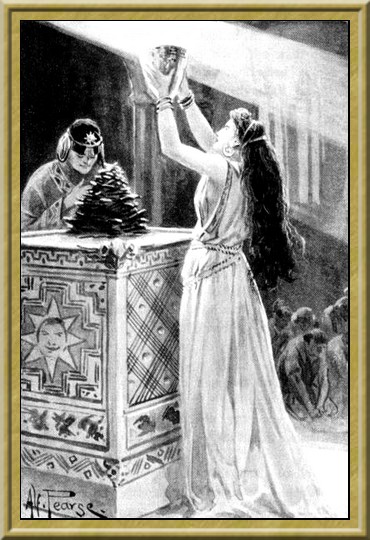

Frontispiece - "Hail, son of the Sun!"

To that Son of the Sacred Race who for Honour and Faith and Love shall take the hand of a pure virgin of his own holy blood and with her pass fearless through the Gate of Death into the shadows which lie beyond shall be given the glory of casting out the Oppressor and raising the Rainbow Banner once more above the Golden Throne of the Incas. On that Throne he shall sit and wield power and mete out justice and mercy to the Children of the Sun when the gloom that is falling upon the Land of the Four Regions shall have passed away in the dawn of a brighter age.

—THE PROPHECY CONTAINED IN THE

ANCIENT LEGEND OF

VILCAROYA-INCA AND GOLDEN STAR, HIS SISTER-BRIDE.

'Ah, what a thing it would be for us if his Inca Highness were really only asleep, as he looks to be! Just think what he could tell us—how easily he could re-create that lost wonderland of his for us, what riddles he could answer, what lies he could contradict. And then think of all the lost treasures that he could show us the way to. Upon my word, if Mephistopheles were to walk into this room just now, I think I should be tempted to make a bargain with him. Do you know, Djama, I believe I would give half the remainder of my own life, whatever that may be, to learn the secrets that were once locked up in that withered, desiccated brain of his.'

The speaker was one of two men who were standing in a large room, half- study, half-museum, in a big, old-fashioned house in Maida Vale. Wherever the science of archoeology was studied, Professor Martin Lamson was known as the highest living authority on the subject of the antiquities of South America. He had just returned from a year's relic-hunting in Peru and Bolivia, and was enjoying the luxury of unpacking his treasures with the almost boyish delight which, under such circumstances, comes only to the true enthusiast. His companion was a somewhat slenderly-built man, of medium height, whose clear, olive skin, straight, black hair, and deep blue-black eyes betrayed a not very remote Eastern origin.

Dr Laurens Djama was a physiologist, whose rapidly-acquired fame— he was barely thirty-two—would have been considered sounder by his professional brethren if it had not been, as they thought, impaired by excursions into by-ways of science which were believed to lead him perilously near to the borders of occultism. Five years before he had pulled the professor through a very bad attack of the calentura in Panama, where they met by the merest traveller's chance, and since then they had been fast friends.

They were standing over a long packing-case, some seven feet in length and two and a-half in breadth, in which lay, at full length, wrapped in grave- clothes that had once been gaily coloured, but which were now faded and grey with the grave-dust, the figure of a man with hands crossed over the breast, dead to all appearances, and yet so gruesomely lifelike that it seemed hard to believe that the broad, muscular chest over which the crossed hands lay was not actually heaving and falling with the breath of life.

The face had been uncovered. It was that of a man still in the early prime of life. The dull brown hair was long and thick, the features somewhat aquiline, and stamped even in death with an almost royal dignity. The skin was of a pale bronze, though darkened by the hues of death. Yet every detail of the face was so perfect and so life-like that, as the professor had said, it seemed to be rather the face of a man in a deep sleep than that of an Inca prince who must have been dead and buried for over three hundred years. The closed eyes, though somewhat sunken in their sockets, were the eyes of sleep rather than of death, and the lids seemed to lie so lightly over them that it looked as though one awakening touch would raise them.

'It is beyond all question the most perfect specimen of a mummy that I have seen,' said the doctor, stooping down and drawing his thin, nervous fingers very lightly over the dried skin of the right cheek. 'On my honour, I simply can't believe that His Highness, as you call him, ever really went to the other world by any of the orthodox routes. If you could imagine an absolute suspension of all the vital functions induced by the influence of something—some drug or hypnotic process unknown to modern science, brought into action on a human being in the very prime of his vital strength —then, so far as I can see, the results of that influence would be exactly what you see here.'

'But surely that can't be anything but a dream. How could it be possible to bring all the vital functions to a dead stop like that, and yet keep them in such a state that it might be possible—for that's what I suppose you are driving at—to start them into activity again, just as one might wind up a clock that had been stopped for a few weeks and set it going?'

'My dear fellow, the borderland between life and death is so utterly unknown to the very best of us that there is no telling what frightful possibilities there may be lying hidden under the shadows that hang over it. You know as well as I do that there are perfectly well authenticated instances on record of Hindoo Fakirs who have allowed themselves to be placed in a state of suspended animation and had their tongues turned back into their throats, their mouths and noses covered with clay, and have been buried in graves that have been filled up and had sentries watching day and night over them for as long a period as six weeks, and then have been dug up and restored to perfect health and strength again in a few hours. Now, if life can be suspended for six weeks and then restored to an organism which, from all physiological standpoints, must be regarded as inanimate, why not for six years or six hundred years, for the matter of that? Given once the possibility, which we may assume as proved, of a restoration to life after total suspension of animation, then it only becomes a question of preservation of tissue for more or less indefinite periods. Granted that tissue can be so preserved, then, given the other possibility already proved, andwell, we will talk about the other possibility afterwards. Now, tell me, don't you, as an archaeologist, see anything peculiar about this Inca prince of yours?'

The professor had been looking keenly at his friend during the delivery of this curious physiological lecture. He seemed as though he were trying to read the thoughts that were chasing each other through his brain behind the impenetrable mask of that smooth, broad forehead of his. He looked into his eyes, but saw nothing there save a cold, steady light that he had often seen before when the doctor was discussing subjects that interested him deeply. As for his face, it was utterly impassive—the face of a dispassionate scientist quietly discussing the possible solution of a problem that had been laid before him. Whether his friend was really driving at some unheard-of and unearthly solution of the problem which he himself had raised, or whether he was merely discussing the possible issue of some abstract question in physiology, he was utterly unable to discover, and so he thought it best to confine himself to the matter in hand, without hazarding any risky guesses that might possibly result in his own confusion. So he answered as quietly as he could:

'Yes, I must confess that there are two perhaps very important points of difference between this and any other Peruvian mummy that I have ever seen or heard of.'

'Ah, I thought so,' said Djama, half closing his eyes and allowing just the ghost of a smile to flit across his lips. 'I thought I knew enough about archæology and the science of mummies in general to expect you to say that. Now, just for the gratification of my own vanity, I should like to try and anticipate what you are going to say; and if I'm wrong, well, of course, I shall only be too happy to be contradicted.'

'Very well,' laughed the professor; 'say on!'

'Well, in the first place, I believe I'm right in saying that all Peruvian mummies that have so far been discovered have been found in a sitting posture, with the legs drawn close up to the body by means of bindings and burial-clothes, so that the chin rested between the knees, while the arms were brought round the legs and folded over them. Then, again, these mummies have always been found in an upright position, while you found this one lying down.'

'Quite so, quite so!' said the professor. 'In fact, I may say that no one save myself has ever discovered such a mummy as this among all the thousands that have been taken out of Peruvian burying-places. And now, what is your other point?'

'Simply this,' said Djama, kneeling down beside the case, and laying his hands over the abdomen of the recumbent figure. 'In the case of all mummies, whether Egyptian or Peruvian, it was the invariable practice of the embalmers to take out the intestines and fill the abdominal cavity with preservative herbs and spices. Now, this has not been done in this case. Look here.'

And deftly and swiftly he moved the dusty, half-decayed coverings from the body of the mummy, while the professor looked on half-wondering and half- frightened for the safety of his treasure.

'That has not been done here. You see the man's body is as perfect as it was on the day he died—to use a conventional term. Now, am I not right?'

'Yes, yes; perfectly right,' answered the professor, who felt himself fast losing his grip of the conversation which had taken so strange a turn. 'But what has all this got to do with the most unique mummy that ever was brought from South America? Surely, in the name of all that's sacred, you don't mean-'

'My dear fellow, never mind what I mean for the present,' replied Djama, with another of his half smiles. 'If I mean anything at all, the meaning will keep, and if I don't it doesn't matter. Now, do you mind telling me exactly how and where you came across this extraordinary specimen of—well, for want of a better term—we will say, Inca embalming?'

'Yes, willingly,' said the professor, glad to get back again on to the familiar ground of his own experiences. 'I found it almost by accident in a little valley about four days' ride to the westward of Cuzco. I was on my way to Abancay across the Apurimac. My mule had fallen lame, and so I got belated. Night came on, and somehow we got off the track crossing one of the Punas—those elevated tablelands, you know, up among the mountains —and when the mule could go no farther we camped, and the next morning I found myself in an almost circular valley, completely walled in by enormous mountains, save for the narrow, crooked gorge through which we had stumbled by the purest accident. The bottom of this valley was filled by a little lake, and while I was exploring the shores of this I saw, hidden underneath an overhanging ledge of rock, a couple of courses of that wonderful mortarless masonry which the Incas alone seemed to know how to build. I had no sooner seen it than all desire of getting to Abancay or anywhere else had left me. I made my arriero turn the animals loose for the day, and then I sent him back to a village we had passed through the day before to buy more provisions and bring them to me.

'As soon as he had got out of sight I set to work to get some of the stones out and see what there was behind them. I knew there must be something, for the Incas never wasted labour. It was hard work, for the stones were fitted together as perfectly as the pieces of a Chinese puzzle; but at last I got one out and then the rest was easy. Behind the stones I found a little chamber hollowed out of the rock, perfectly clean and dry, and on the floor of this I found, without any other covering than what you see there, the mummy of His Highness lying on what had once been a bed of soft Vicuna skins, as perfect and as lifelike as though he had only crept in there twelve hours before, and had laid down for a good night's rest.

'You may imagine how delighted I was at such a find. I hardly knew how to contain myself until my man came back. I put the stones back into their places as well as I could, and when Patricio returned the next day I had the animals saddled up, and started off in a hurry to Cuzco. There I had this case made, bought two extra mules, brought them to the valley, packed up my mummy, took it back to Cuzco, and from there to the railway terminus at Sicuani and took it down by train to Arequipa, where I left it in safe keeping until I had finished the rest of my exploration. Then I went back, took it down to Mollendo, got it on board the steamer, and here it is.'

'And you didn't find any traces of other treasure-places, I suppose, in the valley?' said Djama, who had listened with the most perfect attention to the professor's story.

'No, I didn't, though I must confess that one side of the cave in which I found this was walled up with the same kind of masonry as there was in front of it; but, to tell you the truth, the Peruvian Government has such insane ideas about treasure-hunting; and the life of a man who is believed to have discovered anything worth stealing is worth so little in the wilder districts of the interior, that I was afraid of losing the treasure I had got, perhaps for the sake of a few little gold ornaments which I might have dug out of the hill, and so I decided to be content with what I'd found.'

H'm!' said the doctor. 'Well, you may have been wise under the circumstances; I daresay you were. But we can see about that afterwards. Meanwhile there is something else to be talked about.'

He stopped suddenly, took a quick turn or two up and down the room, with his hands clasped behind him and his eyes fixed on the floor. Then he went to the door, opened it, looked out, shut it and locked it, and then came back again and sat down without a word in his chair, staring steadily at the impassive face of the mummy in the packing—case.

'Why, what's the matter, doctor?' said the professor, a trifle sharply. 'You don't suppose I am afraid of anyone coming to steal my treasure, do you?'

'My dear fellow,' said Djama, looking him straight in the eyes, and speaking very slowly, as though his mind was doing something else besides shaping the thoughts to which he was giving utterance, 'I don't for a moment suppose that there are thieves about, or that, if there were, any burglar with a competent knowledge of his profession would think of stealing your mummy, priceless as it may prove to be. I locked the door because I don't want to be interrupted. I want to talk to you about a very important matter.'

'And that is?'

'Mephistopheles.'

'WHAT?'

'Gently, my friend, gently, don't get excited yet. You will want all your nerves soon, I can assure you. Yes, I am quite serious. You know that in the good old days, when people still believed in His Majesty of Darkness, such a speech as the one you remember making a short time ago was quite enough to call up one of his agents, armed with full powers to make contracts and do all necessary business.'

'Look here, Laurens, if you go on talking like that, I shall begin to think you have gone out of your mind.'

'My dear fellow, to be quite candid with you, I don't care two pins what you think on that subject. I have been called mad too many times for that. Now, suppose, just for argument's sake, that I were Mephistopheles, and staked my diabolic reputation on the statement that in that thing you possess a possible key to those lost treasures of the Incas, which ten generations of men have hunted for in vain, what kind of a bargain would you be inclined to make with me on the strength of it? Half the rest of your life, I think you said, and as that wouldn't be very much good to me, suppose we say the half of any treasures we may discover by the help of our silent friend there? Eh? —will that suit you?'

'Are you really serious, Djama, or are you only dreaming another of these wild scientific dreams of yours?' exclaimed the professor, taking a couple of quick strides towards him. 'What connection can there possibly be between a mummy, about four centuries years old, and the lost treasures of the Incas?'

'This man was an Inca, wasn't he?' said the doctor, abruptly, 'and one of the highest rank, too, from what you have said. He lived just about the time of the Conquest, didn't he—the time when the priests stripped their temples, and the nobles emptied their palaces of their treasures to save them from the Spaniards? Is it not likely that he would know where, at anyrate, a great part of them was buried? Nay, may he not even have known the localities of the lost mines that the Incas got their hundredweights of gold from, and of the emerald mines which no one has ever been able to find? Why, Lamson, if these dead lips could speak, I believe they could make you and me millionaires in an hour. And why shouldn't they speak?'

'Don't talk like that, Djama, for Heaven's sake! It is too serious a thing to joke about,' said the professor, with a half-frightened glance in his set and shining eyes. 'I should have thought you, of all men, knew enough of the facts of life and death not to talk such nonsense as that.'

'Nonsense!' said the physiologist, interrupting him almost angrily; 'may I not know enough of the facts of life and death, as you call them, to know that that is not nonsense? But there, it's no use arguing about things like this. Will you allow this mummy of yours to be made the subject of— well, we will say, an experiment in physiology?'

'What! the finest and most unique huaca that was ever brought to Europe- '

'It would only be made finer still by the experiment, even if it failed. I know what you are going to say, and I will give you my word of honour, and, if you like, I'll pledge you my professional reputation, that not a hair of its head shall be injured. Let me take it to my laboratory, and I promise you solemnly that in a week you shall have it back, not as it is now, but either the body of your Inca, as perfect as it was the day he died, or-'

He stopped, and looked hard at his friend, as if wondering what the effects of his next words would be upon him.

'Or what?' asked the professor, almost in a whisper.

'Your Inca prince, roused from his three-hundred-year sleep, and able to answer your questions and guide us to his lost mines and treasure houses.'

'Are you in earnest, Djama?' the professor whispered, catching him by the arm and looking round at the mummy as though he half thought that the silent witness in the packing-case might be listening to the words which, if it could have heard, would have had such a terrible significance for it. 'Do you really mean to say in sober earnest that there is the remotest chance of your science being able to work such a miracle as that?'

'A chance, yes,' replied Djama, steadily. 'It is not a certainty, of course, but I believe it to be possible. Will you let me try?'

'Yes, you shall try,' answered the professor in a voice nothing like as steady as his. 'If any other man but you had even hinted at such a thing, I would have seen him—well, in a lunatic asylum first. But there, I will trust my Inca to you. It seems a fearful thing even to attempt, and yet, after all, if it fails there will be no harm done, and if it succeeds— ah, yes, if it succeeds—it will mean-'

'Endless fame for you, my friend, as the recreator of a lost society, and for both of us wealth, perhaps beyond counting. But stop a moment— granted success, how shall we talk with our Inca revenant? Have I not heard you say that the Aymaru dialect of the Quichua tongue is lost as completely as the Inca treasures?'

'Not quite, though I believe I am now the only white man on earth who understands it.'

'Good! then let me get to work at once, and in a week—well, in a week we shall see.'

Laurens Djama dined with the professor that night, and the small hours were growing large before they ended the long talk of which their strange bargain, and the still stranger experiment which was to result from it, formed the subject. The next day the packing-case containing the mummy was transferred to Djama's laboratory, and then for a whole week neither the professor nor any of his friends or acquaintances had either sight or speech of him.

Every caller at his house in Brondesbury Park was politely but firmly denied admittance on professional grounds, and three letters and two telegrams which the professor had sent to him, after being himself denied admittance, remained unanswered.

At last, on the Thursday following the Friday on which the mummy had been sent to the laboratory, the professor received a telegram telling him to come at once to the doctor. Three minutes after he had read it he was in a hansom and on his way to Kilburn, wondering what it was that he was to be brought face to face with during the next half hour.

This time there was no denial. The door opened as he went up the steps, and the servant handed him a note. He tore it open and read,—

'Come round to the laboratory and make a new acquaintance who will yet be an old one.'

His heart stood still, and he caught his breath sharply as he read the words which told him that the unearthly experiment for which he had furnished the subject had been successful.

The doctor's laboratory stood apart from the house in the long, narrow garden at the back, and as he approached the door he stopped for a moment, and an almost irresistible impulse to go away and have nothing more to do with the unholy work in hand took possession of him. Then the love of his science and the longing to hear the marvels which could only be heard from the lips that had been silent for centuries overcame his fears, and he went up to the door and knocked softly.

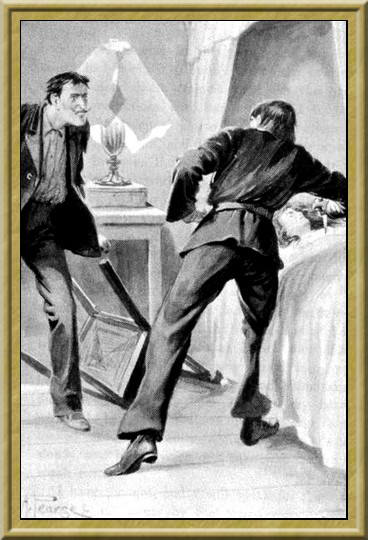

It was opened by a haggard, wild-eyed man, whom he scarcely recognised as his old friend. Djama did not speak; he simply caught hold of the sleeve of his coat with a nervous, trembling grasp, drew him in, shut the door, and led him to a corner of the room where there was a little camp bed, curtained all round with thin, transparent muslin, through which he could see the shape of a man lying under the sheets.

Djama pulled the curtain aside, and said in a hoarse whisper,—

'Look, it has been hard work, and terrible work, too, but I have succeeded. Do you see, he is breathing!'

The professor stared wide-eyed at the white pillow on which lay the head of what, a week before, had been his mummy. Now it was the head of a living man; the pale bronze of the skin was clear and moist with the dew of life; the lips were no longer brown and dry, but faintly red and slightly parted, and the counterpane, which was pulled close up under the chin, was slowly rising and falling with the regular rhythm of a sleeper's breathing. He looked from the face of him who had been dead and was alive again to the face of the man whose daring science and perfect skill had wrought the unholy miracle, and then he shrank back from the bedside, pulling Djama with him, and whispering,—

'Good God, it is even more awful than it is wonderful! How did you do it?'

'That is my secret,' whispered Djama, his dry lips shaping themselves into a ghastly smile, 'and for all the treasures that that man ever saw, I wouldn't tell it to a living soul, or do such hideous work again. I tell you I have seen life and death fighting together for two days and nights in this room—not, mind you, as they fight on a deathbed, but the other way, and I would rather see a thousand men die than one more come back out of death into life. You see, he is sleeping now. He opened his eyes just before daybreak this morning—that's nearly ten hours ago—but if I lived ten thousand years I should never forget that one look he gave me before he shut them again. Since then he has slept, and I stood by that bed testing his pulse and his breathing for eight hours before I wired you. Then I knew he would live, and so I sent for you.'

The professor looked at his friend with an involuntary and unconquerable aversion rising in his heart against him; an aversion that was half fear, half horror, and then he remembered that he himself had a share in the fearful work which had been done—a work that could not now be undone without murder.

With another backward look at the bed, he said, in a whisper that was almost a smothered groan,—

'When will he wake?'

Before Djama could reply, the question was answered by a faint rustle, and a low, long-drawn sigh from the bed. They looked and saw the Inca's face turned towards them, and two fever-bright eyes shining through the curtains.

'He is awake already, two hours sooner than I expected,' said Djama, in a voice that he strove vainly to keep steady. 'Come, now, you are the only man on earth who can talk to him. Let us see if he has come back to reason as well as to life.'

'Yes, I will try,' said the professor, faintly. He took a couple of trembling steps. Then the lights in the room began to dance, the whitewashed walls reeled round him, and he pitched forward and fell unconscious by the side of the bed.

When he came to himself he was lying on the floor of the laboratory, out of sight of the bed, behind a great cupboard, glass-doored and filled with bottles. Djama was kneeling beside him. A strong smell of ammonia dominated the other smells peculiar to a laboratory, and his brow was wet with the spirit that Djama was gently rubbing on it with his hand.

'What have I been doing?' he said, as, with the other's assistance, he got up into a sitting position and looked stupidly about him. 'It isn't true, that is it, I really saw—Good God no, it can't be; it's too horrible. I must have dreamt it.'

'Nonsense, my dear fellow, nonsense! I should have thought you would have had better nerves than that. Come, take a nip of this, and pull yourself together. There is nothing so very horrible about it for you. Now, if you had had the actual work to do-'

'Then it is true! You really have brought him back to life again? That was him I saw lying on the bed?' He looked up at Djama as he spoke with a half- inquiring, half-frightened glance. His voice was weak and unsteady, like the voice of a man who has been stunned by some terrible shock, and is still dazed with the fear and wonder of it.

'Yes, of course it was,' said Djama; 'but I can tell you, I should have hesitated before I introduced you so suddenly, if I hadn't thought that the nerves of an old traveller like you would have been a good deal stronger than they seem to be. It's a very good job that His Highness was only about half conscious himself when you collapsed, or you might have given him a shock that would have killed him again.'

'Again?' said the professor, echoing the last word as he got up slowly to his feet. 'That sounds queer, doesn't it, to talk of killing a man again? I am more sorry than I can say that I was weak enough to let my feelings overcome me in such a ridiculous fashion. However, I am all right now. Give me another drain of that brandy of yours, and then let us talk. Is he still awake?'

'No, he dozed off again almost immediately, and you have been here about ten minutes or a quarter of an hour. Do you think you can stand another look at him?'

'Oh, certainly,' said the professor, who, as a matter of fact, felt a trifle ashamed of himself and his weakness, and was anxious to do something that would restore his credit. He followed the doctor out into the laboratory again, and stood with him for some moments without speaking by the Inca's bedside. He was sleeping very quietly, and his breathing seemed to be stronger and deeper than it had been. He had slightly shifted his position, and was lying now half turned on his right side, with his right cheek on the pillow.

'You see he has moved,' whispered Djama. 'That shows that muscular control has been re-established. We shall have him walking about in a day or so. Ah! he is dreaming, and of something pleasant, too. Look at his lips moving into a smile. Poor fellow, just fancy a man dreaming of things that happened three hundred years ago, and waking up to find himself in another world. I'll be bound he is dreaming about his wife or sweetheart, and we shall have to tell him, or rather you will, that she has been a mummy for three centuries. Look now, his lips are moving; I believe he is going to say something. See if you can hear what it is?'

The professor stooped down and held his ear so close that he could feel on his cheek the gentle fanning of the breath that had been still for three centuries. Then the Inca's lips moved again, and a soft sighing sound came from them, and in the midst of it he caught the words,—

'Cori-Coyllur, Nustallipa, Ñusta mi!'

Then there came a long, gentle sigh. The Inca's lips became still again, shaped into a very sweet and almost womanly smile, as though his vision had passed and left him in a happy, dreamless slumber.

'What did he say?' whispered Djama. 'Were you able to understand it?'

'Yes,' said the professor, 'yes, and you were right about the subject of his dream. Come away, in case we wake him, and I will tell you.'

They went to the other end of the laboratory, and the professor went on, still speaking in a low, half-whisper,—

'Poor fellow, I am afraid we have incurred a terribly heavy debt to him. What he said meant, "Golden Star, my princess, my darling!" So you see you were right, but poor Golden Star has been dead three hundred years and more —that is, at least, if his Golden Star is the same as the heroine of the tradition.'

'What tradition?' asked Djama.

'It's too long a story to tell you now, but if she is the same, then our Inca's name is Vilcaroya, and he is the hero of the strangest story, and, thanks to you, the strangest fate that the wildest romancer could imagine. However, the story must keep, for I wouldn't spoil it by cutting it short. The principal question now is—what are we going to do with him? We can't keep him here, of course?'

No, certainly not,' replied Djama, with knitted brows and faintly smiling lips. 'His Highness must be cared for in accordance with his rank and our expectations. I shall have him taken into the house and properly nursed.'

'But what about your sister? You will frighten her to death if you take in a living patient that has been dead for three hundred years.'

'Not if we manage it properly; there will be no need to tell Ruth the story yet, at anyrate. I'll tell her that I am going to receive a patient who is suffering from a mysterious disease unknown to medical science. I'll say I picked him up in the Oriental Home in Whitechapel, and have brought him here to study him, and you and I must smuggle him into the house and put him to bed some time when she is out of the way. Then I'll instal her as nurse; in fact, she will do that for herself; and as there is no chance of her learning anything from him, we can break the truth to her by degrees, and when His Highness is well enough to travel we'll all be off to Peru and come back millionaires, if you can only persuade him to tell you the secret of his treasure-houses.'

That night the doctor and the professor took turns in watching by the bedside of their strange patient, whose slumber became lighter and lighter until, towards midnight, he got so restless and apparently uneasy that Djama considered that the time had come to wake him and see if he was able to take any nourishment. So he set the professor to work, warming some chicken broth over a spirit lamp, and mixing a little champagne and soda-water in one glass and brandy and water in another. Meanwhile, he filled a hypodermic syringe with colourless fluid out of a little stoppered bottle, and then turned the sheet down and injected the contents of the syringe under the smooth, bronze skin of the Inca's shoulder. He moved slightly at the prick of the needle, then he drew two or three deep breaths, and suddenly sat up in bed and stared about him with wide open eyes, full, as they well might be, of inquiring wonder.

The professor, who had turned at the sound of the hurried breathing, saw him as he raised himself, and heard him say in the clear and somewhat high-pitched tone of a dweller among the mountains,—

'Has the morning dawned again for the Children of the Sun? Am I truly awake, or am I only dreaming that the death-sleep is over? Where is Golden Star, and where am I? Tell me—you who have doubtless brought me back to the life we forsook together—was it last night or how many nights or moons ago?'

"Am I only dreaming that the death-sleep is over?"

The words came slowly at first, like those of a man still on the borderland between sleep and waking; but each one was spoken more clearly and decisively than the one before it, and the last sentence was uttered in the strong, steady tones of a man in full possession of his faculties.

'Come here, Lamson,' said Djama, a trifle nervously; 'bring the soup with you, and some brandy, though I don't think he needs it. Do you understand what he said?'

'Yes,' replied the professor, coming to the bedside with a cup of soup in one hand and a glass of brandy and water in the other. Both hands trembled as he set the cup and the glass down on a little table. He looked at the Inca like a man looking at a re-embodied spirit, and said to him in Quichua,—

I am not he who has brought you back to life, but my friend here, who is a great and skilled physician, and master of the arts of life and death. You are in his house, and safe, for we are friends, and have nursed you back to health and waking life after your long sleep.'

'But Golden Star,' said the Inca, interrupting him with a flash of impatience in his eyes. Where is she—my bride who went with me into the shades of death? Have you not brought her, too, back to life?'

The professor stared in silence at the strange speaker of these strange words, which told him so plainly that the old legend of the death-bridal of Vilcaroya-Inca and Golden Star was now no legend at all, but a true story which had come down almost unchanged from generation to generation. Then an infinite pity filled his heart for this lonely wanderer from another age, whose friends and kindred had been dead for centuries, and whose very nation was now only a shadowy name on a half-forgotten page of history.

'What does he say?' said Djama, breaking in upon his reverie. 'I suppose he wants to know where he is, and what has become of that sweetheart of his he was dreaming about?'

'Yes,' replied the professor; 'but you won't understand properly until I have told you the story. Poor fellow! I suppose we shall have to tell him the ghastly truth. Good Heavens! fancy telling a man that his wife has been dead for three hundred years or more! Look here, Djama, this business can't stop here, you know. What a fool I was, after all, not to see if there wasn't another chamber beside the one I found him in! Of course there must be, and I have no doubt she is lying there at this present moment. We shall have to go and find her, and you must restore her as you have done him. Phew! where is it all going to end, I wonder!'

'And suppose we can't find her, or suppose I fail, even if I can bring myself to undertake that horrible work all over again?' said Djama, looking almost fearfully at the Inca, who was still sitting up in the bed glancing mutely from one to the other, as though waiting for an answer to his question. Then, keeping his voice as steady as he could, the professor told him the story of his resuscitation, addressing him by his own name and ending by asking him if he remembered when he and Golden Star had devoted themselves to die together, as the tradition said they had done.

'Yes, I remember!' said Vilcaroya, with brightening eyes and faintly flushing cheeks. 'How could I forget it? It was when the bearded strangers from the north had come and taken the usurper Atahuallpa prisoner in the midst of his conquering host at Cajamarca. It was after the Inca Huascar had been slain by stealth with a traitor's knife. It was on the night of the feast of Raymi, when our Father the Sun had left the Sacred Fleece unkindled, and when was fulfilled the prophecy that the night should fall over the land of the Children of the Sun. Now, tell me, you who speak the language of my people, how long have I been sleeping?'

Instead of replying directly, he offered the Inca the cup of broth, and asked him first to take the nourishment that he must need so greatly after his long fast, telling him that it was needful to prevent him losing his new-found strength again. When he had eaten and drunk a little, then he would tell him what he could.

He took the broth and a little bread obediently, and while he was eating and drinking, the professor translated what he had said to the doctor. When he had finished, Djama looked at the Inca, sitting there taking food and drink like any other human being, and with evident relish, too, and said,—

'That happened in 1532—three hundred and sixty-five years ago! It sounds utterly incredible, doesn't it, and yet there he is, eating and drinking and talking with us just like any other man. I can hardly believe the work of my own hands, and I am beginning to half wish I had never begun it. Just imagine the awful loneliness to which we shall have condemned this poor fellow, supposing we can't find his Golden Star and restore her to him! Still perhaps you had better tell him the truth at once. I think he can stand it. He has been a long time coming round, but I don't think there is much the matter with him now.

Then the professor told Vilcaroya theto him, so terrible truth, that of all men in the world he was the most lonely, separated as he was from all that he had known and loved by an impassable gulf of nearly four long centuries—that his well-loved Golden Star was but a memory known to few, a name in a vague tradition; that the resting-place, even of her mummy, was unknown, and that all that the darkest prophecy could have foretold had in very truth fallen upon the land of the Incas and the Children of the Sun.

Vilcaroya heard him to the end in silence; then, raising his hands to his forehead, he bowed his head and said,—

'It is the will of our Father, foretold by the lips of his priests, but other things were foretold which shall be fulfilled as well as these. Golden Star is not dead; she only sleeps as I did. If I have awakened, why shall not she? I know where she lies—where Anda-Huillac swore to me they would lay her. Come, let us go! I will take you to the place, and you shall restore her to me, warm and living and loving as she was when I kissed her good-bye in the Sanctuary of the Sun, and I will give you treasures of gold and silver and jewels such as you have never dreamed of in exchange for her.'

As the time passes between dreaming and waking, so for me did the long years pass, flowing like a smooth and silent stream seen from afar, out of the darkness that fell so slowly and so sweetly over my eyes that night when I sank into the death-trance beside Golden Star, my beloved, in the bridal chamber that they made for us in the Temple of the Sun, into the light that shone into them when they opened upon a scene so different, and saw a white, haggard face bending over me, and two black, burning eyes looking into them.

Then I closed them again and slept, and when I woke again there were two faces looking at me, both white and full of fear and wonder, and I saw two beings who seemed very strange to me, such as I had never seen among the Children of the Sun, standing by the couch on which I lay, and one of them fell down as though sore stricken, and I tried to think what this could mean, and, thinking, fell asleep again.

Then I dreamt a long, sweet dream of the days that I now know were far past, when I, Vilcaroya, son of the great Huayna-Capac, lived in the Land of the Four Regions, a prince among princes, a warrior and a child of the Sacred Race, whose blood had flowed unmixed through many generations from the divine fountain of life and light, our Father the Sun. I dreamt of Golden Star, and the days when I loved her in timid silence, for she was the fairest of all our race, and so, as it seemed to me, destined to no less a lot than the motherhood of a long line of Incas, in whom should live and grow to ever greater splendour the glories of the race that owned no earthly origin.

I called her in my dream, but she made no answer. I saw her lying by my side in that well-remembered chamber, with the shadowy forms of the priests standing about us as I had seen them long before; but, alas! she lay still with closed eyes and lips which seemed to have forgotten how sweetly they once could smile. I whispered her name, mingled with many a loving word, into her ear, and still she moved not. I put my arms about her and kissed her, and instantly I shrank back shivering with a fear unspeakable, for the form that should have been so warm and soft and yielding, was chilled and pulseless and rigid, as though some foul magic had changed it into stone, and the lips that should have given me back kiss for kiss were still and cold and senseless.

Then I saw, as it seemed with half-closed eyes, that dear shape of hers being borne away from me, while I, longing to snatch her from the hands of those who were robbing me of her, yet lay helpless on the couch, without strength to move or speak, until all grew dim around me, and I felt myself raised by invisible hands, and borne far away through the darkness— and so my dream melted away into the night of sleep.

Then, yet again, I woke and saw the two strange men that I had seen before, and one came and spoke to me kindly in my own tongue, and called me by my own name, and gave me food and drink, and told me in a few, but to me terrible, words that the dreams I had dreamed were dreams indeed— dreams of a time that was long gone by, of things that had passed away, perchance for ever, and men and women whose names were only memories.

Thus did I come from the evening of one age into the morning of another, falling asleep in the prime of my strength and manhood, and waking again even as I had fallen asleep—though those who had closed my eyes had been dead for many generations, and the name of our ancient race was but a bitter memory to the sons and daughters of my own land amidst the mountains.

Then I went forth into the wondrous new world into which I had awakened, the world which you who read this hold so common, and which I found crowded with wonders so many and marvellous that if it had not been for the loving care of her who guided my first footsteps on my new journey, as she might have guided those of a little child, my re-awakening reason must soon have been quenched in the night of madness.

Many and strange as were the things that happened to me during the first days and months of my awakening, there is little need that I should now write of them at any length. Yet something I must say of them in order that the still stranger things of which I shall have to tell may be the better understood.

And first I must tell of her whose gentle hand led me from weakness to strength, and guided my unwonted footsteps through the mazes of that new wonderland in which I had awakened, and from whose lips I learnt the first words that I spoke of the strong and stately English speech in which I am striving so lamely and imperfectly to write down the story of my new life.

This was Ruth, the sister of Djama, whose smile was the first ray of sunshine that shone into my second life, and whose laugh was so sweet and gladsome, that when it first sounded in my ears, like an echo from the dear dead past, I named her forthwith Cusi-Coyllur, which in English means Joyful Star—after that royal maiden of my own race who loved the handsome rebel Ollantay, and, refusing all others, waited for him in the House of the Virgins of the Sun until he came in triumph to claim her. She came with us to the south, rejecting all contrary counsel and braving the labours of the long, toilsome journey, so that she might be the first woman to welcome Golden Star back into the world of life.

Yet what words can I find in this new speech that I have yet but half learnt to tell fitly of her beauty and sweet graciousness, and of all the magic which made her seem in my eyes like an angel that had come down from the Mansions of the Sun to greet me in a world in which I was a stranger? Better that you who may read what I write should learn to know her for yourself through the sweetness and grace of her own words and deeds, as I shall strive, however unworthily, to tell of them. So, then, let it be.

But there is another of whom I must say something before I go on to tell of my return to my own land—now, alas! mine no longer—and that is Francis Hartness, a captain among the warriors of the English, and a friend of him who was called the professor, because of his learning— he who had helped Djama to bring me back into the world of living men.

He was a man of about thirty years, tall of stature and strong of limb, brief of speech and straight of tongue, with eyes as blue as the skies which shine on Yucay, and hair and beard golden and bright as the rays which flow from the smile of our Father the Sun. Him we met by chance one evening in the square of the town which is called Panama, named, they told me, after that older city, whence the conquerors of my people sailed to ravish the realms of Huayna-Capac. There was peace in his own land and all the neighbouring countries, and so he was journeying to the region which is now called South America, where the descendants of the Spaniards are nearly always fighting among themselves over the spoils of my people, to see what work he could find to keep his sword from rusting.

As he was greatly skilled in that strange, new warfare of flame and thunder and far-smiting bolts, which had but begun to be when our Father the Sun hid his face from the eyes of his children, I took counsel with Joyful Star—who was ever my wisest as well as my most faithful guide in all things—and we together told him my story as we went south, and after that I had asked him if he would help me in the task which I was going to essay, which was nothing less than the taking back of the land of my fathers, and the raising of the children of my people to the ancient glories of that state which I alone of living men remembered. To this, after some shrewd questioning, he consented—for it was a desperate venture, such as his brave heart loved—and when he had given me his hand on it, and promised, after the simple fashion of his nation, to be true to me in peace and war, I told him of the means that I could employ to gain my end, and how I would use that lust of gold which had led to the ruin of my people, so that it should conquer the children of their conquerors and give me back the empire that had been my father's.

At Panama we took ship again and travelled swiftly and straightly south, driven by that wondrous power which had come into the world to serve men like a tireless giant since I had fallen asleep; and day after day on the southward voyage I walked alone up and down the deck, or stood gazing, rapt in thought, at the desert foreshore along which the steamer was running, and at the great masses of the dark brown barren mountains, as they towered range beyond range till they overtopped the clouds themselves and stood serene and sharply outlined against the blue background of the upper sky.

Behind those mighty, rock-built ramparts lay the well-loved, well- remembered land over which my fathers had ruled in the days of peace, before the stranger and the oppressor had come. On the other side of them I knew that I was now fated to find only the poor fragments of the great cities and stately pleasure-houses that I had known in all their strength and beauty —only the silent and deserted ruins of the mighty fortresses which had guarded the confines of our lost empire, and were the portals through which the Children of the Sun had marched to unvarying conquest.

I thought, too, of the broad, green, level plain of Cajamarca, surrounded by its guardian ramparts of terraced hills; of the long, verdant valley of Cuzco with its hundred towns and villages nestling amidst the foliage which shaded their streets and squares, and looking out over the level fields of the valley and the countless tiers of terraces that rose green and gold with maize, or glowing with flowers, to the summits of the hills; and of that earthly paradise of Yucay, wherein the Gardens of the Sun, the golden shrines of my ancient faith, and the wondrous pleasure-palaces of many generations of Incas had glowed in almost heavenly beauty, embosomed in green and gold and scarlet in the midst of inaccessible mountains which themselves were overtopped by the mighty peaks of eternal snow that I had so often seen glimmering white and ghostly in the moonlight, like guardian spirits round an enchanted realm, on many a night of delicious revelry now far past and lost in the swift flood of the years that had rolled by since then.

It was to the poor remnants of all these glories that I was returning —returning to find, as they had told me, the homes of my ancestors laid waste and the descendants of my people the slaves of strangers. The desolation which it had taken centuries to accomplish would be to me but the swift, magical change of a day and a night and a morning.

Think, you who read, of the dread and the horror of it! I had seen the last day of the stately empire of my fathers the Incas! I had fallen asleep and I had awakened, and now, on the morrow of my sleep, I was coming back to the silent and ghastly ruins which the slow, pitiless work of the years and centuries had left behind it!

But over the gulf of these same centuries the hand of my Father the Sun was swiftly stretched out to help and uphold me, for no sooner did I again tread that soil which had once been sacred to Him, than my fainting heart grew strong with the memory of that ancient prophecy which I had come to fulfil, and of which this new life of mine was of itself a part fulfilment. If one part, and that not the least, had already been made good, then why not the rest?

Far away behind those towering tiers of mountains lay Golden Star in that resting-place to which she had been borne with me, sleeping soundly in the impassive embrace of their mighty arms; and within the safe-keeping of those arms lay, too, that uncounted treasure, that vast legacy which the long-dead leaders of my people had bequeathed to me for the sacred purpose of restoring those glories which all men, save myself, believed to be but a dream of the distant past, that incomparable inheritance of which I was the sole lawful heir on earth, and which I was coming to share with Golden Star when I had once more raised the Rainbow Banner above the restored throne of the divine Manco.

As I thought of all this, the blood that had lain stagnant through the long years of my magical death-sleep began to pulse like living fire through my veins. My new life with all its marvels became glorified into a waking vision of new conquests and re-won empire. The past was a dream both sweet and bitter in its vivid memories, but still a dream that had been dreamt and was done with. The present and the future were realities, golden and glorious with a hope justified by the miracle that had made them possible. I had learnt enough of the new age in which I had awakened to know that the lust of gold which had brought the conqueror and the oppressor into the land of the children of the Sun burnt every whit as fiercely in the hearts of the men who were living now as it had done in theirs, and that lust, as I had told Hartness and the others, should now work for me and for the redemption of my people so that that which had been their ruin should yet prove their salvation.

Thus, through the long sunny days and cool, starlit nights did I, Vilcaroya, last of the Incas, muse and dream until I once more stood in the Land of the Four Regions, hale and strong, and burning with the ardour of my sacred mission, ready to dare and do all things, and to use without ruth or scruple that dread power which would so soon lie within my hands to fulfil my oath and Golden Star's, and to accomplish the work that I had come through the shadows of death to do.

So I came back to the shores of that well-loved land of mine which, by the reckoning of the new time into which I had come, had been for more than three hundred years the sport and prey of the generations of strangers and oppressors who had followed those first conquerors of the Children of the Sun, whose coming had sounded the hour of doom and ruin through the length and breadth of that glorious land of green plains and verdant valleys, of terraced hills and towering mountains, which had once been our empire and our home.

From the mean coast town of wooden houses where the railway begins we travelled ever upward over great, grey, sloping deserts, and by rugged ravines with steep, broken walls of red earth and ragged rock; through range after range of mountains that were all strange and hateful to me, until we swung round the shoulder of a great crag-crowned mountain, and I saw across a vast plain, into which range after range of lesser hills sloped down, the crystal- white peaks of the snow-mountains towering far beyond the clouds into the blue sky above them.

Then I knew that I was coming nearer to the land that had once been mine, and ere many hours had passed we stopped in a great city which still bore its old name of Arequipa, the Place of Rest, which my own ancestors had given to it. It was no longer the place of palaces and pleasure-houses, of flowery gardens and leafy woods that I had seen it, but above it still gleamed the white snow-fields and shining peaks of Charchani and Pichu-Pichu, and between the two great white ranges still towered the vast, black, snow-crowned cone of Misti, the smoke-mountain, rising sheer in its lonely grandeur twelve thousand feet above the sloping plain on which the city lay.

As I looked at it again for the first time after so many years, I asked the professor, as we all called him, if, since I had been asleep, the mountain had been rent asunder again as it had been in the olden times, long before the Spaniards came to seek gold and blood in the Land of the Four Regions. He was very learned in such matters, even as Djama, his friend, was learned in secrets of life and death, and when he told me that the fires within it had slept for more years than men could remember, I was glad. Yet I said nothing of my inward joy, for had I told them all that I knew about the valley of black sand and yellow rock that was hidden behind the far-off wall of snow which shone so whitely against the blue of the midway heaven, it might have been many a long day before we had again set out on our journey towards the place that was the goal at once of my hopes and fears.

We stayed seven days in Arequipa, making our last preparations for the work that lay before us and then we went on again by train to Sicuani, in the valley of the Vilcariota. Then from Sicuani we journeyed on by road, riding on mules through a land that was lovely even in my eyes, though its loveliness was to me only the beauty of ruin and decay, for this was the heart and centre of that vanished empire whose glories no living eyes but mine had ever seen.

I saw wildernesses where there had been gardens, and gaunt, treeless mountains lying bare to the glare of the sun. Lakes that had shone encircled with gardens now spread out dull and stagnant over the neglected fields. A few ragged fragments of grey clay walls still rose from the green plain of Cacha, where I had last seen, in all its glory of gold and rainbow colours, the holy Temple of Viracocha; and the great guardian fortress of Piquillacta, which I had seen stretching its impregnable length and rearing its unscalable height from mountain to mountain across the entrance to the once lovely valley of Cuzco, lay, a huge ragged mass of towering ruins, splendid even in decay.

As we passed through the one half-choked portal that still lay open, I thought, with heavy heart and bowed-down head, of the great fortress as I had seen it in the glory of its pride and strength, of the gallant warriors that had defended it, and the gay processions that I had seen winding in and out of its stately gates, making its hoary walls ring with songs and laughter, and, farther on, as we rode along the valley on that sad and yet eager three days' march of ours, I saw, on the hill-spurs about me, the black and ragged ruins of the fair cities and stately temples and palaces that I had seen crowded with happy throngs, bright with gold and colours, and so fair and strong that no man could have dreamed of the ruin the oppressor had brought upon them.

And so, journeying amidst all these sad memories through a land which, for me, was peopled with the ghosts of my long-dead friends and kindred, we came out at length on the broad, green Plain of the Oracle, and there before me, still nestling under her guardian hills, lay, glimmering white and grey under the slanting sun-rays, all that was left of what had once been Cuzco, the City of the Sun and the home of his children. Then, as I lifted my eyes and gazed upon it through the rising mist of my tears, I bowed my bared head towards it and swore, in the sadness and silence of my desolate heart, that, to the full extent of the power which I believed was soon to be mine, I would take life for life and blood for blood, and I would give sorrow for sorrow and shame for shame, until I had paid to the full the debt which the long years of plunder and cruelty and oppression had heaped up against those who, from generation to generation, had brought this shame and ruin on the once bright home of the Children of the Sun.

I shall not weary you who perchance may some day read this story of mine by dwelling on the sorrow and shame that filled me as I entered the foul, unlovely streets, and saw the filthy refuse in the squares of the city that I remembered so pure and bright and beautiful; nor yet by telling of the feelings that possessed me when I saw the poor remains of our desecrated temples, the places where our vanished palaces had stood, and the dismantled ruins of that mighty fortress of Sacsahuaman, which I had last seen standing palace-crowned and throned in all its grandeur high up above the city.

All this and more you who read must picture for yourselves, for I have greater things to tell of than the poor sorrows of a wanderer who had left his own age and his own kindred far behind him, and who had come back into a strange world to find his country a wilderness, and the children of his people the slaves of strangers.

It had been settled amongst us that, for the purpose for which we had come, it would be necessary to hire a house that should be at once commodious for our work, sufficiently removed from the city for privacy, and capable of defence against intruders if need be. The professor, being already known in Cuzco as a man of science and seeker after antiquities, and possessing, moreover, a special permit from the Government in Lima to travel and dwell in the interior, and make such searches as he thought fit, undertook the business of finding such a house. He made many journeys in quest of what he sought, and on these journeys Djama always accompanied him, since he had to see that the house chosen contained a chamber suitable for that precious work which he had undertaken to do in return for the share of treasure that I was to give to him.

And while these two were absent I at times wandered about the city with Joyful Star and Francis Hartness, who, it was plain to see, already looked with eyes of love and longing on her beauty, as in good truth I myself could have done had I dared, and could I have forgotten that older love of mine who still lay cold in her death-sleep in the cave by the lake yonder, over the mountains to the westward, whither I had already cast so many longing glances. But at other times I left them to go upon my own ways, for I had work on hand which, for the present, did not concern them.

I had by this time met and conversed with many of my people in their own language, which was that of the labouring classes of my own times, and from them I had learned that at a village called San Sebastian, through which we had passed, about two leagues to the south of the city, there still dwelt many families of Ayllos—that is to say, the descendants of those of the old noble Inca lineage, who had been permitted by their conquerors to settle here. So one morning I went to visit an old Indian—as they now called all our people—named Ullullo, with whom I had made acquaintance, and at his house I dressed myself in the native fashion— in an old shirt and short trousers, with sandals on my feet, and a broad-brimmed, fringed hat on my head, and covered myself with a faded poncho, and together we went on foot to San Sebastian, I looking no different from the rest of the Indians who were passing to and fro upon the road.

I had already seen, while riding through the village, that the people were different to those of all other villages that we had come through on the way. They were taller of stature, prouder of carriage, and fairer of face. The blood showed red in their cheeks through the light brown of their skin, and these signs had told me that if any remnant of the pure Inca race was left these must be they; and I was soon to have proof that it was so, although the children of those who had lived in palaces were now dwelling in huts of mud and reeds.

Ullullo led me first to the house of a man named Tupac Rayca, who was chief among the Indians of the town. He was great-grandson of that ill-fated Tupac-Amaru, who, as you know, had revolted many years before against the oppressors of his race, and for this, after being forced to watch the torture and murder of his wife in the square of Cuzco, had himself been torn limb from limb by horses.

We found him alone in a bare room in one of the better houses of the village. As he stood up to salute us it needed but a glance to tell me that in his veins at least the ancient blood of our race flowed well nigh as purely as it did in my own. Had it not been for the meanness of his clothing and the dull, brooding look on his noble features—the stamp of generations of oppression—I could have pictured him with the yellow Llautu* on his brow, the golden image of the Sun on his girdled tunic, and the rainbow banner in his hand, standing amongst the guards of the great Huayna-Capac himself.

* The yellow Llautu, or fringed turban of wool, worn on the brows, was the distinguishing mark of the sacred Inca race. The scarlet was worn only by the reigning Inca—'Son of the Sun.' Its fringe, called the 'borla,' was mingled with threads of gold.

I asked Ullullo to leave us alone for a little while, and when he had gone I stepped forward, and, drawing myself up to my full height, I looked him in the eyes, and said in the tongue that was spoken only by those of the divine Inca race,—

'Tell me, Tupac-Rayca, does a remnant of the Children of the Sun still dwell in the Land of the Four Regions, and are they still faithful to the traditions of their race, and the faith of their ancestors?'

As the words left my lips he staggered back a pace or two with his hands clasped to his forehead, staring at me from under them as though—as in very truth I was—some spirit of the past stood re-embodied before him. Then, coming forward again and scanning me eagerly from head to foot, he whispered in the same tongue—by the Lord of Light how those familiar accents thrilled my ears as I heard them again after so long!

'Who are you—a stranger—that comes in the image of those long dead, to ask me such a question in the tongue that may only be spoken when none save those of the Blood are present?'

'One who is of the Blood himself!' I answered, taking a stride towards him, and stretching out my hand. 'Fear not, Tupac-Rayca, son of him that suffered, I am a friend, and have come from afar to work as a friend with you and others of the Blood that may still be left in the land, with a great and holy purpose of which you shall know ere long.'

He grasped my hand and bowed over it in silence for a while. Then he stepped back and looked at me again, murmuring,—

'Can it be so? Has the divine Manco come back from the Mansions of the Sun to save the remnant of his children, or has Vilcaroya broken the bonds of his death-sleep and come to fulfil the oath he swore with Golden Star before the altar in the Sanctuary? I know all the Children of the Blood that are left in the land, and I have never seen your face before, yet you are of the Blood. Who are you—Lord?'

The last word seemed forced from his lips by some power other than his own will, and it sounded most pleasant to me, for it told me that, without knowing my name, and seeing me only as a stranger, he had recognised the stamp of my divine ancestry, and this promised well for the progress of the work I had in hand. I answered him kindly, and yet as one speaking to another who is scarce his equal, and said,—

My name matters not now or here, Tupac, for we are but two, and I might lie to you, and you would have no proof of my truth or falsehood. But if you will do as I bid you, to-night you shall know and all shall be made plain and with ample proof. Are you willing to give me your aid?'

He picked up a rude hoe that stood in a corner of the room, and laying it across his shoulder after the manner of one who bears a burden, bowed his head and answered,—

'The Son of the Sun has but to speak, and I and all his slaves will obey.'

What he had done was an act of homage, which, in the olden time, was paid only to him who wore the imperial Llautu, and proved to me how faithfully the old traditions had been preserved in secret.

'That is well said, Tupac,' I replied, speaking now as a sovereign might speak to a faithful subject, 'and in the days to come fear not that I shall forget this, your first act of unasked-for homage. Now, hear me. Are there twenty men of the Blood in this village—men who are faithful and can be trusted even to the death?'

'There are five hundred here, Lord, and as many thousands within the valley, whose blood has flowed pure from the olden times, unpolluted by a single stain of Spanish dirt. What would you with them?'

I asked not for hundreds or thousands,' I said, right glad at heart to hear such good tidings. 'For the present I need but a score, so do you choose me twenty of the noblest blood and the best judgment, and an hour before midnight let them be with you on the plain behind the Sacsahuaman. Let them come well provided with torches or candles, and tools, levers, and hammers and spades. Tell them what has passed between us, but nothing of the guesses that you may have made in your own mind while we have been talking, and leave the rest to me. Can you do that?'

It shall be done, Lord,' he answered, still bending before me with the shaft of the hoe across his shoulders, 'and we will wait and toil in patience till the Son of the Sun shall please to reveal himself to the eyes of his servants.'

Nor shall you have to wait long,' I said. 'Now put that off your back and take my hand again, for we are not Inca and servant yet, only two men of the Blood, and brothers of a fallen race who are joined together to perform a holy work. Now farewell, Tupac, till to-night. Choose your companions well, and fear not but that your services and your faithfulness shall have their due reward.'

He put his hand humbly and tremblingly into mine, bowing low over it, and so I left him, standing there with bent head, not daring to look up until the door closed behind me. Then Ullullo and I went back into the city, and as we crossed the great square on our way to Ullullo's house, I saw my four English friends standing among the market people by the fountain in the centre. We passed close to them, and I heard my name spoken by Joyful Star to her brother, who answered her and said,—

'I daresay we shall find he is making friends again with some of these filthy Indian compatriots of his.'

I hated him from that moment for his bitter words, and swore in my heart that some day he should pay for them, for I loved my people, and pitied them in their misery and degradation. I stopped beside them, and my heart was beating hard as I listened for what Joyful Star would say, and I have remembered her words, even as I have remembered his. She looked at him with the light of anger in her eyes and said,—

'For shame, Laurens! I couldn't have believed that you would have said such a thing. If you belonged to a race that had been enslaved and plundered by these brutes of Spaniards and Peruvians for three centuries and a half, do you think you would be any better than these poor fellows? And, besides, whatever they are, they are Vilcaroya's people, and he is our friend.'

I could have fallen on the stones and kissed her feet for those sweet words of hers, and I moved away quickly for fear I should betray myself, and went with a swelling heart and mingled tears of love and anger in my eyes to old Ullullo's house, where I changed my clothes again, and then, as it was nearly dinner time, which, as you know, is in the evening in Spanish countries, I went back to the house where we were lodging, wondering what they would think if they could have understood the words that had passed between Tupac-Rayca and myself.

When I met them again I saw that they would willingly have learned what had become of me during the day, but I answered their inquiries by telling them nothing more and yet a great deal less than the truth, and saying that I had spent the day revisiting old scenes, and learning what I could of the present condition of my people. This satisfied them outwardly at least, though I saw a look in Djama's eyes which told me that he suspected more of the truth than it suited my purpose to tell him.

Then our conversation turned to the matter of procuring a house, such as I have spoken of, and the professor told me that he had heard of a hacienda, well built and solid, and standing in its own domain, about three leagues across the valley to the westward, on a secluded little plain among the hills, which would serve our purpose excellently; but the owner of it wished to sell it, and 'with the stupidity of these Peruvians,' as he said, would not hire it out to us but would only sell it, and the price was twenty thousand soles, or dollars of Peru, which was two thousand pounds in English money.

It is a great pity,' said the professor, when he had finished telling me about it, 'for it doesn't seem as though there was another house in the neighbourhood of Cuzco that would suit our purpose, and this one would do perfectly.'

'Of course, if the fellow won't let it there's no use thinking any more about the matter, for two thousand pounds is entirely out of the question. It seems to me that the expedition will be quite expensive enough without the luxury of buying houses at fancy prices.'

It was Djama who spoke. No one else at our table could have spoken like that. I heard him in silence, for I could not trust myself to speak for the anger that was rising within me. I saw Joyful Star raise her eyelids and look at him with a swift glance that meant much; but she, too, said nothing; and then, looking at me, he spoke again and said,—

'Of course, if His Highness'—for so he always spoke of me when no strangers were present—'would just unlock one of those treasure-houses of his, the matter would be easy enough, but I suppose that's outside the contract.'

I still kept silence, knowing as I did what the night was to bring forth. But Francis Hartness answered for me, and said,—

'I don't think you can quite put it that way, Djama, if you'll excuse me saying so. If I am not mistaken, it has been clearly understood that the first treasure-house to be unlocked is the one that holds Vilcaroya's greatest treasure—his wife—and what you say seems to suggest —'

'It is enough!' I said, unconsciously speaking in my growing anger in the same imperious tone that I had used but a few hours before to Tupac. 'Let the house be bought. I will charge myself with the cost, and I will be the debtor of my friends no longer.'

They stared at me as I spoke, for hitherto I had spoken to them as a child rather than as a man; as an inferior, rather than as an equal. I saw a smile that was not pleasant to look upon pass swiftly over Djama's mouth, but he kept silence, and the professor said to me,—

'Are you really in earnest, Vilcaroya? You know, according to our bargain, we have no claim on you until our part of the work is done. None of us have any desire to learn your secrets.'

I am not talking of secrets,' I said, breaking into his speech, 'and one of my race does not speak to make a liar of himself. What I say I can do and will, for I wish the work to begin at once. Do you think I have not waited long enough for my beloved, my sister and my wife?'

'Your what!' cried Joyful Star, rising suddenly from her seat, and staring at me with fixed and wide-opened eyes. 'Your sister! Oh, Vilcaroya, surely this is not true!' and as she said this I saw her cheeks grow pale and her lips tremble.

'Yes,' I answered, 'it is true. Why should I lie to my new sister and friend, Joyful Star? Golden Star was the daughter of my father, the great Huayna-Capac, though our mothers were not the same.'

I had no time to finish my speech, for with a look of unutterable horror in her eyes, which pierced me to the heart and seemed to sever it in twain, she cried,—

'Oh, no, no! that is too horrible! I don't want to hear any more. I will go back to England to-morrow. Laurens, come to my room; I want to speak to you at once.'

So saying, she went to the door and opened it and went out, followed by her brother, who looked at me as he passed me with a look which I never forgot or forgave, for it was like the words that I had heard him say to her in the square.

'What is this?' I said to the professor when the door had closed behind them. 'What have I said or done that Joyful Star should look with horror upon me and say such cruel words?'

I saw him exchange glances full of meaning with the English soldier before he answered me; and then, leaning his arms on the table in front of him, he said, in that quiet, calm voice of his,—

'My dear Vilcaroya, it is a very strange thing, and, as far as Miss Djama is concerned, perhaps, a very great pity that this has never come out before, for without knowing it you have given her a shock that may have very painful consequences. No, don't interrupt me now, for the sooner I can make you understand the meaning of your words to her the better. It is this way: we know, of course, that in your day and among your people sister-marriage was held to be the most sacred of all marriages. We know that from such a marriage only might spring the wearer of the imperial Borla, but to us the idea is so unutterably horrible and revolting that of all the crimes that could be committed by one of our race that would be the most fearful. It cannot even be discussed amongst us, and yet you, in the most perfect innocence, have spoken of it in the presence—Good Heavens, Hartness! what is to be done? Do you think Miss Djama was really in earnest when she talked of going back to England to-morrow? It is impossible—it would ruin everything!'

I kept silence, for my sorrow and wonder were too great for words, but I listened eagerly for what Francis Hartness would say in reply.

'She was in earnest when she spoke,' he said, as quietly as the professor had spoken; 'but, if the doctor has as much sense as I give him credit for, she will have seen the thing in a different light by this time. Of course, she has read Prescott, and she really knows as much about the marriage customs of the ancient Incas as we do. In fact, to tell you the truth' —and as he said this I saw him frown, and an angry light came into his eyes that I had never seen in them before—'I really can hardly understand how, knowing that as she does know it, she can have been as horrified as she certainly was. She knows perfectly well that Vilcaroya has come at a single step, as it were, from his age into ours, and so must have brought all the ideas and beliefs of his time and his people with him. Depend upon it, a little reflection will very soon show her that, horrible and all as the idea must naturally have appeared to her at the first shock of hearing it, from Vilcaroya's point of view there is nothing in it but what is perfectly natural and proper. Now, to my mind, the matter is much more sad and serious for Vilcaroya himself than for anyone else.'

As he said this he turned from the professor to me and went on, addressing me in a tone so frank and kindly that ever afterwards I looked upon him as my friend and my brother,—

'It's not a pleasant thing for me to say, and it must, of course, be a very painful one for you to hear; still, it has got to be said some time or other, and, unless I am wrong in what I think of you, I believe you are man enough to hear it and to agree with me that it had better be said now than later on, when the saying of it might be tenfold more painful both to you and us.'

'Say on,' I said shortly. 'Your tongue is straight and your eyes look into mine as those of a friend should look. I am listening.'

'I would wish for no better friend than you, Vilcaroya, after that, for I know what you mean. Now, what I have to say is this. We know, of course, that you look upon yourself as doubly married to this love of yours, who is dead and, like you, may yet be alive again. You are bound to her, not only by a marriage which, in the time that it took place, was perfectly lawful and natural, but also by the oath that you took together. But you have come back to the world in another age and among another people, and now that form of marriage is looked upon by all civilised humanity, not only as unlawful, but, as the professor has just said, unnatural and horrible beyond conception.

'Therefore, if Golden Star is restored to life, for you to love her, save as a brother, or for you to consummate the union which, as you have told us, began and ended before the altar of the Sun, would be to make not only yourself, but your—your sister, Golden Star, as well, looked upon with horror and loathing by every civilised man and woman who knew your story. I am speaking strongly, because it is necessary.