RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

RGL e-Book Cover 2019©

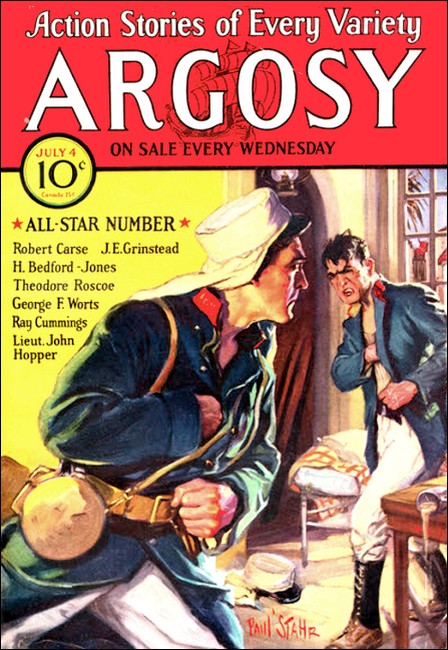

Argosy, 4 July 1931, with "House of Missing Men"

Vincent Connor wondered why a Russian countess should invite his friend to dinner in the French concession at Tientsin; and the answer was sudden and grim.

CONNOR was dressing for dinner, in his rooms at the Tientsin Club, when Vanessen barged in for a drink. Young Vanessen was a "griffin"—China coast equivalent of tenderfoot—in charge of the accounting for the Harris people; and Connor liked his frank boyishness and his Yale anecdotes. To-night, however, he observed that Vanessen, for all his exuberance of spirit, was a trifle uneasy beneath the surface.

"No wonder you're worried," he observed critically. "That dress tie of yours is a positive atrocity, Van, and those lapels are quite too wide. And do I smell Fleur de Nuit?"

Vanessen regarded the perfectly tailored figure of his host a bit wistfully.

"All very well for you, Connor," he said with good humor. "You inherited a mint of money, business interests extending over half China, and more or less good looks. All you have to do is sign checks, play polo, race your ponies, and let your tailor tell you the latest in London styles. Pretty soft, boy, pretty soft! Never mind my lapels. You wouldn't think about them if you knew where I was dining to-night."

"Yeah?" Connor lit a cigarette, glanced into the mirror and adjusted his waistcoat. "Bet your comprador is taking you to a Chinese dinner."

"Nix on that stuff!" Vanessen waved his hand with mock disdain. "She's a princess and a nifty blonde—get me? A real princess, too. Russian."

"Most of 'em are real," said Connor, unexcitedly. "Princesses in Russia are common as fleas in Spain, Van. Lot of Russian nobility in these parts; like fleas, too, they live off other people."

Vanessen flushed slightly.

"See here, Connor, I don't like the implication," he said. "Princess Orloff isn't any adventuress. Her crowd are not all angels, of course, but she's all right. Why, she's even in a bit of diplomatic work!"

Connor's fingers seemed to freeze against his tie-ends.

"Yes?" he said. "What sort? For what government?"

"Well, I'm not positive; she didn't say exactly. There were a couple of diplomats at her house last night, though—an Italian attaché and a British chap. She's on the level, Connor."

"Undoubtedly. Didn't mean to insinuate she wasn't, old chap," and Connor turned with a smile to pick up his drink and sip it. "Where does she live?"

"French concession, just off the Avenue Kléber. If you'd like to go around with me—"

"Sorry, I'm tied up to-night. Another time, by all means. By the way, Van, is anything bothering you? Must say you look a bit nervous."

"Bit of an eye strain from too much work, perhaps." Vanessen rose. "Well, thanks for the drink and the advice, old man. If I make a ten-strike one of these days I'll drop around and investigate your tailor; I must say his handiwork has always intrigued me. Night!"

ALONE, Connor lit a cigarette and sipped at his drink

reflectively. His wide-angled features with their odd blue eyes

and black hair were half frowning; he liked young Vanessen, and

was afraid the chap might be drifting in with the wrong crowd,

although he had never heard of any Princess Orloff.

This was not surprising, for Vincent Connor would of course know no one not in his own pleasure-loving set. As Vanessen had just said, he was rather an idler, with vast business connections inherited from his father, a faultless tailor, and no ambition in life except to dress perfectly, pass his time in vapid amusement or rapid sports, and avoid matrimonial entanglements. Such, at least, was the general idea of Vincent Connor as others saw him.

The few who really knew him, however—the few who knew to what ends he devoted his amazing knowledge of China, its language, its customs, its people—knew otherwise.

Turning to the telephone, Connor obtained his number and presently had his general manager on the wire.

"Mr. Connor speaking," he said, then lapsed into Mandarin, which he had spoken from boyhood. "Do you know anything about a Princess Orloff who has a place off the Avenue Kléber in the French concession?"

"I have heard the name, but know nothing of the person," came the reply.

"Then get me a report on her first thing in the morning, please," said Connor, and so dismissed the entire matter from his mind for that night.

HE was breakfasting the next morning when Winslow, of the

Times, entered the dining room of the club and came over

to his table.

"Morning, Connor. May I join you? Thanks. Beastly wet morning, eh? I've been out on a rotten story, too."

"That's no novelty in Tientsin," said Connor lazily. "Lady in the case?"

"Nope. Chap got in with some gambling house, apparently, went the works, shot himself. Rather decent young griffin, by all accounts. Left a note saying he'd gambled away everything he had—made a night of it, came back to his hotel, probably sent off a letter to his people, then plugged himself. Blast it all, I can't see why a chap wants to blow out his brains merely because he's flung his roll into the gutter!"

"Evidence of no brains to begin with," commented Connor. "Who was the chap? British?"

"No, American. Some dashed queer name—oh, yes! Vanessen."

Apparently, Connor was the only person to guess that Vanessen's suicide had anything to do with the Princess Orloff. And Connor, though he might guess a good deal, knew nothing.

Not all his sources could discover much about the nifty blonde. She had arrived in Tientsin a month previous, with a French passport, but coming from America; she had leased the villa off the Avenue Kléber for a year and had engaged French servants; she never went to the races, dances, or other diversions of the European colony. After two days of ceaseless effort, Connor was unable to find a person who knew her or who could so much as describe her.

On the third day he dropped his investigation.

"Vanessen was trapped," he told himself reflectively. "For some reason they wanted to use him—whoever 'they' may be! He was decoyed, fleeced, probably gave heavy I.O.U.'s; their idea was to get him in their power. Instead, he killed himself. Hm! They'd probably know me only too well—"

He summoned his general manager and instructed him to look after the Connor interests for the next fortnight or more.

"I'm catching the Hinyo Marti to-night for a month in Japan," he said. "See that the matter is not kept secret. Let everybody know it, in fact. Meantime, get me a berth on the night train for Peking."

AT Peking, a deserted city of the dead under its new name of

Peiping, Connor remained in seclusion for three days with his

Chinese branch agent there. Those three days effected a

tremendous change in Vincent Connor.

The fourth morning saw him dressed in none too trim hand-me- downs. A budding black mustache materially altered his features, as did the budding sideburns down past his ears. His healthy sunburned tan had been bleached out to a curious pallor which in itself would have rendered him unrecognizable. To complete his new identity he donned large glasses with black rims and faintly tinted lenses of plain glass, and faced his grinning agent.

"Does this humble slave seem like another person to his august maternal relative?" he asked in Mandarin.

The yellow man bowed.

"My unworthy eyes do not recognize the appearance of my honorable superior," he replied. "May I inquire his distinguished name and titles?"

"I," said Connor with a chuckle, "am John Forsythe, in the employ of the Laoyang Company at Tientsin."

Next morning, indeed, he took over a desk in the head office at Tientsin—the Laoyang Company being that branch of the Connor interests which dealt in timber. As befitted the chief clerk, he had a private office.

At five that afternoon Mr. Forsythe, carrying a cane and walking with a slight limp, came up the steps of the villa off the Avenue Kléber. To the French maid who opened the door he handed his card.

"I want to see the Princess Olga, or somebody," he said, to find that she knew no English. She hesitated, then admitted him and departed. Presently a sallow man in tweeds, with a distinct English accent, appeared holding his card and announced himself as secretary to the princess.

"The nature of your business, Mr. Forsythe?" he inquired coldly.

"Well, it's like this," said Forsythe. "I want to find out about a friend of mine named Vanessen, and I expect somebody here can tell me—"

"You are mistaken, sir," intervened the other. "There is no person here of that name, certainly."

"I know that," said Forsythe. "Listen, now, I just got here last night, see? I'm chief clerk with a lumber company—been down at Shanghai until now. I came out with Vanessen and we're friends. He wrote me last week about knowing this princess here and so forth, so when I got here and found out about his being dead, I thought maybe you folks could throw some light upon the whole business."

The secretary listened to all this with a somewhat agitated air, then drew out a chair.

"Will you sit down?" he said. "I do not know if the princess—Princess Orloff is the name—is at liberty, but I shall be glad to take her your card. Perhaps she may know more about your friend than I do."

Forsythe nodded, sat down, produced a cheap American cigarette and stared about the quietly handsome room.

"Hooked 'em!" he thought jubilantly. "And I ought to be just the man they want—though why they want some one remains to be seen. That secretary chap is no Englishman; he overdid the part. Looked like a Russian, rather."

A WOMAN swept into the room—blond, svelte, Paris-gowned,

touched with barbaric jewels. She was perhaps thirty, but looked

younger. When she put out her hand to Forsythe her whole manner

was appealing, friendly, luring. Her liquid dark eyes were belied

by thin and perhaps cruel lips, but one forgot these in her warm

cordiality; her features were piquant, impulsive, charming. Her

fluent English was tinged with a slight and delightful

accent.

"I am so happy to see you, Mr. Forsythe!" she exclaimed, taking a chair and motioning him to another close by. "Your poor friend spoke more than once of you—it was such a shock to us all! You see, we liked him very much indeed."

"He was a fine fellow," said Forsythe. "Are you the princess he wrote about?"

"But of course!" She laughed quickly. "Princess Orloff—but Olga to my friends. Have you been long in Tientsin?"

"Only a day. I came around here to see if I could find—"

She lifted her hand; swift pain clouded her brilliant eyes.

"Ah, of course! My friend, I can tell you little about him. I think he fell in with the wrong sort of people—one cannot be too careful in China, you know!"

"Yes, I know," said Forsythe grimly. "Did he say anything to you about gambling?"

"Yes; his last evening here," she replied gravely. "He left early—he was going to meet some friends and visit a gambling house in the Chinese City. We begged him to stay here, for we Russians are gamblers, you know, and we play among ourselves; but he insisted on leaving. And the next day he was dead. Ah, but it is terrible! If I had only known! A few thousand dollars might have saved his life."

The technique, Forsythe decided, was none too good, but interesting.

"Well," he said, rising, "I must get along; didn't realize how late it was. I'm mighty sorry to have bothered you, princess, and I'm glad that Van found such good friends here. You see, I want to write his folks about it, and they'll be tickled to know that he was running around with nobility."

"But you are not leaving, now?" she protested in surprise.

"I guess I'd better," and Forsythe smiled. "I'm at the hotel, and I've got to find me a room somewhere; I don't like hotels. Haven't even unpacked my clothes yet. If I—"

"Wait!" She lifted her hand. "You are free this evening—you will come here and dine at eight? We shall welcome you. Any friend of poor Vanessen is our friend! I want you to meet our little circle here. We live quietly, it is true, but I like Americans, me! You do not speak French?"

Forsythe grinned. "Nope, I'll have to learn French and Chinese, I expect, but there's lots of time for that before I grow old."

"Then you must let me give you French lessons!" she exclaimed with vivacity. "And I think we may be able to find room for you here, too, if you'd care to come. You know, this is a very large place, and a number of my friends live here; we Russians have little money, and we club together. Perhaps we can arrange it—"

SIX evenings later beheld Forsythe very differently

situated.

He sat in his upstairs room in the villa of the princess—a small but comfortable room—and awaited his caller, General Bougdanov, one of the little group of Russians domiciled here. He knew exactly what the call would bring forth, and smiled through his cigarette smoke.

"They're taking no chances of anything going wrong this time," he reflected complacently. "They've got me installed here. I'm about five thousand dollars to the bad, and everything's ready for the blow-off—whatever that may be. They must be in a hurry, too, the way they've worked it! They probably had worked along with Vanessen, grooming him for the job, and his suicide pretty near knocked them cold. Hm! Somebody's going to pay for that, too."

His eyes were bleak and grim as he thought about it. He knew now that Princess Orloff was merely a pretty bait, a secondary personage in this game of intrigue. The real bellwether of the pack was Bougdanov; and diplomacy, so-called, was somehow involved. Here at this house Forsythe had met one or two attachés of legations, a consul from Mukden, several sleek agents of the war lords, and the local branch manager of the Hongkong Commercial Bank; but nowhere had he been able to pick up any hint of what was in the wind.

Seven thirty. Dinner in half an hour—

Bougdanov knocked and entered. The old general was in resplendent uniform, white whiskers brushed back, features vigorous and rosy; years were nothing to his vitality. He bowed ceremoniously and accepted the chair offered by Forsythe.

"My friend," he said solemnly, in his excellent English, as he patted Forsythe paternally on the knee, "I like you. And you know the old man he will help you, eh? Now, look; I have taken up every I.O.U. which you have given."

Forsythe's amazement was very real. Bougdanov produced those chits, so liberally handed out by a willing victim, and rapidly totalled them up.

"Over five thousand of your American dollars, eh?" His little eyes twinkled. "That is a lot of money, my young friend! You cannot pay. It means disgrace, eh? It is bad business. You have played heavily, unwisely. Well, fear not! I shall help you."

He leaned back and produced cigarettes. Forsythe struck a match.

"It's mighty good of you, general," he said huskily. "No, I couldn't meet those chits. I've been frantic. Desperate! And now I owe you all the money, is that it?"

"That is it," said Bougdanov. "But there is a favor you can do me. You can help me, and I will tear up these chits, you understand?"

"You mean it?" cried Forsythe. "I'll do anything, general! Anything except steal the money—"

"Pouf!" Bougdanov waved his cigarette, laughed heartily. "You will have your little joke, yes? Well, in three days you can earn that five thousand dollars. Good pay, eh? And all by doing me a favor. Listen! The other day I have drink too much, you understand? I have talked about my friend from America. To-night we have two guests. They do not speak English, but they wish to behold my American millionaire friend. You will take his name, act his part. Money is nothing to you. Whatever I say, you will say yes. You comprehend?"

"Eh? Is that all?" exclaimed Forsythe eagerly. He seized the general's hand. "Say, you bet I will! What's the name you want me to take?"

"Bayer." Bougdanov beamed upon him. "Robert Bayer. So, it is settled! You will be down presently for dinner, yes? Good. I like you, young man."

HE departed. Forsythe ditched the Russian cigarette and lit

one of his own, thoughtfully.

Here was a clue, at least; but he could not see whither it led. The imposture appeared insensate and meaningless. Robert Bayer was the United States consul general at Mukden, with Manchuria and northern China under his eye.

Well, have to see later. A further clue might turn up with the two guests. So far, Mr. Forsythe had gleaned little through his knowledge of Chinese and French; when his friends talked among themselves they used Russian or German, both of which were closed books to him. So he eyed his evening clothes in the mirror with some distaste, pinched his tie into the right shape, and descended to dinner.

The guests were two stocky, peasant-faced Chinese in uniform; one a general, the other a colonel. With them was a third, a captain—a slim youngster who shook hands heartily with Forsythe and addressed him in slangy English. A Chinese from America, acting as interpreter for the other two. Forsythe saw now why only an American could have played this part.

The dinner was quietly brilliant. On the right of the princess were the three Chinese, on her left were Forsythe and Bougdanov. Two middle-aged Russian women, who said little or nothing, and the sallow secretary, whose name was Nieuhoff, completed the table. Presently Forsythe discovered that the Chinese had just arrived in Tientsin from the west.

"And how," queried Bougdanov, beaming upon the general, "is our good friend, General Fu?"

"He is well, and lives in hope," came the reply through the interpreter.

"All is arranged," said Bougdanov. "We shall discuss it later."

The dinner proceeded, and Forsythe had another clue. This Fu, of course, must be the great Fu Wei, defeated some months since, and who had given up dreams of conquest to become a student in a Buddhist monastery. In reality he was probably biding his time to make another descent upon his fellow war lords who had brought chaos and anarchy to all China.

With the liqueurs, the ladies left the room. Nieuhoff, whom Forsythe now suspected of being a partner with Bougdanov in the latter's entire scheme, dismissed the servants and closed the doors. The Chinese colonel spoke rapidly to the interpreter in his own tongue.

"Think you this foreign devil is the right man?"

"Undoubtedly," came the response. "He is certainly an American."

"Then handle the matter. Remember, no money is to be paid until we have the letter from the American President."

Bougdanov now turned to Forsythe, beamingly.

"My dear Bayer," he began, "you know the matter of which I spoke with you. Has it gained your approval or not?"

"Certainly it has," assented Forsythe, while the interpreter listened.

"And did you cable as I suggested?"

"Yes. I shall get a reply to-morrow or next day."

"Then you remain here? You will stop as our guest?"

Forsythe regarded him in obvious astonishment.

"What? Naturally I shall remain until this is settled! But as your guest—well, yes. I thank you, and shall be very glad of your hospitality."

Bougdanov was utterly delighted by Forsythe's words and air, which so thoroughly backed up his own game. The interpreter was putting the dialogue into Chinese. Bougdanov waited.

"And when," he asked, "do you think we may be sure of having an answer? It is necessary to arrange a meeting with these gentlemen, who, as you know, represent General Fu Wei."

Forsythe reflected. "Day after to-morrow, certainly."

So it was arranged. They rejoined the ladies, and business was taboo for the evening.

FORSYTHE left in the morning for his supposed work without

seeing Bougdanov again. He was still wholly in the dark regarding

the game that was being played; while he might have wired the

real Bayer at Mukden or communicated with the American consul

here, he dared make no false move. An item in the Times,

stating that Bayer was in Tientsin on consular business, puzzled

him, but he took for granted that it had been inspired by

Bougdanov.

Then, unexpectedly, everything broke at once.

It was four in the afternoon when Connor's manager hastily informed him that Bougdanov was outside. Connor cleared his desk hastily, donned his assumed spectacles, and a moment later looked up as the Russian entered. The old general was obviously excited.

"We can talk here, my friend?" he asked abruptly. "It is safe?"

Forsythe nodded and locked the door, then resumed his chair.

"Go ahead, general. What's on your mind?"

With an effort Bougdanov got himself under control.

"First," he said, "I must explain to you. Perhaps you know how important is the influence of America in China to-day? Well, General Fu Wei somehow came to believe that I might obtain for him the backing of America, if and when he returns to the stage of war. In fact, I am to receive a large sum in cash, a very large sum, if I obtain a letter from the American President and a statement from the consul general approving him and giving him recognition. Now do you comprehend?"

There it was in a nutshell—an astonishing, almost incredible scheme.

Forsythe nodded and lit a cigarette, hiding his impulse to laugh. A ridiculous thing, no doubt; yet it had cost the life of Vanessen already.

"I see," he replied. "I am to supply the letter or cable, and a statement; you get the money. Is that it?"

Bougdanov spread out his hands in a warning gesture.

"We are not dealing with fools, my friend!" he exclaimed. "Listen. Our plans have been made for a long time, but sometimes there are slips. For example, we must do the thing to-night, instead of to-morrow. I have already summoned our Chinese friends. To-night you will identify yourself to them; I shall then have everything ready for you—papers, letters, government records, everything! You will hand them a cablegram, make a statement which will be typed on the proper note paper; that is all. You comprehend?"

"And I make five thousand, eh?" said Forsythe, with a smile. "Excellent!"

The other rose, beaming. "Ah, young man, I like you! We dine simply, by ourselves; the Chinese do not arrive until nine. Before then, we shall make arrangements. You find the plan to your taste?" he added, a trifle anxiously. "You do not refuse?"

"Refuse? Do I look like a fool?" Forsythe broke into a laugh and went to the door, arm in arm with his visitor. "My dear general, it's a great little scheme! I only wish I'd thought of it in the first place!"

He ushered out the Russian, then hastened back to his desk and caught up the telephone. The words "note paper" had given him an idea. In three minutes he had the American consul in Tientsin on the line.

"Hello—Vincent Connor speaking," he said. "Oh, Japan? Sure, I started for there, but had to attend to some business. Keep it quiet, will you? I wanted to learn whether your consul general in Mukden is here—he is? No, I don't want to see him, merely wanted to tip him off that something underhand seems to be going on. Stopping at your house, eh? All right, thanks. I may run over and see him in the morning. Good-by."

He hung up, frowning. "So that's that—and hanged if I can see why old Bougdanov was so excited! We'll have a genuine surprise for him to-night, perhaps."

It did not occur to him that Bougdanov might have a surprise for him.

WHEN Forsythe got home to the villa he saw no one but the

French maid; the place seemed quite deserted.

He bathed leisurely, dressed with care, and under his arm-pit snuggled the small pistol in its shoulder-holster. By this time it was dark. The one window of his room opened above the villa's porte-cochère, and he had just switched off his lights, preparatory to descending, when he heard the strident hum of a car coming to a halt. He went to the window just in time to hear an altercation about a fare, and to see a taxicab drive away—a French Renault taxi, as the slope of the hood told him.

Something held him at his door—some vague restraint. He heard a subdued oath from the hall, and then the voice of Nieuhoff in rapid French.

"Into my room with him—safe enough there. You take charge of the portfolio."

A grunt in Bougdanov's voice made answer. Forsythe frowned. They were bringing some one; who, then? Perhaps one of their Russian friends was dead drunk. It had happened before this.

Presently Forsythe descended, found Princess Orloff in the library writing letters, and was not astonished at the lack of warmth in her manner. She had snared him, and her part was finished; indeed, he rather liked her coolness. He had already guessed that she was either the wife or mistress of Nieuhoff.

Bougdanov appeared, dressed for dinner, and very self- satisfied and complacent. Later Nieuhoff descended, just as dinner was served. Forsythe came to the conclusion that he had been unduly on the alert—when, as Nieuhoff lifted an arm, he saw a distinct splotch of red on the man's wrist above his cuff.

Dinner over, Bougdanov glanced at his watch, then looked at Forsythe.

"Come, my friend! We have just time to make arrangements."

Obediently, the American followed him into the library. On the large center table was an opened briefcase, with papers strewn around it. Forsythe took the chair at the table, and Bougdanov handed him a cablegram, properly filled out.

"Here is the cablegram from the President, my friend. Nieuhoff is now preparing the statement which you will sign, in presence of our guests. Do you think you can carry it off?"

"Of course," said Forsythe, glancing over the cabled message, and laying it down. "These other papers—look here, general! They look pretty genuine, and I see Bayer's name on that portefeuille. Why not bring in your yellow friends and leave them here for two or three minutes? Never fear, they'll do their own examining of these papers!"

Bougdanov rubbed his hands, and then pawed his white whiskers, beamingly.

"Good! Admirable! You have a head, my friend."

Forsythe rose, pocketing the false cablegram.

"I'll run up to my room—they'll be here any moment now. Tell 'em I'm just getting the cablegram now—anything you like."

He hurried from the room. As he passed through the salon he saw Nieuhoff busily working over a typewriter, Princess Orloff looking over his shoulder at the work. Forsythe went on quickly, unobserved. He was suddenly afraid of what he might find. That man they had fetched in from the taxicab—

Perhaps from haste, perhaps thinking such precaution needless, Nieuhoff had left the door of his room unlocked. Forsythe entered, closed the door again, switched on the lights. Upon the bed lay a man, well-trussed, blood upon his face. He was unconscious.

Forsythe fell to work, cutting the cords that bound the man—he must be Bayer—mopping his face with a wet towel. Upon this discovery, everything was changed. What had seemed a game of childish proportions, based upon the almost unbelievable credulity of men, now assumed darker aspects. Here was not graft alone, but actual crime. That faked cablegram from the President, that statement with the signature of the consul general, would be ultimately disproved; meantime, incalculable damage would be wrought to the prestige of the United States. Their plan was to keep Bayer out of the way for a few days, probably—

The eyes of the man on the bed came open.

"Quiet, Bayer, quiet!" Forsythe was working rapidly, bandaging the deep cut above the ear. "Do nothing, or you're lost! Do you understand me?"

"Yes," murmured the other, staring at him. "But who are you?"

"Never mind. No time to talk now. Lie here and get your strength back; you'll be safe enough until I return. I'll get you out of here somehow."

"My briefcase!" Bayer made a convulsive movement, which Forsythe repressed with strong hands. "The trade agreement with Manchuria—with the Japanese—"

"I'll get everything," Forsythe assured him. "Listen! Obey me, or the whole game is up. Understand? Lock the door of this room. Don't open it unless I tap three times, or unless you hear a shot. Use your head, old man, and depend on me."

"But who—"

"Never mind now. Get that door locked as soon as I'm out. See you later."

With this, Forsythe slipped swiftly from the room and went to his own room at the end of the hall. Barely had he switched on the lights and given his dress tie a twitch when he heard the heavy tread of Bougdanov, who appeared in the doorway.

"Come! They are here—"

"Right."

Together they descended to the salon, where the princess was talking with Nieuhoff. The latter turned and extended a typed document to Forsythe.

"Here you are!" he exclaimed. "Sign this, read it to them—that is all!"

With a nod, Forsythe pocketed the document, typed on the official stationery of the consulate general. All three of them went on to the library; after them floated the voice of Princess Orloff in a soft "bon chance!"

Then Forsythe found himself exchanging bows and hand-grips with the Chinese general and colonel, while the captain-interpreter grinned.

"Pray be seated, gentlemen," said Forsythe, assuming his own chair before the papers and open briefcase. "Unfortunately, I have an appointment in half an hour, so let's get to business. I have here a cablegram. Shall I read it to you? Better, captain, that you put it into Chinese."

He handed the cablegram to the interpreter, who read to his delighted superiors the very flattering phrases, supposedly sent by the President of the United States, and his assurances that General Fu Wei would receive the unlimited support and backing of America. The audacity of the thing drew a gasp from Forsythe, who had not read the message.

"We may keep this cable?" inquired the interpreter. Forsythe waved his hand.

"By all means. And here is my own statement."

He drew forth the typed document, and the interpreter proceeded to read this also. Bougdanov pawed his whiskers and beamed approval; Nieuhoff listened attentively, his sallow features tensed. Forsythe, now prepared for anything, heard the smooth assurances of the consul general that General Fu Wei would be supported by the United States, that his claims to the overlordship of all China would be recognized, and so forth. The Chinese general and colonel were delighted beyond words, as their glittering eyes testified.

"There is no doubt in this matter," said the interpreter in rapid dialect to the other two. "You see this embossed note paper. You have seen the other documents. This is more than we had hoped for, indeed."

"It is sufficient," returned the general, and his colleague nodded. "It must be signed."

Forsythe took the typed sheet, opened the briefcase, and found a proper envelope. Nieuhoff extended a fountain-pen. Forsythe tested it, signed the statement, and blotting it, folded and placed it in the envelope. Bougdanov rose.

"One moment," he said to the interpreter. "I believe there is a stipulation—"

The general produced a wallet, and from it took a cashier's check on the Yokohama Specie Bank. Bougdanov passed it to Nieuhoff, whose eyes dilated greedily.

"It is safe enough," he said in French. "They may, of course, stop it, but will have no valid reason; besides, we will cash it first thing in the morning."

Forsythe remained, gathering up the scattered documents and replacing them in the briefcase. He found Nieuhoff eying him with narrowed, speculative gaze.

"You may leave those things here," said the Russian.

"Very well." Forsythe rose. Nothing else for it now—he had hoped to avoid force, but knew that these documents must be saved for Bayer. "Have you a cigarette?"

The other extended his case, and he took a tube. Nieuhoff closed the case and pocketed it—and as he did so, Forsythe's fist swung up.

The short-arm jab jolted Nieuhoff backward off balance. Before he could recover or even cry out, Forsythe's left slammed into the angle of his jaw. He crashed backward and lay still. Forsythe paused to light his cigarette, glanced down at the quiet figure, then caught up the briefcase and left the room.

No one was in the salon; the Chinese visitors were being ceremoniously ushered from the house. Forsythe took the stairs two at a time, saw nobody, came to Nieuhoff's door, and tapped the agreed signal. There was no response. The door was locked. Impatient, dismayed, Forsythe drew back and flung his weight upon the door. At the second try, it crashed down.

The lighted room was empty, the window open.

In a flash he perceived that Bayer, probably fearing some further trap, had taken his chance of escape. Crossing to the window, he looked out. Directly below was the flat roof of the garage—and he beheld a dark figure just swinging to the ground.

"Bayer!" His voice reached out urgently. "Wait for me!"

A rush of footsteps, a wild oath—he looked back over his shoulder to see Nieuhoff in the doorway, reaching hand to pocket. Tossing the briefcase from the window, Forsythe swung around. The little pistol leaped out into his hand, just as Nieuhoff's weapon came clear.

The two shots blended together.

An instant later, unharmed, Forsythe dropped to the garage roof, found the briefcase, and gained the ground. Bayer caught him as he stumbled.

"All right? Good. Come along."

Five minutes afterward, in the wide Avenue Kléber, Forsythe waved down a passing taxicab and pushed Bayer into the vehicle.

"The Tientsin Club, mon ami."

"Look here!" protested Bayer. "I want to go—"

"You're going with me," said Connor, and gave his own name. "No great damage has been done except to your skull—unless my shot finished Nieuhoff, which I don't think. What we need is a drink and a talk, and we'll get it."

GET it they did, in Connor's rooms, while he swiftly worked

getting rid of his mustache and sideburns, and into his own

clothes. He talked as he worked, giving Bayer the entire

story.

"So you see," he concluded, "no harm's been done—"

"No harm? Good Lord, man!" exclaimed Bayer in dismay. "Don't you realize that those Chinese will start their propaganda at once, that the United States will be dragged in—"

"Nope." Connor gave him a quizzical smile. "They won't do anything of the sort. They'll either jump on that gang good and hard, or keep quiet. My guess is that before to-morrow morning poor Vanessen's death will be avenged, the check will be taken back or payment stopped; and the whole gang will be in a bad hole all around."

"But why?" demanded Bayer, staring. "With my name signed to that statement, on our own official paper—"

Connor chuckled. "It wasn't," he said. "No one looked to see what name I signed. As a matter of fact, I signed none. I merely wrote the words 'Go to hell' and folded the paper."

Connor and his guest were at breakfast next morning when they heard the news. It was brought, in fact, by Connor's general manager.

"Of the most interesting, perhaps," he said, his sleek Chinese face wrinkled with smiles. "But of the most sad, also. An old man, General Bougdanov, seriously hurt, his friend M. Nieuhoff killed, Princess Orloff prostrated—"

"What!" exclaimed Connor. "Who did it?"

"Nobody knows, Mr. Connor. Robbers entered their villa just at dawn."

With a bow, the Chinese departed. Connor looked at Bayer, and grinned.

"What did I tell you, eh? I guess they've paid up for Vanessen! And," he added, "I will say he was right about one thing—she was a nifty blonde!"