RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

RGL e-Book Cover 2018©

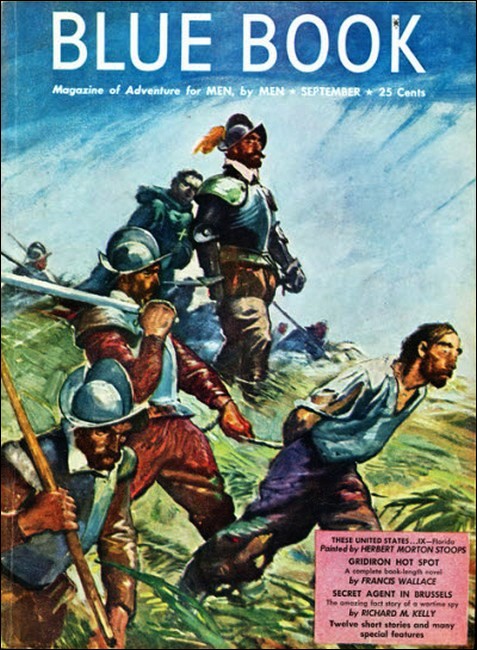

Blue Book, September 1947, with "Lady in Chain Mail"

From the hand of a dead Mameluke after the battle of the Pyramids, a civilian scientist with Napoleon's army took the Sphinx emerald…. and though the Mameluke's militant daughter offered to buy back the gem at a price high indeed, swift tragedy followed.

FABRE twisted the ring from his finger and held it aloft, laughing, so that the sunset rays struck a green spark from the stone in it.

"The emerald of Ibrahim Kachef Bey, comrades!" he exclaimed lightly. "Look well at it! Today the Corsican himself offered me ten thousand francs for it. I refused."

The other two men received his careless words with grave concern. Duroc the geologist, a rocky-faced cynic of forty, spoke out in his blunt way:

"A mistake, Pierre. You might have built your fortune on that ring. Bonaparte is an Italian; he cherishes a grudge or a rebuff. And the General-in-chief of the Army of Egypt can be a bad enemy to a mere member of the Commission of Arts and Sciences."

"That's true," assented Bonnard, the historian. He was an elderly man, sad-eyed, burned-out, suffering with a liver complaint; a kindly fellow. "The ring cost you nothing. You took it from that dead Mameluke Bey at the Pyramids battle. Sell it. What good is it to you?"

"None, perhaps, but I'm fond of it." Fabre regarded them with a glint of mockery in his stubborn dark eyes. "Yes, I'm in love with the emerald. And that woman sent again to me this morning, wanting to buy it back, asking for an interview. The dead Mameluke was her father, Ibrahim Kachef Bey. I'd like to see her. Who knows? Anything's possible here, where our Corsican has become a sultan preaching the creed of Islam! She may be young and beautiful, eh?"

His words drew laughter and nods of comprehension.

"I don't blame you," Bonnard said. "It's a young man's war, so make the most of your chances, by all means."

"You're a lucky devil, and I envy you," put in Duroc, giving his ferocious mustaches a twist. He was really the tenderest of men, and the mustaches pleased him by lending him an entirely false air of bloodthirsty aggression. "The stone is marvelous, absolutely unique. And historic as well. Let me see it once more, will you?"

THE three were sitting in the coolness of sunset, in the

garden of their small requisitioned house just off the Ezbekiya,

where the palaces of the Mameluke Beys were now occupied by

Bonaparte and his various headquarters staffs. This was a

pleasant little house and garden, redolent with orange trees; and

these three men, who wore no uniforms, were in luxury—the

luxury of conquerors. They were not, most distinctly not,

fighting men.

They were members of the Commission of Arts and Sciences, a hundred and seventy in number, summoned by Bonaparte from all the savants of France to accompany the Egyptian expedition. Pierre Marie Fabre was a minor member in the department of native manufacturers. In the fighting before Cairo was taken, when savants shouldered muskets like common soldiers, and everyone was looting the gorgeously arrayed Mamelukes, he had obtained the emerald ring from one of the dead cavaliers—no less a person than Ibrahim Kachef Bey, as he had since learned.

That had been in July. Now it was October, and easy conquest and loot had shattered the morale of the expedition. General Menou, father of the Tricolor, had turned Mohammedan and had established himself at Alexandria with a choice harem; Bonaparte purred to his native title of Sultan el Kebir. Cairo was plundered of Mameluke weapons and curios and treasures. But the emerald ring obtained by Fabre was the prize of all. The emerald was not large and was of poor color, but it was unique.

Duroc and others who knew precious stones had established that it was the Sphinx Emerald, a stone famed from ancient times, figuring in history and romance. Now, in the red sunset, the geologist took the ring, held a lens over the stone, and stared into its heart. He was openly fascinated by what he saw. His features changed and softened; his hard eyes warmed; he spoke almost dreamily.

"Richelieu, the great Cardinal, once owned this stone," he said. "He willed it to his niece, the Duchesse d'Aiguillon—and then it vanished. That was its last appearance; what became of it has never been established."

"I've read of it," said Bonnard, taking the ring and examining it with great attention. "Look! Here inside the circlet is engraving, nearly effaced!"

"I know. It's Arabic. Marcel translated it for me," Fabre put in. "It reads: 'Hasan el-Maghrebi made me'. Some goldsmith in Morocco, evidently. The work is very crude. It's a hundred and fifty years since Richelieu died, so the stone must have gone from France to Morocco, thence here to Egypt. Pity it can't speak and tell its story."

"It does speak, though not in words," said Duroc. "A man could lose his head over the emerald. Any woman would, assuredly. No one seems to perceive the same things in the stone, either. Wonderful!"

"Not at all," said Bonnard. "I can explain it quite simply."

HE puffed at his pipe for a moment.

Then he began to speak, telling that the unique feature of this stone, which must have come in ancient times from the emerald mines in Upper Egypt, was the flaw that it contained. A flawless emerald seldom or never exists. In this stone the flaws were many; when examined under a glass, or even to the naked eye, they took on the aspect of the Sphinx in profile. It was no mere fancy but an exact duplication—startlingly exact, one of Nature's curious quirks.

"The riddle of the Sphinx is no secret," the historian related. "It represents the Mind—that unknown, wonderful, inexplicable thing we call the Mind. Here in this bit of green beryl we behold a Sphinx amid green fields and hills and landscapes. To some, it is amazing and fascinating beyond belief. Others find it repellent and repulsive. Others find in it a beauty so poignant, so exquisite, that it moves them to tears. Why is this? Because, like the Mind itself, it conveys a sense of the beautiful, the evil, the slippery and evasive—such is its appeal to the human imagination. Each one beholds in it some quality of his own mind. It speaks differently to each."

"The General," said Fabre, "declared that it spelled fame and glory."

Duroc uttered his raucous laugh. "To the Corsican, the greatest thing in the world, the only thing worth while, is glory—his own, of course. The Mameluke woman who pursues you, Pierre—why does she want it?"

"Her messenger said it was a talisman, a good-luck charm, which her father had received from his ancestors."

"Precisely! Any woman would go insane over the stone. Beware of her, I warn you! The Arabs believe an emerald renders all magic powerless. But beryl does have some curious properties—electric, for instance. The sixfold character of the crystal has an extraordinary effect on the refraction and light dispersion—"

THE discussion was interrupted by the arrival of an aide from

headquarters with orders for Fabre. He opened the sealed sheet,

headed with the vignette of the Commission. He was ordered to

leave Cairo in the morning with an escort of six men of the 12th

Light Foot, and to proceed to the village of El Bakri, some miles

to the east and south, there to make an exhaustive report on the

manufacture of qulla jars, for which the place was

renowned.

There was nothing unusual in this order. The Commission was composed of writers, sculptors, mathematicians, chemists, men of all the arts and sciences; its purpose was to prepare for the colonization of Egypt and the utilization of all its resources. Already the members were being scattered over the whole country on various missions; powder factories were being started, and commercial objectives of all sorts were under way.

"Well, I'll be glad to get away for a while," commented Fabre. "But what in the devil's name are qulla jars?"

Bonnard chuckled. "They're the porous water-jars used everywhere in Egypt, made by a secret process. I believe their amazing porosity is gained by mixing certain ashes with the clay. It's an enormous traffic. The people of that village have a monopoly on the manufacture—the jars aren't made there in mass, but the villagers go out and take charge of the various factories, as experts. You're lucky to get away; things are shaping up for trouble, here in the city."

Duroc's laugh cackled, agreeing. "Didn't I say the Corsican was a bad enemy? He knows well enough a revolt is coming, and hopes for it, to establish his own authority in blood! It'll suit his purposes. What's it to him if all the Frenchmen not in barracks here get their throats cut? This is your reward for refusing him the emerald, Pierre."

"Absurd! He's too great a man to be so petty—"

"Great? Bah! You're a young idealist, full of wind and fine theories," Duroc said acidly. "The Corsican is out for himself, first, last and foremost. At Toulon, a soldier beside him was struck by a cannon-ball, drenching him with blood. It gave him the itch, and he's had it ever since. That's why he always sticks a hand inside his coat, so he can scratch his chest. It gave him an itch for glory, too, at anyone's expense—"

In a burst of laughter, the three broke off their discussion and went in to dinner. Nobody in the expedition had any illusions about their leader.

True, Pierre Marie Fabre was young, barely twenty-three, but this was an era of youth. In the six-year-old Republic, all the young men had come to the top. Darkly eager, impetuous, thin- nostriled, Fabre had plunged into the Egyptian adventure like the rest of them, careless of consequences, enthralled by the glamour of it.

His family, a wealthy manufacturing one of Lyons, had been swept away in the Revolution. At the general amnesty he had returned, alone, to build up his career anew. A friend had got him this place, as an expert in manufacturing, and he was building his hopes on the issue of the expedition, which promised fame and fortune to all concerned. But youth was a perilous thing in this army of conquest, just the same.

He had been far from frank with his two comrades. Not only had he been in touch with Amina, the daughter of Ibrahim Kachef Bey, but he had an appointment to visit her this very evening, on the business of the emerald ring. A slave was to pick him up here and conduct him to her house. Where it was, he had no idea; not far, since it was one of the lesser Mameluke palaces, and these were all grouped nearby.

Risky, of course, and therefore all the more attractive. Hatred for the French was mounting to fever heat in Cairo, fanned white-hot by Turkish agents; tension was increasing, and Bedouins by the thousand were said to be quietly flooding into the city to augment trouble. Any revolt must be a bloody affair, since most of the army was off on detached missions or quartered in barracks outside the city.

THE situation was not helped by the avidity of everyone, from

the headquarters staff down, for wine and women. Blondes were no

rarity here. The Mameluke ranks had for generations been

recruited from Circassian, Georgian and other slaves of white

skin, while the Arabs themselves were white as anyone. So the

army was hugely enjoying itself, careless of any future

reckoning. Yet, as Fabre well judged, a reckoning was

imminent.

When, at the appointed time that evening, Fabre stepped out into the street, he was shaved and spruced up hopefully, hat pulled over eyes, and long green riding-coat buttoned to the chin, a small pistol in his pocket and a stout silver-headed cane in hand. A dark figure awaited him—the Kachef slave, a pleasant brown fellow who spoke French. They set off at once, the slave leading the way. Fabre had no fears whatever. The unknown lady had sent an oath upon the Koran that he would have safe- conduct, and he believed her.

Dimly lighted, tortuous narrow streets, strange speech and shapes on all sides, carven cedar balconies overhead echoing with voices, drunken soldiers singing, Nubian flutes and drums making unearthly noises, intent crowds around story-tellers and magicians, lighted mosque-entrances hinting at mystery; tiny open-fronted bazaars thronged with buyers—all very glamorous, no doubt, but Fabre could sense the burning hatred in Turk and Arab eyes as he passed. It troubled him little. These were the conquered; he was of the conquerors, whose artillery yawned from the towering citadel above. These people needed a hard, sharp, bitter lesson of blood that would properly cow them, and they would get it if they gave the Corsican the least excuse.

Fabre and his guide came to the house. Stables occupied the ground floor—to the now vanished Mameluke cavaliers, horses had been a large part of life. Fabre was led into a dimly lighted courtyard and garden, from which stairs mounted to the upper floors of the house, stairs with carven marble balustrades and inlaid cedar screens. On the second floor he was taken into a corridor, and on to a room of some size. The slave took his riding-coat and hat, then left him. No one else had appeared about the place.

Accustomed as he had become to Eastern luxury, Fabre found the room astonishing. Painted beams, cedar lattices, tiled floor and walls, hanging lamps of silver, Persian rugs and pillows, ivory- inlaid tabourettes the shape and size of the huge French army drums, golden dishes of cakes and of sweetmeats, Turkish water- pipes ablaze with jewels—Fabre stood gawking around until, at a slight sound, he turned to see his hostess entering. He bowed.

"Good evening, monsieur," she said in French. "I am Amina, daughter of Ibrahim Bey. Be seated; I am glad to see you."

"I am honored, Leila Amina," he replied, using the Arabic form of address.

She half sat, half reclined, among the pillows. Fabre made a pile of them for himself and sat cross-legged, native fashion. She smiled faintly, helped herself to a sweetmeat, relaxed and studied him.

In return, Fabre studied her; both of them were frankly curious. He noted her reddish hair and very white skin; a thin gauze veil half covered her face; a magnificent Kashmir shawl was looped about her shoulders; and beneath this he glimpsed, to his amazement, the links of a steel shirt that fell to her hips. Noting his glance, she touched the links.

"The daughter of Ibrahim Kachef was trained to bear arms," she said. "I was as a son to him. My great sorrow is that I was not at his side when he fell. You Franks will yet find that I can use my weapons."

"They would overcome us at the first encounter," Fabre said gallantly. "I think the name Amina means radiance. It was well bestowed, lady. Such eyes would put our cannon to silence."

The flattery seemed to please her. Indeed, Fabre half meant his words, for her features were surprising. Her eyes were blue, intensely sharp and bright. While not beautiful, her face, like her voice, was eloquent of strength and character; there was no Oriental languor about her. He could well believe that she could bear arms like any cavalier.

"Since we cannot speak as friends," she said abruptly, "let us talk as enemies under truce, each trusting in the honor of the other, without lies or pretense."

"As you wish, Leila Amina," assented Fabre. "You know my name. I am here as your guest. Must we indeed be enemies?"

"That is for you to choose," she rejoined coolly. "Whether you depart as you came, or stay to make this house your home, is for you to say. You know why I brought you here; it was not for yourself—though you are certainly a pleasing sort of man—but for the ring on your hand. You are here to discuss business."

Fabre blinked slightly. He had anticipated Oriental parley and evasions. He was by no means averse to a romantic adventure, and had rather taken this for granted; but her direct speech and blunt overture, her lack of any preliminaries or small-talk, quite took him aback and left him disconcerted. Duroc, he thought, would have sourly enjoyed this interview.

He put out his hand, and from his finger twisted the ring—a massive, even clumsy circlet of gold, holding the single stone—and held it up.

"Is this so important a thing, lady?" he demanded.

"To me, yes," came her blunt reply. "You have worn it; have lived with it—come, be honest! Do you consider it important, or would you part with it lightly?"

He nodded thoughtfully. "I understand. Yes, I am not anxious to part with it, though many, even our General, have tried to obtain it from me. It's mine, and I keep it."

Her lips curled scornfully.

"Yours? Others have thought the same—my father thought it his. The Moor who stole it from the Sultan of Morocco and brought it to Egypt, thought it his. I say it is mine—whether in my possession or not, it belongs to me!" She checked herself.

"It is really a famous emerald, monsieur," she went on, less excitedly. "Some call it the jewel of desire. It is said that the Prophet Mohammed—on whom be blessings!—captured the shadow of the Sphinx and confined it in the stone. One beholds things in it. The Sphinx is plainly there, other things less plainly. It is a ring of great magic power. It is worth a high price, which I am prepared to pay. I would not lower myself by cheapening it like a bazaar merchant. I must have it at any cost—and shall."

"Oh!" said Fabre. He resented the pride, the dominance of her; the force and directness of her words nettled him. She was not asking, but commanding, as though any bargaining or pleading were beneath her. An extraordinary woman, a most disturbing woman.

"Your father died under French bullets; its magic power did not save him," he said quietly. "I do not believe in magic, Leila Amina. I do like this emerald, and no one can take it from me."

"That too has been said by others," she replied significantly. "You took it as loot, and as loot it may be taken from you in turn. But let us not come to angry words. My purpose is to purchase the ring from you. I presume you're willing to sell, at a price?"

"Frankly, I'm not sure," he made slow response. "It fascinates me. I have refused large sums for it. I like it. Therefore I can understand what it means to you and why you want it." He paused. "Still, I might part with it—to you. Who knows? I don't know yet what you offer, lady."

SHE sat looking at him in silence for a long moment; a

delicate scent of perfume drifted upon the room from her. Fabre

perceived that she was earnest, intent, deadly serious. Somehow

the fact impressed him with singular force, made him realize that

this interview was no light matter, but grave indeed, at least in

her eyes.

"All you Franks, from your General down to your camp cooks, are interested in only two things," she said. "Plunder and—shall I say love? Well, here is wealth." She swept her hand around at the room. "There is more. Ask what you will, and it is yours. Here am I; ask what you will. If I do not please you, there are other women in plenty who can be provided. Your price will be paid. What more is necessary? Give me the ring. You shall have what you will."

Fabre was actually shocked in every nerve as he listened to this starkly realistic offer. Here was no spiced adventure, no glamour, no romance. This girl—for he guessed her to be young—calmly offered her wealth, herself, whatever he desired, in exchange for the ring. It was mere ugly barter; his compliance, his devotion to the grossest material things, was taken for granted.

He flushed angrily. His youthful ideals of romance, his French sense of gallantry, were offended; and in consequence he recoiled where an older man would have considered. His dark eyes sparkled angrily as he made reply.

"You have much to learn about us Franks, Lady Amina. This emerald arouses desire, emotion, makes appeal to the soul; the Sphinx crouching within its heart speaks to the mind and spirit. Can such a marvel be bought like a quarter of beef? Hardly. Beautiful as you may be, desirable as you admittedly are, tempting as might be your wealth, the exchange you propose is a shabby one."

She straightened up, staring with incredulous eyes.

"You cannot refuse! I've offered everything a man could desire!"

"Not at all," he said coldly, perceiving her utter lack of comprehension. "You offer too much, and not enough. You cannot buy things of the spirit with things material. You offer possession, but it is only love that makes possession worth while."

"You are absurd!" She flung back her veil impatiently; her blue eyes flamed. "What you say is nonsense!"

"It is what this jewel says, not I." He tapped the emerald as he spoke. "Nonsense? From your viewpoint, perhaps; not from mine, lady."

She tensed; her muscles gathered; angry passion suffused her face; and for one instant Fabre thought she was about to spring at him. Then, abruptly, she struck the cushions with her fist and relaxed, and even nodded calmly at him.

"Very well, monsieur; you speak like a fool, but I think you are an honest fool," she said, her voice restrained and quiet. "I have still another offer to make. I offer you something even greater, added to the price I have already set before you—the greatest thing of all."

"Yes?" he responded, as she paused. "And what is that?"

"Your life."

He surveyed her, puzzled. "I do not understand, lady."

"We are enemies, monsieur." She lowered her voice. "I want that ring. I must have it! Well, I might threaten you. I might say that I shall regain that ring from your dead hand, as you took it from my father's hand. Instead, I offer you your life. Under my protection it is safe. Accept, and you have nothing to fear."

Fabre smiled. "But my dear lady, as it is I have nothing to fear—"

"Oh, you imbecile!" she exploded almost frantically. "Within three days every Christian in Cairo will be dead! You Franks, all the other Christians here—not one of you remains alive! Is it nothing to you, that I offer you safety?"

He understood, and a chill went through him.

"Nothing." He rose, slipped the ring on his finger, and bowed to her. "Our interview, I think, is ended. I shall not part with the ring. I do not agree with you, Leila Amina, that we are enemies. No Frenchman can accept a woman as an enemy—much less so young and beautiful and gifted a woman. Perhaps we can meet again as friends, and I shall look forward to that happy day."

THE finality of his decision was obvious. She made no

response, except to clap her hands.

The slave who had conducted Fabre hither came into the room, bringing his hat and riding-coat. Amina curtly ordered him to take the Frank safely home. Fabre departed, bowing to her again from the doorway; she ignored him.

He followed his guide back to the little house he called home, fed the slave and dismissed him. Fabre found that his two comrades had gone to attend a meeting of the Institute of Egypt, Bonaparte's pet society formed from the savants and leaders of the Commission of Arts and Sciences. Both Duroc and Bonnard were members. Fabre was not.

FIVE minutes later Fabre was hurrying across the open square

of the Ezbekiya to the palace of Elfi Bey, now occupied by

Bonaparte. The corporal of the guard sent in his name, and he was

conducted to the terrace above the garden. The General and a few

of his chiefs were gathered here—General Dupuy, in command

of the city, Murat, Dumas, Marmont, Reynier, Cafarelli and

others.

"You seek me, citizen?" Bonaparte came up to him. The Republican form of address, soon to be cast aside with the Republic, was still in vogue.

"Yes, Citizen General," Fabre replied. "I learned something tonight of such urgent importance that—"

"Well, then, speak it out!" broke in the scrawny, untidy, sallow little man in his impatient way. "What is this urgent news?"

"It is that within three days the natives expect revolt. Also, a general massacre of all Christians in the city. This comes from a sure source, Citizen General."

The others had gathered around—Dumas, dark mulatto features alive with interest; Reynier, fisting the huge jeweled Mameluke saber he affected; Cafarelli and Dupuy serious and gravely intent. Bonaparte eyed his visitor frowningly.

"So? The city is alive with Turkish agents and English spies. Desert Bedouins are filtering in by the thousand. Stores of arms and powder have been collected. And you imagine all this is news to me?"

"It comes within three days—"

"How do you know this—whence comes this certain information?"

"From the daughter of Ibrahim Kachef Bey."

"She vouchsafed it for love of you, perhaps?" sneered the General.

Fabre flushed. "No, Citizen General. She let slip the words in anger. She was trying to make me part with the ring I had taken from the dead Ibrahim Bey."

"Yes, I remember you and your ring—the magic emerald, eh?" Bonaparte's scrawny features darkened with anger. "You think she let slip the words? Bah! It was done deliberately. These rascals would like nothing better than to learn my plans, my dispositions. Within three weeks, perhaps, will come the revolt—not within three days. I thank you for the information, citizen, but we shall not detain you."

With this cool dismissal, Bonaparte turned his back.

Fabre bowed and departed, stung to bitter anger, but wordless. Let the cursed Corsican think what he liked! Duty was done.

"Obviously, Bonaparte detests me," thought Fabre, hastening home. "He's not forgotten my refusal to let him have the ring. Duroc was right to warn me; I've made an enemy, and a bad one. Well, devil take him!"

Pierre Marie Fabre shared the opinion of many in the army about the Corsican, whose ambition had aroused the fear and hatred of the old revolutionary soldiers of '93. However, upon reaching home he dismissed the whole thing from his mind. Lighting the lamp in the living-room the three friends shared in common, he placed on the table the battered microscope Duroc had brought with him to Egypt.

Even for this day of budding science it was not much of a microscope, being of feeble power, but at least it would enlarge objects appreciably, and this was all Fabre desired at the moment. He placed it beside the light, settled down comfortably to it, took the ring from his finger and placed the emerald beneath the lens-tube.

He focused; now as always, the vision of splendor that opened to his eye made him catch his breath. This fleck of green beryl, cut en cabochon, became a landscape of marvel, shot athwart by the shadowy cleavage of its flaws. Those flaws rose, in the center, into the perfect image of the Sphinx seen in profile—a chance formation, of course, yet exact, even to the forepaws—a vivid green shape in a world of green mirage touched with dazzling pinnacles and points of light.

An uneven landscape it was, with clustering hills and precipices, darker depths, strange shimmering, glowing colors caused by the natural dichroism of the crystal. The minute jagged flaws and singularly angular bubbles characteristic of true emerald became monstrous shapes of dispersed radiance. With every shift of light, one beheld new vistas and glories that plucked at the imagination and swept it afar.

What Fabre saw in the stone, beyond that one stately looming figure of the Sphinx, he himself could not say precisely. Like the splendors seen in dream, these were gone as they came, and left only a sense of intense fascination and gripping illusion. To tear himself away from the spectacle he found difficult, when Bonnard and Duroc returned.

"Hello! At it again, eh?" Duroc exclaimed. "I don't blame you. That damned stone holds a terrific fascination."

"Would you like to have it?" Fabre asked, smiling.

"Name of a black dog! Of course. Who wouldn't? But I've never tried to pry you loose from it."

"You're the only person who hasn't—except Bonnard, there."

"Bah! I wouldn't have the accursed thing; there's evil in it," said the historian, laughing. "What you people find in it, I can't see. But Duroc may cut your throat for it, some night. Well, what news?"

"None that's good. I was warned that the natives expect a revolt within three days, and took the information to headquarters. The Corsican sniffed and turned his back on me."

"Naturally," Duroc snarled. "A revolt is what he wants, to put him firmly in the saddle. He'd turn his artillery on the town, and it'd be something to remember. He'll make himself king here, as he'd be king in France if he got the chance."

"There's always the guillotine for kings, mes amis," put in Bonnard.

"The Corsican is too smart for any guillotine. You'll see! Are you off in the morning, Pierre?"

Fabre nodded. He liked the hard, honest, cynical geologist.

"Look, Duroc," he said impulsively. "This emerald—see? Well, if anything happens to me, you shall have it. I'll bequeath it to you, comrade. Understood?"

"Devil take you, I don't want it at that price! Anyhow, you'll outlive me."

Fabre smiled. "I expect to live a long time, but one never knows. Anyhow, remember it—if the unexpected should happen, the ring goes to you."

The three, with jests and laughter, split a bottle of wine and turned in.

THAT night Fabre dreamed of Leila Amina; at least, she figured

in his dreams, but with morning he could not remember them. Her

gauze-veiled features lingered in his mind; her voice, her

striking eyes, her vest of steel links, combined to make her

memory a vivid thing. He wakened to thoughts of her. Perhaps, he

reflected, he had really been a fool to reject what she had

offered! It was a chance that would never come again.

The party arrived with a spare horse for him—a sergeant and five men, a guide, an interpreter, supplies packed on lead horses, muskets and ammunition and water. Fabre swung up into the high peaked saddle, and with a gay wave of his hand to Bonnard and Duroc, rode away. It was the 29th Vendémiaire, Year VII of the Republican calendar—October 20, 1798.

Unhurried, the party followed the guide to the Bab en-Nasr gate, and out of the city past the Tombs of the Caliphs, taking the road for the Forest of Stone, as the petrified forests among the hills were called. Skirting the Mokattam plateau, they rode to the east and south, making for the hills. Here was open desert, and the sand made slow going.

Gradually they worked in among the hills, whose flanks closed from sight the dome and twin minarets of Saladin's Citadel and mosque. The soldiers, who were unused to horses, groused at everything as usual; the sun waxed high; the heat became terrific. The sense of being lost in the desert hills brought panic; but they were not lost, so the grinning native guide reassured them. Another hour, two hours, would see them at the village of El Bakri, where there was a well of abundant water.

EVENTUALLY they did reach the village. It was a small one with

a copious well, over which leaned a few date-palms. A ruinous mud

wall surrounded the place. Aside from a few naked brats, several

hostile-eyed women and two old men, no one was here. Fabre put

the interpreter to work and learned that most of the villagers

had gone to Cairo for some celebration. Apparently the old men

were entirely willing to talk, so the completion of his mission

seemed assured. Not today, however. The remainder of the

afternoon was given to clearing out several of the mud shacks and

cleaning them for occupancy.

The place was eloquent of its livelihood, Beside every house were vats of mud or clay, with stacks of water-jars, lamps and other household articles, fired and ready for sale. Runways of water led from the well to the village street, handy for the mixing of the clay. The women and children sedulously avoided the visitors, and Fabre warned his men against molesting any of them. That evening he got out his writing-materials, ready for work. A day, or at most two, he reckoned, would see his survey completed. The two old men would be the only sources of information in the wretched place, about which sand-hills rose on every side. The loads were unpacked and stored; the sergeant arranged for a night guard over the horses; and Fabre retired to fight fleas during the night hours. He had no dreams and little sleep this night.

He was up with the sunrise, like everyone else: The lovely pure calm sunrise of the Nile valley, touched with soft lights and glowing electric air—that sunrise to which the ancient race dedicated the worship of Horus. All was secure; there had been no alarms; the grumbling of the men had subsided, and they were trying to make friends with the naked children—but unavailingly.

Breakfast over, Fabre went to work. He settled down with his writing-materials under a sunshade of dry palm-leaves; the interpreter brought the two old men, and the inquiry began. Determined to make it a thorough one, Fabre neglected no details about the mixing and baking of the clay, and information poured from the two elders. Meantime, the horses were watered and taken up the wadi to graze upon the clumps of terfa, the desert shrub used for fodder.

The sun rose high. Fabre wrote steadily, sending the interpreter to select jars from the village stacks, with which to illustrate the various mixtures of ashes and clay described to him. Absorbed in his work, he glanced up in surprise when the sergeant, an old veteran of the Rhine fighting, came and knocked out his pipe.

"Citizen Fabre, will you ask that interpreter what these miscalled females are up to, with their brats?"

"Eh?" Fabre glanced around. He saw that the children were being assembled near the well, at the other end of the village, by their mothers. At this moment the two old men rose, gathered up their voluminous rags, and strode hastily away toward the others. Fabre called the interpreter, who was off getting jars—but next moment everything broke into fluid motion. Women, naked children, and the two old men all went flowing over the ruinous wall like so many rats, and away up the wadi fast as they could pelt. The soldiers and the interpreter shouted after them in vain—they only scurried the faster.

"What the devil are they up to?" muttered the sergeant, staring after them. "Ah, plague take the lot of 'em. Look there! Hi, you fellows! Fire over their heads, quickly!"

Too late! What happened now was swift and unexpected. From the sand-ridges beside the wadi spurted rolling tufts of smoke; even before the sound of the shots reached him, Fabre saw the two men guarding the horses pitch to the sand. The covey of women and children scattered like quail and vanished; so did the horses. Far beyond musket-shot, horsemen appeared rounding up the scattered beasts.

The four soldiers left in the village, seeing their comrades thus shot down and themselves set afoot, burst into torrential oaths and shouts of fury. The sergeant calmed them with cool, swift orders; he seized a musket and passed it to Fabre, then took charge. The guide and interpreter hid themselves in the houses.

"Six of us here, guns for all…. Steady, you bastards, save your breath! Two of you to the wall with me. The other three stay back, hold your fire, be ready to reload fast. They'll be on us in a minute—hold your fire, damn you, till I give the word!"

Everything passed with incredible rapidity. Fabre, fumbling to load his musket, scarcely had the ball rammed down when a dozen or more horsemen appeared up the wadi; others came to join them from one side, and swept down toward the village. Thanks to the cool old sergeant, the men had recovered from their panic and fury, and stood ready. The veteran spoke again.

"Careful, now; don't waste a ball. Aim for the horses, then reload. Pay 'em for our two comrades, there!"

They were coming at the gallop, with shrill yells of "Allah!" Two of the foremost riders wore the Mameluke panoply—steel helmets and shirts; the others were desert Arabs. They flourished long guns and opened a furious but totally ineffective fire as they came charging. Fabre, who had brought a brace of pistols from town, hurried to get them loaded. The sergeant and his two men, at the mud wall, were aiming carefully.

Over twenty of the horsemen, and more trailing from the sand- hills to join them. They came in a wild rush, sabers out, guns waving, voices screaming, evidently thinking to take the village at the first sweep. Suddenly the sergeant's long musket banged. One of the two Mameluke leaders plunged down. The other two muskets spoke, and two more horses fell. The sergeant, hastily reloading, waved a hand to Fabre.

"Come along, all of you! Don't waste a shot."

With his companions, Fabre ran to the wall. Several of the Arabs, afoot, were hurling themselves through the gaps; the sergeant and his two men met them with bayonets fixed. The three fresh muskets poured their fire into the huddle of figures. Fabre seized his two pistols, aimed and fired deliberately, and this broke the attack. Leaving half a dozen wounded or dead, and several horses pitching and screaming, the Arabs fled for cover. Among the dead was one of the mail-clad Mamelukes. Fabre left the shelter of the wall, darted to the glittering figure, and catching up helmet and sabre, brought them in as trophies. Two wild shots whistled overhead.

"Well, that did it," observed the sergeant. "Now things will get tough. They'll come in from all sides. Everybody scatter out along the wall, take plenty of powder and ball, and don't waste ammunition. If we're rushed, gather around the well."

Two hurt Arabs, dragging themselves away, were shot. From the terfa brush and sand gullies a dropping fire was opened on the village, without damage. Posts were taken, and the day that had opened to excitement of battle settled into monotony of sniping warfare, with only an occasional shot returned.

INSUFFERABLY the sun blazed down. Noon came, passed. Fabre

dragged the guide and interpreter from hiding, and put them to

work as cooks. Unexpectedly, in the full afternoon heat, figures

on foot burst from shelter on two sides of the village and came

in with a desperate charge. Several of them were dropped, three

or four gained a gap in the wall, and saber clanged on bayonet

until they broke and fled again. But two of the soldiers had been

wounded badly.

After this, nothing happened. The battle had settled into a siege. The attackers worked close, and their fire began to be accurate and deadly.

Fabre consulted with the sergeant, as the afternoon wore along. With the horses gone, their chance of escape was gone also; to leave the shelter of the village, with its copious well, would be madness. To judge by the figures visible beyond range, the number of the enemy was increasing; more than once, Fabre had glimpsed the glittering shape of the remaining Mameluke afar, evidently disposing his men. A messenger to bring help? Neither the guide nor the interpreter was willing to venture it; no other could regain the city.

The shadows were lengthening, and the sun was low, when everyone came to the alert at the sound of shots. They came closer. Presently Fabre discerned a horseman coming up the wadi at a gallop, while Arab guns banged at him from either side. He headed for the village at a desperate burst of speed, hanging low in the saddle, and his uniform was recognized as that of the Guides, commanded by Sulkowski.

Muskets blazed to cover his approach. His horse, streaming blood from a dozen wounds, went down thirty yards from the wall. Two men dashed out to bring him in, and he came staggering between them. Two balls had gone through his body; he was done for.

"Orders—to return!" he gasped out. "Citizen Duroc sent me—no use—all is lost! Revolt everywhere. Sulkowski is dead—Dupuy was cut to pieces—all Christians massacred—the sick and wounded killed—Arabs have the city—"

His head lolled over, in midsentence, and he died.

At this terrible information the little group looked one at another, knowing the worst. Revolt had caught the French by surprise. No help would come now; their fate was sealed. The sergeant broke in upon their frightful silence with an oath.

"Get to your places, everyone—to the walls! We're not dead yet. Mort de Dieu, look alive, you scoundrels! I'll arrange later for sentries to watch the night. Gather everything you can find and build fires! Quick about it, now—all the wood you can discover in this accursed village!"

They broke into action. Every scrap of wood in and about the houses was collected. With darkness, fires were lighted, sentries posted, and those off duty got some repose. No attack came; none the less, that was a frightful night. Toward dawn, one of the wounded men died.

Morning came; the sun mounted; and more natives arrived to swell the attacking ranks. A hundred or more were in full sight, sitting like vultures on the heights, while others kept up a steady fire on the village. Clouds, rarely seen here, drifted over the sky. It was mid-morning when the rumble of thunder sounded—a phenomenon almost unknown in Egypt. A peal ripped across the sky. Then a shout broke from the sergeant.

"Listen! The guns!"

Guns indeed—artillery on the distant citadel, hurling death into the Arab city, blending with and prolonging the thunder. The Corsican was at work; but what help here? None, except a furtive word that the sergeant brought to Fabre.

"Sorry, citizen. The powder's running low. Save it."

TOWARD noon, came the attack. There must have been two

hundred, pressing forward at a wild run under cover of a heavy

fire. One of the soldiers was killed. The muskets smashed into

them; a grenade, brought along by one of the men, exploded in the

massed ranks. Again they broke and ran, while bullets hailed in

from the sandy heights around.

The sergeant came to Fabre.

"Well, citizen, this looks like it. We haven't a dozen charges left."

"We've done our best," said Fabre simply.

Duroc had sent to save him—good old Duroc! He looked down at his hand. Who would get the emerald now? That Mameluke girl had spoken truly; it would be taken from him as he had taken it. The end was coming. Curiously enough, Fabre knew this, yet he could not realize it clearly; one never does.

His eye fell on one of the clay-vats nearby, and a laugh came to his lips. He took some of the clay and mixed it with water, making a firm mud. Of this he fashioned a miniature pyramid. From the ring he pried out the emerald, and thrust the green stone firmly into the heart of the little mud-pyramid, smoothing over the mud above it. When the thing was finished to his liking, he took his knife and with the point began to scratch letters in the soft mud.

"For Hector Duroc, Membre de l'Institut," he scratched, then his initials and the date. On another of the pyramid's sides he scratched the word "morituri," but there was no room for the entire quotation. "We who are about to die"—well, that was enough! Some one would find this, and Duroc would get it eventually, a legacy from the dead. Duroc would understand. He would look inside the pyramid for the Sphinx.

Viewing his work with satisfaction, Fabre laid it aside in the sun to dry and harden, amid a pile of the village wares. The afternoon was lengthening. Shouts and yells sounded; more Arabs had come riding up; bullets were pouring in upon the fated village; and powder-smoke drifted over the wadi. The sergeant appeared.

"Come along to the well, citizen. Only two more of us now—Lemaire just got his. Looks like a rush coming."

They ran from house to house, sheltering against the whistling balls, and reached the well. Two more men stood there; the muskets of the dead had been gathered and loaded with the last charges. The Arabs were assembling.

"Well, everybody, here's luck on the other side!" the sergeant sang out. A burst of yells drowned his voice, and the rush came—wild faces, guns and sabers waving, the name of Allah echoing to heaven.

None of the defenders uttered a word. They were too busy firing the muskets and fixing bayonets. In the forefront of the oncoming rush, Fabre discerned the mailed figure of the Mameluke, long curved saber in hand.

They were almost to the wall—they were over it, surging in at the gaps. The sergeant fired his last shot, clubbed the musket and swung into the sabers and wild faces. He was down. Fabre had his one pistol left. He saw the Mameluke coming for him and lifted the pistol, calmly. He would make sure of this fellow, anyhow!

Recognition stabbed into him; his finger slid from the trigger! That face! Those eyes! It was she, Amina herself! A smile touched his lips, and he lowered the pistol. It was his last act….

He was still smiling, faintly, when Duroc, Bonnard and their detachment of Guides found him next day. The village was deserted, save for the dead. The cursing Frenchmen collected the bodies of their own for burial. Bonnard and the geologist stood apart.

"He was no fighting man. Why did it have to come to him here?" burst out Duroc, with a volley of furious oaths. He was white and strained, almost beside himself.

"I went through his clothes," Bonnard said. "There was nothing. He left no word. Did you see the empty ring on his hand? The stone's gone—probably smashed."

"Be damned to it," said Duroc roughly. "I wasn't thinking about that. I'd give a dozen emeralds for him—to have him back. Damn it, the boy was my friend!"

"The best we can do is to see him buried decently," said Bonnard.

They did it, and rode away again, and no one noticed the little sun-baked pyramid of dried clay, shoved amid the stock of village pots.