RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

RGL e-Book Cover 2017©

The All-Story Magazine, January 1909, with first part of "A Columbus of Space"

Amazing Stories, August 1926, with first part of "A Columbus of Space"

"A Columbus of Space," Appleton & Company, 1911

Not because the author flatters himself that he can walk in the Footsteps of that Immortal Dreamer, but because, like Jules Verne, he believes that the World of Imagination is as legitimate a Domain of the Human Mind as the World of Fact.

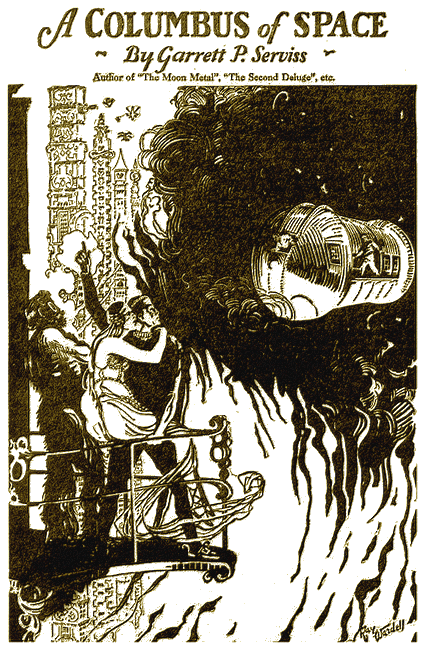

Frontispiece.

Standing on the steps was a creature shaped

like a man, but more savage than a gorilla.

I am a hero worshiper; an insatiable devourer of biographies; and I say that no man in all the splendid list ever equaled Edmund Stonewall. You smile because you have never heard his name, for, until now, his biography has not been written. And this is not truly a biography; it is only the story of the crowning event in Stonewall's career.

Really it humbles one's pride of race to see how ignorant the world is of its true heroes. Many a man who cuts a great figure in history is, after all, a poor specimen of humanity, slavishly following old ruts, destitute of any real originality, and remarkable only for some exaggeration of the commonplace. But in the case of Edmund Stonewall the world cannot be blamed for its ignorance, because, as I have already said, his story remains to be written, and hitherto it has been guarded as a profound secret.

I do not wish to exaggerate; yet I cannot avoid seeming to do so in simply telling the facts. If Stonewall's proceedings had become Matter of common knowledge the world would have been—I must speak plainly—revolutionized. He held in his hands the means of realizing the wildest dreams of power, wealth, and human mastery over the forces of nature, that any enthusiast ever treasured in his prophetic soul. It was a part of his originality that he never entertained the thought of employing his advantage in any such way. His character was entirely free from the ordinary forms of avidity. He cared nothing for wealth in itself, and as little for fame. All his energies were concentrated upon the attainment of ends which nobody but himself would have regarded as of any practical importance. Thus it happened that, having made an invention which would have put every human industry upon a new footing, and multiplied beyond the limits of calculation the activities and achievements of mankind, this extraordinary person turned his back upon the colossal fortune which he had but to stretch forth his hand and grasp, refused to seize the unlimited power which his genius had laid at his feet, and used his unparalleled discovery for a purpose so eccentric, so wildly unpractical, so utterly beyond the pale of waking life, that to any ordinary man he must have seemed a lunatic lost in an endless dream of bedlam. And to this day I cannot, without a nervous thrill, think how the desire of all the ages, the ideal that has been the loadstar for thousands of philosophers, savants, inventors, prophets, and dreamers, was actually realized upon the earth; and yet of all its fifteen hundred million inhabitants but a single one knew it, possessed it, controlled it—and he would not reveal it, but hoarded and used his knowledge for the accomplishment of the craziest design that ever took shape in a human brain.

Now, to be more specific. Of Stonewall's antecedents I know very little. I only know that, in a moderate way, he was wealthy, and that he had no immediate family ties. He was somewhere near thirty years of age, and held the diploma of one of our oldest universities. But he was not, in a general way, sociable, and I never knew him to attend any of the reunions of his former classmates, or to show the slightest interest in any of the events or functions of society, although its doors were open to him through some distant relatives who were widely connected in New York, and who at times tried to draw him into their circle. He would certainly have adorned it, but it had no attraction for him. Nevertheless he was a member of the Olympus Club, where he frequently spent his evenings. But he made very few acquaintances even there, and I believe that except myself, Jack Ashton, Henry Darton, and Will Church, he had no intimates. And we knew him only at the club. There, when he was alone with us, he sometimes partly opened up his mind, and we were charmed by his variety of knowledge and the singularity of his conversation. I shall not disguise the fact that we thought him extremely eccentric, although the idea of anything in the nature of insanity never entered our heads. We knew that he was engaged in recondite researches of a scientific nature, and that he possessed a private laboratory, although none of us had ever entered it. Occasionally he would speak of some new advance of science, throwing a flood of light by his clear expositions upon things of which we should otherwise have remained profoundly ignorant. His imagination flashed like lightning over the subject of his talk, revealing it at the most unexpected angles, and often he roused us to real enthusiasm for things the very names of which we almost forgot amidst the next day's occupations.

There was one subject on which he was particularly eloquent—radioactivity; that most strange property of matter whose discovery had been the crowning glory of science in the closing decade of the nineteenth century. None of us really knew anything about it except what Stonewall taught us. If some new incomprehensible announcement appeared in the newspapers we skipped it, being sure that Edmund would make it all clear at the club in the evening. He made us understand, in a dim way, that some vast, tremendous secret lay behind it all. I recall his saying, on one occasion, not long before the blow fell:

"Listen to this! Here's Professor Thomson declaring that a single grain of radium contains in its padlocked atoms energy enough to lift a million tons three hundred yards high. Professor Thomson is too modest in his estimates, and he hasn't the ghost of an idea how to get at that energy. Neither has Professor Rutherford, nor Lord Kelvin; but somebody will get at it, just the same."

He positively thrilled us when he spoke thus, for there was a look in his eyes which seemed to penetrate depths unfathomable to our intelligence. Yet we had not the faintest conception of what was really passing in his mind. If we had understood it, if we had caught a single clear glimpse of the workings of his intellect, we should have been appalled. And if we had known how close we stood to the verge of an abyss of mystery about to be lighted by such a gleam as had never before been emitted from the human spirit, I believe that we would have started from our chairs and fled in dismay.

But we understood nothing, except that Edmund was indulging in one of his eccentric dreams, and Jack, in his large, careless, good-natured way broke in with:

"Well, Edmund, suppose you could 'get at it,' as you say; what would you do with it?"

Stonewall's eyes gleamed for a moment, and then he replied, with a curious emphasis:

"I might do what Archimedes dreamed of."

None of us happened to remember what it was that Archimedes had dreamed, and the subject was dropped.

For a considerable time afterwards we saw nothing of Stonewall. He did not come to the club, and we were beginning to think of looking him up, when one evening, quite unexpectedly, he dropped in, wearing an unusually cheerful expression. We had greatly missed him, and we now greeted him with effusion. His animation impressed us all, and he had no sooner shaken hands than he said, with suppressed excitement in his voice:

"Well, I've 'got at it.'"

"Got at what?" drawled Jack.

"The inter-atomic energy. I've got it under control."

"The deuce you have!" said Jack.

"Yes, I've arrived where a certain professor dreamed of being when he averred that 'when man knows that every breath of air he draws has contained within itself force enough to drive the workshops of the world he will find out some day, somehow, some way of tapping that energy.' The thing is done, for I've tapped it!"

We stared at one another, not knowing what to say, except Jack, who, inspired by the spirit of mischief, drawled out:

"Ah, yes, I remember. Well then, Edmund, as I asked you before, what are you going to do with it?"

There was not really any thought among us of poking fun at Edmund; we respected and admired him far too much for that; nevertheless, catching the infection of banter from Jack, we united in demanding, in a manner which I can now see must have appeared most provoking:

"Why, yes, Edmund, tell us what you are going to do with it."

And then Jack added fuel by mockingly, though with perfectly good-natured intention, taking Edmund by the hand and swinging him in front of us with:

"Gentlemen, Archimedes junior."

Stonewall's eyes flashed and his cheek darkened, but for a moment he said nothing. Presently, with a return of his former affability, he said:

"I wish you would come over to the laboratory and let me show you what I am going to do."

Of course we instantly assented. Nothing could have pleased us better than this invitation, for we had long been dying to see the inside of Edmund's laboratory. We all got our hats and started out with him. We knew where he lived, occupying a whole house though he was a bachelor, but none of us had ever seen the inside of it, and our curiosity was on the qui vive. He led us through a handsome hallway and a rear apartment directly into the back yard, half of which we were surprised to find inclosed and roofed over, forming a huge shanty, like a workshop. Edmund opened the door of the shanty and ushered us in.

A remarkable object at once concentrated our attention. In the center of the place was the queerest-looking thing that you can well imagine. I can hardly describe it. It was round and elongated like a boiler, with bulging ends, and seemed to be made of polished steel. Its total length was about eighteen feet, and its width ten feet. Edmund approached it and opened a door in the end, which was wide and high enough for us to enter without stooping or crowding.

"Step in, gentlemen," he said, and unhesitatingly we obeyed him, all except Church, who for some unknown reason remained outside, and when we looked for him had disappeared.

Edmund turned on a bright light, and we found ourselves in an oblong chamber, beautifully fitted up with polished woodwork, and leather-cushioned seats running round the sides. Many metallic knobs and handles shone on the walls.

"Sit down," said Edmund, "and I will tell you what I have got here."

He stepped to the door and called again for Church but there was no answer. We concluded that, thinking the thing would be too deep to be interesting, he had gone back to the club. That was not what he had done, as you will learn later, but he never regretted what he did do. Getting no response from Church, Edmund finally sat down with us on one of the leather-covered benches, and began his explanation.

"As I was telling you at the club," he said, "I've solved the mystery of the atoms. I'm sure you'll excuse me from explaining my method" (there was a little raillery in his manner), "but at least you can understand the plain statement that I've got unlimited power at my command. These knobs and handles that you see are my keys for turning it on and off, and controlling it as I wish. Mark you, this power comes right out of the heart of what we call matter; the world is chock full of it. We have known that it was there at least ever since radioactivity was discovered, but it looked as though human intelligence would never be able to set it free from its prison. Nevertheless I have not only set it free, but I am able to control it as perfectly as if it were steam from a boiler, or an electric current from a dynamo."

Jack, who was as unscientific a person as ever lived, yawned, and Edmund noticed it. But he showed no irritation, merely smiling, and saying, with a wink at me and Henry:

"Even this seems to be rather too deep, so perhaps I had better show you, instead of telling you, what I mean. Excuse me a moment."

He stepped out of the door, and we remained seated. We heard a noise outside like the opening of a barn door, and immediately Edmund reappeared and closed the door of the chamber in which we were. We watched him with growing curiosity. With a singular smile he pressed a knob on the wall, and instantly we felt that the chamber was rising in the air. It rocked a little like a boat in wavy water. We were startled, of course, but not alarmed.

"Hello!" exclaimed Jack. "What kind of a balloon is this?"

"It's something more than a balloon," was Edmund's reply, and as he spoke he touched another knob, and we felt the car, as I must now call it, come to rest. Then Edmund opened a shutter at one side, and we all sprang up to look out. Below us we saw roofs and the tops of two trees standing at the side of the street.

"We're about a hundred feet up," said Edmund quietly. "What do you think of it now?"

"Wonderful! wonderful!" we exclaimed in a breath. And I continued:

"And do you say that it is inter-atomic energy that does this?"

"Nothing else in the world," returned Edmund.

But bantering Jack must have his quip:

"By the way, Edmund," he demanded, "what was it that Archimedes dreamed? But no matter; you've knocked him silly. Now, what are you going to do with your atomic balloon?"

Edmund's eyes flashed:

"You'll see in a minute."

The scene out of the window was beautiful, and for a moment we all remained watching it. The city lights were nearly all below our level, and away off over the New Jersey horizon I noticed the planet Venus, near to setting, but as brilliant as a diamond. I am fond of star-gazing, and I called Edmund's attention to the planet as he happened to be standing next to me.

"Lovely, isn't she?" he said with enthusiasm. "The finest world in the solar system, and what a strange thing that she should have one side always day and the other always night."

I was surprised by his exhibition of astronomic lore, for I had never known that he had given any attention to the subject, but a minute later the incident was forgotten as Edmund suddenly pushed us back from the window and closed the shutter.

"Going down again so soon?" asked Jack.

Edmund smiled. "Going," he said simply, and put his hand to one of the knobs. Immediately we felt ourselves moving very slowly.

"That's right, Edmund," put in Jack again, "let us down easy; I don't like bumps."

We expected at each instant to feel the car touch the cradle in which it had evidently rested, but never were three mortals so mistaken. What really did happen can better be described in the words of Will Church, who, you will remember, had disappeared at the beginning of our singular adventure. I got the account from him long afterwards. He had written it out carefully and put it away in a safe, as a sort of historic document. Here is Church's narrative, omitting the introduction, which read like a law paper:

"When we went over from the club to Stonewall's house, I dropped behind the others, because the four of them took up the whole width of the sidewalk. Stonewall was talking to them, and my attention was attracted by something uncommon in his manner. He had an indefinable carriage of the head which suggested to me the suspicion that everything was not just as it should be. I don't mean that I thought him crazy, or anything of that kind, but I felt that he had some scheme in his mind to fool us.

"I bitterly repented, after things turned out as they did, that I had not whispered a word to the others. But that would have been difficult, and, besides, I had no idea of the seriousness of the affair. Nevertheless, I determined to stay out of it, so that the laugh should not be on me at any rate. Accordingly when the others entered the car I stayed outside, and when Stonewall called me I did not answer.

"When he came out to open the roof of the shed, he did not see me in the shadow where I stood. The opening of the roof revealed the whole scheme in a flash. I had had no suspicion that the car was any kind of a balloon, and even after he had so significantly thrown the roof open, and then entered the car and closed the door, I was fairly amazed to see the thing began to rise without the slightest noise, and as if it were enchanted. It really looked diabolical as it floated silently upward and passed through the opening, and the sight gave me a shiver.

"But I was greatly relieved when it stopped at a height of a hundred feet or so, and then I said to myself that I should have been less of a fool if I had stayed with the others, for now they would have the laugh on me alone. Suddenly, while I watched, expecting every moment to see them drop down again, for I supposed that it was merely an experiment to show that the thing would float, the car started upward, very slowly at first, but increasing its speed until it had attained an elevation of perhaps five hundred feet. There it hung for a moment, like some mail-clad monster glinting in the quavering light of the street arcs, and then, without warning, made a dart skyward. For a minute it circled like a strange bird taking its bearings, and finally rushed off westward until I lost sight of it behind some tall buildings. I ran into the house to reach the street, but found the outer door locked, and not a person visible. I called but nobody came. Returning to the yard I discovered a place where I could get over the fence, and so I escaped into the street. Immediately I searched the sky for the mysterious car, but could see no sign of it. They were gone! I almost sank upon the pavement in a state of helpless excitement, which I could not have explained to myself if I had stopped to reason; for why, after all, should I take the thing so tragically. But something within me said that all was wrong. A policeman happened to pass.

"'Officer! officer!' I shouted, 'have you seen it?'

"'Seen what?' asked the blue-coat, twirling his club.

"'The car—the balloon,' I stammered.

"'Balloon in your head! You're drunk. Get long out o' here!'

"I realized the impossibility of explaining the matter to him, and running back to the place where I had got over the fence I climbed into the yard and entered the shed. Fortunately the policeman paid no further attention to my movements after I left him. I sat down on the empty cradle and stared up through the opening in the roof, hoping against hope to see them coming back. It must have been midnight before I gave up my vigil in despair, and went home, sorely puzzled, and blaming myself for having kept my suspicions unuttered. I finally got to sleep, but I had horrible dreams.

"The next day I was up early looking through all the papers in the hope of finding something about the car. But there was not a word. I watched the news columns for several days without result. Whenever the coast was clear I haunted Stonewall's yard, but the fatal shed yawned empty, and there was not a soul about the house. I cannot describe my feelings. My friends seemed to have been snatched away by some mysterious agency, and the horror of the thing almost drove me crazy. I felt that I was, in a manner, responsible for their disappearance.

"One day my heart sank at the sight of a cousin of Jack Ashton's motioning to me in the street. He approached, with a troubled look. 'Mr. Church,' he said, 'I think you know me; can you tell me what has become of Jack? I haven't seen him for several days.' What could I say? Still believing that they would soon come back, I invented, on the spur of the moment, a story that Jack, with a couple of intimate friends, had gone off on a hunting expedition. I took a little comfort in the reflection that my friends, like myself, were bachelors, and consequently at liberty to disappear if they chose.

"But when more than a week had passed with out any news of them I was thrown into despair. I had to give up all hope. Remembering how near we were to the coast, I concluded that they had drifted out over the sea and gone down. It was hard for me, after the lie I had told, to let out the truth to such of their friends as I knew, but I had to do it. Then the police took the matter in hand and ransacked Stonewall's laboratory and the shanty without finding anything to throw light on the mystery. It was a newspaper sensation for a few days, but as nothing came of it everybody soon forgot all about it—all except me. I was left to my loneliness and my regrets.

"A year has now passed with no news from them. I write this on the anniversary of their departure. My friends, I know, are dead—somewhere! Oh, what an experience it has been! When your friends die and are buried it is hard enough but when they disappear in a flash and leave no token—! It is almost beyond endurance!"

I take up the story at the point where I dropped it to introduce Church's narrative.

As minute after minute elapsed and we continued in motion we changed our minds about the descent, and concluded that the inventor was going to give us a much longer ride than we had anticipated. We were startled and puzzled but not really alarmed, for the car traveled so smoothly that it gave one a sense of confidence. On the other hand, we felt a little indignation that Edmund should treat us like a lot of boys, without wills of our own. No doubt we had provoked him, though unintentionally, but this was going too far on his part. I am sure we were all hot with this feeling and presently Jack flamed out:

"Look here, Edmund," he exclaimed, dropping his customary good-natured manner, "this is carrying things with a pretty high hand. It's a good deal like kidnapping, it seems to me. I didn't give you permission to carry me off in this way, and I want to know what you mean by it and what you are about. I've no objection to making a little trip in your car, which is certainly mighty comfortable, but first I'd like to be asked whether I want to go or no."

Edmund shrugged his shoulders and made no reply. He was very busy just then with the metallic knobs. Suddenly we were jerked off our feet as if we had been in a trolley driven by a green motorman. Edmund also would have fallen if he had not clung to one of the handles. We felt that we were spinning through the air at a fearful speed. Still Edmund uttered not a word, but while we staggered upon our feet, and steadied ourselves with hands and knees on the leather-cushioned benches like so many drunken men, he continued pulling and pushing at his knobs. Finally the motion became more regular and it was evident that the car had slowed down from its wild rush.

"Excuse me," said Edmund, then, quite in his natural manner, "the thing is new yet and I've got to learn the stops by experience. But there's no occasion for alarm."

But our indignation had grown hotter with the shake-up that we had just had, and as usual Jack was spokesman for it:

"Maybe there is no occasion for alarm," he said excitedly, "but will you be kind enough to answer my question, and tell us what you're about and where we are going?"

And Henry, too, who was ordinarily as mute as a clam, broke out still more hotly:

"See here! I've had enough of this thing! Just go down and let me out. I won't be carried off so, against my will and knowledge."

By this time Edmund appeared to have got things in the shape he wanted, and he turned to face us. He always had a magnetism that was inexplicable, and now we felt it as never before. His features were perfectly calm, but there was a light in his eyes that seemed electric. As if disdaining to make a direct reply to the heated words of Jack and Henry he began in a quiet voice:

"It was my first intention to invite you to accompany me on a very interesting expedition. I knew that none of you had any ties of family or business to detain you, and I felt sure that you would readily consent. In case you should not, however, I had made up my mind to go alone. But you provoked me more than you knew, probably, at the club, and after we had entered the car, and, being myself hot-tempered, I determined to teach you a lesson. I have no intention, however, of abducting you. It is true that you are in my power at present, but if you now say that you do not wish to be concerned in what I assure you will prove the most wonderful enterprise ever undertaken by human beings, I will go back to the shed and let you out."

We looked at one another, in doubt what to reply until Jack, who, with all his impulsiveness had more of the milk of human kindness in his heart than anyone else I ever knew, seized Edmund's hand and exclaimed:

"All right, old boy, bygones are bygones; I'm with you. Now what do you fellows say?"

"I'm with you, too," I cried, yielding to the spur of Jack's enthusiasm and moved also by an intense curiosity. "I say go ahead."

Henry was more backward. But his curiosity, too, was aroused, and at length he gave in his voice with the others.

Jack swung his hat.

"Three cheers, then, for the modern Archimedes! You won't take that amiss now Edmund."

We gave the cheers, and I could see that Edmund was immensely pleased.

"And now," Jack continued, "tell us all about it. Where are we going?"

"Pardon me, Jack," was Edmund's reply, "but I'd rather keep that for a surprise. You shall know everything in good time; or at least everything that you can understand," he added, with a slightly malicious smile.

Feeling a little more interest than the others, perhaps, in the scientific aspects of the business, I asked Edmund to tell us something more about the nature of his wonderful invention. He responded with great good humor, but rather in the manner of a schoolmaster addressing pupils who, he knows, cannot entirely follow him.

"These knobs and handles on the walls," he said, "control the driving power, which, as I have told you, comes from the atoms of matter which I have persuaded to unlock their hidden forces. I push or turn one way and we go ahead, or we rise; I push or turn another way and we stop, or go back. So I concentrate the atomic force just as I choose. It makes us go, or it carries us back to earth, or it holds us motionless, according to the way I apply it. The earth is what I kick against at present, and what I hold fast by; but any other sufficiently massive body would serve the same purpose. As to the machinery, you'd need a special education in order to understand it. You'd have to study the whole subject from the bottom up, and go through all the experiments that I have tried. I confess that there are some things the fundamental reason of which I don't understand myself. But I know how to apply and control the power, and if I had Professor Thomson and Professor Rutherford here, I'd make them open their eyes. I wish I had been able to kidnap them."

"That's a confession that, after all, you've kidnapped us," put in Jack, smiling.

"If you insist upon stating it in that way—yes," replied Edmund, smiling also. "But you know that now you've consented."

"Perhaps you'll treat us to a trip to Paris," Jack persisted.

"Better than that," was the reply. "Paris is only an ant-hill in comparison with what you are going to see."

And so, indeed, it turned out!

Finally all got out their pipes, and we began to make ourselves at home, for truly, as far as luxurious furniture was concerned, we were as comfortable as at the Olympus Club, and the motion of the strange craft was so smooth and regular that it soothed us like an anodyne. It was only those unnamed, subtle senses which man possesses almost without being aware of their existence that assured us that we were in motion at all.

After we had smoked for an hour or so, talking and telling stories quite in the manner of the club, Edmund suddenly asked, with a peculiar smile:

"Aren't you a little surprised that this small room is not choking full of smoke? You know that the shutters are tightly closed."

"By Jo," exclaimed Jack, "that's so! Why here we've been pouring out clouds like old Vesuvius for an hour with no windows open, and yet the air is as clear as a bell."

"The smoke," said Edmund impressively, "has been turned into atomic energy to speed us on our way. I'm glad you're all good smokers, for that saves me fuel. Look," he continued, while we, amazed, stared at him, "those fellows there have been swallowing your smoke, and glad to get it."

He pointed at a row of what seemed to be grinning steel mouths, barred with innumerable black teeth, and half concealed by a projecting ledge at the bottom of the wall opposite the entrance, and as I looked I was thrilled by the sight of faint curls of smoke disappearing within their gaping jaws.

"They are omnivorous beasts," said Edmund. "They feed on the carbon from your breath, too. Rather remarkable, isn't it, that every time you expel the air from your lungs you help this car to go?"

None of us knew what to say; our astonishment was beyond speech. We began to look askance at Edmund, with creeping sensations about the spine. A formless, unacknowledged fear of him entered our souls. It never occurred to us to doubt the truth of what he had said. We knew him too well for that; and, then, were we not here, flying mysteriously through the air in a heavy metallic car that had no apparent motive power? For my part, instead of demanding any further explanations, I fell into a hazy reverie on the marvel of it all; and Jack and Henry must have been seized the same way, for not one of us spoke a word, or asked a question; while Edmund, satisfied, perhaps, with the impression he had made, kept equally quiet.

Thus another hour passed, and all of us, I think, had fallen into a doze, when Edmund aroused us by saying:

"I'll have to keep the first watch, and all the others, too, this night."

"So then we're not going to land to-night?"

"No, not to-night, and you may as well turn in. You see that I have prepared good, comfortable bunks, and I think you'll make out very well."

As Edmund spoke he lifted the tops from some of the benches along the walls, and revealed excellent beds, ready for occupancy.

"I believe that I have forgotten nothing that we shall really need," he added. "Beds, arms, instruments, books, clothing, furs, and good things to eat."

Again we looked at one another in surprise, but nobody spoke, although the same thought probably occurred to each—that this promised to be a pretty long trip, judging from the preparations. Arms! What in the world should we need of arms? Was he going to the Rocky Mountains for a bear hunt? And clothing, and furs!

But we were really sleepy, and none of us was very long in taking Edmund at his word and leaving him to watch alone. He considerately drew a shade over the light, and then noiselessly opened a shutter and looked out. When I saw that, I was strongly tempted to rise and take a look myself, but instead I fell asleep. My dreams were disturbed by visions of the grinning nondescripts at the foot of the wall, which transformed themselves into winged dragons, and remorselessly pursued me through the measureless abysses of space.

When I woke, windows were open on both sides of the car, and brilliant sunshine was streaming in through one of them. Henry was still asleep, Jack was yawning in his bunk, and Edmund stood at one of the windows staring out. I made a quick toilet, and hastened to Edmund's side.

"Good morning," he said heartily, taking my hand. "Look out here, and tell me what you think of the prospect."

As I put my face close to the thick but very transparent glass covering the window, my heart jumped into my mouth!

"In Heaven's name, where are we?" I cried out.

Jack, hearing my agitated exclamation, jumped out of his bunk and ran to the window also. He gasped as he gazed out, and truly it was enough to take away one's breath!

We appeared to be at an infinite elevation, and the sky, as black as ink, was ablaze with stars, although the bright sunlight was streaming into the opposite window behind us. I could see nothing of the earth. Evidently we were too high for that.

Headpiece from Amazing Stories, August 1926

We appeared to be at an infinite elevation, and

the sky, as black as ink, was ablaze with stars.

"It must lie away down under our feet," I murmured half aloud, "so that even the horizon has sunk out of sight. Heavens, what a height!"

I had that queer uncontrollable qualm that comes to every one who finds himself suddenly on the edge of a soundless deep.

Presently I became aware that straight before us, but afar off, was a most singular appearance in the sky. At first glance I thought that it was a cloud, round and mottled, But it was strangely changeless in form, and it had an unvaporous look.

"Phew!" whistled Jack, suddenly catching sight of it and fixing his eyes in a stare, "what's that?"

"That's the earth!"

It was Edmund who spoke, looking at us with a quizzical smile. A shock ran through my nerves, and for an instant my brain whirled. I saw that it was the truth that he had uttered, for, as sure as I sit here, his words had hardly struck my ears when the great cloud rounded out and hardened, the deception vanished, and I recognized, as clearly as ever I saw them on a school globe, the outlines of Asia and the Pacific Ocean!

In a second I had become too weak to stand, and I sank trembling upon a bench. But Jack, whose eyes had not accommodated themselves as rapidly as mine to the gigantic perspective, remained at the window, exclaiming:

"Fiddlesticks! What are you trying to give us? The earth is down below, I reckon."

But in another minute he, too, saw it as it really was, and his astonishment equaled mine. In fact he made so much noise about it that he awoke Henry, who, jumping out of bed, came running to see, and when we had explained to him where we were, sank upon a seat with a despairing groan and covered his face. Our astonishment and dismay were too great to permit us quickly to recover our self-command, but after a while Jack seized Edmund's arm, and demanded:

"For God's sake, tell us what you've been doing."

"Nothing that ought to appear very extraordinary," answered Edmund, with uncommon warmth. "If men had not been fools for so many ages they might have done this, and more than this long ago. It's enough to make one ashamed of his race! For countless centuries, instead of grasping the power that nature had placed at the disposal of their intelligence, they have idled away their time gabbling about nothing. And even since, at last, they have begun to do something, look at the time that they have wasted upon such petty forces as steam and 'electricity,' burning whole mines of coal and whole lakes of oil, and childishly calling upon winds and tides and waterfalls to help them, when they had under their thumbs the limitless energy of the atoms, and no more understood it than a baby understands what makes its whistle scream! It's inter-atomic force that has brought us out here, and that is going to carry us a great deal farther."

We simply listened in silence; for what could we say? The facts were more eloquent than any words, and called for no commentary. Here we were, out in the middle of space; and there was the earth, hanging on nothing, like a summer cloud. At least we knew where we were if we didn't quite understand how we had got there.

Seeing us speechless, Edmund resumed in a different tone:

"We made a fairly good run during the night. You must be hungry by this time, for you've slept late; suppose we have breakfast."

So saying, he opened a locker, took out a folding table, covered it with a white cloth, turned on something resembling a little electric range, and in a few minutes had ready as appetizing a breakfast of eggs and as good a cup of coffee as I ever tasted. It is one of the compensations of human nature that it is able to adjust itself to the most unheard-of conditions provided only that the inner man is not neglected. The smell of breakfast would almost reconcile a man to purgatory—anyhow it reconciled us for the time being to our unparalleled situation, and we ate and drank, and indulged in as cheerful good comradeship as that of a fishing party in the wilderness after a big morning's catch.

When the breakfast was finished we began to chat and smoke, which reminded me of those gulping mouths under the wainscot, and I leaned down to catch a glimpse of their rows of black fangs, thinking to ask Edmund for further explanation about them; but the sight gave me a shiver, and I felt the hopelessness of trying to understand their function.

Then we took a turn at looking out of the window to see the earth. Edmund furnished us with binoculars which enabled us to recognize many geographical features of our planet. The western shore of the Pacific was now in plain sight, and a few small spots, near the edge of the ocean, we knew to be Japan and the Philippines. The snowy Himalayas showed as a crinkling line, and a huge white smudge over the China Sea indicated where a storm was raging and where good ships, no doubt, were battling with the tossing waves.

After a time I noticed that Edmund was continually going from one window to the other and looking out with an air of anxiety. He seemed to be watching for something, and there was a look of mingled expectation and apprehension in his eyes. He had a peephole at the forward end of the car and another in the floor, and these he frequently visited. I now recalled that even while we were at breakfast he had seemed uneasy and occasionally left his seat to look out. At last I asked him:

"What are you looking for, Edmund?"

"Meteors."

"Meteors, out here!"

"Of course. You're something of an astronomer; don't you know that they hang about all the planets? They didn't give me any rest last night. I was on tender hooks all the time while you were sleeping. I was half inclined to call one of you to help me. We passed some pretty ugly fellows while you slept, I can tell you! You know that this is an unexplored sea that we are navigating, and I don't want to run on the rocks."

"But we seem to be a good way off from the earth now," I remarked, "and there ought not to be much danger."

"It's not as dangerous as it was, but there may be some of them yet around here. I'll feel safer when we have put a few more million miles behind us."

A few more million miles! We all stood aghast when we heard the words. We had, indeed, imagined that the earth looked as if it might be a million miles away, but, then, it was merely a passing impression, which had given us no sense of reality; but now when we heard Edmund say that we actually had traveled such a distance, the idea struck us with overwhelming force.

"In the name of all that's good, Edmund," cried Jack, "at what rate are we traveling, then?"

"Just at present," Edmund replied, glancing at an indicator, "we're making twenty miles a second."

Twenty miles a second! Our excited nerves had another shock.

"Why," I exclaimed, "that's faster than the earth moves in its orbit!"

"Yes, a trifle faster; but I'll probably have to work up to a little better speed in order to get where I want to go before our goal begins to run away from us."

"Ah, there you are," said Jack. "That's what I wanted to know. What is our goal? Where are we going?"

Before Edmund could reply we all sprang to our feet in affright. A loud grating noise had broken upon our ears. At the same instant the car gave a lurch, and a blaze of the most vicious lightning streamed through a window.

"Confound the things!" shouted Edmund, springing to the window, and then darting to one of his knobs and beginning to twist it with all his force.

In a second we were sprawling on the floor—all except Edmund, who kept his hold on the knob. Our course had been changed with amazing quickness, and our startled eyes beheld a huge misshapen object darting past the window.

"Here comes another!" cried Edmund, again seizing the knob.

I had managed to get my face to the window, and I certainly thought that we were done for. Apparently only a few rods away, and rushing straight at the car, was a vast black mass, shaped something like a dumb-bell, with ends as big as houses, tumbling over and over, and threatening us with annihilation. If it hit us, as it seemed sure that it would do, I knew that we should never return to the earth, unless in the form of pulverized ashes!

But Edmund had seen the meteor sooner than I, and as quick as thought he swerved the car, and threw us all off our feet once more. But we should have been thankful if he had broken our heads, since he had saved us from instant destruction.

The danger, however, was not yet passed. Scarcely had the immense dumb-bell (which Edmund declared must have been composed of solid iron, so great was its effect on his needles) disappeared, before there came from outside a blaze so fierce that it fairly slapped our lids shut.

"A collision!" Edmund exclaimed. "The thing has struck another big meteor, and they are exchanging fiery compliments."

He threw himself flat on the floor, and stared out of the peephole. Then he jumped to his feet and gave us another tumble.

"They're all about us," he faltered, breathless with exertion; then, having drawn a deep inspiration, he continued: "We're like a boat in a raging freshet, with rocks, tree trunks, and cakes of ice threatening it on all sides. But we'll get out of it. The car obeys its helm as if it appreciated the danger. Why, I got away from that last fellow by setting up atomic reaction against it, as a boatman pushes with his pole."

Even in the midst of our terror we could not but admire our leader. His resources seemed boundless, and our confidence in him grew with every escape. While he kept guard at the peepholes we watched for meteors from the windows. We must have come almost within striking distance of a thousand in the course of an hour, but Edmund decided not to diminish our speed, for he said that he could control the car quicker when it was under full headway.

So on we rushed, dodging the things like a crow in a flock of pestering jays, and we really enjoyed the excitement. It was more fascinating sport than shooting rapids in a careening skiff, and at last we grew so confident in the powers of our car and its commander that we were rather sorry when the last meteor passed, and we found ourselves once more in open, unimpeded space.

After that the time passed quietly. We ate our meals and went to bed and rose as regularly as if we had been at home. In one respect, however, things were very different from what they were on the earth. We had no night! The sun shone continually, although the sky was black and always glittering with stars. None of us needed to be told by our conductor that this was due to the fact that we no longer had the shadow of the earth to make night for us when the sun was behind it. The sun was now never behind the earth, or any other great opaque body, and when we wished to sleep we made an artificial night, for our special use, by closing all the shutters. And there was no atmosphere about us to diffuse the sunlight, and so to hide the stars. We kept count of the days by the aid of a calendar clock; there seemed to be nothing that Edmund had forgotten. And it was a delightful experience, the wonder of which grew upon us hour by hour. It was too marvelous, too incredible, to be believed, and yet—there we were!

Once the idea suddenly came to me that it was astonishing that we had not long ago perished for lack of oxygen. I understood, of course, from what Edmund had said, that the mysterious machines along the wall absorbed the carbonic acid, but we must be constantly using up the oxygen. When I put my difficulty before Edmund he laughed.

"That's the easiest thing of all," he said. "Look here."

He threw open a little grating.

"In there," he continued, "there's an apparatus which manufactures just enough oxygen to keep the air in good condition. It is supplied with materials to last a month, which will be much longer than this expedition will take."

"There you are again," exclaimed Jack. "I was asking you about that when we ran into those pesky meteors. What is this expedition? Where are we going, anyway?"

"Well," Edmund replied, "since we have become pretty good shipmates, I don't see any objection to telling you. We are going to Venus."

"Going to Venus!" we all cried in a breath.

"To be sure. Why not? We've got the proper sort of conveyance, haven't we?"

There was no denying that. Our conveyance had already brought us some millions of miles out into space; why, indeed, should it not be able to carry us to Venus, or any other planet?

"How far is it to Venus?" asked Jack.

"When we quit the earth," Edmund answered, "Venus was rapidly approaching inferior conjunction. You know what that is," addressing me, "it's when the planet comes between the sun and the earth. The distance from the earth is not always the same at such a conjunction, but I figured out that on this occasion, after allowing for the circuit we should have to make, there would be just twenty-seven million miles to travel. At an average speed of twenty miles a second we could do that distance in fifteen days, fourteen and one half hours. But, of course, I had to lose some time going slow through the earth's atmosphere, for otherwise the car would have taken fire, like a meteor, on account of the friction. Then, too, I shall have to slow up on entering the atmosphere of Venus, which appears to be very deep and dense; so, upon the whole, I don't count on landing upon Venus in less than sixteen days from the time of our departure. We've already been out five days, and within eleven more I expect to introduce you to the inhabitants of another world."

The inhabitants of another world! Again Edmund had thrown out an idea which took us all aback.

"Do you believe there are any inhabitants on Venus?" I asked at length.

"Certainly. I know there are."

"For sure," put in Jack, stretching out his legs and pulling at his pipe. "Who'd go twenty-seven million miles to pay a visit if he didn't know there was somebody at home?"

"Then that's what you put the arms aboard for," I remarked.

"Yes, but I hope we shall not have to use them."

"Strikes me that this is a sort of pirate ship," said Jack. "But what kind of arms have you got, Edmund?"

For answer Edmund threw open a locker and showed us a gleaming array of automatic guns and pistols and even some cutlasses.

"Decidedly piratical!" exclaimed the incorrigible Jack. "You'd better hoist the black flag. But, see here, Edmund, with all this inter-atomic energy that you talk about, why in the world didn't you invent something new—something that would just knock the Venustians silly, and blow their old planet up if necessary? Automatic arms are pretty good at home, on that unprogressive earth that you have spurned with your heels, but they'll likely be rather small pumpkins on Venus."

"I didn't prepare anything else," Edmund replied, "because, in the first place, I was too busy with more important things, and in the second place because I don't really anticipate that we shall have any use for arms. I only took these as a precaution."

"You mean to try moral suasion, I suppose," drawled Jack. "Well, anyhow, I hope they'll be glad to see us, and since it is Venus that we are going to visit, I don't look for much fighting. I'm glad you made it Venus instead of Mars, Edmund, for, from all I've heard of Mars with its fourteen-foot giants, I don't think I should like to try the pirate business in that direction."

We all laughed at Jack's fancies; but there was something tremendously thrilling in the idea. Think of landing on another world! Think of meeting inhabitants there! Really, it made one's head spin.

"Confound it, this is all a dream," I said to myself. "I'm on my back in bed with a nightmare. I'll kick myself awake."

But do what I would I could make no dream of it. On the contrary, I felt that I had never been quite so much awake in all my life before.

After a while we all settled down to take the thing in earnest. And then the charm of it began to master our imaginations. We talked over the prospects in all their aspects. Edmund said little, and Henry nothing, but Jack and I were stirred to the bottom of our romantic souls. Henry was different. He had no romance in his make-up. He always looked at the money in a thing. To his mind, going to Venus was playing the fool, when we had at our command the means of owning the earth.

"Edmund," he said, after mumbling for a while under his breath, "this is the most utter tomfoolery that ever I heard of. Here you've got an invention that would revolutionize mechanics, and instead of utilizing it you rush off into space on a hairbrained adventure. You might have been twenty times a billionaire inside of a year if you had stayed at home and developed the thing. Why, it's folly; pure, beastly folly! Going to Venus! What can you make on Venus?"

Edmund only smiled. After a little he said:

"Well, I'm sorry for you, Henry. But then you're cut out on the ordinary pattern. But cheer up. When we go back, perhaps I'll let you take out a patent, and you can make the billions. For my part, Venus is more interesting to me than all the money you could pile up between the Atlantic Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. Why," he continued, warming up, and straightening with a certain pride which he had, "am I not the Columbus of Space?—And you my lieutenants," he added, with a smile.

"Right you are," cried Jack enthusiastically. "The Columbus of Space, that's the ticket! Where's old Archimedes now? Buried, by Jo! He couldn't go to Venus! And what need we care for your billionaires?"

Edmund patted Jack on the back, and I rather sympathized with his enthusiasm myself.

The time ran on, and we watched anxiously the day-hand of the calendar clock. Soon it had marked a week; then ten days; then a fortnight. We knew we must be getting very close to our goal, yet up to this time neither Jack, nor Henry, nor I had caught a glimpse of Venus. Edmund, however, had seen it, but he told us that in order to do so he had been obliged to alter our course because the planet was directly in the eye of the sun. In consequence of the change of course we were now approaching Venus from the east—flanking her, so to speak—and Edmund described her appearance as that of an enormous crescent. Finally he invited us to take a look for ourselves.

I shall never forget that first view! It was only a glimpse, for Edmund was nervous about meteors again, and would allow us only a moment at the peephole because he wished to be continually on the watch himself. But, brief as was the view, that vast gleaming sickle hanging in the black sky was the most tremendous thing I ever looked upon!

Soon afterwards Edmund changed the course again, and then we saw her no more. We had not come upon the swarms of meteors that Edmund had expected to find lurking about the planet, and he said that he now felt safe in running into her shadow, and making a landing on her night hemisphere. You will allow me to remind you that Schiaparelli had long before found out that Venus doesn't turn on her axis once every twenty-four hours, like the earth, but keeps always the same face to the sun; the consequence being that she has perpetual day on one side and perpetual night on the other. I asked Edmund why he should not rather land on the daylight side; but he replied that his plan was safer, and that we could easily go from one side to the other whenever we chose. It didn't turn out to be so easy after all, but that is another part of the story.

"I hardly expect to find any inhabitants on the night side," Edmund remarked, "for it must be fearfully cold there—too cold for life to exist, perhaps; but I have provided against that as far as we are concerned. Still, one can never tell. There may be inhabitants there, and at any rate I am going to find out. If there are none, we'll just stop long enough to take a look at things, and then the car will quickly transport us to the daylight hemisphere, where life certainly exists. By landing on the uninhabited side, you see, we shall have a chance to reconnoiter a little, and can approach the inhabitants on the other side so much the more safely."

"That sounds all right enough," said Jack, "but if Venus is correctly named, I'm for getting where the inhabitants are as quick as possible."

When we swung round into the shadow of the planet we got her between the sun and ourselves, and as she completely hid the sun, we now had perpetual night about the car. Out of the peephole she looked like a stupendous black circle, blacker than the sky itself, but round the rim was a beautiful ring of light.

"That's her atmosphere," Edmund explained, "lighted up by the sun from behind. But, for the life of me, I cannot tell what those immense flames mean."

He referred to a vast circle of many-colored spires that blazed and flickered like a burning rainbow at the inner edge of the ring of light. It was one of the most awful, and yet beautiful, sights that I had ever gazed upon.

"That's something altogether outside my calculations," Edmund added. "I can't account for it at all."

"Perhaps they are already celebrating our arrival with fireworks," suggested Jack, always ready to take the humorous view of everything.

"That's not fire," Edmund responded earnestly. "But what it is I confess I can't imagine. We'll find out, however, for I haven't come all this distance to be scared off."

And here I must try to explain a very curious thing which had puzzled our senses, though not our understanding (because Edmund had promptly explained it), throughout the voyage, and that was—levitation. On our first day out from the earth, we began to notice the remarkable ease with which we handled things, and the strange tendency we had to bump into one another because we seemed to be all the time employing more strength than was necessary and almost to be able to walk on air. Jack declared that he felt as if his head had become a toy balloon.

"It's the lack of weight," said Edmund. "Every time we double our distance from the earth we lose another three quarters of our weight. If I had thought to bring along a spring dynamometer, I could have shown you, Jack, that when we were 4,000 miles above the earth's surface the 200 good pounds with which you depress the scales at home had diminished to 50, and that when we had passed about 150,000 miles into space you weighed no more than a couple of ounces. From that point on, it has been the attraction of the sun to which we have owed whatever weight we had, and the floor of the car has been toward the sun, because, at that distance from the earth, the latter ceases to exercise the master force, and the pull of the sun becomes greater than the earth's. But as we approach Venus the latter begins to restore our weight, and when we arrive on her surface we shall weigh about four fifths as much as when we started from the earth."

"But I don't look as if I had lost any avoirdupois," said Jack, glancing at his round limbs. "And when you give us a fling I seem to strike pretty hard, though in other respects I confess I do feel a good deal like an angel."

"Ah," said Edmund, laughing, "that's the inertia of mass. Your mass is the same, although your weight has almost disappeared. Weight depends upon the distance from the attracting body, but mass is independent of everything."

"Do you mean to say that angels are massive?"

"They may be as massive as they like provided they keep well away from great centers of gravitation."

"But Venus is such a center—then there can't be any angels there."

"I hope to find something better than angels," was Edmund's smiling reply.

Now, as we drew near to Venus, the truth of Edmund's statements became apparent. We felt that our weight was returning, and our muscular activity sinking back to the normal again. We imagined that every minute we could feel our feet pressing more heavily upon the floor.

Our approach was so rapid that the immense black circle grew visibly minute by minute. Soon it was so large that we could no longer see its boundaries through the peephole in the floor.

"We're now within a thousand miles," said Edmund, "and must be close to the upper limits of the atmosphere. I'll have to slow down, or else we'll be burnt up by the heat of friction."

He proceeded to slow down a little more rapidly than was comfortable. It was jerk after jerk, as he dropped off the power, and put on the brakes, but at last we got down to the speed of a fast express train. Soon we were so close that the surface of the planet became dimly visible, simply from the starlight. We were now settling down very cautiously, and presently we began to notice curious shafts of light which appeared to issue from the ground, as if the surface beneath us had been sprinkled with iron founderies.

"Aha!" cried Edmund, "I believe there are inhabitants on this side after all. Those lights don't come from volcanoes. I'm going to make for the nearest one, and we'll soon know what they are."

Accordingly we steered for one of the gleaming shafts. It was a thrilling moment, I can tell you—that when we first saw another world than ours under our feet! As we approached the light it threw a pale illumination on the ground around. Everything appeared to be perfectly flat and level. It was like dropping down at night upon a vast prairie. But the features of the landscape were indistinguishable in the gloom. Edmund boldly continued to approach until we were within a hundred feet of the shaft of light, which we could now perceive issued directly from the ground. Suddenly, with the slightest perceptible bump, we touched the soil, and the car came to rest. We had landed on Venus!

"It's unquestionably frightfully cold outside," said Edmund, "and we'll now put on these things."

He dragged out of one of his many lockers four suits of thick fur garments, and as many pairs of fur gloves, together with caps and shields for the face, leaving only narrow openings for the eyes. When we had got them on we looked like so many Esquimaux. Finally Edmund handed each of us a pair of small automatic pistols, telling us to put them where they would be handy in our side pockets.

"Boarders all!" cried the irrepressible Jack. "Pirates, do your duty!"

Our preparations being made, we opened the door. The air that rushed in almost hardened us into icicles!

"It won't hurt you," said Edmund in a whisper. "It can't be down to absolute zero on account of the dense atmosphere. You'll get used to it in a few minutes. Come on."

His whispering gave us a sense of imminent danger, but nevertheless we followed as he led the way straight toward the shaft of light. On nearing it we saw that it came out of an irregularly round hole in the ground. When we got yet nearer we were astonished to see rough steps which led down into the pit. The next instant we were frozen in our tracks! For a moment my heart stopped beating.

Standing on the steps, just below the level of the ground, and intently watching us, with eyes as big and luminous as moons, was a creature shaped like a man, but more savage than a gorilla!

For two or three minutes the creature continued to stare at us, motionless; and we stared at him. It was so dramatic that it makes my nerves tingle now when I think of it. His eyes alone were enough to harrow up your soul. Huge beyond belief, round and luminous as full moons, they were filled with the phosphorescent greenish-yellow glare that sometimes appears in the expanded pupils of a cat or a wild beast. The great hairy head was black, but the stocky body was as white as a polar bear. The arms were apelike and very long and muscular, and the entire aspect of the creature betokened immense strength and activity.

Edmund was the first to recover from the stupor of surprise, and instantly he did a thing so apparently absurd but so marvelous in its calculated effect that no brain but his could have conceived it. It shakes me at once with laughter and recollected terror when I recall it.

"WELL, HELLO YOU!" he called out in a voice of such stentorian power that we jumped as at a thunderclap. The effect on the strange brute was electric. A film shot across the big eyes, he leaped into the air, uttering a squeak that was ridiculous, coming from an animal of such size and strength, and instantly disappeared, tumbling down the steps.

But we were as much frightened as the ugly monster himself. We stared at Edmund, speechless in our amazement. Never could I have believed it possible for such a voice to issue from the human throat. It was not the voice of our friend, nor the voice of a man at all, but an indescribable clangor; and the words I have quoted had been scarcely distinguishable, so shattered were they by the crash of sound that whirled them into our astonished ears. Edmund, seeing us gaping in speechless wonder, laughed with such an appearance of hearty enjoyment as I had never known him to exhibit—and his merriment produced another thunderous explosion that shook the air.

Then the truth burst upon me, and I exclaimed:

"It's the atmosphere!"

I had not spoken very loudly, but the words seemed to reverberate in my mouth, as if to testify to the correctness of my explanation.

"Yes," said Edmund, taking pains to moderate his voice, "you've hit it, it's the atmosphere. I had calculated on an effect of the kind, but the reality exceeds all that I had anticipated. Spectroscopic analysis as well as telescopic appearances demonstrated long ago that the atmosphere of Venus was extraordinarily extensive and dense, from which fact I inferred that we should encounter some wonderful acoustic phenomena here, and this was in my mind when, on stepping out of the car, I addressed you in a whisper. The reaction even of the whisper on my organs of speech told me that I was right, and showed me what to expect if the full power of the voice were used. When we caught sight of the creature at the top of the pit I had no desire to shoot him, and I saw that he was too powerful to be captured alive. In a second I had decided what to do. It ran through my mind that, in a world where the density, and probably something also in the peculiar constitution of the air, had the effect of vastly magnifying sound, the phonetic and acoustic organs of the inhabitants would be modified, and that the sounds uttered by them would be much fainter than those that we are accustomed to hear from living creatures on the earth. That being so, I argued that a very great and heavy sound coming from a strange animal would produce in the creature before us a paralyzing terror. You have seen that it did so. I expect that this will give us an immense advantage to begin with. We have already inspired so great a fear that I believe that we can now safely follow the creature into its habitation, and encounter without danger any of its congeners that may be there. Nevertheless, I shall not ask you to run any risks, and I will alone descend into the pit."

"If you do, may I be hanged for sheep stealing!"

You will guess at once that it was Jack who had spoken thus.

"No, sir," he continued, "if you go, we all go. Isn't that so, boys?"

In answer to an appeal thus put, neither Henry nor myself could have hung back even if we had had the disposition to do so. But I believe that we all instinctively felt that our place was by Edmund's side, wherever he might choose to go.

"Go ahead, then, Edmund," Jack added, seeing that we consented, "we're with you." And then his enthusiasm taking fire, as usual, he exclaimed: "Hurrah! Columbus forever! We've conquered a hemisphere with a blank shot."

And so we began our descent into the mysterious pit. The strange light that came from it, and formed a shaft in the dense atmosphere above like sunlight in a haymow, was accompanied by a considerable degree of heat, which was very grateful to our lungs after the frigid plunge that we had taken from the comfortable car. As we descended, the temperature continually rose until we were glad to throw off our Arctic togs, and leave them on a shelf of rock to await our return. But, fortunately, we did not forget to take the pistols from the pockets before leaving the garments. I am very uncertain what would have been the future course of our history if we had neglected this precaution.

It was an awful hole for depth. The steps, rudely cut, wound round and round the sides like those in a cathedral tower, but the pit was not perfectly circular. It looked like a natural formation, such as the vertical entrance to a limestone cavern, or the throat of a sleeping volcano. But whatever the nature of the pit might be, I was convinced that the steps were of artificial origin. They were reasonably regular in height and broad enough for two, or even three, persons to go abreast.

When we had descended perhaps as much as two hundred feet, we suddenly found ourselves in a broad cavern with a surprisingly level floor. The temperature had been steadily rising all the time, and here it was as warm as in an ordinary living room. The cavern appeared to be about twenty yards broad and eight or ten feet in height, with a flat roof of rock. It was dimly illuminated by a small heap of what seemed to be hard coal, burning in a very roughly constructed brazier, which, as far as looks went, one would have said was constructed of iron.

You will imagine our surprise upon seeing these things. The appearance of the gorilla-like beast with the awful eyes had certainly not led us to anticipate the finding in his lair of any such evidences of human intelligence, and we stood fast in our tracks for a minute or two, nobody speaking a word. Then Edmund said:

"This is far better than I hoped. I had not thought about caverns, though I ought to have foreseen the probability of something of the kind. It is hard to drive out life as long as a world has solid foundations, and air for breathing. I shall be greatly surprised now if these creatures do not turn out to be at least as intelligent as our African or Australian savages."

"But," said I, "the fellow that we saw surely cannot have more intelligence than a beast. There must be some more highly developed creatures living here."

"I'm not so sure of that," Edmund responded. "Looks go for nothing in such a case. He had arms and hands, and his brain may be well organized."

"If his brain is as big as his eyes," Jack put in, "he ought to be able to give odds to old Solomon and beat him easy. My, but I'd like to see their spectacles—if they ever wear any!"

Jack's humor recalled us from our meditation, and we began to look about more carefully. There was not a living creature in sight, but over in a corner I detected a broad hole, down which the steps continued to descend.

"Here's the way," said Edmund, discovering the steps at the same moment. "Down we go."

He again led the way, and we resumed the descent. As we stumbled along downward we began to talk of a strange but agreeable odor which we had noticed in the cavern. Edmund said that it was due, perhaps, to some peculiar quality of the atmosphere.

"I think," he continued, "that it is heavily charged with oxygen. You have noticed that none of us feels the slightest fatigue, notwithstanding the precipitancy of our long descent."

I reflected that this might also be the cause of our rising courage, for I was sure that not one of us felt the slightest fear in thus pushing on toward dangers of whose nature we could form no idea. The steps, precisely like those above, wound round and round and led us down I should say as much as three hundred feet before we entered another cavern, larger and loftier than the first.

And there we found them!

There was never another such sight! It made our blood run cold once more, rather with surprise than fear, though the latter quickly followed.

Ranged along the farther side of the cavern, and visible in the light of another glowing heap in the center, were as many as thirty of those huge hairy creatures, standing shoulder to shoulder, their great eyes glaring like bull's-eye lanterns. But the thing that filled us with terror was their motions.

You have read, with thrilling nerves, how a huge cobra, reared on his coils, sways his terrible head from side to side before striking. Well, all those black heads before us were swaying in unison, but with a sickening circular movement, which was regularly reversed in direction. Three times by the right and then three times by the left those heads circled, in rhythmic cadence, while the luminous eyes seemed to leave phosphorescent rings in the air, intersecting one another in consequence of the rapidity of the motion.

It was such a spectacle as I had never beheld in the wildest dream. It was baleful. It was the charm of the serpent fascinating his terrified prey. In an instant I felt my brain turning, and I staggered in spite of my utmost efforts. A kind of paralysis stiffened my limbs.

Presently, all moving together, and uttering a hissing, whistling sound, they began slowly to approach us, keeping in line, each shaggy leg lifted at the same moment, like so many soldiers on parade, while the heads continued to swing, and the glowing eyes to cut linked circles in the air. But for Edmund we should certainly have been lost. Standing a little to the fore, he spoke to us over his shoulder, in a low voice:

"Take out your pistols, but don't shoot unless they make a rush. Then kill as many as you can. I'll knock over the leader in the center, and I think that will be enough."

We could as easily have stirred our arms if we had been marble statues, but he promptly raised his pistol, and the explosion followed on the instant. The report was like an earthquake. It shocked us into our senses and almost out of them again. The weight of the air and the confinement of the cavern magnified and concentrated the sound so that it was awful beyond belief. The fellow in the center was hurled back as if shot from a catapult, and the others fell at flat as he, and lay there groveling, their big eyes filming and swaying, but no longer in unison.

The charm was broken, and as we saw our fearful enemies prostrate, our courage returned at a bound.

"I thought as much," said Edmund coolly. "But I'm sorry now that I aimed at that fellow; the sound alone would have sufficed. It was not necessary to take life. However, we should probably have had to come to it eventually, and now we have them thoroughly cowed. Our safety consists in keeping them terrified."

Thus speaking, Edmund boldly approached the groveling row, and pushed with his foot the furry body of the one he had shot. The bullet had gone through his head. At Edmund's approach the creatures sank lower on the rocky floor, and those nearest him turned up their moon eyes with an expression of submission and supplication that was grotesque. He motioned us to join him and, imitating him, we began to pat and smooth the shrinking bodies until, understanding that we would not hurt them, they gradually acquired confidence.

In the meantime the crowd in the cavern increased, others coming in through side passages, and exhibiting the utmost astonishment at the spectacle which greeted them. It was clear that those who had taken part in the opening scene imparted to the newcomers a knowledge of the situation of affairs, and we could see that our prestige was thoroughly established. It remained to utilize our advantage, and we looked to Edmund to show how it should be done. He was equal to the undertaking, but I shall not trouble you with the details of his diplomacy. Let it suffice to say that by a combination of gentleness and firmness he quickly reduced almost the entire population of the caverns (for, as we afterwards discovered, there were a dozen or more of these underground dwellings connected by horizontal passages through the rocks) into subjection to his will. I say "almost," because, as you will see in a little while, there were certain members of this extraordinary community who possessed a spirit of independence too strong to be so easily subdued.

As we became better acquainted with the cave dwellers we found that they were by no means as savage as they looked. Their appearance was certainly grotesque, and even unaccountable. Why, for instance, should their heads have been covered with coarse black disordered hair while their bodies, from the neck down, were almost beautiful with a natural raiment of golden white, as soft as silk and as brilliant as floss? I never could explain it, and Edmund was no less puzzled by this peculiarity. The immense size of their eyes did not seem astonishing after we began to reflect upon the consequences of the relative lack of light in their world. It was but a natural adjustment to their environment; with such eyes they could see in the dark better than cats. Their feet were bare and covered on the soles with thick soft skin, while the insides of their long hands were almost as white and delicate as those of a human being.

Their intelligence was sufficiently demonstrated by the construction of the hundreds of rocky steps leading from the caverns to the surface of the ground, and by their employment of fire, and manufacture of the metallic braziers which contained it. But this was not all. We found that in some of the winding passages connecting the caverns they cultivated food. It consisted entirely of vegetables of various kinds, and all unlike any that I ever saw on the earth. Water dripped from the roofs of these particular passages, and the almost colorless vegetation thrived there with astonishing luxuriance. They had many simple ways of cooking their food, and it was evident that they possessed some form of salt, though we did not discover the deposit from which they must have drawn it. They collected water in cisterns hollowed in the rock.

Although we still had abundance of food in the car, Edmund insisted on trying theirs, and it proved to be very palatable.

"This is fortunate, though hardly surprising," said Edmund. "If we had found the food on Venus uneatable, we should indeed have been in a fine fix. While we remain here we will eat as the natives eat, and save our own supplies for future need."

The only brute animals that we saw in the caverns were some doglike creatures, about as large as terriers, but very furry, which showed the utmost terror whenever we appeared.

One of the first things that we discovered outside the main cavern where we had made our debut was the burial ground of the community. This happened when they came to dispose of the fellow that Edmund had shot. They formed a regular procession, which greatly impressed us, and we followed them as they bore the body through several winding ways into a large cavern, at a considerable distance from any of the others. Here they had dug a grave, and, to our astonishment, there appeared to be something resembling a religious ceremony connected with the interment. And then, for the first time, we distinguished the females from the others. But a still greater surprise awaited us. It was no less than plain evidence of regular family relationship.

As the body was lowered into the grave one of the females approached with every sign of distress and sorrow. Jack declared that he saw tears running down her hairy cheeks. She held two little ones by the hand, and this spectacle produced an astonishing effect upon Edmund, revealing an entirely new side of his character. I have told you that he expressed regret for having killed the fellow in the cavern, but now, at the sight before him, he seemed filled with remorse.

"I wish I had never come here!" he said bitterly. "The first thing I have done is to kill an inoffensive and intelligent creature."

"Intelligent, perhaps," said Jack, "but inoffensive—not by a long shot! Where'd we have been if you hadn't killed him? They'd have made mincemeat of us."

"No," replied Edmund, sorrowfully shaking his head, "it wasn't necessary. The noise would have sufficed; and I ought to have known it."

"Why didn't you shout, then? That scared the first one," put in Henry, whose soul, it must be said, was not overflowing with sympathy.

"I did what I thought was best at the moment," Edmund replied, with a broken voice. "They were so many and so threatening that I imagined my voice alone might not be effective. But I'm sorry, sorry!"

"Henry, you're a fool!" cried the sympathetic Jack. "Come now, Edmund," he continued, kindly laying a hand on his shoulder, "what you did was the only thing under heaven that could have been done. You're wrong to blame yourself. By Jo, if you hadn't done it I would!"

But Edmund only shook his head, as if refusing to be comforted. It was the first sign of weakness that we had seen in our incomparable leader, but I am sure it only increased our respect for him—at least that's true of Jack and me. After that I noticed that Edmund was far more gentle than before in his relations with the people of the caverns.

Not long after this painful incident we made a discovery of extreme interest. It was nothing less than a big smithy! Edmund had foretold that we should find something of the kind.

"Those braziers and cooking pots," he had said, "and the tools that must have been needed to build the steps and to dig their graves, prove that they know how to work in iron. If it is not done in these caverns, then they get it from some other similar community. But I think it likely that we shall come upon some signs of the work hereabouts."

"Maybe they import it from Pittsburg," was the remark that fun-loving Jack could not refrain from making.

"Well, you'll see," said Edmund.

And, as I have already told you, he was right. We did find the smithy, with several stout fellows pounding out rude tools with equally rude hammers of iron. Of course we could ask them no questions, for their language was only a kind of squeak, and they seemed to converse mostly by means of expressive signs. But Edmund was not long in drawing his conclusions.