RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

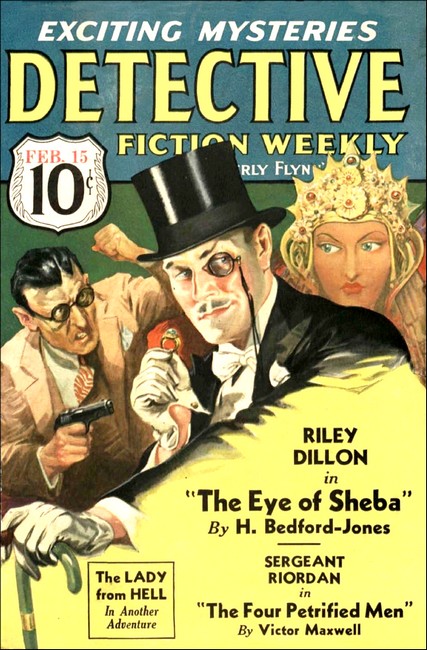

Detective Fiction Weekly, 15 February 1936, with "The Eye of Sheba"

The door was flung open. Count Rosati stood there.

Irish wit against oriental cunning—Riley Dillon versus the

dark man in dark glasses—with the gem of Solomon as a prize.

RILEY DILLON was breakfasting in his room at the Waldorf this morning. Very much in his room. He was breakfasting in retrospect In thoughtful appraisal of the previous evening. He even ignored his morning paper to think about it.

His keen, whimsical features were restless and frowning, the gray eyes cold beneath their black brows. As he lit his cigarette over his second cup of coffee, his gaze fell on the gaily- covered, gaily-decorated little brochure at his elbow, beside the open, unread morning paper. He winced slightly at this souvenir of the Charity Bazaar. Astrological forecast, indeed! His horoscope stared up at him, to flick back his thoughts anew to the previous night, to the woman, to the jewel.

He was devoutly glad now that he had gone to the Charity Bazaar. The woman, the jewel, the man—hm! He could sense that the woman, behind her veil, was beautiful. No matter; the world did not lack beautiful women for Riley Dillon. The man with the dark glasses, he could sense, was a rascal. No matter, again; the world did not lack rascals for Riley Dillon. But the cat's- eye—glory be, what a cat's-eye! Flaming like a jewel planet in the dusk of the booth! This mattered.

The world had lacked cat's-eyes of such water, for Riley Dillon.

He had wandered idly about the place. Perfectly groomed, his lean, slender figure drew the eye, with its subtle air of distinction. Dillon might have been a broker, a corporation executive, a studious counselor retained by big business. So he was usually regarded, even at the hotel where he was so well known and liked. He was none of these things. He was a rascal, ruled by his passion for precious stones. He was a thief, not for gain of lucre, but for gain of jewels; he could not resist them.

None suspected it. None suspected the magic of his deft, slim, delicate fingers, the astounding knowledge of jewels packed away in his swift, alert brain.

He had been somewhat bored when he caught sight of the booth, in a corner of the glamorous room.

"Seek Fortune Here," read the sign. Why not? He was always seeking fortune; it was fortune brought to bay that had yielded him most of his marvelous collection of gems. And as he paused at the booth, his brain was jogged—by intuition, sixth sense, hunch. Instantly, he was bored no longer, but alert. A Negro boy in Oriental garb stood at the hangings, and drew them apart.

Dillon, whose shirtfront was crossed by the black ribbon of a monocle, passed through. He was enclosed with the seeress.

His glance drifted past the draperies, studded with moon and stars and other supposedly occult tokens, to rest upon the veiled woman. She sat at the other side of a small table. The veil, he guessed, was transparent to her, although not to him. None the less, a woman with those slender, lovely arms and shapely hands, with that lithe, poised figure in its bizarre costume, must have features in keeping. And her voice, breaking upon his scrutiny, was further guarantee of loveliness behind the veil.

"You wish to know all?" she demanded liltingly.

The voice had a trace of accent, an affected rhythm hard to place; but it had decision and purpose. No amateur, but a professional; engaged for the occasion.

"Faith, I'd like to know more than I see," said Riley Dillon pleasantly.

"When you know what I see, you shall know all. The fee is five dollars."

Dillon handed over a banknote. She put it into an ebony box, and his eyes sighted the ring on her finger. He was dazed. The stone shimmered with life in the dim light. Pure deep green, none of the yellow or brown tints of cheap chrysoberyls. Clear green, luminous, mystic, of purest hue, of that chatoyance or moony lustre, so like a cat's-eye in the dark.

Dillon forgot the woman, neglected to appraise her slim hand. He had not known there was such a stone in New York. By the satiny smoothness, by the cut, it was an antique. In its curiously-fretted, heavy gold setting, it breathed to him of allure and brought a catch of his breath.

"Your two hands on the table, please." The woman was speaking. "The palms up."

DILLON seated himself and rendered his palms; he could not

tear his gaze from the ring, nor conquer the temptation to fitful

glances. The usual patter entered his ears and he heard it not.

Her voice went on and on. Suddenly she interrupted herself and

brushed his hands aside.

"You're interested in my ring?"

"A needless thing to you," he answered.

"And why so?" she queried sharply.

"A charm against the evil eye?" Dillon's quick, whimsical laugh rang out, his gray eyes warmed. "How can the eye be evil that looks upon you, then?"

"So you know the stone? Name it."

"Chrysoberyl."

She produced pencil and a pad of paper.

"Write the word, and sign your full name. I'll give you a reading of your handwriting."

He wrote swiftly:

Chrysoberyl. Harrison Smith.

"Faith, I should write you a poem!" he exclaimed. "One minute, now, till I think of the rhyme—"

"Enough." She caught back the pad. "Not your own signature, eh? You trifle with the present, but you cannot trifle with the future. Come! Your horoscope next. Give me the date and hour of your birth."

She ignored all gallantry, yet her rigmarole was amusing.

"A Christmas child, at two in the morning," said Dillon. It was not the truth. Something warned him. The year he assigned was false.

A man had slipped in and was standing at one side. Dillon was suddenly aware of him, and looked without seeming to look. A slim, quick man, sleekly black-haired, in dark glasses enclosed against all light. Riley Dillon's memories stirred, but could not focus; something unpleasant, shadowy, evasive, like a dream that is fled. Well, it would come in time. He was interested, now.

"You were born under Capricorn, the tenth sign of the zodiac," the woman was saying. "Emperor Menelik of Abyssinia and other noted persons were born under that sign. It is one of the earth signs—"

"With a touch of heaven," put in Dillon blithely. She ignored him.

"Your planet is Neptune; but have no fear. He is the character tester; be yourself and all is well. The beryl is your zodiac stone, September your fortunate month, Saturday your lucky day. Follow your indications, but be guided by this forecast."

She produced, a gaily-decorated little brochure.

"In this you'll find the indications for the month. Tomorrow, I see, is a day of great importance to you; the stars are favorable. Something is on the way to you under their influence—a letter, a newspaper, an advertisement, perhaps. Be prepared. Seize upon opportunity. You're about to get a great desire."

Dillon did not accept the finality of her tone. He studied the silent man from the corner of his eye. Something foreign, like her accent; difficult to place.

"My horoscope, is it?" he murmured, and an impulse brought out a common Arabic phrase of politeness. "Kullema tu'ti huwa tayyib—whatever you give is good. Thanks, light of the world!"

"What?" Her voice was startled. She knew the words. "You have been in the East?"

"The East Side of New York." And Dillon chuckled. "Well, then, one look at the lovely face before me, and I'll believe in the good fortune you foretell!"

She laughed. For an instant, she swept her veil aside. Dillon met the dark eyes, glimpsed the dark, olivine features. Then he rose and bowed, and with a gay compliment and a word of thanks, took his departure. The man, too, had been dark. Italian? Arab? French? Impossible to say.

He sought the hotel lobby, stood in talk with a house detective and the night manager. There was much bantering and chaffing at his casual inquiries. The fortune teller? She was an Abyssinian or Egyptian dame who had been in the papers lately. A princess she claimed to be; she had worked up at lot of press agent stuff. On the level? Huh! A regular racket, wasn't it? Could be played on the level, of course.

That was all.

BACK at breakfast again, Riley Dillon poured out more coffee,

glanced with a grimace at the flamboyant horoscope, frowned

thoughtfully. His mind was bridging the years. Arabic was the

clue, yet it eluded him.

What a jewel! What a woman, for that matter; but his thoughts ran on the stone. Old, very old. From time immemorial, the cat's- eye had been a fascinating gem; the side toward the light ever dark, the side away from the light, translucent. This was no ordinary Singalese commercial stone. Dillon could sense that it was extraordinary; he had a flair for such things; he felt his pulses tingle at the memory of it.

He wanted this stone himself.

Suddenly he started. The man with the dark glasses? The evil eye—there it was! The evil eye behind those glasses. He had bridged the gap. His memory recalled a street brawl in the Muski quarter of Cairo, the old native section. Natives crowding about a slim dark man; a knife, a blow, a fall, a flight! A rather vague memory, nothing clear-cut, nothing definitely suspicious.

Yes, that was it. Nothing on which to hang suspicion or knowledge. Arabic notions of the evil eve are not what they are usually supposed. The owner may be quite innocent. An admiring glance from that evil eye may cause death or misfortune, without the owner meaning any harm.

"So the lady set the stage to work the old skin game on me, eh?" mused Riley Dillon. "I wonder why? And what will the next move be? And the ring—oh, you beauty! Just let me have a chance at you, and begad, I'll have you!"

He glanced idly at the gay horoscope.

DILLON smiled slightly as he looked over the horoscope—one of batches, assorted according to the signs of the zodiac. Today was Saturday. The month was September. Lucky day in a lucky month, according to the woman's patter. A top- notch day, this! But that was for Riley Dillon to say, after the cards had been turned face up. He tossed the brochure into the waste-basket and turned his attention to the morning paper.

Abyssinia again; war. An ancient empire rich in romance; storied Ethiopia. He turned the page, and the name struck him again. "Abyssinian Princess Helps Open Bazaar." And what a name she had! Kaloola Clefenha Foota Jal. It brought a smile of derision to the lip of Riley Dillon. Accompanied by her husband. Traced her ancestry to King Solomon, through the one-time emperor, Menelik. "A ring set with oriental cat's-eye from the amulet necklace of the Queen of Sheba..."

Dillon's lean, somewhat cynical features became a trifle hawk- like; his gray eyes, so striking beneath their black brows, hardened. The woman, her lineage, the story of the stone—all a fake, of course. Like a star sapphire, the cat's-eye was a charm against witchcraft and the evil eye, allegedly; therefore was of "amulet" value. A grain of truth in that. No; if he went after this stone, there was no reason to show mercy.

Historical stones, many of them gems of especial significance, were in his collection. His passion was always for the stone itself, not for its value. This cat's-eye was almost unique in its marvelous color; it was the chrysoberyl of his dreams, finer than any he had already.

He remembered the woman's words, the little game up her sleeve, and with a chuckle turned to the advertising section of the newspaper. Could she really have been so barefaced about it all? Yes. The item in the "Personal" column struck out at him:

Stranger in New York wishes to meet gentleman interested in Oriental topic and precious stones. Mutual advantage and profit. Address in own writing, Chrysoberyl, E 765.

Remarkable! A sardonic but amused smile touched Riley Dillon's lips. What a conjunction of the stars to make this his fortunate day! The ring, old Menelik of Abyssinia as his fellow Capricornian, the warning to expect something of great importance, the reference to advertisements, the princess, the Queen of Sheba's amulet—a portentous coupling of events indeed, but not born of the stars!

So Riley Dillon was being steered; they were going to "take" him! Beautiful idea. His interest in the ring had brought in the man to size him up. They worked fast, these two. They figured him idle, indolent, easy-going; probably looked him up with the hotel people. Good! There was his opening.

A shabby, silly game, implying a simple victim. The stone, of course, was the lure; a bunco game of sorts.

"And faith, I'll have to fall for it!" murmured Dillon, as he reached for the telephone. He got the day manager on the line. "Riley Dillon speaking—sure, the top of the morning to you! Can I have the use of a bellhop for an hour or two? Any of the lads will do. But not in uniform. Send him up in street clothes, and thanks to you."

There was Philp, the private detective who worked frequently for him; but this was no job for Philp. He wanted no one, especially that astute detective, to know too much about him. And these bellhops were sharper than any detective, for a simple job like this.

The bellhop arrived—a chipper, quick-eyed young fellow, who, like all the hotel staff, knew and liked Riley Dillon. Dillon sat him down at the writing desk; then frowned. Everything here was Waldorf paper; he did not want that. His eye fell on a novel, the latest detective story, and he jerked out the blank flyleaf.

"Here; take this, me lad, and write a note for me."

"Yes, Mr. Dillon. I ain't so hot on spelling."

"Doesn't matter." But it did, and it mattered tremendously. An obvious hint from Destiny, here. Later, Dillon recalled how carelessly he disregarded it. "Pencil will do. Date it at the top. Then write:

"Deeply interested in your Personal ad in this morning's paper. Would like a café table appointment at your early convenience."

"Let me know when you get it."

The bellhop was slow to get it, but at length succeeded, after much repetition on Dillon's part and facial contortion on his own.

"Go ahead, me lad. Put on the address: General Delivery, Columbus Circle Station, City. And sign it, Joseph Zenophon."

Here was a tussle and no mistake.

Chuckling, Dillon spelled out the name. Even, in New York, he decided, this was one name that would not be drawing mail.

"Now for a plain envelope—devil; take it; there are none! I don't want: the hotel name to show. Why haven't you one in your pocket, me lad?"

The bellhop grinned; "I can get one in the office, Mr. Dillon."

"Of course." Dillon caught up the pencil and scribbled rapidly: Chrysoberyl, E 765. He handed it to the bellhop. "Get a plain envelope—plain, mind: you—and copy this on it as address. Put the note you've just written inside, and seal it. Go to the newspaper office, hand in the envelope at the 'E' window in the Want Ads-office. Take a taxi; we're a bit: rushed. Here's expense money." Dillon handed over a five-dollar bill, then went on:

"Now, listen carefully! You hang around there and spot the man. who calls at the 'E' window and gets this note. Use your bean, me lad. I'm laying a bet he'll be a dark man with dark glasses, but I want a good description of him: Then come back and report."

The boy assented and took his departure.

RILEY DILLON glanced at his watch; five to nine; He had acted

with his usual prompt decision, and now he could take his time.

His mind worked accurately; he knew human nature; he figured that

someone would call about ten o'clock for any replies to that

advertisement. The reply to Joseph Zenophon ought to be waiting

at the Columbus Circle station by four o'clock, say. It would be

an evening appointment, no doubt.

Whistling blithely, Riley Dillon, set about shaving, bathing and dressing. That cat's-eye, he told himself, was already as good as in his very hand. It was a comforting and gladdening thought.

At ten-forty, Dillon was lighting one of his prime Havanas with, his usual deliberation, when a tap came at his door. He did not respond until the cigar was perfectly alight, for nothing destroys the aroma of a cigar like overheating. Then he opened the door. The bellhop, entered.

"It was a man in dark glasses, all right. Gray suit, about my height; sort of spry on his feet, a brown face, black shoes, black hat. He answered the note all right."

"Good work," said Dillon. "How do you know he answered it?"

"I seen him write it, sir. He stopped at the desk where people write ads and wrote out a reply. Here's the envelope your note was in. He threw it away, and I picked it up after he had gone."

The bellhop proudly extended a pink envelope ripped open at one end. Dillon eyed it, and saw the words, Chrysoberyl, B 765 written on the face. He started slightly, a ghastly sense of error coming upon him.

"Hold on, me lad, hold on!" he exclaimed: "You say this is the envelope you put my note in?"

"Sure, Mr. Dillon. I got a pink one on purpose, so I'd make sure of your note being called for."

Dillon swallowed hard: "How do you know he answered this note of: mine?"

"He got a bunch of letters, see?" explained the bellhop. "Then he went to the desk and looked at 'em all. He compared this one with a piece of paper he had in his hand. Then he chucked the others away without opening them, wrote out a reply, put it in an envelope, and went out."

"Begad if you aren't a smart one, me lad!" said Dillon. He glanced again at the pink envelope, then eyed the bellhop; his expression was quizzical, severe, amused, all at once. "It's a fine forger you'll make, if you don't watch out."

"I don't get you, sir."

Dillon pointed to the envelope. The inked address was in his own handwriting.

"Oh, that!" The other grinned. "Well, sir, you said to copy it. I couldn't copy your writing, and that word Chrys—Chryso—well, whatever it was, I didn't know it; so to make sure I traced it with a piece of carbon paper on the envelope and then went over it with a pen. Wasn't that all right?"

A laugh burst from Riley Dillon as he flipped the pink envelope into the waste-basket. He was not the man to blether over spilled milk.

"It's a jewel you are, me lad. Now, about four this afternoon you take a taxi to that station near Columbus Circle and ask for mail for Joseph Zenophon. Fetch the letter here, and there's a ten-spot in it for you."

The bellhop departed. Riley Dillon, laughing to himself, dropped into a chair, puffed at his cigar, and then sobered.

An obvious trap, carefully avoided—and his foot had gone in. After all, that couple were crafty. That word "chrysoberyl," the envelope compared with the paper left in the booth, the writing the same! Trying to flank the snare, he had gone slap into it, thanks to the clever bellboy. The joke was on him. But what of the situation?

That note in the envelope, not in his own writing, would make him out to be wily in their eyes; the address in his own writing would make him out stupid; one of those smart easy-marks who trip themselves up. As they had no doubt figured him the previous night. Well, it was not so bad.

His mind fondled the cat's-eye again. From the Queen of Sheba? Pretty raw, that; still, he had a vague memory of something among his clippings. Budge, the famous Orientalist, had translated the old Ethiopian and Amharic writings. He had something about chrysoberyls in his clippings.

His trunk opened up, Riley Dillon delved into its depths. Monographs, booklets, clippings—everything connected with gems, with locks, with gold and silver craft, with thievery. At last he found what he sought, and ran through the clippings until he came on those he had cut bodily from books of translation.

He frowned over them. Amulets? The Suleiman who was King Solomon? Balkis, the so-called queen of Sheba or Saba? Their son, Ibn al Hakim, carried to Jerusalem to be educated by Solomon, neatly bilking the old man out of gold and gems, and getting away with the loot—a necklace of precious cat's-eyes which preserved him against all witchery, so that he lived to beget the Ethiopian kings? The signet of Balkis, the great seal of Solomon....

"Bah!" Riley Dillon tossed the book of clippings aside and went to luncheon.. This mass of legend was of no value, and luncheon was of distinct value. He rather believed that his next meal would be shared with an Italian-Egyptian rascal and the charming princess, Kaloola Clefenha Foota Jal of Abyssinia. What a name! He was still chuckling over its absurdity when luncheon arrived.

But over the ring of the princess, he was exceedingly serious.

FOUR-THIRTY. The reply was in Dillon's hand, precisely as he had expected:

The first table on the left of the entrance; Bella Roma Café, 9 this evening. You the guest. Chrysoberyl.

Dillon mused upon the note with sombre eyes. The whole thing was a cheap come-on game; the lack of finesse repelled him. He could predict the whole sordid scheme to a T, knew the moves that would be made, and found them bad to the taste.

But that cat's-eye tugged at him with a strange force. A stone whose very existence was unknown to the world of gems—yet no such stone could remain unknown! Riley Dillon was puzzled, curious.

And something more. He knew the Bella Roma quite well. It was a hotel with an unsurpassed cuisine; a quiet place in the late forties, off Sixth Avenue. And yet, all of a sudden, his brain clicked at the written words. Bella Roma, Bellasera—Bellasera! That was the name. He remembered it now, with the details, for suddenly the gap was bridged. Marchese di Bellasera, so-called; adventurer, rascal, thief, blackguard, murderer. The Cairo street, the man with the evil eye, the knife- stroke, the hue and cry, the escape. The newspapers next day had been full of it. The fellow was wanted in a dozen countries. Bellasera!

Riley Dillon dressed with his usual care that evening. His attention to detail was elaborate, as ever, but quite mechanical. Recollection of the man had sobered him a bit; it changed everything. He must be prepared for anything now; the background was ominously bloody. Probably the man had shadowed him about the bazaar, the hotel the preceding night, had learned his name, what little there was to discover about him. Well, so much the better! That stone was now his, at any cost.

Twenty minutes ahead of the appointed time, Dillon walked into the Bella Roma, and nodded to the major-domo.

"Give me a seat anywhere, for the moment. I have friends coming presently; I think they have a table reserved."

Yes. As he passed to the table indicated, he glanced to the left of the entrance. The rendezvous had been well chosen. The table there, with a "Reserved" sign on it, was flanked by the vestibule, and semi-private.

The place was well filled. Dillon settled himself comfortably and ordered a small flask of Chianti while he waited. The string orchestra, pleasantly subdued, was playing airs from "Ernani." The attentive waiter held a light for his cigarette, suggested an evening paper, and presented it with a flourish.

Riley Dillon glanced through it negligently. Then his eye was caught:

CHARITY BAZAAR HOAXED

SOCIETY INDIGNANT

A short, laughable story, that drew a gleam to his gray eyes. He carefully tore out the story, trimmed the edges of the clipping, read it over again. Then he pocketed it and leaned back in his chair.

The cat's-eye was definitely his, now.

Yes, he knew exactly what would happen; yet there would be a trick somewhere, and no doubt a pistol to boot. They were sharpers, but far from fools. Dillon beckoned his waiter, had a telephone plugged in, and called the Waldorf. If he were right, he would be back there before the night shift came on at eleven. The trap would be quick and fast, the pay-off rapid. Good! He'd be the sucker, and chance his wits against theirs.

"Riley Dillon speaking," he said. "Give me the house detective. Who's on the floor now? McCabe? Good. Put him on, please."

He spoke briefly, and finished his call. When he glanced up, the table to the left of the entrance was occupied.

The man of the dark glasses, sallow, swart, perfectly dressed; the woman, tawny and lovely. Dillon rose, paid his charge, and approached the corner table. The man stood up to receive him and bowed from the hips, heels together. He did the business of gentleman very well.

"Mr. Dillon, I think?" he said, and Dillon affected surprise. "May I present myself: Count Marco Rosati. The lady—I may present you? Mr. Dillon, my dear. My wife, the Princess Clefenha Foota Jal."

Riley Dillon's bow was the acme of grace, of courtliness; a bow in the finest of French tradition, not lifting the lady's hand to his lips like an untrained movie actor, but lowering his lips to brush that hand. A very jewel of a bow, deferential, and of the rarest quality.

"My fortunate day, indeed," he murmured. "I am enchanted."

"So you recognize me?" He faced a ravishing smile, a gesture to be seated, and complied. Count Rosati glanced at his watch, and was devastated.

A thousand pardons; humiliation of the utmost, but a business engagement intervened. Mr. Dillon would, no doubt, replace him? He would rejoin them later, perhaps for cordials; perhaps here, perhaps not. Mr. Dillon expressed himself as charmed, and really was charmed, when Count Rosati departed.

It is always pleasant to find that one's predictions are coming true.

SO Dillon was alone with the lady. Slightly dusky skin, warm

and tropical, like mellowed ivory that had known Sheba's caravan

trail; massed black hair under a silver net; lustrous eyes, small

wickedly lovely mouth, a chin cruelly wilful, exquisite arms and

shoulders and figure. And on her finger, the cat's-eye.

Dillon was sardonically amused, was tempted to cry, "Well played!" For she did play it well, all of it. Her story startled him slightly, in view of that clipping he had read over.

She told him, during dinner, that Rosati's father had been an officer in the Italian army, captured at Adowa when King Menelik destroyed the invading army of Italy, in 1896. He had remained in Abyssinia, had gone into business there, had married. He had obtained the cat's-eye ring—how, she did not say. It was a gift to her when she married Count Rosati.

She and her husband had now left Abyssinia, had come to America, and because of the war, were about broke. She was frank, charmingly frank, about it. All this came out at intervals as the dinner progressed. She was able to earn precarious support by telling fortunes.

"And I must sell the stone," she said, with a shrug. "Shall I confess it? I noted your interest last night. I have been trying for some time to find a buyer. One cannot go to a dealer and get any price. When you answered the advertisement today, I knew you were interested. It was your hand-writing on the envelope, matching your writing of last night. It was not hard to learn your name. You see, I am frank. People who are desperate must be frank."

Dillon assented gravely. "But I know so little of such things!" he murmured.

"This is no ordinary stone," she said, leaning forward eagerly. "It was stolen from Menelik's treasure, It had descended directly from his ancestor, the son of King Solomon and Sheba. I have a paper guaranteeing this, under Menelik's seal."

Dillon's black brows lifted slightly. So this was it!

"The paper is here?"

"No. At our apartment. Come, with me, see it for yourself! It is hard for my husband to consent to this sale. He has agreed, but may change his mind. You would give a thousand dollars for the stone, no?"

Riley Dillon met her intent, inviting gaze. A thousand dollars? Not a fifth of the value of the thing. Cheap chrysoberyls are cheap; a superb one like this could command any price.

She slipped off the ring, pressed it into his hand. With an effort, he tried to conceal his heart-leap; he could not. He examined the stone, the ring itself; his delicate finger-tips scouted the massy gold, and suddenly he thrilled anew. He had seen such rings before this. He had made one or two, from curiosity.

"Yes," he said. With real regret he handed back the jewel. "If the guarantee is as you say, it's a bargain."

When they left the Bella Roma together, Dillon stole a glance at his watch, and his lips twitched. Exact—almost to the moment. Precisely as he had figured.

THAT ride in the taxicab was something of a nightmare to Riley Dillon, knowing all that he knew. He was no longer tempted to cry, "Well played!" The princess plied her arts rather crudely, now that she was depending on herself and not on the clever instigations of the man with the dark glasses. Except for that scintillating cat's-eye, Riley Dillon would have been bored, but he endured patiently for the sake of the jewel. And a little curiosity lingered. He could guess there was something new coming, somewhere, some novel twist to the old racket. This interested him. With such a prize in view, he could well afford patience.

The taxi halted. Dillon helped her forth; she stumbled, yielded to his arms, laughed a little. They took an elevator to the third floor. The apartment door was directly opposite the elevator. As Dillon entered, he caught the casual, deft movement of her fingers by which she slipped the catch and left the latch free. What a simpleton they must take him to be! Probably, he thought, the man had been somewhere out of sight in the vestibule below, when they entered.

Yes, Riley Dillon was unfeignedly bored by this section of the program. He yielded politely, calmly; took the seat on the divan indicated, refused the proffered drink from the bottle and glasses on the nearby table, looked up with some interest as the princess produced the guarantee—a bit of vellum, heavily inked with writing, and a large golden seal.

"Here is the pedigree of the stone, the guarantee, whatever you like," she said, settling down beside Dillon. "You cannot read the Ethiopian language, Mr. Dillon? Then let me translate—or wait! Here is a translation attached to it."

True. An attached paper, certifying that the stone was from the days of King Solomon, that it had descended in the direct line of Ethiopian kings for two thousand years. Riley Dillon languidly glanced over the English writing, glanced at the vellum document with more interest, glanced at the seal, and nodded.

"Yes, yes," he said, with an air of deep satisfaction. "Most interesting, really!"

"Then you will buy the ring!" She turned to him gratefully, impulsively. There was a slight sound at the door, almost imperceptible. Suddenly she leaped from the sofa and tore at her own hair. A cry came from her lips.

The door was flung open. Count Rosati stood there, and behind him, peering over his shoulder, the elevator boy.

"Oh! He attacked me, Marco—you saw?" screamed the woman. Her hair had become disheveled and loosened. She was hysterical, all in an instant. "I was afraid of him—he was: brutal—"

Riley Dillon yawned. But his gray eyes were alert.

Count Rosati dismissed the elevator boy with a gesture, came in, closed the door, and ordered his wife to be silent. His eyes were fastened on Riley Dillon. The dark glasses were gone, now. Protuberant eyes, large and staring; something queer about them.

Dillon was carried back again to that day in the streets of Cairo, and the yelling, cursing Arabs. The left eye was too fixed in focus; it was a dead eye, evil, fishy. Yet large and staring like the other, diabolical in its huge iris, greenish iris in a swart face. Eyes net to be forgotten, and the left eye false, made of glass.

"So," observed Count Rosati with deadly, intent deliberation, one hand in coat pocket. "I return unexpectedly, I find you in the very act of insulting my wife, the princess! I demand satisfaction—I shall have it, by God! or I'll kill you!"

Riley Dillon lifted his hand to his mouth, yawned again, languidly.

"By all means," he rejoined, rather wearily. "Your wife, the princess. Otherwise Jeanne Dupont, adventuress, Martinique Creole, sometime cook in a Park Avenue family. I refer you to the evening papers, which you may not have seen. And this document—tut, tut! Unworthy of you, sir."

"The Ethiopian," he went on, as the woman shrank, and the protuberant eyes gripped him staringly, "is a strange language, identical with ancient Armenian, sprung from the same root. This alleged document is written in Arabic, and appears to be the first sura or chapter of the Koran. The seal is pretty, being the seal of the scribe in Cairo who wrote it. By all means, bring in the police."

THERE was a little silence. The woman was frozen. But not the

man. A short laugh broke from him. With sudden shift, he caught

at the situation and whipped it about to serve him.

"So?" He gestured, as though sweeping everything aside. "Very well. Mr. Dillon, of the Waldorf, caught in the arms of a Martinique adventuress! This lady, I assure you, is my wife. So much the greater scandal all around when the story breaks in the morning papers. I feared your knowledge of Arabic; however, let it pass. You perceive, there is still a settlement in prospect?"

Right. Dillon felt a slight admiration for the rapid shift of front, the seizure of the exact phase of things that would be worth while. Decidedly, this man was no fool. The eyes gripped him; one alive and glittering, one dead, stony; both large and staring.

Yes, it would be a nasty mess in the newspapers; and they were prying chaps, these reporters. For reasons of his own Riley Dillon was not minded to have them on his trail. Not that it would come to such lengths, of course. With a word he could settle matters—but that cat's-eye must be his. And he was still curious to find the novel twist that this clever rascal would certainly employ. He glanced covertly at his wrist watch, and smiled again. Exactly as he had foreseen.

"I fear—well, just what sort of settlement do you propose?" he asked, with assumed hesitation. "Blackmail, I presume?"

"No!" snapped Count Rosati. "If such is your thought, sir, you are wrong. No gentleman would stoop to such a thing."

"Faith, I agree with you," Dillon said pleasantly. "What, then?"

"You want the ring. You shall have it. You shall pay double the price for it—which, after all, will still be a cheap price. Two thousand dollars."

As he spoke, the man reached out his hand, and the "princess" gave him the ring.

Dillon shrugged. "Well, it might be worse. But I don't carry such sums of money around with me. Nor check books."

"Understood. We'll go, say, to the Waldorf. You don't leave my sight until this is settled." The count moved his pocketed hand significantly. "I'll go to your room with you. Write a check. If the hotel cashier okays it, the incident is closed."

"Agreed," Dillon assented.

"And remember—I have a witness to this scene!" snapped the count menacingly. Riley Dillon only shrugged again.

A SHORT ride; ten minutes later, they entered the Waldorf

together, passed up the long flight of steps, went down the lobby

and procured Dillon's key at the desk. As they turned to the

elevators, Riley Dillon caught the eye of McCabe, the house man.

It was not quite ten-thirty. McCabe would be on duty for half an

hour or more. All was well, reflected Dillon cheerfully. He had

expected to walk in at ten-thirty. Well figured!

But, as they walked into his own room, Riley Dillon was alert, on his toes. The critical moment approached. Here was the unknown—the anticipated novelty. His interest was aroused, his curiosity keen.

"You'll have no objection, I presume," he said casually, "to letting me inspect that ring?"

"Not in the least," and Count Rosati sneered as he extended the jewel. "Perhaps you fear lest I switch rings or something of the sort? Bah!"

Dillon examined the ring again, and made certain of what he had before merely suspected. The stone was solidly embedded in the gold, which covered over its flat under-surface; with such a stone, that did not depend on reflection and reflected lights from below for its splendor, a stone that had no facets but was smoothly cut, this could well be.

He handed, back the ring and seated himself at the writing desk. He drew out a check book, dipped a pen, and glanced up.

"What name?"

"Marco Rosati," said the other, who was standing looking at one of the engravings on the wall, his back to Dillon.

Riley Dillon smiled slightly. Was it to be so crude, after all? He filled out the check with some care. Count Rosati came to the center table and laid the ring there, negligently.

Dillon tore out the check, blotted it, drew open the desk drawer again and put back the check book. In the drawer, his fingers moved swiftly, deftly; they slipped into the brass knuckles lying there.

Then he rose, holding the check in his other hand, and came to where the count stood by the table: Riley Dillon's eyes flickered for an instant to the ring. Well for him that a look, a glance, could tell him what he wanted to know.

"Your check," he said, and suddenly his voice was harsh, biting. "T tell you, I don't like this! After all; it is blackmail. I'm tempted to chastise you."

Rosati laughed sneeringly. He took the check, looked at it, and his smile died. His gaze lifted, anger in his face;—

At this instant, Dillon struck.

A QUICK, shrewd blow, and another. The left to the belt; bringing forward the head of Rosati—slap forward into the advancing right. The knuckles caught him smash at the angle of the jaw. Well-planned, well-timed, well-executed. What Riley Dillon lacked in brute force he made up in whiplike speed. Where he would not risk breaking those slim, delicate hands of his, the brass knuckles served well.

Rosati's head was rocked around by that blow. He was slammed into the wall. He fell, sprawled out on the carpet, and lay on his back, unconscious for the moment.

Dillon turned to the table, snatched at the ring, and made certain. He felt for the hidden spring; it could be only in two or three places. His deft fingers located it. The imitation stone, switched for the true one, moved and came out. A poor, flawed, worthless stone with the correct shape and size and cut But the other?

Falling on his knees, Dillon searched. Rapidly, vainly. Pistol in pocket, but little else. It was incredible; to his dismay, there was no stone, no hiding place. Such a thing could not be hidden from him, yet here was utter failure. Rosati had switched the stone in an instant, while he stood looking at the picture on the wall. Hands, pockets, clothes, hair—

In consternation, Dillon drew back. He was caught. He had failed. Not caught; he was prepared against the trap, but he was not prepared for failure. He wanted the cat's-eye, and he had lost it.

Suddenly he started, made a movement of repulsion. As the man lay there senseless, his left eye showed partly open lid, empty red socket; the shock of the blow, the fall, had emptied the socket. There on the carpet, half hidden under his shoulder; was the imitation eye.

Dillon reached for it, picked it up.

The unexpected weight astonished him. He turned it over—and a whistle came from him.

"Glory be! I thought there'd be something different from this chap—"

Rosati had passed his hand to his eye. A deft movement, hand to eye again; all done in an instant, as Riley Dillon could well comprehend. That was why Count Rosati had turned his back.

Here behind the false eye, in the cavity, fitting snugly and perfectly, the real stone in tiny clips. Undoubtedly the false eye would slip again into place; evidently there was a reason that Rosati's false eye was large, protuberant. Yes, a clever game. Probably one the pair had worked repeatedly. But they would never work it again. The real stone was gone now. It was in Riley Dillon's pocket. The false stone was slipped into the ring. The spring caught, it was held there. And the eye?

Dillon leaned forward. This was something new to him; for once, his fingers were awkward, yet attained their goal. The glass eye was slipped into place, fitted into the socket, the lid slid over it nicely. The prostrate man stirred a little.

"All right, McCabe! Come on in," Riley Dillon called.

The door opened and the house detective walked in, and stood waiting.

Count Rosati stirred, came to one knee. Riley Dillon took his arm and lifted him to his feet, helped him get his bearings, with hearty apologies and a warm, lilting laugh.

"Sorry, upon my word! I lost my temper for a moment—"

Rosati burst out in furious speech, then checked himself at sight of the grimly watching McCabe. Dillon thrust the ring at him, and the man pocketed it. Then he took the check, looked at it again, shot out an oath.

"What d'you mean by it, eh? You know perfectly well—"

Riley Dillon chuckled.

"Yes, my dear fellow. You may take back the ring; I've no use for it, really. It would be an unpleasant reminder to me of an awkward scene. And the check is for two dollars, to pay for taxicab fare and an excellent dinner. You see, Rosati, I don't buy jewels. I've no interest in buying such things, I assure you!"

Rosati quivered with rage. "Then when the story comes out—"

At a sign from Dillon, the grim McCabe stepped forward.

"It won't come out, mister," he announced threateningly.

"Eh?" Rosati whirled on him. "Who the devil are you? What d'you want?"

"You, if you make a fuss." McCabe showed his badge. "Bellasera—ain't that the name? I knew this gent the minute I laid eyes on him, Mr. Dillon. Want him turned over to the cops? I got an idea he's got a record."

Dillon eyed the unhappy, paralyzed gentleman quizzically.

"Yes? Or no? How about it, me lad? Or should I call you the Marchese di Bellasera?"

Rosati stared at them, speechless, his face becoming a dirty gray. Somehow, his eyes were in ill accord; they looked a little odd, as though the glass eye shot off at a stubborn angle. Dillon wondered whether he had put it in upside down, perhaps.

Then Rosati was gone—gone without a word, clutching the check, clutching the ring in his pocket, clutching the eye with heavy eyelid. Accepting defeat, but little dreaming of the loss to accept as well.

Riley Dillon, chuckling, moved over to the writing desk. He took up the jeweler's glass there, screwed it into his eye, examined the real cat's-eye curiously. On the flat, unpolished base were tiny marks, scratches. No! Letters in the old, almost unknown Ethiopian language, spoken only by priests; What were they? The names of Suleiman, perhaps, Balkis of Sheba?

"I say, Mr. Dillon!"

Dillon swung around. "Oh, McCabe! I forgot about you. Thanks, me lad; you served the turn beautifully."

"But what did it mean, sir? You've got me curious."

"Eh?"

"Why, that name Bellasera. You said it meant something—"

Dillon's warm, quick laugh rang on the room, as he handed McCabe the proper recompense for his services.

"Oh, that! And so it does, me lad, so it does. Most appropriate for our departed friend, under the circumstances. It means—good-night!"

And as McCabe exited, grinning, Riley Dillon looked down at the quivering, glowing Eye of Sheba in his hand.

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.