we come to a question admitting of no little discussion, inasmuch as those practitioners differ widely who are best capable of forming an opinion. The advocates of the loose rein, who though outnumbered at the covert-side, are not always in a minority when the hounds run, maintain that a hunter never acquits himself so well as while let completely alone; their adversaries, on the other hand, protest that the first principle of equitation, is to keep fast hold of your horse's head at all times and under all circumstances. "You pull him into his fences," argues Finger. "_You_ will never pull him out of them," answers Fist. "Get into a bucket and try to lift yourself by the handles!" rejoins Finger, quoting from an apposite illustration of Colonel Greenwood's, as accomplished a horseman as his brother, also a colonel, whose fine handling I have already mentioned. "A horse isn't a bucket," returns Fist, triumphantly; "why, directly you let his head go does he stop in a race, refuse a brook, or stumble when tired on the road?"

It is a thousand pities that he cannot tell us which of the two systems he prefers himself. We may argue from theory, but can only judge by practice; and must draw our inferences rather from personal experience than the subtlest reasoning of the schools.

Now if all horses were broke by such masters of the art as General Lawrenson and Mr. Mackenzie Greaves, riders who combine the strength and freedom of the hunting field with the scientific exercise of hands and limbs, as taught in the _haute école_, so obedient would they become to our gestures, nay, to the inflection of our bodies, that they might be trusted over the strongest lordship in Leicestershire with their heads quite loose, or, for that matter, with no bridle at all. But equine education is usually conducted on a very different system to that of Monsieur Baucher, or either of the above-named gentlemen. From colthood horses have been taught to understand, paradoxically enough, that a dead pull against the jaws means, "Go on, and be hanged to you, till I alter the pressure as a hint for you to stop."

It certainly seems common sense, that when we tug at a horse's bridle he should oblige us by coming to a halt, yet, in his fast paces, we find the pull produces a precisely contrary effect; and for this habit, which during the process of breaking has become a second nature, we must make strong allowances, particularly in the hurry and excitement of crossing a country after a pack of hounds.

It has happened to most of us, no doubt, at some period to have owned a favourite, whose mouth was so fine, temper so perfect, courage so reliable, and who had so learned to accommodate pace and action to our lightest indications, that when thus mounted we felt we could go tit-tupping over a country with slackened rein and toe in stirrup, as if cantering in the Park. As we near our fence, a little more forbidding, perhaps, than common, every stride seems timed like clockwork, and, unwilling to interfere with such perfect mechanism, we drop our hand, trusting wholly in the honour of our horse. At the very last stride the traitor refuses, and whisks round. "_Et tu brute!_" we exclaim—"Are _you_ also a brute?"—and catching him vigorously by the head, we ram him again at the obstacle to fly over it like a bird. Early associations had prevailed, and our stanch friend disappointed us, not from cowardice, temper, nor incapacity, but only from the influence of an education based on principles contrary to common sense.

The great art of horsemanship, then, is to find out what the animal requires of us, and to meet its wishes, even its prejudices, half-way. Cool with the rash, and daring with the cautious, it is wise to retain the semblance, at least, of a self-possession superior to casualties, and equal to any emergency, from a refusal to a fall. Though "give and take" is the very first principle of handling, too sudden a variation of pressure has a tendency to confuse and flurry a hunter, whether in the gallop or when collecting itself for the leap. If you have been holding a horse hard by the head, to let him go in the last stride is very apt to make him run into his fence; while, if you have been riding with a light hand and loosened rein, a "chuck under the chin" at an inopportune moment distracts his attention, and causes him to drop short. "How did you get your fall?" is a common question in the hunting-field. If the partner at one end of the bridle could speak, how often would he answer, "Through bad riding;" when the partner at the other dishonestly replies, "The brute didn't jump high enough, or far enough, that was all." It is well for the most brilliant reputations that the noble animal is generous as he is brave, and silent as he is wise.

I have already observed there are many more kinds of bridles than those just mentioned. Major Dwyer's, notably, of which the principle is an exact fitting of bridoon and curb-bits to the horse's mouth, seems to give general satisfaction; and Lord Gardner, whose opinion none are likely to dispute, stamps it with his approval. I confess, however, to a preference for the old-fashioned double-bridles, such as are called respectively the Dunchurch, Nos. 1 and 2, being persuaded that these will meet the requirements of nine horses out of ten that have any business in the hunting-field. The first, very large, powerful, and of stronger leverage than the second, should be used with discretion, but, in good hands, is an instrument against which the most resolute puller, if he insists on fighting with it, must contend in vain. Thus tackled, and ridden by such a horseman as Mr. Angerstein, for instance, of Weeting, in Norfolk, I do not believe there are half-a-dozen hunters in England that could get the mastery. Whilst living in Northamptonshire I remember he owned a determined runaway, not inappropriately called "Hard Bargain," that in this bridle he could turn and twist like a pony. I have no doubt he has not forgotten the horse, nor a capital run from Misterton, in which, with his usual kindness, he lent him thus bridled to a friend.

I have seen horses go very pleasantly in what I believe is called the half-moon bit, of which the bridoon, having no joint, is shaped so as to take the curve of the animal's mouth. I have never tried one, but the idea seems good, as based on the principle of comfort to the horse. When we can arrive at that essential, combined with power to the rider, we may congratulate ourselves on possessing the right bridle at last, and need have no scruple in putting the animal to its best pace, confident we can stop it at will.

We should never forget that the faster hounds run, the more desirable is it to have perfect control of our conveyance; and that a hunter of very moderate speed, easy to turn, and quick on its legs, will cross a country with more expedition than a race-horse that requires half a field to "go about;" and that we dare not extend lest, "with too much way on," he should get completely out of our hand. Once past the gap you fancied, you will never find a place in the fence you like so well again.

"You may ride us,

With one soft kiss, a thousand furlongs, ere

With spurs we heat an acre."

Says Hermione, and indeed that gentle lady's illustration equally applies to an inferior order of beings, from which also man derives much comfort and delight. It will admit of discussion whether the "armed heel," with all its terrors, has not, on the race-course at least, lost more triumphs than it has won.

I have been told that Fordham, who seems to be first past the judges' chair oftener than any jockey of the day, wholly repudiates "the tormentors," arguing that they only make a horse shorten his stride, and "shut up," to use an expressive term, instead of struggling gallantly home. Judging by analogy, it is easy to conceive that such may be the case. The tendency of the human frame seems certainly to contract rather than expand its muscles, with instinctive repugnance at the stab of a sharp instrument, or even the puncture of a thorn. It is not while receiving punishment but administering it that the prize-fighter opens his shoulders and lets out. There is no doubt that many horses, thoroughbred ones especially, will stop suddenly, even in their gallop, and resent by kicking an indiscreet application of the spurs. A determined rider who keeps them screwed in the animal's flanks eventually gains the victory. But such triumphs of severity and main force are the last resource of an authority that ought never to be disputed, as springing less from fear than confidence and good-will.

It cannot be denied that there are many fools in the world, yet, regarding matters of opinion, the majority are generally right. A top-boot has an unfinished look without its appendage of shining steel; and, although some sportmen assure us they dispense with rowels, it is rare to find one so indifferent to appearances as not to wear spurs. There must be some good reason for this general adoption of an instrument that, from the days of chivalry, has been the very stamp and badge of a superiority which the man on horseback assumes over the man on foot. Let us weigh the arguments for and against this emblem of knighthood before we decide. In the riding-school, and particularly for military purposes, when the dragoon's right hand is required for his weapon, these aids, as they are called, seem to enhance that pressure of the leg which acts on the horse's quarters, as the rein on his forehand, bringing his whole body into the required position. Perhaps if the boot were totally unarmed much time might be lost in making his pupil understand the horseman's wishes, but any one who has ridden a perfectly trained charger knows how much more accurately it answers to the leg than the heel, and how awkwardly a horse acquits himself that has been broke in very sharp spurs; every touch causing it to wince and swerve too far in the required direction, glancing off at a tangent, like a boat that is over ready in answering her helm. Patience and a light switch, I believe, would fulfil all the purposes of the spur, even in the _manége_; but delay is doubtless a drawback, and there are reasons for going the shortest way on occasion, even if it be not the smoothest and the best.

It is quite unnecessary, however, and even prejudicial, to have the rowels long and sharp. Nothing impedes tuition like fear; and fear in the animal creation is the offspring of pain.

Granted, then, that the spur may be applied advantageously in the school, let us see how far it is useful on the road or in the hunting-field.

We will start by supposing that you do not possess a really perfect hack; that desirable animal must, doubtless, exist somewhere, but, like Pegasus, is more often talked of than seen. Nevertheless, the roadster that carries you to business or pleasure is a sound, active, useful beast, with safe, quick action, good shoulders, of course, and a willing disposition, particularly when turned towards home. How often in a week do you touch it with the spurs? Once, perhaps, by some bridle-gate, craftily hung at precisely the angle which prevents your reaching its latch or hasp. And what is the result of this little display of vexation? Your hack gets flurried, sticks his nose in the air, refuses to back, and compels you at last to open the gate with your wrong hand, rubbing your knee against the post as he pushes through in unseemly haste, for fear of another prod. When late for dinner, or hurrying home to outstrip the coming shower, you may fondly imagine that but for "the persuaders" you would have been drenched to the skin; and, relating your adventures at the fire-side, will probably declare that "you stuck the spurs into him the last mile, and came along as hard as he could drive." But, if you were to visit him in the stable, you would probably find his flanks untouched, and would, I am sure, be pleased rather than disappointed at the discovery. Happily, not one man in ten knows _how_ to spur a horse, and the tenth is often the most unwilling to administer so severe a punishment.

Ladies, however, are not so merciful. Perhaps because they have but one, they use this stimulant liberally, and without compunction. From their seat, and shortness of stirrup, every kick tells home. Concealed under a riding-habit, these vigorous applications are unsuspected by lookers-on; and the unwary wonder why, in the streets of London or the Park, a ladies' horse always appears to go in a lighter and livelier form than that of her male companion. "It's a woman's hand," says the admiring pedestrian. "Not a bit of it," answers the cynic who knows; "it's a woman's heel."

But, however sparing you may be of the spurs in lane or bridle-road, you are tempted to ply them far too freely in the anxiety and excitement of the hunting-field. Have you ever noticed the appearance of a white horse at the conclusion of some merry gallop over a strongly fenced country? The pure conspicuous colour tells sad tales, and the smooth, thin-skinned flanks are too often stained and plastered with red. Many bad horsemen spur their horses without meaning it; many worse, mean to spur their horses at every fence, and _do_.

A Leicestershire notability, of the last generation once dubbed a rival with the expressive title of "a hard funker;" and the term, so happily applied, fully rendered what he meant. Of all riders "the hard funker" is the most unmerciful to his beast; at every turn he uses his spurs cruelly, not because he is _hard_, but because he _funks_. Let us watch him crossing a country, observing his style as a warning rather than an example.