RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

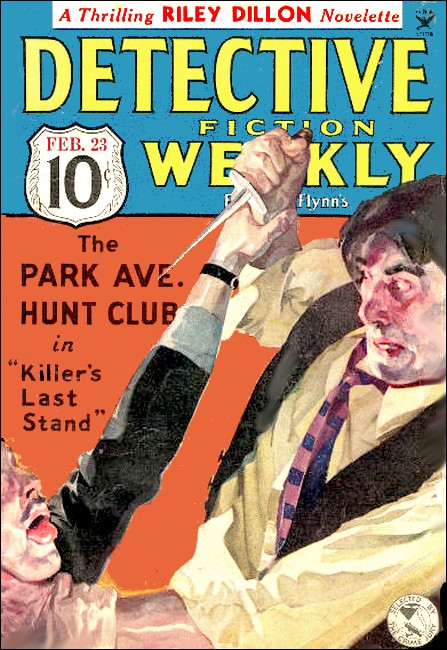

Detective Fiction Weekly, 23 Feb 1935, with "The Brute's Emeralds"

IT was frequently Riley Dillon's custom, of an afternoon or evening, to stand in pleasant talk with the house officers or the assistant managers of the Waldorf, which sometimes put surprising information in his way. Not only was he a permanent guest of the hotel, but his friendly, whimsical air, his charming personality, had made him a universal favorite.

No one suspected that he was not a retired lawyer, or perhaps a lucky broker who had got out ahead of the crash. Not a soul in New York, indeed, was aware of his actual occupation. Even Philp, the stolid private detective who transacted so many orders for him, was quite unaware that Riley Dillon was what is popularly termed an enemy of society, or that his chief interest in life was precious stones.

At three-thirty of; Monday afternoon, December 24th, Riley Dillon was chatting with one of the house officers near the elevators, when he noticed two people who left a car and paused for a word before separating.

The face of the man jerked astonished recognition into him—half recognition, that is. Riley Dillon never forgot a face, even if it had changed greatly. But the face of the woman positively made his heart skip a beat, so lovely was it with its indefinite sadness, yet so filled with animation and sheer beauty.

A young face, with a hint of loneliness, of inner agitation, that instantly fired his imagination.

Riley Dillon had an eye for a beautiful woman, but he was never deluded by mere surface beauty. This girl, he knew, had the intangible allure more powerful than all else in the world, the beauty of personality.

"D'ye know that man, McCabe?" Dillon asked. The house officer nodded.

"As it happens, I do, Mr. Dillon. Not twenty minutes ago the floor clerk sent down a red ticket on him."

"Which means—"

"That he was entertaining yonder lady in his room. I investigated and found the door open; it was quite all right. He's a gentleman named Castro, from Buenos Aires."

Dillon, who knew the gentleman was nothing of the sort, smiled a little.

"D'you mean, McCabe, that I couldn't have a lady visitor in my room?"

"Being what you are, sir, you'd arrange beforehand at the desk, or you'd leave the door open. Strait-laced? We are, for a fact. This is the most careful hotel on-earth, Mr. Dillon. We have to be, with our clientele—"

A bellboy came up to them. "Telephone, Mr. Dillon. On the floor extension."

Dillon went to the phone rack near the desk, striding blithely along. He had the fed of great things in the air this crisp December day. He could sense an electric alertness which hinted at impending events. When he had picked up the telephone, he was certain of it.

"Philp speaking, Mr. Dillon, if you want that report on the Park Av'noo Martyns—"

"By all means. Go ahead."

"Well, this dame is French, from the name. Homer Martyn married her last year abroad. He inherited that tobacco fortune a couple of years back, and has been raising hell on the money. They don't get on. No children. Frankly, he's a bad egg. A week or so ago Winchell's column predicted a separation very soon—"

"Never mind all that," cut in Dillon. "I wanted detailed information on their movements."

"I got it. Can you leave a man speak?" wailed Philp indignantly, "it cost me money, but I got it. Tonight they're dining alone at your hotel, on the roof. That means sloppy weather because he hits the liquor hard. Tomorrow night, a Christmas dinner with the Van Beurens in 36th Street. Wednesday night they entertain, and fly to Miami next day."

"Fine," Dillon responded. "That's all I need to know. Send in your bill as usual, and a merry Christmas to you, Philp."

"Same to you, sir, and many of them."

Whistling a cheerful air, Riley Dillon betook himself to the elevators and caught an express to the Starlight Roof. Here there was a great bustle going on, and decorations for the evening were being installed. The genial master of ceremonies approached and greeted Riley Dillon in French, "I'd like a table tonight for myself alone, Rene," Dillon said. "I think the Homer Martyns have a reservation?"

"For nine-thirty, m'sieur. Everything is taken already, but for Mr. Dillon we can always make an exception. I can give you a table near the Martyns, if you like."

The matter arranged, Dillon took the down elevator to the fifteenth floor and sought his own room.

HIS campaign to secure the Martyn emeralds had opened. As to

later details, he was supremely unworried; Riley Dillon never let

the forelock of Opportunity slip his grasp. If this French girl

who had married the dissolute heir to the Martyn millions wore

those gleaming green stones tonight, Dillon meant to get them

before the dawn.

First, however, came something else. From his trunk he took a fat volume of clippings, turning over the pages with his deft, nervous fingers. Suddenly he paused. A newspaper clipping, three years old and from a French paper, stared up at him. The text proclaimed that here was a picture of Raoul Du Puis, the most famous jewel thief in Europe. Convicted of a clever robbery in Marseilles, Du Puis had slipped out of the country and escaped.

Dillon took a pencil and sketched in a beard and mustache on the portrait of Du Puis.

Now the face became that of Mr. Castro from Buenos Aires.

"Faith, I thought as much!" muttered Dillon. "He couldn't change the eyes."

The lean, mobile features of Riley Dillon, which could beam with such warm friendliness, now became harshly alert. The gray eyes beneath his black brows, which could flash so gaily, now narrowed in suspicion. Riley Dillon did not believe in coincidence. That the cleverest jewel thief in Europe should be stopping at the Waldorf just at the time the Martyn emeralds were coming here to dine—no, no! That was not coincidence.

Mr. Dillon had no interest in protecting the Martyn emeralds for their owner, but he had a vital interest in protecting them for himself.

He collected jewels; not ordinary stones, but gems that were famous or of fabulous worth. Their value did not concern him. He loved them for themselves. His life was wrapped up in them. The whole background of his existence was a mosaic of precious stones.

He was one of the greatest experts in jewels extant, but not a soul suspected it.

Dillon did not gather gems by commercial methods. He was, in simple words, a thief; but he had his own rigid code of ethics. He never stole for profit. With him it was a game, a jaunty, keen pitting of wits and deft skill against all the world. This was why he lived in the Waldorf, the most carefully policed hostelry on earth, whose entire staff could sniff a scoundrel under a hundred layers of rank, social position or wealth. It spoke volumes for Riley Dillon that he was the most valued and popular of all the hotel's patrons.

Sitting down to his telephone, he called the French consulate. There was delay; an affair three years old is not easily brought to light. Finally Dillon had the right party.

"I believe," he said, "that here in New York I have seen the man Du Puis. In case I make certain of the identification, what action should I take?"

"May I call you back in an hour, Mr. Dillon?" was the reply. "I believe the police department here have certain papers regarding this man, who is a Belgian. There would be the matter of extradition and so forth. I can give you full details a little later. At the moment, I recall that the man can be identified by a blue dagger tattooed upon his left wrist, and a large reward is offered for him in France. Say, in an hour?"

"Thank you," said Dillon, and hung up.

He was satisfied that he could have Castro ejected from the hotel in ten minutes. Otherwise, he was not yet certain of his ground; besides, there was a reason for hesitation. And then—there was the face of that girl. Riley Dillon was an incorrigible sentimentalist where a woman of striking and delicate beauty was involved.

He juggled the facts mentally. The Martyns would arrive this evening at nine-thirty. Homer Martyn was a dissolute waster; his wife was an unknown quantity. They were on the ragged verge of separation. Castro had entertained a lady this afternoon, a woman too lovely to be associated with such a rascal. Had this any connection?

With a sigh, Riley Dillon opened his rosewood humidor, selected one of his special Havanas, and trimmed it. He lit it with his accustomed care. To ruin the aroma of such a weed by overheating, would have been no less than sacrilege.

He phoned the desk and inquired the number of Castro's room. He was well aware that each telephone call in this hotel was recorded, that every detail of action or of conversation was filed with the minute precision of a detective headquarters. To his quick astonishment, he found that Castro's room was upon this very floor, the fifteenth. Like his own, it was on the east side of the building.

Going to his dresser, he selected a gold-rimmed monocle having a thick glass, and looped the black ribbon about his neck. He picked up his hat and green ebony stick, and next moment was en route to 1542—occupied by Mr. Castro of Buenos Aires. Riley Dillon believed in removing possible rivals in person, and painlessly.

"And faith," he murmured, almost regretfully, "I'd remove him entirely if it weren't for what I saw in Paris three years ago today! I'll just remind him of that."

COMING to Castro's door, Riley Dillon tried it and then entered without knocking. Castro, who was in the act of trimming his beard, whirled and stared blankly. Into the dark eyes came a flicker of uneasiness.

"Well, M. Du Puis," said Riley Dillon in French, "shall we talk about things?"

Under the clipped, pointed beard, Castro's face became livid; then he pulled himself together quickly.

"Will you be seated, m'sieur, and tell me who you are?"

"No. You shouldn't roll up your sleeves—that left wrist tells me who you are."

"That tatooed wrist tells me who you are," said Riley Dillon.

Dillon screwed the monocle into his eye. It shoved up his black brow, enlarged the eye, and lent him a slightly grotesque appearance of cold dignity. In fact, it converted him into a very different man from his usual genial self.

"You may guess as to my identity," he went on. Castro, who had glanced at the blue dagger tattooed on his wrist, was facing him defiantly. "I prefer to keep you-on the uncertain edge of doubt. I desire to inquire as to your business here in New York."

"It—it is entirely private," faltered Castro. "A family matter."

"Oh, of course! By the way, do you remember a certain Christmas Eve in Paris, three years ago?" said Dillon calmly. "I saw you on that occasion; rather, you were pointed out to me. Judge of my astonishment, my dear chap! A man of your reputation, a clever rascal of a jewel thief, entertaining a dozen urchins from that orphan establishment in the Bois de Boulogne! It has always left me with a friendly feeling toward you, upon my word."

A strangled cry broke from the other man.

"If you intend to arrest me, get it over! You are from the police?"

"Guess. I know everything you have done here in New York. I know that this afternoon, for example, you had a visitor—"

An expression of anguish crossed the bearded features of Castro; anguish, so poignant and genuine as to leave Dillon startled.

"Do not drag her into it, I implore you! With all my heart, I beseech you to show mercy to her, this day before Christmas! Take me, but do not let it become public. This is all I ask."

"It's a good deal." Dillon regarded him curiously. "You're a criminal."

"You think so?" said Castro bitterly. "I was once a criminal, true. Since then I have gone straight; I have become an honest man. I made money in South America and repaid all those whom I defrauded in France. But you will not believe this."

"The law won't believe it," said Dillon calmly. Yet in his heart he was tempted to believe it. The tragedy in those dark, steady eyes told more than the spoken word.

"I'll give you a chance," he went on. "No one else knows your record. I shall say nothing of it, unless you make one step over the line. If you make one attempt at jewel-lifting, you're sunk. Understand? Don't try to be clever; instead, be wise. I'm giving you this chance—well, let's say because of those orphans back in Paris. That's all."

And turning, he left the room.

Well, he had warned the fellow off; that should be enough. After all, it was Christmas Eve, and something in the man's appeal had touched him. Gone straight, eh? Not very likely. They all said that, when they were nipped. He regretted that Castro had said no more about the girl with the lovely, sad eyes. Riley Dillon was curious about that girl. She was worth while. And why had Castro displayed such agitation at mention of her? It was hardly a love affair. With a shrug, Riley Dillon went his way. The incident was closed.

Not quite closed. At five that afternoon he received a letter by messenger from the French consulate in regard to Raoul Du Puis. A reward of one thousand dollars was outstanding for information that would lead to the man's arrest. It could be effected by a word to the lieutenant in charge of such matters at headquarters; the requisite papers had long since been filed with the police here, in case Du Puis should flee to America. Oddly enough, the letter said nothing about fingerprints. The one complete and certain means of identification was the blue dagger tattooed on the left wrist of Du Puis. With a careless laugh, Riley Dillon pocketed the letter. By this time, he reflected, Mr. Castro of Buenos Aires was no doubt packing and on his way.

Thus Dillon dismissed the whole affair. He had the Homer Martyns to think about now. And the glorious Martyn emeralds—the two most perfectly matched bits of green corundum in existence!

WHEN nine-thirty arrived that evening, Riley Dillon was seated

in the lobby. He occupied one of the big chairs near the desk,

biding his time over the evening papers. He was at ease and

unhurried. There was plenty of time to go to the roof.

As has been mentioned, Mr. Dillon did not believe in coincidences. His disbelief was positive and logical. He had written what he thought about it in that anonymous but extraordinary monograph entitled, "The Fine Art of Theft," whose ironical pages had left the police of two continents gasping and infuriated.

"What we term coincidence is merely an effect," he had written. "For every effect there must be a cause. As a rule the cause is human. Therefore the effect is the result of a finite human purpose which must be discovered or at least taken for granted. Look always for the design, the agent, the cause, the human equation—but never assign it to chance."

So, when he glanced up from his paper and caught sight of the same girl who had been with Castro that afternoon, he did not assign it to coincidence, Instead, he caught his breath at sight of her, transfixed.

She was now regally attired in evening wear, jewels sparkling in her hair, a sable coat about her shoulders. Beneath her arm the girl carried a small leather case, which to Dillon's knowing eye looked remarkably like a jewel-case. She swept past Dillon and went to the desk, which was behind him.

"I want a room on the fifteenth floor, please," she said abruptly. Her voice was very clear and ringing, with a faintly foreign accent. "I'll register for it myself; it is just for the night. I'm to meet my husband here, and if he decides to remain, he can then register for himself. Meantime, I may have visitors. I suppose that's all right?"

"Absolutely, Mrs. Martyn," responded the desk clerk. "I can give you the suite 15H on the east side, if that'll be all right. Do you wish to go up now?"

"No. When my husband comes, we're going to the roof."

"Then I'll phone the floor clerk, and you can pick up the key there until one o'clock. After that, all keys are sent to the desk."

Martyn! Riley Dillon sat staring blankly at nothing. Mrs. Homer Martyn. This was the girl with the sad, lovely eyes who had visited Castro that afternoon. And now she had demanded a room on the same floor Castro occupied. Coincidence? Devil a bit of it. Dillon himself was on the fifteenth floor; but that was different.

Abruptly, her ringing voice came to him again. She was directly behind him.

"Will you have this case sent to Mr. Castro, please? See that it's delivered to him in person."

"At once, Mrs. Martyn."

She was evidently well known at the hotel. Now she passed in front of Dillon again, crossed the lobby, and took one of the couches there. After a few moments, a young man came hurriedly into the lobby, looked around, and hastened to join her. Their greeting was not cordial. At least on his part; it was irritated. Dillon surveyed him critically.

Homer Martyn was heavy-jawed, his features were flushed, sullen, and puffed by dissipation; his eyes were arrogant and brutal. The girl rose, refused his arm, and departed a little ahead of him, head high, level gaze sweeping about. Martyn followed her.

So she had taken a room here for the night. Why? Domestic trouble, of course. She must be on the very brink of leaving her husband; affairs between them must have come to a crisis. And Castro had somehow caught her in his outspread net. The rascal had victimized her with his smooth ways. She must have sent jewels in that case to Castro. Were the two great emeralds, owned for a century and more by the Martyn family, in that case?

A soft whistle broke from Riley Dillon as he came out of his chair. Had the wily Castro tricked him?

"Faith, there's only one real coincidence in all this affair," he thought with a whimsical smile. "And that's the one that puts me on the fifteenth floor also. And unless I miss my guess, it'll be a damned unlucky coincidence for Mr. Castro this night!"

WHEN, a little later, Riley Dillon made his entrance upon the Starlight Roof, his gray eyes swept around and found what they sought. Castro was alone at a table, in the far corner.

Dillon went to his own table, which adjoined that of the Martyns, well back from the dance floor and near the corner window. Once seated, Riley Dillon handed his waiter an envelope.

"A bit of a Christmas present for you, me lad," he said cheerfully. "Also to make you remember that I'm keeping this table for the entire evening. I may be called away from time to time, but I'll be back. Now, don't be bothering me with any menu, but bring me a good dinner. No wine, thanks."

If he were to become possessed of the Martyn emeralds this night, he could not afford to dull the fine edge of his brain with alcohol.

Unobtrusively, he concentrated his attention upon the couple at the next table. At all events, the Martyn emeralds were not yet in Castro's hands. They were worth getting, those stones; Riley Dillon eyed them a little hungrily as they glimmered on the white breast of the girl. Two huge, pear-shaped emeralds of deepest green. They were hung upon a flimsy, lace-like necklace of platinum and gold, hand worked, but far too frail a thing to carry such massive stones. Old and flawed as they were, they were wonderful. Probably Castro meant to have them cut up into smaller stones, flawless and far beyond diamonds in commercial value.

Homer Martyn was drinking, and no doubt had been drinking before coming here. His wife drank nothing. The tension between them was quite evident, and Riley Dillon appraised them both very easily. The girl was aristocratic, high-strung, lovely. She would shrink from any public scene. The man was, very simply, a brute. She was no doubt in actual fear of him; he wore a vicious air as he eyed her.

Dillon rose, with a word to his waiter to delay his dinner. He had the situation in hand; he knew now exactly what must be done. First of all, cheat Castro, keep the rascal from tricking this girl. Noting that Castro was apparently quite engaged with his meal, Dillon strode out of the place.

Five minutes later, he was downstairs in his own room.

Riley Dillon at work was no longer the sauntering, whimsical, negligent gentleman of leisure. Now he was like some efficient machine, keenly alert, every movement deft and accurate.

From his suitcase he took what seemed a fountain pen. He unscrewed it. On the desk fell a metal shank and a number of metal segments which fitted together cunningly. By means of these bits of metal he could duplicate any key which he desired—an invention of his own, albeit for obvious reasons unpatented.

He already knew the exact pattern of the pass-key of the hotel. In fifteen seconds he had fitted together a key to serve the same purpose. He tried it on his own door to make sure, then slipped out of the room.

Here on the east side there was no floor clerk; that was one less item to worry about. Fifteen forty-two was down the next angling corridor. There was no one in sight as he came to it, inserted his key, and entered. The door closed behind him.

Dillon knew already every detail of the room. The case sent up by the girl, if not in sight, would be in the steamer trunk in one corner of the room—a trunk of transparent leather such as one finds abroad. Within thirty seconds Dillon had satisfied himself that the jewel case had been carefully stowed away. He knelt before the trunk. It was locked.

A French lock, of course, in which the tumblers were turned twice instead of once. From his pocket, Dillon took another of those singular fountain pens, and opened it up. This one contained tiny segments, intended for small locks. He fitted a few together; made a key that turned the lock.

The lid of the trunk came up. There before him was the leather case. Dillon caught at it and sprang the lid. Jewels glittered in the light, a profusion of jewels of all sorts, such as a woman might acquire from the check book of a wealthy husband. A very handsome little fortune was here.

"Such a fool!" muttered Dillon angrily. "After I warned him, too! Well, I've saved these for her, at all events."

He poured everything into his handkerchief, knotted the corners, pocketed it. The jewel case he returned to the trunk, which he then locked. Next minute he had switched off the lights and was sauntering along the corridor.

Back in his own room now. Swiftly, he deposited the loot in a bureau drawer, then returned to the elevators and so to the Starlight Roof. He came back to his table without a glance at Castro's corner, but was aware of the man there.

"The entree now, sir?" murmured his waiter, and Riley Dillon nodded.

The Martyns, he noticed, were still quarreling. The girl's eyes were angry, the man was flushed and jeering. That he was in very ugly mood was clear, yet the woman's restraint was still in force.. Possibly they were appearing here for some social reason.

Riley Dillon's interest grew with his curiosity. He could well imagine what tumult occupied her heart, and with all his soul he admired her fine spirit. She spoke little. Only when her gaze met the eyes of her husband did a glint of scorn and contempt flash into them. And to think that this splendid creature should be caught in the crafty net of that scoundrel Castro!

"It's a fool I am," Riley Dillon told himself, "but she'll be needing a helping hand before this night's gone, I'm thinking. And now I'm in position to give it."

Perhaps she sensed his interest. Her eyes rested lightly upon him, dwelt for one cool instant, then roved away. Riley Dillon was more guarded after this warning. Knowing she was caught between two fires, his heart went out to the girl. On the one hand, this drunken brute of a husband, and on the other the crafty rascal who was looting her.

Suddenly the floor was cleared, the lights were dimmed. Veloz the dancer was about to do her act.

There was a burst of applause, a whirl of riotous color beneath the spotlight, and every eye was fastened upon the moving figure of grace in the white radiance. Every eye save that of Riley Dillon. He, and he alone, sensed the explosion at the next table, saw the swift movement.

Homer Martyn lurched forward. His arm shot out, and from his wife's neck he tore the flimsy chain of platinum and gold with its pendant emeralds.

"They belong to the Martyn family, not to you!"

His voice came through the crashing music, followed by a volley of abuse. He stuffed the necklace into his waistcoat pocket. In the dimmed light, Dillon could not see the face of the girl. She rose, disdainful and cold, and made her way from the room, the jeering laughter of her husband following her.

Presently the lights flashed up again. Homer Martyn was muttering loudly to himself, so loudly that in the silence Riley Dillon caught his words.

"So that's the end, is it? I'll show her—damn her!"

That's the end! She must have uttered these words as she rose and departed. Martyn staggered to his feet, waved aside the waiter, and made his way among the tables. Riley Dillon cast one glance across the room. Castro had disappeared.

After a moment Dillon, too, rose and strode out of the place. He was in time to pick up Martyn as the latter lurched into a down elevator, mumbling to himself. The man had drunk hard and deep this night. Riley Dillon stepped in after him.

"Lobby floor," grunted Martyn, flushed and ugly.

They left the car together. Martyn headed straight for the desk, and Dillon strolled slowly after, coming to the desk alongside him as Martyn spoke with the clerk.

"Gimme a key to my wife's suite. Yes, I'll register—sure. Sign anything. I'm the one paying for the damned suite. Put it to my charge account."

The desk clerk turned to Dillon, inquiringly. Riley Dillon smiled.

"I must have left my key in the room, and the door's locked. Will you kindly give me the spare key?"

He tucked it into his pocket with a word of thanks, passed out to the mail desk, and there inquired for mail. There was none. He produced a cigarette, lit it. By this time Homer Martyn was heading away from the desk for the east elevators. Dillon followed him carelessly. Once out of that car, in the corridor, he might have a chance at the necklace. Right waistcoat pocket. He could see a glint there as the necklace was half-exposed.

The two men entered the car.

"Fifteenth," growled Martyn, on whom his last drink had told strongly.

"Same for me." Riley Dillon said pleasantly.

The car stopped. Martyn stepped out. Dillon delayed; he never neglected such trifling details as alibis. He could always catch up with this staggering drunk. He exchanged a smiling word with the elevator operator, put a Christmas tip in the man's hand, then left the car. The door clanged behind him.

Straight down the corridor was Riley Dillon's room. Martyn was heading past it, lurching as he walked. Another figure appeared unexpectedly. The two men halted. Dillon, in astonishment, stepped into the alcove of the stairs to remain unseen. He heard a gust of voices—Castro! This other man was Castro! Why, the slick devil!

Suddenly there was a scuffle. An oath exploded from Martyn; for an instant the two figures were as one. Then Martyn staggered across the corridor, brought up against the wall, and sank down. Castro turned and strode rapidly away. Not toward his own room, as Riley Dillon noted. He was going toward Mrs. Martyn's suite. His figure disappeared.

Dillon darted forward, then came to a halt. Martyn was close to his own door, and was struggling to gain his feet. Castro must have knocked him down.

"Help me!" gasped Homer Martyn, aware of Dillon. "For God's sake—a lift—"

After all, the man was better out of it; a drunk would only complicate matters now. Riley Dillon turned, unlocked the door of his room, then took Martyn by the arm and got him on his feet. A groan came from Martyn. He clutched Riley Dillon's arm, and somehow stumbled forward into the room.

Dillon tried to get him into the armchair near the bed. The drunken man missed the chair. He came to his knees and pitched forward, caught at the bedside, saved himself. Rather disgusted, Dillon aided him to rise, then forced him abruptly into the chair.

"Sit there," he said. "Take it easy. You're all right."

Homer Martyn peered up at him, then his head fell forward on his breast. Suddenly Riley Dillon came alert. He stooped, reached forward. For the first time, he recollected what he was after. Then he straightened up, his gray eyes cold.

The necklace was gone from Martyn's waistcoat pocket.

"So that was it, eh." Dillon was out in the corridor in ten seconds, leaving his room door closed but unlocked. "Frisked him and knocked him down, eh? Well, Castro me lad, I warned you! Now you'll take your medicine."

The letter from the consulate was in Dillon's pocket. Castro was with Mrs. Martyn; he had the rascal where he wanted him. Dillon himself might lose the Martyn emeralds—for this time—but he would save that lovely girl, at least. He would save her jewels from Castro, and unmask the rogue to his face.

He came to 15H, then checked himself abruptly. The door was open an inch or so. From within the room came the voice of Castro.

"Where are the emeralds? You should add them to the rest."

"No, no!" It was the clear, ringing voice of the girl. "He—he tore them from my neck, upstairs. That was the last straw. That was why I left him, told him everything was ended. But the emeralds aren't mine, you see. They belong to his family. That was really why he tore them from me—an insult, a final indignity. No, let them go. I have enough without them to live on."

Riley Dillon smiled to himself. Thanks to him, she would have enough! He rapped at the door sharply, then thrust it open and stepped into the room. He closed the door behind him and stood looking at the two. His monocle was in his eye; his look was cold, dignified.

They sat by the center table. The girl stared at him, startled, wide-eyed, a hint of recognition in her look. Castro was as though petrified. Pallor crept into his bearded features.

Riley Dillon saw the telephone on the desk and stepped toward it.

"Pardon me, Mrs. Martyn," he said crisply. "I'm a stranger to you; but not to this man here. I have to warn you that he's a well-known jewel thief and confidence man, with a record against him and a conviction in France. The police are now awaiting a call from me in order to arrest him. I have the proof in my pocket if you wish to see it."

From Castro broke a low groan. Again his eyes became haunted, tragic, as he stared at Dillon. The girl was white-faced; she seemed incapable of speech, of movement.

Riley Dillon laid his hand on the telephone. "Du Puis," he said, "I gave you fair warning. You disregarded it. You played your dirty game with this young woman. You got her into your net. You tricked her into sending you her jewels. Well, me lad, you're sunk. You don't leave this room until the police arrive."

He lifted the telephone receiver.

Suddenly the girl shot from her chair. Like a flash she was upon Dillon, catching his hand, thrusting down the receiver on its rack, staring into his face.

"No, no!" she gasped out. "You don't understand—you don't understand! He is my father!"

IT was Riley Dillon's turn to be frozen speechless. From the girl, still clinging to his arm, was pouring an impassioned, frantic torrent of words. Her father! No one suspected it, no one knew it; her father was supposed to be dead. But she knew of her father's past. He, from afar, had always watched over her. If Homer Martyn learned this secret he would not hesitate to use it against her, bring her into public disrepute, make life a living hell for her.

Riley Dillon swallowed hard. Now he understood Castro's terrible agitation at the mention of this girl.

"I sent for him," she hurried on in agonized, pleading words. "I had him come here to New York, to help me. I am afraid of my husband. He—he is a brute! I had no one else. And he came, my father came, although it meant danger for him. He was safe, in South America. But he came here to help me."

Now Castro came forward and took the arm of his daughter. A strange, helpless dignity sat upon him, as he drew her from Dillon.

"It is no use, my little one," he said. "This man is a detective, and detectives have no heart. Well, m'sieur, take me if you wish, but leave her alone, spare her—"

"Good God!" exclaimed Riley Dillon, taking a step backward. The monocle fell from his eye. "Detective? I'm no such thing. No, no. Why, I never dreamed this, man—I never suspected it!"

"I thought you knew everything?" said Castro, with a trace of disdain.

"I told you the truth this afternoon, m'sieur. All those whom I defrauded have been repaid. In Buenos Aires I am a man of reputation, I have position, money. The future lies before me. The past, alas, cannot be denied! And the law has no mercy. Look!" He stretched out his left arm to show the tattoo mark there. "Here is something that can never be removed, and it damns me. This thing stands ever between me and my daughter, m'sieur. It is my punishment for the past. You understand?"

"I understand," murmured Riley Dillon.

"Ah, have pity upon him!" exclaimed the girl suddenly. "Look! I gave him my jewels, everything I could lay hold upon. He was to sell them for me. I shall divorce this brute to whom I am bound, and go to South America. And you would call the police—"

"Heaven forbid!" exclaimed Riley Dillon devoutly, and gathered himself together. The test of a gentleman comes in such an instant as this; and Riley Dillon met it in his own fashion. That charming, warm smile of his leaped out, transfiguring his face. He put forth his hand impulsively to the man before him.

"Castro, forgive me! I apologize to you; by gad, you're a better man than I am! Give me your hand on it."

"With all my heart, m'sieur." The strained, haggard man suddenly relaxed in a beaming smile as he gripped hands. "Thank the good God! After all, it is the eve of Noel—"

"Yes, Christmas Eve, begad!" Dillon exclaimed.

Then he checked himself. A terrible thought flashed into his mind—those jewels he had abstracted from the trunk! He could not hand them over now. He could not let these people know what he was himself. No, his one way out was to replace them and let the matter be closed.

He thought fast as he introduced himself to the pair, told them he was living here in the hotel. He painted for them a word- picture of an amateur detective and did not spare himself in the painting.

"Will you wait here for me, please?" he hurried on, eagerly. "I have done you a great wrong, Castro; I'm as glad as you are to have discovered it! It's close to midnight now. We must have a bottle of champagne together—perhaps we may return to the roof. But first I must visit my room and pick up a telegram that's waiting for me there. Will you wait here?"

They would. Castro was suddenly alight with gaiety, with friendliness, in the reaction to his terrific strain. His daughter, with tears in her eyes, thanked Dillon; and Riley Dillon bent over her fingers and kissed them, with his old- fashioned courtesy.

"Back in ten minutes!" he exclaimed gaily from the doorway, and left the room.

As he strode along the corridor, he cursed himself for a fool; yet he was amazed at the situation he had uncovered. Now he could understand why Castro, meeting Homer Martyn in the corridor and hearing the man's mumbled threats, had lost his temper and struck the fellow down. Martyn, of course, had not known him from Adam.

There was an element of ironic humor about the whole thing that brought a twinkle to Riley Dillon's gray eyes, a laugh to his lips, as he thrust open the door of his own room. Homer Martyn still sat in the chair, chin sunk on breast, his heavy, stertorous breathing filling the room with rasping sound.

IT was the work of a moment for Dillon to prepare the two keys

he needed. Then he took out the handkerchief stuffed with jewels,

swiftly made it into two smaller parcels in case he encountered

anyone in the hall, and pocketed these. Next instant he was on

his way again to Castro's room. He came to the door. At this

instant—he remembered it ever afterward with silent

thanks—a chambermaid came out of a room down the hall.

Instead of using his key, Riley Dillon rapped at the door, lest

the maid recognize him and know that he had no business here.

Then he took hold of the door handle. To his astonishment-the door opened. He stepped into the room—and it was lighted. Three men stood there, facing him.

"Why, it's Mr. Dillon, of all people!"

The night manager of the hotel, a genial Irishman whom he knew well. And with him, two other men; In a flash, Dillon knew them for what they were. Detectives.

"Hello!" His brows lifted, and a whimsical smile came into his face. "I was looking for Castro, but this seems to be a reception committee. What's up, Killackey?"

The hotel man threw up his hands. "Looking for Castro, eh? So are these birds from headquarters. Boys, this is Mr. Dillon, who sent in the tipoff about Castro."

"Glad to meet you, Mr. Dillon," said one of the two detectives, stepping forward. "You see, we got tipped off by the French consulate about your message, and we came up to collect this guy Castro, as he calls himself."

Riley Dillon sparred for time, perceiving the gulf that had opened under his feet. For a moment he was absolutely aghast.

"But I said nothing about Castro!" he exclaimed sharply.

"Oh, it wasn't hard to run down which guy you referred to." The detective chuckled. "Ain't many speaking French with the help around this hotel. We couldn't locate you—"

"You didn't try very hard," snapped Dillon. "I've been on the roof all evening. I suppose you wanted to collar the reward yourself, eh?"

The shot went home. "Well, when it comes to that," blustered the detective, "how come you're so thick with this guy as to walk into his room?"

"Because I made an engagement with him for the shank of the evening, me lad," responded Dillon blithely.

"We had a drink or so, and I've been feeling him out to see if he's the man you're after. Upon my word—"

"One look at his wrist will tell quick enough," said the other.

"Finger-prints?"

"Nope. This guy Du Puis got away from the Frog police in Marseilles before they had a chance to mug him or print him. But the tattoo-mark is all we need."

"You see, Mr. Dillon," intervened the night manager, "the best way to avoid trouble and publicity was for these boys to wait here until Castro shows up. We don't want any fuss around the hotel. So I'm waiting with them."

"So I observe," said Dillon cheerfully. His brain was racing fast. He was up against it now and no mistake. Let Castro be caught by these dicks? Never!

"Look here!" he exclaimed abruptly. "Why can't I give you chaps a hand? I know Castro. I can look about the place and fetch him here."

"Swell idea," said one of the detectives. "We're liable to be here all night, and I got to fill my kid's stocking sometime before morning."

"Good!" Dillon nodded. "I'll do it. But first I'll have to call Mrs. Homer Martyn. Let's see! She's in Suite 15H. I'll have to postpone our dance. We were going up to the roof."

He went to the telephone and sat down to the instrument, his gray eyes dancing, a merry devil of delight in his laughing face.

To pull the thing off right before these men, right under the noses of the two dicks—what could more delight Riley Dillon's heart?

The three men sank back into their chairs as he called the suite. The voice of the girl answered. He sent up a mental prayer that her wits might be quick and sharp.

"Hello! This is Mr. Dillon speaking. Please give me Mrs. Martyn—no, no, I want Mrs. Martyn!"

"But this is she—"

"No, no! Give me Mrs. Martyn. Faith, have ye had too much champagne to hear me?"

He glanced at the detectives and winked, shaking his head significantly. Then, to his untold relief, came the voice of Castro.

"Hello! This is Mr. Dillon. Like a good soul, will ye let me beg off that dance for a matter of ten minutes or so? I'll have to be going to the lobby floor and seeing a man who's asking for me there. What's that? Going right up to the roof now, are you? Then I'll meet you at the elevator in two minutes. Yes, by the floor clerk's desk."

"Very well, m'sieur," came the low, controlled voice of Castro? "I comprehend."

Dillon slapped down the receiver and rose with a laugh.

"Now, me lads—" and he looked hard at the two headquarters men—"I'll split the reward with ye, half and half; mind that. And my half of it, Killackey, goes to whatever charity you care to name; remember it. I'll be seeing you as soon as I can locate the rascal."

And he strode out of the room.

THANK the Lord for Castro's sharp wits! The man had to be

saved now at all costs. Riley Dillon felt a cold chill at thought

of what must have happened had he not returned to the man's room.

There was not a minute to waste. Yes, it could be worked

perfectly. The whole scheme flashed across his agile brain,

complete in every detail.

As he walked rapidly along, he took out the letter from the consulate, produced a pencil, and quickly scribbled on the back of the letter. He was making for the west wing now, and the lighted widening of the floor clerk's space came into sight before him. Ah, the floor clerk! Later, she might report his meeting with Castro—well, he must risk this. No way of avoiding it. And at best, it was a long, slim chance.

Castro was waiting, and under the eyes of the floor clerk, turned. Dillon greeted him, took his arm, and led him over to the elevators, pressing a down button. Under his breath he spoke rapidly.

"Two detectives in your room. Not an instant to waste. Do as I say."

Castro nodded, his eyes suddenly alight and feverish. The elevator door clanged open, and Dillon thrust him in.

They emerged on the lobby floor. Here, as Dillon knew, was the desperate gamble. If another dick were waiting here all was lost. Luckily, neither a dick nor a hotel man was in sight at the moment. Dillon whisked his companion around the corner into the lounge, plumped down on a sofa, and drew the other down beside him.

"Listen hard, now," he said rapidly. "You'll have to walk out of here as you are, and do it on the jump. Drop everything and go. Have you money?"

Castro nodded. "But—"

"No buts, me lad. Skip from the hotel. Go to the drug store on the corner opposite, telephone back to your daughter and explain to her. Take a taxicab down to the vicinity of the Pennsylvania Station. You can get a suitcase and some clothes easily in that neighborhood. From the station, you can get either a late train or connections for the airport at Newark. Take either a plane or a train to Chicago—to Chicago, d'ye hear?"

Into Castro's hand he thrust the letter from the consulate.

"They've no finger-prints on you, thank the Lord! But that mark on your wrist—the letter makes it clear, And on the back, I've written the name and address of a doctor in Chicago who can remove that tattoo-mark."

Castro, who had followed him alertly, suddenly slumped.

"M'sieur, it is useless," he said quietly. "Such marks cannot be removed. I have tried the best doctors. It is possible to remove the skin, yes, but then a scar remains."

"Devil take you, will ye listen to me?" broke in Riley Dillon. "This Chicago man can do it; he uses the Variot process, which not one man in a million knows about. It'll cost you pain, begad! The design is pricked, nitrate of silver is rubbed in, and tannin then follows. When the job's done, there's hardly a scar.

"Here!" Dillon pulled out the two handkerchief-bundles. "Here are your daughter's jewels. I got 'em out of your trunk. How? Never mind that; faith, I had to lie to those detectives! But I got 'em. Take 'em along."

"God bless you!" said Castro simply, then started. "But you—you will get into trouble over this."

"Devil a bit of it," Riley Dillon laughed. "No listen: before your plane or train goes, whichever you can grab first, send the hotel a wire. State that you've been called unexpectedly to Washington, tell them to hold your baggage, that you'll be back in three weeks. That'll throw them off the Chicago trip."

"Eh? But—"

"Shut up. At the end of three weeks, your wrist will be healed. Come back here, come openly, face the music! When they find that tattoo mark is gone, that you're really from Buenos Aires, that Mrs. Homer Martyn knows you and vouches for you—why, devil and all! You can laugh at the lot of 'em. D'ye understand?"

Castro drew a deep breath, his eyes like stars.

"If this is so, if the work can be done—yes! Ah, m'sieur, you have given me new life, new hope—"

"Stop your gab and get out of here on the jump." Dillon leaped up and put out his hand. "And don't thank me. Thank those poor little devils of orphans back in Paris, three years ago. Off with you, and a Merry Christmas!"

CASTRO departed, hatless, coatless, as he was. Riley Dillon

turned back to the elevators, and found one of the house officers

standing there. He produced cigarettes and asked for a match.

"I suppose you haven't seen Mr. Castro about?" he asked idly. "Or do you know him?"

"Yes, I know him by sight, Mr. Dillon. Haven't seen him, though. I just got a call from the night manager to pick him up and send him to his room, if I did. Someone there is waiting for him."

Dillon, with a nod, stepped into the elevator.

He was elated, joyous, keyed up to a pinnacle of alert gaiety. He had just managed the impossible, as only Riley Dillon could manage it, and he laughed again to think of the detectives waiting there in Castro's room. As for Castro, he had sketched a perfect campaign, which the man was fully capable of following to the letter. For Castro the future was clear, and deserved to be.

Then, abruptly, Riley Dillon remembered the Martyn emeralds.

At the thought, he shrugged. Castro had taken them from Homer Martyn, no doubt thinking to add them to his daughter's jewels. Well, that matter could take care of itself. The emeralds were gone, that was all there was to it.

"Better luck next time!" thought Riley Dillon, leaving the car on the fifteenth floor. With a nod and a cheerful greeting to the floor clerk, who would be on duty clear into Christmas morning, he turned toward his own room.

What next? To get rid of Homer Martyn, of course; and see that he did not molest his wife. Give her a chance to receive that call from her father and be set at ease. It were best, perhaps, to take one of the hotel managers into consultation. If Martyn were drunk and incapable of making trouble, he could be put to bed and left to himself in another room.

Dillon pushed open his door and switched on the lights. Martyn was slumped down in the chair. Startled, Riley Dillon suddenly stopped short, staring at the man. Then he took a quick step forward. That stertorous breathing was hushed. There was no sound in the silent room. Dillon reached forward and touched the slumped figure.

Homer Martyn was dead.

HERE was a troubled gathering of hotel officials, and at Dillon's suggestion one of the headquarters men was summoned from Castro's room.

"Mr. Dillon," explained one of the house officers, "found a drunk unable to navigate, just outside his door, and it being Christmas Eve and all, brought him into the room and plopped him into a chair. Now the man's dead and turns out to be Mr. Homer Martyn of Park Avenue. There's no earthly reason to doubt Mr. Dillon's story—"

There was none, as the house physician stated. That Martyn had died from acute alcoholism, and possibly heart failure, was fairly obvious and would be confirmed by an autopsy.

Riley Dillon, with a sigh of relief, found himself alone in his room and everything clear sailing. He called the roof, ordered the check charged to his account and his table given up, and undressed. He was ready for bed.

"Faith, it's been a busy night!" he reflected, as he stepped to arrange the pillows to his liking. "And so far as I'm concerned, an empty night—except for the thought of a bit of good work well done. If we—ouch!"

His foot had struck something under the bed. He stooped, and then a sharp exclamation broke from him. He remembered all of a sudden how Homer Martyn had plumped down, had clutched at the bedside to save himself.

Dillon rose, holding up the necklace with the pendant emeralds. It must have slipped from Martyn's pocket, unobserved, in that fall.

He held the emeralds to the light. Green and lovely, they shimmered like living things.

"Payment!" he murmured. Then he slowly shook his head. "Payment! And would I be taking payment for what I've done this night?" he went on, with a touch of scorn. "Ye brought mortal peril to a poor man this night, and ye pulled him out of it again. If ye took payment for that deed, it's a sorry fellow you'd be."

He lifted the receiver. A twinkle came into his eye.

"Besides," he added, "there might be questions asked as to what became of the necklace, if that girl remembers about it. Hello! Give me the night manager, please. I want to report something I've found."

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.