RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"Knaves of Diamonds," C. Arthur Simpson,

London, 1899

(with author's surname misspelt)

Headpiece from Pearson's Magazine

IT was several months after the brilliant if somewhat mysterious recovery of the £15,000 parcel from the notorious but now vanished Seth Salter that I had the pleasure, and I think I may fairly add the privilege, of making the acquaintance of Inspector Lipinski.

I can say without hesitation that in the course of wanderings which have led me over a considerable portion of the lands and seas of the world, I have never met a more interesting man than he was. I say "was," poor fellow, for he is now no longer anything but a memory of bitterness to the I.D.B. fraternity.

There is no need of further explanation of the all too brief intimacy which followed our introduction than the statement of the fact that the greatest South African detective of his day was after all a man as well as a detective, and hence not only justifiably proud of the many brilliant achievements which illustrated his career, but also by no means loth that some day the story of them should, with all due and proper precautions and reservations, be told to a wider and possibly less prejudiced audience than the motley and migratory population of the camp as it was in his day.

I had not been five minutes in the cosy, tastily-furnished sanctum of his low, broad-roofed bungalow in New De Beers Road before I saw it was a museum as well as a study. Specimens of all sorts of queer apparatus employed by the I.D.B.'s for smuggling diamonds were scattered over the tables and mantelpiece.

There were massive, handsomely-carved briar and meerschaum pipes which seemed to hold wonderfully little tobacco for their size; rough sticks of firewood ingeniously hollowed out, which must have been worth a good round sum in their time; hollow handles of travelling trunks; ladies' boot heels of the fashion affected on a memorable occasion by Mrs. Michael Mosenstein; and novels, hymn-books, church-services, and Bibles, with cavities cut out of the centre of their leaves which had once held thousands of pounds' worth of illicit stones on their unsuspected passage through the book-post.

But none of these interested, or, indeed, puzzled me so much as did a couple of curiously-assorted articles which lay under a little glass case on a wall bracket. One was an ordinary piece of heavy lead tubing, about three inches long and an inch in diameter, sealed by fusing at both ends, and having a little brass tap fused into one end. The other was a small ragged piece of dirty red sheet india-rubber, very thin—in fact almost transparent—and, roughly speaking, four or five inches square.

I was looking at these things, wondering what on earth could be the connection between them, and what manner of strange story might be connected with them, when the inspector came in.

"Good-evening. Glad to see you," he said, in his quiet and almost gentle voice, and without a trace of foreign accent, as we shook hands. "Well, what do you think of my museum? I daresay you've guessed already that if some of these things could speak, they could keep your readers entertained for some little time, eh?"

"Good-evening. Glad to see you," he said.

"Well, there is no reason why their owner shouldn't speak for them," I said, making the obvious reply, "provided always, of course, that it wouldn't be giving away too many secrets of state."

"My dear sir," he said, with a smile which curled up the ends of his little black, carefully-trimmed moustache ever so slightly, "I should not have made you the promise I did at the Club the other night if I had not been prepared to rely absolutely on your discretion—and my own. Now, there's whisky-and-soda or brandy; which do you prefer? You smoke, of course, and I think you'll find these pretty good, and that chair I can recommend. I have unravelled many a knotty problem in it, I can tell you."

"And now," he went on, when we were at last comfortably settled, "may I ask which of my relics has most aroused your professional curiosity?"

It was already on the tip of my tongue to ask for the story of the gas-pipe and piece of india-rubber, but the inspector forestalled me by saying:

"But perhaps that is hardly a fair question, as they will all probably seem pretty strange to you. Now, for instance, I saw you looking at two of my curios when I came in. You would hardly expect them to be associated, and very intimately too, with about the most daring and skilfully planned diamond robbery that ever took place on the Fields, or off them, for the matter of that, would you?"

"Hardly," I said. "And yet I think I have learned enough of the devious ways of the I.D.B. to be prepared for a perfectly logical explanation of the fact."

"As logical as I think I may fairly say romantic," replied the inspector, as he set his glass down. "In one sense it was the most ticklish problem that I've ever had to tackle. Of course, you've heard some version or other of the disappearance of the Great De Beers' Diamond?"

"I should rather think I had!" I said, with a decided thrill of pleasurable anticipation, for I felt sure that now, if ever, I was going to get to the bottom of the great mystery. "Everybody in camp seems to have a different version of it, and, of course, everyone seems to think that if he had only had the management of the case, the mystery would have been solved long ago."

"It is invariably the case," said the inspector, with another of his quiet, pleasant smiles, "that everyone can do work better than those whose reputation depends upon the doing of it. We are not altogether fools at the Department, and yet I have to confess that I myself was in ignorance as to just how that diamond disappeared or where it got to, until twelve hours ago.

"Now, I am going to tell you the facts exactly as they are, but under the condition that you will alter all the names except, if you choose, my own, and that you will not publish the story for at least twelve months to come. There are personal and private reasons for this which you will probably understand without my stating them. Of course it will, in time, leak out into the papers, although there has been, and will be, no prosecution; but anything in the newspapers will of necessity be garbled and incorrect, and—well, I may as well confess that I am sufficiently vain to wish that my share in the transaction shall not be left altogether to the tender mercies of the imaginative penny-a-liner."

I acknowledged the compliment with a bow as graceful as the easiness of the inspector's chair would allow me to make, but I said nothing, as I wanted to get to the story.

"I had better begin at the beginning," the inspector went on, as he meditatively snipped the end of a fresh cigar. "As I suppose you already know, the largest and most valuable diamond ever found on these Fields was a really magnificent stone, a perfect octahedron, pure white, without a flaw, and weighing close on 500 carats. There's a photograph of it there on the mantelpiece. I've got another one by me; I'll give it you before you leave Kimberley.

"Well, this stone was found about six months ago in one of the drives on the 800-foot level of the Kimberley Mine. It was taken by the overseer straight to the De Beers' offices and placed on the Secretary's desk—you know where he sits, on the right hand side as you go into the board room through the green baize doors. There were several of the Directors present at the time, and, as you may imagine, they were pretty well pleased at the find, for the stone, without any exaggeration, was worth a prince's ransom.

"Of course, I needn't tell you that the value per carat of a diamond which is perfect and of a good colour increases in a sort of geometrical progression with the size. I daresay that stone was worth anywhere between one and two millions, according to the depth of the purchaser's purse. It was worthy to adorn the proudest crown in the world instead of—but there, you'll think me a very poor story-teller if I anticipate.

"Well, the diamond, after being duly admired, was taken upstairs to the Diamond Room by the Secretary himself, accompanied by two of the Directors. Of course, you have been through the new offices of De Beers, but still, perhaps I had better just run over the ground, as the locality is rather important.

"You know that when you get upstairs and turn to the right on the landing from the top of the staircase there is a door with a little grille in it. You knock, a trap-door is raised, and, if you are recognised and your business warrants it, you are admitted. Then you go along a little passage, out of which a room opens on the left, and in front of you is another door leading into the Diamond Rooms themselves.

"You know, too, that in the main room fronting Stockdale Street and Jones Street the diamond tables run round the two sides, under the windows, and are railed off from the rest of the room by a single light wooden rail. There is a table in the middle of the room, and on your right hand as you go in there is a big safe standing against the wall. You will remember, too, that in the corner exactly facing the door stands the glass case containing the diamond scales. I want you particularly to recall the fact that these scales stand diagonally across the corner by the window. The secondary room, as you know, opens out on to the left, but that is not of much consequence." I signified my remembrance of these details, and the inspector went on:

"The diamond was first put in the scale and weighed in the presence of the Secretary and the two Directors by one of the higher officials, a licensed diamond broker and a most trusted employee of De Beers, whom you may call Philip Marsden when you come to write the story. The weight, as I told you, in round figures was 500 carats. The stone was then photographed, partly for purposes of identification, and partly as a reminder of the biggest stone ever found in Kimberley in its rough state.

"The gem was then handed over to Mr. Marsden's care pending the departure of the Diamond Post to Vryburg on the following Monday—this was a Tuesday. The Secretary saw it locked up in the big safe by Mr. Marsden, who, as usual, was accompanied by another official, a younger man than himself, whom you can call Henry Lomas, a connection of his, and also one of the most trusted members of the staff.

"Every day, and sometimes two or three times a day, either the Secretary or one or other of the Directors came up and had a look at the big stone, either for their own satisfaction or to show it to some of their more intimate friends. I ought, perhaps, to have told you before that the whole Diamond Room staff were practically sworn to secrecy on the subject, because, as you will readily understand, it was not considered desirable for such an exceedingly valuable find to be made public property in a place like this. When Saturday came it was decided not to send it down to Cape Town, for some reasons connected with the state of the market. When the safe was opened on Monday morning the stone was gone.

When the safe was opened on Monday morning the stone was gone.

"I needn't attempt to describe the absolute panic which followed. It had been seen two or three times in the safe on the Saturday, and the Secretary himself was positive that it was there at closing time, because he saw it just as the safe was being locked for the night. In fact he actually saw it put in, for it had been taken out to show to a friend of his a few minutes before.

"The safe had not been tampered with, nor could it have been unlocked, because when it is closed for the night it cannot be opened again unless either the Secretary or the Managing Director is present, as they have each a master-key without which the key used during the day is of no use.

"Of course I was sent for immediately, and I admit that I was fairly staggered. If the Secretary had not been so positive that the stone was locked up when he saw the safe closed on the Saturday, I should have worked upon the theory—the only possible one, as it seemed—that the stone had been abstracted from the safe during the day, concealed in the room, and somehow or other smuggled out, although even that would have been almost impossible in consequence of the strictness of the searching system, and the almost certain discovery which must have followed an attempt to get it out of the town.

"Both the rooms were searched in every nook and cranny. The whole staff, naturally feeling that every one of them must be suspected, immediately volunteered to submit to any process of search that I might think satisfactory, and I can assure you the search was a very thorough one.

"Nothing was found, and when we had done there wasn't a scintilla of evidence to warrant us in suspecting anybody. It is true that the diamond was last actually seen by the Secretary in charge of Mr. Marsden and Mr. Lomas. Mr. Marsden opened the safe, Mr. Lomas put the tray containing the big stone and several other fine ones into its usual compartment, and the safe door was locked. Therefore that fact went for nothing.

"You know, I suppose, that one of the Diamond Room staff always remains all night in the room; there is at least one night-watchman on every landing; and the frontages are patrolled all night by armed men of the special police. Lomas was on duty on the Saturday night. He was searched as usual when he came off duty on Sunday morning. Nothing was found, and I recognised that it was absolutely impossible that he could have brought the diamond out of the room or passed it to any confederate in the street without being discovered. Therefore, though at first sight suspicion might have pointed to him as being the one who was apparently last in the room with the diamond, there was absolutely no reason to connect that fact with its disappearance."

"I must say that that is a great deal plainer and more matter-of-fact than any of the other stories that I have heard of the mysterious disappearance," I said, as the inspector paused to re-fill his glass and ask me to do likewise.

"Yes," he said drily, "the truth is more commonplace up to a certain point than the sort of stories that a stranger will find floating about Kimberley; but still I daresay you have found in your own profession that it sometimes has a way of—to put it in sporting language—giving Fiction a seven-pound handicap and beating it in a canter."

"For my own part," I answered, with an affirmative nod, "my money would go on Fact every time. Therefore it would go on now if I were betting. At any rate, I may say that none of the fiction that I have so far heard has offered even a reasonable explanation of the disappearance of that diamond, given the conditions which you have just stated, and, as far as I can see, I admit that I couldn't give the remotest guess at the solution of the mystery."

"That's exactly what I said to myself after I had been worrying day and night for more than a week over it," said the inspector. "And then," he went on, suddenly getting up from his seat and beginning to walk up and down the room with quick, irregular strides, "all of a sudden, in the middle of a very much smaller puzzle, just one of the common I.D.B. cases we have almost every week, the whole of the work that I was engaged upon vanished from my mind, leaving it for the moment a perfect blank. Then like a lightning flash out of a black cloud, there came a momentary ray of light which showed me the clue to the mystery. That was the idea. These," he said, stopping in front of the mantelpiece and putting his finger on the glass case which covered the two relics that had started the story, "these were the materialisation of it."

"These," he said, stopping in front of the mantelpiece.

"And yet, my dear inspector," I ventured to interrupt, "you will perhaps pardon me for saying that your ray of light leaves me just as much in the dark as ever."

"But your darkness shall be made day all in good course," he said, with a smile. I could see that he had an eye for dramatic effect, and so I thought it was better to let him tell the story uninterrupted and in his own way, so I simply assured him of my ever-increasing interest and waited for him to go on. He took a couple of turns up and down the room in silence, as though he were considering in what form he should spring the solution of the mystery upon me, then he stopped and said abruptly:

"I didn't tell you that the next morning—that is to say, Sunday—Mr. Marsden went out on horseback, shooting in the veld up towards that range of hills which lies over yonder to the north-westward between here and Barkly West. I can see by your face that you are already asking yourself what that has got to do with spiriting a million or so's worth of crystallised carbon out of the safe at De Beers'. Well, a little patience, and you shall see.

"Early that same Sunday morning, I was walking down Stockdale Street, in front of the De Beers' offices, smoking a cigar, and, of course, worrying my brains about the diamond. I took a long draw at my weed, and quite involuntarily put my head back and blew it up into the air—there, just like that—and the cloud drifted diagonally across the street dead in the direction of the hills on which Mr. Philip Marsden would just then be hunting buck. At the same instant the revelation which had scattered my thoughts about the other little case that I mentioned just now came back to me. I saw with my mind's eye, of course—well, now, what do you think I saw?"

"If it wouldn't spoil an incomparable detective," I said, somewhat irrelevantly, "I should say that you would make an excellent story-teller. Never mind what I think. I'm in the plastic condition just now. I am receiving impressions, not making them. Now, what did you see?"

"I saw the Great De Beers' Diamond—say from ten to fifteen hundred thousand pounds' worth of concentrated capital—floating from the upper storey of the De Beers' Consolidated Mines, rising over the housetops, and drifting down the wind to Mr. Philip Marsden's hunting-ground."

To say that I stared in the silence of blank amazement at the inspector, who made this astounding assertion with a dramatic gesture and inflection which naturally cannot be reproduced in print, would be to utter the merest commonplace. He seemed to take my stare for one of incredulity rather than wonder, for he said almost sharply:

"Ah, I see you are beginning to think that I am talking fiction now; but never mind, we will see about that later on. You have followed me, I have no doubt, closely enough to understand that, having exhausted all the resources of my experience and such native wit as the Fates have given me, and having made the most minute analysis of the circumstances of the case, I had come to the fixed conclusion that the great diamond had not been carried out of the room on the person of a human being, nor had it been dropped or thrown from the windows to the street—yet it was equally undeniable that it had got out of the safe and out of the room."

"And therefore it flew out, I suppose!" I could not help interrupting, nor, I am afraid, could I quite avoid a suggestion of incredulity in my tone.

"Yes, my dear sir!" replied the inspector, with an emphasis which he increased by slapping the four fingers of his right hand on the palm of his left. "Yes, it flew out. It flew some seventeen or eighteen miles before it returned to the earth in which it was born, if we may accept the theory of the terrestrial origin of diamonds. So far, as the event proved, I was absolutely correct, wild and all as you may naturally think my hypothesis to have been.

"But," he continued, stopping in his walk and making an eloquent gesture of apology, "being only human, I almost instantly deviated from truth into error. In fact, I freely confess to you that there and then I made what I consider to be the greatest and most fatal mistake of my career.

"Absolutely certain as I was that the diamond had been conveyed through the air to the Barkly Hills, and that Mr. Philip Marsden's shooting expedition had been undertaken with the object of recovering it, I had all the approaches to the town watched till he came back. He came in by the Old Transvaal Road about an hour after dark. I had him arrested, took him into the house of one of my men who happened to live out that way, searched him, as I might say, from the roots of his hair to the soles of his feet, and found—nothing.

"I had him arrested."

"Of course he was indignant, and of course I looked a very considerable fool. In fact, nothing would pacify him but that I should meet him the next morning in the Board Room at De Beers', and, in the presence of the Secretary and at least three Directors, apologise to him for my unfounded suspicions and the outrage that they had led me to make upon him. I was, of course, as you might say, between the devil and the deep sea. I had to do it, and I did it; but my convictions and my suspicions remained exactly what they were before.

"Then there began a very strange, and, although you may think the term curious, a very pathetic, waiting game between us. He knew that in spite of his temporary victory I had really solved the mystery and was on the right track. I knew that the great diamond was out yonder somewhere among the hills or on the veld, and I knew, too, that he was only waiting for my vigilance to relax to go out and get it.

"Day after day, week after week, and month after month the game went on in silence. We met almost every day. His credit had been completely restored at De Beers'. Lomas, his connection and, as I firmly believed, his confederate, had been, through his influence, sent on a mission to England, and when he went I confess to you that I thought the game was up—that Marsden had somehow managed to recover the diamond, and that Lomas had taken it beyond our reach.

"Still I watched and waited, and as time went on I saw that my fears were groundless, and that the gem was still on the veld or in the hills. He kept up bravely for weeks, but at last the strain began to tell upon him. Picture to yourself the pitiable position of a man of good family in the Old Country, of expensive tastes and very considerable ambition, living here in Kimberley on a salary of some £12 a week, worth about £5 in England, and knowing that within a few miles of him, in a spot that he alone knew of, there lay a concrete fortune of, say, fifteen hundred thousand pounds, which was his for the picking up, if he only dared to go and take it, and yet he dared not do so.

"Yes, it is a pitiless trade this of ours, and professional thief-catchers can't afford to have much to do with mercy, and yet I tell you that as I watched that man day after day, with the fever growing hotter in his blood and the unbearable anxiety tearing ever harder and harder at his nerves, I pitied him—yes, I pitied him so much that I even found myself growing impatient for the end to come. Fancy that, a detective, a thief-catcher getting impatient to see his victim out of his misery.

"Well, I had to wait six months—that is to say, I had to wait until five o'clock this morning—for the end. Soon after four one of my men came and knocked me up; he brought a note into my bedroom and I read it in bed. It was from Philip Marsden asking me to go and see him at once and alone. I went, as you may be sure, with as little delay as possible. I found him in his sitting-room. The lights were burning. He was fully dressed, and had evidently been up all night.

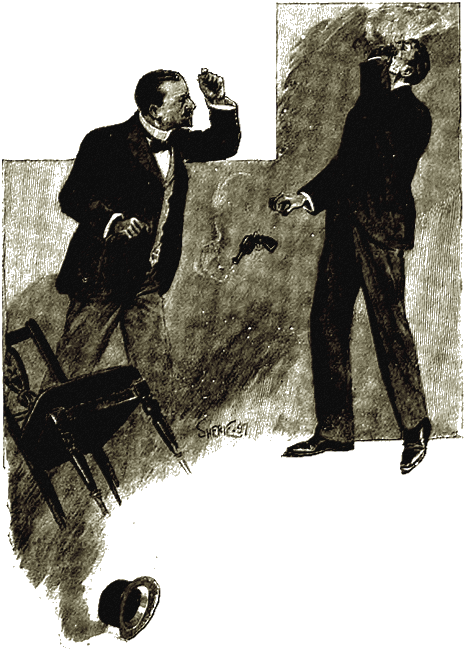

"I saw him standing in front of me, covering me with a brace of revolvers."

"I saw him standing in front of me, covering me with a brace of revolvers."

"Even I, who have seen the despair that comes of crime in most of its worst forms, was shocked at the look of him. Still he greeted me politely and with perfect composure. He affected not to see the hand that I held out to him, but asked me quite kindly to sit down and have a chat with him. I sat down, and when I looked up I saw him standing in front of me, covering me with a brace of revolvers. My life, of course, was absolutely at his mercy, and whatever I might have thought of myself or the situation, there was obviously nothing to do but to sit still and wait for developments.

"He began very quietly to tell me why he had sent for me. He said: 'I wanted to see you, Mr. Lipinski, to clear up this matter about the big diamond. I have seen for a long time—in fact from that Sunday night—that you had worked out a pretty correct notion as to the way that diamond vanished. You are quite right; it did fly across the veld to the Barkly Hills. I am a bit of a chemist, you know, and when I had once made up my mind to steal it—for there is no use in mincing words now—I saw that it would be perfectly absurd to attempt to smuggle such a stone out by any of the ordinary methods.

"'I daresay you wonder what these revolvers are for. They are to keep you there in that chair till I've done, for one thing. If you attempt to get out of it or utter a sound I shall shoot you. If you hear me out you will not be injured, so you may as well sit still and keep your ears open.

"'To have any chance of success I must have had a confederate, and I made young Lomas one. If you look on that little table beside your chair you will see a bit of closed lead piping with a tap in it and a piece of thin sheet india-rubber. That is the remains of the apparatus that I used. I make them a present to you; you may like to add them to your collection.

"'Lomas, when he went on duty that Saturday night, took the bit of tube charged with compressed hydrogen and an empty toy balloon with him. You will remember that that night was very dark, and that the wind had been blowing very steadily all day towards the Barkly Hills. Well, when everything was quiet he filled the balloon with gas, tied the diamond—'

"'But how did he get the diamond out of the safe? The Secretary saw it locked up that evening!' I exclaimed, my curiosity getting the better of my prudence.

"'It was not locked up in the safe at all that night,' he answered, smiling with a sort of ghastly satisfaction. 'Lomas and I, as you know, took the tray of diamonds to the safe, and, as far as the Secretary could see, put them in, but as he put the tray into its compartment he palmed the big diamond as I had taught him to do in a good many lessons before. At the moment that I shut the safe and locked it, the diamond was in his pocket.

"'The Secretary and his friends left the room, Lomas and I went back to the tables, and I told him to clean the scales as I wanted to test them. While he was doing so he slipped the diamond behind the box, and there it lay between the box and the corner of the wall until it was wanted.

"'We all left the room as usual, and, as you know, we were searched. When Lomas went on night-duty there was the diamond ready for its balloon voyage. He filled the balloon just so that it lifted the diamond and no more. The lead pipe he just put where the diamond had been—the only place you never looked in. When the row was over on the Monday I locked it up in the safe. We were all searched that day; the next I brought it away and now you may have it.

"'Two of the windows were open on account of the heat. He watched his opportunity, and sent it adrift about two hours before dawn. You know what a sudden fall there is in the temperature here an hour or so before daybreak. I calculated upon that to contract the volume of the gas sufficiently to destroy the balance and bring the balloon to the ground, and I knew that, if Lomas had obeyed my instructions, it would fall either on the veld or on this side of the hills.

"'The balloon was a bright red, and, to make a long story short, I started out before daybreak that morning, as you know, to look for buck. When I got outside the camp I took compass bearings and rode straight down the wind towards the hills. By good luck or good calculation, or both, I must have followed the course of the balloon almost exactly, for in three hours after I left the camp I saw the little red speck ahead of me up among the stones on the hillside.

"'I dodged about for a bit as though I were really after buck, in case anybody was watching me. I worked round to the red spot, put my foot on the balloon, and burst it. I folded the india-rubber up, as I didn't like to leave it there, and put it in my pocket-book. You remember that when you searched me you didn't open my pocketbook, as, of course, it was perfectly flat, and the diamond couldn't possibly have been in it. That's how you missed your clue, though I don't suppose it would have been much use to you as you'd already guessed it. However, there it is at your service now.'

"'And the diamond?'

"As I said these three words his whole manner suddenly changed. So far he had spoken quietly and deliberately, and without even a trace of anger in his voice, but now his white, sunken cheeks suddenly flushed a bright fever red, and his eyes literally blazed at me. His voice sank to a low, hissing tone that was really horrible to hear.

"'The diamond!' he said. 'Yes, curse it, and curse you, Mr. Inspector Lipinski—for it and you have been a curse to me! Day and night I have seen the spot where I buried it, and day and night you have kept your nets spread about my feet so that I could not move a step to go and take it. I can bear the suspense no longer. Between you—you and that infernal stone—you have wrecked my health and driven me mad. If I had all the wealth of De Beers' now it wouldn't be any use to me; and to-night a new fear came to me—that if this goes on much longer I shall go mad, really mad, and in my delirium rob myself of my revenge on you by letting out where I hid it.

"'Now, listen, Lomas has gone. He is beyond your reach. He has changed his name—his very identity. I have sent him, by different posts and to different names and addresses, two letters. One is a plan and the other is a key to it. With those two pieces of paper he can find the diamond. Without them you can hunt for a century and never go near it.

"'And now that you know that—that your incomparable stone, which should have been mine, is out yonder somewhere where you can never find it, you and the De Beers' people will be able to guess at the tortures of Tantalus that you have made me endure. That is all you have got by your smartness. That is my legacy to you—curse you! If I had my way I would send you all out there to hunt for it without food or drink till you died of hunger and thirst of body, as you have made me die a living death of hunger and thirst of mind.'

"As he said this, he covered me with one revolver, and put the muzzle of the other into his mouth. With an ungovernable impulse I sprang to my feet. He pulled both triggers at once. One bullet passed between my arm and my body, ripping a piece out of my coat sleeve; the other—well, I can spare you the details. He dropped dead instantly."

"The other—well, I can spare you the details."

"And the diamond?" I said.

"The reward is £20,000, and it is at your service," replied the inspector, in his suavest manner, "provided that you can find the stone—or Mr. Lomas and his plans."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.