RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

A story of the American conquest of Europe, showing how three

persons came to enthrone themselves as Lords of the Air and Sea,

and the consequences thereof to the existing order of things.

Gold! Gold! Gold! Bright and yellow, hard and cold,

Molten, graven, hammer'd and roll'd;

Heavy to get, and light to hold;

Hoarded, barter'd, bought and sold,

Stolen, borrow'd, squandered, doled:

Spurn'd by the young, but hugg'd by the old

To the very verge of the churchyard mould;

Price of many a crime untold; Gold! Gold! Gold!

—Hood.

OF all the material forces in existence the power of Gold is the greatest. It has, indeed, in too many instances, proved more potent than the strongest of human passions and moral sentiments. The maiden, loving one man, has been sold to another—for gold. Statesmen and Kings have sold their country's trust—for gold. Men and women have changed their faith and even turned their backs on their God—for gold. There is no crime that has not been committed, no dishonour that has not been incurred—for gold.

In the following chapters an attempt has been made to forecast the possibilities—Moral, social and political—of the control of a practically unlimited supply of gold in the hands of two or three people who are prepared to use it well or ill as circumstances, which they themselves to a great extent create, may demand.

The first use they make of their illimitable wealth is to enthrone themselves as Lords of Air and Sea, in other words Dictators of Human Affairs. The outcome of such a situation is not far to seek. As that Power was used for good or ill the world would become a more or less imperfect imitation of Heaven or Hell.

The vast accumulation of wealth in a few hands—not always of the cleanest—is undoubtedly the most ominous feature of Modern Commercial life. Whether the exercise of such a terrific Power by rich despots as too many of these men have proved themselves to be—would in the end work out as a blessing or a curse to Humanity is a problem which, in accomplishing their destinies, the characters of this story may possibly help in some measure to solve. —G.G.

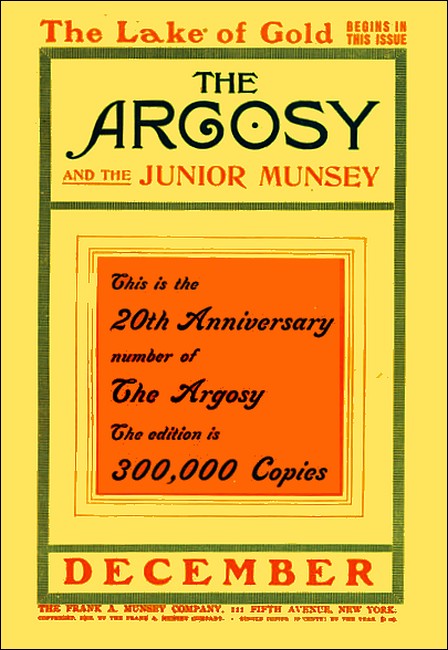

The Argosy, Dec 1902, with Part I of "The Lake of Gold"

"WELL, I guess that's fixed it as far as figuring can fix anything. If dad was right and I'm right—and I'll take my iron-clad oath I am—the Great Problem is solved at last.

"It's curious how near dad got to it, and yet managed after all to stop so far away. It was just the placing of those disks, his gravity destroyers as he called them, only he didn't make them destroy gravity. I shan't either, but I'll do a lot to counteract it.

"Good night, my beauties. We've had a good many pleasant evenings together, and now it's all over, except finding the money to change you from drawings on cardboard into real things of steel and glass and aluminum—cruisers of the air and sea!

"Ah! If I only had a million or a half! Yes, getting that is the dream now—not the air-ships or the submarines. It's just dollars now—dollars or nothing!"

During his little soliloquy Paul Kingston had collected the carefully drawn plans and elevations, sections, and scales with which his big table was littered, put the sheets of cardboard and paper together with loving care, and stowed them away in a big drawer.

Then he picked up a corncob pipe, filled and lit it, and went out on the veranda which ran along the end of the house fronting the southeast.

Lake City, Colorado, was still a town with a certain amount of business and prosperity, but nothing to what it had enjoyed in the great days of the Silver Boom.

In fact, its fall from greatness was still amply manifested in the ragged fringe of unoccupied houses and deserted stores which had once formed its flourishing suburbs. The present Lake City, a town between six and seven thousand inhabitants, which had once had fifty, stood on the southeastern slope of a range of hills which was an offshoot of the once famous Sierra de la Plata, or Silver Range.

Paul's veranda looked out over the lake, which now lay shining silver-blue under the moonlight, fringed with a broad, somber border of giant pines.

Another range of hills rose, pine crowned, beyond it, and beyond this again, nearly a hundred miles away, but looking only half the distance in that wonderful atmosphere, the snowy pinnacles of the Sierra Blanca twinkled like diamonds against the blackness of the midnight sky.

"Fancy being able to fly over there," he went on, continuing his waking dream aloud, "to think no more of a mountain range than a bird does of a house roof! Fancy being able to rise from the earth just when you like, start your engines, and away to where you want to go in a bee line! No need to creep round curves and under snow sheds, worrying all the time about landslides and washouts. Then away over the sea, not caring a cent whether it is rough or smooth, and looking down and watching the big steamers crawling along, fighting the stream for every mile they make, while the lord of the air rides on the wings of the wind. Yes, it will be glorious—glorious, if I can only get those dollars!"

"Paul, don't you think it is time you were getting to bed? Have you any idea what o'clock it is?"

"Ah, mother, is that you? Say, mother, how would you like to be mistress of the world?"

"Mistress of the world, Paul! What on earth are you talking about? You've not been thinking too much again, have you? You know what I've told you about the trouble I had with your father to keep him from doing that!

"I've been listening to you here for the last minute or so, dreaming about flying over land and sea. My dear Paul, I hope for my sake, and your own, that you're not going to waste your time and your talent as he did, dreaming about that impossible air-ship, which he was always going to make perfect and never did."

"Don't you worry about that, mother," exclaimed the lad—for as a matter of fact Paul Kingston was but little more. "It wasn't dreaming, it was all hard thinking dad did; only for some reason or other he didn't think quite far enough. And there's no such thing as wasting time in hard thinking.

"Every hour he put into this is going to be worth a few million dollars to us, if I can only get the money to start with. If I get that, what you call his dreaming over the air-ship will be the biggest legacy a man ever left to his son; it will be nothing less than the mastery of the world, and that is what I meant when I asked you if you would like to be mistress of it."

"But surely, my dear Paul, are you quite serious? You know that no one would be more delighted at your success than your mother, but to be able to fly in a ship through the air! Are you really quite sure you haven't been dreaming one of your father's day dreams again?"

"Serious, mother?" he replied, putting his arm round her shoulders. "Never a man, or a boy if you like, had better reason to be serious than I have just now! I've done it, at any rate as far as theory and calculation go.

"I've worked everything out to thousandths of inches and ounces and hundredths of horse power. I've got his anti gravity disks into the right position, I've perfected his conversion principle for turning petroleum and coal dust into actual working energy right away without boilers or furnaces, and so I've been able to get motors that will exert a horse power for about every half pound of their weight.

"Of course, with that the problem of direct flight is solved. The other puzzle, which no one has ever been able to find an answer to before, how to balance yourself perfectly in the air as a bird does, is solved by the gravitational disks.

"Now just come in and have a look at my plans," he went on, drawing her towards the door. "I'm not going to bother you with figures or mechanics or mathematics or anything of that sort; they will he for the millionaire and his experts when they come along. I just want to give you a general idea as to what the thing will be like if I can only get it materialized."

They went to the drawing table and he took out his beloved plans again and showed her everything, from the smallest details of machinery to the beautifully drawn and tinted representation of the complete air-ship—as she might be some day.

His mother, full for the moment of sadly tender memories of the hours she had spent with his father looking at similar drawings and listening to just such confident talk of instant success, followed his rapid description as well as she could, with more fear than hope in her heart; for if it had not been for dreams such as this, her husband, so all his friends had told her, might have lived a millionaire instead of breaking his neck at the bottom of a mine shaft doing his work as an ordinary, though a very successful, engineer.

"And now," said Paul, when he had finished his glowing description, "you've asked me what would one of those ships cost. Well, say two hundred thousand dollars, about the twenty fifth of the price of an ordinary battleship like the Iowa, and yet she could fight twenty Iowas.

"It isn't only money, mother, it's mastery. A syndicate that owned ten of these ships could run the earth; in fact, the earth just wouldn't have anything to say about it.

"England pays thirty million pounds a year to keep her navy going. We spend about eighteen, and yet ten of these ships could tackle the English and American navies and knock them into scrap iron just as fast as the ships came in sight. It's just a question of money to begin with, and that is all there is to it."

"Ah, but, my boy, two hundred thousand dollars! Why, we haven't twenty thousand outside our income, and, of course, no one would advance you anything on just a lot of sheets of paper with drawings on them."

"No, I guess not, unless I happened to strike the right man, and there's maybe ten men like that wandering around between Maine and Mexico. Only a million dollars! Why, a hundred men in the States could put that down without missing it, and—there's the empire of earth and sea!

"Oh, I forgot, I haven't shown you these yet. See, this is the same principle applied in the reverse way—submarine navigation—and I believe I've found a variant of the Hertz rays that will give me a light that I can see by under water as well as you can see by electric light through the air, and that would solve the problem of submarine navigation at once. It is only a question of dollars between us and an empire that might be as big as the solar system."

"Yes, I see, dollars!" said the mother, putting her arm over the son's shoulder. "Your father always said that it was just dollars, or rather the want of them, that kept him from being rich and famous. I hope it won't be the same with you, Paul."

"It won't," he replied, full of the daring dreams of trustful twenty. "It won't. I've done the work, and the dollars will come somehow; they must."

"They will, I hope," said the mother. "And now, don't you think that you had better go to bed? Do you know that it is nearly two o'clock?"

"Fourteen, you mean," he replied, getting up. "You haven't forgotten that the twenty four hour system was made legal in Lake City last week?"

"Well, it doesn't matter whether it is two or fourteen, it is very late and quite time you went to bed and gave that poor brain of yours a rest after all that thinking. We must talk about the dollars another day."

"All right, mother," he said, beginning to pack up his papers, "and I'll dream about myself as emperor of the air, and lord paramount of the sea. I've done a better night's work than any other man in the States, and I reckon I've earned a good sleep. Good night, I hope you have not been waiting up on my account."

"No, not altogether," she replied, with a somewhat sad little smile. "Now be off to bed, and I hope your dreams will be happy and come true."

Mrs. Paul Kingston had dreams of her own that night, but they were mostly waking ones.

Her son's enthusiastic belief that he had solved the problem on which his father had spent so many years had set her thinking about a letter which she had received that morning. It was from one of her husband's friends and former associates in engineering and mining enterprises.

Paul Kingston, now dead nearly two years, had been a man of great genius, not only in civil engineering and mining work, his own profession, but even still greater in mechanical engineering.

He had, in fact, left England quite early in his career mainly because he was too far ahead in his ideas for English enterprise. He soon got on far enough in the States to marry Shiela Cornell, a bright and pretty American girl whom he had met on the ship, and, under her father's advice, had migrated West.

In Colorado he had met Gillette H. Marvin, a man a few years older than himself, and they had become great friends.

Marvin was a typical Westerner, and he possessed that genius for accumulating dollars which Kingston almost totally lacked. In fact, where money making was concerned, Marvin was as hard as a nail, as unscrupulous as a brigand, at least so those he had worsted at the financial game were wont to declare.

But in private life no one had a bad word to say against him. Tall, blue eyed, golden bearded, straight as a pine, and strong as a horse, he was the incarnation of gentleness, good humor, and generosity.

In fact, those who knew him intimately would tell you that if he did rob ruthlessly with the right hand of business, he gave a great deal of the plunder away again with the left hand of charity.

He was also, always apart from business, a visionary with a strong vein of poetry, and his favorite theory of the future was a millennium brought about by an intellectual despotism of money.

At this time he was good for some seven or eight millions, and had interests in half the industries of the United States.

This man had written the letter which Mrs. Kingston read over again for about the fifth time when she reached her room:

My dear Mrs. Kingston:

I am afraid this letter will cause you considerable surprise, but not, I trust, either pain or anger. It is now nearly two years since poor Paul died, and I am going to tell you a secret which I hope you have never guessed before. Anyhow, I have taken all the pains I know to prevent your doing so.

I loved you from the first time I saw you. I did it just because I couldn't help it; but I know Paul never guessed it, and I don't think you did, so there is no harm done, but you know now why I didn't marry the English lord's daughter.

Of course I know nothing of your feelings towards me, if you have any, which maybe you have not. You see I am playing this hand blind, but if there is any chance for me; I mean, if you will give me permission to try and win the greatest prize the whole earth could give me, just send a couple of lines to say that I may take a run down to Lake City.

Yours faithfully,

Gillette H. Marvin.

Shiela Kingston had thought a great deal about this letter during the day, and now she put in some more thinking, because the brief conversation with her son had given her new ideas.

She had married at seventeen, and was now nearly thirty seven, but she came of a good old American stock that wore well, and she didn't look more than thirty two.

Her figure was as straight and as shapely as it had been at twenty five, and her fair, soft skinned face, with its small regular features and laughing brown eyes, looked very sweet and fresh in its framework of abundant chestnut hair.

She had known Marvin for over five years, and they had been excellent friends; but for all that the letter came to her as an absolute shock.

She had always liked and admired him, but this was a thing that she had never dreamed of, so well had he kept his secret. That certainly was a point in his favor, and a great one. She liked the letter he had written, too. It showed a delicate consideration, which she could not help but appreciate.

If she did marry again—and there was no reason why she shouldn't—why not her husband's old friend and hers, a man she had known and liked for years, rather than a stranger—a man, too, who had been a good friend to her son, and had mainly made it possible for him to step into his father's place with such striking success as he had done?

And then his millions! Ah, that was the other thought.

Not a mercenary one exactly, for if she decided to permit him to make the attempt, it would not matter whether he had ten millions or ten thousands—still, if she did, would he not be just the man to be fascinated with Paul's splendid schemes?

And then what if Paul's genius and Marvin's millions did realize the miracle!

Her son, her only child, would verily be one of the greatest among men, raised by his own genius above all the thrones of the world. It was truly a magnificent prospect for a mother's fancy!

She had another good think over it in the morning, and another talk with Paul, who seemed even fuller of hope and confidence than he had been the night before.

Nothing but the money to construct the models was needed to convince any engineer or practical person that both air-ships and submarines would do everything that he claimed for them—only the experiments would cost about five thousand dollars, and it was quite out of the question to take such a large sum as that out of the little fortune his father had managed to save. Yet without such a sacrifice all Paul's labor must go for naught.

When the talk was over, and Paul had gone back to his work, Mrs. Kingston sat down with a bright, almost girlish flush on her cheeks, and wrote:

Dear Mr. Marvin:

Your letter has astonished me very much. I can make no promises, but if you really wish to pay a visit to Lake City, both Paul and myself will be glad to see you. Paul, by the way, has some wonderful ideas about flying ships and submarines which I am sure he would very much like to talk over with you. Sincerely yours,

Shiela Kingston.

GILLETTE MARVIN arrived six days later from San Francisco. It was the quickest time he could make without having a special, and he knew that that would find anything but favor in Mrs. Kingston's eyes.

He came just in the ordinary way, as he had done many times before, and so perfectly guarded was his manner that Paul never had the remotest notion of the real object of his visit until the secret came out several weeks later.

All he noticed was that his mother flushed a little as they shook hands, and turned away rather quickly; but this of course could not convey to his mind the slightest hint of the real state of affairs.

Marvin's first impression on Shiela was a distinctly favorable one.

Of course she could not help looking at him with other eyes now. It was quite impossible that she should not, since she had gone so far on the way to meet him as to give him permission to woo her if he wished, and win her if he could, and she knew, of course, that he was here beside her for that very purpose.

She was well aware, too, that Marvin had the reputation of having carried through successfully every enterprise that he had set his hand to, and she was bound to confess to herself that he looked it.

"I'm going to bring some other visitors down to Lake City in a few days," he said, in half response to Mrs. Kingston's request for news from San Francisco, "and I reckon that will be the most interesting of all the news to you.

"What do you say to having a real gilt edged English duke and his lovely and only daughter stopping right here in Lake City? Not a brewer or a dry goods man, or a stock rigger that has bought a title with big subscriptions to his party; but a regular high toned aristocrat, with blood as blue as a Spanish grandee, and with no more of the nobility nonsense about him than I have."

"Ah, that is a piece of news!" exclaimed Shiela. "A real duke—the highest title next to royalty, isn't it? But what in the land is so much nobility coming here for?"

"You've guessed it the first time," laughed Marvin. "It's just the land his grace is after; certain chunks of God's own country, those with metals and ores for choice.

"You see, although his title and his family are about as old as the English throne, and he has money to burn, he's also one of the new sort of nobility they are getting in England; men who like enterprise for its own sake, who go in for running just as much of the earth as they can get hold of for the mere sport of the game, as we do over here. That's how I came to strike him in London."

"And now what's his name—and what is his daughter like?"

"His name and style, as they say over there, is Godfrey Lorraine Lovell, Duke of Romney, and Marquis, Earl, Baron, and all the rest of it of half a dozen other places. He's about my age, or perhaps a year or two older.

"He lost his eldest son, the Marquis of Chesney, about six months ago in the South African war—shot leading a charge like many other good old English noblemen. Of course it was a terrible sorrow to him, and that is one reason why he is over here.

"His wife died of influenza and pneumonia only about a year before that, so he is left with a young lad at Eton and the Lady Margaret."

"Poor man!" said Mrs. Kingston. "Well, I suppose even dukes have their sorrows like the rest of us. And now we come to the daughter."

"The daughter—say, Paul, if your heart isn't in some one else's safe keeping already, you'll need to get a good grip of it and hold it hard when Lady Margaret is on hand. She's just a daisy, as sweet and pretty and good a girl as the Lord ever put blue blood into.

"She's rising seventeen, tall, dark, and with a pair of eyes! Well, I guess you will not be long finding out what they're like."

"It's to be hoped you won't, Paul. I'm afraid you will find the distance between a duke's daughter and a poor mining engineer in Colorado a little bit too great for your peace of mind, unless, of course, you get your wonderful inventions to work, and then, perhaps—"

"What's that?" exclaimed Marvin. "Have you turned inventor like your father, Paul? I hope you will do more of it. I always told you that that flying ship business of his was a regular wildcat scheme. Yours isn't anything of that sort, I suppose."

"That's just what it is, Mr. Marvin," laughed Paul; "only I've added submarining to it. I've found out where father went wrong, but of course I have had all the good of his work in the experiments. I dare say you think I am talking through my hair, but I'm dead sure I can fly when I get my ship made."

"My dear Paul," said Marvin seriously, "I never knew of an inventor yet that couldn't fly or do any other thing on paper."

Then, remembering his errand, he laughed and went on: "Still, I'm not a man to discourage genius. I know something about engineering and mechanics, and so you must let me have a look at those plans of yours. Have you made your model yet?"

Paul smiled and said somewhat sadly: "A proper working model of the air-ship would cost five thousand dollars."

"Well, five thousand dollars is considerable money to burn over an experiment," said Marvin; "still, we'll have a look at it later on."

There was a slight change of tone in the last few words which caused Paul's mother to look out of the window.

What if Marvin had guessed her thought—or perhaps was it a thought of his own? She hoped so, for the other would be really too terrible.

What would he think of her? He would just think that she was to be bought for her son's sake, and she would rather that Paul should remain in obscurity all his days than have him think that.

That evening after supper Marvin went with Paul into his workroom, and they spent a couple of hours going over the plans and calculations.

Gillette Marvin was a man of many parts, and among those he had played not a few had been connected with mechanics. Like so many of the successful men in the States, he had started as a workman at the bench, whence he had risen to the post of foreman of a big machine shop.

He had done this, as the American workman generally does, by a thorough study of the theory underlying his trade. He had done the same thing when he had made some money by a patent and went in for mining engineering.

He had studied the subject both literally and metaphorically to the bottom, so that he might know exactly what he was putting his money into, and the natural result had been a rapid transition from the workman's bench to the board table of half a dozen big mining and engineering corporations.

He went through the plans and figures and listened to Paul's explanations and enlargements, and the longer he bent over the papers, and the more closely he examined the plans and figures, the keener grew the glint of anticipation in his eyes and the harder the lines of his face.

The other side of his nature was coming out—the business side.

The best friend Paul Kingston had ever had, save his father and mother, the man who had loved his mother in silence for six years and had now come to win her if he could for his wife, disappeared, and in his place came Gillette Marvin, millionaire and money maker at all costs and hazards.

If Paul was only right—and he certainly could find no flaw in his calculations—he saw not only money in this, but the means of controlling the whole commerce and communication of the globe, which, of course, meant practically being money lord of the whole world.

"Well, young man," he said in a totally changed voice that made Paul lookup suddenly from a sheet of paper on which he was jotting down some numbers, "I reckon there's something in it as far as figures can show. You've done all you can so far, but I needn't tell you that figures can lie like politicians. Everyone knows that, and so, you see, no matter how carefully they have been fixed up, they are not much to gamble on, especially when it comes to thousands and hundreds of thousands of dollars.

"Now suppose—mind, I just say suppose—I felt inclined to go into this business, what sort of a deal would you be ready to make?"

"Deal?" exclaimed Paul. "Well, I guess if the thing is a success, if I find the ideas and the work, and you find the money, half shares would be about a square deal, wouldn't it?"

"No, sir!" said Marvin, slewing his chair round and looking at the other with hard, unmoving eyes, "not by half. I don't do business that way, and this is business.

"I'm not talking to my friend's son now. I am talking to a young man who thinks he has got a good idea—and maybe he has—and wants money to work it out. You are making sure of success. I've got to look out for failure. To put it quite straight, what are you prepared to gamble on failure?"

"I'm afraid I've nothing but these and the work I should put in making the ships," said Paul, laying his hand on the papers; "you see, suppose I came to grief down a shaft like poor dad did, there wouldn't be much left for mother except the twenty thousand dollars or so that he left behind, and I couldn't touch that. Yet I'm so certain of this that—well, I'd stake my life on it."

"Good enough!" said Marvin quietly. "If you are solid on that, I'll take you. This is no child's play, and I want to have you in dead earnest about it.

"Now, look here, they call me a pretty hard man to do a trade with. So I am; but what I say I do, and if the other man gets left at the bottom end of the deal, well, that's his funeral. I am ready to gamble money on this business, and plenty of it; but I never lost on a deal yet, and I'm not going to start now."

"I think I understand you," said Paul quite steadily, although, perhaps, he turned a shade paler. "It's my life against your money, gambled on the success or failure of these air-ships and submarines. Well, I'm on it. What do you propose?"

"That sounds good for a start," said Marvin, with no more emotion than if he had been discussing a stock speculation. "That's a square proposition on your side. Mine is this:

"On the day that I give you a certified check for five hundred thousand dollars, which you will use as working capital, you will give me a bond guaranteeing me joint ownership and control of the fleets of air-ships and submarines, half the profits of all operations we may find it necessary to make, dating from the time we begin work, and lastly the bond shall contain a promise from you to me as between gentlemen and men of honor that, if at the end of two years from now the first air-ship and the first submarine are not fully equipped and have not made their trial trips successfully, you will take your own life in any way you may choose, provided I ask you to do so.

"That is necessary from my point of view, for I shall insure your life for three years against accident for a sum sufficient to cover my advance and interest in it. Now, how does that strike you?"

"It's perfectly straight," replied Paul quietly, and with the shadow of a smile on his lips. "I've said I'm ready to gamble my life on the success of this thing, and I'll do it; but, anyhow, I've got the best of the proposition. I'd sell my life tomorrow for half a million, as long as she knew nothing about it. I'd be sure then that she would have a good time."

"Don't talk such all fired rubbish as that, boy!" said Marvin almost roughly. "Do you suppose she would take that for your life? You just get down to work on your scheme, and I guess you'll make a bigger provision for her than that, if she should happen to want it. Now, what are you going to do first? Make a model?"

"Not now," said Paul. "If I had five thousand dollars, I'd have spent it on a model. Now I have got half a million I shall build the air-ship right away. You see that saves time and gives me another chance.

"It would take six months or so to build a model, nearly as long as a ship. Then I dare say you know that when you build a ship or a machine to scale from a working model it sometimes happens that the full sizer doesn't do what the model promised it should do. It's due to something in mathematics that we don't understand, and many an inventor and even practical engineer has got badly left over it.

"These plans and calculations of mine are for the full sized ship. If I find an error in the first, I can either alter it or build another. That's my best hold, I believe, and I'm going to act on it."

He spoke with all the confidence and assurance of American youth; but also with the absolute faith of the inventor who believes in his creation.

Marvin, being an American, liked and respected him for it. His manner changed at once.

He stretched out his hand, smiling for the first time since he had come into the room, and said:

"Well, Paul, that's straight talk anyhow, and I guess if anybody can put this business through you can. Now we're partners. But you will remember that the bond between us is hard business, and concerns no one else but ourselves. Naturally, Mrs. Kingston will know nothing about it."

"Well, hardly," said Paul, "or about the half million either. I shall just tell her that you've taken hold of the idea and advanced me money enough to make a start on it; then when I've got the ship built, I'll take her a trial trip on it."

"No," said Marvin after a little pause, "I wouldn't do that. I mean, tell her that I've advanced you the money. There's no blazing hurry, and I'd rather you said I was interested enough in it to try to form a little syndicate to run you. Yes, I really would prefer you put it that way."

"As you please," said Paul, "any way you like; all I want is the money and a quick start."

"Which you will have, Paul," replied the other, hoping that his little scheme would not be suspected by Mrs. Kingston, and thereby proving that that lady's fears were quite groundless.

The next morning, while Paul was telling his delighted mother about Mr. Marvin and the syndicate he was going to form, that gentleman went down to the telegraph office and wired the manager of the Bank of California to have half a million dollars on deposit payable to the order of Mr. Paul Kingston of Lake City, Colorado, and to send him a certificate to that effect and a check book.

He also sent a lengthy telegram to his grace of Romney, telling him that he could have no better center from which to make his proposed excursions than Lake City, where he would be himself located for some time, and where he had a friend who knew every rood of the country for fifty miles round and would probably be delighted to join the exploring party.

If his grace would reply as to the date of his arrival, he would have everything arranged for him.

Then he went back to his hotel and wrote letters and looked at the papers until the replies were brought to him.

From the bank came a letter to say that his instructions should be immediately attended to, and from the duke a word of thanks and an intimation that he and Lady Margaret would arrive on the third day.

Marvin went to the clerk and said:

"See here, Mr. Sellerd, you are going to have a duke and his daughter, British, mind, stopping here for a few weeks from Thursday, and I want you to understand that the best of everything isn't too good for them. If your best veranda suite—I mean the one at the south corner—is occupied, you'll have to fix it up with the people somehow to change or leave. I'll pay."

"That's all right, Mr. Marvin," replied the clerk. "They are occupied just now. Senator Schuyler and his wife and daughter have had them ten days, but they will be away by the first train to Denver in the morning, so I reckon we will be able to get them fixed up all right, and, duke or not, you know we will do our best for any friend of yours. Anyhow, it's not his fault being a duke, I guess."

"You won't say so when you see him," was the somewhat curt reply as Marvin turned from the counter and walked out of the office.

When he got back to "Lake View," Mrs. Kingston's home, he met her on the veranda and told her half of what he had done, which, of course, was the half containing the coming of the duke and his daughter.

"Why, that will be just lovely!" she exclaimed, flushing and clapping her hands like a girl of twenty. "It's no very high toned place for them to come to, but the Rockies don't beat it for scenery, and if they're out here looking for mining property, ranches, and that sort of thing, why, what's the matter with making ourselves into an exploring party and doing the thing up in the good old style?"

"I Bee what you mean," he interrupted, his eyes lighting up and the tan on his face deepening. "As an inspiration, Mrs. Kingston, that's just splendid, and I'm sure nothing would delight the duke and Lady Margaret more.

"I'll start on the equipment right away. We can get all we want either here or at Guneston, and we'll just have a royal time. Besides," he added, looking her in the eyes, "there is nothing better than roughing it a bit like that in the mountains to get people better acquainted, something like being on board ship, only better if anything."

"Yes, perhaps it is," she said, smiling and turning her head away. "There's only one thing I'm afraid of, Mr. Marvin. What about Paul? You know, after all, he's only a lad. He's hardly seen any society at all, and nothing on earth like this Lady Margaret as you describe her.

"Suppose now, and you know things like that have happened before, he were to fall madly in love with her, having the very best opportunities for doing so? It would be a terrible thing for him—why, it might ruin the poor boy's whole life. He'd never forgive us—I mean me."

"I quite understand you, Mrs. Kingston, and nobody could sympathize with him better than I could; but don't you worry about the storm before the clouds come along. Paul's got an old head, though it's on young shoulders, and, remember, he has another love already—that invention of his, and, what's more, if that materializes I don't think he'll have to ask even a duke's daughter twice a couple of years or so hence."

"Ah, yes," she said, "if—I know what you mean; that dream of conquering the world with air-ships and the other things he was telling me about. I'm afraid, Mr. Marvin, that there is a very big capital 'I' to that if."

"I'm not so dead sure on that, ma'am," he replied, his nature instantly changing as he thought of the bond which her son had agreed to give. "I've been through those plans and figures, and I'm gambling considerable money on the game myself, and you know I'm not much of a man on wildcat schemes."

NEVER on any continent did five people pass a more delightful time than the pioneers and explorers who had set out from Lake City a few days after the duke and Lady Margaret arrived.

Mr. Marvin, who had taken charge of the expedition with Paul as guide, had got together a lavish equipment of riding and baggage mules, tents, commissariat in liquid and solid form, and cooking apparatus.

They had a couple of peons to look after the animals and pitch and strike the tents, but, on Lady Margaret's suggestion, they had decided to "do" for themselves in the way of cooking and purely domestic arrangements.

They avoided the towns as much as possible, save when it was necessary to make inquiries as to mining prospects or to replenish provisions, and so the greater part of their month's journey lay by choice through the wildest parts of the country.

Their turning point was the summit of Pike's Peak, and when Paul, who was roped in front of Lady Margaret, had helped her up the last few feet, their eyes met and their hands remained clasped for a few moments while she steadied herself on the ice.

The world with all its little social distinctions was far away below them. About them was only the magnificent severity, the unchanging solemnity, and the everlasting silence of sky and mountain.

It was only a moment, but it was enough. If they had been alone—who knows what might have been said when they found breath in the thin, dry air?

But Marvin caught his breath first, and began to congratulate Mrs. Kingston and Lady Margaret, who had already made two very respectable Alpine climbs, on their pluck and endurance.

That broke the spell, and then every one surrendered to another, the spell which falls upon every human being who possesses a soul, the spell of the awful solitude and the utter silence which wraps the crest of every mountain giant.

When they got back to Lake City both what Marvin hoped and Mrs. Kingston feared had taken place. He had made short but ardent work of his wooing, for his love had given him his youth back, and he wooed like a fellow of twenty, and the end was that Shiela Kingston capitulated during a stroll under the pine trees on the evening that their camp was pitched for the last time.

But as a set off to this good happening, Paul came back irrevocably and, apparently in the most literal sense of the word, hopelessly in love with Lady Margaret.

It seemed to him that he was something more than in love with her; but it was his first experience, and so he was quite ignorant of the real heights and depths, the brightness and the gloom, of all that is meant by that most meaning of all words.

Of her social altitude he thought nothing. He was too genuinely American for that, in spite of his English blood.

Moreover, his love seemed to him so vast, so all embracing, that the social difference between them was the tiniest of little spaces in comparison with it.

It may also have been that he was so utterly blinded by her beauty, her girlish grace, and the indescribable charm of her manner, that he literally couldn't see anything else.

Naturally, he kept his secret—which he loved next to Lady Margaret herself—deep buried in the bottom of his heart. Of course, now and then their eyes met in moments of delicious torture to him.

To her they were moments of vague, awakening wonder as to what was happening or was going to happen within that magic fortress which is never entered save by the human soul that dwells in it.

Still, she remembered those moments and the dim, unshaped thoughts which came after them, and when they said good by the memory of them dwelt with her, inseparable somehow from the delightful experiences of the trip from Lake City to Pike's Peak.

That evening Marvin called Paul into the workshop, and Paul came down with a run from the seventh heaven of dreamland to the hard realities of earth when he said to him in his cold business voice:

"Now, young man, we've had a good time, and I guess we'd better get down to work. Have you got that bond drawn out?"

"Yes, I have," replied Paul, taking a paper out of his breast pocket. "I've dated it from the first of the month, the day before yesterday, as I guessed we should be getting to business some time about now."

It might seem curious at first sight that Paul should have given his attention to such a grim bargain as this in the midst of the ardent dreams and the glowing fancies of his first love, and yet the very intensity of his love was the reason for his doing so.

The terms of the bond gave him the only possible chance he could ever have of reaching a position which he could ask Lady Margaret to share with him. If that chance didn't come off, his life was forfeit in two years.

That suited his mood exactly; if he failed, he never could have any hope of winning her, and if he hadn't that, he didn't want to live.

"That's business," said Marvin, taking the paper and running his eye over it. "Yes, I guess there's nothing the matter with that."

He folded the sheet and put it into his pocket, then took out a long envelope and went on: "Now, here's my part of the contract. There is a certificate from the Bank of California that they hold five hundred thousand dollars to your order, and there's your check book. Now you can take your money and use it as soon as you are ready. Have you anything fixed up yet in the way of plans, I mean for construction?"

"Yes," replied Paul. "I shall send complete specifications of different parts, and, for the matter of that, parts of parts, to the best engineering firms in the States, pretty well separated. I shall take care that none of them knows any more than that they are just making certain cranks and shafts and wheels, beds, sockets, and so on of steel and alluminum and iridium of certain shapes and sizes. I shall have these sent to Lake City."

"Well, that is all right so far," said Marvin; "you can leave the choice of the firms to me. I know them all, and they all know me, and I reckon I can drive a harder bargain with them than you can. Besides, they won't do any scrap work for me, although they might for you. And now what about assembling the parts when you've got them?"

"I think I can fix that up all right," said Paul. "Over yonder beside that spur on the other side of the lake there is what is left of a big mine that petered out about five years ago. When it bust up, the people went away and left things standing. There weren't dollars enough left to shift them.

"There's machinery there, though I don't calculate much on that, but there are a lot of big sheds and workshops that will suit me down to the ground. Five hundred dollars will buy the whole outfit, another five or less would repair the place and put the sheds and shops in proper shape. Then I should say, just to choke off curiosity, that I had bought the mine for a trifle from the trustees, and was putting down more machinery just to have another go at it."

"That's OK as far as I can see," said Marvin, "but what about workmen? You'll want some pretty skilled mechanics, won't you?"

"Oh, no. If the manufacturers do their work properly, as of course they will, half a dozen men, with the machinery I shall put down, will answer. In fact, less.

"I shall get a couple of big Chinese laborers from San Francisco to do the pulley-hauling part, then there's a big peon down here, José Montez, who worked for my father and has done several things for us. He'll be very useful. He's as strong as a horse, faithful as a dog, and, curiously enough, though he hasn't got the wit of a mule, he is as good a mechanic as ever held a hammer. You've got to tell just exactly what to do. When he's done that he just comes and asks you what to do next.

"You see, none of these fellows will have any notion what they're doing, and, to make quite sure, when we've got the heavy work done and the hull put together, I shall send the Chinamen away one by one and finish up with José. He will be perfectly safe. He wouldn't know the difference between an air-ship and a prairie schooner if he studied them for a month.

"In fact, I think I shall be quite safe in making him engineer of the ship. She'll only need one man to work her and one to steer."

Marvin put out his hand and said with one of his swift changes of manner, one might almost say nature:

"Sonny, if you don't pull this thing through, no one can, and I believe you will. Now see here, I have another proposition to make. I'm a pretty good hand with the tools, though I haven't done an honest day's work for quite a while now; and a job like that would just fit me better than a Chicago girl's boots fit her feet.

"So, if you let me in, I reckon we will be able to put that little job through without any more help, and without risking more people knowing what we are about."

"Why, certainly!" exclaimed Paul. "I couldn't have anything I like better."

"Except some one with black hair and pansy blue eyes and the prettiest face in the United States," laughed Marvin.

"Well," laughed Paul in reply, "you see, to get her I've got to get this, and if I get this, I guess I'll have her if I have to wreck the British constitution to do it."

Now that everything was settled, Paul Kingston was feverishly anxious to get to work, and so was Gillette Marvin, so the next day they set to in real earnest.

Paul devoted himself to a minute and intricate division of the plans and specifications in duplicate, arranging them so that it would be quite impossible for any maker of a part to form any idea as to what the whole was going to be like.

Marvin went over to the old mine, made a thorough examination of the works, and, finding them just what Paul had said, set quietly to work through one of his agents to buy up the whole concern, which the agent did within a month for the modest sum of two thousand dollars.

He also communicated with twenty of the best engineering firms in the United States, informing them that he had certain mechanical constructions in hand which must be done by their most skilled workmen, sworn to secrecy.

Money was no particular object, but thework must be of the very highest class and nothing said about it. The specifications were then sent off one by one as completed, and when the parts were all in hand, Paul set to work on the submarines, which were to be constructed in similar fashion.

In a month everything was ready at the workshop in the misnamed Canyon de la Plata, in which the played out mine was situated, and within six weeks the parts began to arrive, packed, of course, as machinery at the depot, and were carted across to the canyon on mule wagons.

At first Lake City seemed to be a little curious about the new inventions, but Paul managed to satisfy the questioners by saying that he had been commissioned by a syndicate that had bought the mine to put down machinery and get everything ready for the new workings.

After this Lake City contented itself with saying that as long as he could get fool people to sling their dollars down the old mine with his hands, it was bully for him, and there Lake City's interest in the great enterprise ended.

As soon as the working plan was in place—it consisted mostly of cranes and slings for carrying purposes—and the parts began to arrive, the work of construction started, and the farther it went the greater was the change that developed itself in the two men to whom the completion meant so much.

Paul's nature hardened and became more masterful. He knew perfectly well that his life lay upon the success of his labor, but Marvin's keenest glance never detected the slightest sign of nervousness in him.

The hard, logical determination to do or die, the English side of his character, was coming out more and more strongly every day, while the keenness of wit, quickness of criticism, and readiness of resource which formed his mother's legacy to him, were also brought out in stronger relief.

In fact, Marvin spoke neither more nor less than the truth when he said to Mrs. Kingston one evening as they were walking back alone from the works to their private ferry on the lake:

"Shiela, that son of yours is going to be a big man. Yes, he's going to bring this thing off. What he told you that night in his workroom is true, every word of it. He'll do this thing, and when it's done, well, the world is going to hear something drop, and it won't be that air-ship." As for Marvin himself, the change in him was, if anything, more wonderful still.

The business side of his nature seemed to have receded indefinitely into the background. The sterner, sharper, and more masterful Paul grew, the more boyish and enthusiastic the other became.

He worked like a coolie, and allowed Paul to boss him around as though he had been a nigger, as he put it himself.

If he made suggestions in anticipation of difficulties he foresaw, he was met with a polite rebuff.

"Oh, that's all fixed," or "Don't worry, that will come all right," and he took it as quietly as a schoolboy would have done—perhaps more quietly.

With the exception of keeping his agents up to the mark by mail and wire, he paid no personal attention to his own business.

He was wholly engrossed by his part of the task in bringing to completion the marvelous creation which every day grew bit by bit towards perfection under his eyes and hands; and when his day's toil was over, his nights were gorgeous with splendid dreams of the gold empire of which this wonderful thing which he was helping to make was to be the aerial throne.

At Marvin's request, nothing had been said to Paul about Mrs. Kingston's promise to marry him.

He wouldn't give any definite reason. He just asked it as a favor, and backed it up with the suggestion that the best place to announce it would be on the deck of the new ship when she was making her first demonstration of the conquest of the air.

This, of course, appealed too strongly to her imagination for her to do more than insist on the condition that she was to be on board during the trial trip, for, as she put it gently, but very firmly, if anything happened on that occasion to Paul or her promised husband, it was going to happen to her, too.

At last, after six months of incessant toil, the Shiela, as Paul's mother was to christen her on the eve of her first flight, was very nearly completed.

The Chinese laborers had been dismissed, one by one, each with sufficient dollars to make it absolutely certain that he would at once return to the land of his ancestors.

José stared, uncomprehending, at the shapely, glittering fabric, with its fans and propellers and air planes, with no more admiration or curiosity than if it had been a factory boiler.

Mrs. Kingston looked at it with loving pride and wonder, as though it were, in some sort, an offspring of her own, as indeed it was in a certain sense, for was it not the mental offspring, the very creation, of her own flesh and blood?

As a matter of fact, she was wont afterwards to talk of the Shiela as her steel granddaughter.

Not even José was allowed to see the putting in and adjustment of the last of the mechanical and motive essentials which transferred the Shiela from an inherent mass of machinery into an almost vital organism, capable of motion swifter than a bird's flight, and yet docile as a well trained dog under the hands of her captain and controller.

At last one glorious, crisp morning in the brief southern autumn, Paul said to his mother at breakfast—Marvin had been sleeping for the last few weeks at the works with José, armed with a Colt repeating rifle and a brace of seven shooters to receive any too curious callers:

"Well, mother, we finished her last night, and now she's ready for you to make an official inspection. We tried the motors last night, and everything worked like a charm, though, of course, we didn't raise her, for we have to take the roof off the shed yet. We're going to do that today, and as soon as it is dark enough tonight you shall christen her, and we shall start on the trial trip.

"And do you really think, dear," she said, leaning back in her chair and looking at him, her eyes glowing with love and pride, "do you really think that she will be a success—that she will really fly?"

"I don't think, mother," he said seriously, "I know. I'm gambling nothing on chance this time, there's too much on the game. She will fly, and tonight you shall take a midnight trip across the Sierra de la Plata and back before breakfast."

MRS. KINGSTON'S heart was beating a good deal faster than her son's as they approached the huge shed from which Marvin and José were already removing the roof.

The moon, though beginning to descend towards the saw tooth ridges of the western hills, still gave ample light for what work remained to be done outside.

As Paul opened the door for her to enter she said:

"But, my dear boy, you will never get your ship out through this."

And then as he looked round and laughed, she went on:

"Oh, of course, I forgot. If she goes out at all, she will go through the roof."

"That is the way she is going, mother," replied Paul, "as soon as we have got it off. Now suppose you go aboard and make yourself at home, and 111 turn to and lend a hand."

He opened a door in the side of the long, gray painted hull, which was shaped something like a flattened cigar, save that it was almost as broad at the stern as amidships, and pulled down a light steel telescope ladder.

He went up first and turned a couple of switches in the wall. Instantly the whole interior was lighted by a bright glow, which was everywhere, and yet seemed to come from nowhere.

As he helped his mother up into the lower cabin, or general living room, which was about fifteen feet long by ten broad, she glanced about her with a look of astonishment and said:

"Why, Paul, I haven't seen this before. Where do you get your light from; where are your lamps?"

"Oh, we don't have any lamps," he laughed. "Besides, this is not light in the way you mean. It's my improvement on electricity;'what I call illuminated air. This place is lit just as the atmosphere is lit by the sun, by vibrations set up through radiators; little suns, in fact.

"There they are," he went on, pointing to ten little circles which his mother thought were mirrors.

There were two of them at each end, and three on each side of the room.

"But you must excuse me now; I must get to work. You just make yourself comfortable and have a look round your aerial home. I guess you will find everything comfortable."

The roof of the shed had been built so that the two slopes could be slid off to the ground in sections, running in grooves and operated by pulleys. These were nearly all off when he got outside.

Then the roof tree was taken down in sections, and the inside supports removed. This left the Shiela open to the sky, and all was now ready for the start.

She had three movable air planes on each side. The midship ones measured fifteen feet by twelve, and the fore and after ones narrowed towards the bow and stern, so that their whole outline corresponded to that of the hull.

Under each of these was a lifting fan ten feet in diameter driven by independent motors capable of a thousand revolutions a minute.

There were two ten feet driving fans at the stern, and one with a sweep of eight feet at the bow, each driven by its own motor at speeds varying from fifty to eight hundred revolutions a minute.

Above the hull, amidships, rose a low, oval structure about thirty feet long by ten in its greatest width, paneled all round with plate glass and sliding windows. The middle portion of the roof was also made to slide fore and aft, so that in fine weather the upper cabin could be used as an open air promenade.

In front of this was a smaller oval chamber eight feet long and a little higher than the cabin. This was the conning tower and instrument room, from which the motors could be started and stopped, and every motion of the ship directed.

In fact, as long as the supply of energy, which was derived from refined petroleum by a process of direct conversion, was kept up, one man could manage the ship entirely.

This process had been one of Paul Kingston's uncompleted discoveries which his son had perfected.

In front of the conning tower rose a slender steel signal mast, twenty feet high.

"Now I think we are about ready. José, you can go home now, and mind, on your faith, keep your mouth shut or you'll never open it again."

"Si, señor," replied the huge peon, thrusting his hands into his pockets and lumbering away down the path towards the ferry without taking the trouble to look back at the miracle he was leaving behind him.

While his mother was making a tour of the various apartments, which she had had a considerable share in furnishing according to her own excellent taste, Paul and Marvin gave a thorough final inspection to the motors and driving machinery.

There was no engine-room, for each motor stood in its own compartment, connected by carrying cables of insulated copper strands with the main storage batteries on either side of the ship below the cabin. Nothing more was needed to start or stop them than the making or the breaking of the circuit.

When they were satisfied that everything was in perfect order, Paul called to his mother:

"Now then, if you please, ma'am, come right along to the conning tower and say good by to the earth for an hour or two. We're just off."

There was a little table at the fore end of the room, and on this stood an oblong rosewood board with three switches on it. In the center of the table was a silver wheel with an upright handle and a pointer moving over a semicircle marked out to a hundred and eighty degrees.

This was the steering wheel, and operated a triangular, vertical fan which projected beyond the stern propellers.

Paul put his hand on the center switch and said quite steadily: "This starts the disks. We've had one little struggle with gravity and come out on top. Now we will have a bigger one. Listen."

He turned the switch, and the next moment Mrs. Kingston heard a strange, low, musical, humming sound.

As he moved the handle farther to the right, the sound grew deeper and more intense, and she began to feel an extraordinary sensation of lightness and exhilaration.

"What's the matter, Paul?" she said. "I'm beginning to feel as if I could fly myself."

"So you will in another minute or so," laughed Marvin. "That's what spiritualists call levitation or taking the weight out of things so that they will float in air. They say they do it by spiritual force, Paul, here, does it by pure mechanics.

"We've got two hundred toughened glass disks three feet in diameter whizzing round underneath us, and they are getting up to three thousand revolutions a minute. You see, there isn't the slightest vibration.

"Well, it seems they set up some sort of mysterious force, maybe electrical or something else, that appears to drive the weight out of the ship. See, there's the indicator," he continued, pointing to a little clock hand moving on a dial; "they're getting on. One, fifteen, two, twenty five, that is twenty five hundred three thousand. Now, see here!"

He took Paul by the elbows and lifted him from the floor and set him down again.

"He doesn't weigh a quarter of what he did ten minutes ago."

"May I try, Paul?" exclaimed his mother, half laughing and half frightened. "It's a long time since I carried you."

She put her arms round him, and, to her amazement, lifted him quite easily.

"My!" she exclaimed with a little gasp. "Why, this ship of yours must be a piece of Wonderland, Paul."

"You will see more wonders than that soon, mother," he laughed, putting his hand on the top switch and moving it slightly to the left.

Instantly a low whirring sound pierced through the hum of the disks.

"Those are the lifting fans making that noise," he said.

He put the switch over a little more, and the whirring grew shriller. Then, to his mother's marvel and delight, she saw the walls of the shed begin to sink below them.

She didn't say anything. Her mother heart was too full of joy and pride for speech.

She put her arms round Paul's neck and kissed him, and then with a murmured "Thank God!" she burst into tears.

Paul's eyes were wet, too, and, as a matter of fact, so were Marvin's. He turned the switch back and the ship sank slowly into the shed.

Tears of joy soon pass, and smiles come quickly after them, as the sun after a summer shower, and ten minutes afterwards the three were standing outside the shed beside the bow.

Mrs. Kingston had in her hand a bottle of champagne, slung by a cord to the upper rail. Paul and Marvin stood on either side of her, bare-headed.

She drew the bottle towards her, and said in a low voice, which trembled with emotion:

"You were created by the genius of my husband and my son. Take the name of their wife and mother, and bear it stainless to the skies!"

"Amen!" said Paul and Marvin with one breath.

She let go the bottle, and the golden wine streamed down the Shiela's side, and so, with much simple ceremony, was the first conqueror of the air christened.

"Now I think it is about dark enough to make a start," said Marvin when they got back into the upper cabin. "The moon will be down in ten minutes. It's nearly twelve o'clock, and I guess there aren't many people looking this way."

"Start it is!" said Paul. "Come along, mother; we're going to fly in real earnest this time."

"Fly!" she echoed, as she followed them into the conning tower. "Why, it's like a dream—and so it is, the dream of ages, and you've made it real. If there's another woman in the world happier tonight than I am, I don't envy her."

"I should think not," said Marvin, looking at her with frank fondness. "It isn't every woman who has a son that can make her mistress of the air."

Paul went hack to the switch hoard. The disks were still running three thousand revolutions a minute.

He turned the upper switch again, this time more quickly. The whirring sound broke out louder and shriller than before. The walls of the shed again sank below them, but this time out of sight.

The tops of the cliffs round the canyon came nearer to them; then these, too, sank.

Presently the lake and Lake City came into view. The water shone a bluish white under the stars, and the white painted houses of the town showed gray against the dusky gloom of the pines around it.

The Shiela mounted swiftly, higher and higher in a direct vertical line, until the hills, too, commenced to sink and the snowy peaks of the Sierra Blanca began to show above them.

No one spoke. It wasn't a time for talking, but just for looking and wondering, and so for nearly half an hour there was silence in the conning tower until Paul said in a low tone:

"I think we might try the propellers now. Keep your eye on the speed gage, Mr. Marvin, please, and we'll see what she can do."

The speed gage was an apparatus almost exactly like the one used for measuring the force of wind, and it communicated with a dial inside the room.

Paul put his hand on the lower switch and turned it slowly towards the right. Mrs. Kingston saw the fore propeller begin to revolve. It spun faster and faster until it became a dim circle, almost invisible in the starlight.

She looked astern and saw that the after propellers had also disappeared. Then Marvin began counting the miles off the dial.

"Twenty, thirty, forty, fifty," he read out in quick succession.

Lake City had vanished, and they were within a few miles of the eastern hills, ever rising.

"I'll try the planes now," said Paul, taking hold of a lever to the right of the table which worked in a graduated ratchet.

He pulled it slightly towards him, and the ridge of the hills instantly sank.

"That is all right," he said. "Now I think we can do without the fans."

He turned back the top switch and put the propellers on three quarters power.

"Sixty—seventy five—ninety—a hundred! Good!" exclaimed Mr. Marvin. "Bully for you, Paul. You've won. Shake!"

Paul let go the lever and gripped his hand while Mrs. Kingston exclaimed:

"What, not a hundred miles an hour! Surely, that can't be possible. We don't seem to be moving at all."

"Yes," said Paul, "that's it. Look down at the earth and these hills. See, now I'm going to jump them."

He pulled the lever a few degrees towards him. The hills rushed towards them and sank down. The next minute they were far astern, almost out of sight. The lofty peaks of the Sierra Blanca rose in front of them for an instant, then they too sank down and fell astern.

Paul looked at the barometer and said:

"Eight thousand, five hundred. I guess that will do for tonight. If she can soar that, she can soar fifteen, and now we'll see how she steers."

He turned the wheel ever so slightly, and the Shiela swept round in a swift and splendid curve.

He slowed her down to fifty miles and began to put her through her paces, turning and curving and strolling round the peaks with bewildering rapidity, until he was satisfied that he had her under complete control.

"Magnificent!" said Marvin at the end of half an hour of wondering silence. "But look here, Paul, it is after two o'clock. I think we had better be getting home."

"Yes, dear, I think we had," added his mother. "I've seen wonders enough for one night. I'm nearly dizzy with them, and I shall be glad to get to bed and dream of them."

"OK," said Paul, with a glance at the compass in front of him. "Northwest by north is the course from here, and full speed it is. We'll be home inside the hour. Mother, you're mistress here, suppose you go and get us a bottle of wine and a cold pie. I'm growing hungry."

There was nothing to be seen of the earth except a dim blur as the Shiela rushed through the air at her full speed of a hundred and fifty miles an hour. After fifty minutes' run Paul slowed down to twenty five and started the fans. In five minutes the lake came in sight, and in ten more the Shiela was resting on the stocks in the shed and they were walking to the ferry.

The next morning after breakfast Marvin asked Paul to come into the workroom, and said to him as he took the bond of death out of his pocket:

"Paul, sonny, you've done it, and I haven't got any more use for this."

He tore the bond in two pieces and gave them to Paul.

"Of course I didn't mean anything about that life clause except that, of course, I meant to see that you were in dead earnest and had the proper sort of grit before I gambled my money on your ideas. And now I'll tell you why, and I hope the news won't be unpleasant to you.

"I've loved your mother ever since I met her first. Naturally, I kept my head shut, as any gentleman would, but when I came down here seven months ago it was with her permission to win her if I could. Well, I've done it, but she won't say 'yes' unless you do. Now what do you say?"

"Yes, with all my heart," said Paul, putting out his hand, "but I think you're the only man I would say 'yes' to, and the only one she would say 'yes' to."

"Thank you, lad," said Marvin simply as he gripped the hand. "Well, now we're partners for good and all, partners against the whole world if need be. Come along and tell her, and we will have a wedding next week."

Nothing was of course more natural or inevitable than that the honeymoon trip should be taken in the Shiela under the care of Captain Paul, as Marvin had now dubbed him.

The air-ship had made several night voyages since her trial trip, for the purpose of testing her machinery thoroughly and proving her speed and soaring powers and her fuel consumption.

It was found that, using both fans and air planes, she could rise comfortably to twenty thousand feet. Her utmost speed in calm, dense air was a hundred and sixty miles an hour, and her fuel consumption averaged fifty pounds weight of petroleum per thousand miles, which about verified Professor Cayley's calculations that if all the solar energy that is stored up In coal could be extracted and applied directly, as Paul's petroleum energy was, a clothes basket full of coal dust would suffice to drive the Scotch express at full speed from London to Edinburgh.

A start was made the third night after the wedding. José was left in charge of the works, with orders to say nothing save that Paul and his mother had gone on a trip to Europe.

There was no moon, and the Shiela soared into space and darted away southward without being seen. By day she traveled either well out to sea or at a sufficiently high altitude to make it impossible to see her.

The course of the trip was naturally left to the choice of the bride, and she selected a run along the great mountain chain of Central and South America, from the tropics down to the desolation of Tierra del Fuego.

Never was a woman's choice of more moment to the fortunes of humanity.

They had made a run of five thousand miles in about ten days, and were skirting the mountains of Patagonia between the forty fifth and fiftieth parallels of south latitude. It was a brilliantly moonlight night in the middle of the far southern summer when Mrs. Marvin, who was standing with her husband in the upper cabin, watching the somber shapes of the mountains as they flitted past a few hundred feet below them, suddenly pointed forward and downward to the right hand side.

"Look, Gillette," she said, "isn't that a lake yonder? See, right in the top of that mountain—and look, it's smoking! It must be a volcano."

Her husband looked, but he didn't speak for a few minutes.

There was something very extraordinary about the surface of the lake that was troubling him.

It was not the light steamy vapor that was rising from it, but a strange metallic glint which the waters showed where the moonlight fell upon them.

"I see," he said, "a lake in the crater of a volcano. Curious, though; they don't have takes in the craters of active volcanoes. I'll go up and tell Paul. I reckon it's a bit of a curiosity which is worth investigating."

But Paul had already noticed the strange appearance of the lake, and he had flowed down the Shiela and headed her towards the mysterious mountain.

He put his head through the door of the conning tower and said:

"See that lake yonder? What is it? Doesn't look like water to me, something more like metal. I guess we had better go and prospect."

"By thunder, you've got it!" exclaimed Marvin. "That volcano is active. How could it have water in it? Why, certainly we'll prospect. I'm on metals every time, hot or cold."

Paul brought the Shiela to a rest on a little sandy level beside the crater wall, but they found it impossible to descend the other side towards the lake. The acrid, suffocating fumes compelled them to go back at once.

It was impossible to breathe within twenty yards of the edge of the lake.

"No mistake what that smell is," said Paul. "That's chlorine, and the lake is metallic; no doubt about that. Now, how are we going to get some of it? Ah, yes, I've got it. Come back into the ship."

He found a small iron bucket and a thin wire cord about a hundred feet long, made one end fast to the bucket and the other to the rail by the gangway door.

Then they closed up the Shiela until she was practically air tight, rose and passed over the lake. Then they dropped till the bucket fell on the surface.

It lay there as if it had fallen on rock.

Paul made the Shiela take a little jump forward, the lip of the bucket caught in the fluid and the vessel was dragged under.

"Got it!" said Paul as he turned the switch and the Shiela rose up out of the hot steaming vapors.

When they got back into pure air Marvin opened the door and hauled the bucket up about three parts full of a greenish, yellowish fluid which was rapidly turning into yellowish white powder.

"It's mighty heavy," he said as he brought the bucket on board. "Why, darn it, it has gone solid into a powder! Here, Paul, you're a better chemist than I am. Take a look at it."

Paul smelt it, picked some out in a spoon, and when it was cool enough rubbed it with his finger; then he said rather unsteadily:

"Mother, go and get me some boiling water and a basin."

"What's the matter?" said Marvin. "Do you think it's worth anything?"

"Think so; can't say yet," he replied shortly.

Mrs. Marvin came back from the kitchen with a kettle of boiling water and a china basin. Paul tipped out several spoonfuls into the basin, poured the water on the powder, stirred it up for two or three minutes, and strained the water off. The powder had now changed to a deep red crystalline color and form. His hand trembled a little as he scraped this aside with the spoon.

Underneath it lay a layer of what looked like dull yellow mud.

"I thought so," he said. "That lake is full of aurous chloride, and that," he went on, stirring the yellow mud, "is pure, finely divided gold and water. There's enough in that lake to buy the earth!"

NO one said anything for over a minute. They just looked at one another and the few spoonfuls of liquid gold.

Paul had put in less than a handful of the whitey yellow powder, and yet there was half an ounce of gold in the basin.

"Are you sure, Paul?" said his mother. "Gold! That can't be possible, can it? No one ever saw gold in such quantities as there must be there."

"You've hit it there, Shiela," said her husband. "No one ever did see it before, and that is just where our luck, our wonderful, amazing, incredible luck, comes in. Why, Caesar's ghost, there must be hundreds of tons of it in that lake! What do you say, Paul—when you've come out of your trance?"

"Yes, it's gold," he replied in a half dreaming tone, "and there's gold in this, too," he went on, taking up a spoonful of the red crystals. "Not so much, but still plenty. This is the trichloride. It will melt away of itself soon, and then we can evaporate the gold out.

"And about the quantity—oh, yes, I beg your pardon. Of course there must be thousands and thousands of tons of it there, and the proportion of gold will be about eighty five per cent by weight, perhaps more.

"Well, mother, you remember I asked you would you like to be Mistress of the World. Now you are, for if we go third shares you'll have plenty to buy it, if you want it."

"Well," said Marvin in his practical voice, "Shiela, I guess we've got to congratulate you on the first result of your name child's maiden voyage so far. We three are the richest people on earth now.

"In fact, we're so rich that money hasn't any more meaning for us. We can just play with it, and raise such a high toned sort of Cain in the financial world that I guess they will soon be glad to let us do what we like.

"Why, Dumont Lawson and his steel trust is a small tradesman compared with us now. I owe that gentleman one, and John D. Rockefeller another, and now they shall have it where the turkey got the ax—right in the neck.

"Now suppose we turn to and see how much gold we've got here in this bucket. We'll take it down to the kitchen and wash it out there. Great Scott, what would the old Forty Niners have thought of washing gold out like this—half an ounce from a handful!"

There was plenty of hot water in the boiler of the electric stove on which Mrs. Marvin did her cooking. She got out two large basins, and they proceeded to wash out the contents of the bucket.

When they had separated the suspended gold from the red crystals, Paul asked his mother for a saucepan, tipped the gold into it, and said as he gave it back to her:

"There, mother, put that on the stove. I guess you never had a more valuable stew than that. You've got about two pounds and a half of pure gold there—twenty four carat. Say, you've got eighty ounces at twenty one dollars an ounce, so you see that pot is worth over eight hundred dollars. Just steam the water off and you will have it in powder."

"I could go on cooking like this all day," laughed his mother. "Fancy eight hundred dollars in about five minutes."

"Yes, and we've got this stuff now," said Paul, stirring up the red crystals. "We can't treat this here, though, because we'll have to rig up a furnace with a flue to carry off the chlorine gas. That's what stopped us getting into the crater, and if any one else has found this lake before, I reckon it would have driven them off, too."

"And a mighty good thing for us," added Marvin, "but anyhow, they hadn't a genius with them, and I reckon they didn't come exploring in an air-ship. If it hadn't been for the Shiela we'd never have known what was in that lake, even if we had found it. How do you feel as a billionaire?"

"Mighty hungry," said Paul. "Mother, I guess that stew of yours is about cooked now, and supper or breakfast or whatever it is wouldn't be a bad thing just now."

All the water had been driven off, and the bottom of the saucepan was covered with a thick layer of yellow powder, almost impalpably fine. In fact, when Paul poured it gently out into a soup plate some of it rose in the air.