RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"Knaves of Diamonds," C. Arthur Simpson,

London, 1899

(with author's surname misspelt)

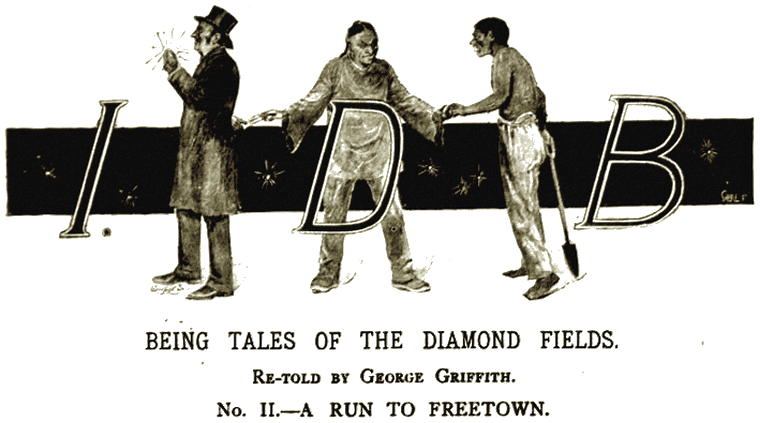

Headpiece from Pearson's Magazine

NEVER, perhaps, since thieving became one of the fine arts, have three characters of any alphabet been brought together, which, in their conjunction, are as eloquent in inner meaning as these are. They are colloquially used to denote both the crime and the criminal—Illicit Diamond Buying and the Illicit Diamond Buyer. Now the fascination of "I.D.B.," considered, as it usually is, as a gamble for very big stakes, consists mainly in the fact that, of the intermediaries who connect the kaffir thief in the mine with the "merchant" who exports the "Gonivahs," or stolen stones, to Europe, each is guilty of the whole crime and liable to the whole penalty for just that period during which the diamonds are in his or her possession and no longer, for once they are passed on it is almost impossible to trace them. There are, indeed, not a few who have found fortune in South Africa, and honours of a kind there and elsewhere, who can look back to anxious moments big with fate, which made all the difference to them between the broadcloth of the millionaire magnate and the arrow-marked canvas of the convict I.D.B. Nay, more, as some of these stories will truthfully tell, the doings of one fatal moment have ere now decided which of two equally guilty men was to wear the canvas and which the broadcloth.

IN the nature of the case it was quite out of the question that the story of the Diamond Dog should remain a secret for very long. To the I.D.B.'s, every detail of it, as it gradually leaked out, was as a sweet morsel under the tongue, and to many more honest enemies of the new compound system, mostly tradesmen and canteen-keepers, it was far too acceptable a tale either to be kept dark or to be allowed to lose anything in the re-telling.

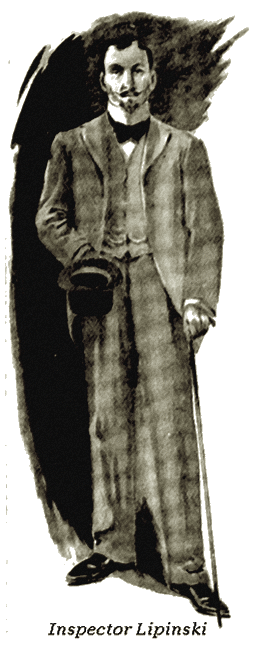

Added to this, the tragedy in which it had culminated had lent a piquancy to its flavour which sufficiently stimulated the palate of Kimberley society to set it longing for more, and so, little by little, it filtered through the barriers of official reticence, until at last a fitting finish was given to the story by the confession of Chief Detective-Inspector Lipinzki, one night in the smoking-room of the Club, that that day's mail had brought him a brief note, written by one Loo Chai, presumably a former resident of the Camp, from Delagoa Bay, requesting that an inclosed acceptance for £250, drawn in his favour by the late Mr. Augustus Löwenfeldt, might be cashed by that gentleman's executors, and the amount, less ten per cent, commission for his, the inspector's, trouble, forwarded at his convenience to No. 9 Malay Street, Singapore. The note concluded by stating that the £250 was a balance due from Mr. Löwenfeldt on the purchase of a certain dog of the estimated value of £11,000.

Despite the fact that not a few of those who heard the note read out, and looked at the acceptance as it was handed round, had lost some proportion of that £11,000, the irony of the note and the delicate humour of the address given—Malay Street, Singapore, having a reputation that is redolent throughout the whole East—provoked a laugh as general as it was hearty, and the next morning all Kimberley was enjoying the heathen's parting joke.

That night a lady variety vocalist at the Theatre Royal sent her audience into prolonged and vociferous raptures by singing the then famous patter-song, "Keyser, don't you vant to puy a tog?" with appropriate local allusions, and then Kimberley proceeded to improve the occasion in its own way.

A lady variety vocalist at the Theatre Royal.

"No dogs admitted!" was found painted in large black letters across the principal entrance to the De Beers Compound. The corpse of a large Newfoundland dog sewn up in the skin of a small donkey, and carefully packed in a neat case, was sent by coach from Vryburg to the Chief Inspector "to be paid for on delivery." Printed notices were stuck up in conspicuous parts of the town to the effect that in future all dogs entering or leaving Kimberley would have to be skinned alive "by authority"—and so on until the very sight of a dog in the street afflicted the worthy inspector and his subordinates with something like a new sort of rabies.

All this was humorous enough in its way, as humour went then in camp, but for all that it was destined to lead up, indirectly, to a much darker tragedy than that which had closed the hitherto prosperous career of Mr. Augustus Löwenfeldt.

There was at that time in Kimberley a Yankee adventurer named Seth Salter, who was known to the Detective Department as an even more skilful I.D.B. than the late lamented Löwenfeldt. His ostensible means of livelihood were stock and share speculations, billiards, and three-card monte, varied by the occasional keeping of a faro bank; but though he did well at all these comparatively honest vocations, he did not do well enough to satisfactorily account for a style of living and luxuriance of dissipation which could not be adequately supported on less than £5000 a year at the most modest computation. There were only two possible alternative hypotheses, debt or I.D.B., and he had no debts.

Now, Seth Salter was one of the most conspicuous of the humorists who, as he put it, made the Department see dogs instead of snakes when the officials thereof had "got a bit too full," and before very long, Inspector Lipinzki publicly stated in the bar of the Queen's Hotel that the next time Mr. Salter tried, either in person or by proxy, to run a parcel of illicit stones over the border to Freetown, he would so arrange matters that, by the time the circus was over, the said Mr. Salter would have good reason to wish that he had been born a dog, instead of a dirty, stock-rigging, card-swindling, diamond thief.

As it chanced, just as the inspector was emphasising the above statement, garnished with certain verbal frillings which need not be produced here, by slapping his four fingers on the bar counter, Mr. Seth himself lounged into the room. The instant turning of the eyes of the company on to him told him, as plainly as any words could have done, that he was the subject of the inspector's eloquence. The crowd saw at a glance that he had taken in the situation, and everyone expected a royal row, for Salter was known to have a temper as quick as his eye and his hand, and Lipinzki, though only about half the Yankee's size, was grit all through.

Nothing less than immediate manslaughter was looked for, and the crowd began to scatter instinctively. But, somewhat to the disappointment of the more festive spirits, Salter strolled quietly up to the bar, took his place about three feet from the inspector, and said, with the most perfect good humour:

"Evenin', boss! Don't seem to be feelin' quite good to-night. Hope no one's been tryin' to sell the Deepartment another pup? Take a drink?"

Of course the crowd laughed. The double-pointed jibe was irresistible, and the laugh did not improve the inspector's inward feelings. But he was far too well skilled in his business to show the slightest trace of irritation, so he replied with an easy smile and the most perfect politeness of tone:

"Ah, good-evening, Mr. Salter, I was just talking about you. No, thanks; the Department is not buying any dog-flesh just now, not even skins. As to your kind invitation, well, as I say, I was talking about you just now when you came in, and perhaps—"

If ever man uttered fighting words coolly, and as if he meant them, Inspector Lipinzki did just then. Seth Salter had never been known to take anything like that from any man without prompt and usually fatal reprisals. The crowd waited breathlessly, and silently scattered a little more. But no, the Yankee's hand did not even move towards his pistol pocket. There was just a little crinkling of the outer corners of his eyes, noticed only by the inspector and one or two others, but it vanished immediately, and there was no trace of anger in his voice—in fact, it seemed even more good-humoured than usual—as he replied:

"Don't take the trouble to say it again, boss. I've known your opinion of me for a long time, and now I've heard it. If you'd backed down you might have heard somethin' drop, but as you didn't, I'm free to say that I've too much respect for your honourable Deepartment to think of removing its respected chief to another, and, may be, less congenial sphere on account of an honestly expressed opinion—not me, sir! So now, N.G. and name the poison. Will you join us, gentlemen?"

The crowd joined as one man, and, under the circumstances, the inspector could do nothing less than come in with them. But for all that he felt a trifle puzzled, though he took care not to show it.

After that the conversation became general and perfectly amicable, albeit dwelling mainly on the somewhat ticklish subject which possessed the chief interest for everyone present. But as drinks multiplied and lies got more complicated, the inspector began to grow taciturn. Liquor has that effect on some natures, and his was possibly one of them. At last the Yankee rallied him, quite good-humouredly, on his lack of festivity, but rather unfortunately, as it seemed to the company, dragged in something about shortage on the mine returns. That was too much for the inspector, and his long bottled-up wrath suddenly flared out.

"Shortage, damn it, sir! You're a nice one to talk about shortage, Mr. Salter. You know as well as I do that there's about fifteen thousand short of a month's average on De Beers and Kimberley returns, and you know a big sight better than I do where the stones have gone to. But we'll have you yet. You're wide and you're deep, but you're not quite the cleverest man on earth, and when we do get you—"

"Well, why'n thunder don't you, boss?" the Yankee laughed, with still undisturbed good humour. "Say now, I'll give you a pointer, as them sneaks of yours don't seem to have got on to it yet. I'm going across to Freetown sometime between now and Sunday on a little private business of my own. S'pose, now, I was taking that bit of shortage with me—what'll you lay against me getting it through?"

"Ten years on the Breakwater!" snapped the inspector, as he emptied his glass, and set it down with a bang on the counter.

"No, you don't," laughed Salter; "that's for me to lay. Now, look here, I'll lay you ten years on the Breakwater to a thousand pounds—that's only a hundred a year, and I think my time's a darned sight more valuable than that, so I'm giving you big odds—that I'll take that little lot through for all you can do to stop me."

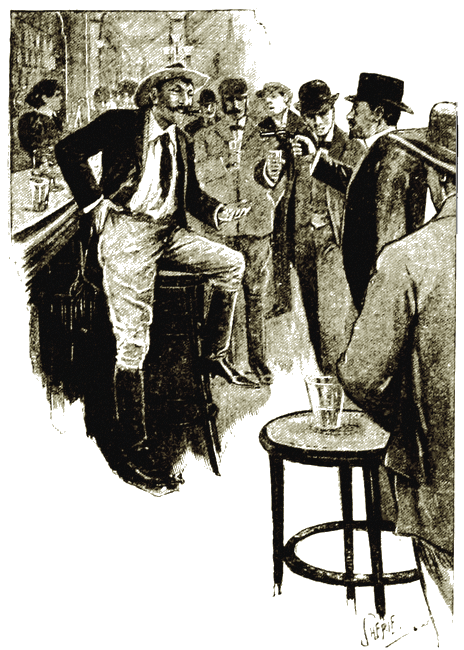

As he spoke, he suddenly pulled his left hand out of his trousers pocket, and held it out to the inspector with the palm full of rough diamonds.

Lipinzki fairly gaped at the heap of glittering stones, but he lost neither his presence of mind nor his professional promptitude. Like lightning, a revolver jumped out of his coat pocket, and as he covered the Yankee's heart with the muzzle, he said sharply:

"That bluff won't work, Mr. Salter. I'll see your hand for a thousand now. If you don't want a sudden death in your family, come along to the office, and account for the possession of those diamonds."

"I'll see your hand for a thousand now."

To the added amazement of everyone in the room, Seth Salter burst into a loud laugh, and said, without moving out of the line of fire:

"Waal, boss, I did think you had a better eye for klips than that. D'you fancy I'd be such an almighty sucker as to—good Lord, man, can't you see they're all schlenters? There's no law agin carrying them round, I reckon. Here, take 'em, and see for yourself. There's plenty of good judges in the room to help you."

A very brief examination satisfied the disgusted inspector that the astute Yankee had once more turned the laugh against him.

"I'll see your hand for a thousand now."

The things were "schlenters," or "snyde diamonds"—imitations made of glass treated with fluoric acid to give them the peculiar frosted appearance of the real rough stones—which were used chiefly for the purpose of swindling the new chums and greenhorns who were making their first essays in I.D.B.

Lipinzki saw that he had "done him a shot in the eye," as the camp vernacular had it, and put up his revolver with what grace he could. The Yankee took his little triumph very quietly, and asked the young lady behind the bar to oblige him with a sheet of note-paper and an envelope. Then he wrapped up the false stones, put them into the envelope, stuck it down, and asked the inspector to write his name across the flap, which he did, with a peculiar smile on his well-shaped lips.

"Waal, now, that's a bet, eh?" said Salter, as he put the packet in his pocket. "Now let's take another drink on it and then go home. It's gettin' late and I've got to pack. There's no knowin' how soon I might have to start."

The glasses were filled again, and the Yankee clinked his against the inspector's with as much cordiality as though they had been the best of friends, instead of, as they were now, hunter and quarry in a chase to the death.

The next day Seth Salter openly hired a Cape cart and team of four horses to take him to Bloemfontein, which is about eighty miles by road from Kimberley, and when the bargain was struck, he privately informed the driver, an off-coloured Cape boy who had made more than one run of the kind, that if he would start at midnight instead of midday, and go via Freetown instead of Boshoff, he should have £100 for that part of the journey alone, which was not a bad fare for a drive of less than an hour. The boy jumped at the offer, and within a couple of hours had accepted one of twice the amount, with half cash down, from Inspector Lipinzki, to pull up at a certain spot about 400 yards from the Free State border.

That afternoon Salter and Lipinzki met, as if by chance, in the private bar of the Central, had a whisky and soda together, and talked over the journey with apparently perfect friendliness and freedom. The inspector affected to treat the whole thing as a joke, a bit of spoof that he was far too wary a bird to be taken in by.

It wasn't likely that such an old hand as Salter would try to run anything but the schlenters, after giving himself away as completely as he had done, at least, not that time. Some other time, perhaps, and then he'd see. At the same time, it might after all be a clever and daring game of bluff, and so it would be as well to take precautions.

Altogether it was an interesting situation, especially for the inspector. If he caught Salter with nothing but the schlenters on him, he would be the laughing-stock of the camp, and if he let him go through with something like a £15,000 packet of diamonds—which he felt perfectly certain he had planted somewhere—his reputation would be ruined and his dismissal certain. It was a desperate game, and Inspector Lipinzki was prepared to take desperate measures to win.

A little before noon, Salter changed his plans, and said he would go the next day, and a few minutes before midnight he got into his cart just outside Beaconsfield. The boy whipped up his team, and the cart rattled and jolted away at a quick trot towards the border. The night was too fine, in fact, and as they spun along mile after mile without let or hindrance, Salter began to think that, after all, Lipinzki had funked the trap that he had laid for him, and decided to risk letting the diamonds through rather than make a fool of himself by the capture of a lot of worthless schlenters.

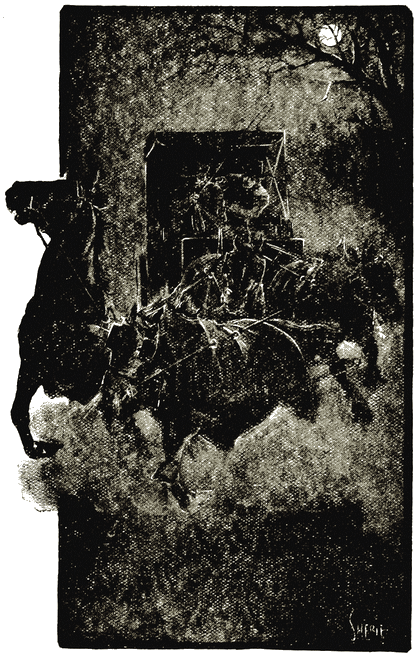

The lights of Freetown were already glimmering in the distance across the veld. Ten minutes more would see him safe over the border with the most valuable packet of diamonds that had ever been run out of camp, and then—suddenly his strained ears caught the sound of a voice in the distance, followed by the clinking of horses' bits and the ominous "click-click" of rifle locks.

He was sitting, as usual, on the seat behind the driver, and just as the boy turned round and whispered in a frightened way: "P'lice, baas, better pull up, eh? might get shot," he pointed his revolver at him, and said in a low but very business-like tone:

"You yellow swine, you've sold me! Now you whip them horses up, and make 'em go for all they're worth. By thunder, you shall drive to Freetown or Glory to-night, for if I see you pull those reins, I'll blow the top of your ugly head off, just so sure as you'll never see the other side of Jordan. Whip up now! You've got to get through or go home, I tell you."

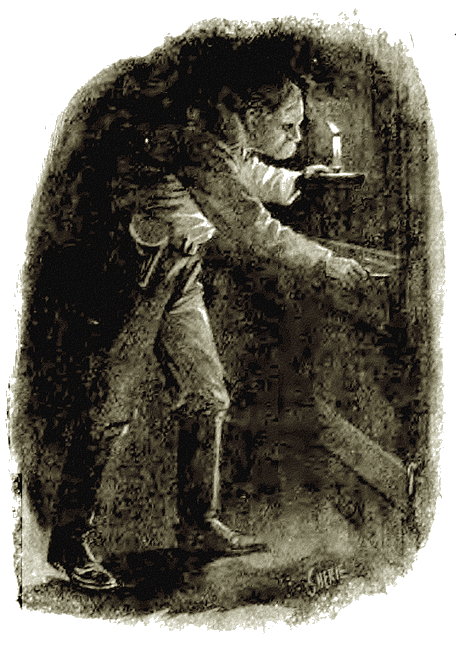

"You yellow swine, you've sold me!"

The road just here ran for some distance through a lot of broken ground and surface workings, so there was no chance of making a detour to avoid the mounted police, whose moving forms Salter could now see dimly in the distance. The terrified Cape boy, feeling the cold revolver-muzzle in the nape of his neck, lashed his horses into a gallop. The shapes on ahead grew more and more distinct, and presently there rang out the short sharp order:

"Halt, or we'll shoot!"

"You yellow swine, you've sold me!"

"Halt, and I'll shoot!" Salter hissed into the driver's ear, and the cart sped on at a gallop. Now mounted forms seemed to rush out of the darkness and close round. Meanwhile the lights of Freetown were getting tantalisingly near. A few minutes more and—crack, crack, crack, went the rifles to right and left and in front. The off leader reared up with a shrill neigh and then pitched on to his head with the others and the cart on top of him.

The off leader reared up with a shrill neigh.

"Waal, gentlemen, may I ask what is the meaning of this outrage on an unoffending traveller?" said Salter, in a cool but angry voice as the police rode up.

"That'll do, Mr. Salter," said Inspector Lipinzki's voice out of the darkness; "the bluff's played out. Pass up with the klips and come along quietly. Don't shoot, for that's murder, and you're covered three times over."

The Yankee climbed down out of the cart with an audible chuckle, walked quietly to Lipinzki's stirrup, and held up his hand, saying:

"Ah, it's you, inspector, is it? Sorry I've brought you a booby hunt like this, and given the Deepartment a horse to pay for. Klips? Waal, I did hear of some going across last night inside a kaffir's dog, but you've struck the wrong she-bang for stones to-night, true's death you have. But you can search and see if you like."

The inspector took no notice either of the Yankee's extended hand or his speech. He just covered Salter with a revolver, and ordered his men to light their lanterns, and search everything thoroughly. They obeyed, and after a twenty minutes' investigation, during which they employed every device that their ingenuity and experience could suggest, on the cart, clothing, and person of Salter (who submitted like a lamb), and even on the horses, they were forced to confess that they had drawn blank.

"Waal, boss, are you satisfied that I ain't sellin' you a pup this time?" said Salter, as he finished re-making his toilet—for he had stripped to the buff with the true hardihood of a man who is playing for a big stake and means to win.

Not so much as a schlenter had been found, and Mr. Inspector Lipinzki felt that he had got himself into a very nasty place. He had stopped a seemingly honest traveller, shot one of his horses, and submitted him to the indignity of a personal search. Visions of his lost bet, of a civil action for damages before a jury that might probably be I.D.B.'s to a man, of heavy damages, and of the storm of ridicule that would overwhelm him at the end, flashed in quick succession past his mental gaze, and, being only human after all, he decided to temporise.

"I'm out, Mr. Salter!" he said, with the best assumption of cordiality that he could muster. "I'm dead out, and it's for you to call the game. I'm not satisfied, but I know when I'm licked, and I am this time. What's it to be?"

"Waal," drawled the Yankee, "seein's how you've pulled me up here, shot a horse, cut up the fit-out, and made me undress in this almighty cold, I think the least you and your fellows can do is to come across to Mike Maguire's shanty yonder and take a drink. You bet I want one pretty bad. What do you say?"

Under the peculiar circumstances there appeared to be only one thing to say, and that was "Yes." In fact, Inspector Lipinzki thought it a remarkably good get out. Besides, a miracle might happen even yet, so he agreed, and followed it up with a really handsome apology.

The result was that within a very few minutes the dead horse was unharnessed and pulled out of the road, the other leader hitched on to the end of the pole, and the whole party trotted across the border towards Mike Maguire's store and shanty. On the way, Salter roasted the Cape boy unmercifully, and then not only consoled him, but mystified him considerably, by telling that he should have his money after all.

In spite of the wrong that had been done him, Salter insisted on standing the first round of drinks when the party at length stood up against Maguire's bar. The drinks were duly raised and lowered, and while Lipinzki was ordering the next round, he said very quietly:

"By the way, boss, about those stones. P'raps, as you've come all this way, you might like to see them. Here they are!" While he was speaking, he had pulled the Cape boy towards him and thrust his hand into his trousers' pocket. He pulled out the identical envelope which he had asked for in the bar of the Queen's Hotel, with the inspector's signature still written across the flap. He handed it over to the bar-keeper and said:

"When the chief of the Deepartment in Kimberley does do it, he does it to rights. Just you open that, Mike, and tell me if you ever saw a prettier lot."

Mr. Maguire looked at the signature, glanced curiously at the astounded inspector, then opened the envelope, unfolded the bulky packet that was in it, and disclosed about fifty rough diamonds, the sight of which made even his experienced eyes water. Orange and blue, green, rose, and pure white, they glittered most tantalisingly in the light of the paraffin lamp which hung above the bar counter.

"Mother av Moses, what a lot! Shure, they're the pick av the mines, and worth a king's ransom any day!" said Mr. Maguire, in a somewhat awe-stricken tone, as he gingerly turned the priceless stones over and over with the end of his thick forefinger. "Here, take them back, mister, before I'm tempted beyond the endurance av human flesh and blood by the sight av the darlin's. God bless their pretty sparkles!"

So saying, honest Mike, knowing that his own reward was to come, handed them back to Salter, who pocketed them in a handful as he turned to the almost paralysed inspector and his men, and said:

"No, boss, they're not schlenters this time—a little steam and a little skill, you know. Waal, here's to you, and now I'll just take your Good-for[*] for that thousand pounds, Mr. Lipinzki, and then we'll say good-night. I'm not coming back to Kimberley till I've done my business down in Port Elizabeth. Chin chin!"

[* The South African form of I.O.U.]

It took all the inspector's self-control to enable him to rise to the occasion, but he did it. He took his licking like a man and a sportsman, and his subordinates and the Cape boy just grinned and drank their liquors, for, after all, I.D.B. is but a gamble, and the gods look sometimes this way and sometimes that. The game had been smartly played, and they looked upon the winner rather with admiration than with enmity.

That round of drinks was drunk, and then another and another, and then—alas for the weakness of the best-balanced human nature, Mr. Seth Salter, with a confidence born of the fullness of his triumph, left the bar-room with the diamonds in his pocket, and went out into the night to see his discomfited friends off on their homeward journey. Exactly what happened during the next quarter of an hour was never known. Distant sounds of shouts and shots reached the waiting ears of Mr. Maguire, but he knew his business, and quietly locked the door, remarking to himself the while:

Mr. Maguire knew his business, and quietly locked the door.

"Smart as he is, it's meself that's fearin' he's put his fut into ut this time. What a hairless juggins he was not to lave the sparklers where they were safe when he had them there. Well, well, life's a gamble anyhow, and so's death, too, sometimes. I hope they haven't hurt him beyant recovery."

Shortly before three o'clock that morning, Inspector Lipinzki and his merry men escorted the three-horse Cape cart into Kimberley. The horse that was lying dead on the veld was paid for to its full value, and the driver got his £200, coupled with a private intimation to the effect that, if he ever opened his mouth on the subject of that night's doings, fifty lashes and five years as an illicit diamond runner would be the least that he could expect. Inspector Lipinzki slept the balance of the night out with a £15,000 parcel of diamonds under his pillow, and the next day there was no one in Kimberley who had anything to say to him on the subject of double-skinned dogs or the selling of pups.

Of course, there were many in camp who would have given a good deal to know what had become of Mr. Seth Salter—but that is a yarn with another twist in it.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.