THEY had been dining for once in a way tête-à-tête, and she - that is to say, Mrs. Sidney Calvert, a bride of eighteen months' standing - was half lying, half sitting in the depths of a big, cosy, saddle-bag armchair on one side of a bright fire of mixed wood and coal that was burning in one of the most improved imitations of the mediaeval fireplace. Her feet - very pretty little feet they were, too, and very daintily shod - were crossed, and poised on the heel of the right one at the corner of the black marble curb.

Dinner was over. The coffee service and the liqueur case were on the table, and Mr. Sidney Calvert, a well set-up young fellow of about thirty, with a handsome, good-humoured face which a close observer would have found curiously marred by a chilly glitter in the eyes and a hardness that was something more than firmness about the mouth, was walking up and down on the opposite side of the table smoking a cigarette.

Mrs. Calvert had just emptied her coffee cup, and as she put it down on a little three-legged console table by her side, she looked round at her husband and said:

"Really, Sid, I must say that I can't see why you should do

it. Of course it's a very splendid scheme and all that sort of thing,

but, surely you, one of the richest men in London, are rich enough to do

without it. I'm sure it's wrong, too. What should we think if somebody

managed to bottle up the atmosphere and made us pay for every breath we

drew? Besides, there must surely be a good deal of risk in deliberately

disturbing the economy of Nature in such a way. How are you going to get

to the Pole, too, to put up your works?"

"Really, Sid, I must say that I can't see why you should do

it. Of course it's a very splendid scheme and all that sort of thing,

but, surely you, one of the richest men in London, are rich enough to do

without it. I'm sure it's wrong, too. What should we think if somebody

managed to bottle up the atmosphere and made us pay for every breath we

drew? Besides, there must surely be a good deal of risk in deliberately

disturbing the economy of Nature in such a way. How are you going to get

to the Pole, too, to put up your works?"

"Well," he said, stopping for a moment in his walk and looking thoughtfully at the lighted end of his cigarette, "in the first place, as to the geography, I must remind you that the Magnetic Pole is not the North Pole. It is in Boothia Land, British North America, some 1500 miles south of the North Pole. Then, as to the risk, of course one can't do big things like this without taking a certain amount of it; but still, I think it will be mostly other people that will have to take it in this case.

"Their risk, you see, will come in when they find that cables and telephones and telegraphs won't work, and that no amount of steam-engine grinding can get up a respectable amount of electric light - when in short, all the electric plant of the world loses its value, and can't be set going without buying supplies from the Magnetic Polar Storage Company, or, in other words, from your humble servant and the few friends that he will be graciously pleased to let in on the ground floor. But that is a risk that they can easily overcome by just paying for it. Besides, there's no reason why we shouldn't improve the quality of the commodity. 'Our Extra Special Refined Lightning!' 'Our Triple Concentrated Essence of Electric Fluid' and 'Competent Thunder-Storms delivered at the Shortest Notice' would look very nice in advertisements, wouldn't they?"

"Don't you think that's rather a frivolous way of talking about a scheme which might end in ruining one of the most important industries in the world?" she said, laughing in spite of herself at the idea of delivering thunder-storms like pounds of butter or skeins of Berlin wool.

"Well, I'm afraid I can't argue that point with you because, you see, you will keep looking at me while you talk, and that isn't fair. Anyhow I'm equally sure that it would be quite impossible to run any business and make money out of it on the lines of the Sermon on the Mount. But, come, here's a convenient digression for both of us. That's the Professor, I expect."

"Shall I go?" she said, taking her feet off the fender.

"Certainly not, unless you wish to," he said; "or unless you think the scientific details are going to bore you."

"Oh, no, they won't do that," she said. "The Professor has such a perfectly charming way of putting them; and, besides, I want to know all that I can about it."

"Professor Kenyon, sir."

"Professor Kenyon, sir."

"Ah, good evening, Professor! So sorry you could not come to dinner." They both said this almost simultaneously as the man of science walked in.

"My wife and I were just discussing the ethics of this storage scheme when you came in," he went on. "Have you anything fresh to tell us about the practical aspects of it? I'm afraid she doesn't altogether approve of it, but as she is very anxious to hear all about it, I thought you wouldn't mind her making one of the audience."

"On the contrary, I shall be delighted," replied the Professor; "the more so as it will give me a sympathiser."

"I'm very glad to hear it," said Mrs. Calvert approvingly. "I think it will be a very wicked scheme if it succeeds, and a very foolish and expensive one if it fails."

"After which there is of course nothing mare to be said," laughed her husband, "except for the Professor to give his dispassionate opinion."

"Oh, it shall be dispassionate, I can assure you," he replied, noticing a little emphasis on the word. "The ethics of the matter are no business of mine, nor have I anything to do with its commercial bearings. You have asked me merely to look at technical possibilities and scientific probabilities, and of course I don't propose to go beyond these."

He took another sip at a cup of coffee that Mrs. Calvert had handed him, and went on

"I've had a long talk with Markovitch this afternoon, and I must confess that I never met a more ingenious man or one who knew as much about magnetism and electricity as he does. His theory that they are the celestial and terrestrial manifestations of the same force, and that what is popularly called electric fluid is developed only at the stage where they become one, is itself quite a stroke of genius, or, at least, it will be if the theory stands the test of experience. His idea of locating the storage works over the Magnetic Pole of the earth is another, and I am bound to confess that, after a very careful examination of his plans and designs, I am distinctly of opinion that, subject to one or two reservations, he will be able to do what he contemplates."

"And the reservations what are they?" asked Culvert a trifle eagerly.

"The first is one that it is absolutely necessary to make with regard to all untried schemes, and especially to such a gigantic one as this. Nature, you know, has a way of playing most unexpected pranks with people who take liberties with her. Just at the last moment, when you are on the verge of success, something that you confidently expect to happen doesn't happen, and there you are left in the lurch. It is utterly impossible to foresee anything of this kind, but you must clearly understand that if such a thing did happen it would ruin the enterprise just when you have spent the greatest part of the money on it - that is to say, at the end and not at the beginning."

"All right," said Calvert, "we'll take that risk. Now, what's the other reservation?"

"I was going to say something about the immense cost, but that I presume you are prepared for."

Calvert nodded, and he went on:

"Well, that point being disposed of, it remains to be said that it may be very dangerous - I mean to those who live on the spot, and will be actually engaged in the work."

"Then, I hope you won't think of going near the place, Sid!" interrupted Mrs. Calvert, with a very pretty assumption of wifely authority.

"We'll see about that later, little woman. It's early days yet to get frightened about possibilities. Well, Professor, what was it you were going to say? Any more warnings?"

The Professor's manner stiffened a little as he replied:

"Yes, it is a warning, Mr. Calvert. The fact is I feel bound to tell you that you propose to interfere very seriously with the distribution of one of the subtlest and least-known forces of Nature, and that the consequences of such an interference might be most disastrous, not only for those engaged in the work, but even the whole hemisphere, and possibly the whole planet.

"On the other hand, I think it is only fair to say that nothing more than a temporary disturbance may take place. You may, for instance, give us a series of very violent thunderstorms, with very heavy rains; or you may abolish thunderstorms and rain altogether until you get to work. Both prospects are within the bounds of possibility, and, at the same time, neither may come to anything."

"Well, I think that quite good enough to gamble on, Professor," said Calvert, who was thoroughly fascinated by the grandeur and magnitude, to say nothing of the dazzling financial aspects of the scheme. "I am very much obliged to you for putting it so clearly and nicely. Unless something very unexpected happens, we shall get to work on it at once. Just fancy what a glorious thing it will be to play Jove to the nations of the earth, and dole out lightning to them at so much a flash!"

"Well, I don't want to be ill-natured," said Mrs. Calvert, "but I must say that I hope the unexpected will happen. I think the whole thing is very wrong to begin with, and I shouldn't be at all surprised if you blew us all up, or struck us all dead with lightning, or even brought on the Day of judgment before its time. I think I shall go to Australia while you're doing it."

A LITTLE more than a year had passed since this after-dinner conversation in the diningroom of Mr. Sidney Calvert's London house. During that time the preparations for the great experiment had been swiftly but secretly carried out. Ship after ship loaded with machinery, fuel, and provisions, and carrying labourers and artificers to the number of some hundreds, had sailed away into the Atlantic, and had come back in ballast and with bare working crews on board of them. Mr. Calvert himself had disappeared and reappeared two or three times, and on his return he had neither admitted nor denied any of the various rumours which gradually got into circulation in the City and in the Press.

Some said that it was an expedition to the Pole, and that the machinery consisted partly of improved ice-breakers and newly-invented steam sledges, which were to attack the ice-hummocks after the fashion of battering rams, and so gradually smooth a road to the Pole. To these little details others added flying machines and navigable balloons. Others again declared that the object was to plough out the North-West passage and keep a waterway clear from Hudson's Bay to the Pacific all the year round, and yet others, somewhat less imaginative, pinned their faith to the founding of a great astronomical and meteorological observatory at the nearest possible point to the Pole, one of the objects of which was to be the determination of the true nature of the Aurora Borealis and the Zodiacal Light.

It was this last hypothesis that Mr. Calvert favoured as far as he could be said to favour any. There was a vagueness, and, at the same time, a distinction about a great scientific expedition which made it possible for him to give a sort of qualified countenance to the rumours without committing himself to anything, but so well had all his precautions been taken that not even a suspicion of the true object of the expedition to Boothia Land had got outside the little circle of those who were in his confidence.

So far everything had gone as Orloff Markovitch, the Russian Pole to whose extraordinary genius the inception and working out of the gigantic project were due, had expected and predicted. He himself was in supreme control of the unique and costly works which had grown up under his constant supervision on that lonely and desolate spot in the far North where the magnetic needle points straight down to the centre of the planet.

Professor Kenyon had paid a couple of visits with Calvert, once at the beginning of the work and once when it was nearing completion. So far not the slightest hitch or accident had occurred, and nothing abnormal had been noticed in connection with the earth's electrical phenomena save unusually frequent appearances of the Aurora Borealis, and a singular decrease in the deviation of the mariner's compass. Nevertheless, the Professor had firmly but politely refused to remain until the gigantic apparatus was set to work, and Calvert, too, had, with extreme reluctance, yielded to his wife's intreaties, and had come back to England about a month before the initial experiment was to be begun.

The twentieth of March, which was the day fixed for the commencement of operations, came and went, to Mrs. Calvert's intense relief, without anything out of the common happening. Though she knew that over a hundred thousand pounds of her husband's money had been sunk, she found it impossible not to feel a thrill of satisfaction in the hope that Markovitch had made his experiment and failed.

She knew that the great Calvert Company, which was practically himself, could very well afford it, and she would not have regretted the loss of three times the sum in exchange for the knowledge that Nature was to be allowed to dispose of her electrical forces as seemed good to her. As for her husband, he went about his business as usual, only displaying slight signs of suppressed excitement and anticipation now and then, as the weeks went by and nothing happened.

She had not carried out her threat of going to Australia. She had, however, escaped from the rigours of the English spring to a villa near Nice, where she was awaiting the arrival of her second baby, an event which she had found very useful in persuading her husband to stop away from the Magnetic Pole. Calvert himself was so busy with what might be called the home details of the scheme that lie had to spend the greater part of his time in London, and could only run over to Nice now and then.

It so happened that Miss Calvert put in an appearance a few days before she was expected, and therefore while her father was still in London. Her mother very naturally sent her maid with a telegram to inform him of the fact and ask him to come over at once. In about half-an-hour the maid came back with the form in her hand bringing a message from the telegraph office that, in consequence of some extraordinary accident, the wires had almost ceased to work properly and that no messages could be got through distinctly.

In the rapture of her new motherhood Kate Calvert had forgotten all about the great Storage Scheme, so she sent the maid back again with the request that the message should be sent off as soon as possible. Two hours later she sent again to ask if it had gone, and the reply came back that the wires had ceased working altogether and that no electrical communication by telegraph or telephone was for the present possible.

Then a terrible fear came to her. The experiment had been a success after all, and Markovitch's mysterious engines bad been all this time imperceptibly draining the earth of its electric fluid and storing it up in the vast accumulators which would only yield it back again at the bidding of the Trust which was controlled by her husband! Still she was a sensible little woman, and after the first shock she managed, for her baby's sake, to put the fear out of her mind, at any rate until her husband came. He would be with her in a day or two, and, perhaps, after all, it was only some strange but perfectly natural occurrence which Nature herself would set right in a few hours.

When it got dusk that night, and the electric lights were turned on, it was noticed that they gave an unusually dim and wavering light. The engines were worked to their highest power, and the lines were carefully examined. Nothing could be found wrong with them, but the lights refused to behave as usual, and the most extraordinary feature of the phenomenon was that exactly the same thing was happening in all the electrically lighted cities and towns in the northern hemisphere. By midnight, too, telegraphic and telephonic communication north of the Equator had practically ceased, and the electricians of Europe and America were at their wits' ends to discover any reason for this unheard of disaster, for such in sober truth it would be unless the apparently suspended force quickly resumed action on its own account. The next morning it was found that, so far as all the marvels of electrical science were concerned, the world had gone back a hundred years.

Then people began to awake to the magnitude of the catastrophe that had befallen the world. Civilised mankind had been suddenly deprived of the services of an obedient slave which it had come to look upon as indispensable.

But there was something even more serious than this to come. Observers in various parts of the hemisphere remembered than there hadn't been a thunder-storm anywhere for some weeks. Even the regions most frequently visited by them had had none. A most remarkable drought had also set in almost universally. A strange sickness, beginning with physical lassitude and depression of spirits which confounded the best medical science of the world was manifesting itself far and wide, and rapidly assuming the proportions of a gigantic epidemic.

In the physical world, too, metals were found to be afflicted with the same incomprehensible disease. Machinery of all sorts got "sick," to use a technical expression, and absolutely refused to act, and forges and foundries everywhere came to a standstill for the simple reason that metals seemed to have lost their best properties, and could no longer be utilised as they had been. Railway accidents and breakdowns on steamers, too, became matters of every day occurrence, for metals and driving wheels, piston rods and propeller shafts, had acquired an incomprehensible brittleness which only began to be understood when it was discovered that the electrical properties which iron and steel had formerly possessed had almost entirely disappeared.

So far Calvert had not wavered in his determination to make, as he thought, a colossal amount of money by his usurpation of one of the functions of Nature. To him the calamities which, it must be confessed, he had deliberately brought upon the world were only so many arguments for the ultimate success of the stupendous scheme. They were proof positive to the world, or at least they very soon would be, that the Calvert Storage Trust really did control the electricity of the Northern Hemisphere. From the Southern nothing had yet been heard beyond the news that the cables had ceased working.

Hence, as soon as he had demonstrated his power to restore matters to their normal condition, it was obvious that the world would have to pay his price under penalty of having the supply cut off again.

It was now getting towards the end of May. On the 1st of June, according to arrangement, Markovitch would stop his engines and permit the vast accumulation of electric fluid in his storage batteries to flow back into its accustomed channels. Then the Trust would issue its prospectus, setting forth the terms upon which it was prepared to permit the nations to enjoy that gift of Nature whose pricelessness the Trust had proved by demonstrating its own ability to corner it.

On the evening of May 25th Culvert was sitting in his sumptuous office in Victoria Street, writing by the light of a dozen wax candles in silver candelabra. He had just finished a letter to his wife, telling her to keep up her spirits and fear nothing; that in a few days the experiment would be over and everything restored to its former condition, shortly after which she would be the wife of a man who would soon be able to buy up all the other millionaires in the world.

As he put the letter into the envelope there was a knock at the door, and Professor Kenyon was announced. Culvert greeted him stiffly and coldly, for he more than half guessed the errand he had come on. There had been two or three heated discussions between them of late, and Culvert knew before the Professor opened his lips that he had come to tell him that he was about to fulfil a threat that he had made a few days before. And this the Professor did tell him in a few dry, quiet words.

"It's no use, Professor," he replied, " you know yourself that I am powerless, as powerless as you are. I have no means of communicating with Markovitch, and the work cannot be stopped until the appointed time."

"But you were warned, sir!" the Professor interrupted warmly. "You were warned, and when you saw the effects coining you might have stopped. I wish to goodness that I had had nothing to do with the infernal business, for infernal it really is. Who are you that you should usurp one of the functions of the Almighty, for it is nothing less than that? I have kept your criminal secret too long, and I will keep it no longer. You have made yourself the enemy of Society, and Society still has the power to deal with you- '

"My dear Professor, that's all nonsense, and you know it!" said Calvert, interrupting him with a contemptuous gesture: "If Society were to lock me up, it should do without electricity till I were free. If it hung one it would get none, except on Markoviteh's terms, which would be higher than mine. So you can tell your story whenever you please. Meanwhile you'll excuse me if I remind you that I am rather busy."

Just as the Professor was about to take his leave the door opened and a boy brought in an envelope deeply edged with black. Calvert turned white to the lips and his hand trembled as he took it and opened it. It was in his wife's handwriting, and was dated five days before, as most of the journey had to be made on horseback. He read it through with fixed, staring eyes, then he crushed it into his pocket and strode towards the telephone. He rang the bell furiously, and then he started back with an oath on his lips, remembering that he had made it useless. The sound of the bell brought a clerk into the room immediately.

"Get me a hansom at once! " he almost shouted, and the clerk vanished.

"What is the matter? Where are you going?" asked the Professor.

"Matter? Read that!" he said, thrusting the crumpled letter

into his hand. "My little girl is dead - dead of that accursed sickness

which, as you justly say, I have brought on the world, and my wife is

down with it, too, and may be dead by this time. That letter's five days

old. My God, what have I done? What can I do? I'd give fifty thousand

pounds to get a telegram to Markovitch. Curse him and his infernal

scheme! If she dies I'll go to Boothia Land and kill him! Hullo! What's

that? Lightning - by all that's holy - and thunder!"

"Matter? Read that!" he said, thrusting the crumpled letter

into his hand. "My little girl is dead - dead of that accursed sickness

which, as you justly say, I have brought on the world, and my wife is

down with it, too, and may be dead by this time. That letter's five days

old. My God, what have I done? What can I do? I'd give fifty thousand

pounds to get a telegram to Markovitch. Curse him and his infernal

scheme! If she dies I'll go to Boothia Land and kill him! Hullo! What's

that? Lightning - by all that's holy - and thunder!"

As he spoke such a flash of lightning as had never split the skies of London before flared in a huge ragged stream of flame across the zenith, and a roar of thunder such as London's ears had never heard shook every house in the vast city to its foundation. Another and another followed in rapid succession, and all through the night and well into the next day there raged, as it was afterwards found, almost all over the whole Northern hemisphere, such a thunderstorm as had never been known in the world before and never would be again.

With it, too, came hurricanes and cyclones and deluges of rain; and when, after raging for nearly twenty-four hours, it at length ceased convulsing the atmosphere and growled itself away into silence, the first fact that came out of the chaos and desolation that it had left behind it was that the normal electrical conditions of the world had been restored - after which mankind set itself to repair the damage done by the cataclysm and went about its business in the usual way.

The epidemic vanished instantly and Mrs. Calvert did not die. Nearly six months later a white-haired wreck of a man crawled into her husband's office and said feebly:

"Don't you know me, Mr. Calvert? I'm Markovitch, or what there is left of him."

"Good heavens, so you are!" said Calvert. "What has happened to you? Sit down and tell me all about it."

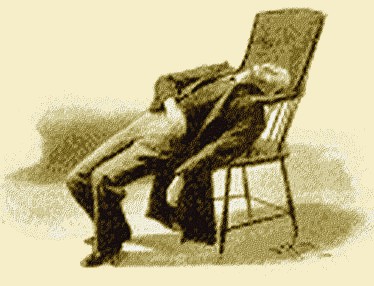

"It is not a long story," said Markovitch, sitting down and

beginning to speak in a thin, trembling voice. "It is not long, but it

is very bad. Everything went well at first. All succeeded as I said it

would and then, I think it was just four days before we should have

stopped, it happened."

"It is not a long story," said Markovitch, sitting down and

beginning to speak in a thin, trembling voice. "It is not long, but it

is very bad. Everything went well at first. All succeeded as I said it

would and then, I think it was just four days before we should have

stopped, it happened."

"What happened?"

"I don't know. We must have gone too far, or by some means an accidental discharge must have taken place. The whole works suddenly burst into white flame. Everything made of metal melted like tallow. Every man in the works died instantly, burnt, you know, to a cinder. I was four or five miles away, with some others, seal shooting. We were all struck down insensible. When I came to myself I found I was the only one alive. Yes, Mr. Culvert, I am the only man that has returned from Boothia alive. The works are gone. There are only some heaps of melted metal lying about on the ice. After that I don't know what happened. I must have gone mad. It was enough to make a man mad, you know. But some Indians and Eskimos, who used to trade with us, found me wandering about, so they told me, starving and out of my mind, and they took me to the coast. There I got better and then was picked up by a whaler and so I got home. That is all. It was very awful, wasn't it?"

Then his face fell forward into his trembling hands, and

Culvert saw the tears trickling between his fingers. Then he reeled

backward, and suddenly his body slipped gently out of the chair and on

to the floor. When Culvert tried to pick him up he was dead. And so the

secret of the Great Experiment, so far as the world at large was

concerned, never got beyond the walls of Mr. Sidney Culvert's cosy

dining-room after all.

Then his face fell forward into his trembling hands, and

Culvert saw the tears trickling between his fingers. Then he reeled

backward, and suddenly his body slipped gently out of the chair and on

to the floor. When Culvert tried to pick him up he was dead. And so the

secret of the Great Experiment, so far as the world at large was

concerned, never got beyond the walls of Mr. Sidney Culvert's cosy

dining-room after all.

THE END