RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

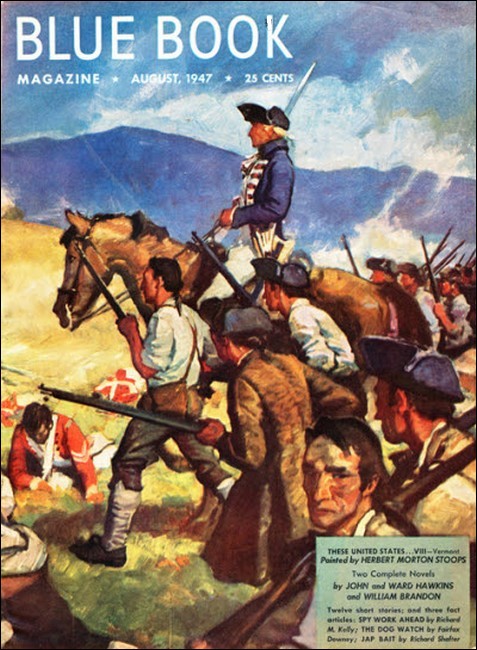

Blue Book, August 1947, with "Jewels Have a Long Life"

Are the things we love ever ours? The old Moor thought not: "I bought them! They were given me! They are mine!" he mocked. "Yet when you die—what? They are just so much gravel to you, then."

WILL PAGET paused with his host and guide, Roger Waynflete, outside the little Leghorn shop.

"This is the place," Waynflete said. "This man Hassan is the finest gem-cutter in Italy; but he's a devious rogue, an agent of the Moors, an arrant rascal who'll cheat you of your eyeteeth."

Paget smiled. "You forget, Roger, that for these many years I've been a goldsmith and jewel merchant in London town. Lead on."

Waynflete pushed into the shop and past the front attendant to the long workbench in the rear, where a man with clipped gray beard sat hunched above delicate tools and enlarging lenses great and small.

Waynflete spoke to him in Italian.

"Hassan, here's a client, Messire Paget of London. He speaks French but no Italian. Well, Paget, this is Hassan the Lapidary. Shall I wait for you?"

"No, no, get back to your counting-house, Roger. Many thanks. I'll find my way back to your house without any guide, when ready."

Waynflete departed. Paget drew up a stool, sat down, found Hassan scrutinizing him narrowly, and returned the scrutiny. Despite clipped gray beard, Hassan's lean features were smooth, unlined, ageless—a Moorish trait. His dark eyes were bright as stars. He had a thin, satirical mouth under a hawk nose, and a finely carven chin.

"I was expecting you, Sir William Paget," he said in fluent English, to the surprise of his visitor. "I heard from Paris that you had bought some gems there which would need re-cutting; and you were directed there to me…. Yes, I speak your tongue. Why not? There are English in Morocco, where I was born—or were, until Sultan Ismail expelled them from Tangier. That is why I am sometimes called El Maghrebi—the Moor. You are a man of high intelligence, favored by Allah. I am humbly at your service."

"Thank you," said Paget. He drew a packet from his belt and set it on the bench. "Here are the stones—poorly cut, poorly polished. Can you improve them?"

Hassan opened the packet. From wads of silk and cotton he disinterred half a dozen gems—four rubies and two large sapphires. He poked them under enlarging glasses, put a jeweler's lens in his eye and examined them, with the greatest attention. Paget, himself old in the trade, which had brought him a knighthood and royal favor, watched closely. He was amazed and disturbed that this man should know so much about him and his errand, but gave no sign of it. Finally Hassan turned to his visitor and nodded.

"You are a good buyer. The sapphires and two of the rubies will be valuable gems when re-cut. The other two rubies will lose half their weight, but will be brilliant."

"As I thought," Paget said. "When can you do the work?"

"Within two months. I will take the smallest ruby for my pay."

"You will not," said Paget calmly, and they fell to bargaining. Hassan came at last to a decent price.

"Signor Waynflete will pay it, and will take charge of the stones for me. I shall not be here," Paget said when they had agreed. Hassan, who was no darker than an Italian, laughed softly, and his bright eyes glittered sardonically.

"For you?" he said. "I suppose you think they are yours?"

"I bought them," said Paget curtly.

"Yes. Many say the same. 'I bought them! They were given me! They are mine!' Yet jewels have long life—hundreds, thousands of years. When you die—what? Can you take them with you? They are just so much gravel to you, then."

"Too true. You're a philosopher."

"No. An exile who wants to go home." Hassan leaned forward, and spoke with an easy air of familiarity and confidence. "There is only one way I can do it—by taking the king of my country a jewel so wonderful that he will pardon my past offenses. Sultan Ismail of Morocco loves jewels. He will welcome me and restore my estates when he sees the gem I shall bring him—a gem no wealth could buy."

"I know nothing of Barbary, but you interest me. I too love jewels. Show me this gem of yours."

"Allah forbid. I have not yet secured it," said the lapidary, laughing swiftly. "To get it will take money, much money—two thousand pieces of gold, and more. But to buy it, merely to obtain it! I have chosen you to provide this gold; you see, I know much about you."

Startled and astonished, Will Paget frowned.

"I, provide you with two thousand gold-pieces—a fortune? Not likely. You jest."

"I jest not; nor has Allah touched my wits," Hassan said earnestly. He produced a folded parchment and handed it over. "Read this at your leisure. It is an attested copy. Discuss it with your friends here, and with the Venetian consul. If the original is worth two thousand pieces of gold—forty-soldi Florentine gold-pieces—come back and see me tomorrow. But I must have the money within two days. Addio, messire!"

Paget, who was in some haste to be gone, pocketed the parchment and walked out, not sure whether this Hassan were a jester or a madman. For the moment he left the parchment alone; he could spare time on no nonsense, having matters afoot which he deemed of more importance.

BEHOLD, then, Will Paget sauntering, not so aimlessly as

appeared, along the colonnaded central square of Leghorn. So

broad and straight were the streets that from here one could see

the city gates. Paget, however, had seen Leghorn before, and now

he was less intent upon the city than upon the people around. Few

places on earth afforded a greater variety of types, since

Leghorn was a free trade port in those days—that is, in

March of the year 1694.

The Medici ruled in Tuscany, and Leghorn belonged to the Grand Duke, but was a city of absolute tolerance, where the only thing barred was politics or intrigue. Even the Turk or Moor could live and trade freely here, and did; and some queer things went on, as you might guess, within these arched colonnades where Saracen and Christian met as equals. Venetian, Spaniard, English, Fleming, Jew—every race babbled here and did business, to the profit of the shrewd and broad-minded Medici….

Will Paget, on the off side of forty, was journeying to Adrianople, there to serve as English ambassador to the Porte, but he was not hastening on his way by any means. He had a lithe, springy step, a quick smile, and his honor was as bright as his eye; momentarily, he had chucked Sir William Paget behind him and was enjoying freedom from the cares of trade and politics. To be honest about it, that romantic flowering of early middle age which drives so many a stout ship upon the shoals, had him in thrall, but Will Paget was no fool and was able to keep the helm. He had stopped over in Paris to see life, and had seen it. Now he was stopping here, with his old friend the merchant Waynflete, for private and urgent reasons not connected with his embassy.

PRESENTLY he smiled, as the chief of these reasons appeared,

seated in a light open carriage drawn by handsome grays, moving

slowly along. As Will Paget stepped forth and bowed, she caught

sight of him, and at her word the driver drew rein. With his

handsome attire and lean, erect figure, Paget looked a dozen

years younger than his age—and felt it, to boot. He

advanced to the side of the carriage and took the hand she

extended.

"A happy surprise, to leave you in Paris and find you here!" she said in French.

"No surprise, Contessa—you told me you were coming via Leghorn, so I came also," he rejoined. "But it is indeed a miracle, to find you alone, unescorted!"

She broke into a laugh. "Then be my escort. You shall come home with me. There is a Leone villa here, and I am occupying it for a week, before going on to Rome for the Carnival. Your friend the Vicomte is here—poor fellow, he lost everything at the gaming-table last night. So today he is making the rounds of the moneylenders."

Paget climbed in beside her with alacrity, grimacing at her mention of the Vicomte. The carriage proceeded slowly to the northern suburb of the city, called New Venice because of its canals and cleanliness and pleasant villas. And many an eye was cast at the handsome Englishman and the most famed beauty of Rome, thus riding together.

Everyone, of course, knew Flavia, Contessa di Leone, the young and beautiful owner of Rome's most renowned name and fortune; born a Colonna, wedded to the Leone heir, and now widowed, thanks to fever of the Roman marshes. Small wonder Paget had lost his heart to her in Paris, where half the court nobles had been at her feet; small wonder he had cast aside cares of state and had begun to pluck the flowers of romance! The Vicomte de Tournelle, it was rumored, had carried off this prize, but Paget had by no means given up hope.

If she was famously wealthy, as gossip reported, so was he. She liked him and treated him with cordial kindness—as indeed she did most men—and fanned his late-blooming flame till it burned high. Embassy? Embassy be damned, if he could win her by a bit of delay en route! He wanted, of course, to take her to Adrianople as his bride. What the Vicomte de Tournelle wanted, was not at all certain—probably her fortune. A rascal with a dark past, this Vicomte; a most engaging and charming rascal, yes, but none the less a very bad egg, by Paris report.

Having Flavia for once to himself, Will Paget now took full advantage of the opportunity. By the time they reached the pleasant little villa by the canal, the two of them were as intimate as though parted only yesterday, and she was hanging on his tales of jewels and monarchs—the two things went together, naturally—with avidity. She had inherited plenty of jewels of her own, for the Leone collection was renowned, but today she wore nothing except an emerald pendant on a chain about her neck—a large but rather poor emerald, Paget noted.

They went into the music-room. Flavia loved music inordinately. She sat at the harpsichord and played. Paget strummed a lute, and they sang together, until she abandoned the instrument and began to disport with the two English spaniels he had given her in Paris. They fell into serious conversation about themselves, Paget ardently pressing his suit the while, speaking of Adrianople and what he could offer her there; the embassy, he said, would ordinarily bring him a title and rank worth while. The whole gay world would be theirs to enjoy. It was a pleasant vista, and he kindled to it, though she did not. Then, as she leaned over to pet the dogs, the chain and emerald fell from about her neck. He picked it up.

"THE clasp is worn and unsure; it needs a new one," he said. "Why so handsome a chain for so poor an emerald?"

She laughed merrily at him. "And you a connoisseur of jewels? For shame! This belonged to the great Richelieu. When he died, fifty years ago, he bequeathed it to his niece, the Duchess d'Aiguillon. She was a great friend of our family. She was in Rome shortly before her death, in '75. I was a babe of three then. One day she slipped this about my neck and said it would bring me luck."

Then she must be twenty-two now, thought Paget.

"I still think it a poor stone," said he.

"Indeed? It is a most wonderful emerald!" she exclaimed indignantly. "It is the chiefest of all my treasures. Did you never hear of the Sphinx emerald?"

"Oh! Impossible!" said Will Paget. He had indeed heard of that almost legendary stone. "Are you in earnest? Let me see it again."

He took it from her. "Hold it to the light," she said. "Sometimes I sit gazing into it by the hour, with a glass. It is enchanting! Cellini, they say, made the chain; but no human hand could have made that emerald."

With keen interest, Paget went to the window, slipped from his pocket the double convex lens he always carried, and real astonishment seized him as he looked into the emerald. He had vaguely heard of this stone. He had seen sketches of it made by Leonardo da Vinci. The court painter Clouet had pictured it in a portrait of François I, who had owned it—and here in Leghorn the legend had come true!

Of good size, a wretchedly cut cabochon of only fair color, it had obviously come from the lost Egyptian mines—erroneously called the mines of Cleopatra, for this emerald had been famous long before the little queen. Like all emeralds, it was full of flaws. But unlike any other known emerald, the flaws in this one had assumed a shape, that of the Sphinx, crouching within the heart of the gem. It was not fancy, but a perfect and exact image.

What was more, the dispersal of colors was extremely odd, and since the emerald or beryl is a six-sided prism in form, the double refraction was uniaxial. Perhaps this, he thought, accounted for the singular things he saw in the jewel—things that were not there at all. His imagination was stirred uncomfortably. The Sphinx was real enough, but he fancied a grotesquerie of mocking, jeering faces in the play of greenish light, in the enlarged field of glittering green beneath the lens. Or was this caused by the bubbles? Like most true emeralds, this one contained microscopic bubbles, not round but angular in form—something that not all man's science has been able to duplicate. These, he thought, might somehow be responsible for the odd mental effect caused by the stone.

He was not aware that, while he thus stared, fascinated, Flavia di Leone was watching his face, almost with equal intentness. The look in her eyes was half amused, half sad. She fully understood the amazement, the absorbed emotion, of the man. He had never looked at her like this, for all his passion. Here was the real man laid bare to her gaze, and it saddened her, perhaps, to read him so accurately, to know that he had all in an instant utterly forgotten her existence.

Yet when he looked up and started slightly at sight of her, she was smiling.

"You too?" she murmured. "It does that to everyone—makes them see things, some good and some bad. Some hate the stone, others would give their very souls for it."

He put away the glass and slipped the chain over her head. A lovely head it was, massy with golden glittering hair; her face was like fair satin and sweetly carven, all alight with deep allure. Yet the blue eyes were hard and cold—eyes that did not warm as a rule, or kindle to pretty words. A haughty woman, who would follow her own impulses regardless of anyone else, a woman of strange loves and intense hates. Paget wondered at himself, thus estimating her, as though weighing her for the first time. The things he saw in the emerald must have done this to him, he thought half angrily.

"A wonderful gem, yes," he said quietly, "but it is poorly cut. You should—"

"No!" she cut him short. "It stays as it is. It is mine," she replied. The phrase made him think of Hassan the lapidary, and he smiled a little.

"Are the things we love ever ours, Flavia? Beautiful things—can we say beauty is ours alone, even impersonal beauty like gems?"

"Of course." Her voice sharpened a trifle. "My jewels, at least, are mine and ever shall be. I intend that this emerald shall be buried with me, some day—"

She broke off abruptly as the Vicomte de Tournelle came into the room and advanced toward her.

He was attired in cut Genoese velvet of steel blue adorned with seed pearls—a trifle worn and shabby, to a keen eye, but still magnificent. He was commanding in feature, darkly handsome, with thin, pallid lips and veiled eyes which, when wide open, revealed the whites below the pupils—sure sign, to Will Paget, of a cruelly hard and bitter dominance. And yet the man radiated charm. The very room warmed and glowed to his presence, reflecting the magic of his personality. He was the sort of man to make the sunshine brighter on a fine day like this.

For Will Paget, it was a cruel moment—as though he were still seeing unseen things and had been given an insight into realities by those visions in the emerald. Tournelle took Flavia's hand, kissed it, and stood beside her with fingers touching her gleaming hair as in quiet caress. He was sure of himself, sure of her, wearing the easy air of possession. And she reacted to it, warming and glowing like the room itself, feeling his presence happily, glad of it, rejoicing in his nearness. She loved him.

Will Paget saw all this quite clearly. Perceiving it, he knew that he would never win her, that Tournelle had already won her. A slight sigh escaped him, as he made up his mind to it. He never played a losing game.

"I must be leaving. Business awaits me," he said.

"The carriage—" she began. He checked her.

"Thanks, no. I prefer to walk." He glanced at the Frenchman. "You like Leghorn, M. le Vicomte?"

Tournelle showed white, even, pointed teeth like a cat's, as he laughed.

"Faith, monsieur, it promises to be very kind to me! I am unlucky at cards, lucky at love, and money seems easily come by here. A pleasant place indeed!"

"My congratulations," Paget said, dryly. He disliked Tournelle with all his heart, and when their eyes met, he knew the man cherished an equally vivid dislike for him. But each of them remained superficially amiable, friendly, courteous, apt at the conventions of good breeding.

They exchanged bows. Paget kissed Flavia's hand, most un- Englishly, and she bade him to an early family supper the next evening—a kindly invitation, graced with the kindliness of dismissal. Paget sensed this in her words, her manner, her sad cold eyes. She was letting him down easily, preparing to have done with him and his suit. Her fingers touched those of Tournelle and curled about them lovingly. Paget, accepting the invitation, departed.

PAGET had been granted a wonderful experience and realized it;

that emerald had done things to him, roused him to himself. It

was characteristic of him that, as he strode the broad, straight

avenue to the central square, he forgot his chagrin, forgot his

dislike of Tournelle, forgot the lovely face and figure of Flavia

di Leone. The Frenchman had won, and that finished it. Will Paget

was too bluff and sensible a man to throw himself away on the

coast of folly. His argosy was too soundly freighted for such

nonsense; his grip of the helm was too firm. He felt no grief at

all, and it came to him that he was not and never had been in

love with her—he had merely been pursuing the wisp of an

ideal.

What did grip his thought and his mind and his soul was that bit of beryl he had looked into. The emerald had completely captured his imagination. He was obsessed by it. And she thought it was hers! This made him laugh softly to himself.

Little could such a jewel belong to any woman, however beautiful. So glorious an object, an unique thing of nature's fashioning, could have nothing in common with any petty human being made for worms. It spoke with allure to mind and spirit; it was something far beyond the mere empire of the physical. Within those green depths lay all the realms of the imagination; how might any person declare this wonder his own or her own? It was absurd. That queer fellow Hassan knew what he was talking about.

"Buried with her, eh?" reflected Paget. "As though that would make her own it! Oh, plague take all such nonsense! What's this?"

Thought of Hassan the lapidary sent his fingers to the parchment in his pocket. He drew it forth, opened it, and began to decipher the crabbed writing of it.

A WHILE later, Waynflete and some of his cronies among the

English merchant colony were gathered about cups of chocolate,

when Will Paget broke excitedly in upon their company and flung

the parchment on the table.

"Read it, Roger—read it aloud!" he cried. "Either it's some monstrous hoax or—or by gad, here's fortune within our grasp! Read it out, man—see what you think of it!"

They complied. Their first puzzled wonder became incredulity; then, when Paget told how he had come by the parchment, passed into fevered heat of cupidity. It was no hoax, no delusion. Here was a five-year concession of the whole trade of Corfu and Zante, granted by the Council of the Venetian Republic to "Hassan the Lapidary, called El Maghrebi, or to his assigns." The trade of those two Greek islands, which Venice owned, meant not one but a dozen fortunes, over a five-year period.

The chocolate-sipping assembly became a business session prolonged far into the evening. Signore Mocenigo of the great Venetian house was visiting with the Venetian consul in the city. Paget and two others were sent hot-foot to see him. The bona fides of the document was promptly verified by Mocenigo.

Hassan, it appeared, was really a Moroccan prince in exile, and a master genius of eastern Mediterranean trade, having friends and informants everywhere. He had rendered Venice most important services in commercial lines, and had been rewarded by the Council of Ten with this negotiable document.

The gathering at Waynflete's house canvassed the matter thoroughly. Two thousand of the Florentine forty-soldi coins for which the great Cellini had made the dies in 1535, was really something; but among so many wealthy merchants they could be supplied, even at short notice. There was sharp discussion, and the company adjourned to meet again upon the morrow, after further thought and investigation, with Signore Mocenigo.

WILL PAGET forgot emerald and woman alike. Here was something

solid for a merchant's jaws to clamp upon, something real, with

incredible profits involved! When, on the morrow, Mocenigo met

with the company, he gave them full assurance that the

concession, when endorsed over to them by Hassan, would be

ratified by Venice. This Hassan was a person of far-reaching

influence in both diplomatic and commercial quarters, an

excellent man for any ambassador to know. Will Paget was glad to

be deputed to see Hassan this same evening and close the deal,

payment to be made on the morrow. Although exiled, Hassan was no

less an agent of Sultan Ismail, it appeared.

So that afternoon the company of Zante traders was formed, each merchant sharing according to his investment. Paget, being a wealthy man, took a large share. He was in fine feather that day, talking shares and gold exchange; and upon sending a messenger to Hassan, was asked to visit the shop of the lapidary later in the evening.

Everything fitted in very neatly, and Will Paget set off for his early supper engagement with a highly contented heart. Romance was really not worth its cost. He was a methodic sort of man, and having made up his mind to the loss of Flavia, he was able to rid himself of his hapless passion with no particular difficulty. Still, as a final ember of the quenched flame, he took with him as a gift for the lady a gem that he considered a natural curiosity—a stone he had procured the previous year from a Muscovy trader. What it was he knew not, but cut and polished, it was very pleasing.

Truth to tell, he was more anxious to see the Sphinx emerald again than he was to see the fair Contessa. It had been a busy day.

Bidden early, he reached the villa with daylight still in the sky, and was shown to the garden. The Contessa, said the man who admitted him, was there. Paget strolled about but saw no sign of her until he perceived one of the spaniels playing about the entrance to a little summer-house thickly overgrown with roses, at the garden's end. He was approaching this when the sound of a voice came from it—a furious voice so charged with angry oaths and passion that it stopped him like a blow. It was the voice of Tournelle, with its usual suavity ripped away.

"But you shall and you must! I'll brook no refusal—you must!"

"Not at all, my dear Louis." This was Flavia speaking—angrily too, but quite calmly. "If you need money, I can always supply—"

"Listen to me!" Tournelle burst in upon her. "This is a fortune, do you understand? A fortune! And that cursed green jewel is worthless. You're infatuated with it, you vixen, but you're going to learn that I'm master here."

"Louis, you forget yourself." Cold was her voice now, cold with an anger greater than his, an anger deep and piercing and charged with finality. "No, now and forever! The jewels are mine, and stay mine. You ask the one thing I cannot and shall never give you. Understand it once and for all—"

Will Paget, embarrassed and scrupling to be an eavesdropper, scuffled the gravel path and whistled to the spaniels. The voices ceased.

Presently Flavia appeared. Except for her bright eyes and high color she was quite herself, greeting him with unusual pleasure and intimacy. Tournelle followed her out. He was white to the lips, and replied curtly to Paget's bow, then strode away almost discourteously. Flavia uttered a soft laugh and took Paget's arm.

"You must pardon our Vicomte. He has just received a great disappointment, and it has stricken him."

"Then I would that his chagrin spelled my happiness, dear lady," he replied gallantly, making a final futile effort despite himself. His eye went to the emerald, which she wore upon its chain. "Why not leave him to the consolations of Rome, and take the road to Adrianople with me?"

Flavia looked at him for a moment, then took his hand and pressed it. The look in her eyes was that of yesterday—half sadly compassionate.

"Because you are chasing butterflies, and take the chase to be love," she said. A sudden impetuous warmth filled her voice. "Honest Englishman, I like you. So, for one little fleeting instant, I shall be honest too, and confide a secret to your honor—a real secret, unknown to any here. Louis and I were married just before leaving Paris. Pardon me for not telling you sooner."

Will Paget turned, looked into her eyes and saw their candor, and forced a smile. The blow hurt his pride—a trifle—but certainly not his heart. He realized how he had been swept away by passion, not by love—chasing butterflies, indeed! Still holding her hand, he bowed and kissed her fingers.

"Contessa, far from causing hurt, you can bring only joyous happiness to those around you. I respect your confidence. I felicitate you with all my heart, wishing you the greatest joy. Let me be the first to place a wedding gift in your hand."

So saying, he laid in her palm the strange olive-green stone he had bought from the Muscovite. She looked at it, turning it over curiously, and her eyes lit up.

"Thank you, indeed! It is a singular gem, like none I ever saw. What is it?"

"Nay, ask me not, for in truth I know not," he confessed. "In terms of the trade, it is doubly refractive and biaxial, and ranks in hardness above spinel. By this and its qualities of refraction, I believe it to be a species of chrysoberyl, but it has a striking and mysterious quality which you'll observe during the meal. I never before saw such a gem; like your emerald, it is unique. Therefore accept it with my humble compliments, I beg of you."

"You are kind. I shall cherish your memory in the gem," she murmured, then took her gaze from the translucent olive-green stone. "But it's growing chilly here—shall we go inside?"

THEY passed into the house, talking of jewels as they went,

the spaniels frolicking about gayly. Tournelle met them. He was

entirely himself again, witty and radiating his peculiar charm,

apparently quite at ease with Flavia and the world.

Paget watched the man cynically, giving no hint of his secret knowledge. Had the Vicomte been trying to force her to hand over her jewels? However, it was no affair of his. He seated himself at the harpsichord, sang a tender ballad, and began to feel extremely happy. If Flavia had chosen such a rogue instead of him, he thought the worse of her for the choice, that was all, and was well out of the business.

The supper was much earlier than the usual Italian custom. They sat at table with two huge silver candelabra lighting the room, and as they talked and ate, Paget indicated the Sphinx emerald on its chain.

"Will you permit me a word of advice?" he said to Flavia. "That emerald has poor color and is very badly cut. But in its heart is a spot of deeper color which a cunning craftsman could bring out, without spoiling its unique features, and thereby improve it vastly."

"Perhaps, but it shall never be done," she said, most decidedly. "It shall remain as it is; not for anything would I have it altered. I care nothing for its value. Almost all my patrimony is sunk in jewels, which will suffice me all my life. I shall never part with them—with any of them," she added. Paget fancied that for an instant her eye flicked to Tournelle with challenge. "They are mine, mine! Mine to enjoy and keep sacredly, as I shall keep this gift of yours."

She produced the curious stone he had given her, and told the Vicomte of the gift. Then, while still speaking, her voice died away. She was looking at the stone, and her gaze widened upon it with startled fright. For the gem, which out there in the garden had been a beautiful soft olive-green, now shone in the candle- light with a rich pigeon-blood red, vivid and striking.

Paget smiled. "The mysterious properties I mentioned, Contessa—you see? That is the peculiar and unique feature of this stone. In ordinary daylight it is a lovely green, limpid and serene. But in the sun's rays by artificial light, its color changes to a deeper red than any ruby. Why? I cannot say, alas! The Muscovite from whom I had it believed the gem to be bewitched. But beauty is never a thing of witchcraft, so wear it and fear not."

The marvel of the stone led to further discussion of gems. Tournelle, who had never previously shown much reaction to the subject, betrayed a keen interest, and made himself more than ever fascinating. At the back of his mind, Will Paget wondered. Had the Frenchman known that all the Contessa's fortune lay in her jewels? And had he been trying to get them from her, there in the summer-house? An odd situation, thought Paget, and no promising one; he found himself cherishing a keen distrust of the Vicomte, and was rejoiced when he could take his departure.

He needed no escort, as he headed downtown, for Leghorn was the one Italian city that was well and efficiently policed. As he walked, the chill night air off the sea cleared his brain and sent him looking eagerly ahead to the important meeting with Hassan.

Flavia and her jewels were brushed out of his existence and thought, and with them the Vicomte de Tournelle. Chasing butterflies, eh? A very apt figure of speech. Well, he was back to solid things again, and deucedly glad of it. Sir William Paget, egad, had better be looking to his affairs!

It was just as well for Will Paget's future peace of mind that he attained this eminently practical viewpoint when he did.

He found the little shop of the lapidary lighted but curtained from the street. Hassan awaited him, and a black Sudanese slave served them delicious mint tea. The Moor was not only affable but friendly, and showed himself amazingly frank.

"Certainly, the concession might have been sold for much more," he said. "But I was urgent for cash, and that in gold. By making it worth your while, I gain all that I desire—what more could I wish?"

The simple arrangements were quickly settled. The gold was to be delivered by noon next day; on this point Hassan was adamant.

"My word is pledged; I must have the cash by noon," he said. "You, Sir William, are an ambassador, a man of honor; you comprehend the nature of engagements which must be met on the dot. In this instance, it means a return to my own country, to life in a palace, to everything I once had and lost. True, it is the will of Allah, but this is largely dependent upon my own efforts."

Will Paget liked this sentiment. "Agreed. The gold will be here before noon."

"The concession, signed over to you and ratified by the Venetian consul, will be awaiting you," said Hassan.

Will Paget liked this, too. All clear-cut and businesslike. Sipping his mint tea, he noticed loose gold strewn along the work-bench and voiced a question.

"Are you a goldsmith also?"

Hassan laughed. "A very poor one. I have been making the setting for the great jewel to be presented to the Sultan Ismail. To please him it must be made just so. Look."

He produced a massive golden circlet, a ring designed to hold a single stone. Paget examined it critically with the eye of a master goldsmith.

"Virgin gold, and soft, eh?"

"Pure dust from the Sudan. You like the work?"

"No," Paget replied, honest as he ever was. "It is far too crude, too heavy."

"By design," said Hassan. "Ismail has no use for delicate things. He is very active, uses spear or sword every day; what is crude, impresses him. Thus, you will observe that the claws to hold the gem, seemingly so large, are meant to protect it from breakage."

"I see you know what you're about. And where is this wondrous gem?"

Hassan smiled. "It is not yet in my hands, but it will come. It must be worked over and re-cut before I can mount it."

Paget indicated an inscription in Arabic letters, inside the circlet, asking what it meant.

Hassan chuckled.

"That means: 'El Maghrebi made me.' It is to keep Ismail reminded whence the ring came; his favor is a fickle thing. By the way, within the next few days I expect to have some very handsome jewels, if you care to see them. The prices, to you, will not be high."

Paget was tempted, but resisted.

"I shall not be here. I have tarried too long already, and must resume my journey immediately this business of ours is closed."

The Moor nodded. "An ambassador does well to confine himself to his work. Perhaps your greater wisdom may instruct me in one or two matters."

They talked of trade and politics. Will Paget found himself utterly amazed at the shrewd conceits and deep knowledge of this graybeard Moor. He learned much regarding the Turkish policies of Adrianople and the Orient trade in general—so much, that after going home he instantly made notes of all Hassan had said and hinted. Indeed, he learned more from this half-hour's chat than from six months of big-bellied discussions with Foreign Office bigwigs in London; and these notes he made were largely responsible for the surprising address and sharpness which Sir William Paget was so soon to display in managing affairs at Adrianople for the Turkey merchants of London.

NATURALLY, Will Paget now had greater things to dream about

than Roman blondes or emeralds; romance, in fact, was for the

time being completely driven from his mind. Next morning saw the

Zante Company gather and the broad gold-pieces pour in. Somewhat

before noon, Paget and others of the company escorted two stout

mules loaded with treasure to the little shop of Hassan the

Lapidary. They were very fine white mules and therefore unusual;

Waynflete had loaned them for the occasion, since such a weight

of gold could scarcely be carried in one's waistcoat pocket.

The Venetian consul was waiting; the papers were duly made out and attested; and the concession became the property of the new- formed Company of Zante traders. Hassan made no count of the money, accepting Paget's word for this, but requested that the mules and treasure be left with him intact. To this Waynflete objected somewhat heatedly until Paget agreed to recompense him for the mules. The merest detail and of no importance whatever, thought Paget, but was to change his mind about this, ere long.

That afternoon Will Paget had to arrange his immediate departure for Adrianople via Venice and also had to preside over a merry banquet of the Company of Zante. Signore Mocenigo was present as a guest. Since he was leaving at noon the next day for Florence and Venice, he invited Paget to ride in his coach, promising to send him on from Venice to Stamboul by ship. Will Paget accepted this civility most thankfully, rightly counting on securing from Mocenigo, en route, an excellent grasp of Venetian trade affairs in the Orient.

So, what with one thing and another, we see Will Paget the gay Lothario and searcher after Continental pleasures, once more the stolid, practical London merchant bound for diplomatic triumphs and well satisfied with his lot. The morning of this his last day in Leghorn, however, he was greeted with news that left him horrified and profoundly shocked. He learned of it after breakfast, upon going with his host to the counting-house. The whole city was ringing with it by this time.

Flavia, Contessa di Leone, was dead.

Early the previous evening she had taken carriage to drive to a gambling casino in town which she had visited now and then. She never arrived there. Toward morning the wreckage of her carriage had been found on the highway north of the city. Evidently the handsome grays had run away, smashing at last into a tree. Her body was found in the wreckage; that of her coachman was strangely missing, and the man had not been found.

While Waynflete and Paget were drinking in the details of the story, an agent of police arrived. A mere conventional questioning of the English milord, he explained, Paget being known as a friend of the Contessa. Paget dazedly answered the questions asked him; he did not waken from his stupor of horror until the agent was departing, then halted the fellow.

"Where—what about the Vicomte de Tournelle?" he stammered. "Where is he?"

"That, excellentissimo signore, remains somewhat of a mystery, since we cannot find any trace of him," replied the police agent. "A man answering his description was seen on the highway during the night, riding a horse and leading two white mules, but by this time he must have passed the Tuscan boundary. It is all very puzzling."

So it was to Will Paget, too. Mention of the white mules plucked at his brain somewhere, but he remained bewildered. Finally he roused from his stupor sufficiently to start his man getting packed, and while he was engaged at this, a messenger came from Hassan the Lapidary to say the expected stones had arrived and the signore might come at once if he desired to view them.

Paget jumped at the chance to get pulled out of his melancholy. It was more than an hour before Mocenigo's coach would come for him; ample time, therefore. He clapped on hat and riding-coat and walked along the colonnades to the little shop of the Moor, and went in. Hassan greeted him brightly, set aside his work, and unrolled a mat of black velvet before him. Upon this he heaped a double handful of gems.

"Most of them are unset, or were broken out of their settings," he said. "You shall see them just as I received them."

Paget began to finger the jewels, but his mind was not upon the task. Most of the stones had indeed been wrenched from their settings; to some of them still clung bits of the gold in which they had been mounted.

He was conscious of something growing within him—a certain nameless sense of horror for which he could not account. None of these jewels were familiar; yet from the mass leaped out a color, now and again—a bit of olive-green. He reached for it, lost it amid some rose-pink pearls, saw it and lost it again, then resolutely turned over the pile. There it was! He picked it up with shaking fingers, and carried it to the front window, where the sunlight struck in briefly. He held the green gem in the sun's rays; not that he did not recognize it instantly, but he was incredulous. He needed to verify the thing to his own numbed intellect.

And as he looked, the stone, limpid olive-green an instant before, turned in the direct sunlight, as it did under artificial light, to a rich red.

Horrified conjectures rushed upon him as he looked: The man with the two white mules—Hassan, who had needed the gold to pay for the gems he had expected—the woman who had died the previous night in the wreckage of her carriage! A choked cry burst from Paget. Madness burst in his brain. He turned, hurled the chrysoberyl at the Moor, and went headlong out of the shop.

There, in the street, he pulled himself together. Sanity came back to him. Tournelle was gone. He had no proof whatever of the crawling horror that seized him at thought of it. He had best get out of here, out of Italy altogether, at the first possible moment, and keep his mouth shut. For Sir William, there was no alternative.

WITHIN the shop, Hassan stared after him, and shrugged. Going

back to his workbench, the Moor seated himself and uncovered the

work upon which he had been engaged. Before him was an emerald,

poor in color and wretchedly cut; but when he had finished re-

cutting the stone, its loss in weight would be nobly repaid by

its gain in shape and color. He looked from it to the massive

gold ring for which it was destined—the ring of Sultan

Ismail—and nodded complacently.

Then, as he fell to work once more, a chuckle took hold of him, and his thin lips twisted in a mirthless grimace.

"That Englishman must be a little mad after all, like most of his race," he muttered. "Allah is great; Allah is good; He alone bringeth all things to perfection! And she thought they were hers! Blessed be Allah—she thought they were hers!"

He cackled out a laugh, and went on with his task, contentedly. And Sir William Paget, fleeing the truth he dared not face, went on to Adrianople and the high destiny there awaiting him.