RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

FOR their honeymoon Rollo Lenox Smeaton Aubrey, Earl of Redgrave, and his bride, Lilla Zaidie, leave the Earth on a visit to the Moon and the principal planets, their sole companion being Andrew Murgatroyd, an old engineer who had superintended the building of the Astronef, in which the journey is made. By means of the "R. Force," or Anti-Gravitational Force, of the secret of which Lord Redgrave is the sole possessor, they are able to navigate with precision and safety the limitless ocean of space. Their adventures on the Moon and on Mars have been described in the first two stories of the series.

"HOW very different Venus looks now to what it does from the earth," said Zaidie as she took her eye away from the telescope, through which she had been examining the enormous crescent, almost approaching to what would be called upon earth a half-moon, which spanned the dark vault of space ahead of the Astronef.

"I wonder what she'll be like. All the authorities are agreed that on Venus, having her axis of revolution very much inclined to the plane of her orbit, the seasons are so severe that for half the year its temperate zone and its tropics have a summer about twice as hot as our tropics and the other half they have a winter twice as cold as our coldest. I'm afraid, after all, we shall find the Love-Star a world of salamanders and seals; things that can live in a furnace and bask on an iceberg; and when we get back home it will be our painful duty, as the first explorers of the fields of space, to dispel another dearly-cherished popular delusion."

"I'm not so very sure about that," said Lenox, glancing from the rapidly growing crescent, which was still so far away, to the sweet smiling face that was so near to his. "Don't you see something very different there to what we saw either on the Moon or Mars? Now just go back to your telescope and let us take an observation."

"Well," said Zaidie, "as our trip is partly, at least, in the interest of science, I will." and then, when she had got her own telescope into focus again—for the distance between the Astronef and the new world they were about to visit was rapidly lessening—she took a long look through it, and said:

"Yes, I think I see what you mean. The outer edge of the crescent is bright, but it gets greyer and dimmer towards the inside of the curve. Of course Venus has an atmosphere. So had Mars; but this must be very dense. There's a sort of halo all round it. Just fancy that splendid thing being the little black spot we saw going across the face of the Sun a few days ago! It makes one feel rather small, doesn't it?"

"That is one of the things which a woman says when she doesn't want to be answered; but, apart from that, your ladyship was saying?"

"What a very unpleasant person you can be when you like! I was going to say that on the Moon we saw nothing but black and white, light and darkness. There was no atmosphere, except in those awful places I don't want to think about. Then, as we got near Mars, we saw a pinky atmosphere, but not very dense; but this, you see, is a sort of pearl-grey white shading from silver to black. But look—what are those tiny bright spots? There are hundreds of them."

"Do you remember, as we were leaving the earth, how bright the mountain ranges looked; how plainly we could see the Rockies and the Andes?"

"Oh, yes, I see; they're mountains; thirty-seven miles high some of them, they say; and the rest of the silver-grey will be clouds, I suppose. Fancy living under clouds like those."

"Only another case of the adaptation of life to natural conditions, I expect. When we get there, I daresay we shall find that these clouds are just what make it possible for the inhabitants of Venus to stand the extremes of heat and cold. Given elevations, three or four times as high as the Himalayas, it would be quite possible for them to choose their temperature by shifting their altitude.

"But I think it's about time to drop theory and see to the practice," he continued, getting up from his chair and going to the signal board in the conning-tower. "Whatever the planet Venus may be like, we don't want to charge it at the rate of sixty miles a second. That's about the speed now, considering how fast she's travelling towards us."

"And considering that, whether it is a nice world or not, it's about as big as the earth, and so we should get rather the worst of the charge," laughed Zaidie, as she went back to her telescope.

Redgrave sent a signal down to Murgatroyd to reverse engines, as it were, or, in other words, to direct the "R. Force" against the planet, from which they were now only a couple of hundred thousand miles distant. The next moment the sun and stars seemed to halt in their courses. The great silver-grey crescent which had been increasing in size every moment appeared to remain stationary, and then when Lenox was satisfied that the engines were developing the force properly, he sent another signal down, and the Astronef began to descend.

The half-disc of Venus seemed to fall below them, and in a few minutes they could see it from the upper deck spreading out like a huge semi-circular plain of silver grey light ahead, and on both sides, of them. The Astronef was falling upon it at the rate of about a thousand miles a minute towards the centre of the half crescent, and every moment the brilliant spots above the cloud-surface grew in size and brightness.

"I believe the theory about the enormous height of the mountains of Venus must be correct after all," said Redgrave, tearing himself with an evident wrench away from his telescope. "Those white patches can't be anything else but the summits of snow-capped mountains. You know how brilliantly white a snow-peak looks on earth against even the whitest of clouds."

"Oh, yes," said her ladyship, "I've often seen that in the Rockies. But it's lunch time, and I must go down and see how my things in the kitchen are getting on. I suppose you'll try and land somewhere where it's morning, so that we can have a good day before us. Really it's very convenient to be able to make your own morning or night as you like, isn't it? I hope it wont make us too conceited when we get back, being able to choose our mornings and our evenings; in fact, our sunrises and sunsets on any world we like to visit in a casual way like this."

"Well," laughed Redgrave, as she moved away towards the companion stairs, "after all, if you find the United States, or even the planet Terra, too small for you, we've always got the fields of Space open to us. We might take a trip across the Zodiac or down the Milky Way."

"And meanwhile," she replied, stopping at the top of the stairs and looking round, "I'll go down and get lunch. You and I may be king and queen of the realms of Space, and all that sort of thing; but we've got to eat and drink after all."

"And that reminds me," said Redgrave, getting up and following her, "we must celebrate our arrival on a new world as usual. I'll go down and get out the champagne. I shouldn't be surprised if we found the people of the Love-World living on nectar and ambrosia, and as fizz is our nearest approach to nectar-—"

"I suppose," said Zaidie, as she gathered up her skirts and stepped daintily down the companion stairs, "if you find anything human or at least human enough to eat and drink, you'll have a party and give them champagne. I wonder what those wretches on Mars would have thought of it if we'd only made friends with them?"

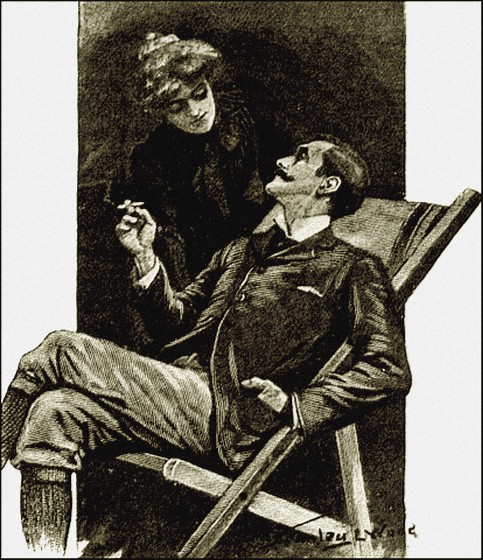

Lunch on board the Astronef was about the pleasantest meal of the day. Of course there was neither day nor night, in the ordinary sense of the word, except as the hours were measured off by the chronometers. Whichever side or end of the vessel received the direct rays of the sun, there then was blazing heat and dazzling light. Elsewhere there was black darkness, and the more than icy cold of space; but lunch was a convenient division of the waking hours, which began with a stroll on the upper deck and a view of the ever-varying splendours about them and ended after dinner in the same place with coffee and cigarettes and speculations as to the next day's happenings.

This lunch hour passed even more pleasantly and rapidly than others had done, for the discussion as to the possibilities of Venus was continued in a quite delightful mixture of scientific disquisition and that converse which is common to most human beings on their honeymoon.

As there was nothing more to be done or seen for an hour or two, the afternoon was spent in a pleasant siesta in the luxurious saloon of the star-navigator; because evening to them would be morning on that portion of Venus to which they were directing their course, and, as Zaidie said, when she subsided into her hammock: "It will be breakfast time before we shall be able to get dinner."

As the Astronef fell with ever-increasing velocity towards the cloud-covered surface of Venus, the remainder of her disc, lit up by the radiance of her sister-worlds, Mercury, Mars, and the Earth, and also by the pale radiance of an enormous comet, which had suddenly shot into view from behind its southern limb, became more or less visible.

Towards six o'clock, according to Earth, or rather Astronef, time, it became necessary to exert the full strength of her engines to check the velocity of her fall. By eight she had entered the atmosphere of Venus, and was dropping slowly towards a vast sea of sunlit cloud, out of which, on all sides, towered thousands of snow-clad peaks, with wide-spread stretches of upland above which the clouds swept and surged like the silent billows of some vast ocean in ghost-land.

"I thought so!" said Redgrave, when the propellers had begun to revolve and Murgatroyd had taken his place in the conning-tower. "A very dense atmosphere loaded with clouds. There's the sun just rising, so your ladyship's wishes are duly obeyed."

"And doesn't it seem nice and homelike to see him rising through an atmosphere above the clouds again? It doesn't look a bit like the same sort of dear old sun just blazing like a red-hot moon among a lot of white hot stars and planets. Look, aren't those peaks lovely, and that cloud-sea? Why, for all the world we might be in a balloon above the Rockies or the Alps, And see," she continued, pointing to one of the thermometers fixed outside the glass dome which covered the upper deck, "it's only sixty-five even here. I wonder if we could breathe this air, and oh, I do wonder what we shall see on the other side of those clouds."

"You shall have both questions answered in a few minutes," replied Redgrave, going towards the conning-tower. "To begin with, I think we'll land on that big snow-dome yonder, and do a little exploring. Where there are snow and clouds there is moisture, and where there is moisture a man ought to be able to breathe."

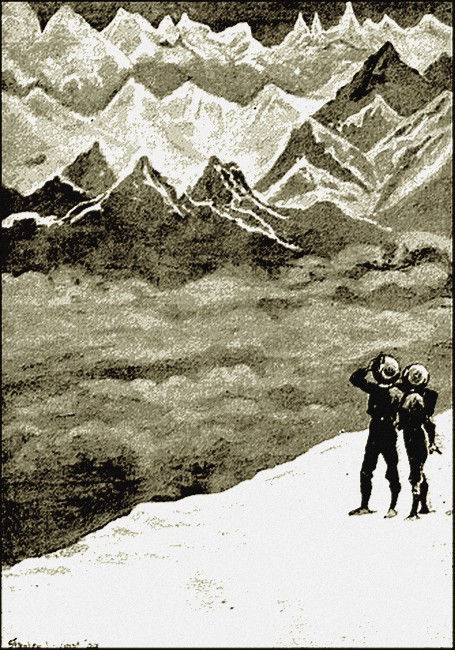

The Astronef, still falling, but now easily under the command of the helmsman, shot forwards and downwards towards a vast dome of snow which, rising some two thousand feet above the cloud-sea, shone with dazzling brilliance in the light of the rising sun. She landed just above the edge of the clouds. Meanwhile they had put on their breathing suits, and Redgrave had seen that the air chamber, through which they had to pass from their own little world into the new ones that they visited, was in working order. When the outer door was opened and the ladder lowered he stood aside, as he had done on the moon, and her ladyship's was the first human foot which made an imprint on the virgin snows of Venus.

The first thing Lenox did was to raise the visor of his helmet and taste the air of the new world. It was cool, and fresh, and sweet, and the first draught of it sent the blood tingling and dancing through his veins. Perfect as the arrangements of the Astronef were in this respect, the air of Venus tasted like clear running spring water would have done to a man who had been drinking filtered water for several days. He threw the visor right up and motioned to Zaidie to do the same. She obeyed, and, after drawing a long breath, she said:

Lenox raised the visor of his helmet...

"That's glorious! It's like wine after water, and rather stagnant water too. But what a world, snow-peaks and cloud-sea, islands of ice and snow in an ocean of mist! Just look at them! Did you ever see anything so lovely and unearthly in your life? I wonder how high this mountain is, and what there is on the other side of the clouds. Isn't the air delicious! Not a bit too cold after all—but, still, I think we may as well go back and put on something more becoming. I shouldn't quite like the ladies of Venus to see me dressed like a diver."

"Come along then," laughed Lenox, as he turned back towards the vessel. "That's just like a woman. You're about a hundred and fifty million miles away from Broadway or Regent Street. You are standing on the top of a snow mountain above the clouds of Venus, and the moment that you find the air is fit to breathe you begin thinking about dress. How do you know that the inhabitants of Venus, if there are any, dress at all?"

"What nonsense! Of course they do—at least, if they are anything like us."

As soon as they got back on board the Astronef and had taken their breathing-dresses off, Redgrave and the old engineer, who appeared to take no visible interest in their new surroundings, threw open all the sliding doors on the upper and lower decks so that the vessel might be thoroughly ventilated by the fresh sweet air. Then a gentle repulsion was applied to the huge snow mass on which the Astronef rested. She rose a couple of hundred feet, her propellers began to whirl round, and Redgrave steered her out towards the centre of the vast cloud-sea which was almost surrounded by a thousand glittering peaks of ice and domes of snow.

"I think we may as well put off dinner, or breakfast as it will he now, until we see what the world below is like," he said to Zaidie, who was standing beside him on the conning-tower.

"Oh, never mind about eating just now; this is altogether too wonderful to be missed for the sake of ordinary meat and drink. Let's go down and see what there is on the other side."

He sent a message down the speaking tube to Murgatroyd, who was below among his beloved engines, and the next moment sun and clouds and ice-peaks had disappeared and nothing was visible save the all-enveloping silver-grey mist.

For several minutes they remained silent, watching and wondering what they would find beneath the veil which hid the surface of Venus from their view. Then the mist thinned out and broke up into patches which drifted past them as they descended on their downward slanting course.

Below them they saw vast, ghostly shapes of mountains and valleys, lakes and rivers, continents, islands, and seas. Every moment these became more and more distinct, and soon they were in full view of the most marvellous landscape that human eyes had ever beheld.

The distances were tremendous. Mountains, compared with which the Alps or even the Andes would have seemed mere hillocks, towered up out of the vast depths beneath them. Up to the lower edge of the all-covering cloud-sea they were clad with a golden-yellow vegetation, fields and forests, open, smiling valleys, and deep, dark ravines through which a thousand torrents thundered down from the eternal snows beyond, to spread themselves out in rivers and lakes in the valleys and plains which lay many thousands of feet below.

"What a lovely world!" said Zaidie, as she at last found her voice after what was almost a stupor of speechless wonder and admiration. "And the light! Did you ever see anything like it? It's neither moonlight nor sunlight. See, there are no shadows down there; it's just all lovely silvery twilight. Lenox, if Venus is as nice as she looks from here I don't think I shall want to go back. It reminds me of Tennyson's Lotus Eaters, 'The land where it is always afternoon.'"

"I think you are right after all. We are thirty million miles nearer to the sun than we were on the earth, and the light and heat have to filter through those clouds. They are not at all like earth-clouds from this side. It's the other way about. The silver lining is on this side. Look, there isn't a black or a brown one, or even a grey one within sight. They are just like a thin mist, lighted by millions of electric lamps. It's a delicious world, and if it isn't inhabited by angels it ought to be."

While they were talking, the Astronef was still sweeping swiftly down towards the surface through scenery of whose almost inconceivable magnificence no human words could convey any adequate idea. Underneath the cloud-veil the air was absolutely clear and transparent; clearer, indeed, than terrestrial air at the highest elevations, and, moreover, it seemed to be endowed with a strange luminous quality, which made objects, no matter how distant, stand out with almost startling distinctness.

The rivers and lakes and seas, which spread out beneath them, seemed never to have been ruffled by the blast of a storm or wind, and shone with a soft silvery grey light, which seemed to come from below rather than from above. The atmosphere, which had now penetrated to every part of the Astronef, was not only exquisitely soft but also conveyed a faint but delicious sense of languorous intoxication to the nerves.

"If this isn't Heaven it must be the half-way house," said Redgrave, with what was, perhaps, under the circumstances, a pardonable irreverence. "Still, after all, we don't know what the inhabitants may be like, so I think we'd better close the doors, and drop on the top of that mountain spur running out between the two rivers into the bay. Do you notice how curious the water looks after the earth-seas; bright silver, instead of blue and green?"

"Oh, it's just lovely," said Zaidie. "Let's go down and have a walk. There's nothing to be afraid of. You'll never make me believe that a world like this can be inhabited by anything dangerous.

"Perhaps, but we mustn't forget what happened on Mars; still, there's one thing, we haven't been tackled by any aerial fleets yet."

"I don't think the people here want air-ships. They can fly themselves. Look! there are a lot of them coming to meet us. That was a rather wicked remark of yours about the half-way house to Heaven; but those certainly look something like angels."

As Zaidie said this, after a somewhat lengthy pause, during which the Astronef had descended to within a few hundred feet of the mountain-spur, she handed a pair of field-glasses to her husband and pointed downward towards an island which lay a couple of miles or so off the end of the spur.

Redgrave put the glasses to his eyes, and, as he took a long look through them, moving them slowly up and down, and from side to side, he saw hundreds of winged figures rising from the island and soaring towards them.

"You were right, dear," he said, without taking the glass from his eyes, "and so was I. If those aren't angels, they're certainly something like men, and, I suppose, women too, who can fly. We may as well stop here and wait for them. I wonder what sort of an animal they take the Astronef for."

He sent a message down the tube to Murgatroyd, and gave a turn and a half to the steering wheel. The propellers slowed down and the Astronef landed with a hardly perceptible shock in the midst of a little plateau covered with a thick soft moss of a pale yellowish green, and fringed by a belt of trees which seemed to be over three hundred feet high, and whose foliage was a deep golden bronze.

They had scarcely landed before the flying figures reappeared over the tree-tops and swept downwards in long spiral curves towards the Astronef.

"If they're not angels, they're very like them," said Zaidie, putting down her glasses.

"There's one thing," replied her husband; "they fly a lot better than the old masters' angels or Dore's could have done, because they have tails —or at least something that seems to serve the same purpose, and yet they haven't got feathers."

"Yes, they have, at least round the edges of their wings or whatever they are, and they've got clothes, too, silk tunics or something of that sort —and there are men and women."

"You're quite right. Those fringes down their legs are feathers, and that's how they fly."

The flying figures which came hovering near to the Astronef, without evincing any apparent sign of fear, were certainly the strangest that human eyes had looked upon. In some respects they had a sufficient resemblance to human form for them to be taken for winged men and women, while in another they bore a decided resemblance to birds. Their bodies and limbs were almost human in shape, but of slenderer and lighter build; and from the shoulder-blades and muscles of the back there sprang a pair of wings arching up above their heads.

The body was covered in front and down the back between the wings with a sort of tunic of a light, silken-looking material, which must have been clothing, since there were many different colours.

In stature these inhabitants of the Love-Star varied from about five feet six to five feet, but both the taller and the shorter of them were all of nearly the same size, from which it was easy to conclude that this difference in stature was on Venus, as well as on the Earth, one of the broad distinctions between the sexes.

They flew once or twice completely round the Astronef with an exquisite ease and grace which made Zaidie exclaim: "Now, why weren't we made like that on Earth!"

To which Redgrave, after a look at the barometer, replied:

"Partly, I suppose, because we weren't built that way, and partly because we don't live in an atmosphere about two and a half times as dense as ours."

Then several of the winged figures alighted on the mossy covering of the plain and walked towards the vessel.

"Why, they walk just like us, only much more prettily!" said Zaidie. "And look what funny little faces they've got! Half bird, half human, and soft, downy feathers instead of hair. I wonder whether they talk or sing. I wish you'd open the doors again, Lenox. I'm sure they can't possibly mean us any harm; they are far too innocent for that. What soft eyes they have, and what a thousand pities it is we shan't be able to understand them."

They had left the conning-tower and both his lordship and Murgatroyd were throwing open the sliding doors and, to Zaidie's considerable displeasure, getting the deck Maxims ready for action in case they should be needed. As soon as the doors were open Zaidie's judgement of the inhabitants of Venus was entirely justified.

Murgatroyd was throwing open the sliding doors.

Without the slightest sign of fear, but with very evident astonishment in their round golden-yellow eyes, they came walking close up to the sides of the Astronef; Some of them stroked her smooth, shining sides with their little hands, which Zaidie now found had only three fingers and a thumb. Many ages before they might have been bird's claws, but now they were soft and pink and plump, utterly strange to work as manual work is understood upon Earth.

"Just fancy getting Maxim guns ready to shoot those delightful things," said Zaidie, almost indignantly, as she went towards the doorway from which the gangway ladder ran down to the soft, mossy turf. "Why, not one of them has got a weapon of any sort; and just listen," she went on, stopping in the opening of the doorway, "have you ever heard music like that on earth? I haven't. I suppose it's the way they talk. I'd give a good deal to be able to understand them. But still, it's very lovely, isn't it?"

"Ay, like the voices of syrens enticing honest folk to destruction," said Murgatroyd, speaking for the first time since the Astronef had landed; for this big, grizzled, taciturn Yorkshireman, who looked upon the whole cruise through Space as a mad and almost impious adventure, which nothing but his hereditary loyalty to his master's name and family could have persuaded him to share in, had grown more and more silent as the millions of miles between the Astronef and his native Yorkshire village had multiplied day by day.

"Syrens—and why not?" laughed Redgrave. "Yes, Zaidie, I never heard anything like that before. Unearthly, of course it is; but then we're not on Earth. Now, Zaidie, they seem to talk in song-language. You did pretty well on Mars with your sign-language, suppose we go out and show them that you can speak the song-language, too."

"What do you mean?" she said; "sing them something?"

"Yes," he replied, "they'll try to talk to you in song, and you won't be able to understand them; at least, not as far as words and sentences go. But music is the universal language on Earth, and there's no reason why it shouldn't be the same through the solar system. Come along, tune up, little woman!"

They went together down the gangway stairs, he dressed in an ordinary English tweed grey suit, with a golf cap on the back of his head, and she in the last and daintiest of costumes which had combined the art of Paris and London and New York before the Astronef soared up from Central Park.

The moment that she set foot on the golden-yellow sward she was surrounded by a swarm of the winged, and yet strangely human creatures. Those nearest to her came and touched her hands and face, and stroked the folds of her dress. Others looked into her violet-blue eyes, and others put out their queer little hands and touched her hair.

This and her clothing seemed to be the most wonderful experience for them, saving always the fact that she had no wings.

Redgrave kept close beside her until he was satisfied that these strange half-human, and yet wholly interesting creatures were innocent of any intention of harm, and when he saw two of the winged daughters of the Love-Star put up their hands and touch the thick coils of her hair, he said:

"Take those pins and things out and let it down. They seem to think that your hair's part of your head. It's the first chance you've had to work a miracle, so you may as well do it. Show them the most beautiful thing they've ever seen."

"What babies you men can be when you get sentimental!" laughed Zaidie, as she put her hands up to her head. "How do you know that this may not be ugly in their eyes?"

"Quite impossible!" he replied. "They're a great deal too pretty themselves to think you ugly."

While he was speaking Zaidie had taken off a Spanish mantilla which she had thrown over her head as she came out, and which the ladies of Venus seemed to think was part of her hair. Then she took out the comb and one or two hairpins which kept the coils in position, deftly caught the ends, and then, after a few rapid movements of her fingers, she shook her head, and the wondering crowd about her saw, what seemed to them a shimmering veil, half gold, half silver, in the strange, reflected light from the cloud-veil, fall down from her head over her shoulders.

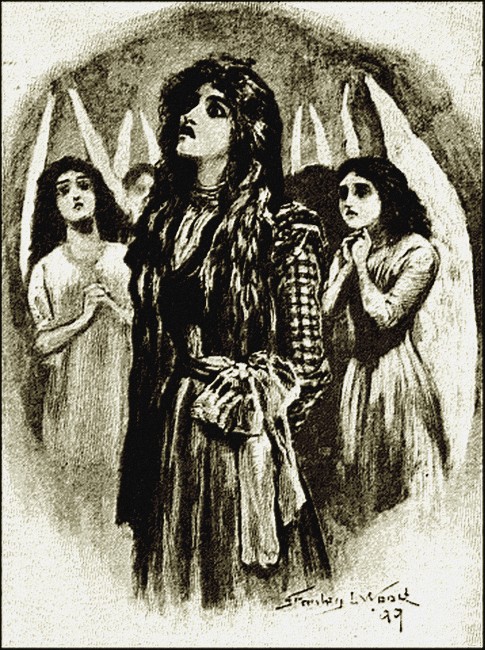

A shimmering veil fell down from her head over her shoulders.

They crowded still more closely round her, but so quietly and so gently that she felt nothing more than the touch of wondering hands on her arms, and dress, and hair. Her husband, as he said afterwards, was "absolutely out of it." They seemed to imagine him to be a kind of uncouth monster, possibly the slave of this radiant being which had come so strangely from somewhere beyond the cloud-veil. They looked at him with their golden-yellow eyes wide open, and some of them came up rather timidly and touched his clothes, which they seemed to think were his skin.

Then one or two, more daring, put their little hands up to his face and touched his moustache, and all of them, while both examinations were going on, kept up a running conversation of cooing and singing which evidently conveyed their ideas from one to the other on the subject of this most marvellous visit of these two strange beings with neither wings nor feathers, but who, most undoubtedly, had other means of flying, since it was quite certain that they had come from another world.

There was a low cooing note, something like the language in which doves converse, and which formed a sort of undertone. But every moment this rose here and there into higher notes, evidently expressing wonder or admiration, or both.

"You were right about the universal language," said Redgrave, when he had submitted to the stroking process for a few moments. "These people talk in music, and, as far as I can see or hear, their opinion of us, or, at least, of you, is distinctly flattering. I don't know what they take me for, and I don't care, but, as we'd better make friends with them, suppose you sing them 'Home, Sweet Home,' or 'The Swanee River.' I shouldn't wonder if they consider our talking voices most horrible discords, so you might as well give them something different."

While he was speaking the sounds about them suddenly hushed, and, as Redgrave said afterwards, it was something like the silence that follows a cannon shot. Then, in the midst of the hush, Zaidie put her hands behind her, looked up towards the luminous silver surface which formed the only visible sky of Venus, and began to sing "The Swanee River."

The clear, sweet notes rang up through the midst of a sudden silence. The sons and daughters of the Love-Star ceased the low, half-humming, half-cooing tones in which they seemed to be whispering to each other, and Zaidie sang the old plantation song through for the first time that a human voice had sung it to ears other than human.

Zaidie sang the old plantation song.

As the last note thrilled sweetly from her lips she looked round at the crowd of strange half-human figures about her, and something in their unlikeness to her own kind brought back to her mind the familiar scenes which lay so far away, so many millions of miles across the dark and silent Ocean of Space.

Other winged figures, attracted by the sound of her singing had crossed the trees, and these, during the silence which came after the singing of the song, were swiftly followed by others, until there were nearly a thousand of them gathered about the side of the Astronef.

There was no crowding or jostling among them. Each one treated every other with the most perfect gentleness and courtesy. No such thing as enmity or ill-feeling seemed to exist among them, and, in perfect silence, they waited for Zaidie to continue what they thought was her first speech of greeting. The temper of the throng somehow coincided exactly with the mood which her own memories had brought to her, and the next moment she sent the first line of "Home Sweet Home" soaring up to the cloud-veiled sky.

As the notes rang up into the still, soft air a deeper hush fell on the listening throng. Heads were bowed with a gesture almost of adoration, and many of those standing nearest to her bent their bodies forward, and expanded their wings, bringing them together over their breasts with a motion which, as they afterwards learnt, was intended to convey the idea of wonder and admiration, mingled with something like a sentiment of worship.

Zaidie sang the sweet old song through from end to end, forgetting for the time being everything but the home she had left behind her on the banks of the Hudson. As the last notes left her lips, she turned round to Redgrave and looked at him with eyes dim with the first tears that had filled them since her father's death, and said, as he caught hold of her outstretched hand:

"I believe they've understood every word of it."

"Or, at any rate, every note. You may be quite certain of that," he replied. "If you had done that on Mars it might have been even more effective than the Maxims."

"For goodness sake don't talk about things like that in a heaven like this! Oh, listen! They've got the tune already!" It was true! The dwellers of the love-star, whose speech was song, had instantly recognised the sweetness of the sweetest of all earthly songs. They had, of course, no idea of the meaning of the words; but the music spoke to them and told them that this fair visitant from another world could speak the same speech as theirs. Every note and cadence was repeated with absolute fidelity, and so the speech, common to the two far-distant worlds, became a link connecting, this wandering son and daughter of the Earth with the sons and daughters of the Love-Star.

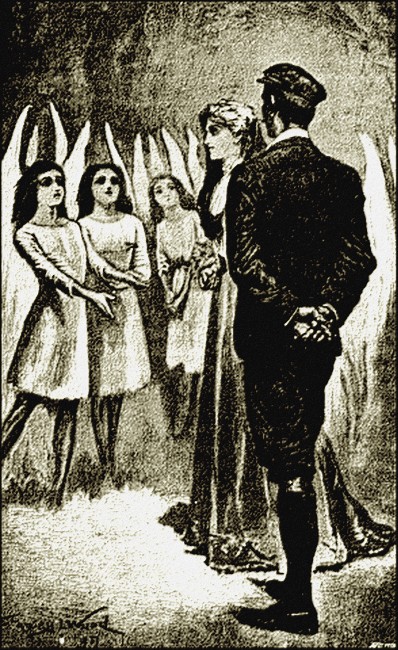

The throng fell back a little and two figures; apparently male and female, came to Zaidie and held out their right hands and began addressing her in perfectly harmonised song, which, though utterly unintelligible to her in the sense of speech, expressed sentiments which could not possibly be mistaken, as there was a faint suggestion of the old English song running through the little song-speech that they made, and both Zaidie and her husband rightly concluded that it was intended to convey a welcome to the strangers from beyond the cloud-veil.

They held out their right hands and began

addressing her in perfectly harmonised song.

And then the strangest of all possible conversations began. Redgrave, who had no more notion of music than a walrus, perforce kept silence. In fact, he noticed with a certain displeasure which vanished speedily with a musical, and half-malicious little laugh from Zaidie, that when he spoke the bird-folk drew back a little and looked in something like astonishment at him, but Zaidie was already in touch with them, and half by song and half by signs she very soon gave them an idea of what they were and where they had come from. Her husband afterwards told her that it was the best piece of operatic acting he had ever seen, and, considering all the circumstances, this was very possibly true.

In the end the two, who had come to give her what seemed to be the formal greeting, were invited into the Astronef. They went on board without the slightest sign of mistrust, and with only an expression of mild wonder on their beautiful and almost childlike faces.

Then, while the other doors were being closed, Zaidie stood at the open one above the gangway and made signs showing that they were going up beyond the clouds and then down into the valley, and as she made the signs she sang through the scale, her voice rising and falling in harmony with her gestures. The Bird-Folk understood her instantly, and as the door closed and the Astronef rose from the ground, a thousand wings were outspread and presently hundreds of beautiful soaring forms were circling about the Navigator of the Stars.

"Don't they look lovely," said Zaidie. "I wonder what they would think if they could see us flying above New York or London or Paris with an escort like this. I suppose they're going to show us the way. Perhaps they have a city down there. Suppose you were to go and get a bottle of champagne and see if Master Cupid and Miss Venus would like a drink. We'll see then if our nectar is anything like theirs."

Redgrave went below. Meanwhile, for lack of other possible conversation, Zaidie began to sing the last verse of "Never Again." The melody almost exactly described the upward motion of the Astronef, and she could see that it was instantly understood, for when she had finished, their two voices joined in an almost exact imitation of it.

When Redgrave brought up the wine and the glasses they looked at them without any sign of surprise. The pop of the cork did not even make them look round.

"Evidently a semi-angelic people, living on nectar and ambrosia, with nectar very like our own," he said, as he filled the glasses. "Perhaps you'd better give it to them. They seem to understand you better than they do me —you being, of course, a good bit nearer to the angels than I am."

"Thanks!" she said, as she took a couple of glasses up, wondering a little what their visitors would do with them. Somewhat to her surprise, they took them with a little bow and a smile and sipped at the wine, first with a little glint of wonder in their eyes, and then with smiles which are unmistakable evidence of perfect appreciation.

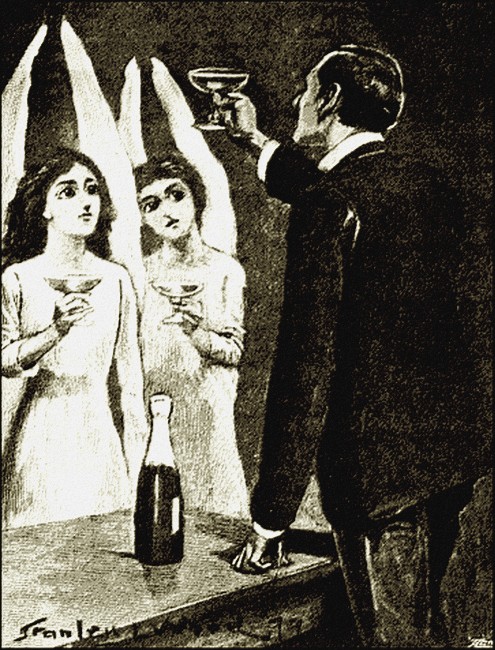

"I thought so," said Redgrave, as he raised his own glass, and bowed gravely towards them. "This is our nearest approach to nectar, and they seem to recognise it."

Redgrave raised his own glass.

"And don't they just look like the sort of people who live on it, and, of course, other things," added Zaidie, as she too lifted her glass, and looked with laughing eyes across the brim at her two guests.

But meanwhile Murgatroyd had been applying the repulsive force a little too strongly. The Astronef shot up with a rapidity which soon left her winged escort far below. She entered the cloud-veil and passed beyond it. The instant that the unclouded sun-rays struck the glass-roofing of the upper deck, their two guests, who had been moving about examining everything with a childlike curiosity, closed their eyes and clasped their hands over them, uttering little cries, tuneful and musical, but still with a note of strange discord in them.

"Lenox, we must go down again," exclaimed Zaidie. "Don't you see they can't stand the light; it hurls them. Perhaps, poor dears, it's the first time they've ever been hurt in their lives. I don't believe they have any of our ideas of pain or sorrow or anything of that sort. Take us back under the clouds, quick, or we may blind them."

Before she had finished speaking, Redgrave had sent a signal down to Murgatroyd, and the Astronef began to drop back again towards the surface of the cloud-sea. Zaidie had, meanwhile, gone to her lady guest and dropped the black lace mantilla over her head, and, as she did so, she caught herself saying:

"There, dear, we shall soon be back in your own light. I hope it hasn't hurt you. It was very stupid of us to do a thing like that."

The answer came in a little cooing murmur, which said: "Thank you!" quite as effectively as any earthly words could have done, and then the Astronef dropped through the cloud-sea. The soaring forms of her lost escort came into view again and clustered about her; and, surrounded by them, she dropped, in obedience to their signs, down between the tremendous mountains and towards the island, thick with golden foliage, which lay two or three earth-miles out in a bay, where four converging rivers spread out into the sea.

It would take the best part of a volume rather than a few lines to give even an imperfect conception of the purely Arcadian delights with which the hours of the next ten days and nights were filled; but some idea of what the Space-voyagers experienced may be gathered from this extract of a conversation which took place in the saloon of the Astronef on the eleventh evening.

"But look here, Zaidie," said his lordship, "as we've found a world which is certainly much more delightful than our own, why shouldn't we stop here a bit? The air suits us and the people are simply enchanting. I think they like us, and I'm sure you're in love with every one of them, male and female. Of course, it's rather a pity that we can't fly unless we do it in the Astronef. But that's only a detail. You're enjoying yourself thoroughly, and I never saw you looking better or, if possible, more beautiful; and why on earth —or Venus—do you want to go?"

She looked at him steadily for a few moments, and with an expression which he had never seen on her face or in her eyes before, and then she said slowly and very sweetly, although there was something like a note of solemnity running through her tone:—

"I altogether agree with you, dear; but there is something which you don't seem to have noticed. As you say, we have had a perfectly delightful time. It's a delicious world, and just everything that one would think it to be, either Aurora or Hesperus looked at from the Earth; but if we were to stop here we should be committing one of the greatest crimes, perhaps the greatest, that ever was committed within the limits of the Solar System."

"My dear Zaidie, what in the name of what we used to call morals on the earth, do you mean?"

"Just this," she replied, leaning a little towards him in her deck chair. "These people, half angels, and half men and women, welcomed us after we dropped through their cloud-veil, as friends; a bit strange to them, certainly, but still they welcomed us as friends. They've taken us into their palaces, they've given us, as one might say, the whole planet. Everything was ours that we liked to take."

"We've been living with them ten days now, and neither you nor I, nor even Murgatroyd, who, like the old Puritan that he is, seems to see sin or wrong in everything that looks nice, has seen a single sign among them that they know anything about what we call sin or wrong on Earth."

"I think I understand what you're driving at," said Redgrave. "You mean, I suppose, that this world is something like Eden before the fall, and that you and I—oh—but that's all rubbish you know."

She got up out of her chair and, leaning over his, put her arm round his shoulder. Then she said very softly: "I see you understand what I mean, Lenox It doesn't matter how good you think me or I think you, but we have our original sin. You're an earthly man and I'm an earthly woman, and, as I'm your wife, I can say it plainly. We may think a good bit of each other, but that's no reason why we shouldn't be a couple of plague-spots in a sinless world like this."

She got up out of her chair and, leaning

over his, put her arm round his shoulder.

Their eyes met, and he understood. Then he got up and went down to the engine-room.

A couple of minutes later the Astronef sprang upwards from the midst of the delightful valley in which she was resting. In five minutes she had passed through the cloud-veil, and the next morning when their new friends came to visit them and found that they had vanished back into Space, there was sorrow for the first time among the sons and daughters of the Love-Star.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.