RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"Knaves of Diamonds," C. Arthur Simpson,

London, 1899

(with author's surname misspelt)

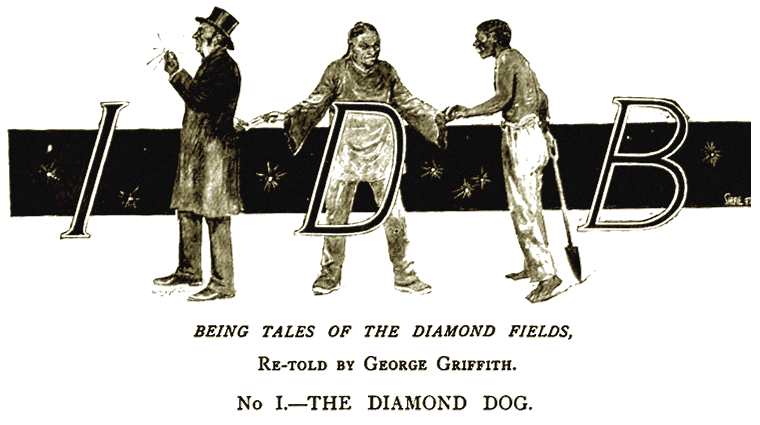

Headpiece from Pearson's Magazine

NEVER since men first began to risk health and life and honour for the sake of swift-won wealth have three characters of any alphabet been brought together which, in their combination, connoted, as the logicians say, so much as the three capitals "I.D.B." do, for in their internal meaning they include all the extremes and means of human fortune which may be imagined to lie between a life of luxury, and often of distinction, in which wealth makes wealth, till millions pile upon millions; and fifteen years' penal servitude on the Breakwater at Cape Town, which is the Portland of South Africa, with its semi-starvation and heart-breaking monotonous toil under the pitiless sub-tropical sun.

But between these two extremes there are many means, many chances for and against, together with an infinity of tricks and dodges, swindling of co-swindlers, and betrayal of brothers and sisters in iniquity, which make up the most fascinating array of temptations that ever made the broad and easy way which—sometimes—leadeth to destruction inviting to look upon and beguiling to tread.

The true import of these mystic and momentous letters may be explained better here than elsewhere. They have, in fact, two meanings—Illicit Diamond Buying, the crime specified in the various Diamond Acts, and the Illicit Diamond Buyer, one who buys "gonivahs" or stones which he knows to have been stolen or otherwise illicitly come by.

Now between him and the actual thief, the raw kaffir working in the mines, there may be as many as three or even four intermediaries, each of whom is guilty of the whole crime, and liable to the whole penalty thereof, for just that period during which the diamonds are in his or her possession and no longer, for, according to the Diamond Laws, the stones must be found on the person or in the possession of the suspect before a conviction can be obtained.

It is just here where the most exciting and fascinating part of the art and industry of I.D.B., when looked upon, as it usually was and is, as a gamble for very big stakes, comes in. There are, indeed, not a few who have found fortune in South Africa, and certain honours there and elsewhere, who can look back to anxious moments, big with fate, which made all the difference to them between the broadcloth of the millionaire magnate and the arrow-marked canvas of the convict I.D.B. Nay, more, as some of the stories which follow hereafter will truthfully tell, the doings of one fatal moment have more than once decided which of two men was to wear the broadcloth and which the canvas.

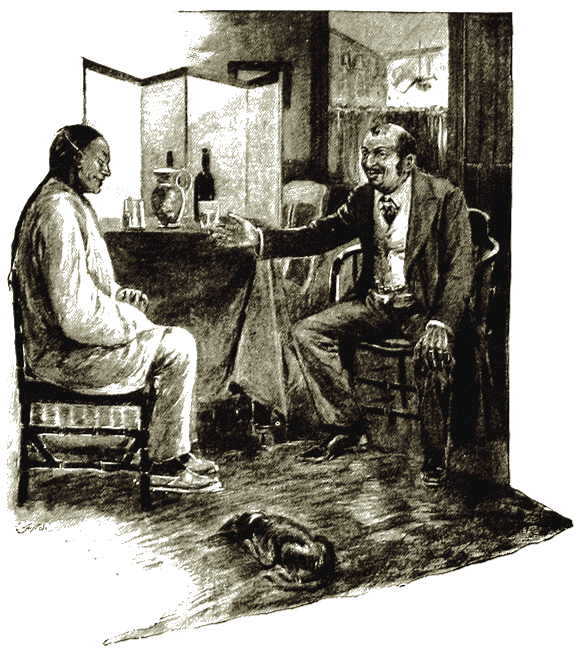

YOU might go far afield before you found two more queerly associated knights of industry than the Jew of Whitechapel and the Celestial of Singapore, who were sitting together over a bottle of brandy in a little back room behind a tin coolie store in Old De Beers Road, Kimberley, late one night in the early eighties. Yet it was no very uncommon thing here, in this vortex of cosmopolitan villainy into which the magical glitter of the diamond, more fatal in its fascination even than the glint of gold, had gathered together men of all colours and creeds from the remotest ends of the earth.

Something was evidently exercising the mind of the Jew very considerably, for his prominent eyes kept wandering restlessly about the little room, his fleshy, pendant under lip trembled every now and then with the movement of his heavy jaw, and his fat, lavishly-jewelled fingers kept alternately drumming on the dirty table and wandering aimlessly through his black and rather greasy locks.

The Chinaman sat with his long-nailed fingers entwined on the lap of his ample blouse, and looked at him placidly out of his bright, inward-slanting little eyes. Neither had said anything for some little time. Each was pondering a very important problem in his own way.

A shaggy, long-haired, disreputable-looking mongrel, which seemed to combine some half-dozen varying strains in his nondescript lineage, appeared to be doing the same thing as he lay on a frowzy sheepskin near the table, with his wickedly clever face between his paws, and every now and then he blinked up at his heathen master as though wondering whether he had found any solution to the problem yet.

"Itsh no good, Loo," half-whispered the Jew, at length breaking the pause, and bringing his fingers down from his hair to the table for something like the twentieth time, "the old plants will all be played out now that this infernal new law ish passed. The gonivahs will be harder to get than ever, and look at the rishk—fifteen years on that blathted breakwater just for being found with a few little klips on you! The game ain't going to be worth the candle any more, if we don't find some new way of getting them out that the tecs won't tumble to. It 'ud be worth a fortune to a man who could hit on a real bran' new fake just now, that it would, and if we can't get one, the industry's going to be ruined, and that's all there ish to it."

The Chinaman looked at him stolidly while he was speaking, and then, with a broad, wooden smile, which crinkled his eyes up into two little slits, he nodded his head after the fashion of one of his own idols, and said sententiously, and with the air of one who knows what he is talking about:

"All light, Missa Lonefelt, no need muchee scratch-head over dat. Kaffir boy plenty clever yet, allee same muchee searchee, no good. Plenty new fake, too. Dodgee tecman easy all same's before. You hab no got go workee yet, Missa Lonefelt."

"If you've thought of a good, new fake—one that'll work, mind, and that the tecs aren't likely to get on to for a bit, I'm the man to go shares with you on it, and I'll make it pay you well, Loo, I will, s'welp me.

"I've always treated you fair and square, haven't I?"

"I've always treated you fair and square, haven't I?"

"You know me, Loo, and we've done business together before now, and I've always treated you fair and square, haven't I? If it's a likely lay, it's worth twenty, no, I'll make it fifty, there, fifty down to let me into it, and the usual terms afterwards. That's good enough, ain't it? I can't speak no fairer than that, can I, Loo, old pal?" The Jew spoke eagerly, almost caressingly, to the yellow heathen whom he would have passed by without a wink in Main Street. There he was Augustus Löwenfeldt, licensed diamond broker, stock and share dealer, and all the rest of it, a man with a reputation to lose, as reputations went then in Kimberley, and with a future before him; but here in Loo Chai's back sitting-room he was just what the heathen was, neither better nor worse, an I.D.B., a "fence," as they would have called him in his native Whitechapel, and, like him, a potential felon, and so there was no need for any overstrained etiquette between them.

Added to this he knew that his "boys" must by this time be getting a very nice little collection of stones together for him, and he felt a very natural anxiety about them now that this detestable new law had about doubled both the legal power of search and the penalties for being found out.

Loo Chai's almond eyes wandered slowly from the dog to the Jew, and his head began to wag again, but this time the other way, and after a little pause he said slowly and meditatively:

"Fifty pound, and tlen per cent, not good enough dlis time, Missa Lonefelt, not by big heap. I hab got thought here"—and he tapped his shaven skull gently with one of his long nails—"which make velly big chop—tlen, twelve, maybe twenty t'ousand pound allee same time, and no chance catchee. Him worth pay for, eh, Missa Lonefelt?"

"Ten thousand at a go—maybe twenty," exclaimed the Jew, leaning forward with twitching lips, and eyes all a-glitter. "What's your price, Loo? Give it a name, and if I can meet you I will, s'welp me. You know I've always been fair and honourable with you."

"Me sell you one piecee doggie five hundled pounds."

As Loo Chai imparted this apparently irrelevant piece of information, he slowly waved one hand towards the mongrel on the sheepskin, and smiled blandly as he added: "And velly good chop, too, I tink."

"What! five hundred pounds for a bloomin' tyke, and a mighty ugly one at that. What's the good of pulling my leg like that when we're supposed to be talking strict business; what the blathes do I want with your dog?"

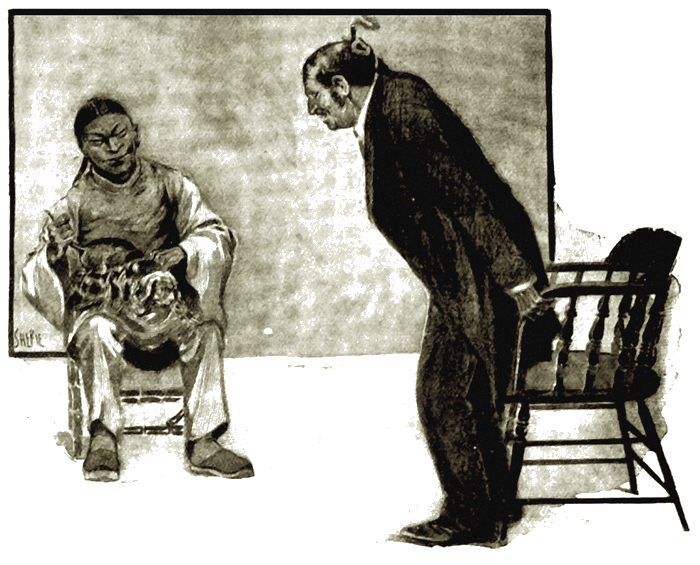

Mr. Löwenfeldt asked the question with an air of disgusted indignation, of which the placid heathen took not the slightest notice. He simply picked the cur up on to his lap and said, in a tone of calm and almost dignified reproof:

"Me no pullee leg by talkee bizness, Missa Lonefelt. Dis doggie no velly handsome, maybe, but he worth heap money allee same. Him what you call patent I.D.B. doggie. Now you watchee."

Mr. Augustus Löwenfeldt did watch, and that, too, with eyes which began to roll somewhat wildly to and fro before many moments had passed, for Loo Chai's deft fingers had by this time laid the thick, shaggy skin of the dog open from the base of the neck to the root of the tail. Then, putting one hand into the opening, and taking hold of the tail with the other, he gingerly drew out the hind quarters of one of those daintily-shaped hairless dogs which his countrymen mostly affect in the form of fricassee.

Putting one hand into the opening, and

taking hold of the tail with the other.

The covering of the head and shoulders was a fixture, a perfectly fitting and most ingeniously contrived mask, which it had cost Loo Chai some weeks of patient labour, and the animal a like period of not over-pleasant training to get and keep in position. But the hinder part was a miracle of that imitative ingenuity in which the Celestial excels all other workmen.

The delicate lacing along the back—where the hair of the original owner of the skin had been thickest, something after the fashion of an unkempt Skye terrier—was absolutely imperceptible when closed, and yet the inside of the skin was lined with marvellously contrived pockets, destined for small or large stones, accordingly as the inequalities of the animal's body or the length of the hair best afforded concealment. Loo Chai pointed them all out to the wondering Jew with a calm, and, in its way, justifiable pride, and when he had done, Mr. Löwenfeldt, who so far had not uttered any articulate sound, looked first at the half-naked dog and then at his own blandly smiling face and said very softly:

"Vell, I'm——!"

Loo Chai silently restored the dog to its original condition of disreputable curdom, kicked it on to the floor with a motion of his knee, and said quietly:

"Well, Missa Lonefelt, you no tink dat velly first chop I.D.B. doggie, eh?"

The immediate result of the somewhat animated conversation which followed Loo Chai's pertinent and business-like question, was the payment to him there and then of £250 in notes and gold, and the drawing of a bill for £250 more at sixty-five days on the Standard Bank at Cape Town. It was a big price to pay for a little dog, especially when considered in conjunction with a commission of ten per cent, on the possible future value of its skin, and the paying of it made all the heart that Mr. Löwenfeldt possessed ache for several days and nights with a pain which stimulated his normally keen wits to a really dangerous state of activity.

The Jew having thus paid his money, it was for the heathen to do the rest; and, as a first consequence of what he did, a Pondo kaffir, whom he had long had under his eye for the working out of this particular scheme, presented himself at the gate of the New Compound of the De Beers mine for hire early on the following morning but one.

He had a very disreputable-looking mongrel under his arm, and this, with only partially intelligible eloquence, he strenuously declined to be parted from.

He had a very disreputable-looking mongrel under his arm.

The officials objected, but the kaffir stuck to his point and his dog, and eventually carried both through, for the compound system was new and unpopular then, and native labour was very scarce, so at last, as he was turning away to offer his services elsewhere, he was called back and allowed to take his cur in, for he was a fine, athletic, likely-looking boy, and after all, if the dog gave any trouble, a fatal illness would not be a very difficult thing to arrange for. The Pondo proved to be an excellent workman, and so little was seen or heard of the dog that its existence was forgotten long before the usual two months' engagement was up. "Bymebye," as the kaffir called himself in accordance with the common custom of taking more or less grotesque English names, found plenty of old acquaintances in the compound, as both Loo Chai and Mr. Löwenfeldt had foreseen that he would, and, by virtue of sundry, invisible transactions between him and them, his dog improved rapidly in value, although its presence became even more unobtrusive than ever.

About ten days before young Bymebye's time was up, one of his most intimate friends left the compound after passing blamelessly through the then usual formalities under the hands of the searching officials, and that night contrived to convey, through Loo Chai and one Ah Foo, his servant, the welcome news to Mr. Löwenfeldt that the Pondo's dog would come out with such a lining to its second skin as the experienced broker felt justified in estimating at from ten to twelve thousand pounds in value.

The kaffir received five sovereigns in return for his news, and with them and his own earnings he proceeded, after the manner of his kind, to blind himself to the light of heaven and the lamps of divers bar-rooms for three days and nights, after which he went back with a light pouch and a heavy head to do another two months' spell in the mine. This time he was the bearer of a message to his Pondo chum to the effect that, if on his coming out he would take the dog to a certain place other than the house of Loo Chai, he would get £200 for it in place of the £100 that his master had promised him. To this the Pondo, being easy of morals and longing greatly for the possession of wives and cattle in his own land, incontinently consented.

The reason for this leading astray of the untutored savage may be quickly seen in the fact that ten per cent, on, say, £10,000 would be £1000, and this with the amount of the bill would make £1250—which, when Mr. Löwenfeldt came to think quietly over the matter, seemed to be a most outrageous price to pay to a yellow-skinned dog, and after due deliberation he decided not to pay it if he could find any means of evading payment.

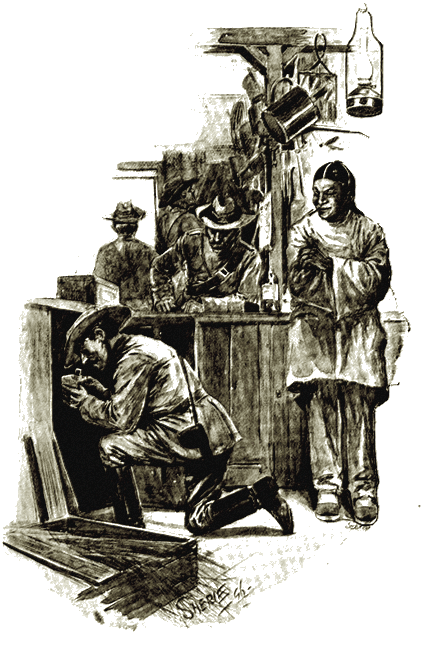

The shortest and easiest way to do this was to procure the arrest and conviction of Loo Chai as an I.D.B. before the Pondo got out, and to this end he succeeded in bribing Ah Foo with cash down and the promise of more to plant four "trap-stones," which he took from his own safe, in a convenient place in his master's store. But as there is more honour of a sort among heathens than among thieves, Ah Foo gave the plot away in the same hour, showed the trap-stones to Loo Chai, who had been expecting some friendly action of the sort, and, with his consent, took them away with him for greater safety and his own reward.

Very early the next morning the police, "acting on information received," raided the store of Loo Chai, turned it mostly into the street, and found nothing, its owner meanwhile looking on with a bland resignation that would have well become a martyr in a better cause. A good deal of language was used by the executors of the law of which no respectable printer's ink would convey any adequate impression, but it was nothing to the eloquent Yiddish in which Mr. Augustus Löwenfeldt relieved his feelings when he heard of the barren result of their labours.

The police raided the store of Loo Chai.

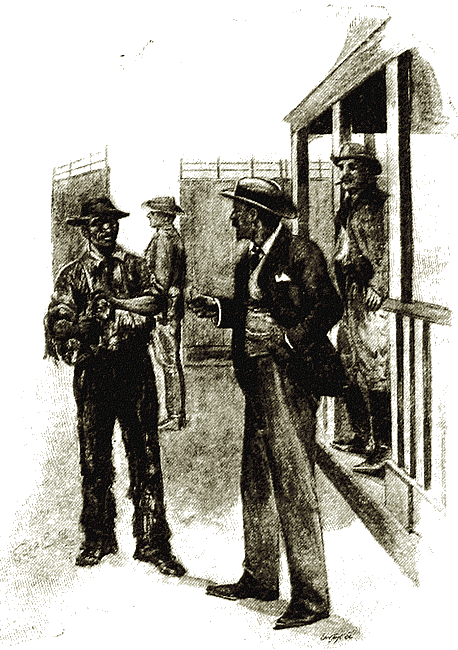

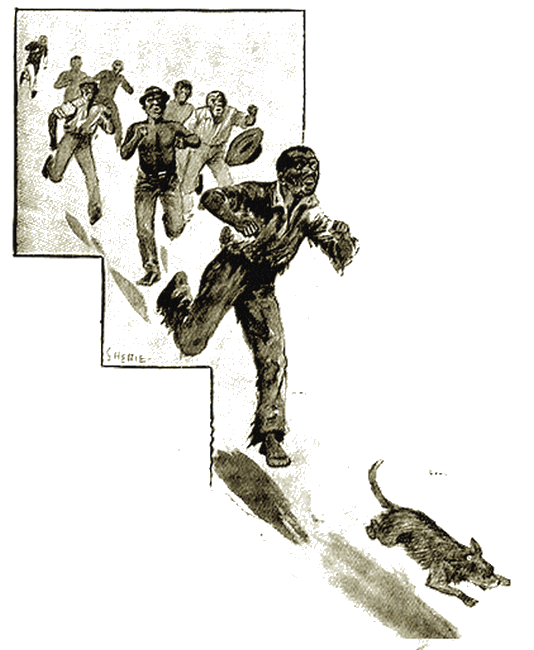

The next morning a somewhat unwonted scene was enacted outside the main gate of the De Beers Compound. Some thirty or forty kaffirs, whose time was up, and who had gone through the final formalities preceding dismissal, were coming out laughing and singing, and chattering, and jingling their hard-earned money like so many children, and among them, as innocently festive as any, was young Bymebye the Pondo. He was not carrying his dog this time. He knew that the officials had almost, if not entirely, forgotten its existence, and he wisely thought that it would be more prudent to let it sneak quietly out among the legs of the crowd than to recall it to the gatekeeper's memory by taking it in his arms.

The animal had become quite attached to him, and he made sure that he would be able to pick it up without any difficulty when he had got a safe distance from the gate. This he could have done quite easily if the dog had only been left to itself. But it wasn't.

No sooner had it passed the Rubicon almost unnoticed, and shown itself in the road, than a peculiar cry, something like a high tenor "coo-e-ee," rose shrilly into the still air from nowhere in particular. The heathen dog pricked up its false ears at the familiar but long unheard sound, and the next instant between ten and twelve thousand pounds worth of dog and diamonds was scampering down the road as fast as four wiry legs could carry it.

Bymebye let out a high-pitched howl of rage and horror, and started off with great, leaping strides in pursuit of the much longed-for wives and cattle and guns that were literally running away with the dog. The rest joined in the hue and cry, some for good reasons of their own, and some for the mere fun of the thing; but, unfortunately, just as they were beginning to gain on the flying treasure, a squad of mounted police, coming back from their night's duty on the Free State Border, turned a corner out of the Du Toits Pan Road at a trot, and barred their way.

Bymebye started off with great, leaping strides in pursuit.

The dog dodged in among the horses' legs and got clear away to the eager arms of Ah Foo, who was waiting for it in a half-ruined tin shanty about a hundred yards farther down the road. The police, always suspicious of anything like a kaffir émeute, ordered Bymebye and his companions to stop, but the Pondo and one or two of the others who knew the worth of the quarry, made a desperate effort to get through and continue the chase, with the result that they were speedily run down, collared, and marched off to the tronk—where, being able to give no satisfactory reasons for their anxiety to catch the dog, they were summarily fined five shillings each, and kicked out.

Almost at the same moment that they regained their liberty, an occurrence which the Diamond Fields Advertiser described the next morning as "a shocking tragedy" took place just outside the bar of the Central Hotel.

Mr. Augustus Löwenfeldt had been taking a few whiskies and sodas with some friends, and was just bidding them good-bye to go and see about some important business, when he happened to look across the street, and saw a well-dressed Chinaman walking up the opposite side with a hairless Chinese terrier at his heels.

Now there was, apparently, nothing in this to upset the equanimity of a respectable and substantial citizen of Diamondopolis, and yet his friends saw his hands spasmodically go up to his collar. His fat cheeks and low forehead suddenly became a deep bluish purple, and his eyes, bloodshot and staring, started half out of their sockets. Fumbling feebly with his fast tightening collar, he half gasped, half gurgled:

"Dog—ten thou'—done, by——" and then he reeled back and pitched sideways into the road, and before they could get him back into the bar, he was dead.

"Never knew poor Gussy to have 'em before," one of his friends sympathisingly remarked to another when they had seen the remains safely on to the ambulance. "D'you think there really was a dog there? Blethd if I did—the thing looked to me more like a rat. Come on, let's go and 'ave another, it's given me quite a turn."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.