RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

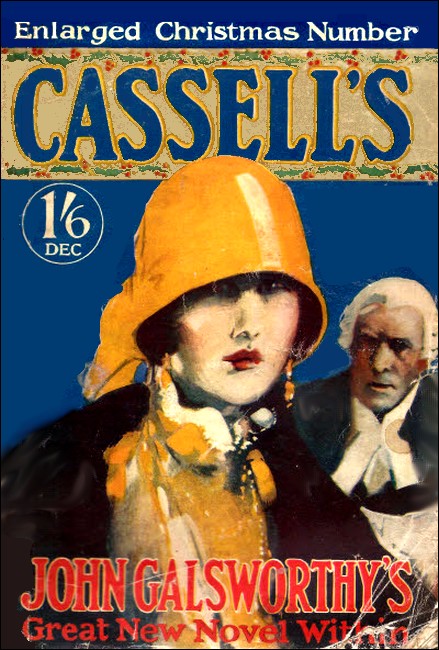

Cassells', December 1926, with "The Case of Colette"

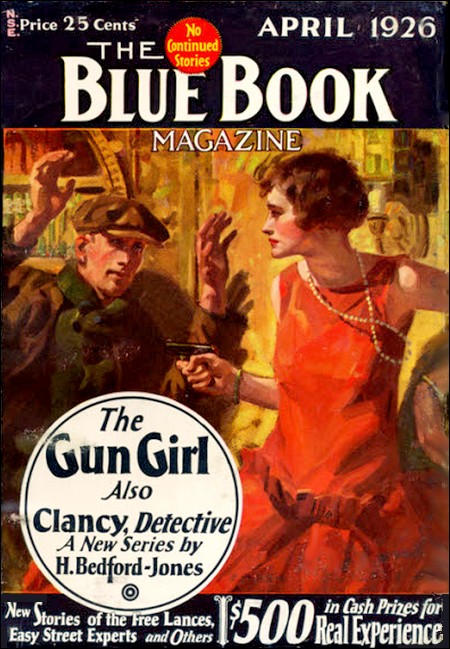

Blue Book, April 1926, with "Clancy, Detective"

HALF a second more, and the truck would have backed the little old man out of existence. It was one of those traffic jams for which Paris is famous, at the corner of the narrow Rue Caumartin. Caught between two lines of taxicabs, oblivious of the truck coming at him from behind, with everybody vociferously shouting at everybody else, the old chap stood bewildered and hesitant, or so I thought.

Consequently, I made a grab for him, rushed him under the nose of a taxi, and literally carried him to the sidewalk. There, to my surprise, he turned on me savagely with a flood of French.

"Save your breath," I said. "I don't savvy half what you say, anyhow—"

His face lighted up and he switched into English.

"American, are you? Well, what the purgatory do you mean by assaulting me that way?"

"Good Lord!" I exclaimed. "When a man saves your life, you jump on him! In another—"

"Oh, you make me tired!" he snapped. "You're another fool tourist who thinks this is America. Don't you know such things don't happen here? They have jams, but accidents are rare, and they never run over anyone except—"

"Suit yourself," I told him. "In another jiffy you'd have been the exception, that's all."

He laughed suddenly and put out his hand. "Thanks," he said. "I was thinking about something, to tell the truth. Perhaps you're right. Allow me—"

He extended a card. I read: "Peter J. Clancy, D.D.S.," and then heard the suggestion that we have a drink. I assented.

"Sorry I haven't a card, Doc," I said. "My finances haven't extended that far yet. I came over here to take a newspaper job, got done out of it, and am on my way to book steerage home again. Here's a cafe. My name's Jim Logan."

We strolled into the cafe and ordered a drink, and I took stock of Clancy.

He was a queer duck. He was small, about five foot five in his boots, and had long gray hair and a gray imperial. His clothes were black once, perhaps, but now they were greenish and frayed; he wore the red ribbon of the Legion in his buttonhole. His face was wrinkled—kindly, shrewd wrinkles, they were—and his eyes were very bright, of a piercing gray. He wore the wide- brimmed black felt hat of the Parisian, and looked as French as they make them.

"Glad to meet you, Logan," he said. "I've lived here fifteen years, and sometimes I get pretty homesick. So you're going back steerage, eh?"

"Anyway at all," I said, sipping my Rossi. "This is the land of liberty, all right, but what I need is a job and not liberty."

"Very well," he said, with a nod. "I'll give you a job—if you can tell me the difference between a Sydney View and a Saint Helena grilled."

FOR a moment he had me stumped, until I saw in his eyes

that he was earnest enough, and deadly serious. Then I laughed.

If this was a test, he had chosen it just right for me!

"The difference would be about a hundred dollars, if both were in good condition," I said. "Or, the difference between high value and worthlessness, as you prefer."

"Good!" he exclaimed. "Then you collect stamps?"

"I don't," I told him frankly. "But I used to. And I know a good deal about 'em. Do you?"

"Everybody in France does," he said. "Bless my soul, this is providential, Logan! Do you know, I'm really in need of you? Can you speak French?"

"Army French," I said. "I can understand it perfectly, but I'm no linguist."

"Better and better! And I perceive you're something of a boxer, from the way you handled your feet. You're powerful, you have a good brain, and you're not afraid to look at a dead man, or you'd not be in the newspaper game. I can use all these qualities."

"How?" I asked, rather amused, to tell the truth. "Pulling molars?"

"No." He glanced at his watch and paid for the drinks, with a careful French tip. "We've got time—just. Have you a pencil? Give me that card of mine."

I gave him card and pencil. He scribbled a few words in French and returned them to me.

"My office is at 33 Bis, Rue Cambon," he said. "Second floor, French style—you'd call it the third. You have some money?"

"Enough for my steerage passage home."

"Good. I needed a messenger—and I have him." He drew me out on the sidewalk as he spoke. "Take a taxi and go to the Préfecture of Police, the central bureau on the Île de la Cité. Ask for the préfet himself—show this card. It'll get you instant admittance. Tell him I want to take over the case of the stamp dealer Colette, who was murdered this morning in his shop in Rue St. Honoré, just around the corner. Tell him I'll go there at twelve-thirty and want him to have all arrangements made to put me in charge."

I took him by the arm.

"Listen, Doc," I said quietly. "This cat can jump three ways. Either you're crazy, you're trying to work a practical joke on a tourist, or else I'm in over my head. Which is it?"

He looked at me, and broke into a laugh.

"Oh! I forgot to explain, Logan. You see, I'm pretty well known at the Préfecture, but my connection must remain unknown to the public at large. I often take over interesting cases. This is most interesting—" "Are you a dentist or a detective?" I demanded.

"Both," he said. "And good either way, young man! I'll give you a hundred a month—not francs, but dollars—and all the rewards that happen along, to throw in with me."

"You're on," I said. "I'll take a chance once, anyhow, and if the préfet kicks me out, no harm done. I'll be back at your office by noon, if this is on the level; if not, I'll be back there before then." I hopped a passing taxi and went on my way.

TO be honest, it seemed to me that the little dentist was

probably just a bit cracked in the upper story. From what I had

seen of Paris, however, this was nothing extraordinary, as

anybody would know from walking down the street a few blocks. If,

by any accident, he could make good on his promises, I would get

on the inside of a few police jobs and this would mean the glad

hand to me at any newspaper office. I was risking nothing except

being kicked out at police headquarters, so it was a good

gamble.

As my taxi purred up the quay toward Notre Dame, however, and I thought things over, I grew less positive as to Clancy's mental disturbance. Those sharp gray eyes of his were very sane, very humorous, sparkling with vigor and acuity. It was much more likely that he was putting over a practical joke, and that I would find myself politely deposited outside the Préfecture with a gendarme for company.

"Well, I can risk that, too," I reflected. "Wonder if there was a murder in Rue St. Honoré this morning? Come to think of it, I did see quite a crowd down toward Castiglione. But that test question of his—there was a queer one!"

No mistake about it, either. Only for the odd chance that I knew something about stamp collection, about which all the French are crazy, Clancy would not have gone on with his line of talk. This went to show he was in earnest, and the whole affair left me up in the air and puzzled.

WE got to the Préfecture at last, and I passed the

sentries without difficulty. Having applied for a card of

identity after being tipped off how to do it easily, I knew how

much stock to take in the usual methods of reaching anybody in

Paris. Pull, influence and the back door were all invented by

Frenchmen.

I reached the offices of the prefect, and they were crowded. I beckoned the gendarme and gave him Clancy's card. It bore, in French fashion, a tiny miniature cross of the Legion of Honor after his name. With the card, I gave him a ten franc note.

"My business is important, and I'm in a hurry," I said.

He shrugged and disappeared through a doorway. In two minutes he was back again, holding the door open for me. Then I had an idea whether or not my friend Clancy was crazy.

I was ushered into an office, where the préfet sat behind his desk, talking with a man whom I recognized instantly from his pictures. He happened to be the Premier of France, the actual ruler of a nation whose president is a figurehead meant to preside over charity bazaars. I waited. The Premier rose, shook hands, and departed. The chief of police looked at me and then stood up for the usual handshake and polite phrases.

Summoning up my best French, which was perfectly understood by chauffeurs and the usual Parisian, but which made educated Frenchmen grin, I gave him Clancy's message. He fingered his flowing whiskers, and then nodded.

"Very well, it shall be as M. Clancy wishes," he said. "Tell him, however, that there is no mystery whatever in this case. Certain fingerprints were found, left by the murderer. They were investigated. The man who made them was arrested forty-five minutes ago. He cannot account for his whereabouts during the early hours of the morning, and M. Colette was murdered shortly after nine o'clock, upon his arrival to open the shop. The murderer had been hiding there. He is a common Apache with a bad record, Gersault by name."

"I'm surprised," I said.

"Most people are usually surprised by the efficiency of Paris police," he returned, beaming on me. I gave him a smile.

"No, it's the other way round, monsieur. I'm surprised that you should be so far behind the times as to place any dependence on fingerprints. It has been proved over and over in the American courts that they can be forged. There are different ways of transferring the fingerprints of an innocent man to the scene of a crime. The chief of police of Los Angeles was charged with a crime by a friend, who thus demonstrated the feasibility of transferring prints, for by all evidence the chief was guilty. The Australian courts have recognized these things and have dismissed—"

The préfet rubbed his whiskers the wrong way, in some agitation.

"We are aware of these things, my friend," he said hastily. "We are aware of them, I can assure you, and shall bring them all into consideration. In the meantime, you will honor me by informing M. Clancy that full details of the affair will be waiting for him at the scene of the crime, by twelve-thirty. I shall be very glad to place the case in his hands, and pending the result of his inquiry we shall do nothing, beyond keeping the man Gersault in prison."

He bowed, I bowed, and with the parting ceremonial handshake, I got away.

It was five minutes to twelve when I reached Clancy's address in Rue Cambon. It was an old barn of a place, gained through a courtyard, and his offices were old-fashioned and high-ceilinged. He had a patient in his dental chair, and nodded to me.

"I'll be free presently," he said, and there was a twinkle in his eye.

"So you didn't get kicked out?"

"No," I said, and let it go at that.

I HAD a look around the outer or waiting-room. Obviously,

the old chap had an eye for good furniture, and knew a rug when

he saw one; he had few of the gimcracks which crowd the usual

office of the French professional man.

At one side of the room was a big, glass-doored cabinet, standing open. An unmistakable loose-leaf album lay inside, and I could not resist the temptation to take it out and have a look. Then I saw half a dozen other albums below. Glancing over the book, I found that Clancy had a superb collection of Great Britain and colonies, largely in blocks of four. Then I put back the album, as he escorted his patient to the door, and turned to meet him.

"Isn't it rather injudicious to leave the cabinet open?" I asked.

"Nothing there worth your time or trouble," he answered. "Shut it, and come along inside. We'll have a chat, and get a bite to eat when the opportunity offers."

He must have left the cabinet open by forgetfulness, since it had a spring lock, opening only to some intricate key. He motioned me to the dental chair, and I declined promptly.

"Too reminiscent, thanks."

"Please yourself." He offered a cigarette. "Of course, our friend the préfet has caught the murderer by this time?"

"How did you know that?"

"It's the usual custom, unless the affair is something very simple or very big. Well, what happened?"

I told him, and he listened in silence until I had finished. Then those bright gray eyes of his flamed suddenly.

"So you didn't think it unusual that the Premier would be calling on the chief of police, eh?"

I whistled. Now that he mentioned it, the incident was unusual—in the ordinary course of nature, it would have been the other way round. I said so, and he nodded.

"Of course, of course. However, the préfet is unlike the majority of his countrymen. He is not a stamp collector. He collects something, of course—a Frenchman has to collect something—but he runs to coins."

"Old or new?" I queried facetiously. Clancy chuckled.

"Old. Hm! Our little murder case, except for the Premier calling on the prefect, would be simple robbery—"

"How do you know the call has anything to do with this case?" I demanded.

"I don't. I just make a guess, my good friend! But yes, it would be simple robbery."

He was silent for a moment, smoking thoughtfully, then he broke into explanation.

"Colette had a pair of the Niger Coast one-pound surcharge—of which only two copies were ever in existence. It is less known than the Mauritius 'post-office' stamp, but equally rare. The two stamps were overprinted together, and one was subsequently torn off and used. What became of it is unknown; neither the sender nor the recipient was a collector, apparently. The other one came into Colette's hands about six months ago. He has advertised it at the price of twenty-five thousand dollars, but has not yet sold it. Thus, an apparent motive for robbery."

"The police have arrested a man named Gersault, of the Apache class, on the strength of his fingerprints," I reminded him.

"And Gersault will probably confess," said Clancy. "We must look up everything and everyone connected with him, and lose valuable time—humph! Meanwhile, we'd better get along to the late and lamented Colette's place. When we have played our little parts to the satisfaction of M. le Préfet and his men, we'll begin the serious end of the business—humph!"

FOR the time being, he forgot me, and went into dreamy

abstraction. He reached down his black felt hat, put it on and

made for the door, stroking his gray imperial. I followed

him.

In two minutes we were in the Rue St. Honoré, and strode along till we reached the tiny shop of Colette. The steel shutters were pulled down, leaving the only entrance at the rear, by way of the courtyard. A gendarme stood there—not the usual agent, but the rarely seen gendarme, in all his glory—and he saluted Clancy at once. Clancy nodded recognition.

"Ah, the préfet sent you, eh?"

"To receive you, monsieur," said the gendarme. He took out a sheaf of papers and handed them to Clancy, who pocketed them impatiently. "The formalities have been finished, but everything has been left untouched for your inspection."

We went in, and he switched on the electric light. Narrow- fronted as it was, the shop was twenty feet deep. In the right- hand corner at the back, facing the rear entry, was a large safe. Anyone standing at the safe would be invisible, for the entire window and front door were closed in by cards of stamps offered for sale. Colette's body lay before the safe. "Stabbed?" demanded Clancy abruptly.

The gendarme, who apparently had charge of the case, nodded.

"Under the left arm, monsieur. The main artery, not the heart." "Where is the knife?"

"Not found, monsieur, but it was no knife. It was a long, stiletto-like blade, very thin. The doctor could only judge from the nature of the wound."

"Of course," said Clancy. He had an irritating way of saying the two words, as though everything was clear to him. After the two questions, he disregarded the body and turned his attention to the safe. "Gersault's fingerprints were found here?"

The gendarme nodded and showed us. The safe door was partly open, and Clancy took a magnifying glass from his pocket, pushing open the door. The shelves were filled with albums, small classeurs or pocketbooks for stamps, and loose sheets. Below these was a row of small drawers, one standing open and empty. Clancy pointed down at it.

"Gersault's fingerprints there, also?"

"Yes, monsieur," answered the gendarme. "And on the front door, also?"

"Yes, monsieur."

"How much money did Gersault have on him when arrested?"

"Two thousand-franc notes, six hundred-franc notes, two ten- franc notes, eighteen francs in bronze, two ten-centime copper pieces, and two five-centime nickel pieces," said the gendarme without hesitation. "Also, five Italian thousand-lire notes."

"Ah!" said Clancy in a curious tone. He turned and looked at me gravely. "Logan, never dare tell me these police are not efficient!"

HE went to the safe and peered into it, inquisitively. On

the upper shelf was a row of little books or carnets bound

in morocco. One projected slightly beyond its fellows, and it was

bound in red, instead of in black like the others. Clancy

suddenly reached up and pulled it from its place, and gave it a

quick examination. Then he sniffed.

"So that's it!" he exclaimed. "There'd be no prints, of course—gloved hands." He swept around and thrust it under my nose. "Know the smell?"

"Apple-blossom," I said promptly, wondering what he was driving at.

"Hm! They're so used to scenting themselves—" He broke off, and handled the little carnet almost reverently. "He kept his rarities in this. A true collector, Colette! Now, Logan, we'll see! Everything neat, immaculate, in the best French manner—except this little book of rarities! It's obvious. Everything's obvious!"

I watched him go through the little book page by page, entirely disregarding the two of us. Here and there he lifted a specimen carefully to inspect its back. There were things in this booklet to make my fingers itch; the rare first printings of Newfoundland, French and English colonials, early Mauritius—all with prices penciled beneath, of from one to ten thousand francs, even more.

Clancy turned page after page. About two thirds of the way through, he came to a page on which was a ruled oblong in the center, but no stamp. Below the oblong was this inscription:

No. 37, Gibbons—10s., in black, one is.—$25,000

The price of twenty-five thousand dollars, in dollars, showed that Colette had hoped to sell the vanished stamp to some American tourist or dealer. One might have equally set a value on the unique Guiana rarity, on the Venus de Milo, or any other treasure of which only one specimen exists. And Clancy examined this blank page very carefully with his magnifying glass, and then held it under my nose.

"Gloves save prints," he observed grimly, "but they carry scent."

Apple-blossom again. The gendarme, who spoke English fluently, smiled. "M. Clancy has found something?"

"What I sought is not here," said Clancy evasively, then his tone became sharper. "I have finished, m'sieur. If you question Gersault, you'll find that he'll confess to theft from this safe- -"

"He has confessed, monsieur," said the gendarme. "A copy is in the dossier I gave you."

"Good," said Clancy. "Take a look at the body, Logan. The rest is a matter for the nose—the trained, inquisitive nose—and for plodding research."

I looked at the dead man. A small, swarthy, fat little chap, he had been one who dressed carefully for his business, with morning coat, starched front and cuffs—even a rosebud in his buttonhole. The left arm was stretched out away from the body. Under it, the coat had been pulled away, vest and underwear cut to permit examination of the wound. From the man's immaculate appearance, I concluded he had been caught unawares. Whoever had looked at the wound had probably done the slight disarrangement visible—or so I thought.

"Come along, Logan," said Clancy.

WE said farewell to the gendarme, and went out to the

street. Clancy led the way, more or less in one of his absent-

minded dreams, and I tagged along toward the Madeleine. At the

Trois Quartiers corner, he halted suddenly.

"How much money have you, Logan?"

"All of it," I responded. "A couple of thousand francs."

"You may need to use some of it. I expect you to work—no Watson business for you, my friend! I'm depending on you for a good deal. To follow your nose, for one thing—would you know that smell again?"

"Anywhere," I answered readily. "It was faint, but remarkable. Quite unlike the ordinary perfume, I imagine."

He nodded approvingly, then gave me a sample of his surprising general knowledge.

"It's used very seldom—is made by an English firm, oddly enough. They put it on the market some fifteen years ago and at first it swept things. Then the demand died out, for this apple- blossom had no lasting qualities. It could not be fixed, like ordinary perfume, but died out and was gone. Women wouldn't use it, despite its rare flavor, for this reason. There are others like it, of course, but none with its peculiar bouquet. Think you'd be misled?"

"No," I said, with conviction. One could not easily be misled there.

"One thing will help you—whoever uses it, must use it heavily, owing to its evanescent quality. Colette was murdered this morning. Whoever did it, used this perfume at home, put on gloves, came straight to Colette's place and killed him, then got the stamp. Perhaps took off the gloves to pull the stamp loose and pocket it—well, no matter! You must follow your nose."

"To find who uses this perfume—in Paris?" I laughed skeptically. "It's a large order."

"You're not Watson—I hope," came the biting response. Then Clancy smiled and put his hand on my shoulder. "Go to it! The stuff is imported from England and very few people use it nowadays; that's all the help I can give you. You're new to this game?"

I shrugged. "I'm a newspaper man."

"There are as big fools in that game as in others," he said calmly. "You know enough, then, to neglect no customer who buys that scent. And remember the sort of weapon used! I must interview Gersault and one or two others. We'll meet around the dental chair at eight this evening—eh? If not before."

"Right," I said.

BACK in my youthful days, I once had a girl who liked

apple-blossom perfume, and I bought her so much of it, and she

used it so freely, that I became sick of the odor for life. The

usual odor, that is. This one particular brand was different, a

sweet and freshly invigorating smell that took one straight back

to an apple orchard.

I left Clancy on the corner and ducked down to Prunier's for a bite to eat. Not the grand joint where tourists get bled, but the little one where you sit at the counter and pay French prices. And, as I crossed the street intersection, apple-blossom struck at me from a gorgeous limousine—the same rare scent. It's odd how you neglect the existence of a thing until the need comes for finding it, and then you meet it from every angle!

It was a big car. I was dodging through the traffic, and could only tell from the back wheel hubs that it was of Italian make. When I reached safety and turned to look, the limousine had swept away and gone in the tide of traffic. I had to give it up and run along to get my sandwich and demi of bock. There was no particular haste, for despite the apparent magnitude of my task, I could do little until the noon hour was past and the shops opened up at two.

A little reasoning over my lunch showed me that one who used apple-blossom and knew Colette's, must be in the habit of shopping in the Rue St. Honoré neighborhood among the solemn tourists with their long purses and omnipresent canes. So I set forth to dip into the perfume shops, even unto the Rue de Rivoli, but none of them yielded anything beyond the modern variant of my apple-blossom—a sweeter, more enduring, sickish smell. The one I wanted could not be fixed in its alcohol base, so was not popular; but while it lasted, it was like a breath of orchard with children playing in it.

I thought of an English druggist, and looked one up. Here I struck oil. He found a wholesaler's list which gave the address of the Paris importers of this stuff, he gave me a card and his blessing, and I sallied forth on sounder premises.

This trail took me to a third-floor office near the Porte de St. Denis, where the druggist's card made things easy for me. A very efficient girl clerk looked up the four shops in Paris where this perfume was sold and wrote down the addresses—four places in all Paris! Which shows how one cannot see the trees for the forest. One of those shops, and the likeliest, was in the Rue de Rivoli, not far from Rumpelmayer's, and had been almost under my nose!

This shop drew me first. I found a stodgy, middle-aged man who regarded my inquiries with distinct suspicion until, French fashion, I reached his interest by telling my personal affairs, or seeming to. When my hints made him understand that this was an affair of a secret passion and a beautiful incognita, he woke up.

He had two steady customers for my apple-blossom. One was the Baronne de la Seigny, at present in charge of a base hospital on the Moroccan front, where her husband held high command. She, obviously, was out of it. The other was a certain Madame de Lautenac, probably gone to her villa at Nice, but perhaps still in Paris. The address of this so charming madame—he hesitated doubtfully, but the fact of being in on the edge of a love affair shattered his commercial virtue. So did my hundred- franc note. I got the Lautenac address.

I DEPARTED for the other three establishments. In one I

was refused information point-blank: confidential hints effected

nothing, nor did the bank notes. I tried to buy two bottles of

the perfume, but they had only one. Back to the Porte St. Denis I

went, interviewed the wholesaler's clerk again, spent a little

money. The last order from this shop had been for three bottles,

twelve months previously. Obviously, they had no regular customer

for it. Time gone to waste!

One other shop, toward the Place de la République, was uncertain of its customers and afforded nothing. The fourth and last, near the Printemps, yielded gracefully to my persuasion. Four regular customers; Marquise d'Auteuil, a wealthy title bought under the Empire and of high society. A première danseuse at one of the Folies run for tourists. A lady, about whom the less said the better, just now sharing the establishment of a deposed potentate from the far east; and last—ah! A milliner in the Rue St. Honoré!

There came the difficulty; a flat-footed refusal to furnish names and addresses of the last three.

The hunt was over, I told myself, and went for the milliner's address. I bought her business name—Nicolette—for five hundred francs, and went my way rejoicing to see her.

I think Nicolette had a lot of fun with me. She was fat and fifty, if a day. When I asked to buy a hat and obviously knew nothing about millinery, she gave me pleasant ridicule. Neither she nor her assistant was perfumed. My idea of buying a hat without bringing a lady to try it on struck them as delicious. When I asked abruptly if there were any stamp dealers in the vicinity, they evidently thought me crazy.

"Ah! That poor M'sieur Colette was murdered this morning!" responded Nicolette. "So far as I know, there are no others nearer than the Rue Drouot. My husband, who was killed at Verdun, was a collectioneur, but I myself am not interested. Perhaps if you will bring madame, or mademoiselle, to choose her own hat—"

I got out of the place. In Paris, they suffer fools gladly.

The afternoon was wearily wasting along by this time. I went back to the English druggist to make sure of my premises. No, the English makers would supply only through the wholesale house; they were very strict about it as regarded the Paris trade. I had missed nobody.

I went to Fauchon's, which opened earlier than most, and dined by myself. The four shops selling my apple-blossom had not provided one decent clue among them. The première danseuse and the potentate's lady friend I had failed to locate, and Nicolette was ruled out. None of these was probably on the lookout for a Niger Coast one-pound surcharge at any price, even that of murder. There remained two very unlikely candidates— Madame de Lautenac, who seemed out of the city, and the Marquise d'Auteuil, member of very exclusive circles. I got an evening paper and read about the murder of Colette.

Nothing new there, except that he was really an Italian, whose original name had been Coletti.

IN something of a bad humor, I entered Clancy's office at

eight o'clock. He was in the dental chair, with a packet of stamp

mounts scattered over the instrument tray, a loose-leaf album in

his lap, and the operating light blazing on him. He glanced up

but did not rise.

"This business started me off again," he said dreamily. "Niger Coast—mine is a fine set, too. The ten-shilling red surcharge on five pence, for example: I came across it ten years ago at the Hotel Drouot—" He closed the album and nodded happily.

"I've tracked down the apple-blossom," I said abruptly.

"With no result, eh?"

"How do you know that?"

"By your face. How much did you expend?"

I told him. He brought out a wad of notes and refunded my expenditures, and I gave him an exact account of all I had done. He stroked his goatee and nodded.

"You did well. Hm! The première danseuse can be ruled out—she would not be up before noon, and those ladies are hard-working. They do not go around sticking knives into shopkeepers. About Madame de Lautenac, I know nothing; it will be easy to find whether she has gone to Nice. However, I am attracted by the two remaining possibilities; the Marquise, and the pretty favorite of the eastern potentate. She must be Lottie Harfleur—of course!"

He got out of his chair and went to the shelves on the wall. He took down first one and then another volume of "Le Bottin"— the voluminous directory that will give you all France and its people, if you know how to use the thing. Then he gave me a cigarette and lighted another at my match, and smoked thoughtfully.

"There's a stamp auction tomorrow at the Drouot," he observed dreamily. "Another of those sweet little games managed by the dealers for their own benefit. Everything in Paris touches the Hotel Drouot at some point; draft horses and Greek statuary, all come to the auction block there—they sold Marie Antoinette's nightcap the other day. I'd be tempted to look there, except—the Premier visiting the préfet of police—"

"Politics?" I asked hopefully. Clancy smiled.

"Why not? This Colette was an Italian, yet in Paris you can never tell who anybody is in reality. He may have been a secret agent for some foreign government—anything! Yet, his murderer took a stamp of priceless value, a Niger Coast stamp also, a colony in which few collectors here are interested—"

He tossed his cigarette to the floor, French fashion, and stepped on it, then looked at me. "Do you know any newspaper men here?"

"One or two," I said.

"Good. Find out all you can about the private life of the Marquise d'Auteuil. Leave the others to me. Follow your nose. To tell the exact truth," and he smiled in his whimsical, kindly fashion, "you and I are both up a stump, young man! I want more information and I mean to have it—from somewhere. There's something to this I don't know."

"Obviously," I said with heavy wit. He chuckled and slapped my shoulder.

"Right! We'll get it tomorrow. Follow your nose—follow your nose! Eight tomorrow night at the dental chair, if not before. And here's luck to you!"

I went back to my lodgings, feeling that my first essay as a detective was not up to storybook style, by a long shot.

With Phil Brady, who does a weekly column for New York and syndicate papers, and who knows everything and everybody in Paris, I had a nodding acquaintance. Like most of the top-notch correspondents, Brady has the Legion of Honor. I reached him by telephone, and next morning he met me at a corner terrace table outside the Café Madrid. He was large, comfortable and middle- aged, had married a Frenchwoman, and was universally liked.

"Spill it," said Brady, when we had ordered a café fine. "What d'you want?"

"The Marquise d'Auteuil," I said.

"Expensive," grunted Brady, "but get her if you want her—not with my help. Run your own tourist agency. I thought this was serious business."

"Confound you!" I exclaimed. "I didn't mean what you mean. I've got a line on something in this Colette murder affair, if you've heard of it, and this dame is one of the exhibits."

"Oh!" Brady grinned. "Exclusive story to me when it's ready for release."

"Agreed. If I'm on the right track we'll both win."

"Who you working with or for?"

"A chap named Clancy."

He gave me a queer look. "Oh! You're a lucky devil. What do you want?"

"The lady's life history. Perhaps an introduction."

HE grunted. "You don't want much. Meet me at the Gallos

Café, back of the Louvre store, at one-thirty. Best place to eat

in the city and not a confounded tourist to be seen. I don't

carry life histories in my head, but I'll have the dope for you

then. Order a bottle of their Vouvray '06 but go light on

it— strong stuff. What's back of this Colette murder?"

"Search me, so far. Know anything? Politics?"

He sniffed. "I know your friend Clancy—he doesn't fool away time on nothing. If it's politics, it may reach anywhere. Well, see you for lunch, then."

His opinion of my new employer was extremely reassuring, but I wondered whether Clancy had not side-tracked me. It did not seem probable that a marquise would have committed the murder, though I did not have any high opinion of Continental nobility. Clancy's half-formed notions about the Hotel Drouot, however, struck me as more to the point. This huge building of lofty halls, center of all the auctions in Paris, was a remarkable institution. Here were sold estates, goods seized for taxes, government confiscations, collections of books, stamps, coins, everything! Few tourists ever reached it: the place was haunted every afternoon by all the antique dealers in Paris, by collectors of every walk in life, by society women and hotel-keepers. Something might show up in line with my quest at this afternoon's sale, and I determined to drop around.

AT the time and place appointed, I met Brady again. He

brought three different portraits of the Marquise d'Auteuil, two

being studio views and the third a snap taken at Longchamps. This

gave her as tall and willowy, wearing the last thing in summer

frocks, with a feather boa about her swan-like neck—the

odious phrase fitted her exactly. The portraits showed her

classic features as cold and proud, somewhere in the early

thirties, and I did not care for her looks a bit.

"And what about her?" I demanded.

"Convent educated," said Brady. "Daughter of Armand de Chevrier, of the old noblesse. Married Auteuil at nineteen, when he was forty. They have a big place in Auteuil, another at Cannes, another in Normandy, but have let the chateaux—money is rather tight with them just at present. Neither she nor her husband are up to snuff. He has his actresses, she has her lovers, to put it baldly. Just now, Jean Galtier is the favorite of the fair dame. That's about all the general information I can pick up, and blessed if I can see where it would lead to the Colette affair." I agreed with him. "Who's this Jean Galtier?"

"Average man about town," replied Brady. "If you golf, I can get you in with him—if he's any use to you. He has money and time to spend, that's all; a languid devil, despite his passion for golf."

"Does he collect stamps?"

"You can search me." Brady shook his head and attacked his Chateaubriand. "However, I have something useful for you. There's a big political reception in the Avenue Kléber tonight, with some of the press invited—you can take my card and go if you like. Galtier will be there; he has stock in a newspaper, which means politics. The Marquise may be there. Georges Lebrun is the general master of ceremonies. Tell him I sent you, and he can manage an introduction to the lady—if you want it."

I pocketed the pasteboards he handed me. "And the Marquis?"

"If he's not at the reception, you'll find her there, and vice versa," said Brady with a touch of cynical amusement. "He patronizes Montmartre, however, rather than social affairs."

"And this Georges Lebrun?"

"You can't miss him. Just five feet, rosette of the Legion, beautiful black hair with a white patch over the left brow. He's very proud of it. Mention my name and he'll do anything in reason for you. I've a few further details, if they're any use."

He had—many of them, and I wondered how he had got hold of them. An expensive lady was the Marquise. He had a list of her debts, her habits, and her companions; and before our luncheon was finished I had a worse opinion of my fellow man than previously. It was a scandalously intimate story, once Brady was fairly launched.

"She doesn't look it," I observed.

"Hm! Does any woman ever look it? Though at the back of my mind I think you're barking up the wrong tree, and Gersault will go to the guillotine for the murder. Why should a marquise murder a stamp-dealer?" "I never said she did," I returned.

"Well, get the yarn, old man, and then spill it to me." I promised and we separated.

SINCE it was now past two, I made for the Hotel Drouot,

having nothing better on hand. I knew the place

slightly—knew it well enough not to seek my quarry on the

first floor, where only cheap things were sold. The upper floor

was devoted to collections and art sales, and for this I

struck.

Passing down the central hall, glancing at the huge rooms to either hand, I came to a pause. To my right was the sale—chairs and benches three deep around a green baize table the length of the room, with a scanty crowd standing behind. Before the table was the desk of the auctioneer and accountants. Commissaires displayed the lots, passing them around. To one side of the desk sat the expert, who looked as though he might possibly, as a baby, have suffered the indignity of a bath. He was handing out the lots.

I wormed my way along to a good spot and waited. British colonials were being sold. A scraggy old woman and a fat collector were pushing a first issue Nauru ten-shilling to fabulous prices. Dealers around me whispered; the woman had ten million stamps in her collection, the fat man was an industrial millionaire. Both were fools, said the dealers angrily.

The next lot came up, and I started at hearing its description. Niger Coast, ten-shilling surcharge on English five- penny! The catalog value of the stamp was fifteen hundred francs. No dealer would pay more than five or six hundred for it at the outside. The expert started the lot at fifty francs.

The old woman and Fatty pushed it up to a hundred at once, then others chipped in and it went to two hundred. "Two-fifty," said the expert, with a magnificent air. This staggered the others: your Frenchman counts the centimes, let alone the francs! However, Fatty came back, and the old woman snapped into the bidding again, and they shoved it up to four hundred.

Then, close beside me, spoke out a cool, lazy drawl. "Five hundred!" I looked at the bidder. He was faultlessly attired and looked much out of place here. He had been tailored and hatted at the best establishments; was young, fairly good-looking, and like four out of five French people, ran to nose.

The old woman glared; Fatty looked stupefied. The expert barked: "Cinquante!" in a savage tone, as though to frighten off the exquisite. The latter waited until the ivory hammer rose, then spoke again. "Six hundred."

The expert shoved a dirty hand in the air, as though to say that the fool could take the lot for all of him. Fatty examined the stamp, and nodded a bid. The old woman fought him up to seven hundred. Again the ivory hammer rose, and again the fashion-plate near me spoke.

"Seven-fifty."

One could see the old woman committing murder in her mind. "Soixante!" she snapped, and Fatty stuck with her. Youth and beauty let them contest it up to nine hundred, then came in with a flat bid of a thousand. All eyes went to him. Fatty pulled at his collar apoplectically and shook his head. The old woman snapped a raise of ten francs, and the exquisite went to eleven hundred. That was killing. The hammer fell, and the commissaire handed him the stamp.

"Name and address, monsieur, if you please." "Levallois, twenty Avenue Wagram."

HE paid, took his change, and then he sauntered out

carelessly. I watched one or two more lots go, but lost interest.

I departed, sought the chauffeurs' rendezvous near the end of the

Passage Jouffroy, and ordered a demi of brune.

Levallois! It was a keen letdown to me. Here was a Frenchman sufficiently interested in Niger Coast stamps to pay eleven hundred francs—much more than actual value—for one. I had confidently expected to hear him give the name of Galtier. It was a stamp of the same set as that for which Colette had been murdered, and the man had obviously attended the sale in order to buy this one stamp and no others. My disappointment, then, was acute. My notion of connecting Marquise d'Auteuil with the crime, through him, had suffered a setback. If this had only been Galtier, I would have been convinced.

I went along to my lodgings, across the river, and got into my glad rags. By the time I got out and dined—the usual restaurant does not serve until seven—it was nearly eight, and I went on to Clancy's apartment-office. I found him working over some dental instruments.

"Going gay, are you?" he exclaimed. For response, I handed him the card of invitation Brady had given me.

"Nine o'clock—that means nine-thirty," he commented. "On the trail of the Marquise, eh? You've begun, but not finished, a good day's work." "Then you think—"

Clancy shook his head. "I don't. It's fatal, in this game. I had an interesting talk with Gersault." "Then you learned something?"

"No. The type of man, not the talk, was interesting. Not a sound tooth in his head, and knows a dozen places to get absinthe by asking for Rossi-Vermouth."

"Sounds rather silly."

"All life is silly," said Clancy, and gave me a cigarette. "Why do any of us ever do anything? Crackling of thorns under a pot, as the preacher said a long time ago. Why did Colette deal in little bits of paper? Silly. Sillier still to have any thousand-lire notes in his safe. Sillier still of Gersault to take them. Why did the Premier call on the préfet of police?"

"I'll bite," I said. "Why? What are you hinting at?"

"Politics," and Clancy chuckled. "Come, give an account of yourself." I did so.

"Interesting," he commented. "This Levallois is a friend of Galtier. You'll see him there tonight. I'm half tempted to be there myself—hm! Of course. By the way, Madame de Lautenac is in town. She moves in the same set. Well, run along! See you tomorrow if I'm not there tonight."

I ran along, feeling rather disgusted with my new profession.

THE reception at a big mansion in the Avenue Kléber, being

political, was a full-dress affair, "le smoking" being held to

its strictly masculine place by fashionable Paris. My poor glad

rags looked nothing at all amid the uniforms, for your Frenchman

runs to decoration and medals in quantity, and is happy as a

child when wearing high colors.

Lebrun was not hard to locate. He was almost a dwarf in size, but his pride made up for lack of inches. When I presented Brady's card, he shook hands warmly and spoke in English of a sort.

Yes, any friend of M'sieur Brady might rest assured of his services. Of course, I would want to know who was who. He began pointing out couples, lingering with appreciation upon their titles, and then going into a cynical chronicle of their doings. It was amusing, but in the midst of his discourse I caught a passing breath of apple-blossom.

To trace it was impossible. Everyone was perfumed insufferably, new arrivals were coming in every moment, and I gave it up. Then Lebrun interrupted some highly spiced tale to indicate a man just entering.

"There is Galtier, Jean Galtier."

I caught at the name. "The stamp collector?" Lebrun shrugged. "Why not? Everyone collects stamps—perhaps Galtier does."

Pale-haired, chalky of face, indeterminate, thin-lipped, a man of perhaps thirty-five, Galtier looked no man to be the lover of a fashionable beauty. I understood that these women reduced their lovers to a platonic state, however, making them fetch and carry more like dogs than men. For such a part, it struck me, this Galtier would be an ideal subject. "What does he do?" I asked.

"What would you do, if you could spend a thousand francs before breakfast and not miss it?"

"Probably what he does," I said, and laughed.

"You would find him interesting," said Lebrun.

The spacious, ornately decorated salon, with its shifting groups, was well filled. For the moment Lebrun left me, to speak with some friends. Galtier came toward me, looking around as though in search of someone, until he was within three feet of me. Then he spoke suddenly as someone tapped him on the shoulder. That someone was Levallois. "Ah, my dear friend! I was looking for you—"

"And," said Levallois, laughingly, "your dear friend will undertake no more such commissions! It was very amusing, but a filthy place, filthy people—bah!"

"You got it?" demanded Galtier.

Levallois nodded. "Eleven hundred francs, and the tax besides- -"

"Spare me the details," said Galtier. "You did not bring it? Then, in the morning."

"Yes. An excellent copy, too. You now have the set complete?"

Galtier shook his head mournfully. "Nobody will ever complete it," he replied. "There are two I can never hope to see, at any price."

OBVIOUSLY, Levallois had been buying the stamp at that

sale for his friend. Good! My hopes rose. I knew, too, that even

if Galtier possessed the stamp stolen from Colette, his statement

would still be correct, for three of those stamps are extremely

rare. Of two, only two copies were printed, and five copies of

the third, making them easily among the rarest stamps in the

world.

Did Galtier hope to get one of the five copies, or did he already have Colette's stamp? His words gave no clue, yet his manner showed that the hobby was an absorbing one to him. I was now convinced that my time had not been wholly wasted. Somehow, Galtier would prove to be connected with the murder in the Rue St. Honoré.

Again, suddenly, the tang of apple-blossom drew my gaze swiftly around. Now I saw the Marquise, recognizing her instantly. She was approaching Galtier, and Levallois turned away. Galtier bowed over her hand, and my eyes went to the diamond-studded object on her corsage—a tiny stiletto, an ancient bit of gold-work. Its hilt would have meant a year's income to me. Small as it was, it was large enough to let out a man's life.

The two talked together, low-voiced. Galtier seemed embarrassed, and I thought she must be reproaching him. I could build it up in my mind—despite Clancy's remark anent the folly of thinking. Galtier would never murder for the sake of a stamp, which he might buy, but here was a woman who would put her soul in pawn for the sake of the man she wanted.

Galtier had cooled toward her, then, and she wanted to keep him. She, not he, had gone to Colette's shop. Perhaps Colette had promised the stamp to someone else, and refused to sell it; perhaps she was unable to pay some extortionate demand. Perhaps she had tried to steal it, and had been detected—

No. Somehow, it wouldn't hold water, though it was very plausible. I could not see a woman like this one killing Colette, though she had both strength and courage for it. Then her voice lifted a little and reached me clearly.

"Tomorrow, then, before déjeuner. A surprise for you, my friend—"

So, then, it was settled! She had the stamp, and on the morrow would hand it over to him; such a gift would cement him firmly. She was safe enough, for the supposed murderer was already in custody and the stamp would not be traced—indeed, only Clancy had divined its loss.

THE two parted. Galtier stood alone, rubbing his forehead

and looking distinctly relieved at her departure. Exactly. He was

tired of the intrigue, and she was mad to get him back at her

beck and call. Meantime, I thought, watch Galtier and let her

alone. She had the stamp. The chief thing would be to call at her

house in the morning, and obtain it. Clancy must handle this end

of it, naturally. Galtier moved about the place, speaking,

shaking hands, kissing fingers. He still seemed searching.

Levallois had disappeared in the throng. I followed Galtier,

feeling awkward and conspicuous, yet exultant over my

success—

Apple-blossom again! Galtier swung around, and a sparkle of animation came into his face as he bowed above the hand of a very brunette, almost swarthy, young woman. Her lack of any jewelry was noticeable. So was the brilliance of her eyes, the extreme vigor and depth of her personality. She was beautiful, and she had character plus. Galtier retained her hand and beamed at her.

"It is good to see you again, mon ami!" she said. "You see, since you would not come to Cannes, I have come back to Paris!"

"But you did not tell me!" he ejaculated.

She laughed. "I waited for tonight. You are leaving?"

"I am due at the Opéra, to my sorrow, madame!"

"But that does not take the entire evening," she said, with a significant look. Galtier gave her an eager smile, and murmured something I could not hear. Undoubtedly, he was going to call on her later in the evening, whoever she was.

Knowing now that Galtier was bound for the Opéra and later for her, I felt it was no use hanging on his trail longer, and I might as well drift along. I obtained my things, and left the place, pausing at the entrance to light a cigarette.

Two men were standing outside, talking. One was a tall man in brilliant uniform—the minister of something, war or foreign affairs or state—and the other was very short and dressed up to the nines. Both had their backs to me. Suddenly the shorter man swung around, showing his decorations in all their glory—

"You might bring up a taxi for me, Logan," he said.

I was stupefied, then went on past and at the street hailed a taxi. Clancy here! Then something was up! I waited, standing in the porte-cochère to which the taxicab had come. A moment more, and Clancy appeared. He took my arm, and told the chauffeur to wait. "But, m'sieur," came a flunky protesting, "it is not allowed here—there will be other vehicles—" "The other vehicles," said Clancy dryly, "may go somewhere else."

The flunky waxed indignant. A gendarme, stationed outside the place, came up to us; he was the same who had come as messenger from the Préfecture. The flunky appealed to him hotly.

"But what has M. Clancy said?" asked the gendarme.

"That this species of a taxicab must stand here while others— "

"Then it must stand here," said the gendarme, and that was that.

Clancy drew me to one side, out of earshot, and lighted a cigarette. "We're waiting for a lady," he said.

"I know," I told him. "I've got the whole thing clear enough now—"

HE smoked silently while I outlined the case, but made no

comment until I was through. Then he chuckled.

"Suppose you listen to me—I've been busy. First, Gersault told me a queer yarn. He passed the door of Colette's shop, saw it open, saw a woman come out. He had a back view of her only. Then, glancing into the shop, he saw a pair of feet—and knew something was up. He was sharp enough to slip in. An open safe, a dead or dying man—why resist? He went for the cash, got it, and slipped out and away. He left fingerprints, however."

"And the woman was the marquise?"

"It was not," said Clancy, and laughed at my disconcerted expression. "The description doesn't fit her—she's tall, above the average. Well, you ran down the apple-blossom, and I ran down the narrowed trail. All the time, I was wondering about Colette being an Italian, and the thousand-lire notes Gersault had grabbed with the rest. There was one lady unaccounted for, your Madame de Lautenac, presumably gone to the Riviera. I found she had gone last week."

"So she's out of it too, then?"

"Not at all. She returned to Paris the night before Colette was killed. So I looked her up—yes, my friend, I've been a busy man today! She has an apartment in the Avenue Friedland, not far from here; she is presumably a widow, but little is known about her. I had a chat with her concierge this afternoon."

Significant enough. To every apartment-block a concierge—a registered person, too, who must be responsible, who must be known to the police as of good character. Male or female, a concierge in Paris does not get the place easily. He knows every detail in the life of his tenants.

"Two minutes after you left me this evening," went on Clancy, "the concierge telephoned me that Madame de Lautenac was departing shortly to this reception. Also, her bonne à tout faire had departed, and her maid was leaving for the night. So I dressed and went to her place—and searched it. I had some luck, but there are many points I do not understand, so we must wait for her to explain them."

I was bursting with questions, but just then came out to us the same dignitary who had been talking with Clancy on the steps. The gendarme, at one side, saluted him impressively. He glanced at me, and then spoke to Clancy, with an anxious air.

"You did not say, monsieur, when you would let me know—"

"M. le Ministre is going to the Opéra, I think?" said Clancy reflectively.

"But yes. We are very late now—but it is Faust, which matters nothing until the ballet at the end—"

"Very well," said Clancy. "When the ballet begins, monsieur, I will come to your loge, with the treaty."

The minister started. "You—you are certain?"

"I have promised, monsieur," said Clancy. He enjoyed being theatrical, and laughed softly to himself when the minister departed.

"The treaty?" I demanded. "Clancy, what in the devil's name are you driving at?"

He touched my arm. "You'll learn presently—there she comes, now! Madame de Lautenac, poor woman! Come along."

I stared. The woman descending the short steps toward us, ordering her car brought up, ordering our taxi out of the way, was the brunette with whom Galtier had made an appointment. Madame de Lautenac! And she was unescorted.

MY friend removed his hat and bowed. "Madame, I have a

taxicab awaiting you," he said pleasantly.

She looked at him, with a puzzled frown. "You mistake, monsieur."

"Not at all, madame," returned Clancy. "If you will honor us, we will escort you home in our taxicab, instead of in your car. Unless, of course, madame would prefer going direct to the Préfecture with a gendarme."

Possibly a newspaper man sees more singular things than most people, because he is looking for them. However, never have I seen anything more swift and shocking than the change in Madame de Lautenac. One moment proudly beautiful, the next she was shrinking in stark terror.

Clancy offered his arm, and mechanically she accepted. The three of us went to the taxicab, and Clancy directed the driver. None of us spoke a word on the way, and when the short drive was ended, Clancy ordered the chauffeur to wait and the three of us went into the elevator and up to her floor.

There, before her door, she paused and turned on us as though to resist or protest. She lost her nerve again, and produced a key.

"Allow me, madame," said Clancy, and opened the door. "Into the small salon, madame."

We followed her inside. She seemed dazed, hopeless, as she led us into a very beautifully fitted salon. Then, throwing aside her wrap, she faced us with returning composure and a hint of defiance.

"What does this mean—"

"It means we had better sit down, if madame will permit," said Clancy. When she met his gaze, terror flickered again in her eyes. She seated herself abruptly.

"What I would like most to know," said Clancy reflectively, as though we were engaged in a light conversation over the coffee cups, "is the connection between Madame de Lautenac and the stamp dealer Colette. I refer, of course, to the antecedent connection."

"I never heard of such a man," said the woman coldly, her self-possession returning.

"No?" said Clancy softly. He looked at me and smiled, and spoke in English. "Did you notice that Colette's inside coat pocket had the lining pulled out?"

"Perhaps it had," I said. "It had been disarranged by the surgeon, no doubt."

"No, not by the surgeon." Clancy nodded and reverted to French. The woman's eyes showed me she had understood every word perfectly. "I suppose, madame, it is useless to ask for the document you took from Colette's pocket after you stabbed him?"

HER pale face became yet paler, but her composure was

perfect. Even her fingers, which had been nervously playing with

a handkerchief in her lap, became still.

"I know nothing of what you refer to," she said calmly, her eyes fastened on Clancy.

He nodded and turned to me.

"Will you be good enough to invert the Dresden china vase at the left of the mantel?"

I rose, went to the mantel, took the vase from it, and inverted it. Something heavy fell to the carpet, and I picked up one of those tiny miniature swords which can be found everywhere in Paris. This one was a rapier, perhaps six inches long, beautifully made and inlaid with gold. It might have served as a cabinet curio, as a hair ornament, or as anything. Halfway up the blade, toward the golden hilt, was a brownish stain.

"Now, perhaps," said Clancy quietly, to the woman, "you will tell me the antecedent connection between yourself and Colette?"

"He was my husband," she said, half whispering the words.

There was a moment of silence—a moment can be a long time. Only the ticking of the clock on the mantel disturbed us, and I saw the woman's eyes go to it with a sudden flash. She had remembered her appointment with Galtier—there was still hope!

"The document," said Clancy gravely, "is for the present immaterial. I wonder why you stopped to abstract a rare stamp from Colette's safe, madame? There was your mistake."

"It is nothing to you," she answered, calm again. A good antagonist, this woman! "I admit nothing. I know nothing."

"But," said Clancy inexorably, "you expect to give that stamp to Jean Galtier in an hour or less."

She sagged a little, and her steady gaze flickered. Clancy saw it, and drove home at once. "Perhaps you'd better give me the stamp, instead." "Very well," she said, to my surprise.

On the table lay a card-case. She reached out and took it, opened it, and extracted a tiny bit of paper. For a moment, it fell to me to see one of the world's rarest stamps. Clancy held out his hand to take it.

Instead, with a swift movement she shot it into her mouth and swallowed it.

CLANCY uttered an exclamation of dismay. So rapid was her

action, neither of us had a chance to stop it, and Cleopatra's

vinegar destroyed no greater value than this little meal. Madame

de Lautenac smiled slightly.

"I do not know what stamp you are talking about," she said calmly. "One cannot have committed a crime without evidence— "

Clancy recovered, and pointed to the little rapier, which I had laid on the table.

"The principal evidence, madame."

"Planted here by you, evidently during my absence."

Well shot. But Clancy only smiled.

"And then, madame, have we also planted the text of the Franco-Italian treaty, which you removed from Colette's pocket?"

In a moment, her defiant beauty became haggard, she became an old woman. The glitter of her eyes swept into a frightful despair. Somehow, Clancy had nailed her this time.

"How long is it since you left Colette?" demanded Clancy.

"Six years," she whispered. "Because—because he was a spy for Germany—in the war—"

"And you," said Clancy, pitiless, "take money from Moscow. Where is the difference? This treaty was signed three days ago in Paris. You were told at Cannes that Colette had it, for Germany. You were told to get it. You came and got it. Then—the stamp! Why the stamp?"

"For—for Jean," she whispered, her face terrible to see.

"And he will be here for his stamp presently," said Clancy. "Good. Then he, too, will become implicated in the murder—"

She half came to her feet.

"Stop, stop!" she cried out horribly. "He is innocent of it— he knows nothing of it—you must not drag him into it!" She thrust a hand into her low corsage and dragged out a paper packet, and flung it to the floor. "There is the treaty—take it, but do not bring Jean into it—spare him, spare him!"

She sank back, put her handkerchief to her face, and huddled down in her chair.

Clancy picked up the paper packet and broke it open. He nodded slightly, and put it in his pocket. Then he got out a cigarette and lighted it, and handed me one.

"Well, Logan," he said in English, "I think we'd better be getting along. We must not miss the ballet, you know. It wouldn't do to be late."

"But—"

I motioned toward the woman, who had not moved. Clancy sniffed slightly, and I started. In place of apple-blossom, a thin odor of bitter almonds was quivering on the air.

"A prussic-acid capsule in her handkerchief," said Clancy, with only a glance at her huddled, motionless figure. "No need to verify it. Shall we go?"

We went. Phil Brady did not get much of a story out of it, after all.