RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

FOR their honeymoon Rollo Lenox Smeaton Aubrey, Earl of Redgrave, and his bride, Lilla Zaidie, leave the earth on a visit to the moon and the principal planets, their sole companion being Andrew Murgatroyd, an old engineer who had superintended the building of the Asfronef, in which the journey is made. By means of the "R. Force," or Anti-Gravitational Force, of the secret of which Lord Redgrave is the sole possessor, they are able to navigate with precision and safety the limitless ocean of space. Their adventures on the Moon, Mars, and Venus have been described in the first three stories of the series.

"FIVE hundred million miles from the earth and forty-seven million miles from Jupiter," said his lordship, as he came into breakfast on the morning of the twenty-eighth day after leaving Venus.

During this brief period the Astronef had recrossed the orbits of the Earth and Mars and passed through that marvellous region of the Solar System, the Belt of the Asteroids. Nearly a hundred million miles of their journey had lain through this zone, in which hundreds and possibly thousands of tiny planets revolve in vast orbits round the Sun.

Then had come a desert void of over three hundred million miles, through which the Astronef voyaged alone, surrounded by the ever-constant splendours of the Heavens, but visited only now and then by one of those Spectres of Space, which we call comets.

Astern, the disc of the Sun steadily diminished, and ahead, the grey-blue shape of Jupiter, the Giant of the Solar System, had grown larger and larger until now they could see it as it had never been seen before—a gigantic three-quarter moon filling up the whole Heavens in front of them almost from Zenith to Nadir.

Its four satellites, Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Calisto were distinctly visible to the naked eye, and Europa and Ganymede happened to be in such a position with regard to the Astronef that her crew could see not only the bright sides turned towards the sun, but also the black shadow-spots which they cast on the cloud-veiled face of the huge planet.

"Five hundred million miles!" said Zaidie, with a little shiver, "that seems an awful long way from home, doesn't it? Though, of course, we've brought our home with us to a certain extent. Still I often wonder what they are thinking about us on the dear old earth. I don't suppose anyone ever expects to see us again. However, it's no good getting homesick in the middle of a journey when you're outward bound."

They were now falling very rapidly towards the huge planet, and, as the crescent approached the full they were able to examine the mysterious bands as human observers had never examined them before. For hours they sat almost silent at their telescopes, trying to probe the mystery which has baffled human science since the days of Gallileo.

"I believe I was right, or, in other words, the people I got the idea from are," said Redgrave eventually, as they approached the orbit of Calisto, which revolves at a distance of about eleven hundred thousand miles from the surface of the planet.

"Those belts are made of clouds or vapour in some stage or other. The lightest—the ones along the equator and what we should call the Temperate Zones—are the highest, and therefore coolest and whitest. The dark ones are the lowest and hottest. I daresay they are more like what we call volcanic clouds. Do you see how they keep changing? That's what's bothered our astronomers. Look at that big one yonder a bit to the north, going from brown to red. I suppose that's something like the famous red spot which they have been puzzling about. What do you make of it?"

"Well," said Zaidie, looking up from her telescope, "it's quite certain that the glare must come from underneath. It can't be sunlight, because the poor old sun doesn't seem to have strength enough to make a decent sunset or sunrise here, and look how it's running along to the westward! What does that mean, do you think?"

"I should say it means that some half-formed Jovian Continent has been flung sky high by a big burst-up underneath, and that's the blaze of the incandescent stuff running along. Just fancy a continent, say ten times the size of Asia, being split up and sent flying in a few moments like that. Look, there's another one to the north. On the whole, dear, I don't think we should find the climate on the other side of those clouds very salubrious. Still, as they say the atmosphere of Jupiter is about ten thousand miles thick, we may be able to get near enough to see something of what's going on.

"Meanwhile, here comes Calisto. Look at his shadow flying across the clouds. And there's Ganymede coming up after him, and Europa behind him. Talk about eclipses, they must be about as common here as thunderstorms are with us."

"We don't have a thunderstorm every day," corrected Zaidie, "but on Jupiter they have two or three eclipses every day. Meanwhile, there goes Jupiter himself. What a difference distance makes! This little thing is only a trifle larger than our moon, and it's hiding everything else."

As she was speaking, the full-orbed disc of Calisto, measuring nearly three thousand miles across, swept between them and the planet. It shone with a clear, somewhat reddish light like that of Mars. The Astronef was feeling its attraction strongly, and Redgrave went to the levers and turned on about a fifth of the R. Force to avoid contact with it.

"Another dead world," said Redgrave, as the surface of Calisto revolved swiftly beneath them, "or, at any rate, a dying one. There must be an atmosphere of some sort, or else that snow and ice wouldn't be there, and the land would be either black or white as it was on the Moon. It's not worth while landing there. Ganymede will be much more interesting."

Zaidie took half-a-dozen photographs of the surface of Calisto while they were passing it at a distance of about a hundred miles, and then went to get lunch ready.

When they got on to the upper deck again Calisto was already a half-moon in the upper sky nearly five hundred thousand miles away and the full orb of Ganymede, shining with a pale golden light, lay outspread beneath them. A thin, bluish-grey arc of the giant planet over-arched its western edge.

"I think we shall find something like a world here," said Zaidie, when she had taken her first look through her telescope. "There's an atmosphere and what looks like thin clouds. Continents, and oceans, too! And what is that light shining up between the breaks? Isn't it something like our Aurora?"

As the Astronef fell towards the surface of Ganymede she crossed its northern pole, and the nearer they got the plainer it became that a light very like the terrestrial Aurora was playing about it, illuminating the thin, yellow clouds with a bluish-violet light, which made magnificent contrasts of colouring amongst them.

"Let us go down there and see what it's like," said Zaidie. "There must be something nice under all those lovely colours."

Redgrave checked the R. Force and the Astronef fell obliquely across the pole towards the equator. As they approached the luminous clouds Redgrave turned it on again, and they sank slowly through a glowing mist of innumerable colours, until the surface of Ganymede came into plain view about ten miles below them.

What they saw then was the strangest sight they had beheld since they had left the Earth. As far as their eyes could reach, the surface of Ganymede was covered with vast orderly patches, mostly rectangular, of what they at first took for ice, but which they soon found to be a something that was self-illuminating.

"Glorified hot houses, as I'm alive," exclaimed Redgrave. "Whole cities under glass, fields, too, and lit by electricity or something very like it. Zaidie, we shall find human beings down there."

"Well, if we do I hope they won't be like the half-human things we found on Mars! But isn't it all just lovely! Only there doesn't seem to be anything outside the cities, at least nothing but bare, flat ground with a few rugged mountains here and there. See, there's a nice level plain near the big glass city, or whatever it is. Suppose we go down there."

Redgrave checked the after-engine which was driving them obliquely over the surface of the satellite, and the Astronef fell vertically towards a bare flat plain of what looked like deep yellow sand, which spread for miles alongside one of the glittering cities of glass.

"Oh, look, they've seen us!" exclaimed Zaidie. "I do hope they're going to be as friendly as those dear people on Venus were."

"I hope so," replied Redgrave, "but if they're not, we've got the guns ready."

As he said this about twenty streams of an intense bluish light suddenly shot up all round them, concentrating themselves upon the hull of the Astronef, which was now about a mile and a half from the surface. The light was so intense that the rays of the sun were lost in it. They looked at each other, and found that their faces were almost perfectly white in it. The plain and the city below had vanished.

To look downwards was like staring straight into the focus of a ten thousand candlepower electric arc lamp. It was so intolerable that Redgrave closed the lower shutters, and meanwhile he found that the Astronef had ceased to descend. He shut off more of the R. force, but it produced no effect. The Astronef remained stationary. Then he ordered Murgatroyd to set the propellers in motion. The engineer pulled the starting levers, and then came up out of the engine-room and said to Lord Redgrave:

"It's no good my lord; I don't know what devil's world we've got into now, but they won't work. If I thought that engines could be bewitched-—"

"Oh, nonsense, Andrew!" said his lordship rather testily. "It's perfectly simple; those people down there, whoever they are, have got some way of demagnetising us, or else they've got the R. force too, and they're applying it against us to stop us going down. Apparently they don't want us. No, that's just to show us that they can stop us if they want to. The light's going down. Begin dropping a bit. Don't start the propellers, but just go and see that the guns are all right in case of accidents."

The old engineer nodded and went back to his engines, looking considerably scared. As he spoke the brilliancy of the light faded rapidly and the Astronef began to sink towards the surface.

As a precaution against their being allowed to drop with force enough to cause a disaster, Redgrave turned the R. Force on again and they dropped slowly towards the plain, through what seemed like a halo of perfectly white light. When she was within a couple of hundred yards of the ground a winged car of exquisitely graceful shape, rose from the roof of one of the huge glass buildings nearest to them, flew swiftly towards them, and after circling once round the dome of the upper deck, ran close alongside.

The car was occupied by two figures of distinctly human form but rather more than human stature. Both were dressed in long, close-fitting garments of what seemed like a golden brown fleece. Their heads were covered with a close hood and their hands with thin, close-fitting gloves.

"What an exceedingly handsome man!" said Zaidie, as one of them stood up. "I never saw such a noble-looking face in my life; it's half philosopher, half saint. Of course, you won't be jealous."

"Oh, nonsense!" he laughed. "It would be quite impossible to imagine you in love with either. But he is handsome, and evidently friendly— there's no mistaking that. Answer him, Zaidie; you can do it better than I can." The car had now come close alongside. The standing figure stretched its hands out, palms upward, smiled a smile which Zaidie thought was very sweetly solemn, next the head was bowed, and the gloved hands brought back and crossed over his breast. Zaidie imitated the movements exactly. Then, as the figure raised its head, she raised hers, and she found herself looking into a pair of large luminous eyes, such as she could have imagined under the brows of an angel. As they met hers, a look of unmistakable wonder and admiration came into them. Redgrave was standing just behind her; she took him by the hand and drew him beside her, saying with a little laugh:

"Now, please look as pleasant as you can; I am sure they are very friendly. A man with a face like that couldn't mean any harm."

The figure repeated the motions to Redgrave, who returned them, perhaps a trifle awkwardly. Then the car began to descend, and the figure beckoned to them to follow.

"You'd better go and wrap up, dear. From the gentleman's dress it seems pretty cold outside, though the air is evidently quite breathable," said Redgrave, as the Astronef began to drop in company with the car. "At any rate, I'll try it first, and, if it isn't, we can put on our breathing-dresses."

When Zaidie had made her winter toilet, and Redgrave had found the air to be quite respirable, but of Arctic cold, they went down the gangway ladder about twenty minutes later.

The figure had got out of the car which was lying a few yards from them on the sandy plain, and came forward to meet them with both hands outstretched.

The figure... came forward to meet them with both hands outstretched.

Zaidie unhesitatingly held out hers, and a strange thrill ran through her as she felt them for the first time clasped gently by other than earthly hands, for the Venus folk had only been able to pat and stroke with their gentle little paws, somewhat as a kitten might do. The figure bowed its head again and said something in a low, melodious voice, which was, of course, quite unintelligible save for the evident friendliness of its tone. Then, releasing her hands, he took Redgrave's in the same fashion, and then led the way towards a vast, domed building of semi-opaque glass, or a substance which seemed to be something like a mixture of glass and mica, which appeared to be one of the entrance gates of the city.

When they reached it a huge sheet of frosted glass rose silently from the ground. They passed through, and it fell behind them. They found themselves in a great oval antechamber along each side of which stood triple rows of strangely shaped trees whose leaves gave off a subtle and most agreeable scent. The temperature here was several degrees higher, in fact about that of an English spring day, and Zaidie immediately threw open her big fur cloak saying:

"These good people seem to live in Winter Gardens, don't they? I don't think I shall want these things much while we're inside. I wonder what dear old Andrew would have thought of this if we could have persuaded him to leave the ship."

They followed their host through the antechamber towards a magnificent pointed arch, raised on clusters of small pillars each of a different coloured, highly polished stone which shone brilliantly in a light which seemed to come from nowhere. Another door, this time of pale, transparent, blue glass, rose as they approached; they passed under it and, as it fell behind them, half-a-dozen figures, considerably shorter and slighter than their host, came forward to meet them. He took off his gloves and cape and thick outer covering, and they were glad to follow his example for the atmosphere was now that of a warm June day.

The attendants, as they evidently were, took their wraps from them, looking at the furs and stroking them with evident wonder; but with nothing like the wonder which came into their wild, soft grey eyes when they looked at Zaidie, who, as usual when she arrived on a new world, was arrayed in one of her daintiest costumes.

Their host was now dressed in a tunic of a light blue material, which glistened with a lustre greater than that of the finest silk. It reached a little below his knees, and was confined at the waist by a sash of the same colour hut of somewhat deeper hue. His feet and legs were covered with stockings of the same material and colour, and his feet, which were small for his stature and exquisitely shaped, were shod with thin sandals of a material which looked like soft felt, and which made no noise as he walked over the delicately coloured mosaic pavement of the street—for such it actually was—which ran past the gate.

When he removed his cap they expected to find that he was bald like the Martians, but they were mistaken. His well-shaped head was covered with long, thick hair of a colour something between bronze and grey. A broad band of metal, looking like light gold, passed round the upper part of his forehead, and from under this the hair fell in gentle waves to below his shoulders.

For a few moments Zaidie and Redgrave stared about them in frank and silent wonder. They were standing in a broad street running in a straight line, apparently several miles, along the edge of a city of crystal. It was lined with double rows of trees with beds of brilliantly coloured flowers between them. From this street others went off at right angles and at regular intervals. The roof of the city appeared to be composed of an infinity of domes of enormous extent, supported by tall clusters of slender pillars standing at the street corners.

Presently their host touched Redgrave on the shoulder and pointed to a four-wheeled car of light framework and exquisite design, containing seats for four besides the driver, or guide, who sat behind. He held out his hand to Zaidie, and handed her to one of the front seats just as an earth-born gentleman might have done. Then he motioned to Redgrave to sit beside her, and mounted behind them.

The car immediately began to move silently, but with considerable speed, along the left-hand side of the outer street, which, like all the others, was divided by narrow strips of russet-coloured grass and flowering shrubs.

In a few minutes it swung round to the right, crossed the road, and entered a magnificent avenue, which, after a run of some four miles, ended in a vast, park-like square, measuring at least a mile each way.

The two sides of the avenue were busy with cars like their own, some carrying six people, and others only the driver. Those on each side of the road all went in the same direction. Those nearest to the broad side-walks between the houses and the first row of trees went at a moderate speed of five or six miles an hour, but along the inner sides, near the central line of trees, they seemed to be running as high as thirty miles an hour. Their occupants were nearly all dressed in clothes made of the same glistening, silky fabric as their host wore, but the colourings were of infinite variety. It was quite easy to distinguish between the sexes, although in stature they were almost equal.

The men were nearly all clothed as their host was. The women were dressed in flowing garments something after the Greek style, but they were of brighter hues, and much more lavishly embroidered than the men's tunics were. They also wore much more jewellery. Indeed, some of the younger ones glittered from head to foot with polished metal and gleaming stones.

The women were dressed in flowing garments...

"Could anyone ever have dreamt of such a lovely place?" said Zaidie, after their wondering eyes had become accustomed to the marvels about them, "and yet—oh dear, now I know what it reminds me of! Flammarion's book, 'The End Of The World,' where he describes the remnants of the human race dying of cold and hunger on the Equator in places something like this. I suppose the life of poor Ganymede is giving out, and that's why they've got to live in glorified Crystal Palaces like this, poor things."

"Poor things!" laughed Redgrave, "I'm afraid I can't agree with you there, dear. I never saw a jollier looking lot of people in my life. I daresay you're quite right, but they certainly seem to view their approaching end with considerable equanimity."

"Don't be horrid, Lenox! Fancy talking in that cold-blooded way about such delightful-looking people as these, why, they are even nicer than our dear bird-folk on Venus, and, of course, they are a great deal more like ourselves."

"Wherefore it stands to reason that they must be a great deal nicer!" he replied, with a glance which brought a brighter flush to her cheeks. Then he went on: "Ah, now I see the difference."

"What difference? Between what?"

"Between the daughter of Earth and the daughters of Ganymede," he replied. "You can blush, and I don't think they can. Haven't you noticed that, although they have the most exquisite skins and beautiful eyes and hair and all that sort of thing, not a man or woman of them has any colouring. I suppose that's the result of living for generations in a hothouse."

"Very likely," she said; "but has it struck you also that all the girls and women are either beautiful or handsome, and all the men, except the ones who seem to be servants or slaves, are something like Greek gods, or, at least, the sort of men you see on the Greek sculptures?"

"Survival of the fittest, I presume. These will be the descendants of the highest races of Ganymede,—the people who conceived the idea of prolonging human life like this and were able to carry it out. The inferior races would either perish of starvation or become their servants. That's what will happen on Earth, and there is no reason why it shouldn't have happened here."

As he said this the car swung out round a broad curve into the centre of the great square, and a little cry of amazement broke from Zaidie's lips as her glance roamed over the multiplying splendours about her.

In the centre of the square, in the midst of smooth lawns and flower beds of every conceivable shape and colour, and groves of flowering trees, stood a great, domed building, which they approached through an avenue of overarching trees interlaced with flowering creepers.

The car stopped at the foot of a triple flight of stairs of dazzling whiteness which led up to a broad, arched doorway. Several groups of people were sprinkled about the avenue and steps and the wide terrace which ran along the front of the building. They looked with keen, but perfectly well-mannered surprise at their strange visitors, and seemed to be discussing their appearance; but not a step was taken towards them nor was there the slightest sign of anything like vulgar curiosity.

"What perfect manners these dear people have!" said Zaidie, as they dismounted at the foot of the staircase. "I wonder what would happen if a couple of them were to be landed from a motor car in front of the Capitol at Washington. I suppose this is their Capitol, and we've been brought here to be put through our facings. What a pity we can't talk to them. I wonder if they'd believe our story if we could tell it."

"I've no doubt they know something of it already," replied Redgrave;" they're evidently people of immense intelligence. Intellectually, I daresay, we're mere children compared with them, and it's quite possible that they have developed senses of which we have no idea."

"And perhaps," added Zaidie, "all the time that we are talking to each other our friend here is quietly reading everything that is going on in our minds."

Whether this was so or not their host gave no sign of comprehension. He led them up the steps and through the great doorway where he was met by three splendidly dressed men even taller than himself.

"I feel beastly shabby among all these gorgeously attired personages," said Redgrave, looking down at his plain tweed suit, as they were conducted with every manifestation of politeness along the magnificent vestibule beyond.

At the end of the vestibule another door opened, and they were ushered into a large hall which was evidently a council-chamber. At the further end of it were three semicircular rows of seats made of the polished silvery metal, and in the centre and raised slightly above them another under a canopy of sky-blue silk. This seat and six others were occupied by men of most venerable aspect, in spite of the fact that their hair was just as long and thick and glossy as their host's or even as Zaidie's own.

The ceremony of introduction was exceedingly simple. Though they could not, of course, understand a word he said, it was evident from his eloquent gestures that their host described the way in which they had come from Space, and landed on the surface of the World of the Crystal Cities, as Zaidie subsequently rechristened Ganymede.

The President rose and took them by both hands in turn.

The President of the Senate or Council spoke a few sentences in a deep musical tone. Then their host, taking their hands, led them up to his seat, and the President rose and took them by both hands in turn. Then, with a grave smile of greeting, he bent his head and resumed his seat. They joined hands in turn with each of the six senators present, bowed their farewells in silence, and then went back with their host to the car.

They ran down the avenue, made a curving sweep round to the left— for all the paths in the great square were laid in curves, apparently to form a contrast to the straight streets—and presently stopped before the porch of one of the hundred palaces which surrounded it. This was their host's house, and their home during the rest of their sojourn on Ganymede.

It is, as I have already said, greatly to be regretted that the narrow limits of these brief narratives make it impossible for me to describe in detail all the experiences of Lord Redgrave and his bride during their Honeymoon in Space. Hereafter I hope to have an opportunity of doing so with the more ample assistance of her ladyship's diary; but for the present I must content myself with the outlines of the picture which she may some day consent to fill in.

The period of Ganymede's revolution round its gigantic primary is seven days, three hours, and forty-three minutes, practically a terrestrial week, and both of the daring navigators of Space describe this as the most interesting and delightful week in their lives, not even excepting the period which they spent in the Eden of the Morning Star.

There the inhabitants had never learnt to sin; here they had learnt the lesson that sin is mere foolishness, and that no really sensible or properly educated man or woman thinks crime worth committing.

The life of the Crystal Cities, of which they visited four in different parts of the satellite, using the Astronef as their vehicle, was one of peaceful industry and calm innocent enjoyment. It was quite plain that their first impressions of this aged world were correct. Outside the cities spread a universal desert on which life was impossible. There was hardly any moisture in the thin atmosphere. The rivers had dwindled into rivulets and the seas into vast, shallow marshes. The heat received from the Sun was only about a twenty-fifth of that received on the surface of the Earth, and this was drawn to the cities and collected and preserved under their glass domes by a number of devices which displayed superhuman intelligence.

The dwindling supplies of water were hoarded in vast subterranean reservoirs and by means of a perfect system of redistillation the priceless fluid was used over and over again both for human purposes and for irrigating the land within the cities.

Still the total quantity was steadily diminishing, for it was not only evaporating from the surface, but, as the orb cooled more and more rapidly towards its centre, it descended deeper and deeper below the surface, and could now only be reached by means of marvellously constructed borings and pumping machinery which extended down several miles into the ground.

The dwindling store of heat in the centre of the little world, which had now cooled through more than half its bulk, was utilised for warming the air of the cities, and also to drive the machinery which propelled it through the streets and squares. All work was done by electricity developed directly from this source, which also actuated the repulsive engines which had prevented the Astronef from descending.

In short, the inhabitants of Ganymede were engaged in a steady, ceaseless struggle to utilise the expiring natural forces of their world to prolong to the latest possible date their own lives and the exquisitely refined civilisation to which they had attained. They were, in fact, in exactly the same position in which the distant descendants of the human race may one day be expected to find themselves.

Their domestic life, as Zaidie and Lenox saw it while they were the guests of their host, was the perfection of simplicity and comfort, and their public life was characterised by a quiet but intense intellectuality which, as Zaidie had said, made them feel very much like children who had only just learnt to speak.

As they possessed magnificent telescopes, far surpassing any on earth, the wanderers were able to survey, not only the Solar System, but the other systems far beyond its limits as no other of their kind had ever been able to do before. They did not look through or into the telescopes. The lens was turned upon the object, which was thrown, enormously magnified, upon screens of what looked something like ground glass some fifty feet square. It was thus that they saw, not only the whole visible surface of Jupiter as he revolved above them and they about him, but also their native earth, sometimes a pale silver disc or crescent close to the edge of the Sun, visible only in the morning and the evening of Jupiter, and at other times like a little black spot crossing the glowing surface.

It was, of course, inevitable that the Astronef—which Murgatroyd could not be persuaded to leave once during their stay—should prove an object of intense interest to their hosts. They had solved the problem of the Resolution of Forces, and, as they were shown pictorially, a vessel had been made which embodied the principles of attraction and repulsion. It had risen from the surface of Ganymede, and then, possibly because its engines could not develop sufficient repulsive force, the tremendous pull of the giant planet had dragged it away. It had vanished through the cloud-belts towards the flaming surface beneath—and the experiment had never been repeated.

Here, however, was a vessel which had actually, as Redgrave had convinced his hosts by means of celestial maps and drawings of his own, left a planet close to the Sun, and safely crossed the tremendous gulf of six hundred and fifty million miles which separated Jupiter from the centre of the system. Moreover he had twice proved her powers by taking his host and two of his newly-made friends, the chief astronomers of Ganymede, on a short trip across space to Calisto and Europa, the second satellite of Jupiter, which, to their very grave interest they found had already passed the stage in which Ganymede was, and had lapsed into the icy silence of death.

It was these two journeys which led to the last adventure of the Astronef in the Jovian System. Both Redgrave and Zaidie had determined, at whatever risk, to pass through the cloud-belts of Jupiter, and catch a glimpse, if only a glimpse, of a world in the making. Their host and the two astronomers, after a certain amount of quiet discussion, accepted their invitation to accompany them, and on the morning of the eighth day after their landing on Ganymede, the Astronef rose from the plain outside the Crystal City, and directed her course towards the centre of the vast disc of Jupiter.

She was followed by the telescopes of all the observatories until she vanished through the brilliant cloud-band, eighty-five thousand miles long and some five thousand miles broad, which stretched from east to west of the planet. At the same moment the voyagers lost sight of Ganymede and his sister satellites.

The temperature of the interior of the Astronef began to rise as soon as the upper cloud-belt was passed. Under this, spread out a vast field of brown-red cloud, rent here and there into holes and gaps like those storm-cavities in the atmosphere of the Sun, which are commonly known as sun-spots. This lower stratum of cloud appeared to be the scene of terrific storms, compared with which the fiercest earthly tempests were mere zephyrs.

After falling some five hundred miles further they found themselves surrounded by what seemed an ocean of fire, but still the internal temperature had only risen from seventy to ninety-five. The engines were well under control. Only about a fourth of the total R. Force was being developed, and the Astronef was dropping swiftly, but steadily.

Redgrave, who was in the conning-tower controlling the engines, beckoned to Zaidie and said:

"Shall we go on?"

"Yes," she said. "Now we've got as far as this I want to see what Jupiter is like, and where you are not afraid to go, I'll go."

"If I'm afraid at all it's only because you are with me, Zaidie," he replied, "but I've only got a fourth of the power turned on yet, so there's plenty of margin."

The Astronef, therefore, continued to sink through what seemed to be a fathomless ocean of whirling, blazing clouds, and the internal temperature went on rising slowly but steadily. Their guests, without showing the slightest sign of any emotion, walked about the upper deck now singly and now together, apparently absorbed by the strange scene about them.

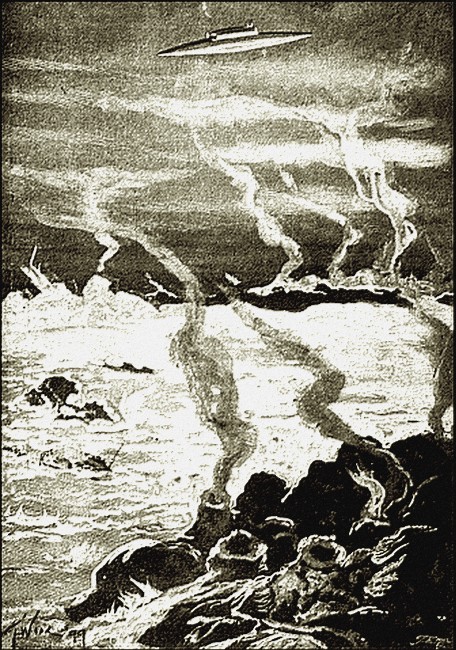

At length, after they had been dropping for some five hours by Astronef time, one of them, uttering a sharp exclamation, pointed to an enormous rift about fifty miles away. A dull, red glare was streaming up out of it. The next moment the brown cloud-floor beneath them seemed to split up into enormous wreaths of vapour, which whirled up on all sides of them, and a few minutes later they caught their first glimpse of the true surface of Jupiter.

The cloud-floor beneath them seemed to split up into enormous wreaths of vapour.

It lay as nearly as they could judge, some two thousand miles beneath them, a distance which the telescopes reduced to less than twenty; and they saw for a few moments the world that was in the making. Through floating seas of misty steam they beheld what seemed to them to be vast continents shape themselves and melt away into oceans of flames. Whole mountain ranges of glowing lava were hurled up miles high to take shape for an instant and then fall away again, leaving fathomless gulfs of fiery mist in their place.

Then waves of molten matter rose up again out of the gulfs, tens of miles high and hundreds of miles long, surged forward, and met with a concussion like that of millions of earthly thunder-clouds. Minute after minute they remained writhing and struggling with each other. flinging up spurts of flaming matter far above their crests. Other waves followed them, climbing up their bases as a sea-surge runs up the side of a smooth, slanting rock. Then from the midst of them a jet of living fire leapt up hundreds of miles into the lurid atmosphere above, and then, with a crash and a roar which shook the vast Jovian firmament, the battling lava-waves would split apart and sink down into the all-surrounding fire-ocean, like two grappling giants who had strangled each other in their final struggle.

"It's just Hell let loose!" said Murgatroyd to himself as he looked down upon the terrific scene through one of the portholes of the engine-room; "and, with all respect to my lord and her ladyship, those that come this near almost deserve to stop in it."

Meanwhile, Redgrave and Zaidie and their three guests were so absorbed in the tremendous spectacle, that for a few moments no one noticed that they were dropping faster and faster towards the world which Murgatroyd, according to his lights, had not inaptly described. As for Zaidie, all her fears were for the time being lost in wonder, until she saw her husband take a swift glance round upwards and downwards, and then go up into the conning-tower. She followed him quickly, and said:

"What is the matter, Lenox, are we falling too quickly?"

"Much faster than we should," he replied, sending a signal to Murgatroyd to increase the force by three-tenths.

The answering signal came back, but still the Astronef continued to fall with terrific rapidity, and the awful landscape beneath them—a landscape of fire and chaos—broadened out and became more and more distinct.

He sent two more signals down in quick succession. Three-fourths of the whole repulsive power of the engines was now being exerted, a force which would have been sufficient to hurl the Astronef up from the surface of the Earth like a feather in a whirlwind. Her downward course became a little slower, but still she did not stop. Zaidie, white to the lips, looked down upon the hideous scene beneath and slipped her hand through Redgrave's arm. He looked at her for an instant and then turned his head away with a jerk, and sent down the last signal.

The whole energy of the engines was now directing the maximum of the R. Force against the surface of Jupiter, but still, as every moment passed in a speechless agony of apprehension, it grew nearer and nearer. The fire-waves mounted higher and higher, the roar of the fiery surges grew louder and louder. Then, in a momentary lull, he put his arm round her, drew her close up to him, and kissed her and said:

"That's all we can do, dear. We've come too close and he's too strong for us."

She returned his kiss and said quite steadily:

"Well, at any rate, I'm with you, and it won't last long, will it?"

"Not very long now, I'm afraid," he said between his clenched teeth.

Almost the next moment they felt a little jerk beneath their feet— a jerk upwards; and Redgrave shook himself out of the half stupor into which he was falling and said:

"Hallo, what's that! I believe we're stopping—yes, we are— and we're beginning to rise, too. Look, dear, the clouds are coming down upon us—fast too! I wonder what sort of miracle that is. Ay, what's the matter, little woman?"

Zaidie's head had dropped heavily on his shoulder. A glance showed him that she had fainted. He could do nothing more in the conning-tower, so he picked her up and carried her towards the companion-way, past his three guests, who were standing in the middle of the upper deck round a table on which lay a large sheet of paper.

He took her below and laid her on her bed, and in a few minutes he had brought her to and told her that it was all right. Then he gave her a drink of brandy and water, and went hack on to the upper deck. As he reached the top of the stairway one of the astronomers came towards him with the sheet of paper in his hand, smiling gravely, and pointing to a sketch upon it.

He took the paper under one of the electric lights and looked at it. The sketch was a plan of the Jovian System. There were some signs written along one side, which he did not understand, but he divined that they were calculations. Still, there was no mistaking the diagram. There was a circle representing the huge bulk of Jupiter; there were four smaller circles at varying distances in a nearly straight line from it, and between the nearest of these and the planet was the figure of the Astronef, with an arrow pointing upwards.

"Ah, I see!" he said, forgetting for a moment that the other did not understand him, "That was the miracle! The four satellites came into line with us just as the pull of Jupiter was getting too much for our engines, and their combined pull just turned the scale. Well, thank God for that, sir, for in a few minutes more we should have been cinders!"

The astronomer smiled again as he took the paper back. Meanwhile the Astronef was rushing upward like a meteor through the clouds. In ten minutes the limits of the Jovian atmosphere were passed. Stars and gems and planets blazed out of the black vault of Space, and the great disc of the World that Is to Be once more covered the floor of Space beneath them—an ocean of cloud, covering continents of lava and seas of flame.

They passed Io and Europa, which changed from new to full moons as they sped by towards the Sun, and then the golden yellow crescent of Ganymede also began to fill out to the half and full disc, and by the tenth hour of earth-time after they had risen from its surface, the Astronef was once more lying beside the gate of the Crystal City.

At midnight on the second night after their return, the ringed shape of Saturn, attended by his eight satellites, hung in the zenith magnificently inviting. The Astronef's engines had been replenished after the exhaustion of their struggle with the might of Jupiter. Zaidie and Lenox said farewell to their friends of the dying world. The doors of the air chamber closed. The signal tinkled in the engine-room, and a few moments later a blur of white lights on the brown background of the surrounding desert was all they could distinguish of the Crystal City under whose domes they had seen and learnt so much.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.